Abstract

Background:

Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) represents a prodromal dementia stage marked by cognitive decline without functional impairment. Given limited drug efficacy and global aging, non-pharmacological interventions are urgently needed. Virtual reality (VR) enables immersive cognitive rehabilitation, yet evidence remains inconsistent due to divergent intervention approaches (training vs. gaming) and technical parameters like immersion level.

Objective:

This systematic review and meta-analysis synthesized evidence from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) to evaluate the efficacy of VR-based cognitive training and gaming interventions on cognitive function in older adults with MCI and to investigate the moderating role of immersion level.

Methods:

We systematically searched four electronic databases (PubMed, Web of Science, Embase, Scopus) from inception to July 20, 2025, for RCTs investigating VR interventions (cognitive training or games) in individuals aged ≥ 55 years diagnosed with MCI. Two independent reviewers performed study selection, data extraction (including intervention characteristics, implementation details, and behavior change techniques), and risk-of-bias assessment using the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool (RevMan 5.4.1). Standardized mean differences (Hedges’s g) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were pooled using random-effects models in Stata 18.0. Heterogeneity was quantified using I2. Publication bias was assessed via funnel plots and Egger’s test. Pre-specified meta-regression explored immersion level as a potential moderator. The certainty of evidence was assessed using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) system.

Results:

Of the 2,486 articles retrieved in total, 11 studies were included in the analysis. VR demonstrated a statistically significant improvement in the efficacy of cognitive rehabilitation among patients with MCI (Hedges’s g = 0.6, 95% CI: 0.29 to 0.90, p < 0.05). Specifically, VR-based games (Hedges’s g = 0.68, 95% CI: 0.12 to 1.24, p = 0.02) showed greater advantages in improving cognitive impairments compared to VR-based cognitive training (Hedges’s g = 0.52, 95% CI: 0.15 to 0.89, p = 0.05). The immersive level of VR interventions emerged as a significant moderator of heterogeneity across the included studies. Based on the GRADE criteria, the quality of evidence for the efficacy of VR-based interventions on cognitive function in individuals with MCI is moderate. A stratified analysis by intervention type showed that VR cognitive training is supported by moderate-certainty evidence, while evidence for VR games is of low certainty.

Conclusion:

VR-based interventions, including cognitive training and games, effectively improve cognitive function in MCI patients, with VR games showing a trend toward greater efficacy. Immersion level critically influences therapeutic outcomes, requiring optimized sensory integration while accommodating individual tolerance. These findings support supervised clinical VR training alongside engaging home-based protocols to enhance adherence. Future development of standardized immersion adjustment and personalized guidelines will advance utility across care settings.

1 Introduction

Mild cognitive impairment (MCI), defined as a level of cognitive ability that is lower than would be expected for their age and educational level, occurring between normal aging and dementia (1). Individuals diagnosed with MCI are at a significantly higher risk of progressing to dementia, with a mean annual conversion rate of approximately 10%, compared to the annual incidence of 1–2% in the general population (2, 3). Treatments can be implemented to slow down the advancement of dementia during the preclinical phase (4), making the identification of effective therapeutic strategies to delay or prevent the progression to dementia of utmost importance.

The increasing prevalence of MCI, driven by the aging global population, there are few medications or dietary therapy that can improve cognitive function or slow MCI progression, non-pharmacological treatments have received attention (3, 5). One of the non-pharmacological treatments is the use of virtual reality (VR) technology, which is currently employed in the control and treatment of various diseases (6). It helps the user create a real sense of presence and immersion in the virtual world through multiple sensory stimuli (visual, auditory, tactile, and olfactory) while also functioning by distracting them within that virtual and simulated environment (7, 8). Virtual reality technology demonstrates two principal manifestations in cognitive rehabilitation: VR-based cognitive training and VR-based games. This fundamental distinction reflects divergent methodological approaches to cognitive enhancement, each characterized by unique mechanisms of engagement and therapeutic delivery. In cognitive training, VR serves as a targeted intervention for specific cognitive domains—such as memory and attention—through repetitive, goal-oriented tasks (9). These projects may incorporate elements of “serious games” to increase engagement, but their main focus is on therapeutic training. For instance, integrating VR technology into routine training creates immersive experiences for individuals with mild cognitive impairment (9, 10). In contrast, VR games emphasize immersive narratives, exploration, and compelling gameplay (11, 12). Cognitive challenges are naturally embedded within story-driven objectives—such as solving puzzles or completing simulated missions (13). This approach prioritizes intrinsic motivation, presence, and enjoyment, facilitating cognitive exercise within ecologically rich environments (14). While both paradigms share the ultimate goal of cognitive enhancement, their differing design philosophies and engagement paradigms may yield differential outcomes in therapeutic efficacy, adherence patterns, and cognitive benefit profiles (15, 16), thereby directly informing the precision design of future VR interventions.

Several trials have investigated the impact of VR on older adults with MCI, but the findings have been inconclusive. For example, studies by Baldimtsi et al. (17) and Park et al. (10) revealed a significant effect of VR on general cognitive abilities. However, the findings from Park et al. (18) showed that a 12-week, culture-based VR training program did not improve general cognitive abilities and did not show significant differences in scores on the Mini-Mental Status Examination (MMSE). Also, it is challenging to make definitive conclusions about the effectiveness of interventions because of variations VR intervention content (cognitive training or games). In a study conducted by Yang et al. (16), daily life-based VR training games (making juice, shooting crows, finding the number of fireworks, and memorizing objects in the house) were found to positively affect general cognitive performance. However, in a study by Kang et al. (15), while the VR group participants received multidomain and neuropsychologist-assisted cognitive training, no significant differences in general cognitive performance were observed when compared to other groups or baseline measurements. To the best of our knowledge, although the use of VR technology to improve cognitive function is increasing (19), the impact of VR-based cognitive training and games on the cognitive rehabilitation of patients with MCI remains controversial (10, 14).

In conclusion, while existing studies have demonstrated the potential value of VR-based cognitive training, current evidence regarding its efficacy in MCI remains limited by methodological constraints. Notably, there is a scarcity of systematic reviews or meta-analyses specifically examining the cognitive rehabilitation effects of VR-based training and gaming interventions in the MCI population. To address this gap, this study conducted a comprehensive meta-analysis to quantitatively synthesize existing evidence and evaluate the therapeutic potential of VR interventions for cognitive rehabilitation in individuals with MCI.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Search strategy

Studies were identified by searching web-based databases with support and consultation provided by institutional librarians. Four databases were searched (PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, Scopus) by combining keywords. To include studies reflecting the latest advancements in VR technology and methodologies, the focus was on literature published from January 2013 to July 2025. The year 2013 was chosen to ensure consistency in the technological sophistication and usability standards of VR interventions, as VR technology and its applications in cognitive rehabilitation have rapidly evolved over the past decade (20). Keywords and search strategies are included: (“Virtual Reality” OR “VR” OR “virtual environment” OR “Virtual Reality Training” OR “VR cognitive training” OR “virtual game” OR “Game” OR “Gaming” OR “video games”) AND (“Mild Cognitive Impairment” OR “MCI” OR “Cognitive Dysfunction” OR “Cognitive Disorder” OR “Cognitive Impairment” OR “cognitive decline”) AND (“treatment” OR “intervention” OR “rehabilitation” OR “therapy” OR “training”).

