Abstract

Introduction:

Blepharospasm (BSP) is a functionally disabling disease with a marked impact on the quality of life of patients. Botulinum toxin (BoNT) injections have been recommended as first-line therapy for BSP. However, the clinical benefits of BoNT are temporary with only about 8–10 weeks duration of benefit in most patients with BSP. Per previous case reports, regular use of topical frankincense essential oil (FEO) can achieve significant symptom relief and can decrease the frequency of BoNT injections. This trial will explore whether BoNT combined with regular application of FEO can improve clinical outcomes in patients with BSP.

Methods and analysis:

This protocol describes an open-label, randomized controlled trial to be undertaken to evaluate daily topical application of FEO and coconut oil (CO) in patients with BSP. The goal is to enroll 32 patients with BSP who have received immediate BoNT injection in each treatment arm. Only patients who have previously received less than 12 weeks of positive benefits from BoNT therapy will be enrolled. The primary outcome will be the duration of symptom improvement after the intervention with BoNT combined with FEO or CO within the 24-week follow-up period. Symptom improvement is defined as a decrease of one point or more in the Jankovic Rating Scale severity score compared to baseline in patients with BSP. Secondary outcomes will consist of changes in BSP symptom severity, disability, and quality of life from baseline to each time point after the intervention. Safety analysis will be based on the presence of localized skin allergic reactions and adverse events. Outcomes will be assessed at baseline and at weeks 2, 4, 8, 12, 16, 20, and 24 after the therapy begins.

Discussion:

This study will provide evidence that FEO therapy is a promising non-invasive therapy that can be easily combined with BoNT injections to improve clinical outcomes in patients with BSP.

Clinical trial registration:

https://www.chictr.org.cn/, identifier ChiCTR2400091987.

1 Introduction

Blepharospasm (BSP), characterized by involuntary bilateral orbicularis oculi muscle spasms, is the most common type of focal dystonia in Asia (1–3). BSP significantly affects the quality of life of patients through motor and non-motor manifestations (3–6). Currently, BSP treatment remains purely symptomatic, owing to its unknown etiology. Oral medications, such as benzodiazepines, anticholinergics, antimuscarinics, and dopaminergic medications, exert temporary benefits, but these vary from patient to patient, generally lack long-term effectiveness, and result in significant side effects (7). Surgical myectomy is invasive and is usually recommended for patients who do not respond to medication (7). Botulinum toxin (BoNT) injections are widely regarded as the gold standard therapy for patients with BSP; however, the clinical benefits of BoNT injections begin to wear off after 8–10 weeks in most patients (8–11). As a result, most patients must receive reinjections after 12 weeks or 4–5 times per year (7). Therefore, there is an urgent need to develop novel adjunct therapies.

Many studies have shown the transient therapeutic benefits of non-invasive brain stimulation (NIBS), such as repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) and transcranial direct current stimulation (8, 12–15). Recently, Shukla et al. (8) examined whether combined treatment with rTMS and BoNT injections could improve the clinical outcomes in BSP. They recruited 12 patients with BSP and randomly assigned them to real rTMS or sham rTMS treatment groups. The intervention was conducted 1 month after BoNT and lasted for a 2-week course. The combined approach to the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) with a double-cone coil and BoNT could significantly improve motor symptoms, quality of life, and social life at 2 weeks compared with BoNT alone. However, these benefits were no longer evident at 4 weeks after completion of rTMS, suggesting that rTMS may offer an adjunctive benefit in BSP. Although the findings of Shukla et al. (8) are encouraging, the application of NIBS in BSP treatment faces several significant challenges. First, the sample size was small, and the benefits of rTMS appear to be short-term. Second, although studies have reported the ACC, primary motor cortex, and dorsal premotor cortex as potential stimulation targets for BSP treatment, the optimal stimulation target regions remain unclear (12). Finally, NIBS treatment may be inaccessible to some patients because of the high equipment requirements. Therefore, there is a need to explore alternative adjunctive therapies that are non-invasive and easily integrated into standard BoNT regimens. A recent case report described two patients with BSP who used topical frankincense essential oil (FEO) regularly (16). Both patients showed significant symptomatic improvement and a reduced frequency of BoNT type A (BoNT-A) injections. Patient 1 experienced an extension in the injection interval from every 5–8 months to 11 + months and eventually stopped BoNT treatment after starting FEO. The frequency of BoNT injections declined from every 3–4 months to 8 months in patient 2. FEO extracted from Boswellia tree resin has a long history of use in traditional medicine (17). FEO has potential therapeutic effects and treats neurological diseases, such as Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, and multiple sclerosis, through anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effect (18–20). Recent clinical evidence suggests that oxidative stress may contribute to the pathophysiology of dystonia (21). This finding indicates that antioxidant compounds, such as Boswellia extracts, could be relevant in this context. Despite these indications, the application of FEO in the treatment of BSP has not been extensively evaluated. Therefore, it is necessary to explore whether topical FEO may serve as an adjunct treatment to improve clinical outcomes in patients with BSP, so as to exploit its inexpensive and non-invasive nature.

We plan to collect data using this novel combination treatment and assess the efficacy and safety of combining topical FEO with BoNT in patients with BSP.

