- FSRC (a Part of phamax), Bangalore, India

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is a primary concern in India affecting approximately five million women each year. Existing literature indicate that prediabetes and diabetes affect approximately six million births in India alone, of which 90% are due to GDM. Studies reveal that there is no consensus among physicians and health-care providers in India regarding management of GDM prepartum and postpartum despite available guidelines. Also, there is no consensus among physicians as to when a woman should undergo oral glucose tolerance test after delivery. This clearly shows that management of GDM is challenging and controversial in India due to conflicting guidelines and treatment protocols, despite availability of straightforward protocols for screening and management. Also, a collaborative approach remains a key for GDM management, as patient compliance and proper educational interventions promote better pregnancy outcomes. Management of GDM plays a pivotal role, as women with GDM have an increased chance of developing diabetes mellitus 5–10 years after pregnancy. Also, children born in GDM pregnancies face an increased risk for obesity and type 2 diabetes. The cornerstone for the management of GDM is glycemic control and quality nutritional intake. GDM management is complex in India, and existing challenges are multifactorial. However, there are little published data outlining these challenges. This review gives an account of some of the key challenges from self-management and health-care provider perspective. The recommendations in this review provide insights for building a more structured model for GDM care in India. This research has several practical applications. First, it points out to reaching a consensus on approaches for screening, diagnosis, and treatment of care across clinical practices in the nation that can aid in overcoming certain challenges observed. Second, it highlights the importance to build capacities and capabilities, especially in resource-limited settings. Health education among pregnant women remains a priority to resolve issues related to self-management. More broadly, further research, specifically qualitative is vital to determine forthcoming challenges with respect to patients, caregivers, providers, and policy makers and to provide solutions fitted to practice setting and demographic background.

Background

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) affects a significant proportion of pregnant women worldwide. GDM occurs when a woman’s pancreatic function is not sufficient to overcome the diabetogenic environment of pregnancy and causes high blood glucose levels due to the body’s extra demand for insulin (1). A variety of factors like age, diet, obesity, ethnicity, family history, history of GDM in previous pregnancy, macrosomia, essential hypertension or pregnancy-related hypertension, history of spontaneous abortions, and unexplained stillbirths cause an increased risk of glucose intolerance in pregnant women (2, 3). Globally, the prevalence of GDM varies widely depending on the population studied and the diagnostic test employed by researchers. Research suggests that GDM occurs in 2–10% of all pregnancies depending on the populations studied (4). In 2013, hyperglycemia in pregnancy was evident in approximately 17% of all live births across the world (5). Women with GDM have a 40–60% chance of developing diabetes mellitus over 5–10 years after pregnancy (6). Also, children born in GDM pregnancies face an increased risk for obesity and type 2 diabetes (7). Although GDM-associated mortality is rare, maternal and fetal mortality can occur when glucose levels are poorly controlled (8).

In India alone, GDM affects five million women each year (9). The Women in India with Gestational Diabetes Mellitus Strategy (WINGS) program, jointly conducted by the International Diabetes Federation (IDF), the Madras Diabetes Research Foundation, and the Abbott Fund, highlighted that prediabetes and diabetes affect approximately six million births in India alone, of which 90% are due to GDM (10). Hence, as per the WINGS study, only half of these women were tested postpartum for GDM, and there was no consensus among physicians as to when a woman should undergo oral glucose tolerance test after delivery despite available guidelines (10). This shows that the management of GDM is still challenging and controversial with conflicting guidelines and treatment protocols, despite availability of straightforward protocols for screening and management in the general population (10, 11). Also, effective communication among physicians, patients, and primary care providers is essential for GDM management, as patient compliance and proper educational interventions promote better pregnancy outcomes (12, 13). The cornerstone for the management of GDM is glycemic control and quality nutritional intake. However, GDM patients who fail to control their glucose levels through lifestyle modifications may require insulin. The national list of essential medicines in India includes insulin, which is considered as the gold standard for glycemic control during pregnancy (14). Therefore, it is affordable and easily accessible at the primary, secondary, and tertiary levels of health care in India. Nonetheless, there is no consensus on when to initiate insulin therapy for GDM in India (15). Research suggests that interventions such as self-management are effective in improving glycemic control, lowering health-care costs, and improving the quality of life in patients with diabetes (16, 17). However, the specific challenges in the effective self-management of GDM are not fully established, particularly among women with GDM in India, adding woes to already muddled provider management.

Existing studies show some of the challenges, knowledge gaps, and approach to GDM care. But, inefficiencies in establishing these challenges contribute to suboptimal patient outcomes (10, 13). Therefore, to confront the impediments in GDM management, it is also essential to understand the solutions that exist. The goal of this study was to review the available literature to establish the challenges and potential opportunities for improving GDM care in India and provide recommendations for the same.

Methodology

The literature review focused on identifying the existing gaps and challenges in GDM management in India. The researchers identified studies that evaluated challenges in self-management and provider management of GDM in India. The researchers collected data through an extensive literature review process to present the consolidated information. First, key search terms like “Gestational diabetes,” “Gestational diabetes mellitus,” “GDM,” “epidemiology,” “challenges,” “barriers,” “management,” “screening,” “diagnosis,” “treatment,” “patient education,” “patient-centered care,” “recommendations,” “solutions,” and “India” were defined. Data were extracted using the search terms from diverse fields like health policies, obstetrics care, diabetes management, health-care access, health services research, and guidelines. The researchers then conducted iterative searches in electronic databases like Medline, PubMed, Cochrane Library, and references of selected articles to find relevant material on GDM in India. Since the subject demanded a thorough and systematic search, the data sources were not only limited to articles published in journals but also included gray literature. The sources for gray literature were as follows:

• Physician forums

• Institutional repositories like archives in hospital websites

• Physician association websites

• Popular Internet search engines

• Others (blogs, newsletters, and forums)

The search strategy was broad and sensitive to include as many relevant articles through subsequent manual screening. Again, the reference lists of relevant reviews and articles were thoroughly reviewed to ensure all important studies were covered. A thematic analysis approach was used to analyze the data retrieved in this review. The key challenges were segregated into categories that had similar ideas, concepts, or themes. The findings were then presented and discussed in detail.

