Abstract

Background: Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) patients with pregnancy have high maternal mortality. This study aimed to provide clinical evidence with multidisciplinary team (MDT) management and to evaluate the clinical outcomes in PAH patients during the perinatal period.

Methods: We conducted a retrospective evaluation of PAH patients pregnant at the First Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University between May 2015 and May 2021.

Results: Twenty-two patients (24 pregnancies) were included in this study and received MDT management, and 21 pregnancies chose to continue pregnancy with cesarean section. Nine (37.5%) were first-time pregnancies at 27.78 ± 6.16 years old, and 15 (62.5%) were multiple pregnancies at 30.73 ± 3.71 years old. The average gestational week at hospitalization and delivery were 29.38 ± 8.63 weeks and 32.37 ± 7.20 weeks, individually. Twenty-one (87.5%) pregnancies received single or combined pulmonary vasodilators. The maternal survival rate of PAH patients reached 91.7%. Fifteen (62.5%) pregnancies were complicated with severe adverse events. Patients with complicated adverse events showed lower percutaneous oxygen saturation (SpO2), lower albumin, lower fibrinogen, higher pulmonary artery systolic pressure (PASP), higher blood pressure, longer activated partial thromboplastin time, and longer coagulation time. Fourteen (66.7%) pregnancies with cesarean sections were prematurely delivered and 85.7% newborns who survived after the operation remained alive.

Conclusion: The survival rate of parturients with PAH was improved in relation to MDT and pulmonary vasodilator therapy during the perinatal period compared with previous studies. SpO2, albumin, PASP, blood pressure, and coagulation function should be monitored carefully in PAH patients during pregnancy.

Introduction

Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) is a severe disease with the main pathological change being elevated pulmonary vascular resistance, which often leads to right ventricular failure and death (1). The population with a high incidence includes females of childbearing age, and the first clinical manifestations may appear in pregnancy (2). Extensive physiological changes during pregnancy and delivery can exacerbate right ventricular failure in PAH patients (3), leading to high maternal mortality (between 25 and 56%) and poor neonatal outcomes (4–6). Although pregnancy has been prohibited in the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) PAH guidelines (7), some women with PAH insist on pregnancy despite the potential risks.

Advances in medical management have gradually improved the outcomes of PAH patients with pregnancy, but maternal mortality remains high (16–30%) (8, 9). The current guidelines still recommend strict contraception for PAH patients, and early termination is strongly recommended for PAH with pregnancy (7). The management of PAH patients during the perinatal period is heterogeneous in various medical centers, and the evidence of delivery modes, PAH targeted therapy, hemodynamic management, and the use of oxytocin are also unclear (7). Previous studies have suggested early clinical deterioration, severe right ventricular failure, brain natriuretic peptide elevation, and World Health Organization function class III or IV symptoms as high risk factors for maternal outcome (10–12). This study aimed to provide clinical evidence with multidisciplinary team (MDT) management and to evaluate the maternal and infant clinical outcomes in PAH patients during the perinatal period.

Methods

Patients

We identified PAH patients who were pregnant at the First Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University China between May 2015 and May 2021. Electronic and paper medical records of all the patients identified by the query were reviewed independently by two investigators (T. T. Shu and P. P. Feng). Inclusion in the study was predicated on a clinical diagnosis of PAH confirmed by clinical history, physical examination, right-sided heart catheterization (RHC, at the time of admission or within the preceding 5 years), or ultrasound cardiogram (UCG) (1). Patients with preexisting cardiomyopathy, left ventricular ejection fraction <40%, or mitral or aortic valve disease were excluded. Severe PAH was defined as systolic pulmonary artery pressure (PASP) ≥70 mmHg based on the highest measured value during pregnancy (9).

Data Extraction

Data extraction included patient demographic data, including age, insurance, gestational age, expenses, etiology of PAH, comorbidities, and PAH targeted therapy before, during, and after pregnancy. The clinical baseline characteristics included clinical symptoms, blood pressure (BP), heart rate, percutaneous oxygen saturation (SpO2) as measured by finger oximetry, laboratory tests, UCG, and electrocardiogram reports. Perinatal data included delivery mode, the timing of delivery, type of anesthesia, medications, intraoperative bleeding, and intraoperative vital signs. Maternal and neonatal outcomes were collected, including Apgar score, neonatal weight, and referral. Severe adverse events (SAEs) were defined as death, heart failure (HF), respiratory failure (RF), and infection. The patients were divided into the SAE group and without SAE group.

Statistical Analysis

The clinical baseline characteristics of all included pregnancies were descriptive in detail, and they were subgrouped and summarized according to underlying diseases and number of pregnancies. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) for parametric data, and the differences were compared between subgroups. A comparison of continuous parameters was performed using Student's t-test. Dichotomous variables were analyzed using χ2 Fisher's exact test. The difference analysis was performed by SPSS 22.0 software. A P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Baseline Characteristics

Twenty-two female patients (24 pregnancies) with PAH were identified in this study. Two patients were pregnant twice during the study. All pregnancies were natural pregnancies, and there were no medical conceptions. The baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. Eighteen (82%) patients were diagnosed with PAH associated with congenital heart disease (PAH-CHD), three (14%) were idiopathic PAH (IPAH), and one (4%) was PAH associated with connective tissue disease (PAH-CTD). Among these patients, five were diagnosed with PAH before pregnancy, and four received pulmonary vasodilator therapy in advance. Of the 24 pregnancies, nine (37.5%) were first-time pregnancies at 27.78 ± 6.16 years old, and 15 (62.5%) were multiple pregnancies at 30.73 ± 3.71 years old. The average gestational week at hospitalization was 29.38 ± 8.63 weeks. Comorbidities included subclinical hypothyroidism (2), hypothyroidism (1), antiphospholipid syndrome (1), hysteromyoma (1), diabetes (1), colon cancer (1), and uremia (1). There was no significant difference in baseline characteristics among all subgroups according to PAH etiology and gravidity history (P > 0.05, Supplementary Table S1).

Table 1

| Patients | PAH age, y | Pregnancy age, y | GP history | Etiology | ES | NYHA class | BMI, kg/m2 | BP, mmHg | HR, bpm | PVs therapy before pregnancy | PVs therapy during pregnancy | Comorbidity | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medicine | Start time, y | Medicine | Dose** | Start time, wk | |||||||||||

| No. 1 | 30 | 30 | G2P0 | CHD (VSD) | Yes | IV | 20.31 | 181/110 | 94 | – | – | Treprostinil & Tadalafil |

20 ng/kg/min 10 mg qd |

32 32 |

Subclinical hypothyroidism |

| No. 2 | 29 | 29 | G1P0 | CHD (VSD) | Yes | III | 17.63 | 102/76 | 107 | – | – | Treprostinil | 20 ng/kg/min | 29 | – |

| No. 3 | 31 | 31 | G3P0 | CTD | – | III–IV | 21.09 | 92/68 | 79 | – | – | Treprostinil & Tadalafil |

20 ng/kg/min 10 mg qd |

35 35 |

Hypothyroidism |

| No. 4 | 28 | 28 | G1P0 | IPAH | – | II–III | 19.72 | 91/61 | 83 | – | – | Treprostinil & Tadalafil |

20 ng/kg/min 10 mg qd |

14 14 |

– |

| No. 4* | 28 | 30 | G2P0 | IPAH | – | II | 22.49 | 104/65 | 80 | Treprostinil, Tadalafil | 28 | Treprostinil & Tadalafil |

20 ng/kg/min 10 mg qd |

26 26 |

Hypothyroidism |

| No. 5 | 40 | 40 | G1P0 | CHD (ASD) | No | II | 26.44 | 169/101 | 90 | – | – | Treprostinil | 20ng/kg/min | 21 | APS |

| No. 6 | 24 | 31 | G3P0 | CHD (VSD) | Yes | II–III | 18.82 | 98/55 | 95 | Sildenafil, Bosentan, Vardenafil, Ambrisentan, Tadalafil | 25 | Treprostinil & Tadalafil |

