- 1Inner Mongolia Kunming Cigarette Co., Ltd., Hohhot, Inner Mongolia, China

- 2Northwest Agriculture and Forestry University, Yangling, Shaanxi, China

- 3Tobacco Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Qingdao, Shandong, China

Introduction: Tobacco, as an important economic crop, shows significant growth and yield responses to soil conditions and nutrient supply. In recent years, microbial organic fertilizers (MOF) have garnered significant attention as a novel fertilizer category due to their demonstrated potential for soil quality improvement and plant growth promotion. This study aims to evaluate the effects of MOF on tobacco growth in Hunan Province, with particular focus on its long-term impacts on soil physicochemical properties and rhizosphere microbial communities throughout the tobacco growth cycle.

Methods: We evaluated the effects of T1 (Basic fertilizer + Bacillus), T2 (Basic fertilizer + Pseudomonas), and T3 (Basic fertilizer + Bacillus and Pseudomonas) treatments on tobacco quality, soil parameters, and microbial communities. Soil physicochemical properties were measured using standardized analytical methods. Microbial community dynamics under different treatments were analyzed via 16S rRNA sequencing and PICRUSt2 analysis.

Results and Discussion: The results indicate that microbial fertilizers can significantly enhance soil fertility and promote tobacco growth by modulating soil microbial communities. Specifically, the T1 organic fertilizer treatment demonstrated the most pronounced effect in reducing microbial abundance, as evidenced by a lower Sobs value of 4, 222 compared to 4, 825 in the control group (p < 0.05). Furthermore, this treatment significantly enhanced the visual quality of tobacco leaves. This study provides a scientific foundation for the application of microbial fertilizers in tobacco cultivation and offers new perspectives for sustainable agricultural development.

1 Introduction

As the world’s largest producer and consumer of tobacco, this crop represents a vital economic commodity in China, where its taxation revenue simultaneously safeguards national income and promotes societal development (1, 2). Tobacco is a soil-sensitive crop whose growth and development are fundamentally dependent on edaphic conditions and nutrient supply, requiring precise pedosphere-plant equilibrium to achieve optimal development. Optimal soil fertility and a balanced microbial community are critical for healthy tobacco development (3), while environmental factors such as soil physicochemical properties also exert significant impacts on its growth and yield (4).

Traditional tobacco farming employs an exploitative cultivation model. Within constrained cultivation areas, farmers typically adopt continuous monocropping practices (1), relying heavily on chemical fertilizers and pesticides to increase yields. However, prolonged monoculture has resulted in multiple adverse consequences: soil acidification, severe salinization degradation, reduced soil fertility, disrupted soil structure, decreased organic matter (OM) content, and imbalanced microbial community (5). These issues further lead to poor disease resistance, frequent pest outbreaks, and severely compromise tobacco yield and quality (4), ultimately threatening the sustainable development of the tobacco industry. Crop rotation has been demonstrated to enhance bacterial diversity and nitrogen cycling in tobacco-growing soils, while also improving tobacco growth efficiency (6). Nevertheless, during crop rotation, other crops absorb significant amounts of soil nutrients from the soil, resulting in the depletion of soil fertility (7). Therefore, fertilizer application to replenish these depleted nutrients is essential for meeting tobacco growth requirements. Nevertheless, long-term use of inorganic fertilizers alters soil microbial diversity and community structure, which not only affects soil ecological functions but may also further impact tobacco health by impairing plant disease resistance (8). In contrast, organic fertilizers are derived from natural organic materials; they can improve soil structure while minimizing environmental damage. As a specialized type of organic fertilizer, microbial organic fertilizer (MOF) enhances soil quality by increasing organic carbon input and enriching microbial populations, thereby exerting a positive influence on crop production (8, 9).

MOF, as a novel organic fertilizer, exhibits remarkable soil conditioning effects. It has garnered increasing attention in agricultural applications, particularly in tobacco cultivation. Consequently, improving the soil environment and promoting tobacco growth through MOF application is of great significance. MOF can significantly alter soil microbial community structure. The MOF application increases the abundance of beneficial bacteria while reducing pathogenic populations (10). For instance, numerous microorganisms such as Bacillus, Escherichia, and Pseudomonas can solubilize insoluble inorganic phosphorus compounds in soil by producing organic and inorganic acids, thus lowering soil pH and enhancing phosphorus solubility (11). Furthermore, potassium-solubilizing bacteria in MOF increase soil available potassium (AK) content. As potassium is a crucial element affecting tobacco combustibility, its enhanced availability significantly improves leaf flammability (12). The application of MOF increases soil organic carbon content. Specifically, microbial-derived organic substances and residues from microbial metabolic processes contribute to soil organic carbon accumulation (11). Furthermore, MOF exhibits significant growth-promoting effects on tobacco plants. Its application significantly improves tobacco growth parameters such as plant height, stem circumference, and leaf number, which is attributed to MOF’s dual functions of enhancing soil nutrient transformation and stimulating root development (8). These modifications not only improve soil ecological functions but also enhance plant disease resistance, thereby further promoting healthy tobacco growth. Research demonstrates that a combination of 70% compost and 30% chemical fertilizer is more effective than chemical fertilizer alone. Organic fertilizers increase soil organic carbon content, consequently stimulating heterotrophic microbial growth (13). The combination of organic fertilizers with microbial fertilizers can achieve sustained high crop yields while maintaining soil ecological balance. Furthermore, the application of low-concentration chemical fertilizers and high-concentration MOF enhances soil microbial diversity (14). In MOF, Bacillus spp. function as plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) that significantly enhance tobacco growth. These bacteria synthesize indole-3-acetic acid (IAA), a phytohormone that promotes root development throughout tobacco’s growth cycle. Additionally, they enhance ACC (1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid) deaminase activity, which degrades root-secreted ACC, thereby reducing ethylene levels in tobacco plants and alleviating abiotic stress (15). In soil, Bacillus can solubilize insoluble inorganic phosphorus and potassium, thereby increasing the content of available nutrients. Furthermore, certain Bacillus strains possess nitrogen-fixing capacity, enabling the conversion of atmospheric nitrogen into plant-available ammonia (16). Beyond Bacillus, Pseudomonas also exhibits significant potential in MOF. Studies have demonstrated that Pseudomonas significantly improves tobacco seed germination rate and root length, thereby promoting seedling growth (17). Moreover, certain Pseudomonas strains are capable of producing siderophore, and possess nitrogen fixation and phosphate solubilization capabilities. This enables them to colonize tobacco seedling roots efficiently and stably while significantly increasing biomass and plant height (18). However, despite progress in MOF applications for tobacco cultivation, current challenges include high production costs for standalone MOF use, inconsistent performance across different regions, and a lack of targeted research.

Therefore, this study aims to investigate the effects of MOF containing either Bacillus or Pseudomonas on tobacco growth in Hunan Province. Three experimental groups and one control group were set up: the control group received only basal fertilizer, while the three experimental groups were further supplemented with Bacillus, Pseudomonas, or a mixture of these two strains in addition to the basal fertilizer. The experiment was conducted in Changjiang Village, Renyi Town, and Guiyang County. This study evaluated the impacts of microbial fertilizers on soil physicochemical properties and rhizosphere microbial communities during the prosperously growing stage growth stage of tobacco, laying a scientific foundation for the application of microbial fertilizers in tobacco cultivation and presents new insights into sustainable agricultural development.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Experimental site

The study was conducted in Changjiang Village, Renyi Town, Guiyang County, Chenzhou City, Hunan Province (112°23′26″E to 112°55′46″E, 25°37′15″N to 26°13′30″N). The selected tobacco field historically employed a tobacco-rice rotation system, with red soil as the dominant soil type. The experimental site experiences an annual average temperature of 16–23°C.

