Abstract

This study evaluated the effects of dietary top-coating supplementation with Wedelia chinensis extract on growth performance, innate immune responses, and disease resistance in whiteleg shrimp (Penaeus vannamei) challenged with Vibrio parahaemolyticus. Shrimp were fed a basal diet top-coated with W. chinensis extract at inclusion levels of 31.25, 312.5, or 625 mg kg-1 feed using an intermittent feeding protocol over a 21-day period, while a control group received the unsupplemented basal diet. Growth performance indicators, including weight gain and feed conversion ratio, were significantly improved in shrimp fed extract-supplemented diets, with the most pronounced effects observed at the intermediate inclusion level. In addition, many key innate immune parameters, including total hemocyte count, phagocytic activity, phenoloxidase, lysozyme, and superoxide dismutase activities, were significantly elevated compared with the control group. Following pathogen challenge, shrimp fed W. chinensis–supplemented diets exhibited significantly reduced mortality, indicating enhanced resistance to V. parahaemolyticus. Overall, the results suggest that dietary supplementation with W. chinensis extract can beneficially modulate growth performance and innate immune responses in whiteleg shrimp. Further studies are warranted to elucidate the underlying mechanisms, identify active compounds, and evaluate long-term efficacy under commercial farming conditions.

1 Introduction

The whiteleg shrimp Penaeus vannamei is currently the most important farmed shrimp species worldwide, with global production reaching nearly 7 million tons in 2022 (FAO, 2024). It plays a critical role in the aquaculture industries of Southeast Asia, the Americas, and other regions, generating substantial economic value annually (Shekhar et al., 2021). Despite its global importance, shrimp aquaculture remains highly vulnerable to disease outbreaks, among which acute hepatopancreatic necrosis disease (AHPND) is one of the most devastating. First reported in China in 2009, AHPND has since spread widely across Asia and the Americas. The disease typically occurs within 20–30 days after stocking and is frequently associated with mass mortalities that can reach nearly 100% (Lai et al., 2015; Kumar et al., 2020; Han et al., 2015; OIE, 2019, OIE, 2020). AHPND is primarily caused by Vibrio parahaemolyticus strains carrying the pVA1 plasmid encoding the PirA and PirB toxins, which induce severe pathological damage to the stomach and hepatopancreas of shrimp (Lee et al., 2015; Dong et al., 2017; Han et al., 2017; Tang et al., 2020). In addition, other Vibrio species, including V. harveyi, V. owensii, V. campbellii, and V. punensis, have also been associated with AHPND-like outbreaks (Liu et al., 2015, Liu et al., 2018; Ahn et al., 2017; Restrepo et al., 2018).

The management of bacterial diseases in shrimp farming has conventionally relied on the use of antibiotics and disinfectants (De Schryver et al., 2014; Boonyawiwat et al., 2017). However, the excessive and prolonged application of these chemotherapeutics has contributed to environmental contamination and the emergence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria, including AHPND-causing V. parahaemolyticus strains (Seyfried et al., 2010; Lulijwa et al., 2020; Knipe et al., 2021). Resistance to commonly used antibiotics, such as ampicillin, streptomycin, and sulfamethoxazole has been widely reported (Lai et al., 2015; Han et al., 2015), underscoring the urgent need for sustainable, antibiotic-free strategies to improve shrimp health and disease resistance.

In this context, plant-derived bioactive compounds have gained increasing attention as functional feed additives in aquaculture. Numerous plant extracts contain polyphenols, flavonoids, terpenoids, and alkaloids with antimicrobial, antioxidant, and immunomodulatory properties (Reverter et al., 2014; Chandran et al., 2016; Angela et al., 2020; Zhu, 2020; Effendi et al., 2022; Li et al., 2022; Kumar et al., 2023). In addition, certain phytogenic additives have been reported to enhance feed palatability and nutrient utilization, thereby improving growth performance (Venketramalingam et al., 2007; Kirubakaran et al., 2010).

Wedelia chinensis (Asteraceae) is a widely distributed medicinal herb in Asia and is rich in polyphenols, flavonoids, diterpenoids, sesquiterpenes, and triterpenoids (Li et al., 2012; Khan et al., 2023). Extracts from this plant have demonstrated antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and broad-spectrum antimicrobial activities in both in vitro and in vivo studies (Manjamalai et al., 2012; Talukdar and Talukdar, 2013; Li et al., 2022; Khan et al., 2023; Nguyen et al., 2023). In our previous in vitro study, methanolic extracts of W. chinensis exhibited the highest total polyphenol and flavonoid contents and showed strong inhibitory activity against pathogenic V. parahaemolyticus compared with extracts obtained using other solvents (Tran et al., 2022). Building on these findings, the present study aimed to evaluate the effects of dietary supplementation with methanolic W. chinensis extract on growth performance, innate immune responses, and resistance of P. vannamei against V. parahaemolyticus infection under controlled in vivo conditions.

By improving shrimp health and survival while reducing dependence on antibiotics, functional plant-based feed additives, such as W. chinensis extract, can contribute to more sustainable aquaculture practices. These approaches support global efforts toward food security, responsible production, and ecosystem health, aligning with several United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, including Zero Hunger (SDG 2), Responsible Consumption and Production (SDG 12), and Life Below Water (SDG 14).

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Preparations of the W. chinensis extract

Fresh Wedelia chinensis plants were collected from Hue city (formerly Thua Thien Hue Province), Vietnam. Leaves were washed thoroughly with distilled water and dried at 60 °C for 8 h. The extraction procedure followed Appiah et al. (2022); Hang et al. (2018), with minor modifications. The dried leaves were ground into fine powder (particle size 250 µm) using a laboratory grinder (PG, SGE, Thailand). Thirty grams of the powdered material were extracted with 300 mL methanol (99.8% v/v) and heated in a water bath (JEIOTECH BW-1020H, Korea) at 70 °C for 1 h. The mixture was filtered through Whatman Grade No.2 filter paper, and the filtrate was concentrated under reduced pressure at 60 °C using a rotary evaporator (Rotavapor R-300, Switzerland) to completely remove residual solvent. Following complete methanol evaporation under reduced pressure, the resulting dried extract was reconstituted in a minimal and defined volume of distilled water solely to facilitate homogeneous mixing prior to downstream applications. This reconstitution step was performed after solvent removal, ensuring that the extraction and concentration of bioactive compounds were completed before aqueous exposure, thereby minimizing any potential alteration of the extract composition. The resulting extract was stored at −20 °C until use.

2.2 Preparations of experimental diets

Four experimental diets were prepared, including a control diet without W. chinensis extract (WCE) and three test diets supplemented with WCE at 31.25, 312.5, or 625 mg kg-1 of feed. The inclusion levels were selected based on previous evaluations of antimicrobial activity and toxicity (Ngoc et al., 2023). All experimental diets shared an identical basal formulation, differing only in the level of WCE applied by surface top-coating. The formulation of the basal diet used in this study was adapted from Hong et al. (2022), Won et al., (2020). To accommodate the supplementation of WCE, the diets were prepared with slight modifications. Specifically, levels of calcium dihydrogen phosphate and corn starch were adjusted to maintain mineral balance and pellet stability after WCE supplementation, ensuring all diets remained nutritionally comparable, as shown in Supplementary Table S1. Briefly, the dry ingredients were thoroughly mixed and sieved (250 µm), followed by the addition of fish oil and water to form a homogeneous dough. Pellets (0.5–1.0 mm diameter) were produced using a laboratory pelleting machine (3A, Vietnam), air-dried for 72 h, and stored at 4 °C until use. For WCE supplementation, the extract was dissolved in a minimal volume of distilled water and evenly sprayed onto the basal diet pellets using a fine mist sprayer while the pellets were continuously tumbled in a rotating drum for 10 min. Following this, the same volume of squid oil was added as a coating agent to all experimental diets, including the control. This step ensured consistent lipid composition across all the experimental diets, avoided confounding effects related to lipid composition and enhanced the adhesion of the extract to minimize leaching. Mixing was continued for an additional 5 min after oil addition. The basal (control) diet underwent identical spraying, coating, and mixing procedures as the WCE-supplemented diets but without WCE supplementation. All experimental diets were formulated to be nutritionally comparable, and WCE was the only variable factor among treatments. Minor formulation adjustments were necessary to accommodate graded WCE inclusion; however, all diets remained nutritionally comparable. The coated pellets were air-dried at room temperature for 2 h and subsequently stored in airtight bags at 4 °C until feeding.

