Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has led to millions of deaths. Although the pandemic state has been declared to have ended and the disease has become endemic, the number of circulating SARS-CoV-2 variants and the lack of decreasing trends around the world highlight the challenge the virus still poses. The viral RNA genome contains several structural elements including G-quadruplexes. These structures may facilitate the binding between an RNA and RNA-binding proteins. Herein, we investigated host cell proteins that get trapped by a G-quadruplex structure of the SARS-CoV-2 RNA. The identified proteins include the human DNA topoisomerase 1 (TOP1). The protein is known to interact with G-quadruplex-DNA, but here, we show an interaction with a G-quadruplex structure formed by the RNA of SARS-CoV-2, which has not been reported before. TOP1 may be recruited by the non-canonical secondary structure to resolve it, which may enhance viral replication. Interestingly, previous studies showed that TOP1 inhibition can suppress SARS-CoV-2-induced inflammation. Thus, after discovery of TOP1 as a binding partner of the SARS-CoV-2 G-quadruplex structure, we tested different compounds for their effect on the recruitment of TOP1 to the G-quadruplex. Notably, our data suggest that the known alkaloid berberine can stabilize the TOP1-G4-RNA-complex. Functionally, TOP1 is possibly recruited by the G-quadruplex to resolve this secondary structure, thereby enhancing viral replication. Thus, berberine is a promising lead compound that may inhibit viral replication.

1 Introduction

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is the pathogen responsible for the coronavirus disease 19 (COVID-19) pandemic that emerged at the end of 2019 (Hu et al., 2021; Zhu et al., 2020). SARS-CoV-2 is a beta-coronavirus with a genome consisting of a positive RNA strand, which is approximately 30 kb long (Lu et al., 2020; Maiti, 2022). This genome encodes 29 proteins: 25 putative non-structural and accessory proteins and four structural proteins (Zhou et al., 2020a; Zhou et al., 2020b). While the structural proteins spike (S), envelope (E), membrane (M), and nucleocapsid (N) play a role in assembly of the virus particle, the non-structural proteins (NSPs) are essential for viral RNA replication and immune evasion. The accessory proteins have diverse functions associated with viral infection, survival, and transmission in the host cells (Yoshimoto, 2020; Gordon et al., 2020; Thomas, 2021). During viral infection, the spike protein interacts with the host cell receptor hACE2 followed by the uptake of the virus into the host cell (V'Kovski et al., 2021). Then the virus releases its RNA genome into the cytosol, where it is then translated by the host cell’s translation machinery.

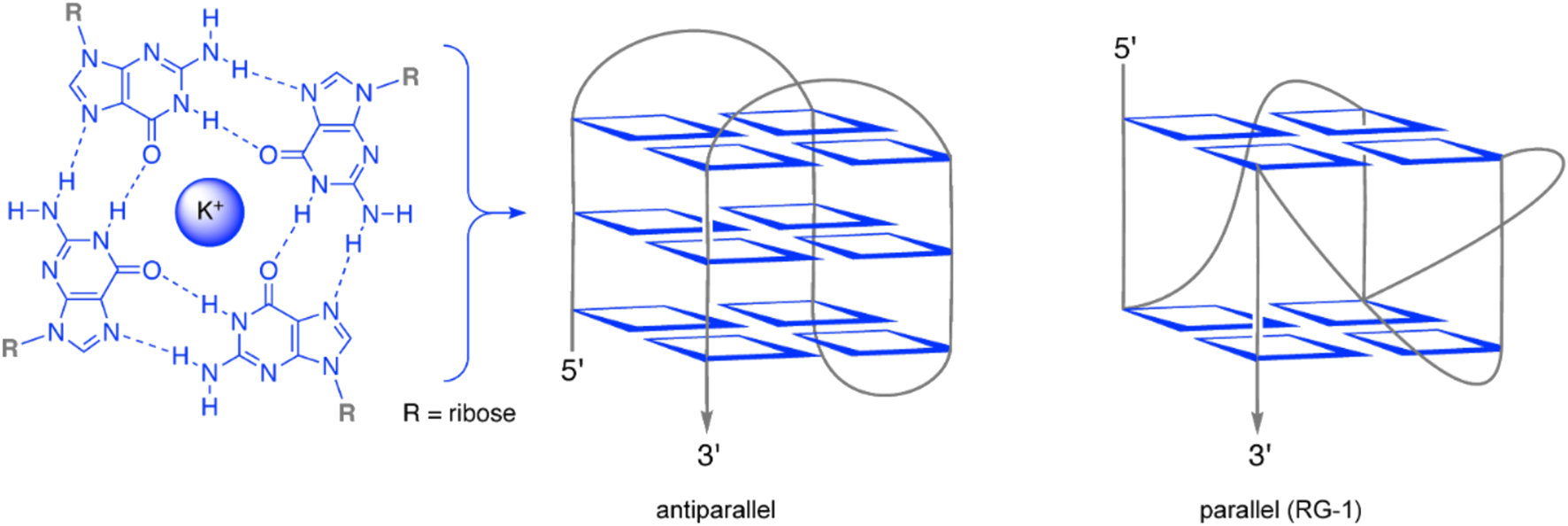

In cells, RNA can adopt diverse secondary and tertiary structures, which are recognition motifs for RNA-binding proteins. Along with the regular single-stranded and duplex RNA structures, quadruplex structures are also assembled from specific RNA sequences, usually referred to as G4-RNA (Lyu et al., 2021; Wu et al., 2025). Formation of guanine tetrads was first described by Gellert et al. (1962). Specifically, G4-RNA structures are formed in guanine-rich RNA regions, whose guanosine residues of four opposing strands form base quartets through Hoogsteen hydrogen bonding and additional complexation of cations, such as K+ (Figure 1). The stacking of two or more of these quartets leads to the central quadruplex structure, whose ends are connected by loops with varying length and sequence, which, in turn, have a significant influence on the actual quadruplex structure (Bisoi and Singh, 2025; Pandey et al., 2013) (Figure 1). G-quadruplexes can regulate gene expression at diverse steps, including pre-mRNA maturation, mRNA transport, RNA localization, RNA stability, and translation (Rouleau et al., 2018; Sauer et al., 2019; Beaudoin and Perreault, 2013; Schult et al., 2024; Song et al., 2023). Additionally, G-quadruplexes in telomeric repeat-containing RNA (TERRA) or at DNA/RNA hybrid structures (R-loops) can modulate telomere elongation, DNA replication, and recombination (Kumar et al., 2021; De Magis et al., 2019; Biffi et al., 2012; Mei et al., 2021; Miglietta et al., 2020). And all these cellular functions are driven by the interaction of RNA-binding proteins with the G-quadruplex-RNA. To add to that, G-quadruplexes can also influence viral replication, transcription, and translation. Thus, these sequence-specific motifs may be a promising target for antiviral drugs (Maiti, 2022; Liu et al., 2022; De Magis et al., 2024; Ruggiero and Richter, 2018).

FIGURE 1

Schematic presentation of a guanine quartet (blue) and sketches of exemplary quadruplex RNA (G4-RNA) structures (parallel and antiparallel refer to the relative orientation of the RNA strand in the quadruplex). Graphics were created using Biorender.com.

Different G-quadruplex sequences were reported for SARS-CoV-2 consisting of transiently formed as well as stable G-quadruplexes (Belmonte-Reche et al., 2021; Ji et al., 2021). The best stability scores could be achieved for a parallel G-quadruplex structure (Figure 1) referred to as RG-1 and its longer version L-RG1 (Maiti, 2022; Lavigne et al., 2021; Zhao et al., 2021). This RNA motif is located within the coding sequence of the N-protein of SARS-CoV-2 and forms an intramolecular G-quadruplex structure with two G-tetrad layers. RG-1 and L-RG1 form stable G-quadruplexes in living cells and in vivo (Zhao et al., 2021). Moreover, the translation of the viral N protein significantly decreases in samples containing the G-quadruplex motif, when compared to samples that do not form a G-quadruplex within the coding sequence of the N protein (Zhao et al., 2021). Many predictions about these putative G-quadruplex-forming sequences have been published; yet a clear understanding of their 3D structures and folding dynamics is still lacking in most cases, especially considering the almost complete lack of knowledge about their folding in vivo (Zhai et al., 2022). What has been found, however, is that G-quadruplexes in SARS-CoV-2 can be targeted by small-molecule compounds and natural products to regulate the virus’ gene expression and to detect its presence (Zhai et al., 2022).

