- Department of Veterinary Medicine, Working Group for Applied Ethology and Animal Behavior Therapy, Justus-Liebig-University Giessen, Giessen, Germany

This study examines the relationship between livestock farmers’ attitudes toward their pigs and the pigs’ welfare, housing conditions, and occurrence of behavioral abnormalities and health problems. The existing system of livestock farming in Germany has been the subject of considerable criticism due to the conflict between economic goals and ethical standards. Despite the existence of studies that examine the human-animal relationship with regard to species-appropriate animal husbandry and the welfare of farm animals, the present study focuses on the association of pig farmers’ basic attitudes on the behavior and welfare of pigs and the respective housing conditions. This study aims to investigate the relationship between the basic attitudes of livestock farmers, the behavior of pigs, husbandry conditions, disease incidence, and the relationship between humans and pigs. The underlying hypothesis of the study is that there is a significant correlation between the basic attitude of pig farmers and the behavior of the pigs, the housing conditions, the occurrence of diseases, and human-animal relationships. In order to respond to the research question, a quantitative study was conducted in the form of an anonymous online survey of 485 German pig farmers. The results of the study indicate the presence of three basic attitudes among pig farmers: utilitarian, emotional, and a combination of utilitarianism, naturalism, and moralism. Furthermore, the results indicate that there are statistical correlations between the attitudes of livestock farmers and certain behaviors and the health status of pigs. It was found that pigs kept by livestock farmers with a utilitarian attitude showed significantly more signs of abnormal and defensive behavior and health problems than pigs kept by livestock farmers with an emotional attitude. The results of this study contribute to our understanding of pig welfare by highlighting correlations between behavior, health, human-animal relationships, and housing conditions. In addition, the results could help raise awareness of housing conditions and the relationship between farm animals and humans, and emphasize the importance of pig behavior.

1 Introduction

The domestication of pigs, which began more than 9,000 years ago, is one of the longest domestication processes in the history of animal husbandry. Pigs are the most important source of meat in Germany and are an essential part of domestic agriculture (BMEL statistics, 2024). The natural behavioral repertoire of pigs, which includes rooting and wallowing, has developed over the course of phylogenetic evolution as an adaptation to the specific habitats of these animals (Mayer et al., 2006). According to Mayer et al. (2006), many of these behaviors no longer serve their purpose in modern pig farming, as farmers ensure the preservation of the species and the reproduction of pigs, but the housing conditions often do not provide the animals with the necessary stimuli, such as opportunities to root or material for nest building, to express their natural behavior. Köhler (2005) analyzed the welfare of farm animals and identified restrictions on natural behavior and freedom of movement as the main causes of animal welfare problems in animal husbandry, which lead to behavioral abnormalities. Breeding sows are usually inseminated artificially. In this context, sows are temporarily housed in crates with the aim of optimizing breeding success. However, this form of individual housing has been the subject of controversial discussions for some time, and the seventh amendment to the Animal Welfare Farm Animal Husbandry Ordinance (TierSchNutztV) will only allow short-term individual housing of gilts and sows in crates from 2021. After this period, group housing of the animals will be mandatory. In order to grant farms an appropriate transition period, a regulation has been adopted to adapt to the new legal situation (Animal Welfare Livestock Farming Ordinance, 2006). According to Jathe (2017), most fattening pigs are kept on fully slatted floors. Low-stimulus housing conditions can therefore promote the occurrence of abnormal behavior such as tail biting, bar biting, sham chewing, and weaving (Mayer et al., 2006). In recent years, the social debate on animal welfare and animal rights has gained importance in Europe, and particularly in Germany. According to Mondon et al. (2017), the two aspects of animal welfare and well-being are summarized under the term “animal welfare” (Mondon et al., 2017). The three dimensions of animal welfare are animal health, natural behavior, and emotional state (Fraser et al., 1997; Fraser, 2008). The results of the 2014 Eurobarometer special survey indicate that the European population considers providing a wide range of high-quality products and maintaining economic activity and employment opportunities in rural areas to be the farming industry’s primary tasks (Spezial Eurobarometer 410, 2014). Ensuring the welfare of farm animals ranks sixth among EU citizens (Spezial Eurobarometer 410, 2014). To define the term “welfare,” it is recommended to use the definition provided by Broom (1986): “The welfare of an individual is its state as regards its attempts to cope with its environment (Broom, 1986)”. This is particularly relevant in light of the current prevalence of intensive livestock farming. In such systems, large groups of animals are kept in confined spaces, which significantly limits the care that can be given to individual animals and the consideration of their species-specific needs. In this context, the importance of animal-friendly husbandry for the welfare of livestock must be considered a key aspect. Schmitz et al. (2024) investigated the views of livestock farmers in Germany on animal husbandry and animal welfare. The results of Schmitz et al. (2024) indicate that livestock farmers see themselves as responsible for the welfare of their animals and would like to see political and social support for this. According to Köhler (2005), an animal’s welfare can be defined as the harmonious interaction between the animal and its environment. Welfare arises when an animal interacts with its environment and its basic needs are satisfied. Abnormal behavior and health problems are signs that an animal’s welfare is compromised (Köhler, 2005). In their study, Wildraut and Mergenthaler (2020) point out that, from an economic perspective, animal husbandry can be considered efficient as long as farm animals deliver high production performance, which promotes respectful treatment of the animals. Furthermore, Mundjar and Theuermann (2012) argue that emotional relationships with farm animals are rare in today’s capitalist society and are therefore hardly recognized. The generation of added value by farm animals is of crucial relevance to their function and status (Mundjar and Theuermann, 2012). Emotionality is the ability to experience and express emotions (Mees, 2006). In relation to humans and animals, it means a general positive attitude and appreciation towards animals (Mundjar and Theuermann, 2012). A survey of German farmers conducted by Wildraut and Mergenthaler (2020) revealed that the relationship between humans and farm animals is characterized by power imbalances, inequality, and dependence on the performance of their animals. However, livestock farmers rarely discuss their emotional attachment to their animals (Wildraut and Mergenthaler, 2020). Furthermore, Wildraut and Mergenthaler (2020) found that the respective animal species and production stage have a significant influence on the intensity of the relationship. The results of that study suggest that the smaller the livestock population, the more intense the relationship between humans and livestock (Wildraut and Mergenthaler, 2020). The human-animal relationship is defined by various types of interaction and social bonding between humans and animals (Mundjar and Theuermann, 2012). According to Mundjar and Theuermann (2012), mutual understanding between humans and animals is the key to a positive human-animal relationship. Animals are constantly adapting to the human environment (Mundjar and Theuermann, 2012). In many respects, today’s intensive livestock farming contradicts the ethical values prevailing in modern German society, particularly in relation to utilitarian considerations versus emotionally charged attitudes toward livestock. The changing relationship between humans and livestock has led to tensions, with animal welfare and ethics becoming the focus of social debate (Spiller et al., 2015). In agriculture, the relationship between humans and livestock is unbalanced and characterized by the superiority of humans (Wildraut and Mergenthaler, 2020). The social debate is characterized by two opposing perspectives. From a utilitarian point of view, the focus is on cost-benefit considerations, the overall benefits in terms of efficiency, productivity, and economic advantages, and the weighing of animal welfare against other social goals. According to utilitarianism, moral action is aimed at maximizing utility. The overriding interest is in the practical value of an animal or the habitat of animals (Kellert, 1976). In contrast, the emotionally charged perspective emphasizes the dignity of animals, their intrinsic value, empathy and emotional attachment, and the demand to minimize suffering, regardless of the economic consequences. According to Kellert (1976), moralistic and naturalistic attitudes are part of the emotional basic attitude. In naturalism, moral values are reduced to natural facts. The overriding interest is in an affection for wild animals and nature (Kellert, 1976). In moralism, this attitude regards morality as the sole basis for behavior between people and places excessive emphasis on it. It includes a general sense of justice regarding the appropriate treatment of animals and a strong aversion to their exploitation and violence (Kellert, 1976). Research into the relationship between humans and livestock in the context of animal husbandry has so far focused in particular on the factors that influence this human-livestock relationship and on its effects on animal welfare and the provision of suitable housing conditions. The aim of the study was to investigate the relationship between the basic attitudes of livestock farmers, the respective husbandry conditions, the occurrence of behavioral abnormalities in pigs, and the welfare of the pigs. The underlying hypothesis is that there is a significant correlation between the attitudes of livestock farmers toward the housing conditions they create and the welfare and development of behavioral abnormalities in pigs.

2 Material and methods

2.1 Survey design

This study is based on an anonymous online survey of pig farmers in Germany. A structured online questionnaire was used to collect data for quantitative analysis. This approach encouraged a high number of participants while ensuring anonymity and data protection. The data collected in the survey was anonymized and analyzed. Participation in the study required prior consent to the use of data in accordance with the General Data Protection Regulation (Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data, and repealing Directive 95/46/EC (General Data Protection Regulation)), which had to be given at the beginning of the questionnaire. The remaining questions were answered on a voluntary basis, with participants having the option to skip questions if they wished. The approach presented in this article aims to increase the quality of responses and reduce the dropout rate. The resulting fluctuations in sample size are reflected in the results. The survey was conducted using LimeSurvey® (LimeSurvey GmbH, 112 Hamburg, Germany).

2.2 Pilot tests

The validation of the survey questions was verified by the preceding pilot study. In the pilot phase, the survey process was evaluated among six livestock farmers. The aim was to evaluate the feasibility, assess the comprehensibility of the questions, and examine the acceptance of the study. In addition, the results were to be used to optimize the questionnaire design and data collection. A test-retest approach was used to check the reliability of the questionnaire. The questionnaire was administered twice to the same group of test subjects at four-week intervals. The high correlation between the results of both tests confirmed the methodological reliability. Based on the feedback received, unclear wording was rephrased and missing aspects were added. The questionnaire was then subjected to a final revision.

2.3 Participants

As part of the survey, livestock farmers were asked to complete a questionnaire on the characteristics of their pig herd, the specific housing conditions in the barn, and the diseases prevalent and present on their farm. In addition, participants were asked to provide a subjective assessment of the pigs’ behavior toward humans, the occurrence of abnormal behavior in the herd, and their relationship with the pigs and their duty of care toward them.

2.4 Questionnaire structure

The questionnaire comprised five sections with a total of 25 question groups. The total number of questions was 105. Some questions could be answered more than once. The pre-formulated answers were intended to facilitate the selection of an answer and the subsequent evaluation. For each section, there was the option to provide an additional answer in a free text field. The questionnaire comprised the following main sections relevant to the study. I. The focus is on collecting data on livestock and animal husbandry: The corresponding section of the questionnaire therefore contains questions on various aspects of livestock data and pig husbandry conditions. The survey covered a range of factors, including the composition of the pig population, the number of pigs, the type of use, the type of housing, the design of the lying areas, the feed and water supply, the design of the floors, and the provision of enrichment materials. II. Focus on welfare: A subjective survey of the occurrence of diseases in the entire pig herd that occur or have occurred weekly, monthly, or every six months. Information from health analyses or slaughter findings was also included in the disease survey. III. Focus on behavior: This section of the questionnaire included questions that examined the behavior of pigs toward humans and the occurrence of defensive behavior in various everyday situations. In addition, the apparent occurrence of abnormal behavior within the pig herds was recorded. The data was collected through the participants’ daily interaction with the pigs and was based on their personal experiences with the pigs. In addition, statements were made regarding the participants’ self-assessment of their relationship with pigs. The respective statements could be agreed with completely, partially, or not at all. IV. Focus on human-animal relationships: The study asked questions about working with pigs in the context of due diligence. Pig farmers and animal caretakers were asked to evaluate their own interactions with pigs and human-animal interactions. The aim was to identify emotional or utilitarian attitudes. V. 60 closed questions according to Kellert: The study used 60 closed questions based on Kellert (1993b) to determine the participants’ basic attitudes. The questionnaire, which examined the relationship between humans and nature as well as between humans and animals, included questions on the biology and ecology of animals and nature, hunting, the protection of endangered species, the control of wildlife damage, and environmental protection. Kellert’s questions were designed to determine basic attitudes toward animals and nature. The evaluation of the answers to 60 questions enabled conclusions to be drawn regarding the ten basic attitudes toward animals and nature defined by Kellert (1976) among livestock farmers (Table 1).