2.3 Experimental animal and design

Whiteleg shrimp juveniles (P. vannamei) with a mean body weight of 1.5 ± 0.1 g were obtained from Toan Tien Hatchery (Hue city, Vietnam). Prior to transfer, shrimp batches were screened for acute hepatopancreatic necrosis disease (AHPND), white spot disease (WSD), and yellow head disease (YHD) at the Hue Veterinary Clinic using PCR assays targeting Vibrio parahaemolyticus for AHPND, WSSV for WSD, and YHV for YHD, following protocols recommended by the World Organization for Animal Health (OIE). Only batches that tested PCR-negative for all pathogens were used for the experiment.

Upon arrival at the laboratory, shrimp were acclimatized for 14 days in a 1000 L plastic tank with a flow-through seawater system (1.4 L s-1) under controlled conditions: temperature 28 ± 2 °C, pH 7.6–8.0, salinity 20–25‰, and dissolved oxygen ≥ 5.0 mg L-1. Water quality parameters (temperature, pH, and salinity) were monitored daily using a multiparameter probe (YSI ProDSS, USA), while total ammonia nitrogen, nitrite, and alkalinity were measured weekly. Partial water exchange (20% of tank volume) and continuous aeration were applied to maintain optimal water quality. Shrimp were fed the basal diet four times daily at 07:00, 10:00, 13:00, and 16:00 h. Uneaten feeds, waste, and dead shrimp were removed two hours after each feeding session.

Before starting the feeding trial, hepatopancreas samples from five randomly selected shrimp were streaked onto thiosulfate citrate bile salts (TCBS, Himedia, India) agar and incubated at 28 °C for 24 h. No Vibrio-like colonies were observed, and the absence of V. parahaemolyticus was further confirmed by PCR analysis (Phuoc et al., 2021). A total of 600 juveniles were randomly assigned to 12 plastic tanks (capacity 120 L; working volume 100 L) supplied with continuous aeration and flow-through seawater (1.4 L s-1), at a stocking density of 50 shrimp per tank. The experiment consisted of four dietary treatments: a control group fed the basal diet without supplementation, and three treatment groups fed basal diets top-coated with W. chinensis extract at inclusion levels of 31.25, 312.5, and 625 mg kg-1 feed (designated as WCE-31.25, WCE-312.5, and WCE-625), each with three replicates.

Shrimp were fed according to an intermittent feeding regimen over a 21-day experimental period, consisting of 7 days of WCE-supplemented feeding, followed by 7 days of basal diet feeding, and a final 7 days of WCE-supplemented feeding. The control group received the basal diet continuously throughout the trial. The intermittent feeding strategy was designed to assess immune stimulation while minimizing potential metabolic or immunological stress associated with prolonged continuous exposure to the extract.

Shrimp were fed four times daily at 3–5% of body weight per day. Uneaten feed, feces, and dead shrimp were removed by siphoning two hours after each feeding. Water quality parameters were monitored regularly and remained within the optimal range for whiteleg shrimp throughout the experimental period. At the end of the 21-day feeding trial, 20 shrimp per replicate were collected for a challenge test with pathogenic V. parahaemolyticus. Additionally, six shrimp per group (two shrimp per replicate) were sampled to determine phagocytic activity. For the evaluation of innate immune parameters, including total hemocyte count, superoxide dismutase activity, lysozyme activity, and phenoloxidase activity, six shrimp per treatment group were sampled on days 0, 7, 14, and 21.

2.4 Growth performance and survival analysis

At the end of the feeding trial, the shrimp were deprived of feed for 24 h, after which they were counted and individually weighed. Growth performance and survival parameters, including specific growth rate (SGR), weight gain (WG), feed conversion ratio (FCR), and survival rate (SR), were calculated based on initial and final body weights and shrimp numbers according to the formulas described by Chandran et al. (2016), as outlined below:

SGR =

2.5 Hemolymph sampling

Hemolymph (100 μL) was collected from six shrimp per experimental group at each sampling time point. The collected hemolymph was immediately diluted 1:9 (v/v) with anticoagulant solution, resulting in a 1:9 (v/v) hemolymph dilution for subsequent immune assays. This dilution ratio was consistently applied to all immune parameter analyses to ensure comparability among treatments. The hemolymph samples were drawn from the ventral sinus using a sterile 1-mL syringe preloaded with 900 μL of anticoagulant solution (30 mM trisodium citrate, 0.34 M NaCl, and 10 mM EDTA; osmolality adjusted to 780 mOsm kg-1; pH 7.5). The collected samples were immediately used for the analysis of innate immune parameters.

2.5.1 Total hemocyte count

Total hemocyte count was measured using the protocol described previously by Chiu et al. (2007). Briefly, a drop of diluted hemolymph was loaded onto a Neubauer improved hemocytometer (Marienfeld, USA) and examined under a light microscope (CX23; Olympus, Japan) at 400× magnification. Hemolymph was diluted (1:9 v/v) in anticoagulant solution prior to hemocyte counting, and total hemocyte counts were expressed as cells mL-1.

2.5.2 The phagocytic activity of hemocytes

The phagocytic activity of hemocytes was determined following the methods described by Hong et al. (2022). Shrimp were injected with 20 uL of a bacterial suspension of V. parahaemolyticus (2×106 CFU mL-1, corresponding to the LD50 dose), and then placed in separate tanks containing 50 L of seawater (salinity 20‰) at 28 ± 1 °C for 2 h.

Hemolymph (100 μL) was collected from six shrimp in each experimental group and mixed with 900 µL of an anticoagulant solution. For hemocyte fixation, 100 µL of the anticoagulant-hemolymph mixture was mixed with an equal volume of 0.1% paraformaldehyde for 30 min at 4 °C. Subsequently, 50 µL of the fixed cell suspension was dropped onto a glass slide and centrifuged at 113 × g for 3 minutes using a cytospin centrifuge. After air-drying, the slides were stained with Diff-Quick stain.

The phagocytic activity was determined under a light microscope (CX23; Olympus, Japan) by counting 200 hemocytes per slide and recording the number of cells that had engulfed bacterial cells. Phagocytic activity (PA) was calculated using the following formula:

2.5.3 Phenoloxidase activity

Phenoloxidase (PO) activity was determined by measuring the formation of dopachrome produced from L-DOPA at an OD of 490 nm using a spectrophotometer (V1710, Shanghai, China) following the method outlined by Hong et al. (2022). Briefly, 100 μL of the anticoagulant-hemolymph mixture was centrifuged at 800 × g for 20 min at 4 °C, and the supernatant was discarded. The hemocyte pellet was washed with 500 μL cacodylate citrate buffer (10 mM sodium cacodylate, 450 mM sodium chloride, and 100 mM trisodium citrate; pH 7.0) and resuspended in 100 μL cacodylate buffer (10 mM sodium cacodylate, 450 mM sodium chloride, 10 mM calcium chloride, and 260 mM magnesium chloride; pH 7.0). The hemocyte suspension was divided into two equal aliquots. One aliquot was treated with 50 μL of trypsin (1 mg mL-1) to activate the prophenoloxidase system, while the other received 50 μL of cacodylate buffer and served as a control. After incubation at 25 °C for 10 min, 50 μL of L-DOPA was added to each tube and allowed to react for 5 min. The reaction was terminated by adding 800 μL of cacodylate buffer, resulting in a final reaction volume of 1 mL. Absorbance was then measured at 490 nm.

2.5.4 Lysozyme activity

Lysozyme activity was determined following the procedures described by Chiu et al. (2007). Briefly, 500 µL of the anticoagulant-hemolymph mixture was centrifuged at 1,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C to obtain the cell-free supernatant. The supernatant was then mixed with 1 mL of a 0.02% (w/v) suspension of Micrococcus lysodeikticus (Sigma-Aldrich) and incubated at 25 °C. Absorbance was measured at 530 nm at 0.5 and 4.5 min using a spectrophotometer. One unit of lysozyme activity (U) was defined as the quantity of enzyme required to decrease the absorbance by 0.001 per minute, and the LYS activity was expressed as units per milliliter (U mL-1).

2.5.5 Superoxide dismutase

Superoxide dismutase activity was measured using a commercial assay kit (CS0009, Sigma-Aldrich, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, the anticoagulant–hemolymph mixture was centrifuged at 1,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C, and the supernatant was collected and stored at −80 °C until analysis. A standard curve was generated using the SOD standard provided in the kit, with a linear detection range of 0.3–6.0 U mL-1. The assay was conducted in a 96-well microplate and included appropriate controls: (i) a no-SOD control to determine maximum absorbance, (ii) a no–xanthine oxidase control to assess background signal, and (iii) a blank control to correct baseline absorbance. For each well, shrimp serum or dilution buffer was added as appropriate, followed by the addition of WST working solution. The reaction was initiated by adding xanthine oxidase working solution, except in the no–xanthine oxidase and blank controls. After incubation at 20–25 °C for 30 min, absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader. All samples and controls were analyzed in triplicate. One unit of SOD activity was defined as the amount of enzyme required to inhibit 50% of superoxide radical formation, and SOD activity was expressed as units per milliliter (U mL-1).

