- 1ICAR-Indian Agricultural Research Institute, New Delhi, India

- 2Borlaug Institute of South Asia, New Delhi, India

- 3ICAR-Central Research Institute for Dryland Agriculture, Hyderabad, India

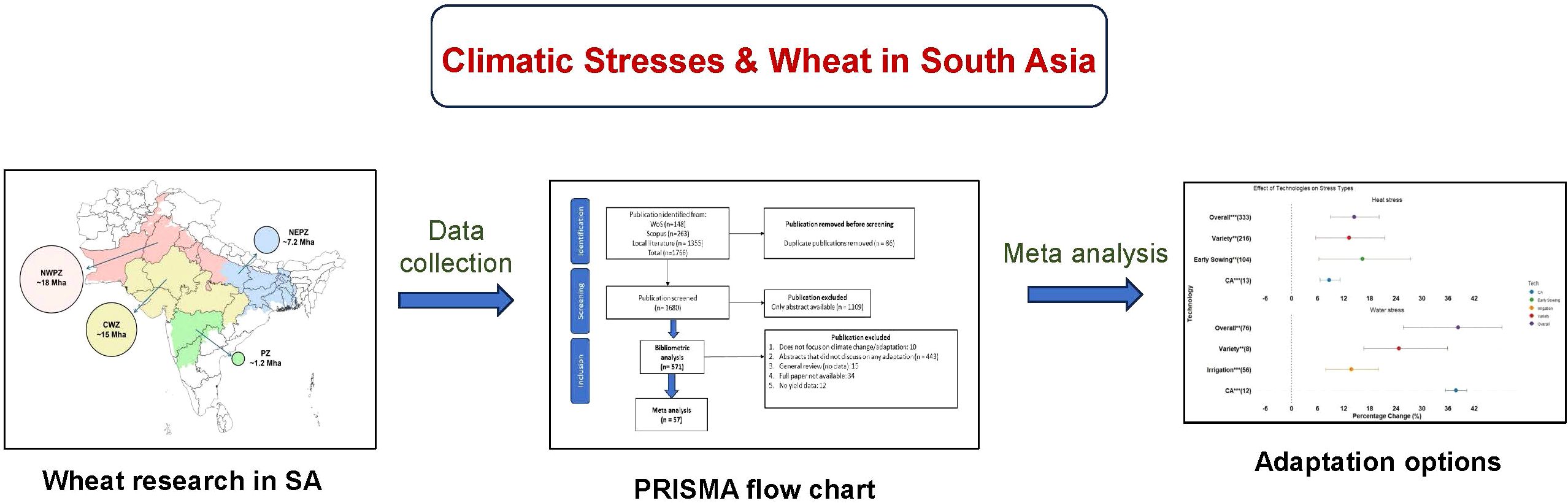

Introduction: Wheat in South Asia faces multiple climatic stresses. This study systematically reviews the effects of these hazards on wheat and identifies adaptation options to reduce their impact on productivity.

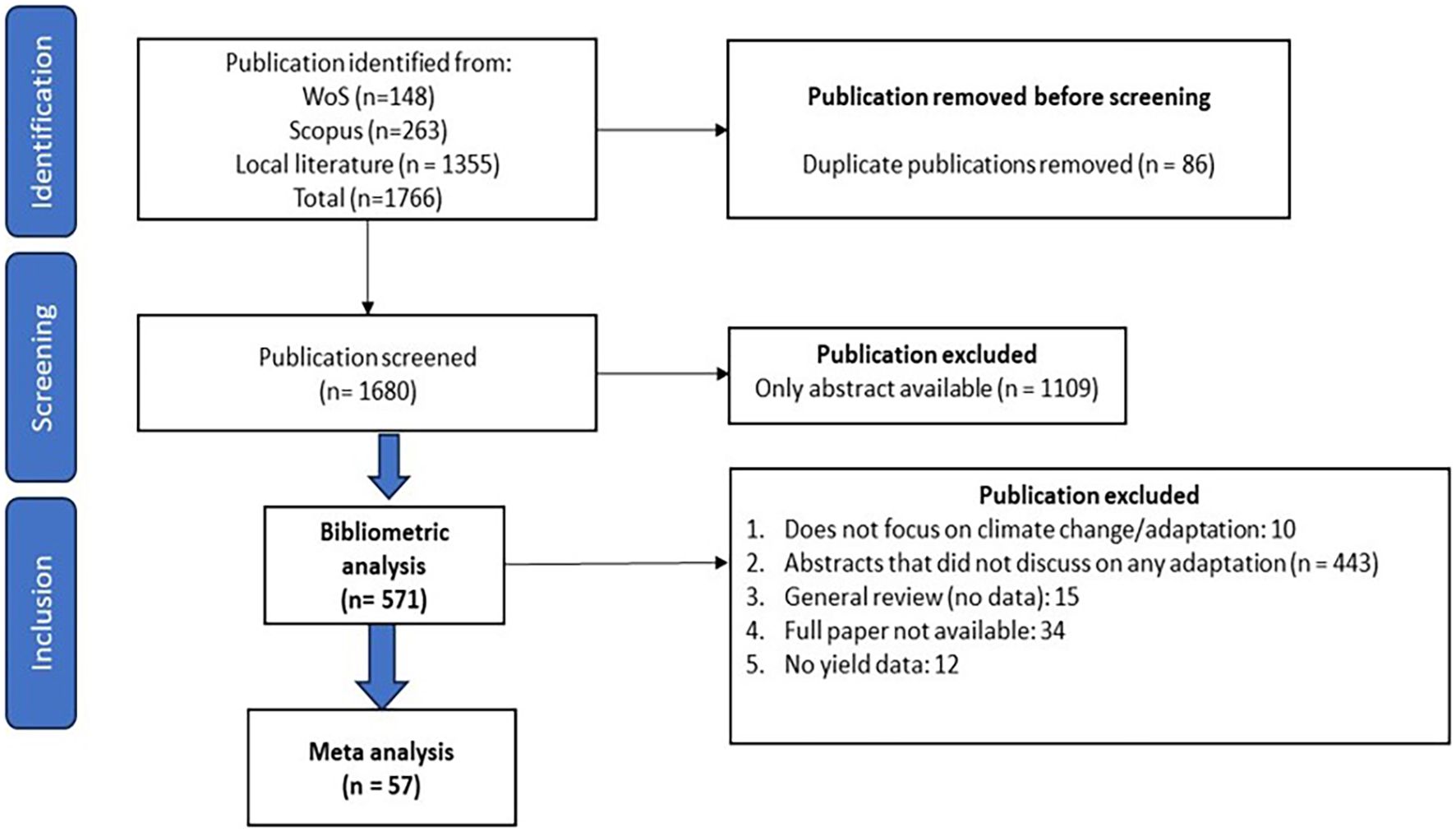

Methods: Literature searches were conducted using academic databases such as Scopus and Web of Science, along with South Asian sources. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) statement was followed for quantitative synthesis of the literature.

Results and discussion: Bibliometric analysis of the studies revealed that, heat stress and water stress are major climatic hazard affecting wheat crop of this region. The terminal heat stress was also highlighted in recent publications. Meta-analysis of the extracted data (401 data points) from selected publications (57 papers) provided new evidence on the suitability of different adaptation options under heat and water stress condition in different agroecological regions of South Asia. It was observed that under heat stress condition, adoption of heat tolerant varieties, early sowing and conservation agriculture (CA) practices increased the yield by 13.2%, 16.3% and 8.6%, respectively. Under water stress, yield improvement was 24.7% with growing drought tolerant varieties, 37.8% with CA practices and 13.7% with application of additional irrigation. The overall effectiveness of growing heat and drought tolerant varieties across agroecological zones followed the order CWZ > NEPZ > PZ > NWPZ. The CWZ and NEPZ exhibited the greatest yield gains, driven by the strong positive response to heat-tolerant varieties. In case of early sowing by 7-10 days, the effectiveness will follow the order NEPZ > NWPZ > CWZ. Overall, these findings highlight the importance of considering regional climatic conditions when designing adaptation strategies to enhance wheat productivity under rising temperatures.

Introduction

Climate change poses significant challenges to the agriculture sector, affecting crop production and thereby having a significant impact on global food security (Vervoort et al., 2014). The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) reiterated that global average surface temperature during the period of 2011 to 2020 was 1.09 °C higher than that of 1850 to 1900, and 0.19 °C higher than that of 2003 to 2012 (IPCC, 2019). South Asia (SA), as defined in this study, includes Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka. The region is characterized by diverse agroecological zones, monsoon dependent climate, and a high dependence on agriculture for livelihoods. South Asia is home to one-fourth of the global population and it will grow to 40% by the year 2050 (World Health Organization (WHO), 2020). Climate change and climatic variability poses serious challenges to South Asian agriculture (Aryal et al., 2020). Wheat is a staple food crop contributing to around 20% of the calories and protein intake of human beings of South Asia (Khan et al., 2023). Wheat crop, grown on more than 13.9 million hectares area in South Asian region including rice-wheat and cotton-wheat cropping systems, experience heat stress (Asseng et al., 2015). Wheat is highly climate sensitive crop and the growth and developmental stages of wheat are affected by temperature (Dubey et al., 2019). Potential yields in wheat are constrained by abiotic stresses which includes terminal heat stress, water scarcity, lodging, and salt stress. Increasing temperature will have detrimental effect wheat yields in tropical regions of South Asia where the crop is already cultivated near its temperature tolerance threshold (Kelkar and Bhadwal, 2007). Besides this, wheat will face the more serious consequences due to the occurrence of short episodes of extremely high temperatures in future (Dubey et al., 2020). In South Asia, major wheat-growing nations include India, Pakistan, Nepal, and Bangladesh, where wheat sowing is often delayed due to the late harvesting of preceding crops such as rice and cotton (Nawaz et al., 2019; Rehman et al., 2021). Spring wheat of South Asia is sown in the months of November and December and harvested during April. The crop has temperature requirement of 12 to 22 °C particularly during anthesis and grain filling stages. Higher temperatures above 31 °C in late-sown wheat adversely affect various physiological processes, resulting in a reduced crop growth period and lower yield (Shah et al., 2016). According to Dubey et al. (2020), terminal heat stress in wheat occurs when mean temperature during grain filling stage goes above 31 °C. Drought stress also affects different physiological and biochemical processes in wheat crop resulting in reduced yield (Akhtar et al., 2021). It affects the assimilate transport, causes reduced leaf area and stomatal closure, and under severe water stress shortens life cycle of the crop (Dar et al., 2020; Ostmeyer et al., 2020). While more than 85% of the wheat area in South Asia is irrigated (Kumar and Rai, 2014), drought stress continues to pose a major challenge. Declining groundwater tables, increasing competition for irrigation water, and reduced water-use efficiency under rising temperatures are making irrigation less reliable.

A simulation study conducted by Kumar et al. (2014) showed that, in India, climate change will reduce wheat yield by 6 - 23% by 2050 and 15 - 25% by 2080. Similarly in Pakistan, yield reduction in non-heat-resistant wheat varieties could go up to 6-13% in future (50 years) compared to the last 40 years (Ishtiaq et al., 2022).

Developing effective adaptation strategies can help mitigate or even prevent some of the adverse effects of climate change on wheat crop. Adaptation to climate change refers to actions undertaken to reduce vulnerability and enhance the resilience of a system (Aryal et al., 2020). In the South Asian region, farmers employ various management practices to adapt to the changing climate. The prevailing agricultural management practices in a region can be optimized and scaled up as suitable adaptation options (Aryal et al., 2020). Hence, there is a need to identify effective adaptation strategies to mitigate the adverse impacts of climate change on wheat yield in the SA region (Hernandez-Ochoa et al., 2019).

In recent years, the scientific community has increasingly undertaken multidisciplinary studies to address the impacts of climate change on agriculture. Numerous studies have examined the effects of climate change on wheat production in various South Asian countries, such as India (Bhatia et al., 2010; Chakrabarti et al., 2021; Devate et al., 2022; Dubey et al., 2020; Jat et al., 2018; Khan et al., 2023; Kumari et al., 2013), Pakistan, (Ishtiaq et al., 2022; Rehman et al., 2021; Jatoi et al., 2021; Sohail et al., 2020) and Bangladesh (Mahfuz Bazzaz et al., 2019; Pal et al., 2022). In recent years, meta-analysis has emerged as a widely used approach for synthesizing individual studies and drawing conclusions about the effects of specific treatments (Sharma et al., 2019). SLR and meta-analysis tools have been employed in agricultural research also to analyze and integrate data (Philibert et al., 2012; Makowski et al., 2019). A meta-analysis conducted by Challinor et al. (2014) on global wheat adaptation to the changing climate, suggested that adaptation strategies can contribute to yield increase in wheat by 7-15% in future climate. But it was done using global datasets and did not focus on the different agroecological zones (AEZs) of South Asia.

