Abstract

Introduction:

Alteplase is known to increase the risk of blood-brain barrier integrity disruption, potentiating hemorrhage and edema. Evolving edema reduces chances of good functional outcomes. There is a paucity of studies that investigate the role of alteplase administration in subacute edema progression. Here we aim to associate alteplase administration in combination with the degree of reperfusion on edema, measured by net water uptake.

Methods:

We included 115 patients from the MRCLEAN NO-IV trial with baseline, 24-h and 1-week follow-up non-contrast CT scans. The cohort consisted of patients who received intravenous thrombolysis (IVT)+ endovascular treatment (EVT) vs. EVT alone. Net water uptake (NWU) was calculated as a ratio of mean lesion density compared to its homologous, contralateral region-of-interest. Unadjusted linear regression analysis was performed to assess the association between NWU progression and alteplase administration, successful reperfusion [expanded Thrombolysis in Cerebral Infarction (eTICI)2B/3], and excellent reperfusion (eTICI2C/3). Adjusted regression analysis was performed to correct for potential confounders.

Results:

IVT administration was not statistically significantly associated with NWU progression. Regardless of treatment arm, there was substantial increase in NWU during the first 24 h and 1 week post-stroke. In adjusted analysis, successful reperfusion was significantly associated with reduced NWU progression at 24 h (β = −4.6; 95% CI: −8.4, −0.80) and 1 week (β = −6.5; 95% CI: −11, −2.3).

Conclusion:

Alteplase administration prior to EVT did not impact the subacute edema progression in our cohort, whereas successful reperfusion was strongly associated with reduced edema progression, particularly at later timepoints. These results suggest that alteplase administration according to current guidelines is unlikely to contribute to accelerated edema progression and emphasize that achieving high-grade reperfusion is crucial for reducing secondary injury.

Introduction

The added value of intravenous thrombolysis (IVT) with alteplase as an addition to endovascular treatment (EVT) has been questioned. Yet, results from recent studies indicate that administering IVT before EVT results in similar outcomes to EVT alone (1), but the evidence is not definitive. Pooled data analyses suggest that the benefit of IVT may be time-dependent, with greater effect when administered shortly after stroke onset (2). Kaesmacher et al. found that the benefit of IVT in addition to EVT decreased with increasing onset-to-treatment time and was statistically significant only if administered within 2 h and 20 min after onset. Nevertheless, uncertainty remains about the contribution of adding IVT on the increase of cerebral edema (3).

Cerebral edema may evolve even after successful treatment (4, 5), at least up to 1 week after stroke onset (4), and can range from mild swelling to severe, life-threatening forms. Known risk factors for the development of severe or malignant edema include younger age, higher National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) scores, and larger areas of parenchymal hypoattenuation on computed tomography (6). Malignant edema has also historically been suggested to occur more frequently in patients with cardioembolic stroke (7), although the evidence remains limited and inconclusive. Late lesion progression is associated with less favorable functional outcome (8). Post-treatment lesion progression could be attributed to secondary injury (such as cerebral edema) and/or the poor rates of microvascular reperfusion referred to as no-reflow phenomenon (9). However, Konduri et al. (5) reported that successful treatment is associated with reduced edema progression. Within the lesion, tissue density is altered due to water migration resulting from disruption of the osmotic gradient. Minnerup et al. developed a method of quantifying the change in the water content in the tissue, known as net water uptake (NWU) (10).

Alteplase, or rtPA, is a serine protease that triggers degradation of plasminogen to proteinase plasmin, which may dissolve the occluding thrombus and restore perfusion. While the clinical utility of this treatment is well-established, it is known from animal models that alteplase can affect integrity of the blood-brain barrier and induce hemorrhages (11). Beyond the risk of hemorrhagic complications, alteplase has been suggested to contribute to the development and progression of cerebral edema (12). Disruption of the blood-brain barrier leads to increased vascular permeability, extravasation of plasma proteins, and promoting vasogenic edema. Cerebral edema after stroke has been repeatedly associated with worse clinical outcomes (5, 13), and its progression could reflect ongoing injury, despite successful reperfusion. However, the effect of alteplase on cerebral edema progression in the subacute period remains unclear.

Understanding whether alteplase plays a role in edema progression may have implications for clinical management. While alteplase could potentially exacerbate edema formation and progression by disturbing the blood-brain barrier, it may also mitigate edema by promoting lysis of microthrombi and improving microvascular reperfusion (14). If alteplase exacerbates edema formation and progression, it could support the use of adjunctive therapies, such as osmotic agents, to mitigate secondary injury in selected patients. Although no neuroprotective therapies have yet proven effective, research in this area remains active, exploring a wide range of strategies (15).

Here, we investigated the effects of IVT with alteplase on edema progression during the subacute period (24 h and 1 week after stroke onset) using NWU measurements. Additionally, we performed a secondary analysis to examine whether edema progression varies with recanalization success, which is assessed with the eTICI score.

Methods

Study population

MRCLEAN NO-IV is a multicenter, randomized clinical trial that evaluated whether EVT alone is superior to combined IVT and EVT in acute ischemic stroke (AIS) patients with proximal intracranial LVO admitted directly to an EVT capable center (16, 17). Patients included in the study were over 18 years old, met criteria for receiving IVT with alteplase, and presented at a medical center that offered both treatments. Patients were randomized to receive either EVT alone or EVT preceded by IVT. We included patients with available NCCT at admission and 24 h and 1 week after treatment. Patients with NCCTs with excessive contrast extravasation, poor quality, movement artefacts, or other technical errors were excluded. Patients who underwent decompressive craniectomy were also excluded. Details can be found in Supplementary material (Section 2). Given that a substantial number of patients from the original trial were excluded due to imaging availability, we assessed the potential for selection bias by comparing baseline characteristics between included and excluded patients. This comparison is presented in the Supplementary material (Section 3).

Approval for the MRCLEAN NO-IV trial was obtained from the central medical ethics committee and the research boards of all participating centers. Written informed consent was provided by all patients or their legal representatives. Data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author and CONSTRAST consortium (https://www.contrast-consortium.nl/data-requests-consortium-members-and-trial-collaborators/) upon reasonable request.

