Abstract

Purpose:

This study aimed to quantitatively assess left ventricular function in patients with mitral regurgitation (MR) using speckle-tracking echocardiography and further clarify its clinical application.

Methods:

PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, and Cochrane Library databases were searched from the date of establishment to November 22, 2024. Two investigators independently screened the literature, extracted data, and evaluated the quality of the included studies. Meta-analysis was performed using Stata18.0 software.

Results:

Finally, 23 studies were included, all of which scored ≥7 on the Newcastle–Ottawa scale. Meta-analysis results showed that, the left ventricular end-systolic volume index (P < 0.01), left ventricular end-diastolic volume index (P < 0.01), and left ventricular mass index (P < 0.01) of patients with MR were higher than those of healthy individuals. In contrast, the left ventricular ejection fraction (P < 0.01) and global radial strain (GRS) (P < 0.01) of patients with MR was lower than that of healthy individuals; the difference was significant. The E/A of both groups (P = 0.22), global circumferential strain (P = 0.43), global longitudinal strain (P = 0.10), left ventricular relative wall thickness (P = 0.20), and some indexes with significant heterogeneity were analyzed by subgroup according to the degree of MR. The combined results of most subgroup analysis were consistent with the overall results and the heterogeneity was reduced.

Conclusion:

There is significant difference in the GRS between patients with MR and healthy individuals, which can provide reference for evaluating left ventricular function in patients with MR.

1 Introduction

Mitral regurgitation (MR) refers to a series of cardiac pathophysiological changes and clinical symptoms caused by congenital abnormalities or acquired diseases that prevent the mitral valve from completely closing during left ventricular contraction, resulting in blood regurgitation from the left ventricle back to the left atrium. It is one of the most common heart valve diseases (HVDs). Severe MR, if not corrected in time, will cause progressive cardiac dysfunction. In addition to the requirements of long follow-up and large investigation and treatment costs in the later stages of HVD, owing to the close relationship between HVD and age, the prevalence of MR will also increase rapidly as the population ages, bringing new challenges to the global health care system (1). Speckle-tracking echocardiography (STE) uses high-frame two-dimensional gray-scale images to identify small, stable myocardial footprints or spots generated by ultrasound-myocardial tissue interaction and to obtain Doppler information about global and segmental myocardial deformation by tracking the distance or spatial displacement between spots during cardiac motion in real time (2). STE relies on measuring two-dimensional intra-tissue velocity to distinguish between normal myocardial segment motion and myocardial motion when adjacent myocardial segments are restricted or when motion of the entire heart is dysfunctional. Compared with conventional tissue Doppler imaging, STE is more consistent with Lagrangian strain theory and compared with its initial length (2). STE measurement of left atrial strain is a new detection method that has been developed in recent years. Two-dimensional STE analysis of the left atrium can obtain measurement results of atrial strain and volume, which can improve the accuracy and repeatability of left ventricular diastolic function evaluation and shorten the reporting time, which has important clinical value (3–5). Studies have shown that STE may predict cardiac function earlier than ejection fraction (6). This study aimed to evaluate left ventricular function in patients with MR using echocardiography and speckle-tracking technique and to provide a new reference for clinical diagnosis.

2 Methods

2.1 Literature search

PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, and Cochrane library databases were searched for controlled studies on left ventricular function in patients with MR evaluated by STE from the date of establishment to November 22, 2024.

2.2 Inclusion and discharge standards

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) study type: control study of patients with MR; (2) study object: clear MR diagnostic criteria; (3) measurement method and evaluation index: Use of speckle-tracking technique to assess left ventricular function and measure global longitudinal strain (GLS), global circumferential strain (GCS), global radial strain (GRS), left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), left ventricular end-diastolic volume index (LVEDVi), left ventricular end-systolic volume index (LVESVi), E/A, relative wall thickness (RWT), and left ventricular mass index (LVMI).

2.3 Exclusion criteria

We excluded (1) reviews, case reports, and abstracts from academic conferences; (2) repeated published or included studies, retaining articles with large sample size and comprehensive information; (3) studies without a healthy control group; (4) study participants suffering from valve diseases other than MR, such as tricuspid regurgitation; (5) studies for which full text or overall valid data could not be obtained.

2.4 Literature screening and data extraction

The basic data extracted included the first author's name, country, publication year, number of MR cases included, number of control groups, basic characteristics of the MR and control group populations (sex, age, smoking history, body mass index, history of hypertension and diabetes, etc.), conventional echocardiography, and speckle-tracking technology measurement parameters (LVEF, GLS, GRS, GCS, LVEDVi, LVESVi, E/A, RWT, and LVMI).

2.5 Quality evaluation

The Newcastle–Ottawa scale recommended by the American Institute for Health Care Research and Quality was used to evaluate the quality of the literature (Table 1).

Table 1

| Study (first author and year of publication) | Selection | Comparability | Outcome | Total score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bakkestrøm et al. (6) | ★★★★ | ★★ | ★★ | 7★ |

| Cameli et al. (7) | ★★★★ | ★★ | ★★★ | 9★ |

| Borg et al. (8) | ★★★★ | ★★ | ★★★ | 9★ |

| Casas et al. (9) | ★★★★ | ★ | ★★★ | 8★ |

| Dirsiene et al. (10) | ★★★★ | ★★ | ★★★ | 9★ |

| Ermakov et al. (11) | ★★★★ | ★★ | ★★★ | 9★ |

| Gelsomino et al. (12) | ★★★ | ★★ | ★★★ | 8★ |

| Florescu et al. (13) | ★★★★ | ★★ | ★★★ | 9★ |

| Huttin et al. (14) | ★★★★ | ★★ | ★★★ | 9★ |

| Kawase et al. (15) | ★★★★ | ★★ | ★★★ | 9★ |

| Luca et al. (16) | ★★★ | ★★ | ★★ | 7★ |

| Kılıcgedik et al. (17) | ★★★★ | ★★ | ★★★ | 9★ |

| Lancellotti et al. (18) | ★★★★ | ★★ | ★★★ | 9★ |

| Mihaila et al. (19) | ★★★★ | ★★ | ★★★ | 9★ |

| Rajesh et al. (20) | ★★★ | ★★ | ★★★ | 8★ |

| Sonaglioni et al. (21) | ★★★ | ★★ | ★★ | 7★ |

| Sugimoto et al. (22) | ★★★★ | ★★ | ★★★ | 9★ |

| Valuckiene et al. (23) | ★★★ | ★★ | ★★★ | 8★ |

| Tang et al. (24) | ★★★★ | ★★ | ★★★ | 9★ |

| Witkowski et al. (25) | ★★★★ | ★★ | ★★★ | 9★ |

| Zvirblyte et al. (26) | ★★★ | ★★ | ★★ | 7★ |

| Debonnaire et al. (27) | ★★★★ | ★★ | ★★★ | 9★ |

| Cameli et al. (28) | ★★★ | ★★ | ★★★ | 8★ |

Bias risk evaluation of the included studies.

