- 1Key Laboratory of Endocrinology of National Health Commission, Department of Endocrinology, Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Science and Peking Union Medical College, Beijing, China

- 2Department of General Surgery, Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Science and Peking Union Medical College, Beijing, China

Objective: Ectopic adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) syndrome (EAS) is a condition of hypercortisolism caused by non-pituitary tumors secreting ACTH. Appendiceal neuroendocrine tumor as a rare cause of ectopic ACTH syndrome was reported scarcely. We aimed to report a patient diagnosed with EAS caused by an appendiceal neuroendocrine tumor and summarized characteristics of these similar cases reported before.

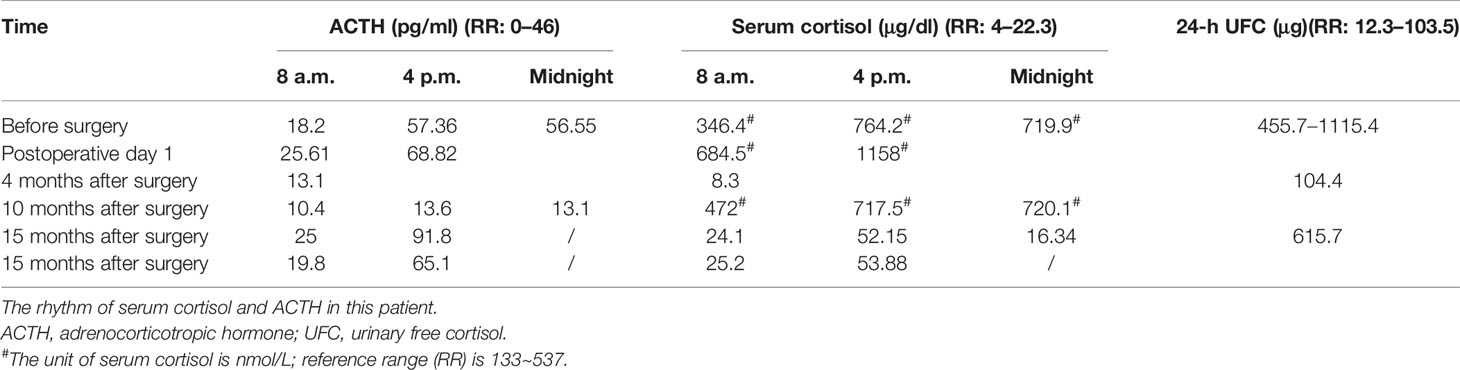

Case Report and Literature Review: We reported a case with Cushing’s syndrome who was misdiagnosed as pituitary ACTH adenoma at first and accepted sella exploration. Serum and urinary cortisol decreased, and symptoms were relieved in the following 4 months after surgery but recurred 6 months after surgery. The abnormal rhythm of plasma cortisol and ACTH presented periodic secretion and seemingly rose significantly after food intake. EAS was diagnosed according to inferior petrosal sinus sampling (IPSS). Appendiceal mass was identified by 68Ga-DOTA-Tyr3-octreotate (DOTATATE)-PET-CT and removed. The pathological result was consistent with appendiceal neuroendocrine tumor with ACTH (+). The literature review demonstrated 7 cases diagnosed with EAS caused by appendiceal neuroendocrine tumor with similarities and differences.

Conclusion: The diagnosis of an ectopic ACTH-producing tumor caused by the appendiceal neuroendocrine tumor can be a challenging procedure. Periodic ACTH and cortisol secretion may lead to missed diagnosis and misdiagnosis. IPSS is crucial in the diagnosis of EAS and 68Ga-DOTATATE-PET-CT plays an important role in the identification of lesions.

Introduction

Cushing’s syndrome (CS) is a condition of pathological hypercortisolism, which is classified into adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH)-dependent and ACTH-independent causes, in which ectopic ACTH syndrome (EAS) belonging to ACTH-dependent CS is a rare cause, which accounts for 5%–10% of CS (1, 2). The typical EAS is characterized by rapidly progressive clinical figures, including fatigue, severe hypokalemia, myasthenia, and serious infection. Therefore, early diagnosis and removal of responsible lesions are crucial, in order to remit hypercortisolism and prevent fatal complications. However, various difficulties may block proper diagnosis and treatment such as cyclic CS or occult EAS.

