- 1State Key Laboratory of Microbial Metabolism, School of Life Sciences and Biotechnology, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai, China

- 2State Key Laboratory of Biobased Material and Green Papermaking (LBMP), Department of Bioengineering, Qilu University of Technology, Shandong Academy of Sciences, Jinan, China

Pseudomonas chlororaphis P3 has been well-engineered as a platform organism for biologicals production due to enhanced shikimate pathway and excellent physiological and genetic characteristics. Gentisate displays high antiradical and antioxidant activities and is an important intermediate that can be used as a precursor for drugs. Herein, a plasmid-free biosynthetic pathway of gentisate was constructed by connecting the endogenous degradation pathway from 3-hydroxybenzoate in Pseudomonas for the first time. As a result, the production of gentisate reached 365 mg/L from 3-HBA via blocking gentisate conversion and enhancing the gentisate precursors supply through the overexpression of the rate-limiting step. With a close-up at the future perspectives, a series of bioactive compounds could be achieved by constructing synthetic pathways in conventional Pseudomonas to establish a cell factory.

Introduction

Growing attention to environmental problems and energy crises has inspired the development of bio-based production of valuable bioproducts over the past few decades (Choi et al., 2015; Liao et al., 2016; Noda et al., 2017). Microbial-based synthetic biology and metabolic engineering are eco-friendly approaches for producing valuable biochemicals from sustainable carbon sources. Hydroxybenzoic acids and their derivatives are widely used as additives in foods, drugs, and cosmetics for antisepsis and flavor preservation, or as a monomer to synthesize bioactive compounds (Wang et al., 2018a; Shen et al., 2020). Besides, hydroxybenzoic acids play essential roles in microbial metabolism by serving as intermediates of the degradation of the aromatic compounds and contributing to the synthesis of various valuable secondary metabolites. Therefore, it is essential to explore the metabolism of hydroxybenzoic acids in microbial hosts to synthesize new natural products and improve the methods for overproduction of valuable compounds.

Recently, Pseudomonas has received significant attention in synthetic biology due to its robustness and metabolic versatility (Belda et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2020). Genome database and tools for gene editing make it possible that Pseudomonas become a cell factory for bio-industrial application (Poblete-Castro et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2020). Pseudomonas chlororaphis P3 (P. chlororaphis P3) is one phenazine-1-carboxamide (PCN) producing biocontrol strain obtained from P. chlororaphis HT66 with multiple rounds of mutation and selection with enhanced shikimate pathway based on the isobaric tags for relative and absolute quantification (iTRAQ)-based quantitative proteomic analysis (Jin et al., 2016). Based on the efficient shikimate pathway and simple cultivation conditions, P. chlororaphis P3 has been genetically engineered for the synthesis of arbutin (Wang et al., 2018c).

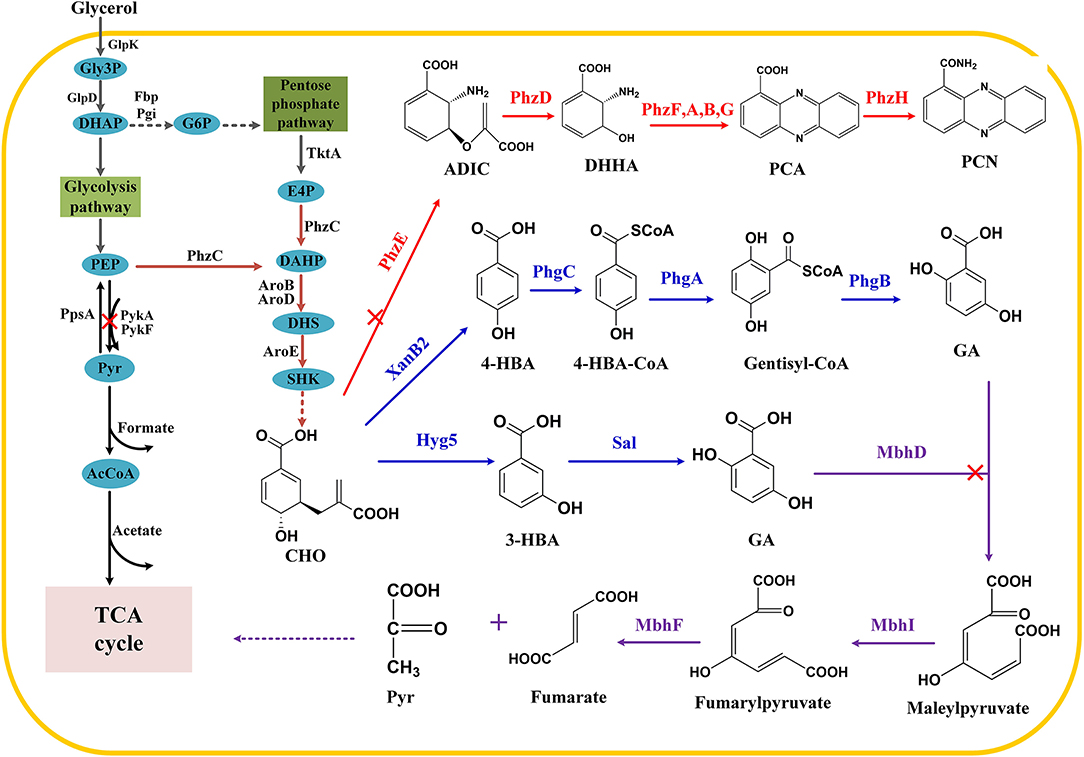

Shikimate pathway is the leading pathway for the synthesis of numerous aromatic compounds. Besides the aromatic amino acids, folic acid, ubiquinone, and phenazine antibiotics are also synthesized through the shikimate pathway (Averesch and Krömer, 2018; Wang et al., 2018b; Cao et al., 2020). There have been many researches focused on the synthesis of hydroxybenzoic acid and its derivatives, such as the construction of cell factory based on 4-hydroxybenzoic acid (4-HBA) for the synthesis of arbutin, muconic acid (MA), vanillyl alcohol, and other value-added products (Bai et al., 2016; Chen et al., 2017c; Wang et al., 2018c). In addition, salicylic acid (SA) and MA could also be synthesized by introducing isochorismate synthase in E. coli (Lin et al., 2014). Gentisate (GA) is an important intermediate with high antiradical and antioxidant activities that can be used as a precursor for drugs. According to an earlier study, plasmid-based 3-HBA expression systems were established that use antibiotics and inducers to ensure the hereditary stability of engineered strains (Kallscheuer and Marienhagen, 2018; Zhou et al., 2019), thus leaving environmental footprints (Keen and Patrick, 2013). In this context, we engineered chromosome-integrated synthetic pathways for 3-HBA and GA in P. chlororaphis P3. Exogenous 3-HBA synthetic enzyme was introduced, and then GA was biosynthesized by connecting the endogenous degradation pathway from 3-HBA. Also, we tried novel GA synthesis from 4-HBA (Figure 1). Strategies used in this research revealed Pseudomonas' versatility as a bioengineering strain, and this green microbial synthetic approach demonstrated its great potential of relieving environmental problems.