A better understanding of how these secondary structures facilitate their effects and which host cell proteins are recruited by them is essential for the development of lead structures of more effective anti-coronaviral drugs. Thus, in this study we aimed at the identification of host cell proteins that are recruited by the viral L-RG1 RNA G-quadruplex. The identified proteins include the human DNA topoisomerase 1 (TOP1). TOP1 has been traditionally known as a DNA-regulating enzyme affecting the DNA’s topological state by relieving torsional stress during DNA replication and transcription. It creates transient single-strand breaks in the DNA, allowing the DNA to rotate and unwind, then resealing the break. Besides introducing single-strand breaks and subsequent re-ligation, TOP1 also recruits other enzymes with a helicase activity, e.g., the Werner helicase, which can resolve secondary DNA structures (Berroyer and Kim, 2020). In line with this function, TOP1 prevents the formation of G-quadruplex structures in DNA, which was shown to protect the cell from genotoxic effects of G-quadruplex-binding small molecules (Berroyer and Kim, 2020; Zyner et al., 2019; Yadav et al., 2014; Yadav et al., 2016). Interestingly, recent reports show that TOP1 does not only bind to G-quadruplexes in DNA, but also in RNA (Marchand et al., 2002; Luige et al., 2024).

In this study, we show that TOP1 binds to the viral L-RG1 RNA G-quadruplex, which may implicate TOP1 as a possible regulator of the G-quadruplex RNA. Further, our data suggests that the alkaloid berberine efficiently interacts with the TOP1-G-quadruplex complex, making it a possible lead compound to inhibit G-quadruplex-regulated viral replication.

2 Methods

2.1 RNA pull-down

2 x 106 (Zhou et al., 2020b) HEK293T cells were seeded in 75 cm2 cell culture flasks and incubated at 37 °C and 8% CO2. After 72 h the cells were harvested and lysed by sonication. After lysis, cell debris was removed by centrifugation (10 min, 12,000 x g, 4 °C). The two RNA oligonucleotides, the wild-type L-RG-1 and the mutant, which does not form a G-quadruplex structure (L-RG-1: 5′-AGAAUGGCUGGCAAUGGCGGUGAUG-3’; L-RG-1-Mut: 5′-AGAAUGACUGACAAUGACGAUGAUG-3), were folded by incubation in RNA structure buffer (10 mM TRIS pH 7, 10 mM MgCl2, 100 mM KCl) at 72 °C for 10 min and slow cooling to RT. Thermo Scientific™ Pierce™ High-Capacity Streptavidin-Agarose Bead Resin was washed using washing buffer (25 mM Tris pH 7.4, 15 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate) and then resuspended in Buffer A (20 mM Tris pH 7.4, 300 mM KCl, 0.2 mM EDTA, 1.5 mM MgCl2, Pierce™ protease inhibitor). 200 pmol RNA oligo per sample were mixed with 500 µg of protein lysate and 200 µL of Buffer A, followed by an incubation at RT for 1 h, rotating. 20 μL of the high-capacity beads were added per sample. The samples were incubated for 2 h at RT, rotating. Then the beads were washed two times with 1 mL of washing buffer to remove unbound proteins.

2.2 NMM gel-based assay

Both RNA oligonucleotides described above were folded by incubation in RNA structure buffer (10 mM TRIS pH 7, 10 mM MgCl2, 100 mM KCl) at 72 °C for 10 min and slowly cooled to RT. A 15% TBE native gel was pre-run for 15 min at 80 V. After cooling, 2.5 µg of each oligo were mixed with 6X Gel Loading Dye without SDS (New England Biolabs) and loaded on the gel. Electrophoresis ran at 80 V for 90 min. The gel was incubated under shaking in the dark with 10 μg/mL NMM in 1x RNA structure buffer for 15 min. NMM (N-methyl mesoporphyrin IX) is a a highly selective light-up probe for G-quadruplex DNA (Yett et al., 2019). Visualization was performed with the iBright (Invitrogen). After visualization, the gel was washed in water for 15 min under shaking. Subsequently, nucleic acid staining was performed by incubating the gel in Ethidiumbromide and imaging it with the iBright (Invitrogen).

2.3 Mass spectrometry analysis

The beads from the RNA pulldown described above were washed twice with PBS. Five biological replicates of each sample were analyzed. Samples were reduced with DTT (15 mM), alkylated with Iodoacetamide (55 mM) and processed using magnetic beads (Cytiva Sera-Mag SpeedBeadsTM Carboxyl Magnetic Beads) as previously described (Hughes et al., 2019). Samples were analyzed on a timsTOF Pro coupled to a nanoElute nanoUPLC. Resuspended peptides in 0.1% formic acid (FA) were separated on a BrukerTEN column (10 cm length, 75 µm internal diameter, 1.9 µm particle size) using a 30 min linear gradient from 2% to 40% Buffer B (Buffer B: 99.9% Acetonitrile (ACN)/0.1%FA). The timsTOF Pro was operated in a DDA-PASEF mode covering an IM range from 0.85 to 1.30 1/K0. Accumulation and ramp time were set to 100 ms achieving a 100% duty cycle. Searches were performed using MaxQuant (2.0.1.0) against the human database, setting carbamidomethylation of cysteines (+57 Da) as a fixed modification, oxidation of methionine (+16 Da) and acetylation of the N-terminal (+42 Da) as variable modifications. FDR for protein and peptide identification was set to 0.01. The resulting data were analyzed using R (www.r-project.org). The samples were analyzed in pairs and the significantly enriched proteins were identified using the Welch T-test, corrected for multiple testing using the Benjamini-Hochberg correction. Proteins were reported with different p-value cutoffs applied (Supplementary Datasheet 2). To include proteins that were only identified in two samples an medium imputation was used and the same statistical analysis was performed (Supplementary Datasheet 2).

2.4 Western blots

The beads from the RNA pulldown describe above were resuspended in 2x sample buffer (48% Urea, 15 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 8.7% Glycerine, 1% SDS, 0.004% Bromophenolblue, 143 mM Mercaptoethanol). The samples were denatured at 95 °C for 10 min and SDS-PAGE was performed using a 10% polyacrylamide gel. The bands were blotted onto a nitrocellulose membrane, which was then blocked in 5% BSA in TBST for 30 min at RT. After blotting the membrane was incubated with the primary TOP1 antibody (Monoclonal mouse IgG targeting the N-terminal region of TOP1, 1:1,000 in TBST) ON at 4 °C, rolling. The membrane was washed 3 times with TBST to remove excess primary antibody and incubated ON at 4 °C with the HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (1:1,000 in TBST). The membrane was washed again 3 times with TBST and detection of the bound secondary antibody was achieved by incubation with Pierce™ ECL substrate mix. Bands were detected with the iBright (Invitrogen). Band intensities were quantified with the iBright analysis software. Statistical analysis were either performed using unpaired t-test in case of pairwise comaprison, when comparing multiple conditions Friedman test was used for multiple comparisons.

2.5 Spectrometric titrations

The examined compounds 1a (Zee-Cheng and Cheng, 1972), 1b (Pithan et al., 2017), 3a (Nechepurenko et al., 2011), 3b (Wickhorst and Ihmels, 2021), 4 (Gra et al., 2009), 5 (Groß and Ihmels, 2022), 6 (Groß and Ihmels, 2022), and 7 (Wickhorst et al., 2021) were synthesized according to literature procedures. RHPS4 (2) was purchased from Selleckchem (Houston, TX, United States).

Absorption and emission spectra were recorded in Hellma half-micro or Hellma micro quartz cuvettes (length d = 10.0 mm), if not stated otherwise. All spectra were measured at a temperature of 20 °C.

Chemicals of biochemical purity were used for the buffer solutions. The buffer solutions were stored in the dark at 4 °C and used for a maximum duration of 3 months (Tris-HCl buffer) or 5 days (cacodylate buffer) (cf.Supplementary Material). Stock solutions of ligands 1–7 for spectroscopic measurements were prepared in concentrations of 1.00 mM or 0.10 mM in MeOH or MeCN and stored at 4 °C in the dark.

Solutions for titrations with the RG1 solution (cRG1 = 300 μM; RG1: GGCUGGCAAUGGCGG) were prepared in tris-HCl buffer from stock solutions of ligands 1–7 in a sample volume of 750 µL. To avoid a dilution effect, the ligand was also added to the RNA solution such that analyte and titrant solution have the same concentration. A volume of 10% DMSO (v/v) was added to both the RNA and the ligand solution to provide sufficient solubility.