2.6 Statistical analysis

Meta-analysis was performed using Stata18.0 software. A heterogeneity test (Q test) was performed to evaluate the heterogeneity among the included studies. I2 > 50% or P < 0.1 was considered as indicative of significant heterogeneity among the included studies. Meta-analysis was performed using a random-effects model; otherwise, a fixed-effects model was used. A sensitivity analysis was performed to determine the stability of the study results by removing significant changes in observations based on individual articles. Statistical indicators used included weighted mean difference (WMD) and 95% confidence interval (CI).

3 Results

-

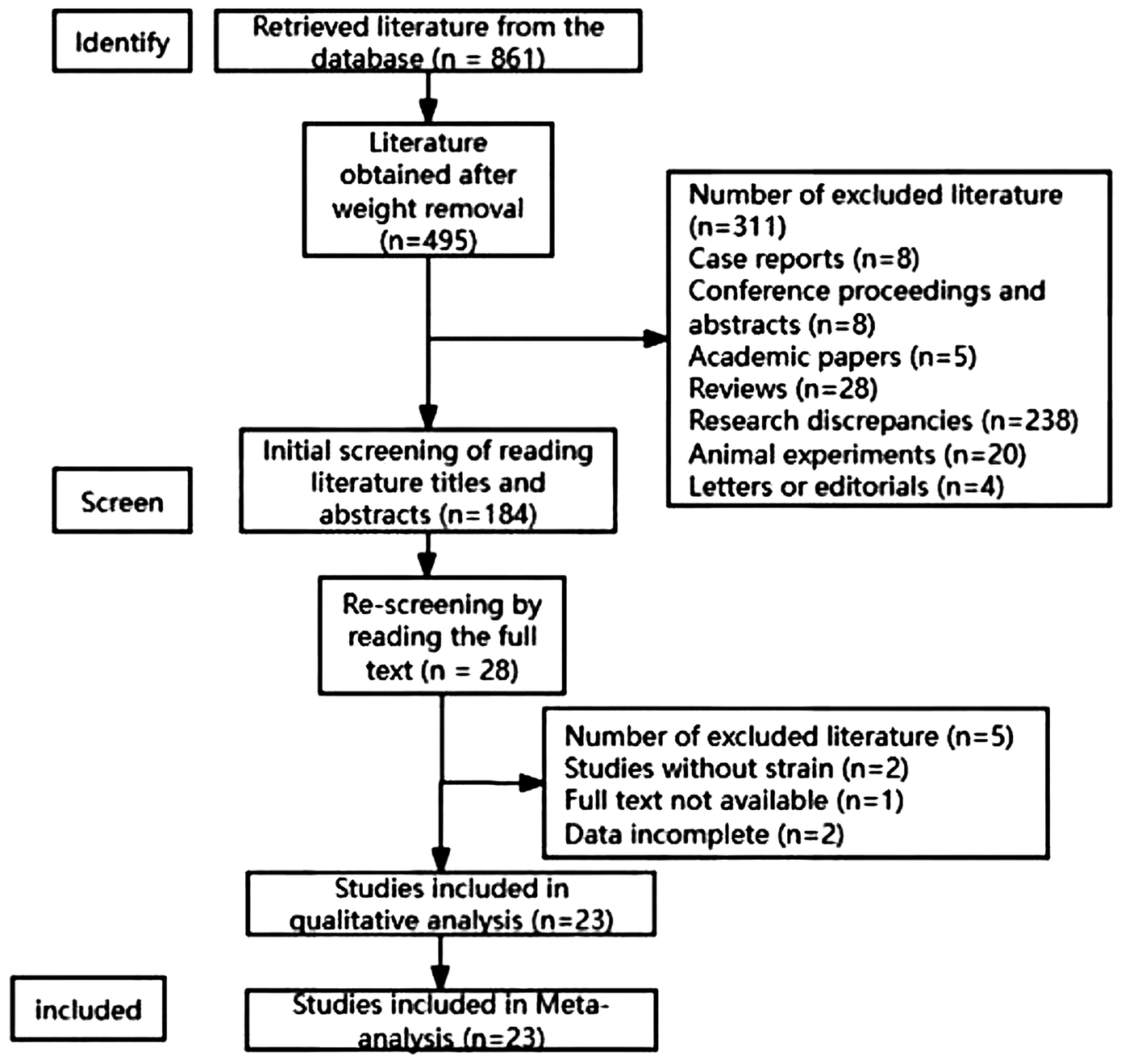

A total of 843 articles were obtained from the preliminary search and 23 that met the inclusion criteria were finally included (Figure 1). And the baseline date of all included studies shown in Table 2.

-

Meta-analysis results.

Figure 1

Flow chart of literature retrieval.

Table 2

| Study (first author and year of publication) | Sample size | Sex (male) | Age (years) | Body surface area (m2) | BMI | Smoker | Atrial fibrillation | Hypertension/blood pressure | Diabetes mellitus | Dyslipidemia |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bakkestrøm et al. (6) | 66 | 34/12 | 64 ± 9/56 ± 17 | 1.98 ± 0.18/1.89 ± 0.19 | NR | 8/0 | NR | 17/0 | 6/4 | NR |

| Cameli et al. (7) | 200 | 68/28 | 55.73 ± 12.34/55.6 ± 7.5 | 1.78 ± 0.19/1.81 ± 0.24 | 24.9 ± 4.1/24.7 ± 5.1 | 24/12 | NR | 125.9 ± 12.8/78.8 ± 8.5/122.5 ± 13.5/77.6 ± 9.4 | NR | NR |

| Borg et al. (8) | 68 | NR | 64.6/60.1 | 1.83/1.77 | NR | NR | NR | 145/82 146/84 | NR | NR |

