Abstract

Schistosomiasis is a neglected tropical disease affecting over 240 million people globally, with sub-Saharan Africa bearing the highest burden. In Kenya, transmission of Schistosoma mansoni, the causative agent of intestinal schistosomiasis, remains prevalent in western, coastal, and central regions, particularly in the Mwea Irrigation Scheme and the Lake Victoria basin. The parasite depends on Biomphalaria snails as intermediate hosts, yet ecological determinants influencing infection dynamics remain underexplored. This study examined S. mansoni infection in Biomphalaria snails across two contrasting ecosystems: Lake Victoria and the Mwea rice irrigation scheme in Kenya. Snails, water, and soil samples were collected from the study sites. Water and soil were analyzed for abiotic parameters, including temperature, turbidity, salinity, pH, and soil porosity, while snail infections were confirmed via cercarial shedding and PCR targeting the ITS region. Laboratory-maintained isolates of S. mansoni were passed through baboons and served as positive controls for molecular identification. Biomphalaria pfeifferi was the most dominant species (90.4% of all snails sampled). Infection prevalence among infected snails varied across sites around Lake Victoria basin: Anyanga Beach, Siaya (70.8%, 80/113), Sindo Rangwena, Homabay (20.6%, 7/34), Kasabong, Siaya (16.9%, 12/71), and Kendu Bay, Homabay (16.7%, 3/18), with a chi-squared test confirming a strong site–infection association (χ² = 67.33, df = 3, p < 0.001), indicating significant spatial heterogeneity in transmission risk. Infection correlated positively with temperature (r = 0.72, p < 0.01) and soil porosity (r = 0.65, p < 0.05), and negatively with turbidity (r = −0.63, p < 0.01) and salinity (r = −0.58, p < 0.05) for samples found in areas around Lake Victoria basin. Molecular screening of 272 snail-derived samples using ITS1 primers yielded 113 positives. Sequencing confirmed B. pfeifferi (600 bp) from Mwea Irrigation Scheme and Lake Victoria Basin, forming a monophyletic clade with strong bootstrap support. The 500 bp ITS1 fragment identified S. mansoni in lab-maintained strains and Thiba in Mwea Irrigation Scheme samples, clustering within the S. mansoni clade. Further analysis of cercariae using 18S rDNA revealed ≥98% similarity to Zygocotyle lunata in Lake Victoria sites, forming a well-supported clade distinct from schistosomes.

1 Introduction

Schistosomiasis, a parasitic disease caused by Schistosoma species, remains one of the most neglected tropical illnesses, predominantly affecting populations in sub-Saharan Africa. An estimated 240 million individuals are infected globally, with over 90% of the burden concentrated in sub-Saharan Africa (Hotez et al., 2019; World Health Organization, 2022). The disease thrives in communities lacking clean water and sanitation, resulting in significant morbidity and mortality, with the World Health Organization (WHO) estimating over 200,000 deaths annually (WHO, 2023). In Kenya, approximately 17.4 million people are at risk, with high prevalence rates observed in the Lake Victoria basin, coastal, central, and lower eastern regions (WHO, 2013; Vale et al., 2017). Mwea Irrigation Scheme in Kirinyaga County and areas surrounding Lake Victoria remain particularly hyperendemic (Odiere et al., 2012; Gichuki et al., 2019; Handzel et al., 2003; Steinmann et al., 2006; Steinauer et al., 2008).

The disease presents in intestinal and urogenital forms, with Schistosoma mansoni primarily causing intestinal schistosomiasis. The current WHO control strategy involves mass drug administration (MDA) with praziquantel and snail control wherever feasible. However, MDAs fail to eliminate juvenile worms and do not prevent reinfection. Malacological surveys for schistosome infection detection are always not feasible in the surveillance of schistosomiasis.

Biomphalaria snails, the intermediate hosts of S. mansoni, thrive in freshwater bodies, with their abundance influenced by various climatic and ecological factors (Monde et al., 2016). However, the relationship between their infection rates and environmental factors is not fully elucidated. Research indicates that behavioral and environmental factors such as water quality significantly impact snail abundance and infectivity (Mereta et al., 2019).

Traditional methods for cercarial shedding often fail to identify prepatent infections, highlighting the need for more sensitive molecular techniques for effective surveillance (Joof et al., 2020; Hamburger, 2017; Nwoko et al., 2021). This study therefore aims to bridge these knowledge gaps and support the development of localized vector control and disease elimination strategies. Molecular screening is crucial for detection of trematodes that infect Biomphalaria snails, as morphology often does not effectively differentiate between closely related species. Blasco-Costa et al. (2016) emphasized the importance of optimal methods for trematode classification, recommending ribosomal and mitochondrial markers such as ITS and COI for accurate precise species determination. demonstrated this approach by sequencing larval trematodes from South African snails, showing that molecular data can clarify phylogenetic placement where morphology is ambiguous. Salloum et al. (2023) also utilized ITS rDNA markers to identify trematode communities in African freshwater snails, uncovering co-infections and their evolutionary relationships. DeJong et al. (2001) and Zhang et al. (2019) provided phylogenetic evidence of African origins of Biomphalaria hosts and variability in markers, aiding in precise host identification in endemic areas. These research efforts highlight the significance of molecular methods for species-specific identification and phylogenetic investigation, essential for mapping transmission routes and informing schistosomiasis monitoring. Our study utilizes sequence-based markers (ITS1 and 18S rDNA) and phylogenetic techniques to evaluate relationships among S. mansoni and other trematodes infecting Biomphalaria snails in Mwea Irrigation Scheme and areas around Lake Victoria basin in Kenya, while additionally investigating environmental factors influencing infection dynamics in the Lake Victoria region.

The objectives were to (1) investigate the influence of environmental factors (water temperature, water turbidity, water pH, soil porosity, and water salinity) on Biomphalaria snail infection dynamics around the Lake Victoria basin and (2) to assess the phylogenetic relationships between S. mansoni and other trematode species infecting Biomphalaria snails in areas around Lake Victoria basin and Mwea Irrigation Scheme. By employing sequence-based markers and phylogenetic methods, this study provides insights into species-level characterization and evolutionary relationships among trematodes infecting shared Biomphalaria snail hosts, thereby enhancing understanding of parasite–host associations in endemic freshwater ecosystems in Kenya. In addition, understanding the role of environmental factors in shaping Biomphalaria infection dynamics is essential to improve and inform schistosomiasis control efforts in areas around the Lake Victoria basin.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Study sites

Fieldwork was conducted between July and October 2023 in two sites in Kenya, Mwea Irrigation Scheme, located in Kirinyaga county and areas surrounding Lake Victoria that encompasses several counties including Homabay, Siaya, Kisumu and Nyamira Counties, which are approximately 470 km apart. Mwea Irrigation Scheme (513 km²) receives 1,200–1,600 mm of annual rainfall Masaku et al. (2015) and contains a large rice irrigation scheme supported by Thiba and Nyamindi Rivers. The region is characterized by flat terrain with black cotton and red soils and is hyperendemic for S. mansoni (Kihara et al., 2007).

Lake Victoria, Africa’s largest freshwater lake, lies at 1,133 meters above sea level and experiences a tropical climate with temperatures ranging from 21°C to 26°C. The Lake is replenished by direct rainfall and flows from over 20 rivers originating in five East African countries. While the Kagera and Mara are the only transboundary rivers, others such as the Nzoia, Yala, Nyando, Sondu Miriu, and Sio flow from Kenya. Additionally, rivers from Tanzania and Uganda contribute to the lake, which drains solely through the White Nile. Lake Victoria harbors Biomphalaria snails which are pivotal in disease transmission. The lake also supports the livelihoods of millions by providing water for farming, fishing, and domestic use (Vanderkelen et al., 2018).