Results

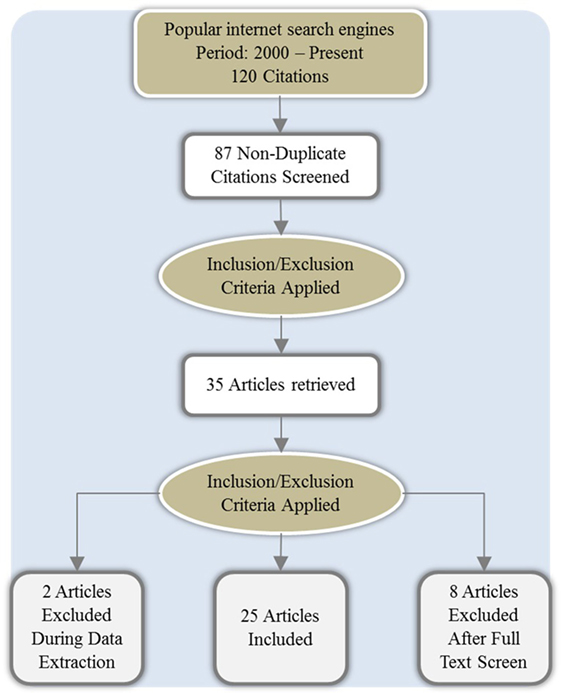

The researchers retrieved 87 articles from the initial search. Subsequently, the process of abstract sifting yielded 35 relevant articles that described GDM, its management, challenges, and other related information. The common reason for exclusion was non-relevance. Of these shortlisted articles, 25 citations met the inclusion criteria and were reviewed further (Figure 1).

