- 1Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons, Columbia University, New York, NY, United States

- 2College of Dental Medicine, Columbia University, New York, NY, United States

Background: Internationalization efforts, including global health activities, in dental education can play an important role in preparing future oral healthcare professionals. To date, in the available literature, there is no common understanding of what internationalization of dental education might mean, and there are no agreed-upon standards relating to, or a common definition of, the term internationalization of dental education. Here, the authors investigate what has been published in the above area from 01/01/2000 to 12/31/2020, identifying perceived motivations and formats. A proposed definition and connection to the field of international higher education are provided.

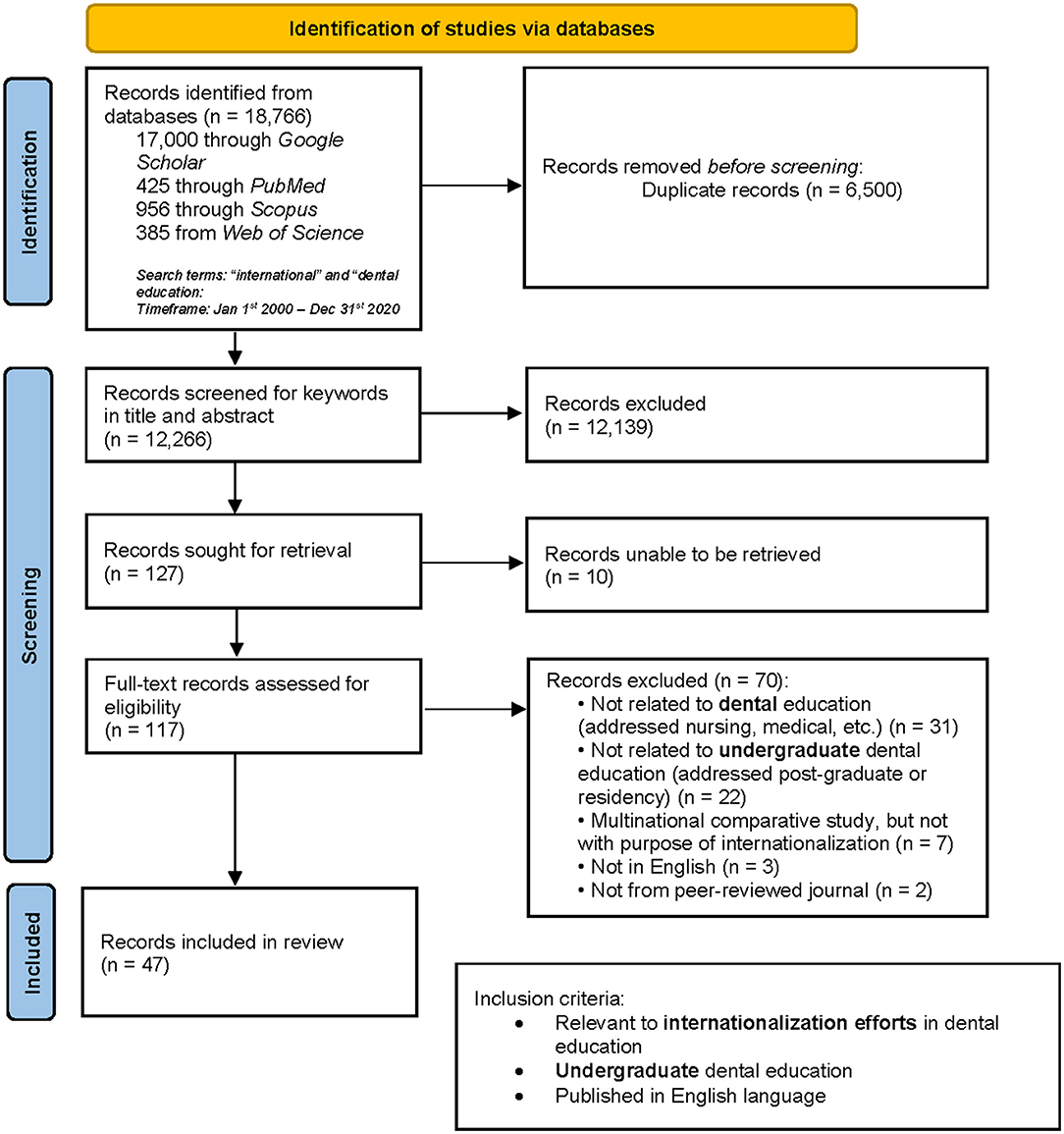

Methods: A scoping review of published literature was performed and identified 47 relevant articles. The articles were thematically sorted based on educational formats and concepts (previously established in international higher education) and motivations.

Results: Despite the paucity of articles directly addressing internationalization of dental education, there was a large variety of articles on topics that were identified to correlate with international higher education, ranging from international partnerships, student mobility, and language, to international curriculum at home—with different perceived motivations, including competition, international understanding, and social transformation.

Discussion: More research on internationalization of dental education is needed to provide guidelines and formalize standards for international educational goals to better align formats and motivations for international efforts in dental education.

Background

The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the need for global leadership, international communication, international collaborative public health action, and global biomedical science discovery for the health professions. To improve our global healthcare world, an understanding of healthcare outside of one's country is important.

Historically, the field of dentistry has been a distinct health profession, training students and graduates primarily locally, and having limited overlap with the other health professions.

Only very recently has the awareness of oral health as a component of the foundation for general health brought the field closer to the areas of medicine and public health. On a global scale, oral medicine has been included as a part of general health by the WHO (1). However, global awareness of dentistry as a global healthcare field remains limited (1).

As oral healthcare further integrates with the medical profession and as global issues affect local practice, an understanding of dentistry as a global field will be of importance for future graduates of dental schools (2). Even if providers never practice outside their home countries, international influences driven by population migration, workforce exchanges, global technology, and global pandemics have an impact on local practice.

Dental schools should prepare themselves to provide students with skills in international collaboration, the means to address cultural differences, and the competence to become globally-minded, equitable healthcare providers—thus, increasing understanding of being a part of the global healthcare community and engendering global citizens to promote equity both locally and abroad (3, 4). Furthermore, global standards in internationalization efforts are deemed necessary to better prepare all graduates for global oral healthcare challenges. A broader understanding of formats of internationalization efforts and the establishment of global standards, policies, or recommendations that consider motivations for documented internationalization efforts is needed to help current dental educators provide all graduates with skills in understanding the global practice of dentistry and healthcare.

Internationalization of Higher Education (IoHE)

To properly contextualize this article, it is helpful to define the authors' understanding of the term “internationalization of dental education” (herein referred to as IoDE) and how the authors derived it from another area of education—internationalization of higher education (IoHE).