2.6 Shrimp challenge experiment

2.6.1 Bacterial preparation

An AHPND-causing V. parahaemolyticus strain, originally isolated from diseased whiteleg shrimp (P. vannamei) cultured in Hue city, Vietnam, was used for the challenge experiment. The strain was obtained from the Laboratory of Fish Pathology, Hue University, Vietnam. A single colony grown on thiosulfate citrate bile salts sucrose (TCBS) agar was inoculated into 10 mL of Tryptone Soya Broth (TSB; HiMedia, India) supplemented with 1.5% NaCl and incubated at 28 °C for 24 h under gentle shaking. Following incubation, the bacterial culture was centrifuged at 3,000 × g for 20 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was discarded, and the resulting bacterial pellet was resuspended in sterile 0.85% saline solution to obtain a target concentration of approximately 1 × 106 CFU mL-1, corresponding to the LD50 dose. The bacterial concentration was subsequently verified by plate counting using the method described by Miles et al. (1938). The LD50 value was determined in a preliminary challenge trial (data not shown).

2.6.2 Challenge test

After 21 days of feeding, shrimp from all the experimental groups (20 shrimp per tank × 3 tanks per treatment, which is equivalent to 60 shrimp per treatment) were subjected to a V. parahaemolyticus challenge by immersion for 30 min. The challenge was performed using the LD50 dose (1.05 × 106 CFU mL-1, as determined by viable plate counting) in 10 L of seawater with a salinity of 20 ppt, maintained at 28 °C. Continuous aeration was provided to each tank, and the shrimp were fed a basal diet four times daily at 3% of body weight. The challenge test was conducted to compare relative disease resistance among shrimp previously fed different diets under standardized pathogen exposure. An unchallenged negative control was not included, as shrimp survival without pathogen exposure had already been confirmed during the feeding trial. The primary objective of this experiment was to evaluate differential survival responses among dietary treatments following infection. The hepatopancreas samples from moribund shrimp and from 50% of the surviving shrimp at the end of the experiment were collected for bacteriological analysis. Phenotypic confirmation of V. parahaemolyticus was performed using CHROMagar™ Vibrio selective media (Lee et al., 2020). At the end of the challenge experiment, the cumulative mortality percentage (%) was calculated, and the relative percentage of survival (RPS) was determined following the method of Amend (1981):

2.7 Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 22.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA), with significance level set at p < 0.05. Data normality and homogeneity of variances were assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk and Levene’s tests, respectively. When assumptions were met, one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s HSD post-hoc test was used to compare means among treatments. Survival data were analyzed using the log-rank (Mantel–Cox) test in GraphPad Prism v9.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA).

3 Results

3.1 Effect of dietary WCE on growth performance of whiteleg shrimp

Dietary supplementation with W. chinensis extract significantly influenced the growth performance of whiteleg shrimp (Table 1). Shrimp fed WCE-supplemented diets exhibited significantly higher final body weight, daily weight gain, and SGR compared with the control group (p < 0.05). The most pronounced improvements were observed in the WCE-312.5 and WCE-625 groups, which did not differ significantly from each other. FCR was significantly reduced in all WCE-fed groups relative to the control (p < 0.05). The lowest FCR values were recorded in the WCE-312.5 and WCE-625 groups, whereas the WCE-31.25 group showed an intermediate reduction. Survival rate did not differ significantly among dietary treatments (p > 0.05).

Table 1

| Parameters | Experimental groups | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | WCE-31.25 | WCE-312.5 | WCE-625 | |

| Initial weight (g shrimp-1) | 0.55 ± 0.03a | 0.53 ± 0.07a | 0.57 ± 0.04a | 0.54 ± 0.04a |

| Final weight (g shrimp-1) | 4.02 ± 0.07a | 4.67 ± 0.07b | 5.82 ± 0.09c | 5.87 ± 0.09c |

| Weight gain (g shrimp-1) | 3.46 ± 0.07 a | 4.16 ± 0.05 b | 5.27 ± 0.09c | 5.32 ± 0.09c |

| Daily weight gain (DWG, g day-1) | 0.11 ± 0.06a | 0.15 ± 0.03b | 0.18 ± 0.05c | 0.19 ± 0.06c |

| Specific growth rate (SGR, % day-1) | 6.56 ± 0.04a | 7.12 ± 0.05b | 7.86 ± 0.05c | 7.92 ± 0.04c |

| Feed conversion rate (FCR) | 1.40 ± 0.03a | 1.16 ± 0.04b | 1.06 ± 0.02c | 1.08 ± 0.03c |

| Survival rate (SR, %) | 85.33 ± 3.33a | 87.56 ± 1.92a | 90.44 ± 3.85a | 89.20 ± 3.85a |

Growth performance of whiteleg shrimp fed diets supplemented with different levels of W. chinensis extract.

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) of triplicate tanks (n = 3).

Different lowercase letters within the same row indicate significant differences among dietary treatments (one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test, p < 0.05).

The control group received the basal diet without WCE. The experimental diets were supplemented with WCE at 31.25 mg kg-1 (WCE-31.25), 312.5 mg kg-1 (WCE-312.5), and 625 mg kg-1 feed (WCE-625).

3.2 Effect of dietary WCE on the innate immune response of whiteleg shrimp

3.2.1 Total hemocyte count

The total hemocyte count (THC) in the shrimp before feeding with WCE-supplemented diets was 75 x 106 cells mL-1 (Table 2). THC remained stable in the control group throughout the 21-day experimental period, whereas a significant increase was observed in all WCE-fed groups from day 7 onward (p < 0.05). No differences among the WCE-fed groups were observed on day 7; however, on days 14 and 21, the highest THC value was recorded in the WCE-312.5 group, which did not differ significantly from the WCE-625 group.

Table 2

| Experimental groups | Total hemocyte count (106 cells mL-1) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 0 | Day 7 | Day 14 | Day 21 | |

| Control | 74.6 ± 2.0aA | 73.5 ± 2.0aA | 75.6 ± 2.0aA | 73.4 ± 4.0aA |

| WCE-31.25 | 73.5 ± 3.0aA | 82.0 ± 4.0bB | 81.8 ± 5.0bB | 86.2 ± 4.0bB |

| WCE-312.5 | 77.4 ± 4.0aA | 90.8 ± 6.0bB | 93.3 ± 4.0bC | 97.5 ± 5.0bC |

| WCE-625 | 74.5 ± 2.0aA | 90.0 ± 4.0bB | 89.3 ± 3.0bC | 96.6 ± 5.0bC |

Total hemocyte count in whiteleg shrimp fed different experimental diets.

Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3 tanks per treatment). Within the same column (same sampling day), different lowercase letters indicate significant differences among dietary treatments (p < 0.05). Within the same row (same treatment), different uppercase letters indicate significant differences among sampling days (p < 0.05).

3.2.2 The phagocytic activity of hemocytes

Phagocytic activity of hemocytes in the control group remained stable throughout the experimental period, with no significant changes observed from day 0 to day 21 (Table 3). In contrast, shrimp fed WCE-supplemented diets showed significantly higher activity from day 7 onward compared with both their initial values (day 0) and the control group at the corresponding time points (p < 0.05). No significant differences in phagocytic activity were found among the different WCE inclusion levels at any of the tested sampling time points.

Table 3

| Experimental groups | The phagocytic activity of hemocytes (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 0 | Day 7 | Day 14 | Day 21 | |

| Control | 89.0 ± 2.0aA | 89 ± 3.0aA | 88 ± 4.2aA | 89 ± 1.9aA |

| WCE-31.25 | 88.0 ± 3.0aA | 99 ± 0.4bB | 99 ± 0.5bB | 99 ± 0.9bB |

| WCE-312.5 | 91.0 ± 1.0aA | 99 ± 1.2bB | 99 ± 0.9bB | 99 ± 1.3bB |

| WCE-625 | 89.0 ± 2.0aA | 98 ± 1.0bB | 98 ± 0.8bB | 98 ± 0.5bB |

Phagocytic activity of hemocytes in whiteleg shrimp fed different experimental diets.

Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3 tanks per treatment). Within the same column (same sampling day), different lowercase letters indicate significant differences among dietary treatments (p < 0.05). Within the same row (same treatment), different uppercase letters indicate significant differences among sampling days (p < 0.05).

3.2.3 Phenoloxidase activity

The phenoloxidase (PO) activity in the shrimp before the start of the feeding trial (day 0) and that of those fed a control diet for 21 days did not show significant variation (Table 4). However, shrimp fed WCE-supplemented diets showed a significant increase in PO activity from day 7 onward compared with both their initial values and the control group (p < 0.05). On day 7, the highest PO activity was observed in the WCE-312.5 group, which did not differ significantly from the WCE-31.25 group. The WCE-625 group did not show further enhancement and exhibited significantly lower PO activity than the WCE-31.25 and WCE-312.5 groups at all sampling time points.

