- 1International Institute for Management Development, Lausanne, Switzerland

- 2Department of Organizational Behavior, Faculty of Business and Economics, University of Lausanne, Lausanne, Switzerland

Modern workplaces subject employees to relentless pressures and demands, marked by perpetual change, uncertainty, and intricate challenges. Accordingly, many employees are struggling to cope, leaving them feeling “overwhelmed”. Despite its colloquial prevalence, the experience of being overwhelmed remains a powerful yet ill-defined phenomenon. This inductive study draws on 94 first-person narratives and ratings to examine the affective components, context and workplace impact of this debilitating experience. From our thematic analysis emerges the definition of overwhelm as a distinct affective state occurring at the perceived tipping point when situational demands are appraised as exceeding available resources, and is marked by heightened alertness yet bodily fatigue, limited outward expression, withdrawal or mental freeze, and the conscious experience of predominantly negative feelings. Recurring appraisals of demands were unpredictable, unreasonable, and outweighing an individual's resources, common to stress-related affective states with an almost exclusively negative valence. We highlight common antecedents, consequences, and coping strategies that might support employees and organizations to mitigate its detrimental outcomes. We conclude by offering directions for future research and practical interventions aimed at enhancing employee well-being.

Introduction

Workplace stress and its consequences have become ubiquitous in modern workplaces. Amidst ongoing uncertainty and constant change, complex workplace demands, and a persistent feed of information from our always-on devices, recent reports indicate that over 40% of employees experience a lot of daily worry or stress, a record high since 2021 (Gallup, 2022, 2023). Nearly 60% of employees find that workplace stress impacts their performance and motivation, highlighting emotional exhaustion, feeling disengaged, and a desire to keep to themselves (American Psychological Association, 2023). Workplace stress has been linked to a myriad of physical and mental health impairments, including burnout, and adversely affects organizations by for example increasing turnover intentions and diminishing performance (Demerouti et al., 2021; Fugate et al., 2012; Lee et al., 2013; Maslach et al., 2001; Steinhardt et al., 2011).

A wealth of research highlights that the negative consequences of stressors depend on the individual's perception of the demands (i.e., task load, pressure) and their ability to cope with those demands. At the point when perceived demands exceed an individual's coping resources, the individual transitions into what has been described as a threat state (Bliese et al., 2017; Lazarus and Folkman, 1984; Meijen et al., 2020; Tomaka et al., 1993). Before this critical point, demands can drive both positive effects (e.g., proactive work behavior) as well as negative effects at work such as work withdrawal (Gerich and Weber, 2020; Horan et al., 2020; Liao et al., 2025; Reis et al., 2017). After this tipping point, negative effects more likely accumulate, impairing affective well-being and health, while performance levels may potentially hold or even increase temporarily through increased effort to meet the demands.

However, despite recognizing the importance of this shift in an individual's experience from “I am coping” to “I am no longer coping”, little research has explored the underlying affective processes that characterize this transition into a threat state, which in turn, drives coping behavior, performance and health outcomes (Balducci et al., 2011; Christensen and Aldao, 2015; Lazarus, 2006; Perrewé and Zellars, 1999). Understanding how individuals experience this tipping point—which we will refer to as “being overwhelmed”—is critical, as it holds key implications for mitigating the negative downstream consequences of stress, supporting individuals to better cope, while supporting organizations to foster healthier, more sustainable work environments.

In English language, the word overwhelm(ed) describes a distinct experience of being “overloaded or overcome” (Kilgarriff et al., 2014). The term has gained popularity, appearing in business magazines (e.g., Dunn, 2024; Smith, 2022) and global news and information outlets (Google Trends, used in mental health research trends, see Alibudbud, 2023). Notably, its usage has surged in online health-related searches, particularly during times of societal change, conflict or strain, such as during the COVID-19 pandemic). Although recent work in the emotion literature has begun to position “being overwhelmed” as a distinct affective state (Fontaine et al., 2022), its specific manifestations remain underexplored. Only a handful of studies have used the concept of overwhelm, without clearly defining it (Hunziker et al., 2011; van der Kolk et al., 1996). This lack of clarity underscores the need for further conceptual and empirical clarification. In particular, when and how it emerges, its defining characteristics, and its potential consequences for individuals and organizations.

We thus conducted an exploratory study of 94 working individuals' experiences of “being overwhelmed” and contribute to research and theory in several ways. First, we contribute to the emotion literature by providing both a formal definition with empirical depth of an affective state that is pervasive and impactful in the everyday workplace but has not previously been defined. While being overwhelmed has been acknowledged as a distinct affective state, its manifestation, antecedents, and implications have remained underexplored. By mapping its relevant affective components, we offer a theoretically grounded and experientially rich understanding of this state.

Second, we contribute to the stress and coping literature by shedding light on a specific tipping point in the stress process—the moment when perceived demands exceed personal resources, triggering overwhelm. While contemporary models such as the Job Demands-Resources (JD-R) theory (Bakker and Demerouti, 2007) and the Conservation of Resources (COR) theory (Hobfoll and Freedy, 1993; Hobfoll et al., 2018) emphasize the balance between demands and resources, they do not delineate the transition toward an imbalanced state (referred to as a threat state) that precedes negative outcomes such as withdrawal, reduced well-being, and burnout. By capturing employees' first-person experiences, we offer a contextual and detailed understanding of how individuals experience and make sense of this pivotal moment, thus responding to repeated calls for more theoretical and in-depth empirical grounding of the subjective dimensions of stress (Dewe, 1992; Mazzola et al., 2011).

Third, we contribute to the management literature by offering an employee-centered perspective on overwhelm as a workplace phenomenon. Although the term is widely used in professional discourse, it has not been rigorously examined from an empirical or theoretical standpoint. By analyzing employees' lived experiences, we provide actionable insights for organizations seeking to recognize, mitigate, and respond to overwhelm in ways that support both individual well-being and organizational effectiveness.

Finally, by exploring the contextual understanding of employees' first-hand experiences in workplace settings, we offer practical insights for identifying and addressing this difficult experience in oneself and in others. These insights can help employees, managers, and organizations develop early interventions to curb or prevent downstream negative consequences. Together, these contributions advance theoretical understanding while offering practical implications for researchers, managers, and organizations aiming to foster healthier, more sustainable workplaces.

Toward an understanding of the state of being overwhelmed

Recent surveys show that 35 to 40% of employees report feeling overwhelmed (Deloitte Insights, 2022), illustrating this experience as a defining feature of modern work life. Yet despite its prevalence, the concept of overwhelm remains surprisingly underexamined and ill-defined. Overwhelm is often listed among other stress-related states—such as anxiety, tension, worry, and anger (Rafaeli et al., 2009; Spector and Goh, 2001)—and has only recently emerged as a distinct affective experience. For example, in a large-scale mapping of emotion dimensions, Fontaine et al. (2022) recently identified “overwhelmed” as one of 80 unique affective terms. However, unlike more established constructs, little theoretical or empirical work has surfaced what this state signifies, how it is subjectively experienced, and thus what consequences it carries for individuals and organizations.

Conceptually, overwhelm is closely tied to the stress process. A small number of studies have linked overwhelm to occupational stress, mostly in healthcare settings (e.g., van der Kolk et al., 1996). For example, Hunziker et al. (2011) reported that medical emergency students' feelings of being overwhelmed correlated strongly (r = 0.68, −0.75) with perceived stress, more than any of the other 18 emotions measured. This combination of overwhelm and stress, termed “stress overload”, significantly predicted resuscitation performance. Similarly, Andresen et al. (2018) framed overwhelm as a stress reaction to new and/or intense environmental social stimuli, leading to withdrawal coping (i.e., increased turnover intention). These studies demonstrate that being overwhelmed is consequential, yet they offer limited insight into how it actually arises, how it is interpreted in situ, or how it unfolds in everyday organizational contexts.

This lack of contextualization represents a critical gap in our understanding of overwhelm. As prior research has emphasized, how individuals appraise and make sense of stressors is central to understanding the stress response and its downstream effects (Dewe, 1992; Horan et al., 2020; Mazzola et al., 2011). This appraisal process lies at the heart transactional theory of stress (Lazarus and Folkman, 1984), which defines stress as an adaptive response to a perceived imbalance between situational demands and personal coping resources. This cognitive appraisal approach has become foundational across a wide body of stress research, and it underpins major organizational theories of strain and burnout. Building upon this framework, JD-R theory (Bakker and Demerouti, 2007; Demerouti et al., 2001) proposes that job strain arises when job demands—such as workload, emotional labor, or time pressure—repeatedly outweigh available resources like autonomy, social support, or feedback. Similarly, the COR model suggests that burnout is a result of persistent threats to available resources (Hobfoll and Freedy, 1993). Together, these theories underscore the importance of the balance between perceived situational demands to perceived available resources, which can drive the negative downstream consequences the individual will experience at work.