20 ng/kg/min 10 mg bid |

32 0 |

– |

| No. 7 | 30 | 30 | G4P1 | CHD (CCTGA+SV) | – | IV | 25.78 | 136/84 | 100 | – | – | Treprostinil | 20 ng/kg/min | 30 | – |

| No. 8 | 25 | 25 | G1P0 | CHD (VSD) | Yes | II | 20.45 | 121/81 | 100 | – | – | Treprostinil | 20 ng/kg/min | 34 | – |

| No. 9 | 36 | 36 | G2P1 | CHD (VSD) | No | II | 25.81 | 107/63 | 96 | – | – | Treprostinil | 20 ng/kg/min | 36 | Hysteromyoma |

| No. 10 | 31 | 31 | G3P1 | CHD (ASD) | No | III | 33.30 | 118/84 | 92 | – | – | Treprostinil | 20 ng/kg/min | 36 | – |

| No. 11 | 30 | 30 | G3P1 | CHD (ASD) | No | II | 21.10 | 107/65 | 97 | – | – | Treprostinil & Tadalafil |

20 ng/kg/min 10 mg qd |

27 27 |

– |

| No. 12 | 20 | 20 | G1P0 | CHD (ASD) | Yes | II | 25.44 | 134/84 | 110 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| No. 13 | 22 | 22 | G1P0 | CHD (PDA) | – | III–IV | 26.56 | 122/67 | 95 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| No. 14 | 18 | 23 | G1P0 | CHD (VSD) | No | II | 17.30 | 110/52 | 69 | – | – | – | – | – | |

| No. 14* | 18 | 28 | G2P0 | CHD (VSD) | Yes | III–IV | 22.96 | 132/77 | 110 | Beraprost Sodium, Bosentan | 23 | Treprostinil & Tadalafil |

20 ng/kg/min 10 mg qd |

30 0 |

– |

| No. 15 | 38 | 38 | G8P1 | CHD (ASD) | No | II | 33.59 | 128/57 | 88 | – | – | – | – | – | Diabetes |

| No. 16 | 21 | 26 | G3P0 | CHD (PDA) | Yes | II | 22.86 | 108/68 | 80 | Bosentan, Sildenafil, Treprostinil | 21 | Treprostinil & Tadalafil |

20 ng/kg/min 10 mg qd |

33 33 |

– |

| No. 17 | 25 | 25 | G3P1 | IPAH | – | II–III | 24.46 | 116/78 | 79 | – | – | Treprostinil | 31 | Colon cancer | |

| No. 18 | 30 | 30 | G4P1 | CHD (VSD) | No | IV | 21.23 | 122/75 | 122 | – | – | Sildenafil | 20 mg tid | 31 | – |

| No. 19 | 37 | 37 | G3P1 | IPAH | – | IV | 33.06 | 142/86 | 96 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| No. 20 | 32 | 32 | G1P1 | CHD (ASD) | No | III | 24.84 | 155/101 | 103 | – | – | – | – | – | Uremia |

| No. 21 | 28 | 28 | G2P1 | CHD (ASD) | No | I | 31.20 | 106/57 | 102 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| No. 22 | 31 | 31 | G1P0 | CHD (ASD) | No | I | 23.30 | 104/65 | 80 | – | – | Treprostinil & Sildenafil |

20 ng/kg/min 10 mg bid |

12 16 |

– |

Baseline characteristics and management of PAH patients with pregnancy.

PAH, pulmonary arterial hypertension; y, years old; GP history, gravidity and parity history; CHD, congenital heart disease; ASD, atrial septal defect; VSD, ventricular septal defect; CTD, connective tissue disease; IPAH, idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension; CCTGA, corrected transposition of great arteries; SV, single ventricle; PDA, patent ductus arteriosus; ES, eisenmenger syndrome; NYHA, New York Heart Association; BMI, body mass index; BP, blood pressure; HR, heart rate; bpm, beats per minute; PVs, pulmonary vasodilators; qd, once daily; bid, twice daily; tid, three times daily; wk, week; APS, antiphospholipid syndrome.

The second pregnancy during the study period.

Treprostinil was titrated gradually from a low dose to a maintenance dose according to the instructions.

Clinical symptoms on admission are shown in Supplementary Table S2, including shortness of breath (20), decreased exercise tolerance (19), palpitation (5), cyanosis (5), dyspnea in the semireclining position (4), acropachy (2), hemoptysis (2), edema (2), thorcalgia (1), syncope (1), and asymptomatic (2). Twelve (50%) of the 24 pregnancies had electrocardiographic abnormalities on admission, including sinus tachycardia (8), right bundle branch block (5), and left anterior fascicular block (2). Eleven patients had PAH-CHD (57.9%), and one had PAH-CTD. All patients underwent UCG examination after admission, and only 7 (30%) underwent RHC within the preceding 5 years. The echocardiographic or RHC parameters at the time of diagnosis of included PAH patients are shown in Supplementary Table S3.

The hospital admission indicators before termination of pregnancy or delivery are shown in Table 2. The average value of SpO2 was 92.54% ± 9.4%, PASP was 73.74 ± 27.35 mmHg, and Barthel index was 90.00 ± 15.11 (Supplementary Table S4). The SpO2 level in two patients was <70% in the non-oxygenated state. The difference in the Barthel index in disease subgroups was significant (P < 0.05), and the other indicators did not differ among the subgroups.

Table 2

| Patients | SpO2, % | HB, g/L | PLT, × 109/L | PT, s | APTT, s | Fbg, g/L | ALB, g/L | BNP, pg/ml | NT-proBNP, ng/L | Braden score | Barthel index | Echocardiographic value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PASP, mmHg | EF, % | LA diameter, mm | LV diameter, mm | RA diameter, mm | RV diameter, mm | PA diameter, mm | ||||||||||||

| No. 1 | 69 | 190 | 58 | 11.1 | 38.3 | 2.48 | 25 | 125 | – | 13 | 90 | 139.1 | 60 | 26 | 50 | 43 | 22 | 31 |

| No. 2 | 94 | 138 | 161 | 11.4 | 28 | 3.66 | 33 | – | – | 15 | 85 | 61 | 56 | 25 | 41 | 32 | 22 | 30 |

| No. 3 | 99 | 126 | 212 | 10.9 | 28.0 | 5.0 | 30 | – | 863 | 18 | 30 | 103 | 69 | 27 | 39 | 45 | 28 | 34 |

| No. 4 | 99 | 122 | 199 | 12.4 | 34.2 | 3.67 | 35 | 65.1 | – | 13 | 100 | 96.1 | 62 | 24 | 42 | 34 | 25 | 27 |

| No. 4* | 96 | 106 | 151 | 10.7 | 27.3 | 4.56 | 36 | – | 116 | 16 | 95 | 79 | 68 | 29 | 43 | 42 | 28 | 43 |

| No. 5 | 98 | 111 | 198 | 11.2 | 24.5 | 3.27 | 38 | 379 | <1 | 17 | 80 | 71.5 | 67 | 42 | 42 | 30 | 27 | – |

| No. 6 | 83 | 87 | 160 | 12 | 37.9 | 2.46 | 38 | – | 257 | 14 | 95 | 58 | 67 | 32 | 47 | 66 | 30 | 32 |

| No. 7 | 65 | 125 | 194 | 12.4 | 34.5 | 3.67 | 28 | – | 4,249 | 15 | 90 | 93# | – | 49 | – | 51 | – | 27 |

| No. 8 | 91 | 141 | 138 | 10.2 | 29.1 | 4.36 | 43 | 420 | – | 18 | 90 | 123 | 59 | 35 | 42 | 42 | 24 | 25 |

| No. 9 | 98 | 122 | 256 | 10.2 | 21.5 | 4.68 | 36 | – | 17 | 21 | 95 | 60.8 | 67 | 24 | 47 | 28 | 18 | – |

| No. 10 | 99 | 106 | 234 | 11.7 | 28.7 | 4.82 | 36 | – | 1,360 | 15 | 90 | 76 | 46 | 44 | 70 | 42 | 26 | 20 |

| No. 11 | 98 | 110 | 216 | 9.8 | 29.7 | 4.2 | 30 | <5 | – | 13 | 95 | 50 | 70 | 30 | 42 | 43 | 33 | 29 |

| No. 12 | 97 | 122 | 224 | 11.9 | 24.3 | 4.35 | 33 | – | 206 | 13 | 100 | 60 | 65 | 34 | 37 | 60 | 39 | 35 |

