Abstract

Background:

Migraine is a common comorbidity in patients with epilepsy, with a comorbidity rate ranging from 9.3 to 34.7%. Transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation (taVNS) is an emerging therapy used in both epilepsy and migraine treatment. However, there are currently no randomized controlled studies (RCTs) using taVNS for epilepsy complicated with migraine.

Objective:

In this study, we evaluated the effect of taVNS as an adjuvant therapy on patients with comorbid epilepsy and migraine.

Methods:

Forty comorbid patients (taVNS n = 20, tanVNS n = 20) were recruited and randomly grouped. The taVNS group received the true stimulus, whereas the tanVNS group received a pseudostimulus. Outcome assessment was performed at baseline and 24 weeks after initiation. We used t-test and non-parametric tests to analyse the data.

Results:

The frequencies of migraine attacks and seizures significantly decreased in the taVNS group from baseline to 24 weeks (migraine attack frequency, p = 0.002; seizure frequency, p = 0.004), and so did in Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS) score (p < 0.001) and Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS) score (p < 0.001). The QOLIE-31 scores increased after 24 weeks of taVNS treatment (p = 0.028). Moreover, taVNS reduced the EEG power spectrum in four frequency bands at 16 electrode locations in comparison between groups (p < 0.05).

Conclusion:

In comorbid patients in our groups, taVNS can decrease the frequency of seizures, improve mood and quality of life, and reduce the EEG power spectrum.

1 Introduction

Epilepsy and migraine are both common neurological disorders with paroxysmal, chronic and recurrent clinical manifestations (1). Epilepsy is characterized by recurrent seizures, which are brief episodes of involuntary movement that may involve a part of the body (partial) or the entire body (generalized) and are sometimes accompanied by loss of consciousness and control of bowel or bladder function (1). Migraine attacks are mainly unilateral pulsatile headaches, and are sometimes accompanied by nausea and vomiting (1). In particular, migraine is one of the most common comorbid neurological conditions in patients with epilepsy (2–6). Epidemiological surveys have shown that the incidence of migraine in epilepsy patients ranges from 9.3 to 34.7% (7–9), moreover, it has been suggested that migraine, a common comorbidity in patients with epilepsy, exacerbates epilepsy, and vice versa (10–14). Therefore, patients with comorbid epilepsy and migraine suffer long-term pain, and their quality of life is reduced.

Vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) has been approved by the FDA as a treatment for drug-resistant epilepsy in patients aged >12 years, and it is also used to treat migraine (15–17). However, the electrode implantation device used in traditional VNS may cause some inconveniences, such as surgical wound infection and rejection reactions, and the cost of therapy is high (18). To improve cost-effectiveness and reduce invasiveness, transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation (taVNS) was developed on the basis of traditional VNS (19, 20). Instead of the implantation of a stimulator in the chest, taVNS involves wearing a lightweight stimulator in the concha auricula to stimulate the auricular branch of the vagus nerve (ABVN), which can ameliorate seizures and migraines (19, 20). The auricular concha region is innervated mainly by the ABVN, which is often termed Alderman’s nerve or Arnold’s nerve. Previous studies have shown that the ABVN can project directly to the nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS) and then further connect with other brain regions, such as the locus coeruleus (LC), thalamus, and prefrontal cortex (21–25). Moreover, taVNS can modulate cortical networks including the default mode network (DMN), salience network, and central executive network, among which the DMN has been the most studied (26–32).

TaVNS has been shown in clinical studies to alleviate epilepsy and migraine. A meta-analysis and systematic review of nine clinical studies (including 788 patients with epilepsy) and eight preclinical studies revealed that taVNS was effective in treating patients with epilepsy (33). In 59 migraine patients, both pain intensity and migraine attack frequency were significantly reduced after 4 weeks of taVNS treatment (34). In this study, we applied taVNS as an adjunctive therapy for comorbid epilepsy and migraine and evaluated its effects. Electroencephalograms (EEGs) are widely used to monitor epilepsy and migraine patients, and the EEG power spectrum can be used to evaluate the effect of VNS (35). Power spectrum analysis assumes that the EEG is a linear combination of simple vibrations at a specific frequency, and involves the decomposition of each frequency component of the EEG signal to determine its magnitude (or power) (35). Therefore, we use EEG power spectrum analysis as one of the approaches in this study.

By comparing the frequency of epileptic seizures and migraine attacks, Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS) and Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS) scores, and quality of life scores, we evaluate the effect of taVNS as an adjuvant therapy in patients with comorbid epilepsy and migraine. By analysing the EEG power spectrum, we explore changes in different frequency bands after taVNS treatment in an attempt to identify potential evaluation indicators.

2 Method

2.1 Study design

This randomized controlled trial included patients who were admitted to the hospital from September 2023 to June 2024. The protocol was approved by the Clinical Trial Ethics Committee of Sichuan Provincial People’s Hospital (Number 430, 2023). Informed consent was obtained from all the patients.

In a previous RCT of patients with only epilepsy, after 24 weeks of treatment with taVNS, 8/47 patients were seizure free, and 19/47 patients had a reduced seizure frequency (36). Referring to it, we chose a sample size of approximately 42 comorbid patients to achieve a power of 0.80 and a standardized effect size of 0.6 (seizure frequency: times/month). Patients with comorbid epilepsy and migraine were randomly allocated to the true stimulation group (taVNS group) or the pseudostimulation group (transcutaneous auricular nonvagus nerve stimulation (tanVNS) group) at a 1:1 ratio.

At the beginning of enrolment, the patients were given a stimulator. The patients were instructed to learn the site of true stimulation or pseudostimulation, depending on the group assignment (the physician did not disclose to the patients whether he or she was assigned to the taVNS group or tanVNS group). Patients were required to keep a detailed diary to report the frequency of seizures and migraine attacks. This trial included a 24-week treatment period. Outcome assessment was performed at baseline and 24 weeks after initiation. A total of 40 patients were ultimately included in the analysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Flowchart of the study.

2.2 Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria for the patient cohort were as follows: (1) met the diagnostic criteria for epilepsy comorbid with migraine (37), and aged 18 to 65 years (to minimize confounding variables related to age and potential serious diseases); (2) had focal preserved consciousness seizures or focal impaired consciousness seizures (not including focal-to-bilateral tonic–clonic seizures); (3) had an average of two or more seizures per month with mild and short-lived symptoms that did not affect daily life or work; (4) took only valproic acid (VPA) or levetiracetam (LEV) as monotherapy (VPA and LEV, broad-spectrum antiepileptic drugs that are more widely used than other antiepileptic drugs in primary care, can not only treat focal epilepsy but also prevent migraine attacks; as some patients were women of childbearing age, LEV was given) for at least 2 years, with no need to adjust the medication; (5) had migraines for at least 6 months, with at least two migraine attacks per month, but no use of preventive headache medication in the past 3 months; (6) used no psychoactive or vasoactive drugs in the past 3 months; (7) had normal cognitive function (Montreal Cognitive Assessment score equal to or greater than 26 points); and (8) fully understood the trial process, were willing to comply with and participate in this study, and provided informed consent.

