- 1Center of Excellence for Soil and Fertilizer Research in Africa, College of Agriculture and Environmental Sciences, Mohammed VI Polytechnique University, Ben Guerir, Morocco

- 2Laboratory of Bioresources and Food Safety, Faculty of Science and Technology, University Cadi Ayyad, Marrakech, Morocco

Potentially toxic elements (PTEs) in agricultural soils threaten food security and human health, particularly in semi-arid regions where intensive agriculture and limited water resources amplify contamination risks. This study addresses critical knowledge gaps by evaluating PTE distribution, sources, and ecological risks across five representative soil types in north-central Morocco, a region characterized by exceptional pedological diversity including Luvic Phaeozems, Haplic Calcisols, Chromic Luvisols, Vertisols, and Calcic Kastanozems. Unlike conventional regional assessments that apply uniform thresholds, we integrate soil-type-specific analysis to reveal how pedological properties fundamentally control PTE behavior and risk patterns. Fifteen soil samples from 20 horizons across representative pedons and five bedrock samples were analyzed using ICP-OES to quantify nine PTEs (As, Cd, Cu, Mn, Ba, Pb, Sr, Ti, Zn), alongside physicochemical properties (pH, electrical conductivity, organic carbon, texture, cation exchange capacity) to elucidate their influence on metal mobility. Distribution Index, Enrichment Factor, Transfer Factor, and Potential Ecological Risk Index distinguished contamination sources and quantified risks, while Principal Component Analysis identified geochemical associations. Results reveal pronounced soil-type dependency. Luvic Phaeozem exhibited highest contamination, with Cd, As, and Pb exceeding WHO/FAO thresholds and very high ecological risk (PERI>1100). Cd emerged as most mobile, correlating with acidic pH and organic matter. Clay content strongly controlled retention. Multivariate analysis identified anthropogenic contamination with clay retention and carbonate buffering as two main geochemical associations. Principal Component Analysis effectively separated soil types, clustering Luvic Phaeozems and Calcic Kastanozems due to high contamination and retention capacity and isolating Haplic Calcisols and Vertisols for their carbonate and clay-driven buffering behavior. These findings emphasize the necessity of integrating soil typology into risk assessments and recommend targeted bioremediation and soil-type-informed agricultural management to mitigate PTE risks and promote sustainable land use in semi-arid Moroccan agricultural systems.

Introduction

Soil contamination by potentially toxic elements (PTEs) has become a critical environmental issue, especially in regions with intensive agricultural practices. This contamination presents serious threats due to the persistent nature, bioaccumulation potential, and inherent toxicity of elements such as arsenic (As), cadmium (Cd), lead (Pb), copper (Cu), zinc (Zn), manganese (Mn), barium (Ba) and strontium (Sr) (1, 2). These contaminants adversely affect agricultural productivity and food safety by impairing plant physiology, degrading soil fertility, and entering human food chains, which raises critical public health concerns (3, 4).

Health effects from exposure to PTEs through contaminated food consumption can include severe conditions such as kidney damage, cardiovascular disorders, neurological impairment, and an increased risk of cancer. Specifically, Cd is associated to kidney dysfunction and bone disorders. As exposure is linked to skin lesions and carcinogenesis, and Pb poses risks of neurological impairments, particularly affecting children’s cognitive development (5, 6). Given these serious health implications, identifying contamination sources becomes essential for effective risk management. Previous studies have identified both natural sources, such as geological weathering and soil formation processes, and anthropogenic sources, particularly agricultural inputs, mining, and industrial emissions, as primary contributors to soil PTE contamination (7, 8).

Morocco presents a unique setting to examine PTE contamination dynamics, due to its diverse semi-arid agroecosystems. Its varied pedological contexts, including Phaeozem, Calcisols, Luvisol, Vertisol, and Kastanozem soils, strongly influence the fate and transport of PTEs through mechanisms such as adsorption, precipitation, and complexation (9, 10). In the north-central part of the country, recent investigations have reported significant accumulation of PTEs in agricultural soils related to irrigation with wastewater and long-term cultivation (11–15). However, despite numerous studies on PTE contamination, significant knowledge gaps persist in semi-arid agroecosystems. These include the lack of vertical profiling to assess PTE distribution across soil horizons, limited integration of geochemical indices with soil typology, and insufficient understanding of how specific soil properties control PTE behavior and ecological risk. While most studies in Morocco have focused on heavily contaminated mining sites, agricultural soils remain understudied, despite their importance for food security and environmental health.

This study addresses these gaps by testing three specific hypotheses: (1) PTE contamination within the same locality varies significantly according to soil type, reflecting distinct pedological properties and retention capacities; (2) soil carbonate content correlates positively with PTE retention in calcareous horizons, while clay content and organic matter differentially control vertical mobility between topsoil and subsoil layers; and (3) integrating pedological variability with contamination indices enables more accurate risk assessment than conventional approaches that treat all soils uniformly. Given the distinct physicochemical properties of each soil type, variations in retention mechanisms, redox buffering capacity, and the interaction between geogenic and anthropogenic inputs are anticipated to influence contaminant behavior across horizons.

This study aims to evaluate the vertical distribution, determine the geochemical origins (natural versus anthropogenic), and quantify the ecological and human health risks associated with nine PTEs in representative soil types in the semi-arid region of north-central Morocco. The originality of this work lies in coupling soil-type-specific vertical profiling with contamination indices; an approach rarely applied to agricultural soils in semi-arid zones. By employing total elemental analysis, geochemical indices (Enrichment Factor, Distribution Index, Transfer Factor, and Potential Ecological Risk Index), and Principal Component Analysis (PCA), the study seeks to: (1) characterize contamination profiles and assess ecological risks within different soil horizons; (2) separate and quantify natural versus anthropogenic contributions; and (3) elucidate how pedological parameters influence the behavior and distribution of PTEs. These findings will provide essential insights for targeted contamination management strategies and improved agricultural sustainability.

2 Materials and methods

The following methods were designed to comprehensively characterize PTE distribution across diverse soil types, distinguish contamination sources, and assess associated ecological risks. The methodology integrates field sampling, laboratory analysis, geochemical indexing, and statistical techniques to test the hypotheses outlined above and address the research objectives.

2.1 Site description

The study was conducted across three distinct agroecological zones in central Morocco: Beni Amir, Kenitra, and El Jadida. These regions represent varied geological and agricultural conditions, allowing for a representative assessment of dominant soil types (Figure 1). Beni Amir, located in the Tadla Plain, experiences a semi-arid to warm Mediterranean climate with an average temperature of 20°C and annual rainfall of 430 mm, decreasing westward from the Atlas mountains (16, 17). The area is geologically composed of heterogeneous Mio-Pliocene and Quaternary deposits within a synclinal depression. The region supports irrigated agriculture, including oranges, olives, and sugarcane, with water sourced from the Oum Er Rbia River (11, 16, 18). Kenitra, on the Gharb Plain, features a subhumid climate with an annual rainfall of 718.6 mm and temperatures between 12.8°C and 22.4°C, with peaks in December (19, 20). Its geology includes Paleozoic sedimentary and metamorphic rocks overlain by Triassic red clays, Jurassic-Cretaceous dolomites, and Miocene blue marls, forming deep aquifers (20). Land use in this area is dominated by the cultivation of cereals, olives, and sugar beets, although environmental risks persist due to nearby unmanaged landfills. El Jadida, part of the Moroccan Meseta, has a Mediterranean climate moderated by oceanic influence, receiving around 551 mm of rainfall annually. Seasonal temperatures range from 12°C in winter to 23°C in summer. Geologically, the region consists of tabular sedimentary layers from the Tertiary, Secondary, and Quaternary resting on a folded basement (21).

2.2 Sampling procedures

Five representative soil profiles were selected based on pedological diversity, agricultural land use, and accessibility criteria. Site selection was guided by the Soil Atlas of Africa (22). The selected soil types include Luvic Phaeozems (P1), Haplic Calcisols (P2), Chromic Luvisols (P3), Vertisols (P4), and Calcic Kastanozems (P5), representing the major pedogenetic variations in the study region.

For each soil type, a single representative profile pit was excavated down to the C-horizon for a detailed morphological description and horizon-specific sampling. The spatial coordinates of sampling locations were recorded using GPS (Table 1). Soil horizons were distinguished based on field observations of color, texture, structure, consistency, and boundary characteristics. Horizon designation and classification were conducted according to the World Reference Base for Soil Resources (23). Additionally, bedrock samples (n=5, one per profile) were collected from the underlying parent material to establish site-specific geochemical baselines for contamination assessment.

2.3 Sample preparation and laboratory analysis

Soil samples were air-dried at room temperature, passed through a 2-mm sieve to remove coarse fragments, and stored in sealed polyethylene bags for subsequent analysis. Rock samples were cleaned with deionized water, air-dried, and ground into fine powder (<75 μm) using a mortar grinder (Retsch RM 200, Retsch GmbH, Germany) to ensure homogeneity before digestion.

2.3.1 Physicochemical properties

Soil pH and electrical conductivity (EC) were measured in 1:2.5 soil: water suspensions using SensION™-PH31 (Hach, USA) and SevenDirect-SD30 (Mettler-Toledo, Switzerland), respectively. Total organic carbon (TOC) was determined using an elemental analyzer (Flash 2000, Thermo Scientific, USA). Particle size distribution was analyzed using the hydrometer method (24) after dispersion with a sodium hexametaphosphate solution (GPR Rectapur®, ≥99%, VWR Chemicals, UK). Cation exchange capacity (CEC) was determined by extracting soils with ammonium acetate (purity ≥98.0%, ACS grade, Merck, Germany) at pH 7.5 as detailed in (25). Calcium carbonate content was determined using Bernard’s calcimeter method.

2.3.2 Elemental analysis

Total concentrations of As, Cd, Cu, Mn, Ba, Pb, Sr, Ti, and Zn in soil and rock samples were quantified using Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectrometry (ICP-OES- Agilent 5800, Agilent Technologies, USA). For digestion, 0.5 g of finely powdered sample was treated with 3.5 mL aqua regia (1.5 mL HNO3, 1.5 mL HCl; 67-69% and 34-37%, respectively, Normatom® grade, VWR Chemicals, France) and 0.5 mL hydrofluoric acid (HF ≥ 99%, VWR BDH Chemicals, UK), to ensure complete dissolution of silicate minerals, following standard protocols for total metal extraction (ISO 14869-1).

2.3.3 Quality assurance and control

Quality assurance and control protocols included procedural blanks, sample triplicates, and a certified phosphate rock reference material (BCR-03), analyzed with each batch. A subset of the total samples was analyzed in triplicate to assess the precision of the measurement procedure. Triplicate analysis of selected samples yielded relative standard deviations (RSDs) below 5% for all elements, confirming high analytical precision. Recovery rates for PTEs in the reference material and 0.5 ppm internal control standards ranged between 99% and 101%, demonstrating excellent accuracy.

2.4 Data analysis

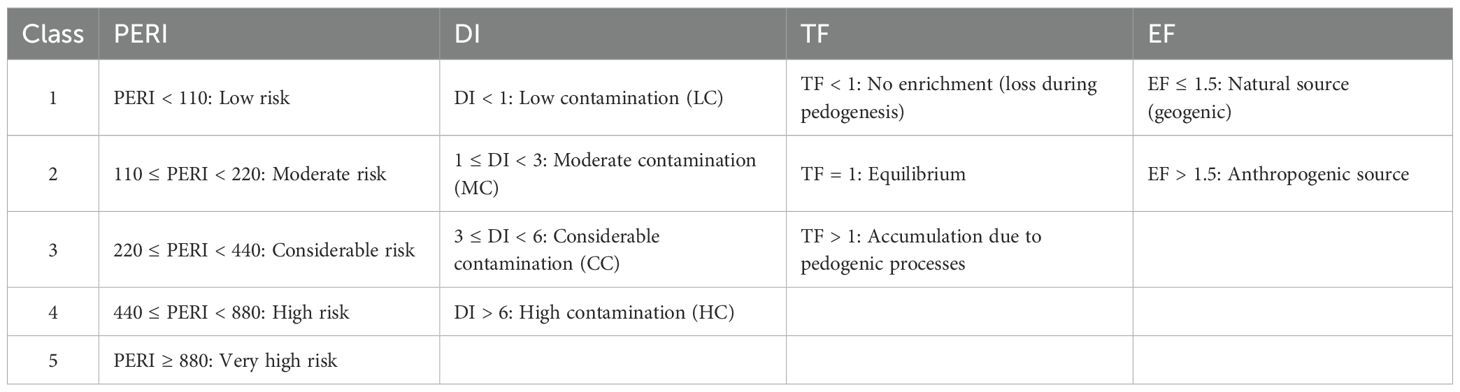

To evaluate the contamination levels, vertical mobility, and ecological risks associated with PTEs in the studied soils, four widely recognized geochemical indices were calculated: Distribution Index (DI), Transfer Factor (TF), Enrichment Factor (EF), and Potential Ecological Risk Index (PERI). These indices were selected based on their widespread use in soil contamination studies and their complementary insights into contamination degree, source apportionment, vertical mobility, and ecological impact, respectively (26, 27). Classification criteria for each index are summarized in Table 2.