| No. 13 | 99 | 96 | 180 | 11.6 | 24.7 | 4.54 | 34 | 70 | – | 13 | 95 | 56 | 62 | 32 | 43 | 49 | 29 | 31 |

| No. 14 | 99 | 152 | 128 | 13.8 | 40 | 2.9 | 40 | – | 64 | 13 | 100 | 61 | 72 | 24 | 41 | 30 | 17 | 25 |

| No. 14* | 82 | 153 | 102 | 10.9 | 30.7 | 4.33 | 38 | 13.7 | – | 14 | 100 | 66 | 63 | 24 | 44 | 33 | 20 | 32 |

| No. 15 | 99 | 128 | 191 | 11.1 | 23.2 | 4.35 | 35 | – | 68 | 13 | 95 | 50.2 | 68 | 32 | 45 | 46 | 37 | – |

| No. 16 | 91 | 180 | 130 | 10.9 | 30.3 | 3.97 | 39 | 17.5 | – | 13 | 100 | 81 | 63 | 31 | 49 | 44 | 24 | 37 |

| No. 17 | 86 | 25 | 895 | 15 | 23.6 | 5.08 | 22 | – | 1,510 | 20 | 65 | 50.3 | 67 | 37 | 57 | 36 | 22 | 23 |

| No. 18 | 90 | 88 | 180 | 17.1 | 44.4 | 2.87 | 24 | 882 | 2,540 | 14 | 90 | 127 | 58 | 45 | 60 | 46 | 26 | 45 |

| No. 19 | 98 | 110 | 279 | 10.8 | 23.5 | 3.86 | 27 | – | 1,660 | 15 | 95 | 64.5 | 68 | 31 | 49 | 38 | 20 | – |

| No. 20 | 97 | 86 | 267 | 12.2 | 28 | 5.22 | 37 | – | >35,000 | 14 | 85 | 38 | 51 | 36 | 62 | 34 | 20 | – |

| No. 21 | 97 | 125 | 290 | 10.4 | 27.7 | 4.19 | 36 | – | 14 | 13 | 100 | 35 | 59 | 31 | 45 | 43 | 31 | 28 |

| No. 22 | 97 | 115 | 171 | 10.7 | 27.5 | 3.29 | 38 | – | 147 | 14 | 100 | 70.2 | 67 | 31 | 37 | 32 | 46 | 24 |

Examination indicators and echocardiographic value before termination or delivery in PAH patients with pregnancy.

PAH, pulmonary arterial hypertension; SpO2, percutaneous oxygen saturation; HB, hemoglobin; PLT, platelet; PT, coagulation time; APTT, activated partial thromboplastin time; Fbg, fibrinogen; ALB, albumin; BNP, B-type natriuretic peptide; NT-proBNP, N terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptide; PASP, pulmonary artery systolic pressure; EF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LA, left atrium; LV, left ventricle; RA, right atrium; RV, right ventricle; PA, main pulmonary artery.

The second pregnancy during the study period.

Tricuspid valve pressure difference.

Managements and Delivery

The included patients received medical care from a MDT consisting of PAH physician experts, obstetricians, intensive care unit (ICU) physicians, anesthesiologists, neonatologists, and specialized ICU nurses. All 24 pregnancies were notified of high risk after admission and recommended termination of pregnancy. The average gestational week of termination or delivery was 32.37 ± 7.20 weeks. A total of three patients chose to terminate their pregnancy through medical induction within 20 weeks of gestation (Table 3). Twenty-one cases chose to continue their pregnancy for cesarean section, including two patients with intrauterine stillbirth at 31.6 and 24.9 weeks of gestation.

Table 3

| Patients | GW of delivery, wk | Delivery mode | Anesthesia | PFDW | Uterine contraction | Oxytocin, IU | PB, ml | Amniotic fluid, ml | Ligation of oviduct | Length of operation, min | The moment of fetus retrieval | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T, °C | RR, bpm | HR, bpm | BP, mmHg | SpO2, % | |||||||||||

| No. 1 | 37 | Cesarean section | TGA | Natural | Strong | 20 | 500 | 400 | No | 55 | 36.5 | 12 | 86 | 162/88 | 81 |

| No. 2 | 34.4 | Cesarean section | EA | Natural | Strong | 5 | 500 | 350 | Yes | 120 | 36.5 | 23 | 98 | 104/57 | 97 |

| No. 3 | 37 | Cesarean section | SA + NTGA | Natural | Strong | 10 | 300 | 350 | Yes | 115 | 36.5 | 40 | 94 | 105/61 | 100 |

| No. 4 | 14.6 | Medical induction | – | Uterine curettage | – | – | 110 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| No. 4* | 35.3 | Cesarean section | EA | Natural | Strong | 0 | 200 | 500 | Yes | 125 | 35.5 | 16 | 77 | 120/58 | 99 |

| No. 5 | 21.1 | Medical induction | – | Natural | – | – | 300 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| No. 6 | 32.3 | Cesarean section | EA | Manual | Strong | 15 | 500 | 500 | Yes | 130 | 36.4 | 20 | 90 | 141/70 | 100 |

| No. 7 | 31.3 | Cesarean section | TGA | Manual | Weak | 0 | 600 | 1,000 | Yes | 81 | 36 | 12 | 90 | 118/73 | 93 |

| No. 8 | 35 | Cesarean section | TGA | Natural | Weak | 0 | 500 | 600 | Yes | 47 | 36.5 | 12 | 73 | 79/48 | 94 |

| No. 9 | 37 | Cesarean section | EA | Natural | Weak | 0 | 300 | 600 | Yes | 85 | 36.3 | 14 | 82 | 126/67 | 100 |

| No. 10 | 37.4 | Cesarean section | EA | Natural | Poor | 0 | 100 | 100 | No | 70 | 36.5 | 28 | 109 | 112/71 | 99 |

| No. 11 | 36.9 | Cesarean section | EA | Natural | Strong | 10 | 200 | 400 | Yes | 70 | 36 | 21 | 102 | 118/75 | 100 |

| No. 12 | 37.9 | Cesarean section | EA | Natural | Strong | 5 | 300 | 700 | Yes | 110 | 36.3 | 15 | 104 | 146/85 | 100 |

| No. 13 | 36.3 | Cesarean section | EA | Natural | Strong | 10 | 200 | 500 | No | 70 | 37.2 | 17 | 119 | 102/61 | 100 |

| No. 14 | 11.3 | Medical induction | – | Uterine curettage | – | – | 50 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| No. 14* | 33.9 | Cesarean section | EA | Natural | Weak | 5 | 300 | 500 | Yes | 80 | 36 | 26 | 83 | 165/81 | 92 |

| No. 15 | 36.3 | Cesarean section | EA | Natural | Strong | 10 | 500 | 500 | Yes | 220 | 36.5 | 25 | 91 | 135/71 | 100 |

| No. 16 | 34 | Cesarean section | TGA | Manual | Strong | 10 | 400 | 500 | Yes | 64 | 36.5 | 12 | 70 | 125/72 | 99 |

| No. 17 | 31.6 | Cesarean section | TGA | Natural | Strong | 20 | 200 | 500 | No | 40 | 36.8 | 13 | 80 | 113/68 | 100 |

| No. 18 | 32.7 | Cesarean section | EA | Natural | Poor | 20 | 750 | 600 | No | 70 | 36.6 | 21 | 133 | 163/95 | 100 |

| No. 19 | 24.9 | Cesarean section | SA + NTGA | Natural | Strong | 20 | 750 | 300 | No | 125 | 36.5 | 24 | 76 | 153/76 | 100 |

| No. 20 | 33.9 | Cesarean section | SA + NTGA | Natural | Strong | 10 | 200 | 400 | No | 90 | 37.3 | 27 | 108 | 161/91 | 99 |

| No. 21 | 37.4 | Cesarean section | TGA | Natural | Weak | 20 | 300 | 1,200 | No | 38 | 36.5 | 12 | 115 | 105/60 | 99 |

| No. 22 | 37.4 | Cesarean section | EA | Natural | Weak | 5 | 200 | 600 | No | 91 | 35.7 | 22 | 90 | 147/77 | 100 |

Intraoperative management of pregnancy termination in PAH patients with pregnancy.