Table 1. Meaning of the ten basic attitudes of people towards animals and nature in general according to Kellert (1976).

2.4.1 Categorization of basic attitudes according to Kellert

The study conducted by Stephen R. Kellert between 1973 and 1993 divides people’s basic attitudes toward animals and nature into ten categories (Table 1). The definitions are taken from Kellert (1976). Kellert’s 60 closed questions examine the relationships between humans and animals and between humans and the environment, covering topics such as animal welfare, environmental protection, and interest in animal-related activities and documentaries. Kellert (1980, 1984, 1993b), which is adapted to the culture and living environment of the United States of America, was replicated by Schulz (1986) and adapted to German conditions. The questionnaire used in the study corresponded to the version used in Germany according to Schulz (1986).

2.4.2 Evaluation of the integrated questionnaire according to Kellert

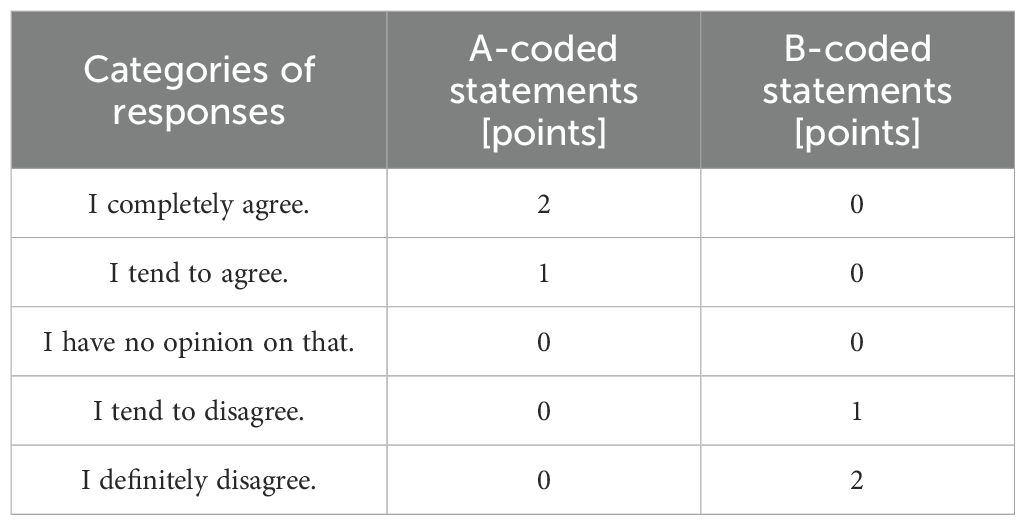

Participants were asked to indicate their agreement with the statements presented by selecting one of the following options: “I completely agree,” “I tend to agree,” “I have no opinion,” “I tend to disagree,” and “I completely disagree.” Depending on the livestock farmer’s response to each statement, zero, one, or two points could be awarded, indicating full or partial agreement/disagreement or abstention (Table 2). As part of the evaluation process, the questions were divided into two categories:

Both coding systems measure clear approval or disapproval. Neither the option “I have no opinion” nor the options weak rejection “I tend to disagree” (A coding) or weak agreement “I tend to agree” (B coding) provide a clear positive or negative assessment. To avoid bias, they are treated as neutral so that they do not influence the direction of the attitude. The aim of the procedure is to capture differences between complete agreement and clear rejection. Since “no opinion” is neither affirmative nor negative, it is treated neutrally with 0 points – regardless of whether the statement is coded A or B.

2.5 Data collection

Pig farmers were made aware of the study through various communication channels. The institutions contacted included regional pig health services, regional pig breeders’ and farmers’ associations, national veterinary and agricultural authorities, animal welfare organizations, and direct contacts in agricultural businesses and large animal practices. Of these, regional pig health services, regional pig breeders’ and farmers’ associations, agricultural pig farms, and large animal practices participated. The information was forwarded by the interest groups to their customers or members via various social media channels, newsletters, and email. Certain methodological aspects must be considered when recruiting samples and ensuring data validity. For example, recruiting participants through professional associations can lead to systematic bias in the sample. The present study indicates that smaller agricultural businesses may not have been reached and are therefore underrepresented in the sample. This may lead to selection bias and limit the generalizability of the results to the entire target population. Furthermore, no measures were taken to prevent duplicate responses (e.g., through IP checks). This approach was intended to ensure the anonymity of respondents, allowing participants to submit their responses in a protected environment, even if this meant that duplicate responses were possible. During the one-year survey period (September 2021 to August 2022), the link to the questionnaire was sent to 600 livestock farmers. It took about 20 to 25 minutes to complete the questionnaire. Participation was voluntary. The data was collected anonymously, and participants had the option of providing their email address to be informed about the results of the survey. Of the 600 livestock farmers, 485 pig farmers took part in the survey, of whom 330 completed the questionnaire partially and 155 completed it in full. This means that the gross response rate is 81%. This is the proportion of all persons who could be reached, regardless of whether the questionnaire was completed in full or only partially. The net response rate is 26%. This is the proportion of fully completed questionnaires relative to the total sample and thus provides information about the complete response rate.

2.6 Statistical analysis

All questions and answers provided by participants were coded during data analysis. First, the raw data was processed using Microsoft Excel software. The graphical representation of the different distribution of production directions was also created in Excel in order to produce clear and presentable visualizations. Data analysis was performed using IBM SPSS® Version 29 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) statistical software. The responses included in the study comprise all answered questions, including partially completed questionnaires. This resulted in missing values in some variables when evaluating the questionnaire data. In order to use the information from the partially completed questionnaires, the analysis was performed on the basis of pairwise deletion. This means that for each analysis, only those cases were considered in which the relevant variables were complete. In view of this, the sample size varied depending on the analysis, which was taken into account in the interpretation of the results. Descriptive statistics were used to determine the minimum and maximum values, means, standard deviations, medians, frequencies, and percentages based on the questions answered. Given the different sample sizes, the respective sample size is indicated uniformly in the results. Data analysis was performed using Pearson’s correlation, Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient, the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin index, multiple linear regression, analysis of variance, and the χ² test to analyze the correlations between the number of pigs, the housing system, animal behavior, human-animal relationships, behavioral abnormalities, and health problems (Table 3).

3 Results

3.1 Distribution of production direction and husbandry systems

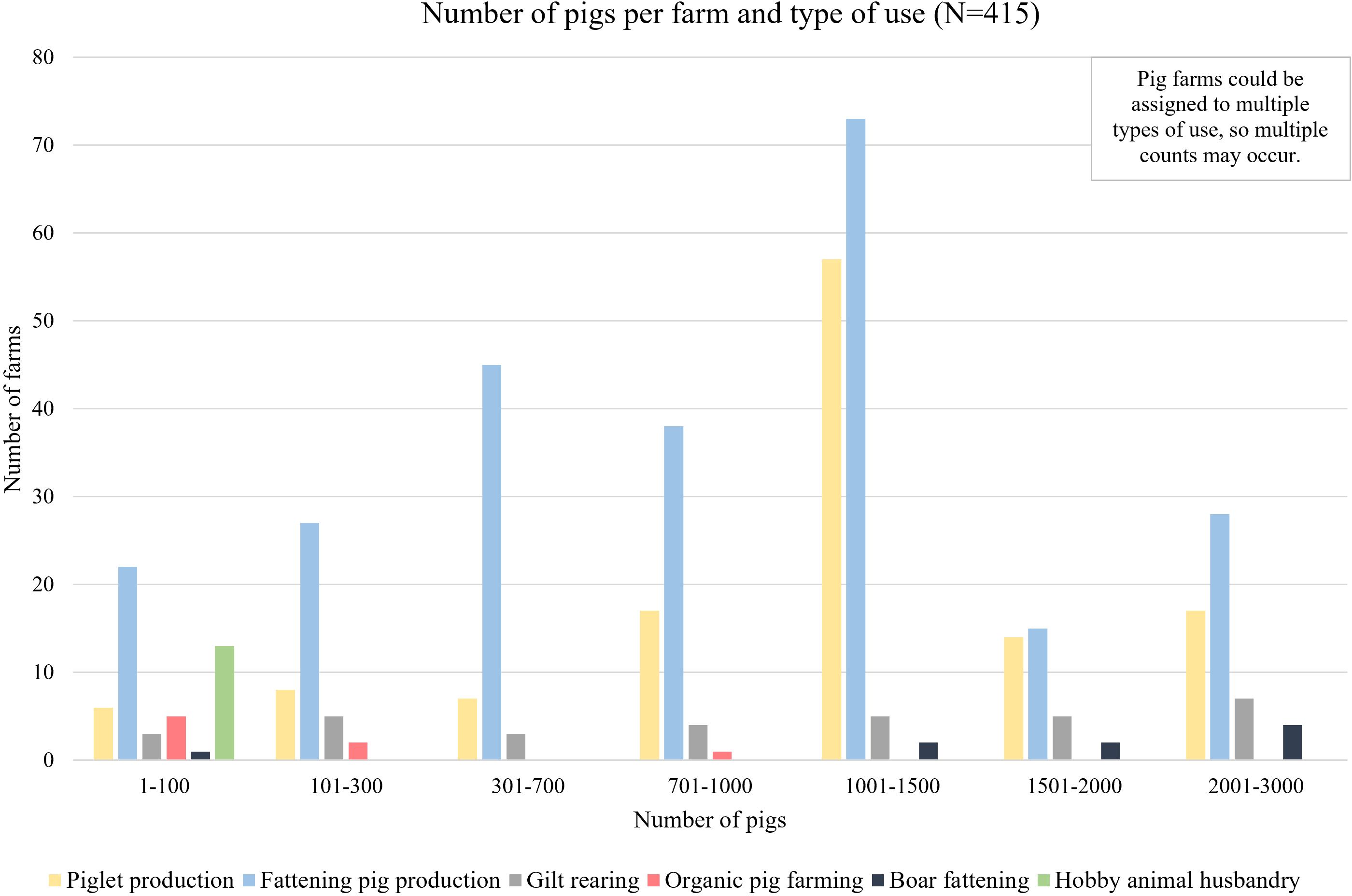

The highest number of pigs was found on farms specializing in piglet production and fattening pig production (N = 415, Figure 1). The results obtained from the sample indicate that the pigs are mainly kept in two types of farming systems: 39% in pure pig fattening and 39% in mixed production. The most common production combinations are piglet production with fattening (67%) and piglet production with gilt rearing (61%). In addition, the housing systems “pure piglet production” (13%), “hobby farming” (3%), “pure gilt rearing” (approx. 1%) and “free-range farming” (less than 1%) are differentiated (N = 265, Figure 2). The size of the subsample (N = 265) corresponds to the number of pig farms that provided valid information on their production direction. It serves as a descriptive representation of the current production distribution.

