Abstract

Malignant melanoma is an aggressive skin malignancy with a complex molecular landscape and limited treatment durability in advanced stages. Aberrations in the MAPK pathway—most notably BRAF and NRAS mutations—have catalyzed the development of targeted therapies, particularly BRAF/MEK inhibitors, which have transformed outcomes in BRAF-mutant melanoma. However, resistance remains prevalent, driven by MAPK reactivation, epigenetic rewiring, and tumor microenvironmental feedback. In NRAS-mutant subtypes, MEK inhibition, CDK4/6 blockade, and immune checkpoint inhibition offer partial efficacy, yet monotherapies fail to achieve sustained responses. Emerging strategies focus on combinatorial regimens targeting RAF-MEK-ERK and PI3K-AKT axes, alongside immunotherapeutic integration. Rarer alterations in KIT and RTKs also define actionable subsets. This review synthesizes recent mechanistic insights and therapeutic advances in mutation-driven melanoma, highlighting the promise of biomarker-guided combination strategies and signaling crosstalk disruption as the next frontier in precision oncology.

1 Introduction

Malignant melanoma is the most lethal form of skin cancer, accounting for 80% of skin cancer–related deaths, largely due to its strong metastatic propensity and complex molecular heterogeneity (Force et al., 2025). Although surgical resection is often curative in early-stage disease, advanced melanoma remains difficult to treat, as conventional systemic regimens typically deliver low objective response rates (ORRs) and substantial toxicity (Davis et al., 2019; Smalley et al., 2016; Kim et al., 2013). The discovery of oncogenic alterations within the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway, particularly BRAF mutations, has reshaped therapeutic paradigms (Reddi et al., 2022). Accordingly, targeted strategies, including BRAF inhibitors combined with MEK inhibitors such as trametinib or cobimetinib, have produced clinically meaningful benefits in patients with BRAF-mutant melanoma (Eroglu and Ribas, 2016; Eroglu and Ozgun, 2018).

Nevertheless, durability of response is frequently curtailed by resistance mechanisms, including MAPK pathway reactivation and intratumoral heterogeneity, necessitating integrated treatment modalities. Dual blockade of BRAF and MEK, as well as immunotherapy combinations involving PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors, have been explored to mitigate resistance and enhance therapeutic efficacy (Haugh et al., 2021; Ribas et al., 2019; Ferrucci et al., 2020). In NRAS-mutant melanoma, MEK inhibition and immune checkpoint blockade represent pivotal approaches, though clinical benefit varies across demographic groups (Dummer et al., 2017; Lebbé et al., 2020). Additionally, rarer genetic alterations, such as those in KIT, GNAQ, GNA11, and NF1, are implicated in MAPK hyperactivation, particularly in BRAF- and NRAS-wild-type subsets (Guhan et al., 2021; Cosgarea et al., 2017). These variants not only shape melanoma progression but also contribute to treatment resistance and are increasingly employed as biomarkers to inform precision interventions (Revythis et al., 2021). Combinatorial strategies that integrate targeted pathway suppression with immunomodulation are under active development, aiming to circumvent resistance and restrain metastasis (Kim and Kim, 2024). This review delineates current advancements and persisting obstacles in the pursuit of personalized melanoma therapy.

2 BRAF/MAPK signaling pathway in malignant melanoma

2.1 The MAPK signaling pathway and therapeutic targets

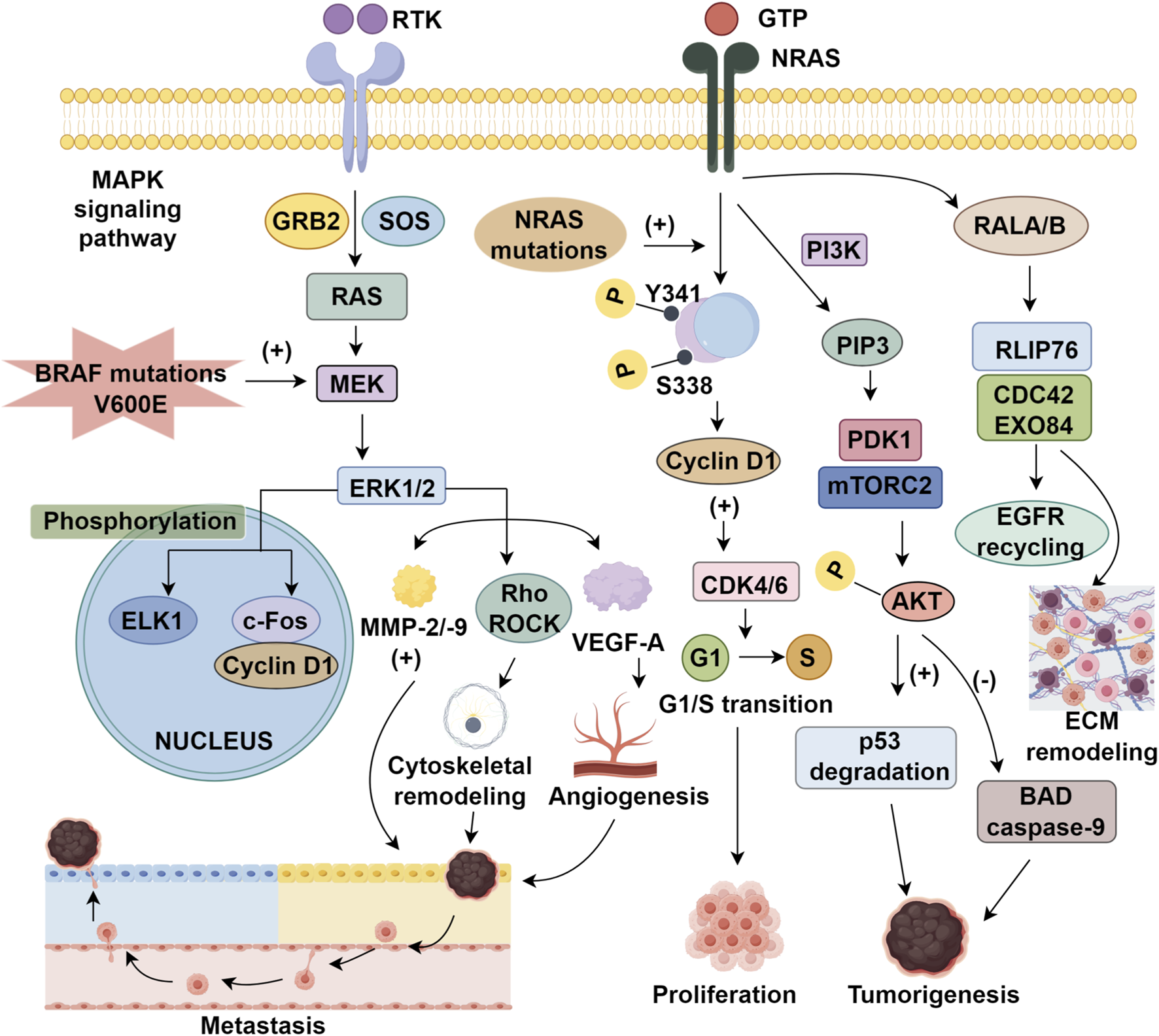

Aberrant activation of the MAPK cascade is tightly linked to melanoma initiation and proliferation and may further promote metastatic competence through downstream effectors (Wellbrock and Arozarena, 2016). Signaling is triggered by RTK dimerization, RAS activation via GRB2/SOS, and stepwise phosphorylation along the RAF–MEK–ERK axis (Favre, 2014; Zhang et al., 2022; Savoia et al., 2019). Nuclear ERK1/2 phosphorylates transcription factors (ELK1) and induces proto-oncogenic programs, including c-Fos and cyclin D1. BRAF mutations drive constitutive MEK/ERK signaling, providing a strong rationale for targeted therapy (Maik-Rachline et al., 2019; Arkenau et al., 2011). Clinically, BRAF inhibitors (vemurafenib, dabrafenib) and MEK inhibition (trametinib) outperform chemotherapy (Chapman et al., 2017). However, resistance commonly arises through NRAS activation and MAPK pathway reactivation via multiple routes, including RTK upregulation (EGFR, PDGFRβ), BRAF splice variants, MEK1/2 mutations, MAP3K8 (COT) overexpression, and NF1 loss (Klein et al., 2008). Epigenetic silencing of DUSP and NF1, together with miRNA-mediated suppression of ERK inhibitors (SPRY, SPRED), can further amplify MAPK output (Ablain et al., 2021; Masliah-Planchon et al., 2016). Although the causal link between MAPK hyperactivation and metastasis remains under active investigation, ERK-dependent induction of MMP-2/-9, Rho/ROCK-driven cytoskeletal remodeling, and VEGF-A–mediated angiogenesis have been mechanistically associated with enhanced invasion. Accordingly, emerging strategies emphasize combination regimens that co-target BRAF/MEK and complementary pathways (imatinib) to counter resistance and reshape the tumor microenvironment (Aseervatham, 2020; Rager et al., 2022).

