- Department of Industrial/Organizational and Social Psychology, Institute of Psychology, Technische Universität Braunschweig, Braunschweig, Germany

Introduction: In knowledge-based work environments, workplace learning is essential for successful employee integration and long-term performance. Onboarding represents a crucial phase in which newcomers begin to acquire organizational knowledge, take on new tasks, and establish social connections. While existing research has highlighted the role of formal and informal learning formats, less is known about how different learning forms interact and how newcomers actively contribute to their onboarding by engaging in self-regulated learning behaviors.

Methods: This qualitative study investigates onboarding as a dynamic learning process, focusing on how newcomers engage in formal, informal, and self-regulated workplace learning behaviors across four content dimensions: compliance, clarification, connection, and culture. The study is based on 40 semi-structured interviews with newcomers and analyzed using qualitative content analysis.

Results: The findings show that newcomers engage in diverse learning activities that vary in structure and learner involvement. These differences illustrate distinct patterns in observed workplace learning behaviors across the four content dimensions.

Discussion: The study contributes to onboarding and workplace learning theory by linking content dimensions to learning forms and highlighting how newcomers actively shape their onboarding experience. It challenges static models of onboarding and conceptualizes it instead as an individualized and interactive learning path shaped by both organizational structures and learner behavior. Practical implications include designing onboarding processes that combine structure with learner autonomy and recognize newcomers not only as recipients of information, but as active participants who can co-construct organizational learning through their engagement.

1 Introduction and theoretical background

In today's dynamic and knowledge-based work environment, continuous learning and organizational knowledge are becoming increasingly important (Jeong et al., 2018; Khan et al., 2025). Society is evolving into a knowledge-based society, where workplace learning is gaining increased priority in the workplace (Decius et al., 2023; Schaper et al., 2023). At the same time, the labor market is shaped by trends such as a shortage of skilled workers and increased job mobility (Decius et al., 2021). These developments underscore the growing importance of effective onboarding processes, which can reduce early turnover, strengthen employee retention, and improve performance (Bauer et al., 2025; Frögéli et al., 2023; Moser et al., 2018).

In general, the onboarding process, defined as “formal and informal practices, programs, and policies enacted or engaged in by an organization or its agents to facilitate newcomer adjustment” (Klein and Polin, 2012, p. 268), aims to integrate new employees, provide the necessary information, and support their engagement in job-related learning processes (Bauer et al., 2021). During onboarding, newcomers become part of teams, take on new responsibilities (Adler and Castro, 2019) and are introduced to organizational practices, processes, and values (Klein and Polin, 2012). One primary goal of onboarding is to reduce newcomers' uncertainty, provide information, and create opportunities for meaningful learning (Ellis et al., 2015). To support this, organizations offer various measures such as training sessions, mentoring, Q&A-sessions, and company tours during onboarding (Klein et al., 2015; Mitschelen et al., 2025). Organizational onboarding can be defined through four dimensions that highlight areas where learning is required: Compliance (administrative), Clarification (professional), Connection (social), and Culture (cultural; Bauer and Erdogan, 2011; Gerhardt et al., 2022). The compliance dimension refers to understanding regulations and legal requirements; clarification is about professional adjustment and clarifying the new role. The connection dimension addresses the building of relationships and getting to know responsibilities, while the cultural dimension includes formal and informal rituals and values. These dimensions represent key areas newcomers must engage in workplace learning to acquire relevant knowledge during onboarding (Bauer and Erdogan, 2011; Gerhardt et al., 2022). Onboarding is thus increasingly not only seen as an administrative or social integration process, but as a critical phase of workplace learning (Becker and Bish, 2021; Jeske and Olson, 2022; Klein et al., 2015), perhaps the most critical (Miller and Jablin, 1991). During this phase, newcomers must develop a comprehensive understanding of job responsibilities, work procedures, and organizational politics (Fang et al., 2011; Kowtha, 2018).

Recent research differentiates three forms of work-related learning that occur in different contexts: formal workplace learning (FWL), informal workplace learning (IWL), and self-regulated workplace learning (SRWL) (Decius, 2024; Kortsch et al., 2024). FWL is typically structured, deliberately planned, and institutionally supported (Kortsch et al., 2024; Tannenbaum and Wolfson, 2022). It includes formats such as classroom-based training sessions, workplace education programs, or written instructions (Decius et al., 2019; Jeong et al., 2018). IWL, by contrast, emerges organically within everyday work activities and is often triggered by specific problems or challenges (Cerasoli et al., 2018; Decius, 2024; Decius et al., 2024b). It is minimally structured and allows learners autonomy in their learning process (Decius et al., 2023; Tannenbaum and Wolfson, 2022). The Octagon Model of IWL (Decius et al., 2019) identifies facets such as experimentation, learning through modeling, mentoring, and receiving feedback as typical learning activities. IWL can further be differentiated into self-based and social-based forms (Decius and Hein, 2024). Self-based IWL includes activities like reflecting on one's actions or experimenting with new approaches, while social-based IWL encompasses learning through feedback, observations, or informal conversations with others (Decius and Hein, 2024). Lastly, SRWL represents an intentional, goal-directed learning process characterized by specific behaviors such as goal setting, planning, and self-monitoring (Decius et al., 2019; Richter et al., 2020; Sitzmann and Ely, 2011). We adopt the term SRWL to highlight the contextual focus on learning processes within organizational settings, building on the broader concept of self-regulated learning (SRL) established in educational psychology (e.g., Sitzmann and Ely, 2011). In this process, learner actively set specific learning goals, monitoring their progress (Jin et al., 2023) and regulate their learning strategies (Sitzmann and Ely, 2011; Panadero, 2017).

While these learning forms are analytically distinct, they often overlap in practice and provide complementary settings for learners to engage in various learning behaviors (Cerasoli et al., 2018; Rohs, 2009). Prior research highlights the fluid boundaries between formal and informal learning, noting that they often intertwine and share overlapping content, making rigid categorizations problematic (Kauffeld et al., 2025; Manuti et al., 2015; Paulsen et al., 2024). For instance, SRWL could emerge within both formal and informal settings—depending on the learner's engagement in SRWL behaviors such as autonomy, goal-setting, and reflection (Decius et al., 2023; Paulsen et al., 2024; Richter et al., 2020). A formal training session may arouse SRWL when newcomers monitor their understanding or seek additional input, while informal exchanges may not lead to learning unless learners actively engage with them (Richter et al., 2020). Accordingly, we do not treat FWL, IWL, and SRWL as fixed types but as conceptual lenses to examine the diverse and dynamic learning processes during onboarding (Marsick and Watkins, 2001; Paulsen et al., 2024; Rohs, 2009). This interpretive framework enables a more nuanced understanding of how newcomers interact with onboarding contexts and how different learning behaviors emerge from their engagement with onboarding contexts.

Onboarding is seen as a learning process composed of measures that are typically categorized as either formal or informal (Klein et al., 2015; Kowtha, 2018). Formal measures, such as training sessions or onboarding plans, have been shown to influence newcomers engagement in learning (Klein et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2015) and support competency development (Bauer et al., 2025; Frögéli et al., 2023). Informal measures can also offer learning opportunities and enhance social integration (Batistič, 2018). However, in times of rapid change and skilled labor shortages, FWL often adapts too slowly, whereas IWL and SRWL offer greater flexibility and responsiveness (Schaper et al., 2023). Moreover, much of the learning newcomers experience is assumed to occur beyond formal offerings, namely through day-to-day experiences, informal exchanges, and active participation in work tasks and learning opportunities (Buchheim and Weiner, 2014; Marsick et al., 2017; Mitschelen et al., 2025). This aligns with research showing that the extent to which measures are formal does not necessarily predict higher levels of newcomer integration (Klein et al., 2015).

