- 1Department of Pharmacology, Shanxi Medical University, Taiyuan, China

- 2Key Laboratory of Cellular Physiology, Ministry of Education, Shanxi Medical University, Taiyuan, China

- 3Department of Endocrinology, The First Hospital of Shanxi Medical University, Shanxi Medical University, Taiyuan, China

Dopamine (DA) has a vital role in the central nervous system and also modulates lipid and glucose metabolism. The present study aimed to investigate the effect of dopamine on insulin secretion and the underlying mechanisms in rat pancreatic β-cells. Data from the radioimmunoassay indicated that dopamine inhibited insulin secretion in a glucose- and dose-dependent manner. This inhibitory effect of dopamine was mediated mainly by D2-like receptors, but not D1-like receptors. Whole-cell patch-clamp recordings showed that dopamine decreased voltage-dependent Ca2+ channel currents, which could be reversed by inhibition of the D2-like receptor. Dopamine increased voltage-dependent potassium (KV) channel currents and shortened action potential duration, which was antagonized by inhibition of D2-like receptors. Further experiments showed that D2-like receptor activation by quinpirole increased KV channel currents. In addition, using calcium imaging techniques, we found that dopamine reduced intracellular Ca2+ concentration, which was also reversed by D2-like receptor antagonists. Similarly, quinpirole was found to decrease intracellular Ca2+ levels. Taken together, these findings demonstrate that dopamine inhibits insulin secretion mainly by acting on D2-like receptors, inhibiting Ca2+ channels, and activating Kv channels. This process results in shortened action potential duration and decreased intracellular Ca2+ levels in β-cells. This work offers new insights into a glucose-dependent mechanism whereby dopamine regulates insulin secretion.

Introduction

Insulin production and utilization are essential for maintaining glucose homeostasis. In pancreatic β-cells, high glucose concentrations increase the ATP/ADP ratio, which leads to the closure of ATP-sensitive potassium channels and depolarization of membrane potential. The membrane potential depolarization activates voltage-dependent calcium channels and then promotes Ca2+ influx as well as insulin release. However, it is worth noting that voltage-dependent potassium (KV) channels are also activated during the procedure, which suppresses Ca2+ influx and insulin release (1, 2).

Dopamine is the most abundant catecholamine neurotransmitter in the brain, which modulates neuronal activity to perform various functions in the central nervous system (3). Studies have shown that dopamine can also be synthesized and released in peripheral tissues such as the pancreas, kidneys, and lungs to exert non-neural functions (4–6). Dopamine signals through the G protein-coupled dopamine receptors (DRs) to affect biological activities. Five different DR subtypes (D1R–D5R) have been identified to date, with different receptors being grouped based on their intrinsic properties into either the D1-like (D1R and D5R) or D2-like (D2R–D4R) subgroups (7, 8).

Clinical studies have reported that patients with Parkinson's disease who were treated with the long-term dopamine precursor L-dopa had a significant reduction in glucose tolerance and even developed type 2 diabetes (9). In recent years, dopamine has been proposed to be important in regulating glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (10, 11). However, the characteristic effect of dopamine on insulin secretion and the underlying electrophysiological mechanism have not been extensively studied.

In the current study, we focused on the acute effects of dopamine on insulin secretion and its influence on ion channels in pancreatic β-cells. The results demonstrated that dopamine suppresses insulin secretion in a glucose-dependent manner by binding to D2-like receptors, inhibiting Ca2+ channels, activating Kv channels, shortening action potential duration, and decreasing intracellular calcium levels.

Materials and Methods

Reagents

The dopamine, D1-like receptor inhibitor (SCH23390, 10 μM), D2-like receptor antagonist (eticlopride, 10 μM), D1-like receptor agonist (SKF38393, 10 μM), and D2-like receptor agonist (quinpirole, 10 μM) used in this study were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, USA.

Animals

Male Wistar rats (Beijing Vital River Laboratory Animal Technology) weighing 200–260 g were housed in an environment with suitable temperature (25 ± 2°C), humidity (55–60%), and 12 h of light–dark cycles. The animals had free access to food and tap water. All experiments involving animals described below were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Shanxi Medical University.

Isolation and Culture of Rat Pancreatic Islets and Islet Cells

After rats were euthanized, the prepared collagenase P (1 mg/mL, Roche, Indianapolis, USA) was injected into the pancreas via the common bile duct. After the pancreas was digested for 11 min, the isolated islets were obtained by density gradient centrifugation with Histopaque™-1077 (Sigma-Aldrich, USA). Pancreatic β-cells were separated from islets by Dispase II (Roche, Indianapolis, USA) digestion. Isolated islets and islet β-cells were cultured in HyClone RPMI 1640 medium (Hyclone, Beijing, China) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 mg/mL streptomycin, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 11.1 mM glucose at 37°C in 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere.

Insulin Secretion Assay

Rat pancreatic islets (5 islets/vial) were pre-incubated in Krebs Ringer bicarbonate-HEPES (KRBH) buffer with 2.8 mM glucose (Solarbio, Beijing, China) for 30 min. Subsequently, islets were incubated in KRBH buffer containing different concentrations of glucose and drugs for 30 min. The concentrations of insulin in the supernatant were determined by an Iodine [125I] Insulin Radioimmunoassay Kit (North Biological Technology Research Institute of Beijing). The islets in each vial were lysed with 70% acid-ethanol solution [Ethanol/water/HCl (vol/vol) 150:47:3] for measurement of total cellular insulin concentration. The KRBH buffer contained: 128.8 mM NaCl; 4.8 mM KCl; 2.5 mM CaCl2; 1.2 mM KH2PO4; 1.2 mM MgSO4; 5 mM NaHCO3; 10 mM HEPES; and 2% BSA (Solarboi, Beijing, China) at pH 7.4.