2.2 Experimental design

This study used tobacco plants at the prosperously growing stage and set up four different treatment methods. The experimental groups were T1, T2, and T3, and the CK group served as the control group, which only applied basic fertilizers. The basic fertilizers included a one-time application of 900 kg ha-¹ special tobacco compound, 227 kg ha-¹ potassium silicate mineral fertilizer (a slow-release potassium fertilizer), and 136 kg ha-¹ special tobacco seedling fertilizer. In addition to conventional fertilization in the experimental groups, the T1 treatment group applied 10 mL of Bacillus per plant, with the viable count exceeding 9×108 CFU/mL. The T2 treatment group applied Pseudomonas at a dose of 10 mL per plant, with the viable counts exceeding 3×109 CFU/mL. The T3 treatment group applied a 1:1 mixture of Bacillus and Pseudomonas at 10 mL per plant. The viable count of Bacillus exceeded 9×108 CFU/mL, and that of Pseudomonas exceeded 3×109 CFU/mL. Four sample plots were selected for both the control and experimental groups, each consisting of 5 rows, with each row 10 m long and a total area of 80 m². To facilitate inspection and sampling, a 0.5 m wide walkway was set between the test plots, and protective measures were implemented at the test site. The fertilization time was determined according to the past years’ experience in this region. The daily management of tobacco plants was uniformly supervised in accordance with the national standard GB/T 23221-2008, and the soil moisture levels among different treatment groups were ensured to be consistent.

2.3 Soil sample collection and soil physicochemical analysis

According to the scope of the experimental plots, the S-shaped sampling method was adopted, with 9 sampling points evenly set along the trajectory to ensure coverage of both the edge and central areas of the plot. Tobacco plants near the sampling points that were well-grown, with dark green leaves, undamaged, and free from pests and diseases were randomly selected. A total of 9 tobacco plants for each group. Soil samples from 10–20 cm were obtained for each sampling point, and the soil was collected along the plant roots with a stainless-steel soil drill (5 cm in diameter), taken out with a sterile brush, put into a sampling bag, transported to the laboratory with ice bags for refrigeration, and stored at -80 °C for detection (19, 20). The total weight of soil samples in each treatment group was 500g. The 9 samples were collected at a time and uniformly mixed into one-third to ensure the uniformity of the collected samples. The subsequent experiments were conducted with 3 replicates. The potting soil obtained by screening through a 60-mesh sieve (diameter 0.25 mm) was used to avoid the presence of smoke, debris, etc., in the test soil. A glass electrode digital pH meter was used to mix 10 g of air-dried soil with 25 mL of distilled water for determining the pH value in the samples. Soil available phosphorus (AP) was extracted using 0.5 M sodium bicarbonate and quantified by molybdenum blue colorimetry. Available potassium (AK) content was measured by leaching soil with ammonium acetate and using flame photometry (21). According to the Agricultural Industry Standard of the People’s Republic of China (NY/T 1378–2007), soil chloride content was determined by titrating soil leachate with silver nitrate. Organic matter (OM) was quantified using the potassium dichromate volumetric method with external heating. Nitrate nitrogen (NO3-–N) was measured using the phenol-2, 4-disulfonic acid colorimetric method; soil ammonium nitrogen (NH4+–N) was determined via KCl extraction-indophenol blue colorimetry. Each physicochemical parameter of each sample group (n = 3) was measured in triplicate. Significant differences were analyzed using analysis of variance (ANOVA). Different letters indicate significant differences between groups (p < 0.05).

2.4 Collection of tobacco leaf samples

Tobacco leaves in each group were divided into upper, middle, and lower leaves, and were subjected to curing. Then, 5 well-grown and uniform leaves were randomly selected from each of the upper, middle, and lower leaves, respectively, for the characterization of tobacco appearance quality.

2.5 Extraction of sample DNA

The total genomic DNA of the microbial community was extracted according to the instructions of the E.Z.N.A.® soil DNA kit (Omega Bio-tek, Norcross, GA, U.S.). The quality of the extracted genomic DNA was detected by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis, and the DNA concentration and purity were determined using a NanoDrop2000 (Thermo Scientific, U.S.).

2.6 PCR Amplification and sequencing library construction

Using the extracted DNA as a template, the V3-V4 variable region of the 16S rRNA gene was amplified by PCR with the upstream primer 338F (5’-ACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGCAG-3’) and downstream primer 806R (5’-GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3’) carrying Barcode sequences (Liu et al., 2016). The PCR products were recovered using 2% agarose gel electrophoresis, purified with a DNA gel recovery purification kit (PCR Clean-Up Kit, Yuhua, China), and quantified using Qubit 4.0 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). The NEXTFLEX® Rapid DNA-Seq Kit was used to construct libraries from the purified PCR products.

2.7 High-throughput sequencing data analysis

The high-throughput sequencing data were analyzed on the online platform of Majorbio Cloud Platform (22). The raw paired-end sequencing reads were subjected to quality control using fastp (23) (https://github.com/OpenGene/fastp, version 0.19.6) and subsequently merged with FLASH (https://github.com/ebiggers/flash, version 1.2.11). Quality-controlled and merged sequences were processed using UPARSE v7.1 (24, 25) (Stackebrandt and Goebel, 1994) (http://drive5.com/uparse/) to cluster operational taxonomic units (OTUs) at 97% similarity and remove chimeric sequences. To minimize the impact of sequencing depth on subsequent alpha and beta diversity analyses, all samples were rarefied to 20, 000 sequences. After rarefaction, the average Good’s coverage of each sample remained at 99.09%. OTUs were taxonomically annotated using the RDP classifier (26) (https://sourceforge.net/projects/rdp-classifier/, version 2.11) by aligning to the Silva 16S rRNA gene database (v138) with a confidence threshold of 70%. Community composition was then statistically analyzed for each sample at different taxonomic levels. Functional prediction based on 16S rRNA sequences was performed using PICRUSt2 (version 2.2.0) (27).

2.8 Statistical analysis

All sequence data were submitted to the Sequence Read Archive (Accession Number: PRJNA1205160) and can be freely accessed through the NCBI website (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/PRJNA1205160).The alpha diversity indices, such as Chao 1 and Shannon index, were calculated using mothur software, and the Wilxocon rank-sum test was used to analyze the inter-group differences in alpha diversity. Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) based on the bray-curtis distance algorithm was used to test the similarity of microbial community structures among samples, and combined with PERMANOVA non-parametric test to analyze whether the differences in microbial community structures among sample groups were significant. LEfSe analysis (Linear discriminant analysis Effect Size) (LDA>2, P<0.05) was employed to identify bacterial taxa with significantly differential abundances from phylum to genus level among groups (http://huttenhower.sph.harvard.edu/LEfSe) (28). Distance-based redundancy analysis (db-RDA) was used to investigate the effects of soil physicochemical properties on bacterial community structure. Linear regression analysis was applied to evaluate the influence of key soil physicochemical/clinical indicators identified by db-RDA on microbial alpha diversity indices. Species with |Spearman’s correlation coefficient| > 0.6 and p<0.05 were selected for correlation network analysis (29).