To ensure appropriate site selection, an initial survey was conducted prior to sampling in both Lake Victoria and Mwea Irrigation Scheme. This survey aimed to identify the presence and distribution of Biomphalaria snails, considering that climatic conditions and human activities, such as farming and livestock rearing, can significantly impact snail populations. Specific sampling sites were selected based on direct field observations indicating moderate to high snail abundance during the preliminary assessment, ensuring that sampling was both targeted and ecologically relevant. Sampling sites included Kianganga, Murinduko, Thiba, and Togonye in Mwea Irrigation Scheme (Kirinyaga County), and Anyanga, Kasabong (Siaya County), Rangwena (Homabay County), Asao, and Awach rivers (Kisumu County). GPS coordinates were recorded using Garmin etrex 10 (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Indicates the study sites in Kenya where sampling was conducted in two geographical zones: Lake Victoria basin (Homa Bay, Siaya, Nyamira) and Mwea Irrigation Scheme (Kirinyaga County). County boundaries are shown in grey; red dots indicate sampling locations.

2.2 Water and soil sample collection

Corresponding water and soil samples were collected at each snail sampling site. Water (500 ml) was collected in plastic bottles, pre-rinsed with river water, and sealed. Soil (500 g) was collected by digging to a depth of 15 cm. Samples were stored in cool boxes maintained with ice packs at 4°C and transported to the Kenya Marine and Fisheries Research Institute (KEMFRI), Kisumu for analysis.

2.3 Environmental parameter analysis

Temperature was measured in situ at each sampling site using a standard mercury−in−glass laboratory thermometer (Gilson Co., USA), with a measurement range of –20 to 110°C, while all other physicochemical parameters were analyzed in the laboratory. Turbidity was assessed using a Lovibond TB350 IR turbidity meter (Germany); pH was measured with a Thermo Scientific Eutech pH electrode (Singapore); and salinity was determined using a HI2003 edge conductivity meter (Italy). Water appearance was recorded visually at the time of sampling. Soil porosity was measured using the saturation method (Moret-Fernández and López, 2019), which involved graduated cylinders to quantify water absorption and soil mass before and after oven drying at 105°C.

2.4 Morphological and molecular detection of Biomphalaria snails and their trematode infections

Biomphalaria snails were collected using scoops and forceps and placed in moist, perforated containers for transport to the tropical and infectious disease laboratory at the Kenya Institute of Primate Research (KIPRE), Nairobi. Initial identification of the snails was performed in the field based on morphological features as outlined by Brown and Kristensen (1993). Snails were then individually exposed to a 60-watt bulb in 24-well plates for two hours to facilitate the shedding of cercariae. The cercariae were identified morphologically using a dissecting microscope, based on standard morphological keys, including forked tail morphology and characteristic swimming behavior (Frandsen and Christensen, 1984). Notably, simple-tailed cercariae were also identified. All snails underwent further molecular analysis where species confirmation was subsequently conducted through molecular analysis targeting the ITS1 gene.

Snail tissue was extracted from the shell with a forceps and macerated from the foot–head region following standard molluscan tissue sampling as described by (Kane et al., 2008). DNA was isolated using the Qiagen DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Germany) with minor protocol modifications. DNA concentration and purity was measured using a Qubit Fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). PCR targeting the ITS1 region was performed using ETTS2 (5′-TAA CAA GGT TTC CGT AGG TGA A-3′) and ETTS17 (5’-CGA GCC GGA TGA TCC ACC GC-3′) primers to simultaneously detect snail and S. mansoni DNA Bakuza et al. (2017). ITS1 positive samples were further analyzed using SM-IMRS primers targeting the 18S rDNA region: forward 5′-CGGTGAAACCGCGAATGGCTC-3′ and reverse 5′-CGCACCCGGTTGGTTCTGTTC-3′, to investigate S. mansoni phylogenetic relationships Ally et al. (2024a, b). PCR cycling conditions followed those described by Bakuza et al. (2017) and Ally et al. (2024a, b) respectively. PCR products were confirmed on 1% agarose gel: 600 bp for snail DNA and 500 bp for S. mansoni using ITS1 primers, and 151 bp for S. mansoni using SM-IMRS primers. Positive DNA controls for all molecular assays were prepared as follows: stool samples as described by Kanyi et al. (2024) were collected from laboratory-maintained baboons (Papio anubis), that had been experimentally infected with S. mansoni. DNA was then extracted using the QIAamp Fast DNA Stool Mini Kit (Qiagen, Germany), following the manufacturer’s protocol.

2.5 Sanger sequencing and phylogenetic analysis

PCR-positive samples including snail DNA, cercarial DNA from field-collected snails, and stool-derived DNA from experimentally infected baboons from KIPRE were submitted to the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI), Nairobi, for bi-directional Sanger sequencing using the Applied Biosystems 3500XL Genetic Analyzer (Thermofisher, USA). Sequence trace data were inspected in Chromas Pro v2 to confirm accurate peak-to-base alignment prior to trimming. Sequences that failed to meet quality standards were excluded from downstream analyses. Consensus sequences were extracted and compared to GenBank entries using BLASTN sequence homology searches. Multiple sequence alignment including reference sequences retrieved from NCBI was performed using MUSCLE in MEGA 11, and phylogenetic trees were constructed using the Maximum Likelihood method with the Tamura-Nei model. Tree robustness was assessed through bootstrap analysis (1,000 replicates), and final visualization was done in R using the ape package (Paradis et al., 2004).

3 Results

3.1 Association between snail infectivity and environmental parameters

A total of 272 Biomphalaria snails were sampled across all study sites, of which 246 were morphologically identified as B. pfeifferi and 26 as B. sudanica (Table 1). Cercarial shedding revealed that 116 snails were infected with trematodes, corresponding to an overall infectivity prevalence of 42.6%. Of these, 102 infected snails originated from sites around Lake Victoria, while 14 were from the Mwea Irrigation Scheme. Biomphalaria pfeifferi exhibited marked variation in infection prevalence across sampling sites in western Kenya. The highest prevalence was observed at Anyanga Beach, Siaya County (70.8%, 80/113). Intermediate infection levels occurred at Sindo Rangwena in Homa Bay County (20.6%, 7/34) and Kasabong in Siaya County (16.9%, 12/71), while the lowest prevalence was recorded at Kendu Bay, Homa Bay County (16.7%, 3/18). A Pearson’s chi-squared test revealed a highly significant association between site and infection status (χ² = 67.33, df = 3, p < 0.001), indicating strong spatial heterogeneity in parasite transmission risk across the region (Figure 2). Infection levels exhibited a significant positive correlation with both water temperature and soil porosity (Figures 3B, E, respectively). Additionally, a weak but positive association was observed with pH (Figure 3A), suggesting that pH may have a secondary influence on parasite transmission dynamics. In contrast, salinity (Figure 3C) and turbidity (Figure 3D) showed negative correlations with infectivity, implying that these parameters may act as ecological constraints on transmission.

