- 1Department of Chemistry, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, SK, Canada

- 2Saskatchewan Polytechnic, Chemical Technology Department, Saskatoon, SK, Canada

Selective phosphate (Pi) remediation from saline aquatic environments is crucial in combating eutrophication. In this study, biocomposite adsorbents with 80% spent coffee grounds, variable chitosan content, and either 1% or 5% metal oxide (MO) content (-A = 1 wt.%; -B = 5 wt.%) were evaluated. The type of MO was either Fe2O3 (Fe-B or Fe-A) or Al2O3 (Al-B or Al-A). The material characterization of these biocomposites was achieved via thermogravimetry and spectroscopic techniques (13C NMR, FT-IR, and X-ray diffraction (XRD)). Composite formation and coordination between functional groups was evidenced by FT-IR spectral and XRD results. The role of sulfate as a competitor anion was evaluated due to its environmental significance. Single-component isotherm studies showed equilibrium adsorption capacities that range from ca. 13 mg/g–20 mg/g for phosphate and 9 mg/g–36 mg/g for sulfate. To investigate the selectivity of phosphate over sulfate, binary selectivity experiments (equal concentration) were conducted. The binary selectivity factor αt/c ranged from 14 to 16 for Al-based and from 6 to 9 for Fe-based composites. The adsorption capacity ratio was ca. 2–3 for Al-based and ca. 4 for Fe-based composites, which favor phosphate in the presence of sulfate (at 100 mg/L for both anions). This was verified through adsorption experiments in binary, ternary, and quaternary anion systems, where different adsorption sites account for the concerted anion adsorption. Kinetic studies according to the pseudo nth-order model for two selected composites showed a reaction order of ca. 1.6–1.8 for Al-A and Fe-B. Adsorption of phosphate in spiked river water with 10 mg/L phosphate (spiked) and ca. 80 mg/L sulfate (natural) for Al-A and Fe-B resulted in ca. 0.4 mg/g–0.5 mg/g uptake capacity of phosphate. Coordination of phosphate was inferred to follow inner-sphere complexation, in contrast to that of sulfate. In turn, this study demonstrates how granular adsorbents derived from food waste with high lignocellulose content can be modified with MO to yield phosphate-selective adsorption in saline aqueous media.

1 Introduction

Phosphate (Pi) is a key nutrient for plant growth, and the presence of excess levels of Pi in aquatic environments can result in eutrophication. Phosphate buildup in aquatic media can occur due to agricultural run-off events, where phosphate levels up to 5 mg/L have been reported (Liu et al., 2021). Phosphate can originate through the application of fertilizer for agricultural production (manure and phosphate minerals) (Mekonnen and Hoekstra, 2018). On average, only 20% of available phosphorus is used by plants, while the remainder ends up in water bodies (Mekonnen and Hoekstra, 2018; Chen et al., 2022). It is increasingly necessary to reduce Pi to lower levels (<0.1 mg/L) or very low levels (<0.01 mg/L) to combat the detrimental effects of eutrophication in aquatic environments (Mayer et al., 2013; Wu et al., 2020). Phosphate remediation and its recovery for subsequent re-use with sustainable adsorbent materials contribute to the establishment of a circular bioeconomy. Efficient and cost-effective removal of phosphate from environmental matrices presents a challenge due to the variable levels of dissolved solids and speciation (orthophosphate, condensed/poly phosphates, and organic phosphates). In cases where phosphate co-exists with other oxyanions, selective adsorption is desired in complex mixtures of anions (Usman et al., 2022; Owodunni et al., 2023). However, this can be challenging in saline water, especially for provinces such as Saskatchewan (SK), which is a part of the Western Canada Sedimentary Basin, where elevated sulfate levels have been reported. The presence of elevated sulfate can attenuate the phosphate uptake efficiency of adsorbents via competitor ion effects. Sulfate levels in SK can reach up to 6 g/L (or 24 g/L in extreme cases), which presents significant competitor ion effects for effective adsorption of phosphate (Pincus et al., 2020). Commonly available removal techniques, such as reverse osmosis and ion exchange chromatography that utilize synthetic resins, may be efficient, but they present limitations due to their high operational costs and cost-effectiveness (Quintana-Baquedano et al., 2023). In general, anion removal via adsorption offers a sustainable remediation strategy, and research into effective and low-cost adsorbents is an active field of ongoing research.

The limitations of membrane-based approaches can be circumvented through the development of biosorbents as an alternative strategy for adsorption-based water treatment. Carbohydrate polymers and biomaterials are gaining research interest due to their sustainability and circularity advantages (Hamad and Idrus, 2022; Kheilkordi et al., 2022). Previous research by our group reported the development of granular biosorbents that incorporate spent coffee grounds (SCGs), torrefied wheat straw, and oat hulls as key components for the design of biocomposites to achieve effective contaminant remediation. The utility of these biomass fractions in water treatment without conversion into activated carbon was demonstrated to rival that of various synthetic resin adsorbents (Steiger et al., 2023; Steiger et al., 2024; Mohamed et al., 2022; Namasivayam and Sangeetha, 2008; Guimarães and Leão, 2014; Geies et al., 2018). For example, SCG waste is an abundant and cost-effective platform material for the development of biosorbent materials. In Canada, coffee consumption reached ca. 329,000 metric tons during the 2022–2023 period, which represents potentially large amounts of SCG waste that can be utilized as platform biomass for adsorbents. Transforming SCG waste into value-added biosorbent pellets provides the dual advantage of managing waste and addressing water pollution, which is aligned with the principles of sustainability and circularity. SCG, as a platform and filler material, contains lignin, cellulose, proteins, hemicellulose, and other (trace) constituents that are abundant with functional groups such as hydroxyl (-OH) and carboxyl (-COOH) groups. In contrast, chitosan is a copolymer that contains β(1→4)-linked D-glucosamine units, which can form a polycation under mild acidic conditions that favors adsorption of anionic species via electrostatic interactions (Solgi et al., 2023). Chitosan is derived from partial deacetylation of chitin, which is the second most common carbohydrate polymer after cellulose (Ahmed et al., 2017; Crini, 2005; Desbrières and Guibal, 2018). Additionally, polar functional groups (-NH2 and -OH) enhance electrostatic interactions, hydrogen bonding, and chelation mechanisms (Mohamed et al., 2022; Solgi et al., 2024). The synergistic interaction between the lignocellulose fraction of SCG biomass and the amino groups of chitosan yields a unique and low-cost composite material that offers a sustainable adsorbent for water remediation. However, to afford selective phosphate removal in the presence of sulfate as the most common competitor ion, additional modification is proposed.

