Abstract

Background:

A low estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR <90 mL/min/1.73 m2) is widely recognized as a risk factor for major adverse cardiac events (MACE) after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) for chronic total occlusion (CTO). However, the impact of successful CTO-PCI on quality of life (QOL) of patients with low eGFR remains unknown.

Objectives:

The aim of this prospective study was to assess the QOL of CTO patients with low eGFR after successful PCI.

Methods:

Consecutive patients undergoing elective CTO-PCI were prospectively enrolled and subdivided into four groups: eGFR ≥90 mL/min/1.73 m2 (n = 410), 90 > eGFR ≥ 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 (n = 482), 60 > eGFR ≥ 30 mL/min/1.73 m2 (n = 161), and eGFR <30 mL/min/1.73 m2 (n = 23). The primary outcomes included QOL, as assessed with the European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) questionnaire, and symptoms, as assessed with the Rose Dyspnea Scale (RDS) and Seattle Angina Questionnaire (SAQ), at 1 month and 1 year after successful PCI.

Results:

With the decline of eGFR, CTO patients were more likely to present with comorbidities of hypertension, diabetes, hyperuricemia, and previous stroke, in addition to lower hemoglobin levels and left ventricular ejection fraction (p < 0.05). Low eGFR was associated with greater incidences of in-hospital pericardiocentesis, major bleeding, acute renal failure, and subcutaneous hematoma, but not in-hospital MACE (p < 0.05). Symptoms of dyspnea and angina were alleviated in all CTO patients with eGFR ≥30 mL/min/1.73 m2 at 1 month and 1 year after successful CTO-PCI, but only at 1 month for those with eGFR <30 mL/min/1.73 m2 (p < 0.01). Importantly, QOL was markedly improved at 1 month and 1 year after successful PCI (p < 0.01), notably at a similar degree between patients with low eGFR and those with normal eGFR (p > 0.05).

Conclusion:

Successful PCI effectively improved symptoms and QOL of CTO patients with low eGFR.

Introduction

Chronic total occlusion (CTO) is reported in ~13–41% of patients with coronary artery disease (CAD) and represents one of the last barriers to percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) due to lesion complexity, with lower procedural success rates and greater complication rates, radiation exposure, and procedural duration (1–4). However, with the recent development of interventional techniques and dedicated equipment, the success rate of CTO-PCI can reach 92% among experienced surgeons (5). More importantly, successful CTO-PCI can prolong long-term survival, relieve symptoms, and improve ventricular function (6–9). Among CTO patients, low estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR <90 mL/min/1.73 m2) is widely recognized as an important high-risk factor for in-hospital complications, major adverse cardiac events (MACE), and all-cause mortality after successful PCI (2, 7, 10–17). However, the primary goal of CTO-PCI is generally to improve symptoms and quality of life (QOL) (18). Previous studies have reported that low eGFR is associated with severe angina and reduced QOL (19, 20), thereby emphasizing the importance of the symptoms and QOL of CTO patients with low eGFR. A report by the OPEN-CTO registry (Outcomes, Patient Health Status, and Efficiency in Chronic Total Occlusion Hybrid Procedures) found that successful CTO-PCI significantly improved angina of patients with low eGFR (<60 mL/min/1.73 m2) (21), although there is no data to determine whether successful CTO-PCI will actually improve QOL of these patients. Therefore, to address this gap in knowledge, the aim of this prospective study was to assess the effect of successful CTO-PCI on symptoms of angina and dyspnea and QOL of patients with low eGFR to provide real-world experience for revascularization of CTO patients with low eGFR.

Methods

Patient population

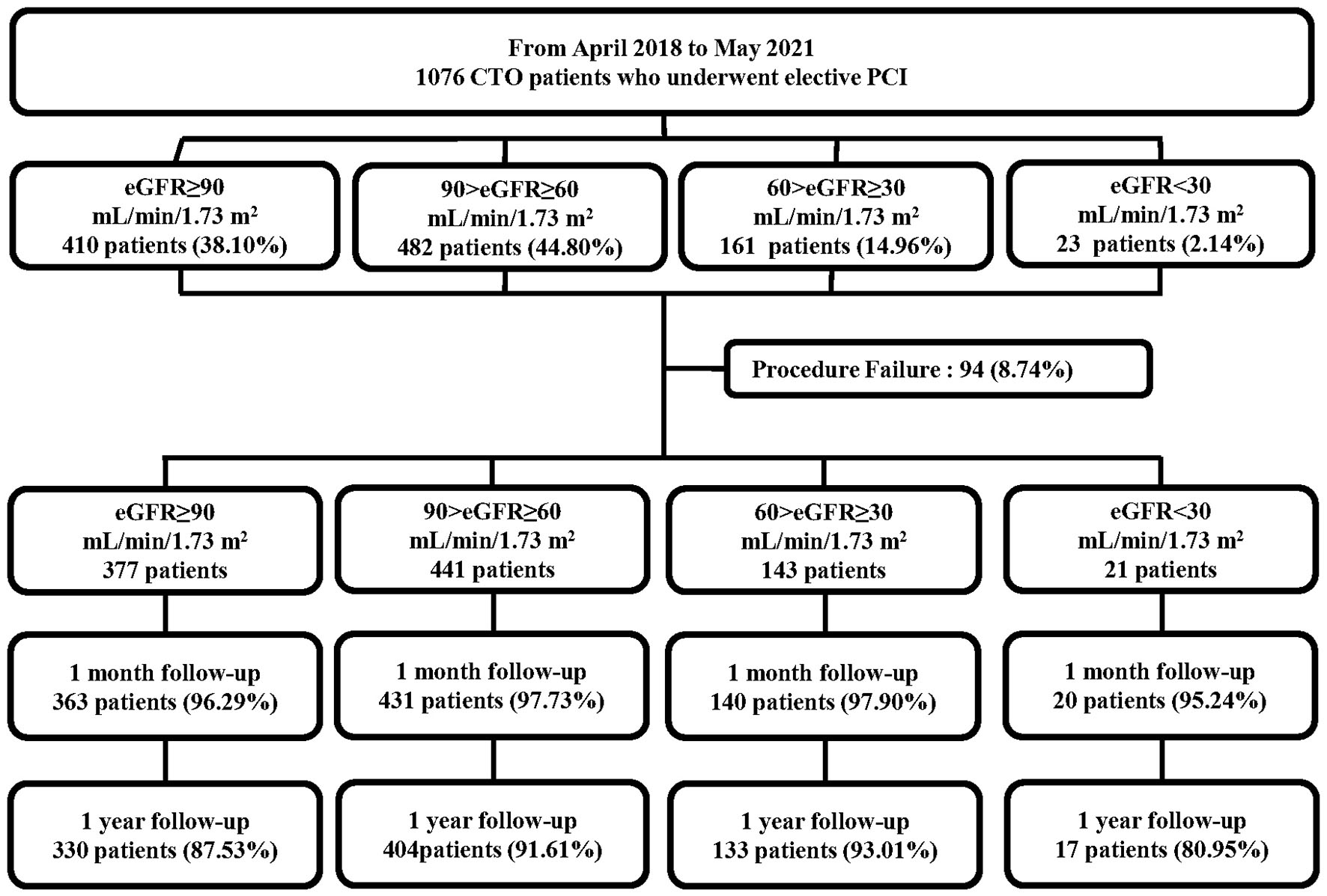

In total, 1,076 consecutive patients who underwent elective PCI for at least 1 CTO lesion in the period between April 2018 and May 2021 were prospectively enrolled in this study (Figure 1). All the procedures were performed at Xijing Hospital (Xi'an, Shaanxi, China) by one CTO team led by Dr. Chengxiang Li who personally completed or guided all procedures. Patients with acute myocardial infarctions (ST or non-ST elevation), cardiogenic shock, and unstable hemodynamics were excluded. Indication for coronary revascularization was based on angina symptoms or non-invasive imaging (computed tomography) of the coronary artery. The revascularization strategy (PCI or coronary-artery bypass grafting and lesions to be revascularized) was individualized for each patient and left to the discretion of the cardiac surgeon and interventionalists in our center. If the patient rejected the surgical recommendation, PCI was proposed if considered feasible by the chief surgeon.

Figure 1

Flowchart of the study population. CTO, chronic total occlusion; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate.