To frame this study, we conceptualize onboarding as a structured process consisting of both formal and informal measures, which are generally intended to foster FWL and IWL, respectively. However, the learning process ultimately depends on how newcomers engage with these measures and whether newcomers engage in SRWL behaviors. While onboarding commonly includes both formal and informal measures as part of its structured integration efforts (Klein et al., 2015), these primarily reflect organization-driven offerings rather than learner-driven behaviors. In contrast, SRWL is neither systematically planned nor guaranteed by organizations but represents an individual strategy that newcomers may adopt. It remains unclear where and how SRWL occurs during onboarding, and how it interacts with formal or informal elements. This distinction is crucial for understanding how newcomers construct learning paths that go beyond what is formally provided. Within this perspective, employees actively construct individual learning paths during onboarding by navigating, combining, and interpreting different learning opportunities (Poell, 2017). The concept of individual learning paths highlights that learners flexibly integrate structured and unstructured experiences to pursue personally meaningful development (Poell et al., 2018). This view corresponds to the idea that onboarding can be seen as the first learning path newcomers encounter, composed of various measures (Pietilä, 2022). A learning path is understood as a set of learning-relevant activities that are coherent and meaningful to the employee, allowing them to strategically shape their own professional development within the organizational context (Poell et al., 2018; Poell and van der Krogt, 2014). Rather than merely following formal training programs, employees create learning paths by selecting relevant themes, engaging in diverse activities, and interacting with their social and organizational environment (Poell, 2017; Poell et al., 2018). These actions reflect active learning behavior and self-directed engagement, consistent with the principles of SRWL.

Organizations cannot provide all the information and activities needed to fully socialize new employees (Ashford and Black, 1996). Newcomers may not automatically receive all the information they consider necessary (Miller and Jablin, 1991; Ostroff and Kozlowski, 1992) and therefore must act proactively to acquire the information they need (Zhao et al., 2023). Research further notes that newcomers tend to engage in self-directed learning during onboarding (Klein et al., 2015; Tan et al., 2016). Newcomers must actively seek information and engage in learning—not through isolated measures alone, but by combining various activities encountered during onboarding (Miller and Jablin, 1991). This assumption aligns with emerging views of onboarding as an interactionist process that focuses not only on the organization but also on the newcomer (Batistič, 2018; Bauer et al., 2025), highlighting that newcomers can actively contribute to their onboarding experience and, consequently, to their own learning. However, although the concept of proactivity of newcomers during onboarding is established (Morrison, 1993), and there is existing research on formal and informal measures (Klein et al., 2015), empirical research on how newcomers actually learn during onboarding is lacking, particularly with regard to learning forms beyond formal measures, including IWL and SRWL (Yu et al., 2025).

Although earlier research acknowledges that onboarding is a key period for learning in organizations, the empirical exploration of how and what newcomers actually learn during this phase remains limited (Chan and Smith, 2000; Cooper-Thomas et al., 2020). In particular, there is little understanding of how specific onboarding content—such as compliance, connection, culture and clarification—is acquired (Klein and Heuser, 2008; Saks and Ashforth, 1997). In addition, researchers have called for more detailed exploration of onboarding practices in combination with newcomer learning (Klein et al., 2015) and a more detailed exploration of how specific measures translate into actual newcomer learning (Ashforth et al., 2007). However, we still lack nuanced insights into how engage with and learn from onboarding content in everyday practice.

RQ1: How do newcomers learn specific onboarding content?

Prior studies have not sufficiently investigated the nature of the learning process itself (Wang et al., 2015), and how learning behavior unfolds during the early stages of employment (Ashforth et al., 2007; Cooper-Thomas et al., 2020). Existing research largely conceptualizes onboarding as a process driven by the organization (Harrison et al., 2011), without fully examining how newcomers engage with learning opportunities (Wang et al., 2015). There is a particular need to explore constructs such as IWL during onboarding (Yu et al., 2025) and to the authors' knowledge, no study specifically investigated SRWL behaviors among newcomers during organizational onboarding. However, emerging perspectives emphasize the active role of newcomers in shaping their onboarding experiences (Boulamatsi et al., 2021). Likewise, we assume that onboarding as a learning path includes not only formal and informal measures (Klein et al., 2015), but also provides opportunities for newcomers to engage in SRWL behavior. Understanding how newcomers engage with their learning environment can offer valuable insights into how onboarding is experienced as a process of active learning and an individualized learning path (Poell and van der Krogt, 2014; Sprogoe and Elkjaer, 2010).

RQ2: How do newcomers engage with different forms of workplace learning during onboarding?

Addressing these gaps, the present study investigates how newcomers experience FWL and IWL during onboarding and how these learning forms relate to key onboarding content dimensions. It also examines where and under which conditions opportunities for SRWL arise, providing a more nuanced understanding of how newcomers shape their onboarding experiences. While formal and informal onboarding measures offer the structural foundation for workplace learning, they do not fully capture the dynamic and learner-driven nature of how newcomer learning unfolds in practice. In particular, SRWL, as a self-initiated and goal-directed process, has received limited attention in onboarding research. This study contributes to closing this gap by analyzing how newcomers engage with FWL and IWL during onboarding, but also how they actively transform these opportunities into SRWL paths.

This study makes several important contributions to the field of workplace learning, particularly within the context of organizational onboarding, where learning plays a central role. Theoretically, it links analytically distinct forms of workplace learning—formal and informal—with onboarding content dimensions, positioning SRWL as a complementary, learner-driven component. It expands existing models of workplace learning by integrating SRWL as a cross-cutting mechanism within onboarding contexts, highlighting how newcomers engage with both FWL and IWL opportunities. This approach provides new insights into how newcomers navigate and combine different learning forms to construct individual learning paths during onboarding. By building on and extending existing theories of workplace learning, the study emphasizes that onboarding is not merely a process of knowledge transfer, but a dynamic interaction between organizational structures and newcomer engagement. It contributes to a more differentiated understanding of onboarding as a process that offers multiple learning opportunities, which individuals experience in active and selective ways. Importantly, the study shows that formal and informal measures serve as core opportunities through which newcomers navigate their learning path during onboarding, while SRWL functions as an additional but crucial mechanism enabling them to take ownership and actively shape their learning trajectories. By identifying which specific onboarding measures offer opportunities for SRWL, the study not only addresses an area that has so far received little empirical attention, but also contributes to understanding how newcomers combine different forms of learning into individualized and meaningful learning paths during onboarding. From a practical perspective, the findings underscore the importance of designing onboarding processes that not only offer structured learning opportunities but also intentionally support IWL and SRWL. Enabling newcomers to actively shape their learning paths allows onboarding processes to better align with individual learning needs and preferences, potentially fostering more effective adjustment, greater satisfaction, and long-term retention.

2 Material and methods

2.1 Data collection and participants

Data were collected through qualitative, semi-structured interviews to capture the nuanced perspectives of newcomers on their onboarding and learning experiences. This method was chosen because interviews allow for in-depth exploration of individual experiences and enable participants to share detailed insights into their perceptions and the content they learned during onboarding. Semi-structured interviews, in particular, provide the flexibility to adapt questions based on the flow of conversation while ensuring that key themes are consistently addressed. While IWL and SRWL have often been studied using quantitative approaches, onboarding has rarely been studied as a holistic learning process—particularly through qualitative research that captures learner perspectives and contextual dynamics. This study therefore adopts a qualitative design to explore how newcomers actually experience and engage with different forms of learning during onboarding—especially those informal and context-sensitive aspects that are not easily captured through standardized instruments. The interviews were conducted online and recorded using the open-source software BigBlueButton. Each interview lasted between 60 and 120 minutes, including an introduction, informed consent, the interview itself, and a short debriefing.

The interview guide included questions covering participants' career paths, onboarding processes, and learning behaviors. To capture different learning forms, participants were asked about specific onboarding elements in which they engaged in learning including elements indicative of SRWL, such as expression of initiative or reflection. This allowed for a systematic exploration of SRWL as distinct from organizationally initiated onboarding measures. At the start of each interview, participants were welcomed, provided with a brief introduction to the study, informed about data protection protocols, and asked to provide their informed consent for participation and recording. The interview guide contained both introductory questions and questions aimed at addressing the research objectives, focusing on how participants engaged in learning behaviors during onboarding. After completing each interview, participants were debriefed. Participants were first asked (1) sociodemographic questions, (2) questions about their onboarding process in the most recent organizations, and (3) detailed questions about learning behavior, including formal and informal measures as well as SRWL and their active role in engaging in learning during onboarding. The interview guide was tested in two pilot interviews with individuals from public administration and healthcare sectors to refine the interview guide, leading to minor adjustments to improve clarity and language which were discussed by the authors. To enhance the credibility of the findings, a member check was conducted with selected participants. They were invited to reflect on preliminary interpretations of their statements, which helped validate the resonance and plausibility of the results. Additionally, the interview guide was slightly adapted during the study to ensure its relevance and alignment with emerging themes and participant feedback. The interviews were conducted in German, therefore, all participants had to be fluent in German.