At the start of the titration, an absorption and emission spectrum was recorded. Subsequently, RNA solution (cRG1 = 300 µM) was added, and an absorption and emission spectrum was recorded after every addition. The volume of added RNA solution was increased depending on the change of absorption. The sample was shaken after every addition and allowed to equilibrate for 2.5 min. Absorption spectra were recorded in a range of 280–700 nm at a scanning speed of 120 nm min–1. Emission spectra were recorded at the same scanning speed in a range of 360–800 nm with detector voltage of 400–800 V. If possible, the excitation wavelength corresponded to an isosbestic point as obtained from the photometric titration. The determination of binding constants from the binding isotherms resulting from the titrations is described in the Supplementary Material. Photometric and fluorimetric titrations were performed twice each to check for reproducibility. Polarimetric measurements were done once. Based on reported general error analysis of Scatchard plots (Granzhan et al., 2007), the error of the binding constants was estimated to be ±10% of the given values.

For CD-spectroscopic analysis, five samples with identical RNA concentration (cRG1 = 20.0 µM) and varying ligand concentrations (cL = 0.0–40.0 µM) were prepared in tris-HCl buffer with sample volumes of 300 µL (Supplementary Table S2).

For the determination of the RNA melting temperature, three samples with identical RNA concentration (cRG1FRET = 1.20 µM; RG1 FRET = FAM-GGCUGGCAAUGGCGG-TAMRA; FAM = 6-carboxyfluorescein, TAMRA = 5-carboxytetramethylrhodamin) and varying ligand concentrations (cL = 0.00–1.00 µM) were prepared in cacodylate buffer with 10% DMSO (v/v) in a sample volume of 1.00 mL (Supplementary Table S4). Samples were heated to 90 °C and slowly cooled to ensure proper folding of the oligonucleotide before being heated to 90 °C at 0.2 °C min–1 while the emission intensity was followed (cf.Supplementary Material). RNA melting temperature experiments were performed once.

2.6 Compound treatment of RNA pulldown samples

Four compounds were tested regarding their effects on the interaction: berberine (3a), tetraazoniapentaphenopentaphene (4), naphthyridinium (5), and naphthoquinolizinium (7). The compounds were added to the protein/RNA-mixture before the agarose beads were added. One sample containing the wild-type L-RG1 RNA and one sample containing the mutant RNA oligo was treated each, with a final concentration of 100 µM for all samples.

3 Results

3.1 Identification of host cell proteins binding to the SARS-CoV-2-G-quadruplex L-RG1

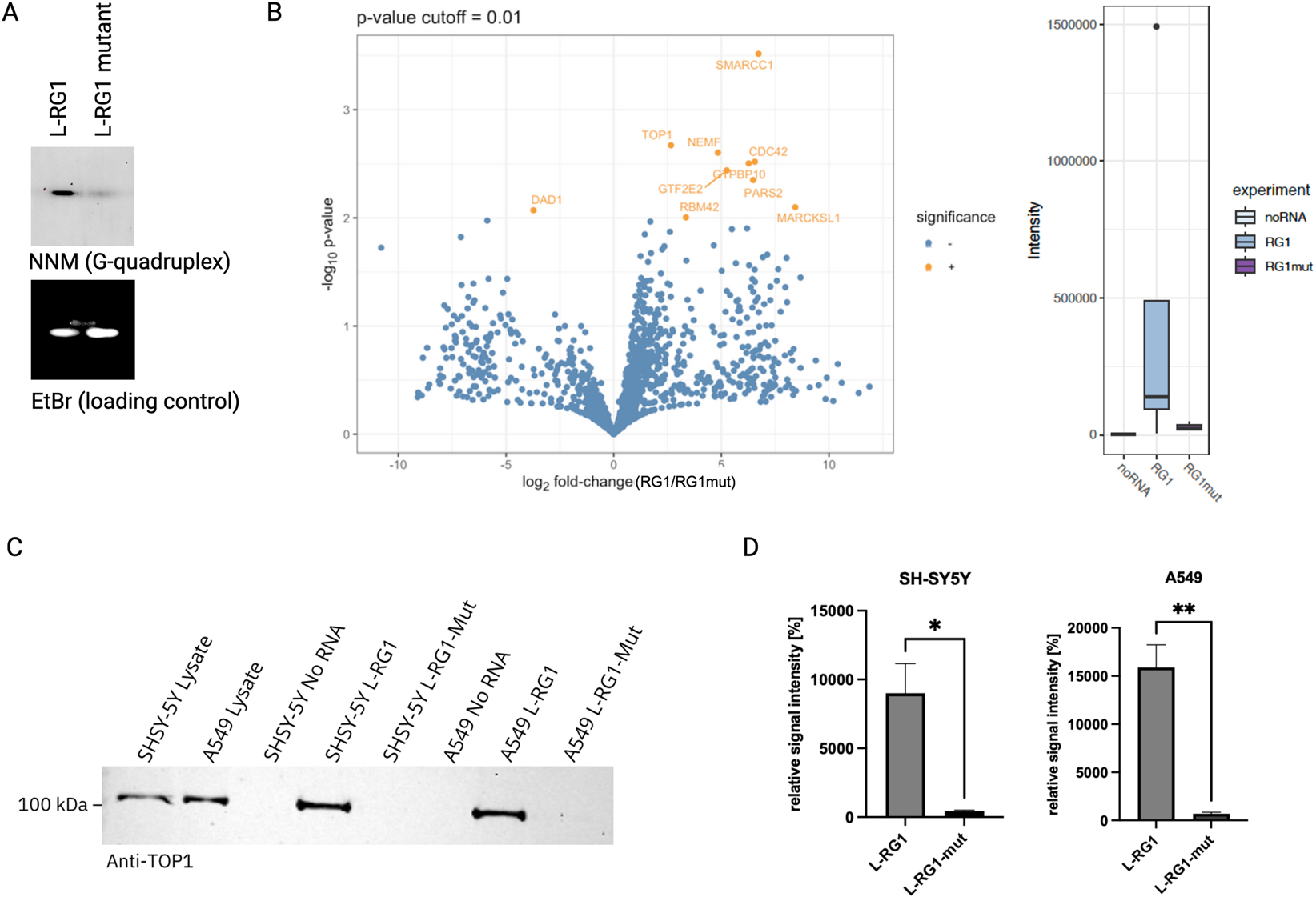

The goal of our first set of experiments was to identify host cell proteins that are recruited to the SARS-CoV2-RNA via its G-quadruplex structure L-RG1. Therefore, we performed an RNA-pulldown assay in which we immobilized biotinylated L-RG1-RNA oligos on streptavidin-beads. These RNA-coated beads were then incubated with protein extracts from HEK293T cells to allow RNA-protein binding. After extensive washing of the beads, the RNA-bound proteins were then analyzed by mass spectrometry. As negative controls we included samples in which the RNA-sequence of L-RG1 was mutated and samples without RNA. To confirm that the L-RG1-oligo indeed folds into a G-quadruplex structure, while mutant version does not, we performed a gel-based assay using N-methyl mesoporphyrin IX which is a highly selective light-up probe for G-quadruplexes (Figure 2A). In the following mass spectrometry analysis of RNA-bound preotins we identified 22 proteins that were significantly (p-value cut off 0.01) enriched in the L-RG1 sample when compared to the mutant L-RG1 negative control. Five of these proteins were significantly more abundant in the L-RG1-sample compared to both the no RNA control and the mutant L-RG1 control (Supplementary Table S1; Figure 2B, supplementary data sheet). Since one of the identified proteins, TOP1, has been previously linked to SARS-CoV2-RNA (Ho et al., 2021) we selected this protein for further analysis. Of note, DHX36, a known G-quadruplex interactor, was enriched in the L-RG1-sample sample (Figure 2B).

FIGURE 2

(A) NMM gel-assay. Native gel electrophoresis images showing that a G-quadruplex is present in L-RG1 but not in mutant L-RG1. Upper panel: samples stained with NMM to visualize G-quadruplex structures. Lower panel: counterstaining of the same gel with ethidium bromide (EtBr) as loading control. (B) Left: Volcano plot showing the differential protein enrichment in L-RG1 RNA pulldown samples compared to the noRNA control after data imputation. Proteins were identified using a timsTOF Pro in combination with a nanoUPLC. Quantification was performed using MaxQuant (2.0.1.0). Significance was determined using a p-value cutoff of 0.01, with significantly enriched proteins highlighted in orange. n = 5. Right: Binding profiles for DHX36, a known binder for G-quadruplex. Representation of binding intensity (control without RNA (noRNA), G-quadruplex binding (RG1) and binding to the mutated G-quadruplex (RG1mut)). (C) Validation of the mass spectrometry results by repeating the RNA pulldown assay with subsequent detection of TOP1 by Western blotting. The results confirm that TOP1 preferentially binds to the L-RG1 motif. (D) Quantification of the western blots shown in (C). Relative signal intensity incl. SEM is shown. Statistical analysis was done using unpaired t-test. *p = 0.0163; **p = 0.003; n = 3.