3 Results and analysis

3.1 Effects of microbial inoculants on physicochemical properties of tobacco soil

This study investigated the effects of different treatments on the physicochemical properties of tobacco-planted soil during the prosperously growth stage (Table 1). The pH values of soils in all treatment and control (CK) groups remained stable at approximately 6.5 during this stage, indicating that MOF application had minimal impact on soil pH. Although organic matter (OM) content decreased after MOF application, no significant differences were observed among the treatment groups compared to the CK. During the prosperously growth stage, the T3 treatment group exhibited significantly higher levels of available potassium (AK), nitrate nitrogen (NO3–N), and ammonium nitrogen (NH4+-N) compared to other treatments (p < 0.05). Among all groups, the T1 treatment group had the highest content of available phosphorus (AP).

3.2 Effects of microbial inoculants on the composition of rhizosphere soil microorganisms at the prosperously growing stage

As shown in Supplementary Figure S1, the dilution curve tends to flatten, and the coverage reaches 97.44%. These results together indicate that the detection rate of the microbial community in tobacco-planting soil is close to saturation. The current sequencing volume can cover most species in the samples, and the sequencing depth meets the experimental requirements.

To characterize the microbial composition in soils of the three experimental groups and the control group, we analyzed the microbial community using a Venn diagram and a phylum-level species composition heatmap (Figure 1). In the Venn diagram (Figure 1A), the application of MOF significantly altered the bacterial composition in tobacco rhizosphere soil. At the genus level, T1 exhibited 1, 414 unique bacterial genera, T2 showed 1, 494, T3 had 1, 397, and CK displayed 2, 230. The experimental groups and the control group shared a total of 3, 392 common bacterial genera. In the species composition heatmap (Figure 1B), the dominant bacterial phyla in all treatment and control groups remained unchanged, but the relative abundances of these dominant phyla differed. The top four dominant phyla were Proteobacteria, Actinobacteriota, Chloroflexi, and Acidobacteriota, which collectively accounted for more than 70% of the total soil bacterial community. Among these, the relative abundances of the first dominant phylum (Proteobacteria) and the second dominant phylum (Actinobacteriota) in both T1 and T3 were higher than those in CK. This indicates that MOF containing Bacillus can alter the relative abundances of soil microbial communities in tobacco-planting soil.

Figure 1. Phylum-level species composition analysis. (A) Venn diagram analysis. (B) Community composition analysis.

To investigate how microbial organic fertilizers (MOFs) with different compound microbial inoculants affect soil microbial composition, we analyzed the diversity and richness of microbial communities in tobacco-planting soil across treatment and control groups using α-diversity analysis (Table 2). Alpha diversity analysis reflects microbial richness and diversity; the Shannon and Simpson indices microbial community diversity; the Sobs, Chao, and Ace indices indicate microbial community richness; and the Coverage index reflects microbial community coverage. The results showed that sequencing coverage for all samples exceeded 99%, indicating sufficient data coverage. After applying the three MOFs, the Shannon, Sobs, Ace, and Chao indices all decreased, suggesting reduced microbial community diversity and overall richness in soil. Compared with T1 and T3 (which contain Bacillus), the decrease in Shannon index in the Pseudomonas-containing group was not significant relative to CK.

PCoA analysis was performed at the phylum level on tobacco-planting soil during the prosperously growing stage to assess the differences in soil bacterial community composition following MOF application. The results (Figure 2) showed significant differences in microbial communities between the microbial inoculant-treatment groups (T1, T2, T3) and the control group (CK) (PERMANOVA, R = 0.50, p=0.01). The microbial communities of the T2 and T3 groups were also distinct, while separation between T1 and the T2/T3 groups was less obvious. This suggests that microbial inoculant addition significantly affects soil bacterial community composition.

To analyze the significant characteristics of soil microbial communities following MOF application during the prosperously growing stage, we conducted LEfSe analysis (Figure 3). Through LEfSe multi-level species difference analysis (with taxa defined from phylum to genus and an LDA threshold of 2), a total of 105 distinct bacterial taxa with detailed information were identified. At the phylum level, LEfSe analysis revealed that Verrucomicrobiota and Planctomycetota were significantly enriched in CK; Dadabacteria and Armatimonadota were significantly enriched in T1; and Actinobacteriota and Gemmatimonadota were significantly enriched in T3.