Characteristics of the Studies Included

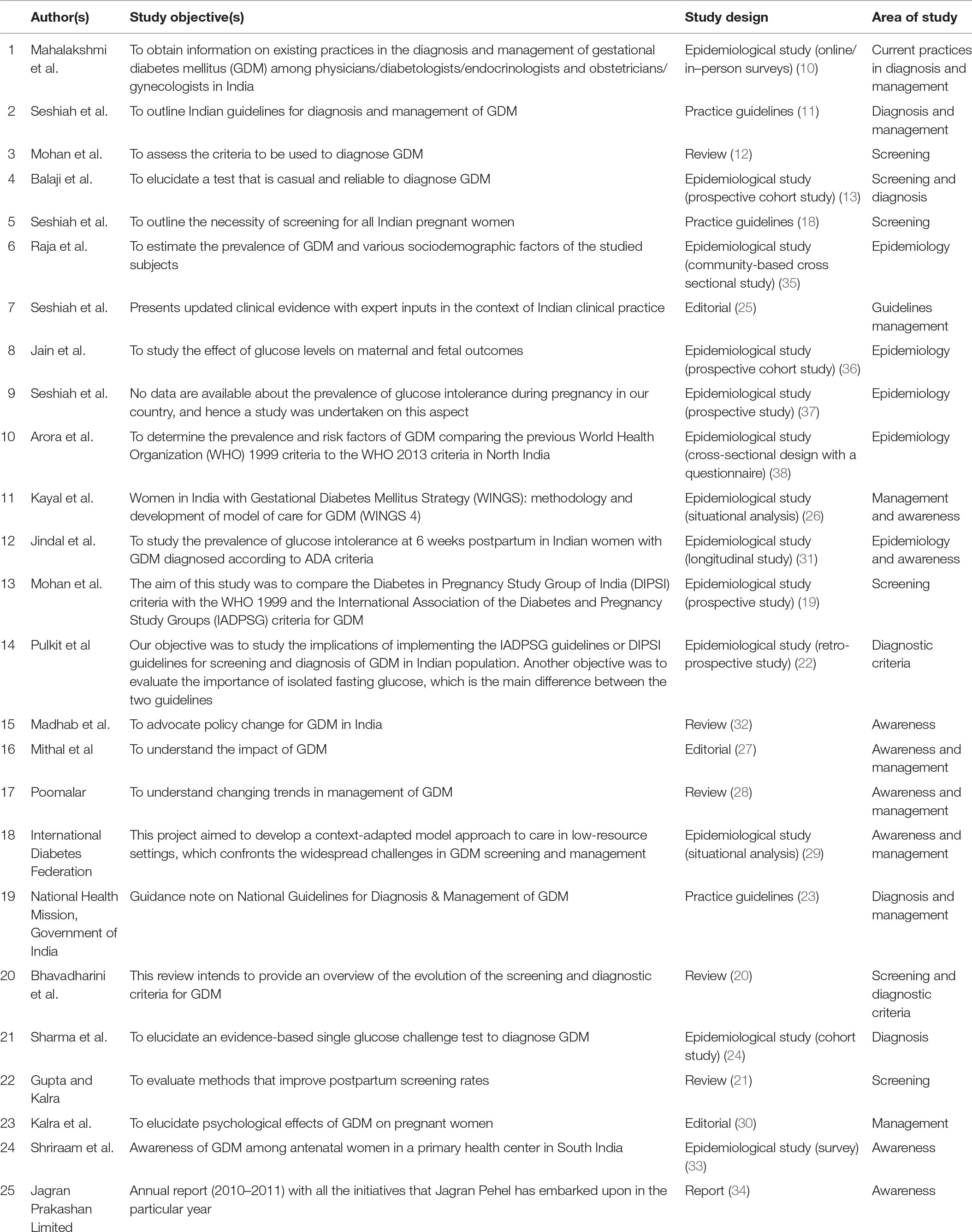

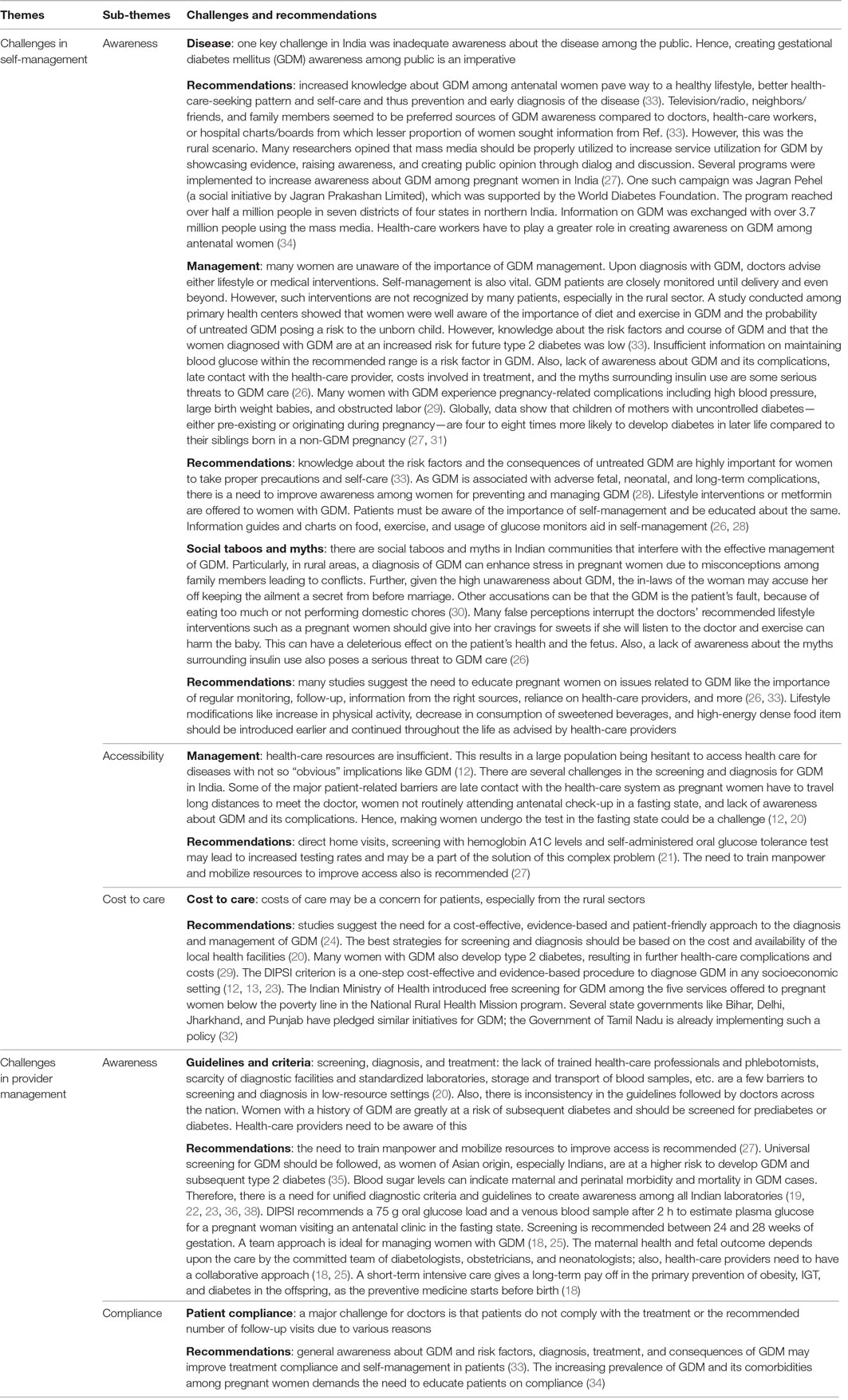

We analyzed 25 studies for this review. Among the 25 studies on GDM, 6 (12, 13, 18–21) were on screening, 7 (10, 11, 13, 20, 22–24) on diagnosis, 9 (10, 11, 23, 25–30) on management, 8 (26–29, 31–34) on awareness, and 5 (31, 35–38) on epidemiology. The increase in the total number of studies is due to the single studies that focused on more than one topic. Of the 25, 8 studies (12, 20, 21, 25, 27, 28, 30, 32) were literature reviews/editorials, 13 (10, 13, 19, 22, 26, 31, 35–38) epidemiological studies and surveys, and 4 (11, 18, 23, 34) reports/practice guidelines. The characteristics of these studies are also listed in Table 1.

Overall, three studies furnished data on self-monitoring of glucose levels and regulation of diet and exercise, adherence to medications, and periodic follow-up with the health-care provider. Similarly, 12 studies discussed GDM awareness among patients, management guidelines (prepartum to postpartum), patient compliance, and the need for educational and behavioral counseling. The data from 13 studies highlighted GDM care in India and discussed cultural tailoring of interventions, inconsistencies in screening, diagnosis and management guidelines across practices, individualized assessment and reassessment, and use of treatment algorithms by various health-care providers.

Analysis

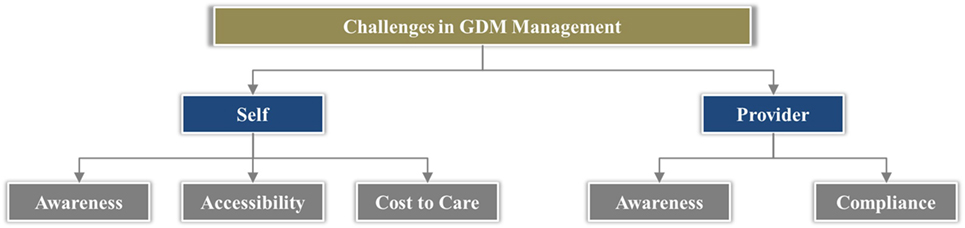

We analyzed data from these studies and categorized the challenges under two key themes covering the vital aspects of GDM care (Figure 2):

• Challenges in self-management

• Challenges in provider management

In addition, we provided recommendations for the outlined challenges based on relevant information extracted from these studies (Table 2).