| Casas-Rojo et al. (9) | 65 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Ermakov et al. (10) | 98 | 29/18 | 52/55 | 1.87/1.80 | NR | NR | 12/13 | 13/5 | 0/0 | NR |

| Gelsomino et al. (11) | 81 | 40/14 | 66.8 ± 6.6/66.0 ± 4.4 | 1.87 ± 1.7/1.85 ± 1.6 | 25.2 ± 1.6/23.3 ± 1.2 | NR | NR | 29/ | 16 | NR |

| Florescu et al. (12) | 38 | NR | 59 ± 13/61 ± 7 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Huttin et al. (13) | 120 | 70/16 | 58.3 ± 14.7/58.8 ± 9.2 | 24.1 ± 3.7 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Kawase et al. (14) | 108 | 34/19 | 67.6 ± 9.0/67 ± 11 | 1.64 ± 0.19/1.66 ± 0.18 | NR | 13/4 | 24/ | NR | 23/0 | 18/ |

| Luca et al. (15) | 115 | 56 | 66.4 ± 6.3 | NR | NR | NR | NR | 39/ | 26 | NR |

| Kılıcgedik et al. (16) | 94 | 49/20 | 54.3 ± 15/52.7 ± 9.4 | NR | NR | NR | 13/0 | 0/0 | 9/3 | NR |

| Kim et al. (17) | 93 | 46/21 | 54.2 ± 13.9/53.7 ± 8.3 | NR | NR | NR | 30 | NR | NR | NR |

| Lancellotti et al. (18) | 94 | 37/10 | 60.95 ± 14.4/58.4 ± 11 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Mihaila et al. (19) | 104 | 31/31 | 57 ± 15/56 ± 13 | 1.75 ± 0.2/1.82 ± 0.2 | NR | NR | NR | 132 + 20/78 + 10,127 + 17/74 + 8 | NR | NR |

| Rajesh et al. (20) | 100 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Sonaglioni et al. (21) | 120 | 32/30 | 50.1 ± 8.6/50.6 ± 11.3 | 1.81 ± 0.16/1.83 ± 0.15 | NR | 10/8 | NR | 10/8 | 6/4 | 15/12 |

| Sugimoto et al. (22) | 250 | 56/50 | 66.4 ± 12.8/59.5 ± 13.3 | NR | 25.9 ± 4.5/25.8 ± 3.8 | 35/26 | NR | 65/63 | 21/17 | 49/39 |

| Valuckiene et al. (23) | 104 | 46/21 | 61.13 ± 11.64/57.3 ± 6.1 | NR | 28.2 ± 4.2/26.6 ± 3.2 | 44/10 | NR | 41/0 | NR | 52/13 |

| Tang et al. (24) | 86 | 28/8 | 70.3 ± 8.4/69 ± 8 | 1.7 ± 0.2/1.7 ± 0.2 | NR | NR | 54/NA | NR | NR | NR |

| Witkowski et al. (25) | 162 | 76/24 | 60/60 | 1.95/1.89 | NR | NR | 15 | 32 | 5 | NR |

| Zvirblyte et al. (26) | 80 | 13/10 | 61.88 ± 12.88/57.4 ± 10.89 | 1.81 ± 0.19/1.88 ± 0.17 | NR | 2/1 | 14/1 | 31/18 | 2/2 | NR |

| Debonnaire et al. (27) | 191 | 77/47 | 63 ± 13/63 ± 12 | 1.9 ± 0.2/1.9 ± 0.21 | NR | 21/25 | 26/0 | 11/31 | 4/9 | 11/20 |

| Cameli et al. (28) | 168 | 58/27 | 68.2 ± 10.4/64.4 ± 15.5 | 1.71 ± 0.59/1.77 ± 0.2 | 24.96 ± 4.1/24.2 ± 2.2 | NR | NR | 121.5 ± 7.7/77.5 ± 7.2 | NR | NR |

Basic characteristics of the included studies (case/control groups).

BMI, body mass index; NR, not reported.

3.1 LVEF

A total of 21 studies (7–20, 22–25, 27–29) provided the LVEF results. As the heterogeneity among these studies was significant, meta-analysis was performed using a random-effects model. The results showed that the LVEF of the healthy individuals was significantly higher than that of patients with MR (P < 0.05, I2 = 95%; Figure 2).

Figure 2

Forest plot of left ventricular ejection fraction.

3.2 GLS

Nine studies (7, 8, 10, 11, 13, 17, 21, 22, 26) provided the GLS results. As the heterogeneity among these studies was significant, meta-analysis was performed using a random-effects model. The results indicated no significant differences in the GLS between healthy individuals and patients with MR (P > 0.05).

3.3 GRS

Three studies (10, 13, 21) provided the GRS results. As the heterogeneity among these studies was not significant, a fixed-effects model was used for meta-analysis. The results showed that the GRS of healthy individuals was significantly higher than that of patients with MR (P < 0.05).

3.4 GCS

Four studies (10, 21, 22, 26) provided the GCS results. As the heterogeneity among these studies was significant, a random-effects model was used for meta-analysis. The results showed no significant differences in the GCS between healthy individuals and patients with MR (P = 0.43, I2 = 93%).

3.5 LVEDVi

Nine studies (9, 11, 12, 22–26, 28) provided the LVEDVi results. Because of the significant heterogeneity among these studies, meta-analysis was performed using a random-effects model. The results showed that the LVEDVi of patients with MR was significantly higher than that of healthy individuals (P < 0.01, I2 = 98%).

3.6 LVESVi

Eight studies (7, 11, 12, 16, 24–26, 28) provided the LVESVi results. Meta-analysis was performed using a random-effects model owing to significant heterogeneity among these studies. The results showed that the LVESVi of patients with MR was significantly higher than that of healthy individuals (P < 0.01; I2 = 99%).

3.7 LVMI

Eight studies (7–9, 11, 22–24, 29) provided the LVMI results. Because of the significant heterogeneity among these studies, meta-analysis was performed using a random-effects model. The results showed that the LVMI of the healthy individuals was significantly lower than that of patients with MR (P < 0.01, I2 = 90%).