3.2 Correlation between herd size, housing systems, and abnormal behavior in pigs

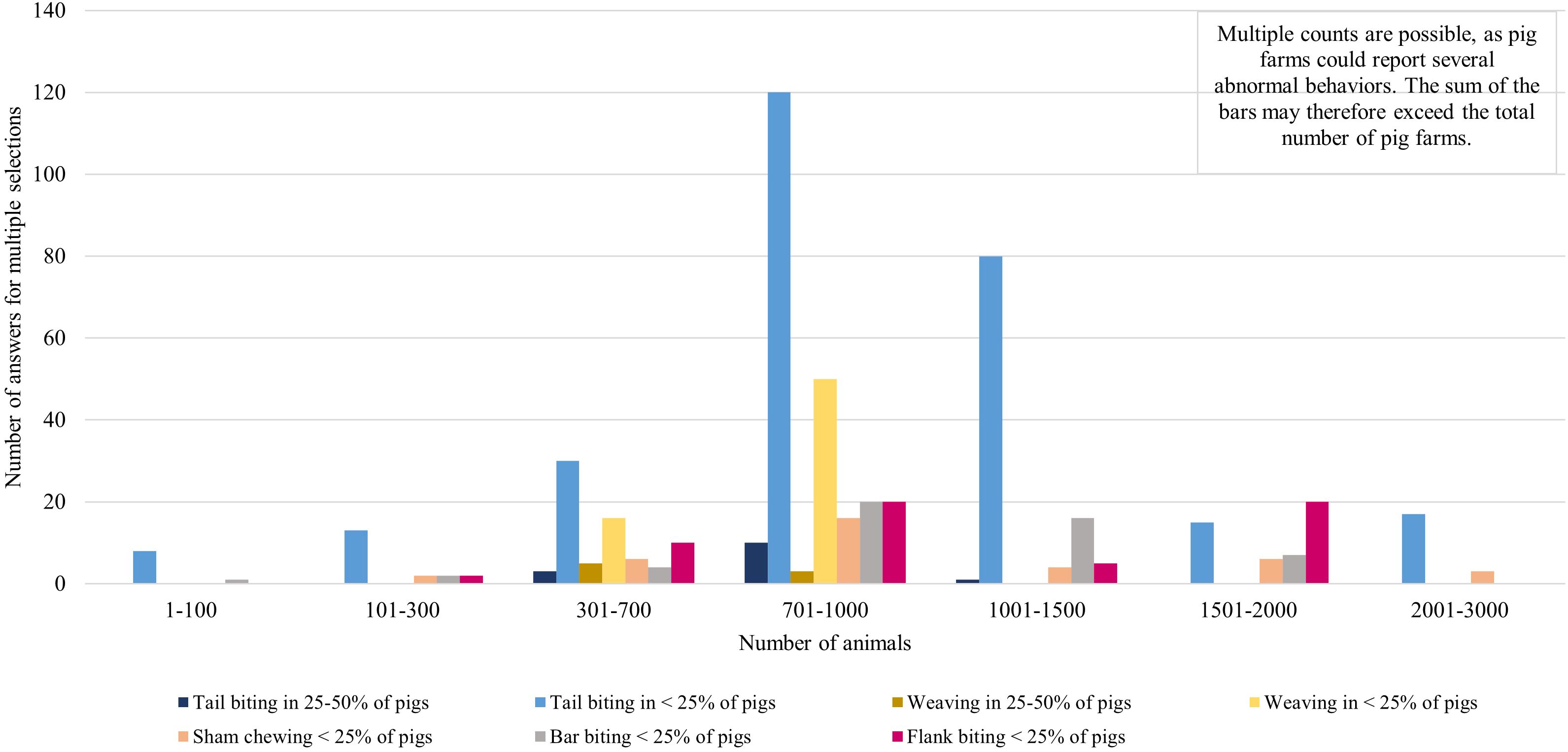

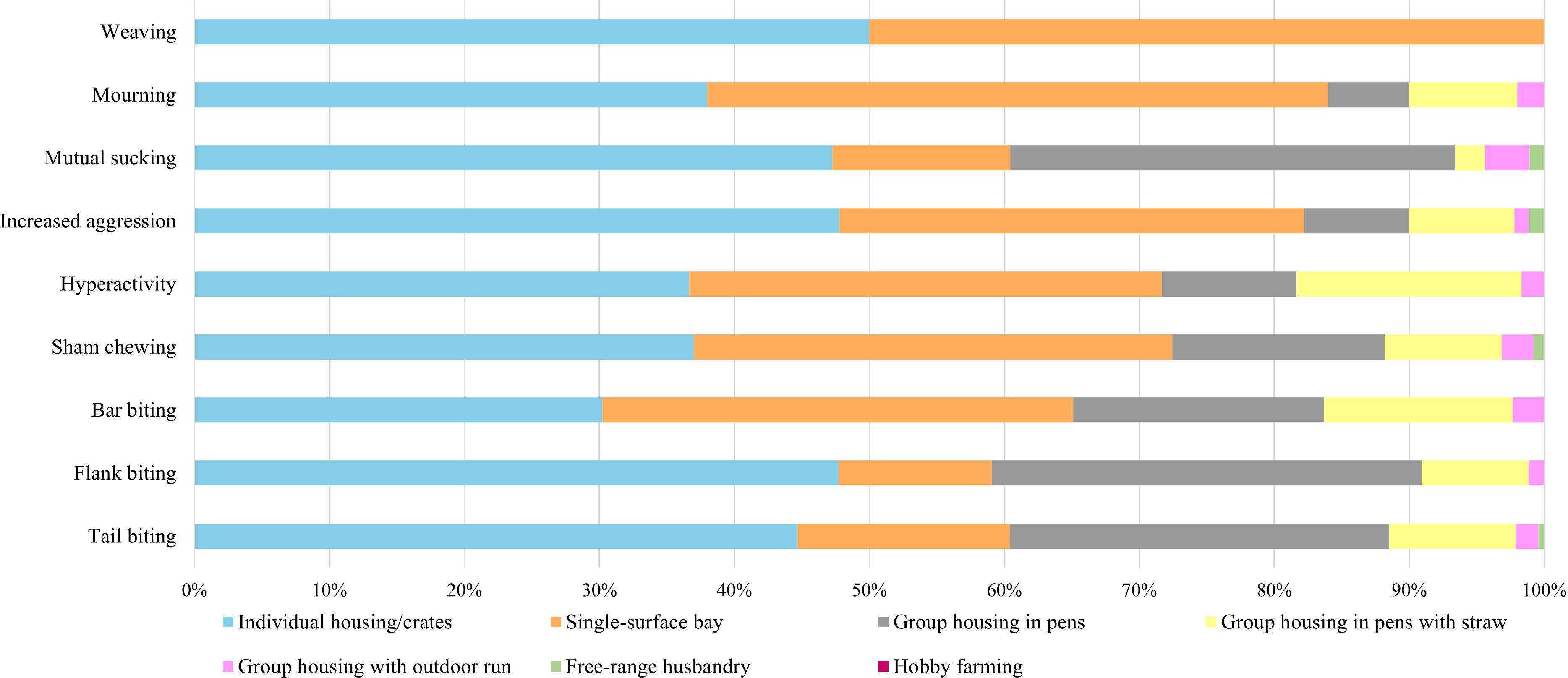

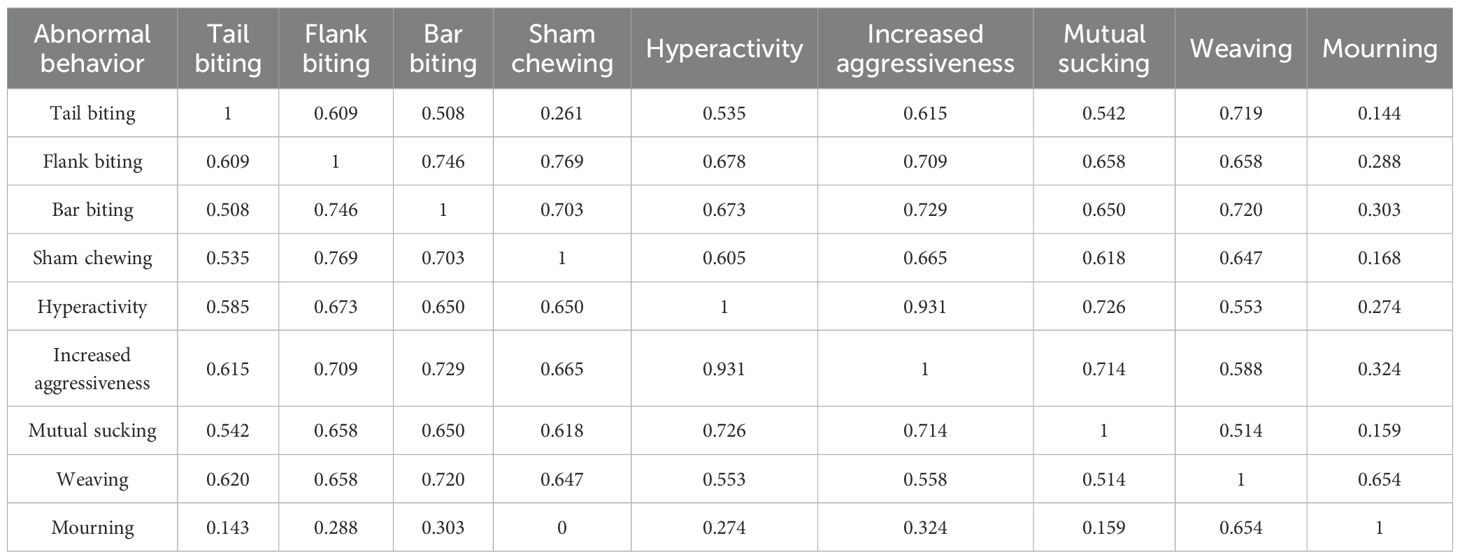

The evaluation of animal welfare data collected under different housing systems showed that the probability of behavioral abnormalities such as tail biting and weaving is significantly higher in farms with more than 700 animals (80%) than in farms with up to 300 animals. A significant correlation was found between farm size and the occurrence of tail biting (x² = 58.710, p < 0.001). Weaving, on the other hand, was only reported on farms with 300 to 1,000 animals. Sham chewing, bar biting, and flank biting were reported on farms with up to 2,000 pigs. Larger farms with more than 3,000 pigs did not report any abnormal behavior in the pigs (x² = 63.240, p < 0.001, Figure 3). Compared to conventional husbandry, pigs kept exclusively for hobby purposes do not show any behavioral abnormalities such as tail biting and hyperactivity (x² = 53.148, p < 0.001). The housing of sows in crates in the farrowing area is associated with a significantly higher frequency of, for example, weaving and bar biting than group housing of sows (x² = 40.193, p < 0.001). In addition, an increase in other abnormal behaviors such as flank biting, hyperactivity, sham chewing, and aggressive behavior was detected in individual housing (Figure 4). The occurrence of additional abnormal behaviors correlated significantly with pre-existing abnormal behaviors in pigs. Values of 1 indicate that there is a significant positive correlation between the various abnormal behaviors. An increased level of aggression therefore shows a high positive correlation with hyperactivity. The latter shows a significant positive correlation with flank and tail biting as well as sham chewing (p < 0.001, Table 4).

