- 1Institute of Environment and Sustainable Development in Agriculture, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Beijing, China

- 2Hubei Key Laboratory of Waterlogging Disaster and Agricultural Use of Wetland/Engineering Research Center of Ecology and Agricultural Use of Wetland, Ministry of Education, College of Agriculture, Yangtze University, Jingzhou, China

- 3Lijiang Branch of Yunnan Provincial Tobacco Company, Lijiang, China

- 4Yunnan Academy of Tobacco Agricultural Sciences, Kunming, Yunnan, China

- 5College of Environment, Hunan Agricultural University, Changsha, China

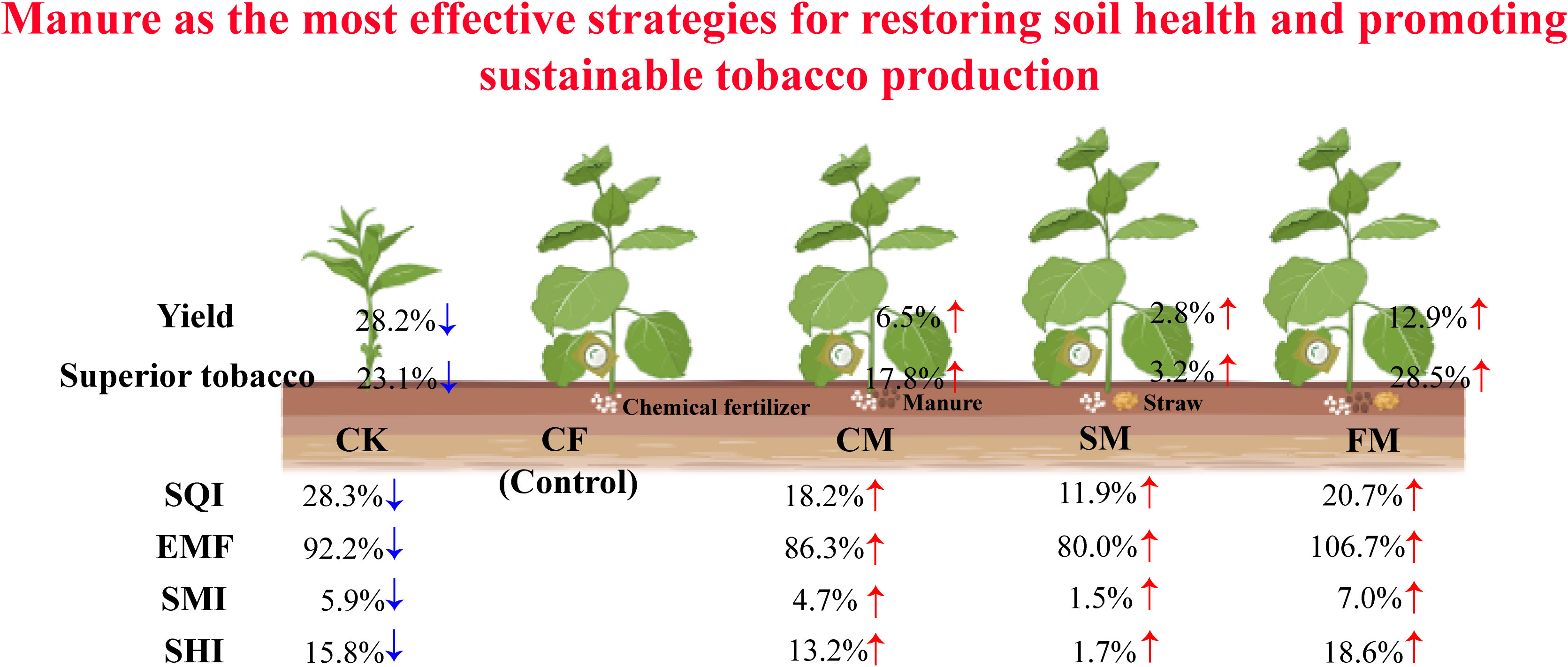

Long-term organic fertilization is widely advocated to counteract soil fertility decline and nutrient imbalances in tobacco cropping systems. However, systematic research comprehensively evaluating the long-term effects of different organic fertilizers on soil physicochemical properties, enzyme activity, microbial diversity, tobacco yield, and quality remains limited. A 7-year field study was conducted to compare the long-term impacts of chemical fertilizer (CF), manure (CM), straw mulching (SM), and farmyard compost of manure and straw (FM) on soil health and tobacco productivity. The soil quality index (SQI) under CM, SM, and FM treatments was 18.2%, 11.9%, and 20.7% higher, respectively, than that of the CF treatment. Similarly, CM, SM, and FM treatments increased soil ecosystem multifunctionality (EMF) by 86.3%, 80.0%, and 106.7%, respectively. CM, SM, and FM treatments increased the microbial diversity index by 4.7%, 1.5%, and 7.0%, respectively. CM, SM, and FM treatments increased soil health index by 13.2%, 1.7%, and 18.6%, respectively, through concurrent improvements in the SQI, EMF, and microbial diversity index. Furthermore, CM, SM, and FM treatments not only increased tobacco yield by 6.5%, 2.8%, and 12.9%, respectively, but also significantly enhanced the proportion of premium-grade leaves by 17.8%, 3.2%, and 28.5%, respectively. Overall, farmyard compost of manure and straw maximized the concurrent gains in soil health and tobacco yield and quality. Consequently, farmyard compost of manure and straw application emerges as the most effective strategy to concurrently maintain soil health and attain high-yield, high-quality tobacco.

Graphical Abstract. CK, no fertilizer; CF, 100% chemical compound fertilizer; CM, manure combined with 90% chemical compound fertilizer; SM, straw combined with 90% chemical compound fertilizer; FM, farmyard compost of manure and straw, and 90% chemical compound fertilizer; SQI, soil quality index; EMF, ecosystem multifunctionality; SMI, soil microbial index; SHI, soil health index. The abstract should ideally be structured according to the IMRaD format (Introduction, Methods, Results and Discussion). Provide a structured abstract if possible. If your article has been copyedited by us, please provide the updated abstract based on this version.

Highlights

● CM, SM and FM increased SQI by 18.2%, 11.9%, and 20.7%, respectively.

● CM, SM and FM increased EMF by 86.3%, 80.0%, and 106.7%, respectively.

● SMI was enhanced by 4.7%, 1.5%, and 7.0% under CM, SM, and FM, respectively.

● CM, SM and FM raised SHI by 13.2%, 1.7% and 18.6% through improvements in SQI, EMF, SMI.

● FM increased tobacco yield by 12.9% and proportion of premium-grade leaves by 28.5%.

1 Introduction

Tobacco, a globally significant economic crop, plays a vital role in tax revenue, employment, agricultural development, and trade, particularly in developing and low-income countries (1, 2). However, conventional cultivation practices are frequently characterized by the excessive application of chemical fertilizers, driven by factors such as the limited availability of fertile land, economic incentives for higher yields, and population growth (3, 4). Long-term reliance on chemical fertilizers can result in soil compaction, reduced fertility, and an increased prevalence of soil-borne diseases, thereby posing a significant threat to the production and quality of tobacco (5, 6). To ensure the long-term sustainability of tobacco production, it is essential to enhance soil fertility and protect soil ecosystem health. Therefore, there is an urgent need for scientific and rational fertilization measures to enhance soil microbial diversity, fertility, enzyme activity, tobacco yield, and quality to achieve a win-win situation between soil health and sustainable production in tobacco cultivation.

Fertilizers, as crucial factors influencing soil ecosystems, are directly linked to physicochemical properties, enzyme activity, and microbial diversity (7, 8). Chemical fertilization rapidly supplies nutrients, thereby accelerating plant growth (9). However, the narrow nutrient spectrum and high ionic strength of chemical fertilizers can negatively impact soil physicochemical properties and disrupt nutrient balance, inhibiting the activity of enzymes and microorganisms (7, 10). To promote soil health and ensure crop yields, organic fertilization is widely adopted in tobacco production to enhance soil fertility and ecosystem stability, thereby supporting sustainable tobacco-field management (3, 10, 11). Mechanistically, organic fertilizers improve soil aggregate structure, thereby increasing aeration and water retention and favoring root proliferation (12). Furthermore, organic fertilizers boost the levels of soil organic carbon (SOC), organic nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, and other nutrients, which are positively associated with tobacco leaf yield and quality (13, 14). However, the specific effects of organic amendments are highly dependent on their type. Studies have indicated that animal-based organic fertilizers (such as livestock manure and poultry) generally enhance soil organic matter content and improve soil structure more effectively than plant-based organic fertilizers (such as green manure and crop residues) (15, 16). By releasing readily available nutrients, organic fertilizers create favorable conditions for both extracellular enzymes and soil microorganisms (7, 17). Indeed, organic matter inputs markedly enhance the activities of invertase, catalase, cellulase, and protease, thereby accelerating organic matter decomposition and nutrient cycling, and ultimately improving soil fertility (18, 19). This enhanced nutrient availability and improved soil fertility further stimulated microbial reproduction and metabolic activity. Numerous studies have reported that long-term organic fertilization significantly increases the abundance and diversity of both fungal and bacterial communities, which are fundamental agents for nutrient biogeochemical cycling and plant growth (3, 20, 21). Consequently, sustained organic amendment not only boosts microbial functionality but also fundamentally improves the integrated concept of soil health (22, 23). Moreover, improvements in soil physicochemical properties, enzyme activity, and microbial diversity are pivotal determinants of soil health (23). Nevertheless, long-term field experiments that systematically compare the effects of different organic fertilizer types on soil physicochemical properties, microbial diversity, enzyme activities, leaf yield, and quality remain limited.

A seven-year field experiment was performed in China’s major tobacco growing regions to quantify how contrasting organic fertilizer regimes modulate soil enzyme activities, physicochemical properties, and microbial diversity, and how these changes translate into soil health, tobacco yield, and quality. The objectives of this study were as follows: 1) to evaluate the temporal dynamics of soil physicochemical properties, enzyme activities, and microbial diversity under the long-term application of different organic fertilizers and assess their cascading impacts on soil health, and 2) to quantify the long-term influences of these organic fertilizers on the yield and quality of tobacco leaves. This study aims to develop optimized fertilizer management strategies that simultaneously boost tobacco yield and quality while improving soil health through enhanced microbial diversity and nutrient cycling in tobacco fields.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Experimental design

A continuous 7-year (2018–2024) study was conducted in Lijiang, Yunnan Province, China (99°50′E, 27°7′N). The region is characterized by a subtropical humid climate, with an annual precipitation of 975 mm and an average annual temperature of 16.3°C. The region exhibits pronounced seasonal variability, marked by warm and humid summers and mild and relatively dry winters, a pattern driven by the prevailing subtropical monsoon circulation. The physicochemical properties of the yellow-brown soil at 0 cm–20 cm were determined as follows: pH 6.13, soil organic carbon 15.16 g kg−¹, total nitrogen 0.12 g kg−¹, hydrolyzable nitrogen 107.1 mg kg−¹, total phosphorus 113.6 mg kg−¹, total potassium 1.56 g kg−¹, available phosphorus 69.1 mg kg−¹, and available potassium 139.2 mg kg−¹.

The experiment was designed with five fertilizer treatments: CK (no fertilizer for seven years), CF (100% chemical compound fertilizer for seven years), CM (manure combined with 90% chemical compound fertilizer for seven years), SM (straw combined with 90% chemical compound fertilizer for seven years), and FM (farmyard compost of manure and straw and 90% chemical compound fertilizer for seven years). Each treatment consisted of three replicate plots, each covering 50 m² (5 m × 10 m). The application rates for fertilizers were as follows: chemical compound fertilizer (N:P2O5:K2O = 15:15:15) at 600 kg ha−¹, manure (derived from cow manure) at 0.2 kg plant−¹, and farmyard compost of manure and straw at 0.5 kg plant−¹. For SM treatment, the previous season’s rapeseed crop residues were retained as full-coverage mulch. The manure contained 45% organic matter and ≥5% total nutrients (N +P2O5 + K2O), the straw contained 72% organic matter and ≥4% total nutrients, and the farmyard compost of manure and straw contained 30% organic matter and ≥5% total nutrients. All organic fertilizers were applied in a single basal application, whereas the chemical compound fertilizer was split and applied in a 3:3:2:2 ratio across the basal, seedling recovery, root establishment, and rapid growth stages. Tobacco (cv. Yunyan87) is cultivated annually in this region from May to September, and the transplant spacing is maintained at 1.2 m×1.0 m. Rapeseed (cv. Yunyou Hybrid Rapeseed No. 2) followed from October to April of the next year, receiving 600 kg ha−¹ of chemical compound fertilizer (N:P2O5:K2O = 20:11:10). All field management practices, including fertilization, transplanting, and pest control, were consistently maintained and aligned with high-yield cultivation protocols throughout the growing season.

2.2 Soil samples collection and physicochemical properties analysis

Soil samples were randomly collected in September 2024, with five replicates taken from each plot at a depth of 0 cm–20 cm. Following sample collection, the soil was processed to remove extraneous materials, including residual roots, plant stems, leaves, and small stones. Subsequently, each sample was divided into three parts for further analyses. The first part was air-dried at room temperature and subsequently sieved through a 100-mesh sieve to analyze the base soil physicochemical properties. The second part was stored at 4°C for enzymatic activity analysis, and the third part was immediately stored at −80°C for subsequent microbial community composition and diversity analysis.

The soil physicochemical properties were determined using standardized analytical methods (24). Soil pH was measured using a digital pH meter (Leici PHS-25, China). Hydrolyzable nitrogen (HN) was quantified using the alkaline hydrolysis diffusion method, and available phosphorus (AP) was determined using the sodium bicarbonate extraction-molybdenum antimony colorimetric method. The available potassium (AK) and total potassium (TK) concentrations were analyzed using flame photometry. Total nitrogen (TN) content was measured using the semi-micro Kjeldahl method, and total phosphorus (TP) was assessed using the digestion-molybdenum-antimony spectrophotometric technique. Soil organic carbon (SOC) was measured using potassium dichromate oxidation-spectrophotometry.

2.3 Soil enzyme activity analysis

Soil enzyme activity was evaluated using the methodologies described in “Soil Enzyme and Their Research” (25). Acid phosphatase activity was assayed by monitoring p-nitrophenol release at 410 nm (PNPP method), while urease activity was quantified via NH3-N production using indophenol blue at 578 nm. Catalase activity was measured by H2O2 decomposition at 240 nm, and amylase activity was measured through starch hydrolysis at 540 nm. Protease activity was determined using the Folin–Ciocalteu method at 750 nm, whereas nitrate and nitrite reductases were analyzed using Griess reagent at 540 nm. Dehydrogenase activity was assessed via TTC reduction at 485 nm, and cellulase activity was assessed via CMC hydrolysis at 540 nm after a 3-day incubation period. α-1,4-glucosidase, β-1,4-glucanase, and sucrase activities were measured using the DNS method at 540 nm. Hydroxylamine reductase was analyzed using Nessler’s reagent at 420 nm, and denitrification enzyme activity was quantified via N2O production using gas chromatography. Activities were respectively expressed in: μg pNP g−¹ h−¹ (phosphatase), mg NH3-N g−¹ d−¹ (urease), mL H2O2 g−¹ 20 min−¹ (catalase), mg glucose g−¹ d−¹ (amylase), μg tyrosine g−¹ d−¹ (protease), mg NO2−-N g−¹ d−¹ (nitrate reductase), mg NO2−-N reduced g−¹ d−¹ (nitrite reductase), mg TPF g−¹ d−¹ (dehydrogenase), mg glucose g−¹ 3d−¹ (cellulase), mg glucose g−¹ d−¹ (glycosidases), μg NH3-N g−¹ d−¹ (hydroxylamine reductase), and mg N2O-N g−¹ 2d−¹ (denitrification).

2.4 Soil microbial community analysis

Total genomic DNA was extracted from 0.3 g of each soil sample (n = 15) using the FastDNA Spin Kit (MP Biomedicals, USA). DNA concentration and purity were assessed using a NanoDrop One/Onec Micro UV–Vis Spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA), and the extracted DNA was stored at −80°C until further analysis. The bacterial community was characterized by amplifying the V3–V4 hypervariable regions of the 16S rRNA gene using the primers 338F (5’-ACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGCAG-3’) and 806R (5’-GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3’). PCR amplification was conducted in triplicate in 20 μL reactions, each containing 10 ng of template DNA, and the products were visualized on 2% agarose gels. For fungal community analysis, the ITS region was amplified using the primers ITS1F (5’-CTTGGTCATTTAGAGGAAGTAA-3’) and ITS2R (5’-GCTGCGTTCTTCATCGATGC-3’). The PCR conditions and quality control steps were consistent with those used for the bacterial analysis. Amplicon libraries were prepared and sequenced on an Illumina NovaSeq platform (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) by Majorbio BioPharm Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Raw sequences were processed using the QIIME2 pipeline, with quality filtering and error correction performed using the DADA2. Operational taxonomic units (OTUs) were clustered at a 97% similarity threshold and taxonomically classified using a Naïve Bayes classifier trained on the Silva138/16S database for bacteria and the UNITE 9.0 database for fungi. Representative OTUs were further validated against the HPB (https://www.cerl.org/resources/hpb/content) and UNITE (https://unite.ut.ee/) databases. Alpha diversity indexes, including Ace, Sobs, Chao, Shannon, Simpson and Coverage, were calculated using Mothur software (https://doi.org/10.3389/fsoil.2025.1698802) to evaluate microbial community richness and diversity.

2.5 Tobacco yield and quality

Following complete plot harvest for yield determination, tobacco leaves from each treatment were graded according to the National Standard for Flue-Cured Tobacco Grading (GB 2635-1992) and the proportions of premium-, medium-, and low-grade leaves were computed for subsequent statistical analysis (26).

2.6 Index calculations

To assess the soil quality index and microbial community characteristics, the soil quality index (SQI) and soil microbial index (SMI) were calculated. Each soil physicochemical parameter and microbial α-diversity was normalized to a standardized score ranging from 0 to 1 using the following equation (Equations 1, 2) (27, 28).

where Si represents the linear score of the i physicochemical parameter or microbial community characteristic, normalized to a range of 0 to 1; Y denotes the measured value of the i parameter or characteristic; and Ymax corresponds to the maximum observed value of the i parameter or characteristic.

where n is the number of physicochemical parameters or microbial community characteristics.

To represent soil ecosystem multifunctionality, z-score normalization can be applied to the activity of each soil enzyme (Equations 3, 4) (27).

where Y represents the measured enzyme activity, meani is the mean activity of enzyme i, and SDi is the standard deviation of enzyme i.

where n is the number of soil enzymatic parameters.

The soil health index (SHI) was determined based on soil physicochemical properties, enzyme activities, and microbial diversity using the Entropy-TOPSIS method (29).

Data normalization (Equation 5):

Where Kij represents the normalized value of the jth index in the ith treatment, Yij is the average value of three replicates for the jth index in the ith treatment, and Ymin and Ymax are the minimum and maximum values of the jth index, respectively.

Entropy value calculation (Equations 6, 7):

Where pij is the proportion of the normalized value for the jth index in the ith treatment, and n is the total number of indices.

Entropy weight calculation (Equation 8):

Decision matrix construction (Equation 9):

Soil health index (SHI) calculation (Equations 10–14):

2.7 Statistical analysis

All data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (n = 3). The influences of different fertilizers on soil physicochemical properties, enzyme activities, and microbial communities were assessed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by least significant difference (LSD) at 0.05 level. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was performed using Canoco 5 (Biometris, Netherlands) to examine the relationships between soil physicochemical properties and enzyme activities. Co-occurrence networks were constructed using R4.4.2 and Gephi 0.9.2 (Gephi Team, France). All graphical representations were generated using Origin 2021 (OriginLab Corporation, USA) and R4.4.2 (Ross Ihaka and Robert Gentleman, New Zealand).

3 Result

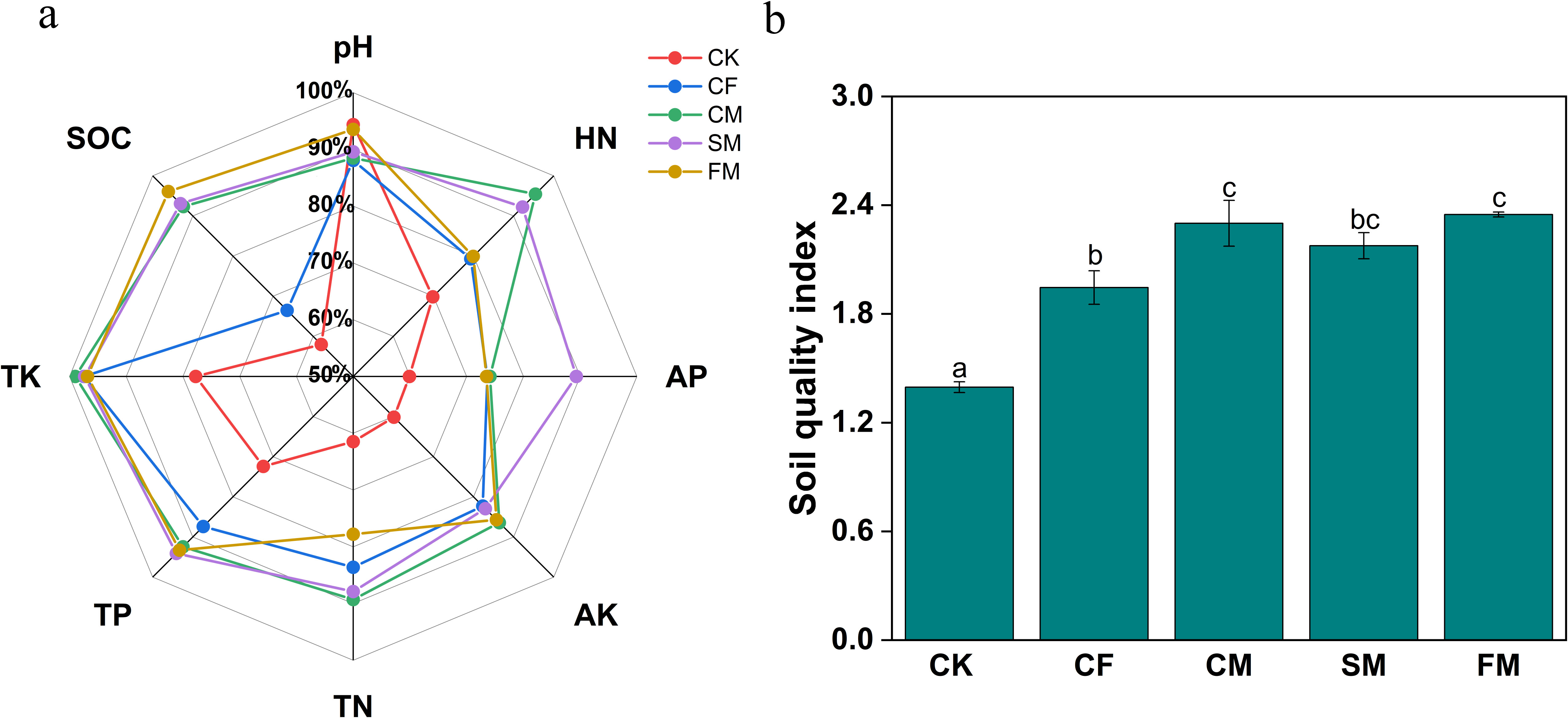

3.1 Soil quality index

Fertilizers significantly increased the soil concentrations of HN, AP, AK, TN, TP, TK, and SOC (p < 0.05; Supporting Information: Supplementary Figure S1). Among all the fertilization treatments, CM and SM treatments exhibited relatively higher soil concentrations of HN, AP, AK, TN, TP, TK, and SOC. Moreover, organic fertilizers significantly increased SOC concentration (p < 0.05). In the tobacco fields, HN, AP, AK, TN, TP, TK, and SOC in fertilizer treatments are 13.6%–36.7%, 22.7%–49.1%, 36.8%–43.7%, 26.5%–45.2%, 20.7%–30.0%, 24.5%–27.3%, and 14.7%–65.7% (Figure 1a). The soil quality index (SQI) for CM, SM, and FM treatments was higher than that of the CF treatment by 18.2%, 11.9%, and 20.7%, respectively. (p < 0.05; Figure 1b). Notably, the increases in the SQI for the CM and SM treatments were statistically significant (p < 0.05). The application of organic fertilizers can enhance the SQI, with manure, straw, and farmyard compost of manure exhibiting higher SQI.

Figure 1. The radar graphs show the relative response of soil chemical properties (a) and soil quality index (b) under different fertilizer practices. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences at the p < 0.05 level.

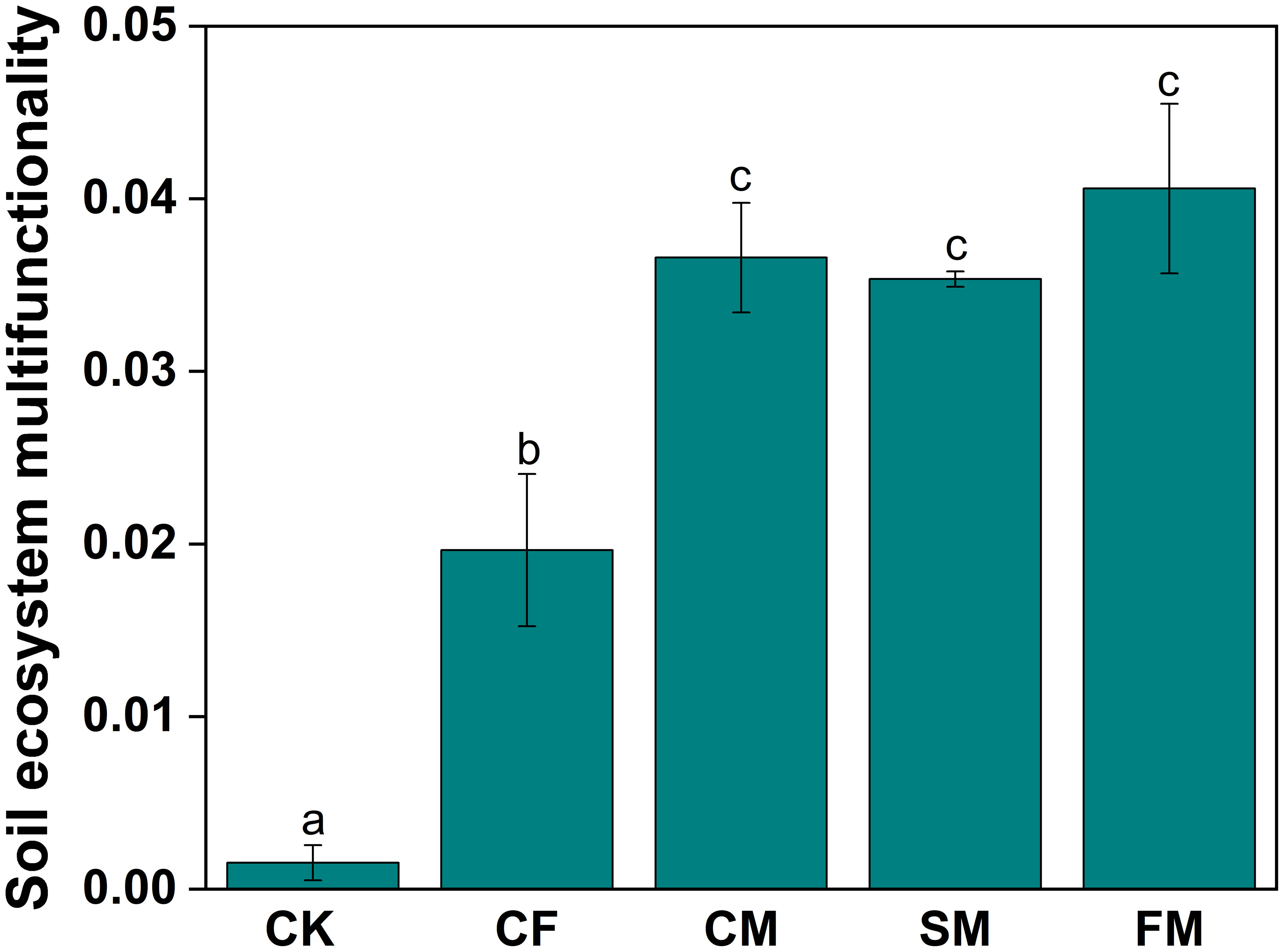

3.2 Soil ecosystem multifunctionality

Compared to the CF treatment, CM and SM treatments enhanced soil urease, catalase, protease, dehydrogenase, cellulase, and α-1,4-glucosidase activities (Supporting Information: Supplementary Figure S2). However, FM treatment reduced the activities of several soil enzymes, including urease, catalase, amylase, nitrate reductase, nitrite reductase, dehydrogenase, β-1,4-glucosidase, α-1,4-glucosidase, and hydroxylamine reductase. Soil ecosystem multifunctionality (EMF) under CF, CM, SM, and FM treatments showed significant increases of 1,183.7%, 2,291.5%, 2,210.5%, and 2,552.9%, respectively, compared to the CK treatment (p < 0.05; Figure 2). Compared to the CF treatment, CM, SM, and FM treatments significantly increased soil EMF by 86.3%, 80.0%, and 106.7%, respectively (p < 0.05). Principal component analysis (PCA) explained 73.8% of the variation in physicochemical properties and enzyme activity (Supporting Information: Supplementary Figure S3). Organic fertilizers can enhance soil EMF, with both manure and farmyard compost of manure and straw exhibiting higher soil ecosystem multifunctionality.

Figure 2. Soil ecosystem multifunctionality under different fertilizer practices. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences at the p < 0.05 level.

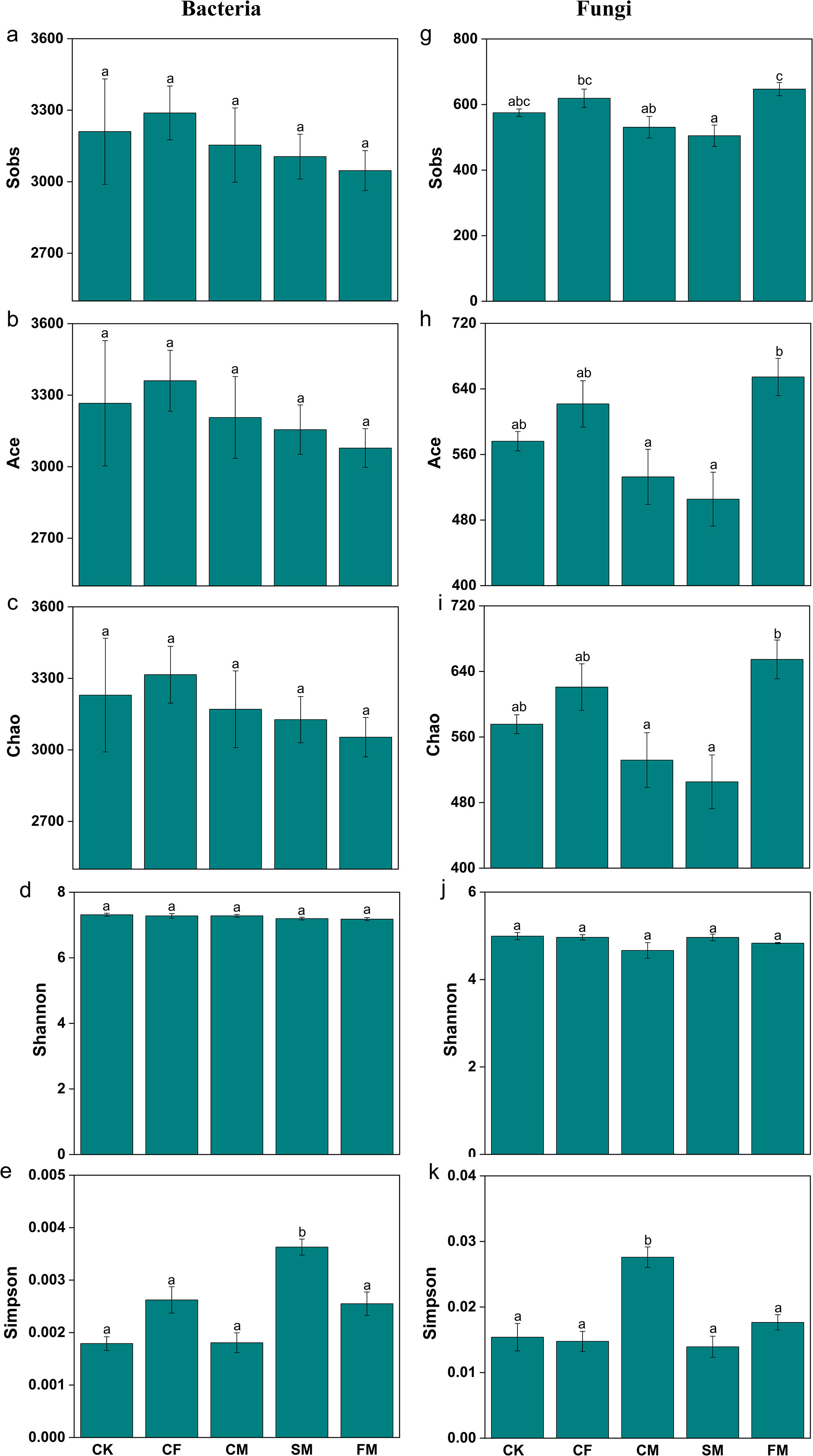

3.3 Soil microbial structure and diversity

Fertilizers resulted in higher values of bacterial diversity and richness indices, such as Shannon, Sobs, ACE, Chao, Simpson, and Coverage (Figure 3). However, no significant differences were observed in the diversity and richness indices of the bacterial communities across all fertilization treatments (p >0.05). In the fungal communities, the CM and FM treatments exhibited higher Sobs, ACE, and Chao richness indices, whereas the CF and SM treatments displayed lower values for these indices. The different types of fertilizers did not significantly affect the diversity (Simpson index) and coverage of soil fungal communities (p >0.05). PCA revealed the effect of different fertilizations on the composition of bacterial and fungal communities at the genus level, with the first two principal components explaining 49.5% and 38.8% of the variance in bacterial and fungal communities, respectively (Supporting Information: Supplementary Figure S4). At the genus level, the analysis of bacterial communities revealed that the most abundant genera in the soil samples were norank_o__Vicinamibacterales (3.6%–8.9%), Rhodococcus (2.3%–5.1%), norank_o__Gaiellales (2.4%–3.7%), Sphingomonas (2.4%–3.7%), and Bacillus (2.2%–3.2%) (Supporting Information: Supplementary Figure S5). In all treatments, the SM and FM treatments exhibited higher relative abundances of the genera norank_o__Vicinamibacterales and Rhodococcus, while showing lower relative abundances of norank_o__Gaiellales, Sphingomonas, and Bacillus. At the genus level, the analysis of fungal communities showed that the most abundant genera in the soil samples were Fusarium (5.3%–14.6%), Mortierella (5.0%–9.5%), Minimedusa (2.5%–5.8%), unclassified_k__Fungi (3.4%–4.2%), and Niesslia and Saitozyma (2.1%–3.4%). Fertilizers enhanced the relative abundance of Fusarium, Minimedusa, and Niesslia in soil. Moreover, CM treatment exhibited a greater relative abundance of Fusarium, Mortierella, Minimedusa, and Niesslia than the other fertilizer treatments.

Figure 3. The α diversity index of bacteria (a–e) and fungi (g–k) at ASV level. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences at the p < 0.05 level.

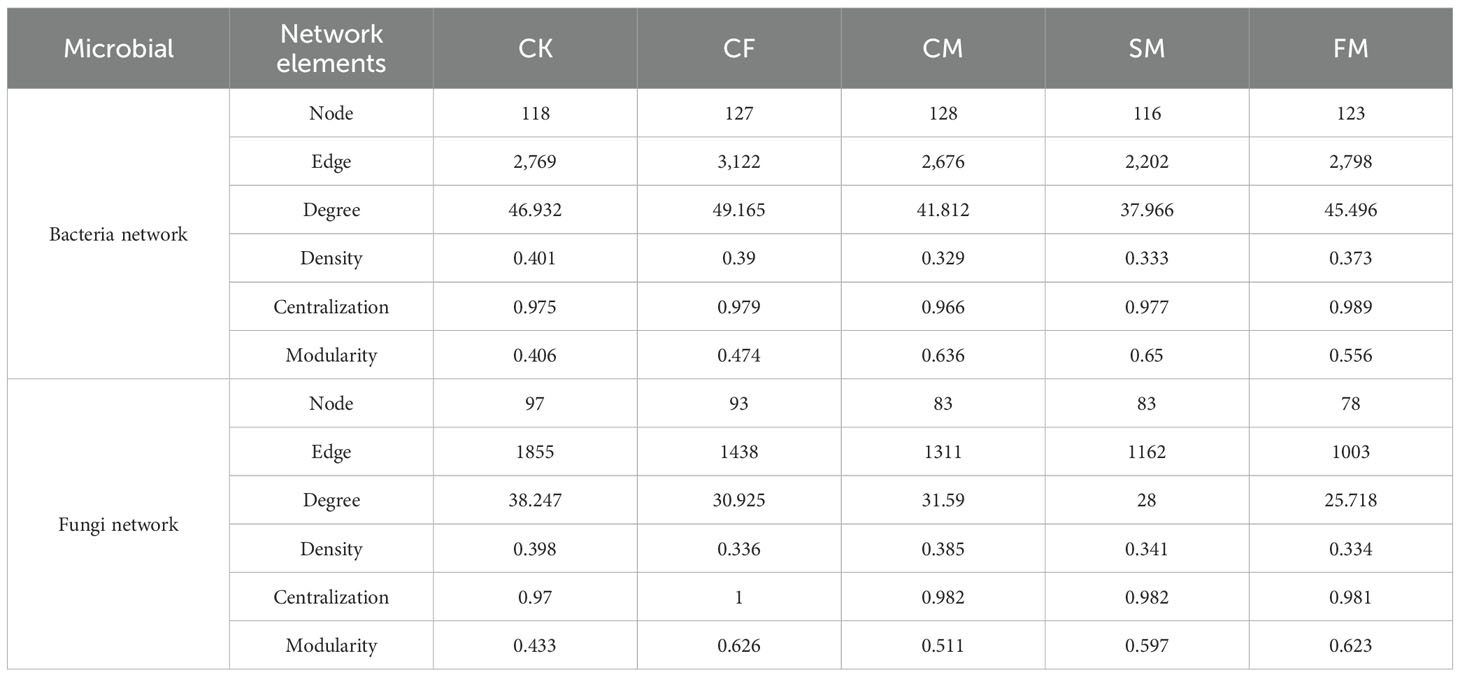

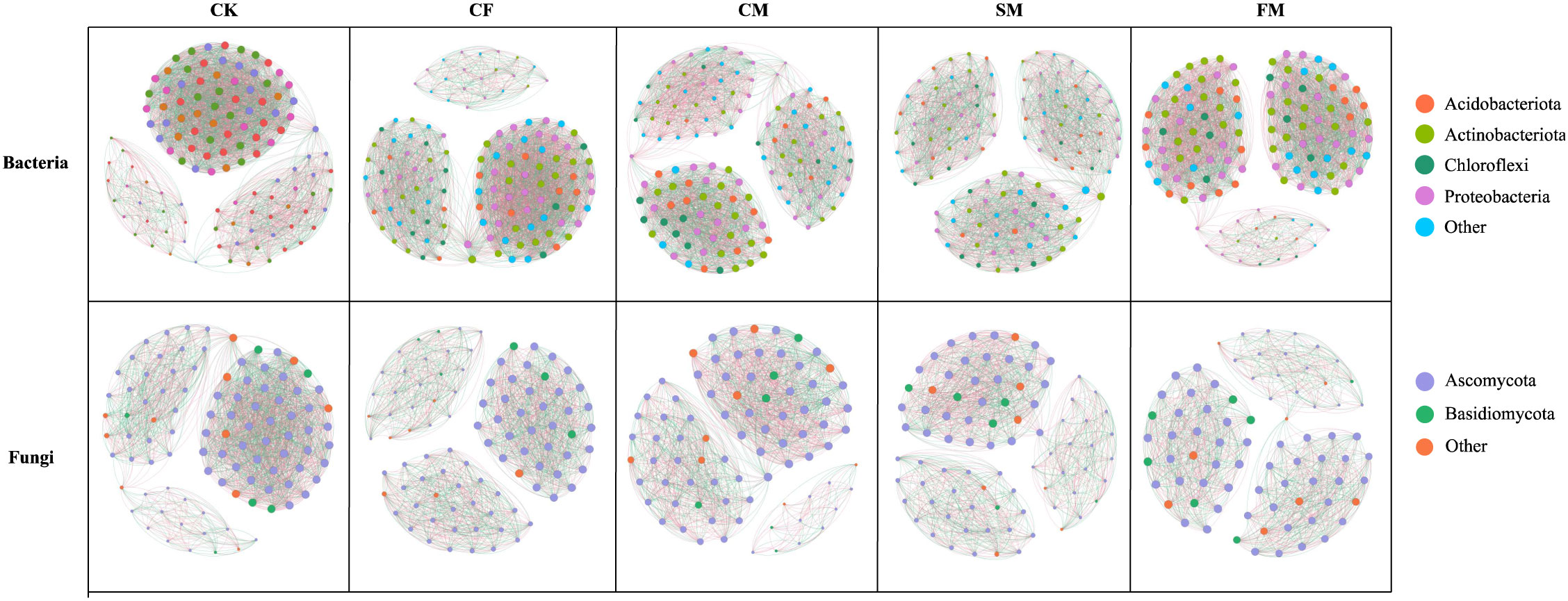

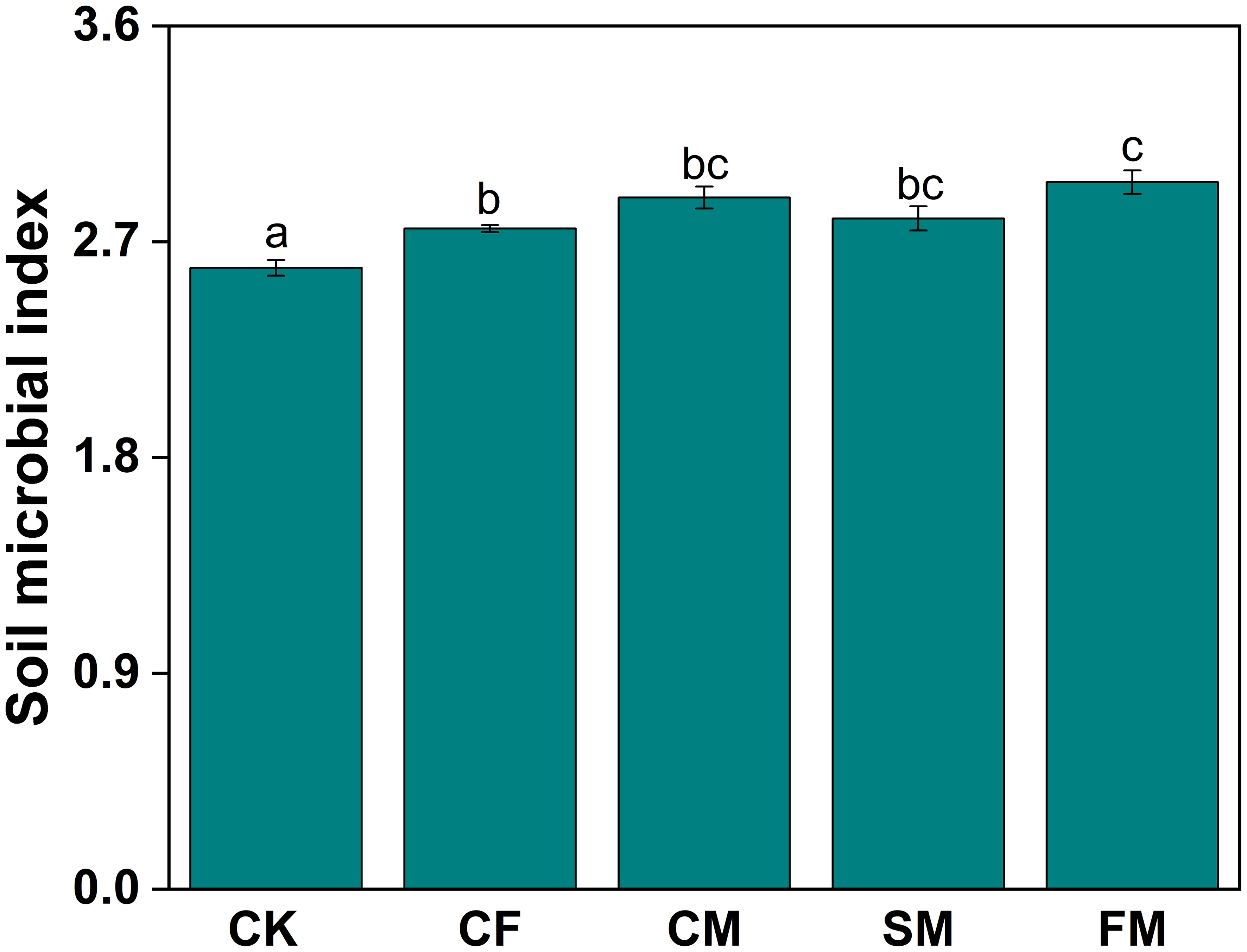

3.4 Soil microbial community stability and soil microbial index

Co-occurrence networks of fungal and bacterial communities were constructed to assess the complexity and stability of soil microbial communities under different organic and inorganic fertilizer treatments (Figure 4). Compared to the CF treatment, CM and SM treatments enhanced the number of connections (edges) within the bacterial community (Table 1). Specifically, the number of nodes in the bacterial network increased by 0.79% under CM treatment compared to that under CF treatment. Additionally, the modularity of the bacterial network increased by 34.2%, 17.3%, and 37.1% under CM, SM, and FM treatments, respectively, compared to that under the CF treatment. In all fertilization treatments, the CM and SM treatments exhibited higher values for nodes, edges, degree, and modularity in the bacterial network. In contrast, the fungal network displayed a different response to the fertilizer application. Compared to the CF treatment, organic fertilizers reduced the number of nodes, edges, and degree in the fungal community. However, within the fertilization treatments, CF and CM showed relatively higher values for nodes, edges, degree, and modularity in the fungal network, suggesting a more structured and interconnected community under these fertilization practices. The CM, SM, and FM treatments increased the soil microbial index by 4.7%, 1.5%, and 7.0%, respectively, compared to the CF treatment (p < 0.05; Figure 5). Organic fertilizers can enhance the soil microbial index, with manure exhibiting the highest soil microbial index.

Figure 4. Co-occurrence networks constructed based on the ASV with average relative abundance of >0.09% in the soil bacterial and fungal communities.

Figure 5. Soil microbial index under different fertilizer practices. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences at the p < 0.05 level.

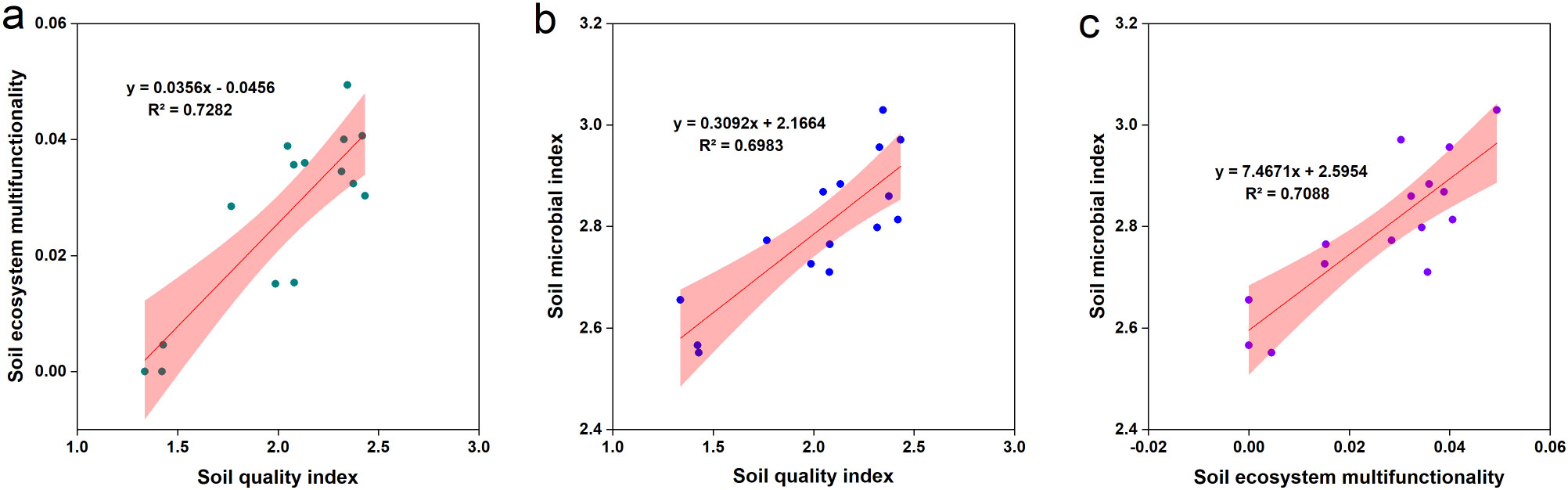

3.5 Soil health index

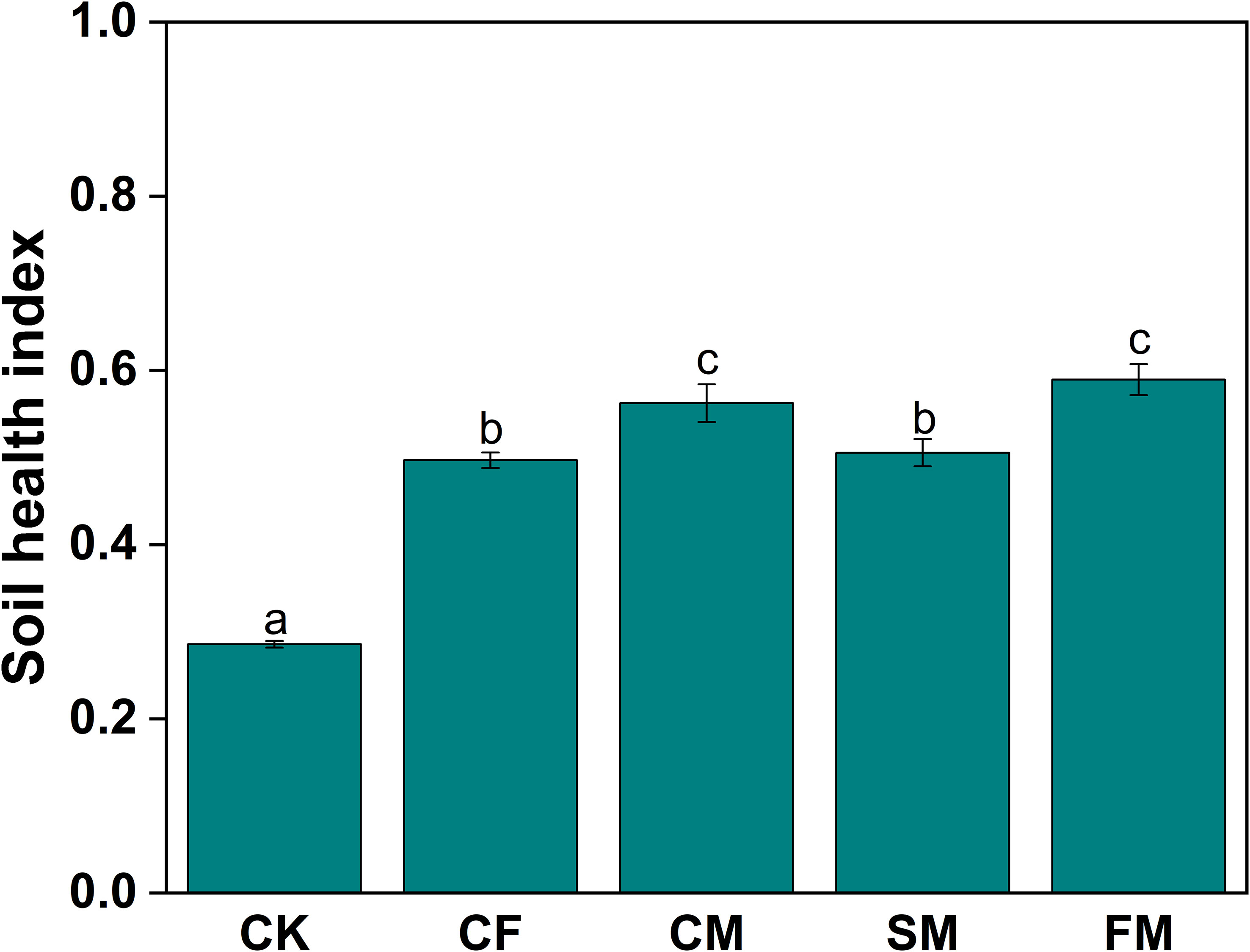

The soil quality index exhibited a positive correlation with soil ecosystem multifunctionality (R2 = 0.728; Figure 6a). Additionally, the soil quality index was positively correlated with the soil microbial index (R2 = 0.698; Figure 6b). Similarly, a positive correlation was observed between soil ecosystem multifunctionality and the soil microbial index (R2 = 0.709; Figure 6c). The application of fertilizers significantly increased the soil health index by 74.0%–106.4% (p < 0.05; Figure 7). Compared to the CF treatment, CM, SM, and FM treatments increased the soil health index by 13.2%, 1.7%, and 18.6%, respectively. CM and FM had the greatest effect on increasing the soil health index. Organic fertilizers can improve the soil health index, with FM achieving the highest soil microbial index of all treatments.

Figure 6. Relationship of soil quality index, soil ecosystem multifunctionality and soil microbial index (a–c) by line regression analysis.

Figure 7. Soil health index under different fertilizer practices. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences at the p < 0.05 level.

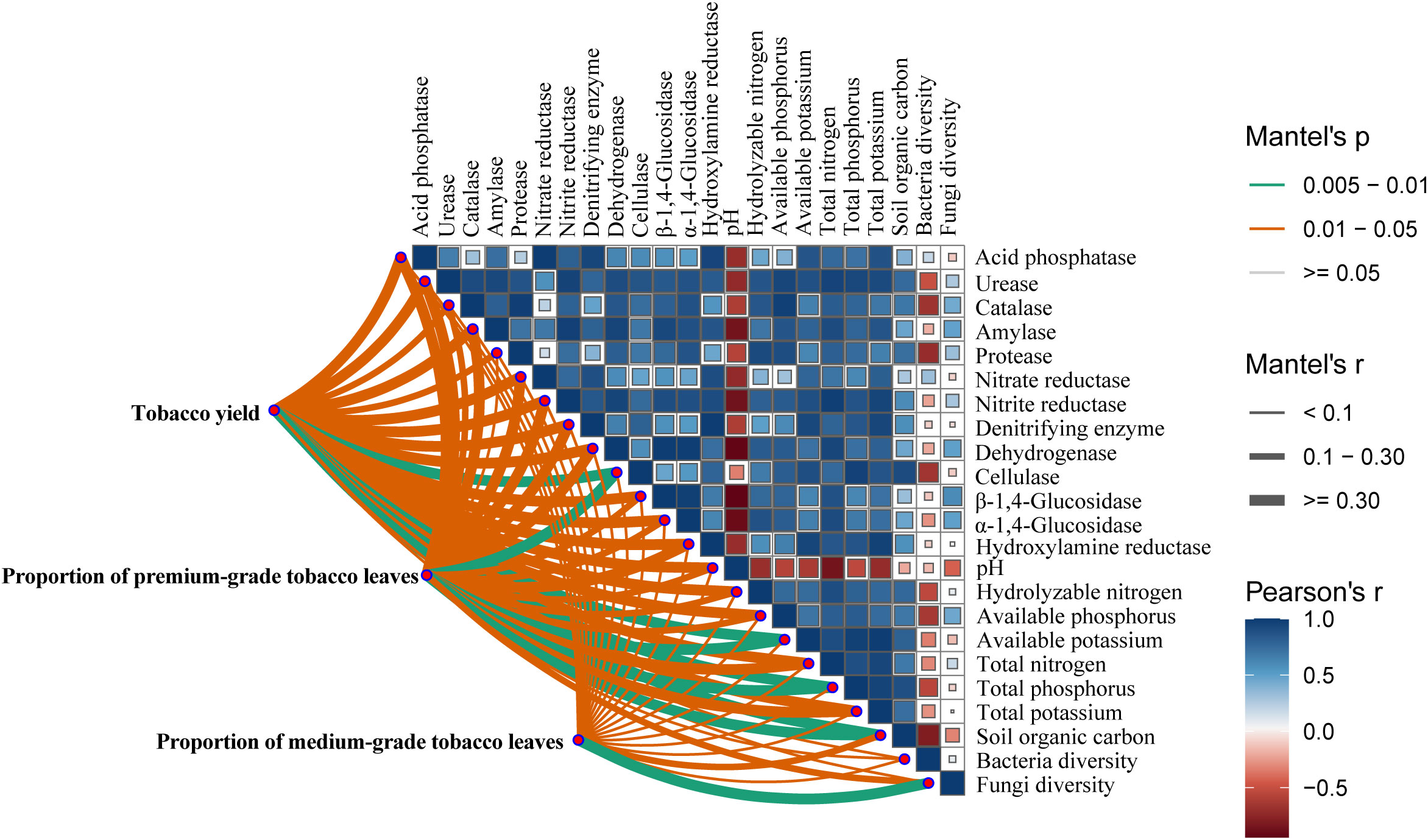

3.6 Relationship between tobacco yield, tobacco quality, soil physicochemical properties, enzyme activity, and microbial diversity

Compared to the CF treatment, manure, straw mulching, and farmyard compost of manure and straw increased tobacco yield by 6.5%, 2.8%, and 12.9%, respectively (Figure 8a). No significant differences were observed between the CF and SM treatments. Compared to the CF treatment, manure, straw mulching, and farmyard compost of manure and straw enhanced the proportion of premium-grade tobacco leaves by 17.8%, 3.2%, and 28.5%, respectively (Figure 8b). Compared to the CF treatment, the proportion of medium-grade tobacco leaves was reduced significantly by 26.9% and 25.3% under the CM and FM treatments, respectively. Meanwhile, FM treatment had the highest net benefit (Supporting Information: Supplementary Table S1). Urease, amylase, cellulase, nitrite reductase, dehydrogenase, β-1,4-glucosidase, α-1,4-glucosidase, pH, total nitrogen, and soil organic carbon significantly influenced tobacco yield (p <0.05; Figure 9). The proportion of premium-grade tobacco leaves was influenced by urease, catalase, dehydrogenase, β-1,4-glucosidase, α-1,4-glucosidase, available phosphorus, and total nitrogen (p <0.05). Overall, the physical, chemical, and biological properties of soil significantly affect on the tobacco yield, and the proportion of premium-grade and medium-grade tobacco leaves.

Figure 8. Tobacco yield (a) and tobacco quality (b) under different fertilizer practices. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences at the p < 0.05 level.

Figure 9. Relationship among soil physicochemical property, soil enzyme activity, microbial community, tobacco yield and quality. Pairwise comparisons of soil properties, enzyme activity and microbial diversity are shown, with a color gradient denoting Spearman’s correlation coefficient. The tobacco yield, superior tobacco proportion and middle tobacco proportion were related to each soil physicochemical property, enzyme activity and microbial diversity by Spearman’s correlation coefficient. Edge width corresponds to r statistic for the correlation, and edge color denotes the statistical significance.

Moreover, xylanolysis exhibited a significant negative correlation with the proportion of premium-grade tobacco leaves (Supporting Information: Supplementary Figure S8). Conversely, the proportion of medium-grade tobacco leaves was significantly positively correlated with xylanolysis, but negatively correlated with nitrate denitrification, nitrite denitrification, nitrous oxide denitrification, nitrate respiration, denitrification, and photoautotrophy. Dung saprotrophs were significantly negatively correlated with rice and proportion of premium-grade tobacco leaves. Soil saprotrophs were significantly positively correlated with the proportion of medium-grade tobacco leaves.

4 Discussion

4.1 Effects of fertilization on soil quality

Generally, fertilizers are known to enhance soil physicochemical properties, particularly the concentrations of TN, mineral nitrogen (ammonium nitrogen: NH4+-N, nitrate nitrogen: NO3−-N), and SOC (30). Chemical fertilizers rapidly increase the concentrations of essential plant available nutrients (N, P, K), thereby boosting soil fertility and facilitating plant production (30). However, the long-term application of chemical nitrogen (N) fertilizers not only induces soil acidification and imbalance in nutrient, but also compromises soil aggregate stability and accelerate the SOC mineralization (10, 31, 32). This study also revealed that seven consecutive years of chemical fertilization in tobacco fields led to a marked decline in soil fertility, with the most pronounced reduction observed in SOC content. Given SOC’s fundamental role in maintaining soil health and ecosystem function, this degradation threatens the soil-plant system’s sustainability (33). The long-term application of organic fertilizers not only increases the concentrations of K, N, and P in the soil but also markedly promotes the accumulation of SOC (34). Organic fertilizers are known for their excellent buffering capacity, which contributes to the stabilization of soil pH and enhances its overall chemical properties (35, 36). Moreover, the efficacy of organic amendments is notably type-dependent (37). Research indicates that straw, manure, and farmyard compost of manure and straw greatly enhanced the concentrations of SOC, dissolved organic carbon (DOC), TN, NO3–N, soil organic nitrogen (SON), dissolved organic nitrogen (DON), AP, and AK, with a more pronounced effect observed in farmyard compost of manure and straw (38). Compost, characterized by a stabilized matrix of nutrients and a rich diversity of microorganisms, facilitates the enhancement of soil physical and chemical properties in a more uniform and durable manner (39). Given the high carbon content and resultant elevated C/N ratio of straw, its decomposition rate is slowed as microorganisms must immobilize more external nitrogen to satisfy their growth and metabolic requirements (40). The combination of manure and straw ensures both prompt nutrient supply and mitigation of microbial performance constraints associated with extreme C/N imbalances, leading to equilibrium and continuous nutrient cycling favorable for plant absorption (41). The combined application of manure and straw is more conducive to the formation of macroaggregates, which consequently reduces the microbial decomposition of SOC (42). With the enhancement of soil physical and chemical properties, the soil quality index under the application of manure, farmyard compost of manure and straw, and straw mulching increased by 18.2%, 20.7%, and 11.9%, respectively, compared to chemical fertilizer.

4.2 Effects of fertilization on ecosystem multifunctionality

Fertilization not only improves soil nutrient availability but also provides substrates for microbial metabolism, which, in turn, stimulates the synthesis and activity of soil enzymes (35, 43). Compared to no fertilization, the fertilization treatments markedly increased the activity of acid phosphatase, urease, catalase, amylase, protease, nitrate reductase, nitrite reductase, denitrifying enzyme, dehydrogenase, cellulase, β-1,4-glucosidase, α-1,4-glucosidase, and hydroxylamine reductase in tobacco fields (p < 0.05). Moreover, chemical and organic fertilizers have different effects on soil enzyme activity (44). In the short term, chemical fertilizers significantly enhance urease, sucrase, and phosphatase activities by rapidly elevating soil nutrient availability (45). In contrast, long-term application of chemical fertilizers may lead to a decline in soil organic matter, pH, and microbial activity, which subsequently reduces overall soil enzyme activity (46). Organic fertilizers can improve soil aggregate structure and fertility and increase soil aeration and water retention capacity, thereby creating favorable conditions for soil enzyme activity (47). The increase in soil enzyme activity further accelerates the decomposition and mineralization of soil organic matter, thereby facilitating the recycling of soil fertility and enhancing enzymatic activity (48). Additionally, different types of organic fertilizers supply diverse nutrient compositions that can markedly influence the production and activity of specific soil enzymes (18, 19). A previous study demonstrated that livestock and poultry manure can significantly enhance the activity of C and N cycling enzymes in the soil (49). Simultaneously, green manure has also been found to significantly enhance soil enzyme activity, particularly exhibiting increased activity in N cycling processes (18). In this study, manure, straw, and farmyard compost containing manure and straw enhanced soil enzyme activities. Notably, farmyard compost containing manure and straw was the most effective in promoting soil enzyme activity. Farmyard compost made from manure and straw demonstrated the most superior efficacy in enhancing soil fertility, supplying ample nutrients to support soil enzyme activities (50). This study also found that the soil quality index was positively correlated with soil ecosystem multifunctionality. In contrast, the application of organic fertilizers improves the proportion of large soil aggregates, thereby increasing soil oxygen content and fostering an optimal environment for soil enzyme activity (51). Organic fertilization plays a vital role in maintaining ecosystem multifunctionality by boosting enzyme activity (52). Organic fertilizers markedly enhanced soil ecosystem multifunctionality by increasing soil enzyme activities, with farmyard compost of manure and straw demonstrating the greatest effectiveness.

4.3 Effects of fertilization on microbial community diversity

Fertilization not only influences soil enzyme activity but also alters the structure and diversity of microbial communities within the soil (53). Chemical and organic fertilizers typically influence the structure of microbial communities by regulating soil physicochemical properties and enzyme activities (54). Long-term use of chemical fertilizers can lead to an imbalance in nutrient availability, a reduction in soil pH, and decreased specific enzyme activity, resulting in a decline in microbial diversity (55). Moreover, the reduction in soil enzymatic activity disrupts critical nutrient cycling processes and diminishes the bioavailability of essential elements, thereby driving a progressive decline in microbial diversity through feedback mechanisms (47). Long-term use of chemical fertilizers has been shown to degrade soil quality and decrease enzyme activity, subsequently leading to a reduction in the diversity of soil fungal and bacterial communities. Moreover, our study found that long-term organic fertilization (manure and straw mulching) led to a decrease in bacterial and fungal richness indices (Sobs, Chao, and Ace). This phenomenon is linked to continuous nutrient inputs and the introduction of exogenous microbial species through agricultural amendments, such as straw, manure, and farmyard compost of manure and straw, which facilitate the growth and proliferation of specific microorganisms (56). The decline in microbial diversity and stability may also be attributed to the excessive proliferation of certain microorganisms, which can be triggered by environmental filtering and competitive interactions (56). However, straw application resulted in a more pronounced decline in fungal and bacterial community diversity. This phenomenon may be attributed to the relatively high C/N ratio of straw, which requires substantial N consumption during decomposition (57). Consequently, N limitation can inhibit the reproduction of bacteria and fungi, ultimately leading to a decrease in the diversity of these microbial communities (58). However, farmyard compost of manure and straw significantly enhanced soil fungal diversity. Farmyard compost of manure and straw is characterized by a rich and balanced nutrient composition, which enhances the physicochemical properties, increases enzyme activities, and improves the soil microenvironment (59). This improvement creates a more conducive environment for fungal growth, ultimately leading to improved fungal diversity (35). Utilizing the soil microbial index to comprehensively evaluate the abundance and diversity of fungi and bacteria, this study revealed that the application of manure, farmyard compost of manure and straw, and straw resulted in increases of 4.7%, 7.0%, and 1.5%, respectively, compared to chemical fertilizers.

4.4 Effects of fertilization on tobacco yield and quality

Organic fertilizers enhance soil fertility and accelerate nutrient turnover by stimulating soil enzyme and microbial activities, leading to increased tobacco leaf yield and improved tobacco quality (5, 6). Manure, straw, and farmyard compost of manure and straw all increased tobacco yield by 6.5%, 2.8%, and 12.9%, respectively. However, the effect of straw on improving tobacco yield and the proportion of premium-grade tobacco was not significant. During decomposition, straw exhibits a relatively high C/N ratio, which leads to significant nitrogen immobilization (62). This immobilization can reduce nitrogen availability in the soil, thereby negatively impacting tobacco growth (63). In dryland regions, the decomposition rate of straw is markedly constrained by soil moisture limitations, which in turn delays the mineralization of essential nutrients and restricts their timely availability for optimal tobacco growth (64). In contrast, manure and farmyard compost of manure and straw are rich in both carbon and nitrogen sources, thereby supplying essential nutrients to promote tobacco growth (60). This phenomenon can be explained by the ability of farmyard compost and manure to enhance soil fertility and improve moisture retention, thereby creating more favorable conditions for tobacco growth, particularly in dryland environments (61). Additionally, this study showed that farmyard compost had a better effect on improving both the yield and quality of tobacco. This is primarily because farmyard compost can sustainably and synergistically supply water, nutrients, and aeration, thereby creating beneficial conditions for nutrient uptake by the tobacco root system (41, 51). Farmyard manure possesses a moderate C/N ratio, which effectively enhances nutrient cycling and utilization efficiency by stimulating enzyme and microbial activities (65). Concurrently, the synchronous enhancement of microbial communities and enzyme activities drives the formation of large soil aggregates, which significantly attenuates the mineralization potential of SOC (42, 51). These integrated improvements collectively promote a robust tobacco root architecture and elevate leaf yield and quality. Although the fertilizer cost of FM treatment was the highest, it maximized net economic benefits by increasing the yield and quality of tobacco leaves.

4.5 Limitation and implication

Our findings provide a mechanistic roadmap for regenerating soil health and advancing the sustainable intensification of tobacco systems, especially in areas where chronic over-reliance on synthetic fertilizers has induced severe soil degradation and yield stagnation. By rigorously disentangling how contrasting organic fertilizers regulate soil quality, enzyme activity, microbial diversity, and, in turn, tobacco yield and leaf quality, this study identified the most effective organic amendments for restoring degraded soils and unlocking productivity gains. However, its primary limitation is its economic viability for widespread adoption. These conclusions stem from multi-year, single-site trials, the specific soil type and climate of which constrain direct quantitative extrapolation. Crucially, we must address the increased input costs associated with organic fertilization, particularly the costs of FM application and composting. Based on our new cost–benefit analysis, we clarify that despite these rising input costs, the substantial 28.5% increase in premium-grade tobacco revenue is sufficient to offset the added expenses, yielding the highest net economic benefit. To further lower the adoption threshold for smallholder farmers, future studies must focus on optimizing the C/N ratio, simplifying composting protocols, and achieving localized production. Empirical validation through multi-site trials across diverse agro-ecological zones is strongly recommended to confirm the long-term stability and applicability of these benefits.

5 Conclusion

The seven-year field study demonstrated that organic fertilizer application improves soil health and enhances the yield and quality of tobacco leaves by improving the soil quality index, ecosystem multifunctionality, and microbial diversity index. Compared to CF, FM increased the soil quality index by 20.7%, ecosystem multifunctionality by 106.7%, and microbial diversity index by 7.0%. A comprehensive assessment using the TOPSIS model, integrating these parameters, confirmed the efficacy of organic amendments in elevating the soil health index, with farmyard compost of manure and straw achieving the highest soil health index. FM not only enhanced the tobacco yield by 12.9% but also significantly improved the proportion of premium-grade tobacco leaves by 28.5%. In summary, farmyard compost of manure and straw serves as a sustainable agricultural strategy that simultaneously improves soil physicochemical properties, enhances enzyme activities, increases microbial diversity, and ultimately boosts both the yield and quality of tobacco.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Author contributions

WY: Formal analysis, Software, Writing – original draft, Data curation. BH: Writing – review & editing, Software, Data curation. JL: Software, Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis, Data curation. ZW: Writing – review & editing, Software, Data curation. WT: Data curation, Resources, Software, Writing – review & editing. BZ: Writing – review & editing, Software, Data curation, Formal analysis. ZX: Data curation, Software, Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis. XD: Software, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Project administration. BW: Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Project administration, Data curation.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This study was supported by the Science and Technology Project of Yunnan Provincial Company of China National Tobacco Corporation (2023530000241025); Yunnan Daguang Laboratory Science and Technology Project (YNDG202302YY03); National Natural Science Foundation of China (General Program) (32401972,42475204); Special Project for Young Innovation of Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (Y2024QC07).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fsoil.2025.1698802/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Appau A, Drope J, Goma F, Magati P, Labonte R, Makoka D, et al. Explaining why farmers grow tobacco: evidence from Malawi, Kenya, and Zambia. Nicotine Tob Res. (2020) 22:2238–45. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntz173

2. Lencucha R, Vichit-Vadakan N, Patanavanich R, and Ralston R. Addressing tobacco industry influence in tobacco-growing countries. Bull World Health Organ. (2024) 102:58–64. doi: 10.2471/BLT.23.290219

3. Chen D, Wang M, Wang G, Zhou Y, Yang X, Li J, et al. Functional organic fertilizers can alleviate tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum L.) continuous cropping obstacle via ameliorating soil physicochemical properties and bacterial community structure. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. (2022) 10:1023693. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2022.1023693

4. Liu G, Deng L, Wu R, Guo S, Du W, Yang M, et al. Determination of nitrogen and phosphorus fertilisation rates for tobacco based on economic response and nutrient concentrations in local stream water. Agric Ecosyst Environ. (2020) 304:107136. doi: 10.1016/j.agee.2020.107136

5. Song W, Shu A, Liu J, Shi W, Li M, Zhang W, et al. Effects of long-term fertilization with different substitution ratios of organic fertilizer on paddy soil. Pedosphere. (2022) 32:637–48. doi: 10.1016/s1002-0160(21)60047-4

6. Zhu R, He S, Ling H, Liang Y, Wei B, Yuan X, et al. Optimizing tobacco quality and yield through the scientific application of organic-inorganic fertilizer in China: a meta-analysis. Front Plant Sci. (2024) 15:1500544. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2024.1500544

7. Shang L, Wan L, Zhou X, Li S, and Li X. Effects of organic fertilizer on soil nutrient status, enzyme activity, and bacterial community diversity in Leymus chinensis steppe in Inner Mongolia, China. PloS One. (2020) 15:e0240559. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0240559

8. Ying D, Chen X, Hou J, Zhao F, and Li P. Soil properties and microbial functional attributes drive the response of soil multifunctionality to long-term fertilization management. Appl Soil Ecol. (2023) 192:105095. doi: 10.1016/j.apsoil.2023.105095

9. Abebe TG, Tamtam MR, Abebe AA, Abtemariam KA, Shigut TG, Dejen YA, et al. Growing use and impacts of chemical fertilizers and assessing alternative organic fertilizer sources in Ethiopia. Appl Environ Soil Sci. (2022) 2022:1–14. doi: 10.1155/2022/4738416

10. Wu L, Jiang Y, Zhao F, He X, Liu H, and Yu K. Increased organic fertilizer application and reduced chemical fertilizer application affect the soil properties and bacterial communities of grape rhizosphere soil. Sci Rep. (2020) 10:9568. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-66648-9

11. Shen Y, Ren T, Mahari WAW, Feng H, Xu C, Fei Y, et al. Soil carbon supplementation: Improvement of root-surrounding soil bacterial communities, sugar and starch content in tobacco (N. tabacum). Sci Total Environ. (2021) 802:149835. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.149835

12. Liu Y, Lan X, Hou H, Ji J, Liu X, and Lv Z. Multifaceted ability of organic fertilizers to improve crop productivity and abiotic stress tolerance: review and perspectives. Agronomy. (2024) 14:1141. doi: 10.3390/agronomy14061141

13. Li S, Li J, Zhang B, Li D, Li G, and Li Y. Effect of different organic fertilizers application on growth and environmental risk of nitrate under a vegetable field. Sci Rep. (2017) 7:17020. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-17219-y

14. Zhai Z, Hu Q, Chen J, Liu C, Guo S, Huang S, et al. Effects of combined application of organic fertilizer and microbial agents on tobacco soil and tobacco agronomic traits. IOP Conf Series: Earth Environ Sci. (2020) 594:12023. doi: 10.1088/1755-1315/594/1/012023

15. Su Y, Zi H, Wei X, Hu B, Deng X, Chen Y, et al. Application of manure rather than plant-origin organic fertilizers alters the fungal community in continuous cropping tobacco soil. Front Microbiol. (2022) 13:818956. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.818956

16. Wang B, Deng X, Wang R, Zongguo X, Tong W, Ma E, et al. Bio-organic substitution in tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum L) cultivation: Optimum strategy to lower carbon footprint and boost net ecosystem economic benefit. J Environ Manage. (2024) 370:122654. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2024.122654

17. Wang C, Ning P, Li J, Wei X, Ge T, Cui Y, et al. Responses of soil microbial community composition and enzyme activities to long-term organic amendments in a continuous tobacco cropping system. Appl Soil Ecol. (2022) 169:104210. doi: 10.1016/j.apsoil.2021.104210

18. Jiang Y, Zhang R, Zhang C, Su J, Cong W, and Deng X. Long-term organic fertilizer additions elevate soil extracellular enzyme activities and tobacco quality in a tobacco-maize rotation. Front Plant Sci. (2022) 13:973639. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2022.973639

19. Wang N and Li F. Influence of long-term inorganic fertilization and straw incorporation influence on soil organic carbon (SOC) by altering C acquisition enzyme activity, active SOC fraction, soil aggregates, and microbial compositional and functional traits. Agric Ecosyst Environ. (2025) 392:109758. doi: 10.1016/j.agee.2025.109758

20. Raza W, Mei X, Wei Z, Ling N, Yuan J, Wang J, et al. Profiling of soil volatile organic compounds after long-term application of inorganic, organic and organic-inorganic mixed fertilizers and their effect on plant growth. Sci Total Environ. (2017) 607-608:326–38. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.07.023

21. Ruan Y, Tang Z, Xia T, and Chen Z. Application progress of microbial fertilizers in flue-cured tobacco production in China. IOP Conf Series: Earth Environ Sci. (2020) 615:12084. doi: 10.1088/1755-1315/615/1/012084

22. Sedlář O, Balík J, Černý J, Kulhánek M, and Smatanová M. Long-term application of organic fertilizers in relation to soil organic matter quality. Agronomy. (2023) 13:175. doi: 10.3390/agronomy13010175

23. Wang H, Xu J, Liu X, Zhang D, Li L, Li W, et al. Effects of long-term application of organic fertilizer on improving organic matter content and retarding acidity in red soil from China. Soil Tillage Res. (2019) 195:104382. doi: 10.1016/j.still.2019.104382

25. Geng Y and Wang D. Methods and applications of soil enzyme assays. Beijing: Sci Press. (2020) 3–36.

26. People’s Republic of China. Flue-cured tobacco. GB 2635-1992. Beijing: Standards Press of China (1992).

27. Liu Q, Yao W, Zhou J, Peixoto L, Qi Z, Mganga KZ, et al. Winter green manure cultivation benefits soil quality and ecosystem multifunctionality under upland paddy rotations in tropics. Plant Soil. (2025) 511:395–407. doi: 10.1007/s11104-024-06991-2

28. Vasu D, Tiwary P, and Chandran P. A novel and comprehensive soil quality index integrating soil morphological, physical, chemical, and biological properties. Soil Tillage Res. (2024) 244:106246. doi: 10.1016/j.still.2024.106246

29. Yang X, Xiong J, Du T, Ju X, Gan Y, Li S, et al. Diversifying crop rotation increases food production, reduces net greenhouse gas emissions and improves soil health. Nat Commun. (2024) 15:198. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-44464-9

30. Shen F, Fei L, Tuo Y, Peng Y, Yang Q, Zheng R, et al. Effects of water and fertilizer regulation on soil physicochemical properties, bacterial diversity and community structure of Panax notoginseng. Scientia Hortic. (2024) 326:112777. doi: 10.1016/j.scienta.2023.112777

31. Liu Y, Zhang M, Han X, Li Y, Zhang Y, Huang X, et al. Influence of long-term fertilization on soil aggregates stability and organic carbon occurrence characteristics in karst yellow soil of Southwest China. Front Plant Sci. (2023) 14:1126150. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2023.1126150

32. Ping F, Li J, Chen P, Wei D, Zhang Q, Jia Z, et al. Mitigating soil degradation in continuous cropping banana fields through long-term organic fertilization: Insights from soil acidification, ammonia oxidation, and microbial communities. Ind Crops Prod. (2024) 213:118385. doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2024.118385

33. Uddin MK, Saha BK, Wong VNL, and Patti AF. Organo-mineral fertilizer to sustain soil health and crop yield for reducing environmental impact: A comprehensive review. Eur J Agron. (2025) 162:127433. doi: 10.1016/j.eja.2024.127433

34. Lian J, Wang H, Deng Y, Xu M, Liu S, Zhou B, et al. Impact of long-term application of manure and inorganic fertilizers on common soil bacteria in different soil types. Agri Ecosyst Environ. (2022) 337:108044. doi: 10.1016/j.agee.2022.108044

35. Gao R, Duan Y, Zhang J, Ren Y, Li H, Liu X, et al. Effects of long-term application of organic manure and chemical fertilizer on soil properties and microbial communities in the agro-pastoral ecotone of North China. Front Environ Sci. (2022) 10:993973. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2022.993973

36. Zhang J, Chi F, Dan W, Zhou B, Cai S, Li Y, et al. Impacts of long-term fertilization on the molecular structure of humic acid and organic carbon content in soil aggregates in black soil. Sci Rep. (2019) 9:11908. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-48406-8

37. Li R, Tao R, Ling N, and Chu G. Chemical, organic and bio-fertilizer management practices effect on soil physicochemical property and antagonistic bacteria abundance of a cotton field: Implications for soil biological quality. Soil Till Res. (2017) 167:30–8. doi: 10.1016/j.still.2016.11.001

38. Yang J, Liu B, Ren Y, Liu H, Jia M, Zhao P, et al. Improving soil quality and crop yield of fluvo-aquic soils through long-term organic-inorganic fertilizer combination: Promoting microbial community optimization and nutrient utilization. Environ Technol Innov. (2025) 37:104050. doi: 10.1016/j.eti.2025.104050

39. Ernest B, Eltigani A, Yanda PZ, Hansson A, and Fridahl M. Evaluation of selected organic fertilizers on conditioning soil health of smallholder households in Karagwe, Northwestern Tanzania. Heliyon. (2024) 10:e26059. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e26059

40. Rezgui C, Trinsoutrot-Gattin I, Benoît M, Laval K, and Riah-Anglet Wassila. Linking changes in the soil microbial community to C and N dynamics during crop residue decomposition. J Integr Agric. (2021) 20:3039–59. doi: 10.1016/s2095-3119(20)63567-5

41. Wang Y, Liang B, Bao H, Chen Q, Cao Y, He Y, et al. Potential of crop straw incorporation for replacing chemical fertilizer and reducing nutrient loss in Sichuan Province, China. Environ pollut. (2023) 320:121034. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2023.121034

42. Zhang Z, Nie J, Liang H, Wei C, Wang Y, Liao Y, et al. The effects of co-utilizing green manure and rice straw on soil aggregates and soil carbon stability in a paddy soil in southern China. J Integr Agric. (2022) 22:1529–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jia.2022.09.025

43. Chen J, Ran W, Zhao Y, Zhao Z, and Song Y. Effects of fertilization on soil ecological stoichiometry and fruit quality in Karst pitaya orchard. Sci Rep. (2024) 14:18307. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-68831-8

44. Solangi F, Zhu X, Solangi KA, Iqbal R, Elshikh MS, Alarjani KM, et al. Responses of soil enzymatic activities and microbial biomass phosphorus to improve nutrient accumulation abilities in leguminous species. Sci Rep. (2024) 14:11139. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-61446-z

45. Zhang X, Xu Y, Cao C, and Chen H. Long-term located fertilization causes the differences in root traits, rhizosphere soil biological characteristics and crop yield. Arch Agron Soil Sci. (2021) 69:151–67. doi: 10.1080/03650340.2021.1964018

46. Bharathi MJ, Anbarasu M, Ragu R, and Subramanian E. Assessment of soil microbial diversity and soil enzyme activities under inorganic input sources on maize and rice ecosystems. Saudi J Biol Sci. (2024) 31:103978. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2024.103978

47. Wang J, Fu X, Ghimire R, Sainju UM, Jia Y, and Zhao F. Responses of soil bacterial community and enzyme activity to organic matter components under long-term fertilization on the Loess Plateau of China. App Soil Ecol. (2021) 166:103992. doi: 10.1016/j.apsoil.2021.103992

48. Xiao Q, He B, and Wang S. Effect of the different fertilization treatments application on paddy soil enzyme activities and bacterial community composition. Agronomy. (2023) 13:712. doi: 10.3390/agronomy13030712

49. Reardon CL, Klein AM, Melle C, Hagerty CH, Klarer ER, MaChado S, et al. Enzyme activities distinguish long-term fertilizer effects under different soil storage methods. Appl Soil Ecol. (2022) 177:104518. doi: 10.1016/j.apsoil.2022.104518

50. Park BJ, Lee CG, Yun HJ, Kim YH, Yoon JH, and Kim HS. Combined application of inorganic fertilizer and chicken manure compost increases maize yield through improved soil fertility. Korean J Soil Sci Fert. (2022) 55:563–9. doi: 10.7745/kjssf.2022.55.4.563

51. Liu C, Han X, Lu X, Yan J, Chen X, and Zou W. Response of soil enzymatic activity to pore structure under inversion tillage with organic materials incorporation in a Haplic Chernozem. J Environ Manage. (2024) 370:122421. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2024.122421

52. Hu W, Zhang Y, Rong X, Zhou X, Fei J, Peng J, et al. Biochar and organic fertilizer applications enhance soil functional microbial abundance and agroecosystem multifunctionality. Biochar. (2024) 6:3. doi: 10.1007/s42773-023-00296-w

53. Amadou A, Song A, Tang Z, Li Y, Wang E, Lu Y, et al. The effects of organic and mineral fertilization on soil enzyme activities and bacterial community in the below- and above-ground parts of wheat. Agronomy. (2020) 10:1452. doi: 10.3390/agronomy10101452

54. Xie Y, Yang O, Han S, Se J, Tang S, Ma Q, et al. Crop rotation stage has a greater effect than fertilisation on soil microbiome assembly and enzymatic stoichiometry. Sci Total Environ. (2022) 815:152956. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.152956

55. Kong W, Qiu L, Ishii S, Jia X, Su F, Song Y, et al. Contrasting response of soil microbiomes to long-term fertilization in various highland cropping systems. ISME Commun. (2023) 3:81. doi: 10.1038/s43705-023-00286-w

56. Hei Z, Peng Y, Hao S, Li Y, Yuan X, Zhu T, et al. Full substitution of chemical fertilizer by organic manure decreases soil N2O emissions driven by ammonia oxidizers and gross nitrogen transformations. Glob Change Biol. (2023) 29:7117–30. doi: 10.1111/gcb.16957

57. Bao Q, Shi J, Liu Z, Kan Y, and Bao W. Application of crop straw with different C/N ratio affects CH4 emission and Cd accumulation in rice (Oryza sativa L.) in Cd polluted paddy soils. Clim Smart Agric. (2025) 2:100036. doi: 10.1016/j.csag.2024.100036

58. Kalkhajeh YK, He Z, Yang X, Lu Y, Zhou J, Gao H, et al. Co-application of nitrogen and straw-decomposing microbial inoculant enhanced wheat straw decomposition and rice yield in a paddy soil. J Agric Food Res. (2021) 4:100134. doi: 10.1016/j.jafr.2021.100134

59. Lishan T and Alemu F. Elucidating sole application of farmyard manure and blended NPSB fertilizer effects on soil properties at Bench Shako and West Omo zone, South West Ethiopia. Heliyon. (2024) 10:e22908. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e22908

60. Chen Y, Lv X, Qin Y, Zhang D, Zhang C, Song Z, et al. Effects of different botanical oil meal mixed with cow manure organic fertilizers on soil microbial community and function and tobacco yield and quality. Front Microbiol. (2023) 14:1191059. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2023.1191059

61. Gong J, Zheng Z, Zheng B, Liu Y, Hu R, Gong J, et al. Deep tillage reduces the dependence of tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum L.) on arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and promotes the growth of tobacco in dryland farming. Can J Microbiol. (2022) 68:203–13. doi: 10.1139/cjm-2021-0272

62. Mühlbachová G, Růžek P, Kusá H, Vavera R, and Káš M. Winter wheat straw decomposition under different nitrogen fertilizers. Agriculture. (2021) 11:83. doi: 10.3390/agriculture11020083

63. Zheng J, Zhang J, Gao L, Wang R, Gao J, Dai Y, et al. Effect of straw biochar amendment on tobacco growth, soil properties, and rhizosphere bacterial communities. Sci Rep. (2021) 11:20727. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-00168-y

64. Jiang C, Zu C, Riaz M, Li C, Zhu Q, Xia H, et al. Influences of tobacco straw return with lime on microbial community structure of tobacco-planting soil and tobacco leaf quality. Environ Sci pollut Res. (2024) 31:30959–71. doi: 10.1007/s11356-024-33241-w

Keywords: soil quality index, ecosystem multifunctionality, microbial diversity, organic fertilizer, tobacco yield, proportion of premium-grade leaves

Citation: Yang W, He B, Li J, Wang Z, Tong W, Zhu B, Xiao Z, Deng X and Wang B (2025) Enhancing soil health and tobacco productivity with different organic amendments: evidence from a 7-year field experiment. Front. Soil Sci. 5:1698802. doi: 10.3389/fsoil.2025.1698802

Received: 04 September 2025; Accepted: 20 November 2025; Revised: 13 November 2025;

Published: 05 December 2025.

Edited by:

Sudip Sengupta, Swami Vivekananda University, IndiaReviewed by:

Chaosheng Luo, Yunnan Agricultural University, ChinaBipradeep Mondal, Central University of Jharkhand, India

Animesh Ghosh Bag, Swami Vivekananda University, India

Copyright © 2025 Yang, He, Li, Wang, Tong, Zhu, Xiao, Deng and Wang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xiaopeng Deng, aGRkeHBAMTYzLmNvbQ==; Bin Wang, d2FuZ2JpbjAxQGNhc3MuY24=

Wei Yang

Wei Yang Biao He3

Biao He3 Junying Li

Junying Li Bo Zhu

Bo Zhu Zhihua Xiao

Zhihua Xiao Bin Wang

Bin Wang