Figure 1. Construction of synthetic pathway for gentisate in P. chlororaphis P3. Gly3P, glycerol-3-phosphate; DHAP, dihydroxyacetone phosphate; GAP, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate; G6P, glucose-6-phosphate; Pyr, pyruvate; PEP, phosphoenolpyruvate; E4P, erythrose 4-phosphate; DAHP, 3-deoxy-D-arabino-heptulosonate 7-phosphate; DHS, 3-dehydroshikimate; SHK, shikimate; CHO, chorismate; 4-HBA, 4-hydroxybenzoate; 3-HBA, 3-hydroxybenzoate; ADIC, 2-amino-2-desoxyisochorismic acid; DHHA, trans-2,3-dihydro-3-hydroxyanthranilic acid; PCA, phenazine-1-carboxylic acid; PCN, phenazine-1-carboxamide. Main enzymes invloved, TktA: pyruvate synthase; PhzC DAHP synthase; Hyg5: 3-hydroxybenzoate synthase; Sal: salicylate hydroxylase; PykA PykF: pyruvate kinase; PpsA: PEP synthase; XanB2: chorismate lyase; PhzE: anthranilate synthase; PhzDFABD: phenazine synthetic protein; MhbD: gentisate 1,2-dioxygenase; MhbI: maleylacetoacetate isomerase.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial Strains, Plasmids, and Culture Conditions

All strains and plasmids constructed or used in this study are listed in the Supporting Information (Supplementary Tables 1, 2). E. coli and P. chlororaphis were cultured in Lysogeny Broth (LB) medium (Tryptone 10 g/L, Yeast extract 5 g/L, NaCl 10 g/L) during the construction of strains. King's medium B (KB) (Glycerol 18 g/L, Tryptone 20 g/L, MgSO4·7H2O 1.498 g/L, K2HPO4 0.514 g/L) was used for secondary metabolites production in P. chlororaphis. Agar was supplemented at a final concentration of 1.5% before sterilization. The medium was supplemented with the following antibiotics: 50 mg/L kanamycin and 100 mg/L ampicillin for screening of positive clones. To induce a double exchange of homologous recombination, sucrose was added to a final concentration of 15% before sterilization. P. chlororaphis was cultured at 28°C, while E. coli was cultured at 37°C. The shake flasks were filled with 60 mL medium and maintained at 28°C, 220 rpm.

P. chlororaphis strains were activated on KB agar medium and cultured overnight at 28°C. Single colonies were isolated and then inoculated to ~50 mL KB medium in a flask. The primary pre-cultures were incubated at 28°C overnight. At the beginning of fermentation, the bacterial suspension was inoculated into a 250 mL shake flask containing 60 mL KB broth to reach an initial OD600 of 0.02. Samples of 1 mL were collected every 12 h for the determination of cell growth and metabolic products. Each fermentation test was conducted in triplicate.

DNA Techniques

All primers were designed by Primer Premier 5.0 (PREMIER Biosoft, San Francisco, USA), and then synthesized by Personalbio (Shanghai, China) (Supplementary Table 3). A sequence of hyg5 from Streptomyces hygroscopicus ATCC 29253 was codon-optimized and synthesized by Genewiz (Suzhou, China). To construct plasmid for expressing hyg5 in pykA locus, the 500 bp upstream and downstream DNA fragments of pykA, Pphz promoter, and open reading frame (ORF) of hyg5 were amplified by PCR using PrimerSTAR Max DNA Polymerase. Then, the PCR products were purified with HiPure Gel Pure DNA Mini Kit (Magen, Guangzhou, China) after agarose gel electrophoresis. Next, these DNA fragments were assembled into the restriction enzyme-digested pk18mobsacB using In-Fusion Cloning Kit (TaKaRa Bio, Beijing, China). After transformation, plasmids were collected by HiPure Plasmid Micro Kit (Magen, Guangzhou, China). Gene deletion or substitution plasmids were constructed using the same method as reported previously (Wang et al., 2018b). The corresponding nucleotide sequences are presented in Supplementary Table 3.

The principle of strain construction is homologous recombination-mediated by suicide plasmids. Here, pykA deletion was taken as an example. Similar to early study (Wang et al., 2018b), plasmid pk18-ΔpykA containing pykA upstream and downstream fragments were constructed using the method mentioned above, and then transferred into S17-1 (λ pir). S17 containing pk18-ΔpykA and P3 were inoculated into LB liquid medium and then cultured overnight. To maintain the stability of plasmid, 50 mg/L Kan was added into the medium. A few milliliters of cell suspension were then centrifugated, and the bacteria were mixed with LB liquid medium. After incubation at 28°C for 1–2 h, the mixture was incubated again on a LB solid medium plate at 28 °C for 24–36 h. The mixed bacterial cells were scraped from LB plate, resuspended in 200 μL LB liquid medium, coated on a new LB plate containing 50 mg/L Kan and 100 mg/L Amp, and incubated at 28°C. A single colony was selected, diluted with LB liquid medium to a specific proportion, and then coated on a LB plate containing 15% sucrose. After 36 h of culture, the colonies were selected and cultured on LB plates containing Kan or Amp. The colonies that grow on LB (Amp) plates but not on LB (Kan) plates are positive transformants. To screen the strains, PCR was conducted using pykA-1F and pykA-2R primers. After agarose gel electrophoresis, two or three suspected mutant strains were determined and cultured overnight. Genomic DNA was extracted by HiPure Bacterial DNA Kit (Magen, Guangzhou, China) and used as the template of PCR amplification to verify pykA deletion, and no mutation occurred in homologous arms. In this way, a pykA-deleted strain was successfully constructed.

Whole-cell Transformation

BL21 (DE3) strains (i.e., BL21-Sal, BL21-PobA, and BL21-PobAM) were activated on LB plates, cultured overnight at 37°C, and then inoculated to 60 mL LB medium in shake flasks. Isopropyl-β-D–thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) was used to induce 60 mL cultures at OD600 of 0.2–0.6. After overnight incubation at 16°C, the cells were gathered by centrifugal precipitation, washed with 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH = 8.0), and resuspended in 30 mL phosphate buffer at a final OD600 of 5.0. Following the addition of 30 μg NADH and 15 mg 3-HBA, the cell suspensions were incubated at 28°C with continuous shaking at 220 rpm. All samples were collected for analysis every 6 h.