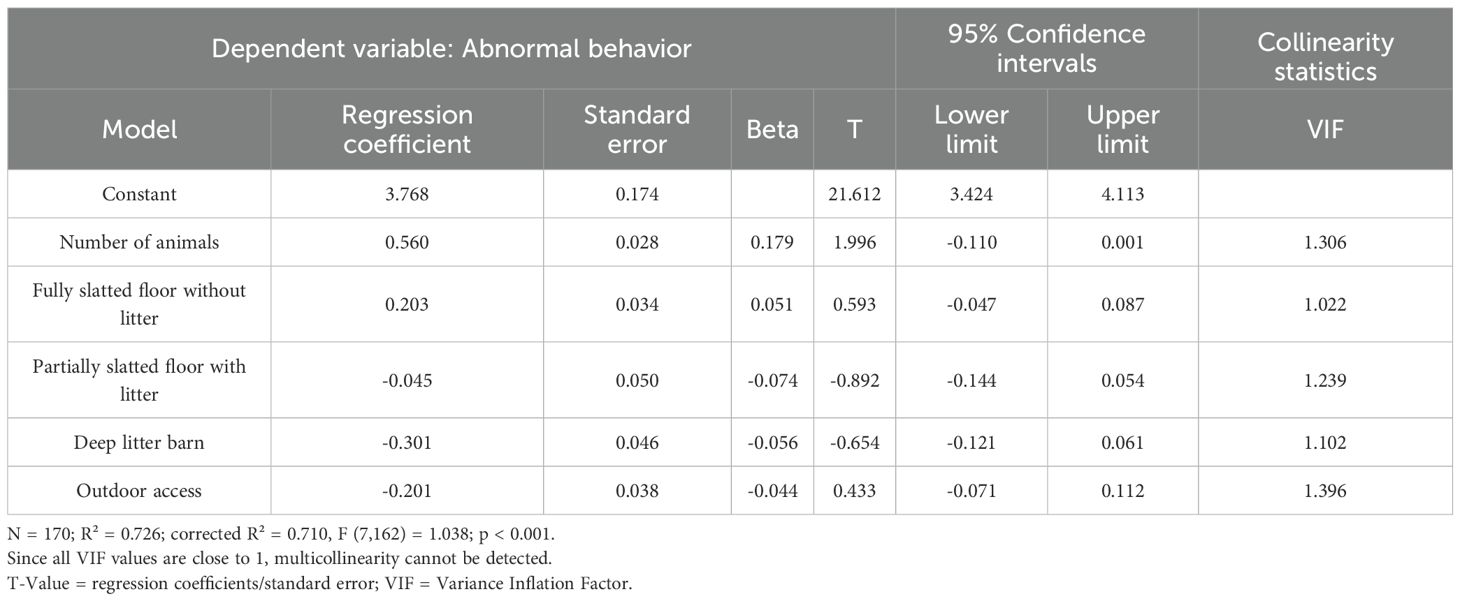

3.3 Influence of flooring, herd size, and freedom of movement on the occurrence of abnormal behaviors in pigs

The present results suggest that, in addition to the housing system, the type of flooring and the number of animals are also associated with the occurrence of abnormal behavior (Table 5). The results of the multiple linear regression analysis suggest that the occurrence of abnormal behaviors such as tail biting, flank biting, mutual suckling, hyperactivity, increased aggression, and bar biting is influenced by the different types of flooring (such as fully slatted floors, partially slatted floors, deep litter, or outdoor housing) on which the pigs move, as well as by the number of animals (F (7, 155) =1.182, p < 0.001).

Table 5. Abnormal behavior influenced by floor type and number of animals by multiple linear regression.

3.4 Correlation between floor type, herd size, freedom of movement, and the occurrence of abnormal behavior in pigs

In addition, fully slatted floors were most common in farms with more than 100 pigs, while partially slatted floors with litter or deep litter were more common in farms with up to 100 pigs (x² = 156.967, p < 0.001). The statistical analysis revealed significant correlations between the pigs’ range of movement and the type of use (x² = 30.622, p < 0.001). In piglet production and gilts rearing, up to 40% of cases involve housing that is fully equipped with slatted floors and has no bedding. In fattening pig production, however, fully slatted floors are used significantly more often (80%) than housing systems that are partially equipped with slatted floors and have litter or deep litter systems (x² = 45.589, p < 0.001). Only 4% of pigs had access to outdoor runs (x² = 28.385, p < 0.001, Figure 5). In free-range systems that allow rooting and natural behavior, less than 1% of participants reported abnormal behavior such as tail biting, hyperactivity, and increased aggression (x² = 46.651, p < 0.001).

3.5 Correlation between the provision of enrichment materials and abnormal behavior in pigs

In addition, a significant correlation was found between the occurrence of abnormal behavior and the availability of enrichment materials. On the farms, providing a combination of chew chains and pieces of wood led to a significant reduction in tail biting, mutual sucking, and aggression in the pig population by up to 87% (x² = 36.754, p < 0.001, Figure 6). In addition, a significant reduction in tail biting and aggressive behavior was observed in pigs that had access to natural rooting opportunities and outdoor rooting areas (x² = 33.544, p < 0.001, Figure 6). A significant positive correlation was found between the availability of wood and the availability of chewable chain sets as enrichment material (r = 0.54, p < 0.001, N = 217). An overwhelming majority of 96% of participants did not have outdoor access for their pigs to root.