Table 4

| Experimental groups | Phenoloxidase activity | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 0 | Day 7 | Day 14 | Day 21 | |

| Control | 0.178 ± 0.003aA | 0.176 ± 0.002aA | 0.177 ± 0.003aA | 0.180 ± 0.004aA |

| WCE-31.25 | 0.181 ± 0.005aA | 0.243 ± 0.012bC | 0.245 ± 0.007bC | 0.241 ± 0.005 bC |

| WCE-312.5 | 0.179 ± 0.004aA | 0.249 ± 0.009bC | 0.247 ± 0.008bC | 0.251 ± 0.006bC |

| WCE-625 | 0.180 ± 0.006aA | 0.215 ± 0.002bB | 0.218 ± 0.011bB | 0.216 ± 0.007bB |

Phenoloxidase activity in whiteleg shrimp fed different experimental diets.

Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3 tanks per treatment). Within the same column (same sampling day), different lowercase letters indicate significant differences among dietary treatments (p < 0.05). Within the same row (same treatment), different uppercase letters indicate significant differences among sampling days (p < 0.05).

3.2.4 Lysozyme activity

Lysozyme activity did not differ significantly between the control and WCE-fed groups on days 7 and 14 of the feeding trial (Table 5). However, by day 21, all WCE-fed groups had significantly higher activity than the control group (p < 0.05). Among the WCE groups, the highest lysozyme activity was observed in the WCE-312.5 group, although this value did not differ significantly from those recorded in the WCE-31.25 or WCE-625 groups.

Table 5

| Experimental groups | Lysozyme activity (U) (units mg protein-1) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 0 | Day 7 | Day 14 | Day 21 | |

| Control | 0.76 ± 0.06aA | 0.75 ± 0.02aA | 0.83 ± 0.02aA | 0.82 ± 0.01aA |

| WCE-31.25 | 0.80 ± 0.04aA | 0.78 ± 0.03aA | 0.82 ± 0.03aA | 0.88 ± 0.02bB |

| WCE-312.5 | 0.77 ± 0.04aA | 0.76 ± 0.04aA | 0.81 ± 0.05aA | 0.93 ± 0.03bB |

| WCE-625 | 0.78 ± 0.05aA | 0.81 ± 0.05aA | 0.84 ± 0.03aA | 0.91 ± 0.02bB |

Lysozyme activity in P. vannamei fed different experimental diets.

Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3 tanks per treatment). Within the same column (same sampling day), different lowercase letters indicate significant differences among dietary treatments (p < 0.05). Within the same row (same treatment), different uppercase letters indicate significant differences among sampling days (p < 0.05).

3.2.5 Superoxide dismutase

The superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity in the groups fed WCE-supplemented diets was significantly higher than that of the control group at all sampling times (Table 6). In the control group, SOD activity remained relatively constant throughout the experimental period, with no significant temporal variation observed (p > 0.05). In contrast, all WCE-fed groups exhibited a marked increase in SOD activity from day 7 onward compared with both their initial values (day 0) and the control group at the corresponding time points (p < 0.05). No significant difference in the SOD activity level was noted among the WCE-fed groups on days 7 and 14. However, on day 21, the WCE-625 group showed the highest SOD activity level, which was not significantly different from that observed in the WCE-312.5 group.

Table 6

| Experimental groups | SOD (U mL-1) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 0 | Day 7 | Day 14 | Day 21 | |

| Control | 0.78 ± 0.02aA | 0.79 ± 0.02aA | 0.77 ± 0.03aA | 0.82 ± 0.04aA |

| WCE-31.25 | 0.80± 0.05aA | 1.24 ± 0.07bB | 1.25 ± 0.08bB | 1.29 ± 0.06bB |

| WCE-312.5 | 0.81 ± 0.04aA | 1.27 ± 0.01bB | 1.24 ± 0.07bB | 1.43 ± 0.05cC |

| WCE-625 | 0.79 ± 0.03aA | 1.29 ± 0.02bB | 1.30 ± 0.01bB | 1.46 ± 0.07cC |

Superoxide dismutase activity in shrimp fed different experimental diets.

Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3 tanks per treatment). Within the same column (same sampling day), different lowercase letters indicate significant differences among dietary treatments (p < 0.05). Within the same row (same treatment), different uppercase letters indicate significant differences among sampling days (p < 0.05).

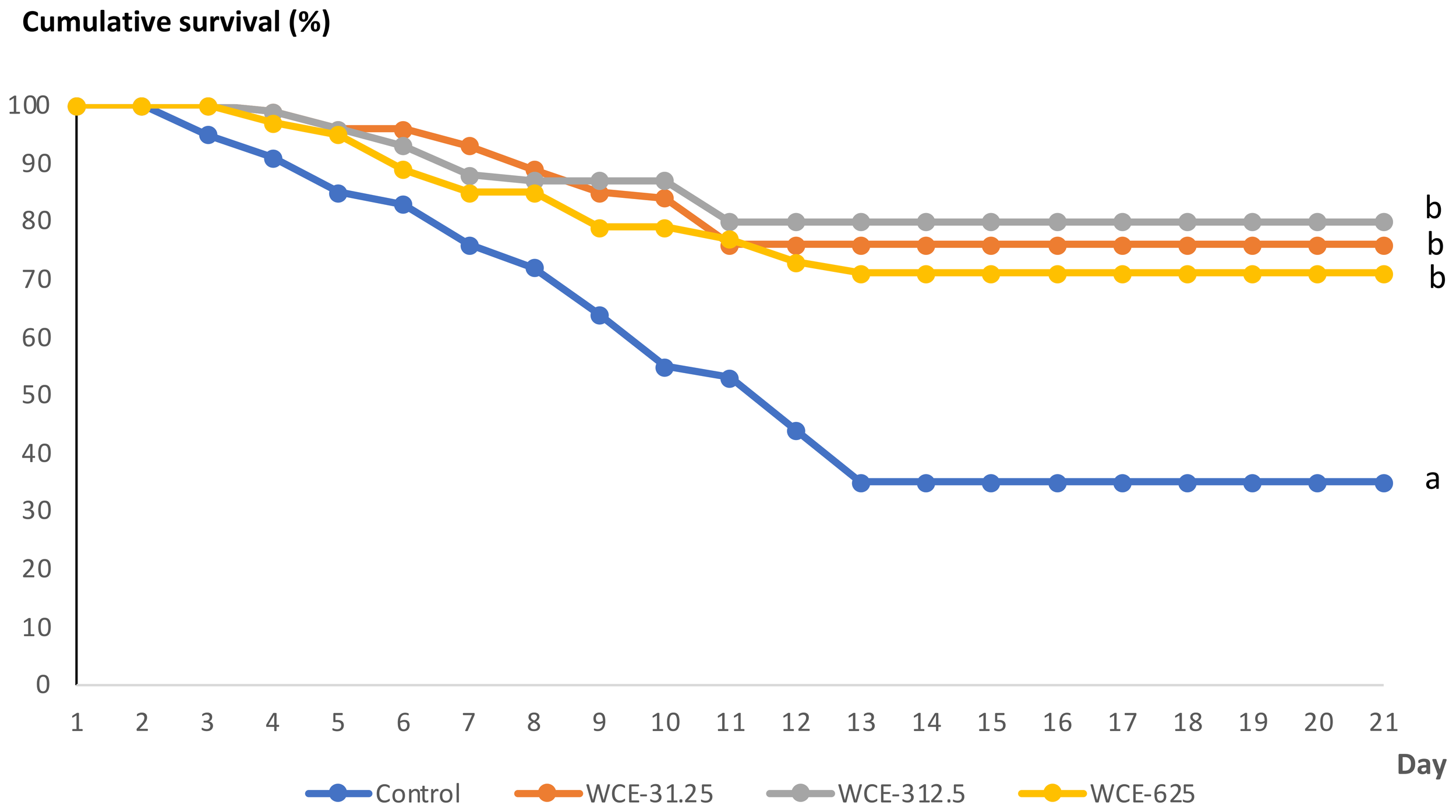

3.3 Challenge test

Following the V. parahaemolyticus challenge, shrimp fed the control diet showed a rapid decline in survival beginning from day 2 post-challenge, with the cumulative survival rate decreasing to approximately 35% by day 21 (Figure 1). In contrast, shrimp fed diets supplemented with WCE exhibited a delayed reduction in survival, with noticeable decreases occurring between days 3 and 4 post-challenge. Throughout the experimental period, all WCE-fed groups maintained significantly higher survival rates than the control group (p < 0.05). Survival curves stabilized after day 11 in the WCE-31.25 and WCE-312.5 groups, reaching final survival rates of approximately 76% and 80%, respectively. In the WCE-625 group, survival stabilized slightly later, after day 13, with a final survival rate of approximately 71%.