Patch-Clamp Experiments

Islet cells were cultured on coverslips coated with cell-adherent reagent (Applygen Technologies Inc., Beijing, China) for 24 h (12). The whole-cell patch-clamp was carried out using an EPC-10 amplifier and the PULSE software (HEKA Electronik, Lambrecht, GER). The resistances of patch pipettes filled with pipette solution ranged between 4 and 7 MΩ by employing Narishige PP-830 micropipette puller (Narishige Co, Tokyo, Japan) and MICROFORGEMF-200 (World Precision Instruments Inc, USA). β-cells were confirmed based on their capacitance values > 7 pF (13).

The Ca2+ currents were elicited by 50 ms pulses from a holding potential of −70 mV to the test potentials ranging from −50 to 30 mV in 10 mV steps. We replaced Ca2+ with Ba2+ in the extracellular solution to eliminate calcium-dependent inactivation of voltage-gated calcium channels. The holding potential of −70 mV was applied to limit contamination by Na+ currents, the majority of which are inactivated at this holding potential. The intracellular solution consisted of 120 mM CsCl; 20 mM TEA (Tetraethylammonium chloride, Sigma-Aldrich, USA); 1 mM MgCl2; 0.05 mM EGTA; 10 mM HEPES; and 5 mM MgATP (pH 7.3 adjusted with CsOH). The extracellular solution was made of 100 mM NaCl; 20 mM TEA; 20 mM BaCl2; 4 mM CsCl; 1 mM MgCl2; 5 mM HEPES; and 3 mM glucose (pH 7.4 adjusted with NaOH).

In order to record voltage-dependent potassium (KV) channel currents, the cells were voltage-clamped at a holding potential of −70 mV and then shifted to the test potentials ranging from −70 to 80 mV (10 mV steps) within 400 ms. The intracellular solution included: 10 mM NaCl; 140 mM KCl; 10 mM HEPES; 0.05 mM EGTA; and 1 mM MgCl2 (pH 7.25 adjusted with KOH). The extracellular solution was composed of 141.9 mM NaCl; 5.6 mM KCl; 1.2 mM MgCl2; 11.1 mM glucose; and 5 mM HEPES (pH 7.4 with NaOH).

The action potentials of β-cells were elicited by 4 ms, 150 pA current injection in the current-clamp mode. Action potential duration was determined based on the difference of time from the initial action potential until the membrane potential returned to within 10 mV of the resting membrane potential, which was processed by PULSE software (14).

The Measurement of Intracellular Calcium Levels

Islet cells were cultured on coverslips coated by adhesion reagent for 3 h before experiments. Cells were incubated in KRBH buffer containing 2.8 mM glucose and 2 μM Fura-2 AM (Dojindo Laboratories, Japan) for 30 min at 37°C. Cells were then washed twice with the buffers supplemented with 2.8 mM glucose. Intracellular Ca2+ activity was monitored at excitation wavelength 340 and 380 nm, emission wavelength 510 nm by MetaFluor 7.8 (Molecular Devices, USA) software, and Olympus IX71 inverted microscope. The change in intracellular Ca2+ concentration was displayed by the ratio of fluorescence intensity (F340/F380). The ratio of fluorescence intensity (F/F0, where F is the average fluorescence intensity for 100 s after reaching a plateau under different treatments and F0 is the initial fluorescence intensity of 2.8 mM glucose) was used to compare intracellular Ca2+ levels under different treatments (15, 16).

Statistical Analysis

Data were presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis was done by parametric tests, Student's t-tests, or one-way ANOVAs in Sigmaplot (version 12.5). The post-hoc tests were done using the LSD-t test. P < 0.05 was considered a statistically significant difference.

Results

Dopamine Inhibits Insulin Secretion in a Dose- and Glucose-Dependent Manner

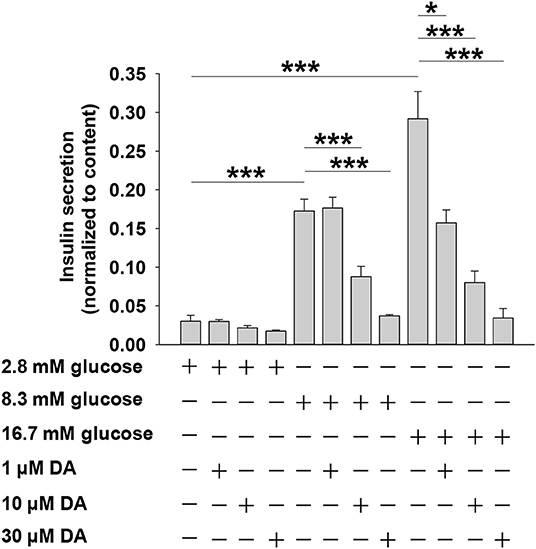

We first investigated how dopamine affects insulin secretion in rat pancreatic islets. As shown in Figure 1, when islets were incubated with 2.8 mM glucose, dopamine had no effect on insulin secretion regardless of concentration (0–30 μM). However, at higher glucose conditions (8.3 or 16.7 mM), dopamine dose-dependently inhibited insulin secretion (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Dopamine (DA) inhibits insulin secretion in a dose- and glucose-dependent manner. Rat islets (5/vial) were treated with different concentration of DA in the presence of 2.8, 8.3, or 16.7 mM glucose. The supernatant was collected to test for insulin secretion. The islets in each vial were lysed with 70% acid-ethanol solution [ethanol/water/HCl (vol/vol) 150:47:3] for measurement of total cellular insulin content. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM and compared by one-way ANOVA (n = 7 vials per group), *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001.