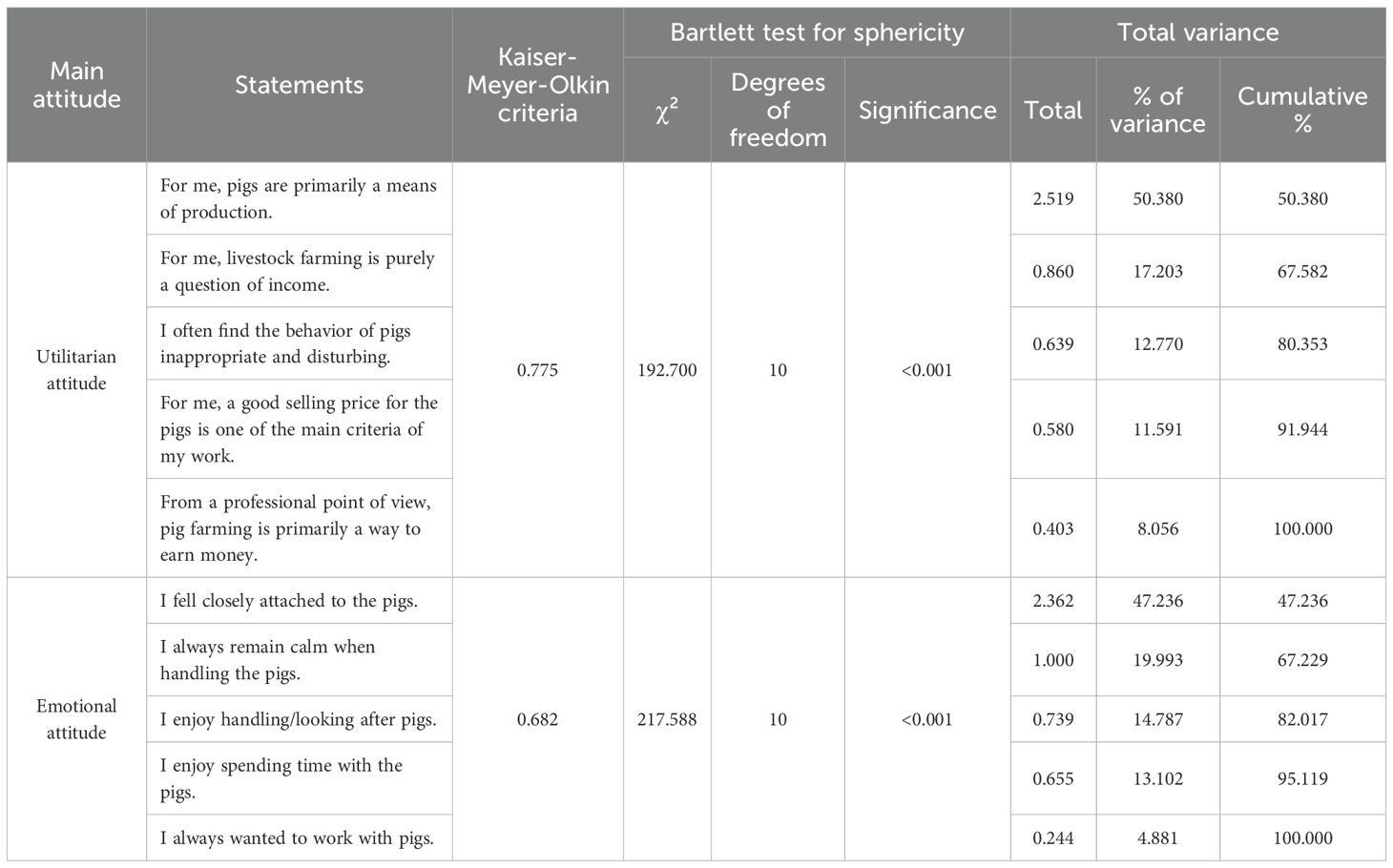

3.6 Correlation between livestock farmers’ basic attitudes and their self-assessment

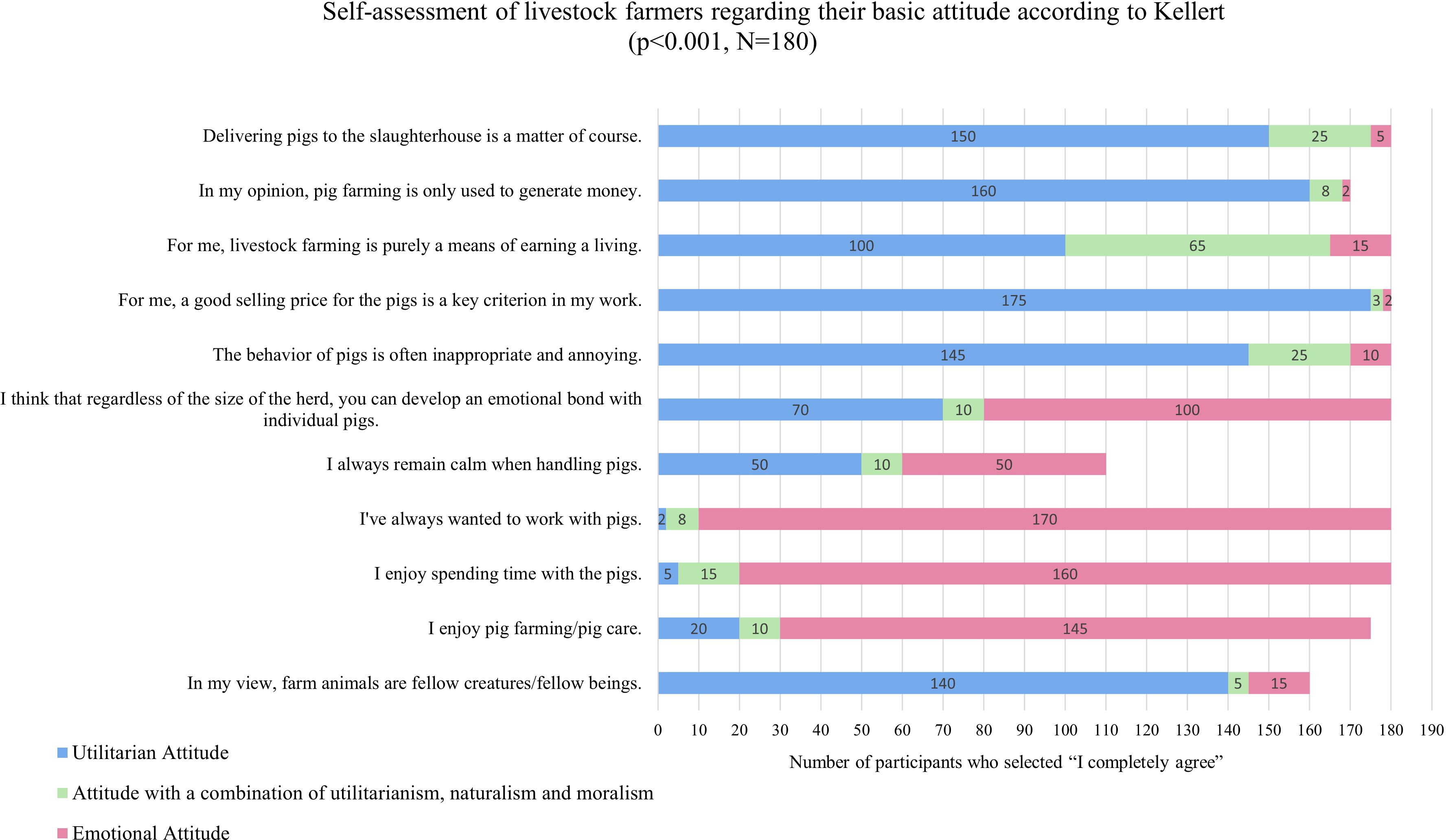

The survey analysis of self-assessment revealed a utilitarian attitude when livestock farmers stated that the main criterion for their work was the selling price of the pigs (item 1, Table 6), that they regarded pig farming as a mere source of income (item 2), that they often found the behavior of the pigs annoying (item 3), and that livestock farming was purely a matter of earning a living. In contrast, pig farmers who agreed with the statements (1) “I consider pigs to be fellow creatures.”, (2) “I enjoy working with pigs.”, (3) “I am calm when handling my pigs.” and (4) “I feel closely connected to my pigs.” were assigned an emotional attitude (Table 6).

Table 6. Self-assessment statements to determine the attitude of livestock farmers, determined by principal component analysis (PCA), N = 174.

3.7 Evaluation of the basic attitude according to Kellert/Schulz

The evaluation of the integrated questionnaire according to Kellert (based on Schulz, 1986) resulted in the majority of livestock farmers (94%) having a utilitarian attitude. An emotional attitude was evaluated in 5% of livestock farmers, while 1% had a mixed attitude with elements of utilitarianism, naturalism, and moralism.

3.8 Correlation between the basic attitude, self-assessment of livestock farmers, and provision of enrichment materials

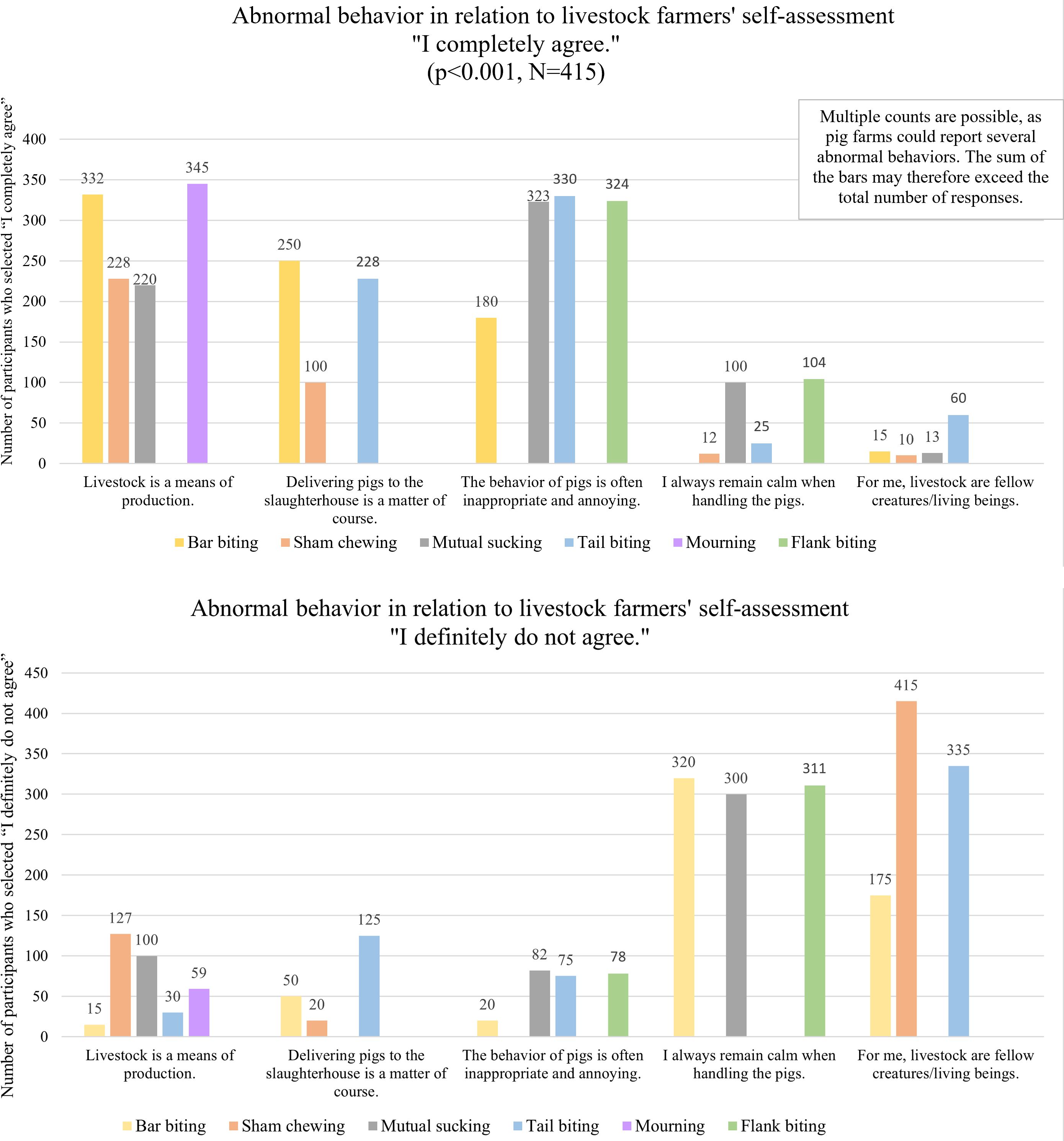

The results of the study show that livestock farmers with a utilitarian attitude increasingly made utilitarian self-assessments, which they selected with a high level of agreement: “I completely agree.” (x² = 210.359, p < 0.001, Figure 7). In addition, livestock farmers with an emotional attitude provided their pigs with enrichment material in the form of hay, straw, wood, rubber parts, and balls significantly more often (90%) than livestock farmers with a utilitarian attitude (x² = 79.828, p < 0.001). Livestock farmers with a utilitarian attitude, who consider delivery to the slaughterhouse to be a matter of course, only provided wood as enrichment material, which meets the legal minimum requirement (x² = 82.881, p < 0.001).

Figure 7. Self-assessment of livestock farmers regarding their basic attitude according to Kellert (p<0.001, N=180).

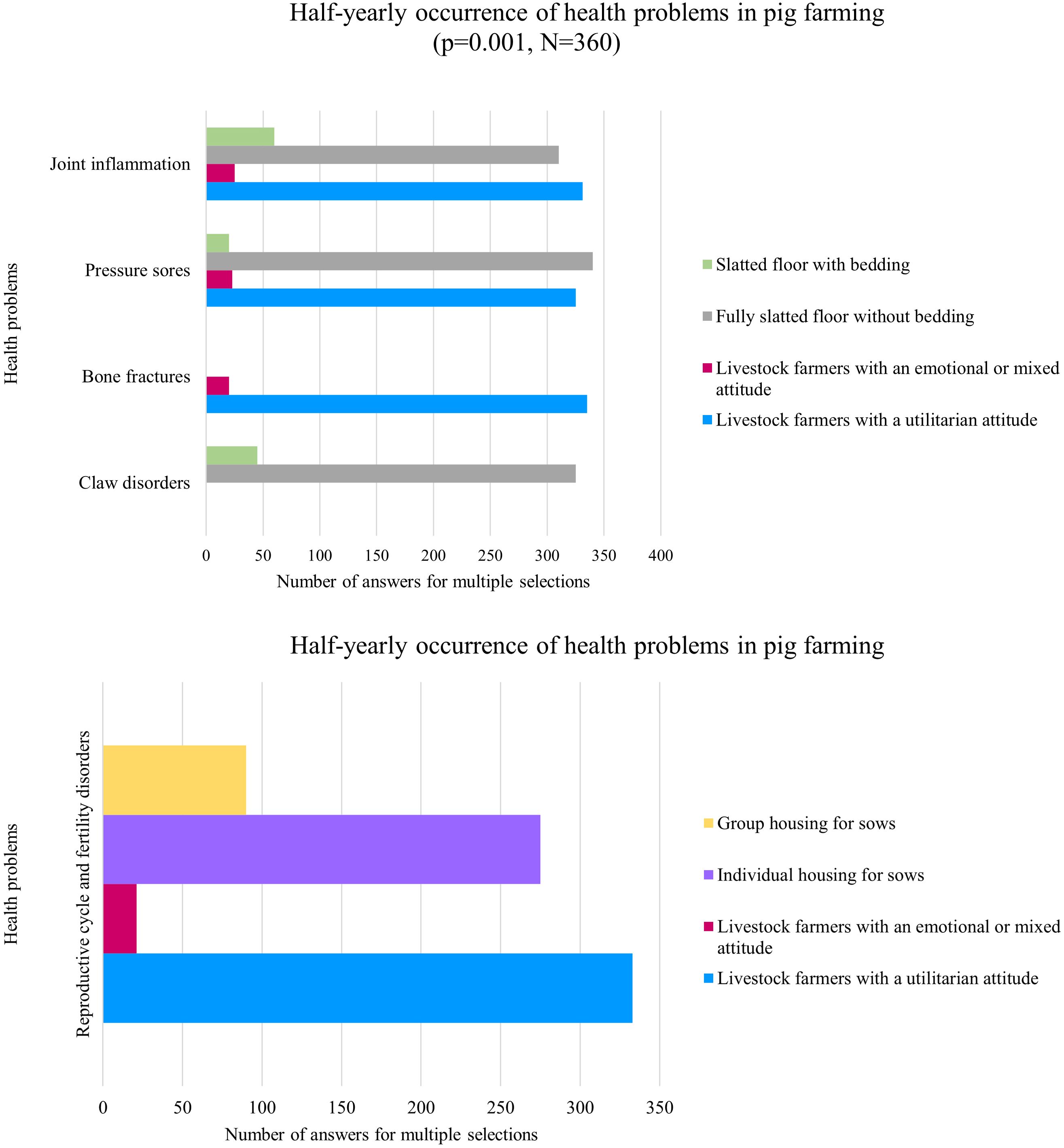

3.9 Correlation between health problems and the floor type

Existing health problems (Figure 8), especially those affecting the musculoskeletal system and the udder, are clearly related to the quality of the floor on which the pigs were kept. For example, the results indicate that foot and claw diseases occur eight times more frequently (87.5%) in pigs kept on fully slatted floors without bedding for six months than in pigs that had a soft, moldable lying surface as bedding in addition to the slatted floor (x² = 37.823, p = 0.001).

Figure 8. Half-yearly occurrence of health problems in pig farming (p=0.001, N=360), and half-yearly occurrence of health problems in pig farming.