Imaging assessment

A deep learning-based model based on a 3D nnUNet architecture was used to segment ischemic regions on baseline NCCT, with CTA images incorporated as additional input to inform the segmentation. The model was trained on annotated imaging data from the MRCLEAN Registry, MRCLEAN-MED, and MRCLEAN-LATE datasets, with MRCLEAN NO-IV cases excluded from training and validation to prevent bias (18).

The methodology to segment infarct lesions in follow-up NCCT scans (24-h and 1-week) has been described earlier (19). In summary, ischemic and hemorrhagic regions were segmented using a deep learning-based software developed by Nicolab (20). The segmented lesions were visually assessed and, if needed, manually corrected using ITK-SNAP software (21). Assessors were blinded for clinical data except for symptomatic side. The lesion delineations encompassed hypodensities that extended into the contralateral hemisphere or led to the deformation/compression of ventricles or sulci, as well as hyperdensities within/adjacent to the hypodense brain regions suspected as hemorrhage or calcifications. All segmentations were manually corrected by a trained neurologist (>5 years of experience) after consulting with an experienced neuro-radiologist (>15 years of experience) when necessary. Hemorrhages were outlined and excluded from the total lesion segmentation.

Non-hemorrhagic lesion volume (infarct and edema) where obtained by subtracting hemorrhagic regions from the total lesion segmentation. All other radiological and treatment parameters were assessed by the central blinded core-lab (16).

Net water uptake

NWU is calculated as the ratio of the mean density of the infarct lesion to that of its contralateral region-of-interest, considering only voxels with a density between 20 and 80 Hounsfield Units (HU) (22). To perform this calculation, the segmented ischemic lesion is mirrored onto the corresponding region in the contralateral (non-affected) hemisphere (Figure 1).

Figure 1

NWU processing pipeline. Follow-up scans were first registered to baseline. Baseline scans were subsequently aligned to an in-house atlas. The latter transformation matrices were applied to follow-up scans. Ischemic lesion segmentations were mirrored onto the contralateral hemisphere and a threshold of 20–80 HU was applied to define a reference region, and NWU was calculated as the ratio of mean lesion density to its contralateral counterpart.

To ensure that all images were aligned in a standardized space and allow for reliable mirroring of ischemic lesion segmentations, firstly, the follow-up scans (both 24-h and 1-week) were registered to their corresponding baseline scan, using affine transformation. Secondly, the baseline scans were registered to an in-house atlas to establish a common reference space. The transformation matrices acquired in this step were then applied to the previously aligned follow-up scans, ensuring all images for the individual subject occupied the same space.

Following registration and segmentations mirroring, the NWU is calculated as the ratio of the mean density of the ischemic lesion (Dischemic) in HU to the mean density of the contralateral, healthy tissue (Dpre − ischemic) as outlined in the formula below:

Higher NWU values indicate greater water uptake and more pronounced ischemic edema. Note that NWU is dimensionless and ranges between 0 and 100%.

Statistical analysis

In our study, NWU progression is the parameter of interest. However, using the change in a parameter (such as NWU increase) as a dependent variable can lead to biased results (23). For this reason, we created a model to estimate the follow-up NWU (NWUFU) with baseline NWU (NWUBL) as an independent parameter.

Where Bi are the parameters describing the strength of relation of NWUBL and IVT treatment (yes/no). This approach aimed to minimize bias related to baseline imbalance. Subsequently, we reformulated the model to express the progression ΔNWU, rather than absolute NWU value at follow-up.

The influence of IVT administration on NWU at 24-h (NWU24h) and 1-week (NWU1wk) post-stroke using univariable and multivariable linear regression after adjusting for age, sex, baseline NIHSS, baseline Alberta Stroke Programme Early CT Score (ASPECTS), reperfusion status (eTICI2B/3 or eTICI2C/3), and onset-to-randomization time.

Given that the reperfusion degree may influence edema progression, we conducted a secondary analysis to examine this relationship using univariable and multivariable linear regression models. We stratified patients based on their achieved reperfusion status. First, we categorized successful reperfusion as eTICI ≥ 2B. Subsequently, to assess the impact of excellent reperfusion, we repeated the analysis using a stricter threshold, considering successful reperfusion as eTICI2C/3.

Dichotomous and categorical baseline characteristics are presented as proportions. Continuous variables are presented as median and interquartile ranges. Mann–Whitney U-test and Chi-Square/Fisher-tests were performed to compare continuous and binary/categorical variables. Missing data was imputed using Multivariate Imputation by Chained Equations (MICE), implementing 20 imputations. The details of the MICE imputation are provided in Section 1 of the Supplementary material. Significance was assessed at a threshold of p < 0.05 and results were reported as adjusted estimates with corresponding 95% confidence intervals. Statistical analyses were performed using R (4.3.3[2024-02-29]).

Results

Of the 539 patients in the MRCLEAN NO-IV trial, 115 met the inclusion criteria (see Section 2 in Supplementary material). Median age was 71 (IQR: 59–76) years, 73 patients (63%) were male, and the median baseline NIHSS score was 16 (IQR: 11–19). Successful reperfusion (eTICI2B-3) was achieved in 96 patients (83%). Sixty-six patients (57%) achieved eTICI2C/3. Sixty-eight (59%) patients received IVT, and the median onset-to-randomization time was 92 (IQR: 70–140) minutes (Table 1).