2.4.1 Distribution index

The Distribution Index (DI) measures the level of elemental contamination by comparing the concentration of a trace element in the soil sample to its respective concentration in the parent material, which serves as a natural background reference. It offers a relative measure of contamination at the profile scale (28) and is calculated using Equation 1:

Where Cs represents the trace element concentration in the soil sample, and Cb is the background concentration of the same trace element.

2.4.2 Enrichment factor

The Enrichment Factor (EF) is used to differentiate between natural and anthropogenic sources of soil PTEs (29). It was calculated using Equation 2:

where Cn and Cref were concentration of target PTE and reference element, respectively. Ti was selected as the reference element due to its geochemical stability, minimal anthropogenic input, and association with resistant minerals (e.g., ilmenite, rutile) that remain immobile during weathering (30).

2.4.3 Transfer factor

The Transfer Factor (TF) evaluates the redistribution of soil PTEs between the parent material and the overlying soil horizon. his assessment is essential for understanding whether soil-forming processes lead to enrichment or depletion of these elements. The TF is calculated using Equation 3, proposed by Acosta et al. (31):

Where Xh represents the metal concentration in the soil horizon, Xp represents the concentration of Ti in the same soil horizon, Yh is the concentration of the metal in the parent material, and Ypis the concentration of Ti in the parent material.

2.4.4 Potential ecological risk index

The Potential Ecological Risk Index (PERI) was used to evaluate the ecological impact of PTE contamination, following the framework initially proposed by Hakanson (28). This method integrates both the contamination factor of each metal and its corresponding toxic-response factor . The individual potential ecological risk factor (Eri) and the overall PERI were calculated using Equations 4, 5:

In this study, the toxicity factors of As, Cd, Cu, Pb, Zn and Mn were 10, 30, 5, 5, 1 and 1, respectively (32, 33). Since the group of PTEs analyzed in this study differs from that in the original Hakanson method, the adjusted ecological risk classification proposed by Cai et al. (34) was adopted to ensure consistency between the set of toxicity coefficients and the corresponding classification thresholds (Table 2).

2.5 Statistical analysis

2.5.1 Profile-weighted mean calculation

The weighted mean concentration for each soil pedon was calculated to account for varying horizon thickness using Equation 6:

Where W is the weighted mean concentration (mg·kg-1), ci is the element concentration in the horizon i (mg·kg-1); di represents the thickness of horizon i (cm), P is the total profile depth (cm), and n is the number of horizons. This method weighs each horizon’s concentration by its proportional contribution to the total profile depth, providing a more accurate profile-scale estimate than arithmetic means.

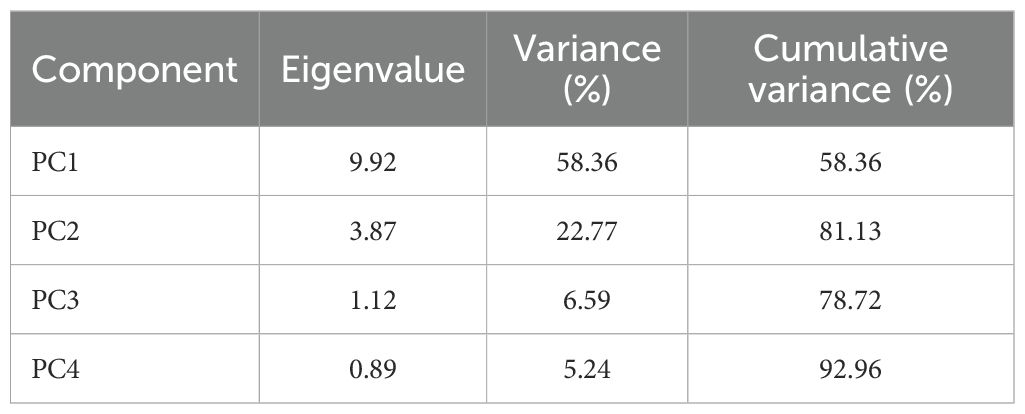

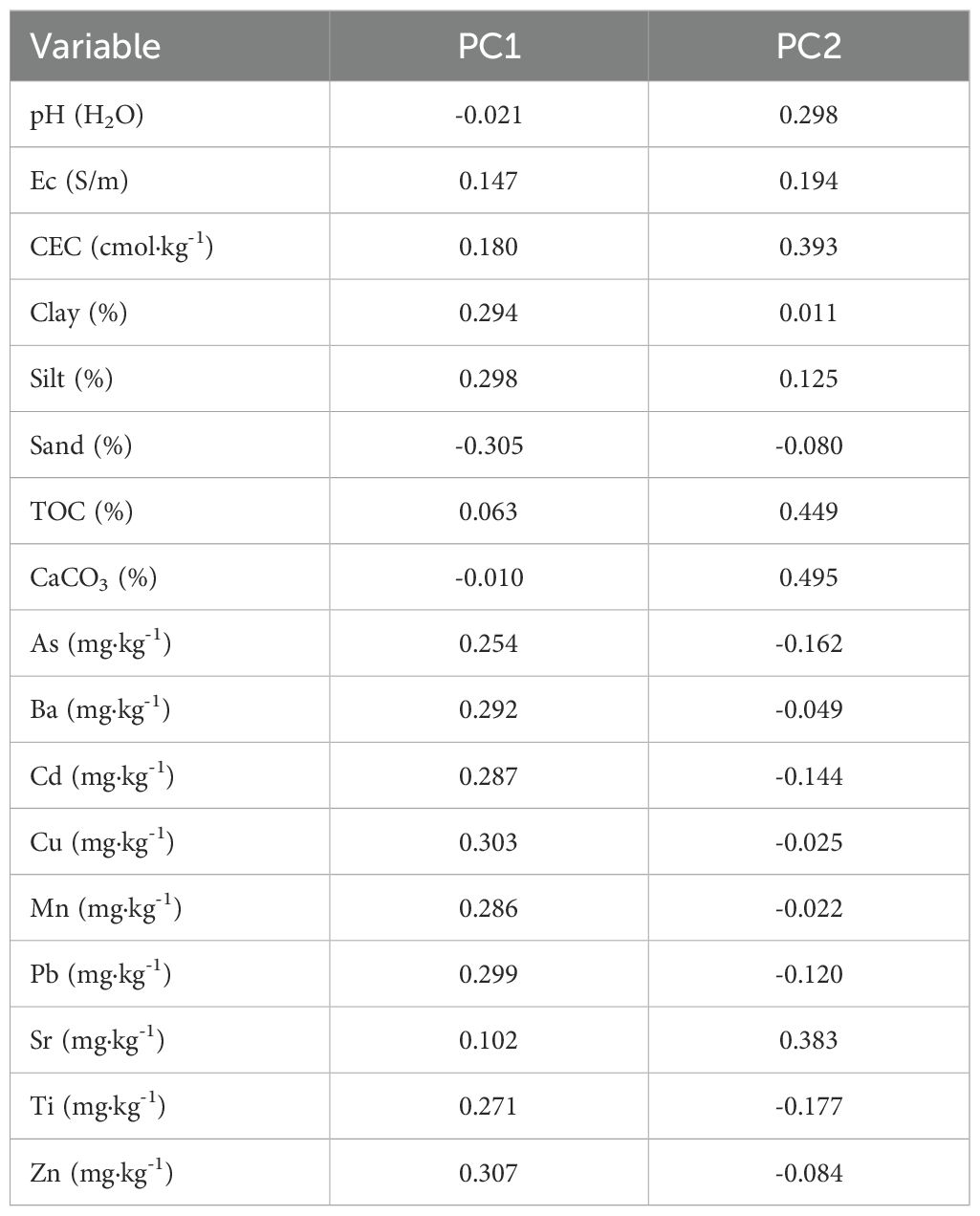

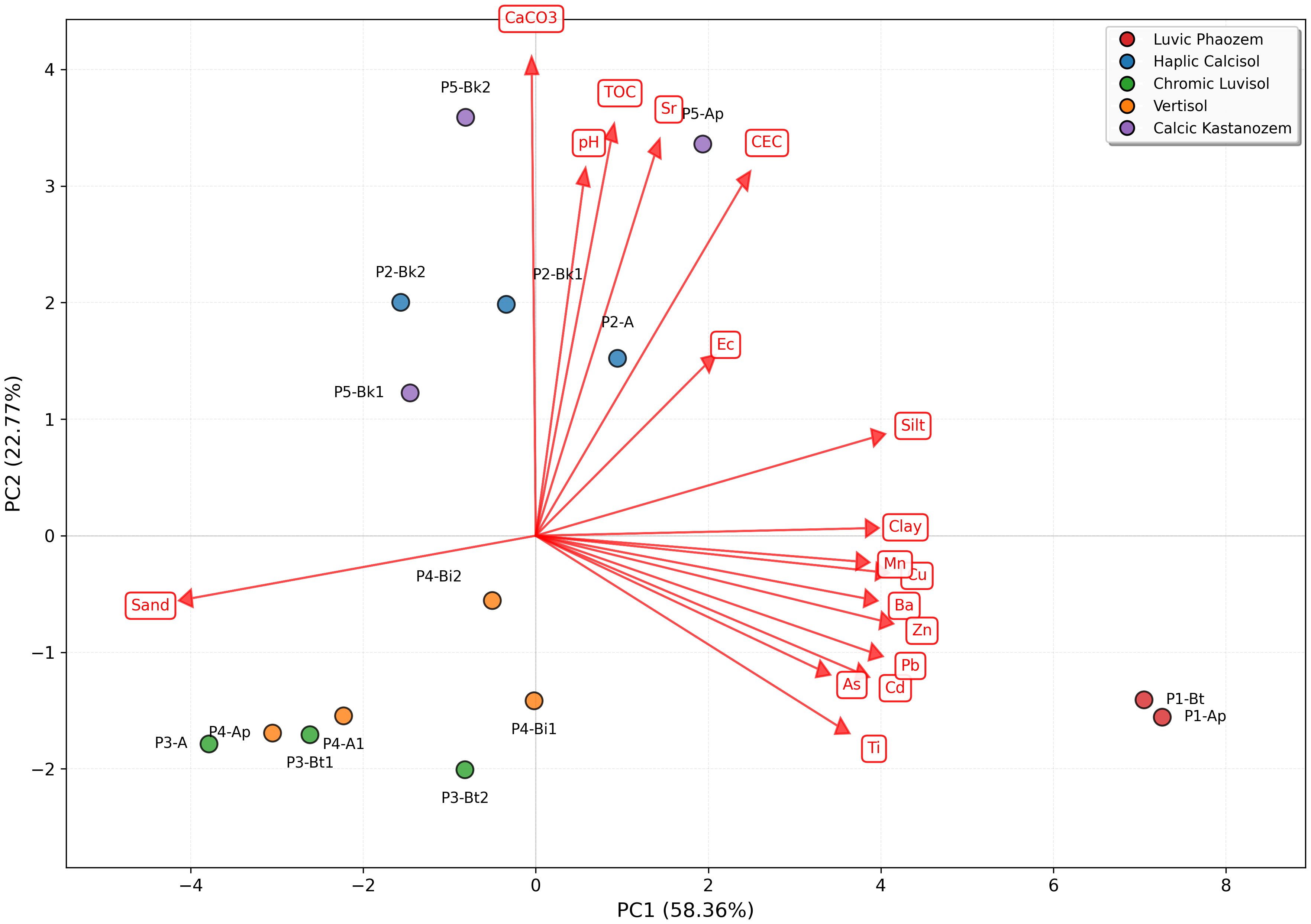

Descriptive statistics (minimum, maximum, mean, standard deviation and coefficient of variation) characterized PTE distributions, with normality assessed using Shapiro-Wilk tests (p < 0.05). One-way ANOVA tested differences among horizons and soil types with Tukey HSD post-hoc tests, while Kruskal-Wallis with Dunn’s tests were used for non-normal data. Pearson correlation coefficients quantified PTE-soil property relationships. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) identified geochemical associations using all PTEs and physicochemical properties for soil horizons. Data were standardized using StandardScaler (scikit-learn 1.3.0, Python 3.9) before analysis. Dataset suitability was validated using Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure (KMO = 0.784, good adequacy) and Bartlett’s test (χ² = 186.3, df = 136, p < 0.001). Two components retained (eigenvalues > 1) explained 81.13% total variance (PC1: 58.36%; PC2: 22.77%) (Table 3). All analyses used Python 3.9 with pandas (2.0.3), numpy (1.24.3), scipy (1.11.1), scikit-learn (1.3.0), matplotlib (3.7.2), and seaborn (0.12.2), with significance threshold α = 0.05.