We argue that the experience of being overwhelmed represents a critical, yet overlooked, inflection point in the stress process. It is the moment when the perceived balance between demands and resources shifts from manageable to unmanageable—when individuals move from coping to no longer coping. Understanding this transition is vital not only for advancing theory but also for informing early interventions that prevent downstream harm. Our research thus focuses on employee's lived experience of being overwhelmed, guided by two key questions. First, how do employees make sense of the experience of being overwhelmed (RQ 1)? Second, what are the subjective consequences that employees associate with their experience of being overwhelmed (RQ 2)? Together, these questions aim to deepen our understanding of this critical yet underexplored phenomenon.

Method

Participants and data collection

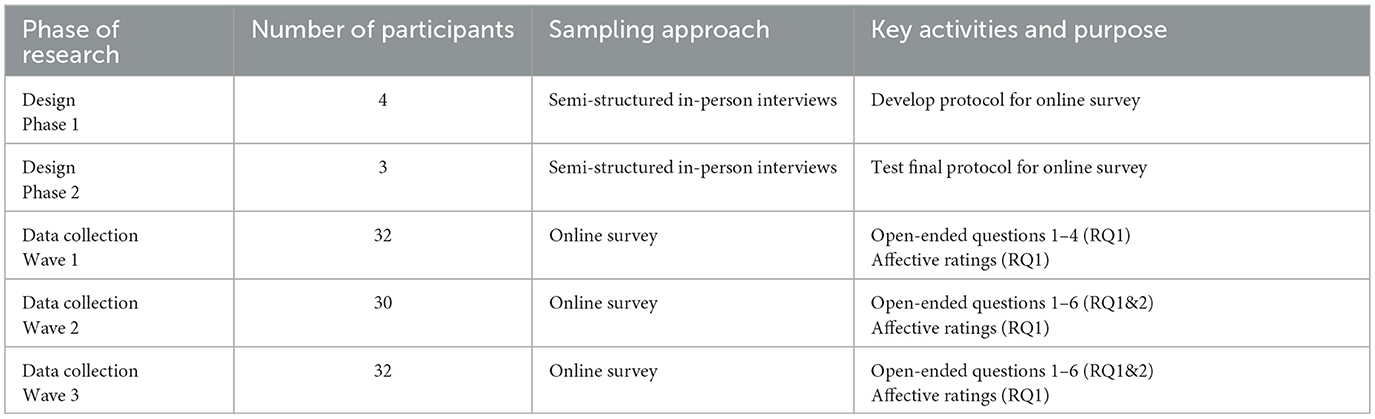

In preparation for data collection, we first conducted 7 exploratory semi-structured interviews with individuals from the authors' network who suggested they had recently experienced being overwhelmed at work. These interviews helped us to develop and refine our final structured interview protocol to be used in our main online study. Before launching the main study online, we conducted 3 more in-person interviews using our finalized protocol, and these were transcribed and included in our final data set. Then, we launched our main study using the online platform Prolific. We recruited an additional 91 participants, each compensated 4£, resulting in a final sample of 94 employees (47 female, 46 male, one non-binary), with an average age of 35 years old (range: 20–65). Most participants were employed (82 paid employees, 9 self-employed, 3 unspecified), spanning industries such as marketing, education, IT, finance, and administration. All participant data were collected upon informed consent and in a manner consistent with the Declaration of Helsinki's ethical standards for the treatment of human subjects.

Our qualitative data consists of written narratives in response to a series of open-ended questions, similar to the Stress Incident Record approach (Mazzola et al., 2011). We asked participants (1) what “being overwhelmed” means to them, (2) to describe a significant past situation in which they felt overwhelmed, (3) what kind of thoughts and feelings they had, and (4) how they responded in that situation.

After participants provided their narrative response to these open-ended questions, we asked them to rate how often they experienced being overwhelmed in the last month on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (never) to 5 (very often) and how intense those experiences were, from 1 (very weak) to 5 (very strong) with the option “non applicable”. We then asked participants to reflect on a list of 23 affective terms and select those that best describe their experience of being overwhelmed using a 6-point Likert scale from 0 (did not experience the feeling) to 5 (experienced the feeling with very strong intensity). These included 12 negative feelings (anger, frustration, disgust, fear, anxiety, anguish, distress, disappointment, shame, regret, guilt, sadness) and 11 positive feelings (interest, amusement, pride, joy, pleasure, contentment, love, awe, admiration, relief, compassion) taken from the organizational and emotion literature (Fontaine et al., 2013; Lazarus and Cohen-Charash, 2001; Perrewé and Zellars, 1999).

We completed sampling in three waves of approximately 30 participants each, within two months (see data collection overview in Table 1). Based on our exploration of the first data wave (N = 32), we probed participants in the second and third wave (N = 62) to report more specifically on the consequences of being overwhelmed in their work context (to better address RQ 2). Thus, in addition to the open-ended questions from the first data wave (1–4 listed above), participants answered two additional open-ended questions: (5) how being overwhelmed impacted their work (e.g., performance, relationships, attitudes and feelings, and (6) how their workplace did—or did not- help them handle their experience.

Data analysis

To inductively explore the experience of being overwhelmed, we conducted thematic analysis of the qualitative data using an iterative coding process (Braun and Clarke, 2006). In addition, we complemented our qualitative findings by aggregating participants' self-ratings of feelings they associated with their described narratives of being overwhelmed. The analysis progressed in several phases. In the initial phase, the first and second author read the transcripts and used both closed (theoretical) and open (substantive) coding approaches (Locke, 2001). That is, the authors coded the transcripts according to the emerging descriptions offered by the individual (open codes), as well as with known concepts that were explicitly mentioned from established theoretical frameworks and labels known to the authors across the emotion, stress, and coping literatures (closed codes). For example, we labeled reported coping styles (e.g., resource seeking) according to existing concepts (adopted from Carver et al., 1989; Garnefski and Kraaij, 2007; Lazarus and Folkman, 1984). The third author independently coded a subset of narratives to provide an external perspective on the emerging coding scheme. We organized our codes according to our research questions surrounding the antecedent context and experience of being overwhelmed (RQ1) as well as its consequences (RQ2).

