- 1Department of Gastrointestinal Surgery, The Second Hospital of Dalian Medical University, Dalian, China

- 2Digestive System Disease Diagnosis and Treatment Center, The Second Hospital of Dalian Medical University, Dalian, China

- 3Ultrasound Department, The First Affiliated Hospital of Dalian Medical University, Dalian, China

- 4Department of Breast Surgery, The Second Hospital of Dalian Medical University, Dalian, China

- 5Department of Clinical Laboratory, The Second Hospital of Dalian Medical University, Dalian, China

Colorectal cancer remains among the most prevalent gastrointestinal malignancies worldwide, imposing a substantial clinical burden and highlighting the urgent need for precision and personalized treatment strategies. Conventional drug delivery approaches are limited by low selectivity, restricted bioavailability, and systemic toxicity, thereby limiting therapeutic efficacy. Antibody–drug conjugates, as advanced delivery plat-forms, have the advantages of highly specific antibody recognition, versatile cytotoxic payloads, and continuously evolving linker technologies. This combination provides novel opportunities to increase efficacy, reduce toxicity, and enable individualized precision therapy. Recent advances have demonstrated the potential of ADCs in CRC, yet challenges such as resistance, toxicity, and clinical translation persist. Multidisciplinary efforts among the pharmaceutical industry and molecular biology and clinical medicine fields will be essential to accelerate the development of more precise and personalized CRC therapies. This review summarizes the current research progress on ADCs as a treatment option for CRC, discusses innovations in delivery system design, examines the key challenges of personalization, and highlights future directions to better integrate ADCs into effective treatment paradigms.

1 Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is among the most common malignancies of the digestive system worldwide. It is the second leading cause of cancer-related mortality and ranks behind only lung and breast cancer in terms of incidence (Sung et al., 2021). Owing to the lack of specific early symptoms, most CRC patients are diagnosed at advanced stages, resulting in poor prognosis and limited therapeutic response (Wagle et al., 2025). The currently employed standard treatments are surgical resection, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, targeted agents, and immunotherapy. First-line chemotherapy drugs such as 5-fluorouracil and oxaliplatin are hindered by drug resistance, poor solubility and permeability, limited bioavailability, low specificity, and severe systemic side effects (Jeng et al., 2018). Radiotherapy can shrink tumours and relieve symptoms through precise localization, but tissue-specific sensitivity to radiation and adverse effects such as radiation enteritis remain limiting factors (Tan et al., 2022; Shi et al., 2023). Targeted therapies (Li Q. et al., 2024) and immunotherapies (Ganesh et al., 2019) have improved selectivity. However, their clinical utility is restricted by the rapid emergence of resistance mutations, the low response rate of “immune-cold” tumours, and immune-related toxicity.

CRC treatment strategies are strongly stage dependent; however, even patients with the same stage and treatment regimen show wide variability in survival outcomes. This discrepancy is primarily attributed to the biological heterogeneity of CRC, which manifests as profound molecular and spatiotemporal heterogeneity (Linnekamp et al., 2015; Jones et al., 2017; Suzuki et al., 2017). On the basis of gene expression profiling, consensus molecular subtypes (CMS1–4) have been defined, each of which exhibits distinct biological features and clinical behaviours (Guinney et al., 2015). This classification highlights CRC not as a single disease entity but as a spectrum of molecularly defined subgroups with divergent therapeutic sensitivities—posing fundamental challenges to the “one-size-fits-all” treatment paradigm. Spatiotemporal heterogeneity further influences therapeutic response and the development of treatment resistance (Marusyk et al., 2020). In parallel, the clinical demand for toxicity control underscores the necessity of shifting from systemic high-dose exposure to targeted delivery strategies (Han et al., 2024). Together, molecular heterogeneity, resistance, and toxicity management imperatives are driving the transition from uniform chemotherapy to highly personalized and targeted drug-delivery approaches. Against this backdrop, next-generation drug delivery systems—such as antibody–drug conjugates (ADCs)—offer promising solutions by enabling the selective targeting and localized release of potent cytotoxic agents (Markides et al., 2024).

ADCs, often described as “biomissiles” or “magic bullets,” are distinguished by their precision in drug delivery. The concept of “magic bullets” was originally proposed by the German immunologist Paul Ehrlich (Strebhardt and Ullrich, 2008), who envisioned agents that could directly reach their intended cellular targets without harming normal tissues. Over the past decade, advances in monoclonal antibody (mAb) engineering, antigen selection, linker chemistry, and payload design have led to substantial progress in ADC development (Fu et al., 2022; Tsuchikama et al., 2024). ADCs covalently couple mAbs with cytotoxic drugs through chemical linkers, combining the high specificity of antibody targeting with the potent tumour-killing capacity of small-molecule payloads (Tarantino et al., 2022). This dual advantage has established ADCs as a central focus in oncology drug development. As of August 2025, 17 ADCs have received regulatory approval worldwide (Table 1), representing a milestone in cancer therapeutics. Nevertheless, major challenges persist, including complex pharmacokinetics, toxicity, and the emergence of resistance. This review aims to discuss the development of ADCs for the treatment of CRC and explore how advanced delivery strategies may help overcome the barriers to personalized CRC therapy.

2 ADC as an advanced drug delivery system

2.1 Composition and mechanism of action

An ADC is composed of three fundamental components: an antibody, a cytotoxic payload, and a linker (Figure 1). The antibody specifically binds to target antigens expressed on the surface of tumour cells and is internalized through clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Following internalization, the plasma membrane invaginates to form early endosomes, which subsequently mature into late endosomes and fuse with lysosomes, where proteolytic degradation occurs. This process results in the release of the cytotoxic payload, which exerts its effect by inducing DNA damage or disrupting microtubules, ultimately triggering apoptosis or cell death in tumour cells. In this way, ADCs achieve selective and potent antitumour activity by combining targeted recognition with efficient intracellular drug delivery.

Figure 1. Structure and key properties of antibody–drug conjugates (ADCs). ADC comprises three essential components: a monoclonal antibody, a cytotoxic payload, and a linker.

In the early stages of ADC development, murine-derived antibodies were predominantly used. However, murine antibodies can act as antigens to trigger strong immune responses, leading to the activation, proliferation, and differentiation of immune cells, which often resulted in severe immune-related toxicity and contributed to the high failure rate of early ADCs (Hock et al., 2015; Kroemer et al., 2022). With the advent of recombinant technologies, chimeric and humanized antibodies progressively replaced murine antibodies, thereby substantially reducing immunogenicity (Abdollahpour-Alitappeh et al., 2019; Dyson et al., 2020). Currently, most ADCs are constructed using immunoglobulin G (IgG), the predominant immunoglobulin in human serum. IgG consists of four subclasses—IgG1, IgG2, IgG3, and IgG4 (Fu et al., 2022). Subtle structural differences among these subclasses can influence the solubility and half-life of monoclonal antibodies, as well as their binding affinities to various Fc gamma receptors expressed on immune effector cells (Sawant et al., 2020; Yu et al., 2020). Among these, IgG1 is the most abundant in circulation and has a relatively long serum half-life (approximately 21 days), as well as superior binding efficiency to Fc gamma receptors (Han et al., 2019). Importantly, IgG1 can elicit effector mechanisms such as antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC), antibody-dependent cellular phagocytosis (ADCP), and complement-dependent cytotoxicity (CDC) (Natsume et al., 2009), making it the preferred subclass for ADC construction. The recombinant monoclonal antibody confers high specificity towards tumour-associated antigens, enabling the selective delivery of cytotoxic payloads to tumour sites—a critical initial step for ADCs to exert their antitumour effects (Dyson et al., 2020). The efficiency of ADC internalization also dictates therapeutic efficacy, which largely depends on the binding affinity between the antibody and its target antigen on the tumour cell surface. While stronger binding affinity may, in theory, accelerate internalization (Xu, 2015), the so-called “binding site barrier” in solid tumours can restrict tissue penetration (Tsumura et al., 2018; Singh et al., 2020). Therefore, an ADC monoclonal antibody should meet six criteria: high target specificity, strong binding affinity, low immunogenicity, minimal cross-reactivity, efficient internalization, and a prolonged plasma half-life (Khongorzul et al., 2020).

In ADCs, the cytotoxic payload is covalently conjugated to the antibody through a linker. An ideal linker should remain highly stable in plasma circulation but be readily cleaved upon internalization into tumour cells. Such dual properties are critical: maintaining stability during circulation prevents premature degradation and systemic release of the payload that can damage healthy tissues, while efficient cleavage ensures that the payload is released within the lysosome of the target cell (Tang et al., 2019). Linkers are generally categorized as either cleavable or noncleavable. Noncleavable linkers primarily include thioethers and maleimidocaproyl moieties (Sheyi et al., 2022). Cleavable linkers can be further divided into chemically cleavable (e.g., hydrazones and disulfides) and enzymatically cleavable linkers (e.g., glucuronides and peptides) (Bargh et al., 2019). Within the cleavable category, the acid sensitivity (pH-responsive), enzyme sensitivity, or glutathione sensitivity of linkers may be exploited, depending on their structural features (Tang et al., 2019; Su et al., 2021). Cleavable linkers are intended to respond to the unique conditions of the tumour microenvironment, thereby facilitating controlled release of the payload. In contrast, noncleavable linkers remain inert under common chemical or enzymatic conditions, conferring improved plasma stability and minimizing off-target toxicity (Kovtun et al., 2006; Oflazoglu et al., 2008).