Analytical Methods

The absorbance of cell suspension at 600 nm was determined with an ultraviolet spectrophotometer to measure the number of cells. High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) method was established for determining the contents of metabolites. Samples were collected during fermentation at specific time points and then centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 5 min. Subsequently, the supernatant was filtered using nylon filters with an aperture span of 0.2 μm. The samples of 3-HBA and GA were detected using an Agilent Technologies 1,260 Infinity HPLC system with a C18 reversed-phase column at 30°C and 1 mL/min (constant flow rate). The concentrations of products were determined using an ultraviolet absorbance detector at 235 nm, and the injection volume was 20 μL. The mobile phase consisted of solvent A (methanol) and solvent B (water containing 0.1% formic acid). The separation of metabolites was carried out via gradient elution under the following conditions: 0–2 min, 5% A; 2–10 min, a linear gradient of A from 5 to 15%; 10–20 min, a linear gradient of A from 15 to 25%; 20–25 min, a linear gradient of A from 25 to 30%; and 25–35 min, 5% A.

Statistical Analysis

All results of three independent experiments were averaged and presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical differences among the means of two or more groups (p < 0.05) were determined using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Duncan's multiple range test (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). The number of cells was monitored by measuring OD600 values, and the growth curve was fitted with a sigmoidal model. Quantification of the released compounds was performed according to the standard curve calibrated using each authentic compound.

Sequence Data Analysis

DNA sequences of the genes in P. chlororaphis were retrieved from the Pseudomonas Genome Database (http://www.pseudomonas.com/). Sequence homology searching was conducted using the NCBI nucleotide BLAST server. The amino acid sequences of 3-hydroxybenzoate 6-hydroxylases and salicylate hydroxylases from other strains were obtained from GenBank. The phylogenetic tree was constructed by MEGA 7.0 using the Neighbor-Joining method.

Results

Tolerance of P. chlororaphis to 3-HBA and Gentisate

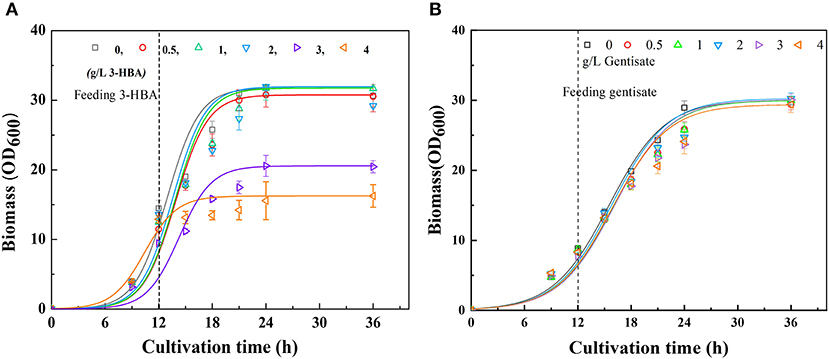

It is well-recognized that the accumulation of some metabolites, especially phenolic compounds, is highly toxic to cells (Adeboye et al., 2014). Therefore, to determine whether the excessive accumulation of 3-HBA and GA could affect cell growth, the tolerability of P3 to 3-HBA and GA were evaluated. The tolerance experiment was carried out in shake flasks to simulate the synthesis of secondary metabolites during fermentation. In consistent with the synthetic process, at the early logarithmic growth phase, different concentrations of 3-HBA and GA were supplemented into the medium at a final concentration of 0.5 to 4 g/L. After that, the cells were continuously cultured, and cell growth was monitored until the stationary phase. The results demonstrated that 3-HBA with a concentration of <2 g/L in medium showed no significant effect on cells' growth. When the concentration of 3-HBA reached 3 g/L, the growth of P3 was significantly inhibited, and cell growth was entirely blocked at a concentration of 4 g/L (Figure 2A). Although 3-HBA shows quite a toxicity to Pseudomonas, tolerance will not be a crucial factor in current research. When different concentration (0.5 to 4 g/L) of GA were supplemented to the medium, no significant affect was detected on the growth of P. chlororaphis P3 (Figure 2B). We can conclude that P. chlororaphis P3 is a good candidate for GA synthesis from 3-HBA.

Figure 2. Culture profiles of P. chlororaphis in KB medium supplemented with 0–4 g L−1 3-HBA or gentisate at 12 h. (A) Time courses of a bacterial cell growth when supplemented with 0–4 g L−1 3-HBA, (B) Time courses of a bacterial cell growth when supplemented with 0–4 g L−1 gentisate. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation of three independent experiments (n = 3).

Pathway Construction for the Synthesis of 3-HBA

To synthesize 3-HBA from glycerol in P. chlororaphis, efforts were first intensified on the upstream of shikimate pathway for accumulating chorismate. Shikimate pathway begins with the aldol condensation of metabolic intermediates (i.e., PEP and E4P) involved in the central carbon metabolism. PEP is a key central metabolite that mainly responsible for the synthesis of pyruvate catalyzed by pyruvate kinase. Therefore, weakening the conversion of PEP to pyruvate may increase the availability of PEP. As reported in E. coli, pykA, and pykF encoding pyruvate kinases, they are responsible for converting PEP to pyruvate in Pseudomonas (Meza et al., 2012). Once the two pyk genes were deleted, the flux of pyruvate to acetyl-CoA would be impeded, thus interfering with the normal growth of cells. Therefore, pykA deletion was carried out based on previous research (Wang et al., 2018c).

Considering that phenazine is the main competitive secondary metabolite in the shikimate pathway, the synthesis of PCN should be blocked to ensure chorismate's maximum availability for other pathways. The formation of 2-amino-4-deoxychorismate (ADIC) is the first step of phenazine synthesis (Li et al., 2011), and thus phzE deletion was carried out in this study. 3-HBA is synthesized from chorismate via a reaction catalyzed by chorismatase/3-hydroxybenzoate synthase. It has been reported that hyg5, a 3-HBA synthase gene originated from Streptomyces hygroscopicus was inserted into plasmids, allowing E. coli and C. glutamicum to synthesize 3-HBA (13, 14) efficiently. Consequently, hyg5 was integrated into the genome, phzAB locus under the control of native strong promoter Pphz, resulting in a derivative of P3-Hb0. As expected, P3-Hb0 lost the ability to synthesize PCN; however, 3-HBA was not accumulated in fermentation. When using 3-HBA as a sole carbon source to culture P. chlororaphis P3, a little colony growth was observed, indicating that 3-HBA can be degraded in P. chlororaphis. According to previous reports, there are two major pathways related to the aerobic degradation of 3-HBA: one is the conversion of 3-HBA to 3,4-dihydroxybenzoic acid (protocatechuic acid) catalyzed by 3-hydroxybenzoate 4-hydroxylase, and the product ultimately enters the protocatechuic acid pathway (Michalover et al., 1973); the other is the para-hydroxylation of 3-hydroxybenzoate to produce GA via 3-hydroxybenzoate 6-hydroxylase, and it enters the GA pathway (Groseclose et al., 1973). Since GA pathway is more common in Pseudomonas, sequence alignment was conducted using 3-hydroxybenzoate 6-hydroxylase as a template. Thus, Sal, which is annotated as salicylate hydroxylase in the database, has been identified and postulated to catalyze the degradation of 3-HBA, and then sal deletion was performed in P3-Hb0, resulting in a derivative of P3-Hb1.

