Abstract

Background:

Few studies have explored the use of machine learning models to predict the recurrence of atrial fibrillation (AF) in patients who have undergone cryoballoon ablation (CBA). We aimed to explore the risk factors for the recurrence of AF after CBA in order to construct a nomogram that could predict this risk.

Methods:

Data of 498 patients who had undergone CBA at Ruijin Hospital, Shanghai Jiaotong University School of Medicine, were retrospectively collected. Factors such as clinical characteristics and biophysical parameters during the CBA procedure were collected for the selection of variables. Scores for all the biophysical factors—such as time to pulmonary vein isolation (TTI) and balloon temperature—were calculated to enable construction of the model, which was then calibrated and compared with the risk scores.

Results:

A 36-month follow-up showed that 177 (35.5%) of the 489 patients experienced AF recurrence. The left atrial volume, TTI, nadir cryoballoon temperature, and number of unsuccessful freezes were related to the recurrence of AF (P < .05). The area under the curve (AUC) of the nomogram's time-dependent receiver operating characteristic curve was 77.6%, 71.6%, and 71.0%, respectively, for the 1-, 2-, and 3-year prediction of recurrence in the training cohort and 77.4%, 74.7%, and 68.7%, respectively, for the same characteristics in the validation cohort. Calibration and data on the nomogram's clinical effectiveness showed it to be accurate for the prediction of recurrence in both the training and validation cohorts as compared with established risk scores.

Conclusion:

Biophysical parameters such as TTI and cryoballoon temperature have a great impact on AF recurrence. The predictive accuracy for recurrence of our nomogram was superior to that of conventional risk scores.

Introduction

Pulmonary vein isolation (PVI) is the cornerstone of efforts to ablate atrial fibrillation (AF). Cryoballoon ablation (CBA), designed especially for PVI, is now established as a standard treatment for symptomatic drug-resistant AF. However, there remain some 30% of patients for whom this procedure is ineffective (1). Many scores based on clinical characteristics have been created in efforts to assess the risk of AF recurrence, but their predictive accuracy is limited and variables in some scores are difficult to obtain (2, 3). Biophysical parameters during CBA—such as time to PVI (TTI), balloon temperature, and number of unsuccessful freezes—have been identified as associated with the durability of PVI (4). Accordingly, we speculated that those biophysical parameters were related to the recurrence of AF after CBA and that a predictive model based on them could be more useful than dependence on conventional risk scores.

We therefore aimed to (1) prove that biophysical parameters during CBA could be used as variables in the prediction of AF recurrence, and (2) develop and validate a nomogram for the prediction of recurrence after CBA.

Methods

Study population

We recruited 498 consecutive AF patients who had undergone CBA between January 2017 and July 2019 at Ruijin Hospital, Shanghai Jiaotong University School of Medicine. Preoperative cardiac ultrasound and computed tomography angiography (CTA) of left atrium (LA) were performed. The inclusion criteria specified that these patients had to be between the 18 and 80 years of age and experiencing symptoms of AF, in whom PVI by CBA was well indicated and successful PVI was considered as the main endpoint of the procedure, and that they had to have failed or refused a prescription of at least one antiarrhythmic drug (AAD). The exclusion criteria included the following: (1) prior LA ablation, (2) a LA diameter greater than 50 mm, (3) experience of a myocardial infarction with the prior 3 months, (4) a stroke or transient ischemic attack within the prior 6 months, (5) valvular AF, and (6) inability or refusal to accept postinterventional oral anticoagulation (OAC).

Ablation procedure

Before ablation, AADs with the exception of amiodarone were discontinued for at least 5 half-lives; amiodarone was discontinued for at least 14 days. OAC was continued. Transesophageal echocardiography was required within 3 days of the procedure to assess for a left atrial thrombus. During the procedure, patients were under conscious anesthesia and monitored for their vital signs. Heparin was administered intravenously with a bolus and the activated clotting time (ACT) was monitored and maintained for more than 300 s. A decapolar catheter was placed in the coronary sinus, with a duopolar catheter in the right ventricular apex for backup pacing. The LA was accessed with a steerable sheath (FlexCath Advance, Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN, USA), through which the CB (Arctic Front Advance, Medtronic) and circular catheter (Achieve 20 mm, Medtronic) were placed in the LA. Attempts were made to record the pulmonary venous potential (PVP) in each PV. We performed a TTI-based ablation protocol. The dosing of CBA was as follows:

- 1.

If the PVP was recorded and the TTI was less than 60 s, the duration of CBA was between TTI + 90 s and TTI + 120 s at the operator's discretion, and a bonus CBA of 120 s was applied.

- 2.

If the TTI was between 60 s and 90 s, the duration of CBA was 180 s and a bonus CBA of 120 s was applied.

- 3.

If PVI was not achieved within 90 s, CBA was abandoned and the balloon was repositioned for a subsequent CBA.

- 4.

If the PVP was not recorded during CBA, an empiric CBA was delivered for 120 s. If PVI was achieved after this CBA, a bonus of between 160 s and 180 s was applied; if not, the balloon was repositioned for a subsequent CBA.

During the bonus application (point 4), the operators were encouraged to change the balloon's position and orientation by placing the Achieve catheter in a different PV branch. If the nadir temperature of the balloon was equal to or less than −55°C and the duration of ablation was less than 120 s, the CBA was stopped in advance and the balloon repositioned for a subsequent CBA. If the nadir temperature was equal to or less than −55°C and the duration of ablation was already above 120 s, CBA was ceased in advance and no additional CBA was given. During the CBA of right-sided PVs, phrenic movement was monitored by continuous phrenic nerve stimulation with a catheter positioned in the superior vena cava. Complete PVI was considered a bidirectional conduction block between LA and PV. Cardioversion was applied when the heart rhythm was still AF following completion of CBA.

Data collection

The data were collected for analysis including: (1) Basic demographics; (2) Imaging result of LA diameter was derived from echocardiography by measuring the anteroposterior diameter of LA from the parasternal transverse axis. Left ventricular ejection fraction was measured by Simpson's biplane method. LA Volume (LAV) was derived from CTA. The original scanned images were processed by the in-built software of the CT for the construction of the three-dimension model of the LA and PVs. PVs were removed from the three-dimension model and the LAV was calculated automatically. (3) peri-procedural characteristics such as recording of PVP, TTI, balloon temperature during cryoablation.

Follow-up

All patients were hospitalized with rhythm monitored by telemetry for 3 continuous days after CBA. Patients were followed up with 24-h Holter electrocardiogram every 3 months over the first year and every 6 months thereafter. OAC was continued for at least 8 weeks and prescription of AADs was allowed during the blanking period at the discretion of the clinical cardiologist. AF recurrence was defined as atrial arrhythmia persisting more than 30 s—including AF, atrial flutter, or atrial tachycardia—beyond a 90-day blanking period (the period during which recurrence is considered clinically insignificant). In patients with symptoms suggestive of PV stenosis or in those undergoing a CBA procedure, CT of the LA and PV was performed to exclude PV stenosis.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 24.0 (IBM Inc., Chicago, IL, USA), X-tile 3.6.1, and R (version 4.0.2; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) software. Continuous data are presented as means with standard deviation, and categorical variables are given as numbers and percentages. Student's t-test and the chi-square test were used to compare clinical characteristics and variables as appropriate. Survival free from atrial arrhythmia was estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method and compared by log-rank tests. Cox proportional hazards models were used to derive hazard ratios and the corresponding confidence intervals.

