- 1Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Universiti Teknologi PETRONAS, Tronoh, Malaysia

- 2Center for Water Cycle Marine Environment and Disaster Management, Kumamoto University, Kumamoto, Japan

Climate change is intensifying storm surge risks in Southeast Asia, particularly along Malaysia’s east coast facing the South China Sea. This study uses the d4PDF climate dataset to simulate maximum storm surge heights under 2 °C and 4 °C global warming scenarios. Results show that projected surge heights exceed 1 meter at all key coastal stations, with localized surges reaching up to 1.8 meters. By integrating these projections with 2014–2024 flood loss statistics and national budget allocations, the study identifies a concerning mismatch between increasing storm surge risks and current mitigation investments, suggesting that existing policy frameworks are underfunded and may lack the capacity to adequately protect high-risk coastal areas. To address this, the study recommends the development of a unified regional storm surge prediction and response system that integrates real-time data and supports cross-border coordination. It also proposes the establishment of standardized infrastructure guidelines tailored to storm surge resilience, and calls for increased investment in community-based risk mapping powered by artificial intelligence (AI). These strategies provide an actionable framework for strengthening disaster management, improving policy responsiveness, and enhancing coastal resilience across Malaysia and Southeast Asia.

1 Introduction

Storm surges driven by climate change pose an escalating threat to Malaysia’s coastal regions, yet existing research and policy frameworks remain insufficiently prepared. To date, there are no high-resolution, ensemble-based projections of storm surge risk for Malaysia under 2 °C and 4 °C warming scenarios—a critical gap given the country’s rising vulnerability. Moreover, national strategies have not fully integrated long-term surge projections with actual flood loss data and disaster-related funding trends, limiting the effectiveness of current adaptation efforts. This study addresses these gaps by using the d4PDF climate simulation dataset to estimate future surge heights along the east coast of Peninsular Malaysia and link those projections to historical economic losses and policy spending from 2014 to 2024. The results provide urgent, evidence-based insights to support more resilient infrastructure planning and climate-informed policy decisions.

According to the Sixth Assessment Report (AR6) by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), Southeast Asia is expected to experience significant temperature increases and extreme rainfall patterns due to climate change (Hariadi et al., 2023; Kay et al., 2023; Sentian et al., 2022). Southeast Asia, encompassing territories such as Myanmar, Sumatra, Java, Borneo and the Malaysian peninsula, is significantly prone to these alterations, which resulted in prolonged periods of drought, heightened precipitation and elevated occurrences of low flow events in its rivers (Mahmood and Guinto, 2022). Malaysia is expected to experience a significant rise in temperature due to climate change, where studies projected an increase in mean surface temperature from 1.5 °C to 2.0 °C by 2050 (Muhammad et al., 2022), with a further rise of 3–5 °C by the end of the 21st century (Jamaluddin et al., 2018). One of the key consequences is sea level rise (SLR), threatening lowlying coastal areas with flooding, erosion, and displacement. Recent studies reported a growing trend in SLR over the years for Peninsular Malaysia, where tide gauge data show an average increase of 3.20 ± 0.27 mm per year, while satellite altimetry data record an average rise of 4.14 ± 0.32 mm per year (Arif et al., 2023). Besides, rising temperature leads to changes in oceanic pressure and currents, which can disrupt weather patterns - causing more frequent and severe storms, droughts and other extreme weather events (Trossman and Palter, 2021). It is anticipated to enhance cyclone intensity, track, and wind fields—factors that directly affect storm surge dynamics, especially in densely populated coastal regions (Mayo and Lin, 2022). The role of wave-storm surge coupling during tropical cyclones and its contribution to coastal inundation is emphasized in Wu et al. (2018), highlighting the importance of dynamic surge modeling under changing climate conditions. These changes can have devastating effects on water resources and economic stability, resulting in stressing the critical need for effective adaptation strategies to combat the adverse impacts of climate change.

Meanwhile, in Malaysia, storm surges pose a significant threat, especially along the East Coast of Peninsular Malaysia. Storm surge is an abnormal rise in sea level that is induced through a series of factors: wind force, atmospheric pressure changes and wave dynamics. Wind force is particularly important in generating storm surges, especially in shallow coastal areas with wide continental shelves that are exposed to large storms (Abbasi et al., 2021; Rego, 2022; Dang et al., 2017). On the other hand, atmospheric pressure also significantly impacts storm surges, particularly in deeper offshore regions where storms are most intense (Mignone and Lericos, 2011; Bertin, 2016). Wave action plays a crucial function in storm surges, especially along coast-lines facing the open ocean, with the underwater topography (bathymetry) further influencing the extent and impact of wave-induced surges. The East Coast of Peninsular Malaysia comprising states like Kelantan, Terengganu, Pahang and Johor, is highly susceptible because of its proximity to the South China Sea, which results in more powerful waves during monsoon seasons and accelerated coastal erosion (Ismail et al., 2022; Lin and Sahibuddin, 2022). An analysis spanning from 1986 to 2013 reveals that storm surge levels in Malaysia reached their highest point during the 1980s, with a peak surge level of 0.93 meters. These levels subsequently decreased in the late 90s before gradually rising again, contributing to severe flooding and the destruction of coastal structures (Anuar et al., 2018). Additionally, Anuar et al. (2020) developed a statistical approach to assess tide-surge interactions, highlighting the probability of compound extreme storm tides along the South China Sea, particularly during monsoon seasons—supporting observations of elevated surges during such periods in Peninsular Malaysia (Zhuge et al., 2024). Such escalation in surge heights is consistent with synthetic cyclone modeling studies in Zhuge et al. (2025), which projected extreme sea levels and waves under future warming conditions, emphasizing how variations in storm track and intensity contribute to surge hazards in the northern South China Sea. When storm surges coincide with astronomical tides, it creates a phenomenon known as a storm tide, resulting in even higher water levels and more extensive flooding (Tadesse et al., 2022; Dullaart et al., 2023). This compound effect increases flood damage and highlights the need for urgent adaptation and mitigation. Storm track position influences surge intensity; areas closer to the storm center face stronger impacts. However, this study focuses on the broader implications of climate change on storm surge heights and the assessment of policy adaptations, rather than analyzing individual storm tracks.

In 1989, the Meteorological Research Institute (MRI) in Japan, along with the University of Tokyo, JAMSTEC, NIES and Kyoto University supported by the Japanese government, embarked on global warming research. This collaboration has significantly contributed to IPCC assessment reports, developed various climate models and produced the database for policy decision-making for future climate changes, known as the d4PDF dataset. The first set of climate simulations for the d4PDF database was completed in 2015 and has been continuously growing, incorporating more ensemble simulations. This database includes high-resolution global and regional climate models that simulate historical and future climates, covering scenarios of 1.5 °C, 2 °C and 4 °C increases in global mean surface air temperatures which aid in understanding the potential impacts of different degrees of global warming. The dataset features large-ensemble simulations and employs high-resolution global (60 km horizontal mesh) and regional (20 km mesh) atmospheric models. These models are the same as those used operationally by the Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA), with their performance verified on a daily basis, ensuring the data’s reliability (Ishii and Mori, 2020). The d4PDF dataset has been frequently utilized in storm surge studies under climate change impacts as conducted by Igarashi et al. (2022); Mori et al. (2022); Nakajo et al. (2020); and Yang et al. (2018) highlighting its pivotal role in advancing scientific understanding and informing policy decisions. Whereas recent application neighboring country, Thailand was observed in the study of Budhathoki et al. (2023) which further exemplifying its cross-border relevance. To date, the d4PDF dataset has not been utilized for storm surge studies in Malaysia; therefore, this research will pioneer its application in this context.