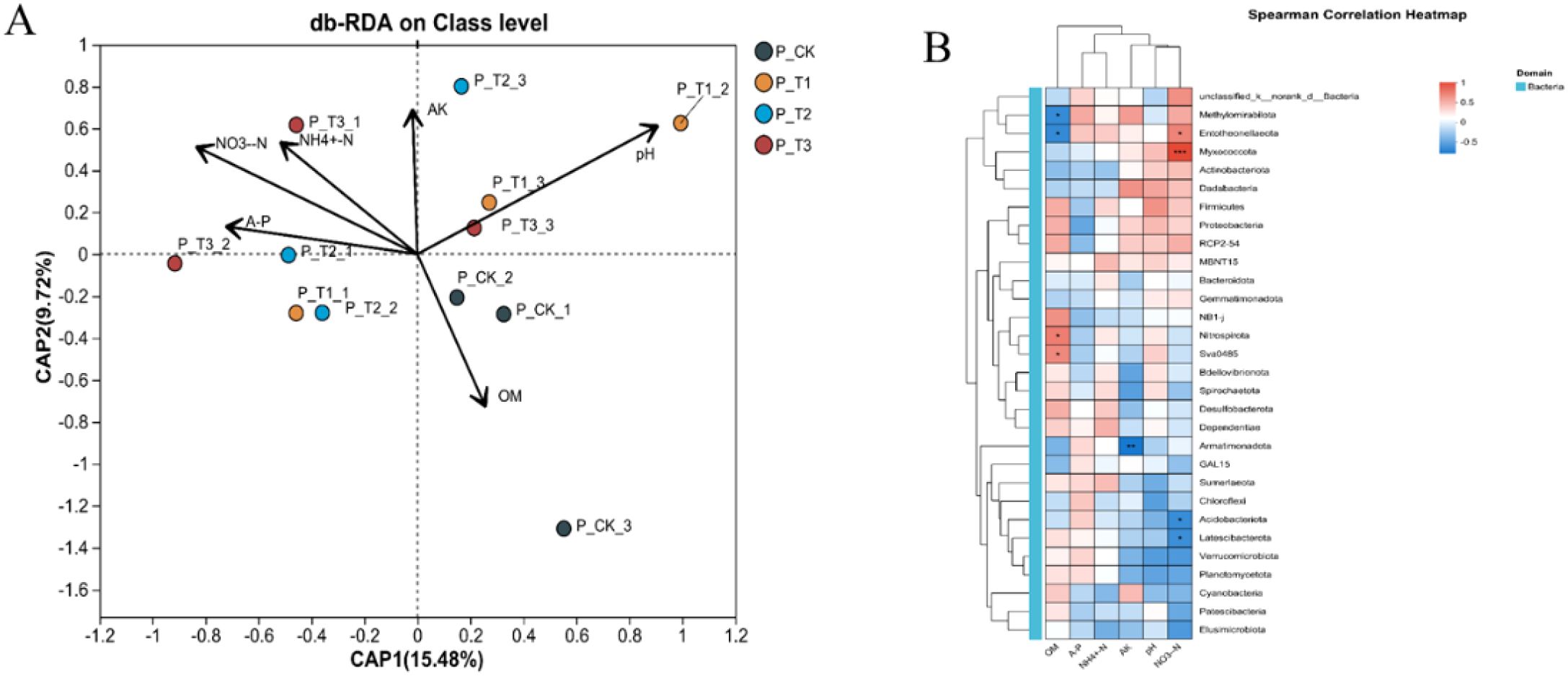

To further illustrate how soil physicochemical properties influence the microbial community in tobacco-planting soil, and vice versa, db-RDA analysis was performed (Figure 4A). CAP1 and CAP2 explained 15.48% and 9.72% of the bacterial community variation, respectively. Compared with the control group, AP, NH4+-N, and NO3–N exerted stronger influences on the bacterial communities of T2 and T3, while pH had a more significant influence on the T1 bacterial community. The control group bacterial community was more strongly associated with OM. Considering the influence of varying species abundances, we also analyzed the correlation between the top 30 phyla and soil physicochemical properties (Figure 4B). The results showed that bacterial communities at different phylum levels exhibited significant correlations with soil physicochemical properties. Myxococcota and Entotheonellaeota were significantly positively correlated with NO3–N content; Nitrospirota was significantly positively correlated with soil OM; Armatimonadota was significantly negatively correlated with AK content; and Acidobacteriota and Latescibacterota were negatively correlated with NO3–N content.

Figure 4. Environmental factor correlation analysis. (A) Class-level db-RDA analysis. (B) Phylum-level correlation heatmap analysis.

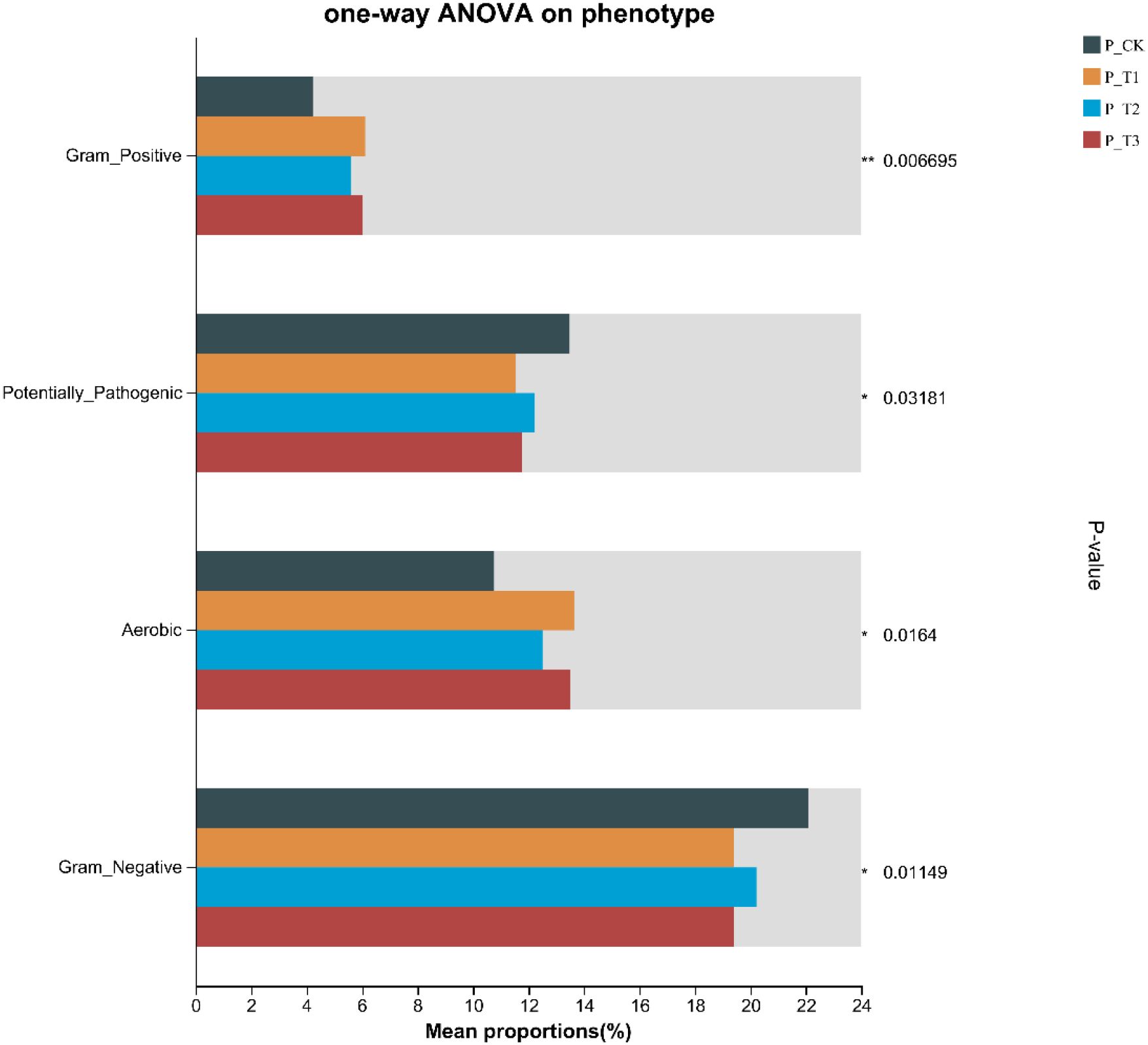

To further explore the effects of MOF on the functional characteristics of bacterial communities in tobacco rhizosphere soil, we conducted analysis using the BugBase database (Figure 5). The results showed that MOF addition significantly improved soil aerobic conditions, thereby promoting root respiration, supporting beneficial microbial activities, and enhancing soil structure. Meanwhile, significant differences were observed in Gram-positive bacterial functional characteristics, with levels significantly higher than those in the control group.

Additionally, the BugBase database was used to analyze the functional characteristics of soil microbial communities under each tobacco treatment (Figure 6). The results showed that T1 microbial organic fertilizer significantly enhanced mobile genetic element content, Gram-positive characteristics, and oxygen utilization; T2 microbial organic fertilizer had significant effects on Gram-positive characteristics and oxygen utilization; and T3 significantly enhanced soil stress resistance, Gram-positive characteristics, and oxygen utilization. These results collectively indicate that the application of compound microbial organic fertilizers is an important factor influencing the abundance and structural changes of soil microbial communities. It can reduce the abundance of certain microbial taxa in tobacco-planting soil to some extent while significantly enhancing the functional characteristics of soil microbiota, thereby promoting tobacco growth.

Figure 6. BugBase phenotypic group difference test. (A) The five functional traits that differ between T1 and CK. (B) The four functional traits that differ between T2 and CK. (C) The six functional traits that differ between T3 and CK.

3.3 Effects of microbial inoculants on tobacco leaf physical characteristics

During the prosperously growing stage of tobacco, application of different MOFs showed distinct impacts on tobacco leaves (Figure 7). The T1 treatment exhibited the most pronounced effects, with significant differences relative to the CK group in leaf length and width of lower leaves, leaf length of middle leaves, and leaf width of upper leaves. Although the leaf width of middle leaves and leaf length of upper leaves did not show significant differences, there were still observable increases.