The exclusion criteria for the patient cohort were as follows: (1) had mental illness, progressive nervous system disease, brain trauma, or serious physical illness (such as cardiopulmonary diseases); (2) were pregnant or lactating, or planned to become pregnant during the trial period; (3) had migraine caused by other diseases; (4) had other types of headaches, such as tension headaches; (5) had migraine attacks that occurred within 48 h before the trial; (6) had any other chronic pain condition; (7) had severe head deformities or intracranial lesions; or (8) had significant mood disorders, as indicated by an SAS score >50 or SDS score >53.

The withdrawal criteria were as follows: (1) severe adverse reactions after taVNS; (2) participation in other studies that affected brain function; or (3) inability to continue the study for any reason.

2.3 Randomization and blinding

Eligible patients who provided consent were given a unique identification number, which was only known by the researchers. Computer-based randomization software was used to randomly divided the patients into the taVNS group and the tanVNS group. For blinding, the group allocations were concealed until the final data analysis report was completed.

2.4 Interventions

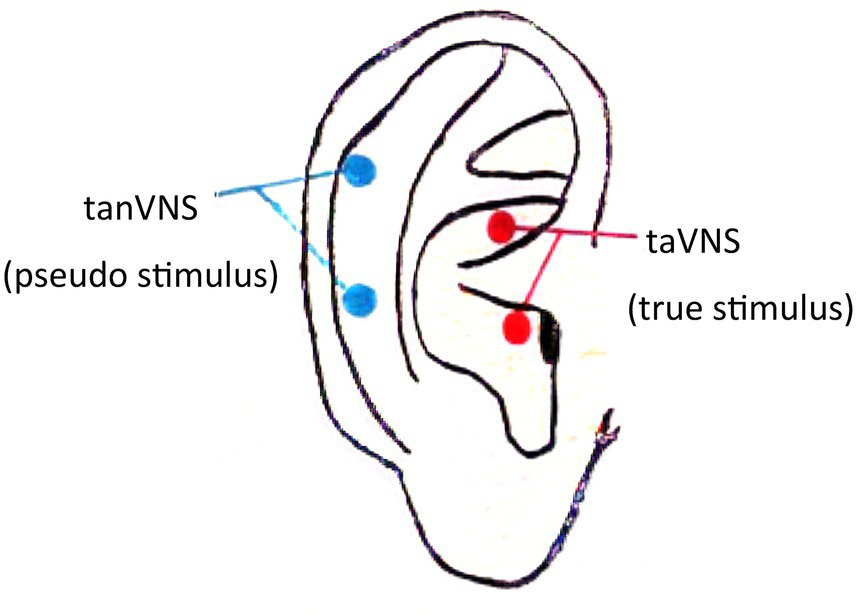

A transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulator (TENS sm; Suzhou Medical Appliance Co. Ltd., China) was used in this study. The electrode clamp was designed with three carbon-impregnated silicone electrode tips, one of which acted as the common terminal end and the other two of which were designed to contact the two skin surface points at the triangular fossa of the auricle (taVNS, true stimulus) and the outer ear canal (tanVNS, pseudo stimulus). Only one of the two tips was activated in a single clamp. The stimulation electrodes were made of conductive rubber with a diameter of 5 mm. The specific stimulation site was selected according to a study by Rong et al. (38) (see Figure 2). The stimulation parameters were as follows: frequency of 20 Hz [previous studies revealed that both 1 Hz and 20 Hz can treat migraine (39, 40), and 20–30 Hz has used to treat epilepsy (36); the patients in our study had epilepsy comorbid with migraine, so we chose 20 Hz as the stimulation frequency]; constant voltage, continuous current output; dense-sparse waves; wave width of 0.2 ms; electrical stimulation intensity under the threshold that the patient could tolerate without producing a sharp pain sensation (a sensation similar to the pulsation of blood vessels); range of 4–12 mA; duration of 20 min; three times a day (at approximately 8 in the morning, 12 noon, and 8 at night, eliminating the interference of circadian rhythm); 24-week treatment period. Professional technicians instructed the patients on how to use the stimulators at initiation; then, the patients took the stimulators home and used them regularly as instructed.

Figure 2

ABVN stimulation site.

2.5 Outcome measures

Seizure frequency and migraine attack frequency were determined at baseline and after 24 weeks according to the patients’ diaries. The format and detailed content of the diaries were described in previous studies (41, 42).

Scalp EEG recordings were made using 18 leads [16 channel EEGs (i.e., Fp1/2, F3/4/7/8, C3/4, P3/4, O1/2, and T3/4/5/6) and 2 reference electrodes], and an Australian COMPUMEDICS instrument was used to record a set of digital video EEGs at a sampling rate of 256 Hz. During the examination, the scalp was fully exposed, and conductive cream was applied to the disc electrode. If the impedance was too high, the scalp was wiped with alcohol. Single or dual cameras were used to monitor the behaviour of the patients while they were awake for 2–4 h.

EEG power spectrum analysis was conducted via the ZN500 EEG topography real-time processing system produced by Chengdu Intelligent Electronics Industry Co., Ltd. Four standard EEG frequency bands were selected: the α wave (8–13 Hz, 30–50 μV), β wave (14–30 Hz, 5–30 μV), θ wave (4–7 Hz, 10–40 μV) and δ wave (0.5–3.5 Hz, 10–20 μV) bands. The EEG data were processed as follows: the original EEG data were filtered through a bandpass filter (1–46 Hz) to remove interference, and 10 s of the head and tail of the data were removed to eliminate additional interference. After the processing was completed, a doctor who specialized in EEG analysis reviewed the video and selected four 10-s segments that showed intermittent epileptic discharges with few interfering factors (excluding eyeblinks and movements manually) for each patient. After selecting these segments, the power of the α wave, β wave, θ wave and δ wave at 16 electrode locations was calculated via computer analysis and statistical processing (fast Fourier transformation). Eventually, the absolute power of each frequency band at 16 electrode locations before and after taVNS or tanVNS treatment was calculated for each group.

Anxiety was measured via the SAS. The statistical index used was the total score. The final score was the crude score multiplied by 1.25.