The eGFR was calculated at baseline for each patient using the Modification in Diet in Renal Disease equation (22). Based on the eGFR, the study cohort was subdivided into four groups, consistent with prior publications (16, 17, 23): eGFR ≥90 mL/min/1.73 m2, 90 > eGFR ≥ 60 mL/min/1.73 m2, 60 > eGFR ≥ 30 mL/min/1.73 m2, and eGFR <30 mL/min/1.73 m2. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Xijing Hospital (approval no. KY20172019-1) and each subject provided informed consent before recruitment.

Definition and endpoints

Coronary CTO was defined as angiographic evidence of total occlusion with thrombolysis in myocardial infarction flow grade 0 within a major epicardial coronary artery of at least 2.5 mm, with an estimated duration of at least 3 months. Non-CTO was defined as diameter stenosis of 50% for left main (LM) or 70% for non-LM CAD within a vessel diameter ≥2.5 mm (23). Revascularization was considered for angiographically significant stenosis (≥70% diameter reduction by visual assessment) and functionally significant stenosis (fractional flow reserve measurement <0.80). Complete revascularization was defined as revascularization of all significantly diseased major epicardial vessels during the same hospitalization. The J-CTO score (Multicenter CTO Registry in Japan) was calculated as previously described (24). Procedural success was defined as successful CTO revascularization with achievement of <30% residual diameter stenosis within the treated segment and restoration of Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction flow grade 3 (antegrade) and no in-hospital MACE. In-hospital MACE included any of the following adverse events prior to hospital discharge: all-cause mortality, non-fatal myocardial infarction, and clinically driven revascularization. Major bleeding was defined as Bleeding Academic Research Consortium type 3 or greater (25).

Follow-up

Patients were followed-up by a clinical visit or telephone interview at 1 month and 1 year after CTO-PCI. The outcomes of interest for this study were changes to symptoms, including dyspnea and angina, and QOL. Details regarding symptoms and QOL were obtained from hospital re-admission records and outpatient visits.

Symptom assessment

Dyspnea was assessed at baseline and then at 1 month and 1 year after CTO-PCI in compliance with the Rose Dyspnea Scale (RDS). The RDS is a four-item questionnaire to assess the level of dyspnea while performing common activities (26), where each activity associated with dyspnea is assigned 1 point. RDS scores range from 0 to 4, with a score of 0 indicating no dyspnea and increased scores indicating greater severity of dyspnea.

The angina status of the patient was assessed with the Seattle Angina Questionnaire (SAQ) (27) at baseline and then at 1 month and 1 year after CTO-PCI. The SAQ consists of 19 items that measure five dimensions: angina frequency (AF), angina stability (AS), disease perception, physical limitation, and treatment satisfaction. All items were assessed with a five-point descriptive scale and the total score was calculated as the sum of all individual scores within each group and transformed to a scale of 0 to 100, where 0 is the worst and 100 is the best.

QOL assessment

QOL was assessed with the use of the European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) questionnaire at baseline and then at 1 month and 1 year after CTO-PCI. The EQ-5D questionnaire assesses five dimensions of general health (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression) with a three-point scale. The EQ-5D scores were converted to utilities with an algorithm developed for a Japanese population. Utilities are preference-weighted health status assessments with scores ranging from −0.11 to 1.00, with 1.00 representing perfect health and −0.11 representing poorest health (28, 29).

Statistical analysis

Study participants were categorized according to the baseline eGFR. The baseline characteristics, angiographic characteristics and procedural details, intraprocedural and in-hospital complications were shown in Tables 1–3. Continuous variables are presented as the mean ± standard deviation or the median and interquartile range, whereas categorical variables are presented as percentages. Continuous variables were compared with the ANOVA test (normal distribution) or Kruskal–Wallis H test (abnormal distribution). Categorical variables were compared with the chi-square test or Kruskal–Wallis H test (NYHA functional class). The changes of symptoms and QOL (EQ-5D) were showed in Tables 5, 7. The comparison between two groups was used the student t-test while the comparison among four groups was used ANOVA test. Univariable and multivariable binary logistic regression analysis were performed to identify the risk factors of in-hospital complications and 1-year symptoms and QOL improvement in patients with low eGFR (<90 mL/min/1.73 m2) after successful CTO-PCI (Tables 4, 6, 8). A two-sided probability (p) value of <0.05 was considered significant. All calculations were performed with IBM-SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 25.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) and STATA 14 software (https://www.stata.com/stata14/).

Table 1

|

eGFR ≥90

mL/min/1.73 m2 |

90 > eGFR ≥60

mL/min/1.73 m2 |

60 > eGFR ≥30

mL/min/1.73 m2 |

eGFR < 30

mL/min/1.73 m2 |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 410) | (n = 482) | (n = 161) | (n = 23) | ||

| Age, yrs | 57.53 ± 10.56 | 61.46 ± 10.29 | 65.88 ± 9.96 | 61.13 ± 9.97 | < 0.001 |

| Males, n% | 374 (91.22) | 422 (87.55) | 128 (79.50) | 18 (78.26) | 0.001 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 25.25 ± 3.20 | 25.33 ± 3.17 | 24.91 ± 3.01 | 23.53 ± 3.33 | 0.035 |

| SBP, mmHg | 127.61 ± 18.53 | 126.80 ± 20.29 | 127.75 ± 20.88 | 135.96 ± 26.52 | 0.188 |

| DBP, mmHg | 73.47 ± 11.59 | 71.64 ± 12.29 | 70.57 ± 12.17 | 76.96 ± 15.86 | 0.008 |

| Smoking, n% | 183 (44.63) | 171 (35.48) | 42 (16.15) | 4 (17.39) | < 0.001 |

| Hypertension, n% | 236 (57.56) | 288 (59.75) | 117 (72.67) | 23 (100) | < 0.001 |

| Diabetes, n% | 138 (33.66) | 147 (30.50) | 79 (49.07) | 10 (43.48) | < 0.001 |

| Previous MI, n% | 164 (40.00) | 193 (40.04) | 75 (46.58) | 11 (47.83) | 0.415 |

| Previous PCI, % | 208 (50.73) | 235 (48.76) | 91 (56.52) | 12 (52.17) | 0.402 |

| Previous CABG, % | 8 (1.95) | 19 (3.94) | 8 (4.97) | 0 (0) | 0.157 |

| Previous stroke, n% | 33 (8.05) | 71 (14.73) | 23 (14.29) | 3 (13.04) | 0.017 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease, n% | 7 (1.71) | 9 (1.87) | 6 (3.73) | 0 (0) | 0.382 |

| Peripheral artery disease, n% | 8 (1.95) | 13 (2.70) | 5 (3.11) | 1 (4.35) | 0.767 |

| Family history of CHD, n% | 17 (4.15) | 18 (3.73) | 6 (3.73) | 3 (13.04) | 0.178 |

| WBC, *109/L | 7.02 ± 1.91 | 6.85 ± 2.13 | 7.09 ± 2.08 | 7.57 ± 2.44 | 0.230 |

| Platelet, *109/L | 212.89 ± 65.54 | 204.05 ± 60.13 | 205.94 ± 76.89 | 211.65 ± 59.90 | 0.228 |

| Hemoglobin, g/L | 143.20 ± 16.98 | 140.12 ± 17.78 | 133.51 ± 23.59 | 109.09 ± 20.98 | < 0.001 |

| FBG, mmol/L | 6.53 ± 2.78 | 6.31 ± 2.94 | 6.59 ± 2.56 | 6.49 ± 3.05 | 0.652 |

| TC, mmol/L | 3.42 ± 1.08 | 3.37 ± 1.00 | 3.33 ± 0.85 | 3.48 ± 0.92 | 0.699 |

| TG, mmol/L | 1.65 ± 1.20 | 1.66 ± 1.02 | 1.64 ± 0.88 | 2.07 ± 1.80 | 0.362 |

| LDL-C, mmol/L | 1.95 ± 0.94 | 1.87 ± 0.88 | 1.84 ± 0.77 | 1.90 ± 0.84 | 0.513 |

| HDL-C, mmol/L | 1.02 ± 0.41 | 1.00 ± 0.34 | 1.01 ± 0.51 | 1.00 ± 0.35 | 0.746 |