In addition, the appearance quality of flue-cured tobacco leaves was analyzed (Table 3). In T1, the improvement in upper leaves was most evident. Significant differences were observed between T1 and CK in terms of color, maturity, leaf structure, leaf body, oil content, chroma, and total worth, with all parameters higher than those in CK. In T2, significant differences were only found in the oil content of upper leaves, as well as the color, maturity, oil, and total worth of middle leaves. In T3, relative to CK, significant differences were observed in the color and chroma of upper leaves, and the oil and total worth of middle leaves. Among leaves at different tobacco positions, the three experimental groups exerted the least influence on the total worth of lower leaves.

4 Discussion

The study found that the application of microbial fertilizers exerted little influence on changes in soil pH. During the prosperously growing stage, soil pH remained stable at 6.5, which falls within tobacco’s optimal growth pH range (5.5–6.5), thus providing a suitable growth environment for tobacco. This is consistent with the findings of previous research (30). Under this condition, the availability of soil nutrients, soil enzyme activity, and soil fertility are all high (31). Soil organic matter (OM) also plays an important role in tobacco cultivation. Although the content of soil OM did not change significantly, the content range remained suitable for tobacco growth. Nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium are among the essential macronutrients for tobacco, playing a crucial role in its growth and development (32). Available potassium (AK) is involved in various physiological and metabolic processes in tobacco, such as photosynthesis, respiration, and enzyme activation, all of which are vital for maintaining the normal physiological functions of tobacco. In tobacco’s response to abiotic stress, AK helps plants maintain water status and enhance stress resistance by regulating stomatal opening-closing and osmotic pressure balance (33). Available phosphorus (AP) can promote the growth and development of tobacco roots, and enhance roots’ ability to absorb nutrients and water from the soil, thereby improving the stress resistance and growth potential of tobacco (34). The combined application of microbial fertilizers containing Bacillus and Pseudomonas can significantly increase soil AK content during the prosperously growing stage. Bacillus and Pseudomonas can convert insoluble potassium minerals in the soil into soluble potassium through their metabolic activities, thereby increasing soil AK content. These microorganisms dissolve soil potassium minerals by secreting organic acids (such as oxalic acid and citric acid) and extracellular enzymes (such as phosphatase), thus increasing the potassium availability (35). Bacillus can destroy mineral lattices through organic acids to release K+, but cannot efficiently remove Fe³+ and Al³+ in the lattices, resulting in the re-adsorption of some K+ (36). In contrast, Pseudomonas can secrete siderophores that specifically chelate Fe³+ and Al³+, preventing them from adsorbing K+ (37). In the mixed treatment, the organic acids of Bacillus destroy the lattices, while the siderophores of Pseudomonas remove the adsorbed ions, leading to a higher content of AK in the soil compared with the single-strain treatment. In addition, the combined inoculation of Bacillus and Pseudomonas significantly increases soil soluble and exchangeable potassium content. This synergistic effect not only boosts soil AK content but also promotes tobacco’s absorption and utilization of potassium, which is consistent with the findings of Maysoon et al. (38). The combined application of biological fertilizers and Bacillus increased soil AP content during the prosperously growing stage. When Bacillus decomposes insoluble phosphorus sources (e.g., calcium phosphate), soil AP content can be significantly increased (39)-a result consistent with our findings. In addition, Bacillus not only increases soil AP content but also further enhances plants’ absorption efficiency by regulating root growth and development (40). Bacillus spp. can increase the activity of phosphorylase by secreting organic acids, thereby increasing the content of AK in soil. The increase in AK content in the soil can enhance the uptake of AK by tobacco plants, which results in an improvement in plant chlorophyll (41), and thereby promotes enhancements in the color and chroma of tobacco leaves. NH4+-N is one of the nitrogen forms that can be directly absorbed and utilized by tobacco. It mainly exists in soil in the form of ammonium ions and can be directly taken up by tobacco roots. Meanwhile, NO3–N is another main nitrogen form absorbed by tobacco: it is produced in soil via nitrification, can be absorbed by tobacco roots, and then converted into amino acids and proteins required by tobacco. Both forms of nitrogen are key factors that drive tobacco cell division, protein synthesis, and photosynthesis (42). The increase of ammonium nitrogen could promote the synthesis of fatty acids, thereby increasing the oil content in tobacco leaves. Therefore, the utilization of nitrogen can promote tobacco growth and improve tobacco quality (43). Microorganisms such as Bacillus and Pseudomonas can convert insoluble soil nitrogen sources into soluble nitrogen through their metabolic activities and boost soil available nitrogen content, which is consistent with the results of Liang et al. (44). Moreover, Bacillus secretes proteases and ureases to lyse proteins and decompose urea in the soil into NH4+-N (45). NH4+-N can be oxidized to nitrite nitrogen (NO2–N), and through nitrification, NO2–N can be converted to NO3–N (46). When Bacillus and Pseudomonas are used in combination, they can synergistically enhance the contents of NH4+-N and NO3–N in the soil through multiple complementary pathways.