While a technical approach is crucial, there is a pressing need for policy frame-works and decisions to translate these insights into effective action and resilience-building measures. The current policies and measures in Malaysia to address these coastal threats include several initiatives aimed at mitigating the impacts of climate change which encompasses coastal zone management plans, infrastructure resilience projects and community-based adaptation programs (Zakaria et al., 2019). However, the effectiveness of these policies in addressing future climate scenarios remains uncertain and requires comprehensive evaluation (Dong et al., 2023; Rashidi et al., 2021; Jamaluddin et al., 2018). Thus, leveraging advanced tools like the d4PDF dataset allows for a more precise assessment of the efficacy of these policies. By utilizing high-resolution climate projections provided by the d4PDF dataset, policy-makers can better understand the potential impacts of climate change on coastal regions and tailor adaptation strategies accordingly (Ishii and Mori, 2020).

This study is an extension of previous research by Rosli et al. (2024), entitled “Prediction of Storm Surges in the East Coast of Peninsular Malaysia in Response to Climate Change,” which primarily focused on simulating and predicting storm surge heights along the East Coast of Peninsular Malaysia using the MIKE 21 HD hydrodynamic model and selected ensembles from the d4PDF climate dataset. The earlier work aimed to quantify the physical characteristics and maximum heights of storm surges under historical and future climate scenarios (+2 °C and +4 °C), validate the model against observed data, and identify critical scenarios for coastal engineering applications. While it provided essential baseline projections of storm surge heights, it did not assess the broader socio-economic consequences, policy implications, or adequacy of current mitigation funding. The present study extends this previous work by integrating storm surge projections with historical flood damage records, government disaster response expenditures, and mitigation funding trends to evaluate the financial and policy impacts of extreme coastal flooding. By assessing potential gaps between existing investments and projected surge risks, proposing actionable disaster management strategies, and considering comparative insights from other countries, this study translates physical storm surge modeling into practical guidance for coastal resilience and long-term adaptation planning. In this way, the current paper builds directly upon the foundation of the earlier study while addressing a multidimensional research gap that connects climate-induced hazards with economic and policy decision-making. The findings provide insights that can inform broader policy discussions and encourage international collaboration on climate resilience strategies.

2 Materials and methods

The framework of these methodologies comprises of two main components; the technical assessment aims to project the storm surge heights followed by comparative policy assessment for Malaysia within storm surge scope. The technical assessment was structured as a coherent sequence linking climate datasets, hydrodynamic modeling, and policy application. Atmospheric forcing variables such as wind speed and sea level pressure ensembles were obtained from the d4PDF large-ensemble climate experiment, which captures both long-term variability and rare extremes. These variables were combined with high-resolution bathymetric data from the General Bathymetric Chart of the Oceans (GEBCO) to define coastal boundary conditions for numerical simulation. The coupled inputs were applied in the MIKE 21-FM Hydrodynamic (HD) model, which solves the depth-integrated continuity and momentum equations to reproduce storm surge dynamics under prescribed warming scenarios. The resulting projections of maximum surge heights at four strategically located tide gauge stations along the east coast of Peninsular Malaysia provided the quantitative foundation for the subsequent policy analysis.

2.1 Technical assessment

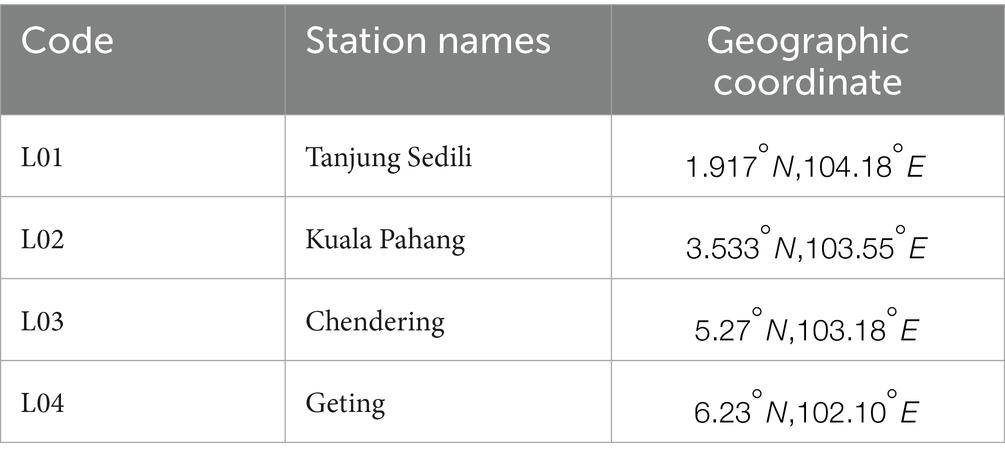

The episode of monsoon in Malaysia could be divided into two types: namely, Northeast Monsoon (NEM) and Southwest Monsoon (SWM), with intervals from November to February and late May to August, respectively. During the NEM season, associated with higher intensity and prolonged precipitation, the potential for storm surges becomes significantly critical. The cold surges phenomenon throughout the NEM season, combined with high tides and strong onshore winds, amplifies the risk of storm surges along the coastline. Aside from the monsoon phenomenon, Malaysia was also influenced by the El Niño and La Niña climate pattern events which resulted from variations in temperature at the ocean (Kamil and Omar, 2017). In Malaysia, El Niño was addressed as El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) resulting in sea level falls and La Niña resulting in sea level rise (Anuar et al., 2018). This event altered the pattern of storm surge characteristics on the coastline. During La Niña, the sea surface temperatures in the central and eastern Pacific Oceans become cooler than usual which led to different atmospheric circulation patterns and NEM becomes more active. It brings long and stronger northeasterly winds and higher precipitation to the eastern regions of Malaysia which is home to significant population centers. These communities, relying on coastal resources and activities, face increased risks during periods of elevated sea levels, exacerbated by high tides, strong winds and intense precipitation. The potential impacts of storm surges during the NEM season raise concerns for the well-being and safety of the coastal population. In light of these considerations, the strategic selection of observation stations along the East Coast becomes paramount. These stations, including Geting (GT), Chendering (CD), Kuala Pahang (KP) and Tanjung Sedili (TS), represent critical points for data collection as tabulated in Table 1. The data gathered from these stations not only contributes to climate-conscious research but also serves as a foundation for developing strategies to enhance the resilience of coastal communities.

To put into perspective, the study area encompasses the coastal states of Peninsular Malaysia bordering the South China Sea, specifically Kelantan, Terengganu, Pahang and Johor as shown in Table 2. These states, with coastline lengths ranging from 96 km in Kelantan to 275 km in Johor, collectively account for a substantial portion of Peninsular Malaysia’s coastal stretch. The total land area of these states represents 62.68% of the peninsula’s entire landmass, which spans approximately 132,265 km2. The combined coastline length of 823 km provides a critical foundation for investigating the dynamics of storm surges and their regional implications. This focus offers a representative cross-section of Malaysia’s diverse coastal environments, vital for understanding the broader environmental and socio-economic challenges posed by rising sea levels and extreme weather events.