Depression was measured via the SDS. The statistical index used was the total score. The final score was the crude score multiplied by 1.25.

Quality of life was measured by the Quality of Life in Epilepsy-31 Inventory (QOLIE-31). This scale includes 31 questions across 7 subscales, including seizure worry, overall quality of life, emotional well-being, cognitive, energy/fatigue, medication effects, social function and overall score. First, the raw precoded numeric values of the items were converted to 0–100 point scores (labelled “subtotal”). Next, the subtotal scores for each scale (marked “total”) were summed. Finally, each “total” score was divided by the number of items that the respondent answered within each scale to obtain the “final score.” The possible range of the final score for each scale was 0 to 100 points. Higher scores reflected better quality of life, whereas lower scores indicated worse quality of life. In this study, we used the Chinese version of the QOLIE-31-P because of its satisfactory reliability and validity (Cronbach’s alpha coefficient ranging from 0.627 to 0.898) (43).

2.6 Quality control and trial monitoring

Before the initiation of the trial, the researchers formulated an investigator’s brochure, standard operating procedures and detailed research plan. All the staff participated in special training about patient enrolment, completion of the case report form and use of the stimulator. Each time a patient used the stimulator, the researchers engaged in a video call with the patient to ensure the accuracy of electrode placement. Moreover, the stimulation parameters and duration of use were recorded under the supervision of the patient’s family members. The final report was produced in accordance with the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) 2010 guidelines for nonpharmaceutical interventions. The patients were informed that they could receive doctor consultations throughout the entire study period. They were also told they could also receive a physical examination and an auricular vagus nerve stimulator for free if they completed the study. Appendix S1 provides the CONSORT checklist in detail.

2.7 Statistical analysis

The raw data from the seizure diary, migraine attack diary, and medical records were entered into Microsoft Excel (Office 2021). All the statistical calculations were performed via SPSS v.27.0. The seizure frequency, migraine attack frequency, EEG power spectrum, SAS score, SDS score and QOLIE-31 score at baseline and after 24 weeks of treatment were compared between the groups. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to evaluate whether variables followed a normal distribution. Continuous variables are expressed as the means ± SDs or medians ± IQRs, and categorical variables are presented as frequencies and percentages. The normally distributed variables were compared via t tests, whereas the nonnormally distributed variables were analysed via non-parametric tests. p < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

3 Results

3.1 Clinical characteristics

A total of 40 patients (20 taVNS, 20 tanVNS) were ultimately included in Neurology Outpatient Department. All the patients had focal seizures. The age range of the patients was 21 to 53 years, and the duration of disease was 5–28 years in the taVNS group and 6–34 years in the tanVNS group (Table 1). There were no differences in gender (p = 0.75), age (p = 0.58) or course of disease (p = 0.93) between the two groups. The specific EEG was provided in Supplementary Figure S1.

Table 1

| Patients | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | taVNS | tanVNS | ||

| Total (numbers) | 40 | 20 | 20 | |

| Sex | Male (numbers) | 19 | 9 | 10 |

| Female (numbers) | 21 | 11 | 10 | |

| p | / | 0.75 | ||

| Age (years) | Range | 21–53 | 21–46 | 24–53 |

| Mean ± SD | 36.95 ± 6.81 | 36.35 ± 7.23 | 37.55 ± 6.50 | |

| p | / | 0.58 | ||

| Course (years) | Range | 5–34 | 5–28 | 6–34 |

| Mean ± SD | 16.55 ± 6.44 | 16.55 ± 6.44 | 16.35 ± 7.02 | |

| p | / | 0.93 | ||

Clinical characteristics of patients.

3.2 Evaluation of the therapeutic effect of taVNS

3.2.1 The frequency of migraine attacks and seizures in the taVNS group and tanVNS group of patients before and after treatment

In Table 2, the frequencies of migraine attacks and seizures significantly decreased in the taVNS group from baseline to 24 weeks (migraine attack frequency, p = 0.002; seizure frequency, p = 0.004).

Table 2

| Attacks | Groups | Frequency per month (Medians ± IQR) | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 W | 24 W | Δ = 0 W–24 W | |||

| Migraine | taVNS | 3.00 ± 1.75 | 2.00 ± 1.00 | 1.50 ± 2.75 | 0.002 |

| tanVNS | 2.00 ± 0.75 | 2.00 ± 1.00 | 0.00 ± 2.00 | ||

| Seizure | taVNS | 2.00 ± 1.00 | 1.00 ± 1.00 | 2.00 ± 0.00 | 0.004 |

| tanVNS | 2.00 ± 0.75 | 1.00 ± 0.75 | 1.00 ± 1.00 | ||

The frequency of migraine attacks and seizures in taVNS group and tanVNS group before and after treatment.

All data were not normally distributed, so non-parametric test (Mann–Whitney U test) was used. p < 0.05 was considered significant difference. taVNS, transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation; tanVNS, transcutaneous auricular non-vagus nerve stimulation; W, weeks.

3.2.2 SAS and SDS scores of the taVNS group and tanVNS group before and after treatment

In Table 3, the SAS and SDS scores in the taVNS group significantly decreased from baseline to 24 weeks (p < 0.001).

Table 3

| Scores | Groups | Means ± SD or medians ± IQRa | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 W | 24 W | Δ = 0 W–24 W | |||

| SAS | taVNS | 47.00 ± 5.00a | 40.00 ± 5.50a | 7.00 ± 2.75a | <0.001 |

| tanVNS | 46.00 ± 4.75a | 44.55 ± 2.72 | 0.30 ± 4.26 | ||

| SDS | taVNS | 47.85 ± 2.85 | 38.35 ± 2.87 | 9.50 ± 2.78 | <0.001 |

| tanVNS | 46.10 ± 2.90 | 43.25 ± 3.27 | 2.85 ± 4.15 | ||

The scores of SAS and SDS in taVNS group and tanVNS group before and after treatment.

SAS, Self-Rating Anxiety Scale; SDS, Self-Rating Depression Scale; taVNS, transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation; tanVNS, transcutaneous auricular non-vagus nerve stimulation; W, weeks.

Indicates medians ± IQR. Δ SAS scores were not normally distributed so non-parametric test (Mann–Whitney U test) was used. Δ SDS scores were normally distributed with homogeneous variance, so independent-samples t-test was used. p < 0.05 was considered significant difference.

3.2.3 QOLIE-31 scores of the taVNS group and the tanVNS group before and after treatment

In Table 4, there were significant increases in QOLIE-31 overall scores of taVNS group (p = 0.028). In the specific sub-items, seizure worry (p = 0.020), energy/fatigue (p = 0.001), and medication effects (p = 0.017) showed significant increases in taVNS group. While overall quality of life (p = 0.888), emotional well-being (p = 0.761), or social function (p = 0.075) did not.