2.2 Selection criteria

2.2.1 Inclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria were defined with the PICOS approach: (i) Studies concerning older adults (aged ≥ 55 years) with a confirmed diagnosis of MCI by neurologic examination or neuropsychological assessment were included. The diagnosis was typically operationalized through standardized cognitive cut-offs, most commonly a Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) score of 24–27 or a Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) score of 18–26, to define the presence of objective cognitive impairment while excluding frank dementia (21, 22); (ii) Intervention: VR-based cognitive training and gaming; (iii) Controls: Studies with any type of control group were included (inactive controls include educational programs or no intervention; active controls include traditional rehabilitation or any other type of physical activity, physical-cognitive co-training, or video games without VR components); (iv) Outcome: Overall cognitive function; (v) Study design: randomized controlled trials (RCTs); (vi) Additional: Published in English; full-text available.

2.2.2 Exclusion criteria

The exclusion criteria were as follows:

-

I No specific identification of cognitive impairment: Studies where VR was not used in the intervention group, or VR was used in the control group, were excluded.

-

II Cognitive impairment caused by other conditions: Studies where cognitive impairment was attributed to other medical conditions, such as stroke, cerebral infarction, traumatic brain injury, or other neurological disorders, were excluded. This ensures that the cognitive impairment under study is specifically related to MCI and not secondary to other health issues.

-

III Materials such as books, book chapters, letters to the editor, and conference abstracts were excluded from the analysis.

2.3 Study selection and data extraction

The article search and selection process were reviewed through the title and abstract of searched articles after the primary database search and, in the full review, two authors finally selected the articles by considering the eligibility criteria. This process was performed using a preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis (PRISMA) flow chart (23). Data were extracted by 2 researchers (PY and DP) and cross-checked by a third researcher (JC). The data extraction form encompassed various fields, including the author, published year, country, study design, sample size (male/female), mean age, intervention in treatment group, intervention in control group, duration of the session and the follow-up period and outcome characteristics was extracted.

2.4 Classification of immersion level

Based on specific technical specifications—including stereoscopy, 3/6-DOF tracking, natural interaction paradigms, and advanced features such as haptic feedback—we established operational criteria to classify immersion into three distinct levels: Low, Moderate, and High (24, 25). Details in Table 1.

Table 1

| Degree | Low immersion | Medium immersion | High immersion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core systems and display devices | Non-immersive systems rely on standard 2D displays—including desktop monitors, television screens, or tablets—that lack stereoscopic vision and multi-sensory depth cues. These configurations offer limited perceptual engagement and a restricted field of view, preventing a truly immersive user experience. | Semi-immersive systems utilize head-mounted displays (HMDs) to deliver stereoscopic 3D visuals while isolating users from their physical environment. | Fully immersive systems employ advanced head-mounted displays that deliver high-resolution, wide-field-of-view stereoscopic 3D vision, creating profound visual encapsulation. |

| Tracking degrees of freedom | These systems provide no spatial tracking or only offer basic controller-based input tracking. | These systems provide 3-DOF tracking, capturing only rotational head movements (pitch, yaw, and roll). | These systems support full 6-DOF tracking, enabling simultaneous monitoring of positional movements (forward/backward, left/right, up/down) and rotational orientation for both the head and controllers. |

| Interaction modality and naturalness | These systems employ abstract, symbolic interaction through conventional input devices such as mice, keyboards, touchscreens, or standard game controllers. | These systems incorporate basic motion controllers that translate hand gestures—such as pointing and clicking—into virtual interactions, though with constrained precision and limited naturalism. | These systems implement natural interaction paradigms—such as 6-DOF motion controllers, hand tracking, or full-body tracking—enabling intuitive object manipulation that closely replicates real-world interactions with high fidelity. |

| Sensory involvement and feedback | Sensory engagement is minimal in these systems, primarily limited to visual and basic auditory feedback, resulting in a weak sense of presence. | These systems achieve moderate sensory engagement through stereoscopic vision and head motion tracking, which significantly enhance presence. Basic haptic feedback—such as controller vibration—may also be incorporated. | These systems deliver peak sensory engagement by integrating multi-sensory stimulation—including spatialized audio and advanced haptic feedback—to create deeply compelling and highly realistic experiences. |

Operational criteria for VR immersion levels.

2.5 Risk of bias and GRADE assessment

The risk of bias assessment was conducted using the risk of bias tool from Rev. Man 5.4.1 (26). This tool evaluates seven aspects: random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting, and other biases. Each aspect was rated by the researchers as high risk (−), low risk (+), or uncertain risk (?). In cases of disagreement on the ratings, a consultation process was implemented to reach a consensus. The certainty of evidence for each outcome was rated using the GRADE approach, which evaluates five key domains: risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, and publication bias (27, 28). The evaluation process also incorporated an assessment of factors that could potentially upgrade the certainty of the evidence, such as a large magnitude of the effect estimate or evidence of a dose–response gradient. Following this comprehensive appraisal, the overall certainty of evidence for each outcome was categorized as high, moderate, low, or very low.

2.6 Statistical analysis

The included studies were synthesized and analyzed using Stata version 18.0 software. Statistical heterogeneity, effect size, meta-regression, and publication bias were analyzed. Hedge’s g was used to calculate and interpret the effect size. For calculation and analysis of results, mean, standard deviation, and number of subjects were used as values. The heterogeneity was quantitatively determined by I2, where I2 values of < 25, 26–74, and > 75% represented small, moderate, and large levels of heterogeneity, respectively. Fixed-effects models were applied when heterogeneity was graded as small, whereas random-effects models were utilized for moderate or large heterogeneity (29). Publication bias refers to an error in which research results are published or not published depending on the characteristics or direction of research results. If a distorted sample of studies is included in a meta-analysis, the overall size of the analysis result can be said to be a distorted result (30). To confirm this tendency, it was reviewed and presented through a funnel plot and Egger’s regression test (31). In addition, meta regression was used to assess the sources of heterogeneity in the included studies.

3 Results

3.1 Study selection

A total of 2,486 papers were identified using the four databases, of which 474 were duplicates. Each of these studies underwent a rigorous and meticulous review, during which inclusion and exclusion criteria were carefully applied. The assessment process involved a thorough examination of the methodologies, results, and relevance to the research focus. After this meticulous screening, 11 articles that met the inclusion criteria were finally selected. The detailed process of this screening is as follows Figure 1.

Figure 1

PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) flow diagram. MCI, mild cognitive impairment; RCT, randomized controlled trial; VR, virtual reality.

3.2 Characteristics of included articles

A total of 11 studies were included, among which 8 were conducted in South Korea, and the remaining 3 were carried out in China, Turkey, and Ecuador. All included studies focused on elderly individuals with mild cognitive impairment (MCI). Regarding interventions for cognitive rehabilitation in MCI patients, 6 studies adopted VR-based cognitive training, such as spatial cognitive training, simulated shopping activities, and virtual kayaking paddling exercises; the other 5 studies utilized VR-based games, including Seek a Song of Our Own, Fireworks Party, and Boxing Trainer. In one of the articles, no intervention was implemented in the control group, while other studies applied interventions such as conventional training or a combination of cognitive training and physical activities. The characteristics of the included articles were presented in Table 2. This study further establishes a systematic classification of immersion levels across all included studies, with clearly defined criteria based on specific hardware capabilities and interactive features. The detailed classification framework is presented in Table 3.