2.1.1 Framework of d4PDF datasets

The d4PDF database includes climate simulations with different ensemble sizes for past and future scenarios. For past climate, it has 100 ensemble members starting from 1951 to 2010, using observed sea surface temperatures and sea ice concentrations. For a future climate scenario where the global mean surface air temperature is 2 °C higher than pre-industrial levels, it includes 54 ensemble members covering 60 years from 2031 to 2090. Whereas for a scenario where the temperature is 4 °C higher, it includes 90 ensemble members covering 60 years from 2051 to 2,110. The year 2010 to 2011 were selected for historical simulation as 2010 coincided with one of the most significant climatic disturbances in recent decades, Cyclone Jal, which brought destructive winds, waves exceeding 5 m, and widespread flooding across northern Malaysia, thereby providing a critical case for examining coastal vulnerability and storm surge dynamics (Malaysian Meteorological Department, 2010; Anuar et al., 2023a; Kotal et al., 2013). This period also aligns with the availability of high-resolution observational data, ensuring robust calibration and validation of the simulations. For the future scenario, the years 2090 to 2091 were chosen as they mark the common endpoint of both the 2 °C (2031 to 2090) and 4 °C (2051 to 2,110) warming ensembles in the d4PDF dataset, enabling a direct and internally consistent comparison of extreme coastal impacts under end-of-century climate conditions. The number of ensembles was noted as m001 onwards where each ensemble refers to a collection of climate model simulations that capture different possible outcomes of future climate conditions. The global model used is the MRI atmospheric general circulation model version 3.2 (MRI-AGCM3.2) and the regional model is the nonhydrostatic regional climate model (NHRCM). These models cover areas including the Japanese Islands, the Korean Peninsula and parts of the Asian continent, which are incorporated and chosen in this research. The climate data within this database was initially stored in binary format with the total volume of approximately 2 petabytes. To interpret and utilize the binary data effectively, two widely adopted programming languages, MATLAB and Python, were employed. In MATLAB, the fread function was utilized, while Python leveraged the capabilities of NumPy and xarray libraries. These functions facilitated the efficient reading of binary data. The raw information then underwent a crucial transformation into a structured 3D matrix. Each dimension of this matrix was assigned to represent specific aspects of the climate data, such as time, latitude and longitude. This reorganization was fundamental for subsequent analyses and facilitated the gridded interpolation process. This process involved estimating values at specific grid points within the dataset by calling regional latitude and longitude. To ensure practical utility, the converted data was assessed for compatibility with MIKE 21-HD.

Next, the data were filtered and undergone another phase to select the critical ensemble. Ensembles were selected based on their statistical alignment with observed data, using measures such as mean, standard deviation, and Q-Q plots to ensure consistency and representativeness of climate conditions relevant to Malaysia. The first step focuses on visually analyzing and comparing various ensemble members from the d4PDF dataset against observed data. This step was conducted using Microsoft Excel to assess the agreement between different ensemble members and the observed data. The alignment of data points was scrutinized for accurate comparison. All ensemble members were plotted against observed data on the same graph for a comprehensive side-by-side comparison. The visual analysis focused on examining patterns, trends and similarities between ensemble members and observed data, with particular attention to identifying any discrepancies or outliers indicating differences in distribution characteristics. To double check the analysis, SPSS was utilized, involving the import of ensemble members and observed data into the software. Descriptive statistics, including measures like mean and standard deviation, were computed before the selected ensemble member undergoes a refinement process. During calibration, a correction factor is applied to these parameters. For the mean, the correction factor helps shift the entire distribution of the selected ensemble member closer to that of the observed data. This adjustment ensures that the calibrated ensemble more accurately reflects the central tendency of the observed climate conditions. Similarly, the standard deviation is modified using a correction factor to match the variability of the observed data. The primary objective of calibration is to fine-tune the ensemble member, aligning its statistical properties more closely with those of the observed data. Secondly, the Quantile-Quantile (Q-Q) plot was conducted. First, data points from the calibrated ensemble and observed data were sorted in ascending order to calculate quantiles. Theoretical quantiles, assuming a normal distribution, were plotted against observed quantiles. Ideally, points align along a 45-degree line if the data follows a normal distribution, with deviations indicating distributional disparities. This step is essential for comparing distribution characteristics and assessing the calibrated ensemble’s fit, providing a foundation for informed decision-making in ensemble selection. This visual analysis provided a foundation for informed decision making in subsequent stages of the ensemble selection process. Lastly, return periods were calculated to understand the frequency and magnitude of extreme events. This involved determining the probability of events exceeding a specific threshold, sorting data and establishing a threshold level to identify extreme events. The return period estimation utilized the formula (N + 1)/(R + 1), where N represented the total number of data points and R denoted the rank of the threshold level. It is important to note that this approach assumes a stationary probability distribution. While non-stationary models can reflect evolving climate trends, the use of stationary distributions in this context is appropriate given that ensemble simulations represent distinct climate states (e.g., 2 °C and 4 °C warming scenarios) rather than temporal transitions. This approach allows for comparative assessment of extremes within each stabilized climate condition and is consistent with ensemble-based methodologies adopted in similar studies. Despite this assumption, return periods were empirically calculated for all ensemble members, focusing on the upper tail of the distribution by applying a 95th percentile threshold to identify extreme surge events. This approach emphasizes high-impact, low-probability conditions and enables estimation of maximum, average, and minimum return periods under each scenario. While formal parametric modeling was not applied, the large ensemble size provides sufficient sampling of extreme values, supporting robust empirical estimation suitable for comparative analysis under stabilized climate conditions. The selected ensemble was then imported into MIKE 21 for further simulations.

2.1.2 Theory and governing equations (MIKE 21-FM HD)

This research utilized MIKE 21-FM (Flexible Mesh) HD to simulate the storm surge scenarios for predictive analysis. This tool is a component of the MIKE by DHI software suite designed for simulating two-dimensional hydrodynamic phenomena in oceanographic, coastal and estuarine environments. Its core relies on the Reynolds Averaged Navier–Stokes (RANS) equations, which are fundamental to modeling fluid flow and particularly useful for simulating large-scale, turbulent flows.

The RANS equations are derived from the general Navier–Stokes equations that describe the motion of fluid substances. These equations consist of the continuity equation, which ensures mass conservation and the momentum equations, which account for the conservation of momentum. To handle the complexities of turbulent flows, the RANS approach averages the Navier–Stokes equations over time. This decomposition involves splitting each quantity into a mean (time-averaged) component and a fluctuating component. For instance, velocity (𝑢) and pressure are expressed as and , where the overline denotes the mean component and the prime denotes the fluctuating component. Substituting these decomposed variables into the Navier–Stokes equations and averaging them results in the RANS equations. These equations retain the same form as the original Navier–Stokes equations but include additional terms to account for the effects of turbulence. In the context of MIKE 21HD FM, the relevant equations can be summarized in Equations 1-4 as follows:

• Continuity equation

• Momentum equations

In these equations, are the mean velocity components in the x-, y- and z-directions, while V is the kinematic viscosity and represents the Reynolds stresses due to turbulence. These additional terms arising from turbulence are critical for accurately predicting the flow’s behavior. During a storm surge event, strong winds and changes in atmospheric pressure raise water levels significantly along coastlines. MIKE 21-FM HD incorporates these factors into its RANS equations, allowing it to simulate the dynamic response of water bodies to storm conditions. The model can account for the interactions between wind stress, wave radiation stresses and the hydrodynamic forces acting on the water, providing a detailed representation of the surge’s progression and impact. This ability to simulate the physical processes involved in storm surges, including the effects of turbulence and varying boundary conditions, makes MIKE 21-FM HD a reliable tool for predicting and analyzing storm surge events.

2.1.3 Numerical simulation setup

The core of this setup lies in the computational domain, structured with three open boundaries as shown in Figure 1 to simulate real-world conditions effectively. In the MIKE 21 HD model configuration, three open boundaries were defined along the periphery of the model domain. These open boundaries allowed for the exchange of water between the model domain and the broader South China Sea, enabling the simulation to capture tidal propagation, sea level variations, and storm surge dynamics realistically. The precise geographical locations of the boundaries were defined via coordinate inputs within the model setup.

Water level boundary conditions were imposed using the boundary generation (.21 t) files, which contained time-series data of water level variations. These time-series were generated based on tidal constituents derived from the MIKE Global Tide Toolbox, comprising the primary constituents: M2, S2, N2, K2, K1, O1, P1, Q1, MF, MM, and SSA. This comprehensive set of constituents ensures accurate tidal forcing at the model boundaries.