Figure 1

Kaplan–Meier Cumulative survival (%) of whiteleg shrimp fed a control diet or diets supplemented with W. chinensis extract (WCE) (31.25, 312.5, or 625 mg kg-1 feed) following V. parahaemolyticus challenge over 21 days. Survival distributions were compared using the log-rank (Mantel–Cox) test (p < 0.05 vs. control).

By day 21 post-challenge, no significant differences in survival were observed among the WCE-fed groups; however, all WCE treatments resulted in significantly higher survival compared with the control group, indicating a protective effect of dietary WCE supplementation against V. parahaemolyticus infection.

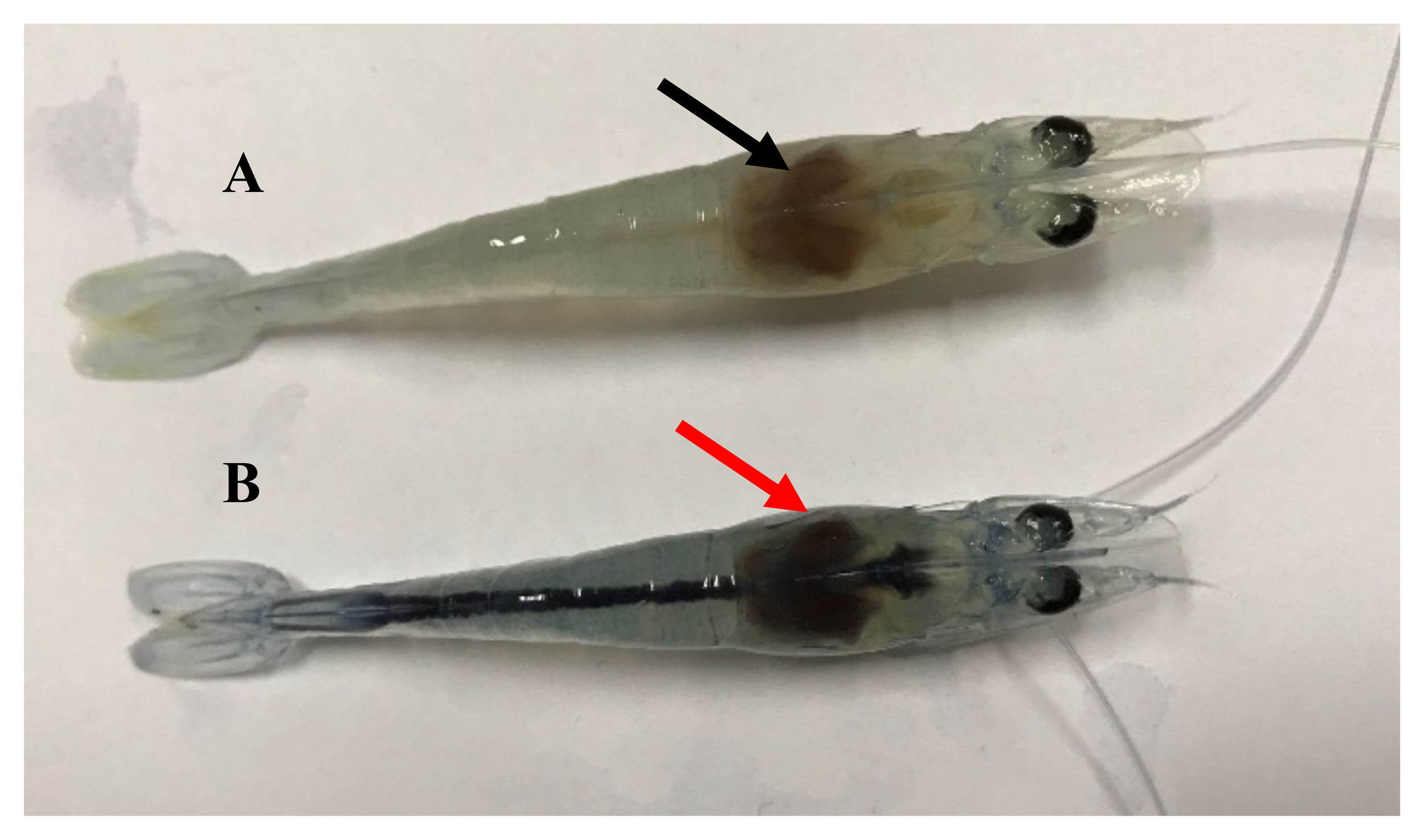

3.4 Clinical signs of infected shrimp

Moribund shrimp challenged with V. parahaemolyticus exhibited typical gross signs, including a pale hepatopancreas and an empty stomach and gut (Figure 2). Infected shrimp also showed sluggish swimming and reduced feeding activity prior to death. V. parahaemolyticus was consistently re-isolated from the hepatopancreas of moribund shrimp, whereas no typical clinical signs were observed in surviving shrimp at the end of the challenge period.

Figure 2

Representative clinical signs of whiteleg shrimp following V. parahaemolyticus challenge.(A) Normal shrimp from the control group; (B) challenged shrimp showing typical hepatopancreatic discoloration (arrow). Images are provided for illustrative purposes only and were not used as diagnostic criteria for infection.

4 Discussion

A robust innate immune system is essential for sustaining growth performance, survival, and disease resistance in farmed shrimp, particularly under intensive culture conditions where environmental and pathogenic pressures are high (Roy et al., 2020; Ghosh et al., 2021). As penaeid shrimp lack adaptive immunity, their defense against pathogens relies entirely on innate immune components, including hemocytes, humoral enzymes, and antioxidant systems (Vazquez et al., 2009; Kulkarni et al., 2021). Dietary immunostimulants, therefore, represent a practical strategy to enhance shrimp health and resilience in aquaculture.

The present study demonstrated that dietary supplementation with W. chinensis extract, delivered via a top-coating approach, positively modulated both growth performance and innate immune responses of P. vannamei. Top coating has been increasingly adopted in commercial feeding practices as an effective method to deliver functional additives without altering basal diet formulation, while minimizing nutrient loss during pelleting (Novriadi et al., 2023; Chellapandi, 2021). The observed improvements in the growth and health responses are likely attributable to the diverse phytochemical profile of WCE, including polyphenols, flavonoids, saponins, tannins, alkaloids, and fatty acids (Tran et al., 2022), which may act synergistically to enhance physiological performance and immune competence (Vala and Maitreya, 2019; Munaeni et al., 2019; Ha et al., 2020). The presence of these bioactive compounds may contribute to the multifaceted physiological responses observed in this study. The use of locally available plant resources was motivated by the potential to support regional economies, reduce reliance on imported additives, and improve cost-effectiveness in shrimp health management. Comparable benefits have been reported for other macroalgal and plant extracts, such as Ulva intestinalis, which enhanced growth performance and viral resistance in shrimp (Klongklaew et al., 2021).

Growth performance was significantly improved in shrimp fed WCE at 312.5 and 625 mg kg-1, as reflected by increased weight gain, specific growth rate, and reduced feed conversion ratio. These effects are consistent with previous studies reporting improved feed utilization following supplementation with herbal extracts and plant-derived compounds (Venketramalingam et al., 2007; Chandran et al., 2016; Effendi et al., 2022; Novriadi et al., 2023). Such growth enhancement may be associated with improved feed palatability, stimulation of digestive enzyme activity, and enhanced nutrient absorption rather than immune activation alone. Importantly, the non-linear response observed suggests that moderate inclusion levels (312.5 mg kg-1) may be optimal, as higher doses did not yield additional benefits.

Regarding immune parameters, WCE supplementation significantly increased total hemocyte count (THC), particularly at 312.5 mg kg-1. Hemocytes play a central role in crustacean immunity through phagocytosis, encapsulation, and production of immune effectors (Liu et al., 2020; Zhu, 2020; Effendi et al., 2022; Jian et al., 2022). The elevated THC observed in this study likely reflects both hemocyte proliferation and functional activation, a response that has been widely reported for phytogenic immunostimulants in shrimp, including Panax notoginseng (Chen et al., 2023), Astragalus membranaceus (Pu and Wu, 2022), Eleutherine bulbosa (Munaeni et al., 2020), Moringa oleifera leaf extract (Abidin et al., 2022), Phyllanthus amarus (Huang et al., 2020), Solanum ferox and Zingiber zerumbet (Rahardjo et al., 2022).