3 Results and discussion

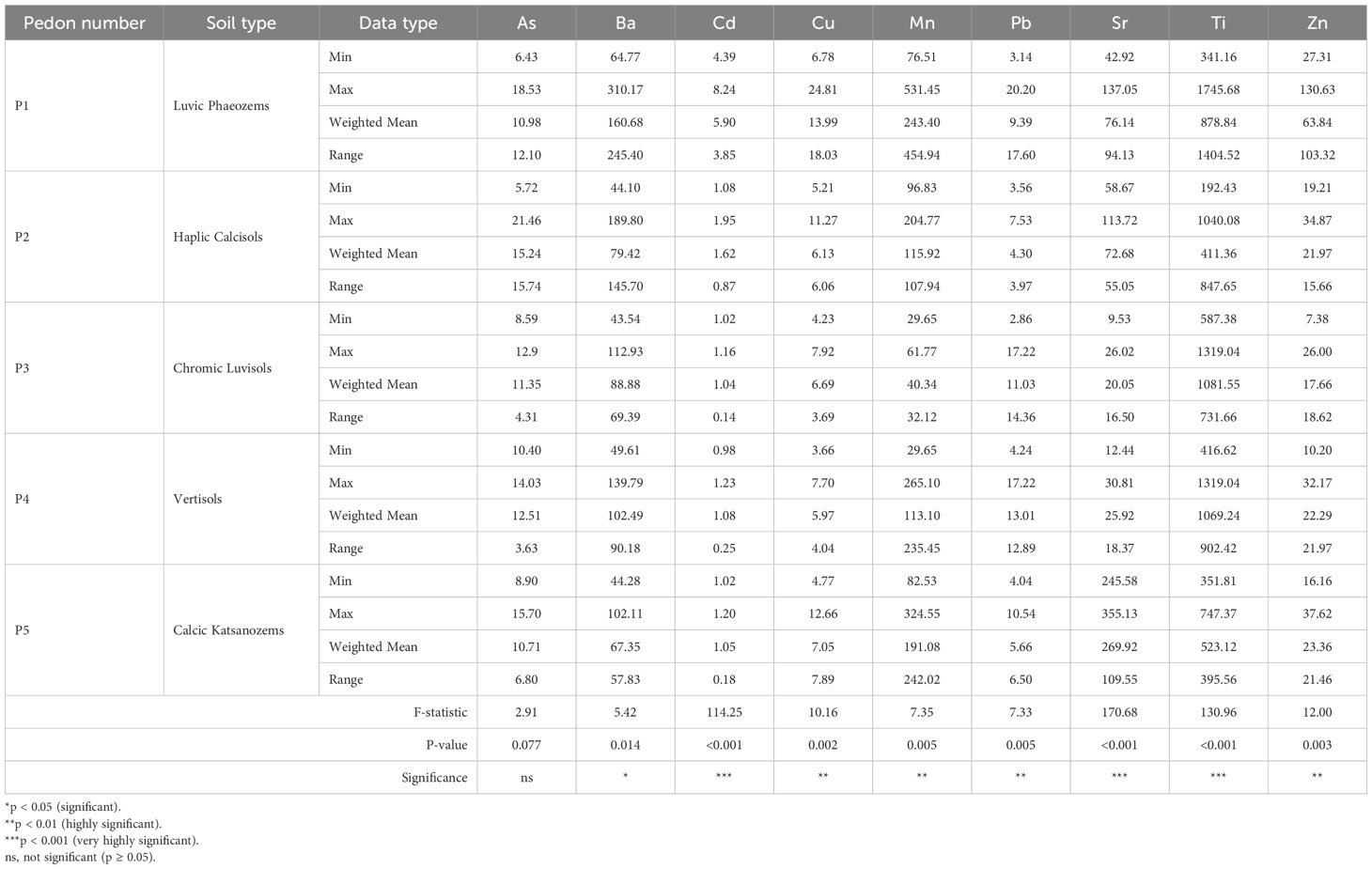

This section describes the analysis of PTEs in five Moroccan soils, focusing on vertical distribution, sources, and ecological risks. Concentrations by horizon and weighted means were used to identify contamination patterns. Statistical tools (ANOVA, Pearson correlation, PCA) helped relate PTE levels to soil properties and validate geochemical indices.

3.1 Distribution of potentially toxic elements across pedons

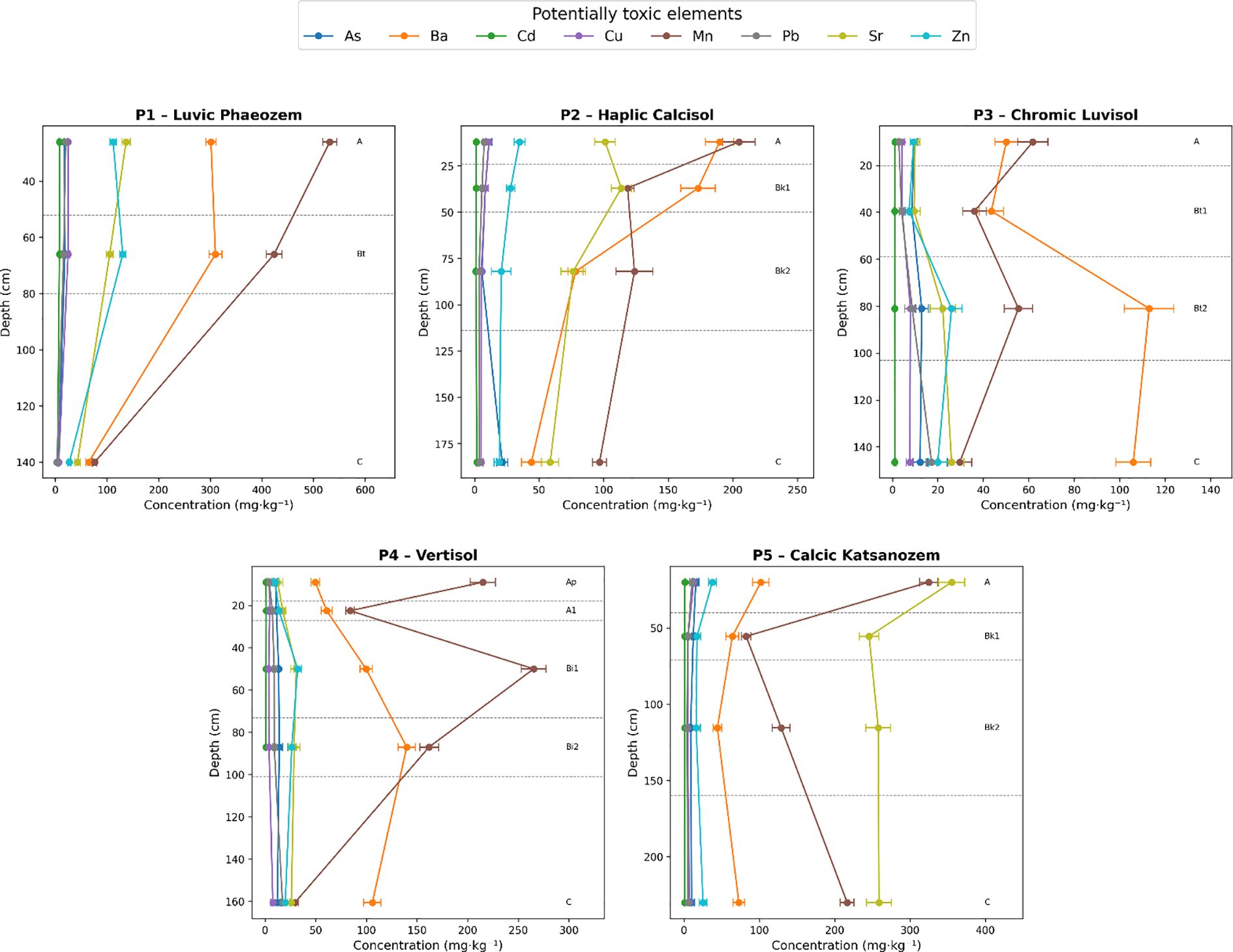

The vertical distribution of PTEs within the studied pedons (Figure 2) demonstrates significant variability influenced by soil types and horizon depths. A comprehensive analysis of horizon-specific concentrations, complemented by weighted mean values (Table 4), allows for a detailed characterization of element distribution patterns and facilitates the identification of potential contamination sources.

Figure 2. Vertical profiles of potentially toxic elements across representative soil types (P1–P5) in central Morocco, with error bars indicating standard deviation (n = 3).

Table 4. Descriptive statistics of potentially toxic element concentrations (mg·kg-1) in five representative pedons.

Notably, As shows pronounced surface enrichment, with concentrations peaking at 18.5 mg·kg-1 in the Ap horizon of Luvic Phaeozems (P1) and reaching 21.46 mg·kg-1 in Haplic Calcisols (P2), substantially exceeding the FAO/WHO guideline value of 10 mg·kg−1 for agricultural soils. These values also exceed previously reported concentrations for Moroccan soils (15). The vertical range of As concentrations varies considerably among pedons, from 12.10 mg·kg−1 in P1 to 15.74 mg·kg−1 in P2, with statistical analysis revealing marginally non-significant differences among pedons (F = 2.91, p = 0.077).

Additionally, Cd concentrations in the Ap horizon of P1 reach 8.24 mg·kg-1, surpassing the WHO safety threshold of 3 mg·kg-1 (35). When examining mean values, a stark disparity emerges: 5.90 mg·kg-1 in P1 compared to 1.62 mg·kg-1 in P2 and 1.04 mg·kg-1 in P3. The range of Cd variation is notably highest in P1 (3.85 mg·kg−1) compared to minimal variation in P3 and P4 (0.14 and 0.25 mg·kg−1, respectively), with ANOVA confirming highly significant differences in Cd concentrations among pedons (F = 114.25, p < 0.001). These figures underscore P1 as the most affected by Cd contamination, likely due to historical fertilizer use, a pattern consistent with findings reported by El Fadili et al. (36). Cu and Pb display similar vertical distribution patterns, with significant surface enrichment in the Ap horizon of P1, where Cu concentrations reach 24.81 mg·kg-1 and Pb concentrations peak at 20.20 mg·kg-1. These concentrations remain below the WHO toxicity thresholds of 100 mg·kg−1 for Cu and 50–100 mg·kg−1 for Pb. The vertical ranges in P1 are 18.03 mg·kg−1 for Cu and 17.6 mg·kg−1 for Pb, with statistical analysis revealing significant differences among pedons for both Cu (F = 10.16, p = 0.002) and Pb (F = 7.33, p = 0.005), with P1 showing significantly higher concentrations than other pedons.

Zn concentrations show also a complex distribution pattern in P1, with maximum values of 130.63 mg·kg−1 observed in deeper horizons (C horizon) rather than at the surface (27.3 mg·kg−1 in Ap horizon), resulting in a vertical range of 103.32 mg·kg−1, suggesting both anthropogenic surface inputs and geogenic contributions at depth. The weighted mean concentration in P1 (63.84 mg·kg−1) remains below the WHO threshold of 300 mg·kg−1. This dual enrichment pattern indicates that while surface layers may receive anthropogenic inputs, subsurface accumulation likely results from natural pedogenic processes and parent material weathering (F = 12.00, p = 0.003). Spearman correlation analysis confirmed these vertical distribution patterns (Supplementary Table S1). Concentrations of Cd, Cu, and Pb decreased significantly with depth in P1 and P2 (p = -0.50 to -1.00, p < 0.05), consistent with anthropogenic surface inputs. However, Pb showed soil-type-specific behavior: while decreasing in P1 and P2, it increased significantly with depth in P3 and P4 (p = 1.00, p < 0.01), indicating pedogenic redistribution through clay illuviation. Researchers commonly observe surface accumulation of these elements globally, attributing it to agrochemical use and atmospheric deposition, along with the influence of soil properties and environmental conditions (37).

In contrast, Ba, Sr, and Ti exhibit distribution patterns that suggest geogenic sources and pedogenic controls. For instance, Ba concentrations consistently decrease with depth across all pedons, reflecting limited mobility and primary mineral origins (38). Statistical analysis confirms significant differences in Ba distribution among pedons (F = 5.42, p = 0.014).