IoHE refers to an established and defined area of educational research that has been in place for over 25 years and provides frameworks for IoHE (5). The field of IoHE encompasses research and development regarding internationalization of the curriculum; referring to the incorporation of international, intercultural, and global dimensions into higher education in ways that are relevant to graduates' professional practice (6), with the aim to reach all students. Motivations for IoHE include quality improvement, provision of access, competitiveness, growth, and financial profits—resulting in the provision of a professionally relevant education that prepares all students to be interculturally proficient professionals and citizens (7–9).

IoHE includes comprehensive formats to bring global, intercultural, and international dimensions into higher education—from abroad or from within one's home country (9–11). IoHE can occur on many levels within academia, including the institutional, faculty, student, and curriculum levels. Major methods for IoHE can include but are not limited to areas of institutional international partnerships, student inbound and outbound mobility, and internationalization of the curriculum via international faculty, students, global content, and campus internationalization (12–14). A growing area of investigation is IoHE “at home” (9, 14).

It appears that such formats and methods from IoHE are not extensively studied in the health professions (15). Particularly, a link between IoHE and dental education appears to be missing in the global literature.

Differences Between Global Health, Public Health, Global Oral Health, Public Health Dentistry, and IoDE

In the health professions, incorporating elements of social equity, diversity, inclusivity, and cultural competence into healthcare education are increasingly emphasized. In this context, health professions' internationalization efforts often become intertwined and overlap with Public Health and Global Health (GH) (16). While these areas are related and overlap, it is important to identify the differences in their commonly used definitions.

Public Health is regarded as “…the science and art of preventing disease, prolonging life, and promoting health through the organized efforts and informed choices of society, organizations, public and private communities, and individuals…” (17).

GH, as the global counterpart of Public Health, historically evolved from International Health—an area that addresses local, national, and international health concerns on all levels. International health is defined by Merson, Black, and Mills as “the application of the principles of Public Health to problems and challenges that affect low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) and to the complex array of global and local forces that influence them” (18–20).

The definition of GH varies (21). The most commonly accepted definition of GH describes it as: “an area for study, research, and practice that places a priority on improving health and achieving health equity for all people worldwide” (19). Despite this broad definition, the term GH is often associated with educational services or programs coordinated by high-income countries (HICs) of the Global North that are enacted in the LMICs of the Global South [as defined by the World Bank (22)] and/or local programs to address health equity and social justice. GH education is the area of training that focuses on health issues directly or indirectly caused by transnational factors affecting the health of all people (19, 23).

Similarly, in dental education, international efforts are often centered on the term “Global Oral Healthcare” (GOH). GOH is mostly used to refer to international educational efforts to improve oral dentistry and oral healthcare in the context of GH—often, and primarily led by efforts initiated by the Global North to improve oral healthcare in the Global South. Similar to other health professions, GOH is often understood as an extracurricular activity and involves students' international outbound mobility to the Global South, and/or is conveyed via dedicated GH programs (24). Educational competencies taught in GOH education can include teaching intercultural awareness, appreciation of different healthcare systems, and understanding global disease burdens (25, 26).

Dental Public Health or Public Health Dentistry refers to areas of dental care that address the issues of social justice and equity in oral care and is referred to as “the science and art of preventing and controlling dental diseases and promoting dental health through organized community efforts.” (27).

Definition of “Internationalization of Dental Education”

IoDE is a term that is related to the above areas. However, while there are overlapping elements (e.g., identification and research of learning objectives), IoDE is not considered an additional content area in dental education. It is an area that incorporates educational formats to address internationalization efforts in dental education. It identifies and investigates the above fields which can be applied and standardized for dental educators to use in practice. Because of this distinction as an educational concept, a separate definition is deemed necessary.

We adapt a definition based on one commonly applied in the field of IoHE (9, 14, 28). Hence, we define IoDE as “the process of purposefully integrating international, intercultural, or global dimensions into dental education in order to enhance its quality and prepare all graduates for professional practice in a globalized world” (9, 14, 28).

Thus, this definition establishes IoDE as a concept of educational processes—with a focus on processes for intentional, systematic, and evidence-based activities designed to ensure that students achieve specific learning outcomes by engaging in high-quality learning experiences.

Motivations for IoDE

Motivations for IoHE are determined by constantly changing political, economic, socio-cultural, and academic influences and rationales (3). Understanding motivations for IoDE may yield insight into strengths and weaknesses of programmatic efforts and can aid in successes of future endeavors in an area that is still evolving.

Justification for the Study

In this scoping review of efforts regarding IoDE formats found in the recent published literature, the authors aim to identify commonalities with elements of IoHE, and recognize gaps that exist in the published literature that may have implications for the dental educator community. This article investigates if and how internationalization efforts in dental education have been executed and published to date, and what perceived major motivations led to these formats. Establishing a baseline of its current status is important to further develop formats and recommendations for IoDE.

This research is important for dental educators not only to identify motivations but also to learn from and apply formats of IoDE that have been published. Identifying parallels with and gaps in relation to IoHE may help dental educators to understand internationalization efforts from an educational format perspective and help to standardize curricula and initiate innovation in IoDE. Since IoDE is a relatively new area, this study may help educators establish educational theory-based international programs. Thus, this study can have future implications for dental education.

Methods

A scoping review of articles was performed utilizing the research question: “What articles have been published in scientific journals in the past 20 years that include elements of IoDE?” A five step process was implemented, following Arksey and O'Malley's framework (29). Three researchers (A. S., A. W., and Z. R.) conducted the searches, read the articles, and assigned articles by thematic coding.

Identification of Relevant Studies

Google Scholar, PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science databases were selected in order to focus on both peer-reviewed health sciences journals and non-health-related scientific journals (Figure 1). Searches included articles published from January 1, 2000, to December 31, 2020. This timeline was selected due to the emphasis on internationalization efforts in other health professions that arose soon after the turn of the 21st century (30); before then, publications on internationalization efforts in the health professions were infrequent. The study's searches were conducted from November, 2020 to February, 2021. Articles not published or indexed before the end date (December 31st, 2020) of each database search were not included in the results.

Because the term “internationalization of dental education” itself is not yet appropriately employed in the literature, the intentionally broad key words “international” and “dental education” were utilized for the initial identification of potentially relevant articles. Titles and abstracts were then manually parsed for keywords “global” and “internationalization” to further identify articles.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria (Figure 1). Included articles were limited to undergraduate dental education. All formats for peer-reviewed articles were included (i.e., research articles, letters, commentaries, and reports). All countries were included. All languages were considered. However, articles not written in English were marked to indicate that content could not be validated and were not included in the final analysis. Nevertheless, abstracts in English were included. Articles comparing multi-national dental curricula, if not pertaining to internationalization efforts in dental education, were not included.