2.2 BRAF kinase alterations and targeted therapy in malignant melanoma

The RAF kinase family (ARAF, BRAF, and RAF1) constitutes a central axis of the MAPK pathway, with BRAF acting as a principal oncogenic driver due to its frequent mutational activation (Zhang et al., 2023; Braicu et al., 2019). Notably, the V600E mutation enables MEK phosphorylation independent of RAS signaling, triggering sustained ERK pathway activity (Tian and Guo, 2020). The V600E substitution disrupts autoinhibitory control at the ATP-binding site, enabling constitutive MEK phosphorylation independent of upstream RAS input and sustaining ERK-driven tumorigenesis via cyclin D1 upregulation and CDK4 activation (Hirai et al., 2021). Intriguingly, BRAF mutations are less prevalent in East Asian populations, a disparity not fully explained by ultraviolet exposure, as BRAF V600E is not a UV signature mutation (Ren et al., 2022; Mao et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2022). This difference likely reflects the higher proportion of acral and mucosal melanomas in these populations—subtypes typically exhibiting lower BRAF mutation rates and relative enrichment of KIT and NRAS alterations—along with ethnic-specific germline variation and distinct tumor mutational burdens (Ren et al., 2022; Hida et al., 2024). Mechanistically, the V600E substitution disrupts BRAF autoinhibition within the ATP-binding region, leading to constitutive ERK pathway activation that promotes proliferation and apoptosis resistance, thereby providing a strong rationale for selective BRAF inhibition (Maloney et al., 2021). Despite the clinical activity of selective BRAF inhibitors (vemurafenib and dabrafenib), paradoxical ERK activation remains a major limitation. Whereas BRAF^V600E signals largely as a RAS-independent monomer, wild-type BRAF and RAF1 (CRAF) typically require RAS-driven dimerization for activation (Poulikakos et al., 2010; Girotti et al., 2015; Cox and Der, 2012). In RAS-activated settings, BRAF inhibitors bind one RAF protomer within a dimer but allosterically hinder engagement of the second protomer, generating a hemi-bound dimer that paradoxically enhances MEK/ERK signaling (Sievert et al., 2013; Vasta et al., 2023). This mechanism is implicated in characteristic cutaneous toxicities, including keratoacanthomas and cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas (Adelmann et al., 2016; Chu et al., 2012). Accordingly, MEK co-inhibition has become a cornerstone of BRAF-targeted therapy by suppressing ERK reactivation, improving tolerability and therapeutic durability (Eroglu and Ribas, 2016; Kakadia et al., 2018; McArthur, 2015). This combination strategy exemplifies the necessity of mechanistic insight in guiding rational therapeutic design and minimizing adverse events in BRAF-mutant melanoma.

2.3 MEK inhibitors for malignant melanoma

MEK1/2, dual-specificity kinases that phosphorylate ERK1/2 at the conserved Thr-Glu-Tyr motif, represent a central node in MAPK signaling (Cargnello and Roux, 2011; Barbosa et al., 2021). BRAF V600E-mutant melanomas are typically MEK-dependent and thus sensitive to MEK inhibition, whereas NRAS/KRAS-driven tumors frequently bypass this dependency through compensatory PI3K/AKT activation, limiting monotherapy efficacy (Kakadia et al., 2018; Luebker and Koepsell, 2019; Posch et al., 2013). Allosteric MEK inhibitors reconfigure the ATP-binding cleft, suppressing ERK phosphorylation, inducing G1/S arrest, and initiating mitochondrial apoptosis. BRAF V600E cell lines exhibit reduced IC50 values versus wild-type, reinforcing their clinical translatability (Solit et al., 2006; Gonzalez-Del Pino et al., 2021). First-generation MEK inhibitors (CI-1040) established druggability but were constrained by poor stability (Montagut and Settleman, 2009); the second-generation agent PD0325901 improved potency (including Val211 engagement) yet was curtailed by dose-limiting toxicity (Boasberg et al., 2011). These culminated in trametinib, a third-generation FDA-approved MEK1/2 inhibitor that blocks ERK activation, induces G1 arrest, and suppresses tumor growth in vivo (Gilmartin et al., 2011). In BRAF inhibitor-naïve patients, trametinib showed superior response rates (33%) relative to pretreated (17%) or BRAF wild-type (10%) cohorts (Infante et al., 2012; Falchook et al., 2012). Nonetheless, resistance—via ERK reactivation, PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling, and immunosuppressive remodeling—has driven combination strategies, including pairing with PD-1 blockade (Liu et al., 2025; Zhong et al., 2022; Deken et al., 2016). Second-generation MEK inhibitors, such as selumetinib (AZD6244), suppress ERK1/2 phosphorylation by stabilizing an inactive MEK conformation through interaction with the αC-helix. Although they show activity in BRAF-mutant tumors, combinations with docetaxel can yield genotype-dependent outcomes, with synergy in BRAF-mutant settings but heightened toxicity in NRAS-mutant cells (Catalanotti et al., 2013; Patel et al., 2013; Gupta et al., 2014; Kim and Patel, 2014). Cobimetinib, another FDA-approved MEK1/2 inhibitor, reduces paradoxical ERK reactivation when combined with vemurafenib (Ascierto et al., 2021; Abdel-Wahab et al., 2014). These findings highlight the value of vertical MAPK blockade and underscore the necessity for mutation-guided combinations in melanoma treatment.

2.4 Imatinib mesylate targets KIT pathway

Imatinib mesylate marked a pivotal advancement in precision oncology, especially for melanomas driven by KIT mutations (Jung et al., 2022). As the inaugural KIT/PDGFRA tyrosine kinase inhibitor approved by the FDA (Zhou et al., 2024), imatinib acts by obstructing the ATP-binding domain (residues Asp810–Val814–Val817), thereby disrupting pathological KIT signaling. Its efficacy is notably superior in tumors harboring KIT exon 11 mutations, where it shows enhanced selectivity over the wild-type counterpart (Guo et al., 2011). Importantly, imatinib is not the only KIT inhibitor evaluated in melanoma; second-generation agents, including nilotinib, dasatinib, and sunitinib, have shown clinical activity across multiple KIT mutation subtypes and resistance contexts (Pham et al., 2020; Steeb et al., 2021; Kaveti et al., 2025; Larkin et al., 2024; Guo et al., 2017). Nilotinib and sunitinib exhibit greater potency against selected imatinib-resistant variants, whereas dasatinib provides broader coverage through multi-kinase inhibition (Kalinsky et al., 2017; Serrano et al., 2019). These agents are being assessed as monotherapies and in combination regimens to improve outcomes in KIT-driven melanoma (Pham et al., 2020; Kaveti et al., 2025). However, accumulating evidence suggests that KIT inhibition alone is frequently undermined by pathway redundancy and escape signaling. Consequently, rational combinations—particularly dual KIT and MEK inhibition—are gaining traction, with early clinical evaluation underway (NCT04598009) to deepen MAPK suppression and curb compensatory reactivation.

3 Rationale and paradigm of targeted combination therapy

3.1 BRAF and MEK inhibitor combination

Although BRAF inhibitors have substantially improved outcomes in BRAF-mutant melanoma, their clinical benefit is constrained by dose-limiting toxicities, limited response durability, and the near-universal emergence of acquired resistance, motivating combination-based strategies (Zhong et al., 2022; Liu et al., 2017). A dominant resistance mechanism is MAPK pathway reactivation via multiple molecular adaptations, including EGFR upregulation with RTK-mediated feedback–driven ERK reactivation (Saei and Eichhorn, 2019; Ji et al., 2021); paradoxical ERK activation that enables outgrowth of RAS-mutant subclones; epigenetic NF1 inactivation with impaired RAS-GTPase function; expression of BRAF p61 splice isoforms that promote RAF autophosphorylation; activating alterations in MEK1/2 or MLK1–4 that support bypass signaling (Tse and Verkhivker, 2016; Bartnik et al., 2019; Czarnecka et al., 2020); and immune editing associated with altered cytokine outputs and increased CD8+ T-cell infiltration (Haas et al., 2021; Grecea-Balaj et al., 2025). Mechanistically, resistance is frequently maintained by RAF homodimerization that preserves MAPK signaling under drug pressure and by aberrant ERK feedback loops that reconstitute oncogenic signaling within the tumor microenvironment (Sievert et al., 2013; Meierjohann, 2017). Dual blockade more effectively suppresses ERK phosphorylation at its activation residues (Thr202/Tyr204), thereby enhancing apoptosis and delaying resistance (McArthur, 2015; Su et al., 2012). In line with this model, genomic profiling of resistant populations suggests a synthetic-lethal vulnerability characterized by heightened sensitivity to MEK inhibition, consistent with clinical observations that combination therapy prolongs median PFS and reduces resistance incidence (Abdel-Rahman et al., 2016).