| ALT, U/L | 31.66 ± 27.80 | 32.62 ± 41.50 | 31.89 ± 64.41 | 18.76 ± 17.59 | 0.514 |

| AST, U/L | 26.16 ± 27.65 | 27.31 ± 26.56 | 32.30 ± 71.75 | 18.04 ± 10.67 | 0.195 |

| Scr, μmol/L | 66.24 ± 8.19 | 87.25 ± 10.84 | 123.38 ± 23.85 | 390.57 ± 250.96 | < 0.001 |

| eGFR, mL/min per 1.73 m2 | 106.82 ± 14.68 | 75.60 ± 8.53 | 49.71 ± 8.21 | 17.91 ± 8.61 | < 0.001 |

| CrCL, ml/min | 111.52 ± 25.38 | 80.26 ± 18.85 | 52.92 ± 15.47 | 21.03 ± 10.95 | < 0.001 |

| Uric acid, μmol/L | 319.07 ± 81.00 | 355.59 ± 91.93 | 405.48 ± 123.50 | 384.39 ± 143.59 | < 0.001 |

| Hyperuricemia, n% | 41 (10.00) | 97 (20.12) | 58 (36.02) | 12 (52.17) | < 0.001 |

| cTnI, ng/mL | 0.82 ± 8.74 | 0.65 ± 4.87 | 1.81 ± 12.24 | 0.09 ± 0.08 | 0.408 |

| NT-proBNP, pg/ml | 636.34 ± 1516.92 | 953.30 ± 2077.72 | 2358.72 ± 4561.90 | 13576.22 ± 13891.73 | < 0.001 |

| CK, IU/L | 128.94 ± 319.17 | 125.28 ± 190.63 | 163.15 ± 426.96 | 162.94 ± 280.08 | 0.599 |

| CK-MB, IU/L | 17.80 ± 35.28 | 16.40 ± 21.64 | 17.83 ± 28.73 | 21.93 ± 22.74 | 0.821 |

| LVEF, % | 51.70 ± 8.55 | 50.27 ± 9.84 | 46.42 ± 11.32 | 46.35 ± 8.73 | < 0.001 |

| Dyspnea (NYHA functional class), n% | 0.421 | ||||

| I | 112 (27.32) | 133 (27.59) | 39 (24.22) | 6 (26.08) | 0.862 |

| II | 191 (46.59) | 246 (51.04) | 74 (45.96) | 9 (39.13) | 0.411 |

| III | 87 (21.22) | 87 (18.05) | 41 (25.47) | 5 (21.74) | 0.383 |

| IV | 20 (4.88) | 16 (3.32) | 7 (4.35) | 3 (13.04) | 0.224 |

| NYHA functional class (III/IV), n% | 107 (26.10) | 103 (21.37) | 48 (29.81) | 8 (34.78) | 0.078 |

| Medications on discharge, n% | |||||

| Aspirin | 393 (95.85) | 449 (93.15) | 153 (95.03) | 15 (65.22) | < 0.001 |

| P2Y12 inhibitors | 408 (99.51) | 479 (99.38) | 161 (100.00) | 23 (100.00) | 0.772 |

| Statin | 405 (98.78) | 476 (98.76) | 159 (98.76) | 22 (95.65) | 0.637 |

| ACE inhibitors or ARB | 329 (80.24) | 404 (83.82) | 141 (87.58) | 15 (65.22) | 0.021 |

| β-Blockers | 361 (88.05) | 449 (93.15) | 144 (89.44) | 23 (100.00) | 0.022 |

Baseline characteristics.

eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; BMI, body mass index; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; MI, myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; CHD, coronary atherosclerotic heart disease; WBC, white blood cell; FBG, fasting blood glucose; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglyceride; LDL-C, low density lipoprotein cholesterol; HDL-C, high density lipoprotein cholesterol; ALT, alanine aminotransaminase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; Scr, serum creatinine; CrCL, creatinine clearance; cTnI, cardiac troponin I; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro-B type natriuretic peptide; CK, creatine kinase; CK-MB, creatine kinase MB; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; NYHA, New York Heart Association; ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; ARB, angiotensin receptor blockers.

Results

The 1,076 patients were subdivided into four groups according to baseline eGFR. A flowchart of the patient selection process is presented in Figure 1. Overall, lower eGFR tended to occur in older and female CTO patients and those with hypertension, diabetes, hyperuricemia, and previous stroke. Meanwhile, CTO patients with low eGFR generally had lower body mass index, hemoglobin level, creatinine clearance, and left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), and higher diastolic blood pressure, serum creatinine, uric acid, and N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) (p < 0.05, Table 1). Angiographic features and procedural details are shown in Table 2. Among the CTO patients, low eGFR was correlated with a greater number of lesions, CTO of the right coronary artery, and fewer “interventional” collaterals (p < 0.05).

Table 2

|

eGFR ≥90

mL/min/1.73 m2 |

90 > eGFR ≥60

mL/min/1.73 m2 |

60 > eGFR ≥30

mL/min/1.73 m2 |

eGFR < 30

mL/min/1.73 m2 |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 410) | (n = 482) | (n = 161) | (n = 23) | ||

| Vascular lesion, n% | |||||

| LM lesion | 67 (13.34) | 106 (21.99) | 35 (21.74) | 3 (13.04) | 0.132 |

| LAD lesion | 341 (83.17) | 399 (82.78) | 141 (87.57) | 20 (86.96) | 0.505 |

| LCX lesion | 293 (71.46) | 348 (72.20) | 128 (79.50) | 17 (73.91) | 0.249 |

| RCA lesion | 312 (76.10) | 391 (81.12) | 132 (81.99) | 18 (78.26) | 0.235 |

| Multivessel disease, n% | 351 (85.61) | 413 (85.68) | 148 (91.93) | 19 (82.60) | 0.178 |

| Number of lesions per patient | 2.38 ± 0.97 | 2.51 ± 0.97 | 2.63 ± 0.93 | 2.26 ± 1.14 | 0.017 |

| Location of the CTO, n% | |||||

| LM-CTO | 4 (0.98) | 5 (1.04) | 1 (0.62) | 0 (0) | 0.929 |

| LAD-CTO | 195 (47.56) | 228 (47.30) | 63 (39.13) | 10 (43.48) | 0.279 |

| LCX-CTO | 116 (28.29) | 141 (29.25) | 57 (35.40) | 8 (34.78) | 0.364 |

| RCA-CTO | 231 (56.34) | 279 (57.88) | 112 (69.57) | 13 (56.52) | 0.030 |

| Multi-CTO lesion, n% | 118 (28.78) | 148 (30.71) | 58 (36.02) | 7 (30.43) | 0.415 |

| Number of CTO per patient | 1.33 ± 0.55 | 1.35 ± 0.57 | 1.45 ± 0.65 | 1.35 ± 0.57 | 0.180 |

| CTO target vessel, n% | |||||

| LM-CTO | 2 (0.49) | 5 (1.04) | 1 (0.62) | 0 (0) | 0.769 |

| LAD-CTO | 162 (39.51) | 194 (40.25) | 47 (29.19) | 10 (43.48) | 0.074 |

| LCX-CTO | 63 (15.37) | 70 (14.52) | 24 (14.90) | 2 (8.70) | 0.846 |

| RCA-CTO | 200 (48.78) | 231 (47.93) | 96 (59.63) | 12 (52.17) | 0.069 |

| Ostial location, n% | 52 (12.68) | 42 (8.71) | 9 (5.59) | 4 (17.39) | 0.028 |

| In-stent occlusion, n% | 39 (9.51) | 36 (7.47) | 14 (8.70) | 0 (0) | 0.340 |

| Lesion length, mm | 27.91 ± 22.18 | 27.78 ± 16.81 | 28.75 ± 17.98 | 31.58 ± 26.81 | 0.816 |

| Lesion length ≥20 mm, n% | 277 (67.56) | 315 (65.35) | 101 (62.73) | 12 (52.17) | 0.372 |

| Blunt stump, n% | 277 (67.56) | 335 (69.50) | 106 (65.84) | 15 (65.22) | 0.811 |

| Tortuosity ≥45°, n% | 101 (24.63) | 145 (30.08) | 55 (34.16) | 5 (21.74) | 0.084 |

| Calcification, n% | 137 (33.41) | 168 (34.85) | 41 (25.47) | 10 (43.48) | 0.109 |

| Reattempt, n% | 75 (18.29) | 68 (14.11) | 24 (14.91) | 3 (13.04) | 0.365 |

| J-CTO score | 2.18 ± 1.14 | 2.19 ± 1.13 | 2.12 ± 1.16 | 2.37 ± 1.38 | 0.819 |

| SYNTAX score | 29.33 ± 11.65 | 30.68 ± 12.17 | 31.42 ± 11.63 | 28.03 ± 10.36 | 0.233 |

| Proximal cap side-branch, n% | 324 (79.02) | 355 (73.65) | 120 (74.53) | 14 (60.87) | 0.094 |

| “Interventional” collaterals, n% | 298 (72.68) | 339 (70.33) | 110 (68.32) | 15 (65.22) | 0.005 |

| Diseased distal landing zone, n% | 195 (47.56) | 250 (51.86) | 81 (50.31) | 9 (39.13) | 0.439 |

| Contrast volume, ml | 353.39 ± 157.71 | 372.50 ± 252.11 | 364.91 ± 257.59 | 342.17 ± 91.60 | 0.592 |

| Procedural time, min | 119.40 ± 68.41 | 115.62 ± 67.17 | 120.24 ± 67.17 | 148.65 ± 80.58 | 0.150 |

| Procedural success, n% | 377 (91.95) | 441 (91.49) | 143 (88.82) | 21 (91.30) | 0.687 |