3.2 Validation of TOP1 as a binding partner of the SARS-CoV-2-G-quadruplex L-RG1

To validate our finding that TOP1 gets recruited to the L-RG1 G-quadruplex, we repeated the RNA pulldown assays using protein extracts from two different human cells lines (SH-SY5Y and A549) and detected TOP1 in the RNA-bound fractions on a Western blot. As expected, TOP1 was detected as a binder of the L-RG1 RNA (Figures 2C,D).

3.3 Identification of compounds binding to L-RG1 G-quadruplex structure

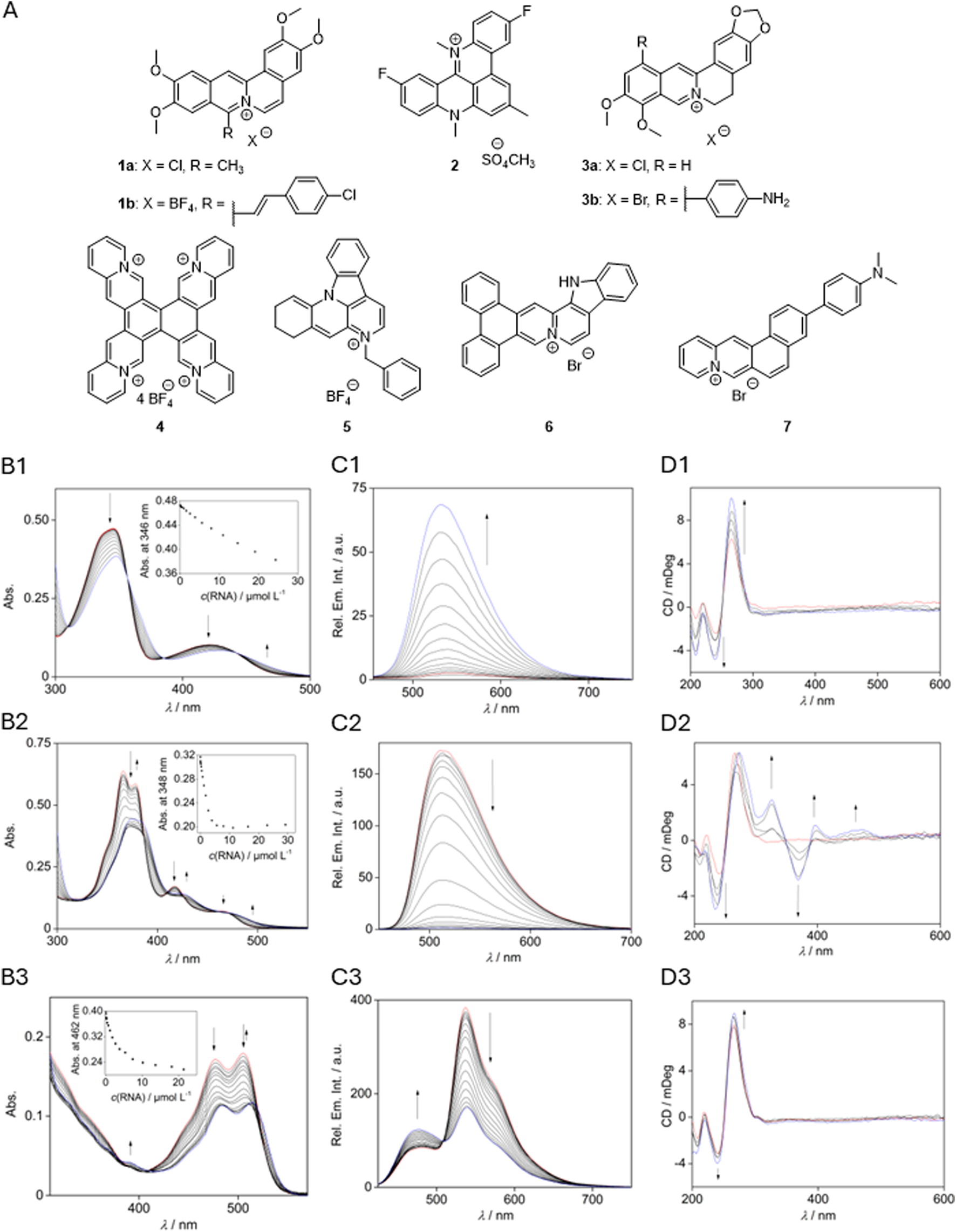

As it has been shown already that organic ligands may bind to SARS-CoV-2 RNA (Liu et al., 2022; Zhao et al., 2021; Sun et al., 2025; Qin et al., 2022a; Oliva et al., 2022; Qin et al., 2022b; Miclot et al., 2021), it was also explored whether this property may be employed to affect the RNA-protein interactions. Hence, in an exploratory screening, a small series of known G-quadruplex DNA ligands 1–7 (Pithan et al., 2017; Wickhorst and Ihmels, 2021; Gra et al., 2009; Groß and Ihmels, 2022; Wickhorst et al., 2021; Xiong et al., 2015; Leonetti et al., 2008) (Figure 3A) was tested for their propensity to bind to RG1 with photometric, fluorimetric, and polarimetric titrations as well as with RNA melting temperature analysis. It should be noted that berberine (3a) has been examined already along these lines (Oliva et al., 2022); however, this compound was also included to have a direct comparison with the other cationic isoquinolinium derivatives screened in this study.

FIGURE 3

(A) Compounds investigated as ligands for RG1 interactions. Photometric (B), fluorometric (C), and polarimetric (D) titrations with RG1 ((B,C)cRG1 = 285 µM with 5% v/v DMSO, (D)cRG1 = 20 µM) and berberine (3a; B1-D1) (Zee-Cheng and Cheng, 1972), tetraazoniapentaphenopentaphene (4; B2-D2) (Pithan et al., 2017), and naphthyridinium (5; B3-D3) (Nechepurenko et al., 2011). Red: spectrum before titration; blue: end of titration. Insets: absorption intensity at a specific wavelength plotted against the RNA concentration. Arrows indicate the change of intensity during the titration.

3.3.1 Photometric and fluorimetric RNA titration

In most cases, the addition of the oligonucleotide to a solution of the respective ligand led to a decrease of the long-wavelength absorption maxima and a slight red shift of the absorption maximum (Figure 3B, cf. Supplementary Material). As the only exceptions, the absorption increased during titration with the naphtho [1,2-b]quinolizinium (7), berberine (3a), and its derivative 3b. The fluorimetric titrations revealed a quenching of the fluorescence of compounds 1a, 1b, 4, and 7 in the presence of RNA, as indicated by the decrease of the relative fluorescence intensity, Ifl/I0,fl. Thus, at saturation the fluorescence of compounds 4 and 7 is strongly quenched (Ifl/I0,fl = 0.01 and 0.04) whereas the one of 1b is only quenched moderately (Ifl/I0,fl = 0.7) (Figure 3C; Supplementary Table S3). In contrast, the emission intensity of compounds 2, 3a, 3b, and 6 increased significantly in the presence of RNA by factors ranging from ca. 2 (2 and 6) to ca. 20 (3a and 3b). As the only outlier, the naphthyridinium (5) showed a strongly shifted new emission maximum at 477 nm upon addition of RNA, while the maximum at 537 nm decreased. The results from the photometric titrations were used to determine the binding constants of the ligand 4 (1.7 × 104 M–1) and berberine (3a) (1.0 × 105 M–1). The binding constants for compounds 1a, 1b, 6, and 7 could not be determined because the fitting curve did not converge (Supplementary Table S3).

3.3.2 CD-spectroscopic analysis

The CD spectrum of the oligonucleotide RG1 in Tris-HCl buffer exhibited characteristic positive bands with maxima at 219 nm and 265 nm and negative signals at 208 nm and 240 nm (Figure 3. D2). The intensity of these bands increased upon the addition of ligands 2, 3a, and 5 without a change of the general band structure. Only in the case of ligand 4, novel CD bands developed with increasing concentration of the ligand 4 in a solution of RG1. Specifically, positive induced CD (ICD) bands of the bound ligand were detected at 396 nm and 469 nm, and a negative ICD signal formed at 368 nm.

3.3.3 Thermal RNA denaturation analysis (FRET melting)

The binding interactions between compounds 1–7 and G4-RNA RG1were also examined by thermal RNA-denaturation analysis of the dye-labeled quadruplex-forming oligonucleotide FAM-GGCUGGCAAUGGCGG-TAMRA (RG1-FRET) (Mergny and Maurizot, 2001; De Cian et al., 2007). For that purpose, the effect of the ligands on the thermally induced unfolding of the dye-labeled quadruplex RG1-FRET was monitored by fluorescence spectroscopy, i.e., by following the extent of the Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) between the two dyes (Supplementary Table S4, cf. SI; Supplementary Figure S3). This method, often referred to as FRET melting, allowed the determination of a significantly increased RNA melting temperature of 6–11 °C when the oligonucleotide is in the presence of 1a, 2, 3a, or 7. No significant stabilizing effect was observed for ligands 4 and 5 and no meaningful data could be generated with compounds 1b, 3b, and 6, since the fitting curve for a Gaussian distribution of the first derivative did not converge in the latter cases.