3.2 BRAF and MEK inhibitor in clinical

The Phase III coBRIM trial (NCT01689519) demonstrated that vemurafenib plus cobimetinib significantly outperformed vemurafenib monotherapy in BRAF V600–mutant melanoma, with improved efficacy and a manageable safety profile—76% of grade 3–4 toxicities occurred early in treatment, and MEK-mediated ERK suppression led to a 60% reduction in acute kidney injury incidence (Ascierto et al., 2016; Teuma et al., 2017). The COMBI-d study similarly confirmed the efficacy of dabrafenib plus trametinib, enhancing PFS and ORR (Long et al., 2014). Mechanistically, trametinib inhibits MEK1/2 and dampens ERK reactivation, while dabrafenib induces BIM and suppresses cyclin D1, though febrile adverse events were more frequent (Robert et al., 2016). Current melanoma treatment strategies prioritize rational combinations to enhance pharmacodynamic synergy while minimizing toxicity (Smalley et al., 2016). These include modulation of BRAF/MEK dosing to reduce severe toxicities, vertical co-targeting of bypass nodes such as PI3Kβ/δ or AKT (NCT01941927), and horizontal integration with PD-1 blockade (NCT02967692) (Luke et al., 2017). While encorafenib and binimetinib, second-generation BRAF and MEK inhibitors, have been approved for BRAF V600E/K-mutant melanoma, they are not indicated for NRAS- or wild-type tumors (Baik et al., 2024). According to Schadendorf (2025), their use remains confined to select genomic subsets, and broad application should be approached with caution. These findings underscore the necessity of genomic stratification to guide therapy selection and maximize clinical benefit.

4 Molecular mechanisms and signal transduction features of NRAS-driven oncogenic networks in malignant melanoma

The RAS gene family—NRAS, KRAS, and HRAS—encodes small GTPases that function as binary molecular switches, cycling between GTP-bound active and GDP-bound inactive states, regulated by GEFs and GAPs (Tsai et al., 2015; Hobbs et al., 2016). In malignant melanoma, NRAS mutations—most frequently at codon 61—result in constitutive GTP-loading, driving sustained oncogenic signaling and conferring a more aggressive phenotype than BRAF-mutant or wild-type melanomas (Lally et al., 2022; Zablocka et al., 2023). NRAS orchestrates tumorigenesis through three principal effector pathways. First, MAPK cascade activation via RAF1 (formerly CRAF) homodimers phosphorylated at S338/Y341 promotes cyclin D1 upregulation and CDK4/6 activation, facilitating G1/S transition (Wang P. et al., 2023; Wee and Wang, 2017). Second, PI3K–AKT–mTOR signaling is amplified through PIP3-mediated recruitment of PDK1 and mTORC2, leading to AKT phosphorylation, suppression of apoptotic mediators (BAD, caspase-9), p53 degradation, and enhanced translational machinery (Peng et al., 2022). Third, RAL GTPase activation stimulates EGFR recycling and extracellular matrix (ECM) remodeling via RLIP76 and CDC42/EXO84, promoting invasiveness (Zipfel et al., 2010; Falsetti et al., 2007) (Figure 1). This multifaceted signaling confers intrinsic resistance to BRAF inhibitors and limits MEK inhibitor efficacy (Phadke and Smalley, 2023). Accordingly, therapeutic strategies must address network redundancy and crosstalk. Although MEK inhibitors like binimetinib and pimasertib have demonstrated only modest activity, with limited progression-free survival (PFS) and no overall survival (OS) advantage (Dummer et al., 2017), combinatorial regimens offer a promising alternative. Notably, MEK–CDK4/6 co-inhibition has improved ORR in Phase II trials, delaying resistance emergence (Lebbé et al., 2020). Given these limitations, PD-1 immune checkpoint inhibitors have been endorsed by NCCN and ESMO as frontline therapies for NRAS-mutant melanoma (Michielin et al., 2019; Swetter et al., 2024). Yet, interregional variability complicates clinical generalizability. European cohorts report ORRs 28% higher in NRAS-mutant tumors versus wild-type (Jaeger et al., 2023), whereas Asian studies reveal attenuated responses across cutaneous and extracutaneous subtypes (Zhou et al., 2021). These disparities underscore the importance of molecular and ethnic context in therapeutic design. Collectively, NRAS-mutant melanoma exemplifies the challenges of targeting non-ligandable oncoproteins and the need for precision oncology paradigms integrating immune modulation with multi-node pathway inhibition, tailored to distinct genetic architectures.

FIGURE 1

The MAPK signaling pathway and therapeutic targets in melanoma.

5 Potential targets focusing on RAS pathway

5.1 Monotherapy and FTIs in NRAS-mutant melanoma

Efforts to develop targeted therapies for melanoma harboring NRAS mutations encounter significant molecular impediments. In contrast to the structurally defined drug-binding pocket observed in BRAF V600 alterations, the canonical NRAS mutation sites (such as Q61R/L) present a major obstacle due to the absence of suitable ligandable conformations within their nucleotide-binding regions (Phadke and Smalley, 2023; Muñoz-Couselo et al., 2017). The GTP-binding cleft is characterized by restrictive geometry and exceptionally high-affinity interactions at the picomolar scale, which collectively render conventional competitive inhibition strategies largely futile (Mattox et al., 2019). Moreover, approaches attempting to directly antagonize GTP itself have consistently yielded negative outcomes (Ryan and Corcoran, 2018). Historically, research emphasis shifted toward interfering with RAS-associated post-translational modifications. For instance, farnesyltransferase inhibitors were designed to hinder the membrane anchoring of p21RAS by blocking farnesylation at its C-terminal cysteine residue. Nevertheless, clinical trials evaluating this strategy produced disappointing outcomes; in a Phase II cohort involving 14 patients with NRAS-mutant melanoma, no objective therapeutic responses were observed, resulting in early discontinuation of the trial and highlighting the divergence between mechanistic rationale and actual clinical benefit (Gajewski et al., 2012). Contemporary investigations have broadened toward cross-target strategies exemplified by sotorasib, an allosteric KRAS G12C inhibitor that stabilizes KRAS in its inactive state and has demonstrated substantial clinical activity across multiple solid tumors. Although its utility in NRAS G12C–mutant melanoma remains speculative, the mechanistic rationale warrants systematic clinical evaluation to define its translational potential (Hong et al., 2020).

5.2 RAF-MAPK and ERK pathway inhibitors

Given the intrinsic challenges of directly targeting NRAS—stemming from its high-affinity GTP binding and limited druggable pockets—therapeutic development in NRAS-mutant melanoma has largely pivoted to downstream inhibition within the RAF–MAPK cascade (Wang et al., 2025; Fernandez et al., 2023). Preclinical work indicates that dual suppression of BRAF and RAF1 can significantly restrain tumor growth, providing a mechanistic rationale for pan-RAF inhibition (Karoulia et al., 2016; Vakana et al., 2017). Clinically, belvarafenib (RG6185/HM95573) has shown only modest activity in early-phase studies (Yen et al., 2021). By contrast, the MEK1/2 inhibitor tunlametinib (HL-085) has reported more favorable outcomes, achieving a 35% objective response rate (ORR) that increased to 39% in patients refractory to prior immunotherapies, and outperforming binimetinib in cross-study comparisons (Wang X. et al., 2023). Targeting ERK1/2, the terminal effectors of MAPK signaling, provides an alternative axis. Although preclinical ERK inhibitors such as VX-11e can suppress feedback-driven pathway reactivation (Adam et al., 2020), clinical activity has thus far been limited, with ulixertinib achieving a 13.5% ORR (Mendzelevski et al., 2018). Consequently, combination approaches co-targeting MEK and ERK are being pursued to blunt adaptive resistance and improve response durability (Adam et al., 2020). Beyond vertical pathway blockade, pan-RAS(ON) inhibitors represent a conceptual advance. In contrast to earlier strategies that failed clinically (farnesyltransferase inhibition), emerging agents such as RMC-7977 and RMC-6236 are designed to engage the switch II pocket of GTP-loaded RAS, thereby interrupting oncogenic signaling at its source (Holderfield et al., 2024; Drosten and Barbacid, 2025). RMC-7977 has been reported to induce tumor regression in NRAS- and KRAS-mutant preclinical models, including melanoma xenografts (Anastacio Da Costa Carvalho et al., 2025). RMC-6236 is undergoing clinical evaluation (NCT05379985) and has shown potent MAPK suppression with early partial responses in heavily pretreated patients (Filis et al., 2025). By targeting active RAS, these agents may mitigate the feedback reactivation that often undermines MEK-directed therapy and could offer improved therapeutic durability. As clinical development matures, pan-RAS(ON) inhibitors may reshape treatment paradigms for NRAS-driven melanoma (Supplementary Table S1).