Table 1

| Variable | Population (n = 115) | EVT alone (n = 47) | IVT and EVT (n = 68) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 71 (59–76) | 73 (65–80) | 67 (58–75) | 0.04 |

| Sex (male) | 73 (63%) | 30 (64%) | 43 (63%) | 1 |

| History of ischemic stroke | 13 (11%) | 7 (15%) | 6 (9%) | 0.48 |

| History of atrial fibrillation | 18 (16%) | 9 (19%) | 9 (13%) | 0.55 |

| History of diabetes mellitus | 21 (18%) | 10 (21%) | 11 (16%) | 0.65 |

| History of hypertension | 50 (43%) | 22 (47%) | 28 (41%) | 0.68 |

| Pre-stroke mRS > 2 | 3 (3%) | 2 (4%) | 1 (1%) | 0.74 |

| Baseline glucose (mmol/L) | 6.7 (5.9–8.1) | 6.8 (5.8–7.8) | 6.6 (5.9–8.8) | 0.56 |

| Baseline systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 150 (130–170) | 160 (130–170) | 150 (130–170) | 0.97 |

| Onset-to-randomization time (min) | 92 (70–140) | 98 (70–140) | 90 (70–140) | 0.90 |

| Door-to-groin time (min) | 69 (54–95) | 65 (52–90) | 70 (57–96) | 0.48 |

| Onset-to-groin time (min) | 140 (110–190) | 150 (110–180) | 140 (110–200) | 0.98 |

| Onset-to-reperfusion time (min) | 180 (160–230) | 190 (160–250) | 180 (160–220) | 0.76 |

| Right-sided stroke | 57 (50%) | 25 (53%) | 32 (47%) | 0.65 |

| Stroke subtype according to TOAST classification | ||||

| Cardioembolic | 32 (28%) | 18 (38%) | 14 (21%) | 0.19 |

| Large artery atherosclerosis | 19 (17%) | 8 (17%) | 11 (16%) | |

| Other determined | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1%) | |

| Undetermined etiology | 57 (50%) | 18 (38%) | 39 (57%) | |

| Undetermined etiology (more than one cause) | 6 (5%) | 3 (6%) | 3 (4%) | |

| Baseline NIHSS | 16 (11–19) | 16 (11–19) | 16 (9–19) | 0.76 |

| Baseline ASPECTS | 9 (8–10) | 9 (8–10) | 9 (8–10) | 0.92 |

| Proximal occlusion (MCA) | 95 (83%) | 38 (81%) | 57 (84%) | 0.87 |

| 24-h mAOL score = 3 | 92 (80%) | 36 (77%) | 56 (82%) | 0.60 |

| Baseline collateral score | ||||

| Score 0 (absent collaterals) | 6 (5%) | 2 (4%) | 4 (6%) | 0.50 |

| Score 1 (filling ≤ 50% occluded area) | 31 (27%) | 13 (28%) | 18 (26%) | |

| Score 2 (>50%; < 100%) | 51 (44%) | 24 (51%) | 27 (40%) | |

| Score 3 (100% occluded area) | 27 (23%) | 8 (17%) | 19 (28%) | |

| eTICI2B-3 | 96 (83%) | 42 (89%) | 54 (79%) | 0.25 |

| eTICI2C-3 | 66 (57%) | 28 (60%) | 38 (56%) | 0.84 |

| 90-day mRS ≤ 2 | 56 (49%) | 21 (45%) | 35 (51%) | 0.60 |

| 90-day mRS | ||||

| 0 | 3 (3%) | 1 (2%) | 2 (3%) | 0.11 |

| 1 | 10 (9%) | 5 (11%) | 5 (7%) | |

| 2 | 43 (37%) | 15 (32%) | 28 (41%) | |

| 3 | 11 (10%) | 7 (15%) | 4 (6%) | |

| 4 | 18 (16%) | 3 (6%) | 15 (22%) | |

| 5 | 15 (13%) | 7 (15%) | 8 (12%) | |

| 6 | 15 (13%) | 9 (19%) | 6 (9%) | |

| Baseline lesion volume (mL) | 14 (3.7–34) | 11 (2.5–26) | 15 (5.5–37) | 0.13 |

| Baseline edema (mL) | 0.5 (0.1–1.5) | 0.5 (0.1–1.4) | 0.6 (0.2–1.8) | 0.21 |

| Baseline NWU (%) | 4.3 (2.1–6.8) | 4 (1.8–6.7) | 4.5 (2.4–6.7) | 0.63 |

| Hemorrhagic transformation | 41 (36%) | 17 (36%) | 24 (35%) | 1 |

Baseline characteristics after multivariate imputation by chained equations (MICE).

Data displayed as median (interquartile ranges) or number (% of population). Mann-Whitney U-test and Chi-Square/Fisher tests were performed to compare continuous and binary/categorical variables between the sub-groups based on treatment allocation (EVT alone/EVT + VT).

Most baseline characteristics did not differ significantly between IVT + EVT vs. EVT alone patients. However, patients in the EVT+IVT group were younger than those in the EVT alone group (67 vs. 73 years; p = 0.04). There were no statistically significant differences in baseline NIHSS scores (median score of 16 in both groups; p = 0.76) or ASPECTS (median score of 9 in both groups; p = 0.92). Slightly more patients in the EVT alone group achieved successful reperfusion (89 vs. 79%; p = 0.25). There were no significant differences between groups in lesions characteristics: patients in the EVT alone group had smaller lesions [11 mL (IQR: 2.5–26) vs. 15 mL (IQR: 5.5–37); p = 0.13] and slightly lower NWU [4% (IQR: 1.8–6.7) vs. 4.5% (IQR: 2.4–6.7) in the EVT + IVT group; p = 0.67] at admission.