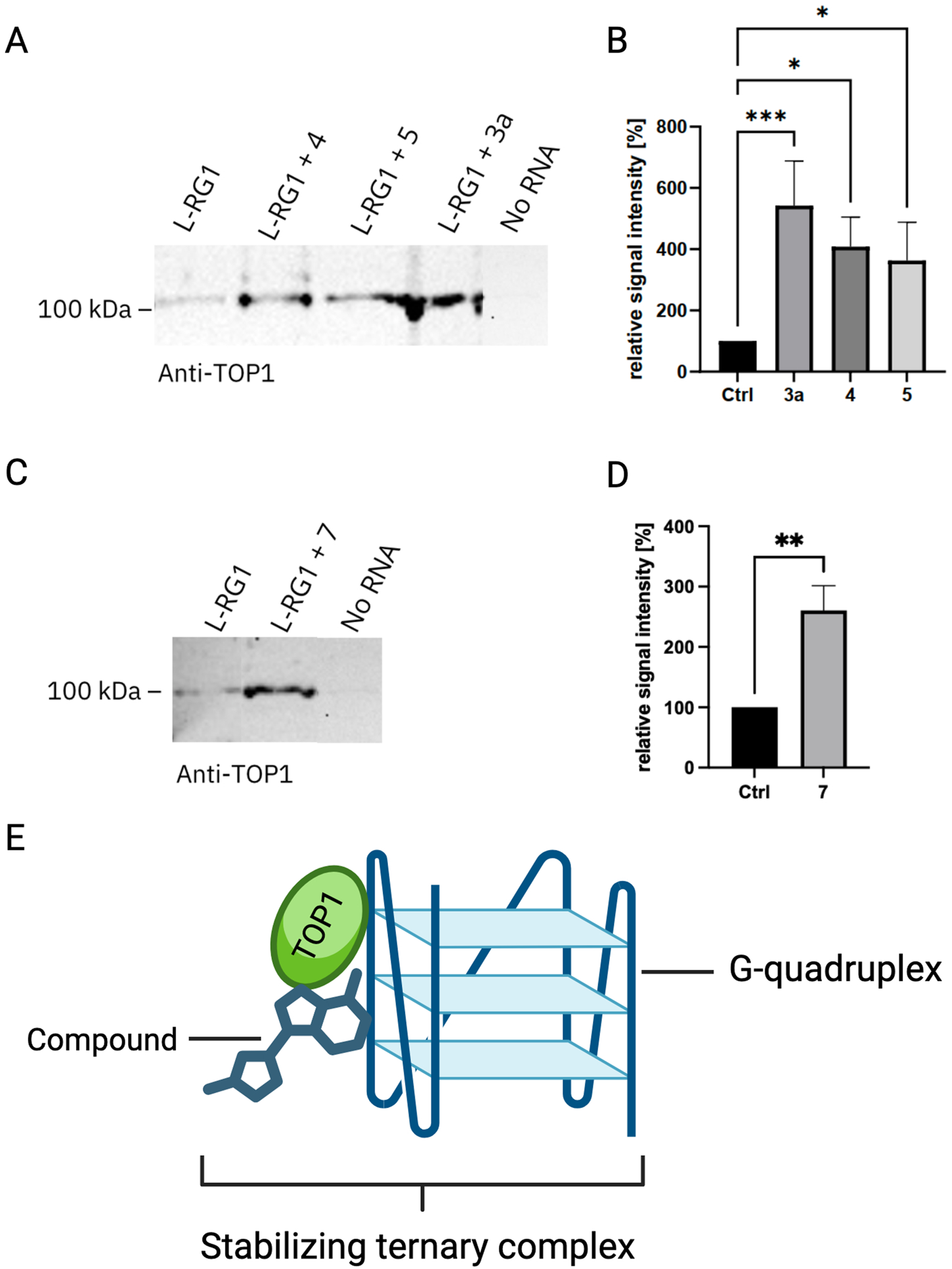

3.4 Analysis of L-RG1-binding compounds for their effect on TOP1 recruitment

Based on the spectroscopic assessment of the ligand-RNA interactions (cf. 3.3), the compounds 3a, 4, 5, and 7 were chosen for closer examination in further assays, because they exhibited the most promising RNA-binding properties. To test if the identified compounds affect the binding of TOP1 to the L-RG1 RNA, we performed RNA pulldown experiments in the presence or absence of the respective compounds (Figures 4A,C). Interestingly, berberine (3a), tetraazoniapentaphenopentaphene (4), naphthyridinium (5), and naphthoquinolizinium (7) increased the binding of TOP1 to the L-RG1 RNA motif significantly (Figures 4B,D).

FIGURE 4

Semiquantitative analysis of the change in relative signal intensity of the L-RG1 band upon treatment with different compounds. (A) Exemplary TOP1 blot showing the untreated control and three samples treated with the compounds tetraazoniapentaphenopentaphene (4), naphthyridinium (5), and berberine (3a) at a final concentration of 100 µM. (B) Quantification of the relative signal intensity incl. SEM. Statistical analysis was done using a Friedman test for multiple comparisons. ***p ≤ 0.0006; *p ≤ 0.04; n = 8. (C) Exemplary TOP1 blot showing the untreated control and a sample treated with dimethylaminonaphthochinolizinium (7) at a final concentration of 100 µM. (D) Quantification of the relative signal intensity incl. SEM. Statistical analysis was performed using unpaired t-test. *p ≤ 0.0312; n = 6. (E) Schematic of a ternary complex formation, facilitated by the interaction of TOP1, RNA-G-quadruplex and a chemical compound. This interaction might stabilize the G-quadruplex RNA, thereby exhibiting a possibly antiviral effect.

4 Discussion

Understanding the way how the RNA genome of SARS-CoV-2 interacts with the host cell proteome can not only provide detailed molecular insights into the cellular machinery that is affected during infection but can also suggest therapeutic targets. G-quadruplexes are secondary RNA structures that can mediate the attachment of RNA-binding proteins. G-quadruplexes influence viral infectivity and pathogenesis by regulating various steps of the virus lifecycle, viral transcription, replication, and virion production (Zareie et al., 2024). Here we investigated the host cell proteome that preferentially binds to the G-quadruplex motif L-RG1 of the SARS-CoV-2 genome. We detected 22 proteins that get recruited to L-RG1. While previous studies investigated the SARS-CoV2-RNA-binding host cell proteins for the complete RNA genome (Schmidt et al., 2021), our study focused on the G-quadruplex motif. The proteins detected by Schmidt et al. included RPS10, which we also found in our study, showing that the binding we observed in our study is reproducible in different experimental set-ups. The other proteins we detected in our study were not captured by Schmidt et al. This may be due to the fact that they used a different experimental set-up including another cell line (Huh7, a human liver cell line), which may express different levels of proteins.

In our experiments we identified TOP1 as an interesting protein that gets recruited to L-RG1. TOP1 has been traditionally known as a DNA-regulating enzyme affecting the DNA’s topological state by relieving torsional stress during DNA replication and transcription. It creates transient single-strand breaks in the DNA, allowing the DNA to rotate and unwind, then resealing the break. Besides introducing single-strand breaks and subsequent re-ligation, TOP1 also recruits other enzymes with a helicase activity, e.g., the Werner helicase, which can resolve secondary DNA structures (Berroyer and Kim, 2020). In line with this function, TOP1 prevents the formation of G-quadruplex structures in DNA, which was shown to protect the cell from genotoxic effects of G-quadruplex-binding small molecules (Berroyer and Kim, 2020; Zyner et al., 2019). Interestingly, our data identified TOP1 as a host cell protein that gets recruited to the L-RG1 G-quadruplex of the SARS-CoV-2 RNA genome. In line with this finding, recent reports show that TOP1 does not only bind to G-quadruplexes in DNA, but also in RNA (Marchand et al., 2002; Luige et al., 2024).