Table 4

| Items | Groups | Medians ± IQR or means ± SDa | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 W | 24 W | Δ = 24 W–0 W | |||

| Seizure worry | taVNS | 50.50 ± 15.00 | 60.15 ± 8.89a | 2.00 ± 17.17 | 0.020 |

| tanVNS | 59.28 ± 5.55a | 60.33 ± 7.10a | 1.05 ± 7.46a | ||

| Overall quality of life | taVNS | 45.84 ± 8.33 | 54.17 ± 18.33 | 0.00 ± 10.00 | 0.888 |

| tanVNS | 53.33 ± 10.00 | 55.00 ± 0.00 | 3.67 ± 8.84a | ||

| Emotional well-being | taVNS | 50.00 ± 3.33 | 51.17 ± 5.11a | 0.00 ± 5.84 | 0.761 |

| tanVNS | 50.00 ± 6.66 | 53.33 ± 3.33 | 0.00 ± 3.33 | ||

| Energy/fatigue | taVNS | 47.92 ± 8.33 | 51.87 ± 6.26a | 4.17 ± 8.34 | 0.001 |

| tanVNS | 50.00 ± 3.13 | 47.92 ± 4.17 | 0.00 ± 11.45 | ||

| Cognitive | taVNS | 49.90 ± 2.91a | 52.47 ± 5.10a | 0.00 ± 5.55 | 0.031 |

| tanVNS | 53.40 ± 3.74a | 52.33 ± 5.02a | 0.00 ± 7.02 | ||

| Medication effects | taVNS | 50.84 ± 8.33 | 58.33 ± 8.38a | 3.34 ± 13.34 | 0.017 |

| tanVNS | 56.67 ± 8.33 | 56.58 ± 7.12a | 0.50 ± 8.20a | ||

| Social function | taVNS | 55.93 ± 5.39a | 60.00 ± 10.50 | 0.00 ± 4.00 | 0.075 |

| tanVNS | 57.43 ± 4.86a | 58.00 ± 2.50 | 0.23 ± 4.66a | ||

| Overall score | taVNS | 50.97 ± 1.80 | 54.40 ± 4.53a | 2.46 ± 7.30 | 0.028 |

| tanVNS | 53.80 ± 2.99a | 54.26 ± 2.82 | 0.25 ± 3.18a | ||

The score of QOLIE-31 in taVNS group and tanVNS group before and after treatment.

SAS, Self-Rating Anxiety Scale; SDS, Self-Rating Depression Scale; taVNS, transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation; tanVNS, transcutaneous auricular non-vagus nerve stimulation; W, weeks; QOLIE-31, quality of life in epilepsy-31 inventory.

Indicates means ± SD. Non-parametric test (Mann–Whitney U test) was used. p < 0.05 was considered significant difference.

3.3 Changes in the EEG power spectrum in patients

Table 5 showed the EEG power spectrum (μV2) of two groups at 0 W and 24 W, and taVNS reduced the EEG power spectrum in the four frequency bands (p < 0.05). Supplementary Tables S1, S2 provide a detailed comparison within groups for the 16 electrode sites.

Table 5

| Band | Groups | Sum of 16 electronic sites | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medians ± IQR or means ± SDa | |||||

| 0 W | 24 W | Δ = 0 W–24 W | |||

| δ | taVNS | 274.25 ± 2.20 | 240.99 ± 1.32a | 33.20 ± 2.60 | <0.001 |

| tanVNS | 272.30 ± 3.68 | 258.39 ± 0.80a | 14.65 ± 3.23 | ||

| θ | taVNS | 310.20 ± 1.93 | 252.05 ± 123.92 | 57.95 ± 122.40 | 0.03 |

| tanVNS | 315.61 ± 0.89a | 284.10 ± 2.22 | 31.20 ± 1.37 | ||

| α | taVNS | 651.27 ± 1.52a | 478.08 ± 2.43a | 173.19 ± 2.80a | <0.001 |

| tanVNS | 645.81 ± 2.22a | 561.20 ± 2.98 | 84.56 ± 2.88a | ||

| β | taVNS | 867.20 ± 2.00 | 753.50 ± 1.27 | 113.80 ± 2.43 | <0.001 |

| tanVNS | 845.62 ± 1.28a | 774.09 ± 2.95a | 71.53 ± 3.58a | ||

Comparison of EEG spectral power (μV2) between taVNS group and tanVNS group.

EEG, electroencephalogram; taVNS, transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation; tanVNS, transcutaneous auricular non-vagus nerve stimulation; W, weeks.

Detailed power spectrum in four frequency bands at 16 electrode locations were in Supplementary Table S1, S2.

Indicates means ± SD. Δ δ, Δ θ and Δ β were not normally distributed so non-parametric test (Mann–Whitney U test) was used. Δ α were normally distributed with homogeneous variance, so independent-samples t-test was used. p < 0.05 was considered significant difference.

Longitudinal comparison before and after treatment (0 W vs. 24 W): In the patient taVNS group, after 24 weeks of taVNS treatment, there were significant differences in the full frequency band power at each electrode site (except for the O2δ segment in the occipital region) (p < 0.001, see Supplementary Table S1), and the power was decreased, suggesting that taVNS could help improve the brain power at the full frequency band of 16 electrode sites.

After 24 weeks of sham stimulation in the patient tanVNS group, except for the θ band at the FP2 position, the other frequency bands showed significant differences (p < 0.05, see Supplementary Table S2), which were also decreased, suggesting that tanVNS may show a certain placebo effect.

These results suggested that the EEG power spectrum did not change only after taVNS, but can also change under tanVNS. Further research is needed in the future to explore whether EEG power spectrum can be used as an indicator for predicting the efficacy of taVNS.

3.4 Adverse events

Only one patient showed ear rash at the beginning of the trial, so he withdrew from our study. None of the 40 patients who ultimately participated showed any side effects, and no adverse events were reported during the 24-week follow-up, indicating that the equipment was well tolerated.

4 Discussion

By examining data from patients’ epilepsy diaries and migraine diaries, we found that taVNS could reduce the frequency of seizures and migraine attacks in patients with comorbid epilepsy and migraine (see Table 2). Previous studies have confirmed that taVNS can reduce the frequency of seizures in patients with epilepsy or reduce the frequency of migraine attacks in patients with migraine (34, 36, 38, 44–46). Moreover, our study revealed that, according to SAS, SDS and QOLIE-31 scores, taVNS could improve the mood and quality of life of patients with comorbid epilepsy and migraine (see Tables 3, 4). Previous studies have confirmed that taVNS can improve mood and quality of life in patients with epilepsy or migraine (33, 38, 45, 46).