Table 2

| Author, Year | Country | Study Design | Sample size (M/F) | Age (M ± SD) | Intervention in treatment group | Intervention in control group | Duration of the session and the follow-up period | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Park et al. (36) | Korea | RCT (single-blind) | EG: 28(12/16) CG: 28(11/17) |

EG: 71.93 ± 3.11 CG: 72.04 ± 2.42 |

Virtual reality space cognitive training | No interference is accepted | 56 sessions, 45 min/session, 3 days/week 8 weeks |

WAIS-BDT |

| Kang et al. (15) | Korea | RCT | EG: 23(6/17) CG: 18(6/12) |

EG: 75.48 ± 4.67 CG: 73.28 ± 6.96 |

Neuropsychologist-guide-d immersive VR cognitive training. | Usual therapy: pharmacotherapy |

Approximately 20–30 min for each session, twice a week, for 1 month |

MMSE |

| Buele et al. (9) | Ecuador | RCT (single-blind) |

EG: 17(7/10) CG: 17(4/13) |

EG:75.14 ± 5.76 CG:77.35 ± 6.75 |

VR kitchen search cognitive training. | Non-VR cognitive training task. | 6-week intervention (a total of twelve 40-min sessions) |

MoCA |

| Park J. S. et al. (10) | Korea | RCT | EG:18(10/8) CG: 17(7/10) |

EG: 75.8 ± 8.5 CG: 77.2 ± 7.2 |

MOTOCOG®system | Tabletop activities | 30 min per day, 5 days/week, for 6 weeks |

MoCA |

| Choi et al. (33) | Korea | RCT | EG: 30(5/25) CG: 30(4/26) |

EG: 77.27 ± 4.37 CG: 75.37 ± 3.97 |

Virtual kayak paddling exercise |

Home exercises | 60 min per day, 22 days/week, for 6 weeks |

MoCA |

| Liao et al. (34) | China | RCT (single-blind) |

EG: 18(7/11) CG: 16(4/12) |

EG: 75.5 ± 5.2 CG: 73.1 ± 6.8 |

VR daily activities; Cognitive tasks |

Combined Physical and Cognitive Training | 60 min per day, 3 days/week, for 12 weeks |

MoCA |

| Torpil et al. (37) | Turkey | RCT (single-blind) |

EG: 30(11/19) CG: 31(14/17) |

EG: 70.12 ± 2.57 CG: 70.30 ± 2.73 |

Four games (Boxing Trainer, Jet Run, Superkick, Air Challenge) |

LOTCA-G cognitive domain intervention |

45 min per day, 2 days/week, for 12 weeks |

LOTCA-G |

| Thapa et al. (13) | Korea | RCT | EG: 34(6/28) CG: 34(10/24) |

EG: 72.6 ± 5.4 CG: 72.7 ± 5.6 |

Four VR training games | An educational program focusing on overall healthcare |

100 min per day, 3 days/week, for 8 weeks |

MMSE |

| Lim et al. (35) | Korea | RCT (single-blind) |

EG: 12(3/9) CG: 12(4/8) |

EG: 75.42 ± 5.74 CG: 73.33 ± 17.52 |

Brain Talk™ home-based Serious game |

Performing daily tasks | 30 min per day, 3 days/week, for 4 weeks |

MoCA |

| Yang et al. (16) | Korea | RCT | EG: 33(13/20) CG: 33(6/27) |

EG: 72.5 ± 5.0 CG: 72.6 ± 5.6 |

Targeted cognitive games. | Health education seminars on geriatric nutrition and exercise. | 100 min per day, 3 days/week, for 8 weeks |

MMSE |

| Park J. H. et al. (18) | Korea | RCT | EG: 10(3/7) CG: 11(4/7) |

EG: 71.80 ± 6.61 CG: 69.45 ± 7.45 |

Six VR Game Training Programs |

Maintain normal daily activities | 30 min per day, 2 days/week, for 3 months |

MMSE |

Characteristics of the included articles.

Table 3

| Study (First Author, Year) | Assigned immersion level | Rationale for classification |

|---|---|---|

| Buele (9) | High | Utilized a fully immersive HMD with 6-DOF tracking, wireless controllers enabling natural interaction, and a fully enclosed interactive virtual environment. |

| Choi (33) | Low | The system employed a large projection screen instead of a head-mounted display, delivering a “virtual reality” experience more akin to immersive video viewing than interactive simulation. |

| Kang (15) | High | The study explicitly reported using an Oculus Rift CV1 head-mounted display with Oculus Touch controllers. As a high-end PC-VR system, the Oculus Rift provides 6-DOF positional tracking and enables natural interaction, establishing a fully immersive 3D virtual environment. |

| Liao (34) | High | The study utilized a fully immersive HTC VIVE head-mounted display with room-scale 6-DOF tracking, wireless controllers supporting natural interaction, and a complex interactive virtual environment based on activities of daily living. |

| Lim (35) | Low | The study was described as a “home-based serious game on a tablet computer,” with the intervention entirely delivered on a 2D flat screen. Participants interacted via touchscreen, without using a head-mounted display or possessing spatial tracking capabilities. |

| Park (36) | Low | The study utilized a desktop computer running a Unity program with joystick-controlled navigation. No head-mounted display was employed, and multi-sensory feedback was absent, resulting in a screen-based two-dimensional interactive experience. |

| Park J. H. (18) | High | The study employed an HTC Vive head-mounted display featuring a 2,160 × 1,200 resolution, 90 Hz refresh rate, and 110-degree field of view. The system supported 6-degree-of-freedom tracking and bimanual controller interaction, delivering fully immersive visual and auditory experiences. |

| Park J. S. (10) | Middle | The study utilized a PC-driven commercial HTC Vive head-mounted display, delivering high-resolution stereoscopic vision, approximately 110-degree field of view, 90 Hz refresh rate, and room-scale 6-degree-of-freedom tracking. Interaction was implemented through standard VR controllers. Although the tracking precision was high, the interaction modality remained conventional, with no mention of natural hand interaction or haptic feedback beyond standard vibration. |

| Thapa (13) | High | The study employed a commercial all-in-one head-mounted display (Oculus Quest), providing first-person perspective, stereoscopic vision, and 6-degree-of-freedom head tracking. Interactions were implemented through standard wireless VR controllers. |

| Torpil (37) | Low | The study utilized Microsoft Kinect for PC, explicitly described as operating “without immersion,” with visual content displayed on a 65-inch flat-panel screen. Participants stood before the television and controlled interactions through body movements. The setup lacked a head-mounted display and multi-sensory immersion capabilities. |

| Yang (16) | High | The study employed an Oculus Quest head-mounted display paired with two wireless hand controllers, delivering a fully immersive VR experience. The headset provided complete visual isolation and environmental occlusion. |

Classification of immersion level in included studies.