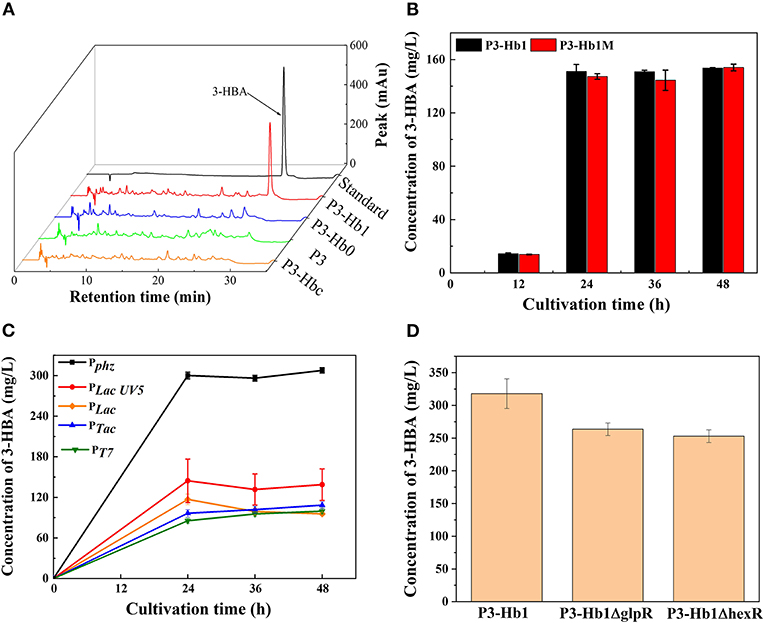

When culturing P3-Hb0 and P3-Hb1 in shake flasks, the products were analyzed by HPLC. As shown in Figure 3, a new peak appeared in P3-Hb1 samples similar to the standard, while no chromatographic peak was found in P3-Hb0 samples over the corresponding time points. To verify the accumulation of 3-HBA, P3-Hb1 sample was further analyzed with ultra-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS/MS). The mass spectrometer was operated in the negative ESI mode, and data acquisition was performed in selected-ion-monitoring (SIM) mode. The peak was observed at ~25.6 min, with the m/z of 137.02, which corresponds to the molecular ion of 3-HBA (Supplementary Figure 1). Collectively, the synthetic pathway of 3-HBA in P3 was successfully established, and the amount of 3-HBA produced from P3-Hb1 was 151 mg/L after 48 h of cultivation.

Figure 3. Culture profiles of various 3-HBA-producing transformants. (A) HPLC profiles of various transformants; (B) The amount of produced 3-HBA in the cultures of P3-Hb1 and P3-Hb1M; (C) The amount of produced 3-HBA in the cultures when using different promoter to express hyg5; (D) The amount of produced 3-HBA in the cultures of P3-Hb1ΔglpR and P3-Hb1ΔhexR. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation of three independent experiments (n = 3).

Improvement of a Rate-Limiting Step in 3-HBA Production on Multiple Levels

After the successful construction of 3-HBA synthetic pathway, the next step was to enhance the production of 3-HBA. P3-Hb1 produced 151 mg/L of 3-HBA, which was much less than the PCN quantity produced by P3. The supply of precursor chorismate increases the synthesis of 3-HBA, thus it is considered a rate-limiting step that catalyzes chorismate to 3-HBA. To improve the rate-limiting step, we attempted to optimize the expression of genes involved in 3-HBA production at multiple levels.

Firstly, cuv10, a candidate 3-hydroxybenzoate synthase gene from S. hygroscopicus was used as a substitute for hyg5. P3-Hbc was constructed by inserting cuv10 into its genome under the control of promoter Pphz for a replacement. As shown in Figure 3A, the chromatographic peak of 3-HBA was not observed in P3-Hbc sample, indicating that cuv10-carrying P3-Hb0 cannot efficiently produce 3-HBA.

Secondly, an additional initiator codon sequence was inserted to the upstream region of ORF, hyg5 possessed double initiator codon in P3-Hb1m consequently. According to a report that the substitution of the start codon to regulate the expression of some genes is one useful strategy in synthetic biology (Chen et al., 2017a). Based on this, we adopted the similar approach to promote the binding of ribosome and mRNA and ultimately increase translation levels. P3-Hb1m was fermented while P3-Hb1 as a control group and then sampled for HPLC analysis. Figure 3B shows the amounts of 3-HBA produced during the cultivation. There was no significant difference in the production levels of 3-HBA between these two strains, and both of them achieved a maximum yield of 151 mg/L after 48 h of cultivation.

Thirdly, hyg5 was expressed under the control of different promoters. Pphz is a native strong promoter located at the upstream of the phenazine gene cluster, which can effectively regulate the transcription levels of the whole gene cluster. Four foreign constitutive promoters (i.e., PLac, PLacUV5, PTac and PT7) were cloned from E. coli, a native promoter (i.e., Pphz) was cloned from P. chlororaphis, then linked to hyg5 and inserted into the genome of P3-Hb1. For construction of PT7-based expression derivative, T7 RNA polymerase was inserted into the phzE locus under the control of native promoter. A total of five derivatives (i.e., P3-Hhb1, P3-Hhb2, P3-Hhb3, P3-Hhb4, and P3-Hhb5) were fermented, and the amount of 3-HBA produced in each derivative is shown in Figure 3C. It was found that Pphz-induced overexpression of hyg5 could considerably enhance the production of 3-HBA, with a maximum level of 300 mg/L, which nearly doubled compared to P3-Hb1. However, other promoters did not exhibit a positive effect on the improvement of 3-HBA production.

Lastly, global metabolic regulation was concerned. It has been reported that the deletion of glpR in P. putida could eliminate its growth lag-phase and increase polyhydroxyalkanoates accumulation when cultured on glycerol (Escapa et al., 2013). Besides, the transcriptional factor HexR regulates the central carbohydrate metabolism globally. According to previous findings, pyruvate kinase is regulated by HexR (Leyn et al., 2011). Thus, glpR and hexR were deleted in P3-Hhb1, individually. Contrary to our expectation, the amount of 3-HBA decreased slightly (Figure 3D). We assumed that GlpR displays positive action on central carbohydrate metabolism in P. chlororaphis, once deleted, the precusor of PEP is decreased for shikimate pathway, more evidence should be revealed.