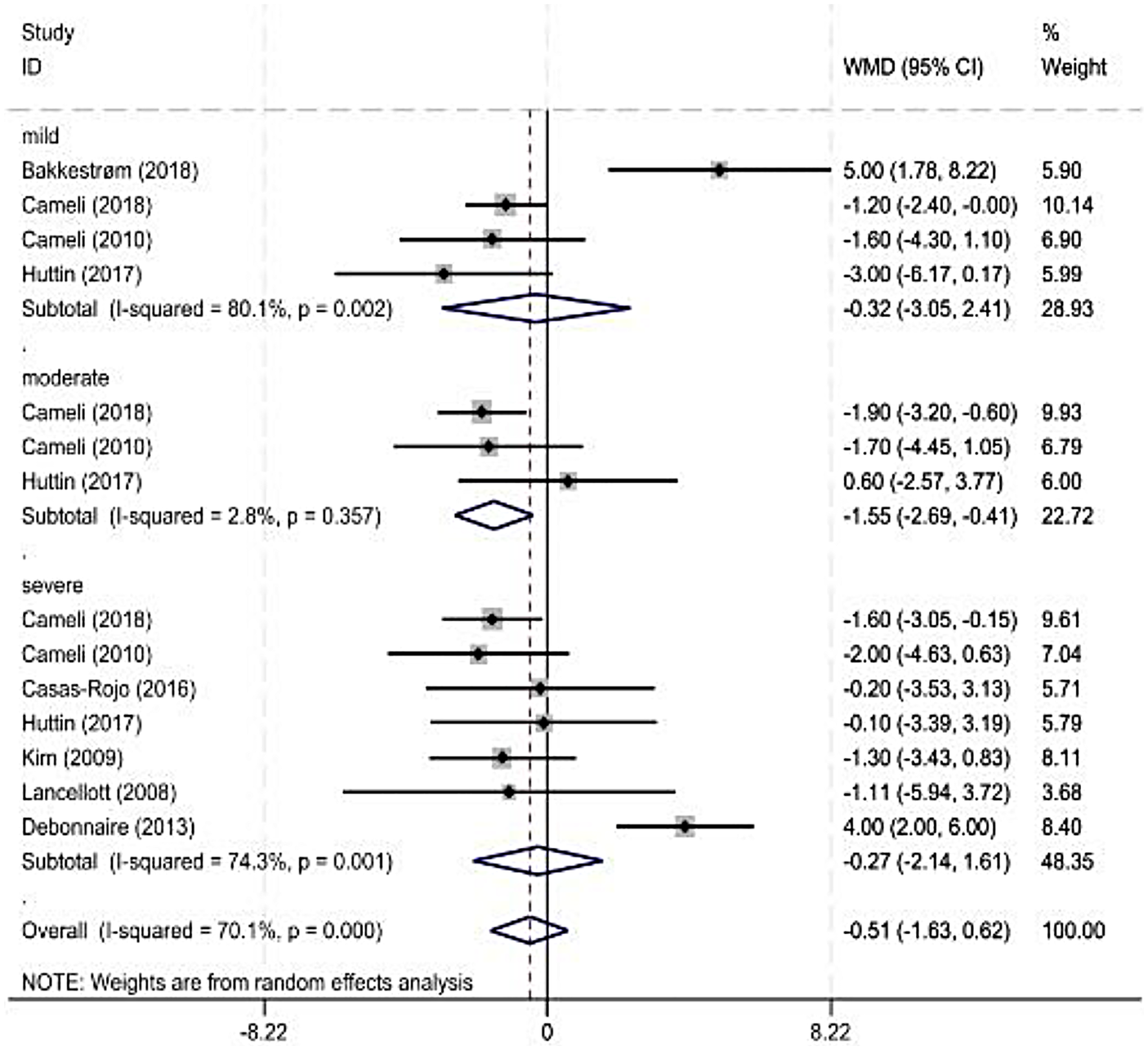

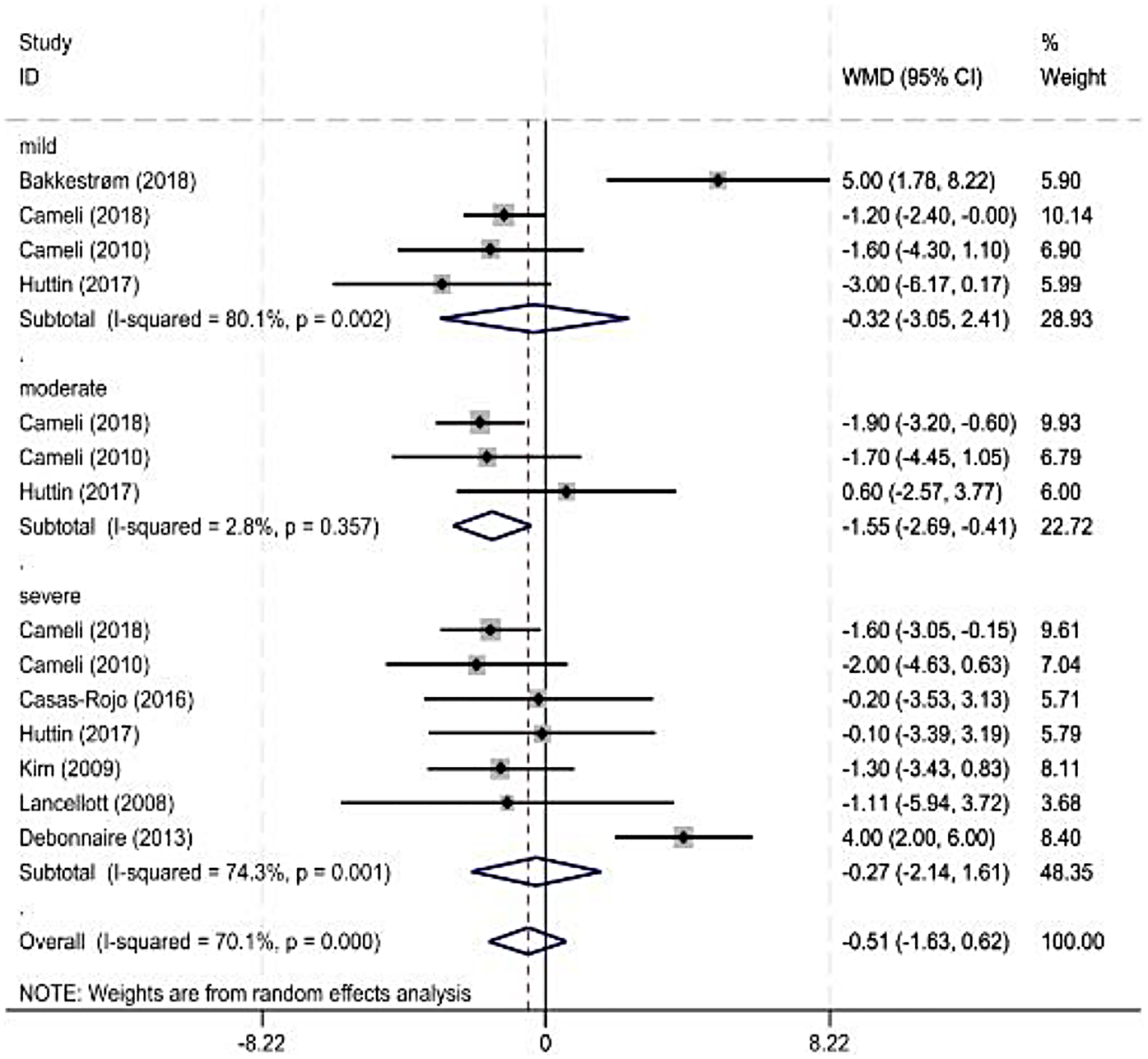

4 A subgroup analysis

As some observation indicators were significantly heterogeneous among the included studies, a subgroup analysis was performed for each observation indicator according to the severity classification of MR (American Society of Echocardiography standard). The main observation indicator was the LVEF, and its results are shown in Figure 3 and Table 3. The combined results for other indicators with reduced heterogeneity are also shown in Table 3.

Figure 3

Forest plot of left ventricular ejection fraction subgroup.

Table 3

| Outcome indicator | Number of included studies |

Heterogeneity test results | Effect model | Meta-analysis results | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P | I 2 (%) | OR/WMD (95% CI) | P | |||

| E/A | 5 | <0.01 | 96 | Random | 0.19 (−0.11, 0.49) | 0.22 |

| Mild | 2 | 0.08 | 68 | Random | −0.31 (−0.52, −0.11) | <0.01 |

| Moderate | 2 | 0.79 | 0 | Random | −0.30 (−0.41, −0.19) | <0.01 |

| Severe | 2 | 0.38 | 0 | Random | −0.24 (−0.39, −0.09) | <0.01 |

| GCS | 4 | <0.01 | 94 | Random | 2.88 (−1.29, 7.06) | 0.43 |

| GLS | 9 | <0.01 | 94 | Random | 1.43 (−0.26, 3.12) | 0.10 |

| GRS | 3 | 0.98 | 0 | Fixed | −8.55 (−9.11, −7.00) | <0.01 |

| LVEF | 21 | 0.00 | 95 | Random | −3.82 (−6.20, −1.45) | <0.01 |

| Mild | 4 | <0.01 | 80 | Random | −0.32 (−3.05, 2.41) | 0.82 |

| Moderate | 3 | 0.36 | 3 | Random | −1.55 (−2.69, −0.41) | 0.01 |

| Severe | 8 | <0.01 | 88 | Random | −1.66 (−4.28, 0.96) | 0.78 |

| LVESVi | 8 | <0.01 | 99 | Random | 12.45 (4.05, 20.85) | <0.01 |

| LVEDVi | 9 | <0.01 | 98 | Random | 17.72 (7.53, 27.90) | <0.01 |

| RWT | 5 | <0.01 | 96 | Random | 0.04 (−0.02, 0.10) | 0.20 |

| Mild | 3 | <0.01 | 99 | Random | 0.26 (−0.02, 0.54) | 0.06 |

| Moderate | 3 | <0.01 | 100 | Random | −0.11 (−0.36, 0.14) | 0.39 |

| Severe | 3 | <0.01 | 97 | Random | 0.04 (−0.08, 0.17) | 0.49 |

| LVMI | 8 | <0.01 | 90 | Random | 31.08 (22.92, 41.25) | <0.01 |

Results of meta-analysis of outcome indicators.

OR, odds ratio; WMD, weighted mean difference; CI, confidence interval; GCS, global circumferential strain; GLS, global longitudinal strain; GRS, global radial strain; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVESVi, left ventricular end-systolic volume index; LVEDVi, left ventricular end-diastolic volume index; RWT, relative wall thickness, LVMI, left ventricular mass index.

4.1 LVEF