3.10 Correlation between basic attitude and the occurrence of health problems

In addition, a relevant association was found between the basic attitude of livestock farmers and the occurrence of musculoskeletal disorders in pigs. A large majority (93%) of livestock farmers with a utilitarian attitude reported an increased incidence of musculoskeletal disorders such as bone fractures, joint inflammation, and pressure sores in their pigs (x² = 50.539, p = 0.001, Figure 8.1).

3.11 Correlation of flooring and housing systems on health problems

The quality of the flooring also had a significant correlation on the incidence of mastitis in sows. The study found that udder inflammation occurred more frequently (91%) in sows kept on fully slatted floors without bedding for a period of six months compared to sows that had access to a soft, moldable lying surface in the form of bedding in addition to the slatted floor during the same period (7%; x² = 37.823, p = 0.001). In addition, individual housing of sows led to a significantly higher rate of cycle and fertility disorders. These occurred weekly in up to 50% of sows and within six months in up to 76.5% of sows. In comparison, the six-month incidence in sows kept in groups was only 25% (x² = 51.446, p < 0.001).

3.12 Correlation between basic attitude, the occurrence of health problems, and the housing system

There was also a significant correlation between the basic attitude of livestock farmers and the occurrence of cycle disorders in their pigs (x² = 50.539, p = 0.001, Figure 8.2). The present evaluation of housing conditions indicates that 53% of utilitarian livestock farmers keep their sows in individual crates, while only 3% of emotionally oriented livestock farmers do so. In the group of utilitarian livestock farmers, there is a reported increase in the use of group housing without straw bedding for fattening pigs (45%). In contrast, emotionally oriented livestock farmers show a preference for straw bedding in the pens (58%, x² = 248.281, p < 0.001, N = 415). The picture is also mixed when it comes to the floor type in the stalls. The majority of utilitarian livestock farmers (70%) prefer a fully slatted floor for pigs. Conversely, only 13% keep pigs in deep litter stalls. The latter is characterized by an emotional attitude (x² = 226.923, p < 0.001, N = 415).

3.13 Correlation between basic attitude and abnormal behavior in pigs

The present results indicate that the basic attitude of the livestock farmers has a significant correlation with the behavior of the pigs. It was found that livestock farmers who agreed with the statement that animals are a means of production had a significantly higher incidence of behavioral abnormalities in their pigs. These differences manifested themselves in an increased incidence of bar biting (80% vs. 4%), twice as many incidents of sham chewing and mutual suckling (> 50%), and more frequent mourning behavior (83%) compared to an incidence of 14% in the case of livestock farmers who did not agree with the statement (x²=46.095, p < 0.001, Figure 9). Livestock farmers who always remain calm when handling their pigs and treat them as equal living beings reported fewer instances of abnormal behavior such as flank biting and mutual suckling (75% vs. 25%, x² = 119.057, p < 0.001). In contrast, pigs from livestock farmers who consider the delivery of their pigs to the slaughterhouse to be a matter of course (“I completely agree.”) show a significantly higher prevalence of tail biting (55%) than pigs from livestock farmers who do not agree with this statement (30%, “I completely disagree.”; x² = 37.574, p < 0.001). It was found that tail biting, flank biting, and mutual suckling occurred significantly more frequently (80%) on farms where livestock farmers considered the pigs’ behavior inappropriate and disruptive than on farms where pig livestock farmers did not agree with this statement (“I definitely disagree”., x²=153.666, p < 0.001). The results of the study show that abnormal behavior in pigs occurs significantly less frequently when livestock farmers view their pigs as fellow creatures and enjoy spending time with them (x² = 51.359, p < 0.001; Figure 9).

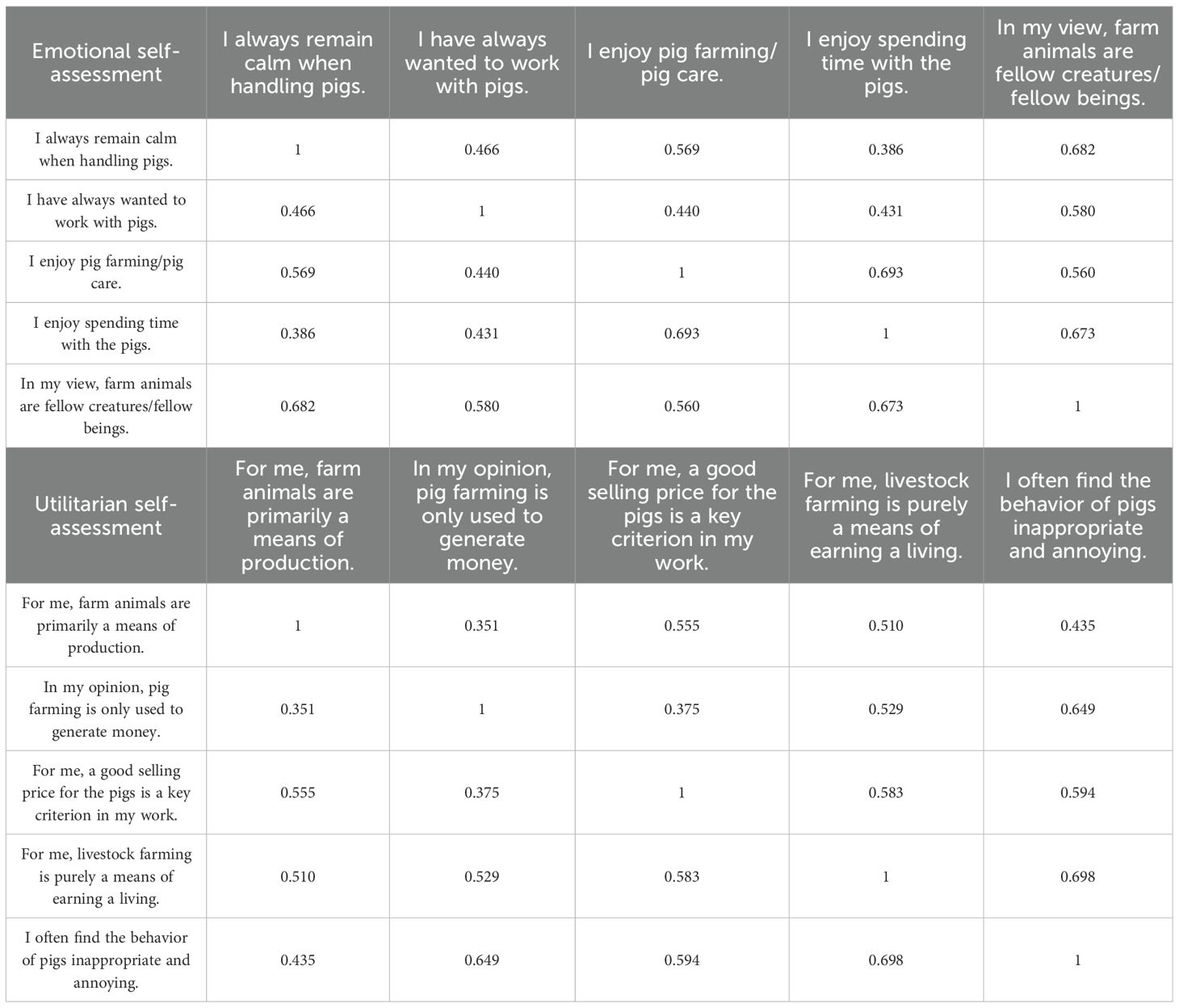

3.14 Correlation between emotional and utilitarian self-assessments of livestock farmers

The correlation analysis examined the relationship between the emotional and utilitarian self-assessments of livestock farmers. The results of the correlation analysis indicate that there is a significant positive correlation between the individual emotional statements on self-assessment. In addition, there is a strong positive correlation between the utilitarian statements. The evaluation showed that most values were between r = 0.5 and 0.7, indicating a high correlation between the statements (p < 0.001, Table 7).

Table 7. Correlation between emotional and utilitarian statements on the self-assessment of livestock farmers (N = 195, p < 0.001).

3.15 Influence and correlation of housing conditions on the behavior of pigs toward humans

This study suggests that the type of housing for pigs, especially individual and group housing, has a significant influence on their behavior toward humans. The results of the study suggest that pigs in these systems exhibit increased defensive behavior and biting behavior toward humans (F (3,175) = 4.93, p = 0.001). In addition, a significant correlation was found between increased aggression towards humans and defensive behavior during loading (KMO = 0.763, p < 0.001). The results of the study suggest that pigs kept by livestock farmers who were found to have a high level of duty of care exhibited less aggressive and hyperactive behavior toward other pigs and humans. The livestock farmers confirmed that they are guided by a high level of care in their work. They stated that their own behavior is reflected in the behavior of the pigs and that the welfare of the pigs is a high priority. In addition, they carried out daily stock checks themselves (x² = 29.911, p = 0.001). This study examined the structure of Kellert’s survey on basic attitudes toward self-assessment of basic attitudes and duty of care. For this purpose, a principal component analysis was performed. Three factors with eigenvalues above 1 were selected, which explain 70.1% of the total variance. Utilitarian farmers confirmed that pig farming serves exclusively commercial interests and should therefore be considered a commercial activity. In addition, information was presented indicating that the duty of care is minimal. For example, it was disputed that the reduced welfare of pigs depends on their housing conditions and that careful handling of pigs is important to avoid stress (x² (10) = 25.849, KMO = 0.738, p < 0.001). The results of the current study also demonstrate that the emotional attitude of livestock farmers has a significant influence on their bond with pigs. The study found that emotionally engaged livestock farmers who reported a close relationship with their pigs described pig farming as a source of personal satisfaction (F (5,168) = 4.30, p < 0.001).