3.3 Assessment of methodological quality

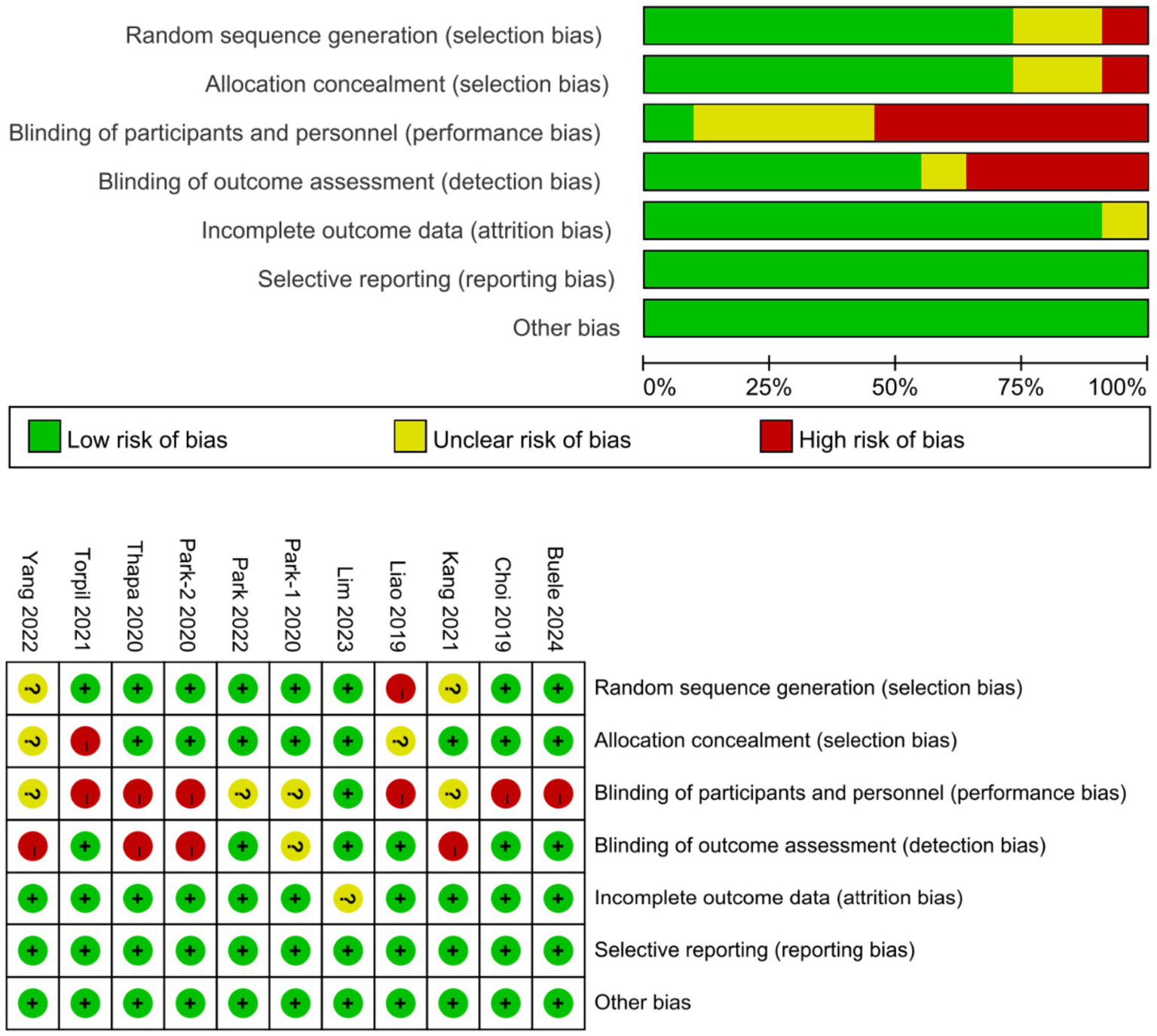

The results of risk of bias assessment were as follows: random sequence generation (low: 8, uncertain: 2, high: 1), allocation concealment (low: 8, uncertain: 2, high: 1), blinding of participants and personnel (low: 1, uncertain: 4, high: 6), blinding of outcome assessment (low: 6, uncertain: 1, high: 4), incomplete outcome data (low: 10, uncertain: 1), selective reporting (low: 11), and other biases (low: 11). For other biases, items such as lack of sample size calculations, differences in baseline characteristics, and lack of study protocol registration were assessed as uncertain or high (32) (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Risk of bias summary [Park et al. (36); Kang et al. (15); Buele et al. (9); Park et al. (10); Choi et al. (33); Liao et al. (34); Torpil et al. (37); Thapa et al. (13); Lim et al. (35); Yang et al. (16); Park et al. (18)].

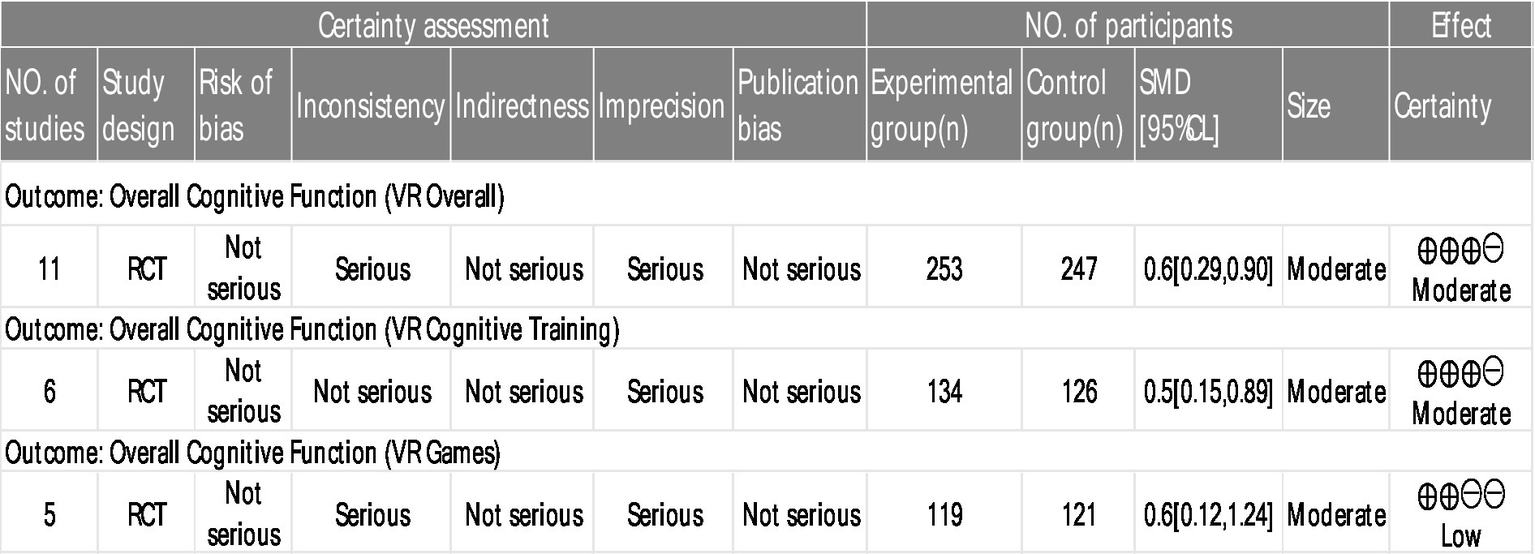

According to the GRADE assessment, the certainty of evidence regarding the effect of VR interventions on overall cognitive function in patients with MCI was rated as moderate. This judgment was based on a balance of downgrading and upgrading factors. The evidence was downgraded due to substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 64.69%) and imprecision resulting from a limited sample size and wide confidence intervals. However, it was upgraded based on a significant dose–response relationship identified in the meta-regression analysis, wherein a higher level of VR immersion was positively correlated with greater cognitive improvement (β = 0.834, p < 0.05). In subgroup analyses, the certainty of evidence was moderate for VR-based cognitive training but low for VR-based gaming. The latter was further downgraded to low certainty within its subgroup, primarily owing to considerable heterogeneity and more severe imprecision (as indicated by extremely wide confidence intervals; Figure 3).

Figure 3

GRADE level of evidence rating scale for indicators of consequences.