The cytotoxic payload represents the active component of an ADC, exerting its cytotoxic effects after internalization, and is typically a small-molecule drug (Jin et al., 2022). Given the limited bioavailability of ADCs—only ∼2% of the administered dose intravenously reaches the target tumour site (Beck et al., 2017)—the payload must be highly potent, with IC50 values usually in the nanomolar to picomolar range (Zhao et al., 2020). The efficacy of payload delivery depends on three principal factors: the abundance of accessible cell-surface antigens for antibody binding, the efficiency of antigen–antibody internalization, and the subsequent intracellular release of the cytotoxic drug. Currently, the most widely used payload classes include potent microtubule inhibitors, topoisomerase inhibitors, DNA-damaging agents, and immunomodulators (Diamantis and Banerji, 2016). An ideal ADC payload should combine high potency with excellent plasma stability, low immunogenicity, a small molecular weight, and a prolonged half-life (Li F. et al., 2016).

2.2 The value of innovative drug delivery strategies

2.2.1 Precision targeting to reduce off-target toxicity

One of the core values of ADCs lies in chemically linking highly specific mAbs to potent cytotoxic drugs through linkers. This design enables the precise delivery of cytotoxic agents to tumour cells by leveraging the specificity of the antibody for target antigens while minimizing off-target effects on healthy tissues. ADCs can be used to overcome the low target specificity of traditional chemotherapies, thereby increasing therapeutic efficacy while minimizing side effects. In the DESTINY-CRC01 trial, CRC patients with HER2 expression (IHC 3+ or IHC 2+/ISH+) achieved a significant objective response rate (ORR) with T-DXd, whereas no objective responses were observed in patients with low HER2 expression levels (IHC 2+/IHC 1+/ISH−) (Yoshino et al., 2023). These results indicate that in addition to precise targeting by mAbs, ADCs can also align with target expression levels to support individualized treatment strategies.

2.2.2 Smart linkers for personalized controlled release

Linker design enables responsive release triggered by tumour microenvironment (TME) conditions, such as acidic pH, enzyme activity, or reductive stress, which facilitates individualized control of release kinetics to adapt to tumour heterogeneity. Beyond classical cleavable linkers, researchers have developed smart responsive linkers that activate payload release by sensing specific TME features. For example, hypoxia-activated azobenzene linkers remain stable in normal tissues (O2 > 10%) but are cleaved in hypoxic tumour microenvironments (O2 < 1%), releasing monomethyl auristatin E (MMAE) and fully restoring ADC cytotoxicity (Xiao et al., 2024). In addition, differentiated release strategies using linker combinations have enabled temporally controlled release in dual-payload ADCs. For instance, KH815 employs a combination of irinotecan (a topoisomerase I inhibitor) and triptolide (an RNA polymerase II inhibitor). The former is rapidly released inside tumour cells via lysosomal enzyme-cleavable linkers, directly disrupting DNA replication, whereas the latter is triggered by pH-sensitive linkers in the TME to target stromal or vascular cells, achieving a “dual-hit” mode of tumour cell killing plus microenvironment remodelling (Mullard, 2025). Such innovations enable the release patterns of ADCs to be adjusted on the basis of individual tumour TME characteristics, laying the foundation for personalized therapy.

2.2.3 Payload diversification to complement biomarker-driven stratification in CRC

Traditional ADCs have primarily relied on microtubule inhibitors, topoisomerase inhibitors, or DNA-damaging agents. In CRC, patient stratification is driven mainly by biomarker-defined targets (e.g., HER2, GCC, CEACAM5) and tumour biology, whereas payload class modulates efficacy and safety within these target-positive populations—particularly in the setting of heterogeneous antigen expression and acquired resistance. Payload diversification has therefore become a core strategy for improving the therapeutic index and overcoming heterogeneity/resistance (Beck et al., 2017; Conilh et al., 2023). Table 2 summarizes representative ADC payload classes and clinical selection considerations in CRC. In addition to conventional payloads, non-traditional payloads—including immunostimulatory agents (e.g., TLR/STING agonists), RNA polymerase inhibitors (e.g., amatoxins), and apoptosis modulators (e.g., Bcl-xL inhibitors)—may help address resistance by engaging antitumour immunity or targeting tolerant/dormant tumour-cell states (Wang et al., 2025b; Grairi and Le Borgne, 2024). Dual-payload ADCs (e.g., KH815) that combine mechanistically distinct warheads are also being explored to deliver a “dual-hit” effect on core tumour vulnerabilities such as replication and transcription (Mullard, 2025). Overall, payload diversification complements target-based stratification and is driving ADCs towards greater precision and efficacy in CRC.

2.2.4 DAR regulation and pharmacokinetic optimization

The pharmacokinetic properties and overall therapeutic index of an ADC are profoundly influenced by its drug-to-antibody ratio (DAR) (Dumontet et al., 2023). The DAR defines the average number of payload molecules conjugated per antibody, and achieving an optimal balance is essential to ensure sufficient payload delivery without compromising antibody integrity (Chau et al., 2019). Early ADCs developed using conventional nonsite-specific conjugation methods typically yielded heterogeneous mixtures. Fractions with high DARs (≥4) exhibited stronger in vitro cytotoxic activity but exhibited increased hydrophobicity, resulting in accelerated clearance, shortened systemic exposure, and a narrower therapeutic window. In contrast, fractions with low DARs carried fewer payloads, leading to inadequate antitumour activity (Fu et al., 2022; Chis et al., 2024). The advent of site-specific conjugation strategies—such as engineered cysteine conjugation, enzymatic peptide ligation, and glycan-based conjugation—has enabled the generation of ADCs with homogeneous and controlled DARs, which are typically set at 2, 4, or 8 (Khongorzul et al., 2020; Samantasinghar et al., 2023; Choi et al., 2024; Li M. et al., 2024). These approaches allow precise and stoichiometric attachment at defined positions, markedly improving the homogeneity, stability, and activity of ADCs. Modern ADCs further integrate site-specific conjugation with tumour microenvironment–responsive linkers to achieve optimized pharmacokinetic profiles, maintaining stability and tolerability in systemic circulation while ensuring efficient payload release in tumour tissues, thereby broadening the therapeutic window (Drago et al., 2021).

3 ADC targets and therapeutic landscape in CRC

3.1 Clinically validated targets

3.1.1 Target: HER2

HER2, also known as ErbB2, is a member of the EGFR family (Marchiò et al., 2021); HER2 forms heterodimers with HER3 to regulate specific signalling pathways within the tumour microenvironment, including activation of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway (Díaz-Serrano et al., 2018; Miricescu et al., 2020), stimulation of the MAPK/ERK cascade through RAS activation (Su, 2018), and inhibition of GSK3β to maintain Wnt/β-catenin signalling (Liu et al., 2018; Kim Y. et al., 2023). These signalling cascades collectively govern tumour proliferation, epithelial–mesenchymal transition, metabolic reprogramming, therapeutic resistance, and metastasis (Shimozaki et al., 2024). HER2 also contributes to immune modulation. It induces the expression of cytokines such as interleukin-6, which activates the JAK/STAT pathway, leading to the upregulation of programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression and promoting cancer stem cell self-renewal (Zhang et al., 2016; Hassan and Seno, 2022). Concurrently, HER2 signalling results in the recruitment of immunosuppressive cells, including regulatory T cells (Tregs) and M2-polarized macrophages, thereby reshaping the immune microenvironment to facilitate tumour immune evasion (Jing et al., 2023; Jiang et al., 2024). HER2 is overexpressed in multiple solid tumours, including gastric cancer (Joshi and Badgwell, 2021), colorectal cancer (Suwaidan et al., 2022), and breast cancer (Oh and Bang, 2020). Importantly, HER2 has emerged as one of the most successful therapeutic targets across diverse malignancies (Arteaga et al., 2011; La Salvia et al., 2019; Xie et al., 2020).

3.1.1.1 RC48 (disitamab vedotin)

RC48 is an anti-HER2 ADC composed of a humanized anti-HER2 monoclonal antibody (hertuzumab) conjugated to the microtubule inhibitor MMAE via a cleavable linker (Yao et al., 2015; Li H. et al., 2016). It has been approved for the treatment of advanced or metastatic HER2-positive gastric cancer and urothelial carcinoma (Peng et al., 2021; Sheng et al., 2021; Hong X. et al., 2023; Zhou L. et al., 2025). Upon binding to HER2 on the cell membrane, RC48 undergoes internalization and lysosomal degradation, which may reduce the opportunity for STING to interact with HER2 and thereby facilitate activation of the cGAS–STING pathway (Wu et al., 2019; Wu X. et al., 2023). The antitumour activity of RC48 in CRC cells appears to be regulated by dual mechanisms: activation of cGAS–STING signalling enhances IFN-β secretion, promotes immune cell infiltration, and increases the cytotoxicity of tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes, whereas MMAE disrupts microtubules, leading to cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. Unlike conventional monoclonal antibodies, whose efficacy is strongly dependent on antigen expression levels, RC48 exhibits antitumour activity in CRC that appears less reliant on HER2 expression (Liu et al., 2024). This was supported clinically, as overall response rates were comparable between patients with low and high HER2 expression, and was consistent with preclinical evidence showing that RC48 activity in CRC PDX models is not correlated with HER2 expression (Wu X. et al., 2023; Sheng et al., 2024). Further mechanistic studies revealed that in the HT29 and SW480 cell lines, RC48 may induce senescence in both HER2-high and HER2-low CRC cells by upregulating CDKN1A protein expression (Wu et al., 2025). Multiple ongoing prospective clinical trials are currently evaluating the efficacy and safety of RC48 as a second-line treatment for HER2-positive advanced CRC (NCT05785325, NCT05493683, and NCT05578287).