Angiographic characteristics and procedural details.

eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; LM, left main coronary artery; LAD, left anterior descending coronary artery; LCX, left circumtrunnion coronary artery; RCA, right coronary artery; CTO, chronic total occlusion; J-CTO, multicenter CTO registry in Japan; SYNTAX, Synergy Between PCI With Taxus and Cardiac Surgery.

Intraprocedural and in-hospital complications are shown in Table 3. There was no significant difference in the occurrence of intraprocedural complications and in-hospital MACE with decreased eGFR (p > 0.05). However, the incidence of other in-hospital complications, including pericardiocentesis, major bleeding, acute renal failure, and subcutaneous hematoma, were significantly higher (p < 0.05). Moreover, in the univariable and multivariable analysis of the CTO patients with low eGFR (<90 mL/min/1.73 m2) after successful revascularization, peripheral artery disease (OR: 5.778, 95% CI: 1.922–17.372, p = 0.002), lower platelet (OR: 0.993, 95% CI: 0.988–0.997, p = 0.002) and hemoglobin (OR: 0.982, 95% CI: 0.969–0.994, p = 0.003), higher uric acid (OR: 1.003, 95% CI: 1.001–1.005, p = 0.013), and calcification (OR: 1.852, 95% CI: 1.104–3.109, p = 0.020) independently increased the risk of in-hospital complications (Table 4).

Table 3

|

eGFR ≥90

mL/min/1.73 m2 |

90> e GFR ≥60

mL/min/1.73 m2 |

60 > eGFR ≥30

mL/min/1.73 m2 |

eGFR < 30

mL/min/1.73 m2 |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 410) | (n = 482) | (n = 161) | (n = 23) | ||

| Intraprocedural complications | |||||

| All-cause mortality, n% | 2 (0.49) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.354 |

| Cardiac mortality, n% | 2 (0.49) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.354 |

| Cardiac arrest, n% | 1 (0.24) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.654 |

| Malignant arrhythmia, n% | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | – |

| Pericardial tamponade, n% | 1 (0.24) | 1 (0.21) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.934 |

| Pericardiocentesis, n% | 1 (0.24) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.654 |

| Stroke, n% | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | – |

| Vascular dissection, n% | 8 (1.95) | 12 (2.49) | 2 (1.24) | 1 (4.35) | 0.680 |

| Collateral vessel perforation, n% | 3 (0.73) | 3 (0.62) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.731 |

| Loss of side branch ≥2 mm, n% | 6 (1.46) | 4 (0.83) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.384 |

| Acute renal failure, n% | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | – |

| Contrast allergy-related shock, n% | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | – |

| Vasovagal response, n% | 0 (0) | 1 (0.21) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.745 |

| In-hospital complications | |||||

| MACE, n% | 17 (4.15) | 21 (4.37) | 10 (6.21) | 1 (4.3) | 0.748 |

| All-cause mortality, n% | 3 (0.73) | 1 (0.21) | 3 (1.86) | 0 (0) | 0.150 |

| Cardiac mortality, n% | 3 (0.73) | 1 (0.21) | 3 (1.86) | 0 (0) | 0.150 |

| Non-fatal MI, n% | 5 (1.22) | 7 (1.45) | 4 (2.48) | 1 (4.35) | 0.499 |

| Clinically driven revascularization, n% | 9 (2.20) | 13 (2.70) | 4 (2.48) | 1 (4.35) | 0.907 |

| Emergency PCI | 9 (2.20) | 13 (2.70) | 4 (2.48) | 1 (4.35) | 0.907 |

| Emergency CABG | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | - |

| Other complications | 24 (5.85) | 49 (10.2) | 25 (15.53) | 7 (30.43) | < 0.001 |

| Pericardiocentesis, n% | 0 (0) | 3 (0.62) | 1 (0.62) | 2 (8.70) | < 0.001 |

| Cardiac arrest, n% | 1 (0.24) | 5 (1.04) | 2 (1.24) | 0 (0) | 0.446 |

| Malignant arrhythmia, n% | 1 (0.24) | 7 (1.45) | 2 (1.24) | 0 (0) | 0.271 |

| Cardiac shock, n% | 3 (0.73) | 5 (1.04) | 1 (0.62) | 1 (4.35) | 0.345 |

| Major bleeding, n% | 17 (4.15) | 21 (4.36) | 18 (11.18) | 6 (26.09) | < 0.001 |

| Allergy-related shock, n% | 1 (0.24) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.62) | 0 (0) | 0.447 |

| Acute renal failure, n% | 0 (0) | 1 (0.21) | 2 (1.24) | 2 (8.70) | < 0.001 |

| Subcutaneous hematoma, n% | 6 (1.46) | 22 (4.56) | 8 (4.97) | 1 (4.35) | 0.049 |

Intraprocedural and in-hospital complications.

eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; MACE, major adverse cardiac event; MI, myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting.

Table 4

| Univariable analysis | Multivariable analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95%CI | p-Vvlue | OR | 95%CI | p-value | |

| Peripheral artery disease | 5.951 | 2.350–15.066 | < 0.001 | 5.778 | 1.922–17.372 | 0.002 |

| Previous MI | 1.702 | 1.098–2.638 | 0.017 | |||

| Platelet | 0.994 | 0.990–0.998 | 0.003 | 0.993 | 0.988–0.997 | 0.002 |

| Hemoglobin | 0.979 | 0.968–0.989 | < 0.001 | 0.982 | 0.969–0.994 | 0.003 |

| CrCL | 0.982 | 0.972–0.992 | < 0.001 | |||

| eGFR | 0.980 | 0.969–0.992 | 0.001 | |||

| Uric acid | 1.004 | 1.002–1.006 | < 0.001 | 1.003 | 1.001–1.005 | 0.013 |

| Multivessel disease | 2.936 | 1.157–7.450 | 0.023 | |||

| Multi-CTO lesion | 1.708 | 1.094–2.669 | 0.019 | |||

| Calcification | 2.326 | 1.495–3.618 | < 0.001 | 1.852 | 1.104–3.109 | 0.020 |

| J-CTO score | 1.378 | 1.124–1.690 | 0.002 | |||

Univariable and multivariable logistic regression for in-hospital complications in patients with low eGFR (<90 mL/min/1.73 m2) after successful CTO-PCI.

eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; CTO, chronic total occlusion; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; MI, myocardial infarction; CrCL, creatinine clearance; J-CTO, multicenter CTO registry in Japan; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidential interval.

Successful CTO-PCI significantly alleviated symptoms of dyspnea and angina in almost all patients at 1 month and 1 year, except those with eGFR<30 mL/min/1.73 m2 (Tables 5A,B). Notably, at 1 month, RDS scores had significantly decreased and SAQ-AS and SAQ-AF scores increased for all patients after successful CTO-PCI regardless of decreased eGFR (p < 0.01). Interestingly, changes to the RDS and SAQ scores were similar among all four groups (p > 0.05), indicating that successful CTO-PCI significantly alleviated symptoms of all CTO patients. At 1 year, RDS scores had remarkably decreased and SAQ-AS and SAQ-AF scores increased (p < 0.01) among patients with eGFR ≥30 mL/min/1.73 m2, while there were no significant changes in RDS and SAQ scores among those with eGFR < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2 (p < 0.01), demonstrating remarkable relief of symptoms for patients with low eGFR at 1 year after successful CTO-PCI, except those with eGFR <30 mL/min/1.73 m2. Additionally, after univariable and multivariable analysis, we found multi-CTO lesion (OR: 1.558, 95% CI: 1.077–2.254, p = 0.019) and tortuosity ≥45° (OR: 1.701, 95% CI: 1.182–2.449, p = 0.004) were independent risk factors for 1-year angina improvement in patients with low eGFR (<90 mL/min/1.73 m2) after successful CTO-PCI (Table 6).