3.4 Meta-analysis results

3.4.1 The effect size on cognitive rehabilitation

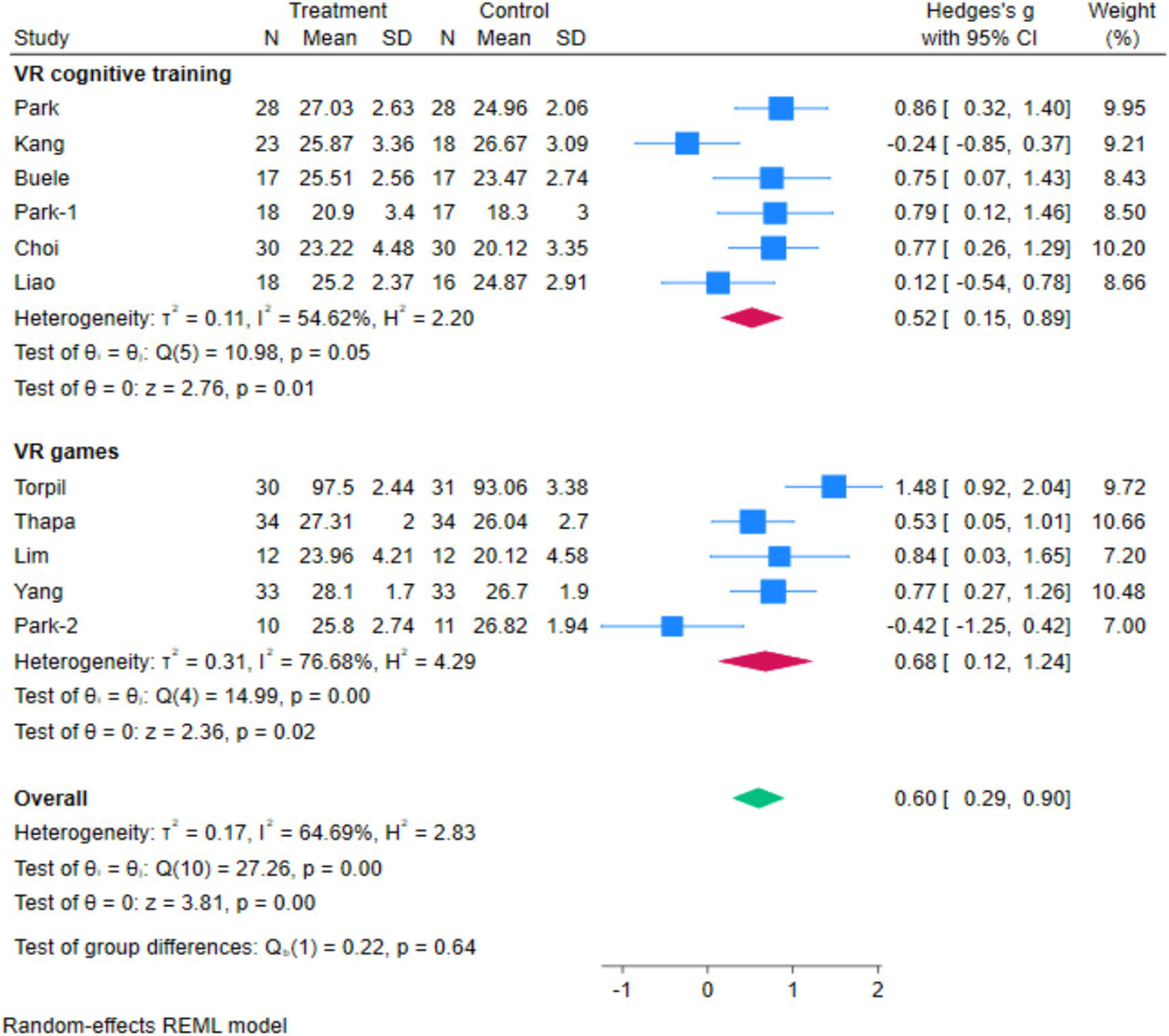

A total of 11 studies involving 500 MCI patients reported on the effects of VR technology based interventions on cognitive rehabilitation at post intervention time points (range 4 ~ 12 weeks) compared with conventional control conditions (Figure 4) (9, 10, 13, 15, 16, 18, 33–37).

Figure 4

The forest map.

The I2 between the included studies was >50%, thus a random-effects model was employed to assess the effect size. The research indicates that VR-based therapy has a significant positive impact on cognitive rehabilitation in individuals with MCI (Hedges’s g = 0.6, 95% CI 0.29 to 0.90, p < 0.05). The highest and lowest effect sizes were related to the study of Torpil (37) and Liao (34), respectively (Figure 4).

Based on Cohen’s d standardized effect size, this effect size is medium (38). Also, VR games (Hedges’s g = 0.68, 95% CI: 0.12 to 1.24, p = 0.02) have been demonstrated to improve cognitive disorders more effectively than cognitive training (Hedges’s g = 0.52, 95% CI: 0.15 to 0.89, p = 0.05).

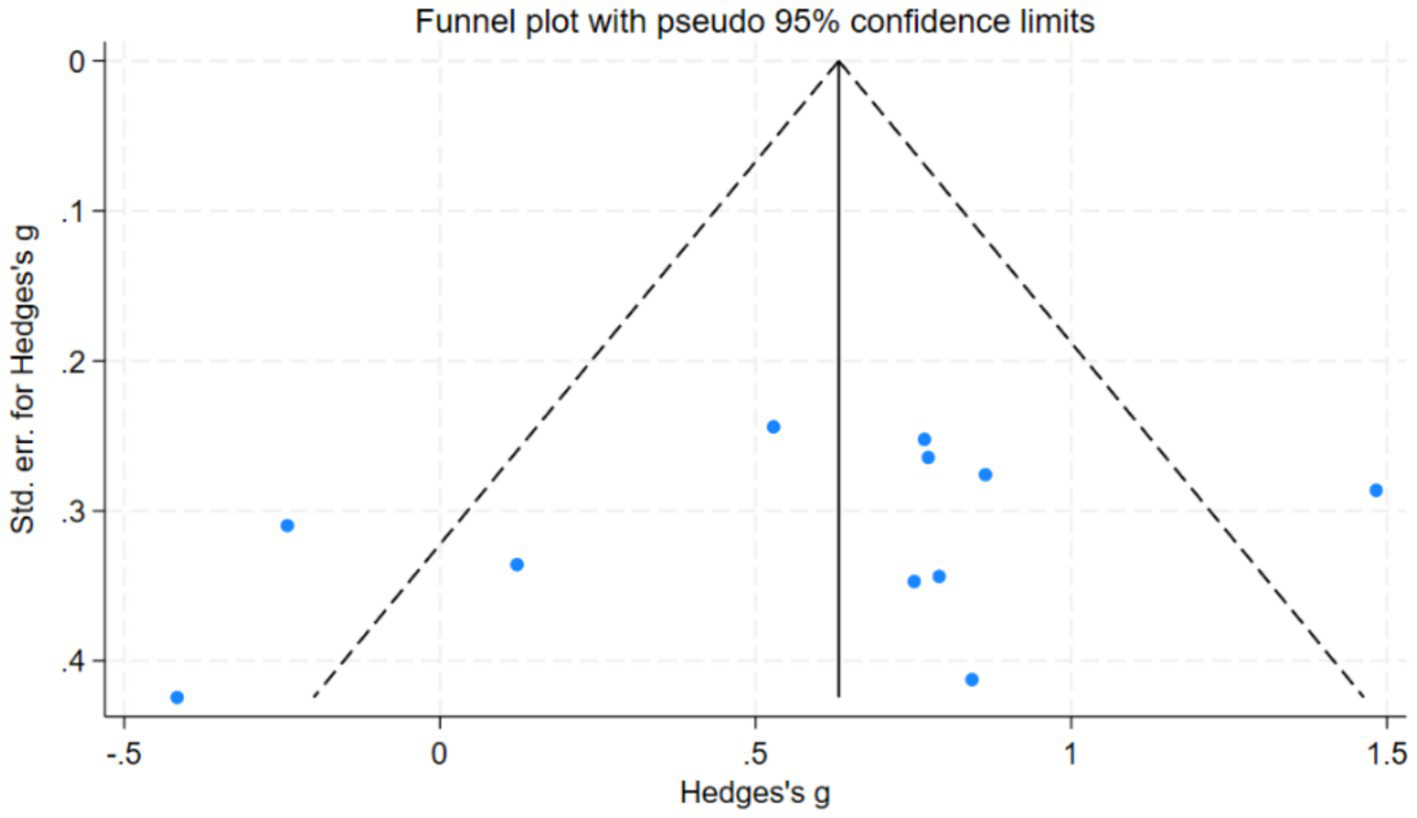

3.4.2 Publication bias

The funnel plot (Figure 5) illustrates the absence of publication bias in the studies. Moreover, the result of the Egger’s regression test was (t = −1.07, p = 0.31). This shows there is no publication bias.