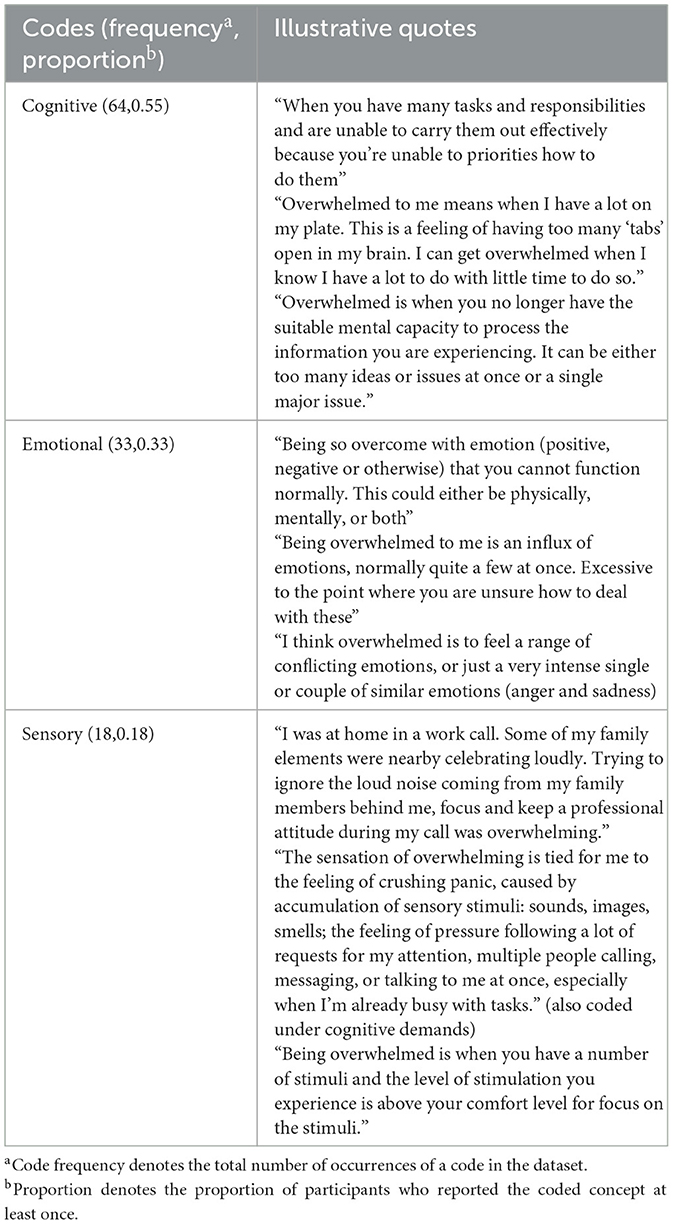

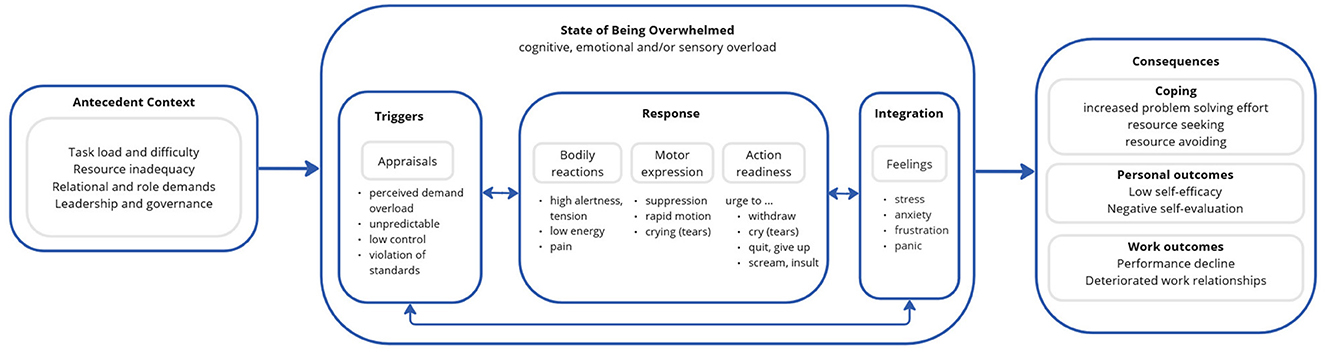

In the second phase of our analysis, we grouped similar or conceptually related codes into broader categories and themes. We refined categories based on their frequency, conceptual clarity, and distinctiveness. For example, related to the category of the “mental demands” giving rise to overwhelm, we identified the themes of cognitive, emotional, or sensory demands (see Table 2). To enrich and structure our themes, we also incorporated insights from existing literature. For example, we drew on the componential model of emotion, which suggests that affective states (such as overwhelm) involve five components (see Moors et al., 2013; Scherer, 2005; Scherer and Moors, 2019). These are (1) the appraisal of events (subjective evaluation of their relevance and implications for one's goals or needs), which trigger the affective response including (2) bodily reactions (physiological changes in the body such as changes in respiration, heart rate, muscle tone, etc.), (3) motor expressions (in face, voice, and gesture/posture) and (4) action readiness (motivations or preparations for actions for dealing with or adapting to the event, such as turning away, screaming, crying, etc.). These are consciously represented and integrated as (5) feelings (labeling the experience as feeling stressed, frustrated, etc.). We used these five components to organize our themes and comprehensively describe the affective state of being overwhelmed (see Figure 1). Through these stages, the full team met regularly to compare, contrast and complement codes and generate categories and themes.

In our final stage of analysis, we integrated findings from RQ1 and RQ2: We refined our definition of being overwhelmed and the core process of interrelated changes in its five components, and situate the experience of being overwhelmed within the larger dynamic framework of antecedent contextual factors and consequences (represented in Figure 1). In doing so, we iteratively danced between the theory informing our understanding, and our emergent codes, categories, and themes. During this final phase, we also integrated our survey data. We conducted descriptive analytics (frequency and intensity of the experience and associated feelings) complement our findings about the feeling component of overwhelm.

Findings

Research question 1: the experience of being overwhelmed

Integrating prior literature with our analysis below, we define being overwhelmed as a distinct affective state occurring at the perceived tipping point when situational demands are appraised as exceeding available resources, and is marked by heightened alertness yet bodily fatigue, limited outward expression, withdrawal or mental freeze, and the conscious experience of predominantly negative feelings. Below we unpack the experience of being overwhelmed, commencing with its antecedent context, followed by the core experience of being overwhelmed. While the antecedent conditions describe the situational context and stressors that precede the experience of being overwhelmed, the triggers or specific event appraisals that catalyze the perceived tipping point into overwhelm constitute a core component of the experience of being overwhelmed (see Scherer and Moors, 2019).

The antecedent context of being overwhelmed

In our sample of 94 participant narratives, most participants (60%) experienced being overwhelmed in the context of workplace relationships (e.g., with the manager, or colleagues) and/or in relation to general workplace factors (e.g., governance and fairness). A notable 35% of participants pointed only to their manager, and 21% of participants to both their manager and general workplace conditions. 40% of participants experienced being overwhelmed in the non-work environment and attributed it to family members or friends (partner, child, parents, friends).

Many situational factors seemed to give rise to overwhelm such as high task load or difficulty, low job autonomy, pressure from key stakeholders (e.g., manager/supervisor, clients), organizational politics, role and interpersonal conflict, resource inadequacy such as understaffing (systematic or due to sick colleagues), and finally, covid-related factors (uncertainties, restrictions such as working remotely).

To contextualize the appraisal component of overwhelm, we found that participants experienced being overwhelmed in response to role overload: situations in which work demands are high and resource availability is low, or when individuals take on more tasks and are motivated to perform them well (Kahn and Quinn, 1970). For example:

‘It was a particularly busy shift and I was trying to direct my team to maximise the amount of work that could be completed. Unfortunately it meant that we would inevitably be late off. Trying to manage this demand as well as get my team off as close to their finish time as possible whilst having the background stress of feeling under prepared resulted in feeling overwhelmed.'

In addition to work-related role demands, work-family conflict and family-related role demands also contributed to overwhelm. In addition, participants also described being overwhelmed in reaction to role changes or transitions both at work and in relation to family life: starting a new job, promotion with managerial responsibilities, starting a family, dealing with the death of a close person, and couple separation.

The core experience of being overwhelmed

In summary, being overwhelmed is triggered by appraisals of demand-to-resource overload, manifested in bodily reactions by both fatigue and a heightened state of alertness. While there are no clear motor expressive patterns related to being overwhelmed, there is an underlying readiness for avoidance or inaction. These bodily and mental changes are subjectively represented using different affective labels that refer to negative stress- and fear-related feelings. Below we detail the experience of being overwhelmed along these five components of affective experiences (see Moors et al., 2013; Scherer, 2005; Scherer and Moors, 2019); starting with its triggering appraisals, followed by affective responses in terms of bodily reactions, motor expressions, action readiness, and finally their integration and labeling as feelings (as summarized in Figure 1).

Triggering appraisals

The analysis of eliciting appraisals underlying experiences of being overwhelmed revealed that individuals perceived an overload of unpredictable or unreasonable demands that were either or both cognitive, emotional, or more sensory in nature (see Table 2 for examples), as well as a lack of coping resources and abilities. The combination of perceived heightened demands with low, depleted, or inaccessible resources contribute to the experience of hitting a “tipping point” characterized by the inability to further control or cope. Several participants literally referred to a well demarcated point in their experience that elicited overwhelm, illustrated by two examples here (italicization added by the researchers):

‘I was moving into a new apartment… My parents had just helped me move my stuff and we were waiting for the wifi installer to show up. … The wifi company not honouring their appointment was the tipping point on a lot of stress I was already holding onto and it led to me feeling overwhelmed.'

‘No matter how hard I was trying, the number of emails in my inbox kept going up and up. It got to a point where I could not deal with the increased amount of emails coming in minute by minute. … Eventually I lost the train of thought … This caused anxiety to the effect that I was incapable of doing anything at all.'

A first recurring appraisal of the demand or stressor is that it was perceived as unpredictable, while still often described as familiar (regular tasks at work or home). For example, a plethora of e-mails, client requests or task assignments delegated by one's supervisor is commonplace at work, but can be overwhelming when requests all arrive at once or unexpectedly. One participant described, “You don't know how long it is going to last and what else is coming your way. Feels like a fast-paced game of coping for unknown duration”. Other demands were perceived as unfamiliar or rare, like important life events such as taking on a new role, writing a thesis, planning for marriage, starting a family, couple separation, or dealing with the death of a loved one.

Second, 28% of participants (26 participants out of 94) described demands with an important yet unpredictable future outcome. For example, participants described being overwhelmed with uncertainty statements like, “I feel vulnerable, like something bad could happen any moment”, “To me it's a feeling of helplessness and not knowing what the outcome of a situation will be. Being constantly worried about the outcome of a situation and not having any control over the outcome”. Examples of such situations were thoughts of negative work-related consequences like delivering work on time, having negative performance or client ratings, or being laid off, or uncertainty about a personal situation like ill-health or death of a family member.

Third, 34% of our sample suggested that experiences of being overwhelmed have a normative significance—that is, they contained value judgments of self or others that heightened the situation's perceived demands. This surfaced as individuals' beliefs that (a) they were violating or failing to meet their own internal standards (e.g., regarding professionalism, productivity, output quality, or even morality and values), (b) they were violating or failing to meet external standards, or (c) that others had violated expectations or fairness standards.