Dopamine Inhibits Insulin Secretion Mainly via D2-Like Receptors, Rather Than D1-Like Receptors

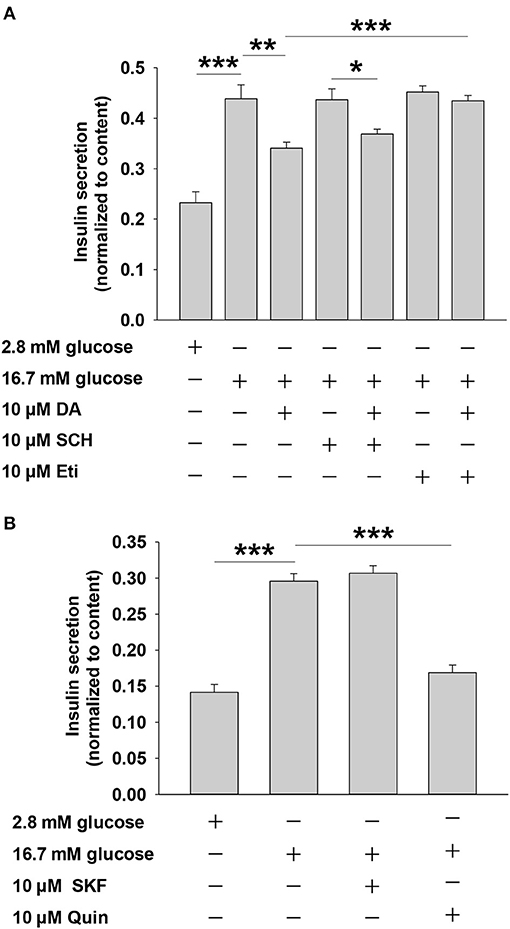

Dopamine exerts physiological effects through G protein-coupled receptors, including the D1-like receptor subfamily (D1 and D5) and the D2-like receptor subfamily (D2, D3, and D4) (8), which are expressed in rat islets (17). To investigate the relationship between dopamine receptors and dopamine-inhibited insulin secretion, we applied agonists or antagonists of the two dopamine receptor subfamilies. Eticlopride is a potent and selective D2-like receptor antagonist. Previous studies showed that eticlopride was more specific for D2-like receptors than pimozide or haloperidol (18). Quinpirole has been used as a selective D2-like receptor agonist in various experiments (17, 19). As shown in Figure 2A, the D2-like receptor antagonist eticlopride markedly blocked the effect of dopamine on insulin secretion, whereas SCH23390 (D1-like receptor inhibitor) had no influence on dopamine-inhibited insulin secretion in rat pancreatic islets. Furthermore, we found that the D2-like receptor agonist quinpirole decreased insulin secretion, while the D1-like receptor agonist SKF38393 had no effect on insulin secretion (Figure 2B). Together, these results indicate that D2-like receptors are the primary mediators of dopamine-inhibited insulin secretion from rat pancreatic islets.

Figure 2. Dopamine (DA) inhibits insulin secretion mainly via D2-like receptors, rather than D1-like receptors. (A) Effect of SCH 23390 (SCH, 10 μM) and eticlopride (Eti, 10 μM) on DA-inhibited insulin secretion. (B) Effect of SKF38393 (SKF, 10 μM) and quinpirole (Quin, 10 μM) on DA-inhibited insulin secretion. Rat islets (5/vial) were incubated under different conditions. Insulin was determined by Iodine [125I] Insulin Radioimmunoassay Kit. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM and compared by one-way ANOVA (n = 6 vials per group), *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. SCH 23390, D1-like receptor antagonist; eticlopride, D2-like receptor antagonist; SKF38393, D1-like receptor agonist; quinpirole, D2-like receptor agonist.

Dopamine Inhibits Voltage-Dependent Ca2+ Channel Through D2-Like Receptors

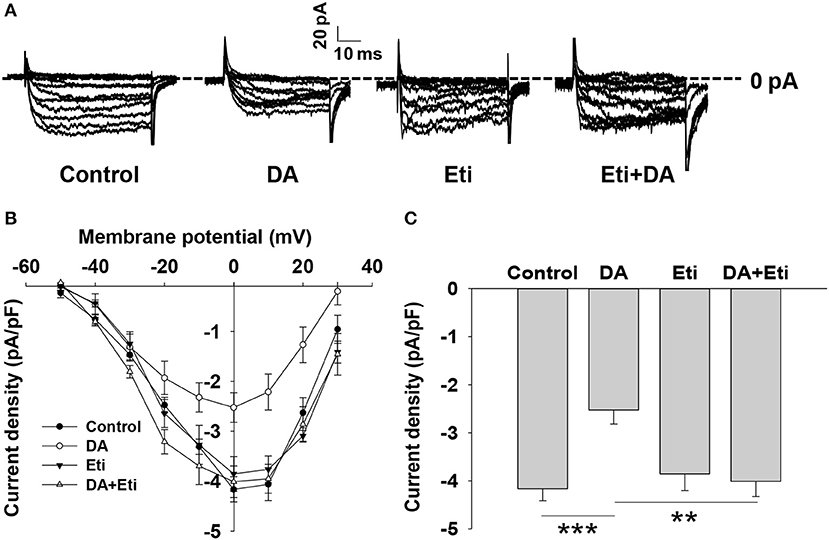

It is well established that voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels play an important role in glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (20, 21). We examined the effect of dopamine on Ca2+ channels. The inward Ca2+ currents were evoked by depolarizing pulses with whole-cell patch-clamp technology (Figure 3A). Compared to the control, dopamine prominently decreased voltage-dependent Ca2+ currents (Figures 3A–C). Since D2-like receptors are required for dopamine-inhibited insulin secretion, we further tested the role of D2-like receptors in dopamine-regulated Ca2+ channels. As shown, eticlopride itself had no effect on voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels. However, the inhibition of Ca2+ channels by dopamine was abolished in the presence of eticlopride (Figures 3A–C). These results indicate that dopamine-regulated Ca2+ channels are mediated by D2-like receptors.