Conversely, Sr concentrations increase with depth, particularly in carbonate-rich profiles. In P3, Sr rises from 9.53 mg·kg-1 at the surface to 26.02 mg·kg-1 in the C horizon (range: 16.50 mg·kg−1), suggesting a release from carbonate minerals (39). This depth-related increase shows highly significant differences among soil types (F = 170.68, p < 0.001), with P5 exhibiting the highest mean Sr concentration at 269.92 mg·kg−1 and a vertical range of 109.55 mg·kg−1. This pattern correlates with carbonate distribution and soil pH, supporting the hypothesis of Sr mobilization through carbonate dissolution under the semi-arid conditions prevalent in the study area.

Mn displays a variable distribution, showing enrichment in the surface horizons of organic-rich soils (P1: weighted mean 243.40 mg·kg−1, range 454.94 mg·kg−1) while accumulating at greater depths in clay-rich Vertisol (P4: weighted mean 113.10 mg·kg−1, range 235.45 mg·kg−1). This behavior likely results from redox dynamics and mineral dissolution processes (F = 7.35, p = 0.005), as documented by Rashed et al. (40). Ti shows highly significant variation among pedons (F = 130.96, p < 0.001), with weighted means ranging from 411.36 mg·kg−1 in P2 to 1081.55 mg·kg−1 in P3, and vertical ranges from 395.56 mg·kg−1 in P5 to 1404.52 mg·kg−1 in P1, reflecting differences in parent material composition and clay mineralogy rather than anthropogenic inputs.

These diverse vertical distribution behaviors highlight the significant influence of soil physicochemical properties, especially organic matter, carbonate, and clay content on the mobility and retention of potentially toxic element. Similar geochemical controls have been reported in other Moroccan agricultural soils (41, 42).

3.2 Relationships between PTEs and soil properties

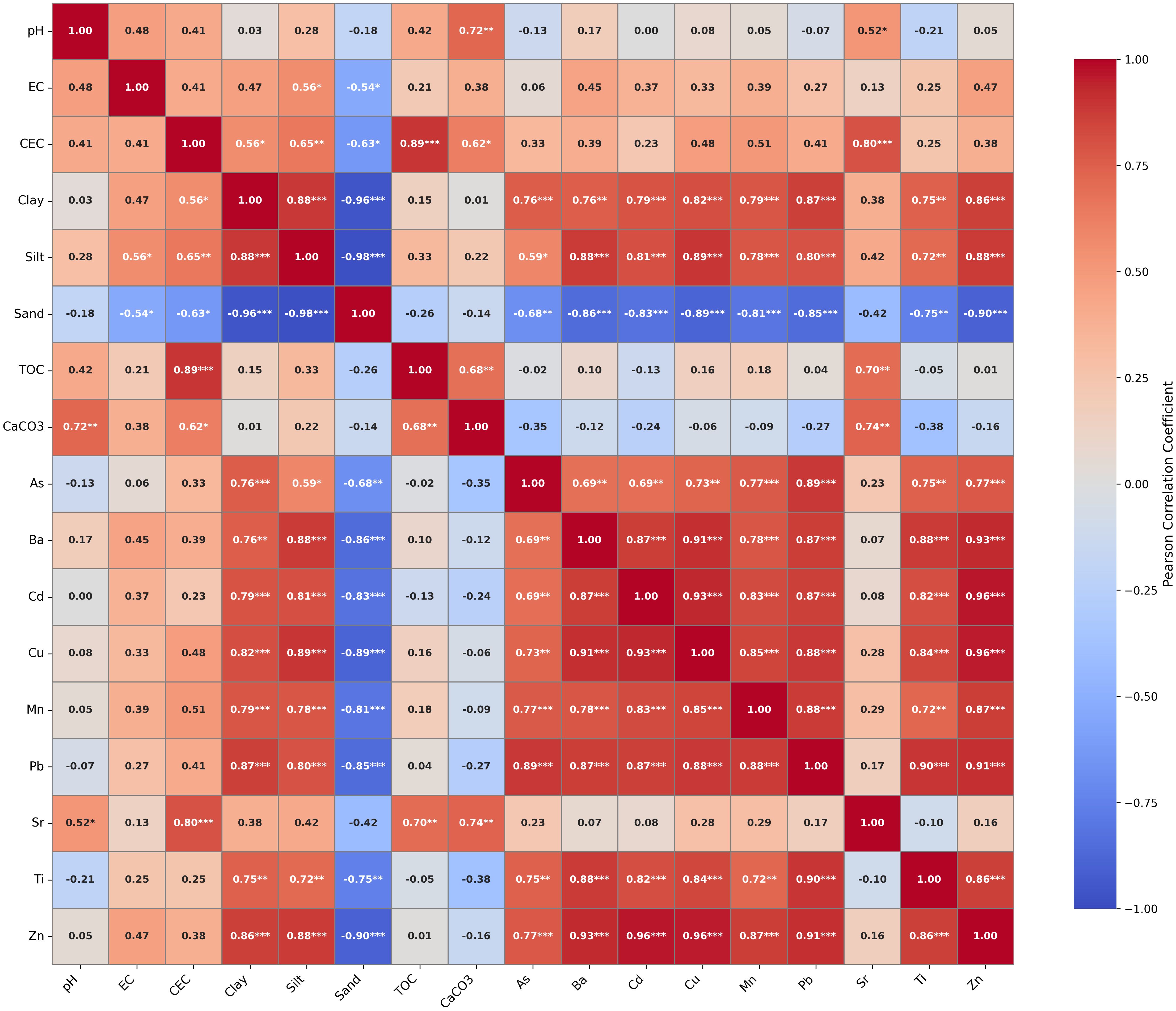

A comprehensive Pearson correlation analysis was performed to quantify relationships between potentially toxic elements and soil physicochemical properties (Figure 3). The correlation heatmap reveals strong associations among several PTEs, particularly Zn, Cu, Cd and Mn. Notably, high correlation coefficients were observed for Zn–Cu (r = 0.96, p < 0.001), Zn–Cd (r = 0.96, p < 0.001), and Cu–Cd (r = 0.93, p < 0.001). The consistent correlation between Mn, Cd, and Cu (r = 0.84 -0.88, p < 0.001) indicates that these elements exhibit similar geochemical behavior. This inter-element co-variation reflects shared retention mechanisms during pedogenic transformations, with these metals showing comparable affinity for fine-textured soil fractions, suggesting their accumulation is controlled by similar binding phases such as clay minerals and oxides (43).

Figure 3. Pearson correlation heatmap between potentially toxic elements and soil physicochemical properties. Correlation coefficients are color-scaled from –1 to +1. Significant correlations are marked: p < 0.05 (*); p < 0.01 (**); p < 0.001 (***); non-significant values are unmarked.

Soil texture exerts strong control on PTE distribution patterns. Clay content shows strong positive correlations with several PTEs, including Mn (r = 0.78), Zn (r = 0.86), Cu (r = 0.79), Cd (r = 0.81), Pb (r = 0.74), and As (r = 0.70), reflecting the critical role of clay minerals in metal retention through surface adsorption due to their high surface area and charged particles (44, 45). Silt content also correlates positively with most metals (r = 0.72–0.88), while sand shows strong negative correlations (r = -0.68 to -0.98), confirming that fine-textured soils favor metal accumulation. Notably, TOC displays weak correlations with these elements (|r| < 0.2), indicating that organic matter contributes minimally to their spatial distribution compared to mineral phases. This contrasts with other unpolluted soils where organic matter played a more dominant role in metal retention (46, 47), suggesting that carbonate content and clay mineralogy are the primary controls in our semi-arid agricultural soils. Sr exhibits negligible correlations with PTEs but shows strong positive correlations with CaCO3 content (r = 0.82, p < 0.001) and pH (r = 0.76, p < 0.001), consistent with conservative lithogenic behavior controlled by carbonate dissolution (48, 49).

CEC shows only moderate relationships with most PTEs (r = 0.23–0.51), except for Sr (r=0.88), suggesting that cation-exchange processes play a secondary role compared to specific adsorption on clay and oxide surfaces. This indicates that metal retention is primarily controlled by surface complexation on clay minerals and oxides rather than simple electrostatic exchange mechanisms (50). Similarly, pH shows negligible correlations with most PTEs (|r| < 0.15), while CaCO3 exhibits only weak negative correlations with metals (r = -0.16 to -0.35). This limited influence of pH and carbonates suggests that under the prevailing alkaline conditions, mineral surface interactions dominate over pH-dependent precipitation processes, with metals predominantly immobilized through stable adsorption complexes (9, 51).

3.3 Vertical stratification of trace elements based on the distribution index

The distribution index (DI) identifies soil horizons enriched with potentially toxic elements (Table 5), highlighting layers where plant roots may encounter elevated metal concentrations. In Luvisols, the Ap and Bt horizons with DI values greater than 3 for Cd, Pb, and Zn coincide with the central root zone, posing a significant risk for phytotoxicity. Studies in the Gharb plain region have documented that such elevated concentrations in agricultural soils exceed WHO/FAO limits and are associated with reduced productivity in wheat, barley, and sugar beet, the main crops cultivated in Kenitra (52, 53). High DI values in these surface horizons can disrupt nutrient uptake, inhibit photosynthetic enzymes, and induce oxidative stress in plants, as demonstrated in similar semi-arid systems (54, 55).

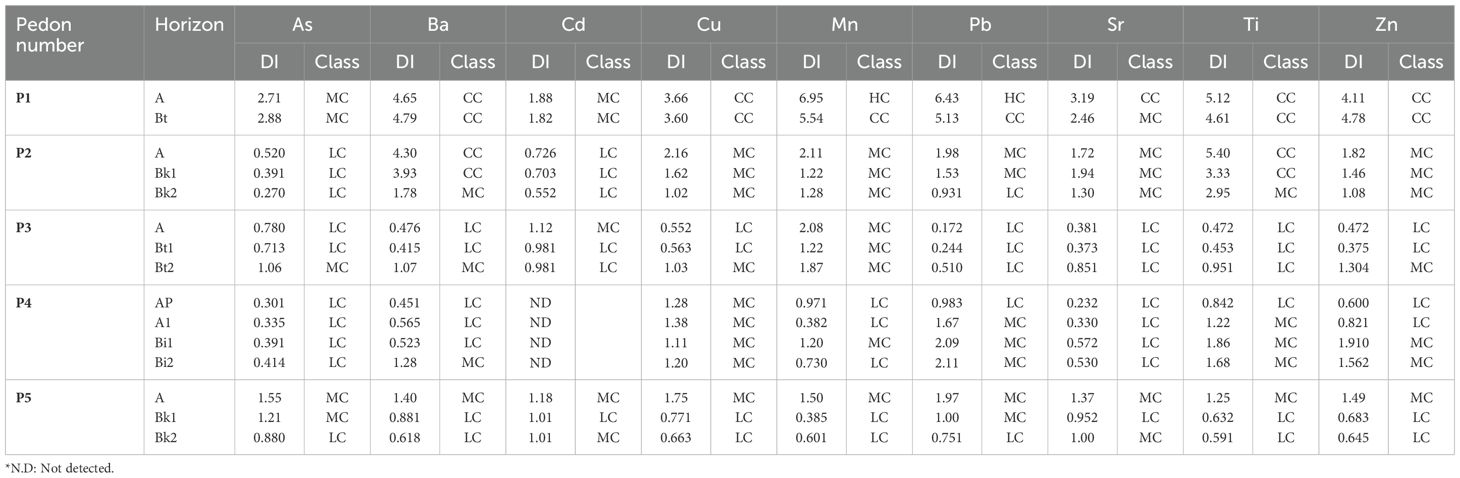

Table 5. Distribution index of trace elements in soil horizons from five representative pedons in central Morocco.

In contrast, the Calcisols and Vertisols tend to concentrate metals in deeper B horizons, where the DI is less than 1 in the Ap horizon. This reflects the carbonate-mediated immobilization that largely spares the rhizosphere, metal-carbonate complexes and the high cation-exchange capacity of smectic clays limit metal bioavailability (56, 57). Kastanozems exhibits intermediate patterns with moderate surface DI values (between 1 and 2), driven by organic-mineral interactions and partially buffered by carbonates. DI values near classification thresholds (e.g., DI ≈ 1 or ≈ 3) carry inherent uncertainty due to analytical variability and should be interpreted with caution. These differing stratification patterns stem from fundamental soil properties. In organic-rich Luvisols, abundant Mn-oxide and Fe-oxide phases facilitate trace metal adsorption and co-precipitation under fluctuating redox conditions. Conversely, the high pH and calcium carbonate (CaCO3) content in carbonate-rich Calcisols and Kastanozems promote stable metal-carbonate precipitation and surface complexation (58, 59). Vertisols, characterized by expansive clay minerals and variable redox micro-zones, display more heterogeneous DI profiles, indicating episodic mobilization during wetting and drying cycles (60). Understanding these mechanisms enables practitioners to interpret DI thresholds as indicators of horizons that require detailed ecological risk screening and remediation. In practical terms, focusing on horizons with elevated DI for ecological risk assessments and plant bioassays optimizes resource allocation. Soils with Ap or upper Bt horizons exceeding a DI of 2 for key PTEs should be prioritized for detailed speciation analyses and bioaccumulation testing. This approach translates DI patterns into actionable remediation protocols.