For example, some had strongly internalized moral beliefs and standards of how they should be able to cope with life and work demands, because “it's my job”, “I'm the manager”, or because of “being male and having to provide for my family”. Several participants (20%) associated overwhelm with a perceived failure to live up to external expectations (e.g., from their manager, co-workers, parents, partners), for example surrounding responsibilities and pressure to achieve in a certain role, which often entailed a high workload (e.g., “At this time I was in a role that was more fast-paced and results-based than the norm, so there was an underlying degree of pressure at all times.”). The perception that others violated norms like respect of one's time in appointments or recognition of one's work or identity also played a role. One participant describes, “I felt that the customer did not respect my knowledge and how I was pushing myself daily to help every customer”.

Fourth, the gradual or sudden loss of control (the ability to change the demand or one's reaction to it) and power to exert control was strongly associated with the experience of being overwhelmed. Thirty-three percent of participants explicitly reported having a lack of control or power (e.g., job autonomy, task management, keeping composure toward clients). As one person mentioned, “being overwhelmed is the first degree of loss of control.” This example highlights the process of losing control and reaching the tipping point we describe above:

‘I cannot control the external circumstances that put me under pressure, but I can still control the way I express the tension. I still feel that for the time being I can behave in the way I think I should. But internally I cannot regulate the internal tension, the sense of lack of control. I feel vulnerable, like something bad could happen any moment. If it gets a little bit harder I'm not going to be able to cope anymore'

One out of five participants (20%) described overwhelm in terms of an accumulation of events rather than one single event, or depicted how a single event adds up against the backdrop of an already taxed mind from work or life challenges. While initially the demands are perceived as manageable, overwhelm seems to connote a perception switch where they seem no longer surmountable. As witnessed by this participant:

‘I was in the early stages of a new job. It was already something that was a little out of my comfort zone but I was coping. I was mostly dealing with clients on a one to one basis and this was relatively comfortable for me. A couple of weeks into the job I faced several clients at once. Everything I said to each of them was not having the desired effect and with each passing moment I was becoming more and more frustrated. This frustration snowballed and in turn affected my abilities to try to gain any sense on control of the situation.'

Finally, a felt lack of resources to handle the demands led to overwhelm, such as insufficient time, energy, or manpower (social support). One participant describes: “you feel you can't cope anymore. You feel like all your resources are drained and you honestly don't know how to react, respond, or what to do next”. A sense of a lack of time is most pervasive in overwhelm: one third of participants (31%) described there being too little time to complete task(s), such as “having to do everything at once”, or “having a high workload and a short deadline”. Insufficient manpower or social support as a resource was due to short staff, unsupportive colleagues, unavailable partner or family. A third of our participants (35%) explicitly referred to already having a lack of, or highly depleted resources at the time of the overwhelming event.

Affective responses

The above-described appraisals accompanied a myriad of affective responses. First, bodily reactions were highly salient in the experience of being overwhelmed for the majority of participants (59%, i.e. 55 out of 94). Participants commonly mentioned fatigue and general reduced energy (e.g., weak limbs) yet also reported heightened internal alertness preventing them to rest. Examples of physical symptoms were muscle tension, heartbeat acceleration and palpitations, difficulty breathing (rapid and shallow), flushing of the face, transpiration, upset stomach, pain or pressure on the chest and body, and headache. These symptoms point to a heightened state of alertness that physically exhausts the body yet prevents the body to sleep, rest, eat or digest.

Second, compared to a strong activation of the somatic nervous system according to above described bodily reactions, participants gave relatively little descriptions on how they outwardly expressed their state. Crying was about the only overt expression of overwhelm reported in our dataset. Narratives indicate that participants generally chose to suppress the expression of being overwhelmed, for example: “I put on a brave face”, “I would just shove it down so I could get my work done”, “I probably don't express it in a particular way, though, just a loud sigh, rolling of eyes maybe, but not more. It stays pretty much inside”, or “I was calm and collected on the outside but my internal body ached with pain because of the loss. But externally I remained calm as other people needed me to support and help them”, “I didn't really express being overwhelmed as my workplace is public and I had to motivate the team I was supervising to work but also talk to customers and help with their problems.”

Third, in contrast to the apparent absence or suppression of expression, almost half of all participants (45%, i.e. 42 out of 94) mentioned at least once an action readiness i.e. urge or motivation to express, act or behave in a certain way. Participants said they wanted to cry, run away, stop, give up, shut down, be (left) alone, hide away, go to sleep. For example: “It very nearly got to the point of me canceling the whole wedding as I didn't feel it was worth the stress I was being caused”. Yet, the action readiness to freeze—to disengage from the environment—was as recurrently associated with overwhelm. For example, one participant wrote: “My mind went blank … and then I stood there behind the counter, wondering what to do, or what button to press to correct my mistake”. Another participant describes: “… being overwhelmed is a mental and physical state of complete inability to move forward”.

This mental freezing response generalized as not wanting to do anything, including eating or sleeping, and was manifested in difficulty managing tasks effectively, as a fifth of our participants (20%) reported being unable to prioritize tasks, or even get started during experiences of being overwhelmed. They describe: “Overwhelmed is when there are many to-dos swirling above your head and you don't know yet where to start”. This dynamic is illustrated by participants' descriptions of overflowing email inboxes:

‘I am trying to clear these emails while more emails are coming every few minutes. No matter how hard I was trying, the number of emails in my inbox kept going up and up.... Eventually I lost the trains of thought on the several email conversations going on and I was at the time incapable to working out what to deal with next. This caused anxiety to the effect that I was incapable of doing anything at all.'

Feelings

The above-described changes in appraisals and responses are represented and integrated as feelings that individuals associate with their affective experience. The open-ended responses revealed that the majority of (83%) of participants (N = 94) labeled their experience of being overwhelmed as negative. A small proportion of participants (12%) did not specify negative or positive, and 5% of participants said they sometimes feel positively overwhelmed in response to important personal life events such as a birthday surprise, the birth of a child, and marriage proposal, using the terms happiness and love. Instead, most participants reported feeling accompanying stress (with 45% of participants mentioning this), as well as anxiety (30%), panic (22%), worry (19%), or frustration/anger (30%), often in combination. For example:

‘Anxiety, distress, feeling bad, anguished. There is also a component of anger. The obvious type of anger is frustration: anger where you can't do anything about what's going on. I also tend to blame others and mentally tell them not to do this to me (sometimes irrational)'

19% of the participants narrated other feelings such as grief or sadness (also using words such as helpless, lonely, depressed) over a sick or lost close relative or a difficult work situation, and guilt or shame over a mistake or certain behavior. Notably, there were no positive depictions of being overwhelmed at to the workplace.

To complement these participant narratives, the Likert-scale rating pattern showed that overwhelm is a frequent experience with moderate or strong intensity. The average frequency in the last 30 days is 2.97 on a scale from 1 (never) to 5 (very often). 89% of participants experienced being overwhelmed in the last 30 days and rated this experience as moderately or highly intense (average of 3.14 on a scale from 1 (very weak) to 5 (very strong). From the 23 affective terms provided, participants associated being overwhelmed with moderate to strong feelings of frustration (93% of all participants), anxiety (88%), or distress (81%). Interest, pride, love, and/or compassion were associated with overwhelm with mild to moderate intensity by at least half of the participant sample. Thus, taking the open-ended responses and affective ratings together, the subjective feeling of being overwhelmed cannot be reduced to just “high stress”, though it was the most used affective term and was an enduring background state when overwhelm was felt. For example, one person said:

‘I remember speaking with my girlfriend…usually I'm pretty good at handling conversations over the phone but the tiniest asks and demands seemed overwhelming (she was asking me things like when I was next coming round, but because I was so tired and stressed, I didn't know and couldn't answer). Then when she got upset at the situation, I just couldn't handle it and couldn't react in an appropriate way'.

In a similar context of existing stress, participants also used the term “panic” to describe a sudden and heightened level of distress. For example:

‘Being overwhelmed comes on as a physical and mental panic. My breathing gets shallow and fast, I have all sorts of pent-up energy in my body driving the feeling of ‘I have to do something, right now' while at the same time, my brain is unable to hold on to a single thought before flitting to the next.'