3.1.1.2 T-DM1 (trastuzumab emtansine)

T-DM1 is generated by conjugating the high-affinity humanized anti-HER2 monoclonal antibody trastuzumab with the small-molecule microtubule inhibitor mertansine (DM1) through a maleimide methyl cyclohexanecarboxylate linker (Tarantino and Tolaney, 2022). T-DM1 retains the ADCC of trastuzumab, while its conjugated DM1 is released upon internalization and lysosomal degradation, blocking microtubule polymerization and inducing mitotic catastrophe (Barok et al., 2014). In vitro experiments confirmed that compared with cetuximab or trastuzumab, T-DM1 inhibited LS174T and HT-29 CRC cells more effectively. In a xenograft mouse model, T-DM1 combined with metformin significantly suppressed tumour growth (Chung et al., 2020). The multicentre phase II HERACLES-B trial further revealed that pertuzumab plus T-DM1 exhibited antitumour activity in HER2-positive metastatic CRC (mCRC), particularly in patients with high HER2 immunohistochemistry (IHC) scores (Sartore-Bianchi et al., 2020).

3.1.1.3 T-DXd (DS-8201a, trastuzumab deruxtecan)

T-DXd, also known as DS-8201 or trastuzumab deruxtecan, is an ADC that links the topoisomerase I inhibitor DXd to trastuzumab via a tetrapeptide-based cleavable linker. Its therapeutic efficacy in HER2-expressing or HER2-mutant tumours is attributed to several key features: the highly active topoisomerase I inhibitor payload, a stable and specific tetrapeptide-cleavable linker, a high DAR of up to 8, and a strong bystander effect (Ogitani et al., 2016; Takegawa et al., 2019). Currently, T-DXd has been approved in multiple countries for the treatment of metastatic HER2-positive breast cancer and gastric cancer (Keam, 2020).

T-DXd has demonstrated substantial clinical activity with a manageable safety profile in HER2-positive metastatic CRC, establishing it as a leading HER2-directed ADC. The DESTINY-CRC01 study, a multicentre phase II clinical trial, reported the efficacy and safety of T-DXd in patients with HER2-positive mCRC (Siena et al., 2021). The results demonstrated an ORR of 45.3%, which is particularly notable in HER2-positive mCRC patients who had progressed after at least two prior lines of therapy. The most common grade ≥3 treatment-emergent adverse events were neutropenia and anaemia, which were generally manageable (Tsurutani et al., 2020; Yoshino et al., 2023). Subsequent DESTINY-CRC02 findings further confirmed that 5.4 mg/kg is the optimal monotherapy dose of T-DXd for treating HER2-positive mCRC (Raghav et al., 2024).

3.1.1.4 SHR-A1811

SHR-A1811 is an ADC composed of trastuzumab, a cleavable linker, and a novel topoisomerase I inhibitor, SHR169265 (Zhang et al., 2025). SHR-A1811 showed promising antitumour activity in heavily pretreated, unresectable, or metastatic solid tumours (Li Z. et al., 2024; Li J. J. et al., 2025), with a low incidence and severity of interstitial lung disease. With an optimized DAR value of 6, SHR-A1811 retains strong cytotoxic activity and a favourable bystander killing effect, providing antitumour efficacy comparable to that of T-DXd while improving plasma stability in vitro. In preclinical models, SHR-A1811 demonstrated dose-dependent antitumour activity and favourable safety. The safety and efficacy of SHR-A1811 in patients with HER2-expressing or HER2-mutant advanced solid tumours were evaluated in a multicentre, dose-escalation phase I clinical trial (NCT04446260) (Yao et al., 2024). Among the 11 enrolled CRC patients, 4 (36.4%) achieved objective responses. Multiple ongoing clinical trials are being conducted to further assess the efficacy and safety of SHR-A1811 in advanced CRC patients refractory to oxaliplatin, 5-fluorouracil, and irinotecan (NCT06199973, NCT04513223, and NCT06666166).

3.1.1.5 Limitations and future directions

HER2-targeted ADCs are among the most clinically advanced ADC strategies in CRC, but the evidence base is still largely derived from single-arm phase II cohorts in highly selected HER2-positive populations. In DESTINY-CRC01, trastuzumab deruxtecan produced objective responses primarily in IHC 3+/ISH+ disease, whereas activity was markedly lower in HER2-low cohorts, highlighting the impact of assay definition and intratumoural heterogeneity on patient selection (Siena et al., 2021). DESTINY-CRC02 confirmed activity at 5.4 mg/kg with improved tolerability versus 6.4 mg/kg, yet interstitial lung disease/pneumonitis remained a clinically meaningful risk that requires proactive monitoring and standardized management (Powell et al., 2022; Raghav et al., 2024). Finally, prior experience with anti-HER2 therapy in mCRC suggests that co-alterations and heterogeneous HER2 amplification may contribute to primary or acquired resistance, supporting composite biomarker strategies and rational combinations rather than direct extrapolation from breast/gastric paradigms (Sartore-Bianchi et al., 2020). A consolidated comparison is provided in Table 3.

3.1.2 Target: HER3

HER3, also known as ErbB3, is another member of the EGFR family (Sierke et al., 1997) and is overexpressed in various solid tumours, including CRC (Campbell et al., 2010). HER3 can be phosphorylated through heterodimerization with other receptor tyrosine kinases, such as HER2(Olayioye et al., 2000; Campbell et al., 2010), thereby activating the PI3K/AKT and MAPK/ERK signalling pathways (Yarden and Sliwkowski, 2001; Baselga and Swain, 2009; Ocana et al., 2012; Rathore et al., 2025). Given its high expression in tumours and efficient internalization upon antibody binding, HER3 is considered a promising target for ADC development(Haikala and Jänne, 2021).

3.1.2.1 U3-1402 (patritumab deruxtecan)

U3-1402 is a HER3-targeted ADC composed of the fully humanized anti-HER3 monoclonal IgG1 antibody patritumab conjugated to DXd via a tetrapeptide-based linker (Hashimoto et al., 2019). The antitumour activity of U3-1402 is correlated with HER3 expression levels but is independent of Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog (KRAS) mutation status (Koganemaru et al., 2019). After internalization, U3-1402 releases DXd, which enters the nucleus and induces DNA damage, thereby exerting cytotoxic effects (Yonesaka et al., 2019). In xenograft mouse models, U3-1402 demonstrated both dose-dependent and HER3-dependent antitumour activity. Notably, U3-1402 enhanced the infiltration of innate and adaptive immune cells, increasing the sensitivity of HER3-expressing tumours to programmed death receptor 1 (PD-1) blockade (Haratani et al., 2020). Toxicological studies have also confirmed the acceptable safety profile of U3-1402. A phase II trial evaluating U3-1402 in patients with advanced or mCRC (NCT04479436) has now advanced to the second stage.

3.1.2.2 DB-1310

DB-1310 is an anti-HER3 ADC in which the humanized anti-HER3 antibody Hu3f8 is covalently conjugated to a proprietary DNA topoisomerase I inhibitor, P1021, through a cleavable linker (Li X. et al., 2024). Overall, DB-1310 demonstrated dose-dependent antitumour activity and good biosafety in preclinical studies. This unique linker–payload system increases the hydrophilicity of the ADC, thereby allowing a higher DAR of up to 8. In vitro studies have shown that DB-1310 exhibits high binding affinity for HER3, efficient internalization, and a favourable bystander effect (Li X. et al., 2025). A first-in-human phase I/IIa dose-escalation and expansion trial is currently ongoing to evaluate the safety and tolerability of DB-1310 in patients with advanced solid tumours (NCT05785741).

3.1.2.3 AMT-562

AMT-562 is generated by conjugating a novel anti-HER3 antibody (Ab562) with exatecan (Weng et al., 2023a). Preclinically, in CRC PDX models, compared with other ADCs, AMT-562 demonstrated superior tumour suppression, particularly in rectal cancer models with relatively high HER3 expression. Exatecan, a precursor of DXd, shows greater potency, greater cell permeability, less sensitivity to multidrug resistance, and a stronger bystander killing effect than DXd does (Joto et al., 1997; Weng et al., 2023b). In addition, the synergy of AMT-562 with other treatment regimens may become a new strategy for overcoming multidrug resistance. A first-in-human phase I dose-escalation trial is currently underway to evaluate the safety and tolerability of AMT-562 in patients with advanced solid tumours (NCT06199908).

3.1.2.4 Limitations and future directions

Although HER3 is broadly expressed and may increase in advanced/metastatic CRC, expression alone does not guarantee clinical tractability for an ADC. In patient cohorts, membranous HER3 expression has been reported to be substantially higher in metastatic CRC than in early-stage disease and associated with adverse outcomes in some subgroups (Capone et al., 2023), providing a biologic rationale for targeting. However, the most mature clinical experience with patritumab deruxtecan (HER3-DXd) comes from non-CRC settings; for example, a multicenter phase I/II trial in metastatic breast cancer showed durable responses across HER3-high and HER3-low tumors but also a non-negligible risk of interstitial lung disease, including fatal events (Krop et al., 2023). Together with earlier phase I data demonstrating dose-limiting hematologic/hepatic toxicities for HER3-DXd (Tsurutani et al., 2020), these findings suggest that translation to CRC will likely depend on rigorous biomarker-driven enrichment (e.g., quantitative antigen density, internalization signatures) and careful safety mitigation rather than assuming that ubiquitous HER3 expression is sufficient. A consolidated comparison is provided in Table 3.