Discussion

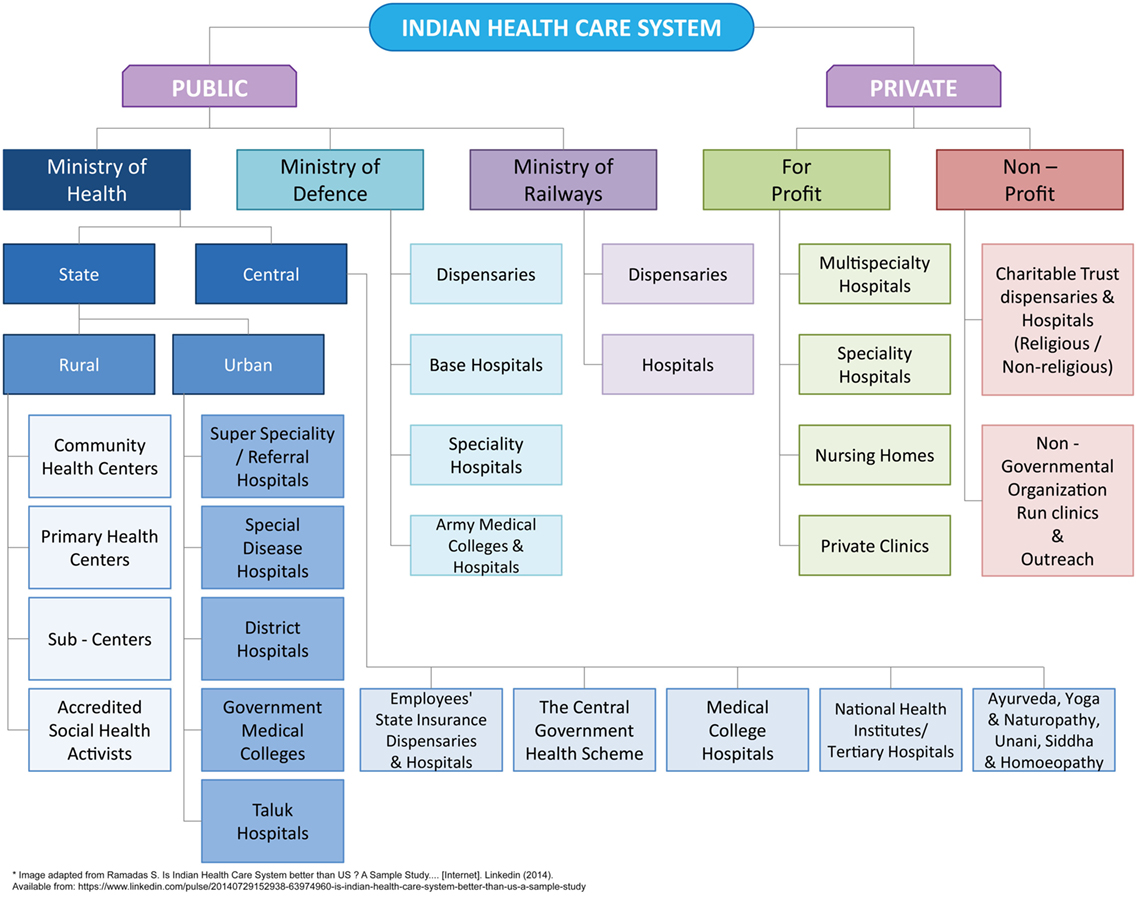

Before expounding the challenges and recommendations to GDM care, it is necessary to acquaint with the health-care delivery system in India.

Overview of Health System in India

Health-care system in India is categorized into two major sectors: public and private (Figure 3). The public health-care system chiefly includes secondary and tertiary care institutions in key cities and primary health-care centers in rural areas (39). On the other hand, the private sector provides majority of care through secondary, tertiary, and quaternary institutions with a major focus in tier I and tier II cities (39). Thus, the health-care infrastructure in urban and rural India is not evenly distributed and not at proximity, mostly in case of rural areas. Although, health-care services in the public sector are offered free of charge to all citizens, people often end up with high out-of-pocket expenditures because they often prefer services from private health care due to quality of care (40). Further, the health-care costs vary within the private sector based on the facilities and care offered, leading to issues related to affordability. On the whole, the total expenditure for health in India was 4.7% of GDP in 2014 of which public and out-of-pocket health expenses were 30 and 62.4%, respectively (41).

Apart from public and private health-care providers, non-profit organizations and non-governmental organizations also play a pivotal role for GDM-related advocacy. Currently, organizations, both national and international, such as IDF, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, Jagran Pehel, Women and Children First, Public Health Foundation of India, and others work toward promoting maternal and child health (9, 42–45). Another coalition in India that strives toward the same goal is the reproductive, maternal, newborn, child, and adolescent health (RMNCH+A) coalition, which is led by Save the Children India under the support of the Government (46). The coalition includes central and state government agencies, academia, research and training institutes, health-care professional associations, local bodies (Panchayats and Nagarpalikas), non-governmental organizations, civil society organizations, faith-based organizations, media, corporate organizations, bilateral and multilateral donors, and United Nations agencies (46). RMNCH+A aims to work more effectively in collaboration with multiple stakeholders to enhance joint action and accountability and to support the implementation of national commitments and policies (46). In 2005, a global alliance “The Partnership for Maternal, Newborn & Child Health” of more than 700 organizations in 77 countries representing the sexual, reproductive, maternal, newborn, child, and adolescent health communities, as well as health influencing sectors, was established (47). This partnership provides a platform for organizations in India to align objectives, strategies, and resources and to achieve consensus on interventions to improve maternal, newborn, child, and adolescent health (47).

To establish the existing challenges and recommendations for GDM care in India, the study researchers performed a narrative review using available literature on GDM in India. The key challenges identified during this review with regard to self-management and provider management included awareness, accessibility, compliance issues, and cultural context of care. The study researchers discussed the identified challenges and suggested recommendations based on the findings from the literature. Also, the researchers have provided additional recommendations in context of the findings after reviewing the most recent guideline documents and several international publications to suggest the best practices for GDM management.