All 498 patients were randomly divided into a training cohort and a validation cohort (7:3) based on complete data. The training cohort was used to develop the model, and the validation cohort was applied to validate the model. We used a forward + backward stepwise elimination approach to identify predictive variables for the model. Least absolute shrinkage and selection operator regression was also applied in the predictor's selection to examine the importance of predictive variables selected by stepwise regression analysis. Based on the selected predictive variables, the Cox regression model was developed and presented as the nomogram. We assessed the predictive accuracy of the nomogram after discrimination and calibration. To quantify the discrimination performance of the nomogram, Harrell's C-index was measured. Calibration curves, accompanied by the Hosmer-Lemeshow test, were plotted to assess the nomogram's calibration. To assess the nomogram's performance, the Cox regression formula developed in the training cohort was then applied in the validation cohort and predicted survival was calculated.

We analyzed the following risk scores specifically developed for the prediction of AF recurrence post-CBA: CHA2DS2-VASc, SCALE-CryoAF, MB-LATER, CAAP-AF, and BASE-AF2. DeLong's test was used to compare the C-index of the nomogram and the scores in the training and validation cohorts. Time-dependent receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was evaluated and the area under curve (AUC) was calculated for the discriminative power of the nomogram and the scores. In addition, we performed a decision curve analysis of the monogram and the two scores.

All P values were two-sided, with P < . 05 indicating statistical significance. C-index, calibration curve, nomogram, and bootstrapping validation were calculated or formulated using the rms and risk regression packages in R.

Results

Patients' baseline demographics

As shown in Table 1, the mean age of our 498 patients was 59.9 years; 63.9% were male, 36.1% were female, and 29.5% of the total had persistent AF. We analyzed the clinical baseline characteristics of patients with and without recurrence and found that there was no difference in terms of age, gender, AF diagnosis time, or AF-related comorbidities. Compared with patients without recurrence, patients with recurrence had a higher percentage of persistent AF, larger LA, and higher clinical score.

Table 1

| All patients (n = 498) | No recurrences (n = 321) | Recurrences (n= 177) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | 59.9 ± 10.3 | 59.8 ± 10.5 | 60.1 ± 10.0 | 0.769 |

| Sex (Male) | 63.9% | 66.7% | 58.8% | 0.079 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 24.6 ± 3.0 | 24.6 ± 3.1 | 24.7 ± 2.8 | 0.594 |

| Months since first AF diagnosis | 37.9 ± 36.0 | 35.7 ± 34.7 | 41.7 ± 38.1 | 0.076 |

| Persistent AF | 29.5% | 22.7% | 41.8% | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 54.6% | 52.6% | 58.2% | 0.234 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 10.6% | 11.8% | 8.5% | 0.244 |

| Coronary artery disease | 10.6% | 11.2% | 9.6% | 0.577 |

| Heart failure | 0.6% | 0.6% | 0.6% | 0.936 |

| Previous Stroke/TIA | 1.2% | 1.6% | 0.6% | 0.331 |

| Left atrial diameter | 40.2 ± 4.0 | 39.8 ± 3.7 | 41.1 ± 4.5 | <0.001 |

| LVEF | 65.9 ± 5.3 | 66.0 ± 5.3 | 65.6 ± 5.2 | 0.407 |

| Left atrial volume | 115.4 ± 38.9 | 110.4 ± 31.9 | 124.3 ± 47.9 | <0.001 |

| CHA2DS2VASc score | 1.7 ± 1.4 | 1.7 ± 1.4 | 1.7 ± 1.3 | 0.781 |

| BASE-AF2 | 1.3 ± 1.1 | 1.1 ± 1.0 | 1.7 ± 1.0 | <0.001 |

| SCALE-CryoAF | 2.1 ± 2.4 | 1.5 ± 1.9 | 3.3 ± 2.6 | <0.001 |

| CAAP-AF | 3.9 ± 1.5 | 3.7 ± 1.5 | 4.2 ± 1.5 | <0.001 |

| MBLATER | 1.2 ± 0.9 | 0.9 ± 0.7 | 1.5 ± 1.0 | <0.001 |

Baseline clinical characteristics.

AF, Atrial fibrillation; TIA, transient ischemic attack; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction.

Stratification of patients according to procedural and biophysical characteristics

Compared with patients without long-term recurrence, patients with long-term recurrence had longer procedural and LA dwell times as well as higher fluoroscopic doses. In patients without recurrence, PVP was more frequently recorded; average TTI was shorter, and there were fewer unsuccessful freezes. Regarding each PV, it was noticed that the balloon temperature at 30 s during successful CBA (Temp30), the balloon temperature at 60 s (Temp60), and the nadir balloon temperature (Tempnadir) were significantly lower and TTI was significantly shorter in patients without recurrence. Details of the biophysical characteristics are shown in Table 2.

Table 2

| All patients (n = 498) | No recurrences (n = 321) | Recurrences (n = 177) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Procedure duration (min) | 85.3 ± 33.2 | 81.2 ± 29.2 | 92.6 ± 38.4 | 0.001 |

| LA dwell time (min) | 61.0 ± 29.7 | 58.2 ± 26.8 | 66.1 ± 33.8 | 0.005 |

| Fluoroscopy time (min) | 13.3 ± 6.0 | 12.3 ± 5.3 | 15.1 ± 6.7 | <0.001 |

| Radiation dose (mGray) | 286.4 ± 192.1 | 270.4 ± 185.1 | 315.3 ± 201.4 | 0.014 |

| Number of PV with real-time recording of PV electrogram | 2.5 ± 1.2 | 2.7 ± 1.1 | 2.1 ± 1.2 | <0.001 |

| Average TTI | 38.4 ± 10.4 | 36.7 ± 9.6 | 41.7 ± 11.1 | <0.001 |

| Total number of freezes | 10.0 ± 2.7 | 9.9 ± 2.5 | 10.2 ± 3.0 | 0.283 |

| Total number of unsuccessful freezes | 2.4 ± 2.4 | 2.1 ± 2.4 | 2.8 ± 2.5 | 0.007 |

| LSPV | ||||

| Total number of freezes | 2.9 ± 1.4 | 2.7 ± 1.3 | 3.2 ± 1.6 | <0.001 |

| Number of unsuccessful freezes | 0.9 ± 1.3 | 0.7 ± 1.2 | 1.2 ± 1.5 | <0.001 |

| Total duration of freezes | 399 ± 163.2 | 379.2 ± 145.4 | 435.3 ± 186.7 | <0.001 |

| Average duration of freezes | 142.7 ± 18.5 | 144.9 ± 18.3 | 138.8 ± 18.2 | 0.001 |

| Temp30 (°C) | −29.9 ± 4.4 | −30.3 ± 4.2 | −29.3 ± 4.6 | 0.010 |

| Temp60 (°C) | −40.4 ± 4.8 | −40.9 ± 4.5 | −39.4 ± 5.1 | 0.001 |

| Tempnadir (°C) | −47.1 ± 5.0 | −47.5 ± 4.9 | −46.4 ± 5.0 | 0.020 |

| Real-time recording of PV electrogram | 78.7% | 84.7% | 67.8% | <0.001 |

| TTI | 42.5 ± 16 | 41.7 ± 16.1 | 44.5 ± 15.7 | 0.773 |

| LIPV | ||||

| Total number of freezes | 2.3 ± 0.9 | 2.3 ± 0.9 | 2.1 ± 0.8 | 0.005 |

| Number of unsuccessful freezes | 0.4 ± 0.7 | 0.4 ± 0.8 | 0.3 ± 0.6 | 0.256 |

| Total duration of freezes | 339.1 ± 118 | 351.4 ± 113.1 | 316.6 ± 123.6 | 0.002 |

| Average duration of freezes | 152.2 ± 18.1 | 153.0 ± 17.3 | 150.7 ± 19.5 | 0.180 |