To design an improved adsorbent for phosphate, the use of hard Lewis acids (Al3+, Fe3+, and metal oxides) is favorable as these metal oxides (MOs) can form inner sphere complexes with phosphate through ligand exchange (Wu et al., 2020; Pincus et al., 2020; Alvares et al., 2023; Shan et al., 2022). A specific study describing the use of hydrated ferric oxide for phosphate removal in the presence of competitor anions (e.g., sulfate, chloride, or bicarbonate) was reported (Blaney et al., 2007). In particular, previous studies on chitosan-based granular adsorbents for water treatment have been reported (Solgi et al., 2024; Solgi et al., 2020; Pearson, 1963). Du et al. (2024), in a systematic study of biochars, stated that the delocalized π-electrons of these systems are well-suited for phosphate remediation but do not afford selective adsorption of phosphate. Structural modification with metal (oxides) contributes to phosphate selectivity by exploiting the HSAB principle (PO43- > SO42- > Cl− > NO3−) (Pearson, , 1963). The incorporation of specific MOFs (metal-organic frameworks) into biochar designed for optimum phosphate uptake was described and evaluated (Du et al., 2024; Xu et al., 2017). Furthermore, studies regarding selective phosphate uptake often utilize iron or aluminum oxides or hydroxides for effective phosphate remediation (Sousa et al., 2012; Roy et al., 2021; Ajmal et al., 2018). To achieve orthophosphate selectivity, these MOs were chosen as component additives in these composites. Thus, MOs in the form of iron (III) oxide (Fe) and acidic aluminum oxide (Al) were blended with SCGs and chitosan in variable wt. ratios, and the respective uptake capacity toward nitrate, phosphate, sulfate, and chloride was investigated in this study.

However, while efficient adsorbent materials with selectivity have been described, the development of low-cost adsorbents with variable morphology for practical applications is a key goal. Hence, granular composite adsorbents were prepared, and their adsorption properties were reported in this study. Furthermore, this study focused on pH 7 since most water sources have a typical neutral pH range (Jiang et al., 2022). This study aims to provide an adsorbent system that exhibits selectivity toward phosphate under neutral pH conditions, eliminating the need for pH adjustments to the media. The adsorbent design was aimed at providing a phosphate-selective granular adsorbent for potential pre-treatment of sulfate-laden water sources to enable the selective removal of high-value oxyanions by adsorption without competitive anion effects (e.g., sulfate). Additionally, phosphate-spiked river water (ca. pH 8 without adjustment) was also investigated to assess the role of competitor ions (e.g., bicarbonate, chloride, and nitrate) in the presence of sulfate in a complex environmental matrix.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Materials

SCG was collected after brewing (Canadian ground coffee). Sodium sulfate (anhydrous), sodium dihydrogen phosphate (ACS), hydrochloric acid (37%, ACS), sodium hydroxide (97%), sodium chloride (ACS), potassium nitrate (ACS), isopropanol, glycerol, aluminum oxide (acidic), iron (III) oxide, and glacial acetic acid were acquired from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Ottawa, ON, CA). Potassium sodium tartrate tetrahydrate (ACS, 99%), potassium antimony (II) tartrate hydrate (ACS, 99%), ammonium molybdate (ACS, 81%–83%), L-ascorbic acid (ACS), sulfuric acid, anhydrous barium chloride, chitosan (low molecular weight, degree of deacetylation ca. 80%), and a ready-to-use phosphate determination reagent (vanadate-molybdate reagent; 1.08498 product number; 1084980500 SKU) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (Oakville, Canada).

2.2 Methods

2.2.1 Analytical methods

The concentration of anions (ion mix) was independently assessed via ion chromatography using a Metrohm model 881, an A Supp 5 250/4.0 column, and Magic Net 4.2 software, which is capable of detecting fluoride, chloride, nitrite, bromide, nitrate, phosphate, and sulfate. Eluent A Supp 5 was used, and the solutions were filtered using 0.45 µm syringe filters. Pi determination of single-component solutions at low concentration (Pi >10 mg/L) was carried out using a UV–VIS spectrophotometer (Fisher Scientific, Spectronic 200 E, Waltham, United States, 900 nm) with freshly prepared vanadate-molybdate reagent (batches of 10 mL reagent), as described earlier (Steiger et al., 2024; Bui et al., 2024; Ibnul and Tripp, 2022; Okazaki et al., 2015; Venegas-García et al., 2023). In brief, the mixed reagent is stable for ca. 6 h, and prepared solutions are made fresh as required. The vanadate-molybdate reagent was prepared in situ by combining the following components: 10.796 g/100 mL ascorbic acid, 2.96 g/100 mL ammonium molybdate, 0.4908 g/100 mL antimony potassium tartrate, and 13.66 mL/100 mL sulfuric acid in a volume ratio of 2:2:1:5, respectively. The calibration curve was prepared using a 1 mL sample, 2 mL Millipore water, and 0.5 mL freshly prepared vanadate-molybdate reagent (concentration range 2 mg/L–14 mg/L Pi) and shaken well. Color development was allowed for 20 min, and absorbance values were measured at 900 nm using a UV–visible spectrophotometer. For Pi determination at 100 mg/L and 500 mg/L, a ready-to-use Pi determination reagent (vanadate-molybdate) employed a wavelength of 420 nm due to a less demanding limit of detection compared to Pi determinations with 10 mg/L or less initial values. For the determination of sulfate via UV–VIS spectroscopy, a turbidity method according to the Indian Standard 3025 was used (Bureau of Indian Standards, 2003). In brief, 1.25 mL of a conditioning reagent (150 g NaCl, 60 mL HCl (37%), 100 mL glycerol, and 200 mL isopropanol in 1 L water) and ca. 2 mL sample (depending on the concentration) were added to a 25 mL volumetric flask and brought to the mark with Millipore water. Then, ca. 100 mg anhydrous barium chloride was added and shaken, and measurements (420 nm) were taken after 10 min. Triplicate measurements per sample were performed, and determinations were acquired in duplicate.