3.4 Sources of potential toxic elements

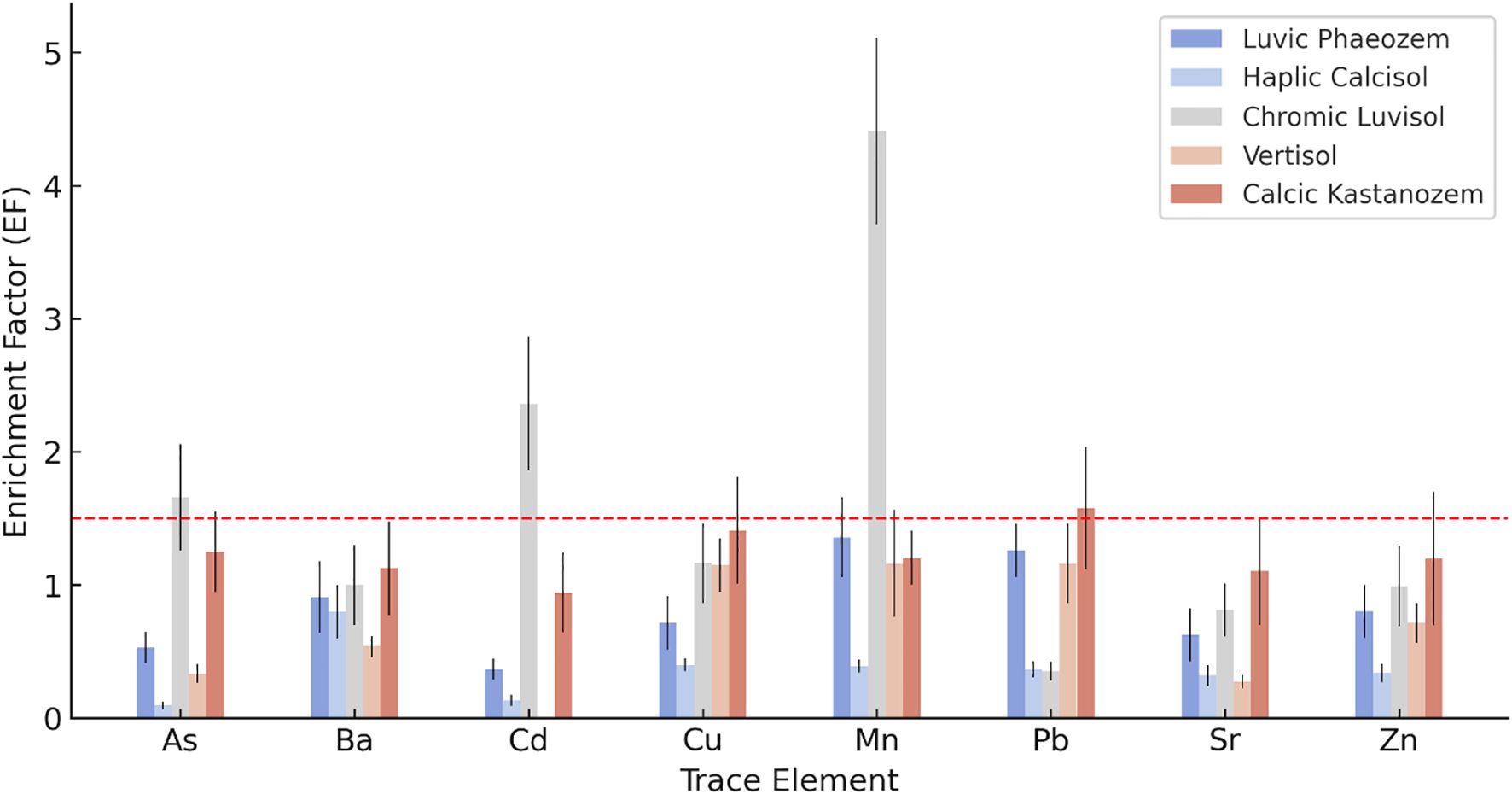

Enrichment Factor (EF) assessment (Figure 4) across five soil types highlights significant variability in trace element accumulation due to both natural processes and human activities. EFs effectively differentiate geogenic from anthropogenic contributions, revealing distinct patterns by soil type. Chromic Luvisols (P3) showed anthropogenic enrichment for Cd (EF = 2.36) and Mn (EF = 4.41). Elevated Cd levels align with findings in intensively cultivated regions where agricultural practices introduce Cd impurities (61). The Mn enrichment likely reflects the use of pesticides, as reported in other studies (62, 63).

Figure 4. Enrichment factors (EF) of potentially toxic elements (PTEs) in surface horizons of five representative soil types. Error bars represent standard deviation based on three replicates (n = 3). The threshold line at EF = 1.5 distinguishes geogenic (EF ≤ 1.5) from anthropogenic (EF > 1.5) sources.

In the Calcic Kastanozems (P5), Pb exhibited moderate enrichment (EF = 1.58), marginally above the anthropogenic threshold; while this suggests possible anthropogenic input, the proximity to the 1.5 cutoff indicates that natural variability or localized historical atmospheric deposition cannot be ruled out (64). All other elements displayed EF ≤ 1.5, suggesting geogenic sources, although the borderline As value (EF = 1.25) may reflect either natural baseline variation or minor anthropogenic input from past pesticide use (65). Luvic Phaeozems (P1) had EF values near or below the threshold, indicating geogenic origins for all elements. However, slight elevations in Pb (EF = 1.26) and Mn (EF = 1.36) remain within the range of natural variability but could suggest minor anthropogenic influences (15, 62). The Haplic Calcisols (P2) showed all EF values ≤ 1.5, underscoring natural geogenic sources consistent with the region’s carbonate-rich parent materials and the absence of nearby industrial activities, its carbonate-rich matrix limits element mobility (66). Similarly, the Vertisols (P4) exhibited EF ≤ 1.5 for all measured elements, reflecting its derivation from weathered basaltic or clay-rich parent materials and its location in areas with minimal anthropogenic pressure, its strong binding capacity for trace metals arises from high clay content (67). These findings emphasize the need to consider soil-specific contexts and management histories when interpreting contamination sources.

3.5 Mobility of potentially toxic elements in soil

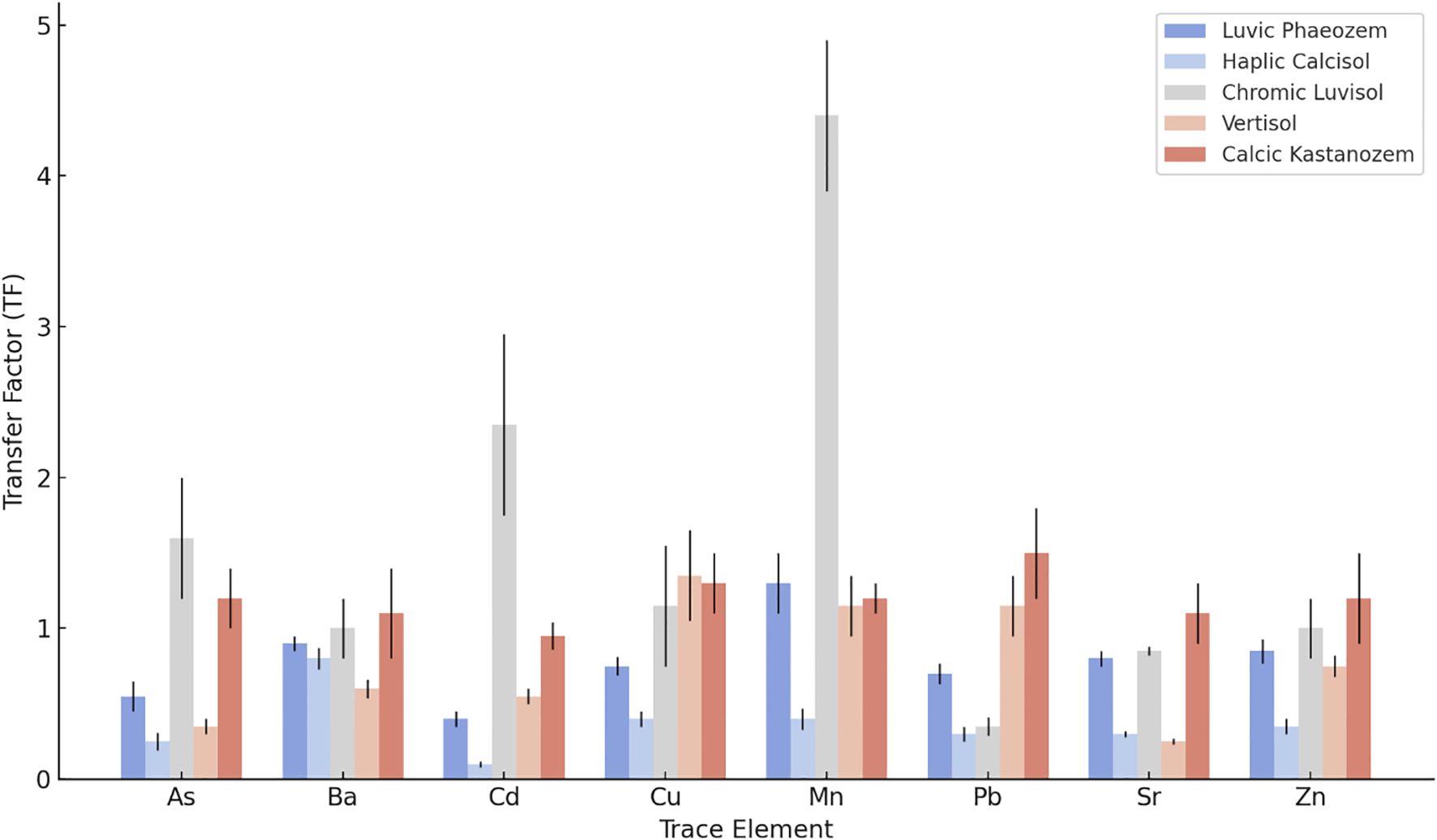

To evaluate the vertical mobility and potential bioavailability of trace elements, Transfer Factor (TF) values were calculated for each soil profile (Figure 5). Cd was identified as the most mobile element, with TF values exceeding 1 in the Chromic Luvisols, indicating significant accumulation at the surface and potential risk of uptake by plants. This high mobility correlates with the relatively alkaline pH and moderate CEC of Luvisols compared to carbonate-rich soils, conditions that favor Cd solubility and vertical redistribution (68, 69). In other profiles, such as the Calcic Kastanozems and the Luvic Phaeozems, Cd displays moderate mobility, with TF values below 1 that reflect limited redistribution due to alkaline pH and carbonate buffering (70). Similarly, Pb and Zn show moderate TF values in various soils, particularly Vertisols and Kastanozems. This suggests partial mobility influenced by their association with organic matter and clay particles, the high clay content and elevated CEC in these soils enhance metal retention while allowing limited vertical movement (71). Although this partial mobility is concerning, crops tend to uptake these elements at lower rates than Cd. While Zn is essential at low concentrations, excessive accumulation can become toxic to plants. Zn mobility was also observed in Haplic Calcisols and Chromic Luvisols, consistent with its known bioavailability in carbonate-buffered conditions (72). In the case of the Calcisols and Vertisols, As and Ba exhibit low TF values of less than 0.5, indicating strong retention due to sorption to Fe and Al oxides, coupled with low solubility in calcareous environments. Such immobility aligns with findings in agricultural soils, where mineral interactions prevail over leaching processes (73, 74). Mn displays the highest TF value in the Chromic Luvisol, exceeding 4, likely due to surface redistribution driven by redox cycling and organic complexation (75); while soil Mn concentrations remain below typical phytotoxicity thresholds (400–500 mg/kg in sensitive crops), the high mobility warrants monitoring in intensive cropping systems (76).

Figure 5. Transfer factor (TF) values of potentially toxic elements across different soil types. Error bars represent standard deviation based on three replicates (n = 3).