Table 5A

| RDS | ||

|---|---|---|

| eGFR ≥90 mL/min/1.73 m2 | Baseline | 1.08 ± 1.08 |

| 1 month follow-up | 0.24 ± 0.54 | |

| 1 year follow-up | 0.47 ± 0.68 | |

| mΔ | 0.86 ± 1.18 | |

| yΔ | 0.69 ± 1.25 | |

| m p-value | < 0.001 | |

| y p-value | < 0.001 | |

| 90 > eGFR ≥ 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 | Baseline | 1.03 ± 1.12 |

| 1 month follow-up | 0.20 ± 0.49 | |

| 1 year follow-up | 0.48 ± 0.66 | |

| mΔ | 0.84 ± 1.18 | |

| yΔ | 0.61 ± 1.23 | |

| m p-value | < 0.001 | |

| y p-value | < 0.001 | |

| 60 > eGFR ≥ 30 mL/min/1.73 m2 | Baseline | 0.98 ± 1.06 |

| 1 month follow-up | 0.28 ± 0.61 | |

| 1 year follow-up | 0.54 ± 0.66 | |

| mΔ | 0.71 ± 1.23 | |

| yΔ | 0.50 ± 1.16 | |

| m p-value | < 0.001 | |

| y p-value | < 0.001 | |

| eGFR < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2 | Baseline | 1.05 ± 1.07 |

| 1 month follow-up | 0.17 ± 0.51 | |

| 1 year follow-up | 0.58 ± 0.79 | |

| mΔ | 0.90 ± 1.04 | |

| yΔ | 0.71 ± 1.27 | |

| m p-value | 0.003 | |

| y p-value | 0.201 | |

| a p-value | 0.518 | |

| b p-value | 0.215 |

Comparison of changes in RDS from baseline to follow-up.

RDS, rose dyspnea scale; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate.

m Δ: change between baseline and 1 month follow-up.

y Δ: change between baseline and 1 year follow-up.

m p-value: baseline vs. 1 month follow-up.

y p-value: baseline vs. 1 year follow-up.

a p-value: comparison of mΔ in the four groups.

b p-value: comparison of yΔ in the four groups.

Table 5B

| SAQ-PL | SAQ-AS | SAQ-AF | SAQ-TS | SAQ-DP | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| eGFR ≥90 mL/min/1.73 m2 | Baseline | 63.14 ± 14.18 | 50.27 ± 15.36 | 78.51 ± 24.84 | 81.25 ± 14.82 | 72.28 ± 17.79 |

| 1 month follow-up | 68.25 ± 13.13 | 71.41 ± 23.83 | 97.86 ± 83.37 | 84.09 ± 11.73 | 72.14 ± 15.05 | |

| 1 year follow-up | 68.04 ± 12.17 | 74.44 ± 25.90 | 95.08 ± 9.88 | 85.87 ± 9.92 | 78.06 ± 15.57 | |

| mΔ | 4.96 ± 19.58 | 21.34 ± 27.95 | 19.89 ± 25.77 | 2.54 ± 16.62 | 0.21 ± 21.68 | |

| yΔ | 5.58 ± 17.56 | 24.60 ± 29.72 | 18.15 ± 26.34 | 3.82 ± 17.69 | 5.96 ± 24.63 | |

| m p-value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.008 | 0.831 | |

| y p-value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |

| 90 > eGFR ≥ 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 | Baseline | 63.97 ± 14.99 | 50.11 ± 16.94 | 78.66 ± 24.49 | 79.23 ± 15.11 | 69.27 ± 19.34 |

| 1 month follow-up | 69.09 ± 13.52 | 71.23 ± 23.95 | 98.16 ± 6.90 | 83.48 ± 11.19 | 72.78 ± 13.13 | |

| 1 year follow-up | 67.58 ± 12.29 | 71.61 ± 26.83 | 94.53 ± 10.36 | 87.07 ± 10.24 | 79.17 ± 15.63 | |

| mΔ | 4.91 ± 19.14 | 21.23 ± 29.53 | 19.79 ± 24.70 | 4.18 ± 16.90 | 3.44 ± 22.19 | |

| yΔ | 3.97 ± 18.09 | 21.42 ± 32.50 | 17.24 ± 26.46 | 7.63 ± 19.22 | 10.00 ± 25.97 | |

| m p-value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.005 | |

| y p-value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |

| 60 > eGFR ≥ 30 mL/min/1.73 m2 | Baseline | 59.30 ± 17.38 | 49.65 ± 18.53 | 74.55 ± 27.24 | 79.47 ± 15.64 | 66.20 ± 19.48 |

| 1 month follow-up | 67.30 ± 14.77 | 72.22 ± 24.37 | 98.30 ± 7.68 | 83.49 ± 11.21 | 69.14 ± 13.28 | |

| 1 year follow-up | 65.95 ± 14.25 | 64.06 ± 32.57 | 91.88 ± 16.59 | 88.37 ± 10.35 | 78.58 ± 16.72 | |

| mΔ | 7.42 ± 20.41 | 22.59 ± 32.88 | 24.15 ± 27.44 | 3.83 ± 18.20 | 3.46 ± 22.01 | |

| yΔ | 6.42 ± 20.19 | 14.45 ± 35.72 | 18.83 ± 32.55 | 8.87 ± 19.22 | 13.48 ± 26.77 | |

| m p-value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.015 | 0.145 | |

| y p-value | 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |

| eGFR < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2 | Baseline | 59.15 ± 15.72 | 52.38 ± 10.91 | 82.86 ± 21.25 | 79.27 ± 10.94 | 66.27 ± 17.38 |

| 1 month follow-up | 68.64 ± 11.83 | 75.00 ± 24.25 | 97.22 ± 6.69 | 83.33 ± 11.46 | 68.98 ± 13.35 | |

| 1 year follow-up | 61.48 ± 18.82 | 58.33 ± 35.89 | 92.50 ± 12.88 | 85.29 ± 8.87 | 78.47 ± 15.27 | |

| mΔ | 11.23 ± 18.27 | 23.61 ± 24.96 | 17.22 ± 21.09 | 3.27 ± 13.72 | 4.63 ± 19.85 | |

| yΔ | 3.89 ± 14.44 | 8.33 ± 38.92 | 6.67 ± 16.70 | 4.90 ± 14.15 | 13.89 ± 16.02 | |

| m p-value | 0.043 | < 0.001 | 0.009 | 0.265 | 0.593 | |

| y p-value | 0.706 | 0.482 | 0.164 | 0.115 | 0.052 | |

| a p-value | 0.318 | 0.955 | 0.309 | 0.597 | 0.177 | |

| b p-value | 0.499 | 0.012 | 0.500 | 0.019 | 0.025 |

Comparison of changes in SAQ subscales from baseline to follow-up.

SAQ, seattle angina questionnaire; SAQ-PL, seattle angina questionnaire-physical limitation; SAQ-AS, seattle angina questionnaire-anginal stability; SAQ-AF, seattle angina questionnaire-anginal frequency; SAQ-TS, seattle angina questionnaire-treatment satisfaction; SAQ-DP, seattle angina questionnaire-disease perception; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate.

m Δ: change between baseline and 1 month follow-up.

y Δ: change between baseline and 1 year follow-up.

m p-value: baseline vs. 1 month follow-up.

y p-value: baseline vs. 1 year follow-up.

a p-value: comparison of mΔ in the four groups.

b p-value: comparison of yΔ in the four groups.

Table 6

| Univariable analysis | Multivariable analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95%CI | p-value | OR | 95%CI | p-value | |

| Multi-CTO lesion | 1.451 | 1.016–2.073 | 0.041 | 1.558 | 1.077–2.254 | 0.019 |

| Lesion length | 1.012 | 1.002–1.023 | 0.015 | |||

| Tortuosity ≥ 45° | 1.711 | 1.195–2.449 | 0.003 | 1.701 | 1.182–2.449 | 0.004 |

Univariable and multivariable logistic regression for 1-year angina improvement in patients with low eGFR (<90 mL/min/1.73 m2) after successful CTO-PCI.

eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; CTO, chronic total occlusion; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidential interval.