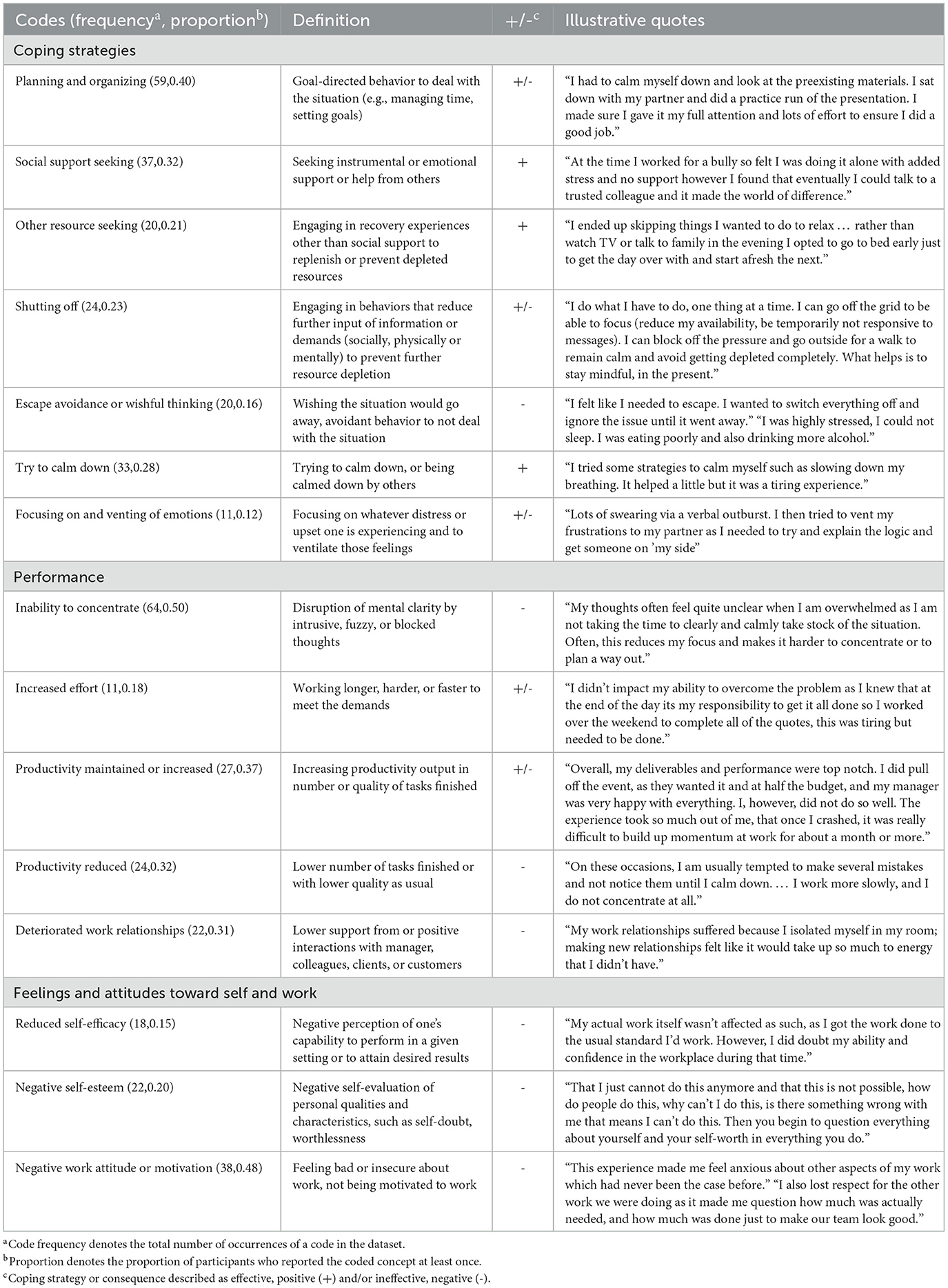

Research question 2: consequences of being overwhelmed

Participants also described the most meaningful coping strategies and other consequences that they believed stemmed from their experience of being overwhelmed. Where possible, we also coded for whether the respondents believed these strategies were effective (or ineffective). We organize our findings with respect to the recurring coping strategies (problem solving and resource seeking) as well as most commonly noted consequences (performance, and feelings and attitudes toward work and the self). We refer to Table 3 for details and examples for each consequence. Figure 1 illustrates the larger conceptual framework within which these consequences are embedded and integrated with findings from RQ1.

Coping strategies

Problem solving

People invested significant effort to attempt to regain control over the situation by planning and organizing their tasks through managing time, setting goals, thinking about what steps to take to handle the overwhelming events, and other goal-directed behavior to help cope with their overwhelm. In an example of successful coping, one manager said “I assessed what resources I had at hand and asked each of my team if they had any welfare issues should they be late. I then released those who had to return home to finish work and for those who were happy to stay. I did have a feeling of dread asking my team to stay on but talking it through with them helped alleviate this”.

Yet, less than half of the participants said their problem-solving effort helped. Problem-solving coping strategies were mostly insufficient or unsustainable. Several reported staying late or doing over hours to finish the task in time, e.g. “I wanted to go home and go to sleep, but I carried on and powered through at work. It made me feel better to get bits ticked off my to do list instead of hide away and wallow like I wanted to”. However, the demands were sometimes so high that increased efforts (to work longer, faster, focus on the most urgent or important tasks) were insufficient. For example, one participant described “I would do the quicker things first then ran out of time for the longer tasks”. This effort often comes at the cost of exhaustion: “I tried my best to combine everything, often multi-tasking as much as possible. I was constantly exhausted and recall crying myself to sleep one night”.

Despite the numerous reports of physical and mental fatigue and even exhaustion, participants who focused on problem-solving rarely engaged in recovery experiences to regain their mental and physical resources to tackle the demands, compounding the experience. For example, this participant reports having trouble detaching from work: “I felt quite emotionally drained. I found myself constantly thinking about the tasks and issues that I have on hand, even when I was not at work”. Or, “...rather than get up from your desk (for a walk, lunch or a cup of tea...a break, basically) you stay seated working away, which also increases the feeling of frustration and irritability”.

Resource seeking or avoiding

The most common coping strategy used was various forms of resource building, such as social support (e.g., asking the manager for help), or engaging in recovery activities such as resting or sleeping, journaling, seeking out nature, physical exercise, or meditation. 50% of participants in our sample (47 out of 94) reported engaging in one of these types of resource seeking activities. For example, this participant said “My husband helped enormously, we were like a tag team, one would rest when the other looked after the children.. as the days and weeks went on, and a good routine was in place, things settled and life became very joyful”.

However, the opposite to resource seeking was also true, as other participants attempted to cope by shutting off from others and their environment. The inability to act and shutting off were signature behaviors of mental freezing and avoidance motivation that characterized the overwhelm experience in the first place. Participants reported “feeling trapped”, “I thought I had no way out … I did not know what to change to get out of this situation”, “freezing in my thoughts and I wished that someone could get me out”.

A notable exception to problem-solving or resource-seeking efforts was the use of escape avoidance and disengagement strategies. One participant said for example “I do remember giving serious though as to whether I could give myself a minor injury to be able to postpone taking exams. What an idiot I was”. Another participant described resolving to several forms of mental and behavioral disengagement:

‘Frequent periods of not thinking of things in particular. Not being able to talk about situation, the desire to remove myself from my everyday life. I felt I had to drastically change my own situation soon after so I left my job, probably drank too much, didn't socialise as I had been doing. I had no energy or patience for anything that I had done previously either work wise or in personal life. It also coincided with a relationship break up which didn't help either!'

Perceived consequences

Performance decline

50% of participants (47 out of 94) mentioned that being overwhelmed prevented them from focusing or concentrating, either as an immediate response to the demand or stressor or as an enduring disruption of mental clarity. They described the inability to concentrate on the job at hand because competing priorities interrupted their thoughts, because they were exhausted, because they were preoccupied about the demands or stressor and potential consequences, or because their thoughts were simply stuck or frozen. In response to the question of how overwhelm impacted their work (N = 62), participants were divided: they either increased or maintained their productivity (37%) or were unable to do so and thus faced reduced productivity in the number of tasks done or the quality of performance (32%). The following excerpt provides a potential explanation of this productivity ambiguity distinguishing between short vs. long-term impact:

“Overall, my deliverables and performance were top notch. I did pull off the event, as they wanted it and at half the budget, and my manager was very happy with everything. I, however, did not do so well. The experience took so much out of me, that once I crashed, it was really difficult to build up momentum at work for about a month or more. My performance definitely suffered post the overwhelming experience, if not during it.”

Several participants also highlighted deteriorated work relationships as a consequence of being overwhelmed. For example, “It soured the relationship with my manager—they seemed to then view me as an underperformer as opposed to someone who was overworked and given unclear instructions”. Participants related relationship deterioration to themselves becoming more irritable or in a bad mood, or to investing less time in others:

“My colleagues were certainly apprehensive toward my approach, judging me for being stern and harsh toward them, as well as the customers. I was left feeling unsupported by my manager, who didn't turn to communicate with me about the [overwhelming] situation straightaway”.

Negative feelings and attitudes toward self and work

Many participants described negative changes in beliefs about what one is able or should be expected to do as a consequence of being overwhelmed. They report reduced self-efficacy or generalized negative self-evaluations (low self-esteem). These include self-doubt and thoughts of worthlessness, not being clever or good enough, being useless, looking weird, like an idiot, like a failure. The adjustment of beliefs related to the appraisal of expectancy violation described above (under the appraisal component of overwhelm). For example:

‘I'm supposed to be able to do it, I'm paid for it, people expect it from me, so fucking do it. But it feels like it's hard and too much. I start thinking whether I am incompetent, or just temporarily handicapped somehow, or this is just life. Do I need to get better? I don't know. I reflect whether this is normal. Maybe I'm not good enough, or maybe it's circumstantial, Like, I'm good enough but at the moment I am not able to cope, or maybe this is not normal, this is not how I am supposed to live, and there is really something wrong that needs to change.'