3.2 Emerging and exploratory targets

3.2.1 Target: EGFR

Human epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), also known as ErbB1/HER1, is a member of the ErbB family (Kumagai et al., 2021). In the absence of specific ligands, EGFR remains inactive (Yarden and Sliwkowski, 2001). The binding of ligands to the extracellular domain induces homodimerization or heterodimerization with other ErbB RTKs, triggering phosphorylation of the tyrosine kinase domain. This activates downstream signalling pathways, including the RAS/RAF/MAPK pathway (Hynes and Lane, 2005) and the PI3K/AKT pathway (Glaviano et al., 2023). Currently, anti-EGFR monoclonal antibodies such as cetuximab and panitumumab are effective only in a small subset of cancer patients (Ciardiello and Tortora, 2008; Bokemeyer et al., 2011; Douillard et al., 2014; Van Cutsem et al., 2015). Therefore, EGFR-targeted ADCs may represent a novel strategy to overcome these limitations.

3.2.1.1 ABBV-321 (serclutamab talirine)

ABBV-321 is an EGFR-targeting ADC that couples the affinity-matured antibody AM1 with a pyrrolobenzodiazepine (PBD) dimer (Anderson et al., 2020; Carneiro et al., 2023). ABBV-321 may extend therapeutic activity to colorectal tumours with low-to-moderate EGFR expression. PBD dimer is a DNA cross-linker with significantly stronger antitumour activity and a more potent bystander effect compared with those of clinically validated payloads such as MMAE or maytansinoids. Since colorectal tumours often express relatively low levels of EGFR, most cell lines are largely insensitive to MMAE-based ADCs. However, ABBV-321 has demonstrated notable cytotoxic activity in colorectal cancer cell lines and in xenograft models (Anderson et al., 2020). A phase I study evaluating the safety, pharmacokinetics, and antitumour activity of ABBV-321 in patients with advanced solid tumours associated with EGFR overexpression was completed (NCT03234712).

3.2.1.2 Limitations and future directions

EGFR is a validated target for naked antibodies in RAS wild-type CRC, but ADC approaches have not yet demonstrated clear benefit in CRC, underscoring that target “validation” does not automatically translate to ADC success. In the first-in-human trial of the EGFR-ADC MRG003, the colorectal cancer expansion cohort reported an objective response rate of 0% (disease control rate 25%), implying that EGFR IHC positivity alone may be an insufficient enrichment strategy (Qiu et al., 2022). In parallel, on-target/off-tumour toxicity remains a central limitation for EGFR ADCs: depatuxizumab mafodotin (ABT-414) was associated with eye-related adverse events in 91% of EGFR-amplified glioblastoma patients and grade 3/4 ocular events in 33% (van den Bent et al., 2017). For CRC, these data argue for a narrower therapeutic window and motivate next-generation design choices—payloads/linkers with improved tolerability, prophylactic eye-care protocols, and biomarker strategies beyond EGFR expression (e.g., amplification/internalization or conditional activation) to justify continued development.

3.2.2 Target: GCC

Guanylyl cyclase C (GCC) is the receptor for diarrhoea-inducing heat-stable enterotoxins as well as the endogenous ligands guanosine and uridine (Waldman and Camilleri, 2018). In normal gastrointestinal tissue, GCC expression is restricted to the apical surface of epithelial cells at tight junctions, where it is isolated from systemic circulation (Carrithers et al., 1996). Upon ligand binding, GCC undergoes receptor-mediated endocytosis (Urbanski et al., 1995). In contrast, GCC is expressed in more than 95% of primary and metastatic colorectal cancers and in approximately 65% of oesophageal, gastric, and pancreatic tumours (Urbanski et al., 1995; Waldman et al., 1998; Buc et al., 2005). As such, the GCC has attracted interest as a potential ADC target.

3.2.2.1 TAK-164

TAK-164 is a GCC-targeted ADC in which the highly cytotoxic DNA alkylator DGN549 is conjugated to a human anti-GCC monoclonal antibody via a peptide linker (Abu-Yousif et al., 2020). Preclinical studies have confirmed that TAK-164 selectively binds, internalizes, and induces potent cytotoxicity in GCC-expressing cells. A single intravenous dose of TAK-164 (0.76 mg/kg) significantly inhibited tumour growth in an mCRC primary human tumour xenograft model. Imaging studies further demonstrated a positive correlation between GCC expression and TAK-164 tumour uptake. However, the results from a multicentre phase I dose-escalation trial indicated dose-limiting hepatotoxicity at higher levels and insufficient clinical benefit, leading to the discontinuation of the study (Kim R. et al., 2023).

3.2.2.2 TAK-264 (MLN0264)

TAK-264, also known as MLN0264, is a GCC-targeted ADC in which a fully human anti-GCC monoclonal antibody is conjugated to MMAE via the protease-cleavable peptide maleimido-caproyl-valine-citrulline (VC) (Gallery et al., 2018). In vitro studies confirmed its selective binding, internalization, and cytotoxicity against GCC-expressing cells. In vivo, TAK-264 demonstrated dose-dependent antitumour activity and favourable tolerability in HEK293-GCC-engineered models and human primary tumour xenografts. In a first-in-human phase I trial, 35 patients were enrolled, the majority (85%) of whom had mCRC. While TAK-264 was generally well tolerated and safe, no clear antitumour activity or clinical benefit was observed in mCRC (Almhanna et al., 2016).

3.2.2.3 Limitations and future directions

GCC expression is highly enriched in intestinal epithelium and is retained in many CRCs, making it an attractive antigen; however, clinical experience with GCC-directed ADCs highlights the complexity of apparently “restricted” targets. In a phase I study of TAK-264 (MLN0264), antitumor activity was limited despite GCC expression, and gastrointestinal toxicities such as diarrhea were common, indicating that normal gut expression can still translate into a constrained therapeutic index (Almhanna et al., 2016). More recently, TAK-164 also showed limited efficacy together with notable GI adverse events, reinforcing that GCC targeting may require alternative payload/linker choices or locally activated approaches to improve the balance between efficacy and safety (Kim R. et al., 2023). A consolidated comparison is provided in Table 3.

3.2.3 Target: CEACAM5

Carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule-5 (CEACAM5), also known as CEA or CD66e, is a well-established diagnostic marker in CRC (MacSween et al., 1972; Beauchemin and Arabzadeh, 2013). CEACAM5 is also highly expressed in multiple malignancies, such as pancreatic cancer, gallbladder cancer, non-small cell lung cancer, and bladder cancer, but its expression in normal tissues is limited (Eades-Perner et al., 1994; Beauchemin and Arabzadeh, 2013). As a serum biomarker, CEACAM5 demonstrated the highest sensitivity (93.7%) and specificity (96.1%) in a CRC cohort (Tiernan et al., 2013). Its tumour-specific overexpression makes CEACAM5 an ideal target for ADC-based therapies.

3.2.3.1 IMMU-130 (labetuzumab govitecan)

IMMU-130 (labetuzumab govitecan) is an ADC that targets CEACAM5. Clinically, in patients with advanced, refractory, or relapsed mCRC, IMMU-130 demonstrated promising therapeutic activity. It couples the humanized anti-CEACAM5 monoclonal antibody labetuzumab with the moderately cytotoxic topoisomerase I inhibitor SN-38 via a relatively stable CL2A linker, with a high DAR of 7–8 (Moon et al., 2008; Govindan et al., 2009; Dong et al., 2019). IMMU-130 significantly inhibited tumour growth in GW-39 human colon cancer lung metastasis models and subcutaneous LS174T xenograft models in nude mice (Govindan et al., 2009). Two independent phase I clinical trials have been initiated. Among 86 patients who had received five prior lines of therapy, 38% experienced tumour shrinkage and a decline in CEA levels; one patient achieved a partial response lasting more than 2 years, and 42 patients had stable disease, representing the best overall disease control (Dotan et al., 2017). Neutropenia was the only major controllable adverse event (Segal et al., 2014). A phase II clinical study of IMMU-130 in metastatic CRC patients is currently ongoing (Govindan et al., 2015).

3.2.3.2 Precemtabart tocentecan

Precemtabart tocentecan (Precem-TcT, previously M9140) is the first clinical-stage TOP1 inhibitor–based ADC targeting CEACAM5 and was generated by conjugating a CEACAM5-specific antibody with exatecan (Raab-Westphal et al., 2024). Preclinical studies have shown potent antitumour activity and pronounced bystander effects. In the dose-escalation stage of the ongoing phase I trial (PROCEADE-CRC-01), 40 heavily pretreated, irinotecan-refractory mCRC patients received precemtabart tocentecan once every 3 weeks. The results revealed a disease control rate (DCR) of 58.8% (with a confirmed partial response rate of 8.8%) and a median progression-free survival (mPFS) of 6.7 months (95% CI: 4.6–8.8), indicating encouraging antitumour efficacy (Kopetz et al., 2025a). The main adverse events were haematologic toxicities, which were largely manageable with appropriate interventions. Notably, no interstitial lung disease or ocular toxicity was reported.