Each boundary was configured with appropriate tidal forcing, with simulation durations and timing carefully adjusted to align with the intended simulation period. Coastal land boundaries within the domain were defined as closed boundaries (zero normal flow), while open ocean-facing boundaries allowed dynamic interactions between the model and the open sea. This setup ensures the model can realistically simulate the influence of open sea conditions on coastal storm surge behavior.

The domain is defined by a structured grid, with a grid spacing of 0.5625, meticulously chosen to provide a fine-grained representation of coastal topography. Spanning vertically with 500 grid points and horizontally with 464 points, this grid structure allows for comprehensive coverage of the study area, essential for capturing the nuances of coastal dynamics.

In addition to the computational framework, the simulation incorporates key parameters, namely sea level pressure and wind components (u and v), which play a critical role in driving storm surge events. The bathymetric data used in the simulation is sourced from the General Bathymetric Chart of the Oceans (GEBCO), a renowned global dataset known for its detailed information on ocean depths and seabed features. By leveraging GEBCO data, the simulation can accurately represent the underwater terrain, contributing to the fidelity of the results.

To ensure accurate spatial representation, the simulation employs the Universal Transverse Mercator (UTM-48) map projection system. This choice of map projection is crucial for maintaining spatial consistency and alignment with real-world coordinates. Moreover, the simulation accounts for the Coriolis force, an essential factor arising from the Earth’s rotation, which significantly influences fluid motion in oceanic systems.

Temporal discretization is optimized through careful consideration of the time step range. By calculating the last time step based on the duration of the simulation period and incorporating a warm-up period, the simulation achieves a robust temporal representation of dynamic processes. Stability and accuracy in the simulation are further ensured by maintaining the Courant number within the range of 1–2 and applying a Smagorinsky constant of 0.5 to control subgrid-scale turbulence effectively.

Furthermore, the mass budget is meticulously managed by setting the number of polygons to 1, ensuring consistency in mass conservation throughout the simulation. Threshold values for stability, including a drying depth of 0.2 and a flooding depth of 0.3, are established to govern the behavior of the simulation under extreme conditions. Collectively, these components form a comprehensive numerical simulation setup, enabling accurate modeling and analysis of storm surge phenomena.

2.2 Comparative policy assessment

The primary objective of this research is to analyze budget allocation trends for storm surge and flood mitigation in Malaysia from 2014 to 2024. By focusing on financial aspects, the study aims to provide a comprehensive evaluation of how government spending has evolved in response to increasing climate risks. To achieve this, data is collected from primary sources, including government budget reports, financial statements, and official disaster management plans, complemented by secondary sources such as academic studies and policy documents. This multi-source approach ensures the robustness and reliability of the financial assessment.

To structure the analysis of government spending, this study adopts a simplified Input–Output–Outcome (IOO) framework. This approach enables a systematic evaluation of flood-related allocations by organizing the data into three components: inputs (total and flood-specific budget allocations), outputs (programs and infrastructure projects funded), and outcomes (reported or intended benefits such as improved mitigation capacity or policy shifts). While the outcomes are based on publicly reported intentions rather than direct impact measurements, this framework supports a transparent comparison of policy priorities and spending effectiveness across years.

The analysis follows a structured methodology, employing content analysis to systematically categorize budget data and identify key themes related to disaster financing. This enables the study to trace shifts in policy focus, funding priorities, and long-term financial commitments to flood risk reduction. Subsequently, trend analysis is conducted to assess changes in budget allocations over the decade, determining whether increased investments have been made in response to escalating climate threats. This evaluation is further strengthened by incorporating a quantitative assessment of flood-related economic losses, allowing for an empirical examination of the effectiveness of past expenditures in mitigating financial damages.

Beyond a domestic financial evaluation, this study integrates a comparative policy analysis within the discussion section, drawing on international case studies to contextualize Malaysia’s disaster financing approach. By examining the policies of selected countries with similar coastal vulnerabilities, the study highlights best practices in budgetary planning, early warning systems, and integrated flood risk management. While the results primarily focus on Malaysia’s budgetary trends, the comparative in-sights provide a broader perspective on policy effectiveness, offering recommendations on how Malaysia can optimize its disaster preparedness strategies.

By synthesizing financial data, disaster loss assessments, and policy comparisons, this study bridges the gap between climate hazard projections and fiscal decision-making. The findings contribute to a more holistic understanding of the interplay between government expenditure, flood risk management, and long-term coastal resilience planning.

3 Results

3.1 Storm surge projection under climate change impacts

3.1.1 d4PDF datasets preliminary analysis

The d4PDF datasets used in this study stem from extensive climate simulations that cover various climatic conditions and scenarios through multiple ensembles. These ensembles represent distinct climate model runs that capture plausible climate conditions, addressing the inherent variability and uncertainties in climate projections. During the initial study phases, a meticulous ensemble selection technique was applied to identify critical ensembles from the larger pool, focusing on those that accurately represent climate conditions relevant to Malaysia. The selection process involved several steps, which were detailed in the previous section. To summarize the findings after the comprehensive comparison and PDF analysis, Table 3 is generated.

From Table 3, three distinct wind speed scenarios representing historical conditions (m043), a future with a 2 °C global mean temperature increase (m101) and a 4 °C global mean temperature increase (m111) were meticulously chosen for comprehensive analysis. Simultaneously, sea level pressure (SLP) ensembles comprising past conditions (m099), a 2 °C global mean temperature increase (m105) and a 4 °C global mean temperature increase (m110) were identified as critical inputs for future simulations. The past data were selected based on the ensemble that is identical to the observed data as selecting an ensemble that closely resembles the observed data might prioritize models that better capture the current system dynamics. Whereas the future selection is based on the highest PDF value as it indicates a higher probability of occurrence. This careful selection of six key ensembles underwent an additional layer of refinement before further model simulations took place.

This crucial step involved in the data calibration process where the correction factors are applied to d4PDF datasets in order to realign the historical data for windspeed and sea level pressure (SLP). This correction was essential to ensure that the ensemble datasets accurately reflected the observed climate conditions. For example, in the case of windspeed calibration, an initial ensemble (m043) exhibited a range from 0 to 8.5 m/s, which was adjusted using a mean correction factor of 0.245 to closely match the observed range of 0 to 7.2 m/s. Similarly, sea level pressure data for ensemble m099 was refined to improve alignment with observation data. These correction factors play a crucial role in adjusting the distribution of the ensemble datasets, ensuring they mirror the central tendencies and variability of the observed climate conditions. The factors are derived through careful statistical analysis, including comparison with observed data and iterative optimization techniques. After the calibration process, the refined data was transferred to MIKE 21 HD for simulation to determine tidal elevations.

3.1.2 Historical tidal elevation assessment

Tidal elevation refers to the variation in sea level caused by tidal forces, primarily the gravitational influences of the moon and the sun. Tidal elevation is the periodic rise and fall of sea levels, creating high tides and low tides. It is a component of the overall surface elevation, but it represents the rhythmic, predictable changes associated with tidal cycles. Understanding tidal patterns is essential for distinguishing normal tidal fluctuations from abnormal elevations during storm surges. It helps establish a baseline for sea level conditions. This study applied the usage of mean sea level (MSL) which is a vertical datum based on the average sea level over a specified period. The predicted tidal elevation is a historical representation extracted from a global tide table, capturing intricate tidal patterns over time. Tide tables are often organized in a monthly or yearly format, presenting a comprehensive overview of tidal patterns over an extended period.

This historical tidal elevation encapsulates historical storm surge data from d4PDF datasets, allowing for a comparison with the observed tidal elevation through Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) calculation. This calculation served as a statistical measure for quantifying the divergence between the predicted and actual values of a variable. It is widely employed in regression analysis for assessing the precision of a predictive model. It is used to measure the accuracy of a model’s predictions or simulations by calculating the average magnitude of the errors between predicted and observed values. It is particularly useful when assessing the differences between observed and model-generated data. The RMSE is calculated as Equation 5 whereas the calculated RMSE values for all the stations are tabulated in Table 4.

