Abstract

Nanotechnology has become a trending area in science and has made great advances with the development of functional, engineered nanoparticles. Various metal nanoparticles have been widely exploited for a wide range of medical applications. Among them, gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) are widely reported to guide an impressive resurgence and are highly remarkable. AuNPs, with their multiple, unique functional properties, and easy of synthesis, have attracted extensive attention. Their intrinsic features (optics, electronics, and physicochemical characteristics) can be altered by changing the characterization of the nanoparticles, such as shape, size and aspect ratio. They can be applied to a wide range of medical applications, including drug and gene delivery, photothermal therapy (PTT), photodynamic therapy (PDT) and radiation therapy (RT), diagnosis, X-ray imaging, computed tomography (CT) and other biological activities. However, to the best of our knowledge, there is no comprehensive review that summarized the applications of AuNPs in the medical field. Therefore, in this article we systematically review the methods of synthesis, the modification and characterization techniques of AuNPs, medical applications, and some biological activities of AuNPs, to provide a reference for future studies.

Introduction

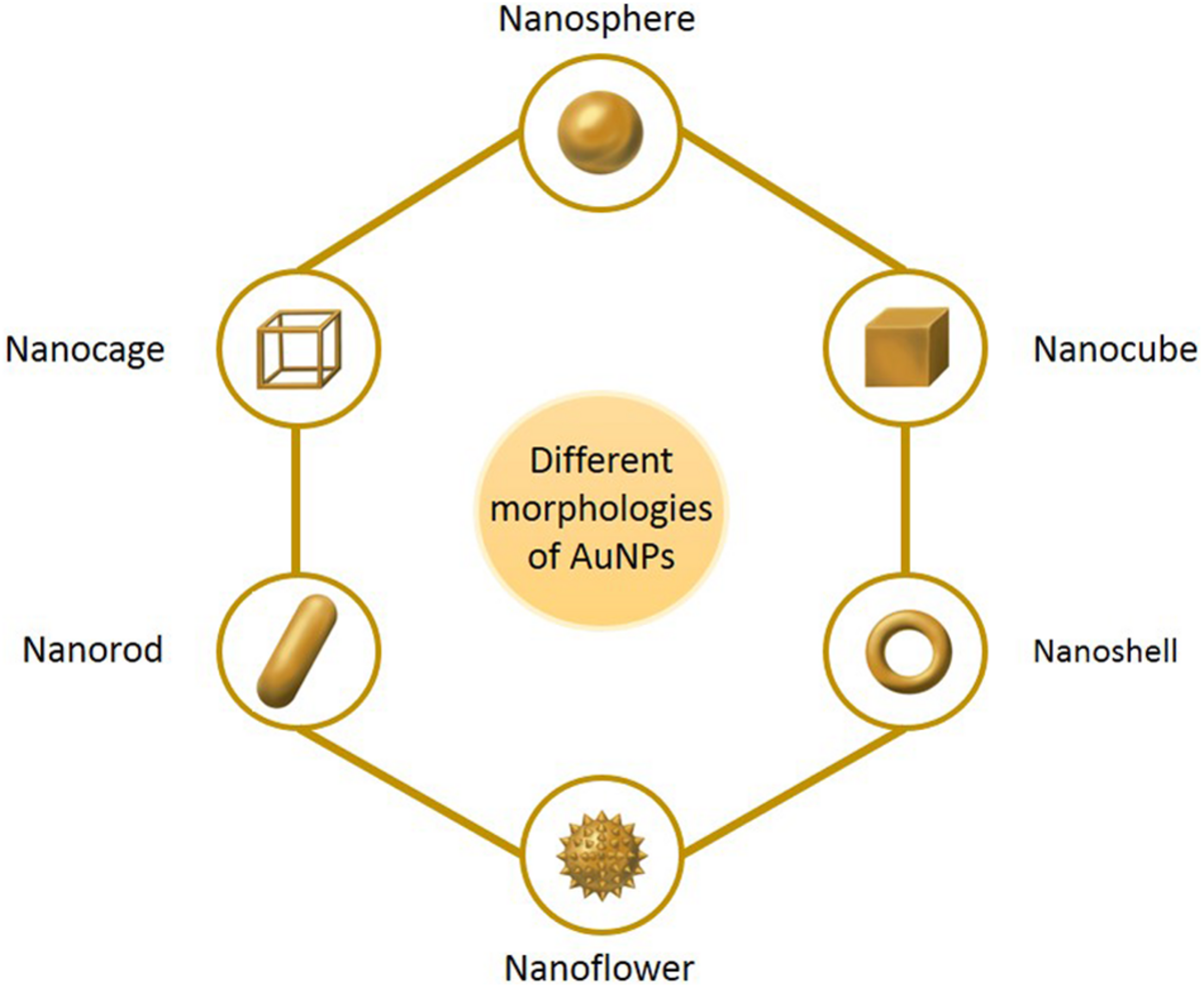

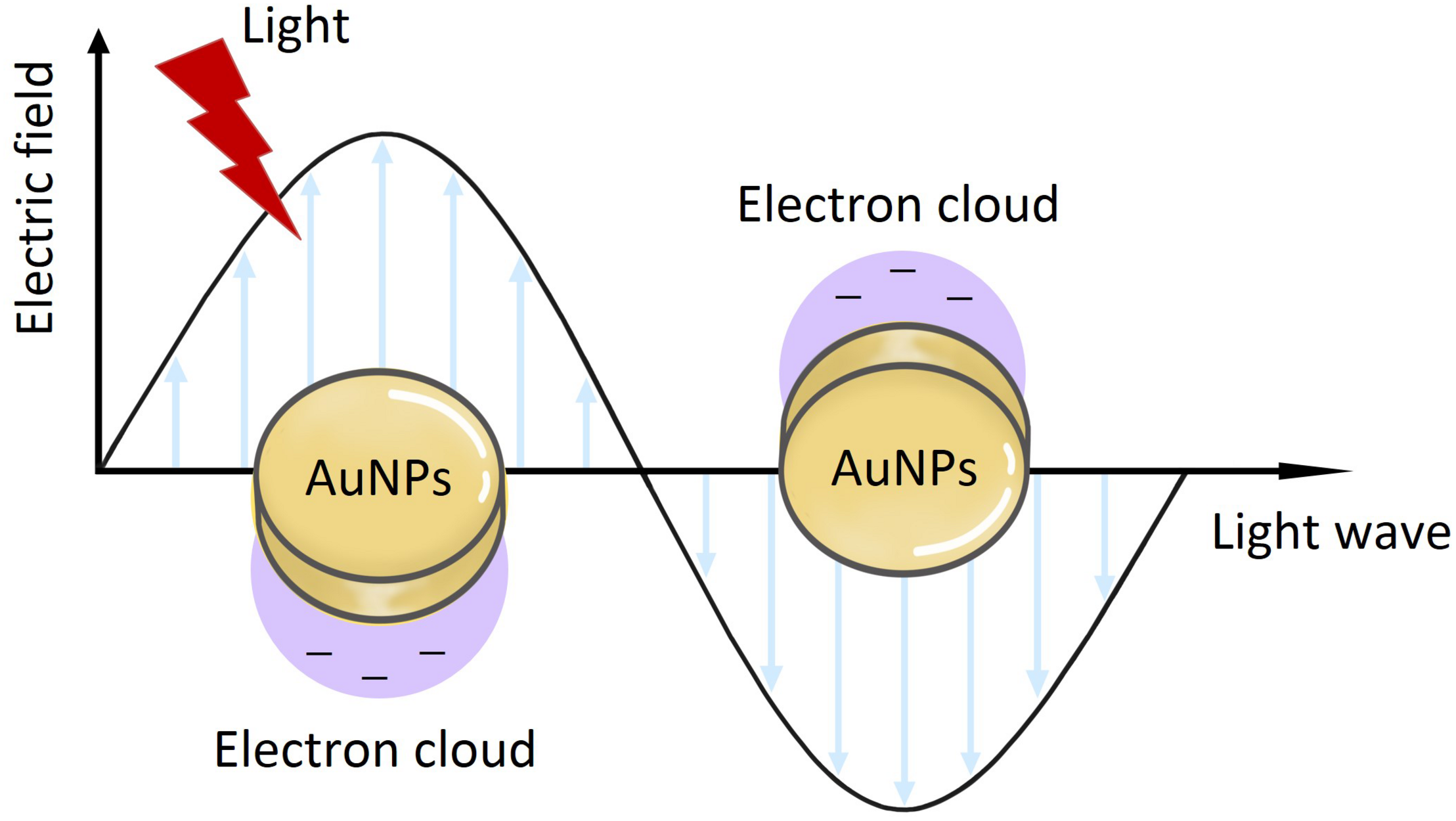

Nanomaterials are a novel type of material which has emerged in recent years. The term refers to a material in which at least one dimension, of three-dimensional space, is at the nanometer scale (0.1–100 nm), or is composed of the basic unit, which is approximately equivalent to the size of 10–100 atoms, is closely arranged together (Khan et al., 2017; Tayo, 2017). Nanoparticles are an example of nanomaterials, which now have the longest development time and are the most mature technology. Nanoparticles and nanotechnology are widely used and play an important role in a range of fields, such as medicine, biology, physics, chemistry and sensing, owing to their unique properties (Ramalingam, 2019). In comparison with other metal nanoparticles, noble metal (Cu, Hg, Ag, Pt, and Au) nanoparticles have increasingly attracted the attention of researchers (Ramalingam et al., 2014). Among these, gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) are known to be the most stable, and have now been prepared with various shapes and structures, including nanospheres, nanorods, nanocubes, nanobranches, nanobipyramids, nanoflowers, nanoshells, nanowires, and nanocages, by various synthetic techniques (Figure 1) (O’Neal et al., 2004; Chen et al., 2008; Li et al., 2015; Xiao et al., 2019). Moreover, they possess tunable and unique optical properties. Therefore, AuNPs have attracted extensive scientific and technological attention in recent decades. The optical properties of AuNPs are dependent on surface plasmon resonance (SPR), which is the fluctuation and interaction of electrons between negative and positive charges at the surface (Ramalingam, 2019). SPR can also be described in terms of surface plasmon polariton (SPP), which originates from propagating waves along a planar gold surface (Gurav et al., 2019). Due to their unique optical and electrical properties, and economic importance, AuNPs have abundant applications in various interdisciplinary branches of science, including medicine, material science, biology, chemistry and physics (Khan et al., 2019).

FIGURE 1

The main morphologies of AuNPs.

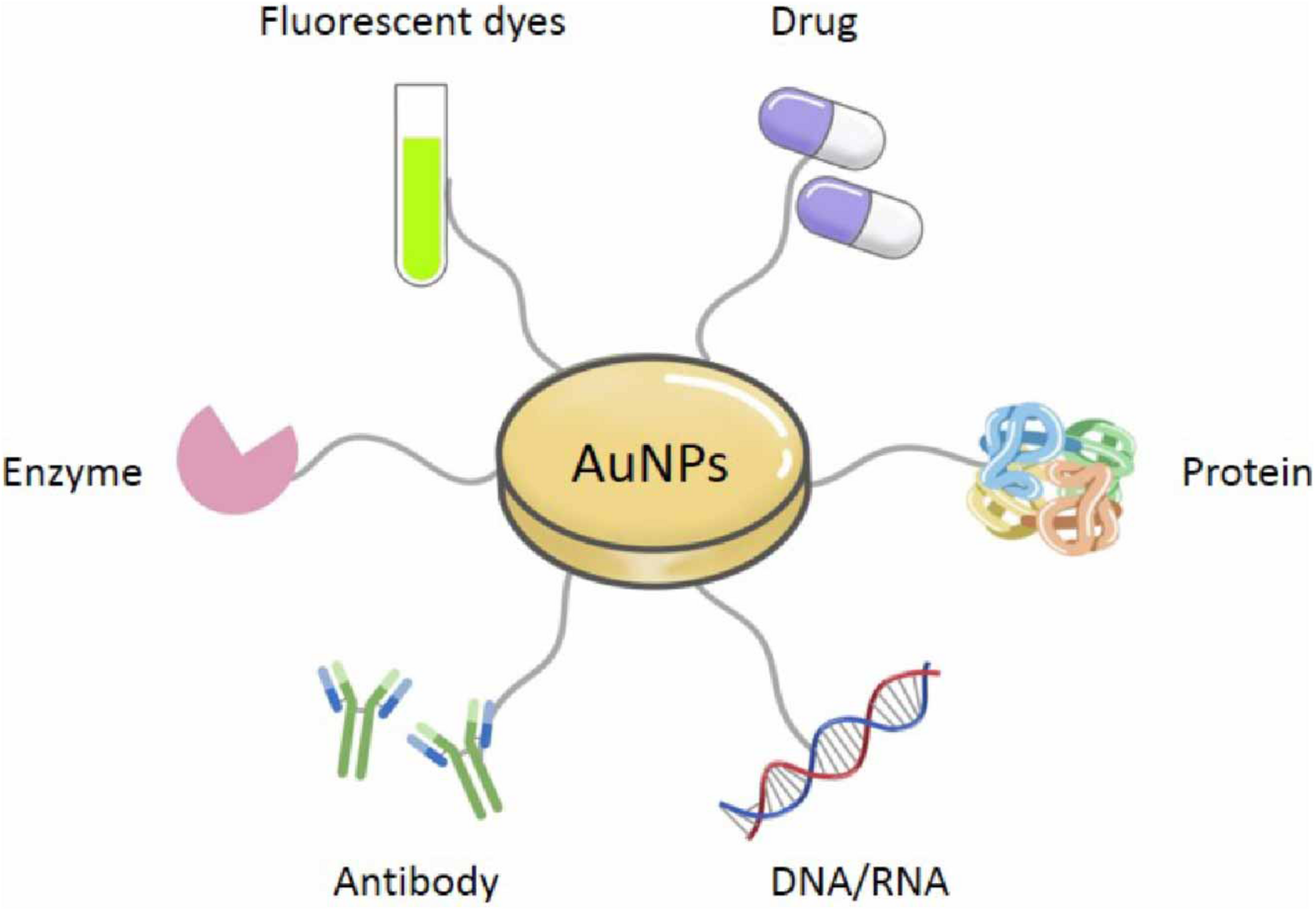

Especially, AuNPs are widely employed across the medical field owing to their excellent biocompatibility, which respectively results from their high chemical and physical stability, easy to functionalize with biologically active organic molecules or atoms (Pissuwan et al., 2019). AuNPs can directly conjugate and interact with diverse molecules containing proteins, drugs, antibodies, enzymes, nucleic acids (DNA or RNA), and fluorescent dyes on their surface, for diverse medical applications and biological activities (Figure 2) (Slocik et al., 2005; Ramalingam, 2019). Although AuNPs are so widespread and increasingly used in the medical field, there is no comprehensive review of their applications in medicine. Therefore, in this review, we have summarized the approaches that are available for synthesizing common AuNPs, as well as the techniques that are used to characterize them, based on their unique and diverse properties. We have also paid particular attention to the discussion of established medical applications of AuNPs.