Our data show that TOP1 is recruited by the SARS-CoV-2 RNA motif L-RG1. The L-RG1 motive is located in the coding region of the viral N protein. Functionally, it is possible that TOP1 may resolve the G-quadruplex structure, which may result in decreased N translation and enhanced viral replication. Thus, the compound-induced strengthening of this bond may stabilize the G-quadruplex structure. Given the crucial role of G-quadruplexes in the viral lifecycle, G-quadruplex-stabilizing ligands to inhibit viral replication represent a promising antiviral strategy. However, this needs to be investigated further in future functional assays. Examples of G-quadruplex-ligands used to target the SARS-CoV-2 RNA genome include tetraphenylethene (TPE) derivatives, which stabilize the G-quadruplex and thereby reduce the protein level of N, finally suppressing the post-entry stages of viral replication (Gupta et al., 2025). Moreover, G-quadruplex binding substances such as PDP (pyridostatin derivative) stabilize L-RG1 and significantly reduce the protein level of N by inhibiting its translation both in vitro and in vivo (Zhao et al., 2021). The compounds tested in our study may have a comparable effect: they possibly stabilize the binding to TOP1, which then cannot linearize the G-quadruplex, resulting in reduced translation of the viral N protein. Thus, these compounds represent interesting candidates as antiviral drugs against COVID-19. In line with this, previous studies showed that TOP1 inhibition can suppress SARS-CoV-2-induced inflammation and thus represents a promising therapy against SARS-CoV-2 (Ho et al., 2021). Targeting of G-quadruplex structures bound to TOP1 is a promising approach, not only in viral infection, but also in other diseases, e.g., cancer. Here, a G-quadruplex in the promoter of the oncogene c-MYC is thought to act as transcriptional silencer. TOP1, by influencing this secondary structure, can activate c-MYC. Thus, downregulation of TOP1 results in decreased c-MYC expression (Keller et al., 2022). Interestingly, ligands targeting both TOP1 and the c-MYC G-quadruplex, stabilize the G-quadruplex structure, thereby inhibiting cancer cell growth (Hu and Lin, 2021; Han et al., 2024; Salerno et al., 2024).

We showed that most of the DNA ligands 1–7 bind to RG1. A shift in the absorption spectrum, hypochromicity, and a change of fluorescence are all indicative of an oligonucleotide-ligand interaction (Santos et al., 2021). These interactions were quantified by determining the binding constants of 3a and 4 and increased RNA melting temperatures, which are both in the range of the ones of moderate to good G-quadruplex ligands (Santos et al., 2021; Sun et al., 2019). Overall, berberine (3a) showed a strong affinity to RG1 with a binding constant of 105 M–1, and its binding induced the increase of the RNA melting temperature of 11 °C. As noted above, the binding properties of berberine (3a) with RG1 have already been reported, including photometric titrations (Oliva et al., 2022). The results from the latter are essentially the same as the ones presented in this work, including absorption maxima and shifts, as well as isosbestic points. However, the binding constant determined herein is about twice as high as reported in literature (Oliva et al., 2022). This difference is most likely caused by different conditions under which the data were recorded, such as buffer composition, ionic strength, concentrations, or fitting models.

A change of fluorescence is characteristic of a ligand binding to an oligonucleotide and stems from the altered environment of the fluorophore (Suh and Chaires, 1995). An increased fluorescence, as observed with 3a (Figure 3. C1), may occur if structural relaxation from the excited state, like rotation, is hindered upon binding to RNA, so that emission becomes a competitive deactivation pathway (Wickhorst and Ihmels, 2021). In contrast, decreasing fluorescence upon RNA binding, as in the case of compound 4 (Figure 3. C2), most likely results from an electron transfer between an excited ligand and the RNA bases (Seidel et al., 1996).

As an exception in the series of tested ligands, the azoniahetarene (4) showed multiple ICD signals in a range where oligonucleotides typically do not absorb light, which leads to the conclusion that the origin of these signals is the formation of a higher-order structure with the oligonucleotide. The strong positive ICD signals at 325 and 368 nm indicate binding to the major groove of the RNA (Smidlehner et al., 2018), while the weaker signal at 396 nm is characteristic of groove binding with a flexible orientation of the ligand towards the RNA (Smidlehner et al., 2018).

In general, the binding studies of the ligands 1–7 point to a possible relationship between the association with the G4-RNA quadruplex and their biological activity. For example, naphthyridine derivatives have several biological activities, including an antiviral activity (Madaan et al., 2015), which may be explained by the stabilization of the G-quadruplex upon complex formation, as these secondary structures influence viral replication and transcription (Maiti, 2022). Likewise, tetraazoniapentaphenopentaphene (4) and berberine (3a) are known to bind to G-quadruplex structures (Gra et al., 2009; Tanaya et al., 2025; Jäger et al., 2012; Tillhon et al., 2012). Additionally, berberine has been shown to interact with various nucleic acid forms and proteins, including TOP1 (Tillhon et al., 2012). Overall, these results and observations may provide some evidence that those ligands that bind sufficiently strong to G4-RNA have also the intrinsic ability to stabilize ternary complexes with quadruplex and topoisomerase, as shown in the case of RG-1 and TOP1 (Figure 4E).

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the studies on humans in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements because only commercially available established cell lines were used.

Author contributions

MB: Investigation, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Formal Analysis, Methodology. TS: Writing – review and editing, Investigation, Visualization. MM: Investigation, Writing – review and editing, Methodology. LF: Writing – review and editing, Investigation, Visualization. JG: Writing – review and editing, Investigation, Visualization. GD: Formal Analysis, Supervision, Conceptualization, Writing – original draft. HI: Writing – original draft, Supervision, Conceptualization. SK: Supervision, Writing – original draft, Conceptualization.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. MM was supported by the FNR grant 16726024 – TargetPatho to GD.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author SK declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frnar.2025.1722301/full#supplementary-material

References

1

Beaudoin J. D. Perreault J. P. (2013). Exploring mRNA 3'-UTR G-quadruplexes: evidence of roles in both alternative polyadenylation and mRNA shortening. Nucleic Acids Res.41, 5898–5911. 10.1093/nar/gkt265

2

Belmonte-Reche E. Serrano-Chacon I. Gonzalez C. Gallo J. Banobre-Lopez M. (2021). Potential G-quadruplexes and i-Motifs in the SARS-CoV-2. PloS One16, e0250654. 10.1371/journal.pone.0250654

3

Berroyer A. Kim N. (2020). The functional consequences of eukaryotic topoisomerase 1 interaction with G-Quadruplex DNA. Genes (Basel)11, 193. 10.3390/genes11020193

4

Biffi G. Tannahill D. Balasubramanian S. (2012). An intramolecular G-quadruplex structure is required for binding of telomeric repeat-containing RNA to the telomeric protein TRF2. J. Am. Chem. Soc.134, 11974–11976. 10.1021/ja305734x

5

Bisoi A. Singh P. C. (2025). Insight into the role of the chemical nature and length of the loop nucleobases in the folding of G-quadruplex by the antimalarial drugs at the DNA interface. Biointerphases20, 041004. 10.1116/6.0004389

6

De Cian A. Guittat L. Kaiser M. Saccà B. Amrane S. Bourdoncle A. et al (2007). Fluorescence-based melting assays for studying quadruplex ligands. Methods42, 183–195. 10.1016/j.ymeth.2006.10.004

7

De Magis A. Manzo S. G. Russo M. Marinello J. Morigi R. Sordet O. et al (2019). DNA damage and genome instability by G-quadruplex ligands are mediated by R loops in human cancer cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A.116, 816–825. 10.1073/pnas.1810409116

8

De Magis A. Schult P. Schönleber A. Linke R. Ludwig K. U. Kümmerer B. M. et al (2024). TMPRSS2 isoform 1 downregulation by G-quadruplex stabilization induces SARS-CoV-2 replication arrest. BMC Biol.22, 5. 10.1186/s12915-023-01805-w

9

Gellert M. Lipsett M. N. Davies D. R. (1962). Helix formation by guanylic acid. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A.48, 2013–2018. 10.1073/pnas.48.12.2013

10

Gordon D. E. Jang G. M. Bouhaddou M. Xu J. Obernier K. White K. M. et al (2020). A SARS-CoV-2 protein interaction map reveals targets for drug repurposing. Nature583, 459–468. 10.1038/s41586-020-2286-9

11

Granzhan A. Ihmels H. Jäger K. (2009). Diazonia- and tetraazoniapolycyclic cations as motif for quadruplex-DNA ligands. Chem. Commun. (Camb), 1249–1251. 10.1039/b812891j

12

Granzhan A. Ihmels H. Viola G. (2007). 9-donor-substituted acridizinium salts: versatile environment-sensitive fluorophores for the detection of biomacromolecules. J. Am. Chem. Soc.129, 1254–1267. 10.1021/ja0668872

13

Groß P. Ihmels H. (2022). Synthesis of fluorescent, DNA-binding benzo[b]indolonaphthyridinium derivatives by a misguided westphal condensation. J. Org. Chem.87, 4010–4017. 10.1021/acs.joc.1c02755