Where,

• is the total number of data points,

• is the observed (actual) value at a time and

• is the predicted value at a time .

The RMSE of 13.367% for Geting which is the highest among all. A higher RMSE suggests a larger average discrepancy between the predicted and observed values, highlighting the need for closer examination. Chendering shows an RMSE of 10.95%, suggesting a moderate level of accuracy in predicting tidal elevations at this station. Whereas the RMSE of 8.98% for Kuala Pahang indicates a relatively lower average percentage difference between the model-generated tidal elevation and the observed values. This suggests a higher level of accuracy in predicting tidal elevations at this station compared to the others. Tanjung Sedili exhibits the lowest RMSE at 7.27%, signifying a more accurate prediction of tidal elevations when compared to observed values. Nonetheless, an RMSE value 10% generally indicates an acceptable level of accuracy based on Anuar et al. (2023b) and Maneechot et al. (2023), emphasizing the model’s capability to closely predict tidal elevations in comparison to observed values. As the RMSE fell within acceptable range, hindcast and forecast simulation were conducted.

3.1.3 Maximum storm surge heights projection

Before moving deeper into predicting the storm surge heights, it is crucial to clarify two key terms related to storm surges. Storm surges specifically refer to the abnormal elevation in water level above the usual surface level, triggered by a storm, indicating the disparity between the predicted astronomical tide level and the actual observed level. Storm surge heights are typically calculated by subtracting the predicted astronomical tide level from the observed water level during a storm event, providing insight into the surge caused solely by the storm’s effects. On the other hand, storm tide encompasses the total water level recorded during a storm, incorporating both the storm surge and the regular tidal cycle.

The analysis was confined to the months from November to March, corresponding to the Northeast Monsoon (NEM) season, which lasts for 5 months. Figure 2 depicts the data from four stations, with three different lines for each station, representing various future scenarios under the impact of climate change. While neap and spring tidal trends might add variability to the overall patterns, the primary focus lies on the consistent portrayal of the scenarios. Scenarios 3 emerges as the most impactful event, exhibiting higher storm surge heights compared to scenarios 2 and 1 which is aligned with the early prediction that 4 °C increment might have adverse effects compared to the others. Whereas the 2 °C increment provides insights aligned with the Paris Agreement, aimed at bolstering the worldwide response to climate change, reasserts the objective of keeping the rise in global temperatures well below 2 °C.

Figure 2. Example output for surge height trends throughout Northeast Monsoon Malaysia for: (a) Tanjung Sedili station; (b) Kuala Pahang station; (c) Chendering station; (d) Geting station.

Meanwhile, the quantitative data extracted and tabulated in Table 5 provide clearer details, it is apparent that storm surge heights are projected to increase for all stations under future climate scenarios in comparison to the historical scenario. This data is extracted from the entire Northeast Monsoon duration in Malaysia from November to March of the respective years. The rise in surge height for all stations is in line with the temperature increase observed in the 2 °C and 4 °C scenarios. Furthermore, the results indicate that the surge height increment is directly proportional to the temperature increase, with higher temperature increases resulting in higher surge heights. In comparing the 2 °C and 4 °C scenarios, it is evident that the storm surge height increment is more significant in the 4 °C scenario than in the 2 °C scenario for all stations. This is expected since the temperature increase is more severe in the 4 °C scenario compared to the 2 °C scenario.

The provided data presents projections of the maximum storm surge heights for four coastal locations; Tg Sedili, Kuala Pahang, Chendering and Getting, using historical data from 2010 to 2011, alongside future projections for 2090 to 2091 under scenarios of 2 °C and 4 °C global temperature increases. These projections, derived from the d4PDF datasets, underscore the significant impact of climate change on coastal storm surge levels, which has critical implications for coastal management and infrastructure resilience. Given the regional focus of this study on specific coastal locations, the analysis primarily emphasizes maximum storm surge elevations along the coastline under different climate change scenarios, highlighting the potential risks associated with rising temperatures.

For Tg Sedili (L01), the historical maximum storm surge height of 0.8878 m is projected to increase to 1.0386 m with a 2 °C rise and further to 1.0889 m with a 4 °C rise, reflecting an increase of approximately 17 and 23%, respectively. In contrast, Kuala Pahang (L02) shows a more dramatic increase from 0.6826 m historically to 1.1587 m under the 2 °C scenario and 1.3789 m under the 4 °C scenario, representing an increase of nearly 70 and 102%. These figures suggest a pronounced susceptibility of Kuala Pahang to enhanced storm surge risks under future climate conditions. Similarly, Chendering (L03) demonstrates a significant projected increase in storm surge heights, from a historical maximum of 0.6186 m to 1.1666 m under the 2 °C scenario and 1.3435 m under the 4 °C scenario. This corresponds to increases of approximately 88 and 117%, respectively. Geting (L04) also exhibits substantial increases, with historical heights of 0.8519 m rising to 1.0346 m (2 °C) and 1.2509 m (4 °C), reflecting increases of about 21 and 47%. Notably, Chendering is projected to experience the highest relative increase among the four locations, highlighting its critical vulnerability and the need for focused adaptive measures. It faces the highest relative increase, while Kuala Pahang’s projections also indicate severe future impacts, especially under the 4 °C scenario. Tg Sedili and Geting, though showing significant increases, exhibit comparatively lower relative risks.

The direct proportionality between temperature increases and surge height increments, observed in this study, aligns with the historical trends identified by Anuar et al. (2018), thereby strengthening the temporal correlation between climate dynamics and storm surge occurrences. The study (Anuar et al., 2018) spans a period from 1986 to 2013 and observes a decline in surge levels in the late 90s, followed by a gradual increase, aligning with our projection of future storm surge heights scenarios (2 °C and 4 °C). The observed pattern of increment is consistent with the current understanding of climate change’s impacts on storm surge heights. The higher sea surface temperatures projected in the future scenario contribute to increased evaporation and moisture content in the atmosphere, leading to more intense storms and higher storm surge heights. These changes contribute to an elevated storm surge risk along the coastal areas, especially when combined with other factors like heavy rainfall, strong winds and high tide.

While the comparison between the sites is useful in assessing the potential impacts of climate change on storm surge heights, it is important to acknowledge the regional context of these locations. As all four sites are situated along the same coastline, the storm surge responses are influenced by similar coastal dynamics, such as wind patterns, topography and tidal conditions. Therefore, while historical comparisons can provide insights into general trends, the variability in storm surge heights across the sites is also shaped by local and regional factors, including the specific positioning relative to the storm’s track and other environmental influences. This study does not extensively cover storm track variations, which can significantly influence surge heights, particularly for locations situated closer to or further from the storm’s center. In future studies, expanding the scope to include storm track variations could further enrich the understanding of the spatial variability in storm surge impacts.

3.2 Comparative policy review

Assessing a nation’s commitment to flood mitigation often relies on budget allocations as an indicator of seriousness, reflecting resource dedication and prioritization. Adequate funding signifies a government’s recognition of flood risks and its willingness to invest in infrastructure development, disaster preparedness and community resilience. It emphasizes the importance of translating policy intentions into tangible actions on the ground. Budget allocations provide the financial means to execute policy decisions, turning strategies into concrete initiatives that directly benefit communities at risk. Therefore, this analysis demonstrates the critical role of budget allocations in advancing policy objectives and facilitating the effective implementation of flood resilience measures, as evidenced in Table 6 by the trend observed from 2014 to 2024.