Study Selection

A total of 47 articles were found to be suitable for the review (Figure 1). The initial screening of titles and abstracts was conducted individually, followed by group discussions. The group met several times to discuss discrepancies regarding inclusion or exclusion until consensus was achieved. The senior author made the final decision.

Charting of Data

Review of abstracts and full texts was used to sort the articles into themes of educational concepts previously established in IoHE. The authors focused the thematic analysis on formats of comprehensive IoHE that have been previously identified in IoHE (5, 6, 9, 10, 12, 31). Formats focused on major areas outlined by the American Council on Education (5), including institutional international partnerships, student mobility, curriculum, and international efforts at home.

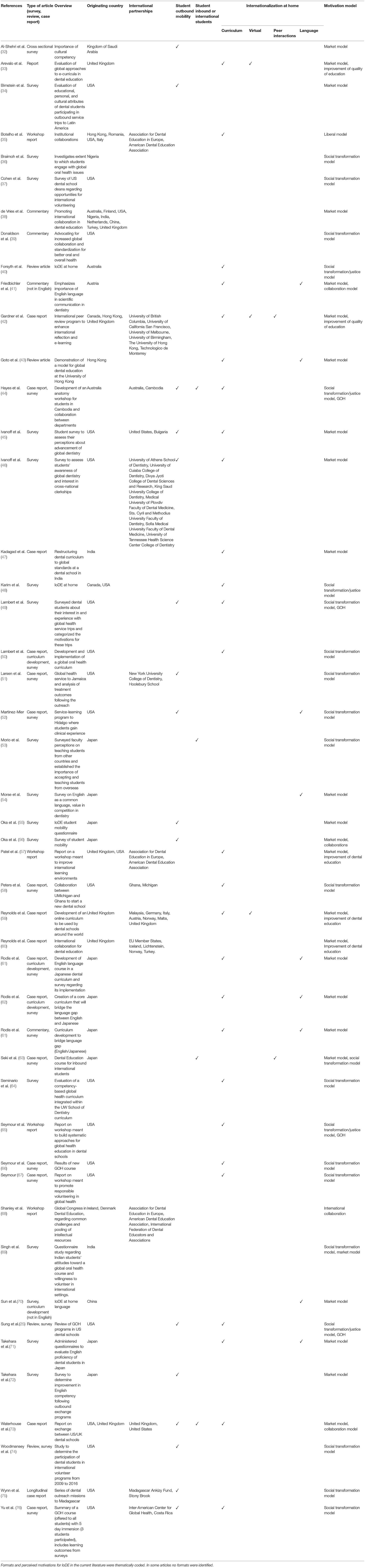

Furthermore, themes for perceived motivations for IoDE, referencing Hanson's model (15), were categorized based on inference of the author's perceived motivation. These motivations included (1) IoDE in order to engage in a competitive market model, (2) a liberal model to foster international understanding and collaborations, and (3) a social transformation model to support health equity and social justice/Global Health. Further details regarding the models of motivation are described in the discussion section.

Once themes were identified, the articles were charted (Table 1).

Summary of Results

Overall, the search identified 47 articles published between 01/01/2000 and 12/31/2020.

Thematic assignment of articles identified similar major elements to those established in IoHE, as outlined in the method section (5, 15).

Origin of Articles

A large majority (43/47, 91.4%) of articles originated from HICs, notably, with a limited number of involved institutions [including the Harvard School of Dental Medicine (49, 50, 64–67, 76), Tokyo Medical and Dental University (53, 63, 71, 72), and Hong Kong University (35, 42, 43)] producing nearly one-third (30%) of these articles. Furthermore, 7 authors were considered highly-published in this area with more than 1 publication in the final analysis (30, 31, 33–35, 38, 39, 44–52). Only 4/47 (8.5%) articles originated from middle-income countries (36, 47, 69, 70). There were no scholarly articles originating from low-income countries.

A cohort of 5/47 (10.6%) articles were about internationalization in Europe, reflecting collaboration between the US and Europe (35, 38, 46, 73, 77). Of the 13 articles that included international partnerships, 9/13 (69%) described efforts in the LMICs, but all were published by authors and journals originating in HICs (44, 46, 51, 58–60, 75, 76, 78).

Type of Articles

Articles included a wide range of topics and were mostly descriptive in nature. The articles focused on international partnerships, student inbound and outbound mobility (including global oral health programs), and 30/47 articles (63.8%) included elements of international curriculum at home activities, including language programs (25, 33, 35, 41–50, 52, 54, 57–59, 61, 62, 64–67, 70, 71, 73, 76, 79, 80). There were 27/47 (57.4%) articles that discussed projects regarding the creation of a global dental curriculum (25, 33, 35, 41–50, 57–59, 61, 62, 64–67, 71, 73, 76, 79, 80).

Many articles (31/47, 66%) included surveys within the study (25, 32, 34, 36, 37, 44–46, 48–56, 58, 61–64, 66, 67, 70–72, 74, 76, 79).

Institutional Partnerships and Networks

Some articles (14/47, 29%) addressed international partnerships for dental education—often between countries of the Global North (i.e., European partnerships or ADA/European networks) (1, 35, 42, 44–46, 51, 57, 59, 60, 68, 73, 75, 76). Partnerships between the Global North and the LMICs, aimed at providing mission trips for student mobility and/or that addressed areas of GOH, were described in 8/47 (17.0%) articles (44–46, 51, 58, 59, 75, 76).

Student Inbound and Outbound Mobility

Student exchanges were addressed in 16/47 (34%) articles—mainly as service missions to LMICs (25, 32, 34, 44–46, 49, 51, 52, 55, 56, 71, 73–76). Only 4/47 (8.5%) articles covered the topic of international inbound students (44, 53, 63, 73).

Internationalization of the Curriculum

Internationalization of the curriculum was addressed in 16/47 (34%) articles—via GOH courses in 7/47 (14.9%) articles (25, 48, 49, 64, 67, 69, 76), or language programs in 9/47 (19.1%) articles (41, 43, 52, 54, 61, 62, 70, 71, 79).

Motivation

Perceived motivations for IoDE were based on Hanson's motivation models (as listed in the methods section). Multiple themes for motivations were coded for in 15/47 (32%) articles (25, 33, 41, 42, 44, 48, 49, 56, 59, 60, 63, 65, 69, 77, 80).