PAH, pulmonary arterial hypertension; GW, gestational week; wk, week; TGA, general anesthesia with tracheal intubation; SA + NTGA, spinal anesthesia combined with non–tracheal intubation of general anesthesia; EA, epidural anesthesia; PFDW, placenta and fetal membrane delivery way; IU, international unit; PB, peroperative bleeding; T, temperature; RR, respiratory rate; bpm, beats per minute; HR, heart rate; BP, blood pressure; SpO2, percutaneous oxygen saturation.

The second pregnancy during the study period.

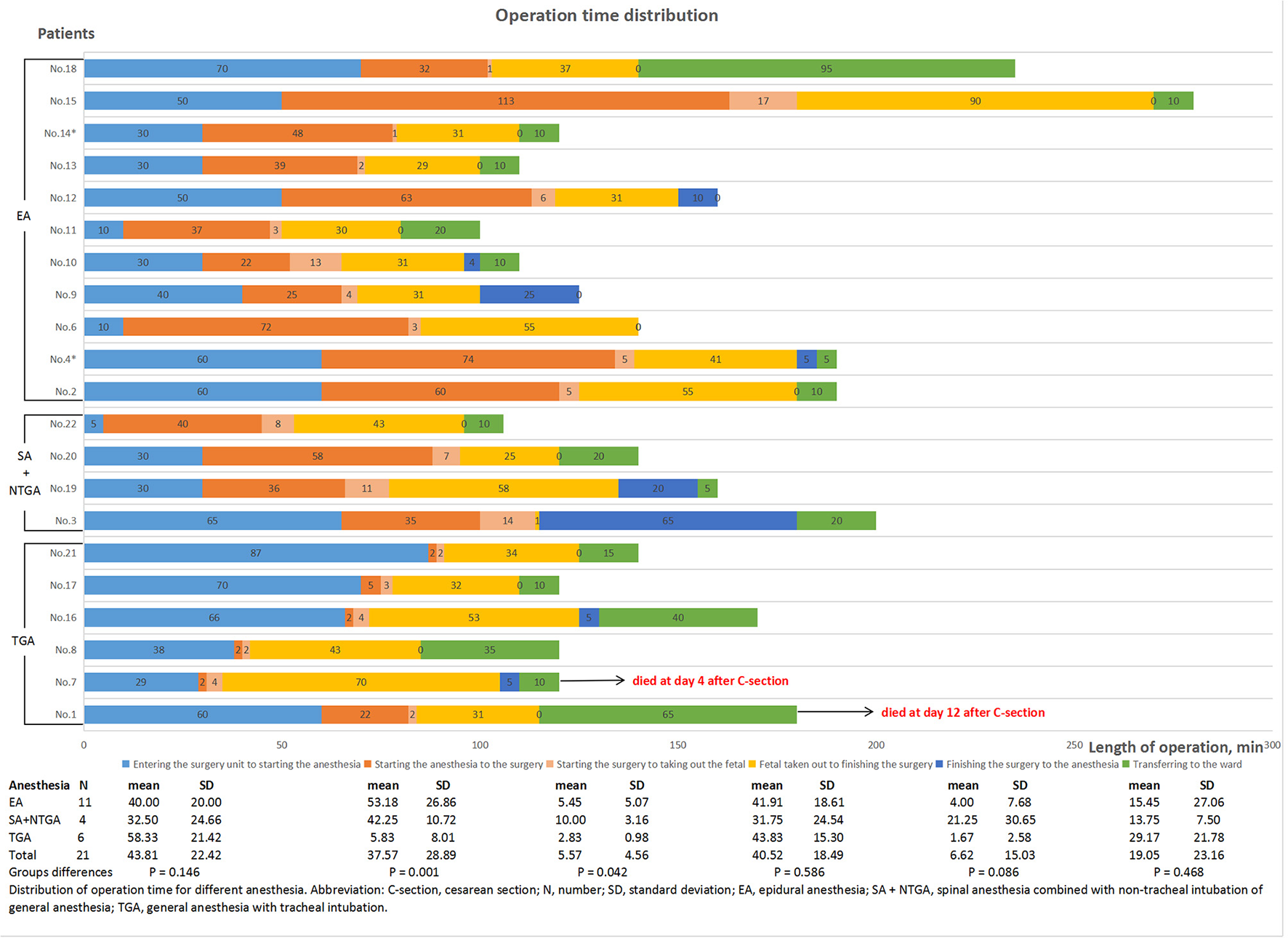

These patients received different anesthesia methods, including six patients with general anesthesia with tracheal intubation (TGA), 11 with epidural anesthesia, and four with spinal anesthesia combined with non-tracheal intubation of general anesthesia (NTGA). During cesarean section, 12 (57.1%) patients underwent ligation of the oviduct. At the moment of fetal retrieval, the SpO2 of four patients was lower than 95%, and one patient had complicated hypotension. The mean perioperative bleeding of these patients was 344.17 ± 193.01 ml. The distribution of operation time, intraoperative vital sign monitoring, and medication for each patient are shown in Figure 1 and Supplementary Figures S1–S21. The distribution of the operation time from starting anesthesia to surgery and from starting surgery to removing the fetus among the groups treated with various anesthesia methods was statistically significant (P = 0.001 and P = 0.042, respectively, Figure 1). Of the 21 patients undergoing cesarean section, 20 (95.2%) were transferred to the ICU immediately after surgery and received intensive monitoring of vital signs.

Figure 1

Distribution of operation time for different anesthesia conditions.

All PAH patients after pregnancy were reminded to receive adequate rest and nutrition. General medications were administered to 24 patients: Before delivery, antibiotics (8), diuretics (8), calcium channel blockers (CCB, 3) were used to control hypertension, and heparin (2). During delivery, antibiotics (18) and intrauterine injection of oxytocin (16), noradrenaline (9), dopamine (3), nitroglycerin (3), adrenaline (1), and dobutamine hydrochloride (1) were administered. After delivery, antibiotics (24), diuretics (10), noradrenaline (3), dopamine (2), heparin (2), CCB (2), angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (1), and angiotensin receptor blocker (1) were administered.

Pulmonary Vasodilators

Overall, eight patients received pulmonary vasodilators throughout the perinatal period, while three did not receive any PAH-targeted therapies (Tables 1, 4, and Supplementary Figures S1–S21). There were 21 (87.5%) pregnancies receiving PAH-targeted therapy: 17 (70.8%) of them received pulmonary vasodilators before operation, of which seven received treprostinil alone, one received sildenafil alone, eight received treprostinil combined with tadalafil, and one received treprostinil combined with sildenafil; 10 (41.7%) received treprostinil intraoperatively; and 19 (79.2%) received post-operatively, of which seven pregnancies received monotherapy (treprostinil or sildenafil) and 12 were treated with a combination of pulmonary vasodilators.

Table 4

| Patients | Maternal outcome at hospital discharge | ICU stay, d | Hospital stay, d | Hospitalization expenditure, million | Proportion of drug expenditure, % | Medical insurance | PVs therapy after delivery | Present status | Time after discharge | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Survival status | HF | RF | Infection | Medicine | Dose | ||||||||

| No. 1 | Deceased | Yes | Yes | Yes | 6 | 20 | 8.18 | 13.4 | URBMI | Treprostinil | 20 ng/kg/min | – | – |

| No. 2 | Alive | Yes | No | No | 4 | 32 | 8.82 | 5.85 | URBMI | Treprostinil & Sildenafil |

20 ng/kg/min 25 mg tid |

Alive | 4.5 y |

| No. 3 | Alive | No | Yes | Yes | 13 | 35 | 16.67 | 19.64 | URBMI | Treprostinil & Tadalafil & Ambrisentan |

20 ng/kg/min 10 mg qd 2.5 mg qd |

Alive | 4 y |

| No. 4 | Alive | No | No | No | 0 | 15 | 2.66 | 0.82 | UEBMI | Treprostinil & Tadalafil |

20 ng/kg/min 10 mg qd |

Alive | 4 y |

| No. 4* | Alive | No | No | No | 1 | 13 | 2.51 | 5.1 | UEBMI | Treprostinil & Tadalafil |

20 ng/kg/min 20 mg qd |

Alive | 2 y |

| No. 5 | Alive | Yes | No | No | 2 | 16 | 1.59 | 8.56 | URBMI | Treprostinil & Sildenafil & Bosentan |