Some efforts have been made by a few researchers to systematically review the impact of climate change on agriculture in South Asia and India (Aryal et al., 2020; Datta et al., 2022; Li et al., 2024). Most of them have provided broad regional assessments without focusing on a specific cereal crop like wheat. Besides this, the suitability of different adaptation options in different agroecological zones of SA was not analyzed. This lack of granularity limits the applicability of their findings for local-scale adaptation planning. The present study addresses this gap by conducting a crop-specific and agroecological zone-wise bibliometric analysis followed by meta-analysis to identify climate hazards and suitable adaptation options in wheat across South Asia. The bibliometric analysis was conducted to systematically map research trends and research hotspots related to climate change impacts and adaptation in wheat. Insights from this analysis helped identify knowledge gaps, which guided the selection and focus of data extraction for the subsequent meta-analysis. This study is the first attempt to systematically review the literature on climate change and wheat in South Asia. It synthesizes fragmented research into a comprehensive, agroecological zone–wise assessment that provides actionable insights for enhancing climate resilience in agriculture.

Materials and methods

Literature collection

The systematic literature review (SLR) is a method for identifying, analyzing, and interpreting relevant studies related to a specific research question of interest (Kitchenham and Charters, 2007). Considering the extensive body of research on climate change and wheat, bibliometric analyses of published studies can help identify research trends, gaps, and future research needs in this area. In the present study, SLR was conducted to address the research question: “How is climate change impacting wheat, and what adaptation strategies can be implemented across various agroecological regions of South Asia?” The data for SLR was collected using academic databases like Scopus, Web of Science, as well as local literature from India, Pakistan and Bangladesh. The keywords used were grouped in four different categories i.e. climatic phenomenon/hazards, effect of climatic hazards/risk, Adaptation options/practices and geographical region. The chosen keywords were searched in the abstract, and the title of the publications. The PRISMA statement was followed (Moher et al., 2009), and a quantitative synthesis of the literature was conducted (Figure 1). A total of 1,766 articles were identified, of which 263 were from Scopus, 148 from Web of Science, and 1,355 from local literature. After removing duplicate publications, 1,680 articles were used for further analysis.

Figure 1. PRISMA flow chart of the search of literature related to effect of climate change on wheat crop.

Bibliometric analysis

Bibliometric analysis is a quantifiable research methodology to understand the trends and patterns in published literature by using variety of bibliometric indicators, like journal impact factors, authorship, co-authorship, as well as citation counts (Donthu et al., 2021). Out of the total 1680 abstracts, 1109 were not having full length manuscript, hence they were discarded and remaining 571 articles published were used for the bibliometric analysis (Figure 1). The present study focused on year-wise trends in publication counts, trending keywords, climatic hazards, adaptation options used, and sub-regions of study in South Asia. The retrieved records were analyzed using R software (R 4.4.1) to determine year-wise publication trends, trending topics, and adaptation options for specific climatic hazards.

Meta-analysis

In recent years, meta-analysis has become a popular approach in agricultural research, to find the effectiveness of management options on crop productivity by combining results from different individual studies. In the present research, the 571 publications used for bibliometric analysis, were further screened using different exclusion criteria. Among the 571 publications, ten did not focus on any climatic change or adaptation, while fifteen were general reviews lacking experimental data. Of the remaining studies, 443 examined the impacts of climate change but did not address any adaptation measures to mitigate climatic stresses. For thirty-four papers, full text was unavailable, and twelve articles did not report quantified data on wheat yield (Figure 1). Consequently, the remaining fifty-seven research papers were included in the meta-analysis (Supplementary Table 1). Yield data from these fifty-seven publications were systematically extracted and digitized for analysis.

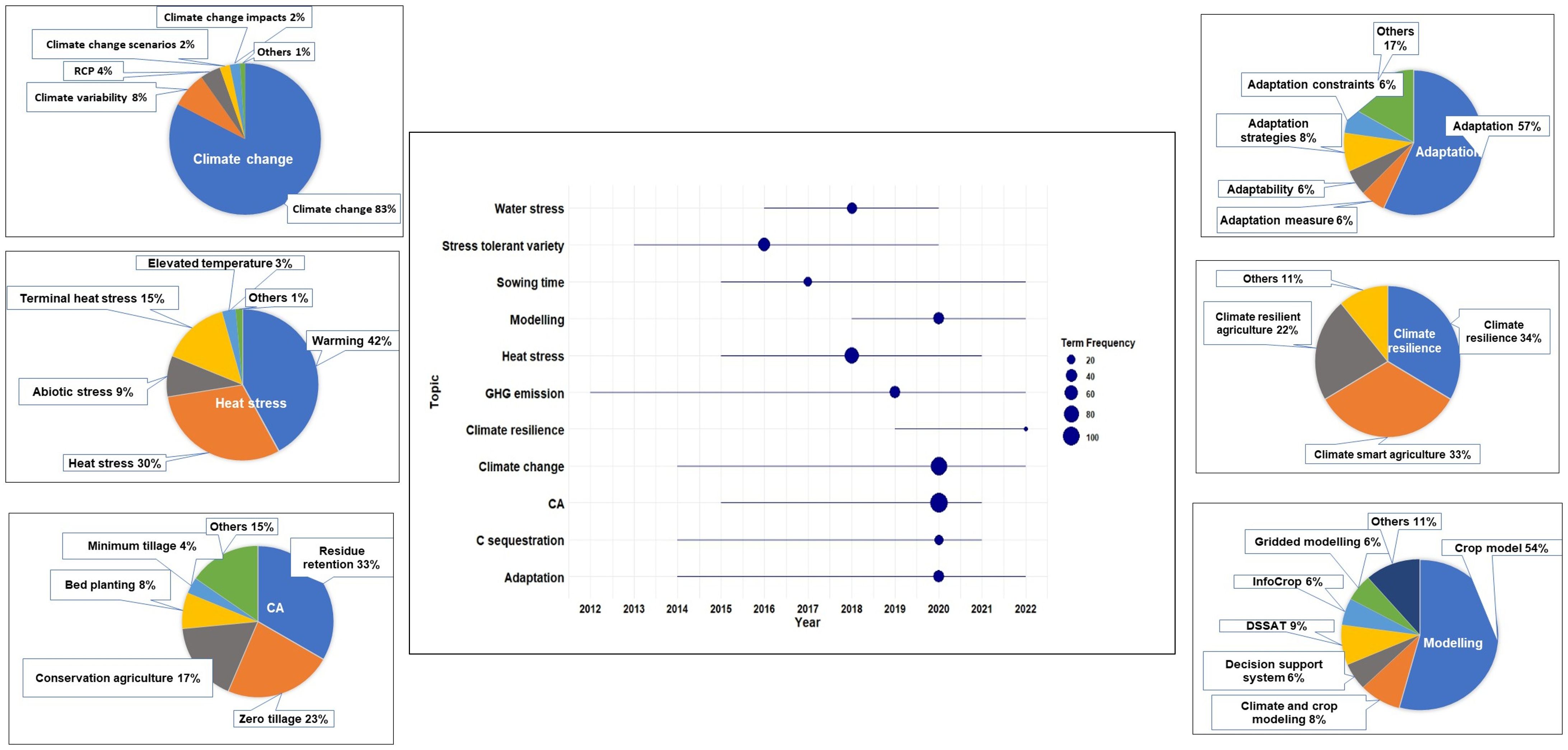

Data on the study region, hazard type, risk type, study method, number of treatments, number of replicates, reported adaptation options (if any), wheat yield in the control treatment and with adaptation options, and standard deviation were extracted and stored in Excel. Table 1 lists the details about control and adaptation option. The study utilized data, such as treatment means (), standard deviations (σ), and sample sizes (n) from the experiments. In certain studies, instead of standard deviation, standard error of the mean (σ) and coefficient of variation (CV) were provided. In those cases, σ was calculated using the formulas given below (Equations 1, 2).

The data was then analyzed in R software to determine treatment effects (adaptation options) and forest plot graphs were drawn of individual effect sizes for each study. Effect size was measured as Hedges’ d. A standardized metrics called response ratio (RR) was used to measure the effect of different adaptation option on wheat yield (Qin et al., 2021; Yang et al., 2022). This approach compares the yield obtained with different adaptation options and the conventional farmers’ practices. To enable statistical analysis, RR was converted into its natural logarithm, ln(RR) (Equation 3).

The approach provides a standardized measure of effect size, for comparing yield across different studies and also interprets the result for studying the effectiveness of different adaptation options on wheat yield under different stress conditions. Mean effect size was then converted to percentage change using the below equation (Equation 4).

The data included several observations from the same study creating dependencies among the data points. To address this, a multi-level model was used, incorporating random effects of study IDs and regions which helped in efficiently handling hierarchical structures, providing reliable estimation of the mean effect size and accurately distributing variability across different levels.

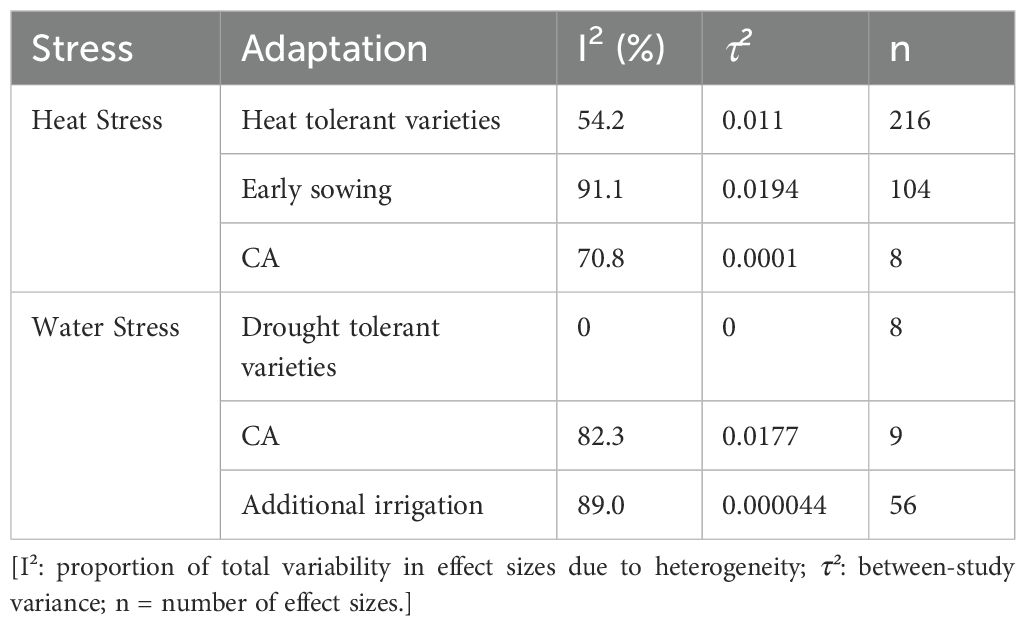

Heterogeneity

Heterogeneity represents the variation in effect sizes observed among different studies, which can result from differences in research methodology, sample characteristics, treatment conditions, or environmental influences (Borenstein et al., 2020). To assess the consistency of effect sizes among studies, heterogeneity statistics were calculated using Cochran’s Q test, the I² statistic. The I² statistic quantified the proportion of total variation attributable to true heterogeneity rather than chance, with values of 25%, 50%, and 75% interpreted as low, moderate, and high heterogeneity, respectively (Higgins et al., 2003). The between-study variance (τ²), represent the absolute magnitude of true effect variation across studies. All analyses were conducted separately for heat and water stress conditions, and for key adaptation measures.