Figure 3. Dopamine reduces voltage-dependent calcium channel currents. (A) Representative Ca2+ current traces recorded from different rat β-cells treated with dopamine (DA, 10 μM) in the presence or absence of eticlopride (Eti, 10 μM). (B) Current-voltage relationship curves obtained from the treated cells. (C) Summary of the mean current density of Ca2+ currents at 0 mV depolarization. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM and compared by one-way ANOVA. Pancreatic β-cells were confirmed based on their capacitance values >7 pF (n = 6 β-cells/group), **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

Dopamine Increases Voltage-Dependent Potassium (KV) Channel Currents via D2-Like Receptors

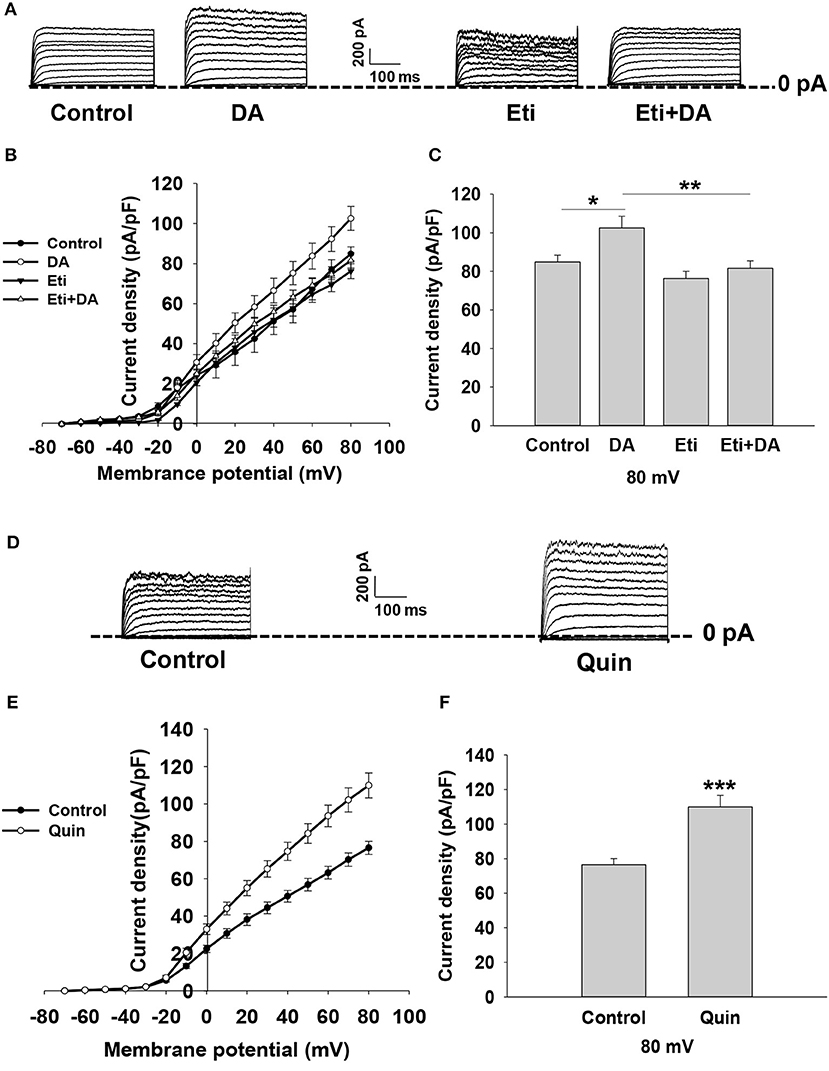

Kv channels have been shown to play an important role in modulating stimulus–secretion coupling in pancreatic β-cells (22). We next examined the influence of dopamine on Kv channels in rat β-cells. Outward K+ currents were evoked by depolarizing pulses from potentials of −70 to 80 mV in whole-cell voltage-clamp experiments (Figure 4A). The data showed that dopamine significantly enhanced Kv currents compared to controls (Figures 4A–C), suggesting that Kv channels are involved in dopamine-inhibited insulin secretion.

Figure 4. Dopamine increases KV currents via D2-like receptors in rat β cells. KV currents were recorded from a holding potential of −70 to 80 mV in 10 mV increments. (A) Representative whole-cell current traces recorded when different cells were treated with dopamine (DA, 10 μM) in the presence or absence of eticlopride (Eti, 10 μM). (B,E) Current-voltage relationship curves of Kv channels under different treatments. (C,F) Summary of the mean current density of Kv channels recorded at 80 mV depolarization. (D) Representative whole-cell current traces recorded in the presence or absence of quinpirole (Quin, 10 μM). Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM and compared by one-way ANOVA and Student's t-test. Pancreatic β-cells were confirmed based on their capacitance values >7 pF (n = 6 β-cells/group), *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

To test whether dopamine-regulated Kv currents are mediated by D2-like receptors, pancreatic β-cells were treated with D2-like receptor antagonist eticlopride in the presence or absence of dopamine. We found that eticlopride alone did not influence Kv channels. However, eticlopride remarkably abolished the effect of dopamine on Kv channel currents (Figures 4A–C). We further applied D2-like receptor agonist quinpirole to verify the effect of D2-like receptors on Kv channels. As shown in Figures 4D–F, quinpirole significantly increased KV currents compared to controls. Thus, these data indicate that dopamine increases Kv currents via D2-like receptors.