20 ng/kg/min 25 mg tid 62.5 mg tid |

Alive | 3.5 y |

| No. 6 | Alive | Yes | Yes | Yes | 0 | 24 | 5.27 | 16.13 | UEBMI | Treprostinil & Tadalafil |

20 ng/kg/min 20 mg qd |

Alive | 4 y |

| No. 7 | Deceased | Yes | Yes | Yes | 13 | 18 | 4.93 | 19.11 | URBMI | Treprostinil | 20 ng/kg/min | – | – |

| No. 8 | Alive | No | Yes | Yes | 11 | 15 | 4.14 | 12.41 | URBMI | Treprostinil | 20 ng/kg/min | Alive | 2 y |

| No. 9 | Alive | No | No | Yes | 1 | 10 | 2.04 | 9.44 | Self–supporting | Treprostinil | 20 ng/kg/min | Alive | 2 y |

| No. 10 | Alive | No | No | No | 6 | 16 | 2.98 | 15.63 | Self–supporting | – | – | Alive | 2 y |

| No. 11 | Alive | No | No | No | 1 | 15 | 2.34 | 9.83 | Self–supporting | Treprostinil & Tadalafil |

20 ng/kg/min 10 mg qd |

Alive | 2 y |

| No. 12 | Alive | Yes | No | No | 4 | 16 | 2.50 | 9.07 | URBMI | Treprostinil & Sildenafil |

20 ng/kg/min 25 mg tid |

Alive | 14 m |

| No. 13 | Alive | No | No | No | 3 | 10 | 2.30 | 19.9 | URBMI | Treprostinil & Bosentan |

20 ng/kg/min 62.5 mg bid |

Alive | 14 m |

| No. 14 | Alive | Yes | No | Yes | 0 | 8 | 0.73 | 8.82 | Self–supporting | – | – | Alive | 5 y |

| No. 14* | Alive | No | No | No | 1 | 32 | 2.79 | 5.41 | URBMI | Treprostinil & Tadalafil & Macitentan & Beraprost Sodium |

20 ng/kg/min 10 mg qd 10 mg qd 40 ug tid |

Alive | 13.5 m |

| No. 15 | Alive | No | No | No | 1 | 7 | 1.64 | 10.18 | UEBMI | Treprostinil | 20 ng/kg/min | Alive | 13 m |

| No. 16 | Alive | Yes | No | Yes | 1 | 18 | 2.50 | 8.45 | NRCMS | Treprostinil & Tadalafil |

20 ng/kg/min 10 mg qd |

Alive | 18.5 m |

| No. 17 | Alive | No | No | Yes | 3 | 12 | 4.74 | 23.87 | URBMI | Treprostinil | 20 ng/kg/min | Alive | 5.5 m |

| No. 18 | Alive | Yes | Yes | Yes | 4 | 17 | 4.62 | 18.41 | URBMI | Sildenafil | 20 mg tid | Alive | 16.5 m |

| No. 19 | Alive | Yes | No | No | 3 | 11 | 2.49 | 7.39 | UEBMI | – | – | Alive | 4.5 m |

| No. 20 | Alive | Yes | No | No | 1 | 13 | 2.87 | 10.03 | URBMI | – | – | Alive | 5.5 m |

| No. 21 | Alive | No | No | No | 0 | 6 | 1.85 | 15.56 | UEBMI | – | – | Alive | 17.5 m |

| No. 22 | Alive | No | No | No | 2 | 5 | 1.59 | 6.5 | URBMI | Treprostinil | 20 ng/kg/min | Alive | 1.5 m |

Post-operative management and outcome at discharge of PAH patients with pregnancy.

PAH, pulmonary arterial hypertension; HF, heart failure; RF, respiratory failure; ICU, intensive care unit; URBMI, urban residents basic medical insurance; UEBMI, urban employee basic medical insurance; NRCMS, new rural cooperative medical scheme; PVs, pulmonary vasodilators; qd, once daily; bid, twice daily; tid, three times daily; y, year; m, month.

The second pregnancy during the study period.

Maternal Outcomes

No deaths occurred during pregnancy. The maternal survival rate of PAH patients who became pregnant in the present study was 91.7%. Two (8.3%) patients died during the early post-partum period (4 and 12 days after delivery, individually). Both of the deceased patients had PAH-CHD, severe PAH, right heart failure, and multiple pregnancies. Their SpO2 with oxygen was <70% under room air before surgery and <95% at the moment of fetal retrieval, and they both received cesarean section under TGA. One patient had an atrial septal defect (ASD), and the other patient had corrected transposition of great arteries combined with a single ventricle. Other patients discharged from the hospital remained alive to the point of presentation of this study. The follow-up period for discharge ranged from 1.5 months to 4.5 years (median 2 years).

Fifteen (62.5%) pregnancies were complicated with SAE, and their RV diameter was larger than those without SAE (30.56 ± 7.57 mm vs. 24.21 ± 5.67 mm, P < 0.032, Supplementary Table S5). Eleven (45.8%) pregnancies were complicated HF, six (25%) suffered RF, and 10 (41.7%) suffered post-operative infections. Compared with the subgroups without adverse events, deceased patients had a lower admitted SpO2, lower albumin (ALB), higher PASP, and higher BP (P < 0.05, Table 4 and Supplementary Table S5), patients complicated HF showed a longer activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT) and lower fibrinogen (Fbg), patients complicated with RF showed a lower SpO2, longer APTT, lower Barthel index, higher PASP, and higher BP. Patients complicated with post-operative infections had a lower SpO2, longer coagulation time, longer APTT, and higher PASP. TGA was significantly related to death and infection (Supplementary Table S5).

The vital signs of 21 patients undergoing cesarean section were closely monitored during the operation (Supplementary Figures S1–S21). Thirteen (61.9%) pregnancies had SAE, including two pregnancies (9.5%) that died, nine (42.9%) complicated with HF, six (28.6%) that suffered RF, and nine (42.9%) that suffered post-operative infections (Table 4). Compared with the subgroups without corresponding adverse events, lower SpO2 at the time of fetal removal was related to death and RF (P = 0.00 and 0.049, respectively, Supplementary Table S6), and higher systolic and diastolic BP were related to HF (P = 0.032 and 0.018, respectively, Supplementary Table S6). Other vital signs were not significantly different in the subgroups with or without adverse events.

The average hospital stay for 24 pregnancies was 16 ± 8.0 days, of which the ICU stay period was 3.4 ± 3.9 days (Table 4). Compared with childbirth without PAH, the hospital stay of PAH women was significantly longer (13). The average expenditure during hospitalization before reimbursement was ¥ 38645.6 ± 33660.5, which was 10 times the expanses without PAH (¥ 3824.50) (14). The medical insurance type in 14 (58.3%) pregnancies was urban resident basic medical insurance (URBMI, reimbursement ratio 20%), six (25%) were urban employee basic medical insurance (UEBMI, reimbursement ratio 75%), one (4.2%) was a new rural cooperative medical scheme (NRCMS, reimbursement ratio 20%), and three (12.5%) had not purchased any medical insurance were paying for medical care at their own expense.

Fetal/Neonatal Outcomes

Eighteen (85.7%) newborns who survived after the operation remained alive (Table 5). Eight (44.4%) newborns were transferred to the neonatology department immediately after birth, and the families of the other 10 (55.6%) newborns refused section transfer. In the 21 cesarean sections, 14 (66.7%) pregnancies were prematurely delivered.