The English language in dentistry as a common international element to give students a competitive edge in the global market was discussed in 9/47 (19.1%) of articles, which were coded as the market model (41, 43, 52, 54, 61, 62, 70, 71, 79). There were 27/47 (57.4%) articles that addressed a global dental curriculum which were coded for this theme as well (25, 33, 35, 41–50, 57–59, 61, 62, 64–67, 71, 73, 76, 79, 80).

The main reasons found for international travel were to provide service in the Global South while obtaining skills in cultural competency and were considered as part of the social transformation model, as described in 22/47 (46.8%) articles (25, 36, 37, 39, 44, 48–53, 58, 63–67, 74–76, 80).

Discussion

This scoping review delineates articles that have been published in the peer-reviewed literature on the topic of IoDE. The goal was not to give a comprehensive review of all articles published, but to demonstrate findings and gaps regarding this topic; to clarify key concepts and examine this emerging area without giving answers or solutions (81). The analysis was based on concepts, formats, and motivations identified and derived from an educational field (IoHE) outside the health sciences. There are a few observations that are important to highlight.

Concepts in IoHE and IoDE

This study bases its analysis on concepts in IoHE to highlight findings regarding the gaps and commonalities between IoDE and IoHE. Particularly, the authors focused on the motivations for IoDE and its formats—based on elements found in comprehensive IoHE.

Gaps

Limited Articles

While there are reports about best practices in GOH (65) and international experiences, this study suggests that reporting on IoDE has not found a place in published peer reviewed journals in dental education.

The search has been challenging for several reasons:

1) There appears to be a lack of commonly used and agreed-upon key words for international and global educational activities in dental education. Despite the application of very broad key words and very generous search criteria, only 47 articles were identified for inclusion. Some articles addressed areas of education that are not typically found in research of IoHE but were included because it was felt appropriate to highlight these areas (i.e., articles on globally shared curricula). Evidenced by the wide range of articles and topics found, there appears to be a missing commonly agreed-upon understanding and definition for IoDE. Therefore, the authors suggest the definition outlined in the introduction of this article.

2) Overall paucity of articles. In a span of two decades (2000–2020), only 47 articles fit the criteria that this global study was hoping to capture. A similar search in medical education, conducted by the authors of this article, for US based medical programs yielded a similar number of articles (30) in that time span from just one country. While more international programs and activities likely exist, it appears that there is a lack of academic interest or focus for publishing in this area of dental education. Academia relies heavily on collaborations and sharing of research data. Therefore, a lack of reporting and sharing will prevent a field from expanding and ultimately impacts its success.

Standardized learning objectives, formats, and processes of how to apply IoDE are not agreed upon to date. If dental education is to adapt concepts in IoDE, attention needs to be paid to several areas that are currently lacking publication in the literature. Of note, the study was a global snapshot and the limited representation appears to be a worldwide phenomenon not limited to certain regions.

3) IoDE is a new area of education. IoDE as a research field is still in its infancy. Dental educators with experience and interest in international education are still low in number (i.e., DMD/DDS with a joint degree in Master of Public Health, Doctor of Public Health) and very often may not publish their work. Thus, research in this area originates from very few individuals. In this study, seven investigators published more than one article on IoDE—often from the same institution or group of writers (45, 46, 49, 50, 61, 62, 79).

Formats of IoDE and Their Relation to Concepts in IoHE

Comprehensive IoHE is comprised of many factors that have to align for its success (82). Major components include institutional partnerships (including partnering for off-shore campuses) (11), student mobility (inbound and outbound), and international activities at home (9, 13).

Institutional Partnerships

There appears to be an underreporting in the published literature about partnerships in IoDE, indicating limited research of the motivations and outcomes of these partnerships. In the 14 articles with reported partnerships, 4 involved the pairing of a school in the HICs with one or more schools in the LMICs (44, 47, 58, 76). Collaborative efforts of HICs, with HIC interactions focused on dental curricula development, were described in 5 articles (35, 42, 57, 60, 73). Such collaborations are typically not described in other health professions education (30); however, they need to take place in order to identify best practices.

Student Exchanges

Internationalization via inbound/outbound mobility remains a mainstay in IoHE (3, 12). Student exchange as a form of internationalization has been adapted in many disciplines, including the health professions (83). Student outbound mobility in dental education is reported (25) but to a lesser extent compared with other health professions (30)—only 16 articles were found. Furthermore, validation and outcomes research on goals is still limited (55, 56, 65, 69). However, if IoDE is to be implemented to a larger extent, research on outcomes of such programs is needed, and standardized formats need to be agreed upon.

Short-term exchanges are currently practiced in one direction (i.e., Global North to LMICs), rather than bilaterally. For the LMICs, short-term exchanges (in comparison to costly degree program exchanges) with institutions of the HICs can promote equity and internationalization.

International inbound student mobility is a major format in IoHE. In dentistry, inbound international students to the HICs often do not return home to practice, which results in a lack of expert practitioners and limits improvement of dentistry in the LMICs. More research is needed to investigate how the liberal model can be applied without resulting in a “brain drain” from LMICs (84).

Internationalization “at Home” (IaH)

IaH programs promote equity by providing equitable opportunities for internationalization to more/all dental students and institutions. IaH appears to be gaining increased interest, particularly due to safety concerns during the global COVID-19 pandemic (85–87). IaH elements can include campus internationalization via inbound international students, or activities at home via global health courses, language courses, (9, 13), etc.

Limited work has been published on IaH in dental education (40, 86). The current work demonstrates that IaH elements depend primarily on workshops (65, 67) and courses (48, 76), and the need for the English language as a concept of IaH (41, 61, 70, 79)—with only one article referencing international peer exposure (42). Virtual international programming can support approaches to IoDE/IaH by leveraging technology for IoDE (88).

Motivations for IoDE

Hanson describes three models regarding motivations for internationalization in the health professions (15). Despite overlaps, a look at these motivations individually is important in order to align goals and formats in IoDE.

The market model focuses on competition and positioning of academic institutions in the global marketplace. Often this is achieved via international partnerships (11). Our findings indicate that the market model is predominant in IoDE. The above is in contrast to studies in other health professions, where the social transformation model is predominant (30, 89).

In this review, articles addressing the creation of global dental curricula were perceived by the authors as being part of the market model and were included in the study as an observational finding. In the global literature on IoHE, shared global teaching curricula are typically not part of formats outlined in IoHE. In the health professions, the adaptation of Westernized curricula and training has been a topic for discussion (90, 91), often regarded as an indicator for improved quality of medical education and care (90, 92, 93). For the LMICs, it can be regarded as an advantage for competition. However, its ethical implications and cultural misalignment have often been challenged (90, 91). To date, such discussions are limited in dental education (94, 95). LMICs have followed a Westernization of the dental curricula, as historically, dentistry was less available in the LMICs and development followed the Western lead. Therefore, LMICs did not see the need to restart building curricula. If the LMICs aim for standard curricula to enhance this field in their respective countries, consideration of global educational curricula that are sensitive to cultural and local needs may be necessary in the future.