Figure 5

Publication bias of the included articles.

3.4.3 Meta-regression analysis

Meta-regression analysis identified the level of VR immersion as a statistically significant and positive moderator of cognitive improvement (coefficient β = 0.834, 95% CI: 0.211 to 1.457, p < 0.05), indicating that each unit increase in immersion level (e.g., from “low” to “medium” or “medium” to “high”) was associated with an average 0.834 increase in effect size (Table 4). In contrast, the analysis revealed that while intervention duration (p = 0.089) and blinding implementation (p = 0.072) did not reach conventional statistical significance thresholds, their coefficient estimates and confidence intervals suggested meaningful effect sizes approaching significance. These findings indicate potential moderating trends that merit examination in future studies with larger sample sizes. Other covariates, including VR intervention type and outcome measurement characteristics, demonstrated no appreciable relationship with effect size (p > 0.15), supporting their exclusion as substantive moderators in the current data set (Table 4).

Table 4

| Covariates | Coefficient | Standard error | 95% CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Duration of intervention | −0.446 | 0.212 | (−0.992, 0.099) | 0.089 |

| Blind implementation | 0.891 | 0.392 | (−0.118, 1.900) | 0.072 |

| Immersive level | 0.834 | 0.242 | (0.211, 1.457) | 0.018 |

| Type of VR intervention | 0.361 | 0.216 | (−0.193, 0.915) | 0.154 |

| Result measure characteristics | 0.075 | 0.127 | (−0.251, 0.401) | 0.581 |

Effect sizes for separate meta-analyses on moderator variables.

4 Discussion

The present systematic review and meta-analysis specifically focuses on the efficacy of VR-based cognitive training and games in patients with MCI, providing targeted insights into this critical transitional stage between normal aging and dementia. The findings indicate that both VR-based cognitive training and games exert significant positive effects on cognitive rehabilitation in MCI patients, with a medium overall effect size (Hedges’s g = 0.60, p < 0.05). Subgroup analysis further reveals that VR games (Hedges’s g = 0.68) yield a slightly larger effect size than VR cognitive training (Hedges’s g = 0.52), though the difference is not statistically significant (p = 0.64). Additionally, meta-regression identifies VR immersion level as a key moderator of intervention efficacy, highlighting its potential role in optimizing therapeutic outcomes.

The therapeutic benefits of VR-based cognitive rehabilitation in MCI can be attributed to the condition’s distinctive neuropathological profile (39). While advanced dementia involves widespread neuronal degeneration, MCI patients maintain preserved neuroplasticity and functional capacity, rendering them particularly responsive to targeted cognitive stimulation (40). VR technology generates ecologically valid environments through multisensory integration and real-time interaction, effectively engaging neural networks underlying memory, attention, and executive functions (41, 42). Our findings, consistent with accumulating evidence (43–46) confirm that VR-based interventions significantly enhance cognitive performance in MCI patients. Notably no interference is accepted (47) and demonstrated VR efficacy in improving cognitive function in brain tumor patients, while Kim et al. (48) reported enhanced outcomes when combining VR with computer-based rehabilitation in stroke patients. These collective findings underscore VR transdiagnostic potential in cognitive rehabilitation, with MCI patients deriving particular advantage due to their retained neuroplasticity. Our findings indicate that VR-based games outperform structured cognitive training in rehabilitation efficacy, primarily attributable to their dual “entertainment-therapy” nature. By incorporating narrative tasks, reward mechanisms, and adaptive difficulty, these games effectively sustain engagement and overcome adherence limitations common in conventional training (10, 37). Empirical evidence confirms this advantage: Muñoz et al. (49) demonstrated that gamified VR tasks integrating motor-cognitive components significantly enhance participation, while Yanguas et al. (50) reported substantial cognitive improvements through VR gaming applications. Conversely, VR cognitive training employs structured protocols targeting specific domains, potentially yielding focused effects but lacking comparable motivational engagement. Although statistical significance was not achieved—possibly due to sample size constraints—the consistent effect pattern suggests clinical relevance for intervention selection.

Notably, the moderate heterogeneity observed in the study (I2 = 64.69%) underscores the necessity of developing standardized intervention protocols. The findings of Moulaei et al. (11) further emphasize the importance of considering specific design elements—such as the immersive characteristics of virtual reality environments—for achieving positive outcomes. In exploring potential sources of this heterogeneity, a notable finding emerging from the meta-regression is that the level of VR immersion—ranging from low-cost head-mounted displays to fully immersive systems—significantly moderates intervention efficacy (β = 0.834, p < 0.05). Interpretation of hardware-based immersion in meta-regression requires distinguishing technical immersion (objective system attributes) from subjective presence (the psychological sense of “being there”). While technical immersion establishes the foundation for presence through multisensory integration, presence intensity remains equally dependent on content design and individual factors (51). This conceptual distinction clarifies that the benefits of high-immersion systems operate primarily through presence-mediated pathways. Soh et al.’s research (52) further corroborated the interference-shielding effect of immersion in remote virtual rehabilitation. As demonstrated by Torpil et al.’s (37), heightened hippocampal and prefrontal activation under high-immersion VR conditions suggests presence may enhance cognitive outcomes by reducing environmental interference and deepening emotional engagement. Our meta-regression, however, could only approximate these mechanisms indirectly through hardware specifications. Future investigations should directly quantify presence using standardized measures while examining its mediating role between technical parameters and cognitive outcomes. Concurrently, optimizing immersion through haptic feedback and 360° rendering must balance technological advancement with individual tolerance in elderly MCI populations. This integrated approach will advance our understanding of VR therapeutic mechanisms while ensuring clinical applicability.

GRADE evaluation confirms moderate-quality evidence supporting VR interventions for cognitive improvement in MCI, establishing them as valid non-pharmacological alternatives. However, VR-based gaming specifically demonstrates low evidence certainty, warranting exploratory application. Clinical implementation should align with care settings: structured task-based protocols in hospitals, engaging games in community centers, and portable device training for home use. All applications require personalization of duration, frequency, and difficulty based on individual patient profiles. As demonstrated by Samarasinghe et al. (53) in their development of VR games for Alzheimer’s patients, tailoring interventions to individual cognitive profiles is essential. Future development should focus on standardizing immersion metrics, creating age-appropriate interfaces, and establishing remote support systems for home-based VR training. These steps are essential for ensuring intervention consistency and accessibility. To strengthen the evidence base, future research should adhere to GRADE recommendations through large-scale RCTs with enhanced blinding procedures and comprehensive outcome reporting. Such methodological rigor will address current limitations in precision and heterogeneity, ultimately supporting the standardized integration of VR into cognitive rehabilitation protocols.

5 Limitations

This study has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the findings. First, according to the GRADE assessment, the limited number of available trials and their aggregate sample size led to imprecise estimates, as reflected in wide confidence intervals. This imprecision was a key reason for the GRADE assessment of moderate (for overall VR efficacy) to low (for VR games) certainty of evidence. Second, the included studies predominantly featured short-term follow-up periods, which restricts our ability to draw firm conclusions regarding the long-term sustainability of the cognitive benefits derived from VR interventions. Third, the geographical distribution of the evidence is skewed, with 8 of the 11 included studies conducted in South Korea, potentially limiting the cross-cultural generalizability of the results. Fourth, the definition and measurement of “VR immersion level” were inconsistent across studies, challenging a standardized comparison of its moderating effect. Finally, the absence of double-blinding in all trials introduces a potential for performance and detection bias.