Challenges in Self-Management

Some major challenges in the self-management of GDM were social taboos, cultural habits, GDM awareness, adherence, lack of patient motivation, screening costs, and transportation to nearest centers. Many of these challenges do not require adequate resources, but simple policy changes to improve GDM awareness. In India, the growing concern of family and friends for a pregnant woman and her baby is a major factor. Almost everyone within the family has an opinion. This can confuse and complicate the pregnant woman’s decisions to follow the health-care professional’s advice. The lack of information in communities and sometimes cultural perspectives are barriers to GDM care. Myths like “exercise harms the baby” and “pregnant mothers must consume food for two” cause negative strongholds in pregnant women, preventing them from following the instructions of their health-care professionals to exercise and adhere to a certain diet. Some patients are even reluctant to ask questions, suggesting poor interaction with the health-care providers leading to misconceptions (48, 49). Hence, many women remain sedentary during pregnancy because of these perceived barriers. Many women crave certain food items during pregnancy, and the temptation for food that is not necessarily nutritious, especially carbohydrates, is a major obstacle to adherence (48, 49). Although studies suggest that exercise is good in pregnant women, in reality, compliance to diet, exercise, and medications is a major challenge to care in GDM patients, given one’s cultural habits. There is a need to increase awareness among patients on the importance of diet, exercise, and medication while educating them on myths and health facts (48, 49).

The lack of awareness on GDM among patients is a major hurdle to its successful management. Majority of patients know little about blood glucose monitoring and adherence to treatment. This affects the treatment process and benefits. The limited knowledge on dietary issues and disease management causes malnutrition for both the mother and the fetus due to poor glucose control (49). Therefore, it is vital to educate patients about the disease, its complications, management strategies, and the importance of adherence. Previous research also suggests that information is crucial for patient adherence to treatment and self-management of the disease (48). However, the sources of information must be reliable. At all times, health-care providers are the greatest source of valid, reliable, and comprehensive information on GDM and its management.

Although pregnant women try to meet their nutritional needs and are careful about their own health, they disregard the importance of medicine. Studies show that GDM patients often encountered fear and emotional disturbances when informed about the consequences of the disease (48, 49). So, educating them on the importance of medicine and adhering to dietary recommendations improves their medicine intake and makes them more likely to embrace a healthier routine (49, 50).

Adding to the disease burden, the costs associated with GDM management are a barrier for pregnant women seeking consultation with the doctor and antenatal care. In India, many patients do not have health insurance and everything is out of pocket for major health services during pregnancy. Equipment such as glucometers and related supplies, medications, and diet modifications cause financial burdens. Low income, limited availability of public health centers at close proximity, and periodic travel to hospital for follow-ups also add to the financial burden of pregnant women in rural areas. Thus, there is a need to increase access to health-care services to reduce GDM burden in India.

Challenges in Provider Management

Some of the major challenges encountered in provider management were getting pregnant women to visit in a fasting state, getting blood samples, lack of trained phlebotomists, and standardized laboratories for blood glucose estimations, conflicting guidelines across practices and patient compliance (12). Screening should be made mandatory for all pregnant women due to the high prevalence of GDM among Indian women. The GDM status should be a part of a physician’s routine history assessment, irrespective of the pregnancy or parity, as GDM is a precursor for type 2 diabetes (51). Therefore, early screening and diagnosis can prevent obesity, impaired glucose tolerance, and diabetes in the progenies and mothers (52).

Most researchers shared the same opinion that GDM screening is widely deliberated, more specifically on selective versus universal screening, timing of testing, methods, and the diagnostic criteria. Some of the controversies surrounding this subject remain unresolved (53). First, getting a pregnant woman to undergo a GDM screening in a fasting state is challenging, particularly in a country like India. Second, multiple screening tests to diagnose GDM coupled with factors such as low awareness, less accessibility, and low affordability are a concern in resource-limited settings. Therefore, the World Health Organization 1999 criteria, which require only a single sample in comparison to the three samples required by the International Association of the Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Groups (IADPSG) criteria and four samples required by the Carpenter and Coustan criteria, became very popular in India initially (54). In 2014, the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare had developed technical and operational guidelines for identification and management of GDM in India. The national guidelines for diagnosis and management of GDM recommend a single-step procedure using 75 g oral glucose in a fasting or a non-fasting state and measuring plasma glucose 2 h postingestion (23). This one-step procedure to diagnose GDM is preferred as it is simple, economical, and feasible. Although the criteria for screening and diagnosis are established, uncertainty still exists on the execution methods.

Screening remains vital to prevent GDM-related complications during perinatal period and delivery. Evidence suggests that universal screening improves pregnancy outcomes compared to selective screening (55). Many guidelines recommend universal screening, while others exempt patients categorized as low-risk groups. Low-risk patients are younger than 25 years, have normal body weight, have no first-degree relatives with diabetes, show no history of abnormal glucose metabolism or poor obstetric outcomes, and are not from an ethnic group with a high diabetes prevalence (Hispanic American, Native American, Asian American, African American, and Pacific Islander) (56). Contrarily, a few researchers argue that selective screening based on the clinical characteristics of a pregnant woman facilitates efficient screening for GDM (57). The risk for GDM varies among different pregnant women based on marked obesity, previous history of GDM, glycosuria, or family history of diabetes. Nonetheless, all pregnant women should be screened for GDM during their first antenatal visit (51). Although few experts object to the screening of low-risk patients routinely, research suggests that non-screening omits approximately 4% patients with GDM (58). Universal screening for GDM detects more cases and improves maternal and neonatal prognosis compared to selective screening (59). The US Preventive Services Task Force (2014) also recommends that all asymptomatic pregnant women be screened for GDM after 24 weeks of gestation (53).

Many International medical associations like the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the American Endocrinology Society, the Canadian Diabetes Association, Australian Diabetes Association, and the Diabetes in Pregnancy Study Group of India also endorse that screening for GDM should be universal. Although certain organizations like the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence recommend selective screening, even they agree that Asians, especially Indians, are a high-risk ethnic group (12). Therefore, Indian pregnant women should be universally screened at their first registration. The benefits of universal screening cannot be ignored in the long term given the high prevalence of GDM across India in spite of the increased screening costs for the government and individuals (51, 59).