Agroecological zones of South Asia

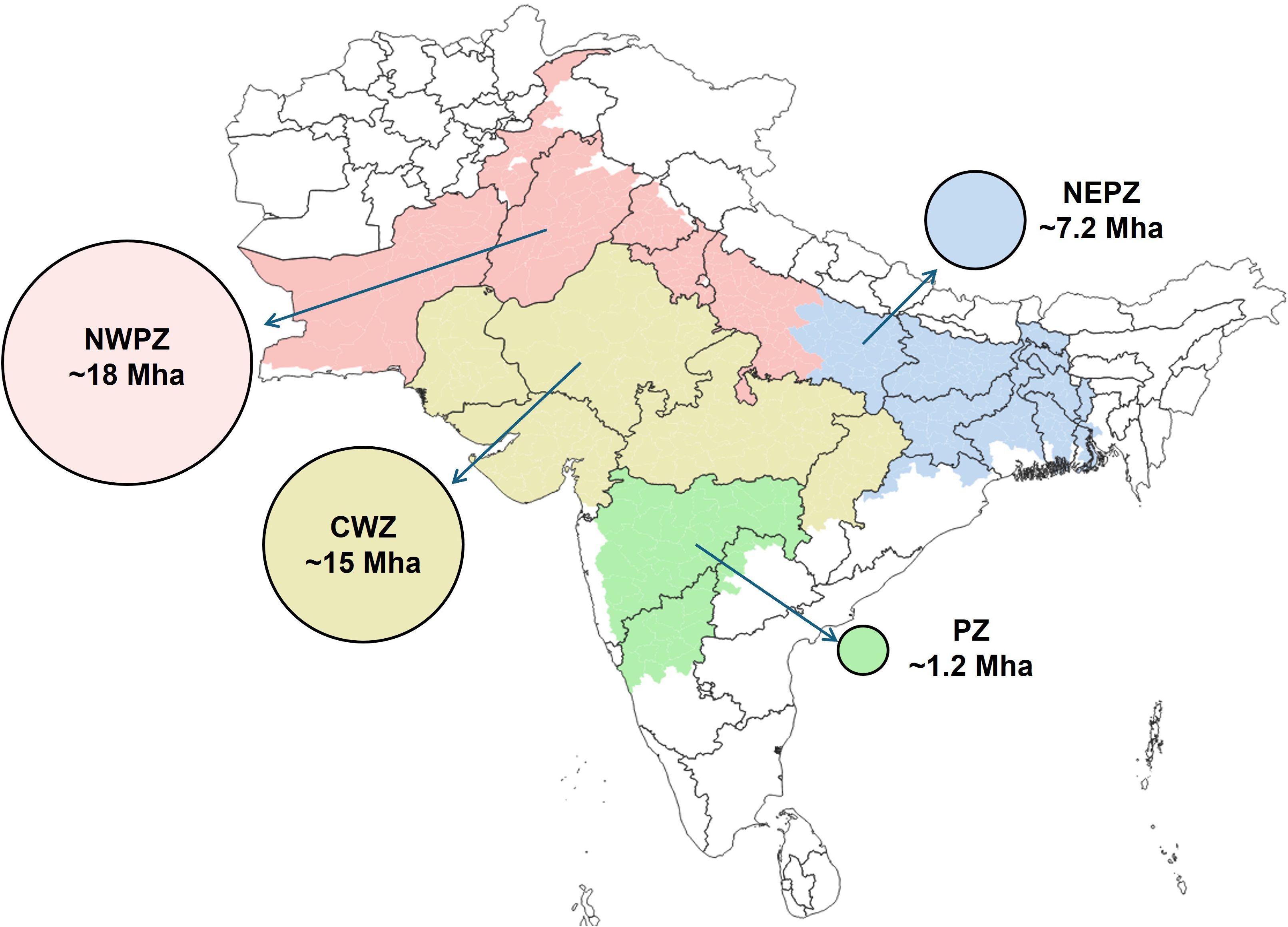

South Asia is classified into different agroecological zones (AEZs) by Köppen and Geiger (1930). Among different AEZs, wheat crop is grown majorly in four different zones, namely, north-western plain zone (NWPZ), central western zone (CWZ), north-eastern plain zone (NEPZ) and peninsular zone (PZ) (Figure 2). Area under wheat is highest (18 Mha) in NWPZ, followed by CWZ (15 Mha), NEPZ (7.2 Mha) and PZ (1.2 Mha). The NWPZ experiences a semi-arid to sub-humid climate, characterized by hot summers, cool winters, and low to moderate rainfall predominantly from the southwest monsoon. The NEPZ has a humid to sub-humid tropical climate, marked by high rainfall, warm summers, and mild winters. The CWZ features a semi-arid to dry sub-humid climate with hot, dry summers and moderate monsoonal rainfall. The PZ has a tropical climate with relatively moderate temperature fluctuations and receives rainfall from both the southwest and northeast monsoons. It experiences mild winters, hot summers, and high humidity, especially in coastal areas. The data reported in the papers were classified based on their applicability in different agro-ecological zones (AEZs) of SA. Information from the publications was obtained for four major AEZs: the NWPZ, NEPZ, CWZ and PZ. The suitability of adaptation options in these zones was further analyzed using the same approach, and forest plots were generated to assess the percentage benefits of the adaptation options across the different AEZs.

Figure 2. Area under wheat crop in different agroecological zones (AEZ) of South Asia. [NWPZ, North-western plain zone; NEPZ, North-eastern plain zone; CWZ, Central western zone; PZ, Peninsular zone].

Calculation of effectiveness index

The effectiveness of the adaptation technologies in different zones was calculated using the effectiveness index with the following formula (Equation 5):

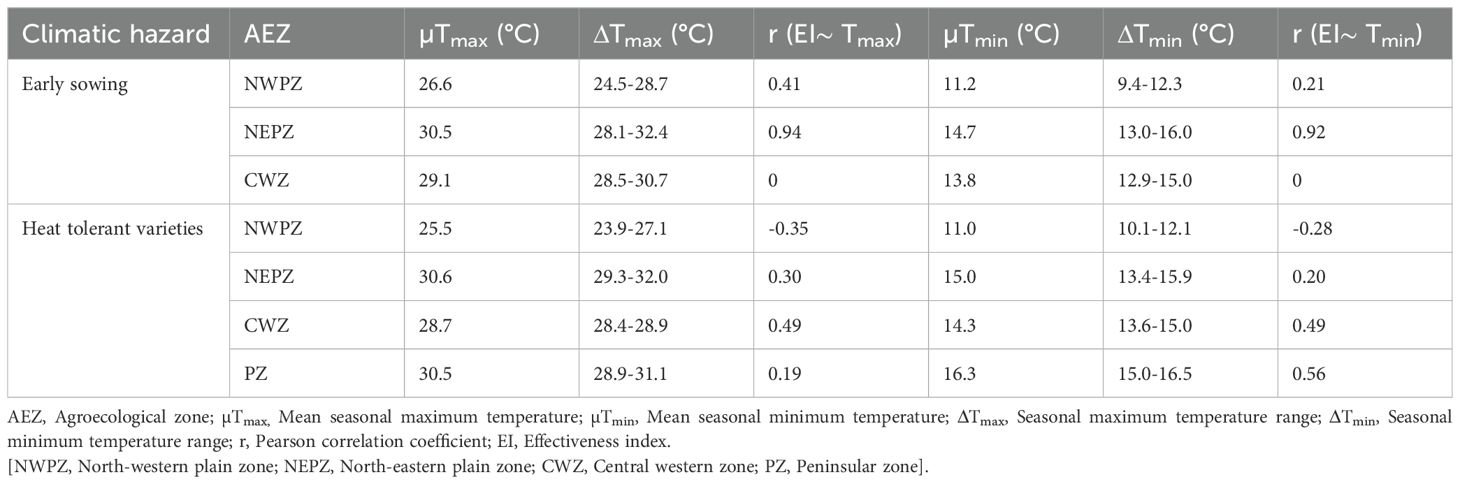

The maximum and minimum temperatures during the crop growth period were derived from multiple experimental datasets reported in the selected literature. Using this information, the correlation between the Effectiveness Index (EI) and seasonal maximum and minimum temperatures was analyzed across different zones to assess the relationship between temperatures and the effectiveness of the adaptation technology. The Pearson correlation coefficient was used to quantify the relationship between the EI and seasonal maximum and minimum temperatures across agro-ecological zones.

Results

Bibliometric analysis

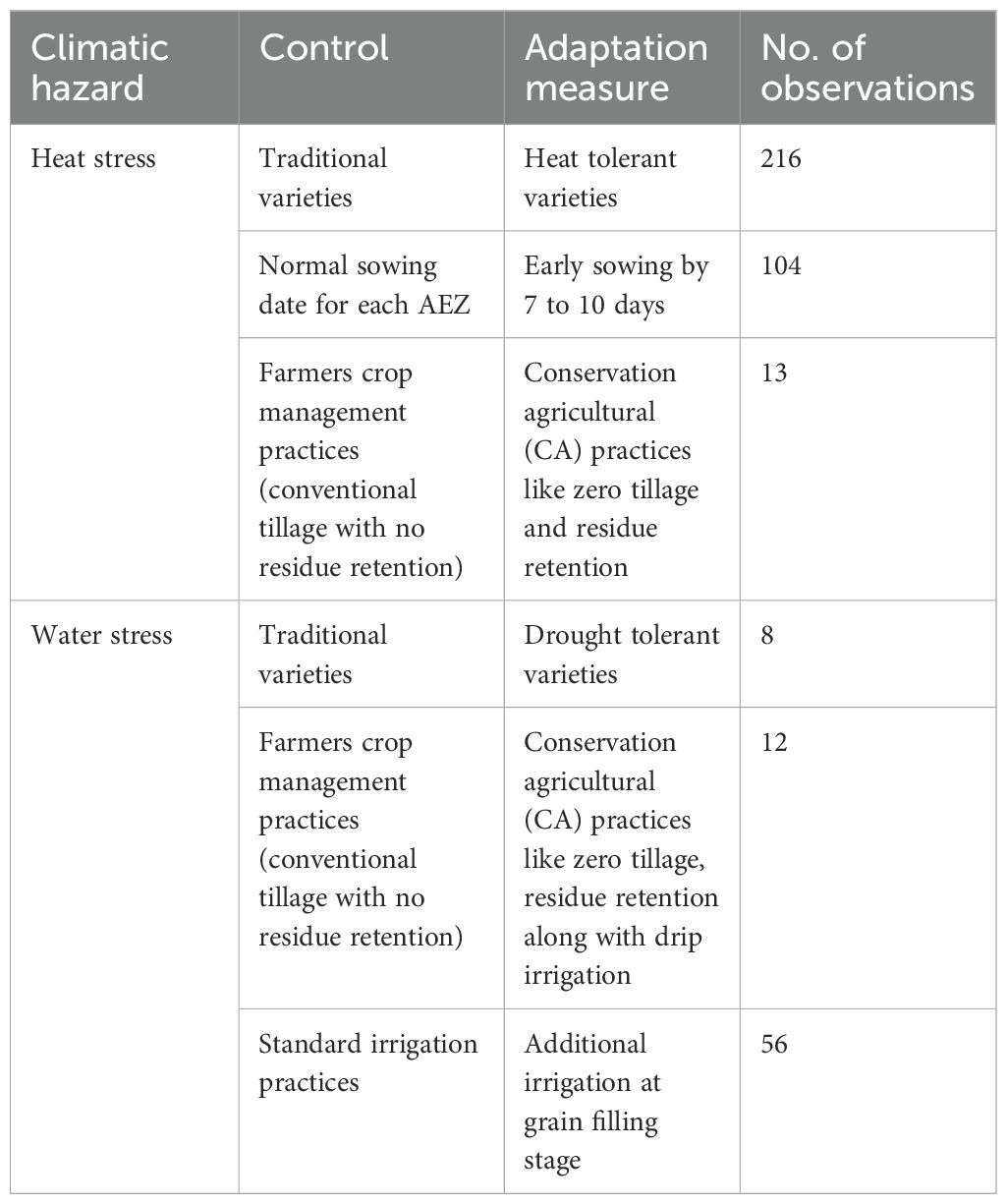

Number of publications on wheat and climate change increased over the years (Supplementary Figure 1). After year 2005, number of publications gradually increased reaching a peak of 58 in 2022. Figure 3 depicts the different trending topics-such as climate change, heat stress, water stress, adaptation, stress-tolerant varieties, sowing time, conservation agriculture (CA), GHG emissions, C sequestration, modelling, and climate resilience-that were reported in various publications from 2012 to 2022. The graph shows the publication frequency of these topics over time. The most frequently mentioned topics were CA (117 mentions) followed by climate change (92) and heat stress (69) (Figure 3). Although topics like climate change, GHG emission, CA and C sequestration were being prevalent since the beginning of the study period, but the distribution of these topics as shown in Figure 3 reveals that the median publication number is shifted to later years.

Major stresses

Heat and water stress were identified as the two major climatic hazards affecting wheat in South Asia. Between 2015 and 2021, heat stress was the most frequently reported (69 mentions), followed by water stress (31 mentions). Terminal heat stress was specifically highlighted during 2018-2019. These stresses, particularly when they occur during the reproductive and grain-filling stages, can result in substantial yield losses and reduced grain quality.

Within these broad topics, several related topics with similar meanings were embedded. For example, in the climate change category, two major keywords were “climate change” (83%) and “climate variability” (8%) (Figure 3). Similarly, in the heat stress category, the major keyword was “warming” (42%), followed by “heat stress” (30%) and “terminal heat stress” (15%).

Adaptation options

Adaptation strategies corresponding to these hazards are summarized in Table 1. In case of adaptation category, major keywords were adaptation (57%) and adaptation strategies (8%). The adoption of stress-tolerant varieties, adjusted sowing windows, CA practices, and improved water management has been widely suggested as an effective adaptation strategy. Among different adaptation options, CA had 117 mentions, followed by stress tolerant variety (44 mentions), change in sowing time (20 mentions) and water management (20 mentions). In CA category the main contributing keywords were, residue retention (33%), zero tillage (23%), conservation agriculture (17%), and bed planting (8%).

The distribution of the topics over time showed certain variations, with topics like climate change, adaptation, GHG emission and C sequestration mentioned since 2012 onwards. The term climate resilience was contributed by keywords as, climate resilience (34%), climate smart agriculture (33%) and climate resilient agriculture (22%). The contemporary topic of climate resilience got attention during the period 2019 to 2022 showing that the concept was introduced later. Stress tolerant variety was mentioned since 2013 to 2020, while change in sowing time during the period of 2015 to 2022 and CA from 2015 to 2021. Research publications involving modelling study, had 35 mentions and were distributed over the period of 2018 to 2022. Publications on modelling comprised keywords like, crop model (54%), DSSAT model (9%) and climate and crop modelling (8%).