Regarding EEG outcomes, our study revealed that taVNS could reduce the EEG power spectrum of the four frequency bands (α, β, δ, and θ) throughout almost the entire brain during the interictal period in patients with comorbid epilepsy and migraine (see Table 5). Previous studies have shown that the power of θ and δ waves in epilepsy patients is increased (47–50). Additionally, in patients with benign childhood epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes, the absolute power of the θ, δ and α waves is increased (51, 52). Migraine patients have elevated absolute power in almost all frequency bands (53, 54), most significantly in high-frequency β waves (55, 56). In addition, migraine patients have increased θ relative power (57). These studies revealed an increase in the power of all bands of the EEG spectrum in patients with epilepsy or migraine, and our study revealed that taVNS could decrease the absolute power of these bands and alleviate clinical symptoms. Previous studies have shown that taVNS can decrease α activity (58) and β activity (59), which is consistent with our findings. On this basis, we speculate that taVNS leads to reduced seizures and migraine attacks by affecting neural pathways and brain region connectivity associated with frequency bands of the EEG power spectrum.

The mechanisms underlying the effects of taVNS on the EEG power spectrum, especially on different frequency bands, have not yet been fully studied. Activation of the NTS (60–62) and LC (63–68) via vagus nerve stimulation is one of the main mechanisms involved. Previous studies revealed that there are direct projections from the ABVN to the NTS in rats, and these projections are considered the anatomical basis of the auriculo-vagus relationship (21, 22). Other brain regions that are modulated include the limbic system, the reticular structure, and the autonomic nervous system in both cerebral hemispheres (64, 69). Through these brain regions, the power of different frequency bands can be modulated. taVNS can reduce the ability of α activity to suppress the interference effects of irrelevant information in prefrontal cortices (70–72), which presumably reduces abnormal discharges in patients with frontal lobe epilepsy. Increased β activity is significantly associated with epilepsy and migraine (73), and it is speculated that taVNS can reduce β activity by modulating cortico-thalamo-cortical (CTC) networks (74). taVNS can significantly modulate the activity/connectivity of brain regions associated with the central vagus nerve pathway and pain modulation system, including the DMN and brainstem areas (LC, raphe nuclei, parabrachial nucleus, and solitary nucleus) (75). Functional connectivity analysis revealed that taVNS can increase the connectivity between the motor-related thalamic subregion and anterior cingulate cortex/medial prefrontal cortex and decrease the connectivity between the occipital cortex-related thalamic subregion and the postcentral gyrus/precuneus (34). δ waves are essentially absent in the awake state under physiological conditions, and they are highly pronounced when subcortical brain damage occurs (76, 77). Our study revealed a decrease in δ activity in patients after taVNS, so we speculated that taVNS may regulate the thalamic-cortex circuit to attenuate harmful brain activity, such as seizures and migraine attacks, by decreasing δ activity. However, some studies have shown that taVNS increases δ activity and θ activity (78–80), which is inconsistent with our findings. Therefore, more studies are needed to explore the effects of taVNS on different frequency bands of the EEG power spectrum and the related mechanisms.

Pseudostimulation (tanVNS) could also decrease the EEG power spectrum (see Supplementary Table S2), but the decrease was less than that caused by taVNS (see Table 5). Although the stimulation of a very small number of ABVN peripheral branches by the pseudostimuli (38) may have slightly decreased the EEG power spectrum, the degree and range of stimulation were not enough to reduce the incidence of clinical seizures and migraine attacks in patients (see Table 2), which suggests that the selection of the ABVN stimulation site is very important for the clinical treatment effect (see Figure 2); specifically, the triangular fossa of the auricle should be chosen, as it has a more dense ABVN distribution (38).

4.1 Limitations

The sample size of this study was small so studies with larger sample sizes should be considered in the future. In our study, all patients with comorbid epilepsy and migraine received only monotherapy with the antiseizure medication VPA (25 patients used; 0.5 g bid) or LEV (15 patients used; 0.5 g bid). Owing to the small number of patients included, medication status could not be analysed as a covariate. We used only EEG power spectrum as an objective indicator of functional neuroimaging; therefore, in future studies, fMRI and EEG mathematical model analyses (such as the seizure detection model) could be used to further elucidate the mechanism underlying the effect of taVNS on brain networks. Our study included patients with epilepsy comorbid with migraine but did not include patients with only one of the disorders (epilepsy or migraine alone). The mechanism of epilepsy comorbid with migraine is complex (81), so comparisons of patients with only one of these diseases and both diseases are needed to identify the relationship between epilepsy and migraine. In addition, the relationship between clinical symptom relief and changes in the EEG power spectrum must be explored further.

5 Conclusion

The efficacy of taVNS in patients with epilepsy or migraine has been studied previously, but studies in patients with epilepsy comorbid with migraine are lacking. This study is the first of use taVNS in patients with comorbid epilepsy and migraine. As a noninvasive adjunctive therapy, taVNS can reduce the EEG power spectrum in patients with comorbid epilepsy and migraine. Patients’ epilepsy diaries and migraine diaries suggested that taVNS could reduce the frequency of seizures and migraine attacks. According to SAS, SDS, and QOLIE-31 scores, taVNS could improve the mood and quality of life of patients with comorbid epilepsy and migraine. In the future, further exploration of the mechanism underlying the effect of taVNS, such as changes in brain networks, would be useful to provide more treatment options for patients.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Clinical Trial Ethics Committee of Sichuan Provincial People’s Hospital (Number 430, 2023). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

SM: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JD: Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CL: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. XW: Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. LL: Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. TL: Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. XZ: Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. LY: Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JL: Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. YL: Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SZ: Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. RR-L: Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. QZ: Formal analysis, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This study was funded by National Key R&D Program of China (2024YFE0215100), Project of Science and Technology Department of Sichuan Province (2022NSFSC1439), the Natural Science Foundation of Sichuan Province (2023NSFSC1762), and the Youth Fund of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82304984).

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to all patients in this trial, and funding from the Project of Science and Technology Department of Sichuan Province (2022NSFSC1439), the Natural Science Foundation of Sichuan Province (2023NSFSC1762), and the Youth Fund of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82304984) is gratefully acknowledged.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fneur.2025.1694455/full#supplementary-material

References

1.

World Health Organization . Intersectoral global action plan on epilepsy and other neurological disorders 2022–2031. Geneva: World Health Organization (2023).

2.