Based on the strong correlation between plant growth and microbial ecological characteristics, this study investigated the rhizosphere soil microbial composition of tobacco during the prosperously growing stage. α-diversity analysis showed that each treatment group significantly affected the bacterial diversity in tobacco rhizosphere soil. The increased nutrient demand of tobacco intensified the competition among microbial communities. In addition, the application of Bacillus accelerated the succession process of bacterial communities (e.g., those dominated by Bacillus), and further exacerbated bacterial competition, which in turn led to reduced diversity and richness. Previous studies have shown that the application of Bacillus can alter soil microbial community structure and reduce the abundance of soil microbial pathogens (47). In this study, the sampling period was the prosperously growth stage of tobacco, during which AK in the soil was absorbed in large quantities by tobacco plants. Moreover, the experimental site is located in southern China, with red soil as the soil type and low soil pH. Such soil conditions provide a favorable growth environment for the Bacillus genus, enabling it to quickly occupy a dominant position in the soil microbial community. Furthermore, Bacillus can secrete organic acids such as gluconic acid and citric acid, which can further reduce soil pH. This change can inhibit the enrichment of most gram-negative bacteria, resulting in a decrease in microbial abundance (48). While the application of Pseudomonas showed some differences from the control group, the degree of difference was less than that of the Bacillus treatment group. Analysis at the phylum level revealed that the top four phyla in each treatment group were Proteobacteria, Actinobacteriota, Chloroflexi, and Acidobacteriota. The application of Bacillus significantly increased the abundance of Proteobacteria and Actinobacteriota. Proteobacteria can promote plant growth and enhance plant stress resistance through various mechanisms, including nitrogen fixation, phosphorus solubilization, production of plant hormones (e.g., indole-3-acetic acid, gibberellins, and polyamines), and secretion of antifungal compounds and hydrolytic enzymes to inhibit soil-borne diseases (49). Actinobacteriota can regulate soil microbial community structure, mediate nutrient element transformation and plant uptake, and catalyze the degradation of organic pollutants and the redox process of heavy metals to protect tobacco-planting soil (50). Moreover, Actinobacteriota can improve soil physicochemical properties by secreting substances such as extracellular polysaccharides, enhance soil aggregate stability, and boost soil aeration and water retention, thereby providing a better growth environment for plant roots (51). In addition, our principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) of each treatment group indicated that the application of Bacillus and Pseudomonas had a significant impact on soil structure, which is consistent with the research results of Mawarda et al. (52). We also conducted LEfSe multi-level species difference analysis on each component, screening out 105 bacterial taxa with specific detailed information (populations defined from phylum to genus, LDA threshold = 2). Based on the db-RDA analysis, it was found that the T1 treatment group showed a stronger positive correlation with pH, which may be attributed to the massive secretion of organic acids by Bacillus. The T2 and T3 treatment groups exhibited a stronger positive correlation with NH4+-N and NO3–N, which may be due to Bacillus secreting various enzymes to decompose proteins and urea into NH4+-N, and further increasing NO3–N in the soil through nitrification (43). In contrast, Pseudomonas enhances the contents of NH4+-N and NO3–N in the soil via enzymes and metabolites (53). The T2 and T3 treatment groups exerted a greater impact on A-P, NH4+-N, and NO3--N. Both groups contained Pseudomonas, a Gram-negative bacterium known for its metabolic diversity and strong environmental adaptability (54). Pseudomonas can secrete low-molecular-weight organic acids (e.g., citric acid, oxalic acid, and gluconic acid) through metabolism; this reduces soil pH, promotes the dissolution of insoluble phosphates (Ca3(PO4)2, FePO4, AlPO4), and releases soluble phosphate (PO4³-) (55). Additionally, Pseudomonas secretes acid phosphatases (encoded by genes such as phoA and phoD), which hydrolyze organic phosphorus compounds to increase soil phosphate (PO4³-) content (56). Furthermore, it can secrete proteases to dissolve proteins and ureases to hydrolyze urea, thereby releasing NH4+ (57, 58). Meanwhile, Pseudomonas regulates soil NO3--N content through its own nitrification activity and by inhibiting denitrification. The metabolites secreted by Pseudomonas can provide carbon sources or electron donors for ammonia-oxidizing bacteria (such as Nitrosomonas), indirectly promoting the conversion of NH4+→NO2-→NO3- (53). The T1 treatment group was significantly correlated with changes in soil pH. Bacillus subtilis can reduce soil pH by secreting acidic substances and organic acids in saline-alkali soil, thereby alleviating saline-alkali stress (59). However, some Bacillus species (e.g., Bacillus mucilaginosus and Bacillus megaterium) can increase soil pH by secreting metabolites and improving soil organic matter (OM) (60). Furthermore, we analyzed the correlation between the top 30 phyla and soil physicochemical properties. The results showed that bacterial communities at different phylum levels were significantly correlated with soil physicochemical properties. Myxococcota and Entotheonellaeota were significantly positively correlated with soil NO3--N content, while Nitrospirota was significantly positively correlated with soil OM content. Additionally, we used the BugBase database to analyze the functional characteristics of soil microbial communities under each tobacco treatment. The results indicated that T1 microbial organic fertilizer significantly promoted the increase in mobile genetic elements, Gram-positive characteristics, and oxygen utilization. T2 microbial organic fertilizer had significant impacts on Gram-positive bacteria and oxygen utilization. T3 played an important role in enhancing soil stress resistance, Gram-positive characteristics, and oxygen utilization. This indicates that applying microbial organic fertilizer with mixed bacterial strains may be more conducive to assisting plants in defense and helping them resist adverse external environments than that with a single bacterial strain (61).

Here, the results revealed the effects of two microbial inoculants on soil physicochemical properties, rhizosphere microorganisms, and tobacco leaf traits. It provides insights for the microbial regulation of cash crop quality, offers a practical basis for developing sustainable agricultural management strategies, and holds important guiding significance for reducing chemical fertilizer application.

5 Conclusion

This study investigated the changes in soil microbial communities during the prosperously growth stage of tobacco after applying different microbial inoculants. The results showed that the application of various microbial inoculants during this stage increased soil organic matter, available phosphorus, available potassium, ammonium nitrogen, and nitrate nitrogen levels. Notably, the application of T1 significantly increased the relative abundance of Proteobacteria and Actinobacteriota in the soil, remarkedly raised the number of Gram-positive bacteria, and inhibited Gram-negative bacteria, thereby improving the appearance quality of tobacco leaves during the prosperously growing stage. These findings provide a valuable basis for further research into the role of microbial inoculants in promoting tobacco growth and enhancing agricultural productivity.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/PRJNA1205160, reference number PRJNA1205160.

Author contributions

CG: Methodology, Formal Analysis, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Supervision. JHa: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Formal Analysis. SM: Writing – review & editing, Data curation, Methodology, Investigation. JHo: Investigation, Writing – review & editing, Methodology. SW: Methodology, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. LZ: Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Supervision. BZ: Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Methodology. HD: Writing – review & editing, Data curation. XL: Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Methodology. SX: Writing – original draft, Investigation. JS: Writing – original draft. GS: Writing – review & editing, Data curation. JY: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. YW: Funding acquisition, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. MS: Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition, Resources.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation (ZR2022QC236), and Shandong Provincial Colleges and Universities “Youth Innovation Team Program” (2022KJ167). The authors declare that this study received funding from the Technology development (commissioning) project from Inner Mongolia Kunming Cigarette Limited Liability Company (Grant No.202315010534-JS-062 and 202315010534-JS-061). The funder was not involved in the study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, the writing of this article, or the decision to submit it for publication.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Zhaobao Wang and the “Laboratory for Agricultural Molecular Biology” of Qingdao Agricultural University for analyzing the data and providing laboratory apparatus, respectively.

Conflict of interest

Authors CG, JHa, SM, JHo, SW, LZ, BZ, HD and XL were employed by Inner Mongolia Kunming Cigarette Co., Ltd.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fsoil.2025.1666961/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Hu TW, Mao Z, Shi J, and Chen W. The role of taxation in tobacco control and its potential economic impact in China. Tob Control. (2010) 19:58–64. doi: 10.1136/tc.2009.031799

2. Mackay J. China: the tipping point in tobacco control. Brit Med Bull. (2016) 120:15–25. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldw043

3. Brow CN, Johnson RO, Xu M, Johnson RL, and Simon HM. Effects of cryogenic preservation and storage on the molecular characteristics of microorganisms in sediments. Environ Sci Technol. (2010) 44:8243–7. doi: 10.1021/es101641y

4. Jiang Y, Gu K, Song L, Zhang C, Liu J, Chu H, et al. Fertilization and rotation enhance tobacco yield by regulating soil physicochemical and microbial properties. Soil Till Res. (2025) 247:106364. doi: 10.1016/j.still.2024.106364

5. Murase J, Hida A, Ogawa K, Nonoyama T, Yoshikawa N, and Imai K. Impact of long-term fertilizer treatment on the microeukaryotic community structure of a rice field soil. Soil Biol Biochem. (2015) 80:237–43. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2014.10.015

6. Zhong J, Pan W, Jiang S, Hu Y, Yang G, Zhang K, et al. Flue-cured tobacco intercropping with insectary floral plants improves rhizosphere soil microbial communities and chemical properties of flue-cured tobacco. BMC Microbiol. (2024) 24:446. doi: 10.1186/s12866-024-03597-7

7. Liu Y, Yu J, Li X, Xu Y, and Shen Q. Effects of combined application of organic and inorganic fertilizers on soil microbiological characteristics in a wheat-rice rotation system. J Agro-Environ Sci. (2012) 31:989–94.