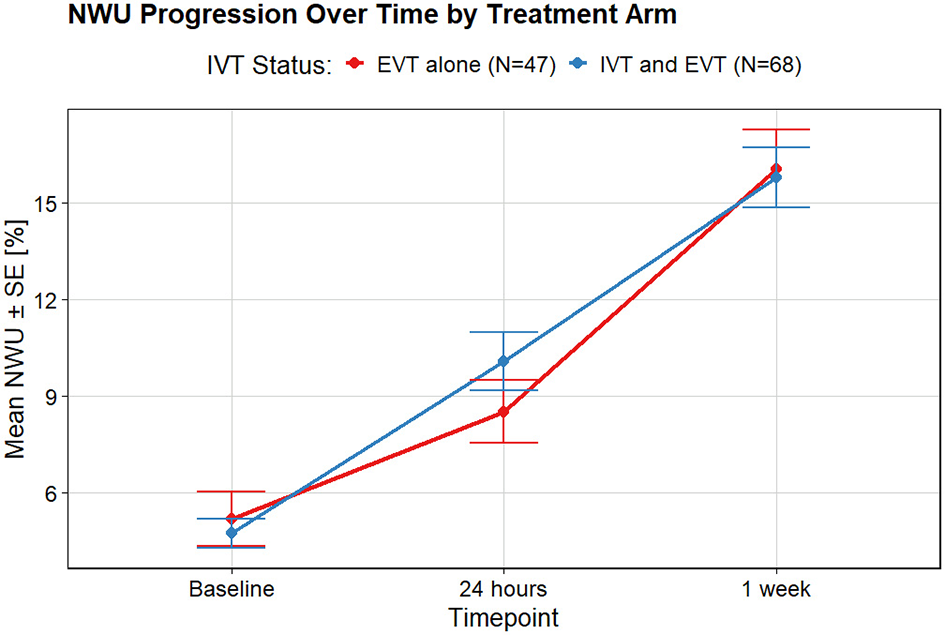

In both groups, median NWU increased substantially from baseline (EVT + IVT: 4.5%; EVT alone: 4%) to 24 h (EVT + IVT: 9.8%; EVT alone: 8.3%) and further to 1 week (EVT + IVT: 15%; EVT alone: 15%). NWU progression in the first 24 h was larger in the EVT + IVT group compared to EVT alone, but the difference was not statistically significant (Figure 2). For both the NWU progression during the first 24 h and 1 week NWU progression, the contribution of IVT administration was not statistically significant. In the multivariable models, IVT administration was also not significantly associated with NWU progression at either timepoint.

Figure 2

NWU progression over time for two treatment arms: EVT alone and IVT prior to EVT. In the first 24 h, edema extended more for patients who received IVT. This difference reduces within 1 week.

Successful reperfusion (eTICI2B/3) was statistically significantly associated with reduced NWU progression at both timepoints. However, this association between reperfusion status and NWU progression was no longer statically significant at 1 week follow-up if the threshold was set at eTICI2C/3 (Table 2; Figure 3).

Table 2

| Predictor variable | Δ NWU24h | Δ NWU1week |

|---|---|---|

| β (95%CI), p-value | β (95%CI), p-value | |

| Association of IVT administration with ΔNWU | ||

| IVT administration | 1.5 (−1.3, 4.2), p = 0.31 | −0.4 (−3.5, 2.8), p = 0.83 |

| Association of eTICI2B/3 with ΔNWU | ||

| eTICI2B/3 | –4.7 (– 8.3, –1.1), p=0.01 | –6.4 (–10.5, –2.4), p=0.002 |

| Association of eTICI2C/3 with ΔNWU | ||

| eTICI2C/3 | –2.9 (–5.6, –0.1), p=0.04 | −2.8 (−5.9, 0.4), p = 0.09 |

| Multivariable models | ||

| IVT administration | 1.3 (−1.4, 4.1), p = 0.34 | −0.7 (−3.9, 2.5), p = 0.66 |

| Age | 0.01 (−0.1, 0.1), p = 0.88 | 0.02 (−0.1, 0.2), p = 0.77 |

| Sex (male) | 1.9 (−1.0, 4.8), p = 0.19 | 0.6 (−2.7, 3.9), p = 0.73 |

| Baseline NIHSS | 0.1 (−0.1, 0.4), p = 0.24 | 0.1 (−0.2, 0.4), p = 0.48 |

| Baseline ASPECTS | 0.2 (−0.7, 1.1), p = 0.68 | −0.1 (−1.1, 1.0), p = 0.90 |

| eTICI2B/3 | –4.6 (–8.3, –1.0), p=0.01 | –6.6 (–10.8, –2.4), p=0.003 |

| Onset-to-randomization time | 0.02 (0.01, 0.04), p=0.01 | 0.02 (−0.00, 0.04), p = 0.06 |

Univariate and multivariable linear regression analysis for predicting NWU progression at 24-h and 1-week follow-up.

Data displayed as median (interquartile ranges) or number (% of population). Mann-Whitney U-test and Chi-Square/Fisher tests were performed to compare continuous and binary/categorical variables between the sub-groups based on treatment allocation (EVT alone/EVT + VT). Values in bold denote statistically significant associations (p < 0.05).

Figure 3

![Line graph showing NWU progression by reperfusion status over three time points: Baseline, 24 hours, and 1 week. Red line represents eTICI 2C/3 (No, N=43) and blue line represents eTICI 2C/3 (Yes, N=72). Both groups increase over time, with Yes group consistently lower than No. Error bars indicate standard error. Line graph titled “NWU Progression by Reperfusion Status (Near-Perfect Reperfusion)” comparing eTICI 2C/3 groups, with red for “No” (N=43) and blue for “Yes” (N=72). Y-axis indicates mean NWU ± SE [%] ranging from 5 to 20, and X-axis shows timepoints: Baseline, 24 hours, and 1 week. Both groups increase over time, with “Yes” group consistently lower than “No”. Error bars are present.](https://www.frontiersin.org/files/Articles/1698480/xml-images/fneur-16-1698480-g0003.webp)

Comparison of NWU progression stratified by reperfusion status. (A) NWU progression for successful reperfusion (eTICI ≥ 2B) vs. unsuccessful reperfusion, showing significantly less edema progression in the successfully reperfused group. (B) NWU progression in patients with near-complete reperfusion (eTICI ≥ 2C) compared to those with lower reperfusion scores.

In multivariable models, successful reperfusion (eTICI2B/3) was significantly associated with decreased NWU at both timepoints (Table 2). For the definition of reperfusion status as eTICI2C/3 (Table 3), this association was no longer significant for either timepoint.