Country-wise distribution

Among the different countries of SA, India shared the highest percentage of the studies (57%), followed by Pakistan (16%), Bangladesh (14%), and Nepal (3%). We could not find any related studies from Afghanistan, Bhutan and Sri Lanka. This distribution reflects the intensity of wheat cultivation and the research focus in major wheat-growing regions of the subcontinent. The uneven distribution may be attributed to differences in research infrastructure, data accessibility, and the relative importance of wheat in national cropping systems.

Meta-analysis

Adaptation options for heat stress and water stress

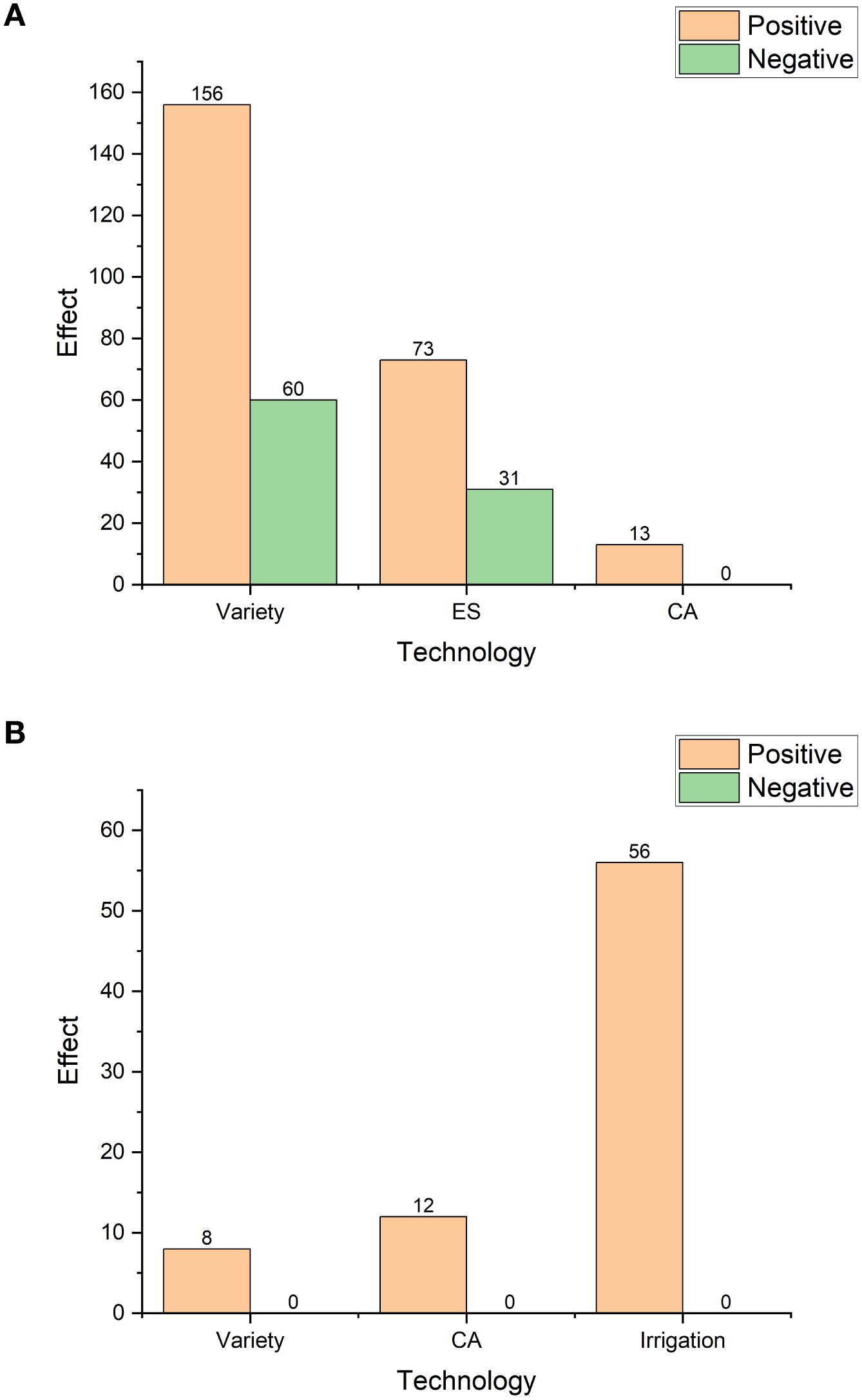

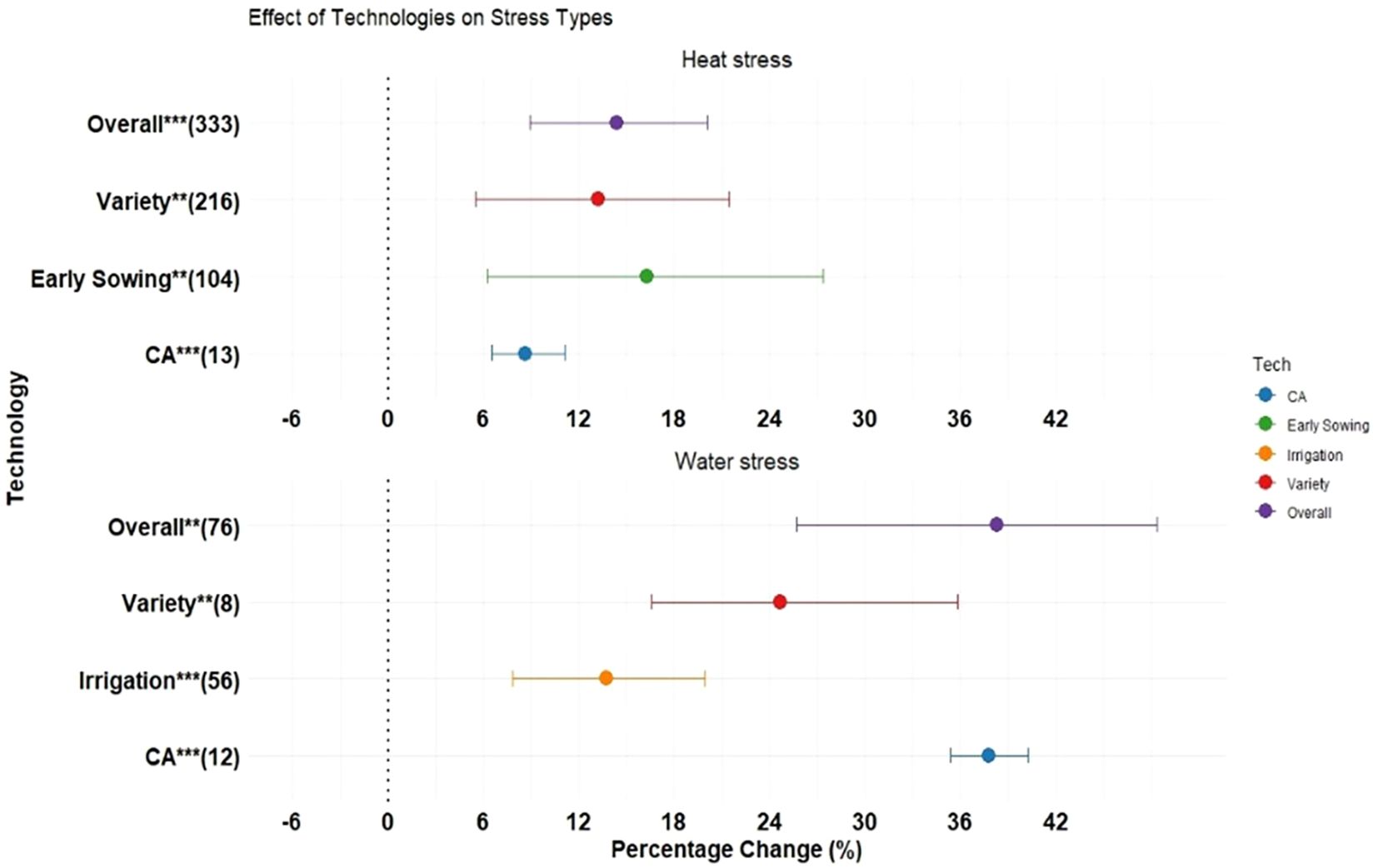

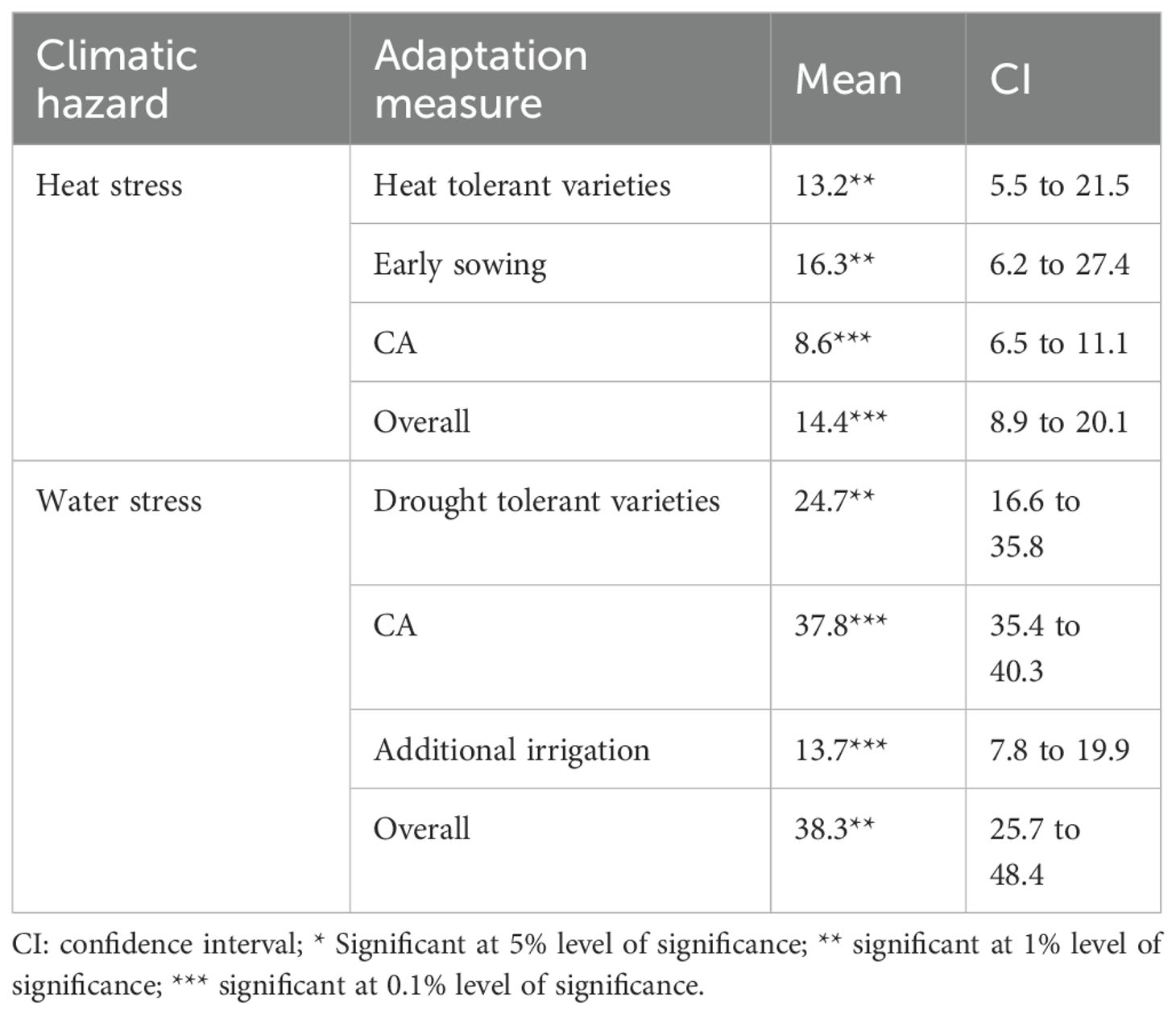

Our analysis showed that the response of wheat yield to different adaptation management practices was predominantly positive. In case of heat stress, about 72% of the data points related to heat-tolerant varieties showed a positive yield response while 28% had negative effect (Figure 4A). Early sowing affected yield in 70% of cases positively and 30% negatively. Effect of CA practices was positive on wheat yield under heat stress condition (Figure 4A). Figure 5 depicts the effect size of different adaptation option on heat and water stress. Results showed that under heat stress conditions, adaptation measures such as growing heat-tolerant varieties, early sowing, and CA practices can help improve the yield of wheat (Figure 5). Under heat stress condition, yield increase was found to be 13.2% (95% CI: 5.5-21.5%), with adoption of heat tolerant varieties, 16.3% (95% CI: 6.2-27.4%), with early sowing and 8.6% (95% CI: 6.5-11.1%), with CA practices (Table 2).

Figure 4. Number of effect sizes of wheat yield in response to different adaptation practices under (A) heat stress and (B) water stress in South Asia.

Figure 5. Effect size of adaptation practices on wheat yield under heat stress and water stress condition in South Asia.

Table 2. Effect of adaptation measures on wheat yield under heat and water stress (% change over control).