FIGURE 2

Various connecting molecules of AuNPs.

Synthesis and Modification of Multifunctional AuNPs

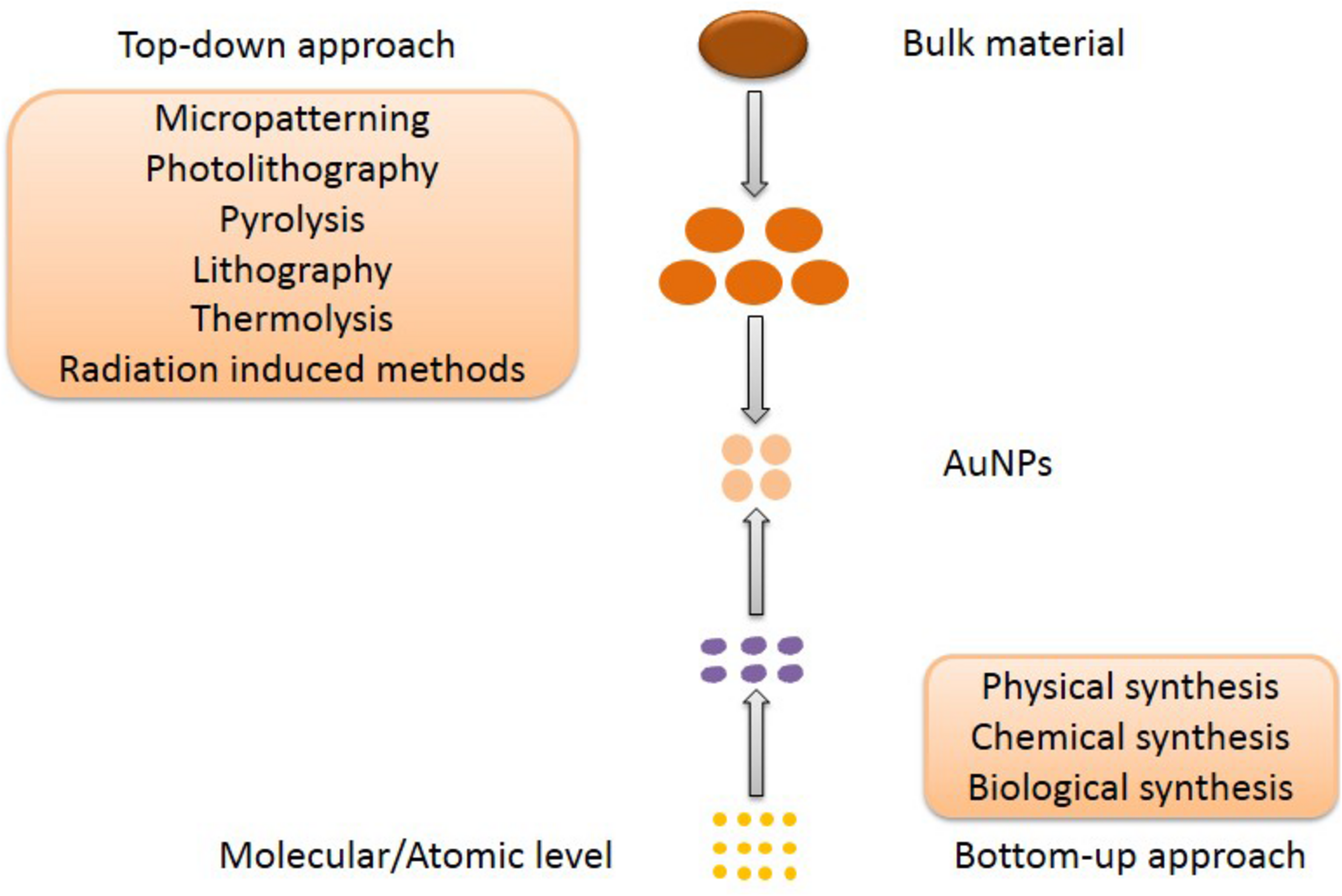

Almost all the medical applications and biological activities of AuNPs was characterized based on the unique SPR, since the SPR can enhance the surface activity of AuNPs. Due to the excitation of SPR, the absorption spectrum connected with AuNPs shows a resonance band in the visible region, whose amplitude, spectral location and width can be modified by the diverse particle size and shape in the medium. Also, the SPR is strongly dependent on both size and shape (Ramalingam, 2019). Therefore, the preparation of size-controlled and shape-controlled AuNPs is essential for the medical applications and biological activities. The first report on AuNPs was published in 1857 by Faraday with light scattering potential of AuNPs confirmed by the change of red color and colloidal nature of nanomaterials (Faraday, 1857). Although AuNPs have a long history, the synthesis of small and stable structure of AuNPs is difficult, key challenge in nanotechnology. To our knowledge, there are two distinct approaches of synthesizing AuNPs, which are top–down and bottom–up respectively (Figure 3). The materials of AuNPs prepared by different methods are various, which are bulk material, small gold seeds or gold target, HAuCl4⋅4H2O and various biological extracts respectively. Furthermore, AuNPs can bind various active molecules, and have broad prospects in the application of diverse fields. Thus, the modification of AuNPs will also be introduced.

FIGURE 3

The top–down and bottom–up approaches for AuNPs synthesis.

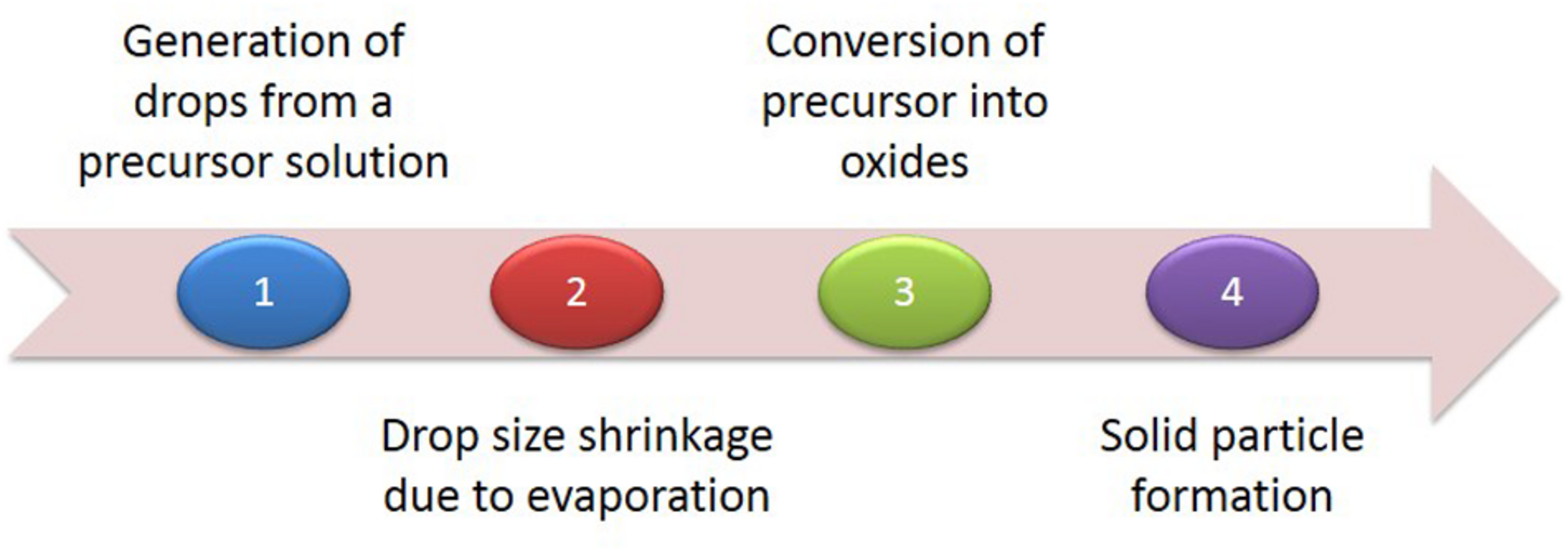

Top–Down Approach

Generally, the top–down approach is a subtractive process, starting with the slicing of bulk materials and ending with self-assembled nanoscale objects (Khanna et al., 2019). Micropatterning and photolithography are the most common approaches (Chen et al., 2009; Walters and Parkin, 2009). Yun et al. (2006) demonstrated micropatterning of a single layer of nanoparticles and micelles through conventional and soft lithographical methods. Although the approach is fast, it has the limitation of synthesizing nanoparticles of uniform size. Thus, Chen et al. (2009) developed a novel patterning technique for AuNPs by removing salt-loaded micelles from substrate areas with a polymer stamp. They called the technique μ-contact (microcontact) deprinting, providing a fast and cheap way to produce nanoparticles on a wide range of substrates. In addition, there are several physical methods, such as pyrolysis, lithography, thermolysis and radiation induced methods in this category. Pyrolysis is another important technique frequently used, generally for the production of noble metal nanoparticles. As shown in Figure 4, pyrolysis has four major steps, from generation of drops from a precursor solution to solid particle formation (Figure 4) (Li et al., 2004). Pyrolysis has several disadvantages, such as the formation of porous films, low purity in some cases and limited products (Garza et al., 2010). In conclusion, the top–down approach has major limitations in the control of surface and structure of the AuNPs, which has a significant effect on their physical and chemical properties (Amblard et al., 2002; Sant et al., 2012). Size distribution is uncontrolled and enormous energy is required to maintain conditions of high-pressure and high-temperature during these synthetic procedures. Thus, it is very uneconomical and difficult to meet product requirements.

FIGURE 4

The four major steps of pyrolysis.

Bottom–Up Approach

As a popular nanomaterial, AuNPs are expected to present with applications in many areas. However, their yield is currently too low in existing methods of synthesis. Developing more convenient and adjustable methods to improve their preparation efficiency, in order to achieve production on a technical scale, has become the focus of research. The bottom–up approach has been an emerging strategy in recent years. There are three types of bottom–up synthesis approaches: (1) physical approaches, such as laser ablation, sputter deposition, ion implantation, γ-irradiation, optical lithography, microwave (MW) irradiation, ultrasound (US) irradiation, and ultraviolet (UV) irradiation (Table 1); (2) the chemical reduction of metal ions in solutions by introducing chemical agents and stabilizing agents, such as sodium hydroxide (NaOH), sodium borohydride (NaBH4), cetyl-trimethylammonium bromide (CTAB), lithium aluminum hydride (LiAlH4), sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), ethylene glycol (EG), and sodium citrate (Figures 5, 6); (3) biological approaches, using intracellular or extracellular extracts of prokaryotic cells (bacteria and actinomycetes) or eukaryotic cells (algae, fungi, and yeast), and extracts from various plants (leaves, stem, flower, fruits, peel, bark, and root) (Table 2). These syntheses will be discussed in detail in the following parts.

TABLE 1

| Method | Morphology | Size (nm) | Author | References |

| γ-irradiation | Nanosphere | 3–6 | Le et al. | Le et al., 2019 |

| Ion implantation | Crystalline | 1.5–5 | Morita et al. | Morita et al., 2017 |

| Laser ablation | Nanosphere | 10–15 | Vinod et al. | Vinod et al., 2017 |

| Nanosphere | 7 | Hampp et al. | Riedel et al., 2020 | |

| Ultrasound irradiation | Polyhedral | 15–40 | Shaheen et al. | Bhosale et al., 2017 |

| Microwave irradiation | Nanosphere | 10–50 | Luo et al. | Luo et al., 2018 |

Physical synthesis of AuNPs with different morphology and size.

FIGURE 5

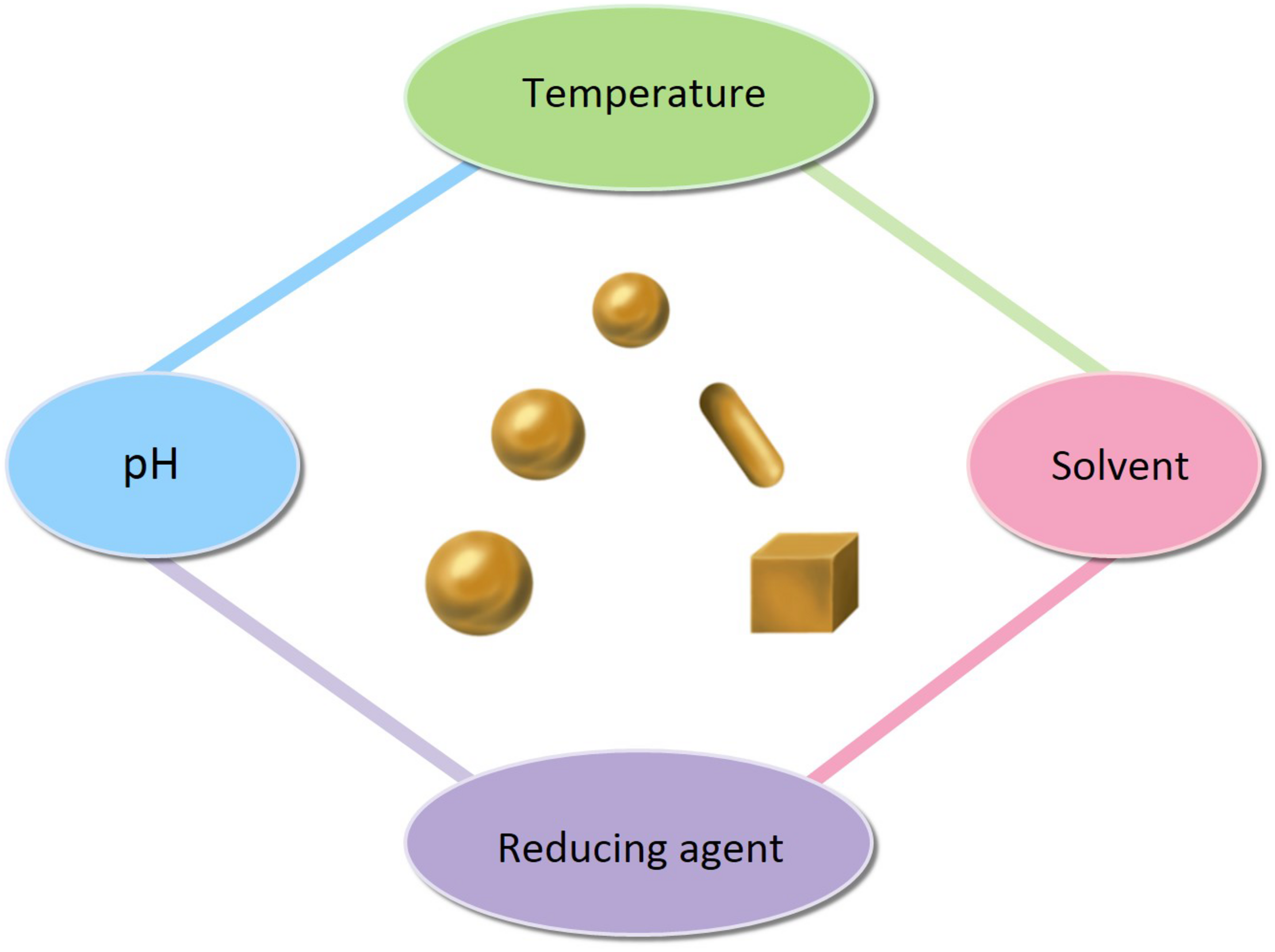

The chemical synthesis of AuNPs using different reaction conditions.