Table 3

| Predictor variable | Δ NWU24h | Δ NWU1week |

|---|---|---|

| β (95%CI), p-value | β (95%CI), p-value | |

| Multivariable models | ||

| IVT administration | 1.7 (−1.1, 4.4), p = 0.24 | −0.2 (−3.5, 3.1), p = 0.90 |

| Age | 0.004 (−0.1, 0.1), p = 0.95 | 0.02 (−0.1, 0.2), p = 0.82 |

| Sex (male) | 1.4 (−1.5, 4.3), p = 0.34 | −0.1 (−3.5, 3.3), p = 0.95 |

| Baseline NIHSS | 0.1 (−0.1, 0.4), p = 0.34 | 0.1 (−0.2, 0.3), p = 0.66 |

| Baseline ASPECTS | 0.1 (−0.8, 1.0), p = 0.84 | −0.1 (−1.2, 0.9), p = 0.80 |

| eTICI2C/3 | −2.5 (−5.3, 0.3), p = 0.08 | −2.6 (−5.9, 0.7), p = 0.12 |

| Onset-to-randomization time | 0.02 (0.01, 0.04), p=0.01 | 0.02 (−0.001, 0.04), p = 0.06 |

Multivariable regression analysis stratified by eTICI2C/3.

Discussion

In this study, we showed that in EVT-treated patients, edema strongly increases at both 24-h and 1-week follow-up post-stroke, irrespective of alteplase administration. We also showed that successful reperfusion, defined as eTICI2B/3, is associated with reduced edema progression, also after adjusting for confounders. While in the univariate analysis (near-)perfect (eTICI2C/3) reperfusion was associated with reduced edema progression at 24-h follow-up, in the adjusted analysis we found no significant association at either imaging time.

Adverse effects of IVT have been described previously (3). Yet, there is little knowledge on the effect of IVT on subacute edema progression, quantified as NWU, in the subacute time window from stroke onset. Unlike methods dependent on global anatomical changes, NWU is well-suited for assessing edema extent even in small infarcts. Even though no statistically significant association between IVT and NWU progression had been observed, patients who received IVT alongside EVT, on average, showed greater edema progression within the first 24 h, though not significant. In their study, Frisullo et al. defined edema progression as the increase in total lesion volume over time. While this volumetric approach provides an estimate of tissue expansion, it may be influenced by factors such as infarct growth, making it challenging to isolate edema-specific changes. In contrast, our study utilized a densitometric approach, giving a direct indicator of tissue water content. This method allows for a more precise edema progression quantification by capturing changes in tissue composition.

In our cohort, we did not observe a significant difference in cerebral edema progression between patients who received alteplase and those who did not, suggesting that alteplase administration does not exacerbate or mitigate edema progression after AIS. While alteplase is well-established as an effective treatment, it is also known to carry risks such as intracerebral hemorrhage or angioedema (3), which must be weighed against its benefits. Particularly for patients who are eligible for EVT, evidence from randomized controlled trials regarding the benefit of administering alteplase prior to EVT remains inconclusive (16, 24–28), suggesting that in this population the potential risks may outweigh the limited added value. However, results of a meta-analysis by Kaesmacher et al. (2) suggested that the benefit of alteplase administration might be time dependent. In their study, the addition of IVT prior to EVT within 2 h and 20 min from stroke onset resulted in better functional outcomes. In light of these results, consideration should be given to the time from onset when planning treatment. For patients presenting later within the recommended time window, the risk-to-benefit ratio may be less favorable as the therapeutic effect of IVT prior to EVT decreases the longer the delay from onset.

Late lesion progression has been shown to be most extensive in patients who did not achieve full reperfusion (29), indicating that insufficient oxygen and nutrients supply drives a cascade of pathological biophysical and mechanistic pathways resulting in an increased water uptake in the ischemic tissue. In situations where distal emboli limit microvascular reperfusion, strategies such as local administration of alteplase or tenecteplase after EVT (PEARL, ANGEL-TNK) have been explored to improve microvascular flow and potentially reduce infarct and edema progression with promising but not yet definitive results (30, 31). Lesion progression could also be caused by an abnormal osmotic gradient across intra- and extra-cellular spaces leading to cytotoxicity. Moreover, abnormal osmotic gradients and disruptions to the blood-brain barrier can induce vasogenic edema (32). Our cohort consisted of patients that received treatment within 4.5 h from onset, further emphasizing that that early reperfusion prevents tissue damage and subsequently limits edema development. Conversely, in more severe cases with greater ischemic injury, reperfusion injury may be more common, potentially exacerbating edema formation despite vessel recanalization (5). Discussions on the relationship between reperfusion and edema frequently center around the concept of reperfusion injury (33). Reperfusion injury refers to tissue damage that occurs when blood flow is restored to previously ischemic brain regions, triggering pathological processes such as apoptosis, inflammation, oxidative stress, and blood-brain barrier disruption, which can promote edema development (34). It is important to note that 83% of patients included in this study achieved successful reperfusion, resulting in a substantial imbalance within both treatment groups.

The association between successful reperfusion and reduced cerebral edema formation has been previously described by Brooks et al. (35); however, their findings were based on retrospective observational data and were limited to a 24-h time window. In contrast, our study assessed edema progression up to 1-week post-stroke. We also performed a subanalysis on the effect of near-complete reperfusion (eTICI2C/3) on edema progression. In this secondary analysis, the association between reperfusion status and NWU progression was only significant at 24 h follow-up, and no longer significant at either timepoint after adjusting for confounders. Knowing that higher eTICI scores are associated with better functional outcomes, it is a somewhat unexpected observation. One possible explanation may lie in the skewed distribution of reperfusion grades in our cohort, with 83% achieving eTICI ≥ 2B and 57% achieving ≥ 2C, which could limit statistical power of the analysis and reduce observed contrasts. Another possible explanation is that partial reperfusion preserves vessel wall integrity to a degree sufficient to limit edema progression. Further improvement from partial to near-complete reperfusion may contribute little additional effect on edema, although higher eTICI scores are still associated with better functional outcomes (36). Moreover, procedural factors such as the number of passes, thrombus location, or device choice could play a critical role in infarct progression and edema formation process. Since our analysis did not account for these intervention-related variables, the interpretability of these findings remains limited. Nevertheless, it is now known that achieving higher reperfusion status is positively associated with functional outcomes, and thus, should be sought after (36).