The study sample comprises 40 individuals who were currently undergoing onboarding in various organizations. Recruitment was facilitated through the professional and personal networks of the authors, with eligibility criteria specifying that participants must be actively employed (rather than studying) and have gone through an onboarding process in their current organization. The use of convenience sampling allowed for efficient recruitment and ensured access to participants actively involved in onboarding processes, aligning with the study's focus on practical experiences. However, convenience sampling may introduce selection biases, as participants were recruited primarily through the authors' networks, which might limit the diversity of perspectives. Of the participants, 11 identified as male (27.5%) and 29 as female (72.5%), with an average age of 26.85 years (SD = 4.35). Most participants had a master's degree (45%). The participants represented diverse industries, including automotive (40%), agriculture (12.5%), and chemistry (7.5%), which were the most represented fields. The participants also came from diverse activity areas, with Development Engineering (7.5%), IT Management Consulting (5%), and Projects Management (5%) being the most represented fields. The sample consisted of individuals employed in organizations based in Lower Saxony, a region characterized by the strong presence of the automotive industry. Detailed demographic information for the participants is presented in Table 1.

2.2 Data analysis

The interviews were recorded, transcribed verbatim, and analyzed using qualitative content analysis with a combination of deductive and inductive coding (Mayring, 2010, 2021). To address the research questions, the coding framework was developed based on established literature on onboarding and workplace learning (Bauer, 2010; Decius, 2024; Tannenbaum and Wolfson, 2022). Drawing on Klein et al. (2015), we conceptualized onboarding as a learning path composed of FWL and IWL opportunities. These two forms served as the main categories in the coding framework and were complemented by onboarding content dimensions (compliance, clarification, connection, and culture; Bauer, 2010) as a second analytical layer. A third analytical layer captured behavioral indicators of SRWL (Kortsch et al., 2024), which was treated as a cross-cutting category that could emerge within both formal and informal contexts. Initial categories—such as FWL and IWL, onboarding content, and SRWL indicators—were deductively defined. This three-layered coding structure allowed us to explore not only what newcomers learned and through which onboarding measures, but also how actively they engaged in learning and shaped their onboarding process.

While the overarching framework was theory-driven, the coding process remained open to new emergent themes beyond the initial categories. However, no entirely new main categories emerged, as all relevant content could be meaningfully assigned to or integrated within the existing structure. MAXQDA software was used to facilitate the coding process, with additional inductive codes developed iteratively in joint coding sessions to address themes specific to this study (Steigleder, 2008). This combination of deductive and inductive approaches enriched the coding scheme and allowed for a comprehensive analysis of the data to address the research questions and to further elaborate on existing theories of workplace learning and onboarding (Fisher and Aguinis, 2017). Two researchers independently identified the codes, consolidating them in a shared meeting to ensure consistency and alignment with the theoretical framework (Rädiker and Kuckartz, 2019). The first author coded all interviews, while to ensure the study's credibility and a reflexive coding process, the second author was involved in each step of the analysis (Pratt et al., 2020). Any disagreements were discussed and resolved during research meetings, and experts on the topics were consulted to validate the coding process. To validate the coding framework, five transcripts were independently double coded and comparisons between the coding scheme led to refinements of subcodes and ensured alignment with the research questions. Any discrepancies were resolved through collaborative discussions. Inter-rater reliability, calculated based on five interviews that were double coded (Brennan and Prediger, 1981), using the kappa coefficient, yielded a Kappa score of 0.81, indicating strong agreement (Landis and Koch, 1977). Thematic saturation was used as a guiding principle during analysis. While saturation in homogeneous groups is often achieved within 12 interviews (Guest et al., 2006), our heterogeneous sample—spanning different onboarding experiences and occupational roles—required a larger number of interviews to ensure that all relevant themes and subgroups were adequately covered. Saturation was considered reached once additional interviews did not yield new categories or insights.

2.3 Qualitative quality criteria

Multiple measures were employed to ensure rigor and trustworthiness throughout the research process. The interview guide was iteratively refined through close collaboration and continuous feedback among the authors to ensure clarity and alignment with the research objectives. As described in Section 2.1, two pilot interviews informed minor adjustments. In addition, a member check was conducted to enhance credibility. Selected participants reviewed and confirmed the plausibility of key interpretations, thereby strengthening the interpretative validity of the analysis (Birt et al., 2016). Further rigor was ensured through a transparent and reflective research process at each stage, including the formulation of research questions, data collection, development of code and subcodes, and peer debriefing sessions. Regular feedback meetings and reflective discussions among the authors ensured robust qualitative standards in line with established criteria (Merriam, 2001; Patton, 2014). Transparency was ensured by systematically detailing and reflecting on each step of the research process, fostering intersubjectivity and aligning with established qualitative standards (Lüders, 2004).