4 Discussion

The results of the study indicate a significant correlation between the attitudes of livestock farmers, housing conditions, and the welfare and behavior of pigs. In addition, it was found that abnormal behavior and health problems in pigs are associated with high stocking densities, intensive housing systems without straw bedding, and a utilitarian attitude on the part of livestock farmers. The welfare and behavior of pigs is also linked to housing systems that include smaller slatted floor areas, herd sizes of up to 300 pigs, outdoor access, enrichment materials, and an emotional bond between humans and pigs. Various studies confirm the positive effects of a pig-friendly environment. The literature also mentions factors that promote the development of abnormal behavior (Mayer et al., 2006; Sundrum, 2020). The authors particularly highlight factors that influence the housing conditions of pigs. These include the design of the barn floor, design options, stocking density, climatic influences, tail docking, species-specific factors, feeding, husbandry, and diseases (Mayer et al., 2006; Sundrum, 2020). The study results indicate that the use of partially slatted floors with litter reduces the occurrence of tail biting, flank biting, hyperactivity, and mutual suckling by 50% compared to fully slatted floors. Nevertheless, most farmers use fully slatted floors as flooring. It is particularly noteworthy that in free-range systems, where pigs have the opportunity to root and express their natural behaviors, abnormal behaviors such as tail biting, hyperactivity, or increased aggression were reported only very rarely. These results are consistent with the study by Fels (2019), which found that the creation of a species-appropriate environment for pigs with suitable design options is crucial for a balanced enrichment of the housing environment. In the present study, a significant reduction in aggression, hyperactivity, flank biting, mutual suckling, and tail biting was reported in pigs of all age groups when manipulable wooden material or play chains were provided. These results are confirmed by the findings of Mayer et al. (2006), who reported in their study that tail biting can be reduced or even prevented by providing manipulable materials, structured feed, and suitable bedding. In contrast to conventional housing systems, the present study found a lower incidence of abnormal behavior in farms with smaller numbers of animals. Furthermore, no abnormal behaviors such as tail biting and hyperactivity were recorded in hobby farming. In agreement with Ziemke (2007), intensive housing leads to a significant increase in abnormal behaviors such as tail biting, which results in a deterioration of animal welfare and economic losses. A further reduction in behavioral problems, such as tail biting, was reported in pigs kept in a barn with a soft, moldable lying area in the form of a straw mat. The study by Ziemke (2007) confirms that tail biting occurs significantly more frequently in slatted floor barns than in barns with litter. Slatted floors are the most common form of pig housing in Germany (Federal Statistical Office, 2020). According to the German Animal Welfare Farm Animal Husbandry Ordinance (Animal Welfare Livestock Farming Ordinance, 2006), floors in stables and outdoor areas must be slip-resistant and safe to walk on. According to Borell and Huesmann (2009), pigs kept on fully slatted floors suffer significantly more claw and limb injuries than pigs kept on solid or straw-strewn floors. The results of the present study confirm that keeping pigs on fully slatted floors without bedding is associated with a significantly higher prevalence of claw injuries. The development of claw damage is attributed to increased and uneven pressure distribution caused by keeping animals on slatted floors (Mouttotou et al., 1999). The present study also found that individual housing of sows was associated with a significantly higher incidence of behavioral abnormalities such as tail biting, flank biting, bar biting, hyperactivity, increased aggression, and sham chewing than group housing. As Fels (2019) has already described, housing systems for sows that do not involve individual housing are becoming increasingly important. This is also reflected in the minimum requirements of the German Animal Welfare Farm Animal Husbandry Ordinance (Animal Welfare Livestock Farming Ordinance, 2006). Mayer et al. (2006) have shown that abnormal behavior is caused by a lack of stimulation and exercise. The study found abnormal behaviors such as tail biting, mutual suckling, flank biting, and sham chewing, particularly in conventional housing systems with slatted floors and a less stimulating environment (Mayer et al., 2006). According to the report on which the European Food Safety Authority’s (EFSA) scientific opinion on the risks of tail biting is based, tail docking can be considered an effective measure in today’s intensive pig farming (European Food Safety Authority, 2007). Environmental and possibly genetic risk factors play a role in tail biting. The EFSA has asserted that tail docking can reduce tail biting in intensive farming contexts; however, it remains an ineffective solution in the presence of suboptimal housing conditions (European Food Safety Authority, 2007). According to Annex I, point 8, of Council Directive 2008/120/EC, routine surgical procedures on pigs are prohibited (Pig Protection Directive, (2008/120/EC): Council Directive 2008/120/EC of 18 December 2008 concerning the minimum standards for the protection of pigs). Therefore, alternative measures to prevent tail biting and other undesirable behaviors must be implemented. In this context, aspects of housing and stocking density must be taken into account and adjusted (European Food Safety Authority, 2007). Hahn and Kari (2021) argue that abnormal animal behavior is the result of intensive, human-induced housing restrictions that prevent animals from exhibiting their typical behavior. The results of the study suggest that, in addition to housing conditions, the attitudes of livestock farmers toward their pigs also have a significant correlation with the occurrence of abnormal behavior and the welfare of pigs. The present study concludes that pigs kept by livestock farmers with a utilitarian attitude are at increased risk of abnormal behavior such as tail and flank biting and muscle and skeletal disorders. In addition, increased defensive and resistant behavior of pigs toward livestock farmers was mentioned. This supports the findings of Mundjar and Theuermann (2012), who concluded that farmers view farm animals as working animals rather than pets. However, the study also shows that a professional relationship does not always lead to a lack of empathy and appreciation for farm animals. The results of the study suggest that livestock farmers with an emotional attitude have a close bond with their pigs, perceive them as fellow creatures, and show a high level of care. It was also found that pig farmers who display an emotional attitude rarely or never have problems with the behavior of their pigs, and that their pigs show fewer incidences of abnormal behavior. The majority of livestock farmers took a utilitarian attitude toward their pigs, viewing them as an economic necessity and keeping pigs solely for financial reasons. In these cases, abnormal behavior was reported more frequently. These results are consistent with the study by Sundrum (2018), which concluded that responsibility for animal welfare lies solely with the animal owners. However, animal owners often only meet the minimum legal standards, which do not correspond to species-appropriate animal husbandry (Sundrum, 2018). Nevertheless, when interpreting our results, it should be noted that questions about the human-livestock relationship are highly susceptible to social desirability bias. Given that pig farming in Germany is currently the subject of intense public debate, in which the practices involved are often criticized, there is a possibility that attitudes and behaviors may be presented as more animal welfare-oriented than they actually are in practice. According to Wildraut and Mergenthaler (2020), society demands that livestock farmers go beyond the minimum legal standards and ensure improved and species-appropriate livestock farming. In addition to optimizing farming conditions, this also includes morally acceptable care and relationships with the animals kept (Wildraut and Mergenthaler, 2020). The results of our study show, however, that even farmers with a utilitarian attitude toward their pigs occasionally develop an emotional bond with them and consider their welfare to be important. These results are consistent with the findings of Bokkers (2006). They suggest that farmers’ positive attitudes toward animals may be a possible consequence of their economic dependence on them. In this context, animal performance and welfare are recognized as key factors for the success of the farm. However, it should be noted that this positive attitude is not shared by all farmers (Bokkers, 2006). The present study shows an association between the utilitarian attitude of livestock farmers toward their pigs and the occurrence of defensive behavior in pigs toward humans. The results of the study indicate that farmers’ attitudes toward their pigs are related to whether they view the pigs as a means of production or as individuals with whom they have a personal relationship. In addition, abnormal behaviors such as flank biting and mutual suckling occurred significantly less frequently in pigs whose behavior was not perceived as disturbing by livestock farmers or animal caretakers. These results are consistent with the findings of Waiblinger (1996), who describes a positive human-animal relationship as an essential aspect of animal welfare. The basis for a trusting human-animal relationship that benefits both parties is empathetic behavior on the part of humans (Mundjar and Theuermann, 2012). The evaluation of the integrated questionnaire according to Kellert (based on Schulz, 1986) showed that 94% of the livestock farmers surveyed have a utilitarian attitude toward animals and their habitat. In contrast, 5% of livestock farmers were found to have an emotional attitude and only 1% had a mixed attitude with elements of utilitarianism, naturalism, and moralism. It should be noted that almost two-thirds of participants (63%) did not answer Kellert’s questions or only answered them partially. The results of the study suggest that livestock farmers who have a utilitarian attitude according to Kellert’s classification nevertheless made some self-assessment statements that indicate an emotional attitude toward pigs. Wildraut and Mergenthaler (2020) have already pointed out that the human-animal relationship is characterized by an interplay between economic needs and the attribution of morality and emotionality to animals. The results suggest that livestock farmers with a utilitarian attitude keep their pigs exclusively in housing systems that meet minimum requirements. In this context, various aspects of housing conditions must be considered, particularly the type of flooring, the availability of enrichment materials, and access to outdoor areas. These pigs showed abnormal behavior such as tail biting or sham chewing more frequently and had more health problems, especially musculoskeletal disorders and cycle disorders, than pigs kept by livestock farmers with an emotional or a combination of moral, utilitarian, and naturalistic attitudes. According to Köhler (2005), health problems mainly result from errors in husbandry or farm management. In addition, Meyer et al. (2015) found that providing manipulable material for imitating feeding behavior has a positive influence on the behavior of pigs. It was found that only participants who displayed an emotional attitude stated that they kept their pigs in an open barn or free-range system. Armbrecht et al. (2015) concluded that providing outdoor access, as opposed to permanent housing, makes a significant contribution to improving animal welfare. Previous studies have already demonstrated the link between abnormal, stereotypical behavior and animal suffering and impaired well-being (Broom, 1999; Köhler, 2005). The present findings indicate that there are correlations between farmers’ attitudes and the housing conditions, welfare, and behavior of pigs. Furthermore, the findings suggest that the relationship between humans and animals can be understood as a dynamic process accompanied by social and economic factors. This leads to the conclusion that human-animal interaction is characterized by diverse interactions and conflicts in which emotions, ethical considerations, a sense of responsibility, and care can play a significant role. The results also indicate that a professional human-animal relationship does not necessarily go hand in hand with a lack of empathy or appreciation for farm animals. In order to further deepen existing knowledge and enable differentiated insights, targeted research projects are necessary to examine possible causal mechanisms. These should focus in particular on the attitudes of livestock farmers and their influence on husbandry conditions, as well as on the development of behavioral and health problems in the context of the economic situation of livestock farmers. The adaptation of international and national legislation must also be taken into account.

4.1 Limitations of the study

It should be noted that studies based on surveys of self-selected samples of participating livestock farmers are subject to the limitation that the results are only partially representative of the totality of livestock farmers in Germany due to self-selection (including voluntary participation and allocation to farms by breeding associations). However, the validity of these results is limited because the groups studied have specific characteristics, which may include, for example, an increased interest in animals or different demographic distributions. A sample of 485 people may be sufficient to identify trends within the sample. However, without clear random selection and weighting, it is unlikely that this sample can be considered reliably representative of pig farmers in Germany. It is often assumed that committed livestock farmers are more willing to take the time to participate in such studies. This finding could provide a theoretical explanation for part of the discrepancy between the subjective assessment of pig welfare as good and the actual situation regarding the prevalence of behavioral abnormalities. In addition, potential animal welfare problems related to the behavior and housing conditions of pigs were identified. Certain methodological aspects must be taken into account with regard to sample recruitment and data validity. For example, recruiting participants through professional associations can lead to systematic sample bias. The present study indicates that smaller agricultural businesses may not have been reached and are therefore underrepresented in the sample. This can lead to selection bias and limit the generalizability of the results to the entire target population. Furthermore, no measures were taken to prevent duplicate responses (e.g., through IP checks). This approach was intended to ensure the anonymity of respondents in order to allow participants to submit their responses in a protected environment. However, this means that duplicate responses are possible. In addition, there were limitations regarding sample size. The responses included in the study comprised all answered questions, including partially completed questionnaires. This led to missing values in some variables when evaluating the questionnaire data. As a result, sample sizes varied between analyses (e.g., PCA, chi-square test). The different sample size values result, on the one hand, from the handling of missing values (pairwise deletion) and, on the other hand, from different inclusion criteria for the respective analyses. These inequalities can impair the comparability of the findings and influence the stability of the PCA loadings and the test strength and bias risk in chi-square analyses. Another aspect that should be taken into account is the fact that the study is based on information provided by livestock farmers or pig caretakers. It should be noted that this information may be inaccurate to some extent for various reasons. These reasons include, for example, misunderstood questions leading to contradictory information or biases in the self-assessment of the reported behavior. It should be noted that self-reports may contain inaccuracies for various reasons, such as memory errors. However, self-reports have some advantages, for example, they are versatile, inexpensive, and allow the recording of behaviors that would otherwise be difficult or costly to observe, such as behavioral disorders. In this context, a potential methodological problem arising from social desirability must be taken into account. Within the context of this study, social desirability is defined as the propensity of livestock farmers to modify their responses in survey instruments to align with public perceptions. Since livestock farmers assessed both their own attitudes and the behavior of their pigs during data collection, self-reported information may have been distorted by social desirability or self-perception. This could have led to an overestimation or underestimation of certain behaviors or attitudes. Future studies could counteract this bias by using additional survey methods (e.g., behavioral observations or implicit measurement methods). In addition, there is a possibility that participants’ reports on animal behavior may be biased due to subjective views, as they cannot be confirmed by direct observation or video recordings by trained observers. For this reason, the behaviors to be recorded in the questionnaire were described objectively and clearly. In addition, no mandatory questions were included, which led to a varying sample size. However, a mandatory response would have increased the risk that participants would not complete the questionnaire in full and could have compromised the quality of the responses. It is acknowledged that some of the results presented are based on reported trends, but it is assumed that these findings may be useful for future research projects. Investigating these patterns with larger samples or through direct behavioral observations could confirm or refine our conclusions. Due to the epidemiological data collection, only statistically significant correlations were examined. Therefore, no definitive conclusions about cause-and-effect relationships can be drawn from the research design of this study.