5.3 Novel combination strategies for NRAS-mutant melanoma

Monotherapies have shown limited efficacy in NRAS-mutant melanoma due to complex downstream signaling networks and innate resistance mechanisms. While pan-RAF inhibitors are constrained by feedback-mediated MAPK reactivation, their combination with trametinib has yielded improved outcomes, as evidenced by a 40% objective response rate (ORR) in trial NCT03284502 and a 46.7% ORR with naporafenib plus trametinib (Atefi et al., 2015; de Braud et al., 2023). In contrast, dual inhibition strategies targeting the PI3K/AKT axis have produced inconsistent results. Alpelisib plus binimetinib achieved 20% ORR (Bartnik et al., 2019), whereas trametinib with GSK2141795 failed to elicit clinical responses in a Phase I study (NCT01941927) (Algazi et al., 2018), highlighting the limitations of non-stratified combination therapies. Conversely, biomarker-guided approaches have demonstrated enhanced efficacy. NRAS-mutant tumors with CDKN2A, CDK4, or CCND1 alterations exhibited increased sensitivity to ribociclib combined with binimetinib, underscoring the relevance of precision medicine (Kinsey et al., 2025). Parallel strategies incorporating autophagy inhibition have gained traction; clinical trial NCT03979651 is evaluating hydroxychloroquine as an adjunct to MEK inhibition to overcome resistance (Mehnert et al., 2022). Additionally, molecular profiling reveals overexpression of RTKs—particularly Axl, ERBB2, c-MET, and EGFR—in NRAS-driven melanoma, implicating these receptors in drug resistance (Sabbah et al., 2021; Robinson et al., 2017). Accordingly, RTK-targeted combinations such as sorafenib and tivantinib have shown superior efficacy in NRAS-mutant tumors relative to wild-type controls (Rager et al., 2022; Puzanov et al., 2015; Fedorenko et al., 2013). These findings reinforce the necessity of genetically informed, multi-targeted strategies to address adaptive resistance and optimize therapeutic outcomes in this biologically complex melanoma subtype.

6 Conclusion

Despite significant advances in targeted and immunotherapy, malignant melanoma continues to present substantial clinical challenges, particularly in treatment-resistant and NRAS-mutant subtypes. Monotherapies targeting MAPK signaling, including BRAF and MEK inhibitors, have provided transient benefits but are undermined by adaptive resistance mechanisms such as pathway reactivation, compensatory signaling loops, and immunosuppressive remodeling. In NRAS-mutant melanoma, the therapeutic landscape is further complicated by the lack of direct RAS inhibitors and the limited efficacy of MEK blockade alone. Combination therapies—integrating MEK inhibitors with CDK4/6 inhibitors, autophagy modulators, or immune checkpoint inhibitors—have emerged as promising avenues, especially in genetically defined subgroups. Moreover, the identification of co-occurring alterations in PI3K/AKT, RTKs, and cell-cycle regulators has refined patient stratification and enabled rational design of biomarker-driven regimens. The therapeutic efficacy of KIT inhibitors in specific molecular contexts underscores the broader potential of precision-guided interventions. Moving forward, multi-targeted combination strategies that concurrently disrupt oncogenic signaling and reshape the tumor immune microenvironment are poised to redefine melanoma treatment paradigms. Continued integration of genomic, epigenetic, and immunologic profiling will be essential to overcome resistance and extend durable responses in this biologically diverse malignancy.

Statements

Author contributions

XF: Writing – original draft. SW: Writing – original draft. SF: Writing – review and editing, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication.

Acknowledgments

All authors appreciate the supports from the Affiliated Hospital of Shaoxing University and The Affiliated Hospital of Hangzhou Normal University.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcell.2025.1723066/full#supplementary-material

References

1

Abdel-Rahman O. ElHalawani H. Ahmed H. (2016). Doublet BRAF/MEK inhibition versus single-agent BRAF inhibition in the management of BRAF-mutant advanced melanoma, biological rationale and meta-analysis of published data. Clin. Transl. Oncol.18, 848–858. 10.1007/s12094-015-1438-0

2

Abdel-Wahab O. Klimek V. M. Gaskell A. A. Viale A. Cheng D. Kim E. et al (2014). Efficacy of intermittent combined RAF and MEK inhibition in a patient with concurrent BRAF- and NRAS-mutant malignancies. Cancer Discov.4, 538–545. 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-13-1038

3

Ablain J. Liu S. Moriceau G. Lo R. S. Zon L. I. (2021). SPRED1 deletion confers resistance to MAPK inhibition in melanoma. J. Exp. Med.218, e20201097. 10.1084/jem.20201097

4

Adam C. Fusi L. Weiss N. Goller S. G. Meder K. Frings V. G. et al (2020). Efficient suppression of NRAS-driven melanoma by Co-Inhibition of ERK1/2 and ERK5 MAPK pathways. J. Invest Dermatol140, 2455–2465.e2410. 10.1016/j.jid.2020.03.972

5

Adelmann C. H. Ching G. Du L. Saporito R. C. Bansal V. Pence L. J. et al (2016). Comparative profiles of BRAF inhibitors: the paradox index as a predictor of clinical toxicity. Oncotarget7, 30453–30460. 10.18632/oncotarget.8351

6

Algazi A. P. Esteve-Puig R. Nosrati A. Hinds B. Hobbs-Muthukumar A. Nandoskar P. et al (2018). Dual MEK/AKT inhibition with trametinib and GSK2141795 does not yield clinical benefit in metastatic NRAS-mutant and wild-type melanoma. Pigment. Cell Melanoma Res.31, 110–114. 10.1111/pcmr.12644

7

Anastacio Da Costa Carvalho L. Tovbis Shifrin N. Phadke M. S. Emmons M. F. Pechuan-Jorge X. Mbuga F. et al (2025). RAS(ON) multi-selective inhibition drives antitumor immunity in preclinical models of NRAS-mutant melanoma. Cancer Immunol. Res., OF1–OF17. 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-25-0744

8

Arkenau H. T. Kefford R. Long G. V. (2011). Targeting BRAF for patients with melanoma. Br. J. Cancer104, 392–398. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6606030

9

Ascierto P. A. McArthur G. A. Dréno B. Atkinson V. Liszkay G. Di Giacomo A. M. et al (2016). Cobimetinib combined with vemurafenib in advanced BRAF(V600)-mutant melanoma (coBRIM): updated efficacy results from a randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol.17, 1248–1260. 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30122-X

10

Ascierto P. A. Dréno B. Larkin J. Ribas A. Liszkay G. Maio M. et al (2021). 5-Year outcomes with cobimetinib plus vemurafenib in BRAFV600 mutation-positive advanced melanoma: extended Follow-up of the coBRIM study. Clin. Cancer Res.27, 5225–5235. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-21-0809

11

Aseervatham J. (2020). Cytoskeletal remodeling in cancer. Biol. (Basel)9, 385. 10.3390/biology9110385

12

Atefi M. Titz B. Avramis E. Ng C. Wong D. J. Lassen A. et al (2015). Combination of pan-RAF and MEK inhibitors in NRAS mutant melanoma. Mol. Cancer14, 27. 10.1186/s12943-015-0293-5

13

Baik C. Cheng M. L. Dietrich M. Gray J. E. Karim N. A. (2024). A practical review of encorafenib and binimetinib therapy management in patients with BRAF V600E-Mutant metastatic non-small cell lung cancer. Adv. Ther.41, 2586–2605. 10.1007/s12325-024-02839-4

14

Barbosa R. Acevedo L. A. Marmorstein R. (2021). The MEK/ERK network as a therapeutic target in human cancer. Mol. Cancer Res.19, 361–374. 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-20-0687

15

Bartnik E. Fiedorowicz M. AmjnjoO C. (2019). Mechanisms of melanoma resistance to treatment with BRAF and MEK inhibitors. arXiv69, 133–141.