13C NMR spectra of solids were measured via a 4-mm DOTY CP-MAS probe on a Bruker AVANCE III HD spectrometer (125.77 MHz, with a 1H frequency of 500.13 MHz). Spectra were measured in the CP-TOSS mode (cross-polarization with total suppression of spinning sidebands) at 7.5 kHz. The chemical shifts were internally referenced to adamantane (38.48 ppm). FT-IR spectra were collected in reflectance mode on a Bio-Rad FTS-40 spectrophotometer between 4,000 cm-1 and 500 cm-1 with a resolution of 4 cm-1. Samples were co-ground with KBr (FT-IR grade) in a weight ratio of 1:10 (sample: KBr). Thermogravimetric analysis of ground samples employed a TA Instruments Q50 with open aluminum pans under a N2 atmosphere at a heating rate of 10 °C/min and a 1 min equilibration time at 30 °C prior to heating up to 500 °C. Powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) was measured using a Rigaku Ultima IV (Cu-source 1.54056 Å) and Cross Beam Optics over a 5°–80° 2θ range.

2.2.2 Pellet preparation

The granular adsorbents containing MO were prepared as follows:

Pellets of Al-A or Fe-A contained 8 g SCGs, 1.5 g chitosan, and 0.5 g MO (Fe2O3 or Al2O3), which corresponds to 5 wt. % MO, and 15% chitosan content. In comparison, pellets of Al-Al-A or Fe-B contained 8 g SCGs, 1.9 g chitosan, and 0.1 g MO (Fe2O3 or Al2O3), which corresponds to 1 wt. % MO, 80% SCG, and 19% chitosan content.

The powdered constituents (without further grinding) were combined in a mortar and mixed prior to the addition of ca. 15 mL–25 mL of 0.2 M acetic acid solution. Then, the solids were mixed until uniform consistency was reached and quickly pressed into plastic molds (small pistol primer trays, Campro, Unis Ginex, Goražde, Bosnia) and dried for at least 24 h at room temperature (20 °C–22 °C).

2.2.3 Isotherm adsorption experiments

The oxyanion concentration levels were tested in duplicate using ion chromatography and in triplicate using UV–VIS. The adsorption isotherm profiles were conducted with three pellets (ca. 80 mg–100 mg total) in 10 mL of solution (in 4-dram vials). The pH of the Pi solution was adjusted to 7. The pH of the sulfate solution was not adjusted. After combining the pellets and the solution, the vials were placed on a SCILOGEX shaker and agitated for 16 h at ca. 22 °C (220 rpm). Then, the supernatant was collected, centrifuged, and filtered, if required. The adsorption capacity was calculated using Equation 1 (Abin-Bazaine et al., 2022):

Here, qe is the adsorption capacity at equilibrium (mg/g), Ci is the initial concentration (mg/L), Ce is the concentration at equilibrium (mg/L), V is the total volume (L), and m is the adsorbent mass (g).

The Sips isotherm model (also known as the Langmuir–Freundlich combination isotherm; Equation 2) was used to estimate the adsorption capacity (Abin-Bazaine et al., 2022; Sips, 1948).

Here, qm represents the monolayer adsorption capacity (mg/g), qe stands for the equilibrium adsorption capacity, K represents the equilibrium constant (L/g), and nS is the heterogeneity factor. In contrast to the Langmuir isotherm model (where a homogeneous surface is assumed) or the Freundlich isotherm model (heterogeneous surface, valid at low adsorbate concentrations), the Sips isotherm model (Equation 2) can yield additional results related to surface-site heterogeneity. For the case of nS = 1, the Sips isotherm model converges with the Langmuir isotherm to account for homogeneous adsorption sites.

2.2.4 Selectivity experiments

For selectivity experiments with a focus on Pi, with and without competitive anions (nitrate, sulfate, and chloride), 10 mL of solution and three pellets were used, which is similar to the method described in Section 2.2.3. The concentration was aimed at reflecting environmentally relevant levels and was set at 10 mg/L for each anion.

To determine the selectivity between Pi and sulfate via the adsorption capacity ratio and binary selectivity factor, concentrations of 100 mg/L and 500 mg/L were chosen (either sulfate or phosphate and sulfate + phosphate in solution; three pellets, ca. 100 mg dosage).

The adsorption capacity (AC) ratio can be calculated using Equation 3 (Pincus et al., 2020):

Here, qt stands for the uptake capacity of the target species in a single-component system, and qt+c stands for the uptake capacity of the target species in the presence of a competitive anion (sulfate).

Furthermore, the selectivity can also be expressed as the binary selectivity factor (αt/c), which can be estimated using Equation 4 (Pincus et al., 2020; Li et al., 2016):

Here, qc stands for the equilibrium uptake of the competitive species, Ce,c stands for the equilibrium concentration of the competitive species, qt represents the uptake at equilibrium concentration of the target species, and Ce,t represents the equilibrium concentration of the target species.

2.2.5 Adsorption kinetics

To evaluate the adsorption kinetics of Pi by the pellets, 50 mL of a 100 ppm Pi solution and ca. 15 pellets were used (pre-soaked in ultrapure water overnight prior to the adsorption process). The process was monitored for over 240 min. The experiment was conducted in a 200-mL beaker to ensure effective contact between the pellets and the Pi solution. Constant agitation was maintained using a magnetic stirrer to enhance mass transfer and prevent pellet settling. At each sampling interval, 2 mL of the solution was withdrawn, filtered, and subsequently analyzed for residual Pi concentration using a UV–VIS spectrophotometer. The kinetic adsorption models pseudo-first-order (PFO; Equation 5), pseudo-second-order (PSO; Equation 6), pseudo-nth-order (PNO; Equation 7), and Weber–Morris intraparticle diffusion (IPD) models (Equation 8) were investigated (William Kajjumba et al., 2019; Tseng et al., 2014):

Here, qt represents the adsorption capacity (mg/g) at time (t), qe stands for the adsorption capacity at equilibrium (mg/g), and k1 is the rate constant for the PFO kinetic model.

Here, k2 represents the rate constant for the PSO kinetic model.

Here, n stands for the reaction order, and kn represents the rate constant for the PNO model.

Additionally, the kinetic data can be analyzed through the intraparticle diffusion (Weber–Morris) model (Wang and Guo, 2022; Chu et al., 2025).

Here, k represents the kinetic rate constant (mg g-1 t-0.5).