5 Conclusion

The study results show significant correlations between the attitudes of livestock farmers, husbandry conditions, the welfare of pigs, and the occurrence of behavioral abnormalities and health problems in pigs. The occurrence of abnormal behavior was less common in smaller herds with a maximum of 300 pigs compared to larger pig farms. A predominantly utilitarian attitude was negatively associated with the human-animal relationship and the welfare and behavior of the pigs. In this study, an emotional or mixed attitude among livestock farmers was associated with improved animal welfare. This was reflected in increased well-being among the pigs, which was evident in a lower frequency of behavioral abnormalities, the expression of natural behaviors when access to outdoor areas was provided, and a lower prevalence of disease.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Permission to use and store the anonymized data sets for the purposes of this retrospective study (online survey) was obtained digitally from all respondents. Completion of the questionnaire was only permitted on condition that the collection and publication of the anonymized data sets was agreed to. According to Section 15 (1) of the German Professional Code of Conduct for Doctors, no approval by an ethics committee is required for purely retrospective epidemiological research projects involving anonymous data collection. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

JG: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. FK: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Software, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all participants for their support in disseminating our online survey. We would also like to thank all livestock farmers for participating in this study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fanim.2025.1651310/full#supplementary-material.

References

Armbrecht L., Lambertz C., Albers D., and Gauly M. (2015). “Animal welfare of dairy cows in indoor and outdoor housing – A comparison based on the Welfare Quality Protocol,” in Animal husbandry in the conflict between animal welfare, economics and society: Animal welfare conference in Göttingen, 1st ed. Eds. Gieseke D., Busch G., Ikinger C., Kühl S., and Pirsch W. (Góttingen, Germany: Georg August University Department of Agricultural Ecology and Rural Development), 70–74.

Animal Welfare Livestock Farming Ordinance (2006). Federal Ministry of Justice and Consumer Protection, Federal Office of Justice. Available online at: https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/tierschnutztv/ (Accessed January 25, 2025).

Pig Protection Directive, (2008/120/EC): Council Directive 2008/120/EC of 18 December 2008 concerning the minimum standards for the protection of pigs. Available online at: http://data.europa.eu/eli/dir/2008/120/oj (Accessed January 15, 2025).

Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data, and repealing Directive 95/46/EC (General Data Protection Regulation). Available online at: https://gdpr-info.eu (Accessed November 17, 2024).

BMEL statistics (2024). Pig farming. Available online at: https://www.bmel-statistik.de/landwirtschaft/tierhaltung/schweinehaltung (Accessed September 23, 2024).

Bokkers E. A. (2006). “Effects of interactions between humans and domesticated animals,” in Wageningen UR Frontis series / Frontis, Wageningen International Nucleus for Strategic Expertise, Wageningen University and Research Centre: Vol. 13. Farming for health: Green-care farming across Europe and the United States of America. Ed. Hassink J. (Springer Publishing), 31–41. doi: 10.1007/1-4020-4541-7_3

Borell E. and Huesmann K. (2009). Requirements for stable flooring (KTBL, Darmstadt: Board of Trustees for Technology and Construction in Agriculture (KTBL). Available online at: https://www.ktbl.de/fileadmin/user_upload/Artikel/Tierhaltung/Schwein/Allgemein/Stallboden-Anforderungen/Stallboden-Anforderungen.pdf (Accessed January 26, 2025).

Broom D. M. (1986). Indicators of poor welfare. Br. Vet. J. 142, 524–526. doi: 10.1016/0007-1935(86)90109-0

Broom D. M. (1999). Animal welfare: the concept and the issues. In: Dolins F. L. (ed.), Attitudes to Animals: Views in Animal Welfare, pp. 129–142. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. (Accessed March 1, 2025).

European Food Safety Authority (2007). The risks associated with tail biting in pigs and possible means to reduce the need for tail docking considering the different housing and husbandry systems - Scientific Opinion of the Panel on Animal Health and Welfare. EFSA J. 5, 611. doi: 10.2903/j.efsa.2007.611

Federal Statistical Office (2020). Individual publication on the 2020 agricultural census. Available online at: https://www.destatis.de/DE/Themen/Branchen-Unternehmen/Landwirtschaft-Forstwirtschaft-Fischerei/Produktionsmethoden/Publikationen/Downloads-Produktionsmethoden/stallhaltung-weidehaltung-tb-5411404209004.pdf?blob=publicationFile&v=6 (Accessed March 3, 2025).

Fels M. (2019). New findings on animal welfare aspects in pig farming using planimetric and ethological methods. University of Veterinary Medicine Hannover, VVB Laufersweiler, ISBN: 978-3-8359-6840-0.

Fraser D. (2008). Understanding animal welfare. Acta Veterinaria Scandinavica 50, 1. doi: 10.1186/1751-0147-50-S1-S1

Fraser D., Weary D. M., Pajor E. A., and Milligan B. N. (1997). A scientific conception of animal welfare that reflects ethical concerns. Anim. Welfare 6, 187–205. doi: 10.1017/S0962728600019795

Hahn J. and Kari A. (2021). Do farm animals suffer from their living conditions? – Determining suffering in animal welfare criminal proceedings. Nat. Law 43, 599–607. doi: 10.1007/s10357-021-3890-7

Jathe N. (2017). Development and testing of a technical rooting facility for intensively reared fattening pigs. German National Library. Available online at: https://urn.fi/urn:nbn:de:hebis:34-2017110253706.

Kellert S. R. (1976). Perceptions of animals in American society: Transactions of the 41. North Am. wildlife Natural Resour. Conf., 533–546.

Kellert S. R. (1980). “Contemporary values of wildlife in American society,” in Institutional Series Report, 1. Wildlife Values. Eds. Shaw W. W. and Zube E. H. (Center for Assessment of Noncommodity Natural Resource Values), 241–267.

Kellert S. R. (1984). “American attitudes toward and knowledge of animals: An update,” in Advances. Eds. Fox M. W. and Mickley L. D. (Washington, DC: The Humane Society of the United States. Humane Society Institute for Science and Policy Animal Studies Repository), 177–213. Available online at: https://ges.research.ncsu.edu/wpcontent/uploads/2014/03/Kellert1984_AttitudesUpdate.pdf?file=2014/03/Kellert1984_AttitudesUpdate.pdf (Accessed December 6, 2024).

Kellert S. R. (1993b). Attitudes, knowledge, and behavior toward wildlife among the industrial superpowers: United States, Japan, and Germany. J. Soc. Issues 49, 53–69. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.1993.tb00908.x

Köhler F. M. (2005). The welfare of farm animals: findings from animal science and social attitudes. Christian Albrecht University of Kiel: Faculty of Agricultural and Nutritional Sciences.

Mayer C., Hillmann E., and Schrader L. (2006). “Behaviour, attitude, evaluation of housing systems: pages 94–120,” in Pig breeding and pork production: Recommendations for practice, vol. 296 . Eds. Brade W. and Flachowsky G. (Braunschweig. Federal Research Centre for Agriculture (FAL), 247. Available online at: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Mees U. (2006). “Zum Forschungsstand der Emotionspsychologie – eine Skizze,” in Emotionen und Sozialtheorie. Disziplinäre Ansätze. Ed. Schützeichel R. (Campus, Frankfurt).

Meyer E., Menzer K., and Henke S. (2015). Evaluation of suitable options for reducing the occurrence of behavioural disorders in pigs (Special issue 19) (Dresden: Braunschweig: Saxon State Office for Environment, Agriculture and Geology (LfULG). Available online at: https://publikationen.sachsen.de/bdb/artikel/25186 (Accessed January 30, 2025).

Mondon M., Thöne-Reineke C., and Merle R. (2017). Tierwohl und Wohlbefinden – Definition, Bewertung und Diskussion mit Fokussierung auf die Milchkuh. Berl. Münch. Tierärztl. Wschr 130. doi: 10.2376/0005-9366-16080

Mouttotou N., Hatchell F. M., and Green L. E. (1999). Foot lesions in finishing pigs and their associations with the type of floor. Veterinary Rec 144, 629–632. doi: 10.1136/vr.144.23.629

Mundjar M. and Theuermann M. (2012). Special features of the human-animal relationship: A critical examination of educationally relevant aspects. Graz, Univ. Available online at: https://resolver.obvsg.at/urn:nbn:at:at-ubg:1-44535.

Schmitz L., Kemnade M., and Mergenthaler M. (2024). Ausgewählte Sichtweisen von Landwirtinnen und Landwirten auf die Nutztierhaltung in Deutschland. J. Consumer Prot. Food Saf. 19, 69–74. doi: 10.1007/s00003-024-01491-y

Schulz W. (1986). “Attitudes toward wildlife in West Germany,” in Valuing Wildlife. Eds. Decker D. J. and Goff G. R. (Westview, Boulder, USA), 352–354.

Spezial Eurobarometer 410 (2014).Europäer, Landwirtschaft und Gemeinsame Agrarpolitik (GAP). Bericht. Europäische Kommission, Generaldirektion Landwirtschaft und ländliche Entwicklung. Available online at: https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/surveys/detail/1081 (Accessed October 19, 2025).

Spiller A., Gauly M., Balmann A., Bauhus J., Birner R., Bokelmann W., et al. (2015).Wege zu einer gesellschaftlich akzeptierten Nutztierhaltung. Available online at: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ (Accessed August 29, 2025).

Sundrum A. (2018). Assessment of animal welfare performance in livestock farming. Journal of Agricultural Policy and Agriculture 96, 1–33. doi: 10.12767/buel.v96i1.189

Sundrum A. (2020). Tail biting – a systemic problem. (Schlütersche Verlagsgesellschaft, Hanover: Vetline). doi: 10.2376/0032-681X-2046

Waiblinger S. (1996). The human-animal relationship in the free-range housing of horned dairy cows. Animal husbandry: Vol. 24 (Witzenhausen: Department of Farm Animal Ethology and Species-Appropriate Animal Husbandry, University of Kassel), ISBN: 3-88122-871-3.

Wildraut C. and Mergenthaler M. (2020). Human-animal relationships as a starting point for socially acceptable livestock farming. Journal of Agricultural Policy and Agriculture 98, 1–34. doi: 10.12767/BUEL.V98I3.298

Keywords: pig farming, animal welfare, abnormal behavior, farm husbandry, human-livestock relationship

Citation: Gebert J and Kuhne F (2025) Welfare, behavior, and housing conditions of pigs, considering the basic attitudes of pig farmers in Germany. Front. Anim. Sci. 6:1651310. doi: 10.3389/fanim.2025.1651310

Received: 21 June 2025; Accepted: 24 October 2025;

Published: 08 December 2025.

Edited by:

Peter Sandøe, University of Copenhagen, DenmarkReviewed by:

Yi-Chun Lin, National Chung Hsing University, TaiwanJulia Dorothée Kschonek, University of Veterinary Medicine Hannover, Germany

Copyright © 2025 Gebert and Kuhne. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Julia Gebert, ai5zb2htQGdteC5kZQ==

Julia Gebert

Julia Gebert Franziska Kuhne

Franziska Kuhne