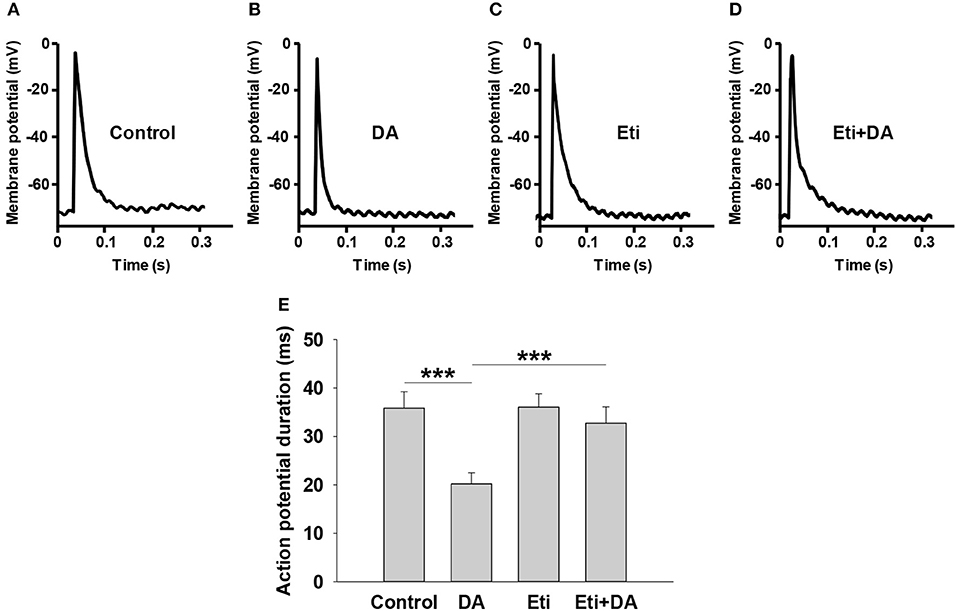

Dopamine Shortens Action Potential Duration (APD) via D2-Like Receptors

Glucose-stimulated insulin secretion is triggered by a series of electrical activity from pancreatic β-cells (23). Among them, the activation of Kv channels repolarizes action potentials to limit insulin secretion (24). We performed whole-cell current-clamp experiments to assess if dopamine affects action potential duration in rat pancreatic β-cells. As depicted in Figures 5A,B,E, dopamine notably shortened action potential durations compared to controls (P < 0.001).

Figure 5. Dopamine shortens action potential duration via D2-like receptors. Action potentials were elicited from pancreatic β-cells in different groups by applying 4 ms, 150 pA current injection. The indicated drugs were added to the cell chamber with bath solution before patch-clamping until the experiment was finished. (A–D) Representative action potential waveforms obtained under different conditions as indicated. (E) Summary of the mean action potential durations. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM and compared by one-way ANOVA (n = 6 β-cells/group), ***P < 0.001. Dopamine (DA, 10 μM); Eticlopride (Eti, 10 μM).

We next explored the relationship between D2-like receptors and dopamine-regulated action potential duration (APD). As shown in Figures 5A,C,E, the D2-like receptor antagonist eticlopride had no influence on APD by itself. However, the effect of dopamine on APD was significantly abolished by eticlopride (Figures 5B,D,E), suggesting that D2-like receptors mediate dopamine-regulated APD.

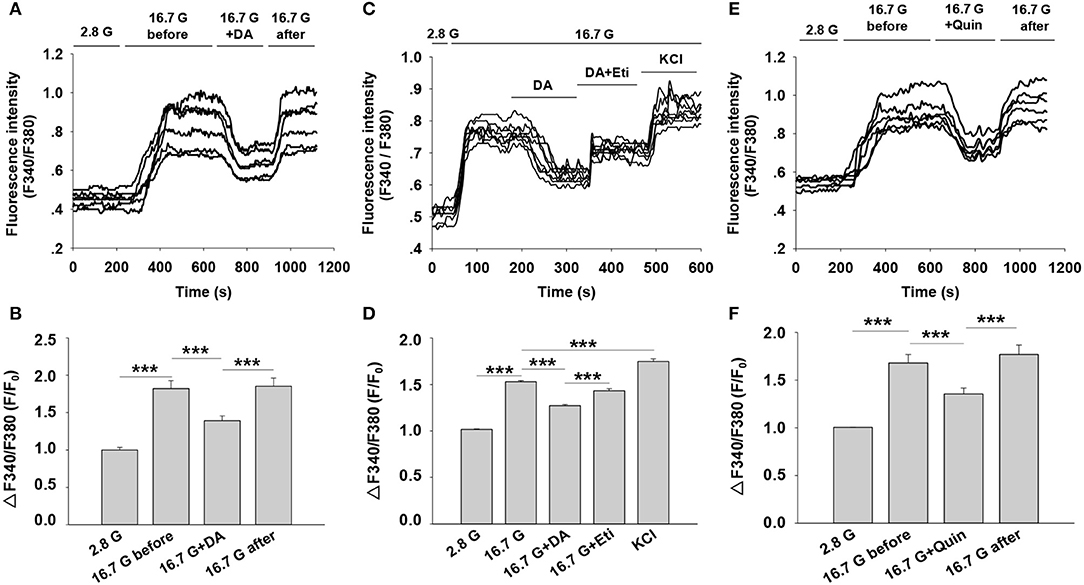

Dopamine Decreases Intracellular Calcium ([Ca2+]i) Level Through D2-Like Receptors in Rat Pancreatic β-Cells

Intracellular Ca2+ plays a pivotal role in insulin secretion. Glucose-induced electrical activity is accompanied by changes of intracellular Ca2+ level in pancreatic β-cells (23). We therefore examined the influence of dopamine on [Ca2+]i level by applying Fura-2 AM dye. The change in [Ca2+]i was reflected by the ratio of fluorescence intensity (F340/F380) in β-cells. As shown in Figures 6A,B, 16.7 mM of glucose significantly increased fluorescence intensity compared to 2.8 mM of glucose. However, dopamine markedly lowered fluorescence intensity under 16.7 mM glucose conditions, demonstrating that dopamine decreased [Ca2+]i level in rat pancreatic β-cells.