3.2.3.3 SAR408701 (tusamitamab ravtansine)

SAR408701 is a novel ADC that targets CEACAM5, in which the anti-CEACAM5 antibody SAR408377 is covalently linked to the cytotoxic maytansinoid DM4. In CRC PDX models, SAR408701 showed robust antitumour activity with a clear dose–response relationship, and compared with a single dose, repeated administration resulted in greater responses (Decary et al., 2020). In the first-in-human dose-escalation study, 18 patients with CRC were treated with SAR408701 (Gazzah et al., 2022). Objective responses were observed in 3 patients (9.7%), including two patients with ≥2+ CEACAM5 expression on 100% of tumour cell membranes. In terms of safety, the incidence and severity of haematologic toxicity were lower than those associated with standard antimicrotubule agents such as docetaxel (Guastalla and Diéras, 2003). The dose-limiting toxicity of SAR408701 was reversible keratopathy.

3.2.3.4 Limitations and future directions

CEACAM5 is highly prevalent in CRC, but heterogeneous expression and antigen shedding can create an “antigen sink” and reduce effective tumor exposure, complicating ADC translation. In a phase I study of the CEACAM5-directed ADC labetuzumab govitecan (SN-38), clinical activity in refractory mCRC was modest and key toxicities (notably neutropenia and diarrhea) reflected systemic payload exposure (Dotan et al., 2017). These results suggest that CEACAM5-ADC development may benefit from next-generation designs that better separate tumor versus normal-tissue exposure (e.g., optimized linker stability and bystander effect) and from biomarker strategies that go beyond IHC positivity to incorporate quantitative antigen density and shedding dynamics. A consolidated comparison is provided in Table 3.

3.2.4 Emerging targets

In addition to HER2, HER3, EGFR, GCC, and CEACAM5, several emerging targets, including CDH17, PD-L1, and LGR5, have recently been investigated in CRC. These targets are characterized by relatively specific expression profiles and are often closely associated with tumour initiation and progression, immune evasion, stem cell maintenance, and drug resistance. Although the number of ADCs developed against these targets remains limited, most agents still at the preclinical or early clinical stage have already demonstrated certain antitumour potential. To provide a more straightforward overview of these advances, representative information on the corresponding ADCs is summarized in Table 4.

3.3 ADC combination strategies

Owing to the complexity of cancer treatment caused by tumour heterogeneity and drug resistance, multiple therapeutic approaches are often combined in clinical practice to improve the likelihood of remission and cure. The primary methods for increasing the efficacy of ADCs or overcoming resistance involve combining ADCs with other therapeutic strategies, such as chemotherapy, targeted agents, and immunotherapy.

3.3.1 ADCs combined with chemotherapy

Rational combinations of antibody–drug conjugates (ADCs) with conventional chemotherapy are increasingly explored to deepen responses and delay or overcome resistance, provided that the partner drug adds complementary antitumor pressure without duplicating the ADC’s dose-limiting toxicities (Pretelli et al., 2024; Wei et al., 2024). Because most ADCs require binding, internalization, and intracellular processing to release active payload, the sequence of administration can meaningfully affect efficacy: preclinical data suggest that sequential dosing can produce greater tumor cell damage than concurrent administration (Wei et al., 2024). Despite these potential benefits, the major barrier to clinical development remains tolerability, as ADC–chemotherapy combinations frequently exacerbate grade ≥3 adverse events, consistent with overlapping systemic toxicities driven by off-target/on-target off-tumor exposure to payload (Tan et al., 2025). This risk is further shaped by ADC design features such as linker stability and DAR, which influence systemic free payload exposure and correlate with severe toxicities, underscoring the need for careful partner selection and schedule/dose optimization in combination regimens (Markides et al., 2024; Tang S. C. et al., 2024; Tan et al., 2025).

In both preclinical and clinical studies, combining different forms of chemotherapy with ADCs has been widely recognized as an effective strategy to overcome resistance and achieve favourable therapeutic outcomes (Yardley, 2013). The synergistic interactions between chemotherapy and ADCs include targeting different stages of the cell cycle or modulating the expression of tumour cell surface antigens. The sequence of administration plays a critical role in treatment efficacy, which may be related to the efficiency of ADC internalization (Wahl et al., 2001). However, the major challenge limiting the clinical development of these combinations is the significant increase in toxicity, which is likely caused by overlapping toxicity from the off-target and off-tumour effects of ADC payloads (Martin et al., 2016; Cortés et al., 2020).

In preclinical models, RC48 combined with gemcitabine demonstrated synergistic antitumour activity both in vitro and in vivo. Further RNA-seq analyses indicated that the combination may have synergistic effects on CRC cells through the regulation of multiple signalling pathways, such as the p53, PI3K-AKT, and MAPK pathways and pathways involved in the cell cycle(Liu et al., 2024). Another study revealed that Oba01 (an ADC targeting DR5) combined with the CDK inhibitor abemaciclib significantly enhanced the in vivo inhibition of microsatellite stability (MSS) and microsatellite instability-high (MSI-H) CRC PDX growth without inducing toxicity or resistance (Zhou D. et al., 2025). In rectal cancer PDX models, AMT-562 initially showed promising efficacy, but the tumours quickly relapsed; the combination of AMT-562 with rabusertib resulted in more durable antitumour effects (Weng et al., 2023a). Collectively, these findings highlight the potential of combining ADCs with conventional chemotherapeutics as novel treatment strategies for advanced CRC, particularly the refractory MSS subtype. For patients with a heavy tumour burden and rapid progression, ADC–chemotherapy combinations can achieve rapid tumour control.

3.3.2 ADCs combined with targeted therapy

Targeted therapies—including monoclonal antibodies, tyrosine kinase inhibitors, and antiangiogenic agents—have proven clinical safety and efficacy in tumours with specific mutations, overexpression, or amplification. However, resistance and clonal heterogeneity narrow the therapeutic window of targeted monotherapies, leading to the emergence of ADC–targeted therapy combinations. The goal is to achieve more potent inhibition of oncogene-dependent signalling pathways, increase the availability of surface antigens, and sensitize tumours with low antigen expression. Synergistic mechanisms include improving intratumoural drug delivery via antiangiogenic effects (Ponte et al., 2016; Bordeau et al., 2021), modulating tumour antigen expression (La Monica et al., 2017; Haikala et al., 2022), overcoming intratumoural heterogeneity and resistance (Saatci et al., 2018), and inducing synthetic lethality.

Combining ADCs with targeted agents—such as anti-angiogenic therapies—may enhance antitumour activity in CRC and warrants clinical evaluation. As a monotherapy, AMT-562 showed limited efficacy in CRC, but when it was combined with bevacizumab or cetuximab, it demonstrated significantly increased antitumour activity (Weng et al., 2023a). Currently, clinical trials of RC48 in combination with bevacizumab or tislelizumab are underway in patients with HER2-positive advanced CRC, aiming to further evaluate the efficacy and safety of the combination treatment in a second-line setting (NCT05785325, NCT05493683). The PROCEADE-CRC-01 trial is currently being conducted to evaluate efficacy of Precemtabart tocentecan combined with bevacizumab ± capecitabine or bevacizumab + 5-fluorouracil(Kopetz et al., 2025a).

3.3.3 ADCs combined with immunotherapy

The combination of ADCs with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) is based on a dual mechanism of “localized high-potency cytotoxicity + immune activation.” This combination treatment may potentially overcome the limitations of previous immunotherapies in CRC while enabling more refined individualized treatment. In tumours, ADCs deliver highly potent cytotoxins in a targeted manner, leading to tumour cell death and the release of tumour antigens and damage-associated molecular patterns. This promotes dendritic cell–mediated antigen presentation and T-cell activation. Moreover, ICIs (e.g., anti-PD-1/PD-L1) promote adaptive immune suppression, amplifying the ADC-induced primary immune response (Villacampa et al., 2024).

ADC + ICI strategies should be guided by multidimensional biomarkers—including molecular target expression, MSI status, and tumour-infiltrating immune phenotypes—to achieve true personalized treatment. CRC is highly heterogeneous both molecularly and immunologically, comprising MSI-H (“immune-hot”) and MSS (“immune-cold”) subtypes, different oncogenic drivers (HER2, c-MET, KRAS/BRAF, etc.), and variable antigen expression. Since the vast majority of metastatic CRCs are MSS and unresponsive to ICIs alone, ADCs may act as “tumour heaters” by inducing antigen release and recruiting effector immune cells, thereby substantially expanding the proportion of MSS patients who could benefit from ICIs (Yu et al., 2024). In syngeneic mouse tumour models, RC48 and anti–PD-1 monotherapy inhibited tumour growth. Moreover, their combination further enhanced efficacy without significant body weight loss, indicating that RC48 can sensitize tumours to immunotherapy independent of microsatellite status (Wu X. et al., 2023). Similarly, 84-EBET (a CEACAM6-targeting ADC) combined with an anti–PD-1 antibody showed marked synergy (Kogai et al., 2025).

4 Key challenges in ADC design and therapy

Currently employed ADCs have demonstrated increasingly favourable specificity and cytotoxic properties, highlighting their remarkable potential in cancer treatment. Nevertheless, their design and application continue to face multiple challenges, including the complexity of pharmacokinetics, inevitable toxicity, emergence of resistance and challenges in clinical translation.