Biosynthesis of Gentisate From 3-HBA

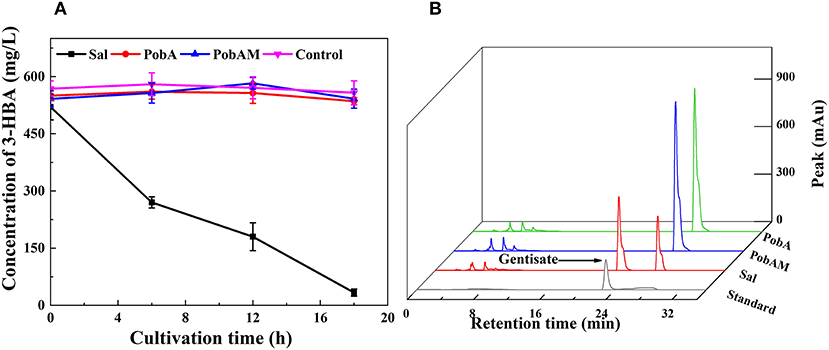

As the efficient production of 3-HBA was achieved, we attempted to construct the pathway for GA from 3-HBA. During the 3-HBA synthetic pathway construction, Sal was found to catalyze the degradation of 3-HBA by adding a hydroxyl group to the benzene ring. Therefore, different hydroxybenzoic acid monooxygenases were screened for catalyzing 3-HBA to dihydroxybenzoic acid derivatives. According to a previous report, p-hydroxybenzoate hydroxylase encoded by pobA from P. aeruginosa was mutated into Y385F/T294A PobA (hereinafter referred to as PobAM). PobAM displayed a high catalytic activity toward 3,4-dihydroxybenzoic acid and catalyzed the formation of gallic acid (Chen et al., 2017b). Thus, the hydroxybenzoic acid monooxygenase genes (i.e., sal, pobA and pobAM) were linked to expression vector pET28a(+) and subsequently transferred into BL21(DE3). 3-HBA was added to the cell suspension culture with a final concentration of 500 mg/L, and the concentration changes of 3-HBA in the four groups are presented in Figure 4A. After 12 h of incubation, most of 3-HBA was catalyzed by Sal, while the concentration of 3-HBA did not differ significantly between PobA and PobAM groups. The chromatographic peaks of 3-HBA in the four groups at 12 h are shown in Figure 4B. Results demonstrated that a new substance appeared when catalyzing 3-HBA by Sal. In comparison with the HPLC profile of various hydroxybenzoic acids, it can be speculated that the new substance is GA. Furthermore, UPLC-MS/MS analysis also supported the speculation that Sal can catalyze the conversion of 3-HBA to GA (Supplementary Figure 2).

Figure 4. 3-HBA consuming profiles by different monooxygenase. (A) Time courses of 3-HBA consuming, (B) HPLC profiles of various transformants for 3-HBA and gentisata.

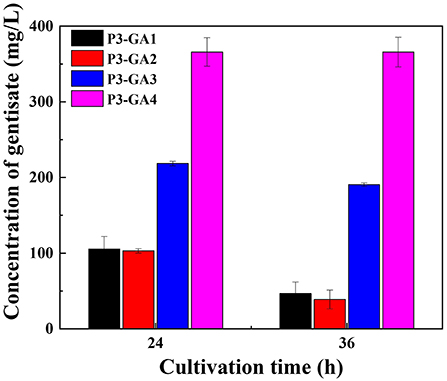

The degradation pathway of 3-HBA in Pseudomonas has also been clarified. As reported earlier, 3-HBA was converted to GA, and then maleylpyruvate was formed by GA 1,2-dioxygenase (MhbD) mediated ring-cleavage reaction. The final products of the above reactions are pyruvate and fumarate, which ultimately enter the TCA cycle (Lin et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2020; Figure 1). The genes encoding these enzymes are all located within a single gene cluster, involving a 3-HBA transporter (Xu et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2020). Thus, a pathway for GA accumulation was constructed by deleting mhbD1 in P3-Hb0. Notably, the chromatographic peak of GA was observed, implying that GA was accumulated successfully in P3-GA1. Besides, the concentration of GA in fermentation broth reached a maximum of 105 mg/L after cultivation for 24 h and then decreased to 47 mg/L at 36 h.

Improvement of Gentisate Production

As mentioned above, GA has accumulated in P. chlororaphis P3 temporarily, the concentrations of GA were decreased during fermentation, suggesting another degradation pathway for GA in P. chlororaphis. After database searching, a gene was identified and named as mhbD2, due to its position on the antisense strand. It has been recorded to encode a GA 1,2-dioxygenase, according to the Pseudomonas Genome Database. When deleted mhbD2, the degradation of GA was similar to P3-GA1 (Figure 5).

Increasing the availability of precursors to enhance the production of GA may be an option to offset the degradation. Overexpression of hyg5 was conducted in P3-Ga0 under the control of Pphz promoter, resulting in P3-GA3. To our expectation, the amount of GA was doubled to 218 mg/L at 24 h of fermentation. It was noteworthy that the yield of GA at 36 h was 190 mg/L, and the degradation of GA from 24 to 36 h was retarded with its improved production rates. Following hyg5 overexpression, hmgA that encodes homogentisate 1,2-dioxygenase was inactived, since the structure of homogentisate is relatively similar to GA. After deleting hmgA in P3-GA3, the amount of GA reached 365 mg/L at 24 h of fermentation, which was 67% higher than P3-GA3. There was no significant difference in the amount of GA between 24 and 36 h, indicating that GA is no longer degraded during fermentation process (Figure 5). Therefore, a stable and effective GA biosynthetic pathway was successfully established in the present study, and 365 mg/L GA was produced in P3-GA4.

Biosynthesis of Gentisate From 4-HBA

4-HBA has recently emerged as a versatile intermediate for several value-added bioproducts, such as muconic acid, arbutin, gastrodin, xiamenmycin, and vanillyl alcohol using 4-HBA as the starting feedstock (Wang et al., 2018a,c). A novel reaction in the conversion of 4-HBA to GA was reported (Zhao et al., 2018), in which three genes (phgABC) catalyze the transformation of 4-HBA to GA via a route involving CoA thioester formation, hydroxylation concomitant with a 1, 2-shift of the acetyl CoA moiety and thioester hydrolysis (Figure 1). Using our earlier screened XanB2 for 4-HBA synthesis, we integrated Pphz-xanB2 on pykA locus, with phzE, pobA, mhbD1 and hmgA deleted. Then, phgA-phgB-phgC were integrated on phzAB locus under the control of native strong promoter Pphz, yielding one GA derivative GA-4HBA. When fermented in KB medium, unfortunately, no new peak appeared and no siginificantly 4-HBA reduced.

Discussion

GA is an important chemical with high industrial values, together with other hydroxybenzoic acids, including salicylic acid, 4-HBA, 3-HBA, and so on. There have been many reports about hydroxybenzoic acid production and their derivatives in various microbial systems (Wang et al., 2018a). Although antibiotic compounds are concerned as 'emerging contaminants' (Keen and Patrick, 2013), the biosynthesis of GA independent of inducers and antibiotics has not been achieved previously. In this work, we engineered a chromosome-integrated synthetic pathway for GA production from 3-HBA in Pseudomonas.