16

Boasberg P. D. Redfern C. H. Daniels G. A. Bodkin D. Garrett C. R. Ricart A. D. (2011). Pilot study of PD-0325901 in previously treated patients with advanced melanoma, breast cancer, and colon cancer. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol.68, 547–552. 10.1007/s00280-011-1620-1

17

Braicu C. Buse M. Busuioc C. Drula R. Gulei D. Raduly L. et al (2019). A comprehensive review on MAPK: a promising therapeutic target in cancer. Cancers (Basel)11, 1618. 10.3390/cancers11101618

18

Cargnello M. Roux P. P. (2011). Activation and function of the MAPKs and their substrates, the MAPK-activated protein kinases. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev.75, 50–83. 10.1128/MMBR.00031-10

19

Catalanotti F. Solit D. B. Pulitzer M. P. Berger M. F. Scott S. N. Iyriboz T. et al (2013). Phase II trial of MEK inhibitor selumetinib (AZD6244, ARRY-142886) in patients with BRAFV600E/K-mutated melanoma. Clin. Cancer Res.19, 2257–2264. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-3476

20

Chapman P. B. Robert C. Larkin J. Haanen J. B. Ribas A. Hogg D. et al (2017). Vemurafenib in patients with BRAFV600 mutation-positive metastatic melanoma: final overall survival results of the randomized BRIM-3 study. Ann. Oncol.28, 2581–2587. 10.1093/annonc/mdx339

21

Chu E. Y. Wanat K. A. Miller C. J. Amaravadi R. K. Fecher L. A. Brose M. S. et al (2012). Diverse cutaneous side effects associated with BRAF inhibitor therapy: a clinicopathologic study. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol67, 1265–1272. 10.1016/j.jaad.2012.04.008

22

Cosgarea I. Ugurel S. Sucker A. Livingstone E. Zimmer L. Ziemer M. et al (2017). Targeted next generation sequencing of mucosal melanomas identifies frequent NF1 and RAS mutations. Oncotarget8, 40683–40692. 10.18632/oncotarget.16542

23

Cox A. D. Der C. J. (2012). The RAF inhibitor paradox revisited. Cancer Cell21, 147–149. 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.01.017

24

Czarnecka A. M. Bartnik E. Fiedorowicz M. Rutkowski P. (2020). Targeted therapy in melanoma and mechanisms of resistance. Int. J. Mol. Sci.21, 4576. 10.3390/ijms21134576

25

Davis L. E. Shalin S. C. Tackett A. J. (2019). Current state of melanoma diagnosis and treatment. Cancer Biol. Ther.20, 1366–1379. 10.1080/15384047.2019.1640032

26

de Braud F. Dooms C. Heist R. S. Lebbe C. Wermke M. Gazzah A. et al (2023). Initial evidence for the efficacy of naporafenib in combination with trametinib in NRAS-mutant melanoma: results from the expansion arm of a phase Ib, open-label study. J. Clin. Oncol.41, 2651–2660. 10.1200/JCO.22.02018

27

Deken M. A. Gadiot J. Jordanova E. S. Lacroix R. van Gool M. Kroon P. et al (2016). Targeting the MAPK and PI3K pathways in combination with PD1 blockade in melanoma. Oncoimmunology5, e1238557. 10.1080/2162402X.2016.1238557

28

Drosten M. Barbacid M. (2025). The rapidly growing landscape of RAS inhibitors: from selective allele blockade to broad inhibition strategies. Mol. Oncol.19, 2991–2995. 10.1002/1878-0261.70149

29

Dummer R. Schadendorf D. Ascierto P. A. Arance A. Dutriaux C. Di Giacomo A. M. et al (2017). Binimetinib versus dacarbazine in patients with advanced NRAS-mutant melanoma (NEMO): a multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol.18, 435–445. 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30180-8

30

Eroglu Z. Ozgun A. (2018). Updates and challenges on treatment with BRAF/MEK-inhibitors in melanoma. Expert Opin. Orphan Drugs6, 545–551. 10.1080/21678707.2018.1512402

31

Eroglu Z. Ribas A. (2016). Combination therapy with BRAF and MEK inhibitors for melanoma: latest evidence and place in therapy. Ther. Adv. Med. Oncol.8, 48–56. 10.1177/1758834015616934

32

Falchook G. S. Lewis K. D. Infante J. R. Gordon M. S. Vogelzang N. J. DeMarini D. J. et al (2012). Activity of the oral MEK inhibitor trametinib in patients with advanced melanoma: a phase 1 dose-escalation trial. Lancet Oncol.13, 782–789. 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70269-3

33

Falsetti S. C. Wang D. A. Peng H. Carrico D. Cox A. D. Der C. J. et al (2007). Geranylgeranyltransferase I inhibitors target RalB to inhibit anchorage-dependent growth and induce apoptosis and RalA to inhibit anchorage-independent growth. Mol. Cell Biol.27, 8003–8014. 10.1128/MCB.00057-07

34

Favre G. (2014). Future targeting of the RAS/RAF/MEK/ERK signaling pathway in oncology: the example of melanoma. Bull. Acad. Natl. Med.198, 321–336.

35

Fedorenko I. V. Gibney G. T. Smalley K. S. (2013). NRAS mutant melanoma: biological behavior and future strategies for therapeutic management. Oncogene32, 3009–3018. 10.1038/onc.2012.453

36

Fernandez M. F. Choi J. Sosman J. (2023). New approaches to targeted therapy in melanoma. Cancers (Basel)15, 3224. 10.3390/cancers15123224

37

Ferrucci P. F. Di Giacomo A. M. Del Vecchio M. Atkinson V. Schmidt H. Schachter J. et al (2020). KEYNOTE-022 part 3: a randomized, double-blind, phase 2 study of pembrolizumab, dabrafenib, and trametinib in BRAF-mutant melanoma. J. Immunother. Cancer8, e001806. 10.1136/jitc-2020-001806

38

Filis P. Salgkamis D. Matikas A. Zerdes IJDDT (2025). Breakthrough in RAS targeting with pan-RAS (ON) inhibitors RMC-7977 and RMC-6236. Drug Discov. Today30, 104250. 10.1016/j.drudis.2024.104250

39

Force L. M. Kocarnik J. M. May M. L. Bhangdia K. Crist A. Penberthy L. et al (2025). The global, regional, and national burden of cancer, 1990-2023, with forecasts to 2050: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2023. Lancet406, 1565–1586. 10.1016/s0140-6736(25)01635-6

40

Gajewski T. F. Salama A. K. Niedzwiecki D. Johnson J. Linette G. Bucher C. et al (2012). Phase II study of the farnesyltransferase inhibitor R115777 in advanced melanoma (CALGB 500104). J. Transl. Med.10, 246. 10.1186/1479-5876-10-246

41

Gilmartin A. G. Bleam M. R. Groy A. Moss K. G. Minthorn E. A. Kulkarni S. G. et al (2011). GSK1120212 (JTP-74057) is an inhibitor of MEK activity and activation with favorable pharmacokinetic properties for sustained in vivo pathway inhibition. Clin. Cancer Res.17, 989–1000. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2200

42

Girotti M. R. Lopes F. Preece N. Niculescu-Duvaz D. Zambon A. Davies L. et al (2015). Paradox-breaking RAF inhibitors that also target SRC are effective in drug-resistant BRAF mutant melanoma. Cancer Cell27, 85–96. 10.1016/j.ccell.2014.11.006

43

Gonzalez-Del Pino G. L. Li K. Park E. Schmoker A. M. Ha B. H. Eck M. J. (2021). Allosteric MEK inhibitors act on BRAF/MEK complexes to block MEK activation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A.118, e2107207118. 10.1073/pnas.2107207118

44

Grecea-Balaj A. M. Soritau O. Brie I. Perde-Schrepler M. Virág P. Todor N. et al (2025). Immune cell–cytokine interplay in NSCLC and melanoma: a pilot longitudinal study of dynamic biomarker interactions. Immuno5, 29. 10.3390/immuno5030029