2 Methods and analysis

2.1 Trial design

We will conduct a single-centre, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Patients diagnosed with BSP receiving BoNT treatment at our centre will be approached. The protocol follows the Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials guidelines (22). Outcomes, including symptom severity, disability, and quality of life, will be evaluated at baseline and at weeks 2, 4, 8, 12, 16, 20, and 24 post intervention. Patients will be asked to complete a self-report questionnaire to document their response to BoNT and the duration of clinical benefits after BoNT treatment. We will recruit only those patients who have received positive benefits from BoNT for less than 12 weeks. We plan to enroll 64 patients and randomly (1:1) assign them to the experimental group (topical FEO combined with BoNT-A injection) or control group [topical coconut oil (CO) combined with BoNT-A injection]. CO will be used as the control because FEO must be diluted 1:1 with CO as the carrier oil (16).

2.2 Study population

All patients who meet the following inclusion criteria will be included: (1) age 18–70 years; (2) a diagnosis of BSP established according to the published criteria by a senior neurologist (2); (3) a Jankovic Rating Scale (JRS) frequency sub-score of ≥3; (4) documented history of at least three subsequent injection cycles or prospective documentation of one injection cycle of BoNT with less than 12 weeks duration of positive benefits with BoNT by a BoNT-experienced physician (23); (5) written consent obtained from participants. The exclusion criteria include: (1) family history or diagnosis of hereditary dystonia, acquired dystonia, tardive dyskinesia, or functional movement disorders; (2) presence of acute intracranial disease (e.g., stroke, intracranial infection) or history of psychiatric disorders, dementia, epilepsy, multiple sclerosis, tic disorder, Parkinson’s disease, severe traumatic brain injury, or other neurological diseases; (3) significant cognitive impairment; (4) exposure to neuroleptics; (5) contraindication to magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

2.3 Objectives and endpoints

Primary objectives: The study primarily aims to evaluate the clinical effects of topical FEO combined with BoNT injections in patients with BSP. Specifically, we will compare the topical FEO group with the CO group in terms of the duration of symptom improvement, quality of life, and self-rating of response to efficacy during a 24-week follow-up. Symptom improvement is defined as a decrease of one point or more in the JRS severity in the JRS severity score relative to baseline in patients with BSP (24). We hypothesized that, unlike the placebo group, topical FEO combined with BoNT will significantly prolong the duration of symptom improvement, improve patient rating of quality of life, and self-rating of response to efficacy, with acceptable safety at the 24-week follow-up.

The primary endpoint is the duration of symptom improvement over 24 weeks, as defined above.

The secondary endpoint of the study is the percentage change from baseline to different time points in the physician rating of the BSP. This involves motor symptom severity, measured by the JRS (25), the Blepharospasm Severity Rating Scale (BSRS) (26), and the Burke Fahn Marsden’s Dystonia Rating Scales (BFMDRS) (27), and quality of life, assessed by the Blepharospasm Disability Index (BSDI) (25), the Short Form-36 Health Survey (SF-36) (28), and the Cranio-cervical Dystonia Questionnaire (CDQ-24) (29). In addition, patient subjective ratings via the Patient Evaluation of Global Response (PEGR) and the incidence of adverse events will be included (30).

2.4 Data measurements

All subjects will undergo MRI before the clinical intervention. Demographics, clinical characteristics, and severity of BSP will be recorded using blepharospasm severity scales. The severity of BSP, quality of life, and self-rating of response to efficacy will be evaluated in each patient at baseline and at weeks 2, 4, 8, 12, 16, 20, and 24 after therapy. Moreover, a 5-min standardised video recording of the facial area will be conducted to assess and document the blink rate and duration of sustained eyelid closure (26). In addition, all subjects will be evaluated with non-motor symptom scales at baseline, at weeks 12 and 24 weeks after the intervention, using the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) (31), Hamilton Rating Scale for Anxiety (HAMA) (32), Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAMD) (33), Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS) (34), and the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) (35). All evaluations applied in the study will be performed at each visit by two evaluators who will be blinded to the clinical information and group assignments of the participants. This will safeguard the objectivity of the evaluation process and ensure the consistency and validity of the assessment results. Figure 1 illustrates the flowchart of the clinical trial procedure, and Table 1 presents an overview of the study.

Figure 1

Clinical trial flow diagram. BoNT-A, botulinum toxin type A; CO, coconut oil; FEO, frankincense essential oil; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; PEGR, Patient Evaluation of Global Response.

Table 1

| Item | Description |

| Study title | Efficacy and safety of combination of frankincense and botulinum toxin in the treatment of blepharospasm: a protocol for a single-centre, open-label, randomized, controlled trial |

| Study design | A single-centre, open-label, randomized, controlled trial will be conducted in 64 eligible BSP patients, and they will be randomly assigned (1:1) into the experimental group (topical FEO combined with BoNT) and control group (topical CO combined with BoNT) for the 24-week follow-up. |

| Primary endpoint | The symptom improvement over a 24-week follow-up period. |

| Secondary endpoints |

|

| Research intervention(s)/Investigational agent(s) | Daily application topical FEO the day after BoNT injection in the experimental group. Daily topical application of CO the day after BoNT injection in the control group. Outcomes will be collected at baseline and different follow-up time points. BoNT: Hengli. FEO/CO: Aromatics International. |

| Study population | Patients aged 18 to 70 years whose efficacy duration of BoNT injection was less than 12 weeks. |

| Sample size | 64 |

| Study duration for individual participants | 24 weeks |

Overview of the study.