FIGURE 6

The factors affecting the size and shape of AuNPs.

TABLE 2

| Organism | Morphology | Size (nm) | Author | References |

| Garcinia mangostana | Nanosphere | 20–40 | Nishanthi et al. | Nishanthi et al., 2019 |

| Couroupita guianensis | Nanocube | 15–37 | Singh et al. | Singh et al., 2016a |

| Acanthopanax sessiliflorus | Nanoflower | 30–60 | Ahn et al. | Ahn et al., 2017 |

| Sporosarcina koreensis | Nanosphere | 92 | Singh et al. | Singh et al., 2016b |

| Sargassum swartzii | Nanosphere | 35 | Prema et al. | Prema et al., 2015 |

Organisms mediated synthesis of AuNPs with different morphology and size.

Physical Approach

Most of the physical methods used to prepare nanoparticles involve controlling experimental parameters in the presence of a reducing agent, to modulate the structures and properties of AuNPs without contamination (Table 1). Laser ablation and ion implantation are the most common and important physical methods of synthesis. Laser ablation provides an approach which effectively alters the surface area, geometric shape, properties, fragmentation, and assembly of AuNPs in aqueous solution, a biocompatible medium (Correard et al., 2014; González-Rubio et al., 2016). For example, Vinod et al. (2017) synthesized pure AuNPs through laser ablation of a gold target in water, and these nanoparticles are inherently non-toxic. And these particles are photothermally active when excited with 532 nm laser irradiation. However, the yield of this method is low, and the method is inconvenient. Therefore, the development of convenient, high-efficiency methods is necessary, in order to scale up production. Recently, Riedel et al. (2020) synthesized spherical, silica-coated AuNPs, with an average diameter of 9 nm and a coating thickness of 2 nm, by improved pulsed laser ablation in liquid (PLAL), and this method offers great progress to the large-scale production of nanoparticles. Another promising method for synthesis of AuNPs is ion implantation, which has been extensively used to prepare AuNPs with precise physical, chemical, and biological properties. Nie et al. (2018) reported the synthesis of embedded AuNPs in Nd:YAG single crystals, using ion implantation, and subsequent thermal annealing. Both linear and non-linear absorption of the Nd:YAG crystals have been significantly enhanced.

Chemical Approach

The easiest and most commonly used approach to synthesis is the chemical reduction of metal ions in solutions (Figure 5). A typical synthesis of AuNPs is dependent on the reduction of Au(III) (from hydrogen tetrachloroaurate hydrate, HAuCl4) to Au(0) atoms, formed as clusters and accumulated into large, polycrystalline particles via aggregation in the presence of reducing or stabilizing agent. Citrate-stabilized AuNPs were initially synthesized by Turkevich et al. (1951), which was also the first chemical synthesis of AuNPs. This synthesis was based on the single-phase aqueous reduction of HAuCl4 by sodium citrate. This synthesis was further refined by Frens (1973) by varying the ratio of sodium citrate and gold salt in order to control the size of AuNPs, from 5 to 150 nm. However, the diameter (<30 nm) of AuNPs was too poor. Leff et al. (1995) synthesized surfactant-mediated AuNPs over a range of diameters from 1.5 to 20 nm, by varying the gold-to-thiol ratio (Leff et al., 1995). In 2007, adopting the classical reaction system, Ji et al. (2007) also synthesized AuNPs by changing the pH of solution, which can affect the composition of gold solute complexes, in order to alter the particle size. Then, Jimenez et al. (2010) synthesized small AuNPs with sodium citrate and heavy water (D2O). This was a faster reduction method, and by increasingly replacing water with deuterium oxide, smaller diameters were obtained. Today, the aqueous method remains the most commonly used. However, the shape of AuNPs is irregular, and the size and size distribution obtained are quite poor. Thus, Natan and Brown (1998) reported the seeded growth of AuNPs (up to 100 nm in diameter) by using hydroxylamine as a mild reducing agent. And Brown et al. (1999) prepared AuNPs with highly uniform shape and size by introducing the boiling solution of sodium citrate. The mean diameters of the AuNPs produced were between 20 and 100 nm, and they exhibit improved monodispersity. A similar procedure, utilizing the reductant NH2OH at room temperature, produces two populations of particles. The larger population is even more spherical than citrate-reduced particles of similar size, while the smaller population is very distinctly rod shaped. This work was improved by Jana et al. (2001) and Rodriguez-Fernandez et al. (2006). They synthesized monodispersed AuNPs with narrow size distributions, using ascorbic acid (AA) and CTAB, which are used as a reducing agent and cationic surfactant respectively. Jana et al. (2001) prepared the AuNPs with diameters of 5–40 nm by varying the ratio of seed to gold salt, whereas Rodriguez-Fernandez et al. (2006) prepared the AuNPs with diameters from 12 to 180 nm by incorporating small gold clusters on the surface of seed particles (Jana et al., 2001; Rodriguez-Fernandez et al., 2006). Although CTAB-based method can control the morphology of AuNPs, the thiolated cationic surfactant molecules that bind to the gold surface are difficult to remove and restrict further functionalization. The reason is that the strongly bound capping layer provided by the CTAB is difficult to exchange with the thiolated cationic surfactant molecules (Leonov et al., 2008). Thus, Bastus et al. (2011) reported a kinetically controlled seeded growth method for the synthesis of monodispersed citrate-stabilized AuNPs, with a uniform quasi-spherical shape of up to ∼200 nm, via the reduction of HAuCl4 by sodium citrate. They also evaluated the effect of temperature and pH on their final shape. According to the mentioned above, it is known that the temperature, pH, the solvent, and the reducing/stabilizing agent of the reaction system play a crucial role in controlling the size and shape of AuNPs (Figure 6). This has also encouraged researchers to look for novel strategies to prepare AuNPs with controllable properties. Recent seed-mediated synthesis methods are considered very efficient, with respect to precise control of the size and shape of AuNPs.

Biological Approach

Although the synthesis of AuNPs by physical and chemical methods gives a high yield and is relatively cheap, there are a few disadvantages which have also been reported, such as the use of carcinogenic solvents, the contamination of precursors, and high toxicity (Ramalingam, 2019). To overcome these difficulties, researchers have investigated the biological production of AuNPs, and have explored the potential of micro-organisms, due to the quest for economically as well as environmentally benign methods (Table 2) (Jain N. et al., 2011; Ramalingam et al., 2019). Biological systems and agents are excellent examples of hierarchical organization of atoms or molecules and this has caused researchers to use a wide range of biological agents as potential cell factories for the production of nanomaterials (Gardea-Torresdey et al., 1999; Singaravelu et al., 2007; Kasthuri et al., 2008; Smitha et al., 2009). Using biological agents to reduce the metal ions requires benign conditions of external temperature and pressure, and little organic solvent (Khan et al., 2019). For example, Dubey et al. (2010) reported a rapid, green synthesis for AuNPs, using the lower amounts extract of Rosa rugosa leaf (Kumar et al., 2010). They also evaluated the effect of the quantity of leaf extract, the concentration of gold solution, the stability of AuNPs and different pH with zeta potentiometer. Although environmentally friendly and easy to regulate the shape and size of the nanoparticles, bacterial-mediated synthesis also has disadvantages, such as difficulty in handling and low yield (Azharuddin et al., 2019).

Modification

The size and morphology controlled AuNPs can be prepared based on different approaches above mentioned. AuNPs exhibit excellent physiochemical properties like unique SPR property, wide surface chemistry, high binding affinity, good biocompatibility, enhanced solubility, tunable functionalities for targeted delivery (Dreaden et al., 2012). Therefore, they have the ability to bind thiol and amine groups, which allows their modification for medical applications and biological activities (Shukla et al., 2005). On the one hand, AuNPs can directly attach ligands such as drug (Table 3), protein, DNA/RNA, enzyme, and so on (Figure 2). For instance, Podsiadlo et al. (2008) synthesized AuNPs bearing 6-Mercaptopurine (6-MP) and its riboside derivatives (6-Mercaptopurine-9-β-D-Ribofuranoside, 6-MPR). 6-MP and 6-MPR are loaded on the surfaces of AuNPs through sulfur-gold (Au–S) bonds known for their strength. They found substantial enhancement of the antiproliferative effect against K-562 leukemia cells compared to the free form of same drug. On the other hand, AuNPs are also used to conjugate with various drug with polymer functionalized for medical applications and biological activities. Recently, the design and preparation of polymer-functionalized AuNPs have attracted increasing interest. The AuNPs functionalized with polymer have more biocompatibility, stability, controlled release of drug, and enhanced therapeutic applications (Ramalingam, 2019). Some examples of polymer functionalized AuNPs for drug delivery are as shown in Table 3. For example, Venkatesan et al. (2013) developed AuNRs–doxorubicin conjugates (DOX@PSS-AuNRs) by an electrostatic interaction between the amine group (−NH2) of DOX and the negatively charged PSS-AuNRs surface. DOX@PSS-AuNRs conjugates exhibited improved drug loading efficiency, higher biological stability and higher therapeutic efficiency than free DOX. Therefore, the unique physical and chemical properties of AuNPs functionalized with/without polymer can enhance the efficiency of drug deliver and therapeutic efficiency, and increase the multifunctional application.

TABLE 3

| Polymer | Drug | Morphology | Size (nm) | References |

| – | 6-Mercaptopurine | Nanosphere | 4–5 | Podsiadlo et al., 2008 |

| – | Dodecylcysteine | Nanosphere | 3–6 | Azzam and Morsy, 2008 |

| – | Kahalalide F | Nanosphere | 20, 40 | Hosta et al., 2009 |

| – | Phthalocyanine | Nanosphere | 2–4 | Wieder et al., 2006 |

| – | Rose Bengal | Nanorod | – | Wang et al., 2014 |

| PEG | Doxorubicin | Nanosphere | 11 | Asadishad et al., 2010 |

| PSS | Doxorubicin | Nanorod | 5 | Venkatesan et al., 2013 |

| Chitosan | 5-fluorouracil | Nanosphere | 20 | Chandran and Sandhyarani, 2014 |

| Glycyrrhizin | Lamivudine | Nanosphere | 16 | Borker et al., 2016 |

| PCPP | Camptothecin | Nanosphere | 25–30 | Sivaraj et al., 2018 |

Functionalized AuNPs without/with polymer for drug delivery with different morphology and size.

Characterization of Multifunctional AuNPs

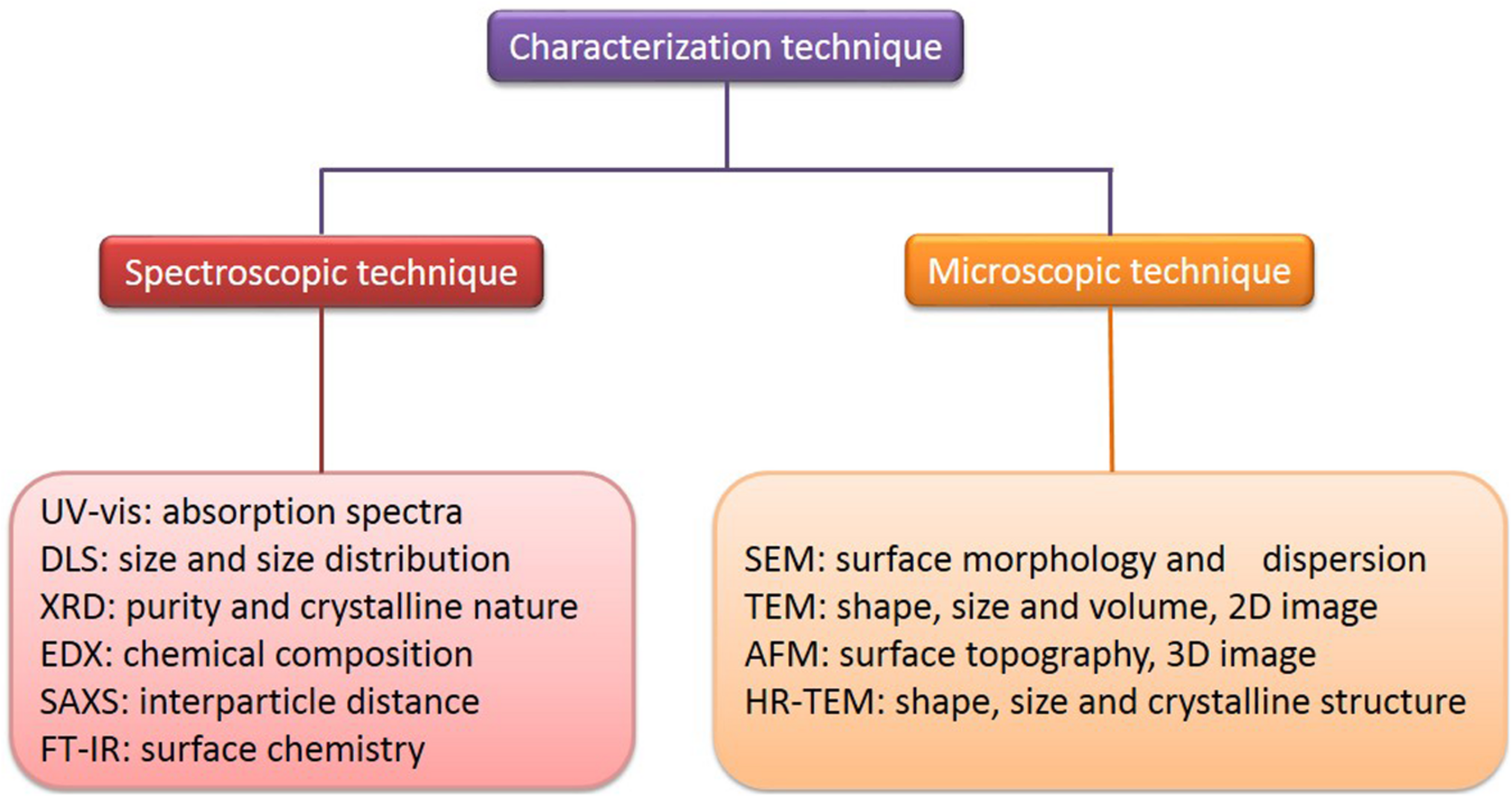

Various analytical techniques have been developed, in recent years, to characterize noble metal nanoparticles, according to their unique thermal, electrical, chemical, and optical properties, and to confirm their size (average particle diameter), shape, distribution, surface morphology, surface charge, and surface area (Roduner, 2006; Ray et al., 2015; Khanna et al., 2019). The characterization of AuNPs starts with a visual color change which can be observed with the naked eye, based on the principle of their unique and tunable SPR band (Ramalingam, 2019). The characterization of AuNPs has been shown schematically in Figure 7.