14

Gupta P. Khadake R. M. Singh O. N. Mirgane H. A. Gupta D. Bhosale S. V. et al (2025). Targeting two-tetrad RNA G-Quadruplex in the SARS-CoV-2 RNA genome using tetraphenylethene derivatives for antiviral therapy. ACS Infect. Dis.11, 784–795. 10.1021/acsinfecdis.5c00058

15

Han Y. Buric A. Chintareddy V. DeMoss M. Chen L. Dickerhoff J. et al (2024). Design, synthesis, and investigation of the pharmacokinetics and anticancer activities of indenoisoquinoline derivatives that stabilize the G-Quadruplex in the MYC promoter and inhibit topoisomerase I. J. Med. Chem.67, 7006–7032. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.3c02303

16

Ho J. S. Y. Mok B. W. Y. Campisi L. Jordan T. Yildiz S. Parameswaran S. et al (2021). TOP1 inhibition therapy protects against SARS-CoV-2-induced lethal inflammation. Cell184, 2618–2632 e2617. 10.1016/j.cell.2021.03.051

17

Hu M. H. Lin J. H. (2021). New dibenzoquinoxalines inhibit triple-negative breast cancer growth by dual targeting of topoisomerase 1 and the c-MYC G-Quadruplex. J. Med. Chem.64, 6720–6729. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c02202

18

Hu B. Guo H. Zhou P. Shi Z. L. (2021). Characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19. Nat. Rev. Microbiol.19, 141–154. 10.1038/s41579-020-00459-7

19

Hughes C. S. Moggridge S. Müller T. Sorensen P. H. Morin G. B. Krijgsveld J. (2019). Single-pot, solid-phase-enhanced sample preparation for proteomics experiments. Nat. Protoc.14, 68–85. 10.1038/s41596-018-0082-x

20

Jäger K. Bats J. W. Ihmels H. Granzhan A. Uebach S. Patrick B. O. (2012). Polycyclic azoniahetarenes: assessing the binding parameters of complexes between unsubstituted ligands and G-quadruplex DNA. Chemistry18, 10903–10915. 10.1002/chem.201103019

21

Ji D. Juhas M. Tsang C. M. Kwok C. K. Li Y. Zhang Y. (2021). Discovery of G-quadruplex-forming sequences in SARS-CoV-2. Brief. Bioinform22, 1150–1160. 10.1093/bib/bbaa114

22

Keller J. G. Hymøller K. M. Thorsager M. E. Hansen N. Y. Erlandsen J. U. Tesauro C. et al (2022). Topoisomerase 1 inhibits MYC promoter activity by inducing G-quadruplex formation. Nucleic Acids Res.50, 6332–6342. 10.1093/nar/gkac482

23

Kumar C. Batra S. Griffith J. D. Remus D. (2021). The interplay of RNA:DNA hybrid structure and G-quadruplexes determines the outcome of R-loop-replisome collisions. Elife10, e72286. 10.7554/eLife.72286

24

Lavigne M. Helynck O. Rigolet P. Boudria-Souilah R. Nowakowski M. Baron B. et al (2021). SARS-CoV-2 Nsp3 unique domain SUD interacts with guanine quadruplexes and G4-ligands inhibit this interaction. Nucleic Acids Res.49, 7695–7712. 10.1093/nar/gkab571

25

Leonetti C. Scarsella M. Riggio G. Rizzo A. Salvati E. D'Incalci M. et al (2008). G-quadruplex ligand RHPS4 potentiates the antitumor activity of camptothecins in preclinical models of solid tumors. Clin. Cancer Res.14, 7284–7291. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0941

26

Liu G. Du W. Sang X. Tong Q. Wang Y. Chen G. et al (2022). RNA G-quadruplex in TMPRSS2 reduces SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat. Commun.13, 1444. 10.1038/s41467-022-29135-5

27

Lu R. Zhao X. Li J. Niu P. Yang B. Wu H. et al (2020). Genomic characterisation and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus: implications for virus origins and receptor binding. Lancet395, 565–574. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30251-8

28

Luige J. Armaos A. Tartaglia G. G. Orom U. A. V. (2024). Predicting nuclear G-quadruplex RNA-binding proteins with roles in transcription and phase separation. Nat. Commun.15, 2585. 10.1038/s41467-024-46731-9

29

Lyu K. Chow E. Y. Mou X. Chan T. F. Kwok C. K. (2021). RNA G-quadruplexes (rG4s): genomics and biological functions. Nucleic Acids Res.49, 5426–5450. 10.1093/nar/gkab187

30

Madaan A. Verma R. Kumar V. Singh A. T. Jain S. K. Jaggi M. (2015). 1,8-Naphthyridine derivatives: a review of multiple biological activities. Arch. Pharm. Weinh.348, 837–860. 10.1002/ardp.201500237

31

Maiti A. K. (2022). Identification of G-quadruplex DNA sequences in SARS-CoV2. Immunogenetics74, 455–463. 10.1007/s00251-022-01257-6

32

Marchand C. Pourquier P. Laco G. S. Jing N. Pommier Y. (2002). Interaction of human nuclear topoisomerase I with guanosine quartet-forming and guanosine-rich single-stranded DNA and RNA oligonucleotides. J. Biol. Chem.277, 8906–8911. 10.1074/jbc.M106372200

33

Mei Y. Deng Z. Vladimirova O. Gulve N. Johnson F. B. Drosopoulos W. C. et al (2021). TERRA G-quadruplex RNA interaction with TRF2 GAR domain is required for telomere integrity. Sci. Rep.11, 3509. 10.1038/s41598-021-82406-x

34

Mergny J. L. Maurizot J. C. (2001). Fluorescence resonance energy transfer as a probe for G-quartet formation by a telomeric repeat. Chembiochem2, 124–132. 10.1002/1439-7633(20010202)2:2<124::AID-CBIC124>3.0.CO;2-L

35

Miclot T. Hognon C. Bignon E. Terenzi A. Marazzi M. Barone G. et al (2021). Structure and dynamics of RNA guanine quadruplexes in SARS-CoV-2 genome. Original strategies against emerging viruses. J. Phys. Chem. Lett.12, 10277–10283. 10.1021/acs.jpclett.1c03071

36

Miglietta G. Russo M. Capranico G. (2020). G-quadruplex-R-loop interactions and the mechanism of anticancer G-quadruplex binders. Nucleic Acids Res.48, 11942–11957. 10.1093/nar/gkaa1206

37

Nechepurenko I. V. Boyarskikh U. A. Komarova N. I. Polovinka M. P. Filipenko M. L. Lifshits G. I. et al (2011). LDLR up-regulatory activity of berberine and its bromo and iodo derivatives in human liver HepG2 cells. Dokl. Chem.439, 204–208. 10.1134/s0012500811070093

38

Oliva R. Mukherjee S. Manisegaran M. Campanile M. Del Vecchio P. Petraccone L. et al (2022). Binding properties of RNA quadruplex of SARS-CoV-2 to berberine compared to telomeric DNA quadruplex. Int. J. Mol. Sci.23, 5690. 10.3390/ijms23105690

39

Pandey S. Agarwala P. Maiti S. (2013). Effect of loops and G-quartets on the stability of RNA G-quadruplexes. J. Phys. Chem. B117, 6896–6905. 10.1021/jp401739m

40

Pithan P. M. Decker D. Druzhinin S. I. Ihmels H. Schönherr H. Voß Y. (2017). 8-Styryl-substituted coralyne derivatives as DNA binding fluorescent probes. RSC Adv.7, 10660–10667. 10.1039/c6ra27684a

41

Qin G. Zhao C. Yang J. Wang Z. Ren J. Qu X. (2022a). Unlocking G-Quadruplexes as targets and tools against COVID-19. Chin. J. Chem.41, 560–568. 10.1002/cjoc.202200486

42

Qin G. Zhao C. Liu Y. Zhang C. Yang G. Yang J. et al (2022b). RNA G-quadruplex formed in SARS-CoV-2 used for COVID-19 treatment in animal models. Cell Discov.8, 86. 10.1038/s41421-022-00450-x

43

Rouleau S. G. Garant J. M. Bolduc F. Bisaillon M. Perreault J. P. (2018). G-Quadruplexes influence pri-microRNA processing. RNA Biol.15, 198–206. 10.1080/15476286.2017.1405211

44

Ruggiero E. Richter S. N. (2018). G-quadruplexes and G-quadruplex ligands: targets and tools in antiviral therapy. Nucleic Acids Res.46, 3270–3283. 10.1093/nar/gky187