The common tumors that contributed to EAS had been published including pulmonary or thymic neuroendocrine neoplasms (NENs), pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (NETs), pheochromocytomas, and medullary thyroid carcinomas (3). Our center had summarized the clinical spectrum of 88 patients diagnosed with EAS, and it was found that thoracic origins (80.7%) were the most common cause of EAS, comprising pulmonary NETs (43.2%, 38/88), thymic/mediastinal NETs (33%, 29/88), and small cell lung cancer (SCLC) (3.4%, 3/88). Pancreatic NETs were found in 6 patients (6.8%) (4). An appendiceal NET is such as rare cause of EAS that there were only seven cases published until now worldwide (5–9).

Here, we report a case of a 34-year-old woman diagnosed with ectopic CS that was caused by excessive ACTH secretion by the appendiceal NET.

Case Report

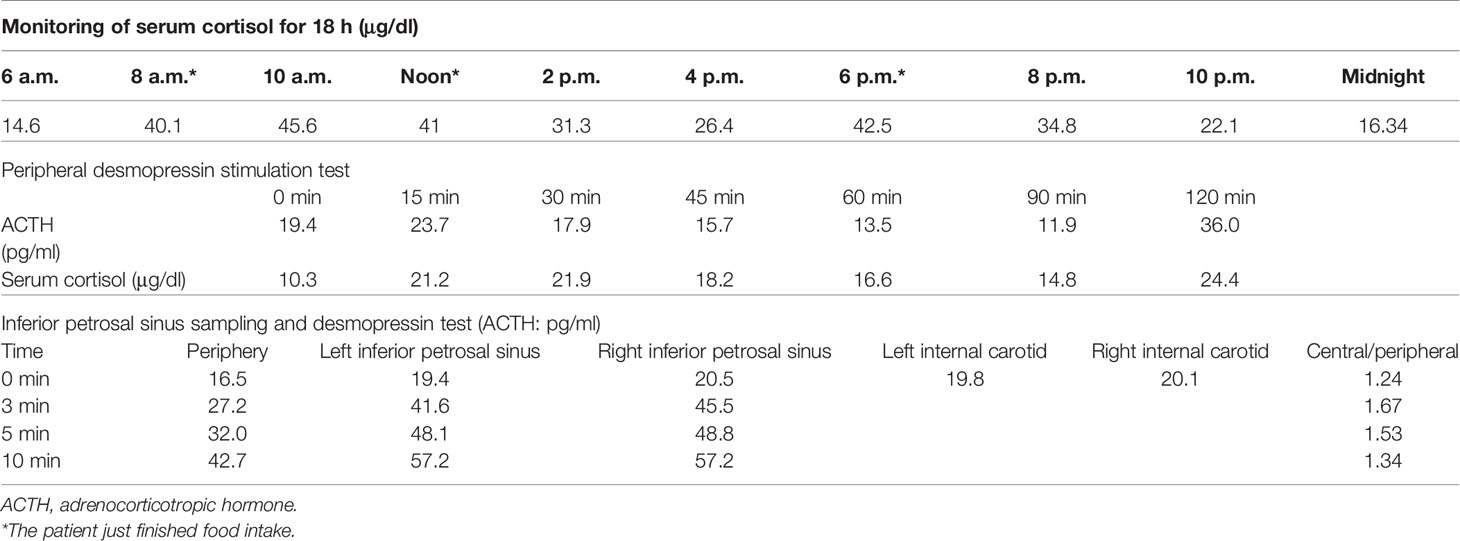

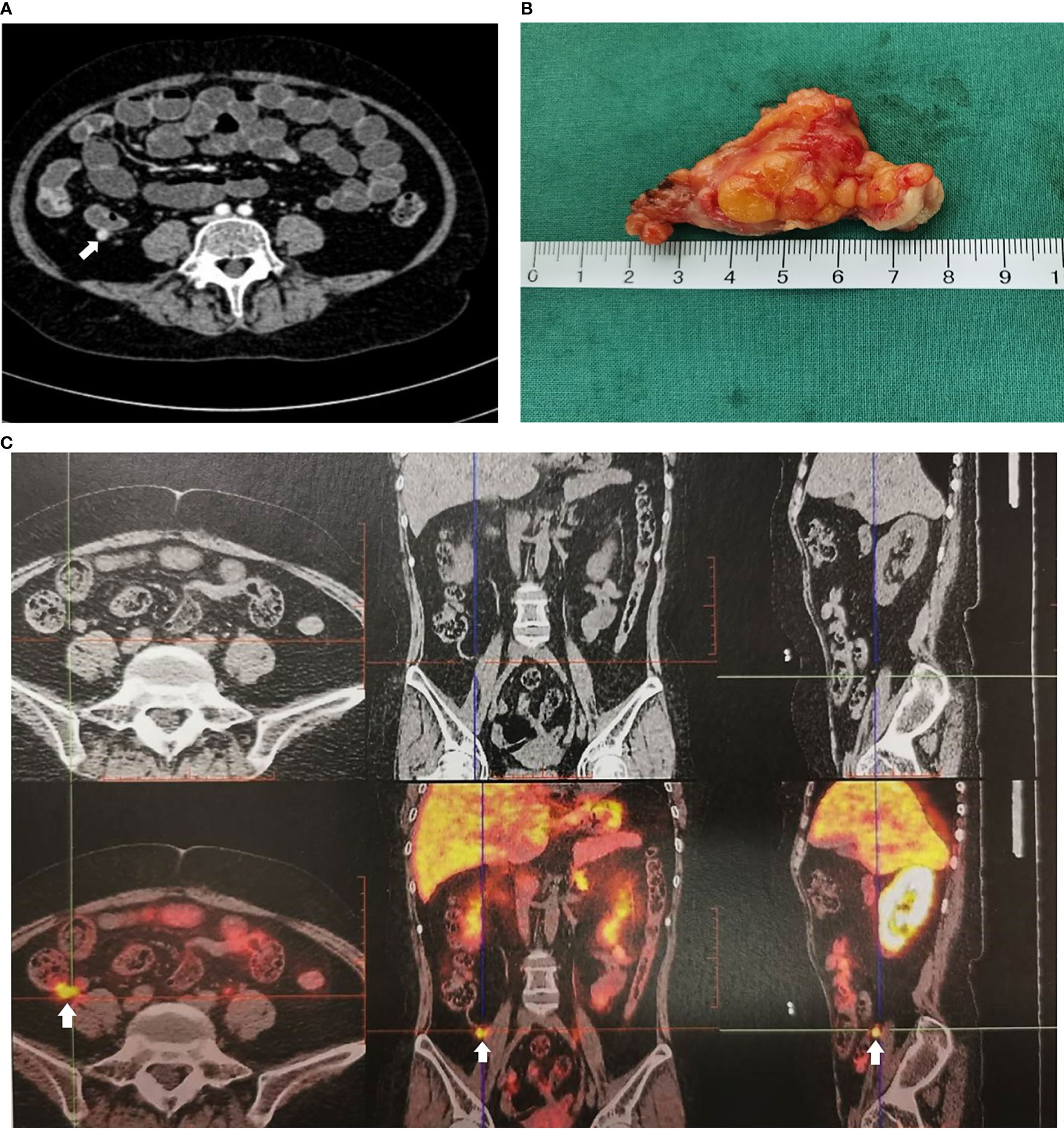

A 34-year-old female patient was admitted to our hospital due to hypertension and menstrual disorder. Two years before, she gradually developed a moon face, truncal obesity, acne, and hypertension during pregnancy and menopause after delivery. The level of blood potassium was approximately 2.66~3.64 mmol/L (3.5–5.5). She was diagnosed with Cushing’s disease in a local hospital depending on elevation levels of 24-h urinary free cortisol (UFC) of 1,155.4 μg (12.3–103.5) and ACTH of 18.2 pg/ml (0–46) (Table 1) and suspicious pituitary microadenoma in MRI initially. Consequently, a neurosurgical sella exploration was performed. Postoperative pathology did not conform to ACTH pituitary tumors. Nevertheless, the patient presented peeling and improvement of acne and hypokalemia with reduction of ACTH (13.1 pg/ml), plasma cortisol (8.3 μg/dl), and 24-h UFC (104.4 μg) 4 months after surgery (Table 1). The remission of hypercortisolemia was considered at that time. However, 6 months later, severe fatigue, hypokalemia, and hyperglycemia reappeared with an elevation of 24-h UFC (358.2 μg) and plasma cortisol of 720 nmol/L (133–537) (Table 1). The patient came to our clinic for further treatment. She has no special past or family history. Physical examination showed typical cushingoid features including moon facies, supraclavicular fatty pad, buffalo hump, skin atrophy, wide purple striae, purpura, and hirsutism. Further examination found hypokalemia, hypertension, osteoporosis (multiple rib fractures), and urolithiasis. Endocrine hormone-related examination revealed elevated levels of 24-h UFC (615.7~837.1 μg). The level of 8 a.m. serum cortisol fluctuated between 21.8 and 25.2 μg/dl, and ACTH was between 17.7 and 19.8 pg/ml (Table 1). Further examination suggested an abnormal rhythm of plasma cortisol and ACTH, which presented periodic secretion in 4-h cycles and seemingly rose significantly after meals (Table 2). A low-dose dexamethasone suppression test (LDDST; 2 mg of dexamethasone test) confirmed the diagnosis of hypercortisolism. A high-dose dexamethasone suppression test (HDDST; 8 mg of dexamethasone test) was not greater than 50% suppression of 24-h UFC from the basal value. Inferior petrosal sinus sampling (IPSS) revealed a central/peripheral ACTH ratio of less than 2 and less than 3 with desmopressin injection. The peripheral desmopressin stimulation test is shown in Table 2, which suggested a positive response to desmopressin. Diagnosis of ectopic ACTH syndrome with the cyclic secretion of ACTH (cyclic CS) was possible. In order to localize the source of ACTH secretion, the following were completed with no hint: octreotide scan; contrast-enhanced CT of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis; and 