In parallel, key humoral immune enzymes, phenoloxidase (PO), lysozyme, and superoxide dismutase (SOD), were significantly enhanced in WCE-fed shrimp. Activation of the prophenoloxidase system is a hallmark of crustacean immune defense and contributes to melanization and pathogen clearance (Sritunyalucksana and Söderhäll, 2000; Kulkarni et al., 2021). The increased PO activity observed here may be mediated by polyphenols and flavonoids, which have been shown to stimulate proPO-related pathways. Elevated lysozyme activity further supports enhanced antibacterial capacity, as lysozyme plays a critical role in degrading bacterial cell walls and limiting pathogen proliferation (Magnadóttir, 2006; Uribe et al., 2011). This aligns with prior studies showing increased lysozyme activity from plant extracts (Anirudhan et al., 2023; Chen et al., 2023; Hoa et al., 2023).

Similarly, SOD activity was also markedly increased in WCE-fed shrimp, indicating strengthened antioxidant defense and improved capacity to mitigate oxidative stress during immune activation. Antioxidant enzymes, such as SOD are essential for maintaining cellular homeostasis during phagocytosis and respiratory burst responses (Campa-Córdova et al., 2002; Javahery et al., 2019; Jian et al., 2022; Eissa et al., 2023). Together, these findings suggest that WCE enhances both cellular and humoral components of innate immunity.

Phagocytic activity reached exceptionally high levels following bacterial exposure. This likely reflects an acute immune response triggered by experimental bacterial challenge rather than baseline phagocytic capacity. Similar transient elevations in phagocytic indices have been reported in shrimp following immunostimulant-induced priming and pathogen exposure, indicating rapid mobilization and activation of hemocytes (Chiu et al., 2007; Liu et al., 2020; Jian et al., 2022; Hong et al., 2022).

Immune enhancement observed in this study was accompanied by improved disease resistance, as reflected by significantly higher survival rates in WCE-fed shrimp following Vibrio parahaemolyticus challenge, particularly at the intermediate dose of 312.5 mg kg-1. However, elevated immune enzyme activities and hemocyte counts do not necessarily equate to improved immune efficiency under all conditions and may also reflect a state of sustained immune activation. In addition, the absence of molecular or gene expression analyses limits mechanistic interpretation of the underlying pathways, which are currently inferred based on functional immune indicators and comparisons with previous studies. Despite these limitations, the observed survival benefits are consistent with reports on other plant-derived immunostimulants used in shrimp challenged with bacterial pathogens (Huang et al., 2020; Chen et al., 2023; Hoa et al., 2023; Nguyen et al., 2023), supporting the potential application of WCE as a functional feed additive in shrimp aquaculture.

5 Conclusion

Dietary supplementation with W. chinensis extract significantly improved growth performance, enhanced key innate immune responses, and increased resistance of P. vannamei to AHPND-causing V. parahaemolyticus. Among the tested inclusion levels, 312.5 mg kg-1 feed consistently produced the most pronounced benefits, indicating this dose as a suitable reference for practical application.

Overall, the results indicate that W. chinensis extract may serve as a promising natural feed additive to support disease management strategies and reduce reliance on antibiotics in shrimp aquaculture. Nevertheless, additional studies are required to identify the specific bioactive compounds involved, elucidate the underlying immunological mechanisms, and validate the efficacy of this approach under commercial farming conditions.

Although the present study focuses on shrimp health rather than direct human nutrition outcomes, enhancing disease resistance and reducing antibiotic use in shrimp farming can indirectly contribute to safer aquatic food production and environmental sustainability. In this context, the use of locally available plant-based feed additives supports responsible aquaculture practices and aligns with broader sustainability goals related to food security and ecosystem protection.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The animal study was approved by This study was conducted according to the formal ethical approval No. HUVN0024 of The Animal Ethics Committee of Hue University, Vietnam. The study was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

TN: Methodology, Writing – original draft, Resources, Investigation, Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis. KB: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation. NL: Supervision, Writing – original draft, Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration. NQ: Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Investigation. NX: Writing – original draft, Data curation, Methodology. NH: Writing – original draft, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Conceptualization. PN: Validation, Writing – review & editing, Data curation. NP: Methodology, Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Supervision, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Project administration, Writing – review & editing, Validation.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This work was partly supported by the National project in science and technology (Code: DTDL.Cn-56/22) and by Hue University under the Core Research Program, Grant No. NCTB.DHH.2025.08. Tran Nguyen Ngoc (Tran, N.N) was funded by the Master, PhD Scholarship Program of Vingroup Innovation Foundation (VINIF), VINIF.2022.TS082.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/faquc.2026.1740206/full#supplementary-material

References

1

Abidin Z. Huang H. T. Hu Y. F. Chang J. J. Huang C. Y. Wu Y. S. et al . (2022). Effect of dietary supplementation with Moringa oleifera leaf extract and Lactobacillus acidophilus on growth performance, intestinal microbiota, immune response, and disease resistance in whiteleg shrimp (Penaeus vannamei). Fish. SF. Immunol.127, 876–890. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2022.07.007

2

Ahn Y. S. Piamsomboond P. Tang K. F. J. Han J. E. Kim J. H. (2017). Complete genome sequence of AHPND-causing Vibrio campbellii LA16-V1 isolated from Penaeus vannamei cultured in a Latin American country. Gene Announ.5, e01011–e01017. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.01011-17

3

Amend D. F. (1981). Potency testing of fish vaccines. International symposium on fish biologics: Serodiagnostics and vaccines. Dev. Biol. Stand.49, 447–454. doi: 10.4236/jss.2023.116003

4

Angela C. Wang W. Lyu H. Zhou Y. Huang X. (2020). The effect of dietary supplementation of Astragalus membranaceus and Bupleurum chinense on the growth performance, immune-related enzyme activities and genes expression in white shrimp, Litopenaeus vannamei. Fish. SF. Immunol.107, 379–384. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2020.10.014

5

Anirudhan A. Iryani M. T. M. Andriani Y. Sorgeloos P. Tan M. P. Wong L. L. et al . (2023). The effects of Pandanus tectorius leaf extract on the resistance of White-leg shrimp Penaeus vannamei towards pathogenic Vibrio parahaemolyticus. Fish. SF. Immunol. Rep.4, 100101. doi: 10.1016/j.fsirep.2023.100101

6

Appiah E. K. Hashem S. Fatsi P. S. K. Tettey P. A. Saito H. Omura M. et al . (2022). Antibacterial activity of Mallotus japonicus (LF) Müller Argoviensis on growth of Aeromonas hydrophila, A. salmonicida, Edwardsiella tarda and Vibrio Anguillarum. J. Appl. Microbiol.132, 298–310. doi: 10.1111/jam.15198

7

Boonyawiwat V. Patanasatienkul T. Kasornchandra J. Poolkhet C. Yaemkasem S. Hammell L. et al . (2017). Impact of farm management on expression of early mortality syndrome/acute hepatopancreatic necrosis disease (EMS/AHPND) on penaeid shrimp farms in Thailand. J. Fish. Dis.40, 649–659. doi: 10.1111/jfd.12545

8

Campa-Córdova A. I. Hernández-Saavedra N. Y. Ascencio F. (2002). Superoxide dismutase as modulator of immune function in American white shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei). Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part C.: Toxicol. Pharmacol.133, 557–565. doi: 10.1016/S1532-0456(02)000XX-X

9

Chandran M. N. Moovendhan S. Suganya A. M. Tamilselvi A. Immanuel G. Palavesam A. (2016). Influence of polyherbal formulation (AquaImmu) as a potential growth promotor and immunomodulator in shrimp Penaeus monodon. Aquac. Rep.4, 143–149. doi: 10.1016/j.aqrep.2016.10.002

10

Chellapandi P. (2021). Development of top-dressing automation technology for sustainable shrimp aquaculture in India. Discov. Sustain.2, 26. doi: 10.1007/s43621-021-00036-9

11

Chen Y. T. Kuo C. L. Wu C. C. Liu C. H. Hsieh S. L. (2023). Effects of Panax notoginseng Water Extract on Immune Responses and Digestive Enzymes in White Shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei. Animals13, 1131. doi: 10.3390/ani13071131

12

Chiu C. H. Guu. Y. K. Liu. C. H. Pan T. M. Cheng W. (2007). Immune responses and gene expression in white shrimp, Penaeus vannamei, induced by Lactobacillus plantarum. Fish. SF. Immunol.23, 364–377. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2006.11.010

13

De Schryver P. Defoirdt T. Sorgeloos P. (2014). Early mortality syndrome outbreaks: a microbial management issue in shrimp farming. Public Libr. Sci. Pathog.10, 1003919. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003919

14

Dong X. Bi D. Wang H. Zou P. Xie G. Wan X. et al . (2017). PirABvp-bearing Vibrio parahaemolyticus and Vibrio campbellii pathogens isolated from the same AHPND-affected pond possess highly similar pathogenic plasmids. Front. Microbiol.8, 1859–1867. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01859