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Characterization

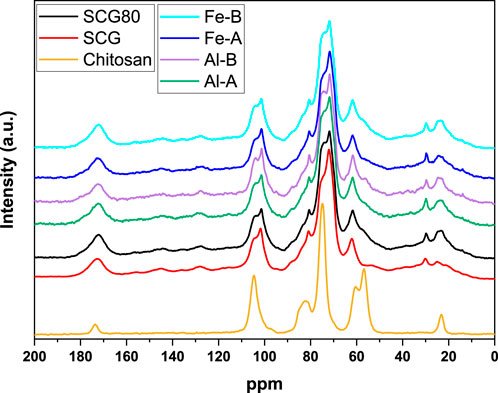

In line with a previous report, a physical blend of the constituents was obtained by compositing biomass, chitosan, and MO additives (Steiger et al., 2023). To highlight the nature of the blend and the obtained adsorbents, characterization in the form of 13C solids NMR spectroscopy was performed (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. 13C solids NMR spectral data with normalized intensity versus chemical shift in parts per million (ppm) for various samples. The spectra are stacked for ease of comparison. The legend identifies seven distinct lines: SCG80 (black), SCG (red), Chitosan (yellow), Fe-B (cyan), Fe-A (purple), Al-B (green), and Al-A (blue).

Chitosan shows characteristic spectral bands for the polysaccharide [104.8 ppm (C1), 82.7 ppm (C4), 75.0 ppm (C3/C5), 60.5 ppm (C6), and 57.1 ppm (C2)], along with a signature for its acetyl groups (173.7 ppm for C=O; 23.1 ppm for -CH3), which is noted for all composites with a fixed content of chitosan (20%). A signature with greater line-width occurs near 175 ppm–180 ppm and 23 ppm, which may also originate from residual acetate counter ions within the pellet matrices. In contrast, SCG shows signatures for lignin [between 160 ppm and 110 ppm, 56 ppm (also from proteins)] and lipids (30.1 ppm, 24.8 ppm, and 14.0 ppm). Additional lignin lines overlap with the carbohydrate signatures (Kögel-Knabner, 2002; Carruthers-Taylor et al., 2020; Taleb et al., 2020). 13C NMR signals for (hemi)cellulose are observed, where peaks for cellulose occur at 104.9 ppm (C1), 88.8 ppm (C4 crystalline, small), 84.0 ppm (C4 amorphous, small), 75.2 ppm, 72.2 ppm (C2/3/5), and 61.9 ppm (C6) (Atalla and VanderHart, 1999; Park et al., 2010; Nehls et al., 1994; Kostryukov et al., 2021). Signatures occur at 81.1 ppm and 101.9 ppm that can be assigned to galactose groups within the SCG via hemicellulose fractions (Kanai et al., 2019). The incorporation of MOs does not significantly affect the observed signals, which indicates apparently minor effects of cooperative or cohesive interactions. In summary, lignin and carbohydrate signals are mostly evident for SCG within the composites, while chitosan and acetate (-CH3 and the carbonyl group) contribute minimally (based on the maximum 20 wt%) to the overall NMR profile. The structural analysis herein can be corroborated via FT-IR spectroscopy to verify the presence of functional groups within the composites (Figure 2).

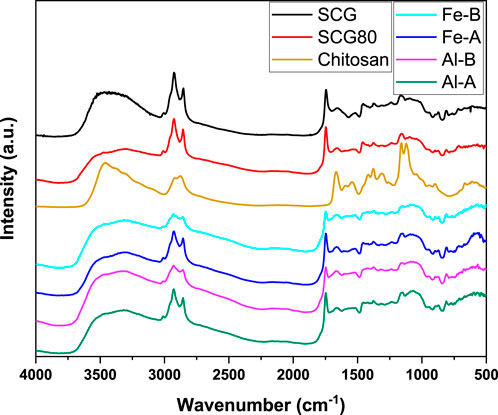

Figure 2. FT-IR spectral results of the composites, precursor raw materials, and the non-neutralized SCG80 pellet.

Specifically, for chitosan has a relatively strong band at approximately 3,470 cm-1 is noted, along with broad bands for SCG, SCG80, and the four mineral oxide composites. This indicates the increased presence of amine groups, mainly to the OH-groups in the composites and SCG. In contrast, a small band at 3,010 cm-1 (C–H stretching in cis C=C bands) appears in SCG, which is in agreement with a detailed study by Zuluaga et al. (2024). C–H groups (symmetric and asymmetric stretching) are visible at approximately 2,931 cm-1 and 2,852 cm-1, respectively. A band at 1,748 cm-1 (absent in chitosan) indicates the presence of C=O groups (fatty acid esters in SCG). A relatively strong band, which is abated in the composites and SCG at 1,669 cm-1, was assigned to amide bending. Similarly, bands at 1,167 cm-1 and 1,121 cm-1 are pronounced for chitosan, and they were assigned to the glycosidic linkage (C–O–C). These bands are abated in SCG and the resulting composites. No specific iron or aluminum oxide signals could be assigned within the composites due to their relatively low content, highlighting the physically blended nature of the composites (Radwan-Pragłowska et al., 2019).

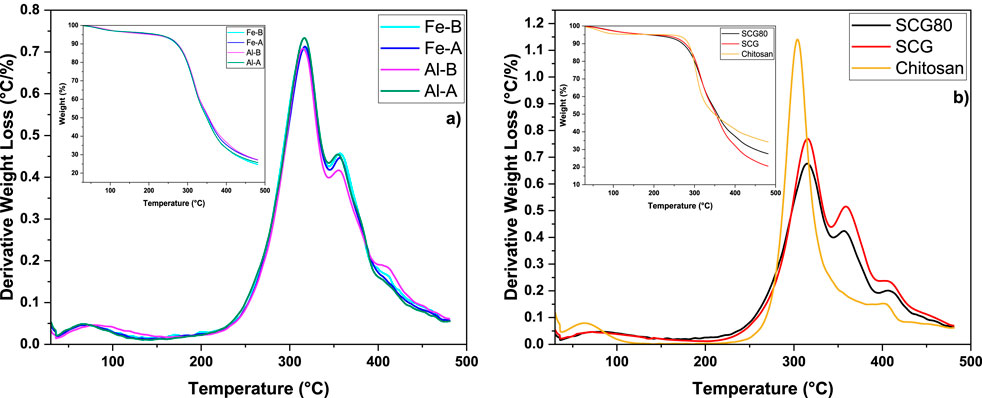

To confirm the physical nature of the biocomposites, thermogravimetry profiles of the granular adsorbents under an N2 atmosphere were obtained (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Derivative weight-loss profiles (with weight-loss profiles as inserts) of the prepared composites (a) and organic raw materials (b).