Figure 6. Effect of dopamine on intracellular calcium ([Ca2+]i) level in rat pancreatic β-cells. [Ca2+]i level was determined based on the ratio of F340/F380. (A) Cells were perfused with dopamine (DA, 10 μM) in the presence of 16.7 mM glucose (16.7 G) (n = 6 β-cells/group). (C) Cells were treated with dopamine (DA, 10 μM) in the presence or absence of eticlopride (Eti, 10 μM) (n = 8 β-cells/group). (E) Cells were perfused with quinpirole (Quin, 10 μM) in the presence of 16.7 mM glucose (n = 6 β-cells/group) (B,D,F). The mean of ΔF340/F380 (F/F0) under different treatments as indicated. F, average fluorescence intensity during 100 s after the fluorescence plateaued for different treatments; F0, baseline fluorescence at 2.8 mM glucose (2.8 G). Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM and compared by one-way ANOVA. ***P < 0.001.

To explore the influence of D2-like receptors on dopamine-regulated [Ca2+]i, we performed experiments with the D2-like receptors antagonist eticlopride. Figures 6C,D showed that the decreased fluorescence intensity induced by dopamine was counteracted by eticlopride. In addition, we found that the fluorescence intensity was also reduced by using the D2-like receptor agonist quinpirole under the 16.7 mM glucose condition (Figures 6E,F). These findings suggest that the action of dopamine on [Ca2+]i is mediated by D2-like receptors in rat pancreatic β-cells.

Discussion

Dopamine receptors have been detected in the islets of human, rat, mouse (25), and INS-1E β cells (17). In the present study, we found that dopamine and the D2-like receptor agonist quinpirole play similar roles in inhibiting insulin secretion from rat pancreatic islets, which is consistent with previous reports (17). Dopamine-inhibited insulin secretion was antagonized by the D2-like receptor blocker eticlopride. In addition, we found that applying the D1-like receptor agonist SKF38393 or the antagonist SCH 23390 had no significant effect on insulin secretion. These results demonstrate that dopamine inhibits insulin secretion mainly via D2-like receptors in rat pancreatic islets. Meanwhile, our data indicates that the characteristic of dopamine in regulating insulin is glucose-dependent, since dopamine exerts the inhibitory effect at high glucose concentrations (8.3 and 16.7 mM glucose) rather than at basal glucose concentration (2.8 mM glucose).

Dopamine influences ion channels such as voltage-gated K+, Na+, and Ca2+ channels in the central nervous system (26). In the large neuron, dopamine reduces the frequency of spontaneous action potentials and activates inward rectifier K+ channels (27). Moreover, dopamine decreases cytosolic Ca2+ concentration in rat lactotroph cells (28). Considering that insulin secretion from pancreatic β-cells is regulated principally by ion channels, we examined the potential electrophysiological mechanism of dopamine in regulating insulin secretion.

Our study showed that dopamine reduced voltage-dependent Ca2+ channel currents and increased Kv channel currents in β-cells via D2-like receptors. It is well-established that voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels are responsible for the generation of action potentials and serve as a positive regulator of insulin secretion (29). KV channels are important for the repolarization of action potentials and act as a negative regulator of insulin secretion (24). Our data reveals that dopamine significantly shortens action potential duration, which appears to be the consequence of Ca2+ channel inhibition and KV channel activation caused by dopamine.

Intracellular calcium ([Ca2+]i) is a key determinant of glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (30, 31). As expected, our calcium imaging results showed that dopamine reversibly decreased [Ca2+]i via D2-like receptors in rat pancreatic β-cells, which is consistent with the results of our secretion assay. Our study reveals that the reduction of [Ca2+]i is due to dopamine inhibition on Ca2+ channels. Furthermore, because activation of KV channels shortens action potential durations to limit total Ca2+ influx, we propose that the KV channel activation also contributes to the reduction of [Ca2+]i induced by dopamine.

Further, dopamine-regulated insulin secretion is found to be glucose-dependent, which could also be ascribed to the inhibition of Ca2+ channels and the activation of KV channels, because the Ca2+ channels and KV channels are only open in response to membrane depolarization under high glucose condition (32).

Studies have demonstrated that D2-like receptors are coupled to Gαi/o proteins, leading to inhibition of adenylyl cyclase (AC) and protein kinase A (PKA) activity in neurons (33). Forskolin, an activator of cAMP, has been shown to antagonize the inhibitory effect of dopamine on insulin secretion (34). Furthermore, we and others have shown that AC and the downstream cAMP/PKA play an important role in glucose-stimulated insulin secretion, including a voltage-dependent ion channel mechanism (14, 35, 36). Given these findings, we speculate that the AC/cAMP/PKA signaling pathway might be involved in the regulation of dopamine on insulin release.

In the present study, Ca2+ channel current measurements and action potential recordings were carried out in non-physiological conditions, which helps identify their roles in the regulation of insulin secretion by dopamine. However, exploring the downstream signaling pathways and identifying the involvement of the master receptor of the D2-like family is also essential for a better understanding of the influence of dopamine on insulin secretion. A recent study using transgenic knockout mice reveals that both D2R and D3R mediate the inhibitory effect of dopamine on insulin secretion (37). Likewise, efforts are expected to further discern the metabolic roles and clinical implications of the dopaminergic system in pancreatic islets in future research.

In summary, these results collectively suggest that dopamine inhibition on insulin secretion is associated with the activation of D2-like receptors followed by inhibition of voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels and activation of KV channels, which shortens glucose-stimulated action potentials and limits Ca2+ entry, leading to the suppression of insulin secretion. As a neurotransmitter in the central nervous system, dopamine has been shown to be important in the regulation of glucose homeostasis (38). Our findings provide new insight into dopamine-mediated regulation of insulin secretion in primary rat islets, which also explains the cause of impaired insulin secretion and impaired glucose tolerance in Parkinson's disease patients treated with long-term dopaminergic drugs.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

The animal study was reviewed and approved by The Animal Care and Use Committee of Shanxi Medical University.