45

Guhan S. Klebanov N. Tsao H. (2021). Melanoma genomics: a state-of-the-art review of practical clinical applications. Br. J. Dermatol185, 272–281. 10.1111/bjd.20421

46

Guo J. Si L. Kong Y. Flaherty K. T. Xu X. Zhu Y. et al (2011). open-label, single-arm trial of imatinib mesylate in patients with metastatic melanoma harboring c-Kit mutation or amplification. J. Clin. Oncol.29, 2904–2909. 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.9275

47

Guo J. Carvajal R. D. Dummer R. Hauschild A. Daud A. Bastian B. C. et al (2017). Efficacy and safety of nilotinib in patients with KIT-mutated metastatic or inoperable melanoma: final results from the global, single-arm, phase II TEAM trial. Ann. Oncol.28, 1380–1387. 10.1093/annonc/mdx079

48

Gupta A. Love S. Schuh A. Shanyinde M. Larkin J. M. Plummer R. et al (2014). DOC-MEK: a double-blind randomized phase II trial of docetaxel with or without selumetinib in wild-type BRAF advanced melanoma. Ann. Oncol.25, 968–974. 10.1093/annonc/mdu054

49

Haas L. Elewaut A. Gerard C. L. Umkehrer C. Leiendecker L. Pedersen M. et al (2021). Acquired resistance to anti-MAPK targeted therapy confers an immune-evasive tumor microenvironment and cross-resistance to immunotherapy in melanoma. Nat. Cancer2, 693–708. 10.1038/s43018-021-00221-9

50

Haugh A. M. Salama A. K. S. Johnson D. B. (2021). Advanced melanoma: resistance mechanisms to current therapies. Hematol. Oncol. Clin. North Am.35, 111–128. 10.1016/j.hoc.2020.09.005

51

Hida T. Idogawa M. Kato J. Kiniwa Y. Horimoto K. Sato S. et al (2024). Genetic characteristics of cutaneous, acral, and mucosal melanoma in Japan. Cancer Med.13, e70360. 10.1002/cam4.70360

52

Hirai N. Hatanaka Y. Hatanaka K. C. Uno Y. Chiba S. I. Umekage Y. et al (2021). Cyclin-dependent kinase 4 upregulation mediates acquired resistance of dabrafenib plus trametinib in BRAF V600E-mutated lung cancer. Transl. Lung Cancer Res.10, 3737–3744. 10.21037/tlcr-21-415

53

Hobbs G. A. Der C. J. Rossman K. L. (2016). RAS isoforms and mutations in cancer at a glance. J. Cell Sci.129, 1287–1292. 10.1242/jcs.182873

54

Holderfield M. Lee B. J. Jiang J. Tomlinson A. Seamon K. J. Mira A. et al (2024). Concurrent inhibition of oncogenic and wild-type RAS-GTP for cancer therapy. Nature629, 919–926. 10.1038/s41586-024-07205-6

55

Hong D. S. Fakih M. G. Strickler J. H. Desai J. Durm G. A. Shapiro G. I. et al (2020). KRAS(G12C) inhibition with sotorasib in advanced solid tumors. N. Engl. J. Med.383, 1207–1217. 10.1056/NEJMoa1917239

56

Infante J. R. Fecher L. A. Falchook G. S. Nallapareddy S. Gordon M. S. Becerra C. et al (2012). Safety, pharmacokinetic, pharmacodynamic, and efficacy data for the oral MEK inhibitor trametinib: a phase 1 dose-escalation trial. Lancet Oncol.13, 773–781. 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70270-X

57

Jaeger Z. J. Raval N. S. Maverakis N. K. A. Chen D. Y. Ansstas G. Hardi A. et al (2023). Objective response to immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy in NRAS-mutant melanoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Med. (Lausanne)10, 1090737. 10.3389/fmed.2023.1090737

58

Ji Z. Njauw C. N. Guhan S. Kumar R. Reddy B. Rajadurai A. et al (2021). Loss of ACK1 upregulates EGFR and mediates resistance to BRAF inhibition. J. Invest Dermatol141, 1317–1324.e1311. 10.1016/j.jid.2020.06.041

59

Jung S. Armstrong E. Wei A. Z. Ye F. Lee A. Carlino M. S. et al (2022). Clinical and genomic correlates of imatinib response in melanomas with KIT alterations. Br. J. Cancer127, 1726–1732. 10.1038/s41416-022-01942-z

60

Kakadia S. Yarlagadda N. Awad R. Kundranda M. Niu J. Naraev B. et al (2018). Mechanisms of resistance to BRAF and MEK inhibitors and clinical update of US food and drug Administration-approved targeted therapy in advanced melanoma. Onco Targets Ther.11, 7095–7107. 10.2147/OTT.S182721

61

Kalinsky K. Lee S. Rubin K. M. Lawrence D. P. Iafrarte A. J. Borger D. R. et al (2017). A phase 2 trial of dasatinib in patients with locally advanced or stage IV mucosal, acral, or vulvovaginal melanoma: a trial of the ECOG-ACRIN cancer research group (E2607). Cancer123, 2688–2697. 10.1002/cncr.30663

62

Karoulia Z. Wu Y. Ahmed T. A. Xin Q. Bollard J. Krepler C. et al (2016). An integrated model of RAF inhibitor action predicts inhibitor activity against oncogenic BRAF signaling. Cancer Cell30, 501–503. 10.1016/j.ccell.2016.08.008

63

Kaveti A. Sullivan R. J. Tsao H. (2025). KIT-mutant melanoma: understanding the pathway to personalized therapy. Cancers (Basel)17, 3644. 10.3390/cancers17223644

64

Kim H. J. Kim Y. H. (2024). Molecular frontiers in melanoma: pathogenesis, diagnosis, and therapeutic advances. Int. J. Mol. Sci.25, 2984. 10.3390/ijms25052984

65

Kim D. W. Patel S. P. (2014). Profile of selumetinib and its potential in the treatment of melanoma. Onco Targets Ther.7, 1631–1639. 10.2147/OTT.S51596

66

Kim K. B. Kefford R. Pavlick A. C. Infante J. R. Ribas A. Sosman J. A. et al (2013). Phase II study of the MEK1/MEK2 inhibitor trametinib in patients with metastatic BRAF-mutant cutaneous melanoma previously treated with or without a BRAF inhibitor. J. Clin. Oncol.31, 482–489. 10.1200/JCO.2012.43.5966

67

Kinsey C. G. Camolotto S. A. Boespflug A. M. Guillen K. P. Foth M. Truong A. et al (2025). Author correction: protective autophagy elicited by RAF→MEK→ERK inhibition suggests a treatment strategy for RAS-driven cancers. Nat. Med.31, 2069. 10.1038/s41591-025-03713-8

68

Klein R. M. Spofford L. S. Abel E. V. Ortiz A. Aplin A. E. (2008). B-RAF regulation of Rnd3 participates in actin cytoskeletal and focal adhesion organization. Mol. Biol. Cell19, 498–508. 10.1091/mbc.e07-09-0895

69

Lally S. E. Milman T. Orloff M. Dalvin L. A. Eberhart C. G. Heaphy C. M. et al (2022). Mutational landscape and outcomes of conjunctival melanoma in 101 patients. Ophthalmology129, 679–693. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2022.01.016

70

Larkin J. Marais R. Porta N. Gonzalez de Castro D. Parsons L. Messiou C. et al (2024). Nilotinib in KIT-driven advanced melanoma: results from the phase II single-arm NICAM trial. Cell Rep. Med.5, 101435. 10.1016/j.xcrm.2024.101435

71

Lebbé C. Dutriaux C. Lesimple T. Kruit W. Kerger J. Thomas L. et al (2020). Pimasertib versus dacarbazine in patients with unresectable NRAS-mutated cutaneous melanoma: phase II, randomized, controlled trial with crossover. Cancers (Basel)12, 1727. 10.3390/cancers12071727

72

Liu M. Yang X. Liu J. Zhao B. Cai W. Li Y. et al (2017). Efficacy and safety of BRAF inhibition alone versus combined BRAF and MEK inhibition in melanoma: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Oncotarget8, 32258–32269. 10.18632/oncotarget.15632

73

Liu D. Xiao H. Xiang Y. Zhong D. Liu Y. Wang Y. et al (2025). Strategies to overcome PD-1/PD-L1 blockade resistance: focusing on combination with immune checkpoint blockades. J. Cancer16, 3425–3449. 10.7150/jca.108163