In studies related to water stress, adaptation options such as drought-tolerant varieties, CA, and additional irrigation positively affected yield in 100% of cases in the South Asian region (Figures 4B, 5). Yield increase was 24.7% (95% CI: 16.6-35.8%), with drought tolerant varieties, 37.8% (95% CI: 35.4-40.3%), with CA practices and 13.7% (95% CI: 7.8-19.9%), with application of additional irrigation (Table 2).

Performance of adaptation options in different AEZ

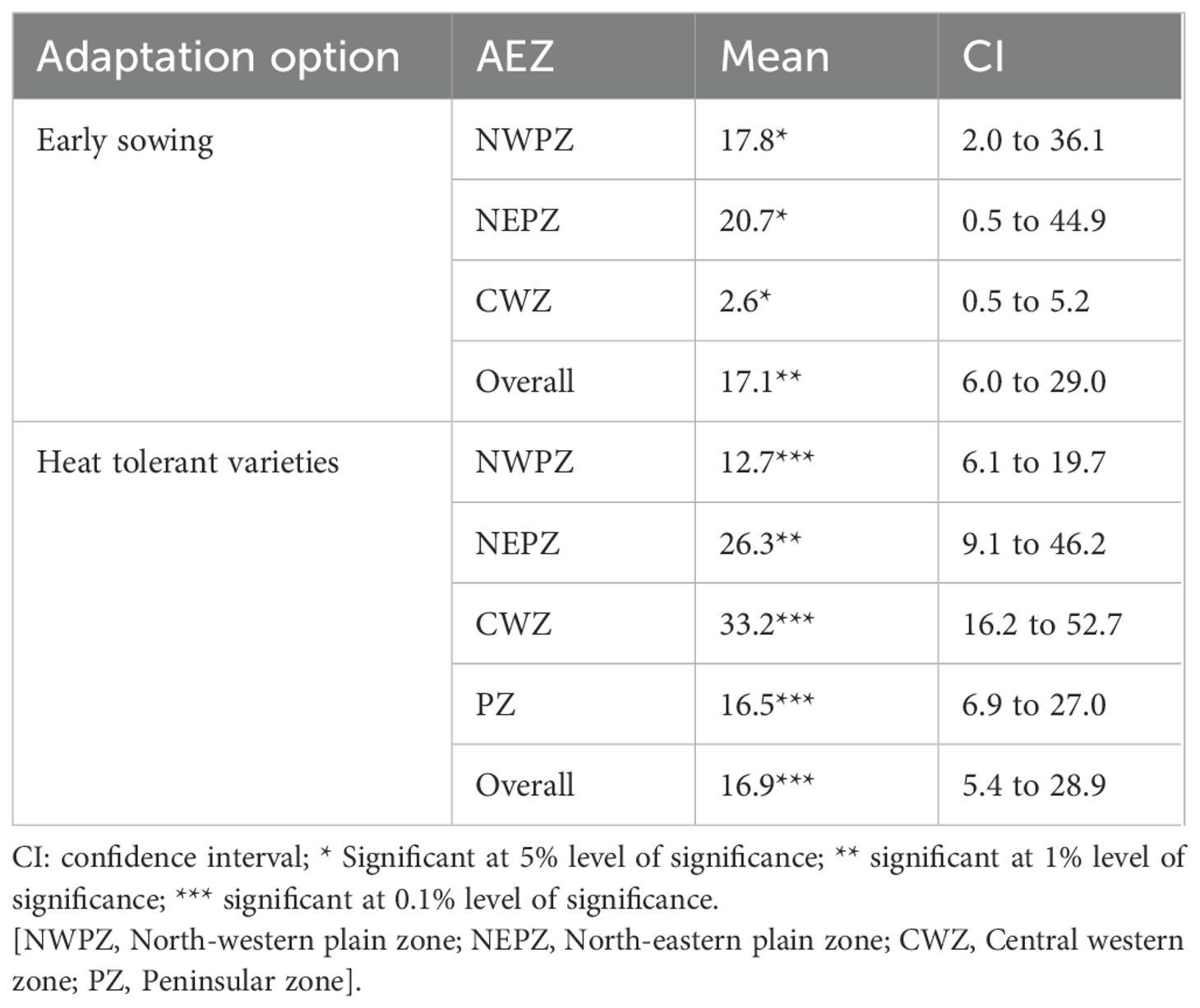

The spatial and temporal variability of climatic hazards across agroecological zones further complicates their management. The effect of different adaptation measures under heat stress condition varied with different AEZs. Growing heat tolerant varieties was found to be a good adaptation option with positive effect on yield in all AEZs. Results of different studies reported that, this adaptation measure increased yield by 33.2% (95% CI: 16.2-52.7%), 26.3% (95% CI: 9.1-46.2%), and 16.5% (95% CI: 6.9-27.0%), in CWZ, NEPZ and PZ respectively (Table 3). In NWPZ the yield increase with this technology was less (12.7%) (95% CI: 6.1-19.7%), due to the prevailing cooler temperature existing in this zone during the wheat growing period.

Table 3. Effect of adaptation measures on wheat yield under heat stress in different AEZ (% change over control).

Early sowing of wheat was found to have positive effect on wheat yield (Figure 6). In NEPZ this technology showed maximum yield advantage of 20.7% (95% CI: 0.5-44.9%), due to the existing higher winter temperature in this zone as compared to the others, indicating that this adaptation strategy can effectively mitigate yield losses associated with rising temperatures (Table 3). In NWPZ the increase in wheat yield with early sowing was 17.8% (95% CI: 2.0-36.1%), showing that by advancing the sowing window, the crop avoids exposure to terminal heat during the grain-filling stage, which is critical for maintaining productivity under warming conditions. In CWZ positive effect of early sowing on wheat yield was negligible (2.6%) (95% CI: 0.5-5.2%), (Table 3).

![Effect size of adaptation practices on wheat yield in different AEZs under heat stress condition in South Asia [NWPZ: North-western plain zone; NEPZ: North-eastern plain zone; CWZ: Central western zone; PZ: Peninsular zone].](https://www.frontiersin.org/files/Articles/1670235/fagro-07-1670235-HTML-r1/image_m/fagro-07-1670235-g006.jpg)

Figure 6. Effect size of adaptation practices on wheat yield in different AEZs under heat stress condition in South Asia. [NWPZ, North-western plain zone; NEPZ, North-eastern plain zone; CWZ, Central western zone; PZ, Peninsular zone].

Heterogeneity analysis

The heterogeneity analysis (Table 4) indicated that for heat stress, all three adaptation options had substantial variation in effect sizes among studies. Among them, early sowing exhibited the highest heterogeneity (I² = 91.1%), suggesting large variability in yield response, mainly due to differences in sowing dates, climatic conditions, and local management practices across studies. The heat-tolerant variety showed moderate heterogeneity (I² = 54.2%). Conservation agriculture (CA) under heat stress showed I² = 70.8%, but as the number of observations was low (n = 8), the estimate should be interpreted cautiously. For water stress, drought-tolerant varieties showed no significant heterogeneity (I² = 0), implying relatively consistent effects across studies. In contrast, CA and additional irrigation exhibited very high heterogeneity (I² = 82.3% and 89.0%, respectively), reflecting large differences in experimental conditions and irrigation management practices among studies. The estimated between-study variance (τ²) varied across adaptation measures, indicating differences in the consistency of true effects among studies. Under heat stress, early sowing showed the highest τ² (0.0194), suggesting large variability in true yield responses across environments, while heat-tolerant varieties (τ² = 0.011) showed moderate variability. Conservation agriculture under heat stress had very low between-study variance (τ² = 0.0001), though the small sample size limits interpretation. Under water stress, τ² was negligible for drought-tolerant varieties (0), but relatively higher for conservation agriculture (0.0177), indicating diverse outcomes across sites.

Overall, these results suggest that while the effectiveness of adaptation measures is generally positive, their impact varies widely across locations and management contexts. The high I² and τ² values for several adaptation options highlight the strong influence of local environmental and agronomic factors on adaptation outcomes, underscoring the need for AEZ-specific recommendations.

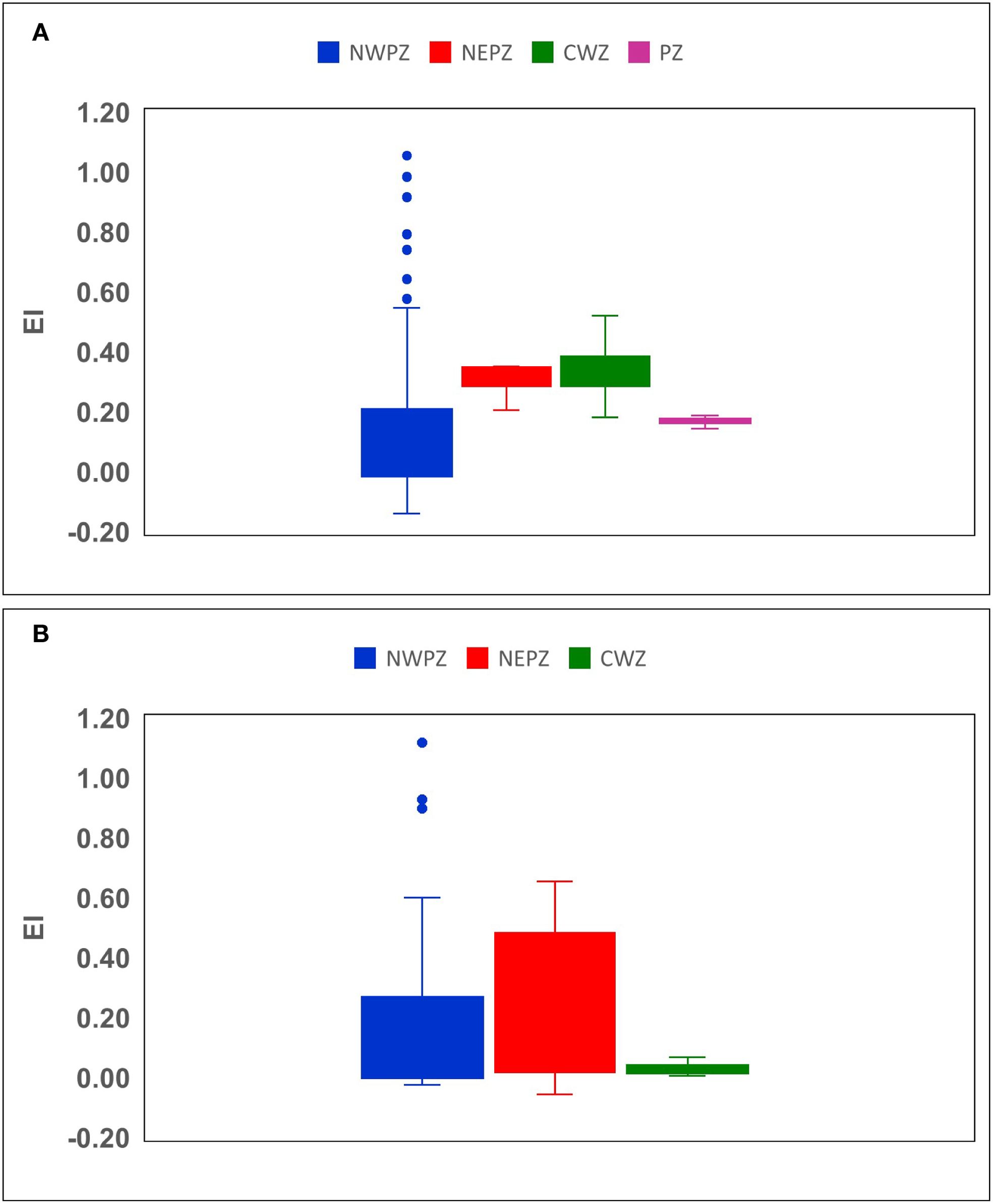

Effectiveness index of adaptation strategies

The Effectiveness Index (EI), calculated as described in the materials and methods section, was used to compare adaptation effectiveness across AEZs. EI of heat tolerant varieties was highest in CWZ (range 0.18 to 0.52 with a mean value of 0.33) followed by NEPZ (range 0.21 to 0.35 with a mean value of 0.31) (Figure 7A). On the other hand, EI of heat tolerant varieties was less in PZ (range 0.14 to 0.19 with a mean value of 0.17) and NWPZ (range -0.14 to 1.06 with a mean value of 0.14). The EI of early sowing was highest in NEPZ (range -0.06 to 0.66 with a mean value of 0.26) followed by NWPZ (range -0.02 to 1.12 with a mean value of 0.19), while it was very less (range 0.01 to 0.07 with a mean value of 0.03) in CWZ (Figure 7B).

Figure 7. Effectiveness Index (EI) of (A) heat tolerant varieties and (B) early sowing adaptation measures on wheat yield in different AEZs in South Asia. [NWPZ, North-western plain zone; NEPZ, North-eastern plain zone; CWZ, Central western zone; PZ, Peninsular zone].