Table 5

| Patients | Fetal status | Neonate | Apgar score | Transfer to neonatology | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IUGR | FGR | Survival status | Birth weight, g | Gender | Premature | 1 min | 5 min | 10 min | ||

| No. 1 | Yes | Yes | Alive | 1,190 | Male | Full-term | 5 | 5 | 6 | No |

| No. 2 | No | No | Alive | UN | Male | Pre-term | 9 | 10 | 10 | No |

| No. 3 | Yes | No | Alive | UN | Female | Full-term | 9 | 9 | 10 | Yes |

| No. 4* | No | No | Alive | UN | Male | Pre-term | 9 | 10 | 10 | Yes |

| No. 6 | No | No | Alive | 1,800 | Male | Pre-term | 8 | 9 | 9 | Yes |

| No. 7 | Yes | Yes | Deceased** | UN | Female | Pre-term | 5 | 8 | 8 | No** |

| No. 8 | Yes | No | Alive | UN | Female | Pre-term | 6 | 8 | 9 | No |

| No. 9 | No | No | Alive | UN | Female | Full-term | 10 | 10 | 10 | Yes |

| No. 10 | No | No | Alive | 2,850 | Female | Full-term | 9 | 10 | 10 | No |

| No. 11 | No | No | Alive | 2,860 | Female | Pre-term | 9 | 10 | 10 | No |

| No. 12 | No | No | Alive | 3,605 | Male | Full-term | 9 | 10 | 10 | No |

| No. 13 | No | No | Alive | 2,525 | Female | Pre-term | 10 | 10 | 10 | No |

| No. 14* | Yes | No | Alive | UN | Male | Pre-term | 9 | 10 | 10 | Yes |

| No. 15 | No | No | Alive | 2,755 | Male | Pre-term | 10 | 10 | 10 | No |

| No. 16 | Yes | No | Alive | 1,725 | Male | Pre-term | 9 | 10 | 10 | Yes |

| No. 17 | Yes | Yes | Stillborn*** | 1,000 | Female | Pre-term | UN | UN | UN | No*** |

| No. 18 | No | No | Alive | UN | Male | Pre-term | 10 | 10 | 10 | Yes |

| No. 19 | No | No | Stillborn*** | UN | Male | Pre-term | UN | UN | UN | No*** |

| No. 20 | Yes | No | Alive | 1,885 | Female | Pre-term | 9 | 9 | 10 | Yes |

| No. 21 | No | No | Alive | 2,600 | Male | Full-term | 5 | 7 | 8 | Yes |

| No. 22 | Yes | No | Alive | 2,465 | Male | Full-term | 9 | 10 | 10 | No |

Status of the fetus and the newborn after delivery.

The second pregnancy during the study period.

The newborn died on the second day after birth.

The two fetuses were dead before the cesarean section.

IUGR, fetal in utero distress; FGR, fetal growth restriction; UN, unknown.

Discussion

This study observed a high survival rate in parturients and neonates with PAH pregnancy, which may be related to intensive management of MDT and pulmonary vasodilator therapy during the perinatal period. However, the incidence of maternal complications was still high, causing long hospital stays and high expenditures. PAH patients had high risks of poor outcomes during the perinatal period, especially in the early post-partum period. The monitoring time by MDT for PAH patients with pregnancy started slightly late in this center. The present study observed a strong association between SAE and low SpO2 and ALB, high PASP, increased right heart diameter and BP, and severe coagulopathy.

Pulmonary Vasodilator Therapy

With the development of PAH-targeted therapies such as prostacyclins, phosphodiesterase inhibitors 5 (PDE5i), and endothelin receptor antagonists (ERAs), PAH has been well-controlled (1). In this study, most patients used single (prostacyclins or PDE5is) or combined (prostacyclins combined with PDE5is) pulmonary vasodilator therapy during the perinatal period, and the maternal survival rate reached 91.7%. Perinatal PAH targeted therapy was beneficial to the maternal outcomes of PAH (1, 15). However, there is a lack of clinical evidence for the recommended dose of pulmonary vasodilators for PAH patients during pregnancy. In the present study, treprostinil was initiated at 1.25 ng/kg/min and titrated by 2.5 ng/kg/min every 6 h to a final dose of 20 ng/kg/min during the pre- and post-operative period (16) which was lower than the effective dose (40–60 ng/kg/min) routinely used for non-pregnant PAH patients (17, 18). Mainly due to it not being reimbursed in China and high cost (¥ 9,800/20 mg), it was administered at 5 ng/kg/min to 50 ng/kg/min during the operative period. Treprostinil, tadanafil, and sildenafil are not included in medical insurance in China. These drugs were purchased outside the hospital, and this cost was not included in the hospitalization expenses. Studies have shown that ERAs are teratogenic (3) and should be suspended during pregnancy and used in combination after delivery. Due to the physiological changes and complications that occur during pregnancy, it is vital to monitor patients carefully and make dose adjustments as necessary throughout pregnancy and delivery (7).

Clinical Outcomes

Previous systematic overviews and selected case series have reported a high mortality rate (12–56%) in PAH women pregnant (5, 19). However, little is known about the risk factors related to the adverse events of perinatal PAH. In the present study, the incidence of SAE was high (62.5%), and two patients with congenital heart disease died in the early perinatal period. Both of them were in serious hypoxemia (mean SpO2 67% under room air) when admitted to the hospital and did not receive pulmonary targeted vasodilator treatment before pregnancy. The two deceased patients received oxygen inhalation and targeted PAH therapy after admission, but the level of SpO2 was still <95% with 5 L/min oxygen supplementation at the moment of fetal retrieval. Furthermore, this study found that patients with low admitted SpO2 had more intraoperative blood loss, which may be related to the weak contraction of the uterine muscles under hypoxia (20). Long-term refractory hypoxia might be related to an increased risk of death (21). Admitted SpO2, low ALB, elevated PASP and BP were significantly related to death in this study. PAH patients with abnormalities above during pregnancy should be strongly recommended to prohibit or terminate pregnancy.

All patients undergoing cesarean section were closely monitored for intraoperative vital signs. This study found that patients with adverse events presented with lower SpO2 and higher BP at the moment of fetal retrieval. PAH patients with the above abnormalities during surgery should be further vigilant about poor outcomes after delivery. These potential risk factors need to be confirmed in prospective studies in the future.

Pregnant women are accompanied by physiological changes with increased cardiac output. However, the diseased pulmonary vascular system of PAH patients cannot withstand increased cardiac output, resulting in strain and dilation of the right ventricle and ultimately decompensation (3, 12). This study found that severely increased PASP was prone to death, which was consistent with the risk factors proposed in the current guidelines (1, 7). The present study also showed that a higher PASP was significantly related to the occurrence of RF and infection. Eclampsia is one of the dangerous complications of pregnant women (22). There were four patients with hypertension at admission, and elevated BP was associated with death and/or HF. BP at the moment of fetal retrieval in eight patients was higher than the normal level, except one was lower. PAH patients during pregnancy might be more sensitive to BP fluctuations. Therefore, more close monitoring of BP in patients with PAH during pregnancy is necessary. Pregnant women are at risk of hypercoagulability, especially fatal pulmonary embolism (23). Antithrombosis is traditionally used in pregnancies during the perinatal period. More detailed studies on the dosage and time of antithrombotic treatment are needed.