The topic of a common language for internationalization does play a role in international competition (96). English has been the predominant language since WWII. Therefore, countries and schools aim to provide their graduates with English language skills in order to share scientific knowledge and to remain competitive in the world ranking. Although not explicitly stated as a motivation, articles that described the theoretical benefits of language programs were coded as motivation for the market model—creating a global workforce and/or enhancing competition (41, 55, 61, 62, 70, 71, 79). Of note, two articles found in this category were published in non-English journals with English abstracts (41, 70).

The liberal model focuses on the promotion of international and intercultural understanding—introduced to IoHE in the post-WWII era (97). This model often involves the inbound and outbound exchange of students to support peace and international collaboration. While there are active international student exchanges, very limited reporting and research have been found (71). However, particularly during a time of rising global healthcare nationalism, the ambassadorial role of students for international understanding (“soft diplomacy”) plays an important role in IoHE (97).

The social transformation model emphasizes cross-cultural understanding and healthcare for social justice. For articles that addressed GOH, humanitarian, altruistic goals, and service work experiences for students may be the underlying motivations (25, 44, 69, 74, 76). Such focus mirrors similar activities in other healthcare fields—driven by student and faculty interest in volunteering to support countries in need (16). However, humanitarian work is not available at all institutions and is limited to privileged students and select institutions only. Thus, the way social transformation is currently practiced, often with a one-sided approach, is limited in scope and not socially equitable as it excludes healthcare students from low socioeconomic backgrounds and institutions with limited means.

Conclusion

IoDE is an important concept for the future of dental graduates. To date, IoDE is a poorly researched and rather novel field. Publications are dominated by the countries of the Global North and global curricula aim to duplicate Western models. Although efforts in the countries of the Global North have been made to incorporate international experiences into student training (25), to date, these experiences are limited in scope, lack agreed-upon and standardized learning objectives, and mostly focus on service trips to LMICs and/or underserved regions.

Motivations and formats from IoHE can be found in IoDE, but there is still limited reporting and it is mostly represented from the perspective of the Global North. The predominance of the HICs in the literature on IoDE may overlook important views from the LMICs. Thus, increased involvement of the LMICs is needed. Including research from the Global South will be more equitable and socially-just. Limited reports on outcomes and educational research exist regarding IoDE programs (49, 52, 66, 86), but are important to determine if approaches are achieving educational goals, and to provide guidelines and formalize standards for international educational objectives.

It is reasonable to expect that motivations for IoDE may be impacted by the recent global COVID-19 pandemic, and that the focus of international educational goals may shift to skills in multilateral international collaboration, rather than traditional one-sided international service travel exchange. Therefore, this report presents a timely opportunity to initiate a discussion among dental educators on how to best standardize and streamline internationalization efforts before many programs begin “reinventing the wheel.”

The current time presents an opportunity to implement IoDE curricula that can address new healthcare challenges, and equitably improve oral healthcare globally and locally.

Disclosure

The manuscript has been read and approved by all authors. Requirements for authorship have been met. The presented information is not provided in another form.

Author Contributions

AW: initiated concept, idea, data analysis, and draft of manuscript. AS and ZR: data analysis and editing of manuscript. MK, EL, and LT: discussion of manuscript. LZ and CK: discussion and editing of manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Michael Fortgang for review of the manuscript.

Abbreviations

GH, Global Health; GOH, Global Oral Healthcare; IoDE, Internationalization of dental education; IoHE, Internationalization of higher education; IaH, Internationalization “at home”; HICs, High-income countries; LMICs, Low- and middle-income countries.

References

1. Petersen PE. Global policy for improvement of oral health in the 21st century–implications to oral health research of World Health Assembly 2007, World Health Organization. Community Dentistry Oral Epidemiol. (2009) 37:1–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2008.00448.x

2. Wu A, Noel GPJC, Leask B, Unangst L, Choi E, De Wit H. Internationalisation of Medical Education Is Now Vital. University World News (2020).

3. De Wit H, Hunter F, Howard L, Egron-Polak E. Internationalisation of Higher Education. Brussels: European Parliament (2015). Available online at: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2015/540370/IPOL_STU(2015)540370_EN.pdf (accessed December, 2021).

4. Wu A, Kielstein H, Sakurai T, Noel G, Viranta-Kovanen S, Chien C-L, et al. Internationalization of medical education—building a program to prepare future leaders in healthcare. Med Sci Educ. (2019) 29:535–47. doi: 10.1007/s40670-019-00695-4

5. Education ACo. What Is Comprehensive Internationalization? (2021). Available online at: https://www.acenet.edu/Research-Insights/Pages/Internationalization/CIGE-Model-for-Comprehensive-Internationalization.aspx (accessed December, 2021).

6. Leask B. Internationalizing the Curriculum. London: Taylor & Francis (2015). doi: 10.4324/9781315716954

7. Clifford V. Engaging the disciplines in internationalising the curriculum in the disciplines. Int J Acad Dev. (2009) 14:133–43. doi: 10.1080/13601440902970122

8. Leask B, Bridge C. Comparing internationalisation of the curriculum in action across disciplines: theoretical and practical perspectives. Compare J Comp Int Educ. (2013) 43:79–101. doi: 10.1080/03057925.2013.746566

9. Beelen J, Jones E. Redefining internationalization at home. In: The European Higher Education Area. Amsterdam University of Applied Sciences. London: Springer (2015). p. 59–72. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-20877-0_5

10. Deardorff DK, Charles Harvey. Leading internationalization. In: Darla K, Deardorff HC, editor. A Handbook for International Education Leaders. Sterling, VA: Association of International Education Administrators (AIEA) and Stylus (2018). p. 187.

11. Hudzik JK. Comprehensive internationalization. In: Jones E, editor. Institutional Pathways to Success. London; New York, NY: Routledge - Taylor Francis (2015). p. 279.

12. Hudzik J. Comprehensive internationalization. In: Steiner J, editor. From Concept to Action. Washington, DC: NAFSA: Assocation of International Educators (2011). p. 44.