Over the past decade, Malaysia has witnessed a notable trend of increasing fund allocations toward flood-related initiatives, reflecting a growing recognition of the severity and urgency of addressing flood risks. This trend is evident in the gradual rise of budget allocations dedicated to flood mitigation projects, with the percentage of the overall budget allocated to these initiatives increasing from a modest 0.38% in 2014 to a substantial 8.61% in 2024. Despite some year-to-year variations, the overall trajectory demonstrates a consistent emphasis on flood resilience within government policies and agendas. This emphasis is underscored by the evolution of long-term flood mitigation plans and strategies, indicating a strategic shift toward proactive risk management and disaster preparedness. While the impact of these allocated funds on Malaysia’s overall resilience to floods is yet to be fully realized, there are indications of positive developments in infrastructure, emergency response capabilities and community resilience. Moving forward, it is crucial to continue monitoring and evaluating the effectiveness of these investments, ensuring equitable distribution across regions and addressing emerging challenges to enhance Malaysia’s resilience to floods and natural disasters. Moreover, the increasing focus on flood mitigation projects amidst competing budgetary priorities signifies a prioritization of public safety and environmental sustainability. It reflects a realization that investing in flood resilience not only protects lives and livelihoods but also fosters sustainable development and economic growth. By allocating a larger share of the budget to flood-related initiatives, Malaysia demonstrates its commitment to building a more resilient and adaptive society capable of withstanding the challenges of an increasingly unpredictable climate.

While the upward trend in flood-related budget allocations is commendable, it is essential to address the challenges associated with reporting and long-term planning to ensure optimal utilization of resources. Budget speeches and ministry reports serve as valuable sources of information, but their limited detail on effectiveness assessments presents a notable challenge. Although these sources offer a broad overview of budget allocations, they often lack in-depth insight into how funds are utilized and the actual outcomes achieved. This lack of comprehensive evaluation hinders stakeholders’ ability to gage the effectiveness of flood-related initiatives and raises questions about accountability and transparency in budget utilization. Transitioning toward a centralized portal for annual reports could significantly enhance transparency and accessibility, empowering stakeholders to scrutinize the efficiency and equity of budget utilization more effectively. Additionally, it is imperative to ensure consistency and continuity in flood mitigation efforts despite changes in ministry structures or rebranding. Notably, several organizations related to flood management have undergone transitions from the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environmental Sustainability to the Ministry of Energy Transition and Water Transformation. These shifts reflect changes in governmental priorities and administrative arrangements, emphasizing the need for sustained focus and commitment to flood resilience initiatives. While the long-term flood mitigation plans demonstrate praiseworthy foresight, there is a need for greater transparency and inclusivity in their formulation and execution. These plans should be transparently phased and regionally inclusive, ensuring that they address the unique challenges faced by different states across Malaysia. The actual percentage of the flood-related budget could vary based on specific allocations within the infrastructure and rural development budgets, leading to potential underfunding of critical flood mitigation projects. Lastly, emphasizing insurance as a tool for managing flood risks can indeed be beneficial, however, while stamp duty exemption for insurance can incentivize individuals and businesses to purchase flood insurance, it may not address the root causes of flood risks or promote comprehensive flood resilience. A potentially more effective approach could be offered by the government involving the implementation of risk-based pricing mechanisms for flood insurance premiums. Risk-based pricing for flood insurance premiums involves adjusting the cost of insurance based on the level of flood risk associated with a property. Essentially, properties located in areas with higher flood risk would have higher insurance premiums, while those in lower-risk areas would have lower premiums.

Understanding the current state of flood impacts is indirectly related to the budget supplied by the government, as effective preparedness often requires adequate funding for infrastructure, mitigation measures and emergency response. Figure 3 summarizes the statistics extracted from Jabatan Perangkaan Malaysia (2024); Jabatan Perangkaan Malaysia (2024); Jabatan Perangkaan Malaysia (2024); Jabatan Perangkaan Malaysia (2023); and Jabatan Perangkaan Malaysia (2022), as reported by the Department of Statistics Malaysia (DOSM). While data from 2014 to 2020 was not available, these findings could provide insight into the current implications of Malaysia’s flood preparedness. It is important to note that these figures primarily reflect the impacts of storm surges and coastal flooding within the study area, though minor overlaps with inland flooding costs may exist. From the findings, three out of four states within this research area were reported to be the top three states with the most severe flood impacts.

Johor recorded a 21.8% decrease in losses from 2021 to 2022, indicating improvements in flood handling, but then encountered a dramatic 601.6% increase in 2023, suggesting severe floods or inadequate defenses. Johor witnessed a dramatic surge in flood losses in 2023, soaring to RM275.0 million, a drastic increase compared to RM39.2 million in 2022, marking a percentage increase of approximately 602%. Particularly alarming was the spike in damage to living quarters, which surged to RM121.9 million from a mere RM0.6 million in 2022, representing an increase of roughly 20,183%. District-specific losses were notable, with Batu Pahat district bearing the brunt, experiencing residential losses of RM89.2 million. The agricultural sector suffered significantly, with damages rising to RM25.2 million, marking an increase of approximately 12,500%. Meanwhile, the manufacturing sector reported substantial losses, notably in Segamat and Johor Bahru.

Kelantan experienced a staggering 782.4% rise in losses from 2021 to 2022 due to much more severe flooding or new areas being affected. However, in 2023, Kelantan recorded a notable decrease in total flood losses, amounting to RM139.7 million, down approximately 28% from RM193.9 million in 2022, indicating a reduction in the overall impact of floods. The damage to residential areas significantly decreased from RM44.4 million in 2022 to RM15.4 million in 2023, suggesting fewer affected homes. District-specific losses revealed Pasir Mas as the most severely impacted district with RM15.1 million in losses, followed by Tanah Merah and Tumpat. Business premises damage mirrored this trend, with Pasir Mas bearing the highest losses. While specific figures for the agricultural sector are unavailable, its impact contributed to the overall flood damage. Reductions in damage to public assets and infrastructure also played a role, possibly due to better protection or reduced impact in the recent year.

In contrast, Terengganu recorded a massive increase from 2021 to 2022 due to the minimal losses in 2021 and significantly higher impact in 2022, but then experienced a substantial 67.6% decrease in 2023, pointing to improved flood management or reduced flood severity. Nonetheless, it was reported that total flood losses amounting to RM13.7 million, encompassing damage across various sectors. Residential damage accounted for a significant portion of these losses, totaling RM9.7 million, underscoring the impact on homes and living quarters. Vehicle damage, although present, was relatively smaller at RM90.6 thousand compared to residential damage. Meanwhile, business premises suffered considerable losses amounting to RM2.9 million, indicating significant impacts on local businesses. Flood damage varied across districts in Terengganu, with Besut recording RM212.5 thousand, Setiu RM3.0 million, Dungun RM2.1 million and Kuala Nerus RM1.1 million, among others. While data for the manufacturing sector is absent, the overall economic impact of floods affected multiple sectors, with residential areas bearing the brunt, followed by business premises and vehicles.

Pahang demonstrated consistent improvement with a 69.7% decrease from 2021 to 2022 and a further 58.4% drop in 2023, reflecting ongoing enhancements in flood resilience. The significant reduction in flood losses in Pahang from RM179.9 million in 2022 to RM74.8 million in 2023 can be attributed to several factors. Notably, while damage to residential areas increased from RM1.8 million in 2022 to RM6.7 million in 2023, there was a marked decrease in the impact on public assets and infrastructure, which dropped from RM176.1 million to RM63.4 million. The losses also varied significantly across different districts, with some like Lipis reporting total losses of RM267.8 thousand and Maran reporting RM240.6 thousand. This suggests that the flood’s impact was not uniform and was influenced by the specific economic activities and conditions in each district.

While the variations in flood losses from 2021 to 2023 may partly reflect improvements in policy or mitigation strategies, it is also crucial to consider the intensity and frequency of individual flood events. Extreme events, such as those with a return period of 1 in 100 or 1 in 500 years, can exceed the capacity of even the most robust defenses, leading to catastrophic damage. These losses emphasize the importance of designing flood defenses not only for average conditions but also for rare, high-magnitude events. However, the practicality and affordability of such defenses must be balanced against the economic realities and priorities of the affected regions.