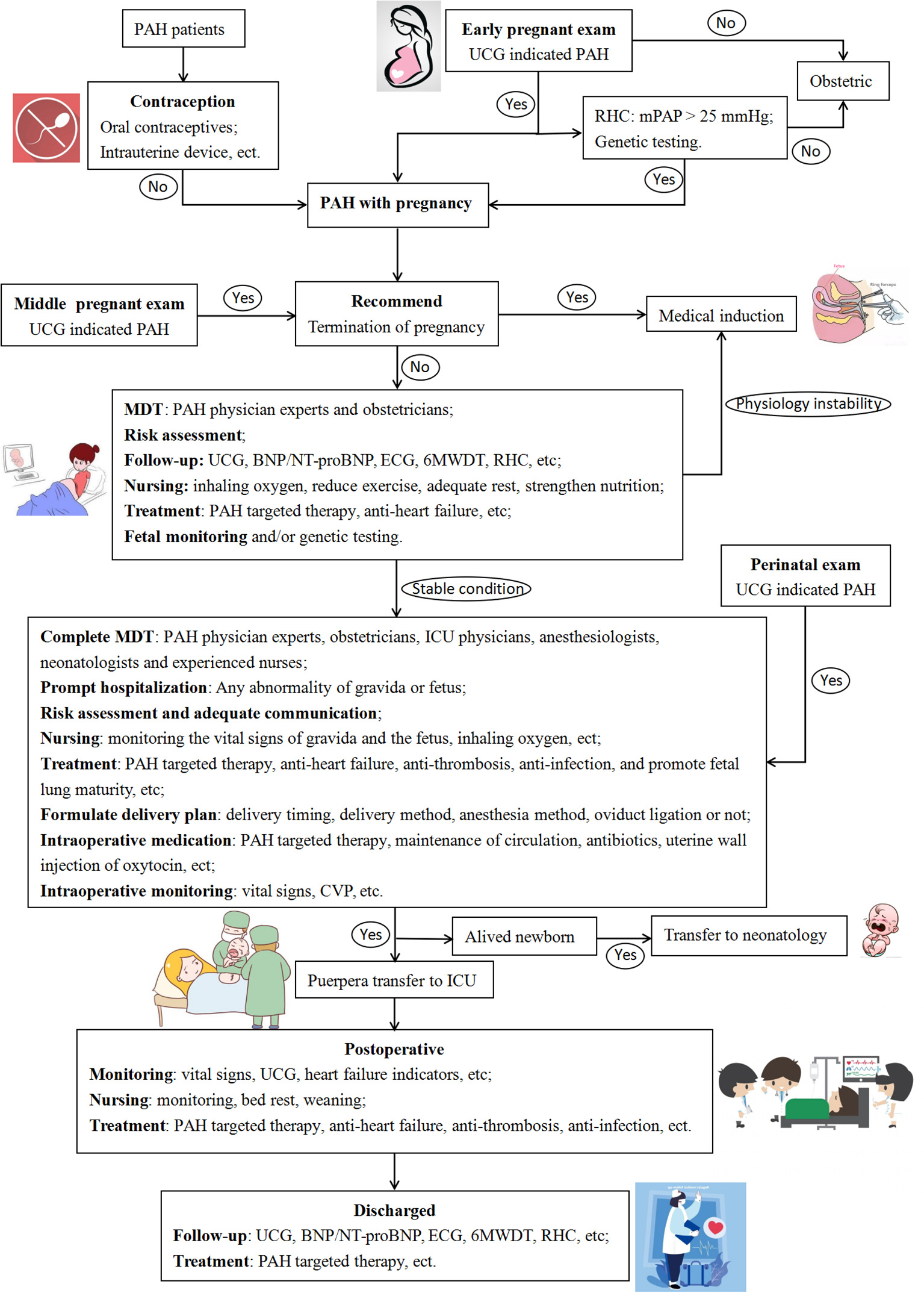

MDT Management

Complete MDT is essential for the comprehensive management of PAH patients during pregnancy (Figure 2) (24). All patients in the present study received tailor-made MDT management. Unfortunately, the start of monitoring time by the MDT team for pregnant women was relatively late in this center, which was detrimental to risk control during pregnancy. Because the maternal mortality rate remains high, patients with PAH are recommended to take contraception (7). Early maternity examinations for pregnant women are essential because PAH is more common in women, and the initial clinical manifestations may occur during pregnancy (7, 10, 11). For pregnant women, echocardiography is utilized to screen for PAH, which is non-invasive, repeatable, and easy to perform (7). With patient consent, it is recommended to perform invasive RHC at an experienced PAH center, and genetic testing can be performed if necessary (7). In this study, the SAE incidence of parturients with PAH was as high as 62.5%. Once PAH with pregnancy is diagnosed, patients need to be informed of the high risk of SAE during pregnancy and after delivery, and medical termination should be recommended. Patients who require continued pregnancy need to receive periodic follow-ups at PAH specialists and obstetricians, monitor PASP, right ventricular function, oxygen saturation, BNP/NT-proBNP, and fetal monitoring (7, 10, 11). During the follow-up, oxygen inhalation, adequate rest, and enhanced nutrition are required. Anti-PAH and anti-heart failure treatments are recommended to being actively given at least 3 months before delivery. Risk assessment should be performed monthly during pregnancy. Once the condition is unstable, emergency admission and prompt termination of the pregnancy are necessary.

Figure 2

Flow chart of diagnosis and treatment for pregnant PAH patients. PAH, pulmonary arterial hypertension; UCG, ultrasound cardiogram; RHC, right heart catheter; mPAP, mean pulmonary artery pressure; MDT, multidisciplinary team; BNP, B-type natriuretic peptide; NT-proBNP, N terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptide; ECG, electrocardiogram; 6MWDT, six minutes walking distance test; ICU, intensive care unit; CVP, central venous pressure.

No spontaneous abortion occurred in this study. Three patients chose medical induction at 11.3, 14.6, and 21.1 weeks. Two patients had intrauterine stillbirths during pregnancy, and cesarean section was performed at 31.6 and 24.9 weeks. Monitoring of pregnant women and fetuses during pregnancy is essential. The patients included in this study were all diagnosed with PAH and pregnancy when they were admitted to the hospital. PAH patients who aborted outside the hospital were not included. The abortion rate of women with PAH was not investigated in the present study. Complete MDT management is required during the third trimester and the entire perinatal period. Pregnant women with PAH should be hospitalized promptly when severe hypoxemia, deteriorated heart failure, coagulation dysfunction, hypertension, and fetal abnormalities occur. Communication should be strengthened with pregnant women and routine follow-up to help them fully understand their condition and improve the compliance of treatments. Pregnant women need to receive PAH-targeted therapy, anti-heart failure, anti-thrombosis, and anti-infection and to promote fetal lung maturity during the perinatal period. During normal pregnancy, blood flow and cardiac output will increase, reaching their peaks at approximately 32 and 24 weeks of gestation, respectively (25). Compared with normal pregnant women, patients with PAH-CHD are intolerant to this physiological change during pregnancy. The increase in PVR in pregnant women with PAH further aggravates PAH, overloads the right ventricle, and ultimately seriously affects right ventricular function (3). In the present study, the premature delivery rate of PAH patients who persisted in continuing pregnancy was high (66.7%). After discussion through MDT, they all chose to perform cesarean section with a mean gestational term of 32.37 weeks, and all of the preterm births were determined by MDT through discussion of the status of the pregnant woman and the fetus. The detailed delivery plan should be developed through MDT discussion, including delivery timing, delivery method, anesthesia method, and oviduct ligation; and communication with the patient to give a full sense of safety. Intraoperative monitoring of the patient's vital signs is important, and it is necessary to continue anti-PAH, maintain circulation, and anti-infective treatments (3). PAH patients are prone to hypoxemia (1), and this study found that it directly affects intraoperative bleeding. Intravenous administration of oxytocin may incr ease the burden on the heart of patients (26, 27), but the bleeding volume of 76.2% of patients in this study was well-controlled by injection of oxytocin through the uterine wall. However, there is currently no study on the dose of oxytocin related to uterine wall injection, and it needs to be administered reasonably according to the uterine contraction and the patient's condition. The highest-risk period for the patients is the puerperium and the early post-partum period (7). It is necessary to transfer to the ICU after delivery. PAH-targeted therapy, anti-heart failure, anti-thrombosis, and anti-infection therapies are recommended to be maintained until the patient is discharged. It is recommended that mothers with PAH avoid breastfeeding after delivery because pulmonary vasodilators may be excreted through breast milk (28). Breastfeeding can also increase maternal fatigue, which is detrimental to the post-partum recovery of PAH patients.

To improve the survival rate, it is recommended that neonates be transferred to neonatology after birth. Late hospitalization increases the risk of adverse events. Therefore, it is critical for patients with PAH in the middle and late stages of pregnancy to be surveillant and treated with the experienced MDT team.

Limitations

The present study was a retrospective single-center trial and reported a relatively small number of patients, so recall bias or reporting bias are unlikely. Due to the small sample size, this study was unable to perform quantitative analysis and identify risk factors. Strengthening of vigilance and management of PAH patients with pregnancy are needed. The patients included in this study were mostly based on UCG and lacked hemodynamic parameters. Due to the small sample size, the failure to conduct a multifactor analysis of all indicators may cause statistical bias in the results. However, not only the baseline characteristics but also the vital signs during and after cesarean section in each patient were collected to investigate the potential risk factors for SAE.

Conclusion

The survival rate of parturients and neonates with PAH has been improved due to MDT management and pulmonary vasodilator therapy during the perinatal period. However, PAH during pregnancy remains a substantial risk and commonly leads to SAE, especially in the early post-partum period. SpO2, ALB, PASP, BP, and coagulation function should be carefully monitored in pregnant PAH patients. Prospective and multicenter studies with large sample sizes in women with PAH are required to determine the pregnancy-related risk factors, supportive care strategies and advanced PAH therapy.

Funding

This work was supported by the Chongqing Municipal Health and Health Committee (ZQNYXGDRCGZS2019001, Nos. 2019ZY3340 and 2016HBRC001).