13. Leask B. Internationalizing the curriculum in the disciplines—imagining new possibilities. J Stud Int Educ. (2013) 17:103–18. doi: 10.1177/1028315312475090

14. Leask B. Using formal and informal curricula to improve interactions between home and international students. J Stud Int Educ. (2009) 13:205–21. doi: 10.1177/1028315308329786

15. Hanson L. Internationalising the curriculum in health. In: Green W, Whitsed, C., editors. Critical Perspectives on Internationalising the Curriculum in Disciplines. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers (2015). p. 175–87. doi: 10.1007/978-94-6300-085-7_12

16. Khan OA, Guerrant R, Sanders J, Carpenter C, Spottswood M, Jones DS, et al. Global health education in U.S. medical schools. BMC Med Educ. (2013) 13:3. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-13-3

17. Winslow C. Introduction to Public Health. Center for Disease Control (2020). Available online at: https://www.cdc.gov/publichealth101/public-health.html (accessed December, 2021).

18. Brown TM, Cueto M, Fee E. The World Health Organization and the transition from “international” to “global” public health. Am J Public Health. (2006) 96:62–72. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.050831

19. Koplan J, Bond TC, Merson M, Reddy KS, Rodriguez MH, Sewankambo NK. Towards a common definition of global health. Lancet. (2009) 373:1993–5. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60332-9

20. Merson M, Black A, Mills A. International Public Health: Diseases, Programs, Systems, and Policies. 2nd ed. Sudbury, MA: Jones and Bartlett Publishers (2006).

21. Havemann M, Bösner S. Global Health as “umbrella term” - a qualitative study among Global Health teachers in German medical education. Glob Health. (2018) 14:32. doi: 10.1186/s12992-018-0352-y

22. World Bank. World Bank Country and Lending Groups. (2022). Available online at: https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups (accessed March, 2022).

23. Beaglehole R, Bonita R. What is global health? Glob Health Action. (2010) 3:10.3402/gha.v3i0.5142. doi: 10.3402/gha.v3i0.5142

24. Peluso MJ, Forrestel AK, Hafler JP, Rohrbaugh RM. Structured global health programs in U.S. medical schools: a web-based review of certificates, tracks, and concentrations. Acad Med. (2013) 88:124–30. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182765768

25. Sung J, Gluch JI. An assessment of global oral health education in U.S. dental schools. J Dental Educ. (2017) 81:127–34. doi: 10.1002/j.0022-0337.2017.81.2.tb06257.x

26. Battat R, Seidman G, Chadi N. Global health competencies and approaches in medical education: a literature review. BMC Med Educ. (2010) 10:94. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-10-94

27. Yoder KM, Edelstein BL. CHAPTER 30 - the child in contexts of family, community, and society. In: Dean JA, Avery DR, McDonald RE, editors. McDonald and Avery Dentistry for the Child and Adolescent, 9th Edn. Saint Louis, MI: Mosby (2011). p. 663–71. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-323-05724-0.50034-5

28. Knight J. Updated definition of internationalization. Int Higher Educ. (2003) 33:2. doi: 10.6017/ihe.2003.33.7391

29. Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. (2005) 8:19–32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616

30. Wu A, Leask B, Choi E, Unangst L, de Wit H. internationalization of medical education-a scoping review of the current status in the United States. Med Sci Educ. (2020) 30:1693–705. doi: 10.1007/s40670-020-01034-8

31. Altbach PG. Global Perspective on Higher Education. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Univeristy Press (2016). p. 352.

32. Al-Shehri HA, Al-Taweel SM, Ivanoff CS. Perceptions of Saudi dental students on cultural competency. Saudi Med J. (2016) 37:208–11. doi: 10.15537/smj.2016.2.13013

33. Arevalo CR, Bayne SC, Beeley JA, Brayshaw CJ, Cox MJ, Donaldson NH, et al. Framework for e-learning assessment in dental education: a global model for the future. J Dental Educ. (2013) 77:564–75. doi: 10.1002/j.0022-0337.2013.77.5.tb05504.x

34. Bimstein E, Gardner QW, Riley JL, Gibson RW. Educational, personal, and cultural attributes of dental students' humanitarian trips to Latin America. J Dental Educ. (2008) 72:1493–509. doi: 10.1002/j.0022-0337.2008.72.12.tb04629.x

35. Botelho M, Oancea R, Thomas HF, Paganelli C, Ferrillo PJ. Global networking: meeting the challenges, facilitating collaboration. Eur J Dental Educ. (2018) 22:3–9. doi: 10.1111/eje.12340

36. Braimoh O, Odai E. A survey of dental students on global oral health issues in Nigeria. J Int Soc Prev Community Dentistry. (2014) 4:17–21. doi: 10.4103/2231-0762.127210

37. Cohen DW. A tradition of supporting dental education in the Middle East. In: Compendium of Continuing Education in Dentistry. Jamesburg, NJ: Aegis Dental Network Compendium in Continuing Education in Dentistry (2013).

38. De Vries J, Murtomaa H, Butler M, Cherrett H, Ferrillo P, Ferro MB, et al. The global network on dental education: a new vision for IFDEA. Eur J Dental Educ. (2008) 12:167–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0579.2007.00498.x

39. Donaldson ME, Gadbury-Amyot CC, Khajotia SS, Nattestad A, Norton NS, Zubiaurre LA, et al. Dental education in a flat world: advocating for increased global collaboration and standardization. J Dental Educ. (2008) 72:408–21. doi: 10.1002/j.0022-0337.2008.72.4.tb04506.x

40. Forsyth CJ, Irving MJ, Tennant M, Short SD, Gilroy JA. Teaching cultural competence in dental education: a systematic review and exploration of implications for indigenous populations in Australia. J Dental Educ. (2017) 81:956–68. doi: 10.21815/JDE.017.049

41. Friedbichler M, Friedbichler I, Türp JC. [Scientific communication in the age of globalization. Trends, challenges and initial solutions for dentistry in German-speaking countries]. Schweiz Monatsschr Zahnmed. (2008) 118:1193–212. doi: 10.1007/s00103-011-1328-8

42. Gardner K, Bridges S, Walmsley D. International peer review in undergraduate dentistry: enhancing reflective practice in an online community of practice. Eur J Dental Educ. (2012) 16:208–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0579.2012.00743.x

43. Goto TK. The education system at the faculty of dentistry, the University of Hong Kong: a global standard in dental education. Dental Med Res. (2014) 34:6–11. doi: 10.7881/dentalmedres.34.6

44. Hayes JA, Ivanusic JJ, le Roux CM, Hatzopoulos K, Gonsalvez D, Hong S, et al. Collaborative development of anatomy workshops for medical and dental students in Cambodia. Anat Sci Educ. (2011) 4:280–4. doi: 10.1002/ase.238