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)–positron emission tomography (PET)–CT. Finally, 68Ga-DOTA-Tyr3-octreotate (DOTATATE)-PET-CT was done, and an abnormal increase in radioactivity uptake was observed in the appendix, with a SUVmax of 17.1. Contrast-enhanced CT reconstruction of the small intestine also suggested a mass in the lumen near the blind end of the appendix with obvious enhancement (Figure 1). The patient had no history of abdominal pain, changes in bowel habits, or rectal bleeding; neither did she have any complaints of flushing or palpitation. Combined with the above examination results, it was considered that the responsible lesion was appendiceal mass, possibly an appendiceal NET. So a laparoscopic appendectomy was performed, and a mass measuring 1.4 cm × 0.6 cm × 0.5 cm was found in the blind side of the appendix (Figure 1B). Pathology examination revealed appendiceal NET (G2, mitotic 4/10HPF) invading the muscle layer of the appendix and the surrounding appendiceal tissue, and abnormality was not observed at the incisor margin. Immunohistochemistry: CgA (+), Ki-67 (index 3%), SYN (+), TTF-1 (−), CD56 (+), P53 (wild type), ATRX (+), SSTR2 (+), and ACTH (+). Serum cortisol dropped to 2.5 μg/dl, and ACTH decreased below 5 pg/ml the first day after the operation, suggesting remission of ectopic CS. Hydrocortisone replacement was given and gradually tapered down. Hypokalemia was treated and menstruation resumed, with weight loss and peeling 3 months after surgery.

Figure 1 Imaging examination of appendiceal mass. (A) Appendiceal mass showed by contrast enhanced CT reconstruction of the small intestine. (B) Appendiceal mass. (C) Appendiceal mass showed by 68Ga-DOTATATE-PET-CT.

Literature Review of Cushing’s Syndrome Caused by Appendiceal Neuroendocrine Tumor