Our study has a few limitations. Firstly, the patient cohort included in this study was relatively small, which may have resulted in low statistical power. As a result, the potentially meaningful associations between IVT administration and edema progression could remain undetected. Limited power also reduces the precision of effect estimates, making it more difficult to draw definitive conclusions. Future pooled analyses including data from other randomized clinical trials investigating the effect of IVT in patients that can directly undergo EVT (IRIS collaboration) could provide more precise answers (1). Importantly, our analyses focus on imaging markers of edema progression, which primarily reflect biological processes. We intentionally did not address the relation of these imaging markers with functional outcome in the current study. Therefore, our findings should be interpreted in the context of edema biology rather than clinical recovery. Nonetheless, the prognostic value of NWU change remains an important topic of investigation. A subsequent study from our group, specifically modeling the association between NWU change and 90-day functional outcome is currently being finalized. Secondly, this study did not account for thrombectomy-related variables, such as the number of passes or device selection. These factors could influence endothelial damage and subsequent edema formation but were not included in our analysis. As a result, the impact of intervention-related variables on edema progression remains uncertain, and further research incorporating these aspects may provide a more comprehensive understanding of the relationship between reperfusion and edema. Future studies should also evaluate edema progression in patients of advanced age (≥85 years), as demographics, risk factors, and outcomes have been shown to differ in this age group (37). Thirdly, assessment of ischemic lesions on NCCT is not straight-forward, especially at baseline and 24-h follow-up, since the hypo-dense areas might not be clearly defined in this early time window. Moreover, in contrast to follow-up scans, lesion delineations at baseline were segmented using an automated method, and the accuracy of these segmentation was not manually assessed by a clinician. This could introduce segmentation errors, particularly given that infarcts on baseline NCCT are often subtle and challenging to delineate due to low contrast and indistinct lesion boundaries. Future studies should incorporate expert validation of automated segmentations to enhance accuracy and reliability. Lastly, our approach to quantifying NWU differs slightly from previous studies. In the original method, Minnerup et al. excluded all patients with hemorrhagic transformation (10). In contrast, we included patients with identified hemorrhagic transformation but removed hemorrhagic regions from the lesion segmentations. While this approach prevents inclusion of non-edematous tissue, it may lead to an NWU underestimation, as hemorrhages often occur in areas of severe blood-brain barrier disruption where water accumulation is also expected (38). Additionally, in cases of large hematomas (such as parenchymal hematoma type 2), surrounding edema may be compressed by the hemorrhage, reducing the apparent hypodense volume on CT and further contributing to a potential underestimation of NWU. However, including hemorrhagic regions in NWU calculations is not feasible, as the presence of blood alters tissue density in a way that does not accurately reflect water content, potentially confounding the measurement.

Conclusion

In this study, a substantial increase in subacute cerebral edema was observed in all patients, regardless of treatment assignment. Alteplase administration prior to EVT did not influence this progression, whereas the degree of reperfusion remained an important determinant of edema dynamics. This suggests that the use of alteplase in accordance with current guidelines is unlikely to exacerbate cerebral edema and should not be withheld on this basis.

Statements

Data availability statement

The data analyzed in this study can be made available upon reasonable request to the CONSTRAST consortium. Requests to access these datasets should be directed to https://www.contrast-consortium.nl/data-requests-consortium-members-andtrial-collaborators/.

Ethics statement

The MRCLEAN NO-IV protocol was approved in the Netherlands by the central medical ethics committee and research board of the Erasmus MC University Medical Center, Rotterdam, the Netherlands (MEC-2017-368) before start of the trial. In France, the study was approved by the Comité de Protection des Personnes, Ile de France IV (ID-RCB: 2018-A00764-51). In Belgium, the study was approved by the Central Ethics Committee Research UZ/KU Leuven, Belgian Registration Number: B322201939935, as well as the Comité d'Ethique Medicale, CHC, Liège, Belgium (study number: 19/20/987). The study was conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (7th revision, October 2013), ICH-GCP, the Dutch Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act (WMO) and when applicable in accordance with regulations of other countries with participating centers. The trial protocol, including protocol version and amendments, can be found on the website https://www.mrclean-noiv.nl. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

WO: Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Writing – original draft. FC: Methodology, Writing – original draft, Conceptualization, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. LP: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Data curation. LB: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Data curation. BE: Data curation, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. IW: Writing – original draft, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. RL: Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Data curation, Writing – original draft. YR: Funding acquisition, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Data curation. HM: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Funding acquisition. PK: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Data curation, Methodology. CM: Conceptualization, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) received financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. W. Olszewski is funded by GEMINI (www.dth-gemini.eu): the European Union's Horizon Europe research and innovation programme (grant number 101136438); B. J. Emmer: Grants by Dutch Science foundation on behalf of Healthcare evaluation, Health Holland Topsector Lifesciences and Nico.lab, all paid to institution; P. Konduri received funds from European Union's Horizon research and innovation program (Grant Agreement Number: 101136438) and is currently funded by NIH/NINDS (grant number R01NS075209); C. Majoie reports grants from European Union (related and paid to institution) and CVON/Dutch Heart Foundation, Stryker, Boehringer-Ingelheim, TWIN Foundation, and Healthcare Evaluation Netherlands (outside the submitted work and paid to institution); MR CLEAN-NO IV trial was funded through the CONTRAST consortium, which acknowledges the support from the Netherlands Cardiovascular Research Initiative, an initiative of the Dutch Heart Foundation (CVON2015-01: CONTRAST), and from the Brain Foundation Netherlands (HA2015.01.06). The collaboration project is additionally financed by the Ministry of Economic Affairs by means of the PPP Allowance made available by the Top Sector Life Sciences & Health to stimulate public-private partnerships (LSHM17016). In addition, CONTRAST consortium is funded in part through unrestricted funding by Stryker, Medtronic and Penumbra. The funding sources were not involved in study design, monitoring, data collection, statistical analyses, interpretation of results, or manuscript writing.