Table 1

| Sites | Snail species | |

|---|---|---|

| Biomphalaria sudanica | Biomphalaria pfeifferi | |

| Anyanga, Siaya (Lake Victoria basin) | 5 | 108 |

| Kasabong’, Siaya (Lake Victoria basin) | 13 | 58 |

| Sindo Rangwena, Homabay (Lake Victoria basin) | 8 | 26 |

| Kendu bay, Homabay (Lake Victoria basin) | 0 | 18 |

| Murinduko, Mwea Irrigation Scheme | 0 | 9 |

| Thiba, Mwea Irrigation Scheme | 0 | 12 |

| Togonye, Mwea Irrigation Scheme | 0 | 8 |

| Kianganga, Mwea Irrigation Scheme | 0 | 7 |

| Total | 26 | 246 |

| Abundance | 9.5% | 90.4% |

Distribution of Biomphalaria snail species across sampling sites in the Lake Victoria basin and Mwea Irrigation Scheme.

Bold values indicate the proportional abundance (%) of each Biomphalaria species calculated from the total snails sampled.

Figure 2

Spatial variation in infection prevalence among Biomphalaria snails in western Kenya. The number of infected and uninfected snails collected from Anyanga (Siaya), Kasabong (Siaya), Sindo (Homa Bay), and Kendu Bay (Homa Bay) is shown. Infection prevalence was highest in Anyanga (70.8%, 80/113), followed by Sindo (20.6%, 7/34), Kasabong (16.9%, 12/71), and Kendu Bay (16.7%, 3/18). A Pearson’s chi-squared test revealed a significant association between site and infection status (χ² = 67.325, df = 3, p < 1.596 × 10-14), indicating spatial heterogeneity in transmission risk across the study area.

Figure 3

Kendall’s Tau correlation plots (with p-values) illustrating the relationships between infectivity in Biomphalaria snails and key environmental variables: pH (A), soil porosity (B), salinity (C), turbidity (D), and temperature (E).

3.2 Molecular detection of Biomphalaria snails and their trematodes

Out of 272 snail-derived samples screened using ITS1 primers, 113 yielded PCR amplicons. Representative PCR-positive samples were selected by site for sequencing to validate species identification and assess phylogenetic relationships. Eight out of 15 samples were successfully sequenced and BLAST analysis revealed that the 600 bp fragment corresponded to Biomphalaria pfeifferi found in Mwea Irrigation Scheme and Lake Victoria sites, including Homa Bay and Siaya and the 500 bp band as S. mansoni in laboratory-maintained samples at KIPRE and in Thiba (Mwea Irrigation Scheme). The Sequences were submitted to GenBank with accession numbers (PX580465-PX580472).

Following ITS1 screening, the 113 samples that tested positive were further analyzed using SM-IMRS primers targeting the 18S rDNA region. Ninety-seven samples were PCR positive and 22 representative samples were selected for sequencing and downstream analysis. Forty-four high-quality sequences were obtained from cercariae shed by Biomphalaria snails collected around the Lake Victoria basin. Both forward and reverse reads were successfully generated and retained, while samples that did not yield reliable trace data were excluded from further analysis. BLAST analysis revealed highest similarity (≥98%) to Zygocotyle lunata reference sequences in GenBank accession number (MH915581.1, KM538164.1), confirming species-level identity. No significant matches to other amphistome genera were observed and in consideration of the snail species collected in the field. The sequences were submitted to GenBank with accession numbers (PX448099-PX448120).

3.3 Phylogenetic analysis

Maximum Likelihood analysis of ITS1 sequences (600 bp) grouped all field Biomphalaria pfeifferi isolates into a monophyletic clade, confirming species identity. Bootstrap support was strong for samples collected in Kasabong in Siaya and Murinduko in Mwea Irrigation Scheme (100) and moderate for those in Anyanga, Siaya (83), indicating close phylogenetic relationships among Lake Victoria basin and Mwea Irrigation Scheme populations. Kendubay, Homabay and Kianganga, Mwea Irrigation Scheme isolates clustered near reference sequences of B. sudanica and B. choanomphala (bootstrap = 63–80), suggesting phylogenetic proximity among East African Biomphalaria species. Biomphalaria smithi served as an outgroup, reinforcing species-level separation (Figure 4).

Figure 4

Phylogenetic tree illustrating Kenyan Biomphalaria pfeifferi isolates from Siaya (Anyanga, Kasabong) and Mwea (Murinduko, Kianganga) cluster together, confirming species identity. Homabay Kendubay isolates group near reference sequences of B. sudanica and B. choanomphala, while B. smithi serves as an outgroup.

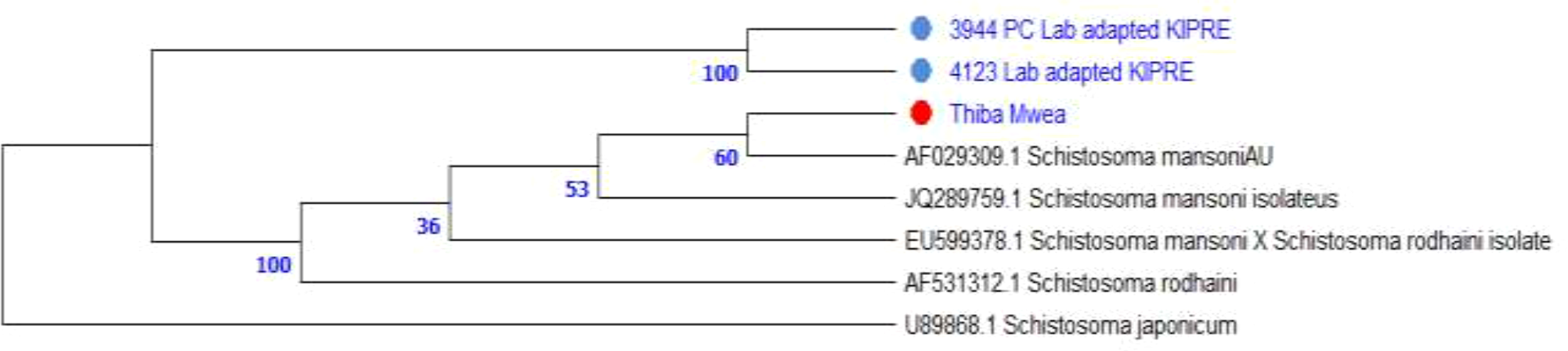

Phylogenetic analysis of ITS1 (~500 bp) placed all field isolates within the S. mansoni clade with strong bootstrap support (=100 for lab-adapted strains). The Thiba, Mwea Irrigation Scheme isolate is grouped closely with KIPRE strains, confirming species identity. All local isolates were distinct from S. rodhaini and S. japonicum, indicating no cross-species contamination (Figure 5).

Figure 5

Maximum Likelihood phylogenetic tree of ITS1 sequences (~500 bp) shows S. mansoni isolates (colored dots) from Thiba in Mwea Irrigation Scheme, Kirinyaga County and lab adapted samples from KIPRE clustering within the S. mansoni clade, while remaining distinct from S. rodhaini and S. japonicum (outgroup).

Analyzing the Maximum Likelihood for the 18S rDNA sequences located all samples collected around Lake Victoria basin (Anyanga and Kasabong’ in Siaya county and Rangwena in Homabay county) in a well-supported monophyletic clade of Zygocotyle lunata next to the reference sequences (MH915581.1, KM538164.1). Support for clades among the Lake region isolates was low (0-53), however, the node that united the Lake region sequences to the reference sequences was well-supported (bootstrap = 100), confirming the species identity. S. mansoni isolates formed a distinct sister clade (bootstrap = 66), clearly separating amphistomes from schistosomes, with S. japonicum as an outgroup (Figure 6).