| Temp30 (°C) | −28.7 ± 3.9 | −29.3 ± 3.7 | −27.5 ± 3.8 | <0.001 |

| Temp60 (°C) | −37.7 ± 4.2 | −38.5 ± 4.0 | −36.2 ± 4.2 | <0.001 |

| Tempnadir (°C) | −43.2 ± 4.7 | −43.9 ± 4.5 | −41.8 ± 4.7 | <0.001 |

| Real-time recording of PV electrogram | 66.3% | 72.3% | 53.4% | 0.001 |

| TTI | 35.8 ± 15.3 | 33.5 ± 14.6 | 41.3 ± 15.6 | <0.001 |

| RSPV | ||||

| Total number of freezes | 2.5 ± 1.0 | 2.5 ± 1.0 | 2.5 ± 1.1 | 0.963 |

| Number of unsuccessful freezes | 0.5 ± 1.0 | 0.5 ± 1.0 | 0.6 ± 0.9 | 0.294 |

| Total duration of freezes | 327.1 ± 124.1 | 327.4 ± 121.5 | 326.5 ± 129.2 | 0.937 |

| Average duration of freezes | 136.6 ± 19.8 | 136.3 ± 18.9 | 137.2 ± 21.4 | 0.625 |

| Temp30 (°C) | −31.8 ± 4.6 | −32.6 ± 4.5 | −30.2 ± 4.5 | <0.001 |

| Temp60 (°C) | −42.2 ± 5.2 | −43.2 ± 4.9 | −40.3 ± 5.3 | <0.001 |

| Tempnadir (°C) | −49.5 ± 5.7 | −50.7 ± 5.0 | −47.2 ± 6.3 | <0.001 |

| Real-time recording of PV electrogram | 61.7% | 69.8% | 46.9% | <0.001 |

| TTI | 33.8 ± 15 | 32.0 ± 13.8 | 38.7 ± 16.8 | <0.001 |

| RIPV | ||||

| Total number of freezes | 2.4 ± 1.2 | 2.4 ± 1.1 | 2.4 ± 1.3 | 0.925 |

| Number of unsuccessful freezes | 0.5 ± 1.1 | 0.5 ± 1.0 | 0.6 ± 1.1 | 0.246 |

| Total duration of freezes | 333.6 ± 144.1 | 332.9 ± 131.6 | 334.8 ± 164.8 | 0.891 |

| Average duration of freezes | 143.0 ± 22.1 | 143.0 ± 22.7 | 142.9 ± 20.9 | 0.977 |

| Temp30 (°C) | −30.2 ± 4.9 | −31.0 ± 4.9 | −28.9 ± 4.6 | <0.001 |

| Temp60 (°C) | −39.8 ± 5.2 | −40.7 ± 5.2 | −38.3 ± 4.9 | <0.001 |

| Tempnadir (°C) | −46.3 ± 6.3 | −47.3 ± 6.2 | −44.5 ± 6.1 | <0.001 |

| Real-time recording of PV electrogram | 52.8% | 59.2% | 41.2% | <0.001 |

| TTI | 38.9 ± 15.1 | 37.7 ± 15.4 | 42.1 ± 13.9 | 0.032 |

Procedure-related biophysical characteristics and data.

LSPV, left superior pulmonary vein; LIPV, left inferior pulmonary vein; RSPV, right superior pulmonary vein; RIPV, right inferior pulmonary vein; TTI, time to pulmonary vein isolation; Temp30, Temperature of CB at 30 s; Temp60, Temperature of CB at 60 s; Tempnadir, nadir temperature of CB.

Stratification of the balloon temperature and TTI of each PV was performed by X-tile and the optimal cutoff values were determined (Table 3). Scores corresponding to Temp30, Temp60, Tempnadir, and TTI were calculated by counting the number of PVs achieving the cutoff value; these ranged from 0 to 4. Number of PVs with real-time recording of PVP and number of unsuccessful freezes were counted and analyzed. The results are shown in Table 4.

Table 3

| Cutoff value | X 2 | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| LSPV | |||

| TTI | 48 s | 9.872 | 0.039 |

| Temp30 | −26°C | 6.957 | 0.138 |

| Temp60 | −36°C | 14.470 | 0.005 |

| Tempnadir | −47°C | 9.872 | 0.039 |

| LIPV | |||

| TTI | 40 s | 30.517 | <0.001 |

| Temp30 | −27°C | 38.682 | <0.001 |

| Temp60 | −36°C | 38.063 | <0.001 |

| Tempnadir | −40°C | 32.291 | <0.001 |

| RSPV | |||

| TTI | 40 s | 17.379 | 0.001 |

| Temp30 | −31°C | 23.333 | <0.001 |

| Temp60 | −42°C | 33.126 | <0.001 |

| Tempnadir | −47°C | 50.187 | <0.001 |

| RIPV | |||

| TTI | 39 s | 12.664 | 0.011 |

| Temp30 | −28°C | 19.176 | 0.001 |

| Temp60 | −37°C | 24.695 | <0.001 |

| Tempnadir | −43°C | 25.483 | <0.001 |

Cutoff value of balloon temperature and TTI of each PV.

Table 4

| All patients (n = 498) | No Recurrences (n = 321) | Recurrences (n = 177) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of PVs with real-time recording of PV potential | ||||

| 0 | 21 (4.2%) | 4 (1.2%) | 17 (9.6%) | <0.001 |

| 1 | 69 (13.9%) | 31 (9.7%) | 38 (21.5%) | |

| 2 | 131 (26.3%) | 73 (22.7%) | 58 (32.8%) | |

| 3 | 147 (29.5%) | 111 (34.6%) | 36 (20.3%) | |

| 4 | 130 (26.1%) | 102 (31.8%) | 28 (15.8%) | |

| TTI score | ||||

| 0 | 80 (16.1%) | 16 (5%) | 64 (36.2%) | <0.001 |

| 1 | 143 (28.7%) | 82 (25.5%) | 61 (34.5%) | |

| 2 | 129 (25.9%) | 99 (30.8%) | 30 (16.9%) | |

| 3 | 103 (20.7%) | 85 (26.5%) | 18 (10.2%) | |

| 4 | 43 (8.6%) | 39 (12.1%) | 4 (2.3%) | |

| Score of Temp30 | ||||

| 0 | 28 (5.6%) | 8 (2.5%) | 20 (11.3%) | <0.001 |

| 1 | 66 (13.3%) | 31 (9.7%) | 35 (19.8%) | |

| 2 | 104 (20.9%) | 57 (17.8%) | 47 (26.6%) | |

| 3 | 151 (30.3%) | 105 (32.7%) | 46 (26%) | |

| 4 | 149 (29.9%) | 120 (37.4%) | 29 (16.4%) | |

| Score of Temp60 | ||||

| 0 | 23 (4.6%) | 4 (1.2%) | 19 (10.7%) | <0.001 |

| 1 | 69 (13.9%) | 30 (9.3%) | 39 (22%) | |

| 2 | 111 (22.3%) | 59 (18.4%) | 52 (29.4%) | |

| 3 | 149 (29.9%) | 110 (34.3%) | 39 (22%) | |

| 4 | 146 (29.3%) | 118 (36.8%) | 28 (15.8%) | |

| Score of Tempnadir | ||||

| 0 | 36 (7.2%) | 9 (2.8%) | 27 (15.3%) | <0.001 |

| 1 | 59 (11.8%) | 24 (7.5%) | 35 (19.8%) | |

| 2 | 108 (21.7%) | 72 (22.4%) | 36 (20.3%) | |

| 3 | 176 (35.3%) | 120 (37.4%) | 56 (31.6%) | |

| 4 | 119 (23.9%) | 96 (29.9%) | 23 (13%) | |

| Number of unsuccessful freezes | ||||

| 0 | 122 (24.5%) | 89 (27.7%) | 33 (18.6%) | <0.001 |

| 1 | 105 (21.1%) | 75 (23.4%) | 30 (16.9%) | |

| 2 | 90 (18.1%) | 61 (19%) | 29 (16.4%) | |

| ≥3 | 181 (36.3%) | 96 (29.9%) | 85 (48%) | |

Distribution of patients with number of PVs with real-time recording of PV potential, TTI score, balloon temperature scores and number of unsuccessful freezes.