BFMDRS, Burke Fahn Marsden’s Dystonia Rating Scales; BoNT, botulinum toxin; BSDI, Blepharospasm Disability Index; BSP, blepharospasm; BSRS, Blepharospasm Severity Rating Scale; CDQ-24, Cranio-cervical Dystonia Questionnaire; CO, coconut oil; FEO, frankincense essential oil; JRS, Jankovic Rating Scale; SF-36, Short Form-36 Health Survey; PEGR, Patient Evaluation of Global Response.

2.5 Safety evaluation

Based on previous studies, the oral use of frankincense occasionally or rarely causes adverse reactions such as eczema, nausea, aggravation of arthralgia, and gastrointestinal symptoms (20, 36, 37). Topical application of FEO has fewer side effects, predominantly in the form of localized skin allergic reactions (38). All adverse events, including their description, duration, severity, and required treatment, will be documented and treated with care. Any serious adverse events will be immediately reported to the chief investigator and ethics committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat–sen University, and the ethics committee will ultimately determine the termination of the study.

2.6 Sample size

The sample size was calculated using the two-sample t-test method in PASS 15 software (NCSS, LLC, Kaysville, Utah, USA), with a two-sided significance level of 0.05 and a power of 0.8. Based on preliminary clinical observations obtained in our center, topical FEO alone was effective in approximately 50% of patients with BSP. This finding, combined with a conservative estimate of efficacy, prompted a reassessment of the required sample size to ensure adequate statistical power. The revision was implemented after trial initiation but prior to completion of participant recruitment, and constitutes an important protocol modification based on internally generated data. To determine the mean and standard deviation (SD) needed for the sample size calculation, we retrospectively analysed data from 61 patients with BSP at our movement disorders clinic who had received standard BoNT-A treatment and met the study’s inclusion criteria. After receiving their last three consecutive BoNT-A injections, these patients experienced clinical benefits for less than 3 months each time, demonstrating consistently unsatisfactory therapeutic effects. The mean duration of clinical benefits was 73.99 days (SD = 14.28). Given that the control group will receive a placebo, there may have been greater variability in the therapeutic effects due to individual response and disease progression; therefore, we decided to round the mean value to 75 days and the SD to 15 (i.e., 75.0 ± 15.0) to ensure robustness in the calculation. In this study, we hypothesized that combining BoNT-A injection with topical FEO would extend the effective duration of symptom relief by 30 days to 105.0 ± 15.0 days. Given an expected effective rate of only 50%, we estimated the mean duration of benefit in the experimental group as 90.0 ± 18.5 days, reflecting a weighted average between responders and non-responders. The resulting sample size calculation indicated N1 = N2 = 25, meaning that 25 participants are required for each group. Considering the participant loss to follow-up, we determined that each group would recruit 32 participants. A professional statistician verified the sample size calculation method. The amended protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat–sen University.

2.7 Randomization and recruitment

The randomization procedure will be managed and documented entirely by an independent statistician who is not engaged in the implementation of the study. Sixty-four random numbers were generated using IBM SPSS Statistics (v.25.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). These random numbers will then be allocated equally to two groups using the visual split-box function in SPSS. Another designated blinded investigator is responsible for assigning participants to different interventions. To ensure allocation concealment, other investigators, including participant recruiters and evaluators, will remain unaware of the randomization results until the study is fully completed. Using this approach, the study will effectively accomplish randomization and allocation concealment, thereby minimizing selection bias and ensuring the validity and reliability of the results.

The intended recruitment period is approximately 2 years and 2 months, from 28 December 2024, to 28 February 2027. The participants will be free to withdraw from the study at any time. The reasons for withdrawal will be documented. If the reason is associated with adverse events, it will be followed up until the issue is completely resolved. Participants who have received other treatments or participated in another program related to BSP therapy during the trial will be considered dropouts.