4.1 Complex pharmacokinetics

Compared with conventional small-molecule drugs, ADCs exhibit more complex pharmacokinetic profiles. Following intravenous administration, ADCs exist in three distinct forms in circulation: the intact conjugate, the antibody resulting from linker degradation, and the free cytotoxic payload (Guo et al., 2016; Kern et al., 2016). The relative proportions of these species continuously change as the ADC binds its target antigen, undergoes internalization, and dissociates within lysosomes (Lucas et al., 2018). Typically, the concentrations of intact ADCs and naked antibodies gradually decrease over time because of internalization and antibody clearance (Malik et al., 2017). This process is modulated by the mononuclear phagocyte system and neonatal Fc receptor-mediated recycling, in which neonatal Fc receptor binds ADCs within endocytic vesicles and transports them back to the extracellular space for salvage (Xu, 2015; Hamblett et al., 2016; Mahalingaiah et al., 2019). Consequently, antibodies—including both intact ADCs and naked antibodies—generally exhibit longer half-lives than conventional small molecules do. In contrast, the free cytotoxic payload is predominantly metabolized in the liver and eliminated via urine or faeces, a process that can be affected by drug–drug interactions as well as impaired hepatic or renal function (Khera and Thurber, 2018; Mahalingaiah et al., 2019).

4.2 Toxicity

In accordance with the basic design principles of ADCs, the toxicity of ADCs was initially expected to be lower than that of conventional chemotherapy (Drago et al., 2021). However, most ADCs still suffer from off-target toxic effects resembling those of their cytotoxic payloads, as well as on-target toxic effects and other poorly understood, potentially life-threatening adverse events (Colombo and Rich, 2022). Currently, ADC-associated toxicity can be broadly divided into “expected” and “unexpected” categories on the basis of the adverse events typically associated with the type of payload used (Zhu et al., 2023).

4.2.1 Toxicity assessment and risk management

To enhance clinical relevance, toxicity evaluation for ADCs in colorectal cancer should be reported in a standardized manner (CTCAE grading), with explicit documentation of grade ≥3 events, serious adverse events, and the frequencies of dose interruption, reduction, and discontinuation. Cross-trial comparisons should be interpreted cautiously because eligibility criteria, prior lines of therapy, baseline organ function, and supportive-care practices vary substantially across studies; these factors can inflate or attenuate apparent toxicity rates in heavily pretreated mCRC populations.

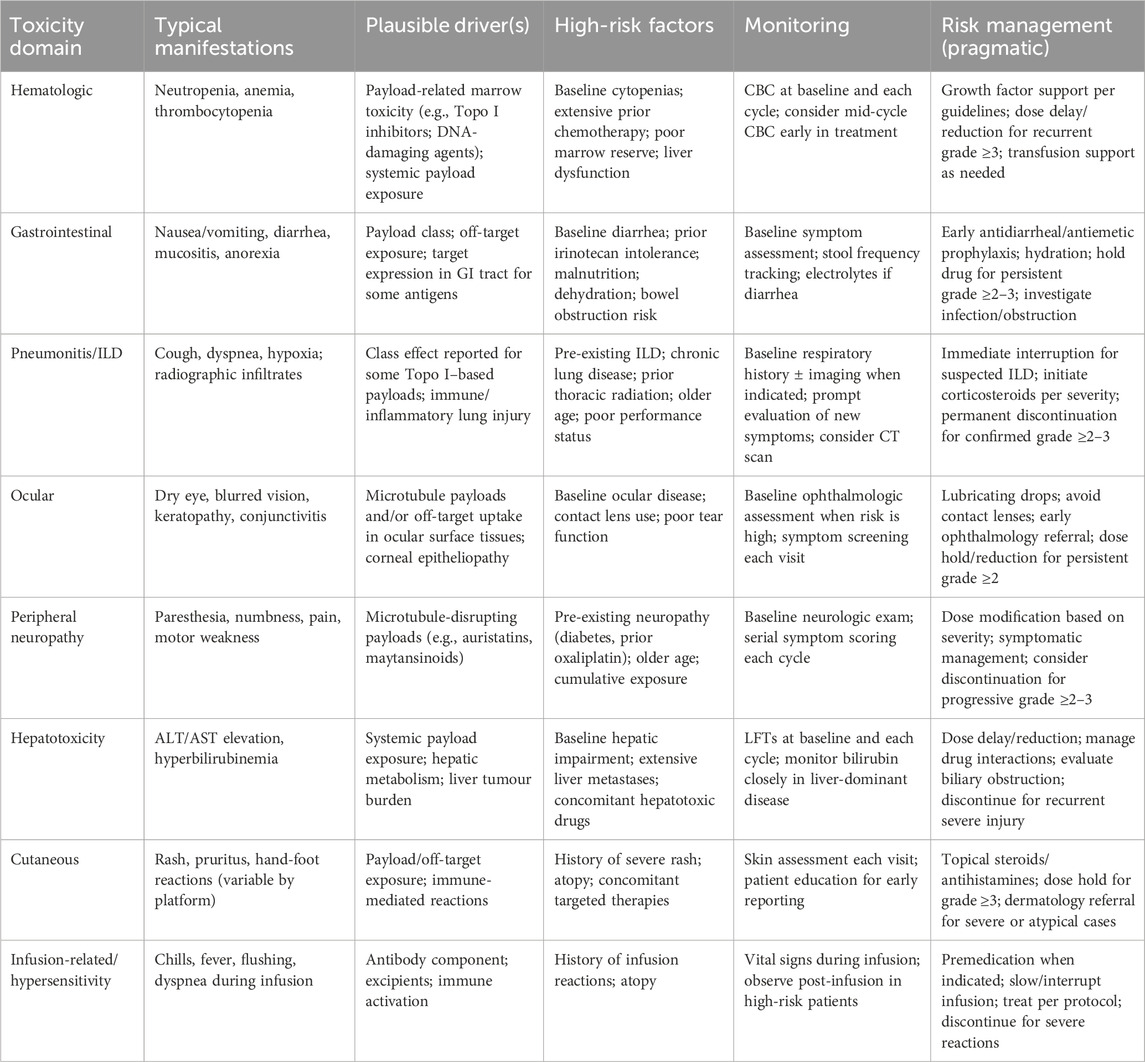

Clinically actionable toxicities can be broadly grouped into hematologic suppression, gastrointestinal toxicity, peripheral neuropathy, ocular events, hepatotoxicity, and pneumonitis/interstitial lung disease (ILD) (Mahalingaiah et al., 2019; Hackshaw et al., 2020; Powell et al., 2020). These patterns are influenced by payload class (Colombo and Rich, 2022; Zhu et al., 2023), linker stability (Donaghy, 2016), and, in some cases, target expression in normal tissues (Hu et al., 2023). A pragmatic summary of common adverse events, plausible drivers, recommended monitoring, and risk-mitigation strategies for CRC practice is provided in Table 5.

Table 5. Adverse events summary and clinical risk management considerations for ADCs in colorectal cancer.

4.2.2 Mechanistic considerations by payload class and clinical implications

Across CRC-directed ADC programs, microtubule-disrupting payloads are most commonly associated with peripheral neuropathy and ocular surface events, often in a cumulative-exposure pattern (Powles et al., 2021). In contrast, Topoisomerase I inhibitor–based payloads more frequently produce myelosuppression and gastrointestinal toxicity and have also been linked to pneumonitis/ILD in some settings, underscoring the need for early recognition and protocolized intervention (Bardia et al., 2021). DNA-damaging payloads may carry broader systemic toxicity and a narrower therapeutic window, making dose optimization and patient selection particularly critical. Because mCRC patients frequently have baseline gastrointestinal symptoms, prior neurotoxic chemotherapy exposure, and substantial hepatic tumour burden, risk stratification and proactive supportive care should be integrated into trial design and routine practice to preserve treatment continuity and maximize benefit.

4.2.3 Unexpected toxic effects and patient-level heterogeneity

Beyond the payload-class patterns and the clinically oriented risk-mitigation framework summarized above (Table 5), ADCs can also induce unexpected or disabling toxicities that are not readily predicted by antigen specificity alone. The mechanisms remain incompletely understood and may involve extra-tumoural antigen expression, nonspecific uptake by normal tissues, and/or systemic enzymatic cleavage resulting in exposure to deconjugated species and free payload. Historically, this phenomenon was highlighted by the LeY-targeting conjugate BR96–doxorubicin, which produced prominent gastrointestinal toxicity rather than the “expected” hematologic or cardiac toxicities typically associated with doxorubicin. (Saleh et al., 2000). Cardiotoxicity has also been observed with trastuzumab-based platforms, including T-DM1 and T-DXd, consistent with potential on-target/off-tumour liability of the antibody component, whereas such toxicity appears less common with other DXd-based programs (Hu et al., 2023).

Importantly, interstitial lung disease (ILD)/pneumonitis has been reported across multiple ADCs with variable incidence and severity and may occur with patterns that are not strictly dependent on antigen specificity or payload type, underscoring the need for early recognition and protocolized intervention (Hackshaw et al., 2020; Kumagai et al., 2020; Tarantino et al., 2021). In addition to between-drug variability, clinically meaningful heterogeneity exists among patients receiving the same ADC, as baseline organ function, comorbidities, and inter-individual PK/PD differences can modify both toxicity phenotype and severity(Powell et al., 2022; Tang M. et al., 2024); therefore, eligibility criteria, monitoring intensity, and dose-modification algorithms should be tailored accordingly. When ADCs are combined with chemotherapy or other systemic agents, these risks may be amplified through overlap or unexpected synergy, further reinforcing the value of predefined stopping rules and organ-specific management pathways.