Four (7, 14, 29) and eight studies were included in the mild and severe subgroups, respectively, in the LVEF subgroup analysis according to the degree of MR. A random-effects model was used for the analysis. The results showed no significant difference in the LVEF between healthy individuals and patients with MR. Three studies were included in the moderate-MR subgroup. Heterogeneity was significant; therefore, a random-effects model was used. The results showed a significant difference in the LVEF between healthy individuals and patients with MR.

4.2 E/A

Subgroup analysis of E/A according to the degree of MR was performed and two studies (8, 29) were included. The heterogeneity of E/A across different severities of MR was significant; therefore, a random-effects model was used for the analysis. The results of the subgroup analysis showed that the E/A of patients with mild, moderate, and severe MR were significantly lower than those of healthy individuals (P < 0.01), and the heterogeneity was significantly reduced.

4.3 RWT

Three studies (7, 8, 29) were included in the subgroup analysis of left ventricular RWT. The results of the subgroup analysis showed no significant difference in left ventricular RWT between healthy individuals and patients with different degrees of MR, and there was no significant change in heterogeneity.

5 Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analysis of each observation index with significant heterogeneity was carried out by eliminating one study at a time. The results showed that The results did not change significantly, suggesting that they were stable.

6 Publication bias

Funnel plots were constructed using Stata18.0 software, and publication bias was identified using the Egger's test. The funnel plots of all observation indicators were not significantly asymmetric, and the publication bias results of the observation indicators obtained using the Egger's test were as follows: GLS, LVEF, GRS, GCS, LVMI, RWT, LVEDVi, E/A. The above data showed that there was no significant publication bias in the above indexes. However, LVESVi (P = 0.03) showed a publication bias. Further analysis using the clipping method showed that the random-effects result after adding one dummy data point [Hedges = 1.12, 95% CI (0.29,1.97)] was not reversed with the random-effect outcome of LVESVi before adding the dummy data point [Hedges = 1.29, 95% CI (0.48,2.10)]; therefore, although there was publication bias for this index, the outcome was still robust.