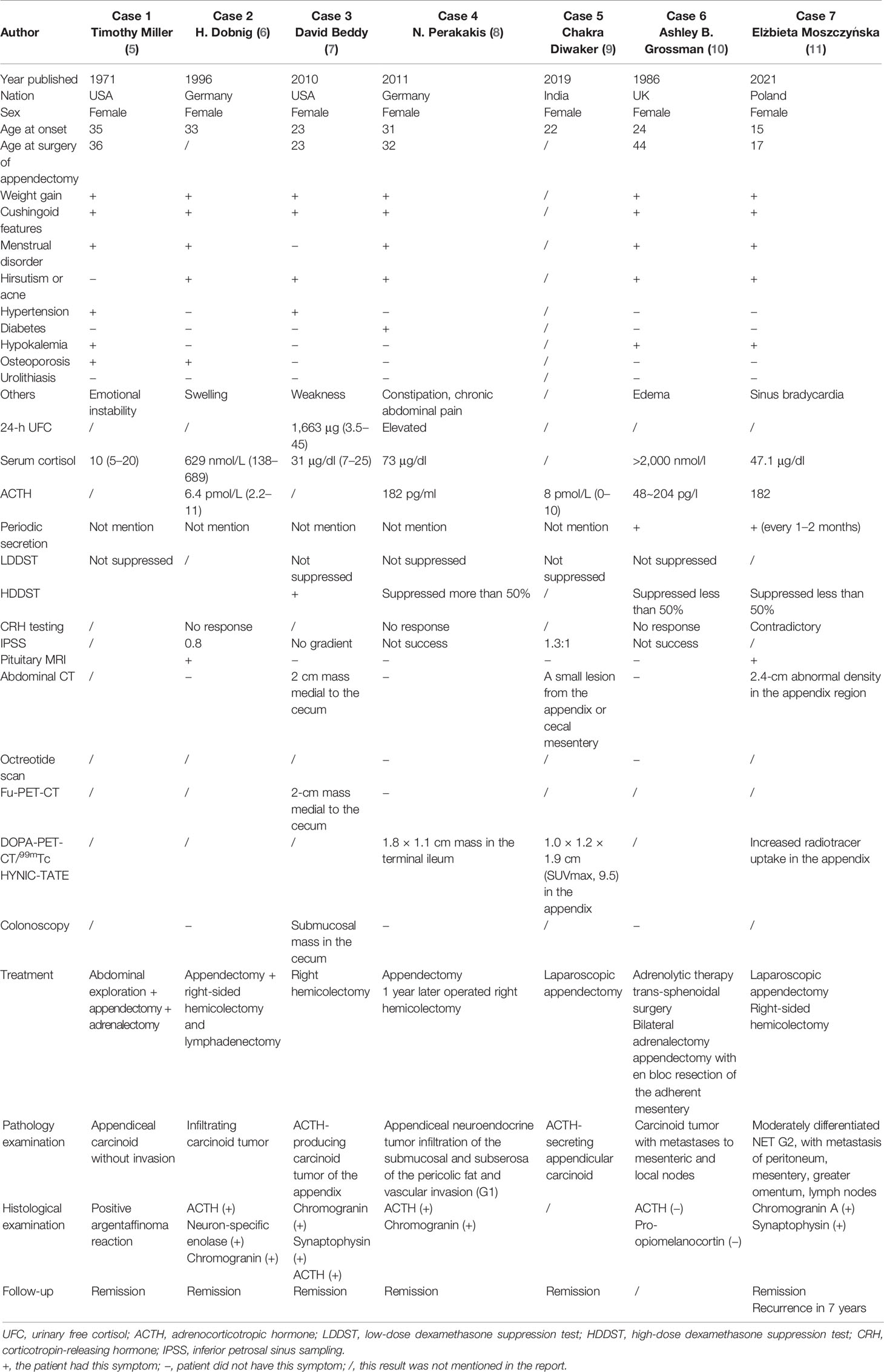

CS caused by appendiceal NETs is extremely rare. To our knowledge, only seven other cases have been reported until now. Here, we summarized and analyzed the characteristic features of these cases shown in Table 3. Interestingly, except for a 15-year-old girl, all of these reported cases were young women in their 20s~30s with typical cushingoid features and weight gain. Five patients showed an appearance of hyperandrogenemia including hirsutism or acne, but only one patient presented abdominal symptoms such as constipation and chronic abdominal pain. Hypertension, diabetes, and severe osteoporosis also have been found. Diagnosis of CS was certified by elevated 24-h UFC and serum cortisol, as well as LDDST. Levels of ACTH measured in five of these patients were all greater than 20 pg/ml, supporting ACTH-dependent CS. Successful IPSS was done in three patients who presented no gradient, supporting ectopic ACTH syndrome. It is difficult to find ectopic lesions, especially in the early disease course when PET-CT was not available. In two cases, the appendiceal lesions were found during exploratory laparotomy for the proposed adrenal resection. In the other four patients, 18F-FDG-PET-CT, DOPA-PET-CT, 68Ga-DOTATE-PET-CT, and 99mTc HYNIC-TATE-PET-CT were used to identify the responsible lesion in the appendix. All seven patients underwent appendectomies, and four of them underwent hemicolectomy, which resulted in remission of CS. Pathological results were all consistent with appendiceal NETs, and four of them had positive ACTH staining. Immunostaining for ACTH and pro-opiomelanocortin in case 6 was negative, which did not support diagnosis and may suggest that the tumor either was unrelated to the EAS or represents dedifferentiation of the original tumor. Two of seven patients presented periodic cortisol secretion.

Discussion

Appendiceal NETs represent the most common tumor of the appendix, found in 0.2%–0.7% of all appendectomies (12) and accounting for 2%–5% gastrointestinal NETs (13), commonly being identified incidentally during appendectomy performed for appendicitis. Appendiceal NETS are more common in women and are mostly submucosal at the tip of the appendix. They are less likely to cause obstruction and are mostly asymptomatic (13). NETs originate from neuroendocrine cells, secreting different substances such as somatostatin, gastrin, and ACTH. Excess amounts of these substances can lead to various clinical presentations; for instance, excess ACTH secretion induced CS.