The thermal decomposition profiles of all four composites (Figure 3a) are similar, with a water desorption event between 30 °C and 100 °C, including three distinct thermal events with maxima at 317 °C (largest decomposition event), 355 °C (second largest event), and 410 °C. In contrast to the other composites, Al-B has a slightly lower second decomposition event with a maximum at 355 °C, where an increased decomposition maximum (410 °C) is slightly increased compared to that of the other composites. This aligns well with SCG (Figure 3b) with the maxima near 319 °C, 356 °C, and 410 °C.

Compared to the pristine materials prior to blending (Figure 3b), chitosan reveals a characteristic decomposition event with a maximum at 305 °C and a minor component with an event at approximately 405 °C. In SCG, the main decomposition events can be ascribed to (hemi)cellulose components (319 °C, onset at approximately 240 °C), whereas compounds such as lignins with greater stability may decompose near 400 °C–410 °C (Pereira et al., 2022; Brachi et al., 2021; Nepal et al., 2022). Generally, the most prominent peaks are ascribed to SCGs based on 80% SCG content. Examination of the weight loss profiles of both the composites Al-B and Fe-A each show ca. 27 wt% remaining. In comparison, Al-A (25.7 wt%) and Fe-B (24.7 wt%) had similar profiles, indicating that minor differences are noted between the composites with 1 or 5 wt% MO incorporation. While no consistent trend (Fe-B/Al-A vs. Fe-A/Al-B) related to the MO content was observed, this can fall within variations concerning metal oxide hydroxide content, along with water-content variability.

3.2 Adsorption studies

Based on trends in the conditions for aquatic environments, the background levels of common oxyanions rarely exceed 50 mg/L (nitrate) or 2 mg/L–5 mg/L (phosphate), while the sulfate levels can range between 75 mg/L and 6,000 mg/L or higher, depending on the aquatic environment (Solgi et al., 2024). The isotherm studies for Pi provide insights into the adsorption process (e.g., Langmuir or Freundlich isotherms), and they often far exceed the environmentally relevant levels (<5 mg/L–10 mg/L) to reach a maximum adsorption capacity. Hence, the maximum adsorption capacity may not be relevant in environmental samples, and uptake at such concentrations should be evaluated to address this limitation.

Preliminary screening experiments with a low-concentration (ca. 10 mg/L) Pi solution at pH 7 showed that unmodified SCG adsorbents (80% SCG and 20% chitosan) exhibit an uptake of ca. 0.15 mg/g of Pi. In comparison, MO incorporation increased the adsorption capacity to 0.81 mg/g (Al-A) and 0.72 mg/g (Al-B), whereas Fe-A (0.58 mg/g) and Fe-B (0.68 mg/g) materials are slightly less effective. The pellets reveal acceptable stability in solutions even with MO incorporation (see Table 1).

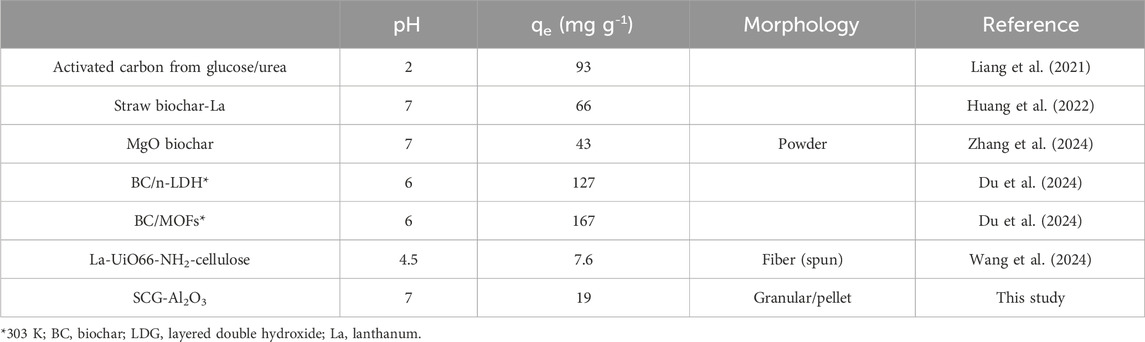

Table 1. Comparison of the maximum adsorption capacity of phosphate-selective adsorbents obtained from isotherm studies for phosphate at 298 K with sulfate, nitrate, and chloride as co-existing ions for subsequent selectivity studies.

To estimate the maximum adsorption capacity of the granular systems, adsorption isotherms were acquired for sulfate and phosphate (competitor ions, Figure 3) (Pincus et al., 2020) (see Supplementary Figures S1,S2) for phosphate and sulfate isotherms in laboratory samples without competitor ions. The Sips isotherm model (also known as the Langmuir–Freundlich combination isotherm) was used to estimate the maximum adsorption capacity (see Supplementary Table S1). The adsorption capacity of all the systems was variable: ca. 13 mg/g (Al-A), 15 mg/g (SCG), 17 mg/g (Fe-A), 18 mg/g (Fe-B), and 19 mg/g (Al-B), and Table 1 provides a brief comparison of the adsorption capacity of the selected adsorbents. The adsorption capacity of the pellet systems for sulfate was ca. 9 mg/g (Fe-B), 10 mg/g (Fe-A), 10 mg/g (SCG), 20 mg/g (Al-B), and 36 mg/g (Al-A). The Sips isotherm results reveal that the adsorbents display a heterogeneous surface site for contaminant binding according to the value of the exponential factor (ns > 1).