3 Results

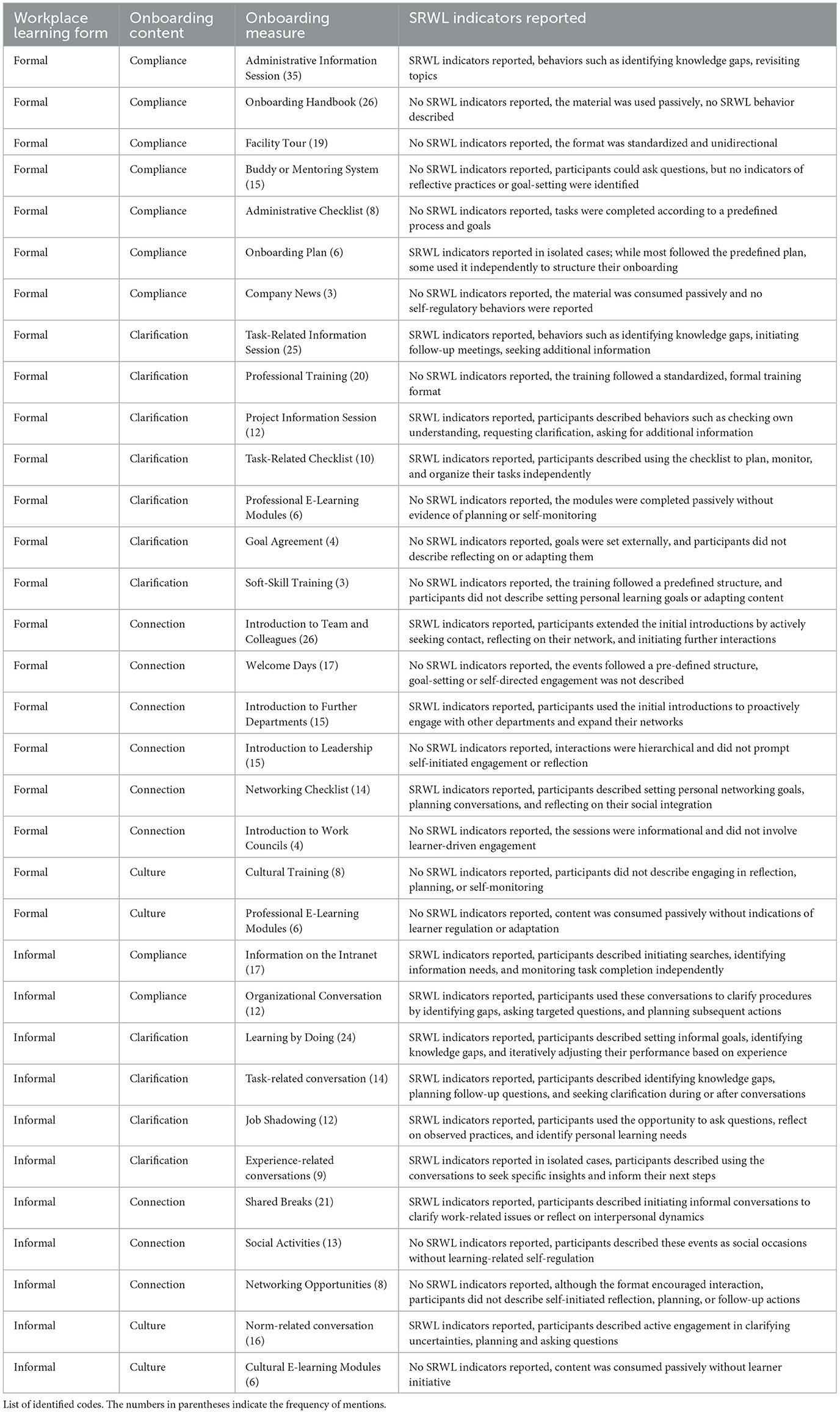

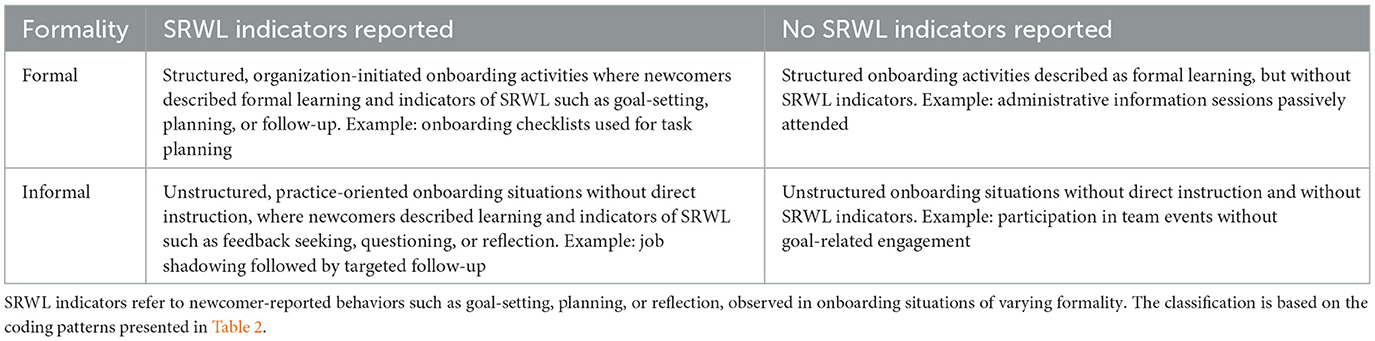

To address the research questions—how newcomers learn specific onboarding content and how they engage with different forms of workplace learning—this section presents the findings organized around the two predominant types of onboarding learning activities: formal and informal measures. These represent the key organizational formats through which onboarding content is delivered and encountered, forming the basis of newcomers' learning path. Within each learning form, the results are organized according to the four onboarding content areas: compliance, clarification, connection, and culture (Bauer, 2010). This structure allows us to analyze both what newcomers learn and how they actively engage in different learning opportunities. Due to space limitations, not all subcodes are presented in the following text, but a detailed overview of the identified codes can be found in Table 2. In addition, learning activities were assessed for SRWL indicators—that is, learner-reported behaviors such as goal-setting, monitoring progress, or seeking additional input (Decius et al., 2023; Sitzmann and Ely, 2011). Activities were categorized as formal or informal based on their structural design and initiation source, and SRWL was assessed independently, based on learner-reported behaviors such as goal-setting, planning, and monitoring. Accordingly, SRWL may co-occur with both formal and informal contexts, depending on how newcomers engage with the activity. To summarize the interplay between learning formality and the presence of SRWL indicators, Table 3 provides a classification of onboarding learning activities. The matrix distinguishes formal and informal learning and whether newcomers reported SRWL-related behaviors, such as goal-setting or feedback seeking.

Table 3. Classification of workplace learning activities during onboarding by formality and SRWL indicators.

3.1 Formal workplace learning

FWL during onboarding refers to activities that are structured, planned, and designed by the organization—typically delivered through standardized formats and predefined content (Kortsch et al., 2024; Tannenbaum and Wolfson, 2022). These measures aim to ensure clarity, consistency, and efficiency across onboarding experiences (Bauer et al., 2021; Klein et al., 2015). In line with our analytical framework, FWL is presented according to the four onboarding content areas (Bauer and Erdogan, 2011). For each measure, we examined whether and how indicators of SRWL occurred—that is, whether newcomers described learning behaviors indicative of SRWL—like engaging with the activity in a goal-directed, reflective, or self-initiated way (Kortsch et al., 2024; Sitzmann and Ely, 2011). This allowed us to explore not only the structural characteristics of onboarding measures but also how learners engaged with and extended these measures through SRWL behaviors.

Within the area of compliance, newcomers described several FWL elements that were planned, structured, and initiated by the organization. These measures aimed at conveying necessary administrative and regulatory information during onboarding. The most frequently mentioned format was the administrative information session (35 mentions), typically delivered by HR or supervisors. Participant 14 explained: “Administrative stuff was often clarified with the head of department in a session. Well, in terms of overtime, how to handle it or whether you can go on a business trip but also organizational stuff like how to deal with sick leave when you are sick.” Although these sessions followed a standardized structure, many participants described active engagement, such as asking questions, clarifying procedures, or following up on unclear aspects—indicating SRWL. As one participant noted: “Then I had to show initiative so that I could find out things like that, it turned out for me” (Participant 14). The onboarding handbook (26 mentions) represented another frequently referenced formal resource within the compliance dimension. Although the content was standardized and externally developed, participants used it autonomously and flexibly with respect to timing and sequence. As Participant 10 stated, “…for all that organizational stuff, checklists and so on, that was quite helpful.” Despite this flexibility, the handbook was primarily experienced as a passive resource rather than an active learning tool. Participants rarely reported engaging with it in a goal-directed or reflective manner. Consequently, while the format offered structural opportunities for SRWL, it was rarely perceived or utilized in ways that reflected SRWL behaviors.

Facility tours (19 mentions) represented another common format within the compliance dimension. Typically guided by HR representatives or experienced colleagues, these tours aimed to familiarize newcomers with the organizational infrastructure and spatial layout. As Participant 5 recalled, “The tour of the company was good, I learned how to find my way around here.” Participants consistently described the tours as structured, information-oriented sessions with limited opportunities for active engagement. While the tours were perceived as helpful for orientation, participants did not report SRWL indicators or engaging in SRWL during these tours. The buddy or mentoring system (15 mentions) was another formal measure supporting compliance-related onboarding learning. Typically initiated and coordinated by the organization, it involved assigning experienced colleagues to provide practical guidance during the initial phase. Participants described the support as helpful in clarifying administrative processes or day-to-day organizational routines. One participant shared, “Then we were given mentors who help us out if we have any questions.” (Participant 38). The support was highly valued, particularly for addressing daily inquiries during onboarding, but newcomers rarely reported engaging in reflective practices, goal setting, or self-directed planning. As the structure and purpose of the buddy system were predefined, participants described it mostly as reactive rather than self-regulated.

FWL activities related to clarification aimed to convey job-specific knowledge and professional expectations. Among the most frequently mentioned were task-related information session (25 mentions), described as structured meetings introducing newcomers to their responsibilities and role expectations. While the format was predefined and initiated by the organization, many participants emphasized the sessions' interactive nature. Participants reported asking questions and initiating follow-up meetings after reflecting on their understanding. Participant 20 explained: “At the beginning, mainly in meetings, when they explained my tasks to me.” Other participants similarly described that they could actively clarify uncertainties and initiate further meetings (e.g., Participants 1, 4, 12, and others). These examples indicate SRWL behaviors, particularly as participants described initiating follow-up meetings or seeking additional information. As one participant noted: “But you have to wait for the right moment and then speak to him. So, initiative in general in the project or it's good everywhere I think, but it was also very helpful and necessary there.” (Participant 4). Professional training (20 mentions) was another central element of formal onboarding, typically delivered through structured sessions or hands-on instruction by experienced colleagues. It focused on job-specific competencies and standardized procedures. As one participant noted for their learning experience: “Mainly through training sessions, practically in the laboratory area, by showing me lots of different laboratory methods and by doing various training courses” (Participant 25). Such training formats where highly valued, but they had predefined goals, content, and pacing. Participants did not report setting learning goals or reflecting on their progress, or adapting the training, suggesting only limited evidence of SRWL.