Based on this case report and literature review, the diagnosis of CS caused by appendiceal NETs is challenging; even some patients were misdiagnosed to have pituitary ACTH microadenoma, and they underwent pituitary exploration surgery before the discovery of the appendiceal tumor. The main reasons for the difficulty in diagnosis were as follows. First of all, specific clinical manifestations were lacking. Cushing-like appearance, hypertension, diabetes, hypokalemia, and osteoporosis are still the main clinical manifestations. Unexpectedly, abdominal symptoms caused by appendiceal masses were not prominent, and only one patient has relevant symptoms, which was consistent with previous reports on asymptomatic appendiceal NETs (14).

Secondly, it is always challenging to distinguish between Cushing’s disease and ectopic ACTH-dependent CS by tests. IPSS has long been the gold standard to reliably exclude ectopic ACTH production but should preferably be performed in a specialized center because of potential patient risk. If IPSS was not allowed, a combination of three or four noninvasive approach tests was recommended, specifically corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) and desmopressin stimulation plus MRI, followed by whole-body CT if the diagnosis is equivocal (15). Unfortunately, the hospital where this patient was first admitted did not have the capacity to implement IPSS and CRH or desmopressin stimulation tests. Misdiagnosis led to inappropriate treatment options and prolonged illness. In addition, it is difficult to locate space-occupying lesions of the gastrointestinal tract by conventional imaging such as CT. It is gratifying that more and more highly specific imaging techniques are being used in the clinic. Somatostatin receptor scintigraphy (SRS), 18F-FDG, or 68Ga-DOTATATE-PET/CT was considered if CT or MRI did not show typical findings of ectopic tumors (4). Compared to the other two nuclear functional imaging techniques, 68Ga-DOTATATE-PET-CT had a higher affinity for the SSTR2 receptor and higher resolution to illustrate anatomical details, helping in the successful detection and accurate localization of small tumors characterized by SSTR (16–18). Taweesak et al. found that 68Ga-DOTATATE identified the primary ECS in 11/17 (65%) of previously occult tumors (19). The case in our report failed to identify the responsible lesions by CT, octreotide imaging, and 18F-FDG-PET-CT. Finally, 68Ga-DOTATATE-PET/CT successfully located the lesion in the appendix.

Periodic cortisol secretion also contributed to another difficulty in this case. Diagnosis of cyclic CS is based on at least three periods of confirmed hypercortisolemia interspersed by two periods of normocortisolemia (20). Although these criteria apply to most patients, they might be hard to fulfill in others, particularly if due to the long intercyclic phase or intermittent hypercortisolism. The presence of only two peaks and one trough of hypercortisolism, in this case, did not conform to the diagnostic criteria. But given the overall course of the disease, this patient is highly likely to be diagnosed with cyclic Cushing’s syndrome. The trough of cortisol production occurred just after sella exploration, giving the false appearance of recovery, which led to an incorrect diagnosis of pituitary ACTH adenoma. Meanwhile, the case showed great increasing levels of serum cortisol and ACTH at 4 p.m. compared to normal levels at 8 a.m., which may result in missed diagnosis of ACTH-dependent hypercortisolism if the blood sample at 4 p.m. was not collected. To further explore the rhythm of cortisol secretion in this patient, levels of serum cortisol were monitored every 2 h (from 8 a.m. to 12 p.m.) and suggested another shorter periodic secretion. Interestingly, most of the peaks seemed to appear after food intake, which had not been reported in previous case reports. A review of 65 reported cases demonstrated that cyclic CS originated in 26% from an ectopic ACTH-producing tumor, which included thymic carcinoid, bronchial carcinoid, pancreatic carcinoid, renal carcinoid, gastric carcinoid, epithelial thymoma, pheochromocytoma, and 2 occult cases. Cycle length ranged from 4 to 180 days (20). In a review of 7 cases of EAS caused by appendiceal carcinoids reported before, two of them showed periodic hormone secretion, but neither of these secretion cycles was as short and related to food consumption as in this case. We speculated that food residues flowing through the intestine and intestinal peristalsis after food intake might stimulate ACTH secretion of appendiceal NET. But it is a pity that we did not extend it for a longer time to confirm the association with food intake to distinguish with a variable secretion of cortisol.