Gestational diabetes mellitus patients ideally need counseling about the disease from the time of diagnosis. The education should cover recommended diet, exercise, treatment, self-care, and monitoring. There is also a need to train them efficiently to use monitoring equipment for self-management. The patients’ family members should also be educated on emotional and psychological support, the needs associated with GDM, and general pregnancy care. It is vital to highlight the importance of antenatal care and that GDM management requires a holistic support system. The first line of management for women with GDM is medical nutrition therapy (MNT) or dietary modification, followed by physical activity and monitoring of blood glucose levels. MNT reduces pregnancy and perinatal complications and brings glycemic control (8). A study by Jovanovic-Peterson et al. showed that exercise (arm ergometer training) coupled with dietary modifications improved glycemic control compared to dietary modifications alone (60). Home-based exercise training improved capillary glucose profile in women with gestational diabetes. A study by Halse et al. showed that home-based cycling is effective in maintaining daily postprandial normal glycemic levels in women with diet-controlled GDM. Further, the researchers noticed that the compliance to the supervised exercise training was good, and capillary glucose concentration reduced in response to each cycling session despite high consumption of dietary carbohydrates (61). Exercise proved to be beneficial in GDM patients, but there are no guidelines for the same until recently. In 2015, Padayachee and Coombes drafted the first guidelines on exercise for GDM management (62).

Further, in women prescribed with insulin, hospitalization proved to be effective in achieving treatment compliance to regulate glucose levels (48). Although it is not possible to hospitalize every GDM women to regulate glucose levels in resource-limited settings, it can be inferred that managing GDM requires a collaborative approach. Well-trained professionals play a crucial role in screening, diagnosis, and treatment. A team approach is ideal to manage women with GDM usually comprising an obstetrician, diabetologist/endocrinologist, health education provider, dietitian, and neonatologists/pediatrician (18).

Intensive monitoring, diet, and insulin are the cornerstones of GDM management. Until there is absolute evidence that ignoring maternal hyperglycemia is acceptable when the fetal growth patterns appear normal on the ultrasonogram, it is prudent to achieve and maintain normal glycemic levels in every pregnancy complicated by GDM. The maternal health and fetal outcome depend on the care by a committed team of health-care professionals. A short-term intensive care gives long-term benefits in preventing obesity, impaired glucose tolerance and diabetes in the offspring, as the preventive medicine starts before birth. The future solutions offered by physicians should focus on tangible and simple ways to better monitor patients and standardize care across practice.

Conclusion

In India, GDM management is complex, and existing challenges are multifactorial. This review established some of the key challenges from self-management and health-care provider perspective. The recommendations provided in the literature and by this study researchers pave way for building a more structured model for GDM care in India. Reaching a consensus on approaches for screening, diagnosis, and treatment of care across clinical practices in the nation can aid in overcoming certain challenges observed. It is important to build capacities and capabilities, especially in resource-limited settings. Health education among pregnant women remains a priority to resolve issues related to self-management. To conclude, periodic research, specifically qualitative, can elicit forthcoming challenges with respect to patients, caregivers, providers, and policy makers and provide solutions tailored to practice setting and demographic background.

Author Contributions

SM, GB, AG, BZ, and AP declare that we have made substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work or data collection, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work; drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content; final approval of the version to be published; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The reviewer RM and handling Editor declared their shared affiliation, and the handling Editor states that the process nevertheless met the standards of a fair and objective review.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the support of Mr. Anand Patil for sponsoring the publishing fee, reviewing the content, and providing essential insights.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. It was self-funded by one of the author AP.

References

1. Charles RB, Beckmann WH, Laube D, Ling F, Smith R. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 7th ed. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins (2014).

2. Cheung NW, Wasmer G, Al-Ali J. Risk factors for gestational diabetes among Asian women. Diabetes Care (2001) 24(5):955–6. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.5.955

3. Cypryk K, Szymczak W, Czupryniak L, Sobczak M, Lewinski A. Gestational diabetes mellitus – an analysis of risk factors. Endokrynol Pol (2008) 59(5):393–7.

4. Hunt KJ, Schuller KL. The increasing prevalence of diabetes in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am (2007) 34(2):173–99, vii. doi:10.1016/j.ogc.2007.03.002

5. International Dibetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas. Online International Diabetes Federation (2015). Available from: http://www.diabetesatlas.org/

6. Gabbe SG, Landon MB, Warren-Boulton E, Fradkin J. Promoting health after gestational diabetes: a National Diabetes Education Program call to action. Obstet Gynecol (2012) 119(1):171–6. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182393208

7. National Institute of Health (NIH). Diabetes Overview. USA: NIH Publication (2017). Available from: https://www.niddk.nih.gov/

8. Mpondo BC, Ernest A, Dee HE. Gestational diabetes mellitus: challenges in diagnosis and management. J Diabetes Metab Disord (2015) 14:42. doi:10.1186/s40200-015-0169-7

9. International Dibetes Federation. Diabetes in Pregnancy: Protecting Maternal Health. (2011). Available from: https://www.idf.org/sites/default/files/Policy_Briefing_DiabetesInPregancy.pdf

10. Mahalakshmi MM, Bhavadharini B, Maheswari K, Anjana RM, Jebarani S, Ninov L, et al. Current practices in the diagnosis and management of gestational diabetes mellitus in India (WINGS-5). Indian J Endocrinol Metab (2016) 20(3):364–8. doi:10.4103/2230-8210.180001

11. Seshiah VSB, Das AK, Balaji V, Shah S, Banerjee S, Muruganathan A, et al. Diagnosis and management of gestational diabetes mellitus: Indian guidelines. editors. Munjal YP, Sharma SK, Agarwal AK, Gupta P, Kamath SA, Nadkar MY, et al. API Textbook of Medicine. Mumbai: JayPee Brothers (2013). p. 201–4.