3-HBA usually serves as an important platform chemical in microorganisms, in which its synthetic pathway can be found and reconstructed. We focused on the enhanced shikimate pathway in P. chlororaphis P3, the leading pathway for aromatic compound synthesis. Apart from introducing exogenous 3-hydroxybenzoate synthase to catalyzes 3-HBA from chorismate, another approach was to prevent the degradation of the products and their potential precursors in Pseudomonas. To enhance the synthesis of 3-deoxy-D-arabino-heptulosonate 7-phosphate (DAHP), pykA deletion was conducted in P3. Afterwards, phzE that catalyzes chorismate to phenazines and sal that degrades 3-HBA were knocked out, individually, resulting in a chassis strain for 3-HBA synthesis from glycerol (Figure 1).

To enhance the production of 3-HBA and GA, multiple strategies were employed. Several reports have described that the feedback inhibition in the shikimate pathway may impede the production of target products (Kikuchi et al., 1997; Juminaga et al., 2012). However, on the basis of our previous findings, we speculated that such bottleneck mainly occurs during the conversion of chorismate to 3-HBA in P. chlororaphis (Wang et al., 2018b). Few 3-hydroxybenzoate synthase genes were reported, and the enzymes with higher activity than Hyg5 are not available for a replacement. According to reports, Cuv10 exhibits maximum activity at 26°C (pH 6.5), the culture conditions of P. chlororaphis may not meet the enzymatic properties of Cuv 10. Meanwhile, cuv10 is a part of a native polyketide synthase gene, and it is probably non-functional as chorismatase in Pseudomonas (Jiang et al., 2013).

Moreover, the enhancement of the start codon did not upregulate the activity of hyg5 The overexpression of hyg5 under the control of native strong promoter Pphz significantly upregulated its expression levels, which in turn led to a double increase (300 mg/L) in 3-HBA production (Figure 3C). After that, glpR and hexR (encoding transcriptional regulator) were deleted to optimize metabolic regulation. The results demonstrated that the metabolic flux to shikimate pathway has been improved in P. chlororaphis P3, and the deletion of glpR and hexR might cause an imbalance in primary metabolism and energy flux, resulting in a negative effect on the production of 3-HBA (Figure 3D). Thus, the highest titer of 3-HBA in P3-Hhb1 was 300 mg/L. The reaction of Hyg5 undergoes an intramolecular arene oxide mechanism, starts with surmounting a high energy barrier (Dong and Liu, 2017), thereby resulting in its low level of activity.

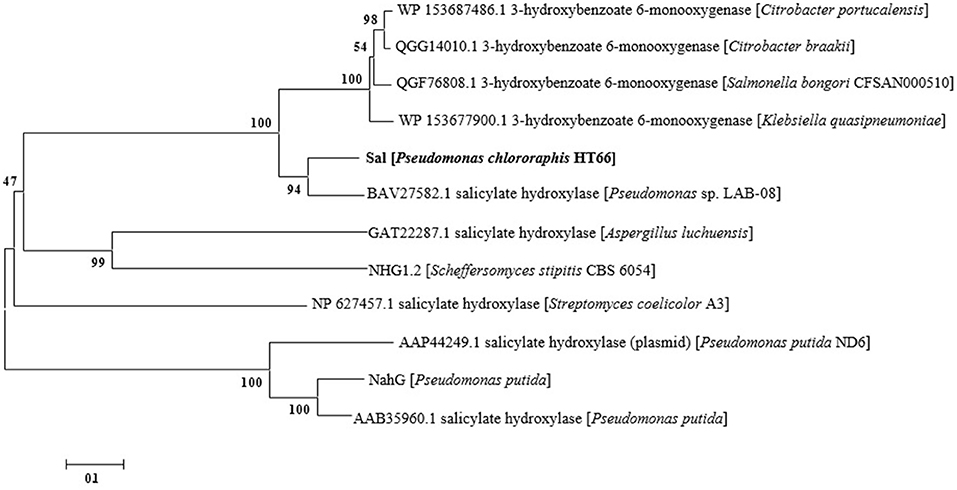

Based on the whole-cell catalysis experiment of 3-HBA, we identified that endogenous Sal catalyzed the conversion of 3-HBA to GA with high efficiency, which displayed the characteristics of 3-hydroxybenzoate 6-hydroxylases. As shown in Figure 6, a phylogenetic tree was constructed with representative 3-hydroxybenzoate 6-hydroxylases and salicylate hydroxylases from other strains (Chen et al., 2018). As shown, Sal reveals as one of these two groups, suggesting that Sal may display unselective substrate adaptability and dual catalytic activity (Fang and Zhou, 2014). Both salicylate hydroxylase and 3-hydroxybenzoate 6-hydroxylases belong to the same family of flavin-dependent monooxygenases (Yang et al., 2011; Huijbers et al., 2014), with high sequence homology between them.

Figure 6. Phylogenetic tree of of 3-hydroxybenzoate 6-hydroxylase, salicylate hydroxylase and Sal. The ruler at the bottom of figure indicates the horizontal distance equal to 10% sequence divergence.

Upon assessing the production of GA, no 3-HBA was found in the samples, indicating that endogenous Sal catalyzed 3-HBA effectively. As mentioned above, the maximum amount of GA was achieved simultaneously (24 h of cultivation) as 3-HBA. However, the net conversion rate of 3-HBA to GA was only 62.2% (the mole ratio) at 24 h without residual 3-HBA, which was much lower than the theoretical conversion rate, indicating that a third of GA was degraded. To eliminate the degradation caused by spontaneous oxidation, GA was added to KB medium and incubated at 28°C for two days. No significant change was detected in the culture, confirming that GA is relatively stable in the culture (Supplementary Figure 3).

GA 1,2-dioxygenase detected in other Pseudomonas shared a high homology level with MhbD1. There are few reports of other GA degradation genes. In this study, gene mhbD2 was identified. Sequence alignment and analysis revealed that mhbD2 was not associated with the synthesis or degradation of GA, and it probably encoded a member of fumarylacetoacetate hydrolase family protein. Thus, we attempted to enhance the carbon flux from chorismate to GA by overexpressing hyg5. Consequently, the maximum amount of GA produced was doubled, and the degradation was partially offset. Interestingly, when hmgA was deleted, the production of GA was improved entirely. It has not been reported that homogentisate 1,2-dioxygenase catalyzes GA previously, but it does indeed exist in Pseudomonas. Our results suggest that microbial catabolism is not only composed of one single pathway and contains an interrelated metabolic network. The unselective substrate adaptability of Sal and HmgA reflects the versatile metabolism of Pseudomonas, indicating that our platform strain P3 has a great potential to synthesize valuable chemicals via metabolic engineering. Unexpected, when phgABC were expressed for synthesis GA from 4-HBA based on NIH shift, no significant GA was accumulated. For the lower specific activity of PhgC against 4-HBA (Zhao et al., 2018), the higher concentration of 4-HBA may inhibit the expression of PhgC.