The criteria of the desmopressin test associated with the best compromise between sensitivity and specificity were a relative cortisol increase >18% and ACTH increase >33% for the desmopressin test with 83% sensitivity and 81% specificity for the diagnosis of Cushing’s disease (21). This patient presented a positive response to desmopressin, which confirm Cushing’s disease, not EAS. However, it has been shown that some cases of EAS expressed the V2 receptor and responded to desmopressin (22). Periodic cortisol secretion may also disturb the result, which can explain the result of this patient.

For most T1 appendiceal tumors confined to the appendix, simple appendectomy is sufficient because of infrequent metastasis. In those with tumors larger than 2 cm, right hemicolectomy is recommended. Controversy exists regarding the management of appendiceal NETs measuring less than 2 cm with more aggressive histologic features. It has been suggested that the presence of lymph node metastases in appendiceal NETs smaller than 2 cm may lead to more aggressive management of appendiceal NETs with adverse prognostic factors (lymphovascular or mesangial invasion or atypical histological features). For these tumors, right hemicolectomy is recommended (23).

In conclusion, eight cases of an EAS due to appendiceal NETs have been reported until now. These cases demonstrate that the diagnosis of an ectopic ACTH-producing tumor can be a challenging procedure, which demands a systemic multidisciplinary approach, regular follow-ups, and the use of various novel imaging techniques. Periodic hormone secretion may be confusing, so there should be careful attention to screening and examination. For occult EAS, gastrointestinal NETs should not be ignored.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Peking Union Medical College Hospital. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author Contributions

YZ contributed to the conception and design of the study, diagnosis and treatment of the patient, literature review, and drafting of the manuscript. WM contributed to the diagnosis and treatment of the patient. YJ contributed to the diagnosis and treatment of the patient. GZ contributed to the treatment of the patient. LW critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. FG critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. HZ critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. LL contributed to the conception and design of the study, and diagnosis and treatment of the patient, and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Alexandraki KI, Grossman AB. The Ectopic ACTH Syndrome. Rev End Metab Disord (2010) 11(2):117–26. doi: 10.1007/s11154-010-9139-z

2. Newell-Price J, Bertagna X, Grossman AB, Nieman LK. Cushing’s Syndrome. Lancet (2006) 367(9522):1605–17. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68699-6

3. Lacroix A, Feelders RA, Stratakis CA, Nieman LK. Cushing’s Syndrome. Lancet (2015) 386(9996):913–27. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61375-1

4. Miao H, Lu L, Zhu H, Du H, Xing X, Zhang X, et al. Experience of Ectopic Adrenocorticotropin Syndrome: 88 Cases With Identified Causes. Endocr Pract (2021) 27(9):866–73. doi: 10.1016/j.eprac.2021.02.015

5. Miller T, Bernstein J, Van Herle A. Cushing’s Syndrome Cured Resection of Appendiceal Carcinoid. Arch Surg (1971) 103(6):770–3. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1971.01350120134028

6. Dobnig H, Stepan V, Leb G, Wolf G, Buchfelder M, Krejs GJ. Recovery From Severe Osteoporosis Following Cure From Ectopic ACTH Syndrome Caused by an Appendix Carcinoid. J Intern Med (1996) 239(4):365–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.1996.416763000.x

7. Beddy D, Larson D. Cushing’s Syndrome Cured by Resection of an Appendiceal Carcinoid Tumor. Int J Colorectal Dis (2011) 26(7):949–50. doi: 10.1007/s00384-010-1073-8

8. Perakakis N, Laubner K, Keck T, Steffl D, Lausch M, Meyer PT, et al. Ectopic ACTH-Syndrome Due to a Neuroendocrine Tumour of the Appendix. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes (2011) 119(9):525–9. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1284368

9. Diwaker C, Shah RK, Patil V, Jadhav S, Lila A, Bandgar T, et al. 68Ga-DOTATATE PET/CT of Ectopic Cushing Syndrome Due to Appendicular Carcinoid. Clin Nucl Med (2019) 44(11):881–2. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0000000000002766

10. Grossman AB, Kelly P, Rockall A, Bhattacharya S, McNicol A, Barwick T. Cushing’s Syndrome Caused by an Occult Source: Difficulties in Diagnosis and Management. Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab (2006) 2(11):642–7. doi: 10.1038/ncpendmet0327

11. Moszczyńska E, Pasternak-Pietrzak K, Prokop-Piotrkowska M, Śliwińska A, Szymańska S, Szalecki M. Ectopic ACTH Production by Thymic and Appendiceal Neuroendocrine Tumors - Two Case Reports. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab (2020) 34(1):141–6. doi: 10.1515/jpem-2020-0442