Long-term outcome after cryoballoon ablation and risk stratification by score

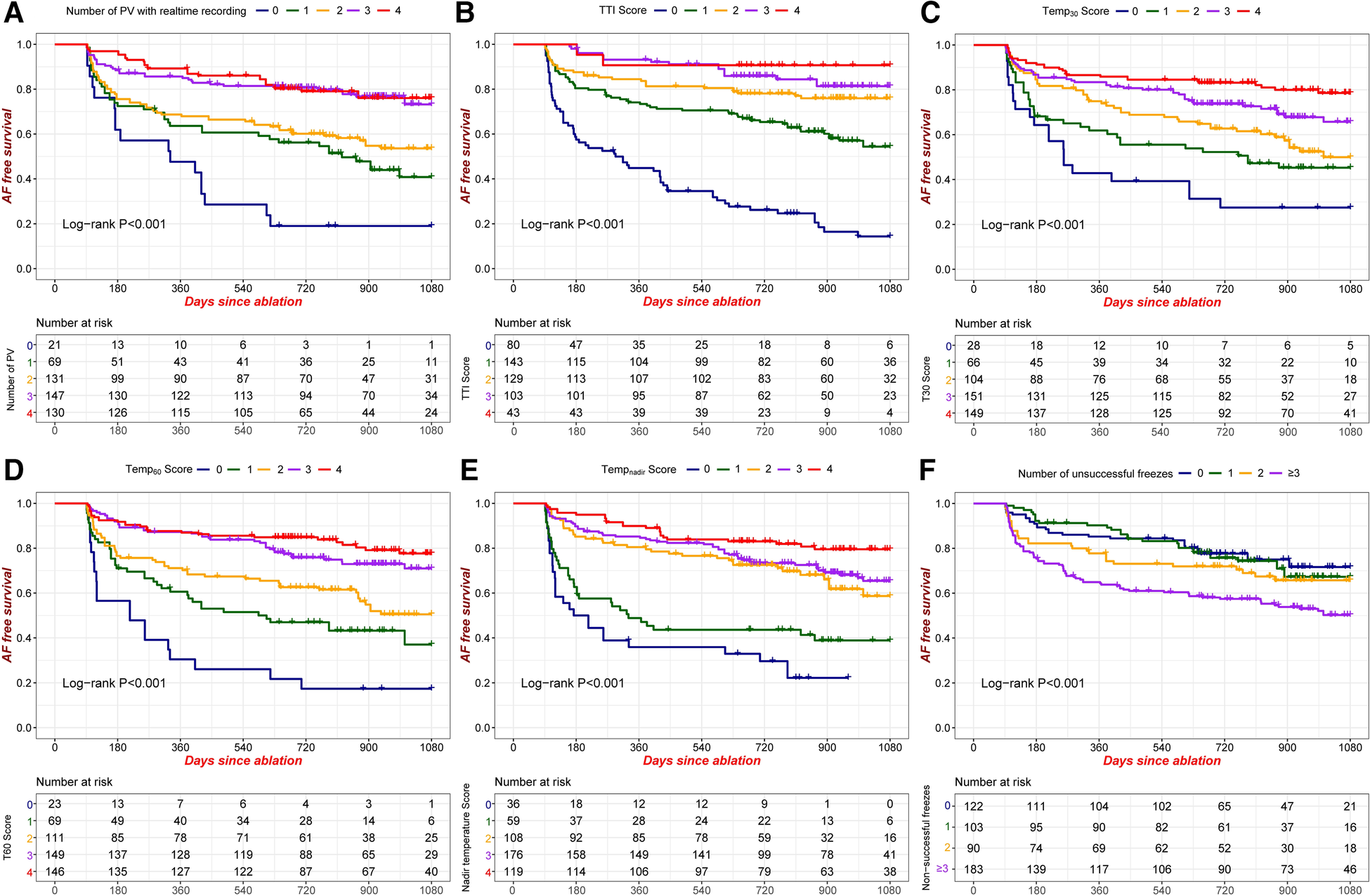

AF recurrence was seen in 177 of the total number of 498 patients. The Kaplan–Meier estimated AF-free survival was 77.4% at 1 year, 68.7% at 2 years, and 60.5% at 3 years. Kaplan–Meier AF-free survival curves with regard to the TTI score, the balloon temperature score (Temp30, Temp60, Tempnadir), the PV number with real-time recording of PVP, and the number of unsuccessful freezes are presented in Figure 1. These variables showed predictive ability for recurrence. Thus, our results support the idea that these factors can be useful for risk stratification and for the prediction of outcome after CBA for AF.

Figure 1

Kaplan-Meier AF-free survival according to different criteria. (A) Number of PVs with real-time recording of PVP; (B) TTI score; (C) Temp30 score; (D) Temp60 score; (E) Tempnadir score; (F) Number of unsuccessful freezes. PVP: pulmonary venous potential; TTI score: number of PVs achieving the cutoff value of TTI; Temp30 score: number of PVs achieving the cutoff value of balloon temperature at 30 s; Temp60 score: number of PVs achieving the cutoff value of balloon temperature at 60 s; Tempnadir score: number of PVs achieving the cutoff value of nadir balloon temperature.

Factor selection and nomogram construction

We randomly allocated 69% (342) of our patients to the training cohort and the remaining 31% (156) to the validation cohort. There were 123 (36.0%) patients in the training cohort and 52 (33.3%) in the validation cohort who experienced recurrence after CBA. There were no significant differences between the training and validation cohorts regarding preoperative baseline and ablation characteristics (Supplementary Table S1).

Stepwise regression analysis and multivariate Cox regression revealed that the LAV, TTI score, Tempnadir score, and number of unsuccessful freezes were identified as significant independent risk factors for AF recurrence (Supplementary Table S2 and Table 5). The nomogram based on these four factors from the training cohort was developed for the prediction of 1-, 2-, and 3-year AF-free survival. The total score, obtained by adding the scores for each of the four factors, was predictive of the 1-, 2-, and 3-year AF-free survival for each individual patient in the training cohort (Figure 2).

Table 5

| Factor | HR | 95%CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| LAV | 1.006 | 1.002–1.010 | 0.006 |

| TTI Score | 0.495 | 0.404–0.605 | <0.001 |

| Tempnadir Score | 0.759 | 0.649–0.888 | <0.001 |

| Number of unsuccessful freezes | 1.298 | 1.108–1.519 | 0.001 |

Cox regression analysis results of recurrence risk factors of atrial fibrillation patients after CB ablation.

HR, hazard ration; CI, confidence interval.

Figure 2

Nomogram derived from the training cohort for the prediction of AF recurrence after cryoballoon ablation.