In response to the question how being overwhelmed impacted their feelings and attitudes toward work (N = 62), almost half of the participants (48%) reported feeling bad or insecure about one's work, or not being motivated to work, compared to only 13% of participants saying they felt good or neutral about work as a consequence of being overwhelmed.

Discussion

This study investigates the phenomenon of being overwhelmed, an ill-defined yet debilitating experience in modern workplaces. From an inductive exploration of first-person narratives and ratings of employees' experience of being overwhelmed, we define the experience as distinct affective state occurring at the perceived tipping point when situational demands are appraised as exceeding available resources, and is marked by heightened alertness yet bodily fatigue, limited outward expression, withdrawal or mental freeze, and the conscious experience of predominantly negative feelings.

In our sample we find that 60% of overwhelm experiences originate in the workplace—driven by role demands and overload, role conflict and changes, and managerial behaviors—while 40% stem from personal life circumstances. This distribution may not be generalizable, but it suggests that both domains may contribute meaningfully to the overwhelm experience. Overwhelmed individuals, unable to recover, experience pervasive negative consequences over time, including negative feelings and attitude about work and life, negative self-beliefs, deteriorated social relationships, attentional deficits, and performance decline. Here, coping efforts of action-oriented problem solving such as working harder and longer are mostly insufficient or unsustainable. Those that use prolonged problem-solving coping often report refraining from engaging in recovery and avoided connecting with others, leading to further exhaustion and isolation. However, building resources, particularly through social support, emerged as an effective coping mechanism.

In summary, we illuminate a critical and preventable phenomenon with significant negative implications for employees and organizations. By formally defining and exploring the state of being overwhelmed, we respond to calls for deeper insight into the subjective and affective underpinnings of stress (Lazarus, 2006; Lazarus and Cohen-Charash, 2001; Mazzola et al., 2011; Perrewé and Zellars, 1999), while integrating and contributing to the emotions, stress and coping, and management literature.

Theoretical implications and contributions

First, our research makes a significant theoretical contribution to the emotion literature by establishing “being overwhelmed” as a distinct affective state composed of a structured set of appraisals, bodily reactions, expressions, action readiness, and feelings. While emotional taxonomies recently listed being overwhelmed within the broad affective space (Fontaine et al., 2022), the concept has not been formally defined nor empirically studied unlike other stress-related emotions such as anxiety, frustration, or guilt (Perrewé and Zellars, 1999; Rafaeli et al., 2009; Spector and Goh, 2001). Building upon this fundamental groundwork in emotion research (Scherer and Moors, 2019), our work provides an empirically grounded and contextually embedded conceptualization of being overwhelmed, detailing its constituent components, antecedents, and consequences. In doing so, we foster systematic research on being overwhelmed as it can now be mapped onto existing emotion models, facilitating a parsimonious understanding of its underlying affective processes that ultimately drive coping behaviors, performance and health outcomes (Christensen and Aldao, 2015; Lazarus, 2006; Perrewé and Zellars, 1999; Spector and Goh, 2001).

The integration of a componential emotion framework also facilitates differentiation with other states (Scherer and Moors, 2019). For example, being overwhelmed is characterized by specific appraisals such as unpredictability, loss of control, high normative significance, and lack of resources, typical of stress-related states (Perrewé and Zellars, 1999; Spector and Goh, 2001; Semmer et al., 2019; Troup and Dewe, 2002). However, being overwhelmed was additionally and distinctly characterized by a misalignment across affective components: intense and predominantly negative feelings with an absence of corresponding motor expression, disorganized or insufficient resource allocation reflected in mental freezing (inaction, withdrawal), and the simultaneous experience of fatigue and heightened alertness. While Fontaine et al. (2022) placed being overwhelmed in the high arousal, low power, and negative valence quadrant along with anxiety, distress and panic, our findings indicate that being overwhelmed is an unstable and desynchronized state alternating between high arousal (e.g., panic, anxiety, frustration) and low arousal states associated with depletion (e.g., fatigue, sadness). This inner conflict of tension positions the concept of being overwhelmed as distinct from other negative stress-related concepts (anxiety, distress, worry). Thus, our findings suggest that being overwhelmed does not occupy a fixed position on a dimensional framework of affect, but should be conceptualized as a transitory affective state that emerges at the inflection point where the tension between perceived demands and resources reaches a subjective peak of tolerability.

Second, our work contributes to the stress and coping literature. Within the framework of transactional theory of stress (Lazarus and Folkman, 1984; Hobfoll, 1989; Hobfoll et al., 2018), inadequate or disorganized resource mobilization, reflected in several components of overwhelm as shown above, characterizes the onset of a threat state. This state arises at the critical moment where individuals appraise their resources as insufficient to meet situational demands, threatening personal goals essential to their well-being. Thus, from our qualitative analyses emerged a conceptualization of being overwhelmed that is fundamentally related to concept of threat, providing a first and an in-depth account of the subjective-affective underpinnings of threat (Blascovich and Mendes, 2000; Lazarus and Folkman, 1984; Meijen et al., 2020; Tomaka et al., 1993). Our work thus contributes to a comprehensive understanding of threat, outlining the different components of the affective state that triggers the onset of threat.

Our findings also shed light on how employees choose coping strategies to navigate the consequences of being overwhelmed. While variance-based methods show mixed results of the efficacy of emotion-focused coping (Demerouti, 2015; Semmer and Meier, 2009), our qualitative approach reveals that individuals often use indirect, emotion-focused strategies, such as avoidance or distraction, to manage uncontrollable demands and achieve temporary relief. When demands are heavy, prolonged, uncontrollable or occur when the individual has depleted resources, problem-solving strategies (e.g., working longer and harder) become maladaptive as they further deplete resources and hinder recovery. This underscores Lazarus (2000) original claim and subsequent scholarship (Demerouti, 2015) that different strategies supplement each other in the overall coping process.

Third, the focus on employees' experiences of being overwhelmed at work adds to the organizational and management literature. Although the term “being overwhelmed” is widely used in professional discourse, it has not been rigorously examined from an empirical or theoretical standpoint. However, the core appraisal characterizing overwhelm as an affective response to demand-to-resource overload highlights a critical and specific aspect in workplace theories of stress, such as the Job Demands-Resources theory (Bakker and Demerouti, 2007; Demerouti et al., 2001) and the Conservation of Resources theory (COR, Hobfoll and Freedy, 1993). These theories hold that the balance of perceived situational demands relative to available resources is a crucial because it influences the negative consequences for both individuals and organizations (Demerouti et al., 2021; Fugate et al., 2012; Ganster and Rosen, 2013).

Our conceptualization of overwhelm as an affective state triggered by distinct appraisals aligns with core tenets of Conservation of Resources (COR) theory (Hobfoll, 2011; Hobfoll et al., 2018). First, resource loss is a dominant force in the human stress response according to COR theory. In line with this, participant narratives revealed that overwhelm typically occurs when individuals perceive an imminent or accumulating loss of resources—such as time, autonomy, energy, or social support—under mounting cognitive, emotional, or sensory demands. Moreover, many participants described reaching a critical “tipping point” after which their coping strategies failed, marking a breakdown in the efficacy of resource investment. Although some attempted to mitigate overwhelm through problem-solving or resource-seeking efforts (e.g., planning, engaging emotional support), these efforts were frequently experienced as insufficient or unsustainable. This fits COR's second principle that resource investment is necessary to recover or protect against further loss, but is limited by the individual's existing resource reservoir. Individuals already operating with depleted resources appeared especially vulnerable to further resource loss– dynamic declines or self-reinforcing cycles of further depletion that COR theory identifies as downward resource loss cycles (for an in-depth and critical review of resource gain and loss cycles, see Sonnentag and Meier, 2024). Our findings offer a contextualized and phenomenologically grounded understanding of this dynamic balance between demands and resources as theorized by COR, capturing how individuals transition toward an imbalanced, resource-depleting state of overwhelm.

Second, our findings illustrate that overwhelm is shaped not only by individual perception, but also by shared, objective environmental conditions, such as managerial support, workload predictability, and fairness. These align with COR's concept of resource caravan passageways—the ecological conditions that enable (or hinder) access to and protection of resources (Hobfoll, 2011; Hobfoll et al., 2018). Organizations lacking such supportive working conditions may see more employees experience being overwhelmed, especially those with limited personal resources. By highlighting how the absence of resource passageways can lead to overwhelm even for individuals with relatively high personal resources (e.g., energy in maintaining performance), our findings reinforce and elaborate the ecological emphasis within COR theory.