FIGURE 7

Characterization of AuNPs.

There are some indirect methods (spectroscopic technique) used to analyze the composition, structure, and crystal phase of AuNPs. Their striking optical properties are due to their SPR, which is monitored by UV-visible spectroscopy (UV-vis) (Sharma et al., 2016). The absorption spectra of AuNPs fall in the range of 500–550 nm (Poinern, 2014). It has been suggested a broadening of the SPR band width, which illustrates a redshift, can be used as an index of their state of aggregation, dispersity, size, and shape (Govindaraju et al., 2008; Shukla and Iravani, 2017). The size of AuNPs and their size distribution in situ, in the same range of hydrodynamic diameter, can be observed and measured by dynamic light scattering (DLS) (Wu et al., 2018). The purity and crystalline nature of AuNPs can be confirmed through X-ray diffraction (XRD), which gives a rough idea of the particle size, determined by the Debye-Scherer equation (Ullah et al., 2017). The chemical composition of AuNPs can be confirmed by energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) (Shah et al., 2015). Small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) analysis can be used to provide a measure of the interparticle distance of AuNPs, of application to tumor imaging and tissue engineering (Allec et al., 2015). Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR) can investigate the surface chemistry to determine the functional atoms or groups bound to the surface of AuNPs (Dahoumane et al., 2016). The morphology of AuNPs can now be better characterized, due to recent developments in advanced microscopic techniques. These include scanning electron microscopy (SEM), transmission electron microscopy (TEM), high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HR-TEM), and atomic force microscopy (AFM), which are commonly employed to determine and characterize their size, shape, and surface morphology (Azharuddin et al., 2019; Khanna et al., 2019). SEM provides nanoscale information about particles and determines their surface morphology and dispersion, while TEM is used to provide information about the number of material layers and broad evidence of uptake and localization, composition, polymer tethering, and physical properties (Marquis et al., 2009; Khanna et al., 2019). Also, TEM is commonly used as a quantitative method to measure size, volume, and shape, and it produces mainly two-dimensional (2D) image of three-dimensional (3D) nanoparticles (Quester et al., 2013). HR-TEM is used to determine the exact shape, size, and crystalline structure (Khanna et al., 2019). AFM, which is similar to the scanning probe microscopy, provides information about surface topography of AuNPs (Lu et al., 2004). AFM has the advantage of obtaining 3D images in a liquid environment (Lu et al., 2004; Khan et al., 2017). Some examples of the characterization of AuNPs, its morphology and size are as shown in Table 4.

TABLE 4

| Author | Morphology | Size (nm) | Characterization | References |

| Falagan-Lotsch et al. | Nanorod | 16–50 | TEM, DLS, UV-vis | Falagan-Lotsch et al., 2016 |

| Dam et al. | Nanostar | 40 | TEM, DLS | Dam et al., 2014 |

| Balfourier et al. | Nanosphere | 4–22 | TEM, STEM, HR-TEM, EDX | Balfourier et al., 2019 |

| Ni et al. | Nanosphere | 5, 13, 45 | DLS, UV-vis | Ni et al., 2019 |

| Lin et al. | Nanosphere | ∼10 | TEM, SEM, DLS | Lin et al., 2019 |

| Dash et al. | Nanosphere | 15–23 | HR-TEM, UV-vis, EDX, XRD, AFM, FT-IR | Dash et al., 2014 |

| Lee et al. | Nanosphere Nanooctahedra Nanocube | 75 | TEM, SEM, UV-vis | Lee et al., 2019 |

Characterization of AuNPs and its morphology and size.

Medical Applications of Multifunctional AuNPs

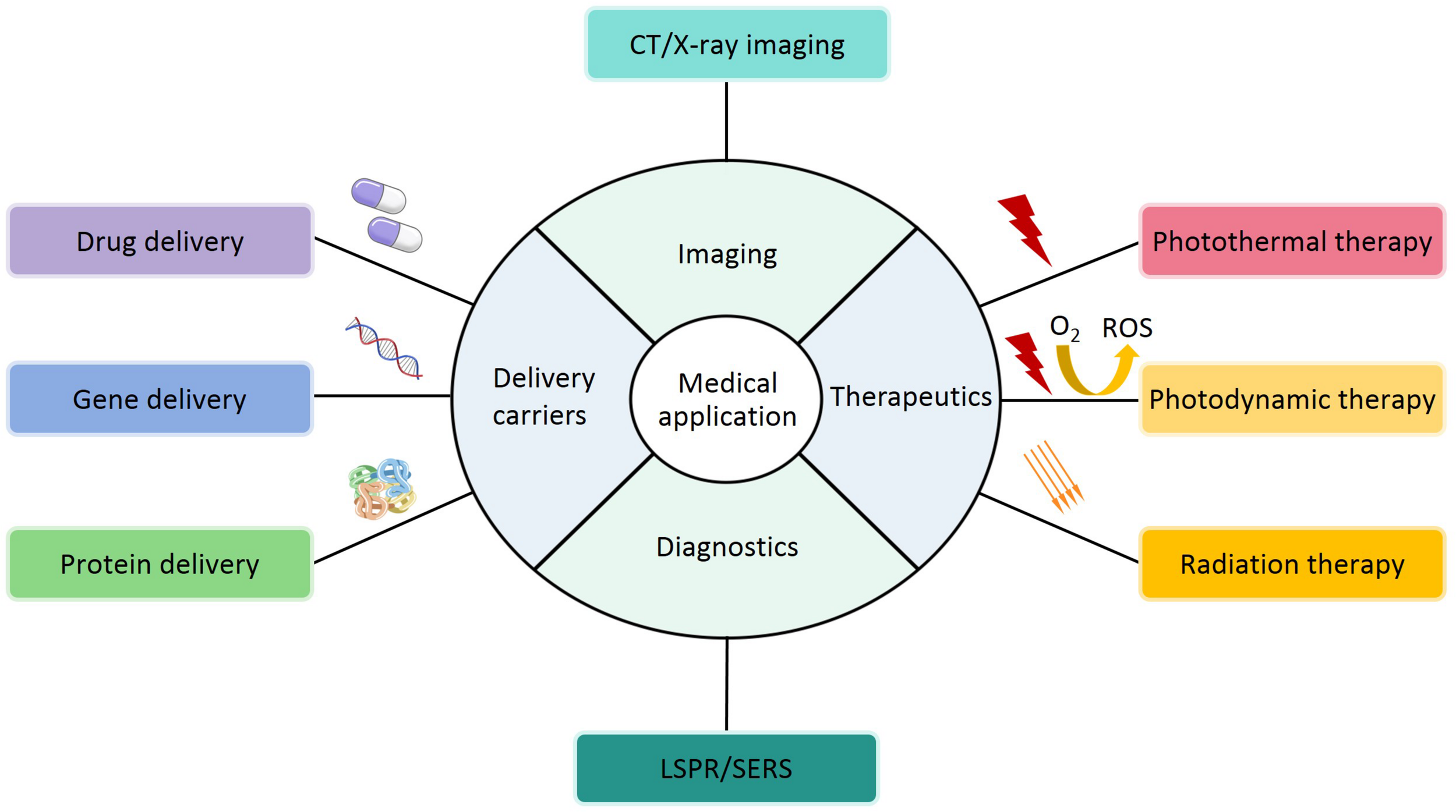

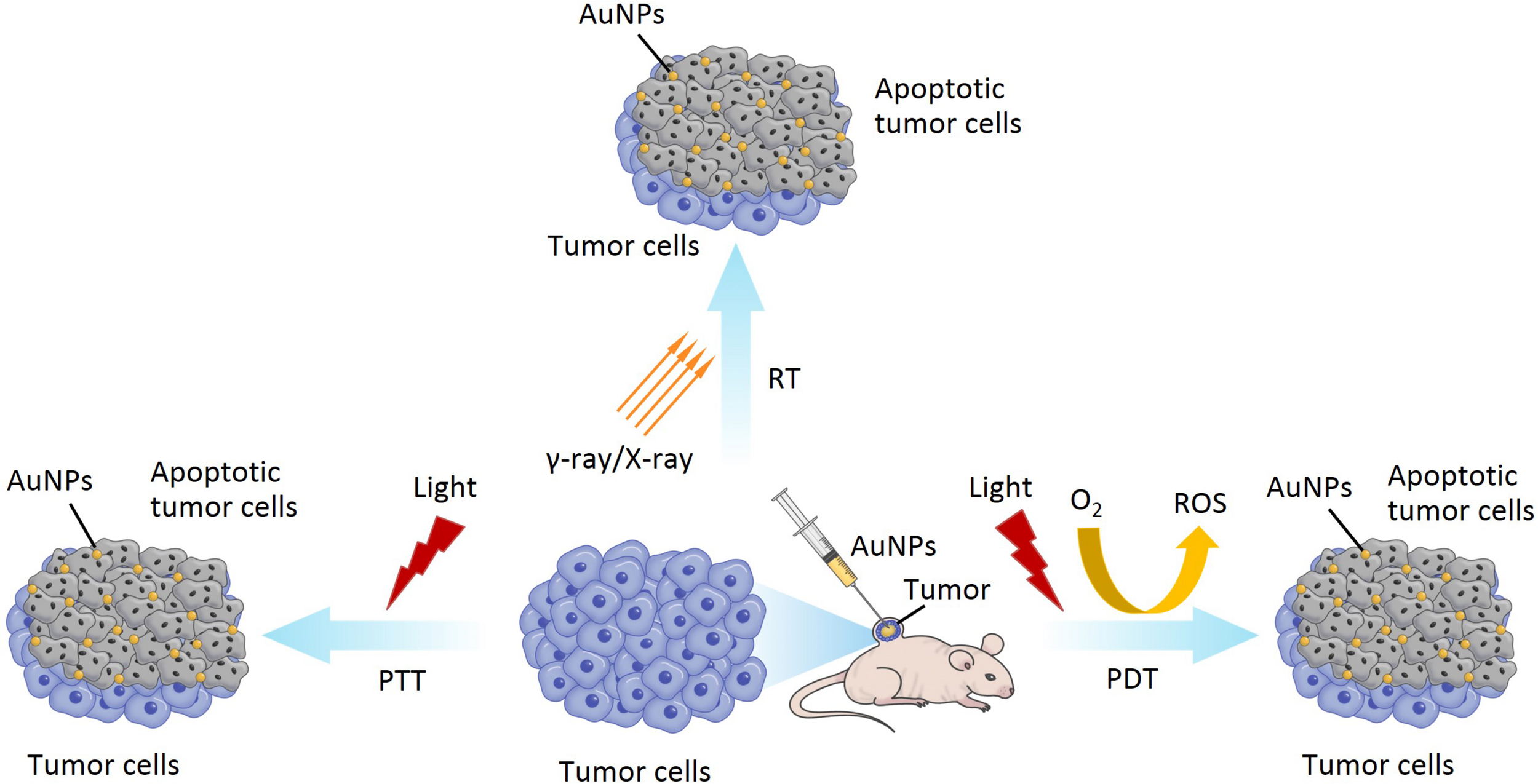

In the above parts, the synthesis, modification and characterization of AuNPs based on optical and physicochemical properties have been introduced. Although nearly all studies are in the experimental stages, it is clear that AuNPs have potential applications in different fields. Based on their characteristics, applications have been explored, particularly in medical field, including deliver carriers (drug, gene and protein deliver), therapeutics (PTT, PDT and RT), diagnostics, imaging, and other biological activities (Figure 8 and Table 5). In the following sections, these applications will be discussed in detail.

FIGURE 8

A schematic representation of medical applications for AuNPs.

TABLE 5

| Author | Morphology | Size (nm) | Application/Activity | References |

| Tian et al. | Nanostar | 40 | PTT and CT | Tian et al., 2017 |

| Rossi et al. | Nanosphere | 5–10 | Drug delivery and bioactivity | Rossi et al., 2016 |

| Xu et al. | Nanocapsule | 50 | PTT, PDT and RT | Xu et al., 2019 |

| Borkowska et al. | Nanocore | 5.3 ± 0.7 | Anticancer activity | Borkowska et al., 2020 |

| Zheng et al. | Nanostar | 7–10 | PTT | Zheng et al., 2020 |

| Liu et al. | Nanocapsule | 30–40 | Imaging | Liu et al., 2018 |

| Venditti | Nanosphere | 5 | CT | Venditti, 2017 |

| Yang et al. | Nanocube | 50 | PDT | Yang et al., 2018 |

| Hu et al. | Nanosphere | 100 | PTT and RT | Hu et al., 2017 |

| Yu et al. | Nanosphere | 73.8 | CT imaging and shRNA delivery | Yu et al., 2019 |

| Zheng et al. | Nanosphere | 2.04 ± 0.18 | Drug delivery | Zheng et al., 2019 |

| Shahbazi et al. | Nanosphere | 19 | Gene delivery | Shahbazi et al., 2019 |

| Loynachan et al. | Nanocluster | 2 | Disease detection | Loynachan et al., 2019 |

| Philip et al. | Nanosphere | 37 | SERS | Philip et al., 2018 |

| Ramalingam et al. | Nanosphere | 20–37 | Anticancer and antimicrobial activity | Ramalingam et al., 2017 |

| Filip et al. | Nanosphere | 31 | Anti-inflammation activity | Filip et al., 2019 |

| Wang et al. | Nanobipyramid | – | Diagnosis | Wang et al., 2020 |

| Ahmad et al. | Nanosphere | 4–10 | Antimicrobial activity | Ahmad et al., 2013 |

| Tahir et al. | Nanosphere | 2–10 | Antioxidant activity | Tahir et al., 2015 |

| Terentyuk et al. | Nanosphere | 62 | Antifungal activity | Terentyuk et al., 2014 |

| El-Husseini et al. | Nanosphere | 15 | Diagnosis | El-Husseini et al., 2016 |

The application or activity of AuNPs with different morphology and size.