4 Discussion

4.1 Impact of storm surges on Malaysia’s coastal regions

A 1-meter storm surge may seem relatively small, but its impact can be severe, especially in coastal regions like Malaysia. It is important to note that these storm surge heights do not include the effects of high tide. When combined with high tide, the impact of a 1-meter storm surge can be significantly amplified, leading to even greater inundation of coastal areas, erosion of shorelines and disruption of critical infrastructure. To put it into perspective, consider the devastation caused by similar storm surges in neighboring countries like Thailand and Indonesia. In these regions, even a slight increase in sea level can lead to widespread flooding, property damage and loss of life. In Indonesia, Jakarta encountered a 1.03-meter storm surge, coinciding with high tide, which resulted in extensive flooding and temporary and permanent displacement of thousands. The study of Ningsih et al. (2012) revealed the compounding impacts. On the other hand, a recent study in Bennett et al. (2023) revealed coastal regions, particularly North Jakarta, bore the brunt of the inundation, leading to substantial property loss, disruption of vital services and displacement of livelihoods. This event emphasized the vulnerability of Indonesia’s coastal populations to rising sea levels and extreme weather phenomena. Similarly, Thailand has grappled with severe storm surges along its coastal zones, including the Gulf of Thailand and the Andaman Sea. Thai-coast project highlights that a 1-meter sea level rise due to global warming could submerge approximately 1,200 km2 of land, resulting in a loss of around 64 billion bahts and necessitating the relocation of 2.8 million residents (Kuroki and Akagiri, 1996). The inundation disrupted transportation routes, damaged infrastructure and affected thousands of individuals, underscoring the necessity for enhanced coastal resilience strategies and disaster readiness. Studies on storm surge simulations in the South-Central region in Vietnam using the MIKE 21-FM HD model highlighted the maximum surges of 2.34 m in Binh Thuan and 0.78 m in the Khanh Hoa coastal areas (Hoang et al., 2019). The surge, coupled with torrential rainfall and fierce winds, triggered flash floods and landslides, resulting in casualties and extensive damage to property, businesses and agricultural lands. Given the pronounced susceptibility to storm surges and their consequential severity observed in neighboring countries, Malaysia, in its proximate geographic position, ought to exercise caution.

While in Malaysia, past findings from National Hydraulic Research Institute of Malaysia (NAHRIM) (2019) and National Hydraulic Research Institute of Malaysia (NAHRIM) (2017) highlighted the significant consequences following extreme weather events in neighboring countries. For example, in 1989, the close proximity of Typhoon Gay to the Kelantan shoreline, less than 160 km away, resulted in a surge height of 0.52 m in Geting, Kelantan and over 0.4 m along the coasts of Terengganu and Pahang, including Tioman Island. Similarly, in 2006, the effects of Super Typhoon Durian, originating nearly 700 km offshore from the east coast of Peninsular Malaysia, were felt with surge heights exceeding 0.45 m in Geting, Kelantan and 0.54 m, 0.58 m and 0.52 m in Chendering, Terengganu, Tg. Gelang and Tioman Island in Pahang, respectively. These incidents highlight Malaysia’s susceptibility to coastal impacts stemming from severe weather events originating in neighboring regions. While these occurrences may not directly represent storm surge events, they underscore the potential risks posed to Malaysian coastal areas and the importance of proactive measures to mitigate such impacts in the future. Thus, with the findings of this research that reveals the range of storm surges from 0.6 m to 1.4 m, the impact would be even more severe if there is no mitigation plan being implemented before the actual events take place. This range reflects the influence of inter-ensemble variability and geographic factors, including coastal topography and storm exposure. Although the model simulations were calibrated against observed data, the spread in projections highlights the uncertainty that arises from differing emissions trajectories and model sensitivities. These projections should be interpreted as plausible outcomes to guide scenario-based adaptation planning.

To put into perspective, both Kelantan and Terengganu currently face challenges related to seasonal flooding and erosion, exacerbated by deforestation, urbanization, and inadequate infrastructure. The flood waste generated during this period was predominantly construction and demolition waste, as reported by Agamuthu et al. (2015), with wood and concrete being the most abundant types. In Terengganu, the district of Kemaman is particularly vulnerable to coastal hazards, including storm surges, due to the presence of critical infrastructure such as oil refineries and petrochemical plants, which elevate the potential for economic and environmental losses. Studies by Shaaban et al. (2021) and Hasan and Gobithaasan (2023) attribute the district’s relative success in the 2014 flood response to the implementation of early warning technologies, established operational protocols, and strong community engagement, although these measures require timely updates. In Kelantan, Tumpat is highly susceptible to storm surges due to its lowlying terrain and proximity to the Kelantan River estuary. The district is densely populated, with many coastal and agricultural areas at risk of submersion during surge events. The observed differences in storm surge projections across stations are largely shaped by geographical and environmental factors, including coastal topography, bathymetric depth, shoreline geometry, and wind exposure. For example, Tumpat’s shallow coastal shelf and estuarine configuration tend to amplify surge heights by reducing wave energy dissipation, while deeper offshore bathymetry in Johor mitigates surge buildup. Site-specific factors such as tidal range, monsoon wind orientation, and storm trajectory also contribute to variations in projected surges. Pahang and Johor, though slightly more developed, are not immune. In Pahang, riverine proximity and flat terrain increase inundation risk, with Alias et al. (2018) noting that 31% of the population in Temerloh lacked timely early warnings. Johor faces rising mean annual rainfall and frequent flooding, and in urbanized areas like Johor Bahru, critical assets such as ports and industrial hubs face potential disruptions due to storm surges, with broader implications for regional trade and resilience (Anuar and Rahmat, 2022). In densely populated coastal areas such as Johor Bahru, critical economic assets, including ports and industrial zones, could be jeopardized, leading to significant disruptions in trade and commerce.

While this study presents future storm surge projections based on statistically selected and calibrated climate model ensembles, some degree of uncertainty remains. This stems from inter-ensemble variability, sensitivity to model parameters, and the inherent complexity of future climate conditions. To address this, ensemble members were statistically evaluated against observed data, and the MIKE 21 model setup was stabilized through iterative testing to ensure simulation feasibility. Nevertheless, the projections should be interpreted as indicative ranges rather than absolute predictions, as they reflect conditional probabilities under modeled climate scenarios. Acknowledging this uncertainty is essential for contextualizing the robustness of findings and informing adaptive coastal flood risk management strategies.

4.2 Strategic recommendations for storm surge mitigation

Given the profound impact of storm surges, it is imperative to prioritize the development and enforcement of robust policies aimed at enhancing coastal resilience. With the findings from the policy review assessment, Malaysia can take the opportunity to learn from a country like Japan, who has set an exemplary standard in disaster management and resilience planning. Emulating their approach can help us not only to mitigate the immediate risks associated with storm surges but also contribute to sustainable development and long-term climate resilience. On the other hand, the insights gleaned from statistics on the value of flood loss, coupled with the trend analysis of budget supply for flood mitigation, underscore the critical need for effective flood preparedness strategies in Malaysia. The correlation between flood impacts and government budget allocations highlights the necessity of ensuring adequate funding for infrastructure, mitigation measures and emergency response.

Establishing a unified regional storm surge prediction and response system would be a significant step toward enhancing the resilience of coastal regions. This system would integrate climate models, real-time meteorological data and storm surge simulations across neighboring countries, providing a cohesive and reliable source of information. By pooling resources, knowledge and expertise, this collaborative approach would enable all participating nations to enhance their individual and collective preparedness for storm surge events, ultimately reducing the devastating impacts on coastal communities. For neighboring countries, joining such a system offers the opportunity to strengthen regional ties, improve early warning systems and ensure timely, consistent responses that protect vulnerable populations. While Malaysia, through agencies like METMalaysia, is advancing its storm surge prediction capabilities, the concept of a truly unified regional system that integrates real-time data across borders is still emerging. Regional initiatives like those under the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) and the Pacific Islands Climate Change Cooperative have already laid the foundation, but there is great potential to expand and focus specifically on storm surge prediction and response. Participation in this collaborative effort would not only benefit each country by enhancing its resilience but also build a robust, shared framework that can be quickly activated in times of crisis.