Validation and calibration of the nomogram

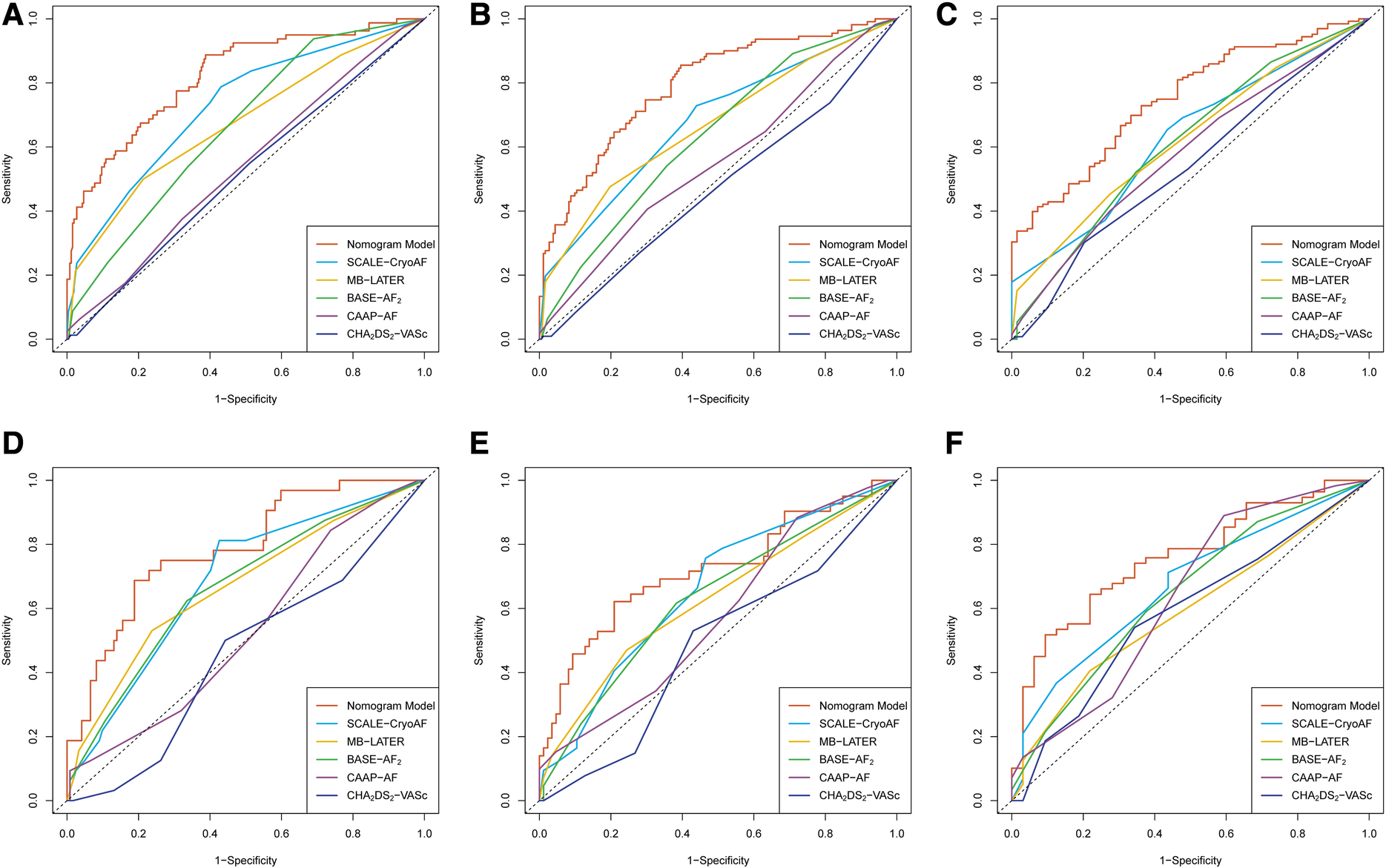

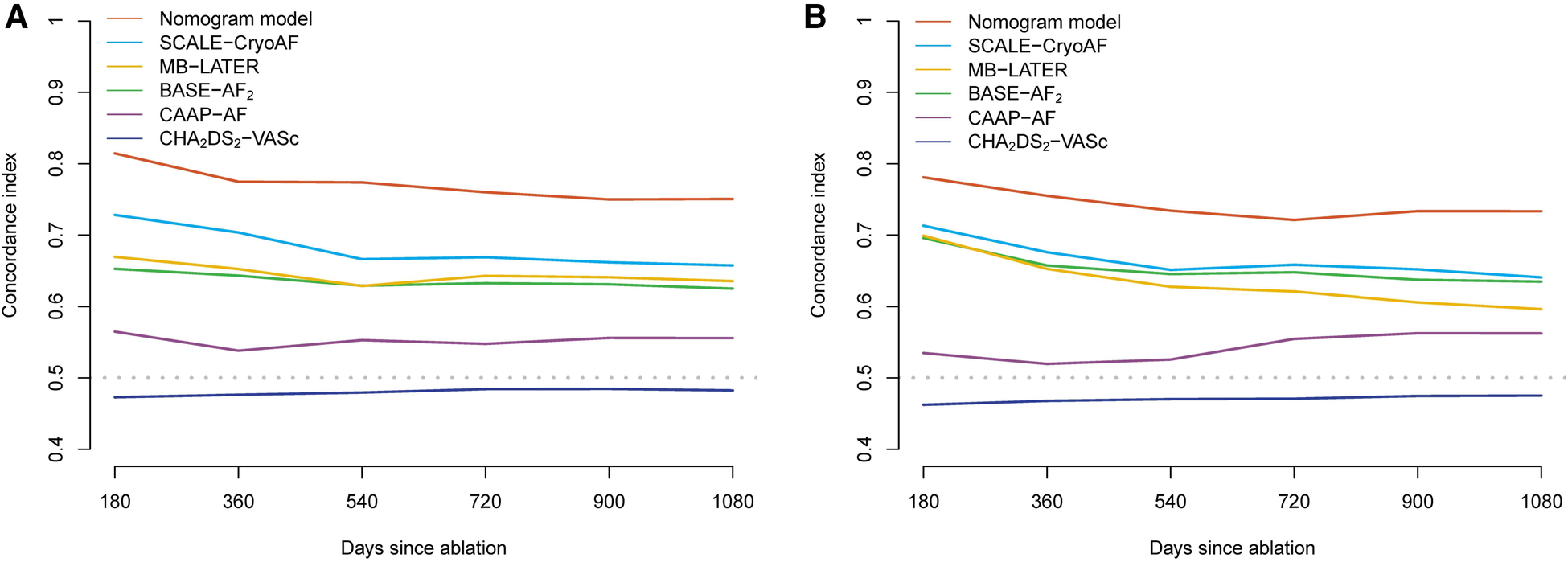

ROC curves were used to evaluate the nomogram's predictive ability for 1-, 2-, and 3-year AF-free survival in both the training and validation cohorts. Our nomogram demonstrated good discriminative ability in both the training cohort (1-year AUC, 82.1%; 2-year AUC, 79.3%; 3-year AUC, 76.2%) and the validation cohort (1-year AUC, 78.6%; 2-year AUC, 71.9%, 3-year AUC, 75.7%) for AF-free survival rates (Figure 3). In comparison with other prediction models based on clinical characteristics, our nomogram demonstrated better accuracy with significance in predicting recurrence in the validation cohort. Although statistical differences between the nomogram models and conventional risk scores were not significant, it was noticed that the AUCs were greater for our nomogram model (Table 6). In addition, the C-index of the nomogram model was greater than the C-index of the conventional risk scores in both the training and validation cohorts (Figure 4).

Figure 3

Receiver operating characteristic curves of the nomogram model and the conventional risk scores in the training cohort for (A) the prediction of 1-year recurrence; (B) prediction of 2-year recurrence; and (C) the prediction of 3-year recurrence. In the validation cohort, (D) the prediction of 1-year recurrence; (E) the prediction of 2-year recurrence; and (F) the prediction of 3-year recurrence.