74

Long G. V. Stroyakovskiy D. Gogas H. Levchenko E. de Braud F. Larkin J. et al (2014). Combined BRAF and MEK inhibition versus BRAF inhibition alone in melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med.371, 1877–1888. 10.1056/NEJMoa1406037

75

Luebker S. A. Koepsell S. A. (2019). Diverse mechanisms of BRAF inhibitor resistance in melanoma identified in clinical and preclinical studies. Front. Oncol.9, 268. 10.3389/fonc.2019.00268

76

Luke J. J. Flaherty K. T. Ribas A. Long G. V. (2017). Targeted agents and immunotherapies: optimizing outcomes in melanoma. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol.14, 463–482. 10.1038/nrclinonc.2017.43

77

Maik-Rachline G. Hacohen-Lev-Ran A. Seger R. (2019). Nuclear ERK: mechanism of translocation, substrates, and role in cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci.20, 1194. 10.3390/ijms20051194

78

Maloney R. C. Zhang M. Jang H. Nussinov R. (2021). The mechanism of activation of monomeric B-Raf V600E. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J.19, 3349–3363. 10.1016/j.csbj.2021.06.007

79

Mao L. Qi Z. Zhang L. Guo J. Si L. (2021). Immunotherapy in acral and mucosal melanoma: current status and future directions. Front. Immunol.12, 680407. 10.3389/fimmu.2021.680407

80

Masliah-Planchon J. Garinet S. Pasmant E. (2016). RAS-MAPK pathway epigenetic activation in cancer: miRNAs in action. Oncotarget7, 38892–38907. 10.18632/oncotarget.6476

81

Mattox T. E. Chen X. Maxuitenko Y. Y. Keeton A. B. Piazza G. A. (2019). Exploiting RAS nucleotide cycling as a strategy for drugging RAS-driven cancers. Int. J. Mol. Sci.21, 141. 10.3390/ijms21010141

82

McArthur G. A. (2015). Combination therapies to inhibit the RAF/MEK/ERK pathway in melanoma: we are not done yet. Front. Oncol.5, 161. 10.3389/fonc.2015.00161

83

Mehnert J. M. Mitchell T. C. Huang A. C. Aleman T. S. Kim B. J. Schuchter L. M. et al (2022). BAMM (BRAF autophagy and MEK inhibition in melanoma): a phase I/II trial of dabrafenib, trametinib, and hydroxychloroquine in advanced BRAFV600-mutant melanoma. Clin. Cancer Res.28, 1098–1106. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-21-3382

84

Meierjohann S. (2017). Crosstalk signaling in targeted melanoma therapy. Cancer Metastasis Rev.36, 23–33. 10.1007/s10555-017-9659-z

85

Mendzelevski B. Ferber G. Janku F. Li B. T. Sullivan R. J. Welsch D. et al (2018). Effect of ulixertinib, a novel ERK1/2 inhibitor, on the QT/QTc interval in patients with advanced solid tumor malignancies. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol.81, 1129–1141. 10.1007/s00280-018-3564-1

86

Michielin O. van Akkooi A. C. J. Ascierto P. A. Dummer R. Keilholz U. ESMO Guidelines Committee (2019). Cutaneous melanoma: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up†. Ann. Oncol.30, 1884–1901. 10.1093/annonc/mdz411

87

Montagut C. Settleman J. (2009). Targeting the RAF-MEK-ERK pathway in cancer therapy. Cancer Lett.283, 125–134. 10.1016/j.canlet.2009.01.022

88

Muñoz-Couselo E. Adelantado E. Z. Ortiz C. García J. S. Perez-Garcia J. (2017). NRAS-mutant melanoma: current challenges and future prospect. Onco Targets Ther.10, 3941–3947. 10.2147/OTT.S117121

89

Patel S. P. Lazar A. J. Papadopoulos N. E. Liu P. Infante J. R. Glass M. R. et al (2013). Clinical responses to selumetinib (AZD6244; ARRY-142886)-based combination therapy stratified by gene mutations in patients with metastatic melanoma. Cancer119, 799–805. 10.1002/cncr.27790

90

Peng Y. Wang Y. Zhou C. Mei W. Zeng C. (2022). PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway and its role in cancer therapeutics: are we making headway?Front. Oncol.12, 819128. 10.3389/fonc.2022.819128

91

Phadke M. S. Smalley K. S. M. (2023). Targeting NRAS mutations in advanced melanoma. J. Clin. Oncol.41, 2661–2664. 10.1200/JCO.23.00205

92

Pham D. D. M. Guhan S. Tsao H. (2020). KIT and melanoma: biological insights and clinical implications. Yonsei Med. J.61, 562–571. 10.3349/ymj.2020.61.7.562

93

Posch C. Moslehi H. Feeney L. Green G. A. Ebaee A. Feichtenschlager V. et al (2013). Combined targeting of MEK and PI3K/mTOR effector pathways is necessary to effectively inhibit NRAS mutant melanoma in vitro and in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A.110, 4015–4020. 10.1073/pnas.1216013110

94

Poulikakos P. I. Zhang C. Bollag G. Shokat K. M. Rosen N. (2010). RAF inhibitors transactivate RAF dimers and ERK signalling in cells with wild-type BRAF. Nature464, 427–430. 10.1038/nature08902

95

Puzanov I. Sosman J. Santoro A. Saif M. W. Goff L. Dy G. K. et al (2015). Phase 1 trial of tivantinib in combination with sorafenib in adult patients with advanced solid tumors. Invest New Drugs33, 159–168. 10.1007/s10637-014-0167-5

96

Rager T. Eckburg A. Patel M. Qiu R. Gantiwala S. Dovalovsky K. et al (2022). Treatment of metastatic melanoma with a combination of immunotherapies and molecularly targeted therapies. Cancers (Basel)14, 3779. 10.3390/cancers14153779

97

Reddi K. K. Guruvaiah P. Edwards Y. J. K. Gupta R. (2022). Changes in the transcriptome and chromatin landscape in BRAFi-Resistant melanoma cells. Front. Oncol.12, 937831. 10.3389/fonc.2022.937831

98

Ren M. Zhang J. Kong Y. Bai Q. Qi P. Zhang L. et al (2022). NRAS mutations correlated with different clinicopathological features: an analysis of 691 melanoma patients from a single center. Ann. Transl. Med.10, 31. 10.21037/atm-21-4235

99

Revythis A. Shah S. Kutka M. Moschetta M. Ozturk M. A. Pappas-Gogos G. et al (2021). Unraveling the wide spectrum of melanoma biomarkers. Diagn. (Basel)11, 1341. 10.3390/diagnostics11081341

100

Ribas A. Lawrence D. Atkinson V. Agarwal S. Miller W. H. Jr. Carlino M. S. et al (2019). Combined BRAF and MEK inhibition with PD-1 blockade immunotherapy in BRAF-mutant melanoma. Nat. Med.25, 936–940. 10.1038/s41591-019-0476-5

101

Robert C. Karaszewska B. Schachter J. Rutkowski P. Mackiewicz A. Stroyakovskiy D. et al (2016). Chiarion-sileni VJAoO: three-year estimate of overall survival in COMBI-v, a randomized phase 3 study evaluating first-line dabrafenib (D)+ trametinib (T) in patients (pts) with unresectable or metastatic BRAF V600E/K–mutant cutaneous melanoma. Ann. Oncol.27, vi575. 10.1093/annonc/mdw435.37

102

Robinson J. P. Rebecca V. W. Kircher D. A. Silvis M. R. Smalley I. Gibney G. T. et al (2017). Resistance mechanisms to genetic suppression of mutant NRAS in melanoma. Melanoma Res.27, 545–557. 10.1097/CMR.0000000000000403

103

Ryan M. B. Corcoran R. B. (2018). Therapeutic strategies to target RAS-mutant cancers. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol.15, 709–720. 10.1038/s41571-018-0105-0

104

Sabbah M. Najem A. Krayem M. Awada A. Journe F. Ghanem G. E. (2021). RTK inhibitors in melanoma: from bench to bedside. Cancers (Basel)13, 1685. 10.3390/cancers13071685

105

Saei A. Eichhorn P. J. A. (2019). Adaptive responses as mechanisms of resistance to BRAF inhibitors in melanoma. Cancers (Basel)11, 1176. 10.3390/cancers11081176

106

Savoia P. Fava P. Casoni F. Cremona O. (2019). Targeting the ERK signaling pathway in melanoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci.20, 1483. 10.3390/ijms20061483