Importantly, the COR principle of resource investment to protect against resource loss and the associated dynamics of loss and gain cycles parallel the subjective threshold perceptions that employees describe when being overwhelmed. This tipping point in the perceived balance between demands and resources often precipitated cascading negative effects. This helps explain why individuals may transition from focused coping with demands to overall mental freezing, withdrawal or disengagement—from work demands but also from restorative resources such as resting and social support. Conversely, early detection of resource depletion and timely resource gain may help individuals maintain energy to sustain coping capacity and initiate gain cycles (e.g., problem-solving, social support seeking). In this way, overwhelm can be understood as a critical inflection point between resource preservation and breakdown, emphasizing the need for both individual strategies and resource sustaining work environments in preventing full resource depletion. This elaborates COR theory's conceptualization of resource spirals by showing that the transition into a loss or gain cycle may occur at a subjectively appraised inflection point—one that is highly sensitive to the individual's current resource levels.

In sum, our study advances theory in organizational psychology by clarifying how employees perceive and manage demands and resources in the context of the contemporary workplace. We find that employees' experiences of being overwhelmed are distinctly tied to a fast-paced and volatile work environment where persistent work and personal demands from multiple, technologically enhanced information channels drain resources while hindering effective recovery, tipping the individual into repeated or prolonged threat states (e.g., Harunavamwe and Ward, 2022). We believe that a consolidated understanding of the first-person experience of this tipping point may help organizational scholarship investigate and intervene at the precise appraisals (e.g., endorsing fairness standards, enhancing predictability and controllability of work demands) and coping strategies (e.g., endorsing pro-active recovery of personal resources and offering instrumental support) that may interrupt feelings of getting overwhelmed and prevent its negative consequences such as employee withdrawal and mental or physical ill-health (see for example Cole et al., 2010; Palamarchuk and Vaillancourt, 2021).

Practical contributions

Our findings offer actionable insights for individuals, managers, and organizations seeking to better recognize, prevent, and respond to overwhelm at work. First, our work highlights the key signals and symptoms to look for. While overwhelm often results from high workload, unpredictable and urgent requests, lack of managerial support, and misaligned role expectations, it is highly shaped by how individuals perceive their ability to cope. Because overwhelm often lacks visible behavioral cues, it is easy to overlook. For organizations and managers, this underscores the importance of reducing preventable antecedent conditions—such as making workload more predictable, clarifying role expectations, and fostering supportive communication. Additionally, managers and colleagues can learn to recognize early warning signs such as withdrawal, decision paralysis, or contradictory signs of fatigue yet heightened alertness, all of which may signal that someone has reached their tipping point. From the individual employee's perspective, our findings emphasize the importance of developing self-awareness around personal thresholds and internal bodily signs of becoming overwhelmed. Employees can benefit from proactively identifying their own triggers, communicating boundaries, and cultivating sustainable, flexible coping strategies—such as seeking timely support and engaging in recovery when effortful problem-solving coping risk depleted available resources. Recognizing that the experience of being overwhelmed is subjective and may manifest differently across individuals, employees play a critical role in safeguarding their own well-being and in communicating their needs to supportive others.

Second, organizations must foster environments where individuals feel psychologically safe to reflect on and share how they are experiencing their work demands. Overwhelm is often accompanied by negative feelings and self-evaluations—such as anxiety, frustration, unrealistic standards, and perceived inadequacy—that can intensify the experience and inhibit help-seeking. Open, non-judgmental conversations supported by active listening can help surface these internal states and enable earlier support. Third, interventions should support not only task management but also internal sensemaking and reappraisal. Tools such as guided reflection, reappraisal coaching, peer support, and intentional recovery practices (e.g., micro-breaks or resource-building routines) can help individuals restore balance and recalibrate their responses before overwhelm escalates. In doing so, organizations can shift from reactive stress management to a more integrated and preventive approach that protects both individual well-being and sustainable performance.

Future directions and limitations

Our contextualized analysis of the core experience of being overwhelmed may foster new hypotheses for theory elaboration on work stress. First, our first-person narratives of being overwhelmed as a subjective tipping point toward a highly negative perception of demands supports previous quantitative-empirical and theoretical accounts of a non-linear effect of demands (e.g., time pressure, work-family conflict) on negative outcomes to work and well-being, such as exhaustion, vigor, job satisfaction, and burnout (Brzykcy et al., 2022; Gerich and Weber, 2020; Haldorai et al., 2022; Reis et al., 2017). Our findings highlight a potential discrepancy between actual demand-resource imbalances and their perception, which may be delayed or distorted. Similar to how satiety signals do not necessarily match feelings of fullness in eating (e.g., Benelam, 2009; Godfrey et al., 2015), individuals may not immediately notice when their resources have been depleted or overloaded, leading to a lag between objective overload and felt overwhelm. This opens promising avenues for future research on how accurately individuals detect and respond to mounting demands.

A second pathway for further study is to examine the potential downstream consequences of being overwhelmed at work, specifically burnout. As Demerouti et al. (2001), p. 686) state, “the experience of work can sometimes become so overwhelming that it leads to burnout”. The authors argue that more research on burnout prevention is needed since previous intervention studies have focused on broad stress relief for individuals already suffering from burnout, rather than addressing its causes relating to the unresolved combination of high job demands and low job resources. Longitudinal research (e.g., Otto et al., 2021) suggests that pro-active interventions –implemented before employees' have depleted their resources and lack the energy to cope- are essential to prevent burnout. Our work suggests that being overwhelmed marks the onset of a threat state and following negative consequences better than other stress-related affective states (nervous, anxious, frustrated etc.), which previous research finds to be related to both challenge and threat states (Blascovich and Mendes, 2000; Jones et al., 2009; Meijen et al., 2020; Uphill et al., 2019). Our findings show that cognitive and physical exhaustion -a key dimension of burnout- often accompanies overwhelm, fostering negative self-evaluations and attitudes toward work and colleagues. Thus, future research might explore how enduring states of being overwhelmed may pre-empt burnout, and assess the effectiveness of pro-active intervention initiated when employees experience prolonged and distinct states of overwhelm.

This implies early detection tools that capture the individual's perceived tipping point into a prolonged threat state. Our work can help to address this methodological requirement because our rich dataset of employees' narrative accounts can be used to develop a psychometric scale that measures overwhelm at each level of its five components. This would support a standardized assessment and application of overwhelm in organizational settings, enabling hypothesis testing such as the prediction of negative consequences including burnout, turnover, and overall ill-health (Demerouti et al., 2021; Schaffran et al., 2019).

While our qualitative approach was designed to provide rich insight into subjective experiences of being overwhelmed, it also poses limitations that could give rise to future exploration. First, retrospective self-report introduces recall bias, as participants may selectively reconstruct the most salient episodes of overwhelm. For example, the small minority of participants (5%) who described positive experiences of overwhelm may represent an underestimation, as negative events typically carry greater weight in affective memory and representation than positive ones (Rozin and Royzman, 2001). This highlights the value of future research using longitudinal or real-time data collection methods to capture the full spectrum of overwhelm experiences, including rare instances where the state may carry ambivalent or even positive valence. Second, although we distinguish between objective conditions and subjective appraisals of stressors, we cannot independently verify the actual demand-resource balance, which could give rise to more quantitative exploration. Third, our reliance on self-report without triangulation limits causal inference. To address this, further research using mixed-method or experimental designs can clarify the objective conditions that are causally related to experiences of being overwhelmed. For example, standardized simulations such as in HR assessments can serve as a controlled test environment to investigate these questions.

Further, our study is limited to the working population in an English-speaking cultural context and for mainly salaried employees. To fully understand this phenomenon, it is crucial to examine a broader sample from different cultural and organizational contexts. Do its manifestations, antecedents, triggers, and coping strategies vary globally and across organizations or professions (e.g., self-employed workers)? We would expect to find higher rates of overwhelm experiences in professions where overwork is common (e.g. consultancy, entrepreneurs), and in cultures where personal autonomy and control is valued (for example in individualistic cultures) or where the political-economic uncertainty is high and tolerance for uncertainty is low (Liu and Spector, 2005; Mazzola et al., 2011). Future studies could explore how contextual variables—such as job autonomy, organizational support, or employment precarity—moderate the appraisal and expression of being overwhelmed.