2.8 Intervention administration

2.8.1 Topical FEO combined with BoNT group

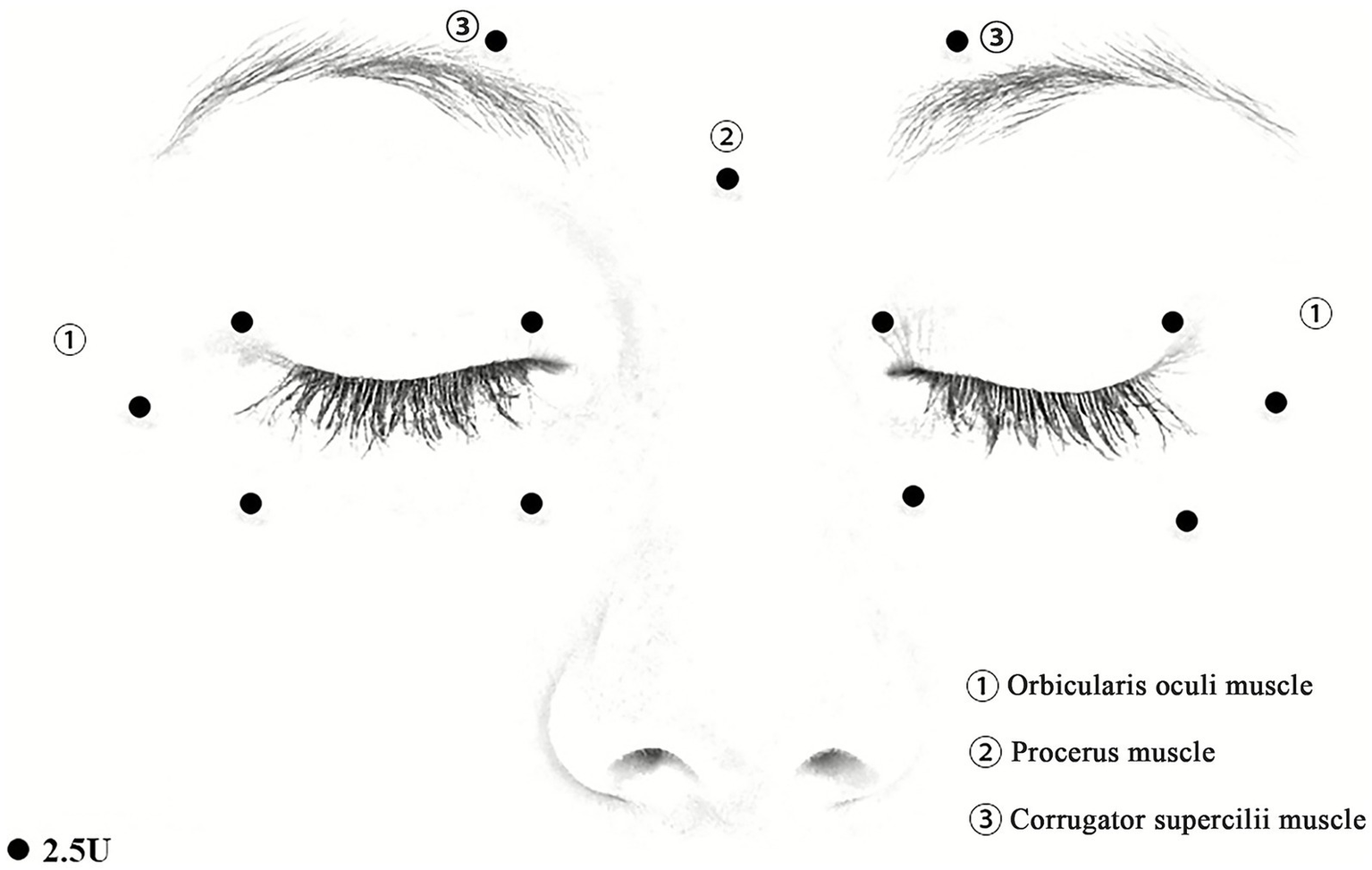

Participants in the experimental group will receive injections of BoNT-A (Hengli, Lanzhou Biological Products Institute, Lanzhou, China; 100 U, diluted in 2 mL saline), using 1 mL syringes and manual targeting techniques. BoNT-A will be routinely administered to the orbicularis oculi muscles at a total of 10 points (5 points on each side). These points encompass the medial and lateral one-third of both the upper and lower eyelids, 2–3 mm from the eyelid margin, and the temporal orbicularis oculi muscle, located 5 mm from the lateral canthus. The corrugator supercilii muscles will receive two injections (one point on each side) located above the inner side of the eyebrows. Additionally, BoNT-A will be injected into the procerus muscle at a central point between the eyebrows. Each point will receive injection of 2.5 U BoNT-A, and the total BoNT-A dosage will be approximately 32.5 U per participant (Figure 2). The injection site and dosage will be adjusted slightly based on the patient’s condition. The next day, participants in the experimental group will begin applying the FEO mixture to the bilateral upper and lower eyelids twice daily, using 0.25 mL of the mixture per application, 0.125 mL for each side. The application will be performed after cleaning the face, and participants will be instructed to gently massage the oil mixture into the skin and rest with their eyes closed to allow absorption.

Figure 2

Schematic diagram of BoNT-A injection sites. (1) Injection sites on the orbicularis oculis. (2) Injection sites on the procerus muscle. (3) Injection sites on the corrugator supercilii muscles. The doses of BoNT-A: 2.5 U/dot.

2.8.2 Topical CO combined with BoNT group

In the control group, the method of injecting BoNT-A and CO will be consistent with that of the experimental group, including site, dosage, and frequency. Participants will be provided with detailed instructions and training on the correct application of the oils, and their adherence to the intervention protocol will be monitored through regular follow-ups. FEO and CO used in the trial are supplied by Aromatics International.1

2.9 Trial assessment and follow-up

Full eligibility criteria will be assessed and confirmed before randomization. Further assessments should be conducted at multiple time points. An overview of the data collection process is provided in Table 2. Data will be collected from all participants until they complete the 24-week follow-up period or discontinue the study.