Figure 6

Maximum Likelihood analysis of 18S sequences placed all isolates collected in areas around Lake Victoria in a monophyletic Zygocotyle lunata clade with reference sequences (MH915581.1, KM538164.1). Bootstrap support for subclades among those isolates was low (0–53), The node joining these isolates and reference sequences showed strong support (bootstrap = 100), confirming species identity. Schistosoma mansoni formed a distinct sister clade (bootstrap = 66), with S. japonicum as the outgroup, indicating clear separation between amphistomes and schistosomes.

4 Discussion

Our findings reinforce that schistosomiasis remains a persistent public health concern in regions of Kenya historically classified as endemic, including areas surrounding the Lake Victoria basin and the Mwea Irrigation Scheme (Masaku et al., 2020; Ogongo et al., 2022) as evidenced by presence of documented intermediate hosts responsible for transmission (Figure 4). In this study, we assessed how environmental parameters of soil and water including water temperature, soil porosity, water turbidity, water pH and water salinity correlated with trematode infection rates in Biomphalaria snails collected from different locations in the Mwea Irrigation Scheme and areas around the Lake Victoria basin (Figure 3). This study also examined the use of molecular techniques to detect schistosome infections in Biomphalaria snail intermediate hosts, along with phylogenetic characterization of both Biomphalaria snails and parasites they harbor: schistosomes and amphistomes.

4.1 Environmental factors are correlated with snail infectivity

Water turbidity was found to have a negative correlation with parasites infectivity in Biomphalaria snails suggesting that increased water turbidity may hinder parasite-host interactions. This could be attributed to various anthropogenic activities, such as animal watering, vehicle washing, and other disturbances, particularly observed at a collection site in Kasabong, Siaya. These activities contribute to elevated suspended particulate matter, which can interfere with parasite transmission. Our findings are consistent with previous studies, including Upatham, (1972a) and Olkeba et al. (2020), which demonstrated that miracidia were unable to infect snails at 500 ppm turbidity when the water became thick and muddy. Further research supports this, showing that Biomphalaria snails prefer clear, low-turbidity waters, while high turbidity can disrupt miracidia movement, reduce light penetration, and interfere with chemical signaling necessary for host detection Akande et al. (2013). Recent research indicates that increased turbidity has been linked to lower Biomphalaria population densities and reduced egg development, further impacting transmission dynamics (Hailegebriel et al., 2022; Sokouri et al., 2024; Rollinson et al., 2011; Odongo-Aginya and Eshita, 2008). Our findings suggest that high water turbidity, particularly in human-disturbed habitats, may act as a natural barrier to bilharzia transmission by reducing the efficiency of miracidia in locating and infecting Biomphalaria snails. This was evident in areas such as Kasabong in Siaya and Sindo Rangwena in Homa Bay, where infection rates were low whereas anthropogenic activities were high. Hailegebriel et al. (2022) corroborates with our findings where high turbidity levels potentially hindered miracidia’s ability to infect Biomphalaria snails, resulting in a decreased cercarial output.

Water salinity was found to have a negative correlation with parasites infectivity in Biomphalaria snails. There was a slight difference in water salinity between three sites, Anyanga in Siaya with a water salinity of 118 ppm, Kasabong in Siaya and Sindo Rangwena in Homa-Bay with a water salinity of 119 ppm yet the difference in schistosome infection rates was significant with Anyanga in Siaya showing a high level of schistosome infection rates while Kasabong in Siaya and Rangwena in Homa-Bay showing lower schistosome infection rates. Previous research has demonstrated that salinity levels exceeding 1,200 ppm significantly impair miracidia survival and snail infection success Upatham (1972b). Our findings suggest that even at much lower salinity levels, transmission may still be modulated. This observation is supported by Campbell et al. (2025), who found that moderate salinity reduces B. pfeifferi reproduction and survival; Erkano (2021), who reported salinity as a limiting factor for snail distribution in Ethiopian freshwater bodies; and Sokouri et al. (2024), who identified salinity as negatively correlated with snail infectivity in Côte d’Ivoire. These studies collectively support our findings that even relatively low salinity levels may influence schistosome transmission dynamics.

Environmental conditions, particularly ambient temperature, play a crucial role in shaping host–parasite interactions and influencing disease dynamics (Leicht and Seppälä, 2014). Previous studies have shown that increased temperatures significantly impact schistosomes and their interactions with hosts, especially in Sub-Saharan Africa (Barbosa et al., 2016; Woolhouse and Chandiwana, 1990). Temperature influences the maturation, survival, dispersion, and productivity of intermediate host snails, thereby altering transmission dynamics (McCreesh and Booth, 2014; McCreesh et al., 2015). The free-living stages of Schistosoma are also temperature-dependent; cercarial production occurs between 15–31°C, which increases host metabolism and output (Poulin and Mouritsen, 2006; Mangal et al., 2008). Our study corroborates these findings where infection rates varied with temperature, peaking at 26°C in Anyanga, Siaya, moderate at 24°C in Kasabong, Siaya and low at 23°C in Sindo Rangwena, Homabay. This finding concurs with Upatham (1972b), who found infection increased from 14.3% at 16°C to 71.4% at 34°C, then declined to 10% at 40°C. Rowel et al. (2015) also reported a positive correlation between 27–28.7°C and intramolluscan survival. Recent Kenyan studies further support this, Magero et al. (2025) recorded a 22.5% S. mansoni prevalence in Biomphalaria pfeifferi around Lake Victoria has been shown to vary with environmental factors such as water temperature, and shedding rates of 0.67–0.86% have been reported in B. sudanica at Mbita in association with local environmental conditions and Aslan et al. (2024) estimated the thermal optimum for transmission at 23.1–27.3°C. These findings underscore temperature as a critical driver of parasite transmission dynamics (Odero et al., 2024).

Snail populations and their susceptibility to parasite infection can be indirectly influenced by soil porosity, which affects water retention, infiltration, and microbial activity. Although research specifically on soil porosity is limited, studies on substrate types emphasize its importance in shaping environmental conditions that drive schistosomiasis transmission dynamics. Kristensen et al. (2001) identified soil porosity as a key factor affecting snail distribution, survival, and vulnerability to infection. In our study, we observed a positive correlation between parasite infection rates in Biomphalaria snails and soil porosity. Anyanga (Siaya) recorded the highest porosity (50.02%), followed by Kasabong (Siaya) (36.64%) and Rangwena, Homa Bay (31.79%). Sites with higher porosity corresponded to higher infection rates, suggesting that areas with increased soil porosity may provide more favorable conditions for snail proliferation and parasite transmission. High soil porosity is often associated with greater water retention and more stable aquatic environments, which are critical for snail survival and reproduction (Mahya and Singh, 2022; Pires et al., 2023). These conditions not only allow snail populations to persist but also increase infection risk by prolonging exposure to parasite larvae (Kalinda et al., 2018). Consequently, soil porosity may be a critical ecological determinant of schistosomiasis hotspots and warrants further investigation. Our findings, which revealed higher infection rates in areas with greater porosity, underscore its potential role in shaping transmission dynamics.

