- 1Center of Excellence for Soil and Fertilizers Research in Africa, College of Agriculture and Environmental Science, Mohammed VI Polytechnique, Ben Guerir, Morocco

- 2Bioresources and Food Safety Laboratory, Guéliz, Faculty of Sciences and Technology Marrakech, Cadi-Ayyad University, Marrakech, Morocco

Tropical agricultural soils are exposed to diverse management practices that influence soil fertility, trace metal accumulation, and food safety. Understanding how soil fertility interacts with trace metal uptake across crop systems is vital for sustainable tropical agriculture. This study assessed soil fertility, trace metal bioaccumulation, and pollution load across four land use systems, cacao (Theobroma cacao), oil palm (Elaeis guineensis), cocoyam (Xanthosoma sagittifolium), and maize (Zea mays) cultivated on Ferralsols and Acrisols in Western Ghana. Soil chemical properties, including total organic carbon (TOC), total nitrogen (TN), available phosphorus (P2O5), pH, exchangeable potassium (K), and cation exchange capacity (CEC), were analyzed to compute the Soil Fertility Index (SFI). Bioconcentration factors (BCFs) for Al, Cd, Cu, Mn, Ni, Zn, Sr, and Ti were determined from plant and soil concentrations, while contamination factors (CFs) and the Pollution Load Index (PLI) evaluated overall soil contamination. SFI values ranged from 0.41 ± 0.13 in Ferralsols under maize to 0.78 ± 0.26 in Acrisols under cacao. Cacao grown on Ferralsols exhibited the highest uptake of Mn (1.98 × 10⁻⁴ ± 1.15 × 10⁻⁴), Cu (1.70 × 10⁻³ ± 1.21 × 10⁻³), and Sr (2.32 × 10⁻³ ± 1.53 × 10⁻³), while maize and oil palm showed minimal accumulation, likely due to selective ion uptake and exclusion mechanisms. PLI values were uniformly low (1.56 × 10⁻⁵–8.08 × 10⁻⁵), indicating uncontaminated soils. SFI correlated strongly with BCF-Ni (r = 0.93), whereas Cd, Cu, and Zn uptake depended more on soil pH and organic carbon than overall fertility. PCA distinguished crop–soil elemental patterns, with Cu, Ni, Mn, Cd, and Ti dominant in cacao/Acrisol systems and Sr and Zn in oil palm/Ferralsol systems. Although soil was largely uncontaminated, elevated metal uptake in some systems (e.g., cacao/ Ferralsol) indicates that high fertility does not necessarily equate to soil health. Trace metal accumulation is primarily governed by plant specific ion selectivity and exclusion behaviors, warranting further investigation to define threshold ion concentrations for sustainable soil–plant health management).

1 Introduction

Soils form the foundation of terrestrial ecosystems by regulating food production, nutrient cycling, water purification, carbon sequestration, and biodiversity support (1, 2). In tropical regions, particularly sub-Saharan Africa, rapid population growth and rising food demand have intensified land use and increased pressure on soil resources. Soil fertility defined as the capacity of soil to supply essential nutrients to plants remains central to agricultural productivity and ecosystem resilience (3). However, unsustainable land management, including nutrient mining, declining organic matter inputs, and structural degradation, continues to undermine fertility and reduce long-term productivity.

In Ghana, agriculture remains a cornerstone of the national economy, contributing approximately 20% of GDP in 2024 and supporting the livelihoods of over half of the population (4). Cacao (Theobroma cacao), oil palm (Elaeis guineensis), maize (Zea mays), and cocoyam (Xanthosoma sagittifolium) dominate the farming landscape. Among these, cacao is the most economically significant, covering ~1.6 million hectares and contributing 5–8% of GDP while generating over US$2 billion in export revenues annually (4, 5). Despite its economic role, cacao productivity is increasingly threatened by soil fertility decline, pests, and aging plantations. Oil palms have expanded rapidly to meet food and bioenergy demand but is frequently linked with nutrient depletion under intensive cultivation. Maize, the main staple crop, is highly nutrient demanding and vulnerable to poor fertility conditions, while cocoyam provides dietary diversity but remains constrained by soil degradation and disease. These systems collectively highlight the economic importance and ecological vulnerability of tropical land use in Ghana.

The soils sustaining these crops are predominantly Acrisols and Ferralsols. Ferralsols, abundant in Ghana’s forest and transition zones, are strongly weathered, acidic, and dominated by Fe/Al oxides and low-activity clays. While oxides enhance sorption of trace metals, these soils possess low cation exchange capacity (CEC) and limited nutrient retention, restricting fertility (6). Acrisols, widespread in the forest savanna transition, are similarly nutrient-depleted but exhibit lower buffering capacity and more severe fertility losses under continuous cultivation (7). Given their extensive coverage, assessing fertility and contaminant dynamics in Acrisols and Ferralsols is crucial for understanding sustainability in Ghana’s major cropping systems.

Alongside fertility decline, the accumulation of potentially toxic elements (PTEs) such as cadmium (Cd), lead (Pb), copper (Cu), and zinc (Zn) poses risks to food safety and environmental health. PTEs originate from both geogenic weathering and anthropogenic inputs including phosphate fertilizers, sewage sludge, and atmospheric deposition (8). Their mobility and plant uptake are strongly influenced by soil properties such as pH, organic matter, clay mineralogy, and oxide content. Bioaccumulation of PTEs in edible tissues can present direct risks to human health through food chain transfer (9). The bioconcentration factor (BCF) the ratio of plant tissue concentration to total or available soil concentration serves as a widely used indicator of plant uptake potential (7). In parallel, integrative indices such as the Soil Fertility Index (SFI) provide quantitative measures of soil productivity potential ({Formatting Citation}.

Despite progress in soil fertility diagnostics and pollution assessments, most previous studies in Ghana have addressed these dimensions separately (10, 11). The interlinkages among soil fertility status, trace element bioconcentration, and ecological risk indices remain poorly understood, particularly across contrasting crop types and soil groups. This knowledge gap constrains the design of integrated soil and crop management strategies that can balance productivity with food safety.

This study addresses this gap by conducting a comparative assessment of soil fertility and trace element bioconcentration in cacao, oil palm, maize, and cocoyam systems established on Acrisols and Ferralsols in Western Ghana. Specifically, we characterize soil physicochemical properties, evaluate fertility status using the Soil Fertility Index, quantify Cd, Pb, Cu, and Zn uptake using the Bioconcentration Factor, and finally assessing the nexus between fertility, bioconcentration, and pollution indices. By integrating soil fertility and contaminant risk evaluation, the study provides insights to guide sustainable land management and food safety strategies in tropical agroecosystems.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Study area overview

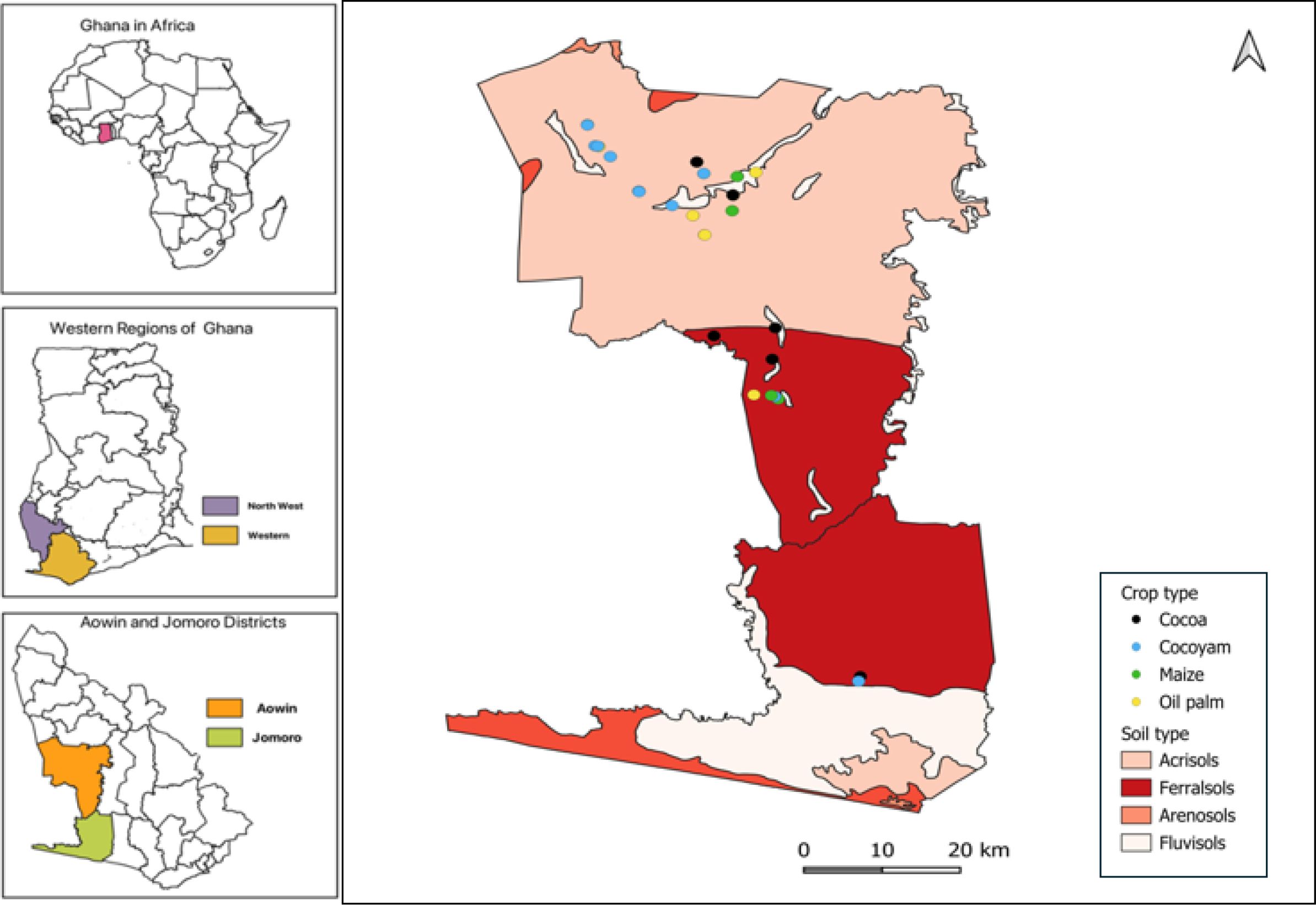

The study was carried out in the Aowin and Jomoro districts of Ghana’s Western Region, an area characterized by a humid tropical climate and classified ecologically as wet evergreen and moist semi-deciduous forest zones. Annual rainfall averages 1,500–2,000 mm, concentrated from April to October, while mean monthly temperatures range from 22°C in August to 34°C in March. Relative humidity is typically high (60–90%), supporting intensive crop production systems (12). The dominant soils are Ferralsols and Acrisols (13), both highly weathered, acidic, and nutrient-depleted, but extensively cultivated for both perennial and annual crops.

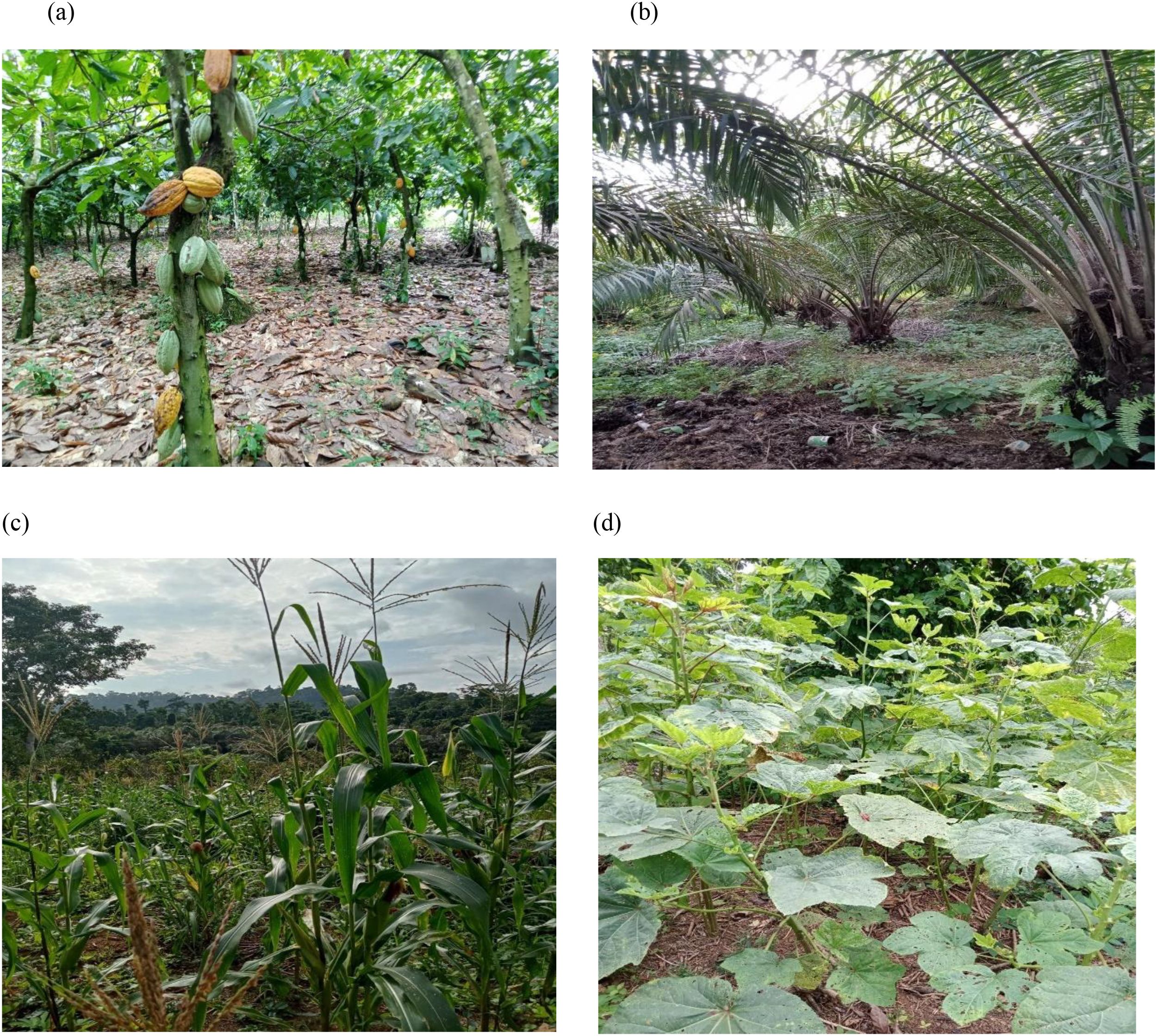

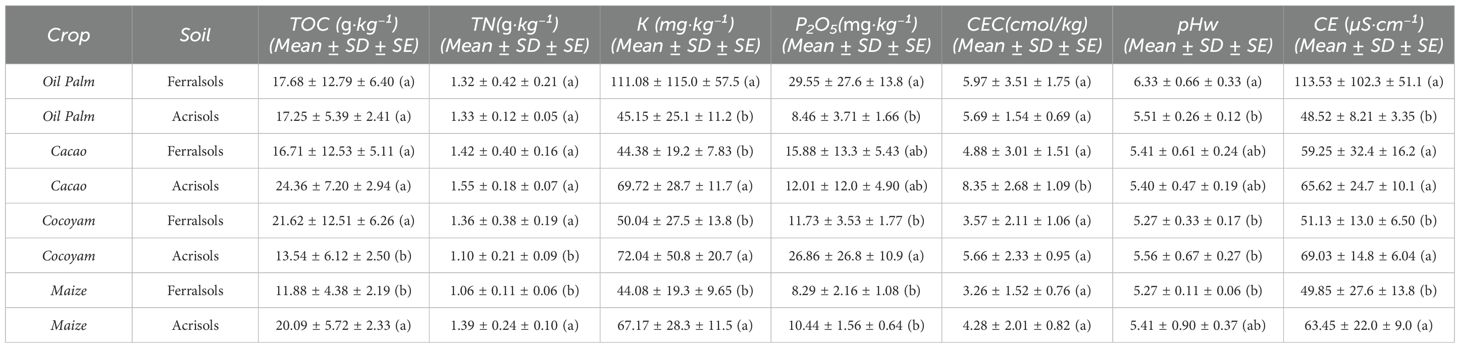

Four land use systems were selected for this study cacao, oil palm, maize, and cocoyam (Figure 1) representing the most economically and nutritionally important cropping systems in the region. Cacao (Theobroma cacao) Cultivation in the study area is based largely on hybrid and improved Amelonado varieties (14). Cacao is typically established as a monoculture or with shade trees in smallholder farms ranging from 2–5 ha. Plantations are long-lived (25–30 years), with productivity declining significantly after 20 years, at which point replanting is common. Management includes manual weeding, periodic application of inorganic fertilizers and pesticides, and occasional pruning. However, nutrient replenishment is often inadequate, contributing to gradual soil fertility decline (15).

Figure 1. Photographs showing the four land use systems of the study area investigated in Western Ghana namely (a) cacao (Theobroma cacao), (b) oil palm (Elaeis guineensis), (c) maize (Zea mays), and (d) cocoyam (Xanthosoma sagittifolium).

For Oil Palm (Elaeis guineensis) plantations, they are established mainly through improved tenera varieties, with cultivation cycles of 25–30 years. Both smallholder plots and larger estates are present. Planting density averages 143 palms per hectare, and management includes fertilizer application, ring weeding, and harvesting of fresh fruit bunches every 10–14 days once the palms reach maturity (3–4 years after planting) (16). Replacement of aging plantations is generally staggered but often constrained by high input costs.

Maize (Zea mays) is cultivated as a major staple crop, predominantly in smallholder systems (1–3 ha) and under rainfed conditions. Open pollinated varieties and hybrids are used, with two main cropping seasons: the major season (April–July) and the minor season (September–November) (17). Management practices include ploughing or slash-and-burn land preparation, low-to-moderate fertilizer application (NPK and urea), and manual weeding. Crop cycles last 90–120 days, and land is often left fallow for 1–2 years where land pressure permits (18).

As for Cocoyam (Xanthosoma sagittifolium), it is cultivated mainly in intercropping systems, often under partial shade in forested zones. Propagation is through cormels or suckers, and the crop requires from 8 to 12 months to mature. Cultivation is largely rainfed, with limited fertilizer inputs (19). Management includes hand-weeding and mulching, and productivity is highly influenced by soil fertility status and disease pressures (particularly cocoyam root rot complex). Farmers typically reestablish cocoyam in the same field after short fallow periods (2–3 years) (20).

Together, these land use systems reflect the diversity of crop management strategies in Western Ghana, ranging from long lived perennial plantations (cacao and oil palm) to short cycle annual and semi perennial food crops (maize and cocoyam). Their contrasting growth cycles, nutrient demands, and management practices create distinct soil fertility pressures and influence the accumulation and uptake of potentially toxic elements.

2.2 Soil sampling and analysis

The study was conducted in tropical agricultural regions dominated by Acrisols and Ferralsols, with a focus on four widely cultivated crops: Theobroma cacao (cacao), Elaeis guineensis (oil palm), Zea mays (maize), and Xanthosoma sagittifolium (cocoyam) (Figure 2). A total of 40 surface soil samples (0–20 cm) and 48 plant samples were collected from 24 plots covering representative fields across the two soil types.

2.2.1 Soil sampling and preparation

Soil sampling was performed with a stratified strategy based on crop and soil type. For each crop, five replicate samples were collected from Ferralsols, and six replicate samples from Acrisols, resulting in a total of 40 composite surface soil samples. Each composite sample was obtained by mixing sub-samples collected from the 0–20 cm layer using a stainless-steel auger. The samples were air-dried, ground with a mortar and pestle, passed through a 2 mm sieve, and stored for laboratory analysis.

2.2.2 Soil major nutrient analysis

Total organic carbon (TOC) and total nitrogen (TN) were quantified by the Dumas dry combustion method using a Thermo Scientific Flash Smart elemental analyzer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). Soil pH and electrical conductivity (EC) were determined in a 1:2 soil:water ratio. Exchangeable potassium (K+) was extracted with 1 M ammonium acetate (NH4OAc) at pH 7.0 (21) and measured by flame photometry. Olsen phosphorus was extracted with 0.5 M sodium bicarbonate at pH 8.5 and determined according to ISO 11263 (2013). Cation exchange capacity (CEC) was determined following NF ISO 23470, based on ammonium displacement and subsequent quantification.

2.2.3 Total trace element analysis

Elemental analysis of the 40 surface soil samples was performed using inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES) following the NF EN 16170 (2016) standard. Soil samples (50–100 mg, ≤2 mm) were digested with a mixture of nitric acid, hydrochloric acid, and hydrogen peroxide using a microwave-assisted system. Digested solutions were analyzed on an Agilent 5800 VDV ICP-OES, and concentrations were calculated using calibration curves prepared from multi-element standards. Data quality was ensured by analyzing certified reference materials and procedural blanks, with recoveries within ±10% and relative standard deviations below 5%. Elemental concentrations are reported on a dry weight basis (mg·kg⁻¹ soil).

2.3 Plant sampling and analysis

2.3.1 Plant sampling procedure

Plant samples were collected for the same crops across the 24 plots from which the soils were sampled. For each crop (cacao, oil palm, maize, and cocoyam), six georeferenced sampling points were selected using a systematic approach to ensure representative coverage of the site. At each point, plant tissue was sampled from both bark and leaves of individual plants.

Each plant sample consisted of two subsamples (bark and leaf), collected from the same plant and kept separately in labeled, clean bags to avoid cross contamination. In total, 48 plant tissue samples (24 bark and 24 leaf samples) were prepared and transported to the laboratory for elemental analysis.

2.3.2 Plant sample preparation and analysis

Plant tissues (leaves and bark) were carefully separated, washed with deionized water to remove surface dust, and oven-dried at 80°C for 24 h. The dried samples were then crushed and stored in sealed bottles. Approximately 0.3 g of powdered plant material was weighed for digestion.

Digestion was carried out using a microwave-assisted system (Berghof Speedwave 4 DAP-60þ) by adding 8 mL concentrated nitric acid (HNO3, 65%) and 2 mL hydrogen peroxide (H2O2, 30%) to each sample. The mixture was digested under controlled heating until a clear solution was obtained, which was then diluted to 25 mL with ultrapure water and transferred to a volumetric flask (12, 22). Trace element concentrations were measured using an Agilent 5800 VDV ICP-OES in both axial and radial modes. Each sample was analyzed in triplicate with a 10-second integration time per replicate. Calibration was performed using multi-element standard solutions prepared in 2% HNO3. Quality control included procedural blanks, certified reference plant materials (e.g., NIST 1573a Tomato Leaves), and replicate analyses. Recoveries of reference materials were maintained within ±10% of certified values, and relative standard deviations (RSDs) of replicate measurements were generally below 5%, ensuring accuracy and precision. Elemental concentrations were expressed on a dry weight basis (mg·kg⁻¹).

2.4 Data analysis

The study employed the Equations [1–3] presented below to calculate the soil fertility index, bio-concentration factor and soil pollution load index to examine the effect of tropical land uses systems and draw an insight over the nexus of three factors for sustainable decision support.

2.4.1 Soil fertility index

The SFI, based on the principle of the weighted sum evaluation method (23) was calculated according to [Equation 1]:

To integrate these parameters into a single, comparable measure of soil productivity potential, the Soil Fertility Index (SFI) was calculated using the weighted formula [Equation 2]:

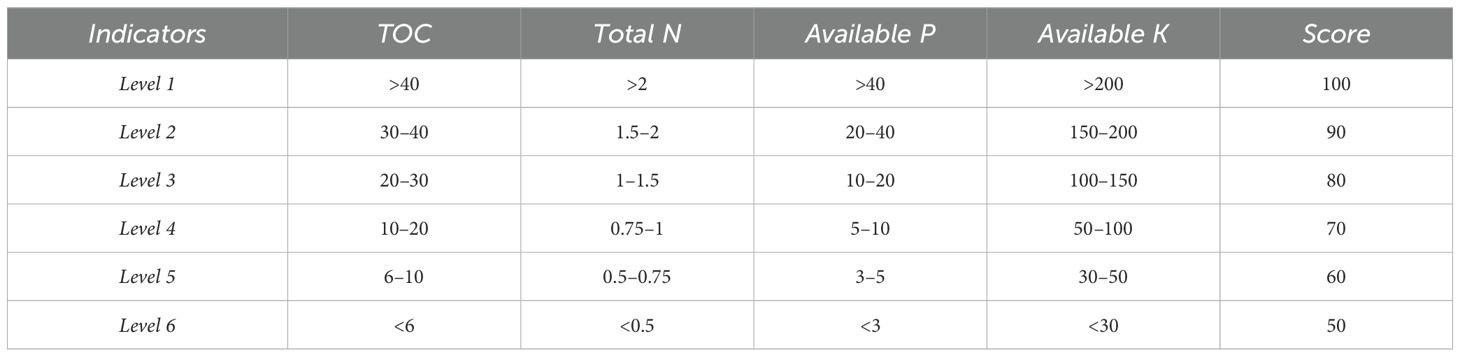

The SFI was calculated separately for each replicate, this approach assigns the greatest weight to TOC, given its central role in nutrient retention, structure, and microbial activity, followed by TN and P availability, with K contributing slightly less to the composite score (Table 1). This approach allowed capturing the within-field variability and presenting both individual and mean SFI values (Table 2). To facilitate interpretation of the calculated SFI values, we adopted the fertility classification proposed by (24), where index values of 0.00–0.25 are considered Very Low, 0.25–0.50 Low, 0.50–0.75 Moderate, 0.75–0.90 High, and 0.90–1.00 Very High. This classification enabled the translation of numerical SFI values into categorical fertility levels, providing a clearer assessment of soil productivity potential across crops and soil types.

Table 1. Criteria for classification of fertility levels (23).

Table 2. Weighting coefficient of the parameter (23).

2.4.2 Bioconcentration factor

It was calculated for PTE in plant species by using [Equation 3] (25):

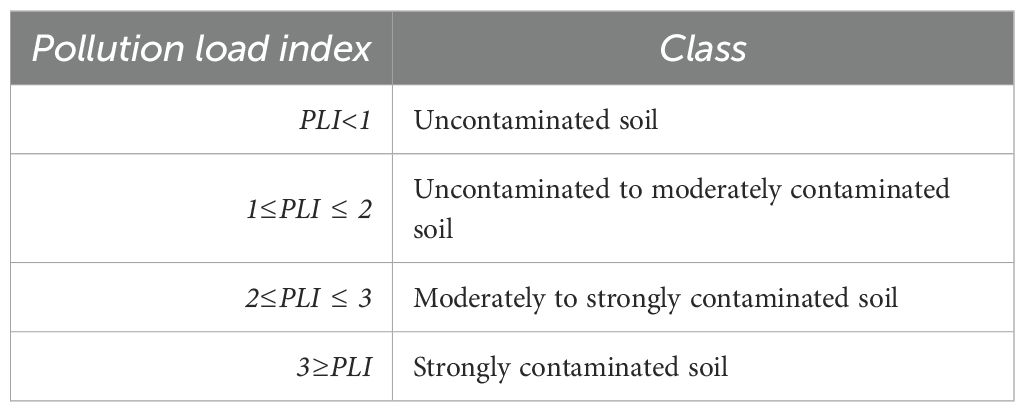

2.4.3 Soil pollution load index

PLI provides an overall assessment of soil contamination by PTEs and is calculated using [Equation 3] (26) and interpreted as follows:

Where the CF is a contamination factor of each PTE and is calculated by dividing the pollutant’s concentration in the polluted sample by its background or baseline concentration.

Data interpretation table for PLI (Table 3):

2.5 Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted to assess the influence of soil type and land use systems on soil physicochemical properties, as well as derived indices, including the Soil Fertility Index (SFI) and Pollution Load Index (PLI). Data normality and homogeneity of variances were evaluated using the Shapiro-Wilk and Levene’s tests, respectively. Two-way ANOVA was employed to examine the effects of soil type and crop type on BCF values, soil properties, SFI, and PLI, followed by Tukey’s Honest Significant Difference (HSD) post-hoc test to identify significant differences among means, with significance set at p< 0.05. BCF and SFI results are reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD). All statistical analyses were performed in R software version 4.3.0, utilizing the dplyr, tidyr, and agricolae packages (27). Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was carried out using the FactoMineR and factoextra packages to explore relationships among soil variables, SFI, BCF, PLI, and crop types. Prior to PCA, data were standardized using z-score transformation. Pearson correlation matrices, generated from mean values per crop (n = 4) using the GGally::ggcorr() function, were used to evaluate associations among soil properties, indices, and plant metal uptake. Biplots and correlation plots facilitated visualization of sample clustering and the contributions of variables across soil-crop combinations.

3 Results and discussion

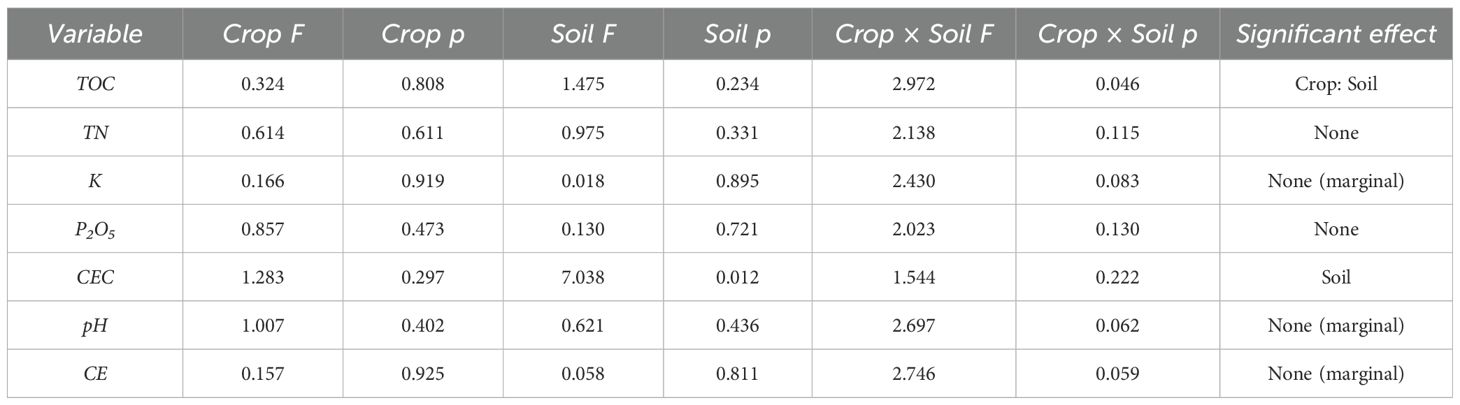

3.1 Selected chemical properties of Acrisols and Ferralsols

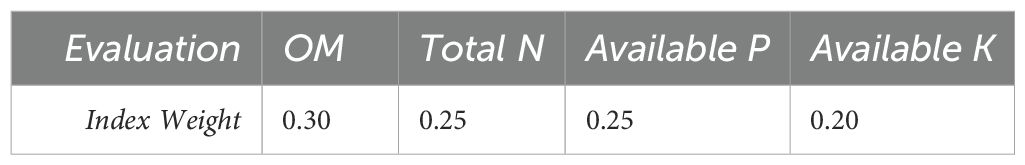

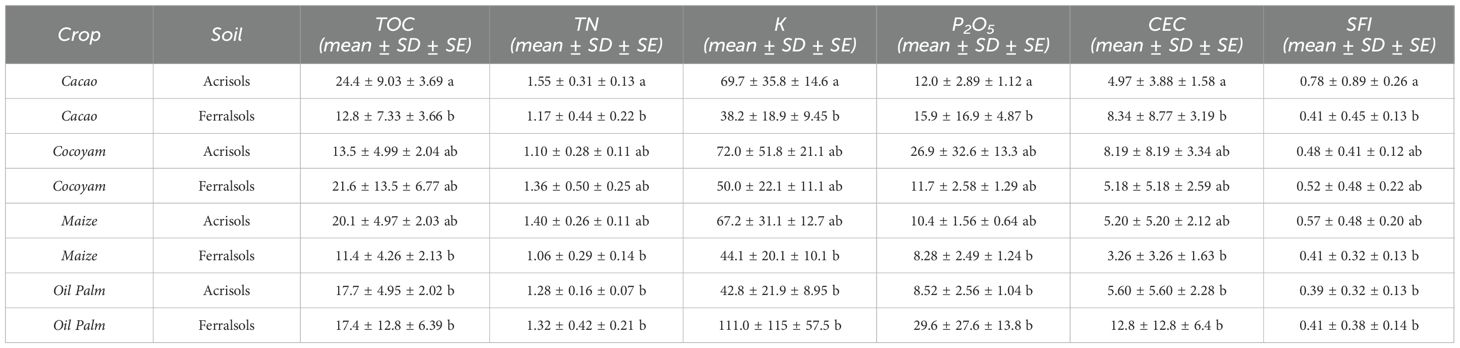

The chemical characteristics of Acrisols and Ferrasols under four major land use systems oil palm, cacao, cocoyam, and maize were evaluated to understand how soil type and land use influence soil fertility. Key parameters measured included soil (pH), cation exchange capacity (CEC), electrical conductivity (EC), total organic carbon (TOC), total nitrogen (TN), exchangeable potassium (K), and available phosphorus (P2O5). The results, summarized in Table 4, provide a comparative overview of these soil properties across the different crop-soil combinations.

Table 4. Summary statistics of selected soil chemical properties of Acrisols and Ferralsols under different cropping systems in tropical agricultural fields.

3.1.1 Electrical conductivity

Electrical conductivity differed markedly between Acrisols and Ferralsols. Ferralsols under oil palm showed the highest EC (113.52 µS/cm), far exceeding Acrisols under the same crop (58.96 µS/cm). This pattern suggests that Ferralsols, despite their strong weathering, may retain higher ionic concentrations when coupled with perennial systems that supply large amounts of residues, such as oil palm. Maize and cocoyam systems, irrespective of soil type, maintained comparatively low EC values (<70 µS/cm), consistent with their rapid nutrient uptake and lower organic inputs. Across all systems, EC values remained below 1 dS/m, confirming non-saline conditions suitable for crop growth. These findings conform with previous reports from West African Ferralsols, where perennial plantations showed elevated EC relative to annual systems (28, 29).

3.1.2 Total organic carbon

TOC content also varied substantially by crop and soil type (Table 5). Cacao grown on Ferralsols showed the highest mean TOC (2.2%), indicative of enhanced carbon sequestration possibly facilitated by continuous litter fall, reduced soil disturbance, and shade tree presence, which promote microbial biomass and nutrient cycling (28–30). Acrisols under cacao had even higher TOC levels (2.4%), underscoring the interaction between crop system and soil type in sustaining organic matter. Conversely, oil palm on Ferralsols had lower TOC (2.2%) than cacao but similar on Acrisols (2.3%). Maize and cocoyam systems exhibited moderate TOC values (range: 1.2–2.1%), likely reflecting their shorter growing seasons and frequent soil disturbance, which accelerate organic matter decomposition (31). Overall, our results highlight that both soil type and cropping system influence organic carbon stocks, but within this study, contrasts among crop types and their management practices were more pronounced than differences between Acrisols and Ferralsols (9).

3.1.3 Total nitrogen

Total nitrogen (TN) content varied across soils and cropping systems, reflecting both soil type and management practices. Acrisols under cacao recorded the highest TN (1.55 g/kg), followed closely by Ferralsols under oil palm (1.45 g/kg), indicating that perennial crops with substantial litter input and limited soil disturbance promote nitrogen accumulation. Conversely, maize soils exhibited lower TN values, with Ferralsols at 1.06 g/kg and Acrisols at 1.39 g/kg, consistent with the rapid nutrient removal typical of annual cropping systems and shorter periods for organic matter incorporation. Cocoyam soils showed intermediate TN levels, ranging from 1.10 g/kg in Acrisols to 1.36 g/kg in Ferralsols, suggesting moderate nitrogen enrichment through organic amendments or residue retention. These patterns agree with previous studies reporting that perennial tree-based systems, such as cacao and oil palm, enhance soil nitrogen stocks relative to annual crops, due to continuous litterfall, deeper rooting systems, and improved microbial nutrient cycling (28).

3.1.4 Available P

(K) and (P2O5) reflected the combined effects of crop type and soil. Oil palm on Ferralsols showed the highest exchangeable K (111.33 mg/kg), likely due to the nutrient release from abundant litter residues. Conversely, cacao on Ferralsols recorded lower K (38.23 mg/kg), possibly reflecting uptake patterns or differences in fertilization regimes. P availability showed less variation but tended to be higher under crops with perennial biomass accumulation (e.g., cacao, cocoyam) relative to annual maize cropping.

Exchangeable K.

3.1.5 Soil pH

Soil pH ranged from slightly acidic to moderately acidic across all systems, with values between 5.2 and 6.3. Oil palm on Ferrasol soils recorded the highest pH (6.3), which could relate to the accumulation of base cations from residue decomposition and fertilizer inputs (32). Acrisols generally exhibited lower pH values, consistent with their typical higher weathering status and acidification susceptibility (13).

3.1.6 Cation exchange capacity

CEC was consistently higher in Acrisols than Ferralsols across all crops. Cacao/Acrisol had the highest CEC (8.35 cmol/kg), while cacao/Ferrasol had the lowest (2.19 cmol/kg). This indicates that Acrisols, despite being acidic, retain greater nutrient-holding capacity, likely due to higher organic matter and clay content. These results confirm the general pedological distinction that Acrisols possess higher CEC compared to Ferralsols (33). Similar patterns have been observed in West African agroecosystems, where Acrisols exhibited higher nutrient retention potential than highly leached Ferralsols (34).

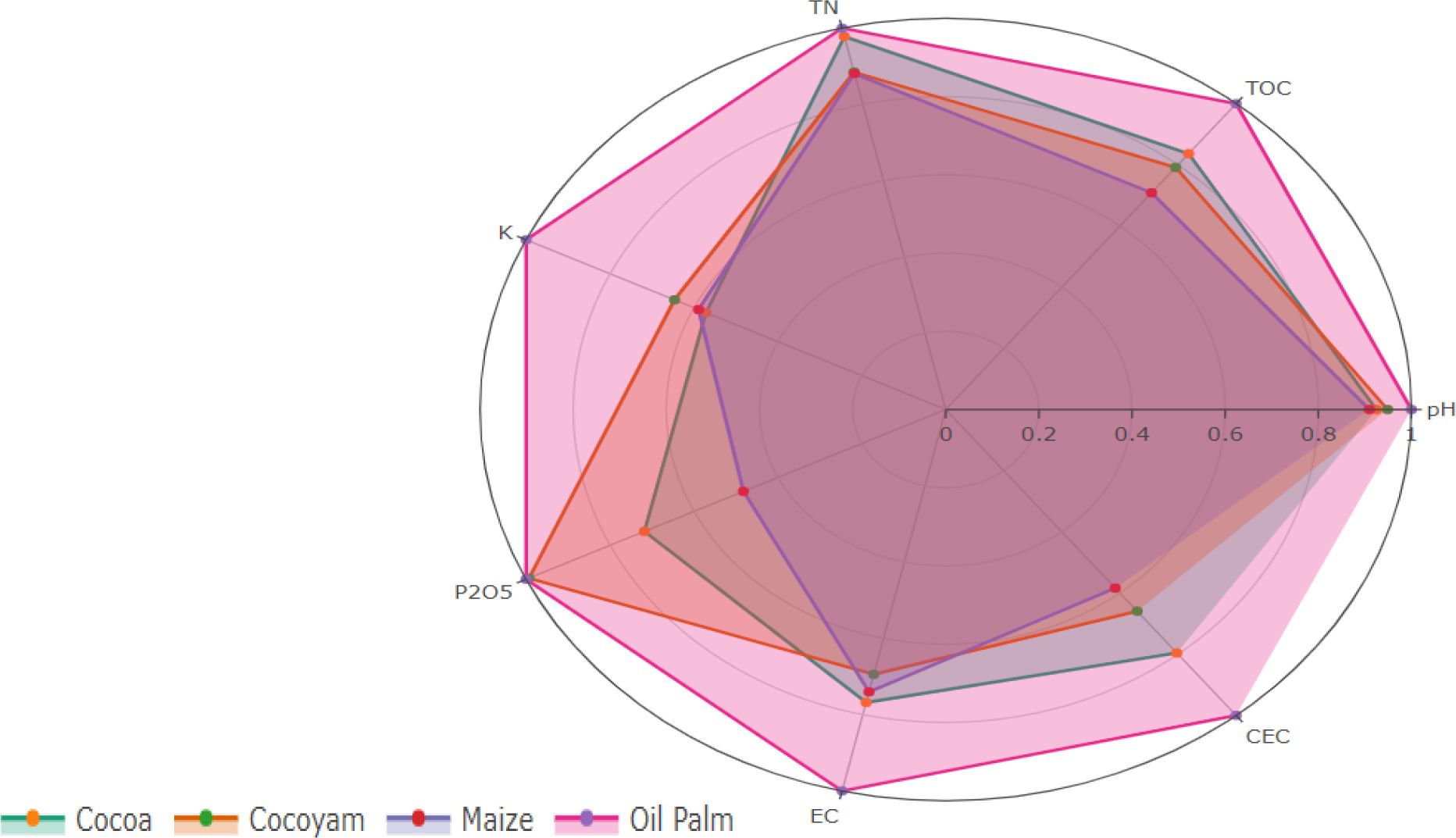

A radar chart (Figure 3) was used to display normalized chemical parameters across the four crop types. Distinct colors (oil palm = teal, cacao = orange, cocoyam = purple, maize = pink) aid comparison. The plot shows that perennial crops (oil palm and cacao) generally maintain higher values for key fertility parameters (EC, TOC, exchangeable K), while annual crops (maize, cocoyam) show lower values due to shorter cycles and greater disturbance. This visualization summarizes soil fertility variation among cropping systems and complements the detailed numerical results.

Figure 3. Radar chart illustrating normalized soil physicochemical parameters across four cropping systems (oil palm, cocoyam, and maize). Each polygon represents the average normalized values (0–1 scale) of soil pH, TOC, TN, K, P2O5, EC, and CEC for each crop type.

3.2 Tropical land use systems effect on soil fertility indices

Nutrient concentrations varied substantially among the different land use system soil combinations (Table 6). The four land-use systems exerted distinct influences on the fertility of Acrisols and Ferralsols, as reflected by the Soil Fertility Index (SFI) and supported by statistical analysis (Table 6). SFI values ranged from 0.39 ± 0.32–0.13 b in oil palm/Acrisols to 0.78 ± 0.89–0.26 a in cacao/Acrisols. According to Tukey’s post-hoc test, the SFI values of cacao/Acrisols were significantly higher than those of most other crop–soil combinations, whereas maize/Ferralsols, oil palm/Acrisols, and oil palm/Ferralsols shared lower SFI values, showing no significant differences among them.

Table 6. ANOVA and summary statistics of soil fertility index (SFI) values for different crop-soil combinations in Ferralsols and Acrisols.

These patterns indicate that crop type exerts a strong influence on soil fertility outcomes, in some cases exceeding the effect of soil type. Perennial systems such as cacao generally maintain higher fertility indices because of continuous litter inputs, root turnover, and reduced soil disturbance enhance soil organic carbon, buffer pH, and improve nutrient retention. In contrast, annual systems such as maize are associated with more intensive soil disturbance, lower organic matter accumulation, and higher nutrient depletion, leading to reduced SFI values. Thus, fertility dynamics in these tropical soils are shaped not only by the intrinsic properties of Acrisols and Ferralsols, but also critically by the management and biological legacies of the cropping system.

When analyzed by soil type, Acrisols under cacao showed the highest fertility (SFI = 0.78 a), while Ferralsols under maize and oil palm had the lowest (0.41 b). Cocoyam systems maintained intermediate values (0.48–0.52 ab) across both soils, suggesting semi-perennial crops sustain moderate fertility regardless of soil type. Ferralsols supported lower fertility under cacao but comparable or slightly higher values under cocoyam and oil palm, highlighting that crop–soil interactions strongly influence fertility, as confirmed by the significant Crop × Soil effect in the two-way ANOVA.

Analysis of individual soil properties provides insight into how each parameter contributed to the observed SFI patterns. Total organic carbon (TOC) ranged from 11.4 ± 4.26–2.13 b g kg⁻¹ in maize/Ferralsols to 24.4 ± 9.03–3.69 a g kg⁻¹ in cacao/Acrisols, following the SFI trend. Higher TOC in perennial systems, particularly cacao/Acrisols, reflects greater organic matter inputs and reduced disturbance. Total nitrogen (TN) mirrored TOC patterns, with the lowest value in maize/Ferralsols (1.06 ± 0.29–0.14 b g kg⁻¹) and the highest in cacao/Acrisols (1.55 ± 0.31–0.13 a g kg⁻¹), highlighting the strong influence of organic matter on nitrogen accumulation.

(K) levels were notably elevated in oil palm/Ferralsols (111.0 ± 115–57.5 b mg kg⁻¹) and cocoyam/Acrisols (72.0 ± 51.8–21.1 ab mg kg⁻¹), while phosphorus (P2O5) peaked in oil palm/Ferralsols (29.6 ± 27.6–13.8 b mg kg⁻¹) and cocoyam/Acrisols (26.9 ± 32.6–13.3 ab mg kg⁻¹). These nutrients contributed variably to the SFI, with perennial crops maintaining higher stocks of K and P2O5 due to reduced nutrient removal and continuous litter inputs, whereas annual systems such as maize/Ferralsols had lower stocks (K = 44.1 ± 20.1–10.1 b mg kg⁻¹; P2O5 = 8.28 ± 2.49–1.24 b mg kg⁻¹).

(CEC) followed a similar trend, with cacao/Acrisols exhibiting the highest values (4.97 ± 3.88–1.58 a cmolc kg⁻¹) and maize/Ferralsols among the lowest (3.26 ± 3.26–1.63 b cmolc kg⁻¹). These variations underscore the role of soil texture and organic matter in nutrient retention, further influencing SFI outcomes.

In summary, perennial systems, particularly cacao and oil palm, consistently maintained higher fertility, largely due to higher TOC, TN, and associated nutrient stocks, whereas annual maize systems were generally less fertile. Statistical analysis confirmed significant differences between crop–soil combinations, supporting the use of SFI as a holistic indicator that integrates multiple soil properties to assess fertility under different land-use systems. These results emphasize that land use system types and management practices are key drivers of soil fertility in tropical Acrisols and Ferralsols, in line with previous reports (23, 35).

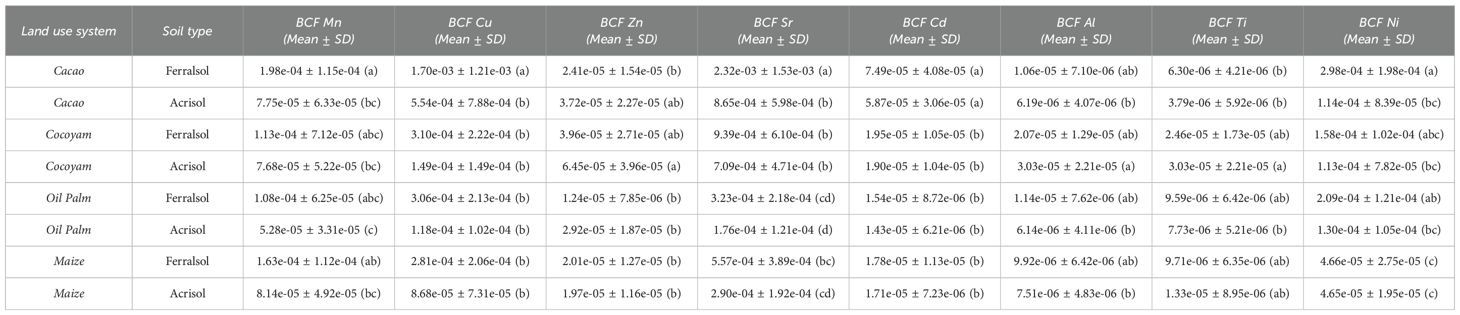

3.3 Bioconcentration of PTEs as influenced by the tropical land use systems

The bioconcentration factors (BCFs) reported in this study (10⁻5–10⁻³) were markedly lower than those commonly documented in tropical agroecosystems (Table 7). Previous work in West Africa has shown Cd and Cu BCFs in cacao beans ranging from 0.01 to 0.2 when calculated against extractable soil fractions, and in some contaminated sites, values may even exceed unity (36, 37). Similarly, cocoyam and maize cultivated on Acrisols and Ferralsols have been reported to exhibit BCFs of 0.001–0.05 for Zn and Ni (37). The comparatively smaller values observed here can be attributed to methodological and pedological factors. First, BCFs were calculated relative to total soil metal concentrations determined by complete digestion, which incorporates both labile and non-labile pools, including metals bound to silicates, oxides, and organic matter. This broader denominator inherently suppresses the magnitude of BCFs relative to studies based on DTPA- or Mehlich-extractable fractions, which approximate the bioavailable pool and typically yield values one to two orders of magnitude higher (37, 38). Moreover, the strong sorption capacity of highly weathered Acrisols and Ferralsols, enriched in Fe and Al oxides, further constrains trace element mobility and uptake.

Table 7. ANOVA and summary statistics of soil and plant metal concentrations across crop types and soil types, with mean ± SD bioconcentration factors (BCFs) and significance letters for selected potentially toxic elements (PTEs).

Within this overall low range, notable crop–soil differences emerged. Cacao grown on Ferralsols showed the highest BCFs for Mn (1.98 × 10⁻4 ± 1.15 × 10⁻4, a), Cu (1.70 × 10⁻³ ± 7.88 × 10⁻4, a), and Sr (2.32 × 10⁻³ ± 1.00 × 10⁻³, a), reflecting a greater tendency to accumulate both micronutrients and potentially toxic elements. This aligns with reports that perennial tree crops such as cacao, due to their extensive root systems and continuous nutrient demand, often display elevated uptake in Cu-enriched soils from natural and anthropogenic inputs (39). By contrast, cacao cultivated on Acrisols exhibited significantly lower BCFs (e.g., Cu 5.54 × 10⁻4 ± 7.88 × 10⁻4, b), underscoring the role of soil weathering and mineral composition in limiting bioavailability. Recent reviews (40) further highlight that varietal selection, soil amendments such as liming or organic matter addition, and spatial zoning (avoiding high-Cd soils) are key strategies to mitigate cadmium accumulation in cacao, emphasizing the importance of both soil properties and management practices in controlling element uptake.

Cocoyam demonstrated intermediate BCF values for Zn (6.45×10⁻5 ± 2.70×10⁻5, a) and Ni (1.58×10⁻4 ± 8.35×10⁻5, abc), with higher uptake in Acrisols for Al and Ti, suggesting that root morphology and tuber storage organs may influence element partitioning (41). These observations align with previous studies showing that root crops in West African Ferralsols and Acrisols exhibit selective accumulation of essential and non-essential metals, likely driven by both soil chemistry and plant physiology (22).

Oil palm exhibited consistently low BCFs across most elements, including Zn (2.92×10⁻5 ± 1.21×10⁻5, b) and Ti (7.73×10⁻6 ± 3.42×10⁻6, b), reflecting its limited metal uptake capacity relative to cacao and cocoyam. The lower BCFs for perennial monocot crops like oil palm have been previously attributed to restricted root exudation and selective nutrient uptake. Maize, a fast-growing annual cereal, showed the lowest BCFs for Ni (4.65×10⁻5 ± 2.43×10⁻5, c) and Zn (1.97×10⁻5 ± 9.21×10⁻6, b), corroborating literature indicating that annual grasses generally accumulate trace elements less efficiently than tuber and tree crops.

Overall, the pattern of BCFs followed the order: cacao > cocoyam > oil palm ≈ maize, with Ferralsols generally promoting higher bioaccumulation than Acrisols. The variation in statistical groupings emphasizes significant differences in metal uptake both among crop types and between soil types. These findings suggest that both plant physiology and soil physicochemical properties including pH, cation exchange capacity, and clay oxide content play critical roles in modulating trace element mobility and bioavailability in tropical agricultural systems.

From a risk assessment perspective, the higher BCFs observed for Cd in cacao (7.49×10⁻5 ± 4.08×10⁻5, a) and Sr indicate potential for food chain transfer, whereas crops like maize and oil palm present lower risks of heavy metal accumulation. Such crop specific accumulation trends are crucial for developing targeted soil and crop management strategies aimed at minimizing toxic element exposure while maintaining micronutrient supply.

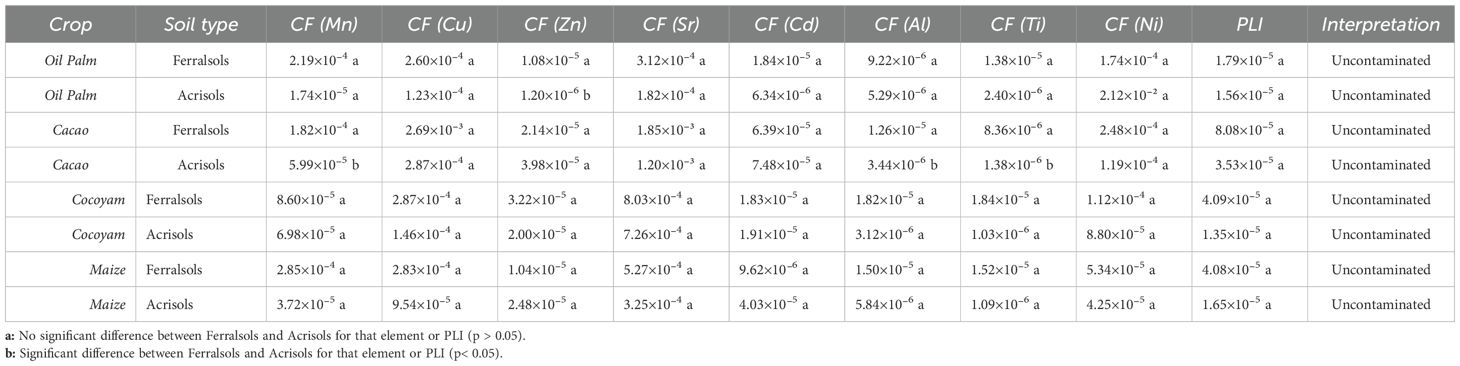

3.4 Soil pollution load as influenced by the tropical land use system

The Soil Pollution Load Index (PLI) provides an integrated metric summarizing the overall contamination status of soils by combining individual contamination factors (CFs) of multiple potentially toxic elements (PTEs) into a single value (26, 42). CFs are calculated as the ratio of measured concentrations in plants to corresponding soil concentrations or background levels, allowing identification of elements that contribute most to potential contamination or bioavailability. In this study, CFs were calculated using site-specific soil data from Ferralsols and Acrisols under four major crops (Oil Palm, Cacao, Cocoyam, and Maize) in Ghana, ensuring that PLI values reflect local baseline conditions and allow meaningful comparisons across crops and soil types.

The calculated PLI values in the present study ranged from 1.35×10⁻5 (Cocoyam in Acrisols) to 8.08×10⁻5 (Cacao in Ferralsols), indicating that all soils fall well within the “uncontaminated” category according to established thresholds (Table 8) (42). Ferralsols generally exhibited slightly higher PLI values than Acrisols for the same crop, reflecting differences in soil properties such as texture, organic matter content, and total element concentrations, which can influence the retention, mobility, and plant uptake of PTEs (8, 43). For instance, Maize in Ferralsols had a PLI of 4.08×10⁻5 compared to 1.65×10⁻5 in Acrisols, and Cocoyam in Ferralsols had a PLI of 4.09×10⁻5 compared to 1.35×10⁻5 in Acrisols.

Table 8. ANOVA and summary statistics of contamination factors (CFs) and soil pollution load index (PLI) for selected land use systems s in Ferralsols and Acrisols of Ghana.

Across all crops and soils, Cd and Zn consistently showed higher CFs relative to other elements, indicating that these elements are the main contributors to potential soil contamination and crop bioaccumulation. For example, CF(Cd) for Cacao in Ferralsols was 6.39×10⁻5 and CF(Zn) was 2.14×10⁻5, while for Oil Palm in Ferralsols, CF(Zn) reached 1.08×10⁻5. This trend aligns with tropical agricultural systems, where Cd and Zn accumulation can result from long-term fertilizer application, atmospheric deposition, or historical land management practices (43, 44). Other elements, including Mn, Cu, Al, Ti, and Ni, showed relatively low CFs (<3×10⁻4 in most cases), suggesting minimal anthropogenic enrichment and reflecting predominantly natural soil background levels. Acrisols, with higher aluminum and iron oxide content, may exhibit enhanced adsorption of Cd and Zn, effectively reducing their bioavailability and contributing to slightly lower PLI values despite similar total concentrations.

The statistical analysis supports these observations. ANOVA results for PLI and individual CFs indicated no statistically significant differences between Ferralsols and Acrisols for any of the crops studied (p > 0.05). Tukey HSD post-hoc tests further confirmed this, as all soil types were assigned the same letter, showing that differences in element uptake and PLI between soils are not significant. Thus, while Ferralsols often exhibited slightly higher mean CFs and PLI values, these differences do not represent significant deviations in contamination status.

Although all PLI values are far below thresholds indicating moderate or severe contamination, the relative prominence of Cd and Zn as dominant CF contributors warrants ongoing monitoring, particularly for perennial crops such as Cacao and Oil Palm, which can serve as long-term pathways for metal transfer into the food chain. These findings are consistent with previous studies in tropical soils of West Africa, where PLI values generally remain below 2, and Cd and Zn dominate soil contamination patterns due to agricultural inputs and land use history (19, 22)

The distribution of CFs across crops and soil types further illustrates the influence of soil properties on PTE bioavailability. For Oil Palm, Ferralsols showed higher CF(Zn) (1.08×10⁻5) compared to Acrisols (1.20×10⁻6), while CF(Cd) remained relatively low in both soils (≈1.8×10⁻5 in Ferralsols and 6.34×10⁻6 in Acrisols), suggesting that Acrisols’ higher aluminum and iron oxide content effectively limits Zn and Cd uptake. In Cacao, Ferralsols consistently exhibited higher CFs for all major PTEs, with CF(Cd) and CF(Zn) reaching 6.39×10⁻5 and 2.14×10⁻5, respectively, compared to Acrisols (CF(Cd) = 7.48×10⁻5; CF(Zn) = 3.98×10⁻5). Cocoyam displayed minimal differences between soil types, with PLI values of 4.09×10⁻5 in Ferralsols and 1.35×10⁻5 in Acrisols, reflecting low overall uptake and similar soil retention characteristics. Maize followed a similar pattern to Oil Palm, with Ferralsols showing higher CF(Mn), CF(Cu), and CF(Sr) compared to Acrisols, whereas Acrisols had slightly higher CF(Cd) (4.03×10⁻5) relative to other CFs, suggesting selective retention influenced by soil mineralogy.

These trends indicate that while overall soil contamination remains low, Ferralsols generally permit greater PTE uptake due to lower adsorption capacity, whereas Acrisols, enriched in Al and Fe oxides, reduce the mobility of key elements such as Cd and Zn. Across all crops, Cd and Zn consistently dominate the CF profile, emphasizing the need for monitoring and sustainable management practices in tropical agricultural soils to prevent long-term accumulation in edible plant part

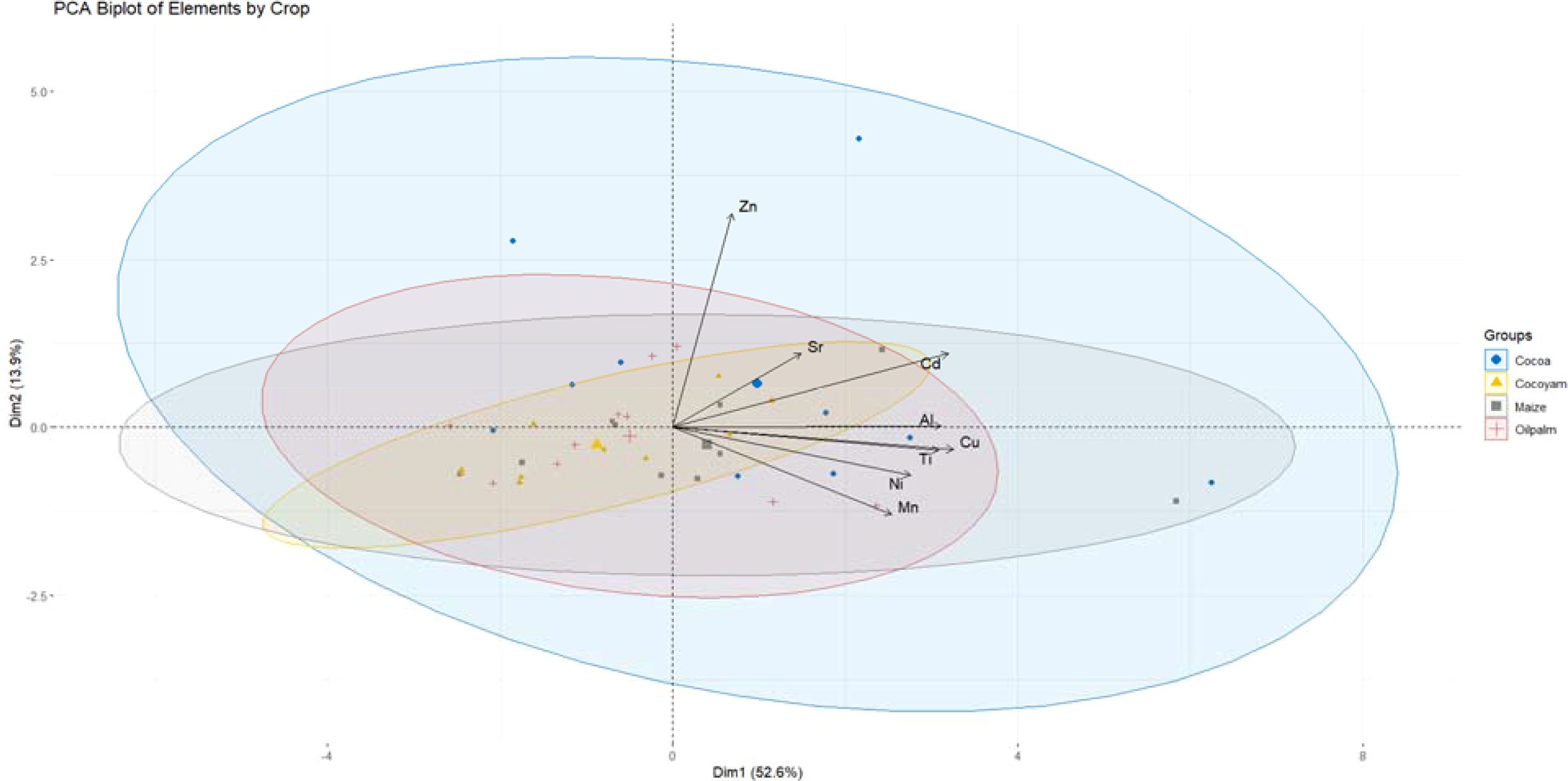

3.5 Relationships between soil fertility, bio-concentration and soil pollution load

The PCA biplot provides a multivariate visualization of the elemental profiles associated with four tropical crops: cacao, cocoyam, maize, and oil palm. The first two principal components (Dim1 and Dim2) explain a combined 59.6% of the total variance in the dataset (43.9% for Dim1 and 15.7% for Dim2), indicating that these two axes sufficiently summarize the major patterns in the elemental data (Figure 4).

The combined interpretation of Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and two-way ANOVA reveals distinct elemental signatures in soils influenced by different tropical cropping systems, namely cacao, oil palm, maize, and cocoyam. The PCA biplot, which accounted for 59.6% of the total variance (43.9% for Dim1 and 15.7% for Dim2), identified clear crop-based soil groupings with varying degrees of elemental differentiation. Oil palm soils demonstrated the widest spatial dispersion in the PCA space, indicating substantial heterogeneity likely caused by intensive nutrient cycling, fertilization, and organic matter turnover associated with oil palm’s extensive root systems and biomass production.

The PCA of selected elements (Al, Cd, Cu, Mn, Ni, Zn, Sr, and Ti) revealed distinct clustering patterns among soils under cacao, maize, oil palm, and cocoyam cultivation. Oil palm-associated soils dispersed broadly across the biplot, aligning with Sr and Zn, suggesting enrichment in these elements. This pattern indicates the contribution of organic residues and fertilization practices typical of oil palm systems, which can elevate Zn and Sr availability. These findings are consistent with earlier reports that link perennial plantation crops to increased micronutrient accumulation through both organic inputs and deep root cycling (45).

Cacao soils formed a more compact but directionally separated cluster, with strong associations to heavy metals including Cu, Ni, Mn, Cd, and Ti. This reflects the tendency of cacao systems to accumulate trace elements via agrochemical inputs (particularly Cu-based fungicides) and litterfall decomposition, as observed in Ghana and Peru (9). The high Mn and Ni loadings also suggest a geogenic influence, given the prevalence of ferralsols and acrisols in cacao-growing regions, which are naturally rich in sesquioxides.

Maize soils, while positioned closer to the plot origin, exhibited tendencies toward Al enrichment. This moderate elemental differentiation likely stems from the influence of parent material and intensive tillage practices that enhance Al mobilization in acidic tropical soils (46).

Cocoyam soils, represented by a tight ellipse near the center of the PCA, displayed minimal separation from other crops and weak associations with any particular element. This suggests elemental homogeneity and relative chemical stability under cocoyam cultivation, in line with studies reporting that cocoyam managed with organic amendments (e.g., biochar, poultry manure) improves soil quality without leading to significant trace metal accumulation (47).

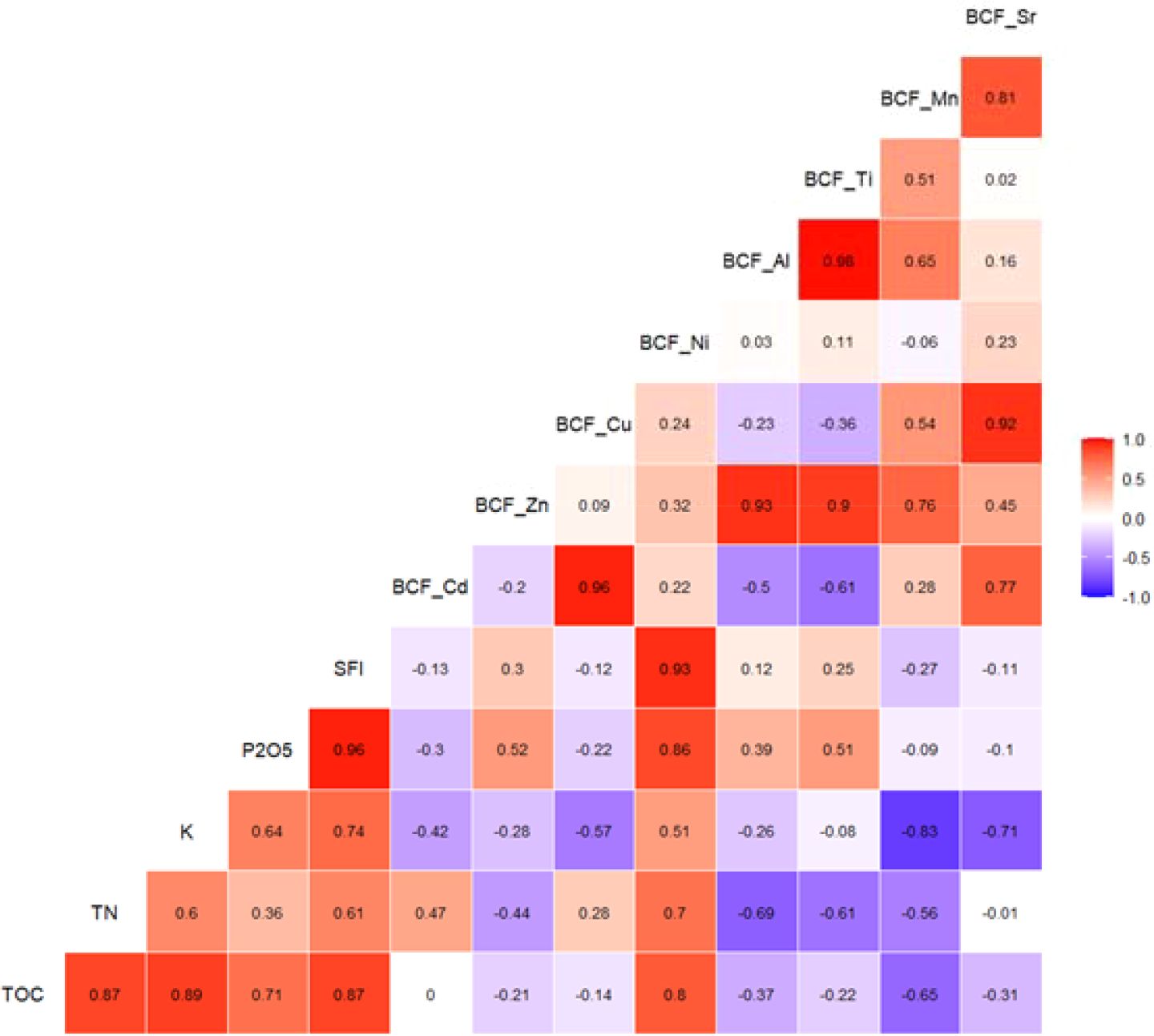

The correlogram (Figure 5) reveals insightful patterns in the relationships between the Soil Fertility Index (SFI), bioconcentration factors (BCFs) of selected trace metals, and key soil properties across four tropical crops. Notably, SFI exhibited a very strong positive correlation with BCF_Ni (r = 0.93), suggesting that higher soil fertility may enhance the uptake of Ni by plants. This could be attributed to increased root biomass and activity in fertile soils, which can enhance micronutrient uptake including Ni (8). Given that Ni is an essential element involved in urease activity and nitrogen metabolism in plants, its accumulation in more fertile systems may also reflect physiological demand (48).

Figure 5. Correlogram showing pairwise pearson correlations among soil fertility index, soil nutrients, and bioconcentration factors across all crop samples.

In contrast, SFI showed weaker or inconsistent correlations with BCFs of Cd (r = -0.14), Zn (r = 0.43), and Cu (r = 0.47), indicating that the uptake of these potentially toxic elements is less directly influenced by overall soil fertility, and more dependent on specific soil characteristics or crop traits. The weak Cd–SFI relationship aligns with findings by (49), who emphasized that Cd mobility and plant uptake are often governed by pH, competing cations, and organic ligands, rather than total fertility.

Interestingly, BCF_Cd and BCF_Cu were nearly perfectly correlated (r = 0.96) in the current dataset. This suggests that the accumulation patterns of these two elements may be tightly coupled, possibly due to shared transporters such as heavy metal ATPases or similar ionic radii and coordination chemistry (50). These elements may co-occur in soil solution or bind similarly to organic matter and mineral surfaces.

Likewise, BCF_Zn showed moderate to strong correlations with both BCF_Cd (r = 0.77) and BCF_Cu (r = 0.78). This pattern is consistent with prior studies indicating that Zn and Cd often compete for uptake sites, yet under certain conditions (e.g., high Zn concentrations), plants may absorb both metals simultaneously due to non-selective transporters (51).

Among soil properties, (TOC) and (TN) showed weak or inconsistent relationships with most BCFs. For example, TOC correlated weakly with BCF_Zn (r = 0.28) and was negatively associated with BCF_Cu (r = -0.53). This finding supports the idea that organic matter may sometimes immobilize trace metals by forming stable complexes, thereby reducing plant uptake (52), although the net effect varies depending on metal speciation and root exudation dynamics.

Finally, the tight clustering of BCF values for Sr, Mn, and Ti suggests potential covariation in plant uptake, possibly driven by similar geogenic sources or plant physiological pathways, particularly for Mn and Sr, which are known to interact with Ca²+ and redox-sensitive mechanisms (43).

Overall, these correlations reinforce the idea that plant uptake of trace elements is a multivariate process, influenced not only by bulk soil fertility but by specific chemical and biological interactions. Crop identity plays a central role, mediating uptake efficiency via root traits, transporter expression, and elemental demand, especially under tropical conditions where Fe/Al oxide interactions and low pH further complicate metal bioavailability (53).

While this study provides important insights into the interactions between soil properties, crop management, and trace element accumulation, some limitations should be acknowledged. The research was conducted in a single region of Western Ghana, which may limit the direct extrapolation of the results to other tropical soils and agricultural systems. In addition, only selected crops and cropping systems were examined, which may not capture the full diversity of tropical agriculture. Finally, the observational design restricts the ability to draw definitive causal relationships between soil characteristics, crop traits, and metal uptake. Nonetheless, the results offer valuable guidance for understanding nutrient and contaminant dynamics in tropical soils and for developing sustainable management practices in similar agroecosystems.

4 Conclusion

This study highlights that soil type and crop management exert significant influence on fertility, trace element bioaccumulation, and overall contamination in tropical agricultural systems of Western Ghana. Long-lived perennial crops, particularly cacao and oil palm, consistently exhibited higher soil fertility compared to short-cycle crops, reflecting greater organic matter input and nutrient retention. Soil fertility ranged from 0.41 ± 0.13 in maize under Ferralsols to 0.78 ± 0.26 in cacao under Acrisols, with corresponding total organic carbon and total nitrogen values of 21.63–24.36 g kg⁻¹ and 1.33–1.55 g kg⁻¹ in perennial crops, compared to 11.38 g kg⁻¹ and 1.06 g kg⁻¹ in maize. Cacao grown on Ferralsols displayed the highest bioconcentration factors for manganese, copper, and strontium, reflecting its greater capacity to accumulate both essential and potentially toxic elements, whereas maize and oil palm soils showed minimal accumulation. Despite uniformly low soil pollution load values (1.56×10⁻5–8.08×10⁻5), correlation analyses revealed complex interactions: soil fertility was strongly correlated with nickel uptake, while cadmium, copper, and zinc accumulation depended more on soil-specific properties than on overall fertility. Notably, the bioconcentration factors of cadmium and copper were highly correlated. Principal component analysis further distinguished crop-specific elemental patterns, with cacao soils enriched in copper, nickel, manganese, cadmium, titanium, oil palm soils in strontium and zinc, and maize and cocoyam soils showing weaker differentiation. Overall, these findings underscore that fertile soils do not necessarily equate to healthy soils, as root zones may still harbor excessive pollutant elements. The assimilation and accumulation of trace metals are governed more by plant-specific uptake and exclusion mechanisms than by soil fertility or contamination status. Future research should therefore focus on elucidating the ion selectivity and exclusion strategies of tropical crops and defining threshold concentrations of these elements in soil solution during uptake, to better safeguard food safety.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

ME: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AB: Supervision, Writing – review & editing. FK: Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This manuscript is the outcome of on-going research project entitled as Cadmium and Trace Elements Bioavailability and Transfer In Soil-Plant System (DUNE project) of DUNE and the authors are grateful to OCP-Nutricrop for their financial support.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Lal R. Soil science beyond COVID-19. J Soil Water Conserv. (2020) 75:113A–8A. doi: 10.2489/jswc.2020.0815A

2. Montanarella L, Pennock DJ, McKenzie N, et al. World’s soils are under threat. Soil. (2015) 1:79–82. doi: 10.5194/soil-1-79-2015

3. Sánchez PA. Soil fertility and hunger in Africa. Science. (2002) 295:2019–20. doi: 10.1126/science.1065256, PMID: 11896257

4. FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP and WHO. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2024 – Financing to End Hunger, Food Insecurity and Malnutrition in All Its Forms. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) (2024). doi: 10.4060/cd1254en

5. Ayegboyin KO and Akinrinde EA. Soil fertility status and nutrient management for sustainable crop production in selected soils of southwestern Nigeria. J Appl Agric Res. (2016) 8:81–92.

7. Van Wambeke A. Soils of the Tropics: Properties and Appraisal. FAO Soils Bulletin No. 66. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (1992).

8. Kabata-Pendias A. Trace elements in soils and plants (4th ed.). Boca Raton, FL, USA: CRC Press (2011).

9. Nagajyoti PC, Lee KD, and Sreekanth TVM. Heavy metals, occurrence and toxicity for plants: a review. Environ Chem Lett. (2010) 8:199–216. doi: 10.1007/s10311-010-0297-8

10. Henao J and Baanante C. Agricultural production and soil nutrient mining in Africa: Implications for resource conservation and policy development. Muscle Shoals, AL: International Fertilizer Development Center (IFDC (2006).

11. Papadopoulos A and Rowell DL. The phosphate status of soils and its evaluation. Mineral components Soil. (1989), 561–92.

12. Mellouki ME, Boularbah A, Frimpong KA, and Kebede F. Portable X-ray fluorescence (PXRF) application for plant nutrition analysis and environmental hazard evaluation in tropical environment. J Plant Nutr. (2025) 48:2295–23155. doi: 10.1080/01904167.2025.2476635

13. IUSS Working Group WRB. World Reference Base for Soil Resources 2022: International soil classification system for naming soils and creating legends for soil maps (update 2022). World Soil Resour Rep No. 202. (2022).

14. Ahenkorah B, Halm BJ, Appiah MR, Akrofi GS, and Yirenkyi JEK. Twenty Years ‘ Results From A Shade And Fertilizer Trial On Amazon Cocoa {Theobroma Cacao) (1987). New Tafo-Akim, Ghana: Ghana Cocoa Research Institute of Ghana (CRIG), PO Box 8. ) Following the Success of the Earlier Amelonado Co.

15. Asubonteng KO, Ros-Tonen MAF, Baud I, and Pfeffer K. Envisioning the future of mosaic landscapes: actor perceptions in a mixed cocoa/oil-palm area in Ghana. Environ Manage. (2021) 68:701–195. doi: 10.1007/s00267-020-01368-4, PMID: 33057799

16. Adjei-Nsiah S, Sakyi-Dawson O, and Kuyper TW. Exploring opportunities for enhancing innovation in agriculture: the case of oil palm production in Ghana. J Agric Sci. (2012) 4. doi: 10.5539/jas.v4n10p212

17. Abdulai S, Nkegbe PK, and Donkor SA. Assessing the economic efficiency of maize production in Northern Ghana. Ghana J Dev Stud. (2017) 14:1235. doi: 10.4314/gjds.v14i1.7

18. Smolders E, Wagner S, Prohaska T, Irrgeher J, and Santner J. Sub-millimeter distribution of labile trace element fluxes in the rhizosphere explains differential effects of soil liming on cadmium and zinc uptake in maize. Sci Total Environ. (2020) 738. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140311, PMID: 32806385

19. Essumang DK, Dodoo DK, Obiri S, and Yaney JY. Arsenic, cadmium, and mercury in cocoyam (Xanthosoma sagititolium) and watercocoyam (Colocasia esculenta) in tarkwa a mining community. Bull Environ Contamination Toxicol. (2007) 79:377–79. doi: 10.1007/s00128-007-9244-1, PMID: 17673943

20. Bansah KJ and Addo WK. Phytoremediation potential of plants grown on reclaimed spoil lands. Ghana Min J. (2016) 16:685. doi: 10.4314/gmj.v16i1.8

21. AFNOR. Qualité des sols – Mesurage des propriétés physiques et chimiques des sols – Méthodes d’analyse (Norme NF X 31-107). Paris: Association Française de Normalisation (2002).

22. Mellouki ME, Boularbah A, and Kebede F. Quantitative evaluation of potentially toxic elements and associated risks in acrisols and ferralsols of Western Ghana. Front Soil Sci. (2025) 5:1638448. doi: 10.3389/fsoil.2025.1638448

23. Shi C, Li J, Wang Y, and Ge L. Investigation on soil fertility of newly increased cultivated land after wasteland improvement in loess hilly region-a case study in ganquan county, Shaanxi Province. IOP Conf Series: Materials Sci Eng. (2018) 394. doi: 10.1088/1757-899X/394/5/052044

24. Bagherzadeh A, Gholizadeh A, and Keshavarzi A. Assessment of soil fertility index for potato production using integrated fuzzy and AHP approaches, Northeast of Iran. Eurasian J Soil Sci. (2018) 7:203–125. doi: 10.18393/ejss.399775

25. Kabata A. Trace Elements In Soils And Plants Third Edition. Trace Elements in Soils and Plant. Boca Raton, Florida, USA: CRC Press (1992).

26. Tomlinson DL, Wilson JG, Harris CR, and Jeffrey DW. Problems in the assessment of heavy-metal levels in estuaries and the formation of a pollution index. Helgoländer Meeresuntersuchungen. (1980) 33:566–75. doi: 10.1007/BF02414780

27. R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing (2023). Available online at: https://www.R-project.org/.

28. Isaac ME and Anglaaere LCN. An in situ approach to detect tree root ecology: Linking ground penetrating radar imaging to isotope derived water acquisition zones. Ecology & Evolution. (2013) 3:1330–9. doi: 10.1002/ece3.543, PMID: 23762519

29. Schroth G and Sinclair FL. Trees, crops, and soil fertility: Concepts and research methods. Wallingford, UK: CABI Publishing (2003).

30. Lal R. Soil carbon sequestration impacts on global climate change and food security. Science. (2005) 304:1623–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1097396, PMID: 15192216

31. Six J, Conant RT, Paul EA, and Paustian K. Stabilization mechanisms of soil organic matter: Implications for C-saturation of soils. Plant Soil. (2002) 241:155–76. doi: 10.1023/A:1016125726789

33. Tadesse B, Atlabachew M, and Mekonnen KN. Concentration levels of selected essential and toxic metals in potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) of West Gojjam, Amhara Region, Ethiopia. SpringerPlus. (2015) 4. doi: 10.1186/s40064-015-1301-3, PMID: 26405634

34. Lal R and Stewart BA. Food Security and Soil Quality 11. . Boca Raton: CRC Press (2010). Edited by 416. doi: 10.1016/j.regsciurbeco.2008.06.005%0Ahttps://www.researchgate.net/publication/305320484_SISTEM_PEMBETUNGAN_TERPUSAT_STRATEGI_MELESTARI

35. Fosu-Mensah BY, Addae E, Yirenya-Tawiah D, and Nyame F. Heavy metals concentration and distribution in soils and vegetation at korle lagoon area in Accra, Ghana. Cogent Environ Sci. (2017) 3. doi: 10.1080/23311843.2017.1405887

36. Aikpokpodion PE, Lajide L, Ogunlade MO, Ipinmoroti R, Orisajo S, Iloyanomon CI, et al. Degradation and residual effects of endosulfan on soil chemical properties and root knot nematode (Meloidogyne incognita) populations in cocoa plantation in Ibadan, Nigeria. J Appl Biosci. (2010) 26:1640–6.

37. Wade J, Ac Pangan M, Favoretto VR, Taylor AJ, Engeseth N, and Margenot AJ. Drivers of cadmium accumulation in Theobroma cacao L. beans: A quantitative synthesis of soil plant relationships across the Cacao Belt. PLoS One. (2022) 17:e0261989. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0261989, PMID: 35108270

38. Weggler-Beaton K, McLaughlin MJ, and Graham RD. Salinity increases cadmium uptake by wheat and swiss chard from soil amended with biosolids. Aust J Soil Res. (2000) 38:37–45. doi: 10.1071/SR99028

39. Adjei Nsiah S, Kumah JF, Owusu Bennoah E, and Kanampiu F. ) Influence of P sources and Rhizobium inoculation on growth and yield of soybean genotypes on Ferric Lixisols of Northern Guinea Savanna Zone of Ghana. Commun Soil Sci Plant Anal. (2019) 50:853–68. doi: 10.1080/00103624.2019.1589489

40. Letort F, Chavez E, Cesaroni C, Castillo-Michel H, and Sarret G. Cadmium and other metallic contaminants in cacao: update on current knowledge and mitigation strategies. OCL - Oilseeds Fats Crops Lipids. (2025) 32. doi: 10.1051/ocl/2025019

41. Liu K, Liu H, Zhou X, Chen Z, and Wang X. Cadmium uptake and translocation by potato in acid and calcareous soils. Bull Environ Contamination Toxicol. (2021) 107:1149–545. doi: 10.1007/s00128-021-03377-3, PMID: 34562128

42. Hakanson L. An ecological risk index for aquatic pollution control.a sedimentological approach. Water Res. (1980) 14:975–1001. doi: 10.1016/0043-1354(80)90143-8

43. Alloway BJ. Heavy Metals in Soils: Trace Metals and Metalloids in Soils and Their Bioavailability (3rd ed.). Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer (2013).

45. Haryuni AK, Widijanto H, and Supriyadi. Soil fertility index on various rice field management systems in Central Java, Indonesia. Am J Agric Biol Sci. (2020) 15:75–825. doi: 10.3844/ajabssp.2020.75.82

46. Rosenstock TS, Tully KL, Arias-Navarro C, Neufeldt H, Butterbach-Bahl K, and Verchot LV. Agroforestry with N2-fixing trees: sustainable development’s friend or foe? Curr Opin Environ Sustainability. (2014) 6:15–21. doi: 10.1016/j.cosust.2013.09.001

47. Sheoran V, Sheoran AS, and Poonia P. Factors affecting phytoextraction: A review. Pedosphere. (2016) 26:148–665. doi: 10.1016/S1002-0160(15)60032-7

48. Wan W, Tan J, Wang Y, Qin Y, He H, Wu H, et al. Responses of the rhizosphere bacterial community in acidic crop soil to PH: changes in diversity, composition, interaction, and function. Sci Total Environ. (2020) 700:134418. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.134418, PMID: 31629269

49. Smolders E and Mertens J. Cadmium. (2013). pp. 283–311. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-4470-7_10.

50. Clemens S. Toxic metal accumulation, responses to exposure and mechanisms of tolerance in plants. Biochimie. (2006) 88:1707–19. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2006.07.003, PMID: 16914250

51. Lux A, Martinka M, Vaculík M, and White PJ. Root responses to cadmium in the rhizosphere: A review. J Exp Bot. (2011) 62:21–375. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erq281, PMID: 20855455

52. Holm PE, Rootzé H, Borggaard OK, Møberg JP, and Christensen TH. Correlation of Cadmium Distribution Coefficients to Soil Characteristics. Madison, WI, USA: American Society of Agronomy / Soil Science Society of America / Crop Science Society of America (2003). doi: 10.2134/jeq2003.1380., PMID: 12549552

Keywords: cacao, cocoyam, oil palm, maize, ion uptake, soil properties, pollutant elements, Ferralsols

Citation: El Mellouki M, Boularbah A and Kebede F (2025) The nexus of soil fertility, bioconcentration and soil pollution load in the tropical land use systems of Western Ghana. Front. Soil Sci. 5:1703751. doi: 10.3389/fsoil.2025.1703751

Received: 11 September 2025; Accepted: 27 October 2025;

Published: 25 November 2025.

Edited by:

Huu Tuan Tran, Văn Lang University, VietnamReviewed by:

Raimundo Jimenez Ballesta, Autonomous University of Madrid, SpainJuan Manuel Trujillo-González, University of the Llanos, Colombia

Copyright © 2025 El Mellouki, Boularbah and Kebede. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Meryem El Mellouki, TWVyeWVtLmVsbWVsbG91a2lAdW02cC5tYQ==

Meryem El Mellouki

Meryem El Mellouki Ali Boularbah

Ali Boularbah Fassil Kebede

Fassil Kebede