7 Discussion

MR is a common HVD. Given the rapid aging of the global population, HVD is expected to become the next “heart epidemic.” Accurately assessing the cardiac function of patients with MR is important to assist in clinical diagnosis and early intervention. Therefore, improving the prognosis of patients with MR is crucial. This study analyzed the cardiac function of patients with MR using STE. Nakagawa et al. (30) proposed that left ventricular function was impaired and end-diastolic volume index was increased in patients with MR, which was consistent with the results of our study that LVEDVi [WMD = 21.29, 95% CI (0.49, 32.09), P < 0.01, I2 = 98%] of patients with MR was higher than that of healthy individuals. Other studies have demonstrated (31) that a strong linear relationship exists between valvular regurgitation volume and LVEDVi and that left ventricular volume better reflects ventricular remodeling in patients with MR. LVESVi is associated with mortality and symptoms in patients with aortic regurgitation (32). We suspect that LVESVi can also be used to assess cardiac function in patients with MR. Our meta-analysis results showed that LVESVi [WMD = 12.45, 95% CI (−4.05, 20.85), P < 0.01, I2 = 99%] of patients with MR was significantly higher than that of healthy individuals. A recent study (33) reported that the LVESVi was an independent predictor of postoperative left ventricular dysfunction in patients with chronic degenerative MR. This study further illustrates the importance of LVESVi for the assessment of left ventricular function in patients with MR. In addition, our results showed that the LVMI [WMD = 32.08, 95% CI (22.92, 41.25), P < 0.01, I2 = 90%] and LVEF [WMD = −3.82, 95% CI (−6.20, −1.45), P < 0.01, I2 = 95%] of patients with MR was significantly lower, whereas their GRS [WMD = −8.55, 95% CI (−9.11, −7.00), P < 0.01, I2 = 0%] was significantly lower, compared with healthy individuals. These results indicate reduced cardiac function in patients with MR, which is consistent with the results from the study by Shechter et al., who argued that LVEF decline in patients with MR was driven primarily by reduced total stroke volume and diffuse myocardial contractility (34). Previous studies have shown that the GLS (35) can directly reflect myocardial motion and better assess myocardial function. The GLS is lower in symptomatic patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement. The GCS is positively correlated with ejection fraction, whereas atrioventricular valve regurgitation is negatively correlated with it (6). The RWT is considered (36) an index for evaluating ventricular hypertrophy; however, it cannot distinguish patients with aortic regurgitation from healthy individuals. In our study, we found no significant difference in the E/A, GCS, GLS or RWT between patients with MR and healthy individuals, which is inconsistent with the results of previous studies. This may be because of the small number and small sample size of the included studies, and the results of this study were affected by baseline data, such as sex and age. Subgroup analysis of some indicators with significant heterogeneity according to the degree of MR showed that the combined results of most subgroup analyses of the observed indicators were consistent with the overall results, and the heterogeneity was reduced. Cardiac strain is affected by sex and age, with one study in 2011 showing a significant decrease in strain values with age (37) and another showing lower strain values in healthy men than in women (38). Sex-stratified analysis was not performed in this study, and the influence of sex on the results cannot be excluded. Further studies stratifying data based on confounding factors, such as sex and age, are needed. Some studies have shown differences in the cardiac strain measured using different ultrasound techniques and software, whereas others have shown insignificant differences based on such factors. However, further studies are needed to confirm this view.

MR is often divided into ischemic (such as mitral regurgitation caused by coronary artery disease) and non-ischemic (all other causes) according to the cause. According to the mechanism, it can be divided into functional (normal mitral valve structure, valve deformation caused by ventricular remodeling) and organic (valve itself disease) (39), this study included The original studies entered did not group different mechanisms or causes of mitral regurgitation, but only made simple frequency statistics, and most studies did not involve different mechanisms or causes. There was insufficient data to support subgroup analysis. Therefore, more studies are needed to analyze the impact of different causes or mechanisms of mitral regurgitation on cardiac function. In addition, according to different causes and mechanisms, the choice of intervention measures for patients with mitral regurgitation is different. The use of drugs and surgical repair will affect the prognosis of mitral regurgitation and improve atrioventricular remodeling, thereby further improving the strain index and atrioventricular function (40). Due to the pathological changes in the valve itself, the use of drugs in organic mitral regurgitation is relatively functional. The effect in patients with cusp regurgitation, especially ischemic mitral regurgitation, was not significant, which affected the results of our study. Some of the people included in this study used drugs to improve cardiac function, but the original study did not explain the use of drugs in detail, which made it impossible to conduct a comparative analysis between the drug group and the non-drug group, which also led to the limitations of the study. In addition, some indicators, such as the GLS and GCS, were rarely included in the statistical analysis of this study, and the sample size was small; therefore, the study results have certain limitations. Although this study has some limitations, the results are consistent with observations from clinical practice and are reliable.

In addition, transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) can also evaluate mitral valve structure and function. As an important tool for mitral valve repair surgery, TEE can determine the mechanism and severity of mitral regurgitation, as well as assess the severity of residual regurgitation and the diagnosis of other complications after surgery. For minimally invasive mitral valve surgery, TEE can also evaluate the position of extracorporeal circulation cannulation (41–43). Further studies could incorporate TEE to evaluate cardiac function in patients with mitral regurgitation.

To address the above limitations, larger sample sizes and more studies are needed to explore the reliability of myocardial strain in evaluating cardiac function in patients with mitral regurgitation. It is expected to detect cardiac function abnormalities earlier than the reduction of LVEF, thereby guiding diagnosis and treatment.

8 Conclusion

Conventional echocardiographic parameters, such as the LVEF, LVEDVi, LVESVi, and LVMI, can assess ventricular function in patients with MR, and the myocardial strain parameter, GRS, obtained using speckle-tracking technology can also assess left ventricular function in patients with MR, providing more comprehensive evidence for monitoring cardiac function.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

JZ: Methodology, Writing – original draft, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. QQ: Writing – original draft, Visualization, Conceptualization, Validation, Supervision.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This study was supported by Gansu Provincial Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine and the Key Project of Gansu Provincial Joint Research Fund (project number: 25JRRA1219).

Acknowledgments

Thank you for taking time out of your busy work to review my paper. Your effort have enabled my research results to be better presented to reader. I'm really thankful to Gansu Provincial Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine for giving me this platform, and the chief physician, Qun Qiang for guiding this study. And I'm also grateful to all my colleagues for their support and the suggestions they offered.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcvm.2025.1644591/full#supplementary-material

References

1.

d'Arcy JL Prendergast BD Chambers JB Ray SG Bridgewater B . Valvular heart disease: the next cardiac epidemic.Heart. (2011) 97(2):91–3. 10.1136/hrt.2010.205096

2.