Sr also has moderate TF values, slightly above 1 in the Kastanozem and Phaeozem, reflecting some release from carbonate matrices (77). Sr toxicity in crops is generally low due to its chemical similarity to calcium, and soil Sr concentrations remain well below levels associated with plant toxicity or human health concerns (>350 mg/kg), posing minimal phytotoxic risk, at the concentrations observed in this study (78). These results confirm that PTE mobility is governed primarily by soil-specific properties (pH, CEC and carbonate content) rather than by regional climatic factors, highlighting the need for site-specific management approaches.

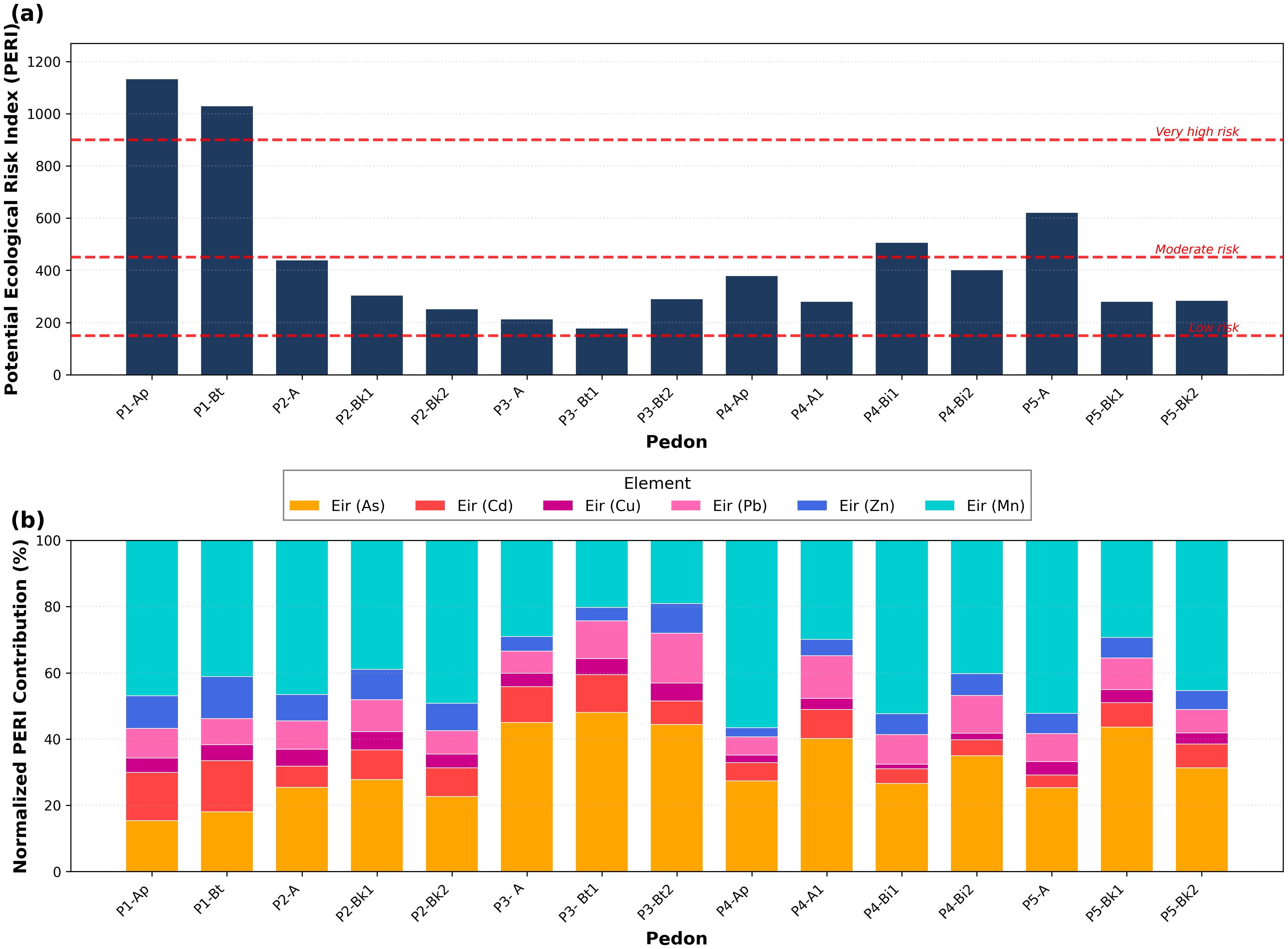

3.6 Soil-specific ecological risk assessment of potentially toxic elements

The Potential Ecological Risk Index (PERI) assessment reveals pronounced differences in both absolute risk magnitude and element-specific contributions across soil types and horizons (Figure 6). Absolute PERI values (Figure 6a) demonstrate that the Luvic Phaeozems (P1) exhibits the highest ecological risk, with both surface and subsurface horizons classified as very high risk (PERI > 900): P1-Ap (1133.14) and P1-Bt (1029.63). These values exceed typical ranges for Moroccan agricultural soils (53). The Calcic Kastanozems surface horizon (P5-A, PERI = 621.19) demonstrates considerable risk (450 < PERI < 900), while the Haplic Calcisols (P2) display moderate risk in the surface horizon (P2-A, PERI = 439.63) with progressive risk reduction in deeper carbonate-rich horizons. The Chromic Luvisols horizons show the lowest absolute values: P3-Bt1 (178.69), P3-A (212.67), and P3-Bt2 (290.23).

Figure 6. Potential ecological risk index (PERI) assessment across soil horizons. (a) Absolute PERI values with risk thresholds: low (<150), moderate (150-450), considerable (450-900), and very high (>900). (b) Normalized PERI contributions showing relative element contributions to total risk across pedons (P1-P5) and horizons.

The normalized PERI contributions (Figure 6b) reveal distinct element-specific risk profiles. In the Luvic Phaeozems (P1), Mn emerges as the dominant contributor (47% in P1-Ap, 41% in P1-Bt). However, this dominance reflects high concentrations rather than high intrinsic toxicit. Mn’s toxicity coefficient is relatively low, and its behavior is strongly redox-dependent, varying seasonally with soil moisture conditions (76). As and Cd contribute nearly equally (15-16% each) and warrant particular attention due to their links to crop contamination and human health risks through the food chain. Cd accumulation in the root zone poses direct risks for cereals and vegetables, while As exposure through contaminated crops represents a critical human exposure pathway (53, 79).

The Chromic Luvisols (P3) presents a contrasting pattern, with As dominance across all horizons (44-48%), coupled with moderate Cd contributions (11-12%). This pronounced As contamination raises food safety concerns for wheat and barley cultivation, particularly in irrigated areas (80). The Vertisols (P4) and Calcic Kastanozems (P5) exhibit transitional profiles with marked vertical heterogeneity. P4 shows surface Mn dominance (57%) transitioning to As-dominated contributions in deeper horizons (27-40%), a stratification pattern with important implications for root crops and deep-rooting species. P5 demonstrates surface Mn influence (52%) shifting toward balanced As-Mn contributions in subsurface horizons, likely reflecting carbonate-mediated immobilization processes.

The soil-type differentiation aligns well with previous findings from EF and DI analyses, reinforcing the robustness of the multi-index contamination assessment approach. From a risk management perspective, differentiated strategies are required. The Luvic Phaeozems (P1) requires multi-element management focusing on Cd and As mitigation given their agricultural and human health implications. Chromic Luvisols (P3) requires As-focused monitoring with speciation analysis and crop-specific uptake assessment. Horizons classified as very high risk (P1-Ap, P1-Bt) require urgent assessment of plant bioaccumulation through monitoring of locally produced food crops and consideration of soil amendment strategies or temporary land-use restrictions for sensitive crops.

3.7 Principal component analyses

Principal component analysis (PCA) reveals distinct geochemical associations controlling PTE distribution across the studied soil profiles (Table 6). The first two principal components explain 81.13% of the total variance, with PC1 accounting for 58.36% and PC2 for 22.77%, providing a comprehensive framework for understanding metal behavior in these semi-arid agricultural soils.

Table 6. PCA variable loadings for the first two principal components (PC1 and PC2), based on trace element concentrations.

PC1 (58.36% variance) shows strong positive correlations for multiple PTEs, Zn (0.307), Cu (0.303), Pb (0.299), Ba (0.292), Cd (0.287), and Mn (0.286), alongside silt (0.298) and clay (0.294). The PCA biplot (Figure 7) shows the Chromic Luvisols horizons (P3-A, P3-Bt1, P3-Bt2) clustering in the lower-left quadrant, strongly associated with this metal enrichment axis. This pattern reflects anthropogenic metal inputs from agricultural intensification and their association with fine-textured horizons due to their high specific surface area and metal-sorbing sites (81).

Figure 7. Principal component analysis biplot of soil samples based on potentially toxic elements and physicochemical parameters.

PC2 (22.77% variance) is dominated by CaCO3 (0.495), TOC (0.449), CEC (0.393), and Sr (0.383), defining a geochemical buffering capacity axis. The upper portion of the biplot shows clear clustering of carbonate-rich horizons from the Haplic Calcisols (P2-Bk1, P2-Bk2), Calcic Kastanozems (P5-Bk1, P5-Bk2), and Vertisols (P4-Bi1, P4-Bi2). This axis distinguishes subsurface horizons with enhanced metal immobilization through carbonate precipitation, surface complexation, and organic matter chelation (67, 82, 83). Sr co-associates with carbonates as Sr2+ readily substitutes for Ca2+ in carbonate minerals (84).

The biplot clearly differentiates soil types based on pedogenic characteristics. The Luvic Phaeozems (P1-Ap, P1-Bt) occupies the far-right position along PC1, while the Chromic Luvisols separates from carbonate-rich soils along both axes, reflecting fundamental differences in soil-forming processes. The PCA demonstrates that PTE distribution is governed by two principal mechanisms whereby surface accumulation is driven by anthropogenic inputs with preferential retention in fine-textured horizons (PC1), while subsurface stabilization is controlled by carbonates and organic matter (PC2). Horizons plotting high on PC1 represent zones of elevated metal bioavailability and potential phytotoxicity risk, requiring targeted monitoring, while horizons scoring high on PC2 indicate enhanced metal retention capacity and lower immediate environmental risk. This interpretation aligns with findings from other semi-arid agricultural regions (64, 85, 86).

4 Conclusion

This study demonstrates that soil typology fundamentally controls PTE contamination patterns, mobility, and ecological risks in semi-arid agricultural soils of north-central Morocco. Luvic Phaeozems exhibited very high ecological risk with Cd, As, and Pb, posing immediate threats to crop quality and food chain transfer. Haplic Calcisols showed the highest As contamination but moderate risk due to carbonate-mediated immobilization. Chromic Luvisols presented the lowest absolute risk yet displayed As-dominated profiles with clear anthropogenic enrichment signatures for Cd and Mn. Vertisols exhibited predominantly geogenic sources with strong natural buffering capacity.

Source apportionment identified Cd as the most mobile element, with clay content emerging as the dominant retention mechanism. Principal Component Analysis revealed two geochemical associations controlling PTE behavior, anthropogenic contamination with clay retention, and carbonate-organic matter buffering controlling mobility. Multi-fold differences in contaminant concentrations between soil types and dramatic ecological risk variations demonstrate that uniform assessment approaches fail to capture pedological controls, mandating soil-type-specific management strategies.

Priority actions must target Luvic Phaeozems for immediate remediation and Chromic Luvisols for crop monitoring. This integrated framework provides a replicable model for soil-type-informed risk assessment in pedologically diverse semi-arid regions, establishing the first comprehensive baseline for north-central Moroccan agricultural soils essential for sustainable land use and food security.

5 Limitation statement

Although the purpose of this study was to evaluate pedon-scale pollution, source and mobility of contaminants, spatial coverage can be seen as a limitation, which will require future research to cover the remaining areas by collecting more samples that will be affordable for statistical analyses. In addition, a one-season data collection makes the study partial. Hence, in the future, a year-round sampling and investigation will help to generate adequate information for sustainable soil pollution management. The geochemical indices employed (EF, DI, TF, PERI) rely on standard assumptions and toxicity coefficients, and source attribution was based on indirect inference rather than definitive methods such as isotope analysis. Despite these constraints, this study establishes the first comprehensive baseline data for representative soil types in this region, demonstrates the fundamental role of soil typology in controlling PTE behavior, and provides a validated methodological framework applicable to other semi-arid agricultural systems globally.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

LM: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AB: Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. FK: Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. The OCP Nutricrop sponsored this work through the project of CaDmiUm and Trace Elements Bio-availability and Transfer In Soil-PlaNt SystEm (DUNE), Morocco.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to all those who have supported and contributed to this research, especially the Laboratory technicians of the Centre of Excellence Soil and Fertilizer Research in Africa Soil Spectroscopic Laboratory of the Mohammed VI Polytechnic University, Morocco. We are also indebted to extend our gratitude to OCP Nutricrop for their financial support through the project of CaDmiUm and Trace Elements Bioavailability and Transfer In Soil-PlaNt SystEm (DUNE).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fsoil.2025.1672832/full#supplementary-material.