Creating consistent infrastructure standards for storm surge resilience across neighboring countries is essential to strengthening coastal defense. While regions like the Netherlands and parts of the Caribbean provide valuable examples of engineering innovation and disaster resilience, their efforts primarily address broader flooding and hurricane impacts rather than storm surge-specific challenges. These examples highlight the importance of regional cooperation and tailored solutions for coastal defense. What is needed is a coordinated regional approach that develops infrastructure standards specifically designed for storm surge protection, considering the unique characteristics of storm surges, such as rapid onset and extreme coastal inundation. By adopting shared guidelines while respecting local geographical differences, countries can align their strategies, improve coastal defenses and foster collaboration. This unified effort would not only enhance resilience to storm surges but also build a stronger foundation for cooperative disaster preparedness and response across the region.

Prioritizing funding for localized community-based risk mapping offers a cost-effective and impactful approach to strengthening resilience against storm surges. By integrating advanced technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI) for risk analysis and mapping, governments can gain a more detailed understanding of vulnerabilities in infrastructure and identify critical areas more precisely. For instance, Japan has successfully integrated AI and machine learning for flood risk prediction, combining historical data and real-time information to generate better forecasts and improve disaster response systems. This method has led to enhanced disaster preparedness and efficient resource allocation. Similarly, in the United States, during Hurricane Milton in 2024, AI was employed in storm surge prediction and risk assessments, which helped optimize evacuation planning and infrastructure investments in coastal regions like Florida. These AI-driven models demonstrated significant improvements in targeting high-risk areas, reducing economic losses and saving lives during storm surge events. In the Malaysian context, regions like Tumpat and Kemaman, identified in this study as having elevated projected surge heights and critical infrastructure, should be considered high-priority zones for targeted investments and policy intervention. Meanwhile, areas with lower relative surge projections could adopt phased resilience planning. This form of geographically-informed prioritization ensures that limited financial and institutional resources are allocated efficiently and equitably. Additionally, incorporating gamified platforms to involve the public can help raise awareness, improve data accuracy and promote greater community engagement. By strategically funding such initiatives, countries can maximize storm surge preparedness and reduce long-term economic damage from these events.

The findings of this study highlight that storm surge projections and simulations are not merely theoretical exercises but serve as essential tools for informing disaster risk management. By integrating numerical modeling results into policy discussions, this study emphasizes the increasing risks of extreme coastal flooding and the need for proactive mitigation strategies. Rather than focusing solely on historical data, the analysis bridges the gap between technical storm surge simulations and real-world policy applications, ensuring that decision-makers have a strong scientific foundation for coastal resilience planning.

While regional cooperation is a key aspect of the recommendations, it is necessary to clarify Malaysia’s responsibility in these initiatives. Existing frameworks, such as the ASEAN Coordinating Centre for Humanitarian Assistance (AHA Centre), provide a foundation for disaster response, yet a dedicated regional storm surge prediction and mitigation system remains absent. This study underscores the potential for Malaysia to contribute significantly to such efforts by integrating advancements in storm surge modeling and disaster preparedness with broader regional initiatives. Strengthening ties with neighboring countries can enhance collective early warning capabilities and response mechanisms, thereby reducing overall economic and human losses.

In addition to emphasizing the importance of prioritizing funding for storm surge defense, this study acknowledges the challenges policymakers face in implementing such strategies. Budget constraints, bureaucratic inefficiencies, and competing national priorities often slow progress in disaster risk reduction. Given the limited resources available, it is crucial for governments to prioritize storm surge defense strategies that focus on critical infrastructure and high-risk areas. Land use planning plays a key position in guiding development away from the most vulnerable zones, while more targeted and selective defense measures can be implemented to protect key assets, such as hospitals, transportation hubs and utilities. Strengthening early warning systems is another essential aspect, enabling timely evacuations and minimizing the impact of storm surges. Additionally, defining clear thresholds for the level of events against which defenses should be designed allows for more efficient allocation of resources. By focusing on these priorities, governments can enhance resilience without the need for exhaustive, all-encompassing protection efforts.

To operationalize regional collaboration, Southeast Asian nations could initiate a dedicated task force under existing platforms such as the ASEAN Coordinating Centre for Humanitarian Assistance (AHA Centre), focused specifically on storm surge hazards. This task force could develop shared storm surge modeling protocols, integrate real-time meteorological and sea-level data via a centralized dashboard, and facilitate regular simulation drills involving national disaster agencies. Additionally, member countries could establish a regional funding mechanism possibly through an ASEAN Climate Resilience Fund to co-finance infrastructure upgrades in high-risk coastal zones. Technical knowledge transfer can be further institutionalized through intergovernmental workshops, academic exchange, and joint research programs among regional universities and agencies.

5 Conclusion

This study serves as a critical reference for integrating technical storm surge simulations with actionable policy measures. As climate change continues to intensify coastal hazards, collaboration among governments, research institutions, and disaster management agencies is essential to strengthening coastal resilience. By combining advanced modeling techniques, regional cooperation, and sustainable funding strategies, a comprehensive and effective approach to mitigating storm surge risks can be developed. These efforts will not only safeguard vulnerable communities but also establish a resilient framework for long-term disaster preparedness across Asia and other coastal regions. Importantly, the findings highlight specific policy gaps, such as the absence of unified regional storm surge forecasting systems and inconsistent infrastructure planning, that can be directly addressed by decision-makers. Bridging these gaps requires not only national-level reforms but also coordinated international efforts to align standards, share real-time data, and strengthen collective early warning systems. While the correlation between government spending and flood loss remains complex, the need for targeted investment in high-risk areas is clear. Lessons drawn from this study, including the Malaysian case, may be adapted and applied to similar coastal contexts in Asia and beyond to support more resilient and equitable disaster response strategies.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the data analyzed in this study was obtained from the d4PDF dataset; the following restrictions apply: users must create an account and agree to the dataset’s usage terms. Requests to access these datasets should be directed to ZGlhcy1vZmZpY2VAamFtc3RlYy5nby5qcA==. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to https://auth.diasjp.net/cas/login?service=http%3a%2f%2fd4pdf.diasjp.net%2fd4PDF.cgi%3ftarget%3dGCM-subset%26lang%3den.

Author contributions

NR: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Visualization, Methodology, Validation. H-MT: Conceptualization, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Resources. SK: Data curation, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This paper publication was funded by Yayasan Universiti Teknologi PETRONAS Fundamental Research Grant (YUTP-FRG), grant number 015LC0-634.

Acknowledgments

All authors confirm that the following manuscript is a transparent and honest account of the reported research. This research is related to a previous study by the same authors titled ‘Prediction of Storm Surges in the East Coast of Peninsular Malaysia in Response to Climate Change.’ The previous study focused on numerical modeling and validation of storm surge simulations, while the current submission expands the work by integrating storm surge projections with funding strategies, financial preparedness, and policy-based adaptation frameworks. The study follows the methodology described in the earlier publication. The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to Yayasan Universiti Teknologi PETRONAS (YUTP) for funding the publication of this paper through grant 015LC0-634.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abbasi, E., Etemadi, H., Smoak, J. M., Rousta, I., Ólafsson, H., Baranowski, P., et al. (2021). Investigation of atmospheric conditions associated with a storm surge in the south-west of Iran. Atmos. 12:1429. doi: 10.3390/ATMOS12111429