Project information sessions (12 mentions) were formal meetings organized to introduce newcomers to specific projects and their roles. Typically led by project leads or team members, they offered structured overviews of tasks, goals, and collaboration processes. Participants described these sessions as interactive, often prompting follow-up questions and further meetings initiated by the newcomers (e.g., P4, P13). Compared to other formal formats, they were seen as more dynamic and responsive to individual needs. Newcomers described checking their understanding, requesting clarification, or asking for additional information—behaviors indicative of SRWL. Another frequently mentioned clarification-related measure was the task-related checklist (10 mentions), provided by the organization to structure and track professional onboarding tasks. While formally designed, participants engaged with it to varying degrees. For instance, Participant 33 noted that they “I organized the task execution and completion on my own.” and others similarly reported identifying and planning tasks independently. Although the checklist did not explicitly prompt reflection or goal-setting, it required planning and monitoring, suggesting SRWL depending on the degree of autonomous engagement.

Several onboarding activities aimed at fostering connection supported newcomers in building social relationships across different areas of the organization. Common formats included introductions to the team and colleagues (26 mentions), leadership (15 mentions), and further departments (15 mentions). While these formats were typically planned and initiated by the organization, many participants reported actively shaping their experience by scheduling follow-up meetings or initiating further conversations. As Participant 5 noted: “Get-to-know-you gatherings with the team, but also with managers and other departments, helped me to find my way around and understand the working environment better. I initiated further like meetings with them to get to know them more like personally”. These interactions were not only valued for orientation but also used to expand personal networks. Descriptions of reaching out beyond the formal setting suggesting SRWL indicators such as initiative, goal orientation, and reflection on social or informational needs. One participant noted: “And if I didn't know something or wanted to get to know someone better, I asked colleagues directly if they could take half an hour. Yes, to get me involved in the topic, so to speak.” (Participant 1). Another formal measure aiming at connection was the networking checklist (14 mentions). While it was provided as part of the formal onboarding structure, participants engaged with it in varying ways. Participant 25 recalled: “There was this checklist with people who I should meet and talk to from the organization.” Others described proactively going beyond the predefined interactions by scheduling additional meetings to get to know colleagues better. For example, one participant described: “I could make the get-to-know meetings and then also made further meetings by myself. I wanted this to get to know them better or like personally more.” (Participant 13). These accounts suggest that while the format was formally structured, it offered varying opportunities for SRWL. Some newcomers completed the checklist as intended, whereas others used it to extend their engagement in the connection dimension and pursue personal networking goals—indicating SRWL behaviors.

FWL also addressed the cultural dimension of onboarding, primarily through two standardized formats: cultural training and professional e-learning modules with a cultural focus. Cultural training (eight mentions) was delivered as structured workshops aimed at conveying organizational values and norms. While some sessions allowed for limited interaction, participants reported little active engagement with the content, process, or goals. As one participant explained: “We also had an interactive workshop where we said that these are such values and the cultural stuff in the company” (Participant 1). Despite occasional interactivity, participants did not describe learning behaviors indicative of SRWL such as reflection or goal setting, suggesting limited SRWL. Similarly, professional e-learning modules addressing cultural topics (six mentions) were largely described as passive and predefined. They included online modules that participants could engage with to gain an understanding of professional topics and tasks. Participants noted that they followed the content as instructed, without adapting it to their needs or reflecting on its relevance. Accordingly, this format provided little evidence of SRWL behaviors.

Across onboarding content areas, FWL formats were characterized by structured delivery and predefined objectives, aligning with traditional organizational onboarding strategies. While many measures were perceived as informative and helpful, indicators of engagement in SRWL varied. Interactive formats—such as information sessions or team introductions—allowed newcomers to identify knowledge gaps, ask questions, or initiate follow-ups, indicating elements of SRWL. Similarly, some structured tools like task-related checklists were used in a self-directed manner, indicating SRWL through elements such as planning and monitoring. In contrast, static resources like handbooks or facility tours were used more passively, offering limited learner control. Overall, the occurrence of SRWL during formal onboarding depended less on the format itself than on the flexibility it allowed for active newcomer engagement.

3.2 Informal workplace learning

IWL refers to learning that takes place outside of structured instruction, typically in practice-oriented, unstructured contexts without direct teaching (Decius et al., 2019; Kortsch et al., 2024). Participants described IWL as an essential complement to formal onboarding measures, occurring across all four onboarding content areas. As in the previous section, we examine whether and how SRWL was reported in these informal contexts. IWL related to compliance frequently occurred through the use of information on the intranet (17 mentions). One participant shared, “We have an intranet. There even is a tab for newcomers, which is for all that onboarding stuff, so to speak, and there is a list of useful links. You can get to the claim for travel expenses here or to the application for leave here.” (Participant 2). Although these materials were provided by the organization, their use was neither mandatory nor guided, placing responsibility on the newcomers to decide when and how to engage with the information. Several participants reported independently searching the intranet to clarify internal procedures or complete administrative tasks. These illustrate how IWL supported by organizational infrastructure but initiated and regulated by the learners themselves. The described behaviors—identifying information needs, seeking out resources, and monitoring learning progress—can be seen as indicators of SRWL. As one participant noted: “I often used the search function on the intranet or in One Note. Of course, you also try to help yourself first. If you don't get any further, you ask the others, that's how it always was with us.” (Participant 17). IWL related to compliance and clarification also occurred through organization-related (12 mentions) and task-related conversations (14 mentions). These interactions were typically encouraged within the onboarding framework—for example, during team meetings or joint work phases—but were not formally structured or guided in content. As Participant 12 explained, “We also clarified questions when they occurred. Like in meetings or when we sat together and worked.” Such conversations served to clarify administrative procedures and professional tasks in real time, especially when formal materials left gaps. Although the setting was organizationally provided, the learning process itself relied on newcomers identifying knowledge gaps, asking targeted questions, and sometimes planning next steps—behaviors that reflect indicators of SRWL in IWL settings.

Learning by doing (24 mentions) was the most frequently described IWL approach within the clarification category. Participants reported independently engaging with tasks, trying out different methods, and gradually building competence through hands-on experience. Several participants described monitoring their own understanding, adapting their actions, and reflecting on outcomes. As one participant explained: “It was basically learning by doing. I mean, it's not rocket science, right? We just kind of worked our way through it, I'd say.” (Participant 33). These accounts reflect indicators of SRWL, with newcomers setting informal goals, identifying knowledge gaps, and iteratively improving their performance. Moreover, this activity can be classified as self-based IWL, as it is conducted primarily independently, without the involvement of others (Decius and Hein, 2024). Within the clarification dimension, job shadowing (12 mentions) allowed newcomers to observe experienced colleagues and understand everyday work routines. Although typically unstructured, the format offered opportunities for interaction and contextualized learning. Newcomers reported asking questions and actively engaging during these periods, which enriched their understanding. One participant shared, “During these two weeks I basically shadowed my predecessor (…), got to see the daily grind, the everyday work routines and stuff like that.” (Participant 24). These informal observations often included moments of self-initiated inquiry and reflection, which are indicators of SRWL. For example, Participant 11 noted: “So I would sit next to someone at work, for example at a machine, and watch them. Afterwards or during the process I could ask questions. And then subsequently I also read up on things like that in the online academy, so specialist knowledge or something I was still looking for.” When participants deliberately used the experience to deepen their understanding or identify further learning needs, job shadowing served as a setting in which SRWL could unfold. Job shadowing can further be classified as social-based IWL, as newcomers reported typical activities such as model learning and seeking feedback (Decius and Hein, 2024).