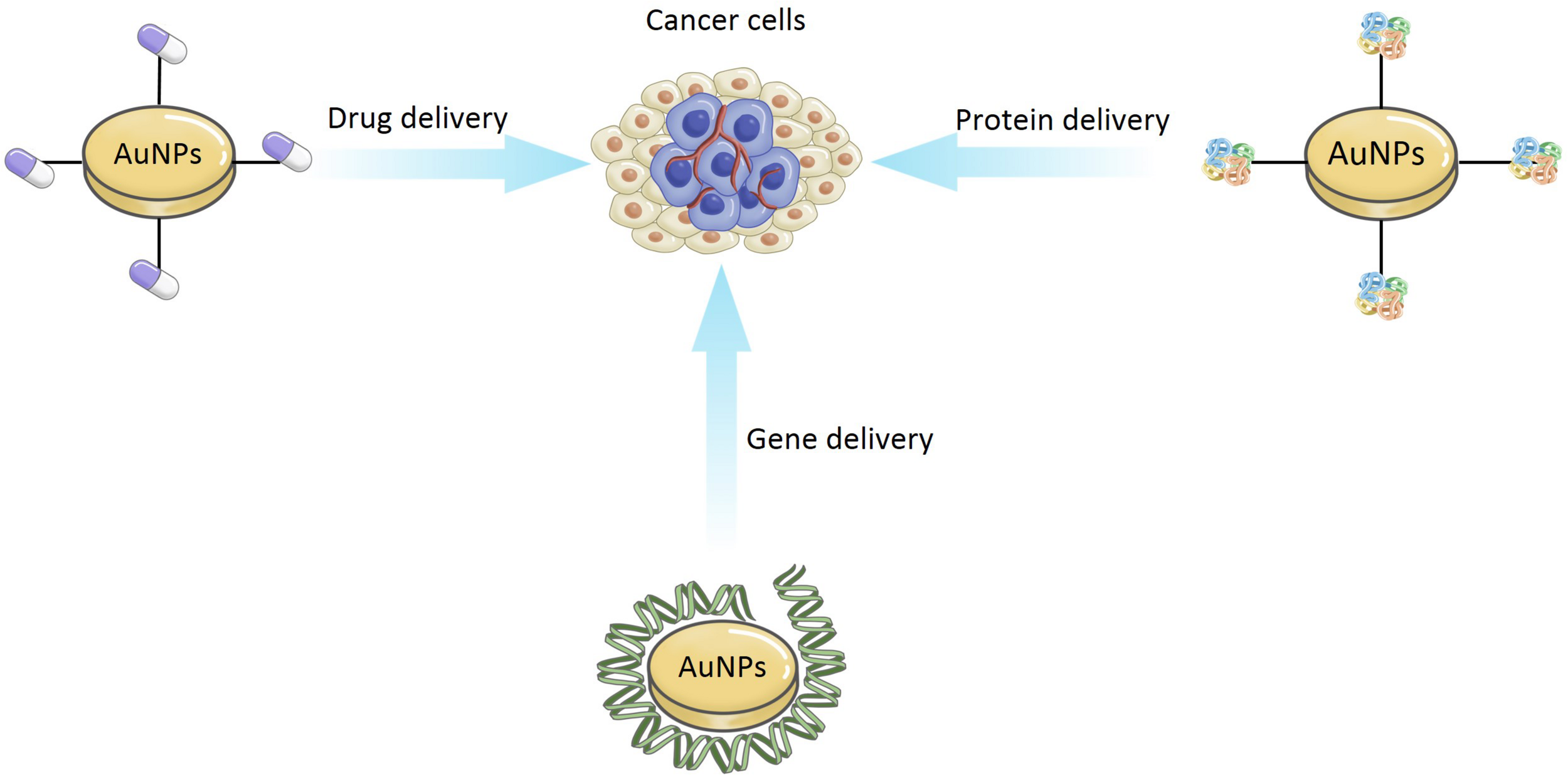

Delivery Carriers

In recent years, the idea of using AuNPs as delivery carriers has attracted the wide attention of researchers. As shown in Figure 9, AuNPs can be used for the delivery of drug, gene, and protein.

FIGURE 9

The application of delivery carriers for AuNPs.

Chemotherapy is the most common method of cancer therapy but its potential is limited in many cases. Traditional drug delivery (oral or intravenous administration) for chemotherapeutic drugs, results in the dissemination of the drug throughout the whole body, with only a fraction of the dose reaching the tumor site (Singh et al., 2018). Targeting of specific cells, organs, and tissues, in a controlled manner, has become a key issue and challenge. Drug delivery systems (DDSs) is a promising approach to general anticancer therapy, which may provide efficient targeted transport and overcome the limitation of biochemical barriers in the body, e.g., the brain blood barrier (Martinho et al., 2011). Moreover, DDSs can enable controlled function in delivering drugs for early detection of the diseases and damaged sites (Baek et al., 2016). There are many useful forms for drug delivery, including liposomes, liquid crystals, dendrimers, polymers, hydrogels, and nanoparticles (Yokoyama, 2014; Rigon et al., 2015). Among these, only a small number of polymers and liposomes have been clinically approved (Piktel et al., 2016). Thus, many researchers have started to focus on the popular AuNPs. AuNPs have been examined for potential anticancer drug delivery (Duncan et al., 2010). In addition, they also can be easily modified to transfer various drugs, which may be bound to AuNPs through physical encapsulation or by chemical (covalent or non-covalent) bonding. Conjugation of AuNPs with other drugs is also possible, but it should be remembered that functionalization can change the toxicity of AuNPs, and their ability to successfully load or attach the desired drugs. The use of modified AuNPs has reduced systemic drug toxicity and helped to decrease the possibility of the cancer developing drug resistance (Yokoyama, 2014). For example, Wójcik et al. (2015) using the MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) assay, confirmed that glutathione-stabilized AuNPs (GSH-AuNPs) modified with non-covalent conjugation of the DOX were more active against feline fibrosarcoma cell lines than the activity exhibited by unmodified AuNPs.

Gene therapy is the use of exogenous DNA or RNA to treat or prevent diseases. Viral vectors are commonly used but cannot be functionalized and can activate host immune systems (Riley and Vermerris, 2017). Their ‘design’ is inflexible, they target specific sites in a biological system with high cytotoxicity and reduce the efficiency of gene therapy (Riley and Vermerris, 2017). The use of non-viral vectors system (such as metallic nanoparticles) can solve this problem. Recent studies have shown that AuNPs can protect nucleic acids through preventing their degradation by nucleases (Klebowski et al., 2018). The unique properties of AuNPs, conjugated to oligonucleotides, can make them potential gene carriers, via covalent and non-covalent bonding. Covalent AuNPs can activate immune-related genes in peripheral blood mononuclear cells, but not in an immortalized and lineage-restricted cell line (Ding et al., 2014). This shows promise application in its application for gene delivery systems. For example, Shahbazi et al. (2019) synthesized AuNPs core using the citrate reduction method, and developed a CRISPR nanoformulation, using colloidal AuNPs (AuNPs/CRISPR), with guide RNA and nuclease on the surface of AuNPs, with or without a single-strand DNA (ss DNA) template to support homology-directed repair. The outcome was an efficient gene editing. They also demonstrated the non-toxicity delivery of entire CRISPR sequences into human blood stem and progenitor cells.

Recently, researchers have also found some evidence that AuNPs can be used as protein carriers. For instance, Joshi et al. (2006) obtained insulin directly bound to bare AuNPs (Au-insulin nanoparticles) via a covalent linkage, which have been confirmed more active than insulin bound via hydrogen bonds with amino acid-modified AuNPs (Au-Asp-insulin nanoparticles) in the transmucosal delivery of drugs for the treatment of diabetes. In this case, the efficiency of insulin delivery can be enhanced by coating the AuNPs with a non-toxic biopolymer, which can strongly adsorb insulin to its surface.

Therapeutics

In the following section, we will discuss photothermal therapy (PTT), photodynamic therapy (PDT), and radiation therapy (RT) applications of AuNPs, which continue to be under development (Figure 10).

FIGURE 10

The application of PTT, PDT and RT for AuNPs.

PTT, also known as thermal ablation or optical hyperthermia, is a non-invasive and is widely applied for cancer therapy due to its benefits of real-time observation of tumor sites and photoinduced destruction of tumor cells or tissues (Singh et al., 2020). PTT uses materials with a high photothermal conversion efficiency, injected into the body, which gather near the tumor tissues by targeting recognition technology (Murphy et al., 2010; Mubarakali et al., 2011). Under the irradiation of external light sources, usually visible or near-infrared (NIR) light, photothermal materials (such as metal nanoparticles) can convert light energy into heat energy (photothermal conversion), result in the destruction of the tumor tissue, and kill the cancer cells (Murphy et al., 2010; Mubarakali et al., 2011). AuNPs as a photothermal material, with maximum absorption in the visible or NIR region, have a high photothermal conversion efficiency due to their SPR effect. In addition, the SPR peak of AuNPs can be adjusted to the NIR region by controlling their geometrical and physical parameters, such as size and shape, which contribute to the depth of effective penetration of PTT (Boyer et al., 2002; Orendorff et al., 2006; Bibikova et al., 2017). Therefore, many researchers have been focusing on the different size and shape of AuNPs for application in PTT (both in vitro and in vivo) due to their absorption peaks being in the visible or NIR region and their ability to load and deliver various anticancer drugs (Sharifi et al., 2019; Sztandera et al., 2019). AuNPs used in PTT are generally nanorods or nanoshells but, when introduced into a biological environment, the cellular uptake can be limited (Kim and Lee, 2018). Tian et al. (2017) synthesized gold nanostars (AuNSs) with pH (low) insertion peptides (pHLIPs) (AuNSs-pHLIP). They have low toxicity, are plasmon tunable in the NIR region, and exhibited excellent biocompatibility and effective PTT (Tian et al., 2017).

PDT is another form of light therapy, developed in recent decades, and used to destroy cancer cells and pathogenic bacteria (Abrahamse and Hamblin, 2016). PDT involves visible light, photosensitizer (PS), and molecular oxygen (O2) from the tissues. PDT is completely dependent on the availability of O2 in tissues. The process of PDT is that the PS absorbed by the tissue, is excited by laser light of a specific wavelength. Irradiating the tumor site can activate the PS that selectively accumulate in the tumor tissue, triggering a photochemical reaction to destroy the tumor. The excited PS will transfer energy to the surrounding O2 to generate reactive oxygen species (ROS) and increase ROS level in the target sites. ROS can react with adjacent biological macromolecules to produce significant cytotoxicity, cell damage, even death or apoptosis (Imanparast et al., 2018; Falahati et al., 2019; Singh et al., 2020). As a PS, AuNPs can absorb the NIR light, accumulate in the tumor area, raise the temperature, and generate high levels of ROS, which can ultimately damage the tumor growth and promote cancer cell death (Jing et al., 2014). In addition, AuNPs have been considered for PS carriers due to their simple thiolation chemistry for the functionalization of desired molecules, enhancing its capability for loading PS drugs. For example, Yang et al. synthesized spherical AuNPs using UV-assisted reduction with sodium and chloroauric acid, and hollow gold nanorings with a sacrificial galvanic replacement method (Yang et al., 2018). They utilized AuNPs and gold nanorings as drug delivery carriers, with a PS enhancer, to compare and investigate the shape-dependent SPR response in PDT. They found that gold nanorings exhibited efficient PS activation and SPR in the NIR region. Therefore, these may be promising nanoparticles to address the current depth limitation of PDT, for deep tumor therapy.

Besides PTT and PDT, radiation therapy (RT) is one of the least invasive and commonly used methods in the treatment of various cancers (Sztandera et al., 2019). RT involves the delivery of high intensity ionizing radiations (such as γ-rays and X-rays) to tumor tissues, while simultaneously protecting the surrounding healthy cells, tissues, and organs, resulting in the death of tumor cells (Retif et al., 2015; Klebowski et al., 2018). γ-rays and X-rays are usually used to ionize cellular components (such as organelle) and water. Water is the main component of the cell, as well as the main target of the ionizing radiations, resulting in the lysis of the water molecules. This lysis is named radiolysis, which causes the formation of charged species and free radicals. The interaction of free radicals and membrane structure can also cause structural damage, leading to the apoptosis of cell (Kwatra et al., 2013). Recently, there have been many reports of radiosensitization using AuNPs in RT due to their high atomic number of gold (Jain S. et al., 2011; McMahon et al., 2011). The most probable mechanism of radiosensitization from AuNPs is that Auger electron production from the surface of the AuNPs can increase the production of ROS, reduce the total dose of radiation, and increase the dose administrated locally to the tumor sites, eventually resulting in cell death. Moreover, side effects can also be reduced (Jeynes et al., 2014; Retif et al., 2015).

Diagnostics

Diagnostics are very essential to medical science and clinical practice. Some diagnostic methods (such as immunoassay diagnosis) have been applied to clinical diagnosis but have limitations in precision molecular diagnostics because of their inaccuracy and low sensitivity (Ou et al., 2019). With the development of nanotechnology, the sensitivity, specificity, and multiplexing of diagnostic tests have been improved. AuNPs exhibit substantial and excellent optical properties, mainly including localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) and surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS), which play an important role in their application to diagnostics (Ou et al., 2019; Venditti, 2019). LSPR-based application of AuNPs is due to spectral modulation (Figure 11) (Ou et al., 2019). When the light is incident on the surface of AuNPs, if the incident photon frequency matches the overall vibration frequency of the electrons transmitted by the AuNPs, the AuNPs will strongly absorb the photon energy, and generate LSPR phenomenon, which is useful for diagnostics (Link and El-Sayed, 2003; Liu et al., 2011; Baek et al., 2016; Cordeiro et al., 2016). The LSPR peak of AuNPs is usually in the visible-NIR region, often at around 500 nm or from 800 and 1200 nm (Huang et al., 2009; Aldewachi et al., 2017). SERS is another very attractive spectroscopic technique in diagnostics, being non-invasive and having high sensitivity features (Boisselier and Astruc, 2009; Zhou et al., 2017). Fleischmann et al. (1974) reported the enhancement of a Raman scattering signal, which was the first observation of SERS. The enhancement of SERS can be explained by two mechanisms. One is the chemical enhancement due to charge transfer between gold atoms and molecules (Kawata et al., 2017). Another is the electromagnetic enhancement because of LSPR on the surface of metallic gold (Kawata et al., 2017). Spherical AuNPs are commonly used as the substrate for SERS, although non-spherical AuNPs have also been produced and explored for these applications (Tao et al., 2011; Yang et al., 2012). Nowadays, the phenomenon of LSPR and SERS in AuNPs has been widely used for the development of molecular diagnostics. For instance, El-Husseini et al. (2016) synthesized 15 nm unmodified citrate-coated AuNPs by the Frens method, for use in the diagnostic polymerase chain reaction (PCR) technique for detection of the equine herpes virus 1 (EHV-1). Their results showed that AuNPs-assisted PCR was more sensitive than the conventional PCR technique and, therefore, could be used as a more efficient molecular diagnostic tool for EHV-1.