45. Ivanoff CS, Ivanoff AE, Yaneva K, Hottel TL, Proctor HL. Student perceptions about the mission of dental schools to advance global dentistry and philanthropy. J Dental Educ. (2013) 77:1258–69. doi: 10.1002/j.0022-0337.2013.77.10.tb05600.x

46. Ivanoff CS, Yaneva K, Luan D, Andonov B, Kumar RR, Agnihotry A, et al. A global probe into dental student perceptions about philanthropy, global dentistry and international student exchanges. Int Dental J. (2017) 67:107–16. doi: 10.1111/idj.12260

47. Kadagad P, Tekian A, Pinto PX, Jirge VL. Restructuring an undergraduate dental curriculum to global standards–a case study in an Indian dental school. Eur J Dental Educ. (2012) 16:97–101. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0579.2011.00726.x

48. Karim A, Mascarenhas AK, Dharamsi S. A global oral health course: isn't it time? J Dental Educ. (2008) 72:1238–46. doi: 10.1002/j.0022-0337.2008.72.11.tb04606.x

49. Lambert RF, Wong CA, Woodmansey KF, Rowland B, Horne SO, Seymour B. A National survey of U.S. dental students' experiences with international service trips. J Dental Educ. (2018) 82:366–72. doi: 10.21815/JDE.018.036

50. Lambert RF, Yu A, Simon L, Cho JG, Barrow J, Seymour B. Developing an open access, competency-based global oral health curriculum: a global health starter kit. J Dental Educ. (2020) 84:176–85. doi: 10.21815/JDE.019.176

51. Larsen CD, Larsen MD, Kim M, Yang E, Brown N, Cunningham RP. Sequential years of dental outreach to Jamaica. Gains toward improved caries status of children. N Y State Dental J. (2014) 80:40–5.

52. Martinez-Mier EA, Soto-Rojas AE, Stelzner SM, Lorant DE, Riner ME, Yoder KM. An international, multidisciplinary, service-learning program: an option in the dental school curriculum. Educ Health. (2011) 24:259.

53. Morio I, Kawaguchi Y, Suda H, Eto K. Educating overseas students: just another responsibility or a chance to grow for faculty? Eur J Dental Educ. (2000) 4:128–32. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0579.2000.040307.x

54. Morse Z, Nakahara S. English language education in Japanese dental schools. Eur J Dental Educ. (2001) 5:168–72. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0579.2001.50405.x

55. Oka H, Ishida Y, Hong G. Study of factors related to the attitudes toward studying abroad among preclinical/clinical undergraduate dental students at three dental schools in Japan. Clin Exp Dent Res. (2018) 4:119–24. doi: 10.1002/cre2.114

56. Oka H, Ishida Y, Hong G, Nguyen PTT. Perceptions of dental students in Japanese national universities about studying abroad. Eur J Dental Educ. (2018) 22:e1–6. doi: 10.1111/eje.12212

57. Patel US, Shapira L, Gallagher JE, Davis J, Garcia LT, Valachovic RW. ADEA-ADEE shaping the future of dental education III. J Dental Educ. (2020) 84:117–22. doi: 10.1002/jdd.12026

58. Peters MC, Adu-Ababio F, Jarrett-Ananaba NP, Johnson LA. Students' clinical learning in an emerging dental school: an investigation in international collaboration between Michigan and Ghana. J Dental Educ. (2013) 77:1653–61. doi: 10.1002/j.0022-0337.2013.77.12.tb05644.x

59. Reynolds P. UDENTE (Universal Dental E-Learning) a golden opportunity for dental education. Bull Group Int Rech Sci Stomatol Odontol. (2012) 50:11–9.

60. Reynolds PA, Eaton KA, Paganelli C, Shanley D. Nine years of DentEd — a global perspective on dental education. Br Dental J. (2008) 205:199–204. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2008.698

61. Rodis OMM, Locsin RC. The implementation of the Japanese Dental English core curriculum: active learning based on peer-teaching and learning activities. BMC Med Educ. (2019) 19:256. doi: 10.1186/s12909-019-1675-y

62. Rodis OM, Barroga E, Barron JP, Hobbs J, Jayawardena JA, Kageyama I, et al. A proposed core curriculum for dental English education in Japan. BMC Med Educ. (2014) 14:239. doi: 10.1186/s12909-014-0239-4

63. Seki N, Kanazawa M, Komagamine Y, Mizutani K, Hosaka K, Komada W, et al. International dental education course for clinical expertise at Tokyo medical and dental university graduate school. J Med Dental Sci. (2018) 65:123–30.

64. Seminario AL, Chen B, Liu J, Seymour B. Integrating global health within dental education: inter-university collaboration for scaling up a pilot curriculum. Ann Glob Health. 86: 113. doi: 10.5334/aogh.3024

65. Seymour B, Shick E, Chaffee BW, Benzian H. Going global: toward competency-based best practices for global health in dental education. J Dental Educ. (2017) 81:707–15. doi: 10.21815/JDE.016.034

66. Seymour B, Barrow J, Kalenderian E. Results from a new global oral health course: a case study at one dental school. J Dental Educ. (2013) 77:1245–51. doi: 10.1002/j.0022-0337.2013.77.10.tb05598.x

67. Seymour B, Benzian H, Kalenderian E. Voluntourism and global health: preparing dental students for responsible engagement in international programs. J Dental Educ. (2013) 77:1252–7. doi: 10.1002/j.0022-0337.2013.77.10.tb05599.x

68. Shanley DB. Convergence towards higher standards in international dental education. N Y State Dental J. (2004) 70:35–9.

69. Singh A, Purohit B. Global oral health course: perception among dental students in central India. Eur J Dent. (2012) 6:295–301. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-1698964

70. Sun J, Zheng J-W. [Current status of dental English education in China]. Shanghai Kou Qiang Yi Xue. (2016) 25:617–20.

71. Takehara S, Wright F, Kawaguchi Y, Ishida Y, Morio I, Tagami J. Characteristics of undergraduate dental students in Japan: English competency and willingness to study abroad. Int Dental J. (2016) 66:311–7. doi: 10.1111/idj.12244

72. Takehara S, Wright F, Kawaguchi Y, Morio I, Ishida Y, Tagami J. The impact of outbound exchange programs on Japanese dental students. J Med Dental Sci. (2018) 65:99–105.