8. Shen M, Zhang Y, Bo G, Yang B, Wang P, Ding Z, et al. Microbial responses to the reduction of chemical fertilizers in the rhizosphere soil of flue-cured tobacco. Front Bioeng Biotech. (2022) 9:812316. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2021.812316

9. Pu R, Wang P, Guo L, Li M, Cui X, Wang C, et al. The remediation effects of microbial organic fertilizer on soil microorganisms after chloropicrin fumigation. Ecotox Environ Safe. (2022) 231:113188. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2022.113188

10. Ahsan T, Tian P, Gao J, Wang C, Liu C, and Huang Y. Effects of microbial agent and microbial fertilizer input on soil microbial community structure and diversity in a peanut continuous cropping system. J Adv Res. (2023) 64:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jare.2023.11.028

11. Tian X, Zhang X, Yang G, Wang Y, Liu Q, and Song J. Effects of microbial fertilizer application on soil ecology in saline–alkali fields. Agronomy. (2024) 15:14. doi: 10.3390/AGRONOMY15010014

12. Qu P, Liu G, Liu H, Si C, Liu Z, Hu X, et al. Research advances in tobacco potassium ion channel. Chin Toba Sci. (2009) 30:74–80.

13. Hasnain M, Chen J, Ahmed N, Memon S, Wang L, Wang Y, et al. The effects of fertilizer type and application time on soil properties, plant traits, yield and quality of tomato. Sustainability. (2020) 12:9065. doi: 10.3390/su12219065

14. Wu Q, Chen Y, Dou X, Liao D, Li K, An C, et al. Microbial fertilizers improve soil quality and crop yield in coastal saline soils by regulating soil bacterial and fungal community structure. Sci Total Environ. (2024) 949:175127. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.175127

15. Liu C, Du C, Liang Z, Zhang D, Liu A, and Yu J. Screening and identification of phosphorus-solubilizing bacteria in tobacco rhizosphere and their antibacterial and growth-promoting effects. Chin Toba Sci. (2020) 41:9–15. doi: 10.13496/j.issn.1007-5119.2020.01.002

16. Muthuraja R and Muthukumar T. Co-inoculation of halotolerant potassium solubilizing Bacillus licheniformis and Aspergillus violaceofuscus improves tomato growth and potassium uptake in different soil types under salinity. Chemosphere. (2022) 294:133718. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2022.133718

17. Gu J, Fang D, Li T, and Liu X. Preliminary study on the mechanism of growth promoting of tobacco by Pseudomonas fluorescens RB-42 and RB-89. J Plant Nutr Fertil. (2002) 8:493–6. doi: 10.11674/zwyf.2002.0422

18. Huang L, Wang W, Shah SB, Hu H, Xu P, and Tang H. The HBCDs biodegradation using a Pseudomonas strain and its application in soil phytoremediation. J Hazard Mater. (2019) 380:120833. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2019.120833

19. Hu W, Schoenau JJ, and Si B. Representative sampling size for strip sampling and number of required samples for random sampling for soil nutrients in direct seeded fields. Precis Agric. (2015) 16:385–404. doi: 10.1007/s11119-014-9384-3

20. Yu X, Zhang Y, Shen M, Dong S, Zhang F, Gao Q, et al. Soil conditioner affects tobacco rhizosphere soil microecology. Microb Ecol. (2022) 86:460–73. doi: 10.1007/s00248-022-02030-8

21. Hao X, Zhu P, Zhang H, Liang Y, Yin H, Liu X, et al. Mixotrophic acidophiles increase cadmium soluble fraction and phytoextraction efficiency from cadmium contaminated soils. Sci Total Environ. (2019) 655:347–55. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.11.221

22. Han C, Shi C, Liu L, Han J, Yang Q, Wang Y, et al. Majorbio Cloud 2024: Update single-cell and multiomics workflows. iMeta. (2024) 3:e217. doi: 10.1002/imt2.217

23. Chen S, Zhou Y, Chen Y, and Gu J. fastp: an ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics. (2018) 34:884–90. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty560

24. Edgar RC. UPARSE: highly accurate OTU sequences from microbial amplicon reads. Nat Methods. (2013) 10:996–8. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2604

25. Stackebrandt E and Goebel BM. Taxonomic note: a place for DNA-DNA reassociation and 16S rRNA sequence analysis in the present species definition in bacteriology. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. (1994) 44:846–9. doi: 10.1099/00207713-44-4-846

26. Wang Q, Garrity GM, Tiedje JM, and Cole JR. Naive Bayesian classifier for rapid assignment of rRNA sequences into the new bacterial taxonomy. Appl Environ Microbiol. (2007) 73:5261–7. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00062-07

27. Douglas GM, Maffei VJ, Zaneveld JR, Yurgel SN, Brown JR, Taylor CM, et al. PICRUSt2 for prediction of metagenome functions. Nat Biotechnol. (2020) 38:685–8. doi: 10.1038/s41587-020-0548-6

28. Segata N, Izard J, Waldron L, Gevers D, Miropolsky L, Garrett WS, et al. Metagenomic biomarker discovery and explanation. Genome Biol. (2011) 12:1–18. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-6-r60

29. Barberán A, Bates ST, Casamayor EO, and Fierer N. Using network analysis to explore co-occurrence patterns in soil microbial communities. ISME J. (2012) 6:343–51. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2011.119

30. Xi W, Ping Y, Cai H, Tan Q, Liu C, Shen J, et al. Effects of soil properties on Pb, Cd, and Cu contents in tobacco leaves of Longyan, China, and their prediction models. Int J Anal Chem. (2023) 2023:9216995. doi: 10.1155/2023/9216995

31. Zhang Y, Wu M, He P, She G, Wu B, and Wei J. Research advance of the relationship between soil enzyme activity and soil fertility. J Anhui Agr Sci. (2007) 35:11139. doi: 10.13989/j.cnki.0517-6611.2007.34.045

32. Iradukunda A, Zhang D, Ye T, Habineza E, Wang M, Uwamahoro HP, et al. Trace elements loss characteristics in runoff discharge from tobacco-growing red soil in sichuan province of China. J Agr Chem Environ. (2022) 11:163–83. doi: 10.4236/jacen.2022.113011

33. Awad AA, Hussein HA, El Samad AGA, Belal HE, and Beheiry HR. Foliar nourishment with different potassium sources to maximize yield through improving nutrient uptake in Citrus Aurantifolia trees grown in potassium-deficient soil. J Soil Sci Plant Nutr. (2024) 24:7151–66. doi: 10.1007/s42729-024-02030-2

34. Zhu S, Cheng Z, Wang J, Gong D, Ullah F, Tao H, et al. Soil phosphorus availability and utilization are mediated by plant facilitation via rhizosphere interactions in an intercropping system. Eur J Agron. (2023) 142:126679. doi: 10.1016/j.eja.2022.126679

35. Liu X, Mei S, and Salles JF. Inoculated microbial consortia perform better than single strains in living soil: a meta-analysis. Appl Soil Ecol. (2023) 190:105011. doi: 10.1016/j.apsoil.2023.105011

36. Liu W, Xu X, Yang Q, and Wu X. Mechanisms of Bacillus mucilaginosus decomposing soil minerals. Soils. (2004) 36:547–50.