In NEPZ, the correlation between EI of early sowing adaptation with seasonal maximum (Tmax) temperature was 0.94 and that of seasonal minimum (Tmin) temperature was 0.92 (Table 5). In NWPZ, the correlation of EI of early sowing with Tmax and Tmin were 0.41 and 0.21 respectively. Notably, NEPZ recorded the highest Tmax (30.5 °C) and Tmin (14.7 °C) among the three different zones practicing early sowing of wheat. For heat tolerant varieties, EI showed highest positive correlation with Tmax in CWZ (r = 0.49), followed by NEPZ (r = 0.30) (Table 5). In contrast, the correlation between EI of heat tolerant varieties and Tmin was highest in PZ (r = 0.56) where seasonal minimum temperature was maximum (16.3 °C) among the four different zones. Correlation between EI of heat tolerant varieties and Tmin was 0.49 in CWZ. NWPZ showed negative correlation between EI of heat tolerant varieties with Tmax and Tmin as the temperature in this zone is lower than the others.

Table 5. Correlation between effectiveness of adaptation measures under heat stress across zones with seasonal maximum and minimum temperature.

Discussion

Climatic stresses in wheat in South Asia

Achieving food security is a global challenge, increasingly strained by the effects of climate change. Crop failure is predominantly driven by climatic hazards like heat and water stress thereby limiting crop production. Wheat is a principal crop in South Asia and its production is constrained by these abiotic stresses as it is a sensitive crop (Singh et al., 2013). Heat stress, negatively impacts photosynthetic activity, disrupts plant-water relationships, decreases metabolic activity, increases pollen sterility, triggers production of reactive oxygen species in wheat (Sharma et al., 2012). Additionally, under heat stress, plants tend to mature early resulting in lower yield (Chakrabarti et al., 2021). As the availability of arable land is finite, productivity of wheat can be improved by optimizing agricultural practices (Dai et al., 2017). It is essential to determine the causes and extent of yield gaps in wheat to prioritize adaptation options and effectively design policies for sustainable agricultural development (McDonald et al., 2022). The bibliometric trends highlighted heat and water stress as the most frequently studied climatic hazards for wheat in South Asia, reflecting the region’s high vulnerability to temperature rise during the grain filling period (Mondal et al., 2013; Singh et al., 2011). The increasing focus on topics such as climate change, greenhouse gas emissions, and conservation agriculture in recent years underscores growing scientific and policy attention toward sustainable adaptation strategies in wheat systems.

Adaptation options for heat and water stress in South Asia

Based on the systematic literature review, we have identified certain adaptation options reported for wheat crop in South Asia. Adaptation options like stress tolerant varieties, adjustment of sowing time and CA were mainly prevalent in the publications. Addressing climate change and suggesting adaptation and mitigation strategies is a top policy priority leading to more availability of research grants from government and private organizations. More focus is on GHG emission and options like CA and C sequestration for mitigating climate change. Studies on modelling were more prevalent in later years due to the development of advanced crop and climate models as well as advancement in computational techniques.

Stress tolerance in crops need to be enhanced to meet the increasing food demands of the growing population. Developing and adopting resilient varieties with improved tolerance to heat, drought, and other abiotic stresses is essential to sustain productivity under the changing climatic conditions. Integrating these genotypes with suitable agronomic practices such as early sowing and conservation agriculture can further enhance resource use efficiency and yield stability. In our study, the most important adaptation options that improved wheat yield under heat stress condition were growing heat tolerant varieties, early sowing of the crop and adopting conservation agricultural practices (Figure 4a). In water stress conditions, effective adaptation strategies include, using drought tolerant varieties, implementing conservation agricultural practices and providing additional irrigation to the crop (Figure 4b). In order to cope up with such stresses, plants alter different physiological and biochemical processes and also alter morphological growth patterns (Farhad et al., 2023). Water stress often occurs alongside heat stress. Hence, breeding efforts to enhance both drought and heat tolerance in crops is important in hotter and drier environments (Comas et al., 2013). Developing wheat varieties with heat and drought tolerance is a key strategy for mitigating the climate change risks.

Stress tolerant varieties

In our analysis we found that growing heat and drought tolerant varieties of wheat were effective adaptation practices under heat and water stress condition in all wheat growing regions of South Asia (Figure 5). Our meta-analysis estimated an average yield increase of 13.2% with adoption of heat tolerant varieties across South Asia. This magnitude is broadly consistent with the global yield advantage of adaptation strategies in wheat (7-15%) reported by Challinor et al. (2014), but tends toward the higher end of that range. This could be attributed to the greater climatic sensitivity of wheat in South Asia, where higher baseline temperatures and frequent exposure to terminal heat amplify both the risks and the relative gains achievable through timely adaptation measures. Several researchers reported that, genetic improvements in wheat represent a key technological approach to climate change adaptation, potentially leading to development of new varieties with enhanced tolerance to high temperatures and terminal heat stress (Chauhan et al., 2012; Ladha et al., 2003). Such genetic advancements not only improve yield stability under stressful environments but also contribute to sustaining wheat productivity in regions increasingly vulnerable to climate variability. Earlier, simulation results also showed that stress-tolerant varieties can provide significant benefits to farmers in a changing climate. Heat tolerant varieties often exhibit certain physiological traits like better leaf cooling mechanisms, increased transpiration rates, which enable them to better withstand higher temperature (Hasanuzzaman et al., 2013). More efficient metabolic processes under stress condition lead to their resilience, ensuring lower risk of crop failure under heat stress conditions.

Although majority of the studies showed positive effect of stress tolerant varieties, but in certain cases it showed negative effect as well. The performance of stress tolerant varieties often depends on the climatic conditions and soil type. Certain genotypes with heat tolerance mechanisms might sacrifice their yield potential under mild conditions (Richards et al., 2010). There are reports that some heat tolerant lines show yield penalties under non-stress or cooler environments due to altered phenology or reduced biomass partitioning (Reynolds et al., 2017). Thus, when temperatures are not extreme, these traits can lead to lower yield compared to high-yielding but less tolerant varieties.

Early sowing

Besides stress tolerant varieties, early sowing of wheat crop by 7 to 10 days was identified as an adaptation option to escape the heat stress in South Asian region. Early onset of higher temperature coincides with the grain filling stage of wheat crop in many regions of South Asia thereby limiting wheat productivity in this region. Dubey et al. (2020) reported that, to counteract terminal heat stress, advancement of sowing date by 10–15 days resulted in yield gain to some extent. Temperature rise for 5 to 6 days at grain filling stage causes 20% yield loss compared to early sown crop which escapes the heat stress (Kumar and Rai, 2014). There are reports that, late sowing significantly decreased yield compared to normal sowing dates in crops (Dadrasi et al., 2024). Early sowing allows wheat to achieve longer vegetative growth and an optimal grain-filling period while efficiently utilizing residual soil moisture, resulting in greater biomass accumulation and higher yield potential. Moreover, it promotes better seedling emergence, whereas late sowing often exposes the crop to suboptimal temperatures during germination, adversely affecting growth and stand establishment (Carta et al., 2022). Sowing early also results in early flowering and maturity allowing the crop to escape heat and water stresses (Yau and Ryan, 2013; Zhang et al., 2019). Extended crop growth period under early sown condition, enables more extensive reproductive development and greater biomass accumulation, which enhances crop yield (Ghosh et al., 2024). Biomass of winter wheat crop in China was adversely affected by delayed sowing (Ma et al., 2018). These negative effects might be attributed to the reduced cumulative degree days in wheat under late sown condition (Yang et al., 2014), Hence, early planting could be a good option so that the grain filling stage falls in a relatively cooler climate (Farooq et al., 2011).

In some of the studies early sowing did not show beneficial effects on crop yield as the benefits of early sowing are highly dependent on the weather, soil condition and management practices followed. Early sown crop might experience suboptimal germination and emergence due to higher soil temperatures at planting (Hunt et al., 2019). Moreover, the advantage of early sowing may diminish under irrigated and high input systems, where temperature stress during grain filling is less critical, and yield depends more on nitrogen availability and canopy management (Reynolds et al., 2017).

Conservation agriculture

Several research papers highlighted the benefits of conservation agricultural (CA) practices like, zero tillage, crop residue retention, precision nitrogen management etc. on yield of wheat crop. In most of these resources conserving agricultural practices, yield of wheat crop was found to be more than that of conventional agricultural practices. In our analysis, CA has significantly improved wheat yield under both heat and water stress condition. But the beneficial impact of CA practices was very high under water stress condition. Improved soil moisture under CA ensures better water availability during critical growth stages. Sustained water supply enhances photosynthesis, nutrient uptake, that leads to higher and more stable wheat yields under water limited conditions. According to, Hobbs et al. (2007) conservation agricultural technologies in the rice-wheat cropping system is an eco-friendly, and sustainable option providing economic viability to the system. Several studies have highlighted that CA practices, improve the adaptive capacity of crops to climatic stresses (Corbeels et al., 2020; Rusinamhodzi et al., 2011). Retention of crop residues in CA, acts as a mulch and reduces soil temperature and enhances soil water content (Horton et al., 1996) which is beneficial for crops under both heat and water stress condition. Zero tillage in wheat saves input cost and also improves yield and soil fertility (Chauhan et al., 2002; Mohanty et al., 2007). Adopting zero tillage with residue retention on the soil in several locations in Africa, led to increased infiltration rate in soil thereby increasing soil water content and improving crop yield (Thierfelder and Wall, 2009, Thierfelder et al., 2012). Another advantage of CA practices in the rice-wheat system is that it allows earlier wheat sowing (Aryal et al., 2016) compared to conventional tillage methods, enabling the crop to achieve optimal yields under terminal heat stress conditions. Applying one additional irrigation was also found to be beneficial for wheat crop under water stress condition in the study. This additional irrigation at the critical growth stage of grain filling helped in mitigating the effects of drought and water shortage, prevented wilting of the crop and improved growth and yield of the crop.

Suitability of adaptation options in different agroecological zones

As the climate is so diverse in South Asian region the suitability and effectiveness of the adaptation options for sustaining wheat yield might also vary. In the current study, growing heat-tolerant varieties was found to be an effective adaptation option across all AEZs of South Asia. (Table 4). But the effectiveness of this adaptation option was higher in CWZ which is facing significant warming during the post-anthesis period (Jat et al., 2018), and NEPZ where the seasonal mean temperature during wheat growth period is increasing. In NWPZ having humid subtropical climate with cool winters the effectiveness of stress tolerant varieties was less and there is a negative correlation between the EI values and seasonal maximum and minimum temperatures. This might be attributed to the fact that under cooler seasonal temperature in this zone, the adaptive traits of those varieties might not express effectively under lower heat stress. Under sub-optimal low-stress environments, heat-tolerant genotypes often exhibit physiological trade-offs such as delayed phenological progression, reduced grain-filling rate, and lower radiation-use efficiency (Reynolds et al., 2010; Lobell et al., 2013). These varieties are typically bred for high canopy temperature depression and stay-green traits, which may confer limited yield advantage or even mild penalties when heat stress is absent. A strong positive correlation between the EI of the heat-tolerant varieties and seasonal maximum and minimum temperatures was observed in the CWZ, indicating that the success of this adaptation strategy in this zone was largely attributable to its ability to mitigate heat stress in the region.

A key finding from the analysis revealed a strong positive correlation between the EI and seasonal minimum temperatures in the PZ, characterized by mild winters. The relatively higher minimum temperatures in this zone may explain the strong positive correlation observed between the EI and seasonal minimum temperature, suggesting that the adaptation option performed increasingly well as night-time temperatures rose in this region. Increasing night time temperatures pose a unique threat to crop production in many regions (Sadras and Dreccer, 2015). Increase in night temperatures cause rapid accumulation of growing degree resulting in early maturity and reduced wheat yield (Lutt et al., 2016). This accelerated phenological development shortens the grain-filling period, leading to smaller kernels and ultimately lowering overall grain quality and productivity. Hence, heat-tolerant varieties are likely to be more effective in regions experiencing higher night time temperatures.

In our analysis, early sowing showed positive effect on wheat yield in NWPZ, NEPZ and CWZ. But the effectiveness of this adaptation technology was found to highest in NEPZ. There exists a very high correlation between the effectiveness of early sowing technology and seasonal maximum and minimum temperatures in NEPZ. The higher seasonal temperatures and greater yield gaps in wheat observed in the eastern Gangetic Plains (McDonald et al., 2022) contributed to the greater yield advantage of early-sown crops under heat stress conditions.

The superior performance of early sowing in the NEPZ can be attributed to the avoidance of terminal heat during the critical grain filling stage. Early planting allows the crop to complete flowering and grain filling before the onset of high post-anthesis temperatures. Paudel et al. (2023) also proposed, early sowing as an important adaptation option to reduce the negative effect of terminal heat stress in wheat in the Indo-Gangetic Plains of South Asia. There are reports that advancement of wheat sowing by one week could result in 5% yield improvement in the western Indo Gangetic Plain region which lies in NWPZ (Lobell et al., 2011).

Most of the literature on CA practices in wheat was found in the NWPZ of South Asia. This might be attributed to several factors, including the region’s prominence as a major wheat-producing area with intensive cropping systems. The issues of groundwater depletion, soil degradation, and residue burning have prompted research on sustainable alternatives such as zero tillage, residue retention, and crop diversification. Additionally, the relatively better infrastructure and adoption-ready farming communities in this zone likely supported the testing, refinement, and wider dissemination of CA technologies.