6 Conclusion

This systematic review of 11 randomized controlled trials establishes that VR-based cognitive training produces significant cognitive improvements in mild cognitive impairment, with technical immersion level serving as a crucial moderating factor. Achieving optimal outcomes requires balancing technological sophistication with individual cognitive adaptability to promote sustained engagement. To advance this field, future multi-center trials featuring extended follow-up periods and culturally diverse cohorts are essential for validating long-term efficacy and developing personalized intervention protocols.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

PY: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Data curation, Methodology, Conceptualization. DP: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Data curation. JC: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Investigation, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. QY: Conceptualization, Data curation, Project administration, Validation, Writing – review & editing. BL: Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Methodology. CL: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Supervision.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This study was supported by the 2022 National Social Science Fund of China (Education) Project entitled “Exploration and Contemporary Inheritance of Excellent Traditional Chinese Culture in Physical Education Textbooks During the Century-Long History of the Communist Party of China” (Project No.: BLA220232).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Correction note

A correction has been made to this article. Details can be found at: 10.3389/fneur.2025.1749179.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1.

Petersen RC . Mild cognitive impairment. Continuum (Minneapolis, Minn). (2016) 22:404–18. doi: 10.1212/Con.0000000000000313

2.

Meng Q Yin H Wang S Shang B Meng X Yan M et al . The effect of combined cognitive intervention and physical exercise on cognitive function in older adults with mild cognitive impairment: a Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Aging Clin Exp Res. (2022) 34:261–76. doi: 10.1007/S40520-021-01877-0

3.

Petersen RC Lopez O Armstrong MJ Getchius TSD Ganguli M Gloss D et al . Practice guideline update summary: mild cognitive impairment [RETIRED]: report of the guideline development, dissemination, and implementation subcommittee of the American Academy of neurology. Neurology. (2018) 90:126–35. doi: 10.1212/Wnl.0000000000004826

4.

Anderson ND . State of the science on mild cognitive impairment (MCI). CNS Spectr. (2019) 24:78–87. doi: 10.1017/S1092852918001347

5.

Pinto C Subramanyam AA . Mild cognitive impairment: the dilemma. Indian J Psychiatry. (2009) 51:S44–51.

6.

Grassini S . Virtual reality assisted non-pharmacological treatments in chronic pain management: a systematic review and quantitative Meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2022) 19:74071. doi: 10.3390/Ijerph19074071

7.

Laghari A Jumani A Kumar K Chhajro M . Systematic analysis of virtual reality & augmented reality. Int J Inf Eng Electron Bus. (2021) 13:36–43. doi: 10.5815/Ijieeb.2021.01.04

8.

Li L Yu F Shi D Shi J Tian Z Yang J et al . Application of virtual reality technology in clinical medicine. Am J Transl Res. (2017) 9:3867–80.

9.

Buele J Avilés-Castillo F Del-Valle-Soto C Varela-Aldás J Palacios-Navarro G . Effects of a dual intervention (motor and virtual reality-based cognitive) on cognition in patients with mild cognitive impairment: a single-blind, randomized controlled trial. J Neuroeng Rehabil. (2024) 21:130. doi: 10.1186/S12984-024-01422-W

10.

Park JS Jung YJ Lee G . Virtual reality-based cognitive-motor rehabilitation in older adults with mild cognitive impairment: a randomized controlled study on motivation and cognitive function. Healthcare (Basel). (2020) 8:335. doi: 10.3390/Healthcare8030335

11.

Moulaei K Bahaadinbeigy K Haghdoostd A Nezhad MS Gheysari M Sheikhtaheri A . An analysis of clinical outcomes and essential parameters for designing effective games for upper limb rehabilitation: a scoping review. Health Sci Rep. (2023) 6:E1255. doi: 10.1002/Hsr2.1255

12.

Tao G Garrett B Taverner T Cordingley E Sun C . Immersive virtual reality health games: a narrative review of game design. J Neuroeng Rehabil. (2021) 18:31. doi: 10.1186/S12984-020-00801-3

13.

Thapa N Park HJ Yang JG Son H Jang M Lee J et al . The effect of a virtual reality-based intervention program on cognition in older adults with mild cognitive impairment: a randomized control trial. J Clin Med. (2020) 9:1283. doi: 10.3390/Jcm9051283

14.

Amjad I Toor H Niazi IK Pervaiz S Jochumsen M Shafique M et al . Xbox 360 Kinect cognitive games improve slowness, complexity of EEG, and cognitive functions in subjects with mild cognitive impairment: a randomized control trial. Games Health J. (2019) 8:144–52. doi: 10.1089/G4h.2018.0029

15.

Kang JM Kim N Lee SY Woo SK Park G Yeon BK et al . Effect of cognitive training in fully immersive virtual reality on visuospatial function and frontal-occipital functional connectivity in Predementia: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. (2021) 23:E24526. doi: 10.2196/24526

16.

Yang JG Thapa N Park HJ Bae S Park KW Park JH et al . Virtual reality and exercise training enhance brain, cognitive, and physical health in older adults with mild cognitive impairment. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2022) 19:2013300. doi: 10.3390/Ijerph192013300

17.

Baldimtsi E Mouzakidis C Karathanasi EM Verykouki E Hassandra M Galanis E et al . Effects of virtual reality physical and cognitive training intervention on cognitive abilities of elders with mild cognitive impairment. J Alzheimers Dis Rep. (2023) 7:1475–90. doi: 10.3233/Adr-230099

18.

Park JH Liao Y Kim DR Song S Lim JH Park H et al . Feasibility and tolerability of a culture-based virtual reality (VR) training program in patients with mild cognitive impairment: a randomized controlled pilot study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:3030. doi: 10.3390/Ijerph17093030

19.

Zhong D Chen L Feng Y Song R Huang L Liu J et al . Effects of virtual reality cognitive training in individuals with mild cognitive impairment: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. (2021) 36:1829–47. doi: 10.1002/Gps.5603

20.

Cipresso P Giglioli IAC Raya MA Riva G . The past, present, and future of virtual and augmented reality research: a network and cluster analysis of the literature. Front Psychol. (2018) 9:2086. doi: 10.3389/Fpsyg.2018.02086

21.

Folstein MF Folstein SE Mchugh PR . "Mini-mental state". A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. (1975) 12:189–98.

22.

Nasreddine ZS Phillips NA Bédirian V Charbonneau S Whitehead V Collin I et al . The Montreal cognitive assessment, Moca: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. (2005) 53:695–9. doi: 10.1111/J.1532-5415.2005.53221.X

23.

Moher D Liberati A Tetzlaff J Altman DG . Reprint—preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and Meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Phys Ther. (2009) 89:873–80. doi: 10.1093/Ptj/89.9.873

24.

Cummings JJ Bailenson JN . How immersive is enough? A meta-analysis of the effect of immersive technology on user presence. Media Psychol. (2016) 19:272–309. doi: 10.1080/15213269.2015.1015740

25.

Slater M Wilbur S . A framework for immersive virtual environments (FIVE): speculations on the role of presence in virtual environments. Presence Teleop Virt. (1997) 6:603–16.

26.

Higgins JP Altman DG Gøtzsche PC Jüni P Moher D Oxman AD et al . The Cochrane collaboration's tool for assessing risk of Bias in randomised trials. BMJ. (2011) 343:D5928. doi: 10.1136/Bmj.D5928

27.

Atkins D Eccles M Flottorp S Guyatt GH Henry D Hill S et al . Systems for grading the quality of evidence and the strength of recommendations i: critical appraisal of existing approaches the GRADE working group. BMC Health Serv Res. (2004) 4:38. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-4-38

28.