45

Salerno S. Barresi E. Roggia M. Natale B. Marzano S. Hyeraci M. et al (2024). Pursuing polypharmacology: Benzothiopyranoindoles as G-Quadruplex stabilizers and topoisomerase I inhibitors for effective anticancer strategies. ACS Med. Chem. Lett.15, 1875–1883. 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.4c00313

46

Santos T. Salgado G. F. Cabrita E. J. Cruz C. (2021). G-Quadruplexes and their ligands: biophysical methods to unravel G-Quadruplex/Ligand interactions. Pharm. (Basel)14, 769. 10.3390/ph14080769

47

Sauer M. Juranek S. A. Marks J. De Magis A. Kazemier H. G. Hilbig D. et al (2019). DHX36 prevents the accumulation of translationally inactive mRNAs with G4-structures in untranslated regions. Nat. Commun.10, 2421. 10.1038/s41467-019-10432-5

48

Schmidt N. Lareau C. A. Keshishian H. Ganskih S. Schneider C. Hennig T. et al (2021). The SARS-CoV-2 RNA-protein interactome in infected human cells. Nat. Microbiol.6, 339–353. 10.1038/s41564-020-00846-z

49

Schult P. Kummerer B. M. Hafner M. Paeschke K. (2024). Viral hijacking of hnRNPH1 unveils a G-quadruplex-driven mechanism of stress control. Cell Host Microbe32, 1579–1593 e1578. 10.1016/j.chom.2024.07.006

50

Seidel C. A. M. Schulz A. Sauer M. (1996). Nucleobase-specific quenching of fluorescent dyes. 1. nucleobase one-electron redox potentials and their correlation with static and dynamic quenching efficiencies. J. Phys. Chem.100, 5541–5553. 10.1021/jp951507c

51

Smidlehner T. Piantanida I. Pescitelli G. (2018). Polarization spectroscopy methods in the determination of interactions of small molecules with nucleic acids - tutorial. Beilstein J. Org. Chem.14, 84–105. 10.3762/bjoc.14.5

52

Song J. Gooding A. R. Hemphill W. O. Love B. D. Robertson A. Yao L. et al (2023). Structural basis for inactivation of PRC2 by G-quadruplex RNA. Science381, 1331–1337. 10.1126/science.adh0059

53

Suh D. Chaires J. B. (1995). Criteria for the mode of binding of DNA binding agents. Bioorg Med. Chem.3, 723–728. 10.1016/0968-0896(95)00053-j

54

Sun Z. Y. Wang X. N. Cheng S. Q. Su X. X. Ou T. M. (2019). Developing novel G-Quadruplex ligands: from interaction with nucleic acids to interfering with nucleic Acid(-)Protein interaction. Molecules24, 396. 10.3390/molecules24030396

55

Sun Y. Zhao C. Liu Y. Wang Y. Zhang C. Yang J. et al (2025). Screening of metallohelices for enantioselective targeting SARS-CoV-2 RNA G-quadruplex. Nucleic Acids Res.53, gkaf199. 10.1093/nar/gkaf199

56

Tanaya Y. Sashida M. Masai H. Sasanuma H. Miura D. Asano R. et al (2025). Evaluation of the effects of G4 ligands on the interaction between G-quadruplexes and their binding proteins. Chem. Commun. (Camb)61, 11790–11793. 10.1039/d5cc02801a

57

Thomas S. (2021). Mapping the nonstructural transmembrane proteins of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. J. Comput. Biol.28, 909–921. 10.1089/cmb.2020.0627

58

Tillhon M. Guaman Ortiz L. M. Lombardi P. Scovassi A. I. (2012). Berberine: new perspectives for old remedies. Biochem. Pharmacol.84, 1260–1267. 10.1016/j.bcp.2012.07.018

59

V'Kovski P. Kratzel A. Steiner S. Stalder H. Thiel V. (2021). Coronavirus biology and replication: implications for SARS-CoV-2. Nat. Rev. Microbiol.19, 155–170. 10.1038/s41579-020-00468-6

60

Wickhorst P. J. Ihmels H. (2021). Selective, pH-Dependent colorimetric and fluorimetric detection of quadruplex DNA with 4-Dimethylamino(phenyl)-Substituted berberine derivatives. Chemistry27, 8580–8589. 10.1002/chem.202100297

61

Wickhorst P. J. Druzhinin S. I. Ihmels H. Müller M. Sutera Sardo M. Schönherr H. et al (2021). A dimethylaminophenyl-substituted Naphtho[1,2-b]quinolizinium as a multicolor NIR probe for the fluorimetric detection of intracellular nucleic acids and proteins. ChemPhotoChem5, 1079–1088. 10.1002/cptc.202100148

62

Wu T. Y. Lau H. L. Santoso R. J. Kwok C. K. (2025). RNA G-quadruplex structure targeting and imaging: recent advances and future directions. RNA31, 1053–1080. 10.1261/rna.080587.125

63

Xiong Y. X. Huang Z. S. Tan J. H. (2015). Targeting G-quadruplex nucleic acids with heterocyclic alkaloids and their derivatives. Eur. J. Med. Chem.97, 538–551. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2014.11.021

64

Yadav P. Harcy V. Argueso J. L. Dominska M. Jinks-Robertson S. Kim N. (2014). Topoisomerase I plays a critical role in suppressing genome instability at a highly transcribed G-quadruplex-forming sequence. PLoS Genet.10, e1004839. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004839

65

Yadav P. Owiti N. Kim N. (2016). The role of topoisomerase I in suppressing genome instability associated with a highly transcribed guanine-rich sequence is not restricted to preventing RNA:DNA hybrid accumulation. Nucleic Acids Res.44, 718–729. 10.1093/nar/gkv1152

66

Yett A. Lin L. Y. Beseiso D. Miao J. Yatsunyk L. A. (2019). N-methyl mesoporphyrin IX as a highly selective light-up probe for G-quadruplex DNA. J. Porphyr. Phthalocyanines23, 1195–1215. 10.1142/s1088424619300179

67

Yoshimoto F. K. (2020). The proteins of severe acute respiratory syndrome Coronavirus-2 (SARS CoV-2 or n-COV19), the cause of COVID-19. Protein J.39, 198–216. 10.1007/s10930-020-09901-4

68

Zareie A. R. Dabral P. Verma S. C. (2024). G-Quadruplexes in the regulation of viral gene expressions and their impacts on controlling infection. Pathogens13, 60. 10.3390/pathogens13010060

69

Zee-Cheng K. Y. Cheng C. C. (1972). Practical preparation of coralyne chloride. J. Pharm. Sci.61, 969–971. 10.1002/jps.2600610637

70

Zhai L. Y. Su A. M. Liu J. F. Zhao J. J. Xi X. G. Hou X. M. (2022). Recent advances in applying G-quadruplex for SARS-CoV-2 targeting and diagnosis: a review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol.221, 1476–1490. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2022.09.152

71

Zhao C. Qin G. Niu J. Wang Z. Wang C. Ren J. et al (2021). Targeting RNA G-Quadruplex in SARS-CoV-2: a promising therapeutic target for COVID-19?Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl.60, 432–438. 10.1002/anie.202011419

72

Zhou P. Yang X. L. Wang X. G. Hu B. Zhang L. Zhang W. et al (2020a). Addendum: a pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature588, E6. 10.1038/s41586-020-2951-z

73

Zhou P. Yang X. L. Wang X. G. Hu B. Zhang L. Zhang W. et al (2020b). A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature579, 270–273. 10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7

74

Zhu N. Zhang D. Wang W. Li X. Yang B. Song J. et al (2020). A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N. Engl. J. Med.382, 727–733. 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017

75

Zyner K. G. Mulhearn D. S. Adhikari S. Martínez Cuesta S. Di Antonio M. Erard N. et al (2019). Genetic interactions of G-quadruplexes in humans. Elife8, e46793. 10.7554/eLife.46793

Summary

Keywords

COVID-19, G-quadruplex, RNA-binding protein, SARS-CoV-2, topoisomerase I

Citation

Burghaus M, Staschko T, Mendes M, Filcenkova L, Gerhard J, Dittmar G, Ihmels H and Krauß S (2026) A G-quadruplex structure in the SARS-CoV-2 RNA recruits human topoisomerase I. Front. RNA Res. 3:1722301. doi: 10.3389/frnar.2025.1722301

Received

10 October 2025

Revised

08 December 2025

Accepted

08 December 2025

Published

07 January 2026

Volume

3 - 2025

Edited by

Carla Ribeiro Polycarpo, Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

Reviewed by

Amani Kabbara, Université de Bordeaux, France

Alessio De Magis, Vita-Salute San Raffaele University, Italy

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Burghaus, Staschko, Mendes, Filcenkova, Gerhard, Dittmar, Ihmels and Krauß.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sybille Krauß, sybille.krauss@uni-siegen.de

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.