15

Effendi I. Yoswaty D. Syawal H. Austin B. Lyndon A. R. Kurniawan R. et al . (2022). The use of medicinal herbs in aquaculture industry: a review. Curr. Asp. Pharm. Res. Dev.7, 7–20. doi: 10.9734/bpi/caprd/v7/2190C

16

Eissa E. S. H. Ahmed R. A. Abd Elghany N. A. Elfeky A. Saadony S. Ahmed N. H. et al . (2023). Potential Symbiotic Effects of β-1, 3 Glucan, and Fructooligosaccharides on the Growth Performance, Immune Response, Redox Status, and Resistance of Pacific White Shrimp, Penaeus vannamei to Fusarium solani Infection. Fishes8, 105. doi: 10.3390/fishes8020105

17

FAO (2024). The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2024 – Blue Transformation in action (Rome: FAO). doi: 10.4060/cd0683en

18

Ghosh A. K. Panda S. K. Luyten W. (2021). Anti-vibrio and immune- enhancing activity of medicinal plants in shrimp: A comprehensive review. Fish. SF. Immunol.117, 192–210. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2021.08.006

19

Ha P. T. T. Tran N. T. B. Tram N. T. N. Kha V. H. (2020). Total phenolic, total flavonoid contents and antioxidant potential of Common Bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) in Vietnam. AIMS. Agric. Food5 (4), 635–648. doi: 10.3934/agrfood.2020.4.635

20

Han J. E. Mohney L. Tang K. F. J. Pantoja C. R. Lightner D. V. (2015). Plasmid mediated tetracycline resistance of Vibrio parahaemolyticus associated with acute hepatopancreatic necrosis disease (AHPND). Aquacult. Rep.2, 17–21. doi: 10.1016/j.aqrep.2015.04.003

21

Han J. E. Tang K. F. J. Piamsomboom P. Aranguren L. F. (2017). Characterization and pathogenicity of acute hepatopancreatic necrosis disease natural mutants, pirABvp (-) V. parahaemolyticus, and pirABvp (+) V. campbellii strains. Aquaculture470, 84–90. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2016.12.022

22

Hang T. T. T. Duc C. T. Vy L. T. T. Trang N. C. (2018). Study on the anti-bacterial activities of extracts from sakae naa (Combretum quadrangulare) on diseased aquatic animals-bacteria under in vitro conditions. Can. Tho. Univ. J. Sci.13, 106–112. doi: 10.22144/ctu.jsi.2018.048

23

Hoa T. T. T. Fagnon M. S. Thy D. T. M. Chabrillat T. Trung N. B. Kerros S. (2023). Growth Performance and Disease Resistance against Vibrio parahaemolyticus of Whiteleg Shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) Fed Essential Oil Blend (Phyto AquaBiotic). Animals13, 3320. doi: 10.3390/ani13213320

24

Hong N. T. X. Linh N. T. H. Baruah K. Thuy D. T. B. Phuoc N. N. (2022). The combined use of Pediococcus pentosaceus and fructooligosaccharide improves growth performance, immune response, and resistance of whiteleg shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei Against Vibrio parahaemolyticus. Front. Microbiol.13. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.826151

25

Huang H. T. Lee P. T. Liao Z. H. Chen H. Y. Nan F. H. (2020). Effects of Phyllanthus amarus extract on nonspecific immune responses, growth, and resistance to Vibrio alginolyticus in white shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei. Fish. SF. Immunol.107, 1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2020.09.016

26

Javahery S. Noori A. Hoseinifar S. H. (2019). Growth performance, immune response, and digestive enzyme activity in Pacific white shrimp, Penaeus vannamei Boone 1931, fed dietary microbial ly- sozyme. Fish. SF. Immunol.92, 528–535. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2019.06.049

27

Jian J. T. Liu L. K. Liu H. P. (2022). Autophagy and white spot syndrome virus infection in crustaceans. Fish. SF. Immunol. Rep.3, 100047. doi: 10.1016/j.fsirep.2021.100047

28

Khan M. A. R. Islam M. A. Biswas K. Al-Amin M. Y. Ahammed M. S. Manik M. I. N. et al . (2023). Compounds from the petroleum ether extract of Wedelia chinensis with cytotoxic, anticholinesterase, antioxidant, and antimicrobial activities. Molecules28, 793. doi: 10.3390/molecules28020793

29

Kirubakaran C. J. W. Alexander C. P. Michael R. D. (2010). Enhancement of non-specific immune responses and disease resistance on oral administration of Nyctanthes arbortristis seed extract in Oreochromis mossambicus (Peters). Aquac. Res.41, 1630–1639. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2109.2010.02516

30

Klongklaew N. Praiboon J. Tamtin M. Srisapoome P. (2021). Chemical composition of a hot water crude extract (HWCE) from Ulva intestinalis and its potential effects on growth performance, immune responses, and resistance to white spot syndrome virus and yellowhead virus in Pacific white shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei). Fish. SF. Immunol.112, 8–22. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2021.02.004

31

Knipe H. Temperton B. Lange A. Bass D. Tyler C. R. (2021). Probiotics and competitive exclusion of pathogens in shrimp aquaculture. Rev. Aquac.13, 324–352. doi: 10.1111/raq.12477

32

Kulkarni A. Krishnan S. Anand D. Kokkattunivarthil Uthaman S. Otta S. K. Karunasagar I. et al . (2021). Immune responses and immunoprotection in crustaceans with special reference to shrimp. Rev. Aquac.13, 431–459. doi: 10.1111/raq.12482

33

Kumar R. Ng T. H. Wang H. C. (2020). Acute hepatopancreatic necrosis disease in penaeid shrimp. Rev. Aquac.12, 1867–1880. doi: 10.1111/raq.12414

34

Kumar S. Verma A. K. Singh S. P. Awasthi A. (2023). Immunostimulants for shrimp aquaculture: paving pathway towards shrimp sustainability. Environ. Sci. pollut. Res.30, 25325–25343. doi: 10.1007/s11356-021-18433-y

35

Lai H. C. Ng T. H. Ando M. Lee C. T. Chen I. T. Chuang J. C. et al . (2015). Pathogenesis of acute hepatopancreatic necrosis disease (AHPND) in shrimp. Fish. Shellfish. Immunol.47, 1006–1014. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2015.11.008

36

Lee J. M. Azizah R. N. Kim K. S. (2020). Comparative evaluation of three agar media-based methods for presumptive identification of seafood-originated Vibrio parahaemolyticus strains. Food Ctrl.116, 107308. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2020.107308

37

Lee C. T. Chen I. T. Yang Y. T. Ko T. P. Huang Y. T. Huang J. Y. et al . (2015). The opportunistic marine pathogen Vibrio parahaemolyticus becomes virulent by acquiring a plasmid that expresses a deadly toxin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.112, 10798–10803. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1503129112

38

Li X. Wang Y. F. Shi Q. W. Sauriol F. (2012). A new 30-noroleanane saponin from wedelia chinensis. Helv. Chim. Acta95, 1395–1400. doi: 10.1002/hlca.201100457

39

Li M. Wei D. Huang S. Huang L. Xu F. Yu Q. et al . (2022). Medicinal herbs and phytochemicals to combat pathogens in aquaculture. Aquac. Int.3), 1239–1259. doi: 10.1007/s10499-022-00841-7

40

Liu L. Xiao J. Xia X. Pan Y. Yan S. Wang Y. (2015). Draft genome sequence of Vibrio owensii strain SH-14, which causes shrimp acute hepatopancreatic necrosis disease. Genome Announc.3, e01395–e01315. doi: 10.1128/genomea.01395-15

41

Liu L. Xiao J. Zhang M. Zhu W. Xia X. Dai W. et al . (2018). A Vibrio owensii strain as the causative agent of AHPND in cultured shrimp, Litopenaeus vannamei. J. Invert. Pathol.153, 156–164. doi: 10.1016/j.jip.2018.02.005

42

Liu S. Zheng S. C. Li Y. L. Li J. Liu H. P. (2020). Hemocyte-mediated phagocytosis in crustaceans. Front. Immunol.11. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00268

43

Lulijwa R. Rupia E. J. Alfaro A. C. (2020). Antibiotic use in aqua- culture, policies and regulation, health and environmental risks: A review of the top 15 major producers. Rev. Aquac.12, 640–663. doi: 10.1111/raq.12344

44

Magnadóttir B. (2006). Innate immunity of fish (overview). Fish. SF. Immunol.20, 137–151. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2004.09.006

45

Manjamalai A. Jiflin G. J. Grace V. M. B. (2012). Study on the effect of essential oil of Wedelia chinensis (Osbeck) against microbes and inflammation. Asian J. Pharm. Clin. Res.5, 155–163. Available online at: https://innovareacademics.in/journal/ajpcr/Vol5Issue2/918.pdf (Accessed August 14, 2025).