Shared breaks (21 mentions) emerged as a frequent IWL setting within the connection dimension. These unstructured moments—such as lunch or coffee breaks—provided newcomers with informal opportunities to connect with colleagues. As one participant shared, “But that was pretty cool because they just say, let's go for lunch or have a coffee, you know, to get to know each other better.” (Participant 6). While not formally structured, these interactions supported relational learning through self-initiated conversations, enabling newcomers to reflect on social dynamics or seek clarification in a casual setting. The autonomy and initiative of newcomers in shaping them indicate SRWL. Social activities (13 mentions), such as bowling nights or team cooking events, were also mentioned as contributing to newcomers' social integration and were typically organized by the company. Participants appreciated the occasions for creating a relaxed environment to get to know colleagues. However, descriptions of SRWL indicators were largely absent, suggesting that while these activities fostered connection, they offered limited opportunities for SRWL.

Within the culture dimension, norm-related conversations (16 mentions) served as a key form of IWL. While unstructured in nature, these interactions were embedded in the broader onboarding context and often occurred in organizationally facilitated settings such as team meetings or informal exchanges with colleagues. Participants valued these conversations for helping them understand implicit behavioral expectations and organizational norms. In several cases, newcomers reported using such moments to clarify uncertainties or ask specific questions—indicating SRWL behaviors. As one participant noted: “I've heard or been told a lot about manners and so on by my colleagues. And then sometimes I've thought about how to do this and that or who to ask and so on.” (Participant 26). Thus, although informally structured, they facilitated SRWL when newcomers used them to actively engage with cultural expectations.

IWL emerged as a key component of onboarding, particularly within the dimensions of clarification and culture. Activities such as job shadowing and task-related conversations enabled situated, experience-based learning that newcomers often shaped through their own initiative. Intranet searches and informal exchanges further reflected SRWL features like monitoring and addressing knowledge gaps. While not all informal measures showed many elements of SRWL, several provided space for newcomers to take ownership of their learning process. These findings highlight how IWL supports the construction of individualized learning paths in onboarding that extend beyond formal structures.

4 Discussion

The present study explored how newcomers engage in learning during onboarding by examining a wide range of learning activities across the four onboarding content dimensions: compliance, clarification, connection, and culture. The findings indicate that newcomers engage with both formal and informal activities and that learning during onboarding is shaped not only by organizationally provided measures but also by how newcomers actively interact with them. This highlights onboarding as a process co-constructed by organizational structures and learner behavior, rather than a set of static learning measures. How newcomers approach onboarding—whether by following predefined paths or by actively shaping their experiences—shapes how and what they learn. This finding supports conceptualizations of onboarding as a dynamic learning path rather than a static program (Poell, 2017; Poell and van der Krogt, 2014).

FWL played a central role in newcomers' onboarding experiences across all onboarding dimensions, particularly in compliance and clarification. These activities were typically planned, structured, and trainer-led—for example, in the form of professional trainings. Consistent with previous research, FWL supported learning and the acquisition of explicit knowledge about organizational policies and responsibilities (Billett, 1996), thereby providing a reliable foundation for integration (Svensson et al., 2004). However, FWL was not perceived as entirely passive. The findings show that several formal formats—for example, onboarding plans and structured sessions—enabled active engagement. Participants described behaviors such as asking follow-up questions, scheduling further meetings, and flexibly using provided resources. These actions indicate SRWL processes such as monitoring, identifying knowledge gaps, and regulating learning processes (Sitzmann and Ely, 2011). Thus, the opportunities for SRWL within formal measures depend not solely on their structure, but on learner's autonomy and the format's flexibility. When applied flexibly, formal elements may support individualized learning paths (Poell, 2017). At the same time, the findings point to a potential limitation in some formal designs: while structured formats offer clarity and reduce uncertainty (Bauer et al., 2021; Paulsen et al., 2024), they may constrain SRWL when learning goals, content, and processes are fully predefined. Especially in formats like e-learning modules or handbooks, participants rarely reported indicators of SRWL such as monitoring or reflection (Kortsch et al., 2024; Sitzmann and Ely, 2011). These formats provided consistency but lacked flexibility—aligning with prior research suggesting that excessive structure can inhibit learner autonomy and adaptability (Frögéli et al., 2023).

IWL was reported across all onboarding dimensions and served as a key mechanism for acquiring job-relevant knowledge and building interpersonal connections. Unlike formal activities, it occurred through often unstructured, work-embedded interactions that were not tied to explicit objectives. These situations supported learning about organizational practices and norms beyond formal instruction. This flexibility also created favorable conditions for SRWL. As informal settings often lacked predefined goals or processes, they allowed newcomers to ask questions, monitor understanding, and reflect on learning (Kortsch et al., 2024; Sitzmann and Ely, 2011). Accordingly, newcomers described IWL situations offering indicators of SRWL, especially within the clarification and connection dimensions. Particularly in the connection dimension, activities such as social interactions and conversations enabled learning and integration. In line with previous research, participants emphasized the importance of conversations and interpersonal contact for acquiring social-interactional knowledge (Jeong et al., 2018). These findings confirm that IWL contributes to the development of interpersonal competencies (Lewalter and Neubauer, 2020), which are essential for effective integration (Ashforth et al., 2007). They also support earlier findings that newcomers actively seek out interpersonal interactions to navigate unfamiliar organizational environments (Ellis et al., 2015). Many activities reflected social-based IWL, where learning occurred through observation or feedback (Decius and Hein, 2024). Other activities, like learning by doing, aligned with self-based IWL, where learners independently searched for knowledge or solutions. This distinction illustrates how IWL fosters SRWL through both individual and social learning pathways (Decius and Hein, 2024).

The reported SRWL indicators showed that SRWL emerged across all onboarding content dimensions and was embedded in both FWL and IWL activities. Rather than occurring in isolation, SRWL complemented other learning forms depending on the learner's autonomy and the openness of the activity. SRWL indicators involve individual initiative, goal-setting, and reflection, allowing learners to actively shape their learning process (Kortsch et al., 2024; Sitzmann and Ely, 2011). Our findings show that SRWL often occurred when onboarding activities invited learner involvement—such as following up on materials, asking clarifying questions, or using informal settings for self-initiated learning. These behaviors reflect SRWL indicators and components like goal-setting and monitoring (Sitzmann and Ely, 2011). Newcomers described identifying gaps, pursuing additional information, and monitoring their understanding. These findings support models that emphasize learner autonomy and engagement during organizational entry (Schraw et al., 2006). Importantly, SRWL was not limited to self-initiated activities outside the organization's framework. Many structured learning elements—like checklists or e-learning modules—only unfolded their full learning potential when learners engaged with them proactively. These examples show that formal formats can support SRWL when learners adapt and expand them based on personal goals. This reflects a learning process that is externally structured but internally driven, where learners define their own trajectory (Panadero, 2017; Poell, 2017). Thus, SRWL during onboarding often emerged within or alongside FWL and IWL (Kortsch et al., 2024; Sitzmann and Ely, 2011). This supports the idea that onboarding should not be conceptualized through rigid learning typologies but as an integrated process with individual learning paths (Poell, 2017). Rather than viewing SRWL as separate, these findings suggest that it frequently accompanies other workplace learning forms—depending on learner's initiative and the format's flexibility (Richter et al., 2020; Rohs, 2009). These dynamics help explain why some onboarding elements offered more opportunities for SRWL than others—even when structurally similar. This supports the call for more integrated, learner-centered approaches to work-related learning in dynamic environments (Kauffeld et al., 2025; Kortsch et al., 2024), as they reveal how FWL, IWL, and SRWL interact and how newcomers shape their onboarding experience.

4.1 Theoretical contributions

This study contributes to onboarding theory by reconceptualizing onboarding as a dynamic learning process shaped by the interaction of FWL, IWL, and SRWL forms, highlighting how newcomers actively construct individualized learning paths across content dimensions. This study integrates the different learning forms and examines their relevance across the four onboarding content dimensions: compliance, clarification, connection, and culture. It provides insights into which formal and informal onboarding measures are used, where specific onboarding content is learned, and in which situations newcomers display indicators of SRWL. By mapping learning forms to onboarding dimensions, the study refines existing onboarding models that have primarily focused on content or outcomes without systematically linking them to learning processes. Building on research that conceptualizes onboarding as more than an instructional process (Becker and Bish, 2021; Fang et al., 2011), the study extends this view by showing how learning forms differ in the extent to which they involve SRWL during onboarding. It thereby enriches workplace learning models that have traditionally examined FWL, IWL, and SRWL in isolation (Kauffeld et al., 2025; Kortsch et al., 2024; Rohs, 2009) and shows how SRWL can be seen as a cross-cutting mechanism that enables newcomers to navigate and personalize both FWL and IWL opportunities into meaningful and self-directed onboarding experiences.