FIGURE 11

The application of AuNPs on the LSPR.

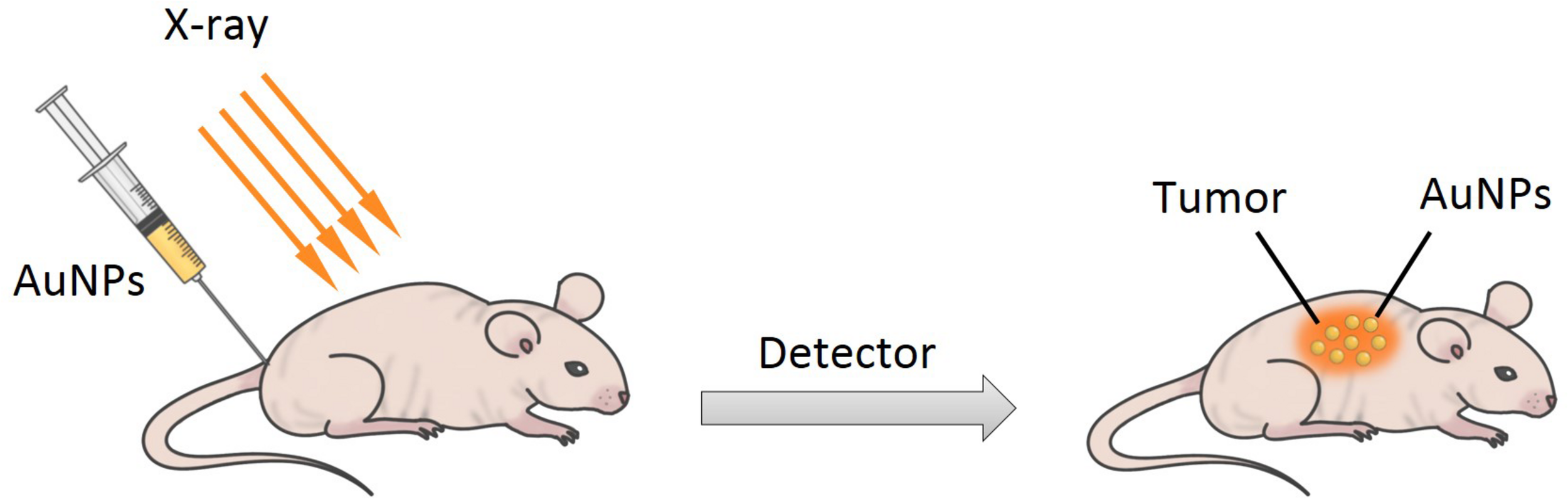

Imaging

X-ray computed tomography (CT) is one of the most important and mature tissue imaging techniques widely used in various research and clinical environments with broad availability and fairly low cost (Kim et al., 2007). Specifically, CT is a non-invasive clinical diagnostic tool that can perform 3D visual reconstruction and tissue segmentation (Lusic and Grinstaff, 2013). The images of CT are composed of X-ray images, which are taken at different angles by rotating around an object to form a cross-sectional 3D image called a CT scan (Lusic and Grinstaff, 2013; Fuller and Köper, 2019). According to the content of the images, the contrast agent can attenuate the X-ray to improve the image quality to highlight the specific area, such as the structure of blood vessels or organs (Lusic and Grinstaff, 2013). The basis of CT imaging is the fact that healthy and diseased tissues or cells have different densities, which can generate in a contrast between normal and abnormal cells by using contrasting agents (such as iodinated molecules) (Figure 12) (Cormode et al., 2014). Iodinated molecules are usually used as a contrasting agent, due to their unique X-ray absorption coefficient (Klebowski et al., 2018). However, their usage has its own limitations, such as short imaging times, rapid renal clearance, reduced sensitivity and specificity, toxicity, and vascular permeation (Chien et al., 2012; Mackey et al., 2014). Therefore, it is very essential to explore and develop novel materials as contrasting agents for X-ray imaging. In recent years, AuNPs are attracting attention in imaging as an X-ray contrast agent because they can strongly absorb ionizing radiation to enhance the coefficient of X-ray absorption and convert the light energy to heat energy through the SPR effect (Rahman et al., 2014). Moreover, AuNPs have some advantages compared to iodinated molecules such as ease of synthetic manipulation, unique optical and electrical properties, non-toxicity, higher electron density, higher atomic number of gold, and higher X-ray absorption coefficient (Mackey et al., 2014; Singh et al., 2017). The key factors for potential application of AuNPs in enhanced X-ray CT imaging are their migration and accumulation at target sites and longer vascular retention time, and these allow non-invasive tracking and visualizing of the therapeutic cells (Yin et al., 2017; Meir and Popovtzer, 2018). For example, Liu et al. (2018) synthesized 30–40 nm sized gold nanocages (AuNCs) as part of an activatable probe, to investigate the potential of imaging. The AuNCs were PEGylated via conjugation with SH-PEG-NH2. It is the first report to estimate protease activity in vivo using an imaging technique and activatable probe.

FIGURE 12

A simple scheme for X-ray imaging.

Others

Besides the various applications described above, some other applications involving antimicrobial (antibacterial and antifungal) activity, antioxidant activity, and anticancer activity need to be mentioned.

The increasing incidence of bacterial infection with drug resistance is a major issue for human health (Dutta et al., 2017). AuNPs are easily taken up by immune cells, due to their excellent cell affinity, which leads to precise delivery at the infected area, facilitating inhibition and damage to microbial pathogens (Saha et al., 2007). AuNPs show excellent antibacterial activity against E. coli by absorbing light and converting it into heat (Singh et al., 2009). The growing drug resistance of fungal strains also demands the development of new drugs for better treatment of fungal diseases. Among the various nanoparticles, AuNPs are sensitive to candida cells, which can inhibit the growth and kill the fungal pathogen C. albicans (Wani and Ahmad, 2013; Yu et al., 2016). They increase the ROS and damage the cell membrane by their unique properties, which include converting light to heat when irradiated and strong anionic binding with fungal plasma membrane (Wani and Ahmad, 2013; Yu et al., 2016). Cancer is caused by many factors and is considered one of the main causes for death worldwide. In tumor cells, AuNPs have a tendency to enter subcellular organelles and increase the cellular uptake, which enhances anticancer activity (Kajani et al., 2016). AuNPs can increase the ROS level, to destroy cancer cells. However, the biocompatibility and selectivity of AuNPs, in targeting tumors, remains an important challenge. Therefore, new developing methods are required to overcome the question. Excessive ROS can lead to enzyme deactivation and nucleic acid damage, which can itself lead to diseases diabetes, aging, and cancer (Li et al., 2009). Ramalingam (2019) synthesized AuNPs using NaBH4 and HAuCl4 as a reducing agent and precursor, respectively. Furthermore, they investigated and confirmed the anticancer activity of their AuNPs in human lung cancer cells, and antimicrobial activity against human clinical pathogens, such as P. aeruginosa, S. aureus, E. coli, V. cholera, Salmonella sp., K. pneumonia. Their results suggested that AuNPs could potentially act as anticancer and antimicrobial agents. Moreover, AuNPs have also been confirmed as a potential antioxidant agent. They can inhibit the formation of ROS, thus increasing the antioxidant activity of defensive enzymes. The synergism and antagonism of AuNPs, in their antioxidant activity, require further investigation (Ramalingam, 2019). For instance, Tahir et al. (2015) produced AuNPs (2–10 nm) using the extract of Nerium oleander leaf, in a one-step, green synthetic method, and these AuNPs showed good antioxidant activity. Furthermore, the results showed that the extract of Nerium oleander leaf was very active for the reduction of AuNPs, and could be used as a reducing agent.

Conclusion

In summary, since Faraday first reported AuNPs in 1857 (Faraday, 1857), there have been many reports focusing on their synthesis, as well as comparisons with other metallic nanoparticles or noble metallic nanoparticles. In this review, we have described the synthesis and modification of AuNPs, the techniques of characterization, and their diverse medical applications and biological activities. Since the yield is low, using a top–down approach, a series of synthetic approaches to the production of AuNPs have been proposed. Additionally, the unique properties of AuNPs suggest its broad applications, including drug and gene delivery, PTT, photodynamic therapy (PDT), diagnosis, and imaging. Moreover, further applications, arising from their antimicrobial (antibacterial and antifungal), antioxidant, and anticancer activities, have also been discussed. As the properties of AuNPs become better understood, a considerable number of principal experiments and studies are needed to focus on function, along with the design of different therapies, generally involving PTT and PDT. Although the antimicrobial, anticancer, and antioxidant activities of AuNPs have been confirmed, they remain to be used in clinical treatment. As a drug and gene carrier, AuNPs may also have broad applications, in the future. Although AuNPs possess many useful properties, some studies have demonstrated their toxic effects, based on their physicochemical properties. Sabella et al. (2014) showed that the toxicity of AuNPs was related to their cellular internalization pathways. The safety of AuNPs remains a very urgent and controversial issue, as more important concerns are raised, and this needs to be properly addressed. In recent studies, researchers have reduced the toxicity of AuNPs by introducing functional groups to their surface, improved existing methods of synthesis, and have developed new and better methods. In conclusion, the unique properties of AuNPs should be identified, such as their optical properties with SPR bands, and as carriers with anticancer activity, to broaden their applications in various fields.

Statements

Author contributions

XH wrote the manuscript. YZ collected the literature and generated the figures and tables. TD edited and checked the manuscript format. JL and HZ reviewed the manuscript. All the authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundations of China (Nos. 81922020 and 81970950), the Postdoctoral Research and Development Funding of Sichuan University (2020SCU12016), and the Research Funding for Talents Developing, West China Hospital of Stomatology Sichuan University (Nos. RCDWJS2020-4 and RCDWJS2020-14).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1

AbrahamseH.HamblinM. R. (2016). New photosensitizers for photodynamic therapy.Biochem. J.473347–364. 10.1042/BJ20150942

2

AhmadT.WaniI. A.ManzoorN.AhmedJ.AsiriA. M. (2013). Biosynthesis, structural characterization and antimicrobial activity of gold and silver nanoparticles.Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces107227–234. 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2013.02.004

3

AhnS.SinghP.JangM.KimY. J.Castro-AceitunoV.SimuS. Y.et al (2017). Gold nanoflowers synthesized using Acanthopanacis cortex extract inhibit inflammatory mediators in LPS-induced RAW264.7 macrophages via NF-κB and AP-1 pathways.Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces160423–428. 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2017.09.053

4

AldewachiH.ChalatiT.WoodroofeM. N.BricklebankN.SharrackB.GardinerP. (2017). Gold nanoparticle-based colorimetric biosensors.Nanoscale1018–33. 10.1039/C7NR06367A

5

AllecN.ChoiM.YesupriyaN.SzychowskiB.WhiteM. R.KannM. G.et al (2015). Small-angle X-ray scattering method to characterize molecular interactions: proof of concept.Sci. Rep.5:12085. 10.1038/srep12085

6

AmblardJ.BelloniJ.RemitaH.KhatouriJ.CointetC.MostafaviM. (2002). Dose rate effects on radiolytic synthesis of gold-silver bimetallic clusters in solution.J. Phys. Chem. B1024310–4321. 10.1021/jp981467n

7

AsadishadB.VossoughiM.AlemzadehI. (2010). Folate-receptor-targeted delivery of doxorubicin using polyethylene glycol-functionalized gold nanoparticles.Ind. Eng. Chem. Res.491958–1963. 10.1021/ie9011479

8

AzharuddinM.ZhuG. H.DasD.OzgurE.UzunL.TurnerA. P. F.et al (2019). A repertoire of biomedical applications of noble metal nanoparticles.Chem. Commun.556964–6996. 10.1039/c9cc01741k

9

AzzamE. M. S.MorsyS. M. I. (2008). Enhancement of the antitumour activity for the synthesised dodecylcysteine surfactant using gold nanoparticles.J. Surfactants Deterg.11195–199. 10.1007/s11743-008-1072-8

10

BaekS. M.SinghR. K.KimT. H.SeoJ. W.ShinU. S.ChrzanowskiW.et al (2016). Triple hit with drug carriers: pH- and temperature-responsive theranostics for multimodal chemo- and photothermal-therapy and diagnostic applications.ACS Appl. Mater Interfaces88967–8979. 10.1021/acsami.6b00963

11

BalfourierA.LucianiN.WangG.LelongG.ErsenO.KhelfaA.et al (2019). Unexpected intracellular biodegradation and recrystallization of gold nanoparticles.Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.117103–113. 10.1073/pnas.1911734116

12

BastusN. G.ComengeJ.PuntesV. (2011). Gold nanoparticles of up to 200nm: size focusing versus Ostwald ripening.Langmuir2711098–11105. 10.1021/la201938u

13

BhosaleM. A.ChennaD. R.BhanageB. M. (2017). Ultrasound assisted synthesis of gold nanoparticles as an efficient catalyst for reduction of various nitro compounds.Chemistryselect21225–1231. 10.1002/slct.201601851

14

BibikovaO.SinghP.PopovA.AkchurinG.SkaptsovA.SkovorodkinI.et al (2017). Shape-dependent interaction of gold nanoparticles with cultured cells at laser exposure.Laser Phys. Lett.14:055901. 10.1088/1612-202X/aa63ae

15

BoisselierE.AstrucD. (2009). Gold nanoparticles in nanomedicine: preparations, imaging, diagnostics, therapies and toxicity.Chem. Soc. Rev.381759–1782. 10.1039/B806051G

16

BorkerS.PatoleM.MogheA.PokharkarV. (2016). Engineering of glycyrrhizin capped gold nanoparticles for liver targeting: in vitro evaluation and in vivo biodistribution study.RSC Adv.644944–44954. 10.1039/C6RA05202A

17

BorkowskaM.SiekM.KolyginaD. V.SobolevY. I.LachS.KumarS.et al (2020). Targeted crystallization of mixed-charge nanoparticles in lysosomes induces selective death of cancer cells.Nat. Nanotechnol.15331–341. 10.1038/s41565-020-0643-3

18

BoyerD.TamaratP.MaaliA.LounisB.OrritM. (2002). Photothermal imaging of nanometer-sized metal particles among scatterers.Science2971160–1163. 10.1126/science.1073765

19

BrownK. R.WalterD. G.NatanM. J. (1999). Seeding of colloidal Au nanoparticle solutions. 2. improved control of particle size and shape.Chem. Mater.12306–313. 10.1021/cm980065p

20

ChandranP. R.SandhyaraniN. (2014). An electric field responsive drug delivery system based on chitosan–gold nanocomposites for site specific and controlled delivery of 5-fluorouracil.RSC Adv.444922–44929. 10.1039/C4RA07551J

21

ChenH.KouX.YangZ.NiW.WangJ. (2008). Shape- and sizedependent refractive index sensitivity of gold nanoparticles.Langmuir245233–5237. 10.1021/la800305j