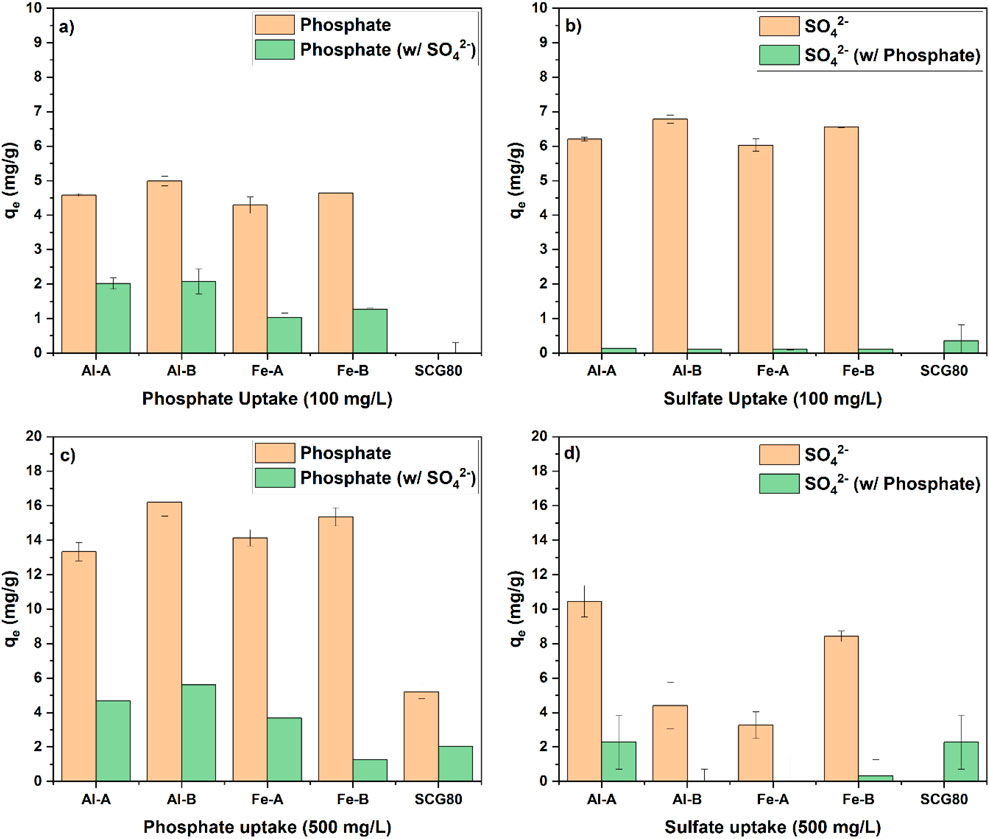

To gain insights into potential selectivity toward phosphate by the adsorbents, single-point adsorption analyses at equilibrium with a common competitor anion (sulfate) were conducted (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Single-point selectivity studies at pH 7 toward sulfate and phosphate at two concentrations: (a) comparison between phosphate uptake alone and phosphate uptake with sulfate as the competitor anion at 100 mg/L, (b) comparison between sulfate uptake alone and sulfate uptake with phosphate as the competitor anion at 100 mg/L, (c) comparison between phosphate uptake alone and phosphate uptake with sulfate as the competitor anion at 500 mg/L, and (d) comparison between sulfate uptake alone and sulfate uptake with phosphate as the competitor anion at 500 mg/L.

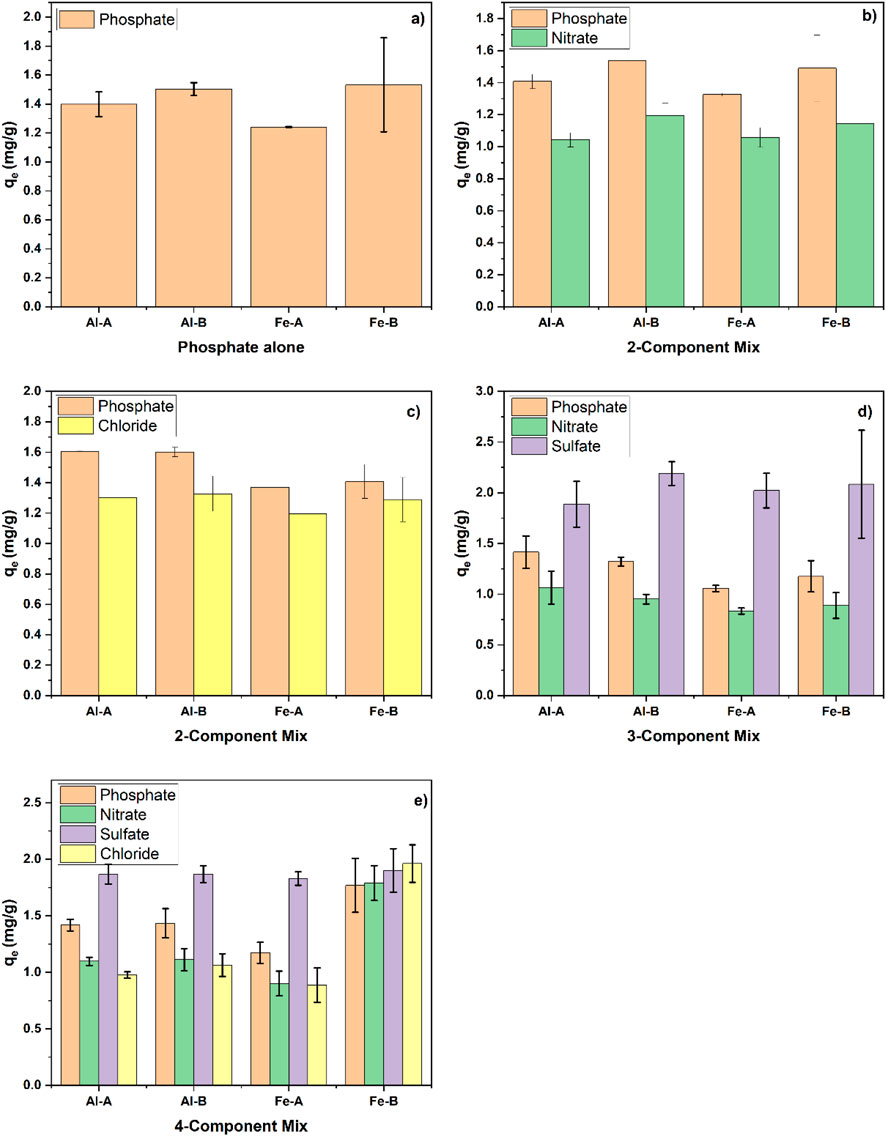

While phosphate uptake is reduced in the presence of sulfate, the uptake of sulfate is negligible in the presence of phosphate. Hence, Pi selectivity can be inferred based on thermodynamic grounds according to the differences in binding affinity and the adsorption capacity. An interesting comparison is achieved by comparing the adsorption capacity ratio. This is based on the qe of the target species in a single-ion solution compared to the qe of the target species when the competitor species is present. Although there is no specific value that indicates selectivity per se, it is posited that the adsorption capacity ratio can indicate thermodynamic variability between systems. In addition, the binary selectivity factor was selected because it compares the adsorption selectivity within the same system. The latter system contains the target and competitor ion species, which also utilize the uptake capacity as a metric of variability. Pi selectivity was calculated at 100 mg/L and expressed as the capacity ratio and binary selectivity factor αt/c (see Table 2; without SCG80, little-to-no uptake was observed compared to that in the other systems).