Most importantly, this prospective study is the first to use the EQ-5D questionnaire to assess QOL of CTO patients with low eGFR. Surprisingly, at 1 month and 1 year after successful CTO-PCI, the EQ-5D scores of all patients had remarkably increased (p < 0.05) with similar improvement achieved by all four groups (p > 0.05, Table 7). Moreover, age (OR: 1.021, 95% CI: 1.003–1.039, p = 0.019) was an independent risk factor for 1-year QOL improvement in CTO patients with low eGFR (<90 mL/min/1.73 m2) after successful PCI (Table 8).

Table 7

| EQ-5D | ||

|---|---|---|

| eGFR ≥90 mL/min/1.73 m2 | Baseline | 0.89 ± 0.17 |

| 1 month follow-up | 0.96 ± 0.11 | |

| 1 year follow-up | 0.96 ± 0.11 | |

| mΔ | 0.07 ± 0.19 | |

| yΔ | 0.07 ± 0.20 | |

| m p-value | < 0.001 | |

| y p-value | < 0.001 | |

| 90 > eGFR ≥ 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 | Baseline | 0.89 ± 0.16 |

| 1 month follow-up | 0.97 ± 0.09 | |

| 1 year follow-up | 0.96 ± 0.10 | |

| mΔ | 0.07 ± 0.17 | |

| yΔ | 0.06 ± 0.18 | |

| m p-value | < 0.001 | |

| y p-value | < 0.001 | |

| 60 > eGFR ≥ 30 mL/min/1.73 m2 | Baseline | 0.87 ± 0.18 |

| 1 month follow-up | 0.95 ± 0.12 | |

| 1 year follow-up | 0.95 ± 0.11 | |

| mΔ | 0.08 ± 0.21 | |

| yΔ | 0.08 ± 0.22 | |

| m p-value | < 0.001 | |

| y p-value | < 0.001 | |

| eGFR < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2 | Baseline | 0.80 ± 0.23 |

| 1 month follow-up | 0.98 ± 0.08 | |

| 1 year follow-up | 0.95 ± 0.11 | |

| mΔ | 0.19 ± 0.24 | |

| yΔ | 0.13 ± 0.29 | |

| m p-value | 0.003 | |

| y p-value | 0.036 | |

| a p-value | 0.052 | |

| b p-value | 0.640 |

Changes of EQ-5D in patients with successful CTO-PCI.

CTO, chronic total occlusion; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; EQ-5D, European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate.

m Δ: change between baseline and 1 month follow-up.

y Δ: change between baseline and 1 year follow-up.

m p-value: baseline vs. 1 month follow-up.

y p-value: baseline vs. 1 year follow-up.

a p-value: comparison of mΔ in the four groups.

b p-value: comparison of yΔ in the four groups.

Table 8

| OR | 95%CI | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.021 | 1.003–1.039 | 0.019 |

Univariable logistic regression for 1-year QOL improvement in patients with low eGFR (<90 mL/min/1.73 m2) after successful CTO-PCI.

eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; CTO, chronic total occlusion; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidential interval.

These data demonstrate that successful CTO-PCI remarkably improved QOL of patients regardless of decreased eGFR and the degree of improvement was similar for patients with low and normal eGFR.

Discussion

This is the first prospective study to comprehensively evaluate the effect of successful CTO-PCI on QOL of CTO patients with low eGFR. The main findings were as follows: (1) CTO patients with decreased eGFR tended to have more hypertension, diabetes, hyperuricemia, and previous stroke, in addition to lower hemoglobin and LVEF; (2) the incidence of in-hospital MACE was not increased, while there were significant increases in the frequency of pericardiocentesis, major bleeding, acute renal failure, and subcutaneous hematoma with decreased eGFR; (3) successful CTO-PCI significantly alleviated symptoms of all patients with eGFR ≥30 mL/min/1.73 m2 at 1 month and 1 year, but only at 1 month among those with eGFR <30 mL/min/1.73 m2; and (4) successful CTO-PCI significantly improved QOL regardless of eGFR at 1 month and 1 year to a similar degree for patients with low and normal eGFR. The real world study demonstrated that successful CTO-PCI improved QOL of patients with low eGFR.

Notably, low eGFR (<90 mL/min/1.73 m2) is fairly common in CTO patients, accounting for ~44.70–72.07% (16, 17, 21). In our study, low eGFR presented in 61.90% of CTO patients, consistent with the results of prior studies. Numerous studies reported that CTO patients with low eGFR were associated with higher proportion of comorbidities, including hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, and low LVEF (13, 15, 17), which may be led by that renal impairment is associated with retention of sodium and water, inflammation, oxidative stress, metabolic perturbations (especially the disorder of lipid and lipoprotein metabolism), myocardial damage, and coronary microcirculation disorders (30, 31). Therefore, low eGFR was limited to a subset of CTO patients at high risk for the increased incidence of MCAE (11, 13, 14, 16, 17). According to the data obtained in this study, CTO patients with decreased eGFR who tended to be older and with hypertension and diabetes were a greater risk for CVD. Additionally, CTO patients with low eGFR were at greater risk for poorer cardiac function, manifested by significantly higher NT-proBNP and lower LVEF, which may be the important reason for the poor prognosis of CTO patients with low eGFR (12, 14–17). Additionally, we found that low eGFR was correlated with fewer “interventional” collaterals while no other researches have reported the correlation between low eGFR and “interventional” collaterals as of today. Werner et al. speculated that there may be some possible clinical determinants which damage collaterals, including diabetes, left ventricular (LV) function, myocardial viability, and angiographic factors such as collateral anatomy and size (32). In our study, CTO patients with low eGFR were found with more diabetes and worse LV function (low LVEF), indicating that the fewer “interventional” collaterals in low eGFR patients may somehow associate with the increased diabetes and worse LV function. However, we still need to further identify whether low eGFR directly damages the “interventional” collaterals and its potential mechanism.

Regarding the procedural safety and effectiveness for CTO patients with low eGFR previous literature has not been thoroughly compared and described. In the present study, we found not only the procedural success rate was not markedly reduced, but the occurrences of intraprocedural complications and in-hospital MACE were not significantly increased for CTO patients with low eGFR, indicating that revascularization is both safe and feasible for these patients. However, the incidence of bleeding-related adverse events, including pericardiocentesis, major bleeding, and subcutaneous hematoma, were markedly higher for CTO patients with low eGFR, similar to the findings of previous studies (33). These higher incidences of bleeding in low eGFR patients may be caused by platelet dysfunction, an imbalance in mediators of normal endothelial function, co-morbidities, such as vascular disease, hypertension, and anemia, and medical interventions for treatment of such co-morbidities (34–37). Additionally, the incidence of acute renal failure was higher in CTO patients with low eGFR, especially those with eGFR <30 mL/min/1.73 m2, indicating that safe contrast limits and aggressive periprocedural hydration for the subset of patients should be strictly considered. These findings confirm that with adequate preprocedural assessment and critical post-procedural care, timely CTO-PCI for patients with low eGFR is both safe and feasible.

The Global Expert Consensus Document states that the principal indication of CTO-PCI is improving symptoms (18). Successful CTO-PCI can significantly improve symptoms of dyspnea and angina (38–40). Additionally, studies reported that low eGFR was usually associated with multiple bothersome symptoms, including dyspnea, fatigue, depression and anxiety, and low eGFR was common in symptomatic CTO patients (19, 41). However, the impact of successful CTO-PCI on symptoms of CTO patients with low eGFR remains unclear, as only one study to date has reported that successful CTO-PCI significantly relieved symptoms of angina and dyspnea for patients with low eGFR at 1 month and 1 year (21). Similarly, in the present study, we further validated that successful CTO-PCI significantly relieved symptoms of CTO patients with eGFR ≥30 mL/min/1.73 m2 at 1 month and 1 year. Notably, for CTO patients with eGFR<30 mL/min/1.73 m2, successful PCI improved symptoms at 1 month with no significant difference at 1 year, which was inconsistent with the study cited above. Therefore, future large-sample randomized controlled trials are warranted to further assess the impact of successful CTO-PCI on symptoms of CTO patients with low eGFR, especially those with eGFR <30 mL/min/1.73 m2, aiming to provide stronger evidences for clinical practices. Additionally, we found that multi-CTO lesion was an independent risk factor for 1-year angina improvement in patients with low eGFR (<90 mL/min/1.73 m2) after successful CTO-PCI, which may be caused by that myocardial viability of patients with multi-CTO lesion was worse and the improvement of regional myocardial function after revascularization was poorer than those with single-CTO lesion, thereby leading to the less improvement of 1-year angina.