22

ChenJ.MelaP.MollerP.LensenM. C. (2009). Microcontact deprinting: a technique to pattern gold nanoparticles.ACS Nano31451–1456. 10.1021/nn9002924

23

ChienC. C.ChenH. H.LaiS. F.HwuY.PetiboisC.YangC. S.et al (2012). X-ray imaging of tumor growth in live mice by detecting gold-nanoparticle-loaded cells.Sci. Rep.2:610. 10.1038/srep00386

24

CordeiroM.CarlosF. F.PedrosaP.LopezA.BaptistaP. V. (2016). Gold nanoparticles for diagnostics: advances towards points of care.Diagnostics6:43. 10.3390/diagnostics6040043

25

CormodeD. P.NahaP. C.FayadZ. A. (2014). Nanoparticle contrast agents for computed tomography: a focus on micelles.Contrast Med. Mol. Imaging937–52. 10.1002/cmmi.1551

26

CorreardF.MaximovaK.EsteveM. A.VillardC.RoyM.Al-KattanA.et al (2014). Gold nanoparticles prepared by laser ablation in aqueous biocompatible solutions: assessment of safety and biological identity for nanomedicine applications.Int. J. Nanomed.95415–5430. 10.2147/IJN.S65817

27

DahoumaneS. A.WujcikE. K.JeffryesC. (2016). Noble metal, oxide and chalcogenidebased nanomaterials from scalable phototrophic culture systems.Enzyme Microb. Technol.9513–27. 10.1016/j.enzmictec.2016.06.008

28

DamD. H.CulverK. S.OdomT. W. (2014). Grafting aptamers onto gold nanostars increases in vitro efficacy in a wide range of cancer cell types.Mol. Pharm.11580–587. 10.1021/mp4005657

29

DashS. S.MajumdarR.SikderA. K. (2014). Saraca indicabark extract mediated green synthesis of polyshaped gold nanoparticles and its application in catalytic reduction.Appl. Nanosci.4485–490. 10.1007/s13204-013-0223-z

30

DingY.JiangZ.SahaK.KimC. S.KimS. T.LandisR. F.et al (2014). Gold nanoparticles for nucleic acid delivery.Mol. Ther.221075–1083. 10.1038/mt.2014.30

31

DreadenE. C.AlkilanyA. M.HuangX.MurphyC. J.El-SayedM. A. (2012). The golden age: gold nanoparticles for biomedicine.Chem. Soc. Rev.412740–2779. 10.1039/C1CS15237H

32

DubeyS. P.LahtinenM.SillanpM. (2010). Green synthesis and characterizations of silver and gold nanoparticles using leaf extract of Rosa rugosa.Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp.364, 34–41. 10.1016/j.colsurfa.2010.04.023

33

DuncanB.KimC.RotelloV. M. (2010). Gold nanoparticle plateforms as drug and biomolecule delivery systems.J. Control. Release148122–127. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.06.004

34

DuttaJ.NaickerT.EbenhanT.KrugerH. G.ArvidssonP. I.GovenderT. (2017). Synthetic approaches to radiochemical probes for imaging of bacterial infections.Eur. J. Med. Chem.133287–308. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2017.03.060

35

El-HusseiniD. M.HelmyN. M.TammamR. H. (2016). The effect of gold nanoparticles on the diagnostic polymerase chain reaction technique for equine herpes virus 1 (EHV-1).RSC Adv.654898–54903. 10.1039/C6RA08513J

36

Falagan-LotschP.GrzincicE. M.MurphyC. J. (2016). One low-dose exposure of gold nanoparticles induces long-term changes in human cells.Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.11313318–13323. 10.1073/pnas.1616400113

37

FalahatiM.AttarF.SharifiM.SabouryA. A.SalihiA.AzizF. M.et al (2019). Gold nanomaterials as key suppliers in biological and chemical sensing, catalysis, and medicine.Biochim. Biophys. Acta1864:129435. 10.1016/j.bbagen.2019.129435

38

FaradayM. (1857). Experimental relations of gold (and other metals) to light.Philos. Trans. R. Soc.147145–181. 10.1080/14786445708642410

39

FilipG. A.MoldovanB.BaldeaI.OlteanuD.SuharoschiR.DeceaN.et al (2019). UV-light mediated green synthesis of silver and gold nanoparticles using Cornelian cherry fruit extract and their comparative effects in experimental inflammation.J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol.19126–37. 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2018.12.006

40

FleischmannM.HendraP. J.McQuillanA. J. (1974). Raman spectra of pyridine adsorbed at a silver electrode.Chem. Phys. Lett.26163–166. 10.1016/0009-2614(74)85388-1

41

FrensG. (1973). Controlled nucleation for the regulation of the particle size in monodisperse gold suspensions.Nat. Phys. Sci.24120–22. 10.1038/10.1038/physci241020a0

42

FullerM. A.KöperI. (2019). Biomedical applications of polyelectrolyte coated spherical gold nanoparticles.Nano Converg.6:11. 10.1186/s40580-019-0183-4

43

Gardea-TorresdeyJ. L.TiemannK. J.GamezG.DokkenK.TehuacaneroS.Jose-yacamanM. (1999). Gold nanoparticles obtained by bio-precipitation from gold(III) solutions.J. Nano Res.1397–404. 10.1023/a:1010008915465

44

GarzaM.HernándezT.ColásR.GómezI. (2010). Deposition of gold nanoparticles on glass substrate by ultrasonic spray pyrolysis.Mater. Sci. Eng. B1749–12. 10.1016/j.mseb.2010.03.068

45

González-RubioG.Guerrero-MartínezA.Liz-MarzánL. M. (2016). Reshaping, fragmentation, and assembly of gold nanoparticles assisted by pulse lasers.Acc. Chem. Res.49678–686. 10.1021/acs.accounts.6b00041

46

GovindarajuK.BashaS. K.KumarV. G.SingaraveluG. (2008). Silver, gold and bimetallic nanoparticles production using single-cell protein (Spirulina platensis) Geitler.J. Mater. Sci.435115–5122. 10.1007/s10853-008-2745-4

47

GuravD. D.JiaY. A.YeJ.QianK. (2019). Design of plasmonic nanomaterials for diagnostic spectrometry.Nanoscale Adv.1459–469. 10.1039/C8NA00319J

48

HostaL.Pla-RocaM.ArbiolJ.Lopez-IglesiasC.SamitierJ.CruzL. J.et al (2009). Conjugation of Kahalalide F with gold nanoparticles to enhance in vitro antitumoral activity.Bioconjug. Chem.20138–146. 10.1021/bc800362j

49

HuR.ZhengM.WuJ.LiC.ShenD.YangD.et al (2017). Core-shell magnetic gold nanoparticles for magnetic field-enhanced radio-photothermal therapy in cervical cancer.Nanomaterials7:111. 10.3390/nano7050111

50

HuangC. C.LiaoH. Y.ShiangY. C.LinZ. H.YangZ. S.ChangH. T. (2009). Synthesis of wavelength-tunable luminescent gold and gold/silver nanodots.J. Mater. Chem.19755–759. 10.1039/B808594C

51

ImanparastA.BakhshizadehM.SalekR.SazgarniaA. (2018). Pegylated hollow goldmitoxantrone nanoparticles combining photodynamic therapy and chemotherapy of cancer cells.Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther.23295–305. 10.1016/j.pdpdt.2018.07.011

52

JainN.BhargavaA.MajumdarS.TarafdarJ. C.PanwarJ. (2011). Extracellular biosynthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles using Aspergillus flavus NJP08: a mechanism perspective.Nanoscale3635–641. 10.1039/c0nr00656d

53

JanaN. R.GearheartL.MurphyC. J. (2001). Seeding growth for size control of 5-40nm diameter gold nanoparticles.Langmuir176782–6786. 10.1021/la0104323

54

JainS.CoulterJ. A.HounsellA. R.ButterworthK. T.McmahonS. J.HylandW. B.et al (2011). Cell-specific radiosensitization by gold nanoparticles at megavoltage radiation energies.Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. Int.79531–539. 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.08.044

55

JeynesJ. C. G.MerchantM. J.SpindlerA.WeraA. C.KirkbyK. J. (2014). Investigation of gold nanoparticle radiosensitization mechanisms using a free radical scavenger and protons of different energies.Phys. Med. Biol.596431–6443. 10.1088/0031-9155/59/21/6431

56

JiX.SongX.LiJ.BaiY.YangW.PengX. (2007). Size Control of Gold Nanocrystals in citrate reduction: the third role of citrate.J. Am. Chem. Soc.12913939–13948. 10.1021/ja074447k

57

JimenezI. O.RomeroF. M.BastusN. G.PuntesV. (2010). Small gold nanoparticles synthesized with sodium citrate and heavy water: insights into the reaction mechanism.J. Phys. Chem. C1141800–1804. 10.1021/jp9091305

58

JingH.ZhangQ.LargeN.YuC.BlomD. A.NordlanderP.et al (2014). Tunable plasmonic nanoparticles with catalytically active high-index facets.Nano Lett.143674–3682. 10.1021/nl5015734

59

JoshiH. M.BhumkarD. R.JoshiK.PokharkarV.SastryM. (2006). Gold nanoparticles as carriers for efficient transmucosal insulin delivery.Langmuir22300–305. 10.1021/la051982u

60

KajaniA. A.BordbarA.-K.Zarkesh EsfahaniS. H.RazmjouA. (2016). Gold nanoparticles as potent anticancer agent: green synthesis, characterization, and in vitro study.RSC Adv.663973–63983. 10.1039/C6RA09050H

61

KasthuriJ.VeerapandianS.RajendiranN. (2008). Biological synthesis of silver and gold nanoparticles using apiin as reducing agent.Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces6855–60. 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2008.09.021

62

KawataS.IchimuraT.TaguchiA.KumamotoY. (2017). Nano-raman scattering microscopy: resolution and enhancement.Chem. Rev.1174983–5001. 10.1021/acs.CheMrev.6b00560

63

KhanI.SaeedK.KhanI. (2017). Nanoparticles: properties, applications and toxicities.Arab. J. Chem.12908–931. 10.1016/j.arabjc.2017.05.011

64

KhanT.UllahN.KhanM. A.MashwaniZ. R.NadhmanA. (2019). Plant-based gold nanoparticles: a comprehensive review of the decade-long research on synthesis, mechanistic aspects and diverse applications.Adv. Colloid Int. Sci.272:102017. 10.1016/j.cis.2019.102017

65

KhannaP.KaurA.GoyalD. (2019). Algae-based metallic nanoparticles: synthesis, characterization and applications.J. Microbiol. Methods163:105656. 10.1016/j.mimet.2019.105656

66

KimD.ParkS.LeeJ. H.JeongY. Y.JonS. (2007). Antibiofouling polymer-coated gold nanoparticles as a contrast agent for in vivo X-ray computed tomography imaging.J. Am. Chem. Soc.1297661–7665. 10.1021/ja076341v

67

KimH. S.LeeD. Y. (2018). Near-infrared-responsive cancer photothermal and photodynamic therapy using gold nanoparticles.Polymers10:961. 10.3390/polym10090961

68

KlebowskiB.DepciuchJ.Parlińska-WojtanM.BaranJ. (2018). Applications of noble metal-based nanoparticles in medicine.Int. J. Mol. Sci.19:4031. 10.3390/ijms19124031

69

KumarS. A.ChangY. T.WangS. F.LuH. C. (2010). Synthetic antibacterial agent assisted synthesis of gold nanoparticles: characterization and application studies.J. Phys. Chem. Solids711484–1490. 10.1016/j.jpcs.2010.07.015

70

KwatraD.VenugopalA.AnantS. (2013). Nanoparticles in radiation therapy: a summary of various approaches to enhance radiosensitization in cancer.Transl. Cancer Res.2330–342. 10.3978/j.issn.2218-676X.2013.08.06

71

LeG. M.PaquirissamyA.GargouriD.FaddaG.TestardF.Aymes-ChodurC.et al (2019). Irradiation effects on polymer-grafted gold nanoparticles for cancer therapy.ACS Appl. Bio Mater.2144–154. 10.1021/acsabm.8b00484

72

LeeJ.LeeS. Y.LimD. K.AhnD. J.LeeS. (2019). Antifreezing gold colloids.J. Am. Chem. Soc.14118682–18693. 10.1021/jacs.9b05526

73

LeffD. V.OharaP. C.HeathJ. R.GelbartW. M. (1995). Thermodynamic control of gold nanocrystal size: experiment and theory.J. Phys. Chem.997036–7041. 10.1021/j100018a041

74

LeonovA. P.ZhengJ.ClogstonJ. D.SternS. T.PatriA. K.WeiA. (2008). Detoxification of gold nanorods by treatment with polystyrenesulfonate.ACS Nano22481–2488. 10.1021/nn800466c

75

LiC.HsiehJ. H.HungM.HuangB. Q.SongY. L.DenayerJ.et al (2004). Ultrasonic spray pyrolysis for nanoparticles synthesis.J. Mater. Sci.93647–3657. 10.1023/b:jmsc.0000030718.76690.11

76

LiH.MaX.DongJ.QianW. (2009). Development of methodology based on the formation process of gold nanoshells for detecting hydrogen peroxide scavenging activity.Anal. Chem.818916–8922. 10.1021/ac901534b

77

LiS.ZhangL.WangT.LiL.WangC.SuZ. (2015). The facile synthesis of hollow Au nanoflowers for synergistic chemo-photothermal cancer therapy.Chem. Commun.5114338–14341. 10.1039/C5CC05676D

78

LinX.LiuS.ZhangX.ZhuR.YangH. (2019). Ultrasound activated vesicle of janus au-mno nanoparticles for promoted tumor penetration and sono-chemodynamic therapy of orthotopic liver cancer.Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl.591682–1688. 10.1002/anie.201912768

79

LinkS.El-SayedM. A. (2003). Optical properties and ultrafast dynamics of metallic nanocrystals.Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem.54331–366. 10.1146/annurev.physchem.54.011002.103759

80

LiuC.JiaQ.YangC.QiaoR.JingL.WangL. X. (2011). Lateral flow immunochromatographic assay for sensitive pesticide detection by using Fe3O4 nanoparticle aggregates as color reagents.Anal. Chem.836778–6784. 10.1021/ac201462d

81

LiuC.LiS.GuY.XiongH.WongW.SunL. (2018). Multispectral photoacoustic imaging of tumor protease activity with a gold nanocage-based activatable probe.Mol. Imaging Biol.20919–929. 10.1007/s11307-018-1203-1

82

LoynachanC.SoleimanyA. P.DudaniJ. S.LinY.NajerA.BekdemirA.et al (2019). Renal clearable catalytic gold nanoclusters for in vivo disease monitoring.Nat. Nanotechnol.14883–890. 10.1038/s41565-019-0527-6