Hesdorffer DC . Comorbidity between neurological illness and psychiatric disorders. CNS Spectr. (2016) 21:230–8. doi: 10.1017/S1092852915000929,

3.

Winawer MR Connors R EPGP Investigators . Evidence for a shared genetic susceptibility to migraine and epilepsy. Epilepsia. (2013) 54:288–95. doi: 10.1111/epi.12072,

4.

Pisanu C Preisig M Castelao E Glaus J Pistis G Squassina A et al . A genetic risk score is differentially associated with migraine with and without aura. Hum Genet. (2017) 136:999–1008. doi: 10.1007/s00439-017-1816-5,

5.

Sowell MK Youssef PE . The comorbidity of migraine and epilepsy in children and adolescents. Semin Pediatr Neurol. (2016) 23:83–91. doi: 10.1016/j.spen.2016.01.012,

6.

Liao J Tian X Wang H Xiao Z . Epilepsy and migraine—Are they comorbidity?Genes Dis. (2018) 5:112–8. doi: 10.1016/j.gendis.2018.04.007,

7.

Wang XQ Lang SY Zhang X Zhu F Wan M Shi XB et al . Comorbidity between headache and epilepsy in a Chinese epileptic center. Epilepsy Res. (2014) 108:535–41. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2013.12.013,

8.

Ottman R Lipton RB Ettinger AB Cramer JA Reed ML Morrison A et al . Comorbidities of epilepsy: results from the Epilepsy Comorbidities and Health (EPIC) survey. Epilepsia. (2011) 52:308–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2010.02927.x,

9.

Keezer MR Sisodiya SM Sander JW . Comorbidities of epilepsy: current concepts and future perspectives. Lancet Neurol. (2016) 15:106–15. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(15)00225-2,

10.

Kanner AM . Management of psychiatric and neurological comorbidities in epilepsy. Nat Rev Neurol. (2016) 12:106–16. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2015.243,

11.

Wilner AN Sharma BK Soucy A Thompson A Krueger A . Common comorbidities in women and men with epilepsy and the relationship between number of comorbidities and health plan paid costs in 2010. Epilepsy Behav. (2014) 32:15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2013.12.032,

12.

Velioğlu SK Boz C Ozmenoğlu M . The impact of migraine on epilepsy: a prospective prognosis study. Cephalalgia. (2005) 25:528–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2005.00912.x,

13.

Baca CB Vickrey BG Caplan R Vassar SD Berg AT . Psychiatric and medical comorbidity and quality of life outcomes in childhood-onset epilepsy. Pediatrics. (2011) 128:e1532–43. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-0245,

14.

Keezer MR Bauer PR Ferrari MD Sander JW . The comorbid relationship between migraine and epilepsy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Neurol. (2015) 22:1038–47. doi: 10.1111/ene.12612,

15.

Ben-Menachem E . Vagus-nerve stimulation for the treatment of epilepsy. Lancet Neurol. (2002) 1:477–82. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(02)00220-x,

16.

Magdaleno-Madrigal VM Martínez-Vargas D Valdés-Cruz A Almazán-Alvarado S Fernández-Mas R . Preemptive effect of nucleus of the solitary tract stimulation on amygdaloid kindling in freely moving cats. Epilepsia. (2010) 51:438–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2009.02337.x,

17.

Johnson RL Wilson CG . A review of vagus nerve stimulation as a therapeutic intervention. J Inflamm Res. (2018) 11:203–13. doi: 10.2147/JIR.S163248,

18.

Cohen-Gadol AA Britton JW Wetjen NM Marsh WR Meyer FB Raffel C . Neurostimulation therapy for epilepsy: current modalities and future directions. Mayo Clin Proc. (2003) 78:238–48. doi: 10.4065/78.2.238,

19.

He W Jing X Wang X Rong P Li L Shi H et al . Transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation as a complementary therapy for pediatric epilepsy: a pilot trial. Epilepsy Behav. (2013) 28:343–6. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2013.02.001,

20.

Stefan H Kreiselmeyer G Kerling F Kurzbuch K Rauch C Heers M et al . Transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation (t-VNS) in pharmacoresistant epilepsies: a proof of concept trial. Epilepsia. (2012) 53:e115–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2012.03492.x,

21.

Yang AC Zhang JG Rong PJ Liu HG Chen N Zhu B . A new choice for the treatment of epilepsy: electrical auricula-vagus-stimulation. Med Hypotheses. (2011) 77:244–5. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2011.04.021,

22.

He W Rong PJ Li L Ben H Zhu B Litscher G . Auricular acupuncture may suppress epileptic seizures via activating the parasympathetic nervous system: a hypothesis based on innovative methods. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. (2012) 2012:615476. doi: 10.1155/2012/615476,

23.

Kong J Fang J Park J Li S Rong P . Treating depression with transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation: state of the art and future perspectives. Front Psych. (2018) 9:20. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00020,

24.

Dietrich S Smith J Scherzinger C Hofmann-Preiss K Freitag T Eisenkolb A et al . A novel transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation leads to brainstem and cerebral activations measured by functional MRI. Biomed Tech. (2008) 53:104–11. doi: 10.1515/BMT.2008.022,

25.

Kraus T Hösl K Kiess O Schanze A Kornhuber J Forster C . BOLD fMRI deactivation of limbic and temporal brain structures and mood enhancing effect by transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation. J Neural Transm. (2007) 114:1485–93. doi: 10.1007/s00702-007-0755-z,

26.

Fox MD Raichle ME . Spontaneous fluctuations in brain activity observed with functional magnetic resonance imaging. Nat Rev Neurosci. (2007) 8:700–11. doi: 10.1038/nrn2201,

27.

Seeley WW Menon V Schatzberg AF Keller J Glover GH Kenna H et al . Dissociable intrinsic connectivity networks for salience processing and executive control. J Neurosci. (2007) 27:2349–56. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5587-06.2007,

28.

Greicius MD Krasnow B Reiss AL Menon V . Functional connectivity in the resting brain: a network analysis of the default mode hypothesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2003) 100:253–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0135058100,

29.

Singh TB Aisikaer A He C Wu Y Chen H Ni H et al . The assessment of brain functional changes in the temporal lobe epilepsy patient with cognitive impairment by resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging. J Clin Imaging Sci. (2020) 10:50. doi: 10.25259/JCIS_55_2020,

30.

Rao Y Liu W Zhu Y Lin Q Kuang C Huang H et al . Altered functional brain network patterns in patients with migraine without aura after transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation. Sci Rep. (2023) 13:9604. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-36437-1,

31.