Other ecological factors, such as snail population density, competition between snails and competition between parasites potentially played a role in influencing infection dynamics. Higher snail densities observed in Anyanga (Siaya) could have increased the probability of miracidia encountering a suitable host, leading to greater infection rates. In contrast, lower snail densities or competition with other snail species in Kasabong (Siaya) and Homa- Bay may have reduced parasites’ transmission efficiency. In addition, climatic factors could have contributed to regional differences in infection rates. Increased water flow due to rainfall or human activity could have diluted miracidia concentrations, reducing the likelihood of successful infections.

4.2 Phylogenetic resolution of snail hosts and schistosome isolates using ITS1 sequences

Our findings confirm the presence of B. pfeifferi along the shores of Lake Victoria in Siaya (Mutuku et al., 2021; Onyango et al., 2022) and is the dominant species in the Mwea Irrigation Scheme (Ngigi et al., 2019; Magero et al., 2025). This was verified through morphological and molecular analyses. Phylogenetic analysis of ITS1 sequences (600bp) resolved field Biomphalaria isolates into a well-supported monophyletic clade of B. pfeifferi, confirming species identity consistent with previous studies that demonstrated the utility of ITS markers for species-level resolution in African Biomphalaria (DeJong et al., 2001; Zhang et al., 2019). Subclades linking Kasabong (Siaya) and Murinduko (Mwea Irrigation Scheme) exhibited strong bootstrap support (100), while Anyanga (Siaya) grouped moderately (83), indicating close genetic relationships among Lake Victoria basin and Mwea Irrigation Scheme populations. Kendubay (Homabay) and Kianganga (Mwea Irrigation Scheme) clustered near reference sequences of B. sudanica and B. choanomphala (bootstrap = 63–80), suggesting phylogenetic proximity among East African Biomphalaria species as reported in earlier phylogenetic surveys. The placement of B. smithi as an outgroup reinforced species-level separation (Figure 4). The identified phylogenetic clustering has important implications for schistosomiasis mitigation.

Maximum Likelihood analysis of ITS1 sequences (500bp) placed field isolates within the Schistosoma mansoni clade, supported by strong bootstrap values. The Thiba, Mwea isolate is grouped closely with laboratory-adapted strains from KIPRE (bootstrap = 100), confirming species identity. Additional nodes showed moderate support (53 and 60), indicating genetic similarity among field and reference isolates. Schistosoma rodhaini formed a separate lineage (bootstrap = 36), and S. japonicum served as an outgroup, reinforcing phylogenetic separation between African schistosomes and other species. These findings validate the use of ITS1 for species-level resolution and confirm the phylogeny of field isolates within the S. mansoni clade (Figure 5). Accurate identification of snail hosts and parasite lineages allows for targeted interventions, such as localized molluscicide and predictive risk mapping. Furthermore, combining phylogenetic data with environmental factors like temperature, pH, and soil porosity can help enhance transmission models and optimize resource allocation in endemic locations.

4.3 Molecular identification and phylogenetic characterization of amphistome trematodes in Biomphalaria snails

Biomphalaria species have been reported to harbor several parasites, including members of the superfamilies Clinostomoidea, Diplostomoidea, Echinostomatoidea, Paramphistomoidea, and Pronocephaloidea, with studies revealing aspects of antagonism and competition among these digenean parasites (Esteban et al., 2011). The interactions between Biomphalaria species and non-schistosome trematodes are essential for understanding population and transmission dynamics, larval development, and the molecular characteristics of snail–trematode associations. These studies also shed light on the ecological impact of trematodes in animal hosts and provide insights into developing biological strategies to control schistosomiasis (Esteban et al., 2011; Laidemitt et al., 2019; Lu et al., 2024).

In our study, molecular techniques confirmed the presence of Zygocotyle lunata in the African Biomphalaria species, particularly B. pfeifferi, from Siaya and Homabay County. There were three lines of evidence for this identification: The first was in the context of the hosts, in which the cercariae were shed from B. pfeifferi and B. sudanica. The second was the morphology in which the cercariae had features of the amphistome type, which was consistent and similar to Z. lunata including simple-tailed cercariae (Spatz et al., 2012). The third line of evidence was the molecular data, in which BLAST analysis of the 18S rDNA sequences showed the highest similarity to Z. lunata and the other hits were to amphistome species that are not found in the Biomphalaria snails. The combination of these three lines of evidence supports the identification and classification of this species to Z. lunata.

Earlier reports of Z. lunata infections within the Biomphalaria genus have been confined to South American species, and in particular B. peregrina and B. tenagophila (Ostrowski de Núñez et al., 2003; Ostrowski de Núñez, 2011), while B. glabrata was thought to be refractory. Our phylogenetic analysis show the field isolates clustering in a monophyletic lineage with reference Z. lunata sequences, reinforced with high bootstrap values, indicating shared ancestry thereby confirming species level identity (Figure 6). The occurrence of amphistome type cercariae in conjunction with fork-tailed schistosome-type larvae replicates findings from South America where Z. lunata and Schistosoma mansoni were found sharing a snail host (Spatz et al., 2012). This emphasizes the complexity of trematode communities in African freshwater ecosystems and the high likelihood of multi-parasite assemblages.

Zygocotyle lunata is an intestinal fluke of ruminants which results in enteritis and productivity loss, suggesting that the presence of this parasite indicates the potential for parasite transmission to livestock which are likely to graze near the water bodies where the infected snails are found (Pfukenyi and Mukaratirwa, 2018). Our results highlight the urgency of integrated surveillance of the snail-borne parasites to mitigate the impact on public health and livestock production. This aligns with earlier reports identifying cattle, sheep, and other mammals as definitive hosts of Z. lunata in Europe and North America (Fried and Huffman, 2009; Achatz et al., 2025), a finding consistent with our field observations near Anyanga (Siaya) where there was presence of anthropogenic activities such as animal watering, specifically for sheep and cattle.

A key aspect to understanding the transmission and evolution of parasites is the phylogenetic relationships of amphistome trematodes in snail hosts of medical importance. Well established clades of Z. lunata have been reported from South American Biomphalaria species and separated from other paramphistomes (Ostrowski de Núñez et al., 2003; Ostrowski de Núñez, 2011). Our study involved the integration of parasite morphological identification, molecular and phylogenetic approaches targeting 18S rDNA where field isolates confirmed species- level identity and clustered within a strongly supported monophyletic clade of Z. lunata referenced sequences (Figure 6). Parasite presence was corroborated by ecological observations as previously discussed in this study. Our findings help build knowledge of the phylogenetic relationships of amphistomes, associations with hosts, and possible epidemiological impacts to livestock in East Africa; it also builds on studies concerning the taxonomy and molecular characteristics of Z.lunata.

Although our findings suggest the presence of Z. lunata in African Biomphalaria species, several limitations need to be noted: identification was based on amplification of the 18S rDNA region, which, although informative, has a lower phylogenetic resolution compared to other markers. More robust strategies targeting ITS2 or mitochondrial COI regions are likely to result in far better discriminatory power and an improved phylogenetic resolution. The results and the inferences we can draw from this are also limited because the study was only performed in two areas Siaya and Homabay counties in Kenya.

5 Conclusion

This study demonstrated that environmental factors such as turbidity, temperature and soil porosity significantly influence Biomphalaria snail infectivity and, consequently, schistosomiasis transmission in Kenya. High turbidity and salinity were negatively correlated with infection rates, while temperature and soil porosity showed positive associations, likely enhancing parasite-host interactions. The observed spatial heterogeneity in snail infectivity highlights the focal nature of schistosomiasis transmission, consistent with previous findings in East Africa (Odiere et al., 2012; Steinmann et al., 2006). Given the complex interplay of environmental variables in schistosomiasis endemic regions, further research is needed to better understand how subtle ecological changes influence parasite transmission and infection patterns.