Table 2

| Description | Screening | Day 0 | 2nd week | 4th week | 8th week | 12th week | 16th week | 20th week | 24th week |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Consent | √ | ||||||||

| Neurological exam | √ | ||||||||

| Medical history | √ | ||||||||

| Inclusion/exclusion | √ | ||||||||

| Randomization | √ | ||||||||

| MRI | √ | ||||||||

| Baseline assessment | √ | ||||||||

| Motor symptom assessment | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

| Quality-of-life assessment | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

| Video recording | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

| PEGR | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||

| Non-motor symptom assessment | √ | √ | √ | ||||||

| Blinded rater evaluation | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| BoNT injection | √ | ||||||||

| FEO/CO application | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||

| Clinical assessments | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Safety assessment | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

Time and events.

BoNT, botulinum toxin; CO, coconut oil; FEO, frankincense essential oil; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; PEGR, Patient Evaluation of Global Response.

Patients will be withdrawn for the follow-up during a 24-week observation period if they meet any of the following three conditions: (1) the subject receives a BoNT-A reinjection during the follow-up period, (2) the JRS score returns to the baseline score, or (3) completion of a 24-week follow-up visit.

2.10 Statistical analysis

Trial analysis will be performed on an intention-to-treat (ITT) population. No interim analyses will be performed. A full statistical analysis plan will be developed before the final analysis.

Assumptions for parametric tests will be evaluated before analysis. Normality will be assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test and Q-Q plots, and homogeneity of variances with Levene’s test. If these assumptions are not met, non-parametric alternatives will be used.

Missing data will be handled under the ITT principle, using all available observations without imputation beyond the last completed visit. Mixed-effects models will be used for repeated-measures secondary outcomes under the missing-at-random assumption. A per-protocol sensitivity analysis will also be conducted.

2.10.1 Baseline demographic characteristics

Age, educational level, MMSE, HAMA, and HAMD scores will be expressed as mean and SD for normally distributed variables or median and interquartile range (IQR) for non-normal continuous variables. Differences between the two groups will be compared using the t-test or Mann–Whitney U-test, as appropriate. Sex will be expressed as frequencies and percentages, and the sex distribution of the participants will be compared using the Pearson χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test.

2.10.2 Primary endpoint analysis

The primary outcome metric of the study, which is the duration of effective symptom relief as measured by the JRS severity subscale, will be analysed using a t-test or Mann–Whitney U-test to compare the differences between the two groups. The difference and its 95% confidence interval (CI) are also reported.

2.10.3 Secondary endpoint analysis

Secondary outcome metrics include the interval between BoNT treatments, improvement rates in motor symptoms (JRS, BSRS, and BFMDRS), quality of life (BSDI, SF-36, and CDQ-24), and subjective efficacy evaluations (PEGR) at different time points. The interval between BoNT-A treatments will be expressed as mean ± SD with differences analyzed using the two-sample t-test if the data follows a normal distribution; otherwise, median and interquartile range will be used, and the Mann–Whitney U-test will be applied. Improvement rates in motor symptoms, quality of life scores, and subjective efficacy evaluations will be expressed as mean ± SD or median and IQR, depending on the normality distribution. Differences between the two groups and their 95% CI will be reported. Outcomes with repeated-measures continuous data will be compared between the groups using repeated-measures ANOVA. Multiple tests will be corrected using Bonferroni correction. All statistical analyses will be performed using SPSS v.25.0 (IBM Corp). p < 0.05 will indicate a statistically significant difference.

2.11 Data safety monitoring plan

Data collection during each study visit and patient safety will be monitored by the principal investigator. A multidisciplinary committee consisting of at least two health professionals will be established to conduct a full review of the study details to determine whether a possible harm to the subject’s safety or any additional harm can be extracted during the study.

3 Discussion

This study will examine whether adding FEO to BoNT therapy can prolong symptom relief. It will also assess whether this combination improves quality of life compared to BoNT alone. In addition, the safety of topical FEO and CO will be evaluated. Sixty-four subjects will be randomized into two groups, with assessments conducted at multiple time points during a 24-week follow-up period. Outcomes will include the duration of symptom improvement, quality of life, and self-rating of response to efficacy, providing evidence of whether FEO therapy is an effective adjunct therapy for the control of BSP symptoms.

However, certain practical issues require clarification. Because FEO has a strong and characteristic odor that cannot be masked even when diluted or sealed, an open-label design was necessary (39). To minimize subjective bias, all assessments will be conducted by two independent blinded evaluators using the same evaluation protocol. Because pure FEO causes irritation when applied directly to the skin, it must be diluted 1:1 with a carrier oil such as CO (16). In this study, CO was chosen as the diluent, but its potential effects on BSP are unknown. Therefore, to control for any influence of CO itself, the control group will receive topical CO alone, applied using the same dosage and massage procedure as in the experimental group.