Table 2. Selectivity for phosphate in the presence of sulfate as a competitive anion at 100 mg/L (both anions) expressed as the adsorption capacity (AC) ratio and binary selectivity factor αt/c.

While the adsorption capacity ratio favors the Fe-modified granular adsorbents, the binary selectivity factor αt/c is the largest for the aluminum compounds. In general, all systems experience selectivity toward Pi. Considering the environmentally relevant conditions, it is pertinent to further analyze the selectivity at lower Pi levels (ca. 10 mg/L for all the anions to enable a better comparison; see Figure 5).

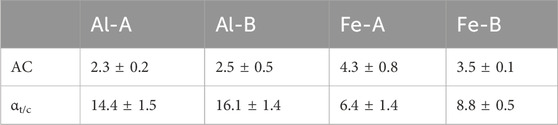

Figure 5. Adsorption experiments at 10 mg/L at pH 7 for each contaminant; (a) phosphate alone, (b) phosphate and nitrate, (c) phosphate and chloride, (d) phosphate, nitrate, and sulfate, and (e) all four anions (sulfate, phosphate, chloride, and nitrate).

For the Pi adsorption capacity at an initial Pi concentration of ca. 10 mg/L, the uptake is ca. 1.2 mg/g –1.5 mg/g for all the systems (see Figure 5a). This baseline level of phosphate adsorption can assist in interpreting the effects of competitor anions. In the presence of nitrate (Figure 5b), no decrease in Pi uptake is observed, and nitrate removal can also be measured. A similar result is observed in the presence of chloride (Figure 4c). Accordingly, nitrate does not have any appreciable effect on Pi uptake. Hence, a ternary anion system (phosphate, nitrate, and sulfate; see Figure 5d) was investigated instead of a binary phosphate–sulfate system (especially when phosphate selectivity was established; see Figure 4). It is noteworthy that while the approximate Pi uptake (cf. Figure 5a) of the single-component system was reached, ca. 2 mg/g sulfate and 1 mg/g nitrate were additionally adsorbed. In addition to the results of the ternary system with respect to the adsorption capacity, a quaternary mix of chloride, phosphate, nitrate, and sulfate (see Figure 5e) resulted in uptake of all four species, while the Pi uptake remained more or less similar to that of the single-component system. Based on these results, it can be inferred that different adsorption sites (as supported by the Sips heterogeneity factor that deviates from unity) contribute to the adsorption process, where one specific site binds with Pi and other sites can bind with other oxyanions. Once a sufficiently high Pi concentration is reached, the other sites may become occupied (see Figures 4a,b). It is posited that sulfate and phosphate first occupy different adsorption sites, where sulfate preferentially adsorbs onto amine groups over phosphate, and other sites, such as MO domains, favor binding of phosphate (Nuryono et al., 2025). Considering the slightly increased chitosan content in Al-B and Fe-B composites compared to Al-A and Fe-A composites, this may account for the slightly increased adsorption capacity toward anions in Al-B and Fe-B composites over the corresponding metal oxide-A composites. Despite this, the overall selectivity toward phosphate over sulfate (see Figure 4b) was demonstrated.

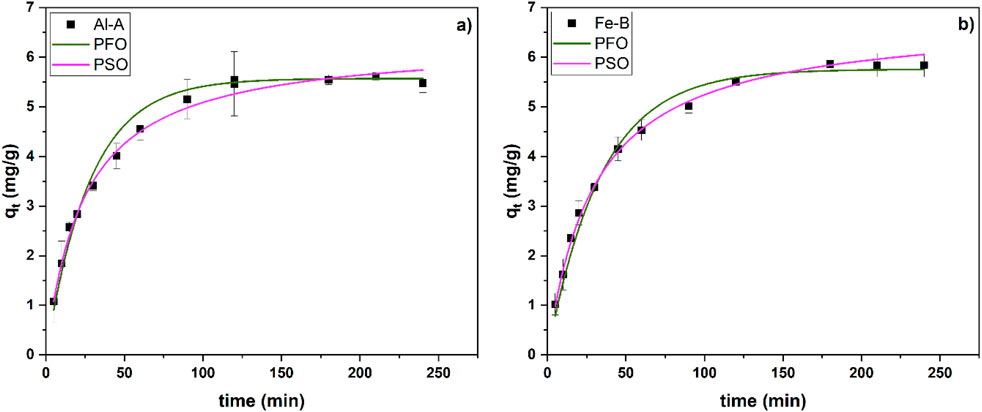

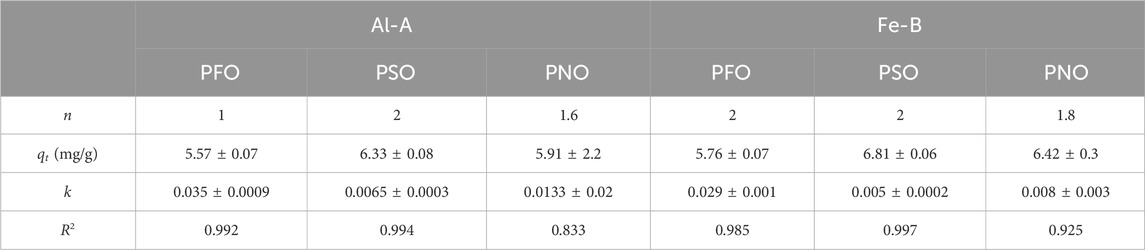

Based on the adsorption capacity and lower standard deviation (cf. Table 2) regarding the selectivity investigation, two systems (Al-A and Fe-B) were chosen for further investigation. For kinetic studies, both systems (see Figure 6; Table 3) showed similar kinetic profiles and fit the PFO and PSO kinetic models. To further evaluate the adsorption kinetics, data fitting according to the PNO model was carried out (see Supplementary Figure S3).

Figure 6. Kinetic profiles of phosphate adsorption at pH 7 and with C0 of Pi at 100 mg/L, ca. 15 pellets, onto Al-A (a) and Fe-B (b).