46

Miles A. Misra S. Irwin J. (1938). The estimation of the bactericidal power of the blood. Epidemiol. Infect.38, 732–749. doi: 10.1017/S002217240001158X

47

Munaeni W. Yuhana M. Setiawati M. Wahyudi A. T. (2019). Phytochemical analysis and antibacterial activities of Eleutherine bulbosa (Mill.) Urb. extract against Vibrio parahaemolyticus. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed.9, 397–404. doi: 10.4103/2221-1691.267669

48

Munaeni W. Yuhana M. Setiawati M. Wahyudi A. T. (2020). Effect in white shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei of Eleutherine bulbosa (Mill.) Urb. Powder on immune genes expression and resistance against Vibrio parahaemolyticus infection. Fish. SF. Immunol.102, 218–227. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2020.03.066

49

Ngoc T. N. Lai N. L. Linh N. T. H. Phuoc N. N. Linh N. Q. (2023). vibrio parahaemolyticus isolated from infected white leg shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) of acute hepatopancreatic necrosis disease. Hue University Science Magazine. Agric. Rural Dev.132, 5–19. doi: 10.26459/hueunijard.v132i3B.7020

50

Nguyen T. T. Luu T. T. Nguyen T. T. Pham V. D. Nguyen T. N. Truong Q. P. et al . (2023). A comprehensive study in efficacy of Vietnamese herbal extracts on whiteleg shrimp (Penaeus vannamei) against Vibrio parahaemolyticus causing acute hepatopancreatic necrosis disease (AHPND). Isr. J. Aquac. - Bamidgeh.75, 1–22. doi: 10.46989/001c.81912

51

Novriadi R. Hasan O. D. S. Nguyen K. Davies S. Panjaitan Z. G. Sektiana S. P. et al . (2023). Functional Effects of Hydrolyzable Tannins on the Growth, Health Status, and Hepatopancreas Histology of Pacific White Shrimp Penaeus vannamei Reared under Commercial Pond Conditions. Aquac. Res.2023, 6644113. doi: 10.1155/2023/6644113

52

OIE (2019). Acute hepaatopancreatic necrosis disease (Paris: World Organisation for Animal Health).

53

OIE (2020). Immediate notifications, Acute hepatopancreatic necrosis disease. Available online at: https://www.oie.int/wahis_2/public/wahid.php/Reviewreport/Review?page_refer=MapFullEventReport&reportid=36209&newlang=en (Accessed August 10, 2025).

54

Phuoc N. N. Linh N. T. H. Crestani C. Zadoks R. N. (2021). Effect of strain and enviromental conditions on the virulence of Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B Streptococcus; GBS) in red tilapia (Oreochromis sp.). Aquaculture534, 736256. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2020.736256

55

Pu Y. Wu S. (2022). The growth performance, body composition and nonspecific immunity of white shrimps (Litopenaeus vannamei) affected by dietary Astragalus membranaceus polysaccharide. Int. J. Biol. Macromolecules.209, 162–165. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2022.04.010

56

Rahardjo S. Vauza M. A. T. Rukmono D. Wiradana P. A. (2022). Supplementation of hairy eggplant (Solanum ferox) and bitter ginger (Zingiber zerumbet) extracts as phytobiotic agents on whiteleg shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei). J. Adv. Vet. Anim. Res.9, 78. doi: 10.5455/%2Fjavar.2022.i571

57

Restrepo L. Bayot B. Arciniegas S. Bajaña L. Betancourt I. Panchana F. et al . (2018). PirVP genes causing AHPND identified in a new Vibrio species (Vibrio punensis) within the commensal Orientalis clade. Sci. Rep.8, 13080–13093. Available online at: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-018-30903-x (Accessed August 14, 2025).

58

Reverter M. Bontemps N. Lecchini D. Banaigs B. Sasal P. (2014). Use of plant extracts in fish aquaculture as an alternative to chemotherapy: current status and future perspectives. Aquaculture433, 50–61. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2014.05.048

59

Roy S. Bossier P. Norouzitallab P. Vanrompay D. (2020). Trained immunity and perspectives for shrimp aquaculture. Rev. Aquac.12, 2351–2370. doi: 10.1111/raq.12438

60

Seyfried E. E. Newton R. J. Rubert K. F. (2010). Occurrence of tetracycline resistance genes in aquaculture facilities with varying use of oxytetracycline. Microb. Ecol.59, 799–807. doi: 10.1007/2Fs00248-009-9624-7

61

Shekhar M. S. Katneni V. K. Jangam A. K. Krishnan K. Kaikkolante N. Vijayan K. K. (2021). The Genomics of the farmed shrimp: Current status and application. Rev. Fish. Sci. Aquac.29, 654–665. doi: 10.1080/23308249.2020.1858271

62

Sritunyalucksana K. Söderhäll K. (2000). The proPO and clotting system in crustaceans. Aquac. Int.191, 53–70. Available online at: http://www.elsevier.nl/locate/aqua-online (Accessed August 14, 2025).

63

Talukdar T. Talukdar D. (2013). Response of antioxidative enzymes to arsenic-induced phytotoxicity in leaves of a medicinal daisy, Wedelia chinensis Merrill. J. Natural Sci. Biol. Med.4, 383. doi: 10.4103/2F0976-9668.116989

64

Tang K. F. J. Bondad-Reantaso M. G. Arthur J. R. MacKinnon B. Hao B. Alday-Sanz V. et al . (2020). “ Shrimp acute hepatopancreatic necrosis disease strategy manual,” in FAO fisheries and aquaculture circular no. 1190 ( FAO, Rome). doi: 10.4060/cb2119en

65

Tran N. N. Phuoc N. N. Linh N. Q. (2022). Preliminary phytochemical screening and antimicrobial effect toward Vibrio parahaemolyticus isolated from white leg shrimp (Penaeus vannamei) of the herbal extract of Wedelia chinensis. Eur. Chem. Bull.11, 1–10. doi: 10.53555/ecb/2022.11.12.204

66

Uribe C. Folch H. Enriquez R. Moran G. (2011). Innate and adaptive immunity in teleost fish: A review. Vet. Med. (Praha)56, 486–503. doi: 10.17221/3294-VETMED

67

Vala M. Maitreya B. (2019). Qualitative analysis, total phenol content (TPC) and total tannin content (TTC) by using different solvant for flower of Butea monosperma (Lam.) Taub. collected from Saurashtra region. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem.8, 2902–2906.

68

Vazquez L. Alpuche J. Maldonado G. Agundis C. Pereyra-Morales A. Zenteno E. (2009). Immunity mechanisms in crustaceans. Innate. Immun.15, 179–188. doi: 10.1177/1753425909102876

69

Venketramalingam K. Christopher J. G. Citarasu T. (2007). Zingiber officinalis anherbal appetizer in the tiger shrimp Penaeus monodon (Fabricius) larviculture. Aquac. Nutr.13, 439–443. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2095.2007.00495.x

70

Won S. Hamidoghli A. Choi W. Bae J. Jang W. J. Lee S. et al . (2020). Evaluation of potential probiotics Bacillus subtilis WB60, Pediococcus pentosaceus, and Lactococcus lactis on growth performance, immune response, gut histology and immune-related genes in whiteleg shrimp, Litopenaeus vannamei. Microorganisms8, 281. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms8020281

71

Zhu F. (2020). A review on the application of herbal medicines in the disease control of aquatic animals. Aquaculture526, 735422. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2095.2007.00495.x

Summary

Keywords

acute hepatopancreatic necrosis disease, crustacean immunity, disease management, functional feed additive, plant-derived compounds/extracts, sustainable aquaculture

Citation

Ngoc TN, Baruah K, Linh NQ, Quynh Anh ND, Xuan Hong NT, Huy NX, Norouzitallab P and Phuoc NN (2026) Dietary Wedelia chinensis extract enhances growth performance and strengthens innate immunity of whiteleg shrimp (Penaeus vannamei) against Vibrio parahaemolyticus. Front. Aquac. 5:1740206. doi: 10.3389/faquc.2026.1740206

Received

05 November 2025

Revised

13 January 2026

Accepted

19 January 2026

Published

09 February 2026

Volume

5 - 2026

Edited by

Cristian Andres Valenzuela, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Valparaíso, Chile

Reviewed by

Paulina Schmitt, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Valparaíso, Chile

Muhammad Ar Rozzaaq Nugraha, National Taiwan Ocean University, Taiwan

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Ngoc, Baruah, Linh, Quynh Anh, Xuan Hong, Huy, Norouzitallab and Phuoc.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Nguyen Ngoc Phuoc, nguyenngocphuoc@hueuni.edu.vn

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.