Our findings confirm the presence of S. mansoni in Thiba within the Mwea Irrigation Scheme, providing critical baseline data to inform targeted schistosomiasis control strategies in this region. Additionally, the detection of B. pfeifferi, a known intermediate host, suggests potential local transmission pathways and underscores the need for integrated snail surveillance and management in studied areas.

Our results also suggest presence of Z. lunata in African Biomphalaria species, specifically B. pfeifferi based on molecular and phylogenetic analysis of field isolates collected in areas around Lake Victoria basin, Kenya. Using 18S rDNA sequences amplified with SMIRS primers, BLAST analysis and phylogenetic reconstruction confirmed that Kenyan isolates form a strongly supported monophyletic clade with reference Z. lunata sequences, indicating species-level identity. These findings extend the known host range and geographic distribution of Z. lunata beyond South America to East Africa.

Given the pathogenic role of Z. lunata in ruminants and cattle (Marcilla et al., 2012; Toledo et al., 2015), its presence in local snail populations suggests a potential transmission pathway to livestock, with implications for animal health and productivity. Future studies should focus on prevalence surveys, seasonal dynamics, and experimental infections to clarify the epidemiological significance of this parasite in East Africa.

Statements

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/supplementary material.

Ethics statement

The animal study was approved by Institutional Scientific and Ethics Review Committee ISERC/07/2022. The study was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

FP: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SN: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. MA: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. GO: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. CN: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. PK: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Methodology, Resources, Software, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MO: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. LO: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the support of George Ogara, Collins Ngudi, and Elisha Opiyo for their assistance with field sample collection. We thank Billy Ojuka, Cavin Mgawe, and Dr. Mercy Akinyi for their contributions to laboratory work. We also appreciate Patrick Karanja’s support with data analysis and Dr. Maurice Odiere for facilitating ethical clearance and offering guidance throughout the project. Sincere thanks to Dr. Lucy Ochola, Prof. Steven Ger Nyanjom, and Dr. Maurice Odiere for their mentorship. This research was conceptualized, funded, and coordinated by Florence N. Parsimei.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Achatz T. J. Morton L. B. Orlofske S. A. Brant S. V. Montes M. M. Bondone F. et al . (2025). A re-evaluation of Zygocotyle (Digenea, Paramphistomoidea) and synonymization with Wardius. J. Parasitol.111, 41–47. doi: 10.1645/24-114

2

Akande I. S. Odetola A. A. Akande I. S. Odetola A. A. (2013). Epidemiological survey of human and veterinary schistosomiasis. Parasitic Dis. - Schistosomiasis. doi: 10.5772/53523

3

Ally O. Kanoi B.N. Ochola L. Nyanjom S.G. Shiluli C. Misinzo G. et al . (2024). Schistosomiasis diagnosis: Challenges and opportunities for elimination. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis.18, e0012282. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0012282

4

Ally O. Kanoi B.N. Kamath S. Shiluli C. Ndombi E.M. Odiere M. et al . (2024). Development of a rapid and highly sensitive nucleic acid-based diagnostic test for schistosomes, leveraging on identical multi-repeat sequences. Front. Parasitol.1361493. doi: 10.3389/fpara.2024.1361493

5

Aslan I. H. Pourtois J. D. Chamberlin A. J. Mitchell K. R. Mari L. Lwiza K. M. et al . (2024). Re-assessing thermal response of schistosomiasis transmission risk: Evidence for a higher thermal optimum than previously predicted. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis.18, e0011836. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0011836

6

Time to set the agenda for schistosomiasis elimination. Available online at: https://reference.medscape.com/medline/abstract/22580511.

7

Bakuza J. S. Denwood M. J. Nkwengulila G. Mable B. K. (2017). Molecular detection of Schistosoma mansoni infection in freshwater snails in Tanzania: The importance of PCR primer selection. Parasites Vectors10, 234. doi: 10.1186/s13071-017-2178-3

8

Barbosa C. S. de Souza Gomes E. C. Campos J. V. de Oliveira F. J. M. da Silva Mesquita M. C. de Oliveira E. C. A. et al . (2016). Morbidity of mansoni schistosomiasis in Pernambuco—Brazil: Analysis on the temporal evolution of deaths, hospital admissions and severe clinical forms, (1999–2014. Acta Tropica164, 10–16. doi: 10.1016/J.ACTATROPICA.2016.06.024

9

Blasco-Costa I. Cutmore S. C. Miller T. L. Nolan M. J. (2016). Molecular approaches to trematode systematics: “Best practice” and implications for future study. Syst. Parasitol.93, 295–306. doi: 10.1007/s11230-016-9631-2

10

Brown D. S. Kristensen T. K. (1993). A Field Guide to African Freshwater Snails: Identification and Distribution of Biomphalaria, Bulinus, and Oncomelania Species (Charlottenlund: Danish Bilharziasis Laboratory).

11

Campbell A. C. Madsen H. Kristensen T. K. (2025). Effects of salinity on survival and reproduction of Biomphalaria pfeifferi and implications for schistosomiasis transmission. J. Trop. Ecol.41, 145–153. doi: 10.1017/S0266467425000123

12

DeJong R. J. Morgan J. A. T. Paraense W. L. Pointier J. P. Amarista M. Ayeh-Kumi P. F. et al . (2001). Evolutionary relationships and biogeography of Biomphalaria (Gastropoda: Planorbidae). Mol. Biol. Evol.18, 2225–2239. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a003769

13

Erkano D. (2021). Influence of physicochemical water parameters on the distribution of Biomphalaria snails in Ethiopian freshwater bodies. Afr. J. Aquat. Sci.46, 289–298. doi: 10.2989/16085914.2021.1945678

14

Esteban J. G. Muñoz-Antoli C. Trelis M. Toledo R. (2011). Effects of nonschistosome larval trematodes on biomphalaria snails. Biomphalaria Snails Larval Trematodes, 127–157. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-7028-2_6

15

Frandsen F. Christensen N.Ø. (1984). An introductory guide to the identification of cercariae from African freshwater snails with special reference to cercariae of trematode species of medical and veterinary importance (Charlottenlund: Danish Bilharziasis Laboratory).

16

Fried B. Huffman J. E. (2009). The biology of the caecal trematode Zygocotyle lunata. Adv. Parasitol.69, 1–40. doi: 10.1016/S0065-308X(09)69001-4

17

Gichuki J. Mwaura L. Mwandawiro C. (2019). Epidemiology of schistosomiasis in Kenya: Current status and future prospects. Acta Tropica199, 105–112. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2019.105112

18

Hailegebriel T. Nibret E. Munshea A. (2022). Distribution and seasonal abundance of Biomphalaria snails and their infection status with Schistosoma mansoni in and around Lake Tana, northwest Ethiopia. Sci. Rep.12, 17055. doi: 10.1038/S41598-022-21306-0

19

Hamburger J. (2017). Molecular monitoring of Schistosomiasis transmission. Ann. Clin. Cytology Pathol.3, 1087. doi: 10.29011/2475-9430.100087

20

Handzel T. Karanja D. M. Addiss D. G. Hightower A. W. Rosen D. H. Colley D. G. et al . (2003). Geographic distribution of schistosomiasis and soil-transmitted helminths in western Kenya: Implications for integrated control. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hygiene69, 231–238. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2003.69.231