73. Waterhouse PJ, Kowolik JE, Schrader SM, Howe D, Holmes RD. Transatlantic engagement: a novel dental educational exchange. Br Dental J. (2020) 228:637–42. doi: 10.1038/s41415-020-1478-x

74. Woodmansey KF, Rowland B, Horne S, Serio FG. International volunteer programs for dental students: results of 2009 and 2016 surveys of U.S. dental schools. J Dental Educ. (2017) 81:135–9. doi: 10.1002/j.0022-0337.2017.81.2.tb06258.x

75. Wynn LA, Krause DW, Kucine A, Trehan P, Goren AD, Colosi DC. Evolution of a humanitarian dental mission to Madagascar from 1999 to 2008. J Dental Educ. (2010) 74:289–96. doi: 10.1002/j.0022-0337.2010.74.3.tb04874.x

76. Yu A, Lambert RF, Alvarado JA, Guzman CAF, Seymour B. Integrating competency-based didactic and experiential global health learning for dental students: the global health learning helix model. J Dental Educ. (2020) 84:438–48. doi: 10.21815/JDE.019.186

77. Patel US, Tonni I, Gadbury-Amyot C, Van der Vleuten CPM, Escudier M. Assessment in a global context: an international perspective on dental education. Eur J Dental Educ. (2018) 22(Suppl. 1):21–7. doi: 10.1111/eje.12343

78. Ivanoff CS, Luan DM, Hottel TL, Andonov B, Ricci Volpato LE, Kumar RR, et al. An international survey of female dental students' perceptions about gender bias and sexual misconduct at four dental schools. J Dental Educ. (2018) 82:1022–35. doi: 10.21815/JDE.018.105

79. Rodis OMM, Matsumura S, Kariya N, Nishimura M, Yoshida T. Undergraduate dental English education in Japanese dental schools. J Dental Educ. (2013) 77:656–63. doi: 10.1002/j.0022-0337.2013.77.5.tb05516.x

80. Forsyth C, Irving M, Short S, Tennant M, Gilroy J. Students don't know what they don't know: dental and oral health students' perspectives on developing cultural competence regarding indigenous peoples. J Dental Educ. (2019) 83:679–86. doi: 10.21815/JDE.019.078

81. Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O'Brien K, Colquhoun H, Kastner M, et al. A scoping review on the conduct and reporting of scoping reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. (2016) 16:15. doi: 10.1186/s12874-016-0116-4

82. Hénard F, Diamond L, Roseveare D. Approaches to Internationalisation and Their Implications for Strategic Management and Institutional Practice - OECD Higher Education Programme IMHE. Available online at: http://www.oecd.org/education/imhe/Approaches%20to%20internationalisation%20-%20final%20-%20web.pdf. Education OH, editor2012.

83. McKinley DW, Williams SR, Norcini JJ, Anderson MB. International exchange programs and U.S. medical schools. Acad Med. (2008) 83(10 Suppl.):S53–7. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318183e351

84. Pannu V, Thompson AL, Pannu DS, Collins MA. Education for foreign-trained dentists in the United States: currently available findings and need for further research. J Dental Educ. (2013) 77:1521–4. doi: 10.1002/j.0022-0337.2013.77.11.tb05629.x

85. Custodi A, Deegan C, Fimmen C, Gordon A, McLaughlin K, Phylactopoulos A, et al. Six Pillars for Rebuilding International Higher Education. Univeristy World News (2020).

86. Wu A, Maddula V, Kieff MR, Kunzel C. An online program to improve international collaboration, intercultural skills, and research knowledge. J Dental Educ. (2020) 85:1–4. doi: 10.1002/jdd.12455

87. Van Der Wende M. Internationalising the curriculum in dutch higher education: an international comparative perspective. J Stud Int Educ. (1997) 1:53–72. doi: 10.1177/102831539700100204

88. Wu A, Leask B, Noel G, de Wit H. It is Time for the internationalization of medical education to be at home and accessible for all. Acad Med. (2021) 96:e22. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000004201

89. Ballard P. Nursing abroad offers interesting, educational, and sometimes unusual opportunities. ONS News. (1998) 13: 4–5.

90. Giuliani M, Frambach J, Broadhurst M, Papadakos J, Fazelad R, Driessen E, et al. A critical review of representation in the development of global oncology curricula and the influence of neocolonialism. BMC Med Educ. (2020) 20:93. doi: 10.1186/s12909-020-1989-9

91. Giuliani M, Martimianakis MAT, Broadhurst M, Papadakos J, Fazelzad R, Driessen EW, et al. Motivations for and challenges in the development of global medical curricula: a scoping review. Acad Med. (2021) 96:449–59. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003383

92. Stoltenberg M, Spence D, Daubman BR, Greaves N, Edwards R, Bromfield B, et al. The central role of provider training in implementing resource-stratified guidelines for palliative care in low-income and middle-income countries: lessons from the Jamaica Cancer Care and Research Institute in the Caribbean and Universidad Católica in Latin America. Cancer. (2020) 126(Suppl. 10):2448–57. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32857

93. Fung A, Hamilton E, Du Plessis E, Askin N, Avery L, Crockett M. Training programs to improve identification of sick newborns and care-seeking from a health facility in low- and middle-income countries: a scoping review. BMC Pregn Childb. (2021) 21:831. doi: 10.1186/s12884-021-04240-3

94. Chuenjitwongsa S, Bullock A, Oliver RG. Culture and its influences on dental education. Eur J Dental Educ. (2018) 22:57–66. doi: 10.1111/eje.12244

95. Wang YH, Zhao Q, Tan Z. Current differences in dental education between Chinese and Western models. Eur J Dental Educ. (2017) 21:e43–9. doi: 10.1111/eje.12216

96. Duong VA, Chua CSK. English as a symbol of internationalization in higher education: a case study of Vietnam. Higher Educ Res Dev. (2016) 35:669–83. doi: 10.1080/07294360.2015.1137876

Keywords: internationalization of dental education, dental global health, review, students, public health

Citation: Wu A, Shamim A, Rahhal Z, Kieff M, Lalla E, Torre L, Zubiaurre Bitzer L and Kunzel C (2022) A Scoping Review of Internationalization of Dental Education—Identifying Formats and Motivations in Dental Education. Front. Dent. Med. 3:847417. doi: 10.3389/fdmed.2022.847417

Received: 02 January 2022; Accepted: 11 April 2022;

Published: 23 June 2022.

Edited by:

Antonio Carlos Pereira, Universidade Estadual de Campinas, BrazilReviewed by:

Joško Viskić, University of Zagreb, CroatiaRita Kasa, Nazarbayev University, Kazakhstan

Copyright © 2022 Wu, Shamim, Rahhal, Kieff, Lalla, Torre, Zubiaurre Bitzer and Kunzel. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Anette Wu, YXcyMzQyQGN1bWMuY29sdW1iaWEuZWR1

Anette Wu

Anette Wu Abrar Shamim

Abrar Shamim Zacharie Rahhal2

Zacharie Rahhal2 Evanthia Lalla

Evanthia Lalla