Conflict of interest

PK is a cofounder and shareholder of inSteps BV; H. Marquering is cofounder and shareholder of Nico.lab, Trianect, and inSteps BV; CM is a shareholder of Nico.lab. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fneur.2025.1698480/full#supplementary-material

Abbreviations

AIS, Acute Ischaemic Stroke; ASPECTS, Alberta Stroke Programme Early CT Score; eTICI, Expanded Treatment in Cerebral Infarction; EVT, Endovascular Treatment; HU, Hounsfield Unit; IVT, Intravenous Thrombolysis; mAOL, Modified Arterial Occlusive Lesion; MCA, Middle Cerebral Artery; MICE, Multivariate Imputation by Chained Equations; mRS, Modified Rankin Scale; NIHSS, National Institute of Health Stroke Scale; NWU, Net Water Uptake.

References

1.

Majoie CB Cavalcante F Gralla J Yang P Kaesmacher J Treurniet KM et al . Value of intravenous thrombolysis in endovascular treatment for large-vessel anterior circulation stroke: individual participant data meta-analysis of six randomised trials. Lancet. (2023) 402:965–74.

2.

Kaesmacher J Cavalcante F Kappelhof M Treurniet KM Rinkel L Liu J et al . Time to treatment with intravenous thrombolysis before thrombectomy and functional outcomes in acute ischemic stroke: a meta-analysis. JAMA. (2024) 331:764–77. doi: 10.1001/jama.2024.7979

3.

Balami JS Sutherland BA Buchan AM . Complications associated with recombinant tissue plasminogen activator therapy for acute ischaemic stroke. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. (2013) 12:155–69. doi: 10.2174/18715273112119990050

4.

Konduri P Cavalcante F van Voorst H Rinkel L Kappelhof M van Kranendonk K et al . Role of intravenous alteplase on late lesion growth and clinical outcome after stroke treatment. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. (2023) 43(2_suppl):116–25. doi: 10.1177/0271678X231167755

5.

Konduri P Kranendonk VK Boers A Treurniet K Berkhemer O Yoo JA et al . The role of edema in subacute lesion progression after treatment of acute ischemic stroke. Front Neurol. (2021) 12:705221. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2021.705221

6.

Wu S Yuan R Wang Y Wei C Zhang S Yang X et al . Early prediction of malignant brain edema after ischemic stroke. Stroke. (2018) 49:2918–27. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.118.022001

7.

Robertson SC Lennarson P Hasan DM Traynelis VC . Clinical course and surgical management of massive cerebral infarction. Neurosurgery. (2004) 55:55–61; discussion−2. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000126875.02630.36

8.

Konduri P van Voorst H Bucker A van Kranendonk K Boers A Treurniet K et al . Posttreatment ischemic lesion evolution is associated with reduced favorable functional outcome in patients with stroke. Stroke. (2021) 52:3523–31. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.032331

9.

Mujanovic A Ng F Meinel TR Dobrocky T Piechowiak EI Kurmann CC et al . No-reflow phenomenon in stroke patients: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis of clinical data. Int J Stroke. (2024) 19:58–67. doi: 10.1177/17474930231180434

10.

Minnerup J Broocks G Kalkoffen J Langner S Knauth M Psychogios MN et al . Computed tomography-based quantification of lesion water uptake identifies patients within 45 hours of stroke onset: A Multicenter observational study. Ann Neurol. (2016) 80:924–34. doi: 10.1002/ana.24818

11.

Dong MX Hu QC Shen P Pan JX Wei YD Liu YY et al . Recombinant tissue plasminogen activator induces neurological side effects independent on thrombolysis in mechanical animal models of focal cerebral infarction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. (2016) 11:e0158848. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0158848

12.

Simao F Ustunkaya T Clermont AC Feener EP . Plasma kallikrein mediates brain hemorrhage and edema caused by tissue plasminogen activator therapy in mice after stroke. Blood. (2017) 129:2280–90. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-09-740670

13.

Strbian D Meretoja A Putaala J Kaste M Tatlisumak T Helsinki Stroke Thrombolysis Registry Group . Cerebral edema in acute ischemic stroke patients treated with intravenous thrombolysis. Int J Stroke. (2013) 8:529–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-4949.2012.00781.x

14.

Desilles JP Loyau S Syvannarath V Gonzalez-Valcarcel J Cantier M Louedec L et al . Alteplase reduces downstream microvascular thrombosis and improves the benefit of large artery recanalization in stroke. Stroke. (2015) 46:3241–8. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.010721

15.

Dammavalam V Lin S Nessa S Daksla N Stefanowski K Costa A et al . Neuroprotection during thrombectomy for acute ischemic stroke: a review of future therapies. Int J Mol Sci. (2024) 25:891. doi: 10.3390/ijms25020891

16.

Lecouffe EN Kappelhof M Treurniet MK Rinkel AL Bruggeman EA Berkhemer AO et al . A randomized trial of intravenous alteplase before endovascular treatment for stroke. N Engl J Med. (2021) 385:1833–44. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2107727

17.

Treurniet KM LeCouffe NE Kappelhof M Emmer BJ van Es A Boiten J et al . MR CLEAN-NO IV: intravenous treatment followed by endovascular treatment versus direct endovascular treatment for acute ischemic stroke caused by a proximal intracranial occlusion-study protocol for a randomized clinical trial. Trials. (2021) 22:141. doi: 10.1186/s13063-021-05063-5

18.

van Poppel F Treurniet KM Kappelhof M Lingsma HF Majoie CB . The effect of automatically extracted lesion water uptake on the safety and efficacy of intravenous thrombolysis before endovascular treatment. J Neurointerv Surg. (2023) 15:e414–8. doi: 10.1136/jnis-2022-019537

19.

Bucker A Boers AM Bot JCJ Berkhemer OA Lingsma HF Yoo AJ et al . Associations of ischemic lesion volume with functional outcome in patients with acute ischemic stroke: 24-hour versus 1-week imaging. Stroke. (2017) 48:1233–40. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.015156

20.

Sales Barros R Tolhuisen ML Boers AM Jansen I Ponomareva E Dippel DWJ et al . Automatic segmentation of cerebral infarcts in follow-up computed tomography images with convolutional neural networks. J Neurointerv Surg. (2020) 12:848–52. doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2019-015471

21.