Collier P Phelan D Klein A . A test in context: myocardial strain measured by speckle-tracking echocardiography.J Am Coll Cardiol. (2017) 69(8):1043–56. 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.12.012

3.

Morris DA Belyavskiy E Aravind-Kumar R Kropf M Frydas A Braunauer K et al Potential usefulness and clinical relevance of adding left atrial strain to left atrial volume index in the detection of left ventricular diastolic dysfunction. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. (2018) 11(10):1405–15. 10.1016/j.jcmg.2017.07.029

4.

Modin D Biering-Sørensen SR Møgelvang R Alhakak AS Jensen JS Biering-Sørensen T . Prognostic value of left atrial strain in predicting cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in the general population.Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. (2019) 20(7):804–15. 10.1093/ehjci/jey181

5.

Thomas L Muraru D Popescu BA Sitges M Rosca M Pedrizzetti G et al Evaluation of left atrial size and function: relevance for clinical practice. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. (2020) 33(8):934–52. 10.1016/j.echo.2020.03.021

6.

Shiraga K Ozcelik N Harris MA Whitehead KK Biko DM Partington SL et al Imposition of fontan physiology: effects on strain and global measures of ventricular function. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. (2021) 162(6):1813–22. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2021.02.034

7.

Bakkestrøm R Christensen NL Wolsk E Banke A Dahl JS Andersen MJ et al Layer-specific deformation analysis in severe aortic valve stenosis, primary mitral valve regurgitation, and healthy individuals validated against invasive hemodynamic measurements of heart function. Echocardiography. (2018) 35(2):170–8. 10.1111/echo.13747

8.

Cameli M Mandoli GE Nistor D Lisi E Massoni A Crudele F et al Left heart longitudinal deformation analysis in mitral regurgitation. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. (2018) 34:1741–51. 10.1007/s10554-018-1391-4

9.

Borg AN Harrison JL Argyle RA Ray SG . Left ventricular torsion in primary chronic mitral regurgitation.Heart. (2008) 94(5):597–603. 10.1136/hrt.2007.126284

10.

Casas-Rojo E Fernández-Golfin C Moya-Mur JL González-Gómez A García-Martín A Morán-Fernández L et al Area strain from 3D speckle-tracking echocardiography as an independent predictor of early symptoms or ventricular dysfunction in asymptomatic severe mitral regurgitation with preserved ejection fraction. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. (2016) 32:1189–98. 10.1007/s10554-016-0904-2

11.

Ermakov S Gulhar R Lim L Bibby D Fang Q Nah G et al Left ventricular mechanical dispersion predicts arrhythmic risk in mitral valve prolapse. Heart. (2019) 105(14):1063–9. 10.1136/heartjnl-2018-314269

12.

Gelsomino S van Garsse L Lucà F Parise O Cheriex E Rao CM et al Left ventricular strain in chronic ischemic mitral regurgitation in relation to mitral tethering pattern. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. (2013) 26(4):370–80. 10.1016/j.echo.2013.01.011

13.

Florescu M Benea DCCM Rimbas RC Cerin G Diena M Lanzzillo G et al Myocardial systolic velocities and deformation assessed by speckle tracking for early detection of left ventricular dysfunction in asymptomatic patients with severe primary mitral regurgitation. Echocardiography. (2012) 29(3):326–33. 10.1111/j.1540-8175.2011.01563.x

14.

Huttin O Pierre S Venner C Voilliot D Sellal JM Aliot E et al Interactions between mitral valve and left ventricle analysed by 2D speckle tracking in patients with mitral valve prolapse: one more piece to the puzzle. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. (2017) 18(3):323–31. 10.1093/ehjci/jew075

15.

Kawase Y Kawasaki M Tanaka R Nomura N Fujii Y Ogawa K et al Noninvasive estimation of pulmonary capillary wedge pressure in patients with mitral regurgitation: a speckle tracking echocardiography study. J Cardiol. (2016) 67(2):192–8. 10.1016/j.jjcc.2015.04.012

16.

Luca' F Van Garsse L Rao CM Cheriex E Puntrello G Rubino G et al Left atrial strain and strain rate before and following restrictive annuloplasty for ischaemic mitral regurgitation evaluated by two-dimensional speckle tracking echocardiography. Eur Heart J. (2013) 34(Suppl 1):P4748. 10.1093/eurheartj/eht310.P4748

17.

Kılıcgedik A Kahveci G Gurbuz AS Karabay CY Guler A Efe SC et al Papillary muscle free strain in patients with severe degenerative and functional mitral regurgitation. Arq Bras Cardiol. (2017) 108:339–46. 10.5935/abc.20170035

18.

Kim M-S Kim Y-J Kim H-K Han J-Y Chun H-G Kim H-C et al Evaluation of left ventricular short-and long-axis function in severe mitral regurgitation using 2-dimensional strain echocardiography. Am Heart J. (2009) 157(2):345–51. 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.10.004

19.

Lancellotti P Cosyns B Zacharakis D Attena E Van Camp G Gach O et al Importance of left ventricular longitudinal function and functional reserve in patients with degenerative mitral regurgitation: assessment by two-dimensional speckle tracking. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. (2008) 21(12):1331–6. 10.1016/j.echo.2008.09.023

20.

Mihaila S Muraru D Miglioranza MH Piasentini E Aruta P Cucchini U et al Relationship between mitral annulus function and mitral regurgitation severity and left atrial remodelling in patients with primary mitral regurgitation. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. (2016) 17(8):918–29. 10.1093/ehjci/jev301

21.

Rajesh GN Shyam Lakshman SG Vellani H Sajeev CG Thomas B . Strain patterns in primary mitral regurgitation due to rheumatic heart disease and mitral valve prolapse.Indian Heart J. (2020) 73(1):85–90. 10.1016/j.ihj.2020.11.010

22.

Sonaglioni A Nicolosi GL Lombardo M Gensini GF Ambrosio G . Influence of chest conformation on myocardial strain parameters in healthy subjects with mitral valve prolapse.Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. (2021) 37:1009–22. 10.1007/s10554-020-02085-z

23.