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the First Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

TS and PF were responsible for the study screening, data extraction, and writing the manuscript. XL contributed to data analysis. LW, HC, and YC were responsible for checking and reviewing the final manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcvm.2021.795765/full#supplementary-material

References

1.

Galiè N Humbert M Vachiery JL Gibbs S Lang I Torbicki A et al . 2015 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension: the Joint Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Respiratory Society (ERS): Endorsed by: association for European Paediatric and Congenital Cardiology (AEPC), International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT). Eur Heart J. (2016) 37:67–119. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv317

2.

McGoon MD Miller DP . REVEAL: a contemporary US pulmonary arterial hypertension registry. Eur Respir Rev. (2012) 21:8–18. 10.1183/09059180.00008211

3.

Olsson KM Channick R . Pregnancy in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir Rev. (2016) 25:431–7. 10.1183/16000617.0079-2016

4.

Bédard E Dimopoulos K Gatzoulis MA . Has there been any progress made on pregnancy outcomes among women with pulmonary arterial hypertension?Eur Heart J. (2009) 30:256–65. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn597

5.

Weiss BM Zemp L Seifert B Hess OM . Outcome of pulmonary vascular disease in pregnancy: a systematic overview from 1978 through 1996. J Am Coll Cardiol. (1998) 31:1650–7. 10.1016/S0735-1097(98)00162-4

6.

Yentis SM Steer PJ Plaat F . Eisenmenger's syndrome in pregnancy: maternal and fetal mortality in the 1990s. Br J Obstetr Gynaecol. (1998) 105:921–2. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1998.tb10240.x

7.

Regitz-Zagrosek V Roos-Hesselink JW Bauersachs J Blomström-Lundqvist C Cífková R De Bonis M et al . 2018 ESC Guidelines for the management of cardiovascular diseases during pregnancy. Eur Heart J. (2018) 39:3165–241. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy340

8.

Mandalenakis Z Rosengren A Skoglund K Lappas G Eriksson P Dellborg M . Survivorship in children and young adults with congenital heart disease in Sweden. JAMA Intern Med. (2017) 177:224–30. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.7765

9.

Sliwa K van Hagen IM Budts W Swan L Sinagra G Caruana M et al . Pulmonary hypertension and pregnancy outcomes: data from the Registry Of Pregnancy and Cardiac Disease (ROPAC) of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur J Heart Fail. (2016) 18:1119–28. 10.1002/ejhf.594

10.

Duarte AG Thomas S Safdar Z Torres F Pacheco LD Feldman J et al . Management of pulmonary arterial hypertension during pregnancy: a retrospective, multicenter experience. Chest. (2013) 143:1330–6. 10.1378/chest.12-0528

11.

Li Q Dimopoulos K Liu T Xu Z Liu Q Li Y et al . Peripartum outcomes in a large population of women with pulmonary arterial hypertension associated with congenital heart disease. Eur J Prev Cardiol. (2019) 26:1067–76. 10.1177/2047487318821246

12.

Hemnes AR Kiely DG Cockrill BA Safdar Z Wilson VJ Al Hazmi M et al . Statement on pregnancy in pulmonary hypertension from the Pulmonary Vascular Research Institute. Pulmon Circ. (2015) 5:435–65. 10.1086/682230

13.

Teigen NC Sahasrabudhe N Doulaveris G Xie X Negassa A Bernstein J et al . Enhanced recovery after surgery at cesarean delivery to reduce postoperative length of stay: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Obstetr Gynecol. (2020) 222:372– 2.e1–10. 10.1016/j.ajog.2019.12.018

14.

Zang S OuYang J Zhao M Zhu Y Liu J Wang X . Factors associated with child delivery expenditure during the transition to the national implementation of the two-child policy in China. Health Qual Life Outcomes. (2021) 19:30. 10.1186/s12955-021-01678-z

15.

Galiè N Humbert M Vachiery JL Gibbs S Lang I Torbicki A et al . 2015 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension: the Joint Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Respiratory Society (ERS): endorsed by: association for European Paediatric and Congenital Cardiology (AEPC), International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT). Eur Respir J. (2015) 46:903–75. 10.1183/13993003.01032-2015

16.

Wang T Lu J Li Q Chen Y Ye Q Gao J et al . Rapid titration of intravenous treprostinil to treat severe pulmonary arterial hypertension postpartum: a retrospective observational case series study. Anesth Analg. (2019) 129:1607–12. 10.1213/ANE.0000000000003827

17.

Barst RJ Galie N Naeije R Simonneau G Jeffs R Arneson C et al . Long-term outcome in pulmonary arterial hypertension patients treated with subcutaneous treprostinil. Eur Respir J. (2006) 28:1195–203. 10.1183/09031936.06.00044406

18.

Parikh KS Rajagopal S Fortin T Tapson VF Poms AD . Safety and tolerability of high-dose inhaled treprostinil in pulmonary hypertension. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. (2016) 67:322–5. 10.1097/FJC.0000000000000357

19.

Jaïs X Olsson KM Barbera JA Blanco I Torbicki A Peacock A et al . Pregnancy outcomes in pulmonary arterial hypertension in the modern management era. Eur Respir J. (2012) 40:881–5. 10.1183/09031936.00141211

20.

Nakashima A Yamanaka-Tatematsu M Fujita N Koizumi K Shima T Yoshida T et al . Impaired autophagy by soluble endoglin, under physiological hypoxia in early pregnant period, is involved in poor placentation in preeclampsia. Autophagy. (2013) 9:303–16. 10.4161/auto.22927

21.

Pullamsetti SS Mamazhakypov A Weissmann N Seeger W Savai R . Hypoxia-inducible factor signaling in pulmonary hypertension. J Clin Investig. (2020) 130:5638–51. 10.1172/JCI137558

22.

Vousden N Lawley E Seed PT Gidiri MF Goudar S Sandall J et al . Incidence of eclampsia and related complications across 10 low- and middle-resource geographical regions: secondary analysis of a cluster randomised controlled trial. PLoS Med. (2019) 16:e1002775. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002775

23.

Konstantinides SV Barco S Lankeit M Meyer G . Management of pulmonary embolism: an update. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2016) 67:976–90. 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.11.061

24.

Hsu CH Gomberg-Maitland M Glassner C Chen JH . The management of pregnancy and pregnancy-related medical conditions in pulmonary arterial hypertension patients. Int J Clin Pract Suppl. (2011) 65:6–14. 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2011.02711.x

25.

Canobbio MM Warnes CA Aboulhosn J Connolly HM Khanna A Koos BJ et al . Management of pregnancy in patients with complex congenital heart disease: a scientific statement for healthcare professionals from the american heart association. Circulation. (2017) 135:e50–87. 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000458

26.

Albackr HB Aldakhil LO Ahamd A . Primary pulmonary hypertension during pregnancy: a case report. J Saudi Heart Assoc. (2013) 25:219–23. 10.1016/j.jsha.2012.12.001

27.

Yamaguchi ET Cardoso MM Torres ML . [Oxytocin in cesarean sections: what is the best way to use it?].Rev Brasil Anestesiol. (2007) 57:324–50. 10.1590/S0034-70942007000300011

28.

Terek D Kayikcioglu M Kultursay H Ergenoglu M Yalaz M Musayev O et al . Pulmonary arterial hypertension and pregnancy. J Res Med Sci. (2013) 18:73–6.

Summary

Keywords

pulmonary arterial hypertension, perinatal period, multidisciplinary team, pregnancy, outcomes

Citation

Shu T, Feng P, Liu X, Wen L, Chen H, Chen Y and Huang W (2021) Multidisciplinary Team Managements and Clinical Outcomes in Patients With Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension During the Perinatal Period. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 8:795765. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2021.795765

Received

15 October 2021

Accepted

29 November 2021

Published

17 December 2021

Volume

8 - 2021

Edited by

Dhrubajyoti Bandyopadhyay, New York Medical College, United States

Reviewed by

Jayakumar Sreenivasan, Westchester Medical Center, United States; Akshay Goel, New York Medical College, United States

Updates

Copyright

© 2021 Shu, Feng, Liu, Wen, Chen, Chen and Huang.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Wei Huang weihuangcq@gmail.com

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

This article was submitted to General Cardiovascular Medicine, a section of the journal Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.