Various pathways could be linked to the shikimate pathway. At present, we have synthesized versatile platform compound GA and 3-HBA from simple carbon sources successfully, and many other GA-based value-added derivatives could be synthesized in the near future. Pathways can be designed to produce gallic acid via hydroxylation of 3-HBA and protocatechuic (Chen et al., 2017b). According to a report, industrially valuable maleate production was attained by extending chorismate and GA pathways (Noda et al., 2017). Besides, the hydrolysis of chorismate to 3-HBA involves the synthesis of macrocyclic polyketides, which has attracted great interests in treating metastatic and inflammatory diseases (Andexer et al., 2011). Therefore, connecting the shikimate pathway and other pathways with hydroxybenzoate acid as a node may become a powerful strategy for producing valuable bioproducts, including new to nature products.

In conclusion, chromosome-integrated synthetic pathway for GA from 3-HBA were constructed in Pseudomonas for the first time based on the enhanced shikimate pathway in P3 strain. The biosynthetic route of GA was constructed by connecting the endogenous degradation pathway and 3-HBA synthetic pathway. This study provides new insights into the possibility of using Pseudomonas to synthesize valuable compounds from renewable feedstocks, with a more environmentally responsible, eco-friendly strategy.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary Material.

Author Contributions

SW and XZ conceived and designed the experiments. SW performed experiments, analyzed the experimental data, and drafted the manuscript. CF, KL, and JC assisted in experimental work and manuscript writing. HH and WW contributed reagents & materials. XZ revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to the final paper.

Funding

This work was financed by the National Key Science Research Projects (Grant No. 2019YFA09004302) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 31670033).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to the Instrumental Analysis Center of Shanghai Jiao Tong University for their skillful technical assistance in UPLC-Q/TOF MS analysis.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fbioe.2020.622226/full#supplementary-material

References

Adeboye, P. T., Bettiga, M., and Olsson, L. (2014). The chemical nature of phenolic compounds determines their toxicity and induces distinct physiological responses in Saccharomyces cerevisiae in lignocellulose hydrolysates. AMB Express 4:46. doi: 10.1186/s13568-014-0046-7

Andexer, J. N., Kendrew, S. G., Nur-E-Alam, M., Lazos, O., Foster, T. A., Zimmermann, A. S., et al. (2011). Biosynthesis of the immunosuppressants FK506, FK520, and rapamycin involves a previously undescribed family of enzymes acting on chorismate. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.108, 4776–4781. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1015773108

Averesch, N. J. H., and Krömer, J. O. (2018). Metabolic engineering of the shikimate pathway for production of aromatics and derived compounds-present and future strain construction strategies. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 6:32. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2018.00032

Bai, Y. F., Yin, H., Bi, H. P., Zhuang, Y. B., Liu, T., and Ma, Y. H. (2016). De novo biosynthesis of Gastrodin in Escherichia coli. Metab. Eng. 35, 138–147. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2016.01.002

Belda, E., Van Heck, R. G. A., Lopez-Sanchez, M. J., Cruveiller, S., Barbe, V., Fraser, C., et al. (2016). The revisited genome of Pseudomonas putida KT2440 enlightens its value as a robust metabolic chassis. Environ. Microbiol. 18, 3403–3424. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.13230

Cao, M., Gao, M., Suástegui, M., Mei, Y., and Shao, Z. (2020). Building microbial factories for the production of aromatic amino acid pathway derivatives: From commodity chemicals to plant-sourced natural products. Metab. Eng. 58, 94–132. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2019.08.008

Chen, X., Tang, H. Z., Liu, Y. D., Xu, P., Xue, Y., Lin, K. F., et al. (2018). Purification and initial characterization of 3-hydroxybenzoate 6-hydroxylase from a halophilic martelella strain AD-3. Front. Microbiol. 9:1335. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01335

Chen, Z., Huang, J. H., Wu, Y., Wu, W. J., Zhang, Y., and Liu, D. H. (2017a). Metabolic engineering of Corynebacterium glutamicum for the production of 3-hydroxypropionic acid from glucose and xylose. Metab. Eng. 39, 151–158. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2016.11.009

Chen, Z. Y., Shen, X. L., Wang, J., Wang, J., Yuan, Q. P., and Yan, Y. J. (2017b). Rational engineering of p-hydroxybenzoate hydroxylase to enable efficient gallic acid synthesis via a novel artificial biosynthetic pathway. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 114, 2571–2580. doi: 10.1002/bit.26364

Chen, Z. Y., Shen, X. L., Wang, J., Wang, J., Zhang, R. H., Rey, J. F., et al. (2017c). Establishing an artificial pathway for de novo biosynthesis of vanillyl alcohol in Escherichia coli. ACS Synth. Biol. 6, 1784–1792. doi: 10.1021/acssynbio.7b00129

Choi, S., Song, C. W., Shin, J. H., and Lee, S. Y. (2015). Biorefineries for the production of top building block chemicals and their derivatives. Metab. Eng. 28, 223–239. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2014.12.007

Dong, L. H., and Liu, Y. J. (2017). Comparative studies of the catalytic mechanisms of two chorismatases: CH-fkbo and CH-Hyg5. Proteins 85, 1146–1158. doi: 10.1002/prot.25279

Escapa, I. F., Del Cerro, C., Garcia, J. L., and Prieto, M. A. (2013). The role of GlpR repressor in Pseudomonas putida KT2440 growth and PHA production from glycerol. Environ. Microbiol. 15, 93–110. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2012.02790.x

Fang, T., and Zhou, N.-Y. (2014). Purification and characterization of salicylate 5-hydroxylase, a three-component monooxygenase from Ralstonia sp. strain U2. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 98, 671–679. doi: 10.1007/s00253-013-4914-x

Groseclose, E. E., Ribbons, D. W., and Hughes, H. (1973). 3-hydroxybenzoate 6-hydroxylase from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 55, 897–903. doi: 10.1016/0006-291X(73)91228-X

Huijbers, M. M. E., Montersino, S., Westphal, A. H., Tischler, D., and Van Berkel, W. J. H. (2014). Flavin dependent monooxygenases. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 544, 2–17. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2013.12.005

Jiang, Y. H., Wang, H. X., Lu, C. H., Ding, Y. J., Li, Y. Y., and Shen, Y. M. (2013). Identification and characterization of the cuevaene A biosynthetic gene cluster in streptomyces sp. LZ35. Chembiochem 14, 1468–1475. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201300316

Jin, X. J., Peng, H. S., Hu, H. B., Huang, X. Q., Wang, W., and Zhang, X. H. (2016). iTRAQ-based quantitative proteomic analysis reveals potential factors associated with the enhancement of phenazine-1-carboxamide production in Pseudomonas chlororaphis P3. Sci. Rep. 6:27393. doi: 10.1038/srep27393