21

Hotez P. J. Harrison W. Fenwick A. Bustinduy A. L. Ducker C. Mbabazi P. S. et al . (2019). Female genital schistosomiasis and HIV/AIDS: Reversing the neglect of girls and women. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis.13, e0007025. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0007025

22

Joof E. Andrus P. S. Sowunmi K. Onyango V. M. Wade C. M. (2020). Comparing PCR techniques against conventional cercarial shedding methods for detecting Schistosoma mansoni infection in Biomphalaria snails. Acta Tropica212, 105716. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2020.105716

23

Kalinda C. Chimbari M. J. Mukaratirwa S. (2018). Schistosomiasis in Zambia: A systematic review of past and present experiences. Infect. Dis. Poverty7, 41. doi: 10.1186/s40249-018-0424-5

24

Kane R. A. Rollinson D. Stothard J. R. (2008). Molecular approaches to the identification of snail intermediate hosts for schistosomes in Africa. Acta Tropica108, 140–147. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2008.09.001

25

Kanyi H. Kihoro R. W. Chieng B. Araka S. Emisiko H. Ramos T. et al . (2024). Direct isolation of Schistosoma mansoni DNA from stool samples for molecular diagnostics. J. Parasitol. Res.2024, 1–8. doi: 10.1155/2024/9876543

26

Kihara J. H. Muhoho N. Njomo D. Mwobobia I. K. Josyline K. Mitsui Y. et al . (2007). Drug efficacy of praziquantel and albendazole in school children in Mwea Division, Central Province, Kenya. Acta Tropica102, 165–171. doi: 10.1016/J.ACTATROPICA.2007.04.017

27

Kristensen T. K. Malone J. B. McCarroll J. C. (2001). Use of satellite remote sensing and geographic information systems to model the distribution and abundance of snail intermediate hosts in Africa: a preliminary model for Biomphalaria pfeifferi in Ethiopia. Acta Tropica79, 73–78. doi: 10.1016/S0001-706X(01)00104-8

28

Laidemitt M. R. Anderson L. C. Wearing H. J. Mutuku M. W. Mkoji G. M. Loker E. S. (2019). Antagonism between parasites within snail hosts impacts the transmission of human schistosomiasis. ELife8. doi: 10.7554/eLife.50095

29

Leicht K. Seppälä O. (2014). Infection success of Echinoparyphium aconiatum (Trematoda) in its snail host under high temperature: role of host resistance. Parasites Vectors7, 192. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-7-192

30

Lu L. Bu L. Laidemitt M. R. Zhang S.-M. Loker E. S. (2024). Different metazoan parasites, different transcriptomic responses, with new insights on parasitic castration by digenetic trematodes in the schistosome vector snail Biomphalaria glabrata. BMC Genomics25, 608. doi: 10.1186/s12864-024-10454-4

31

Marcilla A. Trelis M. Cortés A. Sotillo J. Cantalapiedra F. Minguez M. T. et al (2012). Extracellular vesicles from parasitic helminths contain specific excretory/secretory proteins and are internalized in intestinal host cells. PLoS ONE7 (9), e45974.

32

Magero V. O. Kisara S. Suleman M. A. Wade C. M. (2025). Distribution of the schistosome intermediate snail host Biomphalaria pfeifferi in East Africa and prevalence of Schistosoma mansoni infection. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hygiene119, 253–265. doi: 10.1093/trstmh/trae115

33

Mahya A. Singh P. (2022). Experimental and modeling study of water-retention behavior of fine-grained soils with dual-porosity structures. Acta Geotechnica17, 1341–1361. doi: 10.1007/s11440-022-01483-y

34

Mangal T. D. Paterson S. Fenton A . (2008). Host–parasite interaction rates increase with temperature: Experimental evidence with Schistosoma mansoni and Biomphalaria alexandrina. J. Exp. Biol.211, 1433–1437. doi: 10.1242/jeb.014685

35

Masaku J. Mutungi F. Mwangi J. Njenga S. M. (2015). High prevalence of schistosomiasis in Mwea irrigation scheme, Kirinyaga County, Kenya. Acta Tropica150, 135–140. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2015.07.024

36

Masaku J. Njomo D. W. Njoka A. Okoyo C. Mutungi F. M. Njenga S. M. (2020). Soil-transmitted helminths and schistosomiasis among pre-school age children in a rural setting of Busia County, Western Kenya: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health20, 84. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-08485-z

37

McCreesh N. Booth M. (2014). The effect of simulating different intermediate host snail species on the link between water temperature and schistosomiasis risk. PloS One9, e87892. doi: 10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0087892

38

McCreesh N. Nikulin G. Booth M. (2015). Predicting the effects of climate change on Schistosoma mansoni transmission in eastern Africa. Parasites Vectors8, 4. doi: 10.1186/S13071-014-0617-0

39

Mereta S. T. Abaya S. W. Tulu F. D. Takele K. Ahmednur M. Melka G. A. et al . (2019). Environmental determinants of snail abundance and schistosomiasis transmission in Ethiopia. Parasites Vectors12, 609. doi: 10.1186/s13071-019-3866-3

40

Monde C. Syampungani S. van den Brink P. J . (2016). Environmental factors influencing Biomphalaria snail distribution in Zimbabwe. Parasites Vectors9, 112. doi: 10.1186/s13071-016-1389-1

41

Moret-Fernández D. López M. V. (2019). Soil porosity determination using the saturation method: A simple and accurate approach. Geoderma337, 1119–1126. doi: 10.1016/j.geoderma.2018.11.021

42

Mutuku M. W. Laidemitt M. R. Spaan J. M. Mwangi I. N. Ochanda H. Steinauer M. L. et al . (2021). Comparative vectorial competence of Biomphalaria Sudanica and B. choanomphala from transmission hotspots in Lake Victoria, Kenya. J. Parasitol.107, 349–357. doi: 10.1645/20-138

43

Ngigi D. M. Kirui S. C. Wajala F. M. E. Oyaro N. Mwangi S. (2019). Susceptibility of Biomphalaria spp. from Mwea Irrigation Scheme in Kenya against Schistosoma mansoni miracidia infection. J. Biomed. Sci. Eng.12, 477–486. doi: 10.4236/jbise.2019.1211039

44

Nwoko O. E. Mogaka J. J. O. Chimbari M. J. (2021). Challenges and opportunities presented by current techniques for detecting schistosome infections in intermediate host snails: A scoping review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health18, 5403. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18105403

45

Odero S. O. Ogonda L. Sang D. Munde E. O. Shiluli C. (2024). Distribution of Biomphalaria snails and schistosome infection prevalence along Mbita shoreline, Lake Victoria, Kenya. Trop. Med. Health52, 12. doi: 10.1186/s41182-024-00191-5

46

Odiere M. R. Rawago F. O. Ombok M. Secor W. E. Karanja D. M. S. Mwinzi P. N. M. et al (2012). High prevalence of schistosomiasis in Mbita and its adjacent islands of Lake Victoria, western Kenya. Parasites & Vectors5, 278.

47

Odongo-Aginya E. Eshita Y. (2008). Effect of seasonal rainfall and environmental changes on snail density and infection rates with Schistosoma mansoni in Entebbe, Uganda. East Afr. Med. J.85, 432–438.