Conclusions

A systematic literature review in wheat crop was done to identify the climatic hazards, risks and suitable adaptation options in South Asian region. Bibliometric analysis of the studies revealed that, heat stress as well as water stress are major climatic hazards affecting wheat crop of this region. The topic of terminal heat stress was highlighted in later publications, indicating its growing importance in subsequent years. Among the different adaptation strategies, CA was mentioned the most followed by stress tolerant varieties, sowing time and water management. This suggests that these are the key adaptation options for wheat crop in the study region. Meta-analysis provided new evidence of the benefits of different adaptation practices on wheat yield under climatic stresses in different agro-ecological regions. Under heat stress condition, adoption of heat tolerant varieties, early sowing and CA practices increased the yield by 13.2% (95% CI: 5.5-21.5%), 16.3% (95% CI: 6.2-27.4%) and 8.6% (95% CI: 6.5-11.1%), respectively while in water stress, yield improvement was 24.7% (95% CI: 16.6-35.8%) with growing drought tolerant varieties, 37.8% (95% CI: 35.4-40.3%) with CA practices and 13.7% (95% CI: 7.8-19.9%)with application of additional irrigation. Based on the pooled meta-analysis, the overall effectiveness of growing heat and drought tolerant varieties across agroecological zones followed the order CWZ > NEPZ > PZ > NWPZ. The CWZ and NEPZ exhibited the greatest yield gains, driven by the strong positive response to heat-tolerant varieties. In case of early sowing of the crop the effectiveness will follow the order NEPZ > NWPZ > CWZ. The findings from this study provide an evidence base for developing targeted, agroecological zone-differentiated policy interventions and investment priorities. The findings of this study provide an evidence base for region-specific policy design in South Asia. Policy interventions could include incentive schemes for early sowing, to help farmers adopt climate-resilient practices. In regions where heat-tolerant varieties show strong effectiveness, public breeding programs should prioritize these genotypes to enhance regional adaptation capacity. Moreover, strengthened agricultural extension services and climate information delivery systems tailored to each AEZ can support timely decision-making at the farm level. Such integrated policy actions and tailored policies will facilitate effective implementation of adaptation technologies and can help minimize future wheat yield losses while enhancing livelihood and food security across South Asia.

Limitations and future research needs

There are certain limitations to this study. Variations in methodologies and models across primary studies may have influenced data quality and comparability. Although publication bias cannot be ruled out, the limited number of effect-size estimates constrained the use of formal diagnostics such as funnel plots or Egger’s test. The analysis primarily addressed biophysical and agronomic dimensions, while socio-economic and institutional factors—such as technology access, cost, and policy support—also influence adoption and should be integrated in future research. Moreover, this study focused on yield response, although climatic stresses can also affect crop quality and soil–plant–environment interactions. Finally, due to limited literature, the effectiveness of adaptation options under combined heat and water stress could not be evaluated. Future research should include multi-location experiments that assess concurrent stresses and generate more consistent data across agroecological zones to enhance the robustness of meta-analyses.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author contributions

BC: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AB: Funding acquisition, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. AD: Data curation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. M.: Data curation, Formal analysis, Software, Writing – original draft. NJ: Methodology, Writing – review & editing. VVK: Methodology, Writing – review & editing. ARRC: Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. PKA: Conceptualization, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, and/or publication of this article. The authors acknowledge the support provided by ACASA project funded by BISA-CIMMYT for carrying out this work.

Acknowledgments

Authors are thankful to ICAR-Indian Agricultural Research Institute, New Delhi for providing support for carrying out this research.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fagro.2025.1670235/full#supplementary-material

Abbreviations

AEZ, Agro-Ecological Zone; CA, Conservation Agriculture; CH4, Methane; CO2, Carbon dioxide; CV, Coefficient of Variation; CWZ, Central Western Zone; EI, Effectiveness Index; GHG, Greenhouse Gas; IPCC, Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; N2O, Nitrous oxide; NEPZ, North-Eastern Plain Zone; NWPZ, North-Western Plain Zone; PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses; PZ, Peninsular Zone; RR, Response Ratio; SA, South Asia; SLR, Systematic Literature Review; Tmax, Seasonal Maximum Temperature; Tmin, Seasonal Minimum Temperature.

References

Akhtar N., Ilyas N., Mashwani Z.-U.-R., Hayat R., Yasmin H., Noureldeen A., et al. (2021). Synergistic effects of plant growth promoting rhizobacteria and silicon dioxide nano-particles for amelioration of drought stress in wheat. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 166, 160–176. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2021.05.039, PMID: 34116336

Aryal J. P., Sapkota T. B., Khurana R., Khatri−Chhetri A., Rahut D. B., and Jat M. L. (2020). Climate change and agriculture in South Asia: adaptation options in smallholder production systems. Environ. Dev. Sustainabil. 22, 5045–5075. doi: 10.1007/s10668-019-00414-4

Aryal J. P., Sapkota T. B., Stirling C. M., Jat M. L., Jat H. S., Rai M., et al. (2016). Conservation agriculture-based wheat production better copes with extreme climate events than conventional tillage-based systems: A case of untimely excess rainfall in Haryana, India. Agricult. Ecosyst. Environ. 233, 325–335. doi: 10.1016/j.agee.2016.09.013

Asseng S., Ewert F., Martre P., Rotter R. P., Lobell D. B., Cammarano D., et al. (2015). Rising temperatures reduce global wheat production. Nat. Clim. Change 5, 143–147. doi: 10.1038/nclimate2470

Bhatia A., Pathak H., Aggarwal P. K., and Jain N. (2010). Trade-off between productivity enhancement and global warming potential of rice and wheat in India. Nutrient. Cycling. Agroecosyst. 86, 413–424. doi: 10.1007/s10705-009-9304-5

Borenstein M., Hedges L. V., Higgins J. P. T., and Rothstein H. R. (2020). Introduction to Meta-Analysis (Chichester, West Sussex, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd).

Carta A., Fern´andez-Pascual E., Gioria M., Müller J. V., Rivi`ere S., Rosbakh S., et al. (2022). Climate shapes the seed germination niche of temperate flowering plants: a meta-analysis of European seed conservation data. Ann. Bot. 129, 775–786. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcac037, PMID: 35303062

Chakrabarti B., Bhatia A., Pramanik P., Singh S. D., Jatav R. S., Das Saha N., et al. (2021). Changes in thermal requirements, growth and yield of wheat under the elevated temperature. Indian J. Agric. Sci. 91, 435–439. doi: 10.56093/ijas.v91i3.112527

Challinor A. J., Watson J., Lobell D. B., Howden S. M., Smith D. R., and Chhetri N. (2014). A meta-analysis of crop yield under climate change and adaptation. Nat. Clim. Change 4, 287–291. doi: 10.1038/nclimate2153

Chauhan B. S., Mahajan G., Sardana V., Timsina J., and Jat M. L. (2012). “Chapter six - productivity and sustainability of the rice–wheat cropping system in the indo-gangetic plains of the Indian subcontinent: problems, opportunities, and strategies,” In Sparks D. L. (Ed.), Advances in Agronomy, vol. 117 (Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA: Academic Press), pp. 315–369. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-394278-4.00006-4

Chauhan B. S., Yadav A., and Malik R. K. (2002). “Zero tillage and its impact on soil properties: a brief review,” in Herbicide Resistance Management and Zero Tillage in Rice-Wheat Cropping System. Eds. Malik R. K., Balyan R. S., Yadav A., and Pahwa S. K. (Chaudhary Charan Singh Haryana Agricultural University, Hisar, India), 109–114.

Comas L. H., Becker S. R., Cruz V. M. V., Byrne P. F., and Dierig D. A. (2013). Root traits contributing to plant productivity under drought. Front. Plant Sci. 4, 1–16. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2013.00442, PMID: 24204374

Corbeels M., Naudin K., Whitbread A. M., Kühne R., and Letourmy P. (2020). Limits of conservation agriculture to overcome low crop yields in sub-Saharan Africa. Nat. Food 1, 447–454. doi: 10.1038/s43016-020-0114-x

Dadrasi A., Soltani E., Makowski D., and Lamichhane J. R. (2024). Does shifting from normal to early or late sowing dates provide yield benefits? A global meta-analysis. Field Crops Res. 318, 109600. doi: 10.1016/j.fcr.2024.109600

Dai X., Wang Y., Dong X., Qian T., Yin L., Dong S., et al. (2017). Delayed sowing can increase lodging resistance while maintaining grain yield and nitrogen use efficiency in winter wheat. Crop J. 5, 541–552. doi: 10.1016/J.CJ.2017.05.003

Dar M. H., Showkat A., Waza S. S., Najam W., Zaidi S. N., Mosharaf H., et al. (2020). Drought tolerant rice for ensuring food security in Eastern India. Sustainability 12, 2214. doi: 10.3390/su12062214

Datta P., Behera B., and Rahut D. B. (2022). Climate change and Indian agriculture: A systematic review of farmers’ perception, adaptation, and transformation. Environ. Challenges. 8, 100543. doi: 10.1016/j.envc.2022.100543

Devate N. B., Krishna H., Parmeshwarappa S. K. V., Manjunath K. K., Chauhan D., Singh S., et al. (2022). Genome-wide association mapping for component traits of drought and heat tolerance in wheat. Front. Plant Sci. 13. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2022.943033, PMID: 36061792

Donthu N., Kumar S., Pattnaik D., and Lim W. M. (2021). A bibliometric retrospection of marketing from the lens of psychology: Insights from Psychology & Marketing. Psychol. Marketing. 38, 834–865. doi: 10.1002/mar.21472

Dubey R., Pathak H., Chakrabarti B., Singh S. D., Gupta D. K., and Harit R. C. (2020). Impact of terminal heat stress on wheat yield in India and options for adaptation. Agric. Syst. 181, 102826. doi: 10.1016/j.agsy.2020.102826

Dubey R., Pathak H., Singh S. D., Chakravarti B., Thakur A. K., and Fagodia R. K. (2019). Impact of sowing dates on terminal heat tolerance of different wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) cultivars. Natl. Acad. Sci. Lett. 42, 445–449. doi: 10.1007/s40009-019-0786-7

Farhad M., Kumar U., Tomar V., Bhati P. K., Krishnan J. N., Kishowar-E-Mustarin, et al. (2023). Heat stress in wheat: a global challenge to feed billions in the current era of the changing climate. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 7. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2023.1203721

Farooq M., Bramley H., Palta J. A., Kadambot H., and Siddique M. (2011). Heat stress in wheat during reproductive and grain-filling phases. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 30, 491–507. doi: 10.1080/07352689.2011.615687

Ghosh A., Pandey B., Agrawal M., and Agrawal S. B. (2024). Assessing the effects of early and timely sowing on wheat cultivar HD 2967 under current and future tropospheric ozone scenarios. Environ. Exp. Bot. 228, 106018. doi: 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2024.106018

Hasanuzzaman M., Nahar K., Alam M. M., Roychowdhury R., and Fujita M. (2013). Physiological, biochemical, and molecular mechanisms of heat stress tolerance in plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 14, 9643–9684. doi: 10.3390/ijms14059643, PMID: 23644891

Hernandez-Ochoa I. M., Pequeno D. N. L., Reynolds M., Babar Md A., Sonder K., Milan A. M., et al. (2019). Adapting irrigated and rainfed wheat to climate change in semi-arid environments: Management, breeding options and land use change. Eur. J. Agron. 109, 125915. doi: 10.1016/j.eja.2019.125915. ISSN 1161-0301.

Higgins J. P. T., Thompson S. G., Deeks J. J., and Altman D. G. (2003). Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 327, 557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557, PMID: 12958120

Hobbs P. R., Sayre K., and Gupta R. (2007). The role of conservation agriculture in sustainable agriculture. Philos. Trans. R. Soc Lond. B. Biol. Sci. 363, 543–555. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2007.2169, PMID: 17720669

Horton R., Bristow K. L., Kluitenberg G. J., and Sauer T. J. (1996). Crop residue effects on surface radiation and energy balance — review. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 54, 27–37. doi: 10.1007/BF00863556

Hunt J. R., Kirkegaard J. A., Evans J. R., Trevaskis B., and Fletcher A. (2019). Early sowing systems can boost Australian wheat yields despite recent climate change. Nat. Climate Change 9, 244–247. doi: 10.1038/s41558-019-0417-9

IPCC (2019). “Summary for policymakers,” in Climate Change and Land: An IPCC special report on climate change, desertification, land degradation, sustainable land management, food security, and greenhouse-gas fluxes in terrestrial ecosystems. Eds. Shukla P. R., Skea J., Calvo Buendia E., MassonDelmotte V., Pörtner H.-O., Roberts D. C., Zhai P., Slade R., Connors S., van Diemen R., Ferrat M., Haughey E., Luz S., Neogi S., Pathak M., Petzold J., Pereira J.P., Vyas P., Huntley E., Kissick K., Belkacemi M., and Malley J. Geneva, Switzerland: IPCC.