Author Contributions

All authors participated in the experimental design, data analysis, and interpretation. ML, LR, XZ, and YD performed the research and developed methods. YZ, ML, XZ, and LR designed the study. YZ, YL, and ML wrote the manuscript. TL, ZL, XY, LC, LY, YF, and YL critically read the manuscript and participated in fruitful discussions.

Funding

This work was supported by NSFC (81670710; 81770776; 81973378), Cultivate Scientific Research Excellence Programs of Higher Education Institutions in Shanxi (2019KJ022), and Advanced Programs of Shanxi for the Returned Overseas Chinese Scholars (2016-97). This research project was supported by Shanxi Scholarship Council of China (2017-053), FSKSC and 1331KSC, Department of Education Innovation Project in Shanxi Province (2019BY078), and Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Program for College Students in Shanxi Province (2019165).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1. Jacobson DA, Philipson LH. Action potentials and insulin secretion: new insights into the role of Kv channels. Diabetes Obesity Metab. (2007) 9:89–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2007.00784.x

2. Henquin JC. Regulation of insulin secretion: a matter of phase control and amplitude modulation. Diabetologia. (2009) 52:739–51. doi: 10.1007/s00125-009-1314-y

3. Callier S, Snapyan M, Le Crom S, Prou D, Vincent JD, Vernier P. Evolution and cell biology of dopamine receptors in vertebrates. Biol Cell. (2003) 95:489–502. doi: 10.1016/S0248-4900(03)00089-3

4. Harris RC, Zhang MZ. Dopamine, the kidney, and hypertension. Curr Hypertens Rep. (2012) 14:138–43. doi: 10.1007/s11906-012-0253-z

5. Adir Y, Azzam ZS, Lecuona E, Leal S, Pesce L, Dumasius V, et al. Augmentation of endogenous dopamine production increases lung liquid clearance. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. (2004) 169:757–63. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200207-744OC

6. Mezey E, Eisenhofer G, Harta G, Hansson S, Gould L, Hunyady B, et al. A novel nonneuronal catecholaminergic system: exocrine pancreas synthesizes and releases dopamine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (1996) 93:10377–82. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.19.10377

7. Vallone D, Picetti R, Borrelli E. Structure and function of dopamine receptors. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. (2000) 24:125–32. doi: 10.1016/S0149-7634(99)00063-9

8. Missale C, Nash SR, Robinson SW, Jaber M, Caron MG. Dopamine receptors: from structure to function. Physiol Rev. (1998) 78:189–225. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1998.78.1.189

9. Ahrén B, Lundquist I. Effects of L-dopa-induced dopamine accumulation on 45Ca2+ efflux and insulin secretion in isolated rat islets. Pharmacology. (1985) 30:71–82. doi: 10.1159/000138053

10. García-Tornadú I, Ornstein AM, Chamson-Reig A, Wheeler MB, Hill DJ, Arany E, et al. Disruption of the dopamine D2 receptor impairs insulin secretion and causes glucose intolerance. Endocrinology. (2010) 151:1441–50. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-0996

11. Caldwell B, Ustione A, Piston DW. Dopamine receptor signaling in MIN6 beta-cells revealed by fluorescence fluctuation spectroscopy. Biophys J. (2016) 111:609–18. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2016.06.026

12. Liu M, Yang X, Bai T, Liu Z, Liu T, Wang Y, et al. PACAP stimulates insulin secretion by PAC1 receptor and ion channels in beta-cells. Cell Signal. (2019) 61:48–56. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2019.05.006

13. Göpel S, Kanno T, Barg S, Galvanovskis J, Rorsman P. Voltage-gated and resting membrane currents recorded from B-cells in intact mouse pancreatic islets. J Physiol. (1999) 521(Pt 3):717–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.00717.x

14. Zhang Y, Ding Y, Zhong X, Guo Q, Wang H, Gao J, et al. Geniposide acutely stimulates insulin secretion in pancreatic beta-cells by regulating GLP-1 receptor/cAMP signaling and ion channels. Mol Cell Endocrinol. (2016) 430:89–96. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2016.04.020

15. Gao J, Zhong X, Ding Y, Bai T, Wang H, Wu H, et al. Inhibition of voltage-gated potassium channels mediates uncarboxylated osteocalcin-regulated insulin secretion in rat pancreatic β cells. Eur J Pharmacol. (2016) 777:41–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2016.02.060

16. Carneiro-Júnior MA, Quintão-Júnior JF, Drummond LR, Lavorato VN, Drummond FR, da Cunha DN, et al. The benefits of endurance training in cardiomyocyte function in hypertensive rats are reversed within four weeks of detraining. J Mol Cell Cardiol. (2013) 57:119–28. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2013.01.013

17. Rubí B, Ljubicic S, Pournourmohammadi S, Carobbio S, Armanet M, Bartley C, et al. Dopamine D2-like receptors are expressed in pancreatic beta cells and mediate inhibition of insulin secretion. J Biol Chem. (2005) 280:36824–32. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505560200

18. Koerber J, Goodman D, Barnes JL, Grimm JW. The dopamine D2 antagonist eticlopride accelerates extinction and delays reacquisition of food self-administration in rats. Behav Pharmacol. (2013) 24:633–9. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0000000000000002

19. Péczely L, Ollmann T, László K, Kovács A, Gálosi R, Kertes E, et al. Role of ventral pallidal D2 dopamine receptors in the consolidation of spatial memory. Behav Brain Res. (2016) 313:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2016.07.007