QOL is well-recognized as a critical indicator to assess status and perceptions of both physical and mental health (42). Independent of preventing MACE and relieving symptoms, it is imperative to determine whether successful CTO-PCI improved QOL (43). The DECISION-CTO (Drug-Eluting Stent Implantation vs. Optimal Medical Treatment in Patients With Chronic Total Occlusion) trial (n = 417) reported that CTO-PCI significantly improved QOL, as determined with the EQ-5D questionnaire, at 1 month and these improvements were largely maintained at 12 and 36 months (23). The EUROCTO (Evaluate the Utilization of Revascularization or Optimal Medical Therapy for the Treatment of Chronic Total Coronary Occlusions) trial (n = 259), which also used the EQ-5D questionnaire, found that successful CTO-PCI greatly improved QOL of patients at 12 months (44). Renal impairment has an enormous impact on an individual's QOL and QOL is significantly reduced with the decrease of eGFR, which may be caused by increased suffering from chronic illness (e.g., hypertension, diabetes, congestive heart failure, and cancer) and multiple physical and psychological symptoms (e.g., pain, dyspnea, fatigue, sleep disturbances, nausea and vomiting, cognitive impairment, and anxiety and depression) (20, 41, 45). However, the two RCT did not specify the QOL in the CTO patients with low eGFR, and to our knowledge, our study is the first prospective clinical trial to investigate the impact of successful CTO-PCI on QOL of CTO patients with low eGFR. To address this critical knowledge gap in clinical practice, we used the EQ-5D questionnaire and found that successful CTO-PCI remarkably improved QOL of CTO patients with low and normal eGFR at 1 month and 1 year.

Study limitations

There were some limitations to this study that should be addressed. First, the single-team nature of this study is a potential weakness that may be not suitable for other centers and teams. Second, the number of CTO patients with eGFR <30 mL/min/1.73 m2 was relatively small with significant differences as compared to other groups and may have resulted in statistical bias, which is difficult to avoid in a real-world study. Third, this study did not include patients who were either not provided PCI or referred for surgical revascularization. Finally, objective measurements of physical capacities, such as those from exercise stress testing, were not systematically conducted during the follow-up.

Conclusion

The results of the present study demonstrated that timely and successful CTO-PCI achieved substantial symptom relief and improved QOL of patients with low eGFR, although the risks of MACE and all-cause mortality were not effectively reduced.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Ethics Committee of Xijing Hospital (Approval No. KY20172019-1). The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

SZ, YC, BZ, KL, CL, and HG were involved in the study design and drafted the manuscript. JW, ZW, YZ, WH, GC, TY, and PH collected data and performed the follow-up for this study. SZ, BZ, WW, and ZZ conducted statistical analysis. HW, CX, and LY researched data and contributed to discussion. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1.

Tajstra M Pyka L Gorol J Pres D Gierlotka M Gadula-Gacek E et al . Impact of chronic total occlusion of the coronary artery on long-term prognosis in patients with ischemic systolic heart failure: insights from the COMMIT-HF registry. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. (2016) 9:1790–7. 10.1016/j.jcin.2016.06.007

2.

Tomasello SD Boukhris M Giubilato S Marzà F Garbo R Contegiacomo G et al . Management strategies in patients affected by chronic total occlusions: results from the Italian Registry of Chronic Total Occlusions. Eur Heart J. (2015) 36:3189–98. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv450

3.

Guo L Lv H Yin X . Chronic total occlusion percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with prior coronary artery bypass graft: current evidence and future perspectives. Front Cardiovasc Med. (2022) 9:753250. 10.3389/fcvm.2022.753250

4.

El Awady WS Samy M Al-Daydamony MM Abd El Samei MM Shokry K . Periprocedural and clinical outcomes of percutaneous coronary intervention of chronic total occlusions in patients with low- and mid-range ejection fractions. Egypt Heart J. (2020) 72:28. 10.1186/s43044-020-00065-1

5.

Galassi AR Boukhris M Toma A Elhadj Z Laroussi L Gaemperli O et al . Percutaneous coronary intervention of chronic total occlusions in patients with low left ventricular ejection fraction. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. (2017) 10:2158–70. 10.1016/j.jcin.2017.06.058

6.

Sirnes PA Myreng Y Mølstad P Bonarjee V Golf S . Improvement in left ventricular ejection fraction and wall motion after successful recanalization of chronic coronary occlusions. Eur Heart J. (1998) 19:273–81. 10.1053/euhj.1997.0617

7.

George S Cockburn J Clayton TC Ludman P Cotton J Spratt J et al . Long-term follow-up of elective chronic total coronary occlusion angioplasty: analysis from the U.K. Central Cardiac Audit Database. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2014) 64:235–43. 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.04.040

8.

Guo L Wu J Zhong L Ding H Xu J Zhou X et al . Two-year clinical outcomes of medical therapy vs. revascularization for patients with coronary chronic total occlusion. Hellenic J Cardiol. (2020) 61:264–71. 10.1016/j.hjc.2019.03.006

9.

Yan Y Zhang M Yuan F Liu H Wu D Fan Y et al . Successful revascularization versus medical therapy in diabetic patients with stable right coronary artery chronic total occlusion: a retrospective cohort study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. (2019) 18:108. 10.1186/s12933-019-0911-4

10.

Sarnak MJ Levey AS Schoolwerth AC Coresh J Culleton B Hamm LL et al . Kidney disease as a risk factor for development of cardiovascular disease: a statement from the American Heart Association Councils on Kidney in Cardiovascular Disease, High Blood Pressure Research, Clinical Cardiology, and Epidemiology and Prevention. Circulation. (2003) 108:2154–69. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000095676.90936.80

11.

Lee WC Wu PJ Fang CY Chen HC Wu CJ Fang HY . Impact of chronic kidney disease on chronic total occlusion revascularization outcomes: a meta-analysis. J Clin Med. (2021) 10:440. 10.3390/jcm10030440

12.

Flores-Umanzor E Cepas-Guillen P Álvarez-Contreras L Caldentey G Castrillo-Golvano L Fernandez-Valledor A et al . Impact of chronic kidney disease in chronic total occlusion management and clinical outcomes. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. (2022) 38:75–80. 10.1016/j.carrev.2021.07.018

13.

Shimura T Yamamoto M Tsuchikane E Teramoto T Kimura M Matsuo H et al . Rates of future hemodialysis risk and beneficial outcomes for patients with chronic kidney disease undergoing recanalization of chronic total occlusion. Int J Cardiol. (2016) 222:707–13. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.08.019

14.

Naganuma T Tsujita K Mitomo S Ishiguro H Basavarajaiah S Sato K et al . Impact of chronic kidney disease on outcomes after percutaneous coronary intervention for chronic total occlusions (from the Japanese multicenter registry). Am J Cardiol. (2018) 121:1519–23. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2018.02.032

15.

Azzalini L Ojeda S Demir OM Dens J Tanabe M La Manna A et al . Recanalization of chronic total occlusions in patients with vs without chronic kidney disease: the impact of contrast-induced acute kidney injury. Can J Cardiol. (2018) 34:1275–82. 10.1016/j.cjca.2018.07.012

16.

Stähli BE Gebhard C Gick M Ferenc M Mashayekhi K Buettner HJ et al . Outcomes after percutaneous coronary intervention for chronic total occlusion according to baseline renal function. Clin Res Cardiol. (2018) 107:259–67. 10.1007/s00392-017-1179-x

17.

Guo L Ding H Lv H Zhang X Zhong L Wu J et al . Impact of renal function on long-term clinical outcomes in patients with coronary chronic total occlusions: results from an observational single-center cohort study during the last 12 years. Front Cardiovasc Med. (2020) 7:550428. 10.3389/fcvm.2020.550428

18.