107

Schadendorf D. (2025). COLUMBUS part 1-7-year results for encorafenib and binimetinib in BRAF V600-mutant melanoma. Future Oncol.21, 2701–2703. 10.1080/14796694.2025.2536459

108

Serrano C. Mariño-Enríquez A. Tao D. L. Ketzer J. Eilers G. Zhu M. et al (2019). Complementary activity of tyrosine kinase inhibitors against secondary kit mutations in imatinib-resistant gastrointestinal stromal tumours. Br. J. Cancer120, 612–620. 10.1038/s41416-019-0389-6

109

Sievert A. J. Lang S. S. Boucher K. L. Madsen P. J. Slaunwhite E. Choudhari N. et al (2013). Paradoxical activation and RAF inhibitor resistance of BRAF protein kinase fusions characterizing pediatric astrocytomas. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A.110, 5957–5962. 10.1073/pnas.1219232110

110

Smalley K. S. Eroglu Z. Sondak V. K. (2016). Combination therapies for melanoma: a new standard of care?Am. J. Clin. Dermatol17, 99–105. 10.1007/s40257-016-0174-8

111

Solit D. B. Garraway L. A. Pratilas C. A. Sawai A. Getz G. Basso A. et al (2006). BRAF mutation predicts sensitivity to MEK inhibition. Nature439, 358–362. 10.1038/nature04304

112

Steeb T. Wessely A. Petzold A. Kohl C. Erdmann M. Berking C. et al (2021). c-Kit inhibitors for unresectable or metastatic mucosal, acral or chronically sun-damaged melanoma: a systematic review and one-arm meta-analysis. Eur. J. Cancer157, 348–357. 10.1016/j.ejca.2021.08.015

113

Su F. Bradley W. D. Wang Q. Yang H. Xu L. Higgins B. et al (2012). Resistance to selective BRAF inhibition can be mediated by modest upstream pathway activation. Cancer Res.72, 969–978. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-1875

114

Swetter S. M. Johnson D. Albertini M. R. Barker C. A. Bateni S. Baumgartner J. et al (2024). NCCN guidelines® insights: melanoma: cutaneous, version 2.2024. J. Natl. Compr. Canc Netw.22, 290–298. 10.6004/jnccn.2024.0036

115

Teuma C. Pelletier S. Amini-Adl M. Perier-Muzet M. Maucort-Boulch D. Thomas L. et al (2017). Adjunction of a MEK inhibitor to vemurafenib in the treatment of metastatic melanoma results in a 60% reduction of acute kidney injury. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol.79, 1043–1049. 10.1007/s00280-017-3300-2

116

Tian Y. Guo W. (2020). A review of the molecular pathways involved in resistance to BRAF inhibitors in patients with advanced-stage melanoma. Med. Sci. Monit.26, e920957. 10.12659/MSM.920957

117

Tsai F. D. Lopes M. S. Zhou M. Court H. Ponce O. Fiordalisi J. J. et al (2015). K-Ras4A splice variant is widely expressed in cancer and uses a hybrid membrane-targeting motif. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A.112, 779–784. 10.1073/pnas.1412811112

118

Tse A. Verkhivker G. M. (2016). Exploring molecular mechanisms of paradoxical activation in the BRAF kinase dimers: atomistic simulations of conformational dynamics and modeling of allosteric communication networks and signaling pathways. PLoS One11, e0166583. 10.1371/journal.pone.0166583

119

Vakana E. Pratt S. Blosser W. Dowless M. Simpson N. Yuan X. J. et al (2017). LY3009120, a panRAF inhibitor, has significant anti-tumor activity in BRAF and KRAS mutant preclinical models of colorectal cancer. Oncotarget8, 9251–9266. 10.18632/oncotarget.14002

120

Vasta J. D. Michaud A. Zimprich C. A. Beck M. T. Swiatnicki M. R. Zegzouti H. et al (2023). Protomer selectivity of type II RAF inhibitors within the RAS/RAF complex. Cell Chem. Biol.30, 1354–1365.e1356. 10.1016/j.chembiol.2023.07.019

121

Wang M. Banik I. Shain A. H. Yeh I. Bastian B. C. (2022). Integrated genomic analyses of acral and mucosal melanomas nominate novel driver genes. Genome Med.14, 65. 10.1186/s13073-022-01068-0

122

Wang P. Laster K. Jia X. Dong Z. Liu K. (2023a). Targeting CRAF kinase in anti-cancer therapy: progress and opportunities. Mol. Cancer22, 208. 10.1186/s12943-023-01903-x

123

Wang X. Luo Z. Chen J. Chen Y. Ji D. Fan L. et al (2023b). First-in-human phase I dose-escalation and dose-expansion trial of the selective MEK inhibitor HL-085 in patients with advanced melanoma harboring NRAS mutations. BMC Med.21, 2. 10.1186/s12916-022-02669-7

124

Wang Y. Xu G. Xia H. (2025). Targeting the MAPK pathway for NRAS mutant melanoma: from mechanism to clinic. Br. J. Dermatol193, 381–393. 10.1093/bjd/ljaf178

125

Wee P. Wang Z. (2017). Epidermal growth factor receptor cell proliferation signaling pathways. Cancers (Basel)9, 52. 10.3390/cancers9050052

126

Wellbrock C. Arozarena I. (2016). The complexity of the ERK/MAP-Kinase pathway and the treatment of melanoma skin cancer. Front. Cell Dev. Biol.4, 33. 10.3389/fcell.2016.00033

127

Yen I. Shanahan F. Lee J. Hong Y. S. Shin S. J. Moore A. R. et al (2021). ARAF mutations confer resistance to the RAF inhibitor belvarafenib in melanoma. Nature594, 418–423. 10.1038/s41586-021-03515-1

128

Zablocka T. Kreismane M. Pjanova D. Isajevs S. (2023). Effects of BRAF V600E and NRAS mutational status on the progression-free survival and clinicopathological characteristics of patients with melanoma. Oncol. Lett.25, 27. 10.3892/ol.2022.13613

129

Zhang Y. Chen Y. Shi L. Li J. Wan W. Li B. et al (2022). Extracellular vesicles microRNA-592 of melanoma stem cells promotes metastasis through activation of MAPK/ERK signaling pathway by targeting PTPN7 in non-stemness melanoma cells. Cell Death Discov.8, 428. 10.1038/s41420-022-01221-z

130

Zhang M. Maloney R. Liu Y. Jang H. Nussinov R. (2023). Activation mechanisms of clinically distinct B-Raf V600E and V600K mutants. Cancer Commun. (Lond)43, 405–408. 10.1002/cac2.12395

131

Zhong J. Yan W. Wang C. Liu W. Lin X. Zou Z. et al (2022). BRAF inhibitor resistance in melanoma: mechanisms and alternative therapeutic strategies. Curr. Treat. Options Oncol.23, 1503–1521. 10.1007/s11864-022-01006-7

132

Zhou L. Wang X. Chi Z. Sheng X. Kong Y. Mao L. et al (2021). Association of NRAS mutation with clinical outcomes of Anti-PD-1 monotherapy in advanced melanoma: a pooled analysis of four Asian clinical trials. Front. Immunol.12, 691032. 10.3389/fimmu.2021.691032

133

Zhou S. Abdihamid O. Tan F. Zhou H. Liu H. Li Z. et al (2024). KIT mutations and expression: current knowledge and new insights for overcoming IM resistance in GIST. Cell Commun. Signal22, 153. 10.1186/s12964-023-01411-x

134

Zipfel P. A. Brady D. C. Kashatus D. F. Ancrile B. D. Tyler D. S. (2010). Counter CM: ral activation promotes melanomagenesis. Oncogene29, 4859–4864. 10.1038/onc.2010.224

Summary

Keywords

BRAF inhibitors, combination therapy, MAPK pathway, melanoma, NRAS mutations, precision medicine

Citation

Fang X, Wang S and Fu S (2026) Dissecting the MAPK signaling landscape in malignant melanoma: from BRAF and NRAS mutations to precision combination therapies. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 13:1723066. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2025.1723066

Received

11 October 2025

Revised

20 December 2025

Accepted

29 December 2025

Published

14 January 2026

Volume

13 - 2025

Edited by

Yunfei Liu, Central South University, China

Reviewed by

Nicolas Dumaz, Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale (INSERM), France

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Fang, Wang and Fu.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Shuangxing Fu, 15068522838@163.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.