20. Schulla V RE, Feil R, Feil S, Franklin I, Gjinovci A, Jing XJ, et al. Impaired insulin secretion and glucose tolerance in beta cell-selective Ca (v) 1.2 Ca2+ channel null mice. EMBO J. (2014) 22:3844–54. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg389

21. Rorsman P, Ramracheya R, Rorsman NJ, Zhang Q. ATP-regulated potassium channels and voltage-gated calcium channels in pancreatic alpha and beta cells: similar functions but reciprocal effects on secretion. Diabetologia. (2014) 57:1749–61. doi: 10.1007/s00125-014-3279-8

22. MacDonald PE, Wheeler MB. Voltage-dependent K(+) channels in pancreatic beta cells: role, regulation and potential as therapeutic targets. Diabetologia. (2003) 46:1046–62. doi: 10.1007/s00125-003-1159-8

23. Rorsman P, Ashcroft FM. Pancreatic β-cell electrical activity and insulin secretion: of mice and men. Physiol Rev. (2018) 98:117–214. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00008.2017

24. MacDonald PE, Sewing S, Wang J, Joseph JW, Smukler SR, Sakellaropoulos G, et al. Inhibition of Kv2.1 voltage-dependent K+ channels in pancreatic beta-cells enhances glucose-dependent insulin secretion. J Biol Chem. (2002) 277:44938–45. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205532200

25. Tomé M, Moreira E, Pérez-Fígares JM, Jiménez AJ. Presence of D1- and D2-like dopamine receptors in the rat, mouse and bovine multiciliated ependyma. J Neural Trans. (2007) 114:983–94. doi: 10.1007/s00702-007-0666-z

26. Tritsch NX, Sabatini BL. Dopaminergic modulation of synaptic transmission in cortex and striatum. Neuron. (2012) 76:33–50. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.09.023

27. Uchida S, Akaike N, Nabekura J. Dopamine activates inward rectifier K+ channel in acutely dissociated rat substantia nigra neurones. Neuropharmacology. (2000) 39:191–201. doi: 10.1016/S0028-3908(99)00111-2

28. Malgaroli A, Vallar L, Elahi FR, Pozzan T, Spada A, Meldolesi J. Dopamine inhibits cytosolic Ca2+ increases in rat lactotroph cells. Evidence of a dual mechanism of action. J Biol Chem. (1987) 262:13920–7.

29. Rorsman P, Ashcroft FM, Trube G. Single Ca channel currents in mouse pancreatic B-cells. Pflugers Arch. (1988) 412:597–603. doi: 10.1007/BF00583760

30. Hellman B. The significance of calcium for glucose stimulation of insulin release. Endocrinology. (1975) 97:392–8. doi: 10.1210/endo-97-2-392

31. Kalwat MA, Cobb MH. Mechanisms of the amplifying pathway of insulin secretion in the beta cell. Pharmacol Ther. (2017) 179:17–30. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2017.05.003

32. Jacobson DA, Kuznetsov A, Lopez JP, Kash S, Ammälä CE, Philipson LH. Kv2.1 ablation alters glucose-induced islet electrical activity, enhancing insulin secretion. Cell Metab. (2007) 6:229–35. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.07.010

33. Klein MO BD, Cardoso AR, Hauser DN, Bittencourt JC, Correa RG. Dopamine: functions, signaling, and association with neurological diseases. Cell Mol Neurobiol. (2019) 39:31–59. doi: 10.1007/s10571-018-0632-3

34. Shankar E, Santhosh KT, Paulose CS. Dopaminergic regulation of glucose-induced insulin secretion through dopamine D2 receptors in the pancreatic islets in vitro. IUBMB Life. (2006) 58:157–63. doi: 10.1080/15216540600687993

35. Vettorazzi JF, Ribeiro RA, Borck PC, Branco RC, Soriano S, Merino B, et al. The bile acid TUDCA increases glucose-induced insulin secretion via the cAMP/PKA pathway in pancreatic beta cells. Metab Clin Exp. (2016) 65:54–63. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2015.10.021

36. Tengholm A, Gylfe E. cAMP signalling in insulin and glucagon secretion. Diabetes Obesity Metab. (2017) 19(Suppl 1):42–53. doi: 10.1111/dom.12993

37. Farino ZJ, Morgenstern TJ, Maffei A, Quick M, De Solis AJ, Wiriyasermkul P, et al. New roles for dopamine D2 and D3 receptors in pancreatic beta cell insulin secretion. Mol Psychiatry. (2019). doi: 10.1038/s41380-018-0344-6

Keywords: dopamine, D2-like receptors, insulin secretion, KV channels, Ca2+ channels, β cells

Citation: Liu M, Ren L, Zhong X, Ding Y, Liu T, Liu Z, Yang X, Cui L, Yang L, Fan Y, Liu Y and Zhang Y (2020) D2-Like Receptors Mediate Dopamine-Inhibited Insulin Secretion via Ion Channels in Rat Pancreatic β-Cells. Front. Endocrinol. 11:152. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2020.00152

Received: 08 December 2019; Accepted: 04 March 2020;

Published: 07 April 2020.

Edited by:

Magalie A. Ravier, INSERM U1191 Institut de Génomique Fonctionnelle (IGF), FranceReviewed by:

Matthieu Raoux, Université de Bordeaux, FranceAmelia K. Linnemann, Indiana University, United States

Copyright © 2020 Liu, Ren, Zhong, Ding, Liu, Liu, Yang, Cui, Yang, Fan, Liu and Zhang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yunfeng Liu, bmVjdGFybGl1QDE2My5jb20=; Yi Zhang, eWl6aGFuZzMxM0AxNjMuY29t

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Mengmeng Liu1†

Mengmeng Liu1† Yunfeng Liu

Yunfeng Liu Yi Zhang

Yi Zhang