Table 6

| 1 Year | 2 Year | 3 Year | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUC% (95%CI) | P | AUC% (95%CI) | P | AUC% (95%CI) | P | |

| Training set | ||||||

| Nomogram | 82.1 (76.7–87.5) | – | 79.3 (73.9–84.6) | – | 74.8 (67.9–81.7) | – |

| SCALE-CryoAF | 72.8 (66.6–79.0) | 0.017 | 67.8 (61.6–74.0) | 0.003 | 62.9 (55.0–70.7) | 0.012 |

| MB-LATER | 67.3 (60.7–74.0) | <0.001 | 66.7 (60.6–72.8) | 0.001 | 62.2 (54.6–69.9) | 0.012 |

| BASE-AF2 | 66.4 (60.3–72.5) | <0.001 | 63.4 (57.2–69.6) | <0.001 | 61.3 (53.2–69.4) | 0.009 |

| CAAP-AF | 53.9 (46.9–60.9) | <0.001 | 55.2 (48.5–61.9) | <0.001 | 57.9 (49.9–66.0) | 0.001 |

| CHA2DS2-VASc | 51.6 (44.6–58.7) | <0.001 | 47.0 (40.3–53.7) | <0.001 | 53.9 (45.5–62.2) | <0.001 |

| Validation set | ||||||

| Nomogram | 78.6 (69.9–87.3) | – | 71.9 (61.8–81.9) | – | 75.7 (65.4–86.0) | – |

| SCALE-CryoAF | 68.5 (58.9–78.2) | 0.110 | 65.6 (56.1–75.3) | 0.345 | 66.9 (55.7–78.2) | 0.018 |

| MB-LATER | 66.8 (56.4–77.2) | 0.057 | 62.5 (52.4–72.7) | 0.167 | 59.2 (47.4–70.9) | 0.630 |

| BASE-AF2 | 66.6 (56.3–76.8) | 0.034 | 62.9 (52.9–72.9) | 0.173 | 64.5 (52.8–76.3) | 0.111 |

| CAAP-AF | 52.9 (42.3–63.6) | <0.001 | 57.5 (47.2–67.7) | 0.035 | 63.7 (51.3–76.2) | 0.098 |

| CHA2DS2-VASc | 45.7 (35.1–56.3) | <0.001 | 48.3 (37.9–58.7) | 0.001 | 58.6 (46.2–71.1) | 0.040 |

Results of AUCs of time dependent ROC curves in training and validation cohorts.

AUC, area under curve; ROC, receiver operating characteristic; CI, confidence interval.

Figure 4

C-index of the nomogram model and conventional risk scores in training cohort (A) and the validation cohort (B).

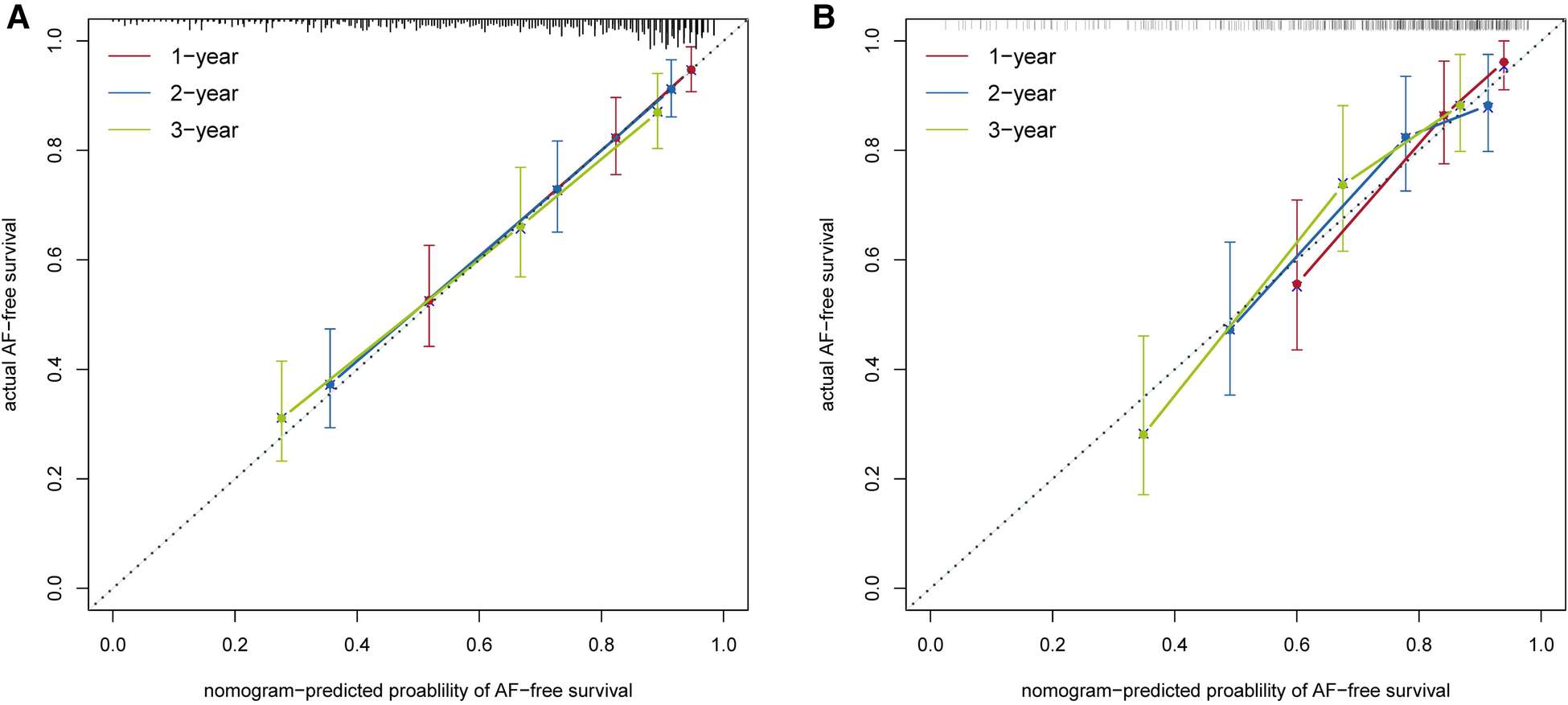

The nomogram had acceptable calibration in the training cohort (Hosmer-Lemeshow statistics: 1 year, χ2 = 10.278, P = . 246; 2 years, χ2 = 5.209, P = . 735; 3 years, χ2 = 3.924, P = . 864) and the validation cohort (Hosmer-Lemeshow statistic: 1 year, χ2 = 14.552, P = . 068; 2 years, χ2 = 6.378, P = . 605; 3 years, χ2 = 7.889, P = . 444). The calibration plots of our nomogram also showed optimal agreement between the actual observations and the predicted outcomes both in the training cohort and the validation cohort (Figure 5) for all time points. Thus these nomogram-based results display good accuracy for predicting 1-, 2-, and 3-year AF-free survival after CBA.

Figure 5

Calibration curves of the nomogram model in the training cohort (A) and in the validation cohort (B).