References

1. Xu Y, Dai S, Meng K, Wang Y, Ren W, Zhao L, et al. Occurrence and risk assessment of potentially toxic elements and typical organic pollutants in contaminated rural soils. Sci Total Environ. (2018) 630:618–29. doi: 10.1016/J.SCITOTENV.2018.02.212

2. Zhang L, Yang Z, Peng M, and Cheng X. Contamination levels and the ecological and human health risks of potentially toxic elements (PTEs) in soil of baoshan area, southwest China. Appl Sci (Switzerland). (2022) 12:1693. doi: 10.3390/app12031693

3. Wan M, Hu W, Wang H, Tian K, and Huang B. Comprehensive assessment of heavy metal risk in soil-crop systems along the Yangtze River in Nanjing, Southeast China. Sci Total Environ. (2021) 780:146567. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.146567

4. Natasha N, Shahid M, Murtaza B, Bibi I, Khalid S, Al-Kahtani AA, et al. Accumulation pattern and risk assessment of potentially toxic elements in selected wastewater-irrigated soils and plants in Vehari, Pakistan. Environ Res. (2022) 214:114033. doi: 10.1016/J.ENVRES.2022.114033

5. Dong JW, Gao PP, Sun HX, Zhou C, Zhang XY, Xue PY, et al. Characteristics and health risk assessment of cadmium, lead, and arsenic accumulation in leafy vegetables planted in a greenhouse. Huan Jing Ke Xue. (2022) 43 1:481–9. doi: 10.13227/J.HJKX.202106002

6. El Hamzaoui EH, El Baghdadi M, and Hilali A. Assessment of trace element contamination and associated health risks in agricultural soils of the Beni Moussa Sub-Perimeter, Morocco. Model Earth Syst Environ. (2025) 11:183. doi: 10.1007/S40808-025-02367-2

7. Gong C, Xia X, Lan M, Shi Y, Lu H, Wang S, et al. Source identification and driving factor apportionment for soil potentially toxic elements via combining APCS-MLR, UNMIX, PMF and GDM. Sci Rep. (2024) 14:1–13. doi: 10.1038/S41598-024-58673-9

8. Shi B, Yang X, Liang T, Liu S, Yan X, Li J, et al. Source apportionment of soil PTE in a northern industrial county using PMF model: Partitioning strategies and uncertainty analysis. Environ Res. (2024) 252:118855. doi: 10.1016/J.ENVRES.2024.118855

9. Palansooriya KN, Shaheen SM, Chen SS, Tsang DCW, Hashimoto Y, Hou D, et al. Soil amendments for immobilization of potentially toxic elements in contaminated soils: A critical review. Environ Int. (2020) 134:105046. doi: 10.1016/J.ENVINT.2019.105046

10. Sanad H, Moussadek R, Mouhir L, Oueld Lhaj M, Dakak H, El Azhari H, et al. Assessment of soil spatial variability in agricultural ecosystems using multivariate analysis, soil quality index (SQI), and geostatistical approach: A case study of the mnasra region, gharb plain, Morocco. Agronomy. (2024) 14:1112. doi: 10.3390/agronomy14061112

11. Barakat A, Ennaji W, Krimissa S, and Bouzaid M. Heavy metal contamination and ecological-health risk evaluation in peri-urban wastewater-irrigated soils of Beni-Mellal city (Morocco). Int J Environ Health Res. (2020) 30:372–87. doi: 10.1080/09603123.2019.1595540

12. El Hamzaoui EH, El Baghdadi M, Oumenskou H, Aadraoui M, and Hilali A. Spatial repartition and contamination assessment of heavy metal in agricultural soils of Beni-Moussa, Tadla plain (Morocco). Model Earth Syst Environ. (2020) 6:1387–406. doi: 10.1007/s40808-020-00756-3

13. Ennaji W, Barakat A, El Baghdadi M, and Rais J. Heavy metal contamination in agricultural soil and ecological risk assessment in the northeast area of Tadla plain, Morocco. J Sedimentary Environments. (2020) 5:307–20. doi: 10.1007/s43217-020-00020-9

14. Hilali A, El Baghdadi M, and Halim Y. Environmental monitoring of heavy metals distribution in the agricultural soil profile and soil column irrigated with sewage from the Day River, Beni-Mellal City (Morocco). Model Earth Syst Environ. (2023) 9:1859–72. doi: 10.1007/s40808-022-01592-3

15. Hilali A, El Baghdadi M, Barakat A, Ennaji W, and El Hamzaoui EH. Contribution of GIS techniques and pollution indices in the assessment of metal pollution in agricultural soils irrigated with wastewater: case of the Day River, Beni Mellal (Morocco). EuroMediterr J Environ Integr. (2020) 5:52. doi: 10.1007/s41207-020-00186-8

16. Barakat A, Ennaji W, El Jazouli A, Amediaz R, and Touhami F. Multivariate analysis and GIS-based soil suitability diagnosis for sustainable intensive agriculture in Beni-Moussa irrigated subperimeter (Tadla plain, Morocco). Model Earth Syst Environ. (2017) 3. doi: 10.1007/s40808-017-0272-5

17. Namous M, Hssaisoune M, Pradhan B, Lee CW, Alamri A, Elaloui A, et al. Spatial prediction of groundwater potentiality in large semi-arid and karstic mountainous region using machine learning models. Water (Switzerland). (2021) 13:2273. doi: 10.3390/w13162273

18. Bouchaou L, Michelot JL, Qurtobi M, Zine N, Gaye CB, Aggarwal PK, et al. Origin and residence time of groundwater in the Tadla basin (Morocco) using multiple isotopic and geochemical tools. J Hydrol (Amst). (2009) 379:323–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jhydrol.2009.10.019

19. Hakkou M, Maanan M, Belrhaba T, El khalidi K, El Ouai D, and Benmohammadi A. Multi-decadal assessment of shoreline changes using geospatial tools and automatic computation in Kenitra coast, Morocco. Ocean Coast Manag. (2018) 163:232–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2018.07.003

20. El Azzouzi M, El Idrissi Y, Baghdad B, El Hasini S, Saufi H, and El Azzouzi EH. Assessment of trace metal contamination in peri-urban soils in the region of Kenitra - Morocco. Mediterr J Chem. (2019) 8:108–14. doi: 10.13171/mjc8219042505mea

21. El Achheb A, Jacky M, and Mudry J-N. Processus de salinisation des eaux souterraines dans le bassin Sahel Doukkala (Maroc occidental) (2001). Available online at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/237779841 (Accessed January 06, 2025).

22. Jones A, Breuning-madsen H, Brossard M, Dampha A, Dewitte O, Hallet SH, et al. Soil atlas of africa. Luxembourg: Publication Office of the European Union (2013). doi: 10.2788/52319.

23. WRB. World reference base for soil resources. In: International soil classification system for naming soils and creating legends for soil maps, 4th edition. International Union of Soil Sciences (IUSS, Vienna, Austria (2022).

24. Bouyoucos GJ. Hydrometer method improved for making particle size analyses of soils 1. Agron J. (1962) 54:464–5. doi: 10.2134/AGRONJ1962.00021962005400050028X

25. Chapman HD. Cation-exchange capacity. In: Methods of soil analysis: Part 2 Chemical and microbiological properties. Madison, WI, USA: American Society of Agronomy (1965). p. 891–901.

26. Kowalska JB, Mazurek R, Gąsiorek M, and Zaleski T. Pollution indices as useful tools for the comprehensive evaluation of the degree of soil contamination-A review. Environ Geochem Health. (2018) 40:2395–420. doi: 10.1007/S10653-018-0106-Z

27. Onjia A, Huang X, Trujillo González JM, and Egbueri JC. Editorial: Chemometric approach to distribution, source apportionment, ecological and health risk of trace pollutants. Front Environ Sci. (2022) 10:1107465/BIBTEX. doi: 10.3389/FENVS.2022.1107465/BIBTEX

28. Hakanson L. An ecological risk index for aquatic pollution control.a sedimentological approach. Water Res. (1980) 14:975–1001. doi: 10.1016/0043-1354(80)90143-8

29. Brenko T, Ružičić S, Radonić N, Puljko M, and Cvetković M. Geochemical factors as a tool for distinguishing geogenic from anthropogenic sources of potentially toxic elements in the soil. Land (Basel). (2024) 13:434. doi: 10.3390/LAND13040434/S1

30. Zhang J, Yang R, Li YC, Peng Y, Wen X, and Ni X. Distribution, accumulation, and potential risks of heavy metals in soil and tea leaves from geologically different plantations. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. (2020) 195:110475. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2020.110475

31. Acosta JA, Faz A, and Martinez-Martinez S. Identification of heavy metal sources by multivariable analysis in a typical Mediterranean city (SE Spain). Environ Monit Assess. (2010) 169:519–30. doi: 10.1007/S10661-009-1194-0

32. Akoto R and Anning AK. Heavy metal enrichment and potential ecological risks from different solid mine wastes at a mine site in Ghana. Environ Adv. (2021) 3:100028. doi: 10.1016/J.ENVADV.2020.100028

33. Luo H, Wang Q, Guan Q, Ma Y, Ni F, Yang E, et al. Heavy metal pollution levels, source apportionment and risk assessment in dust storms in key cities in Northwest China. J Hazard Mater. (2022) 422:126878. doi: 10.1016/J.JHAZMAT.2021.126878

34. Cai LM, Quan K, Wen HH, Luo J, Wang S, Chen LG, et al. A comprehensive approach for quantifying source-specific ecological and health risks of potentially toxic elements in agricultural soil. Environ Res. (2024) 263:120163. doi: 10.1016/J.ENVRES.2024.120163

35. Kubier A, Wilkin RT, and Pichler T. Cadmium in soils and groundwater: A review. Appl Geochemistry. (2019) 108:104388. doi: 10.1016/j.apgeochem.2019.104388

36. El Fadili H, Ben Ali M, Rahman MN, El Mahi M, Lotfi EM, and Louki S. Bioavailability and health risk of pollutants around a controlled landfill in Morocco: Synergistic effects of landfilling and intensive agriculture. Heliyon. (2024) 10:1. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e23729

37. Hiller E, Pilková Z, Filová L, Jurkovič Ľ., Mihaljevič M, and Lacina P. Concentrations of selected trace elements in surface soils near crossroads in the city of Bratislava (the Slovak Republic). Environ Sci pollut Res. (2021) 28:5455–71. doi: 10.1007/S11356-020-10822-Z

38. Sarath KV, Shaji E, and Nandakumar V. Characterization of trace and heavy metal concentration in groundwater: A case study from a tropical river basin of southern India. Chemosphere. (2023) 338:139498. doi: 10.1016/J.CHEMOSPHERE.2023.139498

39. Sharifi A, He B, Feng C, Yang J, Chang C, Beckford HO, et al. Indication of sr isotopes on weathering process of carbonate rocks in karst area of southwest China. Sustainability. (2022) 14:4822. doi: 10.3390/SU14084822

40. Rashed M, Hoque T, Jahangir M, and Hashem M. Manganese as a micronutrient in agriculture: crop requirement and management. J Environ Sci Natural Resour. (2021) 12:225–42. doi: 10.3329/JESNR.V12I1-2.52040

41. Ennaji W, Barakat A, Karaoui I, El Baghdadi M, and Arioua A. Remote sensing approach to assess salt-affected soils in the north-east part of Tadla plain, Morocco. Geology Ecology Landscapes. (2018) 2:22–8. doi: 10.1080/24749508.2018.1438744

42. Oumenskou H, El Baghdadi M, Barakat A, Aquit M, Ennaji W, Karroum LA, et al. Multivariate statistical analysis for spatial evaluation of physicochemical properties of agricultural soils from Beni-Amir irrigated perimeter, Tadla plain, Morocco. Geology Ecology Landscapes. (2019) 3:83–94. doi: 10.1080/24749508.2018.1504272

43. Xie S, Huang L, Su C, Yan J, Chen Z, Li M, et al. Application of clay minerals as adsorbents for removing heavy metals from the environment. Green Smart Min Eng. (2024) 1:249–61. doi: 10.1016/J.GSME.2024.07.002

44. Gasparatos D. Sequestration of heavy metals from soil with Fe-Mn concretions and nodules. Environ Chem Lett. (2013) 11:1–9. doi: 10.1007/S10311-012-0386-Y

45. Hu H, Li X, Gao X, Wang L, Li B, Zhan F, et al. A review on the multifaceted effects of δ-MnO2 on heavy metals, organic matter, and other soil components. RSC Adv. (2024) 14:37752. doi: 10.1039/D4RA06005A