12. Pape UF, Niederle B, Costa F, Gross D, Kelestimur F, Kianmanesh R, et al. ENETS Consensus Guidelines for Neuroendocrine Neoplasms of the Appendix (Excluding Goblet Cell Carcinomas). Neuroendocrinology (2016) 103:144–52. doi: 10.1159/000443165

13. Alexandraki KI, Kaltsas GA, Grozinsky-Glasberg S, Chatzellis E, Grossman AB. Appendiceal Neuroendocrine Neoplasms: Diagnosis and Management. Endocr Relat Cancer (2016) 23(1):R27–41. doi: 10.1530/ERC-15-0310

14. Ahmed M. Gastrointestinal Neuroendocrine Tumors in 2020. World J Gastrointest Oncol (2020) 1512(8):791–807. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v12.i8.791

15. Fleseriu M, Auchus R, Bancos I, Ben-Shlomo A, Bertherat J, Biermasz NR, et al. Consensus on Diagnosis and Management of Cushing’s Disease: A Guideline Update. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol (2021) 9(12):847–75. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(21)00235-7

16. Deppen SA, Blume J, Bobbey AJ, Shah C, Graham MM, Lee P, et al. 68Ga-DOTATATE Compared With 111In-DTPAOctreotide and Conventional Imaging for Pulmonary and Gastroenteropancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Nucl Med (2016) 57(6):872–8. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.115.165803

17. Hayes AR, Grossman AB. The Ectopic Adrenocorticotropic Hormone Syndrome: Rarely Easy, Always Challenging. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am (2018) 47(2):409–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2018.01.005

18. Barrio M, Czernin J, Fanti S, Ambrosini V, Binse I, Du L, et al. The Impact of Somatostatin Receptor-Directed PET/CT on the Management of Patients With Neuroendocrine Tumor: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Nucl Med (2017) 58(5):756–61. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.116.185587

19. Wannachalee T, Turcu AF, Bancos I, Habra MA, Avram AM, Chuang HH, et al. The Clinical Impact of [68 Ga]-DOTATATE PET/CT for the Diagnosis and Management of Ectopic Adrenocorticotropic Hormone - Secreting Tumours. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) (2019) 91(2):288–94. doi: 10.1111/cen.14008

20. Meinardi JR, Wolffenbuttel BHR, Dullaart RPF. Cyclic Cushing’s Syndrome: A Clinical Challenge. Eur J Endocrinol (2007) 157:245–54. doi: 10.1530/EJE-07-0262

21. Frete C, Corcuff JB, Kuhn E. Non-Invasive Diagnostic Strategy in ACTH-Dependent Cushing’s Syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab (2020) 105(10):dgaa409. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgaa409

22. Barbot M, Trementino L, Zilio M, Ceccato F, Albiger N, Daniele A, et al. Second-Line Tests in the Differential Diagnosis of ACTH-Dependent Cushing’s Syndrome. Pituitary (2016) 19(5):488–95. doi: 10.1007/s11102-016-0729-y

Keywords: Cushing’s syndrome, ectopic ACTH syndrome (EAS), cyclic Cushing’s syndrome, appendiceal neuroendocrine tumor, 68Ga-DOTATATE-PET-CT, case report

Citation: Zhao YX, Ma WL, Jiang Y, Zhang GN, Wang LJ, Gong FY, Zhu HJ and Lu L (2022) Appendiceal Neuroendocrine Tumor Is a Rare Cause of Ectopic Adrenocorticotropic Hormone Syndrome With Cyclic Hypercortisolism: A Case Report and Literature Review. Front. Endocrinol. 13:808199. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2022.808199

Received: 03 November 2021; Accepted: 24 January 2022;

Published: 18 February 2022.

Edited by:

Piero Ferolla, Umbria Regional Cancer Network, ItalyReviewed by:

Giorgio Arnaldi, Marche Polytechnic University, ItalyAshley Grossman, Queen Mary University of London, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2022 Zhao, Ma, Jiang, Zhang, Wang, Gong, Zhu and Lu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Lin Lu, bHVsaW44OEBzaW5hLmNvbQ==

Yu Xing Zhao

Yu Xing Zhao Wan Lu Ma

Wan Lu Ma Yan Jiang

Yan Jiang Guan Nan Zhang2

Guan Nan Zhang2 Lin Jie Wang

Lin Jie Wang Feng Ying Gong

Feng Ying Gong Hui Juan Zhu

Hui Juan Zhu Lin Lu

Lin Lu