Brilakis ES Mashayekhi K Tsuchikane E Abi Rafeh N Alaswad K Araya M et al . Guiding principles for chronic total occlusion percutaneous coronary intervention. Circulation. (2019) 140:420–433. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.039797

19.

Odden MC Whooley MA Shlipak MG . Association of chronic kidney disease and anemia with physical capacity: the heart and soul study. J Am Soc Nephrol. (2004) 15:2908–15. 10.1097/01.ASN.0000143743.78092.E3

20.

Faulhaber L Herget-Rosenthal S Jacobs H Hoffmann F . Health-related quality of life according to renal function: results from a nationwide health interview and examination survey. Kidney Blood Press Res. (2022) 47:13–22. 10.1159/000518668

21.

Malik AO Spertus JA Grantham JA Peri-Okonny P Gosch K Sapontis J et al . Outcomes of chronic total occlusion percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with renal dysfunction. Am J Cardiol. (2020) 125:1046–53. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2019.12.045

22.

Levey AS Coresh J Greene T Stevens LA Zhang YL Hendriksen S et al . Using standardized serum creatinine values in the modification of diet in renal disease study equation for estimating glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. (2006) 145:247–54. 10.7326/0003-4819-145-4-200608150-00004

23.

Lee SW Lee PH Ahn JM Park DW Yun SC Han S et al . Randomized trial evaluating percutaneous coronary intervention for the treatment of chronic total occlusion. Circulation. (2019) 139:1674–83. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.031313

24.

Morino Y Abe M Morimoto T Kimura T Hayashi Y Muramatsu T et al . Predicting successful guidewire crossing through chronic total occlusion of native coronary lesions within 30 minutes: the J-CTO (Multicenter CTO Registry in Japan) score as a difficulty grading and time assessment tool. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. (2011) 4:213–21. 10.1016/j.jcin.2010.09.024

25.

Koo BK Kang J Park KW Rhee TM Yang HM Won KB et al . Aspirin versus clopidogrel for chronic maintenance monotherapy after percutaneous coronary intervention (HOST-EXAM): an investigator-initiated, prospective, randomised, open-label, multicentre trial. Lancet. (2021) 397:2487–96. 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01063-1

26.

Rose GA Blackburn H . Cardiovascular survey methods. Monogr Ser World Health Organ. (1968) 56:1–188.

27.

Spertus JA Winder JA Dewhurst TA Deyo RA Prodzinski J McDonnell M et al . Development and evaluation of the Seattle Angina questionnaire: a new functional status measure for coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. (1995) 25:333–41. 10.1016/0735-1097(94)00397-9

28.

Rabin R de Charro F . EQ-5D: a measure of health status from the EuroQol Group. Ann Med. (2001) 33:337–43. 10.3109/07853890109002087

29.

Tsuchiya A Ikeda S Ikegami N Nishimura S Sakai I Fukuda T et al . Estimating an EQ-5D population value set: the case of Japan. Health Econ. (2002) 11:341–53. 10.1002/hec.673

30.

Anavekar NS McMurray JJ Velazquez EJ Solomon SD Kober L Rouleau JL et al . Relation between renal dysfunction and cardiovascular outcomes after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. (2004) 351:1285–95. 10.1056/NEJMoa041365

31.

Noels H Lehrke M Vanholder R Jankowski J . Lipoproteins and fatty acids in chronic kidney disease: molecular and metabolic alterations. Nat Rev Nephrol. (2021) 17:528–42. 10.1038/s41581-021-00423-5

32.

Werner GS . The role of coronary collaterals in chronic total occlusions. Curr Cardiol Rev. (2014) 10:57–64. 10.2174/1573403X10666140311123814

33.

Tajti P Karatasakis A Danek BA Alaswad K Karmpaliotis D Jaffer FA et al . In-hospital outcomes of chronic total occlusion percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with chronic kidney disease. J Invasive Cardiol. (2018) 30:E113–21.

34.

Wöhrle J Seeger J Lahu S Mayer K Bernlochner I Gewalt S et al . Ticagrelor or prasugrel in patients with acute coronary syndrome in relation to estimated glomerular filtration rate. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. (2021) 14:1857–66. 10.1016/j.jcin.2021.06.028

35.

Sohal AS Gangji AS Crowther MA Treleaven D . Uremic bleeding: pathophysiology and clinical risk factors. Thromb Res. (2006) 118:417–22. 10.1016/j.thromres.2005.03.032

36.

Wieloch M Jönsson KM Själander A Lip GY Eriksson N Svensson PJ . Estimated glomerular filtration rate is associated with major bleeding complications but not thromboembolic events, in anticoagulated patients taking warfarin. Thromb Res. (2013) 131:481–6. 10.1016/j.thromres.2013.01.006

37.

Cho JY Lee SY Yun KH Kim BK Hong SJ Ko JS et al . Factors related to major bleeding after ticagrelor therapy: results from the TICO trial. J Am Heart Assoc. (2021) 10:e019630. 10.1161/JAHA.120.019630

38.

Salisbury AC Sapontis J Grantham JA Qintar M Gosch KL Lombardi W et al . Outcomes of chronic total occlusion percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with diabetes: insights from the OPEN CTO registry. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. (2017) 10:2174–81. 10.1016/j.jcin.2017.08.043

39.

Walsh SJ Hanratty CG McEntegart M Strange JW Rigger J Henriksen PA et al . Intravascular healing is not affected by approaches in contemporary CTO PCI: the CONSISTENT CTO study. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. (2020) 13:1448–57. 10.1016/j.jcin.2020.03.032

40.

Sapontis J Salisbury AC Yeh RW Cohen DJ Hirai T Lombardi W et al . Early procedural and health status outcomes after chronic total occlusion angioplasty: a report from the OPEN-CTO registry (outcomes, patient health status, and efficiency in chronic total occlusion hybrid procedures). JACC Cardiovasc Interv. (2017) 10:1523–34. 10.1016/j.jcin.2017.05.065

41.

Metzger M Abdel-Rahman EM Boykin H Song MK . A narrative review of management strategies for common symptoms in advanced CKD. Kidney Int Rep. (2021) 6:894–904. 10.1016/j.ekir.2021.01.038

42.

Al-Taie N Maftei D Kautzky-Willer A Krebs M Stingl H . Assessing the quality of life among patients with diabetes in Austria and the correlation between glycemic control and the quality of life. Prim Care Diabetes. (2020) 14:133–8. 10.1016/j.pcd.2019.11.003

43.

Graziani F Tsakos G . Patient-based outcomes and quality of life. Periodontol. (2000) (2020) 83:277–94. 10.1111/prd.12305

44.

Werner GS Martin-Yuste V Hildick-Smith D Boudou N Sianos G Gelev V et al . A randomized multicentre trial to compare revascularization with optimal medical therapy for the treatment of chronic total coronary occlusions. Eur Heart J. (2018) 39:2484–93. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy220

45.

Wyld M Morton RL Hayen A Howard K Webster AC . A systematic review and meta-analysis of utility-based quality of life in chronic kidney disease treatments. PLoS Med. (2012) 9:e1001307. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001307

Summary

Keywords

chronic total occlusion, percutaneous coronary intervention, low estimated glomerular filtration rate, symptom, quality of life

Citation

Zhao S, Chen Y, Zhu B, Wang J, Wei Z, Zou Y, Hu W, Chen G, Wang H, Xia C, Yu T, Han P, Yang L, Wang W, Zhai Z, Gao H, Li C and Lian K (2022) Percutaneous coronary intervention improves quality of life of patients with chronic total occlusion and low estimated glomerular filtration rate. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 9:1019688. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2022.1019688

Received

15 August 2022

Accepted

28 November 2022

Published

21 December 2022

Volume

9 - 2022

Edited by

Krishnaraj Sinhji Rathod, Queen Mary University of London, United Kingdom

Reviewed by

Lei Guo, Dalian Medical University, China; Yao-Jun Zhang, Xuzhou Medical University, China; Mattia Lunardi, Integrated University Hospital Verona, Italy

Updates

Copyright

© 2022 Zhao, Chen, Zhu, Wang, Wei, Zou, Hu, Chen, Wang, Xia, Yu, Han, Yang, Wang, Zhai, Gao, Li and Lian.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Kun Lian michealo@qq.com; liank1122@163.comChengxiang Li lichx1@163.comHaokao Gao hk_gao@163.com

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

This article was submitted to Coronary Artery Disease, a section of the journal Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.