Ishtiaq M., Maqbool M., Muzamil M., Casini R., Alataway A., Dewidar A. Z., et al. (2022). Impact of climate change on phenology of two heat-resistant wheat varieties and future adaptations. Plants 11, 1180. doi: 10.3390/plants11091180, PMID: 35567180

Jat R. K., Singh P., Jat M. L., Dia M., Sidhu H. S., Jat S. L., et al. (2018). Heat stress and yield stability of wheat genotypes under different sowing dates across agro-ecosystems in India. Field Crops Res. 218, 33–50. doi: 10.1016/j.fcr.2017.12.020

Jatoi W. A., Abbasi A. B., Memon S., Rind R. A., and Abbasi Z. A. (2021). Effect of heat stress for agro-economic traits in bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) genotypes. Pakistan J. Sci. Ind. Res. Ser. B.: Biol. Sci. 64B, 274–282. doi: 10.52763/PJSIR.BIOL.SCI.64.3.2021.274.282

Kitchenham B. and Charters S. (2007). “Guidelines for performing systematic literature reviews in software engineering (Version 2.3),” in Technical Report EBSE-2007-01, vol. 5. (Keele, Staffs, ST5 5BG, UK and Durham, UK: Software Engineering Group, School of Computer Science and Mathematics, Keele University and Department of Computer Science, University of Durham).

Kelkar U. and Bhadwal S. (2007). “South Asian regional study on climate change impacts and adaptation: implications for human development,” in Human Development Report Office, Occasional Paper (New York, NY, USA: United Nations Development Programme).

Khan H., Mamrutha H. M., Mishra C. N., Krishnappa G., Sendhil R., Parkash O., et al. (2023). Harnessing High Yield Potential in Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) under Climate Change Scenario. Plants 12, 1271. doi: 10.3390/plants12061271, PMID: 36986959

Köppen W. and Geiger R. (1930). Handbuch der klimatologie Vol. 1 (Berlin, Germany: Gebrüder Borntræger).

Kumar N. S., Aggarwal P. K., Swaroopa Rani D. N., Saxena R., Chauhan N., and Jain S. (2014). Vulnerability of wheat production to climate change in India. Clim. Res. 59, 173–187. doi: 10.3354/cr01212

Kumar R. R. and Rai R. D. (2014). Can wheat beat the heat: understanding the mechanism of thermos tolerance in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) a review. Cereal Res. Commun. 42, 1–18. doi: 10.1556/CRC.42.2014.1.1

Kumari M., Pudake R. N., Singh V. P., and Joshi A. K. (2013). Association of staygreen trait with canopy temperature depression and yield traits under terminal heat stress in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Euphytica 190, 87–97. doi: 10.1007/s10681-012-0780-3

Ladha J. K., Dawe D., Pathak H., Padre A. T., Yadav R. L., Singh B., et al. (2003). How extensive are yield declines in long-term rice–wheat experiments in Asia? Field Crops Res. 81, 159–180. doi: 10.1016/S0378-4290(02)00219-8. ISSN 0378-4290.

Li J., Ma W., and Zhu H. (2024). A systematic literature review of factors influencing the adoption of climate−smart agricultural practices. Mitig. Adapt. Strat. Glob. Change 29, 2. doi: 10.1007/s11027-023-10098-x

Lobell D. B., Hammer G. L., McLean G., Messina C., Roberts M. J., and Schlenker W. (2013). The role of heat tolerance in determining wheat yields under climate change. Nat. Climate Change 3, 487–492.

Lobell D. B., Schlenker W., and Costa-Roberts J. (2011). Climate trends and global crop production since 1980. Science 333, 616–620. doi: 10.1126/science.1204531, PMID: 21551030

Lutt N., Jeschke M., and Strachan S. D. (2016). High night temperature effects on corn yield. DuPont Pioneer Agronomy Sciences. Crop Insights 26, 16.

Ma S. C., Wang T. C., Guan X. K., and Zhang X. (2018). Effect of sowing time and seeding rate on yield components and water use efficiency of winter wheat by regulating the growth redundancy and physiological traits of root and shoot. Field Crop Res. 221, 166–174. doi: 10.1016/J.FCR.2018.02.028

Mahfuz Bazzaz M., Hossain A., Khaliq Q. A., Abdul Karim M., Farooq M., and Teixeira Da Silva J. A. (2019). Assessment of tolerance to drought stress of thirty-five bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) genotypes using boxplots and cluster analysis. Agricult. Conspectus. Scientificus. 84, 333–345.

Makowski D., Piraux F., and Brun F. (2019). From experimental network to meta-analysis methods and applications with R for agronomic and environmental sciences (Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer Nature B.V). doi: 10.1007/978-94-024-1696-1

McDonald A. J., Balwinder-Singh, Keil A., Srivastava A., Craufurd P., Kishore A., et al. (2022). Time management governs climate resilience and productivity in the coupled rice–wheat cropping systems of eastern India. Nat. Food 3, 542–551. doi: 10.1038/s43016-022-00549-0, PMID: 37117949

Mohanty M., Painuli D. K., Misra A. K., and Ghosh P. K. (2007). Soil quality effects of tillage and residue under rice-wheat cropping on a Vertisol in India. Soil Tillage. Res. 92, 243–250. doi: 10.1016/j.still.2006.03.005

Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D. G., and The PRISMA Group (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 6, e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097, PMID: 19621072

Mondal S., Singh R. P., Crossa J., Huerta-Espino J., Sharma I., Chatrath R., et al. (2013). Earliness in wheat: a key to adaptation under terminal and continual high temperature stress in South Asia. Field Crop Res. 151, 19–26. doi: 10.1016/j.fcr.2013.06.015

Nawaz A., Farooq M., Nadeem F., Siddique K. H. M., and Lal R. (2019). Rice–wheat cropping systems in South Asia: Issues, options and opportunities. Crop Past. Sci. 70, 395–427. doi: 10.1071/CP18383

Ostmeyer T., Parker N., Jaenisch B., Alkotami L., Bustamante C., and Jagadish S. K. (2020). Impacts of heat, drought, and their interaction with nutrients on physiology, grain yield, and quality in field crops. Plant Physiol. Rep. 25, 549–568. doi: 10.1007/s40502-020-00538-0

Pal K. K., Islam A., Uddin N., Haque S., and Hossain A. (2022). Culm reserves and its remobilization to grain for minimization of grain yield loss in drought-resistant wheat cultivars. Res. Crops 23, 26–32. doi: 10.31830/2348-7542.2022.005

Paudel G. P., Chamberlin J., Balwinder-Singh, Maharjan S., Nguyen T. T., Craufurd P., et al. (2023). Insights for climate change adaptation from early sowing of wheat in the Northern Indo-Gangetic Basin. Int. J. Disaster. Risk Reduct. 92, 103714. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdrr.2023.103714. ISSN 2212-4209.

Philibert A., Loyce C., and Makowski D. (2012). Assessment of the quality of meta-analysis in agronomy. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 148, 72–82. doi: 10.1016/j.agee.2011.12.003

Qin X., Huang T., Lu C., Dang P., Zhang M., Guan X. K., et al. (2021). Benefits and limitations of straw mulching and incorporation on maize yield, water use efficiency, and nitrogen use efficiency. Agric. Water Manage. 256, 107128. doi: 10.1016/j.agwat.2021.107128

Rehman H.u., Tariq A., Ashraf I., Ahmed M., Muscolo A., Basra S. M. A., et al. (2021). Evaluation of physiological and morphological traits for improving spring wheat adaptation to terminal heat stress. Plants 10, 455. doi: 10.3390/plants10030455, PMID: 33670853

Reynolds M. P., Foulkes M. J., Slafer G. A., Berry P., Parry M. A. J., Snape J. W., et al. (2010). Raising yield potential in wheat. J. Exp. Bot. 61, 3499–3508. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erp016, PMID: 19363203

Reynolds M. P., Pask A. J. D., Mullan D. M., Chapman S. C., Vargas M., Braun H.-J., et al. (2017). Raising yield potential of wheat. III. Optimizing genetic design for climate resilience. J. Exp. Bot. 68, 381–400.

Richards R. A., Rebetzke G. J., Condon A. G., and van Herwaarden A. F. (2010). Breeding for improved water productivity in temperate cereals: phenotyping, quantitative trait loci, markers and the selection environment. Funct. Plant Biol. 37, 85–97. doi: 10.1071/FP09219

Rusinamhodzi L., Corbeels M., Wijk M. T., Rufino M. C., Nyamangara J., and Giller K. E. (2011). A meta-analysis of long-term effects of conservation agriculture on maize grain yield under rain-fed conditions. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 31, 657–673. doi: 10.1007/s13593-011-0040-2

Sadras V. and Dreccer M. F. (2015). Adaptation of wheat, barley, canola, field pea and chickpea to the thermal environments of Australia. Crop Pasture Sci. 66, 1137–1150. doi: 10.1071/CP15129

Shah M. A., Farooq M., and Hussain M. (2016). Productivity and profitability of cotton–wheat system as influenced by relay intercropping of insect resistant transgenic cotton in bed planted wheat. Eur. J. Agron. 75, 33–41. doi: 10.1016/j.eja.2015.12.014

Sharma P., Jha A. B., Dubey R. S., and Pessarakli M. (2012). Reactive oxygen species, oxidative damage, and antioxidative defense mechanism in plants under stressful conditions. J. Bot. 2012, 1–26. doi: 10.1155/2012/217037

Sharma S., Padbhushan R., and Kumar U. (2019). Integrated nutrient management in rice-wheat cropping system: evidence on sustainability in the Indian subcontinent through meta-nalysis. Agronomy 9, 71. doi: 10.3390/agronomy9020071

Singh S. D., Chakrabarti B., Muralikrishna K. S., Chaturvedi A. K., Kumar V., Mishra S., et al. (2013). Yield response of important field crops to elevated air temperature and CO2 levels. Indian J. Agric. Sci. 83, 1009–1012.

Singh K., Sharma S. N., and Sharma Y. (2011). Effect of high temperature on yield attributing traits in bread wheat Bangladesh J. Agril. Res. 36, 415–426. doi: 10.3329/bjar.v36i3.9270

Sohail M., Hussain I., Qamar M., Tanveer S. K., Abbas S. H., Ali Z., et al. (2020). Evaluation of spring wheat genotypes for climatic adaptability using canopy temperature as physiological indicator. Pakistan J. Agric. Res. 33, 89–96. doi: 10.17582/journal.pjar/2020/33.1.89.96

Thierfelder C., Cheesman S., and Rusinamhodzi L. (2012). A comparative analysis of conservation agriculture systems: benefits and challenges of rotations and intercropping in Zimbabwe. Field Crops Res. 137, 237–250. doi: 10.1016/j.fcr.2012.08.017

Thierfelder C. and Wall P. C. (2009). Effects of conservation agriculture techniques on infiltration and soil water content in Zambia and Zimbabwe. Soil Tillage. Res. 105, 217–227. doi: 10.1016/j.still.2009.07.007

Vervoort J. M., Thornton P. K., Kristjanson P., Förch W., Ericksen P. J., Kok K., et al. (2014). Challenges to scenario-guided adaptive action on food security under climate change. Global Environ. Change. 28, 383–394. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2014.03.001

World Health Organization (WHO) (2020). UNICEF/WHO/The World Bank Group Joint Child Malnutrition Estimates: levels and trends in child malnutrition, key findings of the 2020 edition. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

Yang Y., Li T., Pokharel P., Liu L., Qiao J., Wang Y., et al. (2022). Global effects on soil respiration and its temperature sensitivity depend on nitrogen addition rate. Soil Biol. Biochem. 174, 108814. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2022.108814

Yang N., Pan X., Zhang L., Wang J., Dong W., Hu Q., et al. (2014). Optimal sowing dates improving yield, water and nitrogen use efficiencies of spring wheat in agriculture and pasture ecotone. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 30, 81–90.

Yau S. K. and Ryan J. (2013). Differential impacts of climate variability on yields of rainfed barley and legumes in semi-arid Mediterranean conditions. Arch. Agron. Soil Sci. 59, 1659–1674. doi: 10.1080/03650340.2013.766322

Keywords: adaptation options, climate change, heat stress, systematic literature review, water stress, wheat

Citation: Chakrabarti B, Bhatia A, Deo A, Maitreya, Jain N, Kumari VV, Chitiprolu ARR and Aggarwal PK (2025) Climatic stresses and adaptation options for South Asian wheat: A systematic literature review. Front. Agron. 7:1670235. doi: 10.3389/fagro.2025.1670235

Received: 21 July 2025; Accepted: 12 November 2025; Revised: 06 November 2025;

Published: 27 November 2025.

Edited by:

Tafadzwanashe Mabhaudhi, University of London, United KingdomReviewed by:

Rajib Roychowdhury, Volcani Center, IsraelImane El Houssni, Mohammed V University, Morocco

Tove Ortman, Norwegian Institute of Bioeconomy Research, Norway

Copyright © 2025 Chakrabarti, Bhatia, Deo, Maitreya, Jain, Kumari, Chitiprolu and Aggarwal. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: A. Bhatia, YXJ0aWJoYXRpYS5pYXJpQGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

Bidisha Chakrabarti

Bidisha Chakrabarti A. Bhatia

A. Bhatia Aniket Deo2

Aniket Deo2 N. Jain

N. Jain Venugopalan Visha Kumari

Venugopalan Visha Kumari P. K. Aggarwal

P. K. Aggarwal