Huang Y Zhang Y Hodges S Li H Yan Z Liu X et al . The modulation effects of repeated transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation on the functional connectivity of key brainstem regions along the vagus nerve pathway in migraine patients. Front Mol Neurosci. (2023) 16:1160006. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2023.1160006,

32.

Wang L Wang Y Wang Y Wang F Zhang J Li S et al . Transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulators: a review of past, present, and future devices. Expert Rev Med Devices. (2022) 19:43–61. doi: 10.1080/17434440.2022.2020095,

33.

Zhang Q Luo X Wang XH Li JY Qiu H Yang DD . Transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation for epilepsy. Seizure. (2024) 119:84–91. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2024.05.005,

34.

Zhang Y Huang Y Li H Yan Z Zhang Y Liu X et al . Transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation (taVNS) for migraine: an fMRI study. Reg Anesth Pain Med. (2021) 46:145–50. doi: 10.1136/rapm-2020-102088,

35.

Qin X Yuan Y Chen Y Liao J Lin S Yang Z et al . Application of scalp electroencephalogram in treatment of refractory epilepsy with vagus nerve stimulation. Sheng Wu Yi Xue Gong Cheng Xue Za Zhi. (2020) 37:699–707. doi: 10.7507/1001-5515.201909002,

36.

Rong P Liu A Zhang J Wang Y Yang A Li L et al . An alternative therapy for drug-resistant epilepsy: transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation. Chin Med J. (2014) 127:300–3. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0366-6999.20131511,

37.

Hong Z Jiang Y . Linchuang Zhenliao Zhinan Dianxianbing Fence (2023 Xiuding Ban). Beijing: People’s Medical Publishing House (2023).

38.

Rong P Liu A Zhang J Wang Y He W Yang A et al . Transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation for refractory epilepsy: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Sci Lond. (2014). doi: 10.1042/CS20130518

39.

Sacca V Zhang Y Cao J Li H Yan Z Ye Y et al . Evaluation of the modulation effects evoked by different transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation frequencies along the central vagus nerve pathway in migraine: a functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Neuromodulation. (2023) 26:620–8. doi: 10.1016/j.neurom.2022.08.459,

40.

Cao J Zhang Y Li H Yan Z Liu X Hou X et al . Different modulation effects of 1 Hz and 20 Hz transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation on the functional connectivity of the periaqueductal gray in patients with migraine. J Transl Med. (2021) 19:354. doi: 10.1186/s12967-021-03024-9,

41.

Egenasi CK Moodley AA Steinberg WJ Adefuye AO . Current norms and practices in using a seizure diary for managing epilepsy: a scoping review. S Afr Fam Pract. (2022) 64:e1–9. doi: 10.4102/safp.v64i1.5540,

42.

Duchaczek B Ghaeni L Matzen J Holtkamp M . Interictal and periictal headache in patients with epilepsy. Eur J Neurol. (2013) 20:1360–6. doi: 10.1111/ene.12049,

43.

Hu Y Guo Y Wang YQ Du Q Ding MP Da Z et al . Reliability and validity of a Chinese version of the Quality of Life in Epilepsy Inventory (QOLIE-31-P). Zhejiang Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. (2009) 38:605–10. doi: 10.3785/j.issn.1008-9292.2009.06.009

44.

Shiraishi H Egawa K Murakami K Nakajima M Ueda Y Nakakubo S et al . Transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation therapy in patients with cognitively preserved structural focal epilepsy: a case series report. Brain Dev. (2024) 46:49–56. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2023.08.007,

45.

Aihua L Lu S Liping L Xiuru W Hua L Yuping W . A controlled trial of transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation for the treatment of pharmacoresistant epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. (2014) 39:105–10. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2014.08.005,

46.

Luo W Zhang Y Yan Z Liu X Hou X Chen W et al . The instant effects of continuous transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation at acupoints on the functional connectivity of amygdala in migraine without Aura: a preliminary study. Neural Plast. (2020) 2020:1–13. doi: 10.1155/2020/8870589,

47.

Wu Y Gao M Cui Y Dong L Zhang J Chen M . Quantitative electroencephalography performance of different brain lobe epilepsy. Neuro Endocrinol Lett. (2023) 44:384–90.

48.

Walker JE . Power spectral frequency and coherence abnormalities in patients with intractable epilepsy and their usefulness in long-term remediation of seizures using neurofeedback. Clin EEG Neurosci. (2008) 39:203–5. doi: 10.1177/155005940803900410,

49.

Bonacci MC Sammarra I Caligiuri ME Sturniolo M Martino I Vizza P et al . Quantitative analysis of visually normal EEG reveals spectral power abnormalities in temporal lobe epilepsy. Neurophysiol Clin. (2024) 54:102951. doi: 10.1016/j.neucli.2024.102951,

50.

Fonseca E Quintana M Seijo-Raposo I Ortiz de Zárate Z Abraira L Santamarina E et al . Interictal brain activity changes in temporal lobe epilepsy: a quantitative electroencephalogram analysis. Acta Neurol Scand. (2022) 145:239–48. doi: 10.1111/ane.13543,

51.

Siripornpanich V Visudtibhan A Kotchabhakdi N Chutabhakdikul N . Delayed cortical maturation at the centrotemporal brain regions in patients with benign childhood epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes (BCECTS). Epilepsy Res. (2019) 154:124–31. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2019.05.003,

52.

Santiago-Rodríguez E Harmony T Cárdenas-Morales L Hernández A Fernández-Bouzas A . Analysis of background EEG activity in patients with juvenile myoclonic epilepsy. Seizure. (2008) 17:437–45. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2007.12.009,

53.

Vonderheid-Guth B Todorova A Wedekind W Dimpfel W . Evidence for neuronal dysfunction in migraine: concurrence between specific qEEG findings and clinical drug response—a retrospective analysis. Eur J Med Res. (2000) 5:473–83.

54.

Bjørk M Sand T . Quantitative EEG power and asymmetry increase 36 h before a migraine attack. Cephalalgia. (2008) 28:960–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2008.01638.x,

55.

Kim SJ Yang K Kim D . Quantitative electroencephalography as a potential biomarker in migraine. Brain Behav. (2023) 13:e3282. doi: 10.1002/brb3.3282,

56.

Walker JE . QEEG-guided neurofeedback for recurrent migraine headaches. Clin EEG Neurosci. (2011) 42:59–61. doi: 10.1177/155005941104200112,

57.

Ojha P Panda S . Resting-state quantitative EEG spectral patterns in migraine during ictal phase reveal deviant brain oscillations: potential role of density spectral Array. Clin EEG Neurosci. (2024) 55:362–70. doi: 10.1177/15500594221142951,

58.