48

Olkeba B. K. Boets P. Mereta S. T. Yeshigeta M. Akessa G. M. Ambelu A. et al . (2020). Environmental and biotic factors affecting freshwater snail intermediate hosts in the Ethiopian Rift Valley region. Parasites Vectors13, 292. doi: 10.1186/S13071-020-04163-6

49

Onyango D. A. Anyango O. Wamukota P. Wango T. Mukabana W. R. (2022) in A malacology survey to map schistosomiasis transmission sites on Mageta Island, Siaya County (Nairobi, Kenya (University of Nairobi): M.Sc. thesis, University of Nairobi).

50

Ogongo P. Nyakundi R. K. Chege G. K. Ochola L. (2022). The road to elimination: Current state of schistosomiasis research and progress towards the end game. Front. Immunol.13, 846108. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.846108

51

Ostrowski de Núñez M. Davies D. Spatz L. (2011). The life cycle of Zygocotyle lunata (Trematoda, Paramphistomoidea) in the subtropical region of South America. Rev. Mex. Biodivers.82, 581–588. doi: 10.22201/ib.20078706e.2011.2.470

52

Ostrowski de Núñez M. Spatz L. González Cappa S. M. (2003). New intermediate hosts in the life cycle of Zygocotyle lunata in South America. J. Parasitol.89, 193–194. doi: 10.1645/0022-3395(2003)089[0193:NIHITL]2.0.CO;2

53

Paradis E. Claude J. Strimmer K. (2004). APE: Analyses of phylogenetics and evolution in R language. Bioinformatics20, 289–290. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg412

54

Pfukenyi D. M. Mukaratirwa S. (2018). Amphistome infections in domestic and wild ruminants in East and Southern Africa: A review. Onderstepoort J. Veterinary Res.85, a1584. doi: 10.4102/ojvr.v85i1.1584

55

Pires R. Loker E.S. Paraense W.L. Monteiro D. Coelho P.M. Caldeira R.L. et al . (2023). Molecular characterization of Schistosoma mansoni miracidia and intermediate host snails from Brazil using multigene approaches. Curr. Res. Parasitol. Vector Borne Dis.3, 100133. doi: 10.1016/j.crpvbd.2023.100133

56

Poulin R. Mouritsen K. N. (2006). Climate change, parasitism and the structure of intertidal ecosystems. J. Helminthology80, 183–191. doi: 10.1079/JOH2006341

57

Rollinson D. Stothard J. R. Southgate V. R. (2011). Biomphalaria: Natural history, ecology and schistosome transmission (Geneva, Switzerland: Springer).

58

Rowel C. Fred B. Betson M. Sousa-Figueiredo J. C. Kabatereine N. B. Stothard J. R. (2015). Environmental epidemiology of intestinal schistosomiasis in Uganda: population dynamics of biomphalaria (gastropoda: planorbidae) in Lake Albert and Lake Victoria with observations on natural infections with digenetic trematodes. BioMed. Res. Int.2015, 11. doi: 10.1155/2015/717261

59

Salloum P. M. Jorge F. Poulin R. (2023). Different trematode parasites in the same snail host: Species-specific or shared microbiota? Mol. Ecol.32, 4312–4324. doi: 10.1111/mec.17111

60

Sokouri D. P. Ouattara M. Yao K. P. Coulibaly J. T. (2024). Impact of environmental factors on Biomphalaria pfeifferi vector capacity leading to human infection by Schistosoma mansoni in western Côte d’Ivoire. Parasites Vectors17, 88. doi: 10.1186/s13071-024-06588-9

61

Spatz L. Cappa S. M. G. De Núñez M. O. (2012). Susceptibility of wild populations of Biomphalaria spp. from neotropical South America to Schistosoma mansoni and interference of Zygocotyle lunata. J. Parasitol.98, 1291–1295. doi: 10.1645/GE-3002.1

62

Steinauer M.L. Hanelt B. Mwangi I.N. Maina G.M. Agola L.E. Kinuthia J.M. et al . (2008). Introgressive hybridization of human and rodent schistosome parasites in western Kenya. Mol. Ecol.17, 5062–5074. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2008.03957.x

63

Steinmann P. Keiser J. Bos R. Tanner M. Utzinger J. (2006). Schistosomiasis and water resources development: Systematic review, meta-analysis, and estimates of people at risk. Lancet Infect. Dis.6, 411–425. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(06)70521-7

64

Toledo R. Muñoz-Antolí C. Esteban J. G. (2015). Strongyloidiasis with emphasis on human infections and its different clinical forms. Adv. Parasitol.88, 165–241.

65

Upatham E. S . (1973). The effect of water temperature on the penetration and development of St. Lucian Schistosoma Mansoni Miracidia in local Biomphalaria Glabrata. Southeast Asian J. Trop. Med. Public Health, 4(3), 367–370.

66

Upatham E. S. (1972b). Effects of salinity on the survival of Schistosoma mansoni miracidia and on infection of Biomphalaria glabrata. J. Parasitol.58, 889–892. doi: 10.2307/3278373

67

Vale N. Gouveia M. Rinaldi G. Brindley P. J. Gärtner F. Correia da Costa J. M. (2017). Praziquantel for schistosomiasis: Single-drug metabolism revisited, mode of action, and resistance. Antimicrobial Agents Chemotherapy61. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02582-16

68

Vanderkelen I. van Lipzig N. P. M. Thiery W. (2018). Modelling the water balance of Lake Victoria. Hydrology Earth System Sci.22, 5509–5525. doi: 10.5194/hess-22-5509-2018

69

Woolhouse M. E. J. Chandiwana S. K. (1990). The epidemiology of schistosome infections of snails: taking the theory into the field. Parasitol. Today6, 65–70. doi: 10.1016/0169-4758(90)90211-L

70

World Health Organization (2013). Schistosomiasis progress report 2001–2011 (Geneva, Switzerland: WHO). Available online at: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/174735 (Accessed September 20, 2025).

71

World Health Organization . (2022). FioSchisto’s expert perspective on implementing WHO guidelines for schistosomiasis control and transmission elimination in Brazil. Front. Immunol.14. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1268998

72

World Health Organization . (2022). World health statistics 2022: Monitoring health for the SDGs, sustainable development goals. World Health OrganizationGeneva.

73

Zhang L.-J. Xu Z.-M. Guo J.-Y. Dai S.-M. Dang H. Lü S. et al (2019). Endemic status of schistosomiasis in the People's Republic of China in 2018. Chinese J. Schistosomiasis Control31 (6), 576–582.

Summary

Keywords

Biomphalaria snails, environmental factors, host–parasite dynamics, Lake Victoria, Mwea Irrigation Scheme, trematodes

Citation

Parsimei FN, Nyanjom SG, Akinyi MY, Ogara G, Ngudi C, Karanja PK, Odiere MR and Ochola L (2026) Ecological influences on host–parasite dynamics among Biomphalaria snails in two schistosomiasis endemic regions of Kenya. Front. Parasitol. 5:1729760. doi: 10.3389/fpara.2026.1729760

Received

21 October 2025

Revised

16 January 2026

Accepted

16 January 2026

Published

10 February 2026

Volume

5 - 2026

Edited by

Samson Mukaratirwa, Ross University School of Veterinary Medicine, Saint Kitts and Nevis

Reviewed by

Muhammad Imran, University of Agriculture, Faisalabad, Pakistan

Shabani Ekyamba, University of Goma, Democratic Republic of Congo

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Parsimei, Nyanjom, Akinyi, Ogara, Ngudi, Karanja, Odiere and Ochola.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Florence N. Parsimei, parsimeif@gmail.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.