This study focuses on patients with BSP experiencing shorter relief periods after BoNT treatment, and thus require more frequent injections. Increasing the frequency of BoNT injections leads to higher costs, more side effects, and a greater risk of antibody production, which may result in BoNT resistance and reduced efficacy of subsequent BoNT treatments (40, 41). To address the issue of limited efficacy duration of pretarsal injections in some patients with BSP, Hu et al. (42). Employed a modified BoNT injection method (combining pretarsal with preseptal injections) and compared the efficacy of this method with the pretarsal injections. The study found that pretarsal-preseptal injections achieved a longer duration of response [135.00 (118.50, 153.75) vs. 121.00 (107.00, 135.00) days] than pretarsal injections. In addition, Shukla et al. (8) found that a combined treatment of rTMS to the ACC with a double-cone coil and BoNT could significantly improve motor symptoms 2 weeks after the completion of rTMS treatment compared to BoNT alone. However, the duration of increased efficacy of BoNT injections was limited in both studies. A recent case report showed that topical FEO could prolong the interval between BoNT injections and achieve significant symptom relief in patients with BSP (16). Furthermore, FEO has been proposed as an anti-inflammatory and antioxidant agent that protects neurons and improves motor symptoms in Parkinson’s disease (18). However, whether topical FEO can serve as an effective, low-cost adjunct treatment to significantly increase BoNT remains unknown. Therefore, the primary outcome of the current study is the duration of effective symptom relief within the 24-week observation period, which is defined as a decrease in the JRS severity subscale score by one point or more relative to the baseline (24). If symptom relief is significantly prolonged in the experimental group, this study will provide evidence supporting FEO as an adjunct treatment to potentiate and prolong the effects of BoNT in BSP.

Despite these promising directions, this study has some limitations. In the experimental group, FEO diluted with CO at a 1:1 ratio will be used. Further research should test different concentrations (1:2, 1:3, or 1:5) to determine the optimal concentration associated with positive effects. Second, although FEO may relieve BSP symptoms, further research is required to clarify its potential mechanisms. Third, some patients with BSP experience spontaneous remission, which could affect the results; however, predicting these cases is challenging. Finally, the sensory effects of eyelid massages may contribute to symptom relief. To reduce this bias, the same massage method will be used in the control group.

In conclusion, we propose a study protocol for an open-label, randomized controlled trial to investigate the efficacy and safety of a combination of FEO and BoNT injections in patients with BSP. As a low-cost, non-invasive and easily applicable approach, FEO has the potential to serve as a practical adjunct that may prolong the therapeutic effects of BoNT, and improve symptom control in patients experiencing suboptimal benefit. This trial may therefore provide clinically meaningful evidence to inform a cost-effective and accessible management option for BSP.

Statements

Ethics statement

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat–sen University ([2023] 684). Oral and written informed consent will be obtained from each participant. Significant modifications will be communicated or reported to relevant parties.

Author contributions

SG: Investigation, Visualization, Writing – original draft. YL: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. JZ: Conceptualization, Investigation, Visualization, Writing – original draft. FH: Validation, Writing – review & editing. ZheY: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. YZ: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. ZO: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. ZhiY: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. WZ: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. QZ: Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. GL: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82271300, 82471258, 82101399), Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (2023A1515012739), Science and Technology Program of Guangzhou (2023B03J0466), Southern China International Cooperation Base for Early Intervention and Functional Rehabilitation of Neurological Diseases (2015B050501003 and 2020A0505020004), Shenzhen Science and Technology Research Program (JCYJ20200109114816594), Guangdong Provincial Clinical Research Center for Neurological Diseases (2020B1111170002), Guangdong Province International Cooperation Base for Early Intervention and Functional Rehabilitation of Neurological Diseases (2020A0505020004), Guangzhou Major Difficult and Rare Diseases Project (2024MDRD02), Guangdong Provincial Engineering Center for Major Neurological Disease Treatment, Guangdong Provincial Translational Medicine Innovation Platform for Diagnosis and Treatment of Major Neurological Disease, Guangzhou Clinical Research and Translational Center for Major Neurological Diseases.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.cn) for English language editing.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

- ACC

anterior cingulate cortex

- BFMDRS

Burke Fahn Marsden’s Dystonia Rating Scales

- BoNT

botulinum toxin

- BoNT-A

botulinum toxin type A

- BSDI

Blepharospasm Disability Index

- BSP

blepharospasm

- BSRS

Blepharospasm Severity Rating Scale

- CDQ-24

Cranio-cervical Dystonia Questionnaire

- CI

confidence interval

- CO

coconut oil

- FEO

frankincense essential oil

- HAMA

Hamilton Rating Scale for Anxiety

- HAMD

Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression

- IQR

interquartile range

- ITT

intention-to-treat

- JRS

Jankovic Rating Scale

- MMSE

Mini-Mental State Examination

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- NIBS

non-invasive brain stimulation

- PEGR

Patient Evaluation of Global Response

- PSQI

Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index

- rTMS

repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation

- SD

standard deviation

- SF-36

Short Form-36 Health Survey

- Y-BOCS

Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale

Glossary

Footnotes

References

1.

Medina A Nilles C Martino D Pelletier C Pringsheim T . The prevalence of idiopathic or inherited isolated dystonia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mov Disord Clin Pract. (2022) 9:8–868. doi: 10.1002/mdc3.13524

2.

Defazio G Hallett M Jinnah HA Berardelli A . Development and validation of a clinical guideline for diagnosing blepharospasm. Neurology. (2013) 81:236–40. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31829bfdf6

3.