In conclusion, our thematic analysis of first-person narratives of employees' experiences of being overwhelmed highlights the critical turning point in the stress process and sheds light on an understudied yet pervasive phenomenon. Integrating our findings with prior literature, we define being overwhelmed as a distinct affective state occurring at the tipping point where perceived demands exceed available personal resources. Our findings highlight the paradoxical nature of being overwhelmed—marked by both heightened alertness and exhaustion—alongside a mental freeze response that disrupts performance, well-being, and workplace relationships. By mapping its antecedents, manifestations, and consequences, we offer a theoretical foundation for future research while underscoring the urgent need for organizational strategies to recognize and mitigate overwhelm. Addressing this phenomenon proactively may foster healthier, more sustainable work environments.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

This study was approved by CER-HEC, University of Lausanne, Switzerland. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

ND: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AM: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. FK: Conceptualization, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Alibudbud, R. (2023). Google Trends for health research: its advantages, application, methodological considerations, and limitations in psychiatric and mental health infodemiology. Front. Big Data 6:1132764. doi: 10.3389/fdata.2023.1132764

American Psychological Association (2023). Work in America survey. Available online at: https://www.apa.org/pubs/reports/work-in-america/2023-workplace-health-well-being (Accessed September 28, 2023).

Andresen, M., Goldmann, P., and Volodina, A. (2018). Do overwhelmed expatriates intend to leave? The effects of sensory processing sensitivity, stress, and social capital on expatriates' turnover intention. Eur. Manag. Rev. 15, 315–328. doi: 10.1111/emre.12120

Bakker, A. B., and Demerouti, E. (2007). The job demands-resources model: state of the art. J. Manag. Psychol. 22, 309–328. doi: 10.1108/02683940710733115

Balducci, C., Schaufeli, W. B., and Fraccaroli, F. (2011). The job demands–resources model and counterproductive work behaviour: the role of job-related affect. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 20, 467–496. doi: 10.1080/13594321003669061

Benelam, B. (2009). Satiation, satiety and their effects on eating behaviour. Nutr. Bull. 34, 126–173. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-3010.2009.01753.x

Blascovich, J., and Mendes, W. B. (2000). “Challenge and threat appraisals: the role of affective cues,” in Feeling and Thinking: The Role of Affect in Social Cognition, ed. J. Forgas (New York, NY: Cambridge University Press), 59–82.

Bliese, P. D., Edwards, J. R., and Sonnentag, S. (2017). Stress and well-being at work: a century of empirical trends reflecting theoretical and societal influences. J. Appl. Psychol. 102, 389–402. doi: 10.1037/apl0000109

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Brzykcy, A. Z., Rönkkö, M., Boehm, S. A., and Goetz, T. M. (2024). Work-family conflict and strain: Revisiting theory, direction of causality, and longitudinal dynamism. J. Appl. Psychol. 109, 1833–1860. doi: 10.1037/APL0001204

Carver, C. S., Scheier, M. F., and Weintraub, K. J. (1989). Assessing coping strategies: a theoretically based approach. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 56:267. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.56.2.267

Christensen, K., and Aldao, A. (2015). Tipping points for adaptation: connecting emotion regulation, motivated behavior, and psychopathology. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 3, 70–74. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2014.12.015

Cole, M. S., Bernerth, J. B., Walter, F., and Holt, D. T. (2010). Organizational justice and individuals' withdrawal: unlocking the influence of emotional exhaustion. J. Manag. Stud. 47, 367–390. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6486.2009.00864.x

Deloitte Insights (2022). The C-suite's Role in Well-Being. Available online at: Www2.Deloitte.Com/Xe/En/Insights/Topics/Leadership/Employee-Wellness-in-the-Corporate-Workplace.html (Accessed May 7, 2022).

Demerouti, E. (2015). Strategies used by individuals to prevent burnout. Eur. J. Clin. Invest. 45, 1106–1112. doi: 10.1111/eci.12494

Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Nachreiner, F., and Schaufeli, W. B. (2001). The job demands-resources model of burnout. J. Appl. Psychol. 86, 499–512. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.86.3.499

Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Peeters, M. C. W., and Breevaart, K. (2021). New directions in burnout research. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 30, 686–691. doi: 10.1080/1359432X.2021.1979962

Dewe, P. (1992). Applying the concept of appraisal to work stressors: some exploratory analysis. Hum. Relat. 45, 143–164. doi: 10.1177/001872679204500203

Dunn, J. (2024). Feeling Overwhelmed? Try Tallying Your Tiny Wins. The New York Times. Available online at: https://www.nytimes.com/2024/03/29/well/live/overwhelmed-small-wins.html (accessed April 24, 2023).

Fontaine, J. R. J., Gillioz, C., Soriano, C., and Scherer, K. R. (2022). Linear and non-linear relationships among the dimensions representing the cognitive structure of emotion. Cogn. Emot. 36, 411–432. doi: 10.1080/02699931.2021.2013163

Fontaine, J. R. J., Scherer, K. R., and Soriano, C., (eds.). (2013). Components of Emotional Meaning: A Sourcebook. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Fugate, M., Prussia, G. E., and Kinicki, A. J. (2012). Managing employee withdrawal during organizational change: the role of threat appraisal. J. Manag. 38, 890–914. doi: 10.1177/0149206309352881

Gallup (2022). Global Emotions Report. Available online at: https://www.gallup.com/analytics/349280/gallup-global-emotions-report.aspx (accessed July 6, 2022).

Gallup (2023). Global Emotions Report. Available online at: https://www.gallup.com/analytics/349280/gallup-global-emotions-report.aspx (accessed March 3, 2024).

Ganster, D. C., and Rosen, C. C. (2013). Work stress and employee health: a multidisciplinary review. J. Manag. 39, 1085–1122. doi: 10.1177/0149206313475815

Garnefski, N., and Kraaij, V. (2007). The cognitive emotion regulation questionnaire: psychometric features and prospective relationships with depression and anxiety in adults. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 23, 141–149. doi: 10.1027/1015-5759.23.3.141

Gerich, J., and Weber, C. (2020). The ambivalent appraisal of job demands and the moderating role of job control and social support for burnout and job satisfaction. Soc. Indic. Res. 148, 251–280. doi: 10.1007/s11205-019-02195-9

Godfrey, K. M., Gallo, L. C., and Afari, N. (2015). Mindfulness-based interventions for binge eating: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Behav. Med. 38, 348–362. doi: 10.1007/s10865-014-9610-5

Haldorai, K., Kim, W. G., and Phetvaroon, K. (2022). Beyond the bend: the curvilinear effect of challenge stressors on work attitudes and behaviors. Tour. Manag. 90:104482. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2021.104482

Harunavamwe, M., and Ward, C. (2022). The influence of technostress, work–family conflict, and perceived organisational support on workplace flourishing amidst COVID-19. Front. Psychol. 13:921211. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.921211

Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources: a new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am. Psychol. 44, 513–524. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.44.3.513

Hobfoll, S. E. (2011). Conservation of resource caravans and engaged settings. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 84, 116–122. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8325.2010.02016.x

Hobfoll, S. E., and Freedy, J. (1993). “Conservation of resources: a general stress theory applied to burnout,” in Professional Burnout: Recent Developments in Theory and Research, eds. W. B. Schaufeli, C. Maslach, and T. Marek (Washington, DC: Taylor & Francis), 115–129.

Hobfoll, S. E., Halbesleben, J., Neveu, J.-P., and Westman, M. (2018). Conservation of resources in the organizational context: the reality of resources and their consequences. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 5, 103–128. doi: 10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032117-104640

Horan, K. A., Nakahara, W. H., DiStaso, M. J., and Jex, S. M. (2020). A review of the Challenge-Hindrance Stress Model: recent advances, expanded paradigms, and recommendations for future research. Front. Psychol. 11:560346. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.560346

Hunziker, S., Laschinger, L., Portmann-Schwarz, S., Semmer, N. K., Tschan, F., and Marsch, S. (2011). Perceived stress and team performance during a simulated resuscitation. Intensive Care Med. 37, 1473–1479. doi: 10.1007/s00134-011-2277-2

Jones, M., Meijen, C., McCarthy, P. J., and Sheffield, D. (2009). A theory of challenge and threat states in athletes. Int. Rev. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2, 161–180. doi: 10.1080/17509840902829331

Kahn, R. L., and Quinn, R. P. (1970). “Role stress: a framework for analysis,” in Occupational Mental Health, ed. A. McLean (New York, NY: Rand McNally), 50–115.

Kilgarriff, A., Baisa, V., Bušta, J., Jakubíček, M., Kovár, V., Michelfeit, J., et al. (2014). The Sketch Engine: ten years on. Lexicography 1, 7–36. doi: 10.1007/s40607-014-0009-9

Lazarus, R. S. (2000). Toward better research on stress and coping. Am. Psychol. 55, 665–673. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.55.6.665

Lazarus, R. S. (2006). Stress and Emotion: A New Synthesis. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company.

Lazarus, R. S., and Cohen-Charash, Y. (2001). “Discrete emotions in organizational life,” in Emotions at Work: Theory, Research and Applications for Management, eds. R. L. Payne and C. L. Cooper (Chichester: John Wiley & Sons), 45–81.

Lazarus, R. S., and Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, Appraisal, and Coping. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company.

Lee, J. S., Joo, E. J., and Choi, K. S. (2013). Perceived stress and self-esteem mediate the effects of work-related stress on depression. Stress Health 29, 75–81. doi: 10.1002/smi.2428