83

LuL.SunG.ZhangH.WangH.XiS.HuJ.et al (2004). Fabrication of core-shell Au-Pt nanoparticle film and its potential application as catalysis and SERS substrate.J. Mater. Chem.141005–1009. 10.1039/B314868H

84

LuoJ.DengW.YangF.WuZ.HuangM.GuM. (2018). Gold nanoparticles decorated graphene oxide/nanocellulose paper for NIR laser-induced photothermal ablation of pathogenic bacteria.Carbohydr. Polymers198206–214. 10.1016/j.carbpol.2018.06.074

85

LusicH.GrinstaffM. K. (2013). X-ray-Computed Tomography contrast agents.Chem. Rev.1131641–1666. 10.1021/cr200358s

86

MackeyM. A.AliM. R. K.AustinL. A.NearR. D.El-SayedM. A. (2014). The most effective gold nanorod size for plasmonic photothermal therapy: theory and in vitro experiments.J. Phys. Chem. B1181319–1326. 10.1021/jp409298f

87

MarquisB. J.LoveS. A.BraunK. L.HaynesC. L. (2009). Analytical methods to assess nanoparticle toxicity.Analyst134425–439. 10.1039/b818082b

88

MartinhoN.DamgéC.ReisC. P. (2011). Recent advances in drug delivery systems.J. Biomater. Nanobiotechnol.2510–526. 10.4236/jbnb.2011.225062

89

McMahonS. J.HylandW. B.MuirM. F.CoulterJ. A.JainS.ButterworthK. T.et al (2011). Nanodosimetric effects of gold nanoparticles in megavoltage radiation therapy.Radiother. Oncol.100412–416. 10.1016/j.radonc.2011.08.026

90

MeirR.PopovtzerR. (2018). Cell tracking using gold nanoparticles and computed tomography imaging.Wiley Int. Rev. Nanomed. Nanobiotechnol.10:e1480. 10.1002/wnan.1480

91

MoritaM.TachikawaT.SeinoS.TanakaK.MajimaT. (2017). Controlled synthesis of gold nanoparticles on fluorescent nanodiamond via electron-beam-induced reduction method for dual-modal optical and electron bioimaging.ACS Appl. Nano Mater.1355–363. 10.1038/srep44495

92

MubarakaliD.ThajuddinN.JeganathanK.GunasekaranM. (2011). Plant extract mediated synthesis of silver and gold nanoparticles and its antibacterial activity against clinically isolated pathogens.Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces85360–365. 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2011.03.009

93

MurphyC. J.ThompsonL. B.AlkilanyA. M.SiscoP. N.BoulosS. P.StivapalanS. T.et al (2010). The many faces of gold nanorods.J. Phys. Chem. Lett.12867–2875. 10.1021/Jz100992x

94

NatanM. J.BrownK. R. (1998). Hydroxylamine seeding of colloidal au nanoparticles in solution and on surfaces.Langmuir14726–728. 10.1021/la970982u

95

NiC.ZhouJ.KongN.BianT.ZhangY.HuangX.et al (2019). Gold nanoparticles modulate the crosstalk between macrophages and periodontal ligament cells for periodontitis treatment.Biomaterials206115–132. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2019.03.039

96

NieW.ZhangY.YuH.LiR.HeR.DongN.et al (2018). Plasmonic nanoparticles embedded in single crystals synthesized by gold ion implantation for enhanced optical nonlinearity and efficient Q-switched lasing.Nanoscale104228–4236. 10.1039/C7NR07304F

97

NishanthiR.MalathiS.PaulJ. S.PalaniP. (2019). Green synthesis and characterization of bioinspired silver, gold and platinum nanoparticles and evaluation of their synergistic antibacterial activity after combining with different classes of antibiotics.Mater. Sci. Eng. C96693–707. 10.1016/j.msec.2018.11.050

98

O’NealD. P.HirschL. R.HalasN. J.PayneJ. D.WestJ. L. (2004). Photothermal tumor ablation in mice using near infrared-absorbing nanoparticles.Cancer Lett.209171–176. 10.1016/j.canlet.2004.02.004

99

OrendorffC. J.SauT. K.MurphyC. J. (2006). Shape-dependent plasmon-resonant gold nanoparticles.Small2636–639. 10.1002/smll.200500299

100

OuJ.ZhouZ.ChenZ.TanH. (2019). Optical diagnostic based on functionalized gold nanoparticles.Int. J. Mol. Sci.20:4346. 10.3390/ijms20184346

101

PhilipA.AnkudzeB.PakkanenT. T. (2018). Polyethylenimine-assisted seed-mediated synthesis of gold nanoparticles for surface-enhanced Raman scattering studies.Appl. Surf. Sci.444243–252. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2018.03.042

102

PiktelE.NiemirowiczK.WatekM.WollnyT.DeptułaP.BuckiR. (2016). Recent insights in nanotechnology-based drugs and formulations designed for effective anti-cancer therapy.J. Nanobiotechnol.14:39. 10.1186/s12951-016-0193-x

103

PissuwanD.CamillaG.MongkolsukS.CortieM. B. (2019). Single and multiple detections of foodborne pathogens by gold nanoparticle assays.WIREs Nanomed. Nanobiotechnol.12:1584. 10.1002/wnan.1584

104

PodsiadloP.SinaniV. A.BahngJ. H.KamN. W. S.LeeJ.KotovN. A. (2008). Gold nanoparticles enhance the anti-Leukemia action of a 6-Mercaptopurine chemotherapeutic agent.Langmuir24568–574. 10.1021/la702782k

105

PoinernG. E. J. (2014). A Laboratory Course in Nanoscience and Nanotechnology.Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. 10.1080/00107514.2015.1133713

106

PremaP.IniyaP. A.ImmanuelG. (2015). Microbial mediated synthesis, characterization, antibacterial and synergistic effect of gold nanoparticles using Klebsiella pneumoniae (MTCC-4030).RSC Adv.64601–4607. 10.1039/C5RA23982F

107

QuesterK.Avalos-BorjaM.Castro-LongoriaE. (2013). Biosynthesis and microscopicstudy of metallic nanoparticles.Micron541–27. 10.1016/j.micron.2013.07.003

108

RahmanW. N.GesoM.YagiN.Abdul AzizS. A.CordeS.AnnabellN. (2014). Optimal energy for cell radiosensitivity enhancement by gold nanoparticles using synchrotronbased monoenergetic photon beams.Int. J. Nanomed.92459–2467. 10.2147/IJN.S59471

109

RamalingamV. (2019). Multifunctionality of gold nanoparticles: plausible and convincing properties.Adv. Colloid Int. Sci.271:101989. 10.1016/j.cis.2019.101989

110

RamalingamV.RajaS.SundaramahalingamT. S.RajaramR. (2019). Chemical fabrication of graphene oxide nanosheets attenuates biofilm formation of human clinical pathogens.Bioorg. Chem.83326–335. 10.1016/j.bioorg.2018.10.052

111

RamalingamV.RajaramR.PremkumarC.SanthanamP.DhineshP.VinothkumarS.et al (2014). Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles from deep sea bacterium Pseudomonas aeruginosa JQ989348 for antimicrobial, antibiofilm, and cytotoxic activity.J. Basic Microbiol.54928–936. 10.1002/jobm.201300514

112

RamalingamV.RevathideviS.ShanmuganayagamT. S.MuthulakshmiL.RajaramR. (2017). Gold nanoparticle induces mitochondria-mediated apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in nonsmall cell lung cancer cells.Gold Bull.50177–189. 10.1007/s13404-017-0208-x

113

RayT. R.LettiereB.De RutteJ.PennathurS. (2015). Quantitative characterization of the colloidal stability of metallic nanoparticles using uv-vis absorbance spectroscopy.Langmuir313577–3586. 10.1021/la504511j

114

RetifP.PinelS.ToussaintM.FrochotC.ChouikratR.BastogneT.et al (2015). Nanoparticles for radiation therapy enhancement: the key parameters.Theranostics51030–1044. 10.7150/thno.11642

115

RiedelR.MahrN.YaoC.WuA.YangF.HamppN. (2020). Synthesis of gold-silica core-shell nanoparticles by pulsed laser ablation in liquid and their physico-chemical properties towards photothermal cancer therapy.Nanoscale123007–3018. 10.1039/C9NR07129F

116

RigonR. B.OyafusoM. H.FujimuraA. T.GoncalezM. L.do PradoA. H.Daflon-GremiaoM. P.et al (2015). Nanotechnology-based drug delivery systems for melanoma antitumoral therapy: a review.Biomed Res. Int.2015:841817. 10.1155/2015/841817

117

RileyM. K.VermerrisW. (2017). Recent advances in nanomaterials for gene delivery-a review.Nanomaterials7:94. 10.3390/nano7050094

118

Rodriguez-FernandezJ.Perez-JusteJ.Garcia de AbajoF. J.Liz-MarzanL. M. (2006). Seeded growth of submicron Au colloids with quadrupole plasmon resonance modes.Langmuir227007–7010. 10.1021/la060990n

119

RodunerE. (2006). Size matters: why nanomaterials are different.Chem. Soc. Rev.35583–592. 10.1039/b502142c

120

RossiA.DonatiS.FontanaL.PorcaroF.BattocchioC.ProiettiE.et al (2016). Negatively charged gold nanoparticles as a dexamethasone carrier: stability in biological media and bioactivity assessment in vitro.RSC Adv.699016–99022. 10.1039/C6RA19561J

121

SabellaS.CarneyR. P.BrunettiV.MalvindiM. A.Al-JuffaliN.VecchioG.et al (2014). A general mechanism for intracellular toxicity of metal-containing nanoparticles.Nanoscale67052–7061. 10.1039/c4nr01234h

122

SahaB.BhattacharyaJ.MukherjeeA.GhoshA. K.SantraC. R.DasguptaA. K.et al (2007). In vitro structural and functional evaluation of gold nanoparticles conjugated antibiotics.Nanoscale Res. Lett.2614–622. 10.1007/s11671-007-9104-2

123

SantS.TaoS. L.FisherO. Z.XuQ.PeppasN. A.KhademhosseiniA. (2012). Microfabrication technologies for oral drug delivery.Adv. Drug. Deliv. Rev.64496–507. 10.1016/j.addr.2011.11.013

124

ShahM.FawcettD.SharmaS.TripathyS. K.PoinernG. E. J. (2015). Green synthesis of metallic nanoparticles via biological entities.Materials87278–7308. 10.3390/ma8115377

125

ShahbaziR.Sghia-HughesG.ReidJ. L.KubekS.HaworthK. G.HumbertO.et al (2019). Targeted homology-directed repair in blood stem and progenitor cells with CRISPR nanoformulations.Nat. Mater.181124–1132. 10.1038/s41563-019-0385-5

126

SharifiM.AttarF.SabouryA. A.AkhtariK.HooshmandN.HasanA.et al (2019). Plasmonic gold nanoparticles: optical manipulation, imaging, drug delivery and therapy.J. Control. Release31170–189. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2019.08.032

127

SharmaA.SharmaS.SharmaK.ChetriS. P.VashishthaA.SinghP.et al (2016). Algae as crucial organisms in advancing nanotechnology: a systematic review.J. Appl. Phycol.281759–1774. 10.1007/s10811-015-0715-1

128

ShuklaA. K.IravaniS. (2017). Metallic nanoparticles: green synthesis and spectroscopic characterization.Environ. Chem. Lett.15223–231. 10.1007/s10311-017-0618-2

129

ShuklaR.BansalV.ChaudharyM.BasuA.BhondeR. R.SastryM. (2005). Biocompatibility of gold nanoparticles and their endocytotic fate inside the cellular compartment: a microscopic overview.Langmuir2110644–10654. 10.1021/la0513712

130

SingaraveluG.ArockiamaryJ. S.KumarV. G.GovindarajuK. (2007). Anovel extracellular synthesis of monodisperse gold nanoparticles using marine alga, Sargassum wightii Greville.Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces5797–101. 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2007.01.010

131

SinghA. K.SenapatiD.WangS.GriffinJ.NeelyA.CandiceP.et al (2009). Gold nanorod based selective identification of Escherichia coli bacteria using two-photon Rayleigh scattering spectroscopy.ACS Nano31906–1912. 10.1021/nn9005494

132

SinghP.KimY. J.WangC.MathiyalaganR.YangD. C. (2016a). The development of a green approach for the biosynthesis of silver and gold nanoparticles by using Panax ginseng root extract, and their biological applications.Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol.441150–1157. 10.3109/21691401.2015.1011809

133

SinghP.PanditS.MokkapatiV. R. S. S.GargA.RavikumarV.MijakovicI. (2018). Gold nanoparticles in diagnostics and therapeutics for human cancer.Int. J. Mol. Sci.19:1979. 10.3390/ijms19071979

134

SinghP.SinghH.KimY. J.MathiyalaganR.WangC.YangD. C. (2016b). Extracellular synthesis of silver and gold nanoparticles by Sporosarcina koreensis DC4 and their biological applications.Enzyme Microb. Technol.8675–83. 10.1016/j.enzmictec.2016.02.005

135

SinghR. K.KurianA. G.PatelK. D.MandakhbayarN.KnowlesJ. C.KimH. W.et al (2020). Label-free fluorescent mesoporous bioglass for drug delivery, optical triple-mode imaging, and photothermal/photodynamic synergistic cancer therapy.ACS Appl. Bio Mater.20202218–2229. 10.1021/acsabm.0c00050

136

SinghR. K.PatelK. D.LeongK. W.KimH. W. (2017). Progress in nanotheranostics based on mesoporous silica nanomaterial platforms.ACS Appl. Mater Inter.910309–10337. 10.1021/acsami.6b16505

137

SivarajM.MukherjeeA.MariappanR.MariadossA. V.JeyarajM. (2018). Polyorganophosphazene stabilized gold nanoparticles for intracellular drug delivery in breast carcinoma cells.Process Biochem.72152–161. 10.1016/j.procbio.2018.06.006

138

SlocikJ. M.StoneM. O.NaikR. R. (2005). Synthesis of gold nanoparticles using multifunctional peptides.Small11048–1052. 10.1002/smll.200500172

139

SmithaS. L.PhilipD.GopchandranK. G. (2009). Green synthesis of gold nanoparticles using Cinnamomum zeylanicum leaf broth.Spectrochim. Acta Part A74735–739. 10.1016/j.saa.2009.08.007

140

SztanderaK.GorakiewiczM.Klajnert-MaculewiczB. (2019). Gold nanoparticles in cancer treatment.Mol. Pharm.161–23. 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.8b00810

141

TahirK.NazirS.LiB.KhanA. U.KhanZ. U. H.GongP. Y.et al (2015). Nerium oleander leaves extract mediated synthesis of gold nanoparticles and its antioxidant activity.Mater. Lett.156198–201. 10.1016/j.matlet.2015.05.062

142