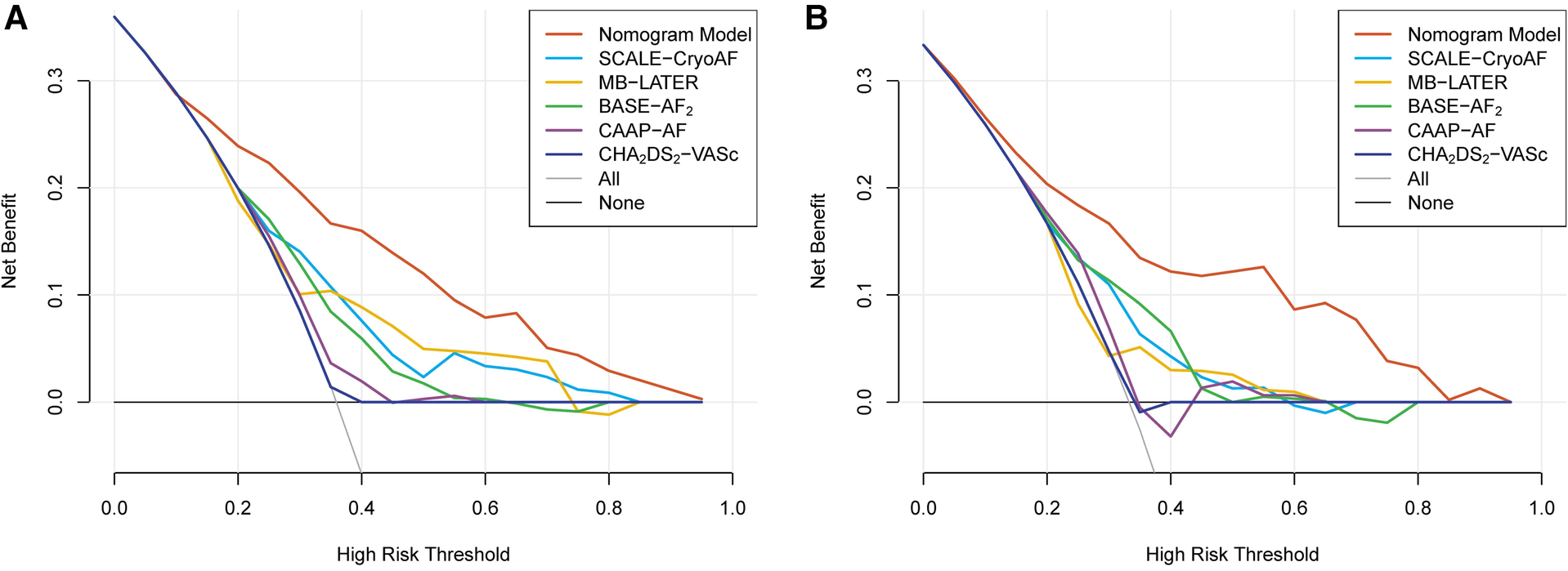

Compared with the other prediction models, the results of the decision curve analyses (DCAs) demonstrate that the nomogram model has good clinical effectiveness in both the training and validation cohorts (Figure 6). All the results indicate that the accuracy, discriminative ability, and clinical effectiveness of the nomogram model are superior to those of the other conventional risk scores.

Figure 6

The results of decision curves analysis (DCA) of the nomogram model and the conventional risk scores in the training cohort (A) and in the validation cohort (B).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first nomogram developed for the prediction of AF recurrence using both clinical characteristics and procedural biophysical parameters during CBA. The nomogram performed well in both the training and validation cohorts. The model contains only four variables (LAV, TTI score, Tempnadir score, and number of unsuccessful freezes), all of which are available and easy to use in clinical practice. In comparison with other conventional risk scores, our nomogram showed better predictive ability and good potential implication in clinical practice.

Factors related to recurrence after cryoballoon ablation

We discovered that LAV, TTI, Tempnadir, and number of unsuccessful freezes were associated with AF recurrence. It is certain that LAV was highly associated with the success of CBA. Patients with an enlarged LA—which contains more extra-PV triggers and arrhythmogenic substrate than a normal LA (owing to electrical remodeling, structural remodeling, and interstitial fibrosis)—are at greater risk for the recurrence of atrial arrythmia after an initial CBA (5, 6). The type of AF was unexpectedly not included in the related factors, for which we speculate that LAV is quantitative and more representative of persistency of AF and severity of LA remodeling, which is greatly associated with the efficacy outcome of cryoballoon ablation. However, the number of unsuccessful freezes also reflects the development of AF from a different angle. The increased number of unsuccessful freezes may derive from anatomic variation, dilation of the PV ostium, and enlargement of the LA, which have already been proven to raise the risk of AF recurrence after CBA (7, 8).

It is well established that PVI is the cornerstone of AF ablation. Since CBA was designed for the convenience of PVI, the procedural biophysical parameter is considered an important indicator of sufficient ablation. Several studies have already reported that a longer TTI is associated with early reconnection of the PV and a higher risk of recurrence after CBA (4, 9, 10). Therefore, TTI has emerged as an important marker for the dosing of CBA. Several studies that have designed a CBA dosing protocol based on TTI achieved a noninferior efficacy outcome compared with conventional protocols or radiofrequency ablation (11–13). However, the cutoff value of TTI was the same for the four PVs in those studies despite the different anatomic characteristics of each PV. As shown in Table 2, the average values of TTI differed among the four PVs. In our study, therefore, we analyzed the four PVs separately and explored the best cutoff value for each. By calculating and aggregating the score of each PV, the TTI score better reflected the durability of PVI and is believed to be more accurate and reliable for the prediction of AF recurrence.

Balloon temperature during CBA affects the occlusion of the treated PV. Lower balloon temperature reflects better balloon-tissue contact. Thus, the balloon temperature is known to be an important indicator of CBA efficiency. Fürnkranz reported that the nadir temperature is predictive of the acute outcome of PVI and helpful in identifying early PV reconnection (14). In addition, several studies have identified the role of balloon temperature in predicting long-term durable PVI (15, 16). The optimal balloon temperature during CBA remains unclear, but there a prospective study using CBA guided by balloon temperature has already demonstrated that cryoapplication with a balloon temperature lower than −30°C within 40 s showed good acute outcomes of PVI and comparable clinical efficacy and safety profiles (17). Accordingly, it is well recognized that balloon temperature is an important indicator of durable PVI as well as procedural success. In addition, the optimal criteria for nadir temperature of each PV differed among the four PVs (18). Therefore we determined the optimal cutoff of TTI and balloon temperature for the four PVs. This is believed to represent the biophysical characteristics of CBA efficiency. In our nomogram model, we included the balloon temperature and calculated the Tempnadir score. The result of our study also emphasizes the importance of monitoring balloon temperature during CBA.

Advantages of the nomogram model

The monogram model was superior to the general score (CHA2DS2-VASc) and specific scores (SCALE-CryoAF, MB-LATER, CAAP-AF, and BASE-AF2) in predicting and discriminating recurrence. These scores were basically calculated using clinical factors such as age, type of AF, duration of AF in the past, history of coronary heart disease, left ventricular ejection fraction, LA diameter, and other factors. However, the biophysical parameters of CBA were not included in those scores, although it has been reported that these biophysical parameters are associated with acute outcome of PVI (4). Our study shows that the C-index of our nomogram model was larger in either the training cohort or the validation cohort than that of other prediction models. In addition, this supported the fact that high quality of PVI was equally crucial for the outcome as clinical factors. In recently published studies, radiofrequency ablation using AI technology yield higher PVI durability and better efficacy outcome (19, 20). Although those studies were performed in radiofrequency ablation, it is undoubtable that durable PVI after CBA was similarly associated with a favorable efficacy outcome.

Furthermore, our monogram model balanced the contribution of each factor to CBA outcome. In conventional risk scores, the coefficient of each risk factor usually comprised an integer. In our nomogram model, however, the coefficients were calculated based on the significance of the risk factor. Therefore, it is reasonable that the monogram model had an advantage over conventional risk scores. In addition, our model uses only four factors, which are available and easy to calculate during procedure. In specific patients with high scores, the electrophysiologist performing CBA should pay more attention to non-PV triggers or the arrhythmogenic substrate and acute PV reconnection. It may also be necessary to extend the ablation range and verify PVI durability. In summary, our nomogram model combines both clinical factors and biophysical parameters, which raises its predictive performance compared with conventional risk scores and implies its clinical significance for the guidance of CBA.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. First, this was a retrospective analysis in which selection bias may have existed; therefore, a future prospective study is warranted. Second, the patients' data were obtained from our center only, and no external validation was applied. Although we have separated the total patients into two cohorts, external validation of our results was still required before our findings could be applied clinically. Finally, the variables included in our study were based on our routine clinical practice. Regarding biophysical parameters, we collected only real-time recordings of PVP, CB temperature during freezes, TTI, and number of unsuccessful freezes. Other parameters such CB warming time were not included. The inclusion of more parameters might further improve the accuracy of the model.