Sugimoto T Bandera F Generati G Alfonzetti E Barletta M Losito M et al Left atrial dynamics during exercise in mitral regurgitation of primary and secondary origin: pathophysiological insights by exercise echocardiography combined with gas exchange analysis. Cardiovascular Imaging. (2020) 13(1 Pt 1):25–40. 10.1016/j.jcmg.2018.12.031

24.

Valuckiene Z Ovsianas J Ablonskyte-Dudoniene R Mizariene V Melinyte K Jurkevicius R . Left ventricular mechanics in functional ischemic mitral regurgitation in acute inferoposterior myocardial infarction.Echocardiography. (2016) 33(8):1131–42. 10.1111/echo.13240

25.

Tang Z Fan Y-T Wang Y Jin C-N Kwok K-W Lee AP-W . Mitral annular and left ventricular dynamics in atrial functional mitral regurgitation: a three-dimensional and speckle-tracking echocardiographic study.J Am Soc Echocardiogr. (2019) 32(4):503–13. 10.1016/j.echo.2018.11.009

26.

Witkowski TG Thomas JD Delgado V van Rijnsoever E Ng ACT Hoke U et al Changes in left ventricular function after mitral valve repair for severe organic mitral regurgitation. Ann Thorac Surg. (2012) 93(3):754–60. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2011.11.034

27.

Žvirblytė R Merkytė I Tamulėnaitė E Saniukaitė A Mizarienė V Ereminienė E et al Right ventricle mechanics and function during stress in patients with asymptomatic primary moderate to severe mitral regurgitation and preserved left ventricular ejection fraction. Medicina (B Aires). (2020) 56(6):303. 10.3390/medicina56060303

28.

Debonnaire P Leong DP Witkowski TG Al Amri I Joyce E Katsanos S et al Left atrial function by two-dimensional speckle-tracking echocardiography in patients with severe organic mitral regurgitation: association with guidelines-based surgical indication and postoperative (long-term) survival. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. (2013) 26(9):1053–62. 10.1016/j.echo.2013.05.019

29.

Cameli M Lisi M Giacomin E Caputo M Navarri R Malandrino A et al Chronic mitral regurgitation: left atrial deformation analysis by two-dimensional speckle tracking echocardiography. Echocardiography. (2011) 28(3):327–34. 10.1111/j.1540-8175.2010.01329.x

30.

Nakagawa M Shirato K Ohyama T Sakuma M Takishima T . Left ventricular end-systolic stress-volume index ratio in aortic and mitral regurgitation with normal ejection fraction.Am Heart J. (1990) 120(4):892–901. 10.1016/0002-8703(90)90207-E

31.

Uretsky S Supariwala A Nidadovolu P Khokhar SS Comeau C Shubayev O et al Quantification of left ventricular remodeling in response to isolated aortic or mitral regurgitation. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. (2010) 12(1):32. 10.1186/1532-429X-12-32

32.

Anand V Yang L Luis SA Padang R Michelena HI Tsay JL et al Association of left ventricular volume in predicting clinical outcomes in patients with aortic regurgitation. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. (2021) 34(4):352–9. 10.1016/j.echo.2020.11.014

33.

Althunayyan AM Alborikan S Badiani S Wong K Uppal R Patel N et al Determinants of post-operative left ventricular dysfunction in degenerative mitral regurgitation. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. (2023) 24(9):1252–7. 10.1093/ehjci/jead093

34.

Shechter A Kaewkes D Lee M Makar M Patel V Koren O et al Correlates and prognostic implications of LVEF reduction after transcatheter edge-to-edge repair for primary mitral regurgitation. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. (2024) 25(1):136–47. 10.1093/ehjci/jead210

35.

Desai MY Akintoye E . Left ventricular global longitudinal strain before TAVR: time to jump the ejection fraction ship?Cardiovascular Imaging. (2023) 16(3):342–4. 10.1016/j.jcmg.2023.01.011

36.

Douglas PS Reichek N Plappert T Muhammad A Sutton MSJ . Relative wall thickness analysis by two-dimensional echocardiography.Am Heart J. (1985) 110(5):1012–9. 10.1016/0002-8703(85)90202-9

37.

Zghal F Bougteb H Réant P Lafitte S Roudaut R . Assessing global and regional left ventricular myocardial function in elderly patients using the bidimensional strain method.Echocardiography. (2011) 28(9):978–82. 10.1111/j.1540-8175.2011.01476.x

38.

Takigiku K Takeuchi M Izumi C Yuda S Sakata K Ohte N et al Normal range of left ventricular 2-dimensional strain–Japanese ultrasound speckle tracking of the left ventricle (JUSTICE) study–. Circ J. (2012) 76(11):2623–32. 10.1253/circj.CJ-12-0264

39.

Enriquez-Sarano M Akins CW Vahanian A . Mitral regurgitation.Lancet. (2009) 373(9672):1382–94. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60692-9

40.

Dell’Era G Rondano E Franchi E Marino PN . Atrial asynchrony and function before and after electrical cardioversion for persistent atrial fibrillation. Eur J Echocardiogr. (2010) 11:577–83. 10.1093/ejechocard/jeq010

41.

Thys DM Abel MD Brooker RF Connis RT Duke PG Nickinovich DG et al Practice guidelines for perioperative transesophageal echocardiography. Anesthesiology. (2010) 112(5):1084–96. 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181c51e90

42.

Aybek T Doss M Abdel-Rahman U Simon A Miskovic A Risteski PS et al Echocardiographic assessment in minimally invasive mitral valve surgery. Med Sci Monit. (2005) 11(4):MT27–32.

43.

Yao W Gang W Jia-Li W . Transesophageal echocardiography guided cannulation for peripheral cardiopulmonary bypass during robotic cardiac surgery. Chin Med J. (2012) 125(18):3236–9. 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0366-6999.2012.18.007

Summary

Keywords

speckle-tracking echocardiography, mitral regurgitation, GRS, GCS, GLS

Citation

Zhang J and Qiang Q (2025) Echocardiographic evaluation of left ventricular function in patients with mitral regurgitation: a meta-analysis. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 12:1644591. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2025.1644591

Received

10 June 2025

Revised

23 November 2025

Accepted

24 November 2025

Published

09 December 2025

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Michel Puceat, Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale (INSERM), France

Reviewed by

Luminita Iliuta, Carol Davila University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Romania

Yi Wang, University of Electronic Science and Technology of China, China

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Zhang and Qiang.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

* Correspondence: Qun Qiang qiangqun82@126.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.