46. Dragovic S and Onjia A. Classification of soil samples according to geographic origin using gamma-ray spectrometry and pattern recognition methods. Appl Radiat Isotopes. (2007) 65:218–24. doi: 10.1016/J.APRADISO.2006.07.005

47. Marković J, Jović M, Smičiklas I, Pezo L, Šljivić-Ivanović M, Onjia A, et al. Chemical speciation of metals in unpolluted soils of different types: Correlation with soil characteristics and an ANN modelling approach. J Geochem Explor. (2016) 165:71–80. doi: 10.1016/J.GEXPLO.2016.03.004

48. Mosley LM, Rengasamy P, and Fitzpatrick R. Soil pH: Techniques, challenges and insights from a global dataset. Eur J Soil Sci. (2024) 75:e70021. doi: 10.1111/EJSS.70021

49. Omoregie AI, Ouahbi T, Basri HF, Ong DEL, Muda K, Ojuri OO, et al. Heavy metal immobilisation with microbial-induced carbonate precipitation: a review. Geotechnical Res. (2024) 11:188–212. doi: 10.1680/JGERE.23.00066

50. Yu H, Li C, Yan J, Ma Y, Zhou X, Yu W, et al. A review on adsorption characteristics and influencing mechanism of heavy metals in farmland soil. RSC Adv. (2023) 13:3505–19. doi: 10.1039/D2RA07095B

51. Wang J, Shi L, Liu J, Deng J, Zou J, Zhang X, et al. Earthworm-mediated nitrification and gut digestive processes facilitate the remobilization of biochar-immobilized heavy metals. Environ pollut. (2023) 322:121219. doi: 10.1016/J.ENVPOL.2023.121219

52. Benlkhoubi N, Saber S, Lebkiri A, Rifi EH, Elfahime E, and Khadmaoui A. Accumulation of heavy metals in irrigated agricultural soils by the waters of hydraulic basin of Sebou in city of Kenitra (Morocco). Int J Innov Appl Stud. (2015) 12:334–41. Available online at: http://www.ijias.issr-journals.org/abstract.php?article=IJIAS-15-074-03 (Accessed November 12, 2025).

53. Sanad H, Moussadek R, Mouhir L, Lhaj MO, Zahidi K, Dakak H, et al. Ecological and human health hazards evaluation of toxic metal contamination in agricultural lands using multi-index and geostatistical techniques across the mnasra area of Morocco’s gharb plain region. J Hazardous Materials Adv. (2025) 18:100724. doi: 10.1016/J.HAZADV.2025.100724

54. Kuklová M, Kukla J, Hniličková H, Hnilička F, and Pivková I. Impact of car traffic on metal accumulation in soils and plants growing close to a motorway (Eastern Slovakia). Toxics. (2022) 10:183. doi: 10.3390/TOXICS10040183

55. Krzebietke S, Daszykowski M, Czarnik-Matusewicz H, Stanimirova I, Pieszczek L, Sienkiewicz S, et al. Monitoring the concentrations of Cd, Cu, Pb, Ni, Cr, Zn, Mn and Fe in cultivated Haplic Luvisol soils using near-infrared reflectance spectroscopy and chemometrics. Talanta. (2023) 251:123749. doi: 10.1016/J.TALANTA.2022.123749

56. Nebil B, Siwar F, Benamar C, Catherine FN, and Michel B. Impacts of irrigation systems on vertical and lateral metals distribution in soils irrigated with treated wastewater: Case study of Elhajeb-Sfax. Agric Water Manag. (2019) 225:105739. doi: 10.1016/J.AGWAT.2019.105739

57. da Gama JT, Loures L, López-Piñeiro A, and Nunes JR. Spatial distribution of available trace metals in four typical mediterranean soils: the caia irrigation perimeter case study. Agronomy. (2021) 11:2024. doi: 10.3390/AGRONOMY11102024

58. Zhou Y, Sherpa S, and McBride MB. Pb and Cd chemisorption by acid mineral soils with variable Mn and organic matter contents. Geoderma. (2020) 368:114274. doi: 10.1016/J.GEODERMA.2020.114274

59. Wang S, Wu J, Jiang J, Masum S, and Xie H. Lead adsorption on loess under high ammonium environment. Environ Sci pollut Res. (2021) 28:4488–502. doi: 10.1007/S11356-020-10777-1

60. Campillo-Cora C, Conde-Cid M, Arias-Estévez M, Fernández-Calviño D, and Alonso-Vega F. Specific adsorption of heavy metals in soils: individual and competitive experiments. Agronomy. (2020) 10:1113. doi: 10.3390/AGRONOMY10081113

61. Tang T, Zhou H, Yang Z, Zeng P, Gu JF, Mu YS, et al. Meta-analysis of the impacts of applying livestock and poultry manure on cadmium accumulation in soil and crops. Agronomy. (2024) 14:2942. doi: 10.3390/AGRONOMY14122942/S1

62. Emurotu JE, Azike EC, Emurotu OM, and Umar YA. Chemical fractionation and mobility of Cd, Mn, Ni, and Pb in farmland soils near a ceramics company. Environ Geochem Health. (2024) 46:1–15. doi: 10.1007/S10653-024-02030-2

63. Guo G, Wu F, Xie F, and Zhang R. Spatial distribution and pollution assessment of heavy metals in urban soils from southwest China. J Environ Sci. (2012) 24:410–8. doi: 10.1016/S1001-0742(11)60762-6

64. Zhao L, Yan Y, Yu R, Hu G, Cheng Y, and Huang H. Source apportionment and health risks of the bioavailable and residual fractions of heavy metals in the park soils in a coastal city of China using a receptor model combined with Pb isotopes. Catena (Amst). (2020) 194:104736. doi: 10.1016/J.CATENA.2020.104736

65. Jiang HH, Cai LM, Hu GC, Wen HH, Luo J, Xu HQ, et al. An integrated exploration on health risk assessment quantification of potentially hazardous elements in soils from the perspective of sources. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. (2021) 208:111489. doi: 10.1016/J.ECOENV.2020.111489

66. Lafuente AL, González C, Quintana JR, Vázquez A, and Romero A. Mobility of heavy metals in poorly developed carbonate soils in the Mediterranean region. Geoderma. (2008) 145:238–44. doi: 10.1016/J.GEODERMA.2008.03.012

67. Missana T, Alonso U, Mayordomo N, and García-Gutiérrez M. Analysis of cadmium retention mechanisms by a smectite clay in the presence of carbonates. Toxics. (2023) 11:130. doi: 10.3390/TOXICS11020130/S1

68. de Godoi Pereira M, Matos TC, Santos MCC, Aragão CA, Leite KRB, da Costa Pinto PA, et al. An interdisciplinary approach to evaluate the mobility and toxicity of cadmium in a soil-plant system. Clean (Weinh). (2018) 46:1800134. doi: 10.1002/CLEN.201800134

69. Filipović L, Romić M, Romić D, Filipović V, and Ondrašek G. Organic matter and salinity modify cadmium soil (phyto)availability. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. (2018) 147:824–31. doi: 10.1016/J.ECOENV.2017.09.041

70. Beesley L, Moreno-Jiménez E, Clemente R, Lepp N, and Dickinson N. Mobility of arsenic, cadmium and zinc in a multi-element contaminated soil profile assessed by in-situ soil pore water sampling, column leaching and sequential extraction. Environ pollut. (2010) 158:155–60. doi: 10.1016/J.ENVPOL.2009.07.021

71. Kang MJ, Yu S, Jeon SW, Jung MC, Kwon YK, Lee PK, et al. Mobility of metal(loid)s in roof dusts and agricultural soils surrounding a Zn smelter: Focused on the impacts of smelter-derived fugitive dusts. Sci Total Environ. (2021) 757:143884. doi: 10.1016/J.SCITOTENV.2020.143884

72. Souissi R, Souissi F, Ghorbel M, Munoz M, and Courjault-Radé P. Mobility of Pb, Zn and Cd in a soil developed on a carbonated bedrock in a semi-arid climate and contaminated by Pb–Zn tailing, Jebel Ressas (NE Tunisia). Environ Earth Sci. (2015) 73:3501–12. doi: 10.1007/S12665-014-3634-6

73. Carrillo-González R, Šimůnek J, Sauvé S, and Adriano D. Mechanisms and pathways of trace element mobility in soils. Adv Agron. (2006) 91:111–78. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2113(06)91003-7

74. Shaheen SM, Tsadilas CD, and Rinklebe J. A review of the distribution coefficients of trace elements in soils: Influence of sorption system, element characteristics, and soil colloidal properties. Adv Colloid Interface Sci. (2013) 201–202:43–56. doi: 10.1016/J.CIS.2013.10.005

75. Bemelmans N, Dejardin R, Arbalestrie B, and Agnan Y. Glyphosate application may influence the transfer of trace elements from soils to both soil solutions and plants. Chemosphere. (2024) 367:143603. doi: 10.1016/J.CHEMOSPHERE.2024.143603

76. Kabata-Pendias A. Trace elements in soils and plants, 4th edition. Boca Raton, FL, USA: CRC Press (2010).

77. Jalali M and Hurseresht Z. Assessment of mobile and potential mobile trace elements extractability in calcareous soils using different extracting agents. Front Environ Sci Eng. (2020) 14:1–17. doi: 10.1007/S11783-019-1186-4/METRICS

78. Burger A and Lichtscheidl I. Strontium in the environment: Review about reactions of plants towards stable and radioactive strontium isotopes. Sci Total Environ. (2019) 653:1458–512. doi: 10.1016/J.SCITOTENV.2018.10.312

79. Yu Y, Alseekh S, Zhu Z, Zhou K, and Fernie AR. Multiomics and biotechnologies for understanding and influencing cadmium accumulation and stress response in plants. Plant Biotechnol J. (2024) 22:2641–59. doi: 10.1111/PBI.14379

80. Patel KS, Pandey PK, Martín-Ramos P, Corns WT, Varol S, Bhattacharya P, et al. A review on arsenic in the environment: bio-accumulation, remediation, and disposal. RSC Adv. (2023) 13:14914–29. doi: 10.1039/D3RA02018E

81. Engel M, Lezama Pacheco JS, Noël V, Boye K, and Fendorf S. Organic compounds alter the preference and rates of heavy metal adsorption on ferrihydrite. Sci Total Environ. (2021) 750:141485. doi: 10.1016/J.SCITOTENV.2020.141485

82. Rambeau CMC, Baize D, Saby N, Matera V, Adatte T, and Föllmi KB. High cadmium concentrations in Jurassic limestone as the cause for elevated cadmium levels in deriving soils: A case study in Lower Burgundy, France. Environ Earth Sci. (2010) 61:1573–85. doi: 10.1007/s12665-010-0471-0

83. Cui W, Li X, Duan W, Xie M, and Dong X. Heavy metal stabilization remediation in polluted soils with stabilizing materials: a review. Environ Geochemistry Health. (2023) 45:4127–63. doi: 10.1007/S10653-023-01522-X

84. Molnár Z, Hegedűs M, Németh P, and Pósfai M. Competitive incorporation of Ca, Sr, and Ba ions into amorphous carbonates. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. (2025) 393:18–30. doi: 10.1016/J.GCA.2025.02.002

85. Fan M, Margenot AJ, Zhang H, Lal R, Wu J, Wu P, et al. Distribution and source identification of potentially toxic elements in agricultural soils through high-resolution sampling☆. Environ pollut. (2020) 263:114527. doi: 10.1016/J.ENVPOL.2020.114527

Keywords: metal contamination, soil typology, vertical distribution, ecological risk assessment, semi-arid agriculture

Citation: Ait Mansour L, Boularbah A and Kebede F (2025) Soil heterogeneity and geogenic-anthropogenic influences on the distribution and ecological risks of potentially toxic elements in semi-arid agricultural soils of north-central Morocco. Front. Soil Sci. 5:1672832. doi: 10.3389/fsoil.2025.1672832

Received: 25 July 2025; Accepted: 24 November 2025; Revised: 15 November 2025;

Published: 11 December 2025.

Edited by:

Seong-Jik Park, Hankyong National University, Republic of KoreaReviewed by:

Antonije Onjia, University of Belgrade, SerbiaRaymond Webrah Kazapoe, University for Development Studies, Ghana

El Hassania El Hamzaoui, Université Sultan Moulay Slimane, Morocco

Copyright © 2025 Ait Mansour, Boularbah and Kebede. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Laila Ait Mansour, bGFpbGEuYWl0bWFuc291ckB1bTZwLm1h

Laila Ait Mansour

Laila Ait Mansour Ali Boularbah

Ali Boularbah Fassil Kebede

Fassil Kebede