Mridha Z de Gee JW Shi Y Alkashgari R Williams J Suminski A et al . Graded recruitment of pupil-linked neuromodulation by parametric stimulation of the vagus nerve. Nat Commun. (2021) 12:1539. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-21730-2,

59.

Song HY Shin DW Jung SM Jeong Y Jeong B Park CS . Feasibility study on transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation using millimeter waves. Biomed Phys Eng Express. (2021) 7:065028. doi: 10.1088/2057-1976/ac2c54,

60.

He W Jing XH Zhu B Zhu XL Li L Bai WZ et al . The auriculo-vagal afferent pathway and its role in seizure suppression in rats. BMC Neurosci. (2013) 14:85. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-14-85,

61.

Frangos E Ellrich J Komisaruk BR . Non-invasive access to the vagus nerve central projections via electrical stimulation of the external ear: fMRI evidence in humans. Brain Stimul. (2015) 8:624–36. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2014.11.018,

62.

Henry TR . Therapeutic mechanisms of vagus nerve stimulation. Neurology. (2002) 59:S3–S14. doi: 10.1212/wnl.59.6_suppl_4.s3,

63.

Krahl SE Clark KB Smith DC Browning RA . Locus coeruleus lesions suppress the seizure-attenuating effects of vagus nerve stimulation. Epilepsia. (1998) 39:709–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1998.tb01155.x,

64.

Raedt R Clinckers R Mollet L Vonck K El Tahry R Wyckhuys T et al . Increased hippocampal noradrenaline is a biomarker for efficacy of vagus nerve stimulation in a limbic seizure model. J Neurochem. (2011) 117:461–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07214.x,

65.

Dorr AE Debonnel G . Effect of vagus nerve stimulation on serotonergic and noradrenergic transmission. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. (2006) 318:890–8. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.104166,

66.

Manta S Dong J Debonnel G Blier P . Enhancement of the function of rat serotonin and norepinephrine neurons by sustained vagus nerve stimulation. J Psychiatry Neurosci. (2009) 34:272–80. doi: 10.1139/jpn.0936,

67.

Hulsey DR Riley JR Loerwald KW Rennaker RL 2nd Kilgard MP Hays SA . Parametric characterization of neural activity in the locus coeruleus in response to vagus nerve stimulation. Exp Neurol. (2017) 289:21–30. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2016.12.005,

68.

Berger A Beckers E Joris V Duchêne G Danthine V Delinte N et al . Locus coeruleus features are linked to vagus nerve stimulation response in drug-resistant epilepsy. Front Neurosci. (2024) 18:1296161. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2024.1296161,

69.

Fornai F Ruffoli R Giorgi FS Paparelli A . The role of locus coeruleus in the antiepileptic activity induced by vagus nerve stimulation. Eur J Neurosci. (2011) 33:2169–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2011.07707.x,

70.

Lu M Doñamayor N Münte TF Bahlmann J . Event-related potentials and neural oscillations dissociate levels of cognitive control. Behav Brain Res. (2017) 320:154–64. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2016.12.012,

71.

Palva S Palva JM . New vistas for alpha-frequency band oscillations. Trends Neurosci. (2007) 30:150–8. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2007.02.001,

72.

Miller EK Cohen JD . An integrative theory of prefrontal cortex function. Annu Rev Neurosci. (2001) 24:167–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.167,

73.

Glaba P Latka M Krause MJ Kuryło M Jernajczyk W Walas W et al . Changes in interictal pretreatment and posttreatment EEG in childhood absence epilepsy. Front Neurosci. (2020) 14:196. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2020.00196,

74.

Sorokin JM Paz JT Huguenard JR . Absence seizure susceptibility correlates with pre-ictal β oscillations. J Physiol Paris. (2016) 110:372–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jphysparis.2017.05.004,

75.

Zhang Y Liu J Li H Yan Z Liu X Cao J et al . Transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation at 1 Hz modulates locus coeruleus activity and resting state functional connectivity in patients with migraine: an fMRI study. Neuroimage Clin. (2019) 24:101971. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2019.101971,

76.

Zhu HH Rong PJ Chen Y Song XK Wang JY . Possible mechanisms of auricular acupoint stimulation in the treatment of migraine by activating auricular vagus nerve. Zhen Ci Yan Jiu. (2024) 49:403–8. doi: 10.13702/j.1000-0607.20221262

77.

Modarres MH Kuzma NN Kretzmer T Pack AI Lim MM . EEG slow waves in traumatic brain injury: convergent findings in mouse and man. Neurobiol Sleep Circadian Rhythms. (2016) 2:59–70. doi: 10.1016/j.nbscr.2016.06.001

78.

Marrosu F Santoni F Puligheddu M Barberini L Maleci A Ennas F et al . Increase in 20–50 Hz (gamma frequencies) power spectrum and synchronization after chronic vagal nerve stimulation. Clin Neurophysiol. (2005) 116:2026–36. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2005.06.015,

79.

Ricci L Croce P Lanzone J Boscarino M Zappasodi F Tombini M et al . Transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation modulates EEG microstates and delta activity in healthy subjects. Brain Sci. (2020) 10:668. doi: 10.3390/brainsci10100668,

80.

Keute M Boehrer L Ruhnau P Heinze HJ Zaehle T . Transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation (tVNS) and the dynamics of visual bistable perception. Front Neurosci. (2019) 13:227. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2019.00227,

81.

Zarcone D Corbetta S . Shared mechanisms of epilepsy, migraine and affective disorders. Neurol Sci. (2017) 38:73–6. doi: 10.1007/s10072-017-2902-0,

Summary

Keywords

transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation, epilepsy, migraine, comorbidity, EEG power spectrum

Citation

Ma S, Du J, Luo C, Wu X, Liu L, Liu T, Zhang X, Yang L, Liu J, Luo Y, Zhang S, Rodriguez-Labrada R and Zhu Q (2025) The effects of transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation in epilepsy comorbid with migraine on the EEG power spectrum: a randomized controlled trial. Front. Neurol. 16:1694455. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2025.1694455

Received

28 August 2025

Revised

13 October 2025

Accepted

05 November 2025

Published

12 December 2025

Volume

16 - 2025

Edited by

Jinming Han, Capital Medical University, China

Reviewed by

Wondyefraw Mekonen, Addis Ababa University, Ethiopia

Ming Shan, First Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University, China

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Ma, Du, Luo, Wu, Liu, Liu, Zhang, Yang, Liu, Luo, Zhang, Rodriguez-Labrada and Zhu.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Qiong Zhu, zhuqiong427@126.com

†These authors share first authorship

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.