Table 3. PFO and PSO kinetic profile data for Al-A and Fe-B. k is expressed in min-1 for the PFO kinetic rate constant and g mg-1 min-1 for the PSO kinetic rate constant.

While the adsorption rate reached a steady state after ca. 100 min for both types of composites (-A and -B types), both kinetic models (PSO and PFO) showed similarly acceptable fits. Hence, the PNO model was used to shed light on the adsorption process, resulting in an overall value for n of 1.6 and 1.8 for Al-A and Fe-B, respectively. Notably, the R2 value did not reach the values for the fits of the PSO and PFO models, whereas the determined qe values align closely with the expected empirical data after reaching equilibrium. Furthermore, the IPD model can be used to further investigate the adsorption parameters. However, its application and introduction of the constant “C” to determine the boundary layer thickness are contested. Instead, the original Weber–Morris equation (qt = kt0.5) was adopted here to avoid over-parameterization and ensure direct comparison between the samples (see Supplementary Figure S4) (Wang and Guo, 2022; Chu et al., 2025). Notably, a rate constant of ca. 0.56 mg/(g min0.5) for Al-A and 0.51 mg/(g min0.5) for Fe-B was observed based on the IPD model. Specifically, the low values for the equilibrium constant K (Sips) and the low rate constant (k) lends credence to anion exchange and physisorption via electrostatic interactions with the active sites of chitosan. However, another report indicates that metal (hydr)oxides may also form inner-sphere complexes with oxyanions, which may account for the selectivity toward phosphate according to the HSAB principle (Pincus et al., 2020).

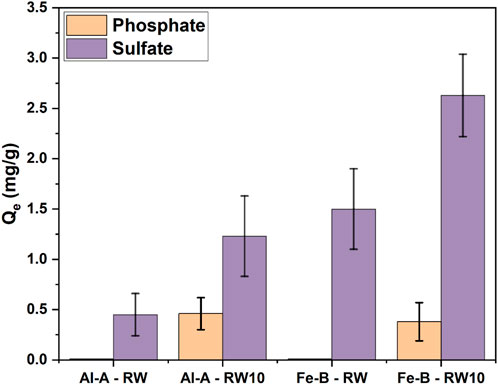

Similarly, the Al-A and Fe-B composites were utilized to investigate Pi selective adsorption in an environmental river water sample (Figure 7). It must be noted that the collected river water samples were from the South Saskatchewan River (collected from Saskatoon) and were spiked with ca. 10 mg/L Pi solution without any further pH adjustments. The river water has a sulfate level of ca. 80 mg/L and a pH near 8, which depend on seasonal variations.

Figure 7. Sulfate and phosphate uptake capacity in (spiked) river water (pH 8) with the control (denoted as RW) and with 10 mg/L spiked phosphate concentration in river water (denoted as RW10).

Naturally, both RW samples without phosphate-spiking showed solely sulfate uptake. Once ca. 10 mg/L phosphate was present, phosphate was co-adsorbed with sulfate onto the granular adsorbent materials. While the collected river water sample had no appreciable phosphate content, approximately 80 mg/L sulfate was measured. Sulfate removal from river water alone showed uniquely lower sulfate adsorption (ca. 0.5 mg/g compared to ca. 1.2 mg/g for Al-A; ca. 1.5 mg/g compared to 2.6 mg/g for Fe-B) than with phosphate-spiked water. The Pi adsorption capacity of spiked river water was ca. 0.5 mg/g and 0.4 mg/g for Al-A and Fe-B, respectively. In contrast to that shown in Figures 4,5, , river water contains a variety of mono- and divalent cations and variable anion concentrations (e.g., 10 mg/L phosphate after spiking vs. 80 mg/L sulfate). While the increased sulfate concentration (in contrast to Figure 5) should have increased sulfate adsorption, no appreciable increase occurred. This is most likely due to the matrix effect and is influenced by the composition and chemical characteristics of river water. Specifically, upon comparison of the XRD spectra of pristine iron oxide and the adsorbents Fe-A and Fe-B with the spent Fe-B adsorbents after adsorption from a complex matrix (river water; Supplementary Figure S5a), two main observations can be made. First, iron oxide was identified within the pellets, whereas a new peak at a 2θ-value of 26.90° appeared (absent in the pristine materials, Supplementary Table S3, ICSD collection codes 82902 and 80554) in the spent adsorbent, indicating a potential iron phosphate species in addition to iron oxide. In contrast, aluminum oxide appears mostly amorphous (Supplementary Figure S5b), and a new peak at a 2θ-value of 29.6° appeared (absent from pristine materials), which can similarly be related to the formation of hydrated sodium aluminum phosphate (ICSD collection code 137700), whereas no other characteristic peaks could be assigned.

4 Conclusion

In this study, granular adsorbents with 80% SCGs, chitosan (19% or 15%), and Fe(III) or Al(III) oxide at different ratios (1% or 5%) were composited and compared to adsorbents without MO for the selective adsorption of Pi in sulfate-laden water. The materials characterization supports the formation of composites upon physical blending of the constituents, where chitosan served as the binder. There are no significant changes in the chemical shifts or NMR spectral signatures that can be attributed to the incorporation of MOs in the adsorbents, compared with the raw materials. The thermal decomposition events of the pristine materials resemble those of the four different composite adsorbents at the levels of MO incorporation utilized herein. The TGA results provide support that the adsorbents are physical blends of materials without covalent bond formation.

Equilibrium uptake isotherms at pH 7 for Pi and ambient pH for SO42- showed ca. 13 mg/g–20 mg/g Pi and ca. 9 mg/g–36 mg/g SO42- adsorption for single-component anion solutions. In binary mixtures of sulfate (100 mg/L) and phosphate (500 mg/L), the presence of sulfate reduced the phosphate uptake, while the presence of phosphate resulted in no appreciable uptake of sulfate. Hence, the adsorbents provide appreciable phosphate selectivity. Among the systems with MOs, all systems showed preferential Pi adsorption in binary, ternary, and quaternary component (anion solutions) mixtures with Al-A and Al-B that reveal greater Pi selectivity. In mixed-component solutions at environmentally relevant levels (10 mg/L Pi), the uptake of phosphate remained constant despite the presence of other anions, which were also appreciably co-adsorbed by the adsorbents. This showed that the various composite adsorbent systems are selective toward Pi but also possess heterogeneous active sites that facilitate non-competitive binding. It can be inferred that one active site binds to phosphate, while the other