37. Gu Y, Yan W, Chen Y, Liu S, Sun L, Zhang Z, et al. Plant growth-promotion triggered by extracellular polymer is associated with facilitation of bacterial cross-feeding networks of the rhizosphere. ISME J. (2025) 19:wraf040. doi: 10.1093/ismejo/wraf040

38. Maysoon A and Hassan KU. Synergistic effect of Bacillus mucilaginosus and Pseudomonas fluorescens on the availability of soil potassium, growth and yield of Cucurbita pepo L. Iraqi J Agric Sci. (2024) 55:1650–6. doi: 10.36103/285hkz27

39. Turan M, Ataoglu N, and Sahin F. Effects of Bacillus FS-3 on growth of tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum L.) plants and availability of phosphorus in soil. Plant Soil Environ. (2007) 53:58–64. doi: 10.17221/2297-PSE

40. Xie J, Yan Z, Wang G, Xue W, Li C, Chen X, et al. A bacterium isolated from soil in a karst rocky desertification region has efficient phosphate-solubilizing and plant growth-promoting ability. Front Microbiol. (2021) 11:625450. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.625450

41. Han J, Yang S, Wang Y, Yue C, and Zhang X. The effects of different potassium fertilizer on potassium content and photosynthetic characteristics in flue-cured tobacco leaves. Acta Tabacaria Sin. (2002) 8:22–5.

42. Wang Z, Guo X, Cao S, Yang M, Gao Q, Zong H, et al. Tobacco/Isatis intercropping system improves soil quality and increase total production value. Front Plant Sci. (2024) 15:1458342. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2024.1458342

43. Xiao Q, Dai Y, Yu X, Wang K, Zhu X, Qin P, et al. Fumigant dazomet induces tobacco plant growth via changing the rhizosphere microbial community. Sci Rep. (2025) 15:6673. doi: 10.1038/s41598-025-91432-y

44. Liang M, Wu Y, Jiang Y, Zhao Z, Yang J, Liu G, et al. Microbial functional genes play crucial roles in enhancing soil nutrient availability of halophyte rhizospheres in salinized grasslands. Sci Total Environ. (2025) 958:178160. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.178160

45. Kou H, Chen Y, Sun P, Li H, and Xin J. Study on the efficiency and mechanism of combined mineralization of organic nitrogen in saline soil by biochar and bacteria. Period Ocean Univ China. (2025) 55:83–93. doi: 10.16441/j.cnki.hdxb.20240050

46. Zhao K, Tian X, Dong S, Jiang W, and Li H. Nitrogen removal characteristic and mechanism of heterotrophic nitrifying-aerobic denitrifying Bacillus licheniformis. Period Ocean Univ China. (2020) 50:43–52. doi: 10.16441/j.cnki.hdxb.20190136

47. Sales LR and Rigobelo EC. The role of Bacillus sp. in reducing chemical inputs for sustainable crop production. Agronomy. (2024) 14:2723. doi: 10.3390/agronomy14112723

48. Wang Z, Liu M, Liu X, Bao Y, and Wang Y. Solubilization of K and P nutrients from coal gangue by Bacillus velezensis. Appl Environ Microbiol. (2024) 90:e01538–24. doi: 10.1128/aem.01538-24

49. Teng K, Lan W, Lei G, Mao H, Tian M, Chao J, et al. Effects of Pichia sp. J1 and plant growth-promoting bacterium on enhancing tobacco growth and suppressing bacterial wilt. Curr Microbiol. (2025) 82:187. doi: 10.1007/s00284-025-04172-7

50. Bhatti AA, Haq S, and Bhat RA. Actinomycetes benefaction role in soil and plant health. Microb Pathog. (2017) 111:458–67. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2017.09.036

51. Diab MK, Mead HM, Ahmad Khedr MM, Abu-Elsaoud AM, and El-Shatoury SA. Actinomycetes are a natural resource for sustainable pest control and safeguarding agriculture. Arch Microbiol. (2024) 206:268. doi: 10.1007/s00203-024-03975-9

52. Mawarda PC, Lakke SL, Dirk van Elsas J, and Salles JF. Temporal dynamics of the soil bacterial community following Bacillus invasion. iScience. (2022) 25:104185. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2022.104185

53. Huang M, Cui Y, Huang J, Sun F, and Chen S. A novel Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain performs simultaneous heterotrophic nitrification-aerobic denitrification and aerobic phosphate removal. Water Res. (2022) 221:118823. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2022.118823

54. Weimann A, Dinan AM, Ruis C, Bernut A, Pont S, Brown K, et al. Evolution and host-specific adaptation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Science. (2024) 385:eadi0908. doi: 10.1126/science.adi0908

55. Mohankumar KT, Nath PR, Jyoti PT, Atmaram CK, Ananta V, Suresh C, et al. Impact of low molecular weight organic acids on soil phosphorus release and availability to wheat. Commun Soil Sci Plant Anal. (2022) 53:2497–508. doi: 10.1080/00103624.2022.2071935

56. Zhang Y, Li J, Lu F, Wang S, Ren Y, Guo S, et al. The enzyme activity of dual-domain β-propeller alkaline phytase as a potential factor in improving soil phosphorus fertility and triticum aestivum growth. Agronomy. (2024) 14:614. doi: 10.3390/agronomy14030614

57. Aqel H, Sannan N, Foudah R, and Al-Hunaiti A. Enzyme production and inhibitory potential of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: contrasting clinical and environmental isolates. Antibiotics. (2023) 12:1354. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics12091354

58. Fortuna A, Collalto D, Rampioni G, and Leoni L. Assays for studying Pseudomonas aeruginosa secreted proteases. Methods Mol Biol. (2023) 2721:137–51. doi: 10.1007/978-1-0716-3473-8_10

59. Ng CWW, Yan W, Tsim KWK, So PS, Xia Y, and To CT. Effects of Bacillus subtilis and Pseudomonas fluorescens as the soil amendment. Heliyon. (2022) 8:e11674. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e11674

60. Lu H, Wang C, Han E, Wang X, and Gu X. Effects of Bacillus Mucilaginosus and Megaterium on the changes of soil phosphorus forms. Chin J Soil Sci. (2024) 55:1724–33.

Keywords: microbial organic fertilizer, tobacco cultivation, soil physicochemical properties, soilbacterial community, sustainable agriculture

Citation: Guo C, Hao J, Ma S, Hong J, Wang S, Zhang L, Zhang B, Ding H, Liu X, Xing S, Sun J, Shen G, Yang J, Wu Y and Shen M (2025) Effects of microbial fertilizers on tobacco plants and soil microbial community during the prosperously growing stage. Front. Soil Sci. 5:1666961. doi: 10.3389/fsoil.2025.1666961

Received: 16 July 2025; Accepted: 22 October 2025;

Published: 24 November 2025.

Edited by:

Enrica Picariello, University of Sannio, ItalyReviewed by:

Yong-Xin Liu, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, ChinaShuaibing Wang, Yuxi Normal University, China

Copyright © 2025 Guo, Hao, Ma, Hong, Wang, Zhang, Zhang, Ding, Liu, Xing, Sun, Shen, Yang, Wu and Shen. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yuanhua Wu, d3V5dWFuaHVhQGNhYXMuY24=; Minchong Shen, c2hlbm1pbmNob25nQGNhYXMuY24=

Chunsheng Guo1,2

Chunsheng Guo1,2 Jian Sun

Jian Sun Jianming Yang

Jianming Yang Minchong Shen

Minchong Shen