Conclusions

This study presents a nomogram that is easy to apply and can predict the long-term efficacy and outcome of CBA. Biophysical parameters such as TTI and cryoballoon temperature have a great impact on AF recurrence. The nomogram has been shown to be superior in its predictive accuracy as compared with assessments based on conventional risk scores.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine Ruijin Hospital Ethics Committee. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

LW and NZ conducted the study; YW and CL evaluated the clinical data and wrote the main manuscript; YX, YB, and QL were in charge of the follow-up of the patients and data collection; and LW and NZ were the main operators of AF ablation. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was supported by the Multicenter Clinical Trial Project of Shanghai Jiao Tong University Medical School (DLY201604) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 81870250, 81900290, 82100329).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcvm.2023.1073108/full#supplementary-material

References

1.

Hoffmann E Straube F Wegscheider K Kuniss M Andresen D Wu LQ et al Outcomes of cryoballoon or radiofrequency ablation in symptomatic paroxysmal or persistent atrial fibrillation. Europace. (2019) 21(9):1313–24. 10.1093/europace/euz155

2.

Sano M Heeger C-H Sciacca V Große N Keelani A Fahimi BHH et al Evaluation of predictive scores for late and very late recurrence after cryoballoon-based ablation of atrial fibrillation. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. (2021) 61(2):321–32. 10.1007/s10840-020-00778-y

3.

Jastrzębski M Kiełbasa G Fijorek K Bednarski A Kusiak A Sondej T et al Comparison of six risk scores for the prediction of atrial fibrillation recurrence after cryoballoon-based ablation and development of a simplified method, the 0-1-2 PL score. J Arrhythmia. (2021) 37(4):956–64. 10.1002/joa3.12557

4.

Keçe F de Riva M Alizadeh Dehnavi R Wijnmaalen AP Mertens BJ Schalij MJ et al Predicting early reconnection after cryoballoon ablation with procedural and biophysical parameters. Hear Rhythm O2. (2021) 2(3):290–7. 10.1016/j.hroo.2021.03.007

5.

Nattel S Harada M . Atrial remodeling and atrial fibrillation: recent advances and translational perspectives. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2014) 63(22):2335–45. 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.02.555

6.

Ikenouchi T Inaba O Takamiya T Inamura Y Sato A Matsumura Y et al The impact of left atrium size on selection of the pulmonary vein isolation method for atrial fibrillation: cryoballoon or radiofrequency catheter ablation. Am Heart J. (2021) 231:82–92. 10.1016/j.ahj.2020.10.061

7.

Mamchur S Chichkova T Khomenko E Kokov A . Pulmonary veins morphometric characteristics and spatial orientation influence on its cryoballoon isolation results. Diagnostics. (2022) 12(6):1322. 10.3390/diagnostics12061322

8.

Guckel D Lucas P Isgandarova K El Hamriti M Bergau L Fink T et al Impact of pulmonary vein variant anatomy and cross-sectional orifice area on freedom from atrial fibrillation recurrence after cryothermal single-shot guided pulmonary vein isolation. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. (2022) 65(1):251–60. 10.1007/s10840-022-01279-w

9.

Chierchia G-B de Asmundis C Namdar M Westra S Kuniss M Sarkozy A et al Pulmonary vein isolation during cryoballoon ablation using the novel achieve inner lumen mapping catheter: a feasibility study. Europace. (2012) 14(7):962–7. 10.1093/europace/eus041

10.

Aryana A Mugnai G Singh SM Pujara DK de Asmundis C Singh SK et al Procedural and biophysical indicators of durable pulmonary vein isolation during cryoballoon ablation of atrial fibrillation. Hear Rhythm. (2016) 13(2):424–32. 10.1016/j.hrthm.2015.10.033

11.

Aryana A Kenigsberg DN Kowalski M Koo CH Lim HW O’Neill PG et al Verification of a novel atrial fibrillation cryoablation dosing algorithm guided by time-to-pulmonary vein isolation: results from the cryo-DOSING study (cryoballoon-ablation DOSING based on the assessment of time-to-effect and pulmonary vein isolation gu. Hear Rhythm. (2017) 14(9):1319–25. 10.1016/j.hrthm.2017.06.020

12.

Ferrero-de-Loma-Osorio Á García-Fernández A Castillo-Castillo J Izquierdo-de-Francisco M Ibáñez-Críado A Moreno-Arribas J et al Time-to-effect–based dosing strategy for cryoballoon ablation in patients with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. Circ Arrhythmia Electrophysiol. (2017) 10(12):e005318. 10.1161/CIRCEP.117.005318

13.

Wei Y Chen L Cao J Liu S Ling T Huang X et al Long-term outcomes of a time to isolation—based strategy for cryoballoon ablation compared to radiofrequency ablation in patients with symptomatic paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. (2022) 45(9):1015–23. 10.1111/pace.14556

14.

Fürnkranz A Köster I Chun KRJ Metzner A Mathew S Konstantinidou M et al Cryoballoon temperature predicts acute pulmonary vein isolation. Hear Rhythm. (2011) 8(6):821–5. 10.1016/j.hrthm.2011.01.044

15.

Watanabe R Okumura Y Nagashima K Iso K Takahashi K Arai M et al Influence of balloon temperature and time to pulmonary vein isolation on acute pulmonary vein reconnection and clinical outcomes after cryoballoon ablation of atrial fibrillation. J Arrhythmia. (2018) 34(5):511–9. 10.1002/joa3.12108

16.

Mugnai G Cecchini F Stroker E Paparella G Iacopino S Sieira J et al Durability of pulmonary vein isolation following cryoballoon ablation : lessons from a large series of repeat ablation procedures. IJC Hear Vasc. (2022) 40(April):101040. 10.1016/j.ijcha.2022.101040.

17.

Heeger C-H Popescu SS Saraei R Kirstein B Hatahet S Samara O et al Individualized or fixed approach to pulmonary vein isolation utilizing the fourth-generation cryoballoon in patients with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation: the randomized INDI-FREEZE trial. Europace. (2022) 24(6):921–7. 10.1093/europace/euab305

18.

Miyazaki S Kajiyama T Watanabe T Nakamura H Hachiya H Tada H et al Predictors of durable pulmonary vein isolation after second-generation cryoballoon ablation with a single short freeze strategy—different criteria for the best freeze of the 4 individual PVs. Int J Cardiol. (2020) 301:96–102. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2019.11.089

19.

Phlips T Taghji P El Haddad M Wolf M Knecht S Vandekerckhove Y et al Improving procedural and one-year outcome after contact force-guided pulmonary vein isolation: the role of interlesion distance, ablation index, and contact force variability in the ‘CLOSE’-protocol. Europace. (2018) 20(FI_3):f419–27. 10.1093/europace/eux376

20.

Hussein A Das M Riva S Morgan M Ronayne C Sahni A et al Use of ablation index-guided ablation results in high rates of durable pulmonary vein isolation and freedom from arrhythmia in persistent atrial fibrillation patients: the PRAISE study results. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. (2018) 11(9):e006576. 10.1161/CIRCEP.118.006576

Summary

Keywords

atrial fibrillation, cryoballoon ablation, nomogram, prediction model, post-ablation recurrence

Citation

Wei Y, Lin C, Xie Y, Bao Y, Luo Q, Zhang N and Wu L (2023) Development and validation of a novel nomogram for predicting recurrent atrial fibrillation after cryoballoon ablation. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 10:1073108. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2023.1073108

Received

18 October 2022

Accepted

24 July 2023

Published

11 August 2023

Volume

10 - 2023

Edited by

Haibo Ni, University of California, United States

Reviewed by

Jingquan Zhong, Shandong University, China Ana Margarida Lebreiro, São João University Hospital Center, Portugal

Updates

Copyright

© 2023 Wei, Lin, Xie, Bao, Luo, Zhang and Wu.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

* Correspondence: Liqun Wu wuliqun89@hotmail.com Ning Zhang dr_ningzhang@163.com

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.