Yushkevich PA Piven J Hazlett HC Smith RG Ho S Gee JC et al . User-guided 3D active contour segmentation of anatomical structures: significantly improved efficiency and reliability. Neuroimage. (2006) 31:1116–28. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.01.015

22.

Ng FC Yassi N Sharma G Brown SB Goyal M Majoie C et al . Correlation between computed tomography-based tissue net water uptake and volumetric measures of cerebral edema after reperfusion therapy. Stroke. (2022) 53:2628–36. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.121.037073

23.

Mistry EA Yeatts SD Khatri P Mistry AM Detry M Viele K et al . National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale as an outcome in stroke research: value of ANCOVA over analyzing change from baseline. Stroke. (2022) 53:e150–e5. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.121.034859

24.

Yang P Zhang Y Zhang L Zhang Y Treurniet KM Chen W et al . Endovascular thrombectomy with or without intravenous alteplase in acute stroke. N Engl J Med. (2020) 382:1981–93.

25.

Fischer U Kaesmacher J Strbian D Eker O Cognard C Plattner PS et al . Thrombectomy alone versus intravenous alteplase plus thrombectomy in patients with stroke: an open-label, blinded-outcome, randomised non-inferiority trial. Lancet. (2022) 400:104–15.

26.

Zi W Qiu Z Li F Sang H Wu D Luo W et al . Effect of endovascular treatment alone vs intravenous alteplase plus endovascular treatment on functional independence in patients with acute ischemic stroke: the DEVT randomized clinical trial. JAMA. (2021) 325:234–43. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.23523

27.

Suzuki K Matsumaru Y Takeuchi M Morimoto M Kanazawa R Takayama Y et al . Effect of mechanical thrombectomy without vs with intravenous thrombolysis on functional outcome among patients with acute ischemic stroke: the SKIP randomized clinical trial. JAMA. (2021) 325:244–53. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.23522

28.

Mitchell PJ Yan B Churilov L Dowling RJ Bush SJ Bivard A . et al. Endovascular thrombectomy versus standard bridging thrombolytic with endovascular thrombectomy within 45 h of stroke onset: an open-label, blinded-endpoint, randomised non-inferiority trial. Lancet. (2022) 400:116–25. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00564-5

29.

Federau C Mlynash M Christensen S Zaharchuk G Cha B Lansberg MG et al . Evolution of volume and signal intensity on fluid-attenuated inversion recovery MR images after endovascular stroke therapy. Radiology. (2016) 280:184–92. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2015151586

30.

Miao Z Luo G Song L Sun D Chen W Yao X et al . Intra-arterial tenecteplase for acute stroke after successful endovascular therapy: the ANGEL-TNK randomized clinical trial. JAMA. (2025) 334:582–91. doi: 10.1001/jama.2025.10800

31.

Yang X He X Pan D Xu Y Peng H Li K et al . Intra-arterial alteplase for acute ischaemic stroke after mechanical thrombectomy (PEARL): rationale and design of a multicentre, prospective, open-label, blinded-endpoint, randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. (2024) 14:e091059. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2024-091059

32.

Teng F Beray-Berthat V Coqueran B Lesbats C Kuntz M Palmier B et al . Prevention of rt-PA induced blood-brain barrier component degradation by the poly(ADP-ribose)polymerase inhibitor PJ34 after ischemic stroke in mice. Exp Neurol. (2013) 248:416–28. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2013.07.007

33.

Krishnan R Mays W Elijovich L . Complications of mechanical thrombectomy in acute ischemic stroke. Neurology. (2021) 97(20 Suppl 2):S115–25. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000012803

34.

Zhang M Liu Q Meng H Duan H Liu X Wu J et al . Ischemia-reperfusion injury: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic targets. Signal Transduct Target Ther. (2024) 9:12. doi: 10.1038/s41392-023-01688-x

35.

Broocks G Flottmann F Hanning U Schon G Sporns P Minnerup J et al . Impact of endovascular recanalization on quantitative lesion water uptake in ischemic anterior circulation strokes. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. (2020) 40:437–45. doi: 10.1177/0271678X18823601

36.

Cimflova P Ospel JM Singh N Marko M Kashani N Mayank A et al . Effects of reperfusion grade and reperfusion strategy on the clinical outcome: insights from ESCAPE-NA1 trial. Interv Neuroradiol. (2024) 30:804–11. doi: 10.1177/15910199241288874

37.

Torres-Riera S Arboix A Parra O Garcia-Eroles L Sanchez-Lopez MJ . Predictive clinical factors of in-hospital mortality in women aged 85 years or more with acute ischemic stroke. Cerebrovasc Dis. (2025) 54:11–9. doi: 10.1159/000536436

38.

Simard JM Kent TA Chen M Tarasov KV Gerzanich V . Brain oedema in focal ischaemia: molecular pathophysiology and theoretical implications. Lancet Neurol. (2007) 6:258–68. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70055-8

Summary

Keywords

cerebral edema, progression, ischemic lesion, net water uptake, subacute, acute ischemic stroke

Citation

Olszewski W, Cavalcante F, van Poppel L, Beenen L, Emmer BJ, van den Wijngaard I, Lemmens R, Roos Y, Marquering H, Konduri P and Majoie C (2025) Subacute edema progression after acute ischemic stroke: impact of intravenous alteplase administration and reperfusion degree. Front. Neurol. 16:1698480. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2025.1698480

Received

03 September 2025

Accepted

17 October 2025

Published

25 November 2025

Volume

16 - 2025

Edited by

Zilong Zhao, Tianjin Medical University General Hospital, China

Reviewed by

Antonio Ciacciarelli, Sapienza University of Rome, Italy

Adria Arboix, Sacred Heart University Hospital, Spain

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Olszewski, Cavalcante, van Poppel, Beenen, Emmer, van den Wijngaard, Lemmens, Roos, Marquering, Konduri and Majoie.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Wiktor Olszewski, w.olszewski@amsterdamumc.nl

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.