While prior research often treats FWL, IWL, and SRWL as distinct categories (Decius, 2024; Kauffeld et al., 2025; Kortsch et al., 2024), this study shows how these forms frequently co-occur and interact within onboarding and how newcomers make use of different learning forms and SRWL activities. Newcomers reported engaging in structured formats while also navigating self-directed or IWL opportunities. This challenges assumptions that specific learning forms are tied exclusively to certain onboarding contents (Billett, 1996) and highlights how they interact in complementary ways (Gerhardt et al., 2022). Indeed, as prior literature emphasizes, the boundaries between FWL, IWL and SRWL are often blurred and overlapping in practice, making it difficult to draw clear distinctions (Cerasoli et al., 2018; Kauffeld et al., 2025; Paulsen et al., 2024). Our findings align with these models (Kortsch et al., 2024; Schraw et al., 2006) and position SRWL as a cross-cutting mechanism in work-related learning, cutting across formal and informal formats. By emphasizing this interplay, the study presents onboarding as an integrated and dynamic learning process rather than isolated strategies (Decius, 2024; Schaper et al., 2023). This reconceptualization challenges linear onboarding models and supports a layered understanding of learning, in which newcomers simultaneously follow, adapt, and expand upon structured learning trajectories. These findings resonate with the concept of individual learning paths (Poell, 2017), which view learning as a result of interacting organizational structures and learners contributions. Although learning paths were not investigated directly, the results show that newcomers actively combine learning opportunities across contexts, indicating that onboarding can enable meaningful and individualized learning trajectories (Poell et al., 2018). In doing so, the study contributes to a more holistic understanding of work-related learning, fostering both individual autonomy and organizational alignment.

A central contribution lies in refining the role of newcomers. Moving beyond earlier conceptualizations of newcomers as passive recipients (Morrison, 1993; Sprogoe and Elkjaer, 2010), the findings show that they actively shape their onboarding—by asking questions, initiating follow-up meetings, and flexibly using available resources. This suggests that newcomers not only absorb onboarding content but also co-construct their learning process through self-regulated engagement. Moreover, the findings indicate that newcomers' activity can extend beyond individual integration. Their self-regulatory engagement can not only support their learning but also become a mechanism of feedback to the organization, surfacing gaps in onboarding structures or introducing new perspectives. This highlights the dual role of newcomers as learners and contributors, supporting innovation and reflexivity in onboarding systems (Boulamatsi et al., 2021; Jokisaari and Vuori, 2014). This supports a more participatory and interactionist view of newcomers during onboarding, in which learning is not simply delivered by the organization, but also shaped by those experiencing it (Bauer et al., 2025; Zhao et al., 2023). The study also advances onboarding theory by connecting specific onboarding practices to learning processes and content dimensions. Although various onboarding measures are used in practice, their alignment with learning mechanisms has been underexplored (Klein et al., 2015; Mitschelen et al., 2025). This study helps address this gap by showing how different measures relate to FWL, IWL, and SRWL, and how newcomers actively engage with and experience them in real onboarding situations.

4.2 Practical implications

This paper offers practical implications for designing onboarding processes that foster both newcomer learning and enable meaningful contributions. Rather than treating onboarding as a one-directional process of information delivery, organizations should view it as a learning process that actively engages newcomers (Revsbæk, 2014; Sprogoe and Elkjaer, 2010). Such engagement not only enhances individual learning but may also generate organizational value through newcomer-driven insight and innovation (Boulamatsi et al., 2021). To support this dual function of onboarding—as both learning and contribution—organizations should deliberately enable SRWL across all onboarding formats. A first step is to move beyond standardized onboarding tracks toward more individualized learning paths. Combining multiple learning forms allows for richer and more adaptive learning experiences (Kortsch et al., 2019; Mitschelen et al., 2025). By tailoring onboarding formats to newcomers' needs and backgrounds, organizations can strengthen integration and potentially reduce onboarding costs (Batistič, 2018). Formal elements such as training sessions and mentorship remain important for foundational knowledge (Ostroff and Kozlowski, 1992). However, to foster SRWL, these formats should include space for adaptation and initiative—for example, onboarding checklists that allow newcomers to prioritize or modify tasks, or training phases that include elements of self-monitoring and goal setting. Additionally, exchange meetings with experienced colleagues can help newcomers clarify expectations, reflect on their progress, and contribute ideas (Klein et al., 2015; Moser et al., 2018).

IWL thrives in relational, low-pressure settings (Decius et al., 2021; Kortsch et al., 2024). Organizations must therefore reduce structural barriers such as time pressure and excessive workload, which can limit opportunities for informal interaction and self-regulation (Decius et al., 2021; Klein and Heuser, 2008). These stressors can reduce the effectiveness of IWL and prevent SRWL from unfolding (Cerasoli et al., 2018). To address this, onboarding programs should offer protected time for learning and social interaction—for example, through structured onboarding phases or informal peer events (Mitschelen et al., 2025; Moser et al., 2018). A realistic onboarding pace and protected time for informal exchange can enhance the effectiveness of IWL and SRWL (Cerasoli et al., 2018).

Digital resources are another essential element for enabling SRWL and IWL (Kortsch et al., 2019). While these tools offer flexible, self-paced access to information (Jansen et al., 2020), their effectiveness depends on the learner's ability to take ownership of the process (Jin et al., 2023). To support this, digital materials should incorporate elements like self-monitoring tools, feedback loops, and optional depth of content, and should allow revisiting content as needed (Mitschelen et al., 2025; Schraw et al., 2006; Welk et al., 2023). Digital onboarding tools should be designed not only to deliver content but to empower newcomers to plan, track, and reflect on their progress (Mitschelen et al., 2025). This also requires acknowledging that newcomers differ in prior experience and preferred learning modes (Mahony et al., 2012; Moser et al., 2018). Flexible onboarding formats —including digital ones—can support diverse needs and foster learner-centered integration (Poell, 2017). Furthermore, relational resources remain essential to onboarding success (Ellis et al., 2015; Mitschelen et al., 2025). Newcomers frequently emphasized the value of access to experienced colleagues for questions and feedback. This confirms prior research showing that relational support strengthens both immediate learning outcomes and long-term performance, clarity, and integration (Harrison et al., 2011). Participants reported IWL and SRWL as effective when they felt welcomed and had someone available to answer questions. This aligns with research suggesting that psychological safety fosters proactive learning behaviors (Kittel et al., 2021; Margaryan et al., 2013). Organizations should therefore foster an open, inclusive culture in which newcomers feel safe to ask questions, take initiative, and actively use available resources (Kittel et al., 2021).

4.3 Future research

This study highlights several avenues for future research to advance the theoretical understanding of onboarding as a learning process. A key priority lies in examining SRWL during onboarding—identified here as a critical yet underexplored aspect of newcomer learning. While proactivity has been discussed in the context of onboarding (Bauer et al., 2025; Zhao et al., 2023), the role of SRWL and its variations across different onboarding formats remains insufficiently understood. Future studies should explore when SRWL behaviors emerge, how they are enabled or constrained by organizational structures, and under what conditions newcomers take ownership of learning (Bauer et al., 2025). In addition, future research should examine the temporal interplay between FWL, IWL, and SRWL. Rather than treating these learning forms as static categories, scholars could explore how newcomers shift between them over time, depending on changing needs and onboarding stages (Decius et al., 2023; Kortsch et al., 2024). Prior work suggests that technical knowledge is prioritized early in onboarding, while feedback-seeking and social integration become more important in later phases (Chan and Smith, 2000; Jablin, 2001). Investigating such temporal dynamics would help align onboarding formats with newcomers' changing learning goals.