Guyatt GH Oxman AD Vist GE Kunz R Falck-Ytter Y Alonso-Coello P et al . GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. (2008) 336:924–6. doi: 10.1136/Bmj.39489.470347.AD

29.

Cooper H . Research synthesis and Meta-analysis: A step-by-step approach, vol. 2. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications (2015).

30.

Hwang S . Publication bias in meta-analysis: its meaning and analysis. Korean J Hum Dev. (2016) 23:1–19. doi: 10.15284/kjhd.2016.23.1.1

31.

Duval S Tweedie R . Trim and fill: a simple funnel-plot–based method of testing and adjusting for publication Bias in Meta-analysis. Biometrics. (2000) 56:455–63. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341X.2000.00455.x

32.

Babic A Pijuk A Brázdilová L Georgieva Y Raposo Pereira MA Poklepovic Pericic T et al . The judgement of biases included in the category "other Bias" in Cochrane systematic reviews of interventions: a systematic survey. BMC Med Res Methodol. (2019) 19:77. doi: 10.1186/S12874-019-0718-8

33.

Choi W Lee S . The effects of virtual kayak paddling exercise on postural balance, muscle performance, and cognitive function in older adults with mild cognitive impairment: a randomized controlled trial. J Aging Phys Act. (2019) 27:861–70. doi: 10.1123/Japa.2018-0020

34.

Liao YY Tseng HY Lin YJ Wang CJ Hsu WC . Using virtual reality-based training to improve cognitive function, instrumental activities of daily living and neural efficiency in older adults with mild cognitive impairment. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. (2020) 56:47–57. doi: 10.23736/S1973-9087.19.05899-4

35.

Lim EH Kim DS Won YH Park SH Seo JH Ko MH et al . Effects of home based serious game training (brain talk™) in the elderly with mild cognitive impairment: randomized, a single-blind, controlled trial. Brain Neurorehabil. (2023) 16:E4. doi: 10.12786/Bn.2023.16.E4

36.

Park J-H . Effects of virtual reality-based spatial cognitive training on hippocampal function of older adults with mild cognitive impairment. Int Psychogeriatr. (2022) 34:157–63. doi: 10.1017/S1041610220001131

37.

Torpil B Şahin S Pekçetin S Uyanık M . The effectiveness of a virtual reality-based intervention on cognitive functions in older adults with mild cognitive impairment: a single-blind, randomized controlled trial. Games Health J. (2021) 10:109–14. doi: 10.1089/G4h.2020.0086

38.

Fox KC Nijeboer S Dixon ML Floman JL Ellamil M Rumak SP et al . Is meditation associated with altered brain structure? A systematic review and meta-analysis of morphometric neuroimaging in meditation practitioners. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. (2014) 43:48–73. doi: 10.1016/J.Neubiorev.2014.03.016

39.

Petersen RC Negash S . Mild cognitive impairment: an overview. CNS Spectr. (2008) 13:45–53. doi: 10.1017/S1092852900016151

40.

Petersen RC Smith GE Waring SC Ivnik RJ Tangalos EG Kokmen E . Mild cognitive impairment: clinical characterization and outcome. Arch Neurol. (1999) 56:303–8.

41.

Baus O Bouchard S . Moving from virtual reality exposure-based therapy to augmented reality exposure-based therapy: a review. Front Hum Neurosci. (2014) 8:112. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2014.00112

42.

Moreno A Wall KJ Thangavelu K Craven L Ward E Dissanayaka NN . A systematic review of the use of virtual reality and its effects on cognition in individuals with neurocognitive disorders. Alzheimer's Dementia: Translational Res Clin Interventions. (2019) 5:834–50. doi: 10.1016/j.trci.2019.09.016

43.

Lee GJ Bang HJ Lee KM Kong HH Seo HS Oh M et al . A comparison of the effects between 2 computerized cognitive training programs, BetterCog and COMCOG, on elderly patients with MCI and mild dementia: a single-blind randomized controlled study. Medicine (Baltimore). (2018) 97:E13007. doi: 10.1097/Md.0000000000013007

44.

Maeng S Hong JP Kim WH Kim H Cho SE Kang JM et al . Effects of virtual reality-based cognitive training in the elderly with and without mild cognitive impairment. Psychiatry Investig. (2021) 18:619–27. doi: 10.30773/Pi.2020.0446

45.

Zhao Y Feng H Wu X Du Y Yang X Hu M et al . Effectiveness of exergaming in improving cognitive and physical function in people with mild cognitive impairment or dementia: systematic review. JMIR Serious Games. (2020) 8:E16841. doi: 10.2196/16841

46.

Zhu K Zhang Q He B Huang M Lin R Li H . Immersive virtual reality-based cognitive intervention for the improvement of cognitive function, depression, and perceived stress in older adults with mild cognitive impairment and mild dementia: pilot pre-post study. JMIR Serious Games. (2022) 10:E32117. doi: 10.2196/32117

47.

Yang S Chun MH Son YR . Effect of virtual reality on cognitive dysfunction in patients with brain tumor. Ann Rehabil Med. (2014) 38:726–33. doi: 10.5535/Arm.2014.38.6.726

48.

Kim BR Chun MH Kim LS Park JY . Effect of virtual reality on cognition in stroke patients. Ann Rehabil Med. (2011) 35:450–9. doi: 10.5535/Arm.2011.35.4.450

49.

Muñoz J Mehrabi S Li Y Basharat A Middleton LE Cao S et al . Immersive virtual reality Exergames for persons living with dementia: user-centered design study as a multistakeholder team during the COVID-19 pandemic. JMIR Serious Games. (2022) 10:E29987. doi: 10.2196/29987

50.

Rodrigo-Yanguas M Martin-Moratinos M Menendez-Garcia A Gonzalez-Tardon C Royuela A Blasco-Fontecilla H . A virtual reality game (the Secret Trail of moon) for treating attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: development and usability study. JMIR Serious Games. (2021) 9:E26824. doi: 10.2196/26824

51.

Palombi T Galli F Giancamilli F D’Amico M Alivernini F Gallo L et al . The role of sense of presence in expressing cognitive abilities in a virtual reality task: an initial validation study. Sci Rep. (2023) 13:13396. doi: 10.1038/S41598-023-40510-0

52.

Soh DJH Ong CH Fan Q Seah DJL Henderson SL Jeevanandam L et al . Exploring the use of virtual reality for the delivery and practice of stress-management exercises. Front Psychol. (2021) 12:640341. doi: 10.3389/Fpsyg.2021.640341

53.

Samarasinghe HASM Weerasooriya WAMS Weerasinghe GHE Ekanayaka Y Rajapakse R Wijesinghe DPD . Serious games design considerations for people with Alzheimer's disease in developing nations (2017) 2017 IEEE 5th International Conference on Serious Games and Applications for Health (SeGAH). 1–5. doi: 10.1109/Segah.2017.7939301

Summary

Keywords

virtual reality, VR cognitive training, mild cognitive impairment, cognitive rehabilitation, games, meta-analysis

Citation

Yuan P, Chen J, Peng D, Yang Q, Liu B and Lu C (2025) Effectiveness of VR-based cognitive training and games on cognitive rehabilitation in patients with MCI: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Neurol. 16:1691344. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2025.1691344

Received

23 August 2025

Accepted

16 October 2025

Published

07 November 2025

Corrected

15 December 2025

Volume

16 - 2025

Edited by

Pietro Neroni, National Research Council (CNR), Italy

Reviewed by

Silvia Zabberoni, Santa Lucia Foundation (IRCCS), Italy; Lifeng Tang, Ningbo Rehabilitation Hospital, China

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Yuan, Chen, Peng, Yang, Liu and Lu.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Bin Liu, 48224363@qq.com; Chunxia Lu, luchunxia@hunnu.edu.cn

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.