4.3 Resistance

A major challenge in ADC development is drug resistance, which can be either primary or acquired. The underlying mechanisms primarily include downregulation of target antigen expression, resistance to payloads, impaired drug internalization and trafficking, dysfunction of lysosomes, overexpression of drug efflux transporters, and activation of bypass signalling pathways (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Mechanisms of action and resistance to ADCs in colorectal cancer therapy. The left panel illustrates the normal mechanism of ADC action. The antibody component of the ADC binds to the target antigen and is internalized via endocytosis, leading to invagination of the plasma membrane and formation of endosomes, which subsequently fuse with lysosomes. Following lysosomal cleavage, the payload is released into the cytoplasm, where it induces tumour cell apoptosis or death by targeting DNA breaks, disrupting microtubules, or inhibiting topoisomerases. Lipophilic payloads may also diffuse into neighbouring cells, resulting in a bystander effect. Concurrently, the monoclonal antibody component of the ADC can trigger antitumour immunity through effector functions such as ADCC, ADCP, and CDC. The right panel depicts potential mechanisms of ADC resistance, including downregulation of target antigen expression, payload resistance, impaired drug internalization and trafficking, lysosomal dysfunction, overexpression of drug efflux pumps, and activation of bypass signalling pathways.

4.3.1 Downregulation of target antigen expression

The most common mechanism of ADC resistance is the downregulation of target antigen expression, which parallels the principles of resistance observed with monoclonal antibodies. With increasing drug exposure, target antigens may undergo mutations, copy number alterations, or structural modifications, thereby reducing the likelihood of antibody–antigen binding. Preclinical studies have demonstrated that when used to generate xenograft tumours responsive to high-dose T-DM1, JIMT1 cells resistant to trastuzumab acquire secondary resistance following cyclic T-DM1 treatment, accompanied by reduced HER2 expression (Loganzo et al., 2015; Loganzo et al., 2016). Interestingly, the bystander effect mediated by cleavable linkers can partially overcome the reduced response associated with lower antigen expression (Sung et al., 2016). In addition to decreased antigen levels, dimerization of the target antigen with another cell surface receptor can also contribute to ADC resistance. For example, NRG-1β, a ligand that induces HER2/HER3 heterodimerization, inhibits T-DM1-mediated cytotoxicity in HER2-amplified breast cancer cells. This resistance can be overcome by combination with pertuzumab, which blocks HER2/HER3 dimerization and downstream signalling (Phillips et al., 2014).

4.3.2 Payload-associated resistance

Beyond aberrant antigen expression, tumour cells may also develop resistance directly to the cytotoxic payload. In the treatment of non-Hodgkin lymphoma, clinical efficacy was increased by replacing auristatin-based payloads with anthracycline-based payloads (Yu et al., 2015). In addition to payload type, the conjugation site and the average DAR are critical determinants of ADC performance (Yoder et al., 2019; Bai et al., 2020). Preclinical data indicate that while increasing the DAR enhances drug load, it also accelerates clearance, potentially reducing ADC efficacy (Sun et al., 2017).

4.3.3 Impaired internalization and intracellular trafficking

ADCs are internalized into cancer cells primarily via endocytosis, which can occur through multiple pathways, including clathrin-mediated endocytosis, caveolae-mediated endocytosis, and clathrin–caveolin-independent endocytosis (Kalim et al., 2017). In a developed T-DM1-resistant model (N87-TM), upregulation of caveolin-1 (Cav-1), polymerase I, and transcriptional regulators involved in vesicle formation and endocytosis combined with reduced lysosomal colocalization impaired drug internalization and trafficking, resulting in T-DM1 insensitivity (Sung et al., 2018). In HER2-positive breast cancer, endophilin A2 promotes HER2 endocytosis and increases tumour cell sensitivity to trastuzumab. SH3GL1 knockdown in tumour cells decreases endocytosis and significantly reduces T-DM1-mediated cytotoxicity (Baldassarre et al., 2017).

4.3.4 Lysosomal dysfunction

Following receptor-mediated endocytosis, ADCs are trafficked to lysosomes, where their cytotoxic payloads are released through chemical or enzymatic cleavage. Most lysosomal hydrolases require an acidic environment for optimal activity, a condition maintained by vacuolar ATPase (Mellman, 1989). This mechanism has been demonstrated in the T-DM1-resistant cell line N87-KR, which exhibited binding and internalization kinetics similar to those of parental N87 cells but showed markedly reduced lysosomal acidification due to impaired vacuolar ATPase activity. This defect diminished T-DM1 catabolism and conferred resistance (Wang et al., 2017). Beyond pH regulation, specific transporters also play critical roles, particularly for ADCs with noncleavable linkers, as their metabolites require dedicated transport proteins to reach the cytoplasm. RNA sequencing studies have identified SLC46A3 as a key transporter that mediates the cytoplasmic translocation of maytansine-based catabolites. The silencing of SLC46A3 led to the lysosomal accumulation of metabolites and ultimately drug resistance (Hamblett et al., 2015).

4.3.5 Overexpression of drug efflux transporters

The overexpression of ATP-binding cassette transporters plays a pivotal role in chemotherapy resistance and has been well documented across multiple cancer types. These efflux pumps facilitate the active extrusion of drugs from tumour cells, thereby conferring an multidrug resistance phenotype (Leonard et al., 2003; Yu et al., 2013; Dong et al., 2024). Since many ADC payloads, such as maytansinoids, are substrates of ATP-binding cassette transporters, their overexpression can directly impair ADC efficacy (Kovtun et al., 2010; Cianfriglia, 2013). For instance, studies in T-DM1-resistant cells demonstrated that, despite preserving HER2 overexpression, upregulation of ABCC2 and ABCG2 promoted DM1 efflux, leading to acquired resistance. Importantly, inhibition of these transporters was shown to restore T-DM1 sensitivity (Takegawa et al., 2017).

4.3.6 Activation of bypass signalling pathways

The activation of alternative signalling pathways is another key mechanism through which tumours acquire resistance to ADCs. A prototypical example is the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway, which regulates cell survival, growth, and metabolism. Aberrant activation of this pathway can reduce ADC sensitivity and attenuate payload efficacy. Clinically, a diminished therapeutic response to trastuzumab has been observed in patients harbouring PIK3CA mutations or with PTEN loss (Baselga et al., 2016). Mechanistic studies have indicated that PTEN deficiency or PIK3CA hyperactivation reduces trastuzumab sensitivity through constitutive activation of PI3K/AKT signalling (Berns et al., 2007). In addition, activation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway has been implicated in ADC resistance. Overexpression of Wnt3 promotes β-catenin accumulation, thereby promoting tumour cell proliferation and invasion while simultaneously conferring resistance to trastuzumab (Wu et al., 2012).

4.4 Challenges in clinical translation

The complex tripartite structure of ADCs imposes stringent chemical, manufacturing, and control requirements. Major production challenges include maintaining conjugation efficiency within a batch-to-batch variability of ±5% and ensuring payload stability during the lyophilization process. These technical hurdles contribute to development costs exceeding 500 million USD for each approved ADC, with 67% of clinical-stage candidates failing because of an insufficient therapeutic index (Beck et al., 2017; Khera and Thurber, 2018; Mahalingaiah et al., 2019). Despite successful drug development, multiple challenges remain in translating ADCs into clinical practice. First, reliable biomarkers capable of predicting drug activity and toxicity are needed to guide patient selection and identify the optimal target population (Williams et al., 2020; Mathiot et al., 2024). Second, issues of high cost and economic accessibility persist. Multiple cost-effectiveness analyses have indicated that at the current prices, certain ADCs fail to meet the acceptable quality-adjusted life year gain thresholds for most healthcare systems worldwide (Liu et al., 2025; Wong et al., 2025). Finally, target homogeneity and market feasibility present further obstacles. Currently employed ADC development pipelines exhibit target redundancy, with 43% of clinical candidates directed against HER2 or TROP2 (Tarantino et al., 2022). This concentration leads to treatment duplication, while emerging targets such as CLDN6 and PTK7 are overlooked. Such market saturation may reduce commercial returns and stifle innovation in target discovery.

5 Future directions of ADCs: bridging innovation and personalized therapy

As CRC treatment advances towards greater precision and multidimensional development, the future trajectory of ADCs is gradually shifting from “standalone drug innovation” to “systematic and individualized solutions.” This transition encompasses not only structural innovations within ADCs—such as probody drug conjugates (PDCs) and bispecific antibodies—but also hybrid platforms integrating nanotechnology to overcome conventional delivery limitations. Moreover, rapid progress in multiomics technologies and artificial intelligence enables precise patient stratification and therapeutic response prediction, providing strong support for the application of ADCs in heterogeneous CRC populations. The integration of biomarker-driven personalized treatment strategies with novel clinical trial designs (e.g., basket/umbrella trials) further advances the transformation of ADCs from “innovative molecules” into “precision medicine tools,” thereby offering CRC patients more targeted and sustainable treatment options.