Moreover, the mechanisms underlying onboarding-related learning require further attention. While this study mapped learning behaviors and formats, it did not examine how cognitive and motivational processes like goal-setting or persistence influence learning during onboarding. Future work could build on theoretical models of learning cycles or self-regulation (Decius et al., 2024a; Margaryan et al., 2013) to investigate how these psychological mechanisms interact with onboarding structures and shape learning outcomes. To gain a deeper and more generalizable understanding of these mechanisms, future research should also apply quantitative approaches—for instance, by using validated instruments to assess motivational factors or SRWL strategies across larger newcomer samples. Future research could further explore contextual and personal factors shaping learning during onboarding and their interplay. The findings show that IWL is often facilitated through verbal exchanges and was particularly helpful for onboarding contents like connection. Research suggests that IWL may be more effective in smaller or less hierarchical organizations; therefore, future studies could examine how organizational factors like size, industry, hierarchy, or degree of formalization influence IWL processes and outcomes (Decius et al., 2019). Additionally, participants identified organizational culture as a key factor influencing their learning and their ability to actively contribute. Future research should investigate how culture supports or hinders learning, particularly social forms of IWL (Jeong et al., 2018; Kittel et al., 2021). Individual characteristics such as curiosity or psychological capital could also affect engagement and outcomes (Jeong et al., 2018). Prior experience or education level may influence how newcomers access and utilize learning opportunities—e.g., more educated individuals may engage more in IWL and SRWL (Cerasoli et al., 2018; Decius et al., 2023). Comparative studies across different organizational types and employee groups could inform how onboarding can be better tailored to different groups.

The “dark side” of IWL also warrants further investigation. While IWL offers flexibility, it presents challenges such as limited control over content and difficulties in evaluating outcomes (Paulsen et al., 2024). The current findings provide insight into what is learned informally and self-regulated during onboarding, but future research should examine whether this learning aligns with organizational objectives and how its effectiveness can be assessed (Kortsch et al., 2024). This could include studies focusing on both newcomers and those responsible for onboarding processes. Developing reliable methods to monitor and guide IWL and SRWL would help organizations leverage their benefits while mitigating potential risks.

While this study provides insights into short-term learning experiences, the long-term impact of onboarding-related learning remains underexplored. Although onboarding has been linked to outcomes such as role adjustment and commitment (Ashforth et al., 2007; Schaper et al., 2023), yet we know little about how such effects evolve over time. Longitudinal research is needed to examine how onboarding practices influence long-term development and retention. Factors such as supervisor and peer support have been shown to enhance learning transfer (Massenberg et al., 2015; Mehner and Kauffeld, 2023), and should be considered in future studies with longitudinal designs (Mehner et al., 2024; Richter and Kauffeld, 2020). Additionally, while digital tools were mentioned as helpful, they were not yet integrated systematically. Prior research has focused primarily on digital onboarding in higher education (Schilling et al., 2024, 2022), but their use in workplace onboarding remains underexplored (Mitschelen et al., 2025). Future research should examine how digital tools like e-learning or interactive platforms can support FWL, IWL, and SRWL in onboarding. This includes investigating how they can reduce cognitive overload and promote self-regulated learning (Mayer and Moreno, 2003). Lastly, future research could expand on the role of newcomers not only as active participants in their learning but also as contributors of new perspectives and knowledge during the onboarding process (Sprogoe and Elkjaer, 2010). Investigating how newcomers share their insights and experiences with the organization could support innovation and organizational improvement (Boulamatsi et al., 2021). By exploring how these active contributions influence both individual and organizational development, future studies could deepen our understanding of onboarding as an interactive process that includes opportunities for knowledge-sharing and innovation (Boulamatsi et al., 2021; Jokisaari and Vuori, 2014).

4.4 Limitations

While this study offers valuable insights into the interplay of learning forms and onboarding content, it also has limitations. First, the sample predominantly consisted of participants from European organizations, which may limit the transferability of the findings. Cultural differences in onboarding practices and learning approaches could influence the results. Therefore, future research could expand the scope to include participants from diverse regions, such as Asia, the Americas, and Arabic region, to explore cultural influences on onboarding and learning (Bauer et al., 2025; Mitschelen et al., 2025; Schilling et al., 2024). Additionally, participants were recruited primarily through the authors' professional and personal networks, which may have introduced selection bias. It is possible that those who volunteered for the study were more interested in learning and onboarding than the general population. Although this sampling method allowed for an in-depth exploration of the research questions, future studies should aim for broader and more diverse samples to enhance the robustness of the findings. The study relied on retrospective self-reports from newcomers in Lower Saxony, which may impact the dependability of the findings (Margaryan et al., 2013). Learning is a complex and multifaceted process; components of acquired knowledge are often tacit and difficult to articulate (Nonaka, 1991), and individuals may not always be aware of what they have learned (Alavi and Leidner, 2001), which is likely true for onboarding and this study. Despite this, qualitative methods were appropriate for exploring perceptions of learning strategies and onboarding practices, given the early stage of research in this field. Nevertheless, future studies could use longitudinal and quantitative designs to investigate changes over time and relationships between learning forms and onboarding content (Margaryan et al., 2013). Finally, our categorization of FWL, IWL, and SRWL reflects an interpretive framework based on participants' descriptions. As previous research has emphasized, the different workplace learning forms often overlap in theory and practice, making clear-cut distinctions analytically useful but inherently limited (Kauffeld et al., 2025; Paulsen et al., 2024).

5 Conclusion

In a knowledge-based society, effective learning during organizational onboarding is essential for both individual development and organizational success. This study conceptualizes onboarding as a dynamic learning process shaped by the interaction of FWL, IWL, and SRWL. Newcomers are not passive recipients of onboarding content but actively construct individualized learning paths across different onboarding dimensions, depending on both organizational structures and learners' engagement. By illustrating how different learning forms complement one another and where SRWL emerges, the study refines existing onboarding and workplace learning models. Practically, the findings highlight the need for onboarding designs that go beyond static information delivery and instead foster flexibility, initiative, and meaningful learner involvement. Organizations should create conditions that support SRWL and IWL, while ensuring that formal structures remain adaptable and open for interaction. Future research should further explore how newcomers' active engagement can be leveraged not only for individual integration but also for organizational learning and innovation. As onboarding increasingly spans hybrid and digital formats, fostering learner autonomy and a supportive learning culture will be critical for sustainable newcomer development.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Ethics Commission TU Braunschweig, ID number D_2022_18. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

AM: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft. SK: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research was funded by the Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action grant number 16TNW0002A. We acknowledge the support by the Open Access Publication Funds of the Technische Universität Braunschweig.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. During the preparation of this work, the author(s) used the Large Language Model ChatGPT to assist with grammar checking and spelling corrections. After using this tool, the author(s) reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Adler, A. B., and Castro, C. A. (2019). Transitions: a theoretical model for occupational health and wellbeing. Occup. Health Sci. 3, 105–123. doi: 10.1007/s41542-019-00043-3

Alavi, M., and Leidner, D. E. (2001). Review: knowledge management and knowledge management systems: conceptual foundations and research issues. MIS Q. 25, 107–136. doi: 10.2307/3250961

Ashford, S. J., and Black, J. S. (1996). Proactivity during organizational entry: the role of desire for control. J. Appl. Psychol. 81, 199–214. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.81.2.199

Ashforth, B. E., Sluss, D. M., and Saks, A. M. (2007). Socialization tactics, proactive behavior, and newcomer learning: integrating socialization models. J. Vocat. Behav. 70, 447–462. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2007.02.001

Batistič, S. (2018). Looking beyond - socialization tactics: the role of human resource systems in the socialization process. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 28, 220–233. doi: 10.1016/j.hrmr.2017.06.004

Bauer, T. N. (2010). Onboarding New Employees: Maximizing Success. SHRM Foundation. Available online at: https://penedulearning.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Onboarding-New-Employees_Maximizing-Success.pdf

Bauer, T. N., and Erdogan, B. (2011). “Organizational socialization: the effective onboarding of new employees,” in APA Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology, Vol. 3, ed. S. Zedeck (Washington, DC: American Psychological Association), 51–64.