12. Mohan V, Usha S, Uma R. Screening for gestational diabetes in India: where do we stand? J Postgrad Med (2015) 61(3):151–4. doi:10.4103/0022-3859.159302

13. Balaji V, Balaji M, Anjalakshi C, Cynthia A, Arthi T, Seshiah V. Diagnosis of gestational diabetes mellitus in Asian-Indian women. Indian J Endocrinol Metab (2011) 15(3):187–90. doi:10.4103/2230-8210.83403

14. India MoH. National List of Essential Medicines 2015. (2017). Available from: http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/documents/s23088en/s23088en.pdf

15. Gilmartin AB, Ural SH, Repke JT. Gestational diabetes mellitus. Rev Obstet Gynecol (2008) 1(3):129–34.

16. Pimouguet C, Le Goff M, Thiebaut R, Dartigues JF, Helmer C. Effectiveness of disease-management programs for improving diabetes care: a meta-analysis. Can Med Assoc J (2011) 183(2):E115–27. doi:10.1503/cmaj.091786

17. Li R, Zhang P, Barker LE, Chowdhury FM, Zhang X. Cost-effectiveness of interventions to prevent and control diabetes mellitus: a systematic review. Diabetes Care (2010) 33(8):1872–94. doi:10.2337/dc10-0843

18. Seshiah V, Das AK, Balaji V, Joshi SR, Parikh MN, Gupta S, et al. Gestational diabetes mellitus – guidelines. J Assoc Physicians India (2006) 54:622–8.

19. Mohan V, Mahalakshmi MM, Bhavadharini B, Maheswari K, Kalaiyarasi G, Anjana RM, et al. Comparison of screening for gestational diabetes mellitus by oral glucose tolerance tests done in the non-fasting (random) and fasting states. Acta Diabetol (2014) 51(6):1007–13. doi:10.1007/s00592-014-0660-5

20. Bhavadharini B, Uma R, Saravanan P, Mohan V. Screening and diagnosis of gestational diabetes mellitus – relevance to low and middle income countries. Clin Diabetes Endocrinol (2016) 2(13):1–8. doi:10.1186/s40842-016-0031-y

21. Gupta Y, Kalra S. Improving postpartum screening rates. Arch Gynecol Obstet (2014) 289(6):1159–60. doi:10.1007/s00404-014-3213-9

22. Pulkit Vij SJ, Gupta SK, Aneja A, Mathur R, Waghdhare S, Panda M. Comparison of DIPSI and IADPSG criteria for diagnosis of GDM: a study in a north Indian tertiary care center. Int J Diabetes Dev Ctries (2015) 35(3):285–8. doi:10.1007/s13410-014-0244-5

23. National Health Mission. National Guidelines for Diagnosis & Management of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. New Delhi: Government of India in collaboration with UNICEF (2014). Available from: http://nrhm.gov.in/images/pdf/programmes/maternal-health/guidelines/National_Guidelines_for_Diagnosis_&_Management_of_Gestational_Diabetes_Mellitus.pdf

24. Sharma K, Wahi P, Gupta A, Jandial K, Bhagat R, Gupta R, et al. Single glucose challenge test procedure for diagnosis of gestational diabetes mellitus: a Jammu cohort study. J Assoc Physicians India (2013) 61(8):558–9.

25. Seshiah V, Banerjee S, Balaji V, Muruganathan A, Das AK, Diabetes Consensus G. Consensus evidence-based guidelines for management of gestational diabetes mellitus in India. J Assoc Physicians India (2014) 62(7 Suppl):55–62.

26. Kayal A, Mohan V, Malanda B, Anjana RM, Bhavadharini B, Mahalakshmi MM, et al. Women in India with Gestational Diabetes Mellitus Strategy (WINGS): methodology and development of model of care for gestational diabetes mellitus (WINGS 4). Indian J Endocrinol Metab (2016) 20(5):707–15. doi:10.4103/2230-8210.189230

27. Mithal A, Bansal B, Kalra S. Gestational diabetes in India: science and society. Indian J Endocrinol Metab (2015) 19(6):701–4. doi:10.4103/2230-8210.164031

28. Poomalar GK. Changing trends in management of gestational diabetes mellitus. World J Diabetes (2015) 6(2):284–95. doi:10.4239/wjd.v6.i2.284

29. International Dibetes Federation. Women in India with GDM Strategy (WINGS). Brussels: International Diabetes Federation (2016). Available from: http://www.idf.org/wings

30. Kalra S, Baruah MP, Gupta Y, Kalra B. Gestational diabetes: an onomastic opportunity. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol (2013) 1(2):91. doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(13)70104-9

31. Jindal R, Siddiqui MA, Gupta N, Wangnoo SK. Prevalence of glucose intolerance at 6 weeks postpartum in Indian women with gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Metab Syndr (2015) 9(3):143–6. doi:10.1016/j.dsx.2015.04.016

32. Madhab A, Prasad VM, Kapur A. Gestational diabetes mellitus: advocating for policy change in India. Int J Gynaecol Obstet (2011) 115(Suppl 1):S41–4. doi:10.1016/S0020-7292(11)60012-X

33. Shriraam V, Rani MA, Sathiyasekaran BW, Mahadevan S. Awareness of gestational diabetes mellitus among antenatal women in a primary health center in South India. Indian J Endocrinol Metab (2013) 17(1):146–8. doi:10.4103/2230-8210.107861

34. Jagran Pehel. Jagran Pehel – Annual Report. Delhi: Jagran Pehel (2011). Available from: http://jagranpehel.com/FileAccess/Annual%20Report%202010-11.pdf

35. Raja MW, Baba TA, Hanga AJ, Bilquees S, Rasheed S, Haq IU, et al. A study to estimate the prevalence of gestational diabetes mellites in an urban block of Kashmir valley (North India). Int J Med Sci Public Health (2014) 3(2):191–5. doi:10.5455/ijmsph.2013.211120131

36. Jain R, Davey S, Davey A, Raghav SK, Singh JV. Can the management of blood sugar levels in gestational diabetes mellitus cases be an indicator of maternal and fetal outcomes? The results of a prospective cohort study from India. J Family Community Med (2016) 23(2):94–9. doi:10.4103/2230-8229.181002

37. Seshiah V, Balaji V, Balaji MS, Sanjeevi CB, Green A. Gestational diabetes mellitus in India. J Assoc Physicians India (2004) 52:707–11.