Juminaga, D., Baidoo, E. E. K., Redding-Johanson, A. M., Batth, T. S., Burd, H., Mukhopadhyay, A., et al. (2012). Modular engineering of L-tyrosine production in Escherichia coli. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78, 89–98. doi: 10.1128/AEM.06017-11

Kallscheuer, N., and Marienhagen, J. (2018). Corynebacterium glutamicum as platform for the production of hydroxybenzoic acids. Microb. Cell Fact. 17:70. doi: 10.1186/s12934-018-0923-x

Keen, P. L., and Patrick, D. M. (2013). Tracking change: a look at the ecological footprint of antibiotics and antimicrobial resistance. Antibiotics 2, 191–205. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics2020191

Kikuchi, Y., Tsujimoto, K., and Kurahashi, O. (1997). Mutational analysis of the feedback sites of phenylalanine-sensitive 3-deoxy-D-arabino-heptulosonate-7-phosphate synthase of Escherichia coli. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63, 761–762. doi: 10.1128/AEM.63.2.761-762.1997

Leyn, S. A., Li, X. Q., Zheng, Q. X., Novichkov, P. S., Reed, S., Romine, M. F., et al. (2011). Control of proteobacterial central carbon metabolism by the HexR transcriptional regulator: a case study in Shewanella oneidensis. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 35782–35794. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.267963

Li, Q. A., Mavrodi, D. V., Thomashow, L. S., Roessle, M., and Blankenfeldt, W. (2011). Ligand binding induces an ammonia channel in 2-amino-2-desoxyisochorismate (ADIC) synthase PhzE. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 18213–18221. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.183418

Liao, J. C., Mi, L., Pontrelli, S., and Luo, S. S. (2016). Fuelling the future: microbial engineering for the production of sustainable biofuels. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 14, 288–304. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2016.32

Lin, L. X., Liu, H., and Zhou, N. Y. (2010). MhbR, a LysR-type regulator involved in 3-hydroxybenzoate catabolism via gentisate in Klebsiella pneumoniae M5a1. Microbiol. Res. 165, 66–74. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2008.08.001

Lin, Y. H., Sun, X. X., Yuan, Q. P., and Yan, Y. J. (2014). Extending shikimate pathway for the production of muconic acid and its precursor salicylic acid in Escherichia coli. Metab. Eng. 23, 62–69. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2014.02.009

Meza, E., Becker, J., Bolivar, F., Gosset, G., and Wittmann, C. (2012). Consequences of phosphoenolpyruvate: sugar phosphotranferase system and pyruvate kinase isozymes inactivation in central carbon metabolism flux distribution in Escherichia coli. Microb. Cell Fact. 11:127. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-11-127

Michalover, J. L., Ribbons, D. W., and Hughes, H. (1973). 3-Hydroxybenzoate 4-hydroxylase from Pseudomonas testosteroni. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 55, 888–896. doi: 10.1016/0006-291X(73)91227-8

Noda, S., Shirai, T., Mori, Y., Oyama, S., and Kondo, A. (2017). Engineering a synthetic pathway for maleate in Escherichia coli. Nat. Commun. 8:1153. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01233-9

Poblete-Castro, I., Becker, J., Dohnt, K., Dos Santos, V. M., and Wittmann, C. (2012). Industrial biotechnology of Pseudomonas putida and related species. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 93, 2279–2290. doi: 10.1007/s00253-012-3928-0

Shen, Y., Sun, F., Zhang, L., Cheng, Y., Zhu, H., Wang, S. P., et al. (2020). Biosynthesis of depsipeptides with a 3-hydroxybenzoate moiety and selective anticancer activities involves a chorismatase. J. Biol. Chem. 295, 5509–5518. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA119.010922

Wang, S., Cui, J., and Bilal, M. (2020). Pseudomonas spp. as cell factories (MCFs) for value-added products: from rational design to industrial applications. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 40, 1232–1249. doi: 10.1080/07388551.2020.1809990

Wang, S. W., Bilal, M., Hu, H. B., Wang, W., and Zhang, X. H. (2018a). 4-Hydroxybenzoic acid-a versatile platform intermediate for value-added compounds. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 102, 3561–3571. doi: 10.1007/s00253-018-8815-x

Wang, S. W., Bilal, M., Zong, Y. N., Hu, H. B., Wang, W., and Zhang, X. H. (2018b). Development of a plasmid-free biosynthetic pathway for enhanced muconic acid production in Pseudomonas chlororaphis HT66. ACS Synth. Biol. 7, 1131–1142. doi: 10.1021/acssynbio.8b00047

Wang, S. W., Fu, C., Bilal, M., Hu, H. B., Wang, W., and Zhang, X. H. (2018c). Enhanced biosynthesis of arbutin by engineering shikimate pathway in Pseudomonas chlororaphis P3. Microb. Cell Fact. 17:174. doi: 10.1186/s12934-018-1022-8

Xu, Y., Gao, X. L., Wang, S. H., Liu, H., Williams, P. A., and Zhou, N. Y. (2012). MhbT is a specific transporter for 3-hydroxybenzoate uptake by gram-negative bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78, 6113–6120. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01511-12

Yang, Y. F., Zhang, J. J., Wang, S. H., and Zhou, N. Y. (2011). Purification and characterization of the ncgl2923 -encoded 3-hydroxybenzoate 6-hydroxylase from Corynebacterium glutamicum. J. Basic Microbiol. 50, 599–604. doi: 10.1002/jobm.201000053

Zhao, H., Xu, Y., Lin, S., Spain, J. C., and Zhou, N. Y. (2018). The molecular basis for the intramolecular migration (NIH shift) of the carboxyl group during para-hydroxybenzoate catabolism. Mol. Microbiol. 110, 411–424. doi: 10.1111/mmi.14094

Keywords: Pseudomonas chlororaphis P3, gentisate, biosynthesis, plasmid-free, bioactive compounds, cell factory

Citation: Wang S, Fu C, Liu K, Cui J, Hu H, Wang W and Zhang X (2021) Engineering a Synthetic Pathway for Gentisate in Pseudomonas Chlororaphis P3. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 8:622226. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2020.622226

Received: 28 October 2020; Accepted: 30 December 2020;

Published: 22 January 2021.

Edited by:

Jingwen Zhou, Jiangnan University, ChinaReviewed by:

Mingfeng Cao, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, United StatesDae-Hee Lee, Korea Research Institute of Bioscience and Biotechnology (KRIBB), South Korea

Copyright © 2021 Wang, Fu, Liu, Cui, Hu, Wang and Zhang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xuehong Zhang, eHVlaHpoYW5nQHNqdHUuZWR1LmNu

Songwei Wang1

Songwei Wang1 Kaiquan Liu

Kaiquan Liu Xuehong Zhang

Xuehong Zhang