5.1 Innovations in ADC design

Antigen selection plays a pivotal role in determining ADC efficacy. The ideal antigen is differentially expressed between tumours and normal tissues, is located on the cell surface, and is efficiently internalized (Beck et al., 2017). With increasing research, the scope of ADC targets has expanded beyond classical tumour-associated antigens to include those in the tumour microenvironment (TME) and cancer stem cell markers (Lee et al., 2018). Computational strategies leveraging multiomics and proteomic data are accelerating antigen discovery (Schettini et al., 2021; Guan et al., 2023). In parallel, noninternalizing approaches are also under investigation, wherein ADCs target extracellular components within the TME, enabling payload release into the extracellular space and subsequent tumour penetration through diffusion and bystander effects (Ashman et al., 2022). For instance, APNU, a conjugated antibody directed against splice variants of tenascin-C, has shown complete remission in preclinical studies (Dal Corso et al., 2017). Similarly, galectin-3–binding protein, which is secreted predominantly by tumour cells, has been proposed as a potential extracellular ADC target (Giansanti et al., 2019). Therefore, the extracellular release of payloads with good diffusion and bystander effects may be a breakthrough opportunity to increase the efficacy of ADCs in the treatment of solid tumours (Staudacher and Brown, 2017).

For decades, microtubule inhibitors, topoisomerase inhibitors, and DNA-damaging agents have been the predominant payload types in ADCs. With more in-depth basic research, multiple promising strategies for payload optimization have emerged. First, the focus of payload development is gradually shifting from traditional cytotoxic drugs to novel agents with noncytotoxic mechanisms, such as topoisomerase II (Top2) inhibitors, RNA polymerase inhibitors, apoptosis inducers (e.g., Bcl-xL inhibitors), heterobifunctional protein degraders, tyrosine kinase inhibitors, and immunostimulatory agents (Beck et al., 2017; Boghaert et al., 2022; Conilh et al., 2023).

Although the development of ADCs has largely relied on classical monospecific antibodies for targeting, alternative strategies such as PDCs and biparatopic or bispecific ADCs are being actively explored. PDCs represent conditionally activated ADCs, designed by introducing a protease-cleavable masking peptide into the antigen-binding region of the antibody, which becomes selectively activated in the TME (Autio et al., 2020). In nonmalignant tissues, PDCs remain intact, but upon entry into protease-rich tumour regions, the masking peptide is cleaved, exposing the antigen-binding site and enabling the recognition of tumour antigens and release of payloads (Poreba, 2020). By delaying antigen binding and improving tumour penetration, this approach helps overcome the common “binding site barrier” in solid tumours, significantly increasing the therapeutic index and efficacy (Bordeau et al., 2021; Chen et al., 2022). Another strategy involves conjugating payloads to biparatopic or bispecific antibodies. Biparatopic antibodies bind to two distinct epitopes on the same antigen, thereby increasing binding affinity. This improved stability and tumour-targeting efficiency directly translate to superior therapeutic efficacy (Koganemaru and Shitara, 2020; Chavda et al., 2022). Bispecific antibodies, capable of targeting two different antigens, offer greater selectivity and improved tumour cell internalization, which may overcome resistance to ADCs (Mazor et al., 2015; Sellmann et al., 2016; Antonarelli et al., 2021). Several bispecific ADCs are currently under development and have entered phase I clinical trials (de Goeij et al., 2016; Andreev et al., 2017; Hong Y. et al., 2023). Moreover, the creation of trispecific and multifunctional antibodies represents a promising strategy to address receptor redundancy and tumour heterogeneity, providing new avenues for personalized treatment (Khoury et al., 2023).

5.2 Integration of ADCs with multidisciplinary approaches

Polymeric nanoparticles, as representative advanced drug delivery systems, are suitable carriers with multiple advantages, including enhanced drug solubility, a prolonged circulation half-life, reduced immunogenicity, controlled and targeted release, and improved safety (Ekladious et al., 2019; Patel et al., 2024; Guo et al., 2025). By exploiting the unique properties of nanoparticles, such as their small size and ability to leverage the enhanced permeability and retention effect, ADC stability can be improved, circulation time can be prolonged, and tumour targeting can be more effective (Falvo et al., 2013; El-Dakroury et al., 2024; Hong et al., 2024). In colorectal cancer models, bovine serum albumin (BSA) nanoparticles prepared by the desolvation method have been used to encapsulate small-molecule therapeutics and enhance antitumour efficacy (Kayani et al., 2018). In addition to drug encapsulation, albumin nanoparticles can serve as a carrier surface for antibody-mediated targeting; for example, an EGFR-targeted conjugate can be immobilized/adsorbed onto BSA nanoparticle surfaces to create a targeted nanocarrier with improved cellular association and antitumour activity (Ye et al., 2021). Collectively, these nanocarrier strategies highlight how albumin-based nanoparticles can be engineered for payload delivery and antibody-guided tumour targeting in CRC.

The integration of multiple types of therapies with ADCs can achieve the personalized treatment of CRC. The high molecular heterogeneity of CRC means that a single biomarker is often insufficient to predict patient responses to ADCs. With the rapid advancements in genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics, researchers are now able to systematically identify molecular-level differences among CRC patients. For instance, HER2 amplification, BRAF V600E mutation, KRAS/NRAS status, and MSI are all closely associated with ADC responsiveness, providing a strong foundation for multiomics–driven precision stratification (Yaeger et al., 2018). The introduction of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning tools has further enabled the integration and pattern recognition of complex multiomics datasets. Using deep learning models, researchers can extract potential predictive factors of response from large-scale clinical and molecular data, thereby assisting in the identification of patients most likely to benefit (Azuaje, 2019; Kather et al., 2019). Beyond efficacy prediction, the combination of multiomics and AI also facilitates the monitoring of resistance mechanisms. By longitudinally tracking circulating tumour DNA and protein biomarkers in patient blood samples, AI algorithms can dynamically analyse tumour evolutionary trajectories, identify potential resistance mutations, and guide strategies for ADC combination or sequential therapies (Siravegna et al., 2015; Sobhani et al., 2024).

As more ADCs with innovative mechanisms enter clinical testing and combination trials progress, the development of predictive biomarkers is becoming a central focus in next-generation ADC research. Current evidence suggests that relying solely on IHC to evaluate target expression may not sufficiently predict therapeutic outcomes. To address this limitation, multiple strategies are being adopted to refine predictive models. On the one hand, new technologies, such as quantitative immunofluorescence (Moutafi et al., 2022), mass spectrometry (Zhu et al., 2020), reverse-phase protein arrays (Petricoin et al., 2023), and digital pathology–based analysis of IHC slides (Spitzmüller et al., 2023), are being employed to more precisely quantify target expression. On the other hand, the dynamic changes in target expression on circulating tumour cells are also being investigated as potential indicators for efficacy prediction (Danila et al., 2019; Pistilli et al., 2023).

5.3 Emerging clinical trial models

Traditional clinical trials are often stratified by tumour histology. However, given the highly complex molecular heterogeneity of CRC, this approach no longer adequately meets the needs of precision medicine. Basket and umbrella trial designs have therefore emerged. Basket trials allow the recruitment of patients across different cancer types on the basis of shared molecular markers (e.g., HER2 amplification and Trop-2 overexpression), thereby evaluating the cross-tumour applicability of specific ADCs (Hyman et al., 2018). This design is particularly important for CRC molecular subgroups with relatively small patient populations, as it helps avoid trial stagnation because of low enrolment of patients with a single cancer type. In contrast, umbrella trials stratify patients within a single cancer type (e.g., CRC) according to distinct molecular subtypes (e.g., HER2+, KRAS mutation, and CLDN18.2 expression), enabling the evaluation of multiple ADCs or ADC-based combinations in parallel (Dienstmann et al., 2017). Furthermore, adaptive trial designs combined with real-world data are accelerating the clinical translation of ADC research. By incorporating dynamic adjustment mechanisms, researchers can optimize dosing, refine patient subgroup selection, or redirect study designs in response to interim results (Berry et al., 2015). This not only increases trial efficiency but also expedites the validation and implementation of personalized treatment strategies. Collectively, these novel clinical trial models provide flexible and efficient platforms for validating ADCs in CRC, with the potential to shorten development timelines and advance the clinical practice of precision oncology.

6 Conclusion

As an innovative therapeutic strategy, ADCs have demonstrated significant clinical potential in a variety of solid tumours. Importantly, several ADC programs have already generated clinically meaningful signals in CRC cohorts—for example, T-DXd has shown robust activity in HER2-positive metastatic CRC in the DESTINY-CRC studies, RC48 is being evaluated in HER2-expressing advanced CRC, and CEACAM5-directed topoisomerase I inhibitor ADCs (e.g., precemtabart tocentecan/M9140) have reported encouraging disease control in heavily pretreated, irinotecan-refractory mCRC. Nevertheless, no ADC has yet been approved specifically for CRC, underscoring the substantial unmet clinical need. With continuous innovations in antibody engineering, linker design, payload diversification, and conjugation technologies, the specificity, stability, and safety of ADCs are steadily improving, enabling them to evolve into precise drug delivery systems.

The future value of ADCs lies not only in providing more treatment options but also in their deep integration with personalized medicine. Through molecular diagnostics, patient subgroups can be precisely stratified, allowing antibody selection to align with specific tumour antigen profiles. Smart linkers and adjustable DARs enable controllable payload release, while diverse payloads, such as topoisomerase inhibitors and immune modulators, can meet the therapeutic needs of patients with different molecular subtypes. Moreover, the exploration of ADCs in combination with immunotherapy, molecular targeted therapy, and chemotherapy provides new strategies to address the molecular heterogeneity and drug resistance of CRC.