38. Arora GP, Thaman RG, Prasad RB, Almgren P, Brons C, Groop LC, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of gestational diabetes in Punjab, North India: results from a population screening program. Eur J Endocrinol (2015) 173(2):257–67. doi:10.1530/EJE-14-0428

39. India Brand Equity Foundation. Healthcare Industry in India: India Brand Equity Foundation. (2017). Available from: http://www.ibef.org/industry/healthcare-india.aspx

40. Bhatia M. The Indian Health Care System: The Commonwealth Fund. (2017). Available from: http://international.commonwealthfund.org/countries/india/

41. The World Bank Group. Health Expenditure – India: The World Bank Group. (2016). Available from: http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.XPD.PUBL

42. Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. What We Do? Maternal, Newborn & Child Health Strategy Overview: Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. (2017). Available from: http://www.gatesfoundation.org/What-We-Do/Global-Development/Maternal-Newborn-and-Child-Health

43. Jagran Pehel. Pehel: Jagran Pehel (2012). Available from: http://www.jagranpehel.com/ContentPages/GeneralInfo/Introduction.aspx

44. Women & Chilren First (UK). India [2017]. Women & Children First (UK) (2017). Available from: https://www.womenandchildrenfirst.org.uk/archive-india

45. Public Health Foundation of India. Health Promotion: Public Health Foundation of India. (2014). Available from: https://www.phfi.org/our-activities/health-promotion

46. World Health Organization. Strengthening National Advocacy Coalitions for Improved Women’s and Children’s Health: The Partnership for Maternal, Newborn and Child Health. (2013). Available from: http://www.who.int/pmnch/knowledge/publications/cso_report/en/

47. World Health Organization. The Partnership for Maternal, Newborn & Child Health. World Health Organization (2017). Available from: http://www.who.int/pmnch/about/en/

48. Ghaffari F, Salsali M, Rahnavard Z, Parvizy S. Compliance with treatment regimen in women with gestational diabetes: living with fear. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res (2014) 19(7 Suppl 1):S103–11.

49. Carolan M, Gill GK, Steele C. Women’s experiences of factors that facilitate or inhibit gestational diabetes self-management. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth (2012) 12:99. doi:10.1186/1471-2393-12-99

50. Doran FM. An Exploratory Study of Physical Activity and Lifestyle Change Associated with Pregnancy and Gestational Diabetes Mellitus and the Implications for Health Promotion Interventions. Lismore: Southern Cross University (2010).

51. Expert Committee on the Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus. Classification of Diabetes M. Report of the expert committee on the diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care (2003) 26(Suppl 1):S5–20. doi:10.2337/diacare.26.2007.S5

52. Crowther CA, Hiller JE, Moss JR, McPhee AJ, Jeffries WS, Robinson JS, et al. Effect of treatment of gestational diabetes mellitus on pregnancy outcomes. N Engl J Med (2005) 352(24):2477–86. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa042973

53. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for gestational diabetes mellitus: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med (2008) 148(10).

54. Alberti KG, Zimmet PZ. Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complications. Part 1: diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus provisional report of a WHO consultation. Diabet Med (1998) 15(7):539–53. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-9136(199807)15:7<539:AID-DIA668>3.0.CO;2-S

55. Marquette GP, Klein VR, Niebyl JR. Efficacy of screening for gestational diabetes. Am J Perinatol (1985) 2(1):7–9. doi:10.1055/s-2007-999901

56. Dietrich ML, Dolnicek TF, Rayburn WF. Gestational diabetes screening in a private, midwestern American population. Am J Obstet Gynecol (1987) 156(6):1403–8. doi:10.1016/0002-9378(87)90007-X

57. Naylor CD, Sermer M, Chen E, Farine D. Selective screening for gestational diabetes mellitus. Toronto Trihospital Gestational Diabetes Project Investigators. N Engl J Med (1997) 337(22):1591–6. doi:10.1056/NEJM199711273372204

58. Williams CB, Iqbal S, Zawacki CM, Yu D, Brown MB, Herman WH. Effect of selective screening for gestational diabetes. Diabetes Care (1999) 22(3):418–21. doi:10.2337/diacare.22.3.418

59. Cosson E, Benchimol M, Carbillon L, Pharisien I, Pariès J, Valensi P, et al. Universal rather than selective screening for gestational diabetes mellitus may improve fetal outcomes. Diabetes Metab (2006) 32(2):140–6. doi:10.1016/S1262-3636(07)70260-4

60. Jovanovic-Peterson L, Durak EP, Peterson CM. Randomized trial of diet versus diet plus cardiovascular conditioning on glucose levels in gestational diabetes. Am J Obstet Gynecol (1989) 161(2):415–9. doi:10.1016/0002-9378(89)90534-6

61. Halse RE, Wallman KE, Newnham JP, Guelfi KJ. Home-based exercise training improves capillary glucose profile in women with gestational diabetes. Med Sci Sports Exerc (2014) 46(9):1702–9. doi:10.1249/MSS.0000000000000302

Keywords: gestational diabetes mellitus, India, health care, challenges, recommendations, gestational diabetes mellitus management

Citation: Morampudi S, Balasubramanian G, Gowda A, Zomorodi B and Patil AS (2017) The Challenges and Recommendations for Gestational Diabetes Mellitus Care in India: A Review. Front. Endocrinol. 8:56. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2017.00056

Received: 23 January 2017; Accepted: 06 March 2017;

Published: 24 March 2017

Edited by:

Anne E. Sumner, National Institutes of Health (NIH), USAReviewed by:

Jean-Pierre Chanoine, University of British Columbia, CanadaRanganath Muniyappa, National Institutes of Health (NIH), USA

Copyright: © 2017 Morampudi, Balasubramanian, Gowda, Zomorodi and Patil. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Gayathri Balasubramanian, Z2F5YXRocmkuYmFsYXN1YnJhbWFuaWFuQGZzLXJlc2VhcmNoY2VudGVyLmNvbQ==

Suman Morampudi

Suman Morampudi Gayathri Balasubramanian

Gayathri Balasubramanian Arun Gowda

Arun Gowda Behsad Zomorodi

Behsad Zomorodi Anand Shanthanagowd Patil

Anand Shanthanagowd Patil