Defazio G Hallett M Jinnah HA Conte A Berardelli A . Blepharospasm 40 years later. Mov Disord. (2017) 32:498–509. doi: 10.1002/mds.26934

4.

Stamelou M Edwards MJ Hallett M Bhatia KP . The non-motor syndrome of primary dystonia: clinical and pathophysiological implications. Brain. (2012) 135:1668–81. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr224

5.

Ferrazzano G Berardelli I Conte A Baione V Concolato C Belvisi D et al . Motor and non-motor symptoms in blepharospasm: clinical and pathophysiological implications. J Neurol. (2019) 266:2780–5. doi: 10.1007/s00415-019-09484-w

6.

Romano R Bertolino A Gigante A Martino D Livrea P Defazio G . Impaired cognitive functions in adult-onset primary cranial cervical dystonia. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. (2014) 20:162–5. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2013.10.008

7.

Yen MT . Developments in the treatment of benign essential blepharospasm. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. (2018) 29:440–4. doi: 10.1097/icu.0000000000000500

8.

Shukla AW Hu W Legacy J Deeb W Hallett M . Combined effects of rTMS and botulinum toxin therapy in benign essential blepharospasm. Brain Stimul. (2018) 11:645–7. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2018.02.004

9.

Ainsworth JR Kraft SP . Long-term changes in duration of relief with botulinum toxin treatment of essential blepharospasm and hemifacial spasm. Ophthalmology. (1995) 102:2036–40. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(95)30757-9

10.

Streitová H Bareš M . Long-term therapy of benign essential blepharospasm and facial hemispasm with botulinum toxin A: retrospective assessment of the clinical and quality of life impact in patients treated for more than 15 years. Acta Neurol Belg. (2014) 114:285–91. doi: 10.1007/s13760-014-0285-z

11.

Duarte GS Rodrigues FB Marques RE Castelão M Ferreira J Sampaio C et al . Botulinum toxin type a therapy for blepharospasm. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2020) 11:Cd004900. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004900.pub3

12.

Morrison-Ham J Clark GM Ellis EG Cerins A Joutsa J Enticott PG et al . Effects of non-invasive brain stimulation in dystonia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. (2022) 15:17562864221138144. doi: 10.1177/17562864221138144

13.

Kranz G Shamim EA Lin PT Kranz GS Voller B Hallett M . Blepharospasm and the modulation of cortical excitability in primary and secondary motor areas. Neurology. (2009) 73:2031–6. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181c5b42d

14.

Kranz G Shamim EA Lin PT Kranz GS Hallett M . Transcranial magnetic brain stimulation modulates blepharospasm: a randomized controlled study. Neurology. (2010) 75:1465–71. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181f8814d

15.

Trebossen V Bouaziz N Benadhira R Januel D . Transcranial direct current stimulation for patients with benign essential blepharospasm: a case report. Neurol Sci. (2017) 38:201–2. doi: 10.1007/s10072-016-2703-x

16.

Baker MJ Harrison AR Lee MS . Possible role of frankincense in the treatment of benign essential blepharospasm. Am J Ophthalmol Case Rep. (2023) 30:101848. doi: 10.1016/j.ajoc.2023.101848

17.

Abdel-Tawab M Werz O Schubert-Zsilavecz M . Boswellia serrata: an overall assessment of in vitro, preclinical, pharmacokinetic and clinical data. Clin Pharmacokinet. (2011) 50:349–69. doi: 10.2165/11586800-000000000-00000

18.

Doaee P Rajaei Z Roghani M Alaei H Kamalinejad M . Effects of Boswellia serrata resin extract on motor dysfunction and brain oxidative stress in an experimental model of Parkinson's disease. Avicenna J Phytomed. (2019) 9:281–90. PMID:

19.

Siddiqui A Shah Z Jahan RN Othman I Kumari Y . Mechanistic role of boswellic acids in Alzheimer's disease: emphasis on anti-inflammatory properties. Biomed Pharmacother. (2021) 144:112250. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2021.112250

20.

Stürner KH Stellmann JP Dörr J Paul F Friede T Schammler S et al . A standardised frankincense extract reduces disease activity in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (the SABA phase IIa trial). J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. (2018) 89:330–8. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2017-317101

21.

Koptielow J Szyłak E Koptielowa A Sarnowska M Kapica-Topczewska K Adamska-Patruno E et al . Dystonia versus redox balance: a preliminary assessment of oxidative stress in patients. Antioxidants. (2025) 14:1052. doi: 10.3390/antiox14091052

22.

Chan AW Tetzlaff JM Gøtzsche PC Altman DG Mann H Berlin JA et al . SPIRIT 2013 explanation and elaboration: guidance for protocols of clinical trials. BMJ. (2013) 346:e7586. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e7586

23.

Volkmann J Mueller J Deuschl G Kühn AA Krauss JK Poewe W et al . Pallidal neurostimulation in patients with medication-refractory cervical dystonia: a randomised, sham-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. (2014) 13:875–84. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(14)70143-7

24.

Jankovic J Comella C Hanschmann A Grafe S . Efficacy and safety of incobotulinumtoxinA (NT 201, Xeomin) in the treatment of blepharospasm-a randomized trial. Mov Disord. (2011) 26:1521–8. doi: 10.1002/mds.23658

25.

Jankovic J Kenney C Grafe S Goertelmeyer R Comes G . Relationship between various clinical outcome assessments in patients with blepharospasm. Mov Disord. (2009) 24:407–13. doi: 10.1002/mds.22368

26.

Defazio G Hallett M Jinnah HA Stebbins GT Gigante AF Ferrazzano G et al . Development and validation of a clinical scale for rating the severity of blepharospasm. Mov Disord. (2015) 30:525–30. doi: 10.1002/mds.26156

27.

Burke RE Fahn S Marsden CD Bressman SB Moskowitz C Friedman J . Validity and reliability of a rating scale for the primary torsion dystonias. Neurology. (1985) 35:73–7. doi: 10.1212/wnl.35.1.73

28.

Brazier JE Harper R Jones NM O'Cathain A Thomas KJ Usherwood T et al . Validating the SF-36 health survey questionnaire: new outcome measure for primary care. BMJ. (1992) 305:160–4. doi: 10.1136/bmj.305.6846.160

29.

Müller J Wissel J Kemmler G Voller B Bodner T Schneider A et al . Craniocervical dystonia questionnaire (CDQ-24): development and validation of a disease-specific quality of life instrument. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. (2004) 75:749–53. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2003.013441

30.

Wissel J Müller J Dressnandt J Heinen F Naumann M Topka H et al . Management of spasticity associated pain with botulinum toxin A. J Pain Symptom Manag. (2000) 20:44–9. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(00)00146-9

31.

Folstein MF Folstein SE McHugh PR . "mini-mental state". A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. (1975) 12:189–98. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6

32.

Hamilton M . The assessment of anxiety states by rating. Br J Med Psychol. (1959) 32:50–5. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8341.1959.tb00467.x

33.

Hamilton M . A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. (1960) 23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56

34.

Goodman WK Price LH Rasmussen SA Mazure C Fleischmann RL Hill CL et al . The Yale-Brown obsessive compulsive scale. I. Development, use, and reliability. Arch Gen Psychiatry. (1989) 46:1006–11. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1989.01810110048007

35.

Buysse DJ Reynolds CF Monk TH Berman SR Kupfer DJ . The Pittsburgh sleep quality index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. (1989) 28:193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4

36.

Kimmatkar N Thawani V Hingorani L Khiyani R . Efficacy and tolerability of Boswellia serrata extract in treatment of osteoarthritis of knee-a randomized double blind placebo controlled trial. Phytomedicine. (2003) 10:3–7. doi: 10.1078/094471103321648593

37.

Sengupta K Alluri KV Satish AR Mishra S Golakoti T Sarma KV et al . A double blind, randomized, placebo controlled study of the efficacy and safety of 5-Loxin for treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee. Arthritis Res Ther. (2008) 10:R85. doi: 10.1186/ar2461

38.

Efferth T Oesch F . Anti-inflammatory and anti-cancer activities of frankincense: targets, treatments and toxicities. Semin Cancer Biol. (2022) 80:39–57. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2020.01.015

39.

Chen X Yang D Huang L Li M Gao J Liu C et al . Comparison and identification of aroma components in 21 kinds of frankincense with variety and region based on the odor intensity characteristic spectrum constructed by HS-SPME-GC-MS combined with E-nose. Food Res Int. (2024) 195:114942. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2024.114942

40.

Greene P Fahn S Diamond B . Development of resistance to botulinum toxin type a in patients with torticollis. Mov Disord. (1994) 9:213–7. doi: 10.1002/mds.870090216

41.

Bellows S Jankovic J . Immunogenicity associated with botulinum toxin treatment. Toxins. (2019) 11:491. doi: 10.3390/toxins11090491

42.

Hu J Mu Q Ma F Wang H Chi L Shi M . Combination of pretarsal and preseptal botulinum toxin injections in the treatment of blepharospasm: a prospective nonrandomized clinical trial. Am J Ophthalmol. (2024) 270:19–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2024.10.007

Summary

Keywords

blepharospasm, botulinum toxins, clinical trial protocol, frankincense, randomized controlled trial

Citation

Gong S, Luo Y, Zhang J, Huang F, Yang Z, Zhang Y, Ou Z, Yan Z, Zhang W, Zhou Q and Liu G (2025) Efficacy and safety of combination of frankincense and botulinum toxin in the treatment of blepharospasm: a protocol for a single-centre, open-label, randomized, controlled trial. Front. Neurol. 16:1693914. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2025.1693914

Received

27 August 2025

Revised

21 November 2025

Accepted

21 November 2025

Published

01 December 2025

Volume

16 - 2025

Edited by

Marcello Iriti, University of Milan, Italy

Reviewed by

Helio A. G. Teive, Federal University of Paraná, Brazil

Maheswari Eluru, Arizona State University, United States

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Gong, Luo, Zhang, Huang, Yang, Zhang, Ou, Yan, Zhang, Zhou and Liu.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Gang Liu, liug26@mail.sysu.edu.cn; Qian Zhou, zhouq49@mail.sysu.edu.cn

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.