- 1Graduate School of Science and Technology, University of Tsukuba, Tsukuba, Japan

- 2Research Fellow of Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, Tokyo, Japan

- 3Institute for Geoinformatics, University of Münster, Münster, Germany

- 4Institute of Systems and Information Engineering, University of Tsukuba, Tsukuba, Japan

Introduction: Observers in public display environments often follow the gaze and body orientation of nearby pedestrians—a phenomenon termed the “honey-pot effect”—thereby increasing overall attention to the screen. While prior research has demonstrated this effect for interactive installations, its applicability to passive, non-interactive content and its impact on subsequent content recognition remain unexplored. This study employed a virtual-reality simulation of an urban sidewalk, featuring a moving avatar and a stationary digital display, to investigate whether simple head-and-body orientations by one pedestrian can direct attention and enhance content awareness among following pedestrians.

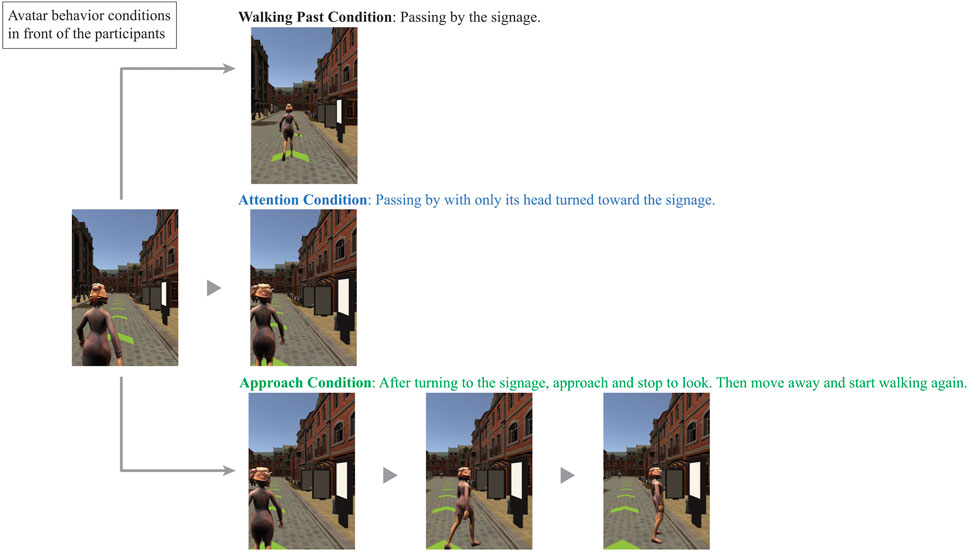

Methods: We conducted an experiment where an avatar walked behind another avatar passing in front of public display on a virtual sidewalk. The avatar’s behavior was set to three conditions: Walking past, Attention, and Approach to the public display.

Results: The results of the experiment with 18 participants showed that participants were more likely to turn and look at the display influenced by the avatar in front approached and stopped in front of the display. Likewise, when a pedestrian approaching from the opposite direction—whose face was visible—turned toward the display, participants were similarly more inclined to turn and look. However, no effect was observed on participants’ recognition of the content. Among the participants, which included eight Germans and eight Japanese, there was no difference in how easily the reaction to the behavior of other pedestrians occurred.

Discussions: These findings suggest that, even for static display content, attracting the “first pedestrian“ through visually striking designs or the use of sound can be critical. Besides, it is important not only to consider display content but also to take into account pedestrian walking directions when placing displays, so that more people will be encouraged to notice and view the content.

1 Introduction

When walking in public spaces, we are exposed to a wide variety of information, ranging from local transportation guides to advertisements. Information providers employ various strategies to make their displays stand out as much as possible, thereby enhancing their effectiveness. Previous studies have shown that pedestrians’ attention to public displays is strongly influenced by factors such as the content, placement, visual characteristics, and interactivity of the display Huang et al. (2008); Müller et al. (2009); Alt et al. (2021). For instance, the research Müller and Krüger (2009); Kukka et al. (2013) reported that vivid colors and dynamic presentations using video attract more pedestrian attention. Moreover, rather than merely disseminating information in a one-way manner, numerous studies have examined methods to prolong pedestrian dwell time by encouraging interaction Vogel and Balakrishnan (2004); Rodriguez and Marquardt (2017); Tafreshi et al. (2018); Walter et al. (2014).

From the pedestrian’s perspective, however, public displays often do not stand out enough and tend to be overlooked. This phenomenon is known as display blindness Müller et al. (2009). The staged behaviors of passersby in front of a display—from before any interaction begins to after the interaction has ended and the individual departs—are referred to as the audience funnel Müller et al. (2010); Michelis and Müller (2011). This audience funnel comprises the sequential phases of passing-by, viewing and reacting, subtle interaction, direct interaction, multiple interaction, and follow up actions. Many interactive signage designs seek to attract or retain viewers by following this audience funnel framework Sahibzada et al. (2017); Alt et al. (2021); Limerick (2020). According to this model, display blindness stems from insufficient initial “awareness.” Therefore, utilizing others’ actions and social cues may be effective in alerting pedestrians. To address this issue, a number of researchers have devised different approaches.

One such approach is to present interactive content Vogel and Balakrishnan (2004); Rodriguez and Marquardt (2017); Tafreshi et al. (2018); Walter et al. (2014). For pedestrians, this interactivity provides a clear reason to pay attention to the display, often causing them to stop and engage with gestures, thus extending their dwell time. Moreover, even those simply passing by may notice people making gestures and become curious about what is happening. This influenced reaction—where people notice someone already looking at the display and are thereby prompted to look themselves—is known as the honey-pot effect Brignull and Rogers (2003). The honeypot effect increases attention to the display, creating an interaction among three individuals: the display, the pedestrian viewing the display, and other pedestrians. The crucial element here is the “pedestrian viewing the display,” who mediates this three-way interaction. Without this mediator, the honeypot effect does not occur. A similar social behavior is known as joint attention. Joint attention refers to the process by which individuals share attention through gaze. By eliciting joint attention, it becomes possible to understand each other’s intentions Kaplan and Hafner (2006), share experiences Christidou (2018); Aoyagi et al. (2023), and facilitate smooth engagement in interaction Huang and Thomaz (2010); Schnier et al. (2011). Systems have been designed to deliberately prompt the occurrence of joint attention, and once joint attention is established, the sustained gaze further conveys intentions between individuals. In contrast, in the honey-pot effect—a three-way relationship involving a display—the pedestrian merely imitates the actions of another pedestrian, without reaching an understanding of interpersonal intent. In other words, the presence of the pedestrian stopping in front of public displays is crucial for drawing the attention of other pedestrian. By presenting interactive content, it encourages others to engage in attention-seeking behavior, which in turn triggers new attention Müller et al. (2009).

However, not all display content is necessarily interactive. In light of costs and equipment constraints, many public displays simply show static images or videos, which are widely used in practice Huang et al. (2008). In such cases, display blindness is more likely to occur, and the display is more easily overlooked. Consequently, there are no pedestrians viewing the display, and the honeypot effect fails to emerge. In contrast, in virtual reality (VR) environments, it is often difficult to determine whether avatars are controlled by real users or computer algorithms based solely on their visual appearance. Nonetheless, studies have shown that the gaze direction, proximity, and non-verbal behaviors of virtual agents can significantly influence users’ attention and spatial perception Schott et al. (2025); Nelson et al. (2024). Research indicates that users respond sensitively to avatar gaze even when facial detail is minimal, and that proximity and gestural cues can modulate spatial awareness. Furthermore, emotional engagement and the sense of presence in VR are closely linked, suggesting that socially expressive avatars can enhance both attentional and affective responses Riva et al. (2007). Taken together, these findings suggest that avatars can be purposefully designed to simulate the role of “pedestrians viewing the display,” thereby serving as salient social cues within the VR space. In this context, a controlled pedestrian avatar may act as a mediator, facilitating a honeypot effect between the display and the participant.

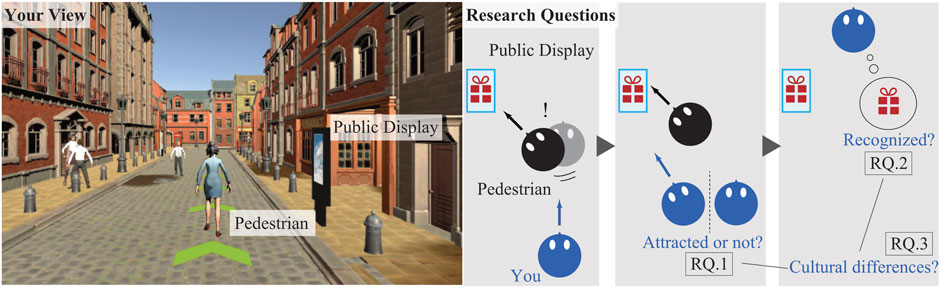

Therefore, this study examines the relationship between avatar-mediated social attention and the honeypot effect in VR environments. Furthermore, it investigates whether the avatar-mediated honeypot effect influences not only attention to the display but also the recognition of presented content. Thus, as shown in Figure 1, this paper addresses the following three research questions:

• RQ.1: Does the behavior of a pedestrian in front of the display influence the behavior of the pedestrian behind them?

• RQ.2: If the follower’s behavior is affected, does this influence their recognition of the display content?

Figure 1. The research questions are followings: (1) Does the behavior of a pedestrian in front of the display influence the behavior of the pedestrian behind them?, (2) If the follower’s behavior is affected, does this influence their recognition of the display content?, and (3) Do Germans and Japanese differ in how frequently they are drawn to look when the person in front turns toward the display? These are answered by conducting experiments with 18 participants.

Additionally, differences in nationality or culture may also influence such behaviors. For example, with regard to interpersonal distance, Asian individuals have been reported to maintain larger personal space compared to Europeans Hasler and Friedman (2025). Eye contact norms can likewise vary: in Germany, making eye contact is considered polite, while in Japan it can sometimes be perceived as a sign of anger Akechi et al. (2013); Sicorello et al. (2019). As these examples suggest, one person’s action may trigger changes in another person’s behavior, such as stepping back when someone gets too close or looking away when eye contact is established. In urban environments, such scenarios hint at how one’s behavior can change in response to observing someone else’s behavior. Therefore, to explore whether there is a difference in how people from different cultures react to another person turning toward a public display, we conducted experiments in both Germany and Japan and report the differences.

• RQ.3: Do Germans and Japanese differ in how frequently they are drawn to look when the person in front turns toward the display?

Previous studies on non-interactive public displays have largely focused on one-to-one interactions between the pedestrian already standing in front of the display and the display itself. This is because display blindness in the real world cannot be ignored, making the honeypot effect less likely to occur. This study extends these questions to a three-party relationship connecting pedestrians and non-interactive displays via controlled avatars, providing insights into the honeypot effect within VR spaces. If the honeypot effect—where attention heightens and recognition improves due to others’ actions, even without interactive mechanisms—is confirmed, it could demonstrate unique possibilities for display utilization within VR spaces. Furthermore, this study is based on previous research Kuratomo et al. (2025) that investigated, on a small scale, whether the behavior of avatars influences the recognition of displays. This study further extends this by examining recognition of content and cultural differences as well.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Experimental environment

In order to examine whether an individual’s response to a public display can influence the behavior of surrounding pedestrians, we constructed an experimental environment that recreates a city street in virtual space (Figure 1). The experimental setup was informed by the public-display implications identified by Mäkelä et al. (2020), such that participants were immersed in a naturalistic scenario and the environment did not contradict the behaviors we aimed to measure. The detailed design is as follows. The environment simulates a typical sidewalk during daytime, featuring bright lighting settings and low-volume ambient sound. Buildings and streetlights are placed on both sides of the street, and multiple pedestrian avatars are randomly arranged on the road and walkways. Although the placement of some buildings was unintentionally altered due to a software issue during the process, the change was minimal and had few impacts on the experimental environment. There are approximately ten avatars in total, each programmed with predefined behaviors such as walking, stopping, and chatting with other avatars.

Participants wore an HTC Vive headset and walked within this VR environment developed in Unity. For locomotion, they used a handheld controller. To mitigate VR motion sickness, the visual field did not move continuously. Instead, pressing and holding a controller button initiated incremental transitions. The ground displayed arrows indicating the walking route, guiding participants from the starting point to a goal (marked by a dead-end sign). Participants were allowed to stop, look around freely, and were given a practice session in a sample environment before starting, ensuring they became familiar with movement and viewpoint operations.

The focus of this research is on how avatar behaviors affect participants walking behind or approaching from the opposite direction. In this study, the independent variables are the behavior and walking direction of an avatar preceding the participant, while the dependent variable is the participant’s own behavior. Three behavioral conditions were implemented for the avatar:

• Walking Past: Walking past by the display without paying attention.

• Attention: Turn briefly toward the display and pay temporary attention.

• Approach: Move closer to the display, stop there to view the advertisement, and then walk away.

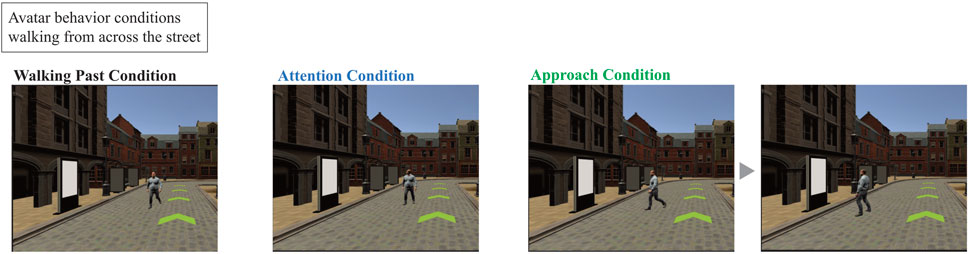

The Approach condition was designed by referencing the audience funnel Müller et al. (2010), Michelis and Müller (2011). For the Attention condition, the avatar did not approach the display but rotated its head to face the screen while passing. Regarding walking direction, we employed two patterns: an avatar walking in the same direction as the participant (see Figure 2) and an avatar walking from the opposite direction (see Figure 3). Two avatars performed each behavior simultaneously in each trial. The duration for which the avatar turns toward the display and the time spent stopping to look are fixed.

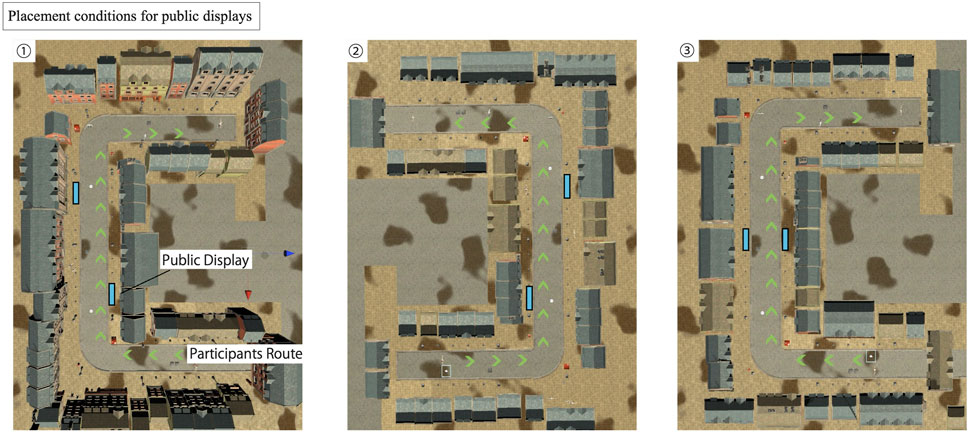

To ensure that display placement did not itself influence participant behavior, three signage-location patterns were used, as indicated in Figure 4 (e.g., (1) one on the right front and one on the left rear, and (2) one on the right rear and one on the left front, and (3) two displays in the central area). Each of the three avatar-behavior conditions was randomly paired with one of these signage-placement patterns.

Figure 4. Three conditions of the signage placement: The location of the display and the pedestrian trajectory are overlaid for ease of viewing in the figure.

The displays presented static-image advertisements. Six different images—contact lenses, detergent, salad, airplane, tom yum goong, and champagne—were sourced via a subscription from the site fre (Last access: 4 September 2025). No participant encountered the same advertisement more than once.

For data collection, we projected participants’ VR view onto a monitor and recorded it using a GoPro camera. This allowed us to capture the orientation of the headset and a general sense of each participant’s field of view, without including personal identifiable information (e.g., faces or body images).

2.2 Participants

The recruitment period for participants in Germany was from January 19 to 11 March 2023, and in Japan from February 5 to 29, 2024. A total of 18 individuals took part in the study: 9 residing in Germany and 9 residing in Japan. Of these, 8 were German (five males and three females), 8 were Japanese (six males and two females), 1 was American (female), and 1 was Chinese (male), with an average age of 24.39

Participants in Germany were recruited through a publicly posted call for participation on the bulletin board of the authors’ institution, and all nine volunteers who responded took part in the experiment. In Japan, recruitment was carried out via an email announcement within the authors’ institution, and all nine respondents participated. During recruitment, we asked for individuals with normal or corrected-to-normal vision and hearing. No additional screening was conducted. Furthermore, participants were not asked about their VR experience.

2.3 Experimental procedure

Prior to the experiment, participants were given a brief overview of the procedure and signed a paper-based informed consent form. To avoid revealing the specific focus of the study, it was described as a “walking behavior experiment,” with further details provided during debriefing. This research received approval from the ethics committee at the authors’ institution. Participants were compensated based on minimum wage rates in each country: 10 euros in Germany and 690 yen in Japan. The only requirement for participation was normal visual and auditory ability.

Participants began with a practice session in the VR environment, learning how to move around and confirm the route to be followed. The practice used a simple street environment and lasted about 3 min, with green arrows indicating the path. Two public displays were also placed in this practice environment. After the practice, participants performed three main trials, with a short break between each trial to reduce VR motion sickness. All three conditions—Walking Past, Attention, and Approach—were experienced, but display placement patterns and the order in which participants encountered each condition were randomized.

During each main trial, participants wore a VR headset, headphones, and used a controller to navigate the virtual street. Pressing and holding a controller button allowed movement along the green arrows. Releasing the button brought them to a stop, and they could rotate their head to look around. The length of time spent stopping or looking around was left up to the participants. Movement beyond the specified route was restricted. Each trial ended when participants reached a “Dead End” sign, at which point they removed the headset and took a break.

After completing all trials, participants answered a questionnaire. They were asked whether they noticed the displays or their content, what content they recalled, and to what extent they believed they were influenced by the avatars’ behaviors. A free-response section allowed them to share overall impressions across the three trials. The full questionnaire is provided in the Supplementary Material.

Each trial took approximately 3 min. Including preparation, practice, breaks, and questionnaire responses, each participant required about 45 min in total to complete the session.

3 Results

3.1 Head-turning toward the display

This section addresses RQ.1: does the behavior of a pedestrian in front of the display influence the behavior of the pedestrian behind them?

First, based on the recorded video data, we defined head-turning as follows: when the avatar walking ahead turned toward the display or approached it, any subsequent head turn by the participant toward the display was considered a “head-turning event.” In the Walking Past condition, by contrast, we simply noted whether the participant looked at the display. These events were identified by experimenters reviewing the video footage and determining whether the participant’s viewpoint clearly shifted toward the signage. While we did not perform frame-by-frame quantitative angle analysis or discrimination based on fixation duration, this operational definition allowed us to consistently distinguish intentional orienting responses from small posture adjustments. There were 18 participants and two displays, so the data count in each of the Walking Past, Attention, and Approach conditions was

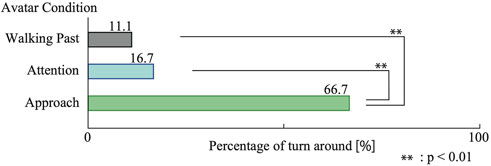

As shown in Figure 5, head-turning occurred in 11.1% (4 instances) of the Walking Past trials, 16.7% (6 instances) of the Attention trials, and 66.7% (24 instances) of the Approach trials. A Kruskal–Wallis test on the number of head-turns revealed a significant difference at the 1% level (

Figure 5. Proportions of head-turning under three avatar behavior conditions. A Kruskal–Wallis test showed a significant difference among conditions (

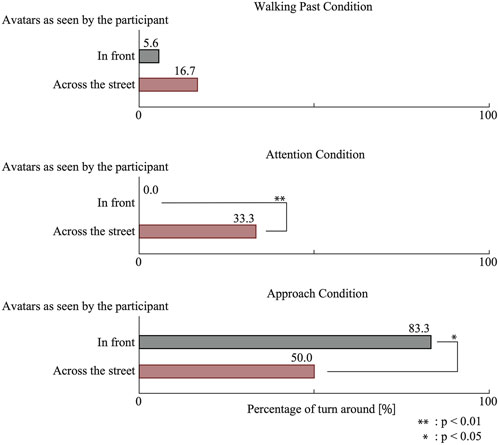

Next, we analyzed the difference between an avatar walking in the same direction versus one approaching from the opposite direction (Figure 6). Each case had a data count of

Figure 6. Head-turning rates compared between avatars walking ahead and approaching from the opposite direction. Wilcoxon rank-sum tests showed no significant difference in the Walking Past condition

3.2 Ad recognition

Next, to determine whether participants who turned their heads due to avatar behavior were aware of the advertisements shown on the display, a questionnaire was administered asking them to describe the content they saw (see Appendix). We focused on the individuals influenced by the avatar’s actions – 3 in the Walking Past condition, 6 in the Attention condition, and 15 in the Approach condition–and compared how accurately they recalled the ads.

In the Walking Past condition, none of the 3 participants answered correctly (0.0%). In the Attention condition, 2 out of 6 (33.3%) gave the right answer. In the Approach condition, 7 out of 15 (46.7%) answered correctly. Those who responded accurately could only recall one of the two displays. A Kruskal–Wallis test did not reveal a meaningful difference among these groups (

3.3 Differences by nationality

Because most participants were either German or Japanese, we examined whether there was a difference in their propensity to turn toward the display. For this cultural comparison, the analysis included eight German participants and eight Japanese participants; one participant each from the United States and China were excluded to avoid confounding effects of different cultural backgrounds. We combined the data from the Walking Past, Attention, and Approach conditions, resulting in

3.4 Participant comments

Below are comments from the questionnaire item, “Why did you look at the display?” In the Walking Past condition, no participant cited the walking avatar as a reason for looking at the display. In the Attention condition, however, one participant (P12) noted, “Because the person passing by glanced at it repeatedly,” indicating that an avatar coming from the opposite direction influenced them to turn. In the Approach condition, multiple participants (P2, 11, 12, 13, 14, 16, 18) gave responses along the lines of, “Since a passerby stopped to look at the display, I also paid attention to it.”

4 Discussion

4.1 Answer to RQ.1 - content design of public display

Based on the three research questions posed at the start of this study, this chapter discusses answers to each question in light of the experimental results.

First, regarding RQ.1—“Does the behavior of a pedestrian in front of the display influence the behavior of the pedestrian behind them?”—the results in Section 4.1 indicate that, under certain conditions, a pedestrian behind can indeed be influenced by the pedestrian in front. Specifically, in the Approach condition, where the avatar in front draws closer to and stops at the display, the frequency with which the participant behind turns toward the display increases, regardless of the avatar’s walking direction. One participant (P11) commented, “Since the person walking in front looked at the public display, I also turned my attention to it.” From these observations, it appears that when the pedestrian in front transitions from a simple walking state to a different state (in this case, walking up to the display and stopping to look), the person behind is more likely to follow suit.

In contrast, when the avatar in front remains in motion but simply turns its head to look at the display while walking, participants were more likely to mimic that head turn if they could see the avatar’s face (i.e., when it was walking in the opposite direction). The fact that participants were less influenced by an avatar in front whose head and face were not visible (i.e., only its back was seen) further suggests that for a walking pedestrian, the “turning one’s head” action tends to draw attention only when the other person’s face is visible.

From these findings, the answer to RQ.1 can be summarized as follows: When the pedestrian in front fully shifts their body toward the display and approaches it, those behind are more inclined to be drawn to it as well. - If the person in front remains in a walking state but turns their head, the one behind is more likely to be influenced if they can see the front pedestrian’s face.

Taken together, these results indicate that a controlled avatar can indeed act as an intermediary in the honey-pot effect within VR environments. In the Approach condition, the avatar’s act of stopping in front of the display reliably attracted the follower’s attention, functioning much like a “first viewer” would in real public spaces. In contrast, the Attention condition produced more mixed outcomes: some participants followed the avatar’s cue while others did not. This pattern suggests that people’s perceptual reactions depend strongly on whether the avatar’s behavior conveys a clear sense of gaze direction. Importantly, the effectiveness of these cues did not require the gaze to be produced by a real person; computer-controlled gaze shifts were sufficient to trigger attentional responses, consistent with previous findings that sudden changes in others’ gaze can draw observers’ attention. In this respect, users in VR appear to respond to an avatar’s walking behavior and gaze cues in ways that closely resemble reactions to real pedestrians in physical environments.

Furthermore, the fact that approach actions were fewer than attention actions also mirrors reality. For the participants behind the avatars, actions of approach or attention conditions and were sudden movements, causing some participants to interrupt their goal-directed actions prompted by the prior instruction to “head toward the goal.” This is also demonstrated in the literature Petersen and Posner (2012); Corbetta and Shulman (2002) and can be considered “bottom-up” attention control. However, participants did not progress to actions like stopping to look, failing to reach “goal-driven” cognition. In reality, few people progress from noticing an advertisement to cognition Parra et al. (2014); Sahibzada et al. (2017), and this study shows that transitioning to goal-driven behavior is also difficult in VR.

This conclusion can inform the development of public display content that takes pedestrian behavior patterns into account. For instance, if a display emits sound to catch someone’s eye, using a directional speaker aimed at a specific individual—rather than broadcasting sound to everyone—might also attract attention from the oncoming pedestrian. Moreover, content that encourages gestures can cause a pedestrian to change their walking state, thereby triggering a honey-pot effect that draws attention from other passersby Brignull and Rogers (2003); Parra et al. (2014); Veenstra et al. (2015). Furthermore, by placing an avatar that appears to be operated by a person in front of the display and moving its gaze, the display’s effect extends to the avatar’s position.

4.2 Answer to RQ.2 - content recallability

In this section, we address RQ.2: “If the follower’s behavior is affected, does this influence their recognition of the display content?”

From the results on ad recognition among participants who did look at the display, it became evident that the content is not necessarily retained. Our analysis, which focused on whether those who turned their heads due to an avatar’s behavior could recall the ad, revealed a low rate of accurate memory for all avatar behavior conditions, with no significant difference observed

In particular, in the Attention condition, 2 out of 6 individuals (33.3%) correctly identified the ad content, and in the Approach condition, 7 out of 15 (46.7%) did so, but this difference was not statistically significant. Most of those who turned to look spent only about one or 2 seconds viewing the ad, indicating that such a brief period is unlikely to suffice for fully encoding the content. In other words, a single glance may not lead to short-term memory formation.

Nevertheless, it is not impossible for brief exposure to yield some recall. For instance, one participant (P9) commented, “I am flying soon so I noticed an airplane,” referring to an advertisement featuring an airplane illustration. This indicates that ads personally relevant to a pedestrian may be recognized even in a short time. In real-world advertisements, it has been reported that ads relevant to individuals are more likely to attract attention Kaspar et al. (2019), and this has been confirmed to hold true in VR as well. However, this pertains only to the stage of attention and cognition, and does not delve into how the ads are ultimately perceived. Furthermore, increasing the volume or using overly vivid colors to attract attention could overwhelm the surrounding environment with noise; hence, it is essential to consider harmony with the environment.

Taking these findings into account, the answer to RQ.2 is that, although pedestrians who turn their heads are momentarily drawn to the display content, they typically pay attention for only a very short time while walking, making it less likely that they will retain the information in memory.

4.3 Answer to RQ.3: differences by nationality

Finally, this section addresses RQ.3: “Do Germans and Japanese differ in how frequently they are drawn to look when the person in front turns toward the display?” As noted in the introduction, cultural backgrounds can potentially affect nonverbal communication behaviors such as interpersonal distance Hasler and Friedman (2012); Akechi et al. (2013); Sicorello et al. (2019), suggesting the possibility of differences in how “one person’s head-turn” influences another. However, when comparing the frequency of head-turning across the Walking Past, Attention, and Approach conditions for German and Japanese participants, no statistically significant difference was found between these two groups.

This result suggests that the influence exerted by a front pedestrian’s behavior may be relatively unaffected by differences in interpersonal distance or eye contact specific to a particular nationality. For instance, prior studies on nonverbal communication often focus on scenarios involving mutual eye contact or reducing interpersonal distance. By contrast, the “turning one’s head toward a public display” behavior observed in this experiment is a largely one-sided action—simply deciding whether or not to look at the display—frequently without direct eye contact or distance adjustment with the person in front. Thus, cultural differences may have been less likely to manifest in this context.

However, it is important to note that our sample size was small (8 Germans and 8 Japanese), and only two nationalities were included. Additionally, numerous other factors—such as the movement flow of people, bystanders’ gaze, and crowd conditions—can affect behavioral reactions. In view of these considerations, the answer to RQ.3 is as follows: under the conditions of this study, no difference was observed between German and Japanese participants in the frequency with which they were influenced by a front pedestrian’s head-turning behavior. This suggests that the movements of an avatar’s head and gaze in VR may function similarly even among individuals from different cultural backgrounds. However, this could change if the avatar’s appearance is tailored to a specific culture or age group.

4.4 Deployment in a virtual environment

In this study, we observed pedestrian behavior in a real-world context by means of a VR environment, and the insights gained are also directly applicable to the design of displays and their surroundings within virtual spaces. For example, when placing an advertising display in VR, one could position a guiding avatar in front of the screen; by having the avatar pause and exhibit attentive behavior, users’ gaze can be steered naturally toward the display. Because users cannot easily distinguish whether the avatar is a real pedestrian or a computer-controlled agent, such guidance is unlikely to be perceived as deliberate, allowing a seamless and implicit notification of the display’s presence. This interpretation is consistent with recent work showing that virtual agents can become part of the user’s perceptual frame, influencing how attention and behavior are organized within mediated environments Cesari et al. (2024a). Moreover, findings on embodiment and presence suggest that subtle, embodied cues—such as head turns or brief pauses—can modulate users’ sensorimotor responses and situational awareness in VR Cesari et al. (2024b), helping to explain why even a simple, non-interactive avatar can function effectively as an intermediary between the display and the user.

Such an implicit attention-cueing method must be evaluated not only for its ability to capture gaze but also for its effectiveness in prompting actual behaviors (e.g., clicks, purchases, information retrieval) Sugiyama and Andree (2010). Although the present study did not assess conversion outcomes, it suggests that this approach holds promise as an early-stage attention-cueing technique.

4.5 Limitation

This study has several limitations. First, there is a constraint regarding the setup of avatar behaviors. We limited the avatars’ actions to three patterns (Walking Past, Attention, and Approach), but real-world pedestrian behavior is far more diverse and can include unpredictable factors. For example, we did not examine how unplanned contact between pedestrians or differences in walking speeds might affect behavioral reactions. Consequently, the findings may not fully reflect the complexity of real-world settings.

Next, there are limitations in our data collection methods. In this study, we used a GoPro to record the participant’s perspective and behavior within the VR environment, but we did not obtain detailed data on precise gaze direction or fixation duration on the display or nearby avatars. Using eye-tracking technology could offer deeper insights into the mechanisms behind how pedestrians are guided to look at advertisements or turn their heads.

Additionally, we tested only three conditions related to display placement. In real urban environments, however, displays can be located in a wide variety of places with diverse surroundings, such as different building layouts or traffic volumes. Thus, the conditions we set do not encompass all possible scenarios. It is important to keep in mind that these results, based on specific conditions, may not be applicable to every real-world situation.

In this experiment, participants’ walking was governed by on-screen transitions to reduce simulator sickness and maintain consistent conditions. Movement to the left or right was not permitted. If lateral movement were allowed, the distance between participants and the display or avatars would become another factor, potentially altering how much attention or recognition was directed toward the display. All participants in this study encountered identical avatar paths and surrounding conditions, which helped isolate the avatar’s actions as the main variable. In reality, though, crowd density, visual and auditory stimuli, and other external factors also play a role in pedestrian behavior. Future investigations should take these elements into account. In addition, VR experience was not considered in the recruitment. Even for inexperienced participants, practice before the experiment allowed for smooth execution. However, it is important to note that their limited experience may have influenced participants’ attention, behavior, and sense of immersion.

Moreover, this research involved 18 participants; however, for the cross-national comparison, one American and one Chinese participant were excluded, resulting in 8 participants from Germany and 8 from Japan. While this sample size was sufficient for an initial user experiment, expanding to larger groups in more crowded contexts or other nationalities would boost the generalizability of the findings. The present study included only two nationalities, yet cultural background and pedestrian behavior can be influenced by regional aspects such as urban versus rural conditions. Future studies should enroll a more culturally diverse group of participants to broaden the applicability of these insights.

Finally, since the sample size was limited, we conducted a post hoc power analysis to assess the statistical sensitivity of our experiment. Effect sizes

5 Conclusion

This study investigated, within a virtual environment, whether people passing by a public display are influenced by the behavior of others around them.

The results revealed that pedestrians behind someone who fully turns and approaches the display, or who sees an oncoming pedestrian turning toward it, are more likely to follow suit (RQ.1). However, even when participants were influenced to look at the display, they only glanced at it briefly, which did not lead to effective recognition of the advertisement (RQ.2). Furthermore, no notable differences were found between German and Japanese participants (RQ.3).

These findings suggest that, even for static display content, attracting the “first pedestrian” through visually striking designs or the use of sound can be critical. Even when the VR avatar was controlled as the “first pedestrian,” participants perceived the avatar’s head and gaze movements and were influenced. Therefore, to capture pedestrians’ attention effectively, it is important not only to consider the content of the display but also to carefully plan the display’s placement based on walking directions.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the following restrictions: the dataset includes sensitive information that could compromise the privacy of research participants. Data access is therefore restricted to the research team and under strict ethical standards to ensure data protection and confidentiality. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to KZ, emVtcG9AaWl0LnRzdWt1YmEuYWMuanA=.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the ifgi ethics board at the University of Münster and the ethics committee of the Faculty of Engineering, Information and Systems, University of Tsukuba. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

NK: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Visualization, Writing – original draft. CK: Funding acquisition, Resources, Software, Supervision, Writing – review and editing. KZ: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review and editing.

Funding

The authors declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research has been funded by the Volkswagenstiftung for the project “Distance-Keeping: Influence of the StreetScape (Dist-KISS)” in the call “Corona Crisis and Beyond—Perspectives for Science, Scholarship and Society.” Besides, this work is also supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI under Grant JP21J20397, 24H00892, and JSPS Overseas Challenge Program for Young Researchers.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. Early draft of this paper was helped by OpenAI’s GPT-4o model for improving writing clarity.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frvir.2025.1714725/full#supplementary-material

References

Akechi, H., Senju, A., Uibo, H., Kikuchi, Y., Hasegawa, T., and Hietanen, J. K. (2013). Attention to eye contact in the west and east: autonomic responses and evaluative ratings. PloS One 8, e59312. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0059312

Alt, F., Buschek, D., Heuss, D., and Müller, J. (2021). Orbuculum-predicting when users intend to leave large public displays. Proc. ACM Interact. Mob. Wearable Ubiquitous Technol. 5, 1–16. doi:10.1145/3448075

Aoyagi, S., Yamada, T., Cheng, K., Masuko, S., and Zempo, K. (2023). “Gaze cue switcher for joint attention in vr remote tourism,” in Proceedings of the 2023 ACM symposium on spatial user interaction, 1–2.

Brignull, H., and Rogers, Y. (2003). Enticing people to interact with large public displays in public spaces. Interact 3, 17–24.

Cesari, V., D’Aversa, S., Piarulli, A., Melfi, F., Gemignani, A., and Menicucci, D. (2024a). Sense of agency and skills learning in virtual-mediated environment: a systematic review. Brain Sci. 14, 350. doi:10.3390/brainsci14040350

Cesari, V., Orrù, G., Piarulli, A., Vallefuoco, A., Melfi, F., Gemignani, A., et al. (2024b). The effects of right temporoparietal junction stimulation on embodiment, presence, and performance in teleoperation. AIMS Neuroscience 11, 352–373. doi:10.3934/neuroscience.2024022

Christidou, D. (2018). Art on the move: the role of joint attention in visitors’ encounters with artworks. Learn. Cult. Soc. Interact. 19, 1–10. doi:10.1016/j.lcsi.2018.03.008

Corbetta, M., and Shulman, G. L. (2002). Control of goal-directed and stimulus-driven attention in the brain. Nat. Reviews Neuroscience 3, 201–215. doi:10.1038/nrn755

Europeans Hasler and Friedman (2025). Freepix. Available online at: https://www.freepik.com.

Hasler, B. S., and Friedman, D. A. (2012). Sociocultural conventions in avatar-mediated nonverbal communication: a cross-cultural analysis of virtual proxemics. J. Intercult. Commun. Res. 41, 238–259. doi:10.1080/17475759.2012.728764

Huang, C.-M., and Thomaz, A. L. (2010). “Joint attention in human-robot interaction,” in AAAI fall symposium: dialog with robots.

Huang, E. M., Koster, A., and Borchers, J. (2008). “Overcoming assumptions and uncovering practices: when does the public really look at public displays?,” in Pervasive computing: 6Th international Conference, pervasive 2008 Sydney, Australia, May 19-22, 2008 Proceedings 6 (Springer), 228–243.

Kaplan, F., and Hafner, V. V. (2006). The challenges of joint attention. Interact. Stud. 7, 135–169. doi:10.1075/is.7.2.04kap

Kaspar, K., Weber, S. L., and Wilbers, A.-K. (2019). Personally relevant online advertisements: effects of demographic targeting on visual attention and brand evaluation. PloS One 14, e0212419. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0212419

Kukka, H., Oja, H., Kostakos, V., Gonçalves, J., and Ojala, T. (2013). What makes you click: exploring visual signals to entice interaction on public displays. Proc. SIGCHI Conf. Hum. Factors Comput. Syst., 1699–1708. doi:10.1145/2470654.2466225

Kuratomo, N., Kray, C., and Zempo, K. (2025). “Assessing the extent of the honey-pot effect on public display: a preliminary study in a virtual environment,” in Proceedings of the augmented humans international conference 2025, 463–466.

Limerick, H. (2020). “Call to interact: communicating interactivity and affordances for contactless gesture controlled public displays,” in Proceedings of the 9TH ACM international symposium on pervasive displays, 63–70.

Mäkelä, V., Radiah, R., Alsherif, S., Khamis, M., Xiao, C., Borchert, L., et al. (2020). “Virtual field studies: conducting studies on public displays in virtual reality,” in Proceedings of the 2020 CHI conference on human factors in computing systems, 1–15.

Michelis, D., and Müller, J. (2011). The audience funnel: observations of gesture based interaction with multiple large displays in a city center. Intl. J. Human–Computer Interact. 27, 562–579. doi:10.1080/10447318.2011.555299

Müller, J., and Krüger, A. (2009). “Mobidic: context adaptive digital signage with coupons,” in European conference on ambient intelligence (Springer), 24–33.

Müller, J., Wilmsmann, D., Exeler, J., Buzeck, M., Schmidt, A., Jay, T., et al. (2009). “Display blindness: the effect of expectations on attention towards digital signage,” in Pervasive computing: 7th International Conference, pervasive 2009, Nara, Japan, May 11-14, 2009. Proceedings 7 (Springer), 1–8.

Müller, J., Alt, F., Michelis, D., and Schmidt, A. (2010). “Requirements and design space for interactive public displays,” in Proceedings of the 18th ACM international conference on Multimedia, 1285–1294.

Nelson, M. G., Yang, F.-C., Koilias, A., Anagnostopoulos, C.-N., and Mousas, C. (2024). “Avoiding virtual characters: the effects of proximity and gesture,” in 2024 IEEE international symposium on mixed and augmented reality (ISMAR) (IEEE), 41–50.

Parra, G., Klerkx, J., and Duval, E. (2014). “Understanding engagement with interactive public displays: an awareness campaign in the wild,” in Proceedings of the international symposium on pervasive displays, 180–185.

Petersen, S. E., and Posner, M. I. (2012). The attention system of the human brain: 20 years after. Annu. Review Neuroscience 35, 73–89. doi:10.1146/annurev-neuro-062111-150525

Riva, G., Mantovani, F., Capideville, C. S., Preziosa, A., Morganti, F., Villani, D., et al. (2007). Affective interactions using virtual reality: the link between presence and emotions. Cyberpsychology and Behavior 10, 45–56. doi:10.1089/cpb.2006.9993

Rodriguez, I. B., and Marquardt, N. (2017). “Gesture elicitation study on how to opt-in and opt-out from interactions with public displays,” in Proceedings of the 2017 ACM international conference on interactive surfaces and spaces, 32–41.

Sahibzada, H., Hornecker, E., Echtler, F., and Fischer, P. T. (2017). “Designing interactive advertisements for public displays,” in Proceedings of the 2017 CHI conference on human factors in computing systems, 1518–1529.

Schnier, C., Pitsch, K., Dierker, A., and Hermann, T. (2011). “Collaboration in augmented reality: how to establish coordination and joint attention?,” in Ecscw 2011: proceedings of the 12th European Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work, 24-28 September 2011 (Aarhus Denmark: Springer), 405–416.

Schott, E., López García, I., Semple, L. A., and Froehlich, B. (2025). “Estimating detection thresholds of being looked at in virtual reality for avatar redirection,” in Proceedings of the 2025 CHI conference on human factors in computing systems, 1–14.

Sicorello, M., Stevanov, J., Ashida, H., and Hecht, H. (2019). Effect of gaze on personal space: a Japanese–German cross-cultural study. J. Cross-Cultural Psychol. 50, 8–21. doi:10.1177/0022022118798513

Sugiyama, K., and Andree, T. (2010). The dentsu way: secrets of cross switch marketing from the world’s most innovative advertising agency. New York, NY, United States: McGraw Hill Professional.

Tafreshi, A. E. S., Soro, A., and Tröster, G. (2018). Automatic, gestural, voice, positional, or cross-device interaction? Comparing interaction methods to indicate topics of interest to public displays. Front. ICT 5, 20. doi:10.3389/fict.2018.00020

Veenstra, M., Wouters, N., Kanis, M., Brandenburg, S., te Raa, K., Wigger, B., et al. (2015). “Should public displays be interactive? Evaluating the impact of interactivity on audience engagement,” in Proceedings of the 4th international symposium on pervasive displays, 15–21.

Vogel, D., and Balakrishnan, R. (2004). “Interactive public ambient displays: transitioning from implicit to explicit, public to personal, interaction with multiple users,” in Proceedings of the 17th annual ACM symposium on user interface software and technology, 137–146.

Keywords: honey-pot effect, public display, virtual reality, pedestrian attention, cultural comparison

Citation: Kuratomo N, Kray C and Zempo K (2025) Honey-pot effect on pedestrian attention to public displays in a virtual environment: head turns, walking past, and direct approaches. Front. Virtual Real. 6:1714725. doi: 10.3389/frvir.2025.1714725

Received: 28 September 2025; Accepted: 18 November 2025;

Published: 04 December 2025.

Edited by:

Ramy Hammady, University of Southampton, United KingdomReviewed by:

Valentina Cesari, IMT School for Advanced Studies Lucca, ItalyEleonora Malloggi, University of Trento, Italy

Copyright © 2025 Kuratomo, Kray and Zempo. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Keiichi Zempo, emVtcG9AaWl0LnRzdWt1YmEuYWMuanA=

†Present address: Noko Kuratomo, Human Science Division, Railway Technical Research Institute, Tokyo, Japan

Noko Kuratomo

Noko Kuratomo Christian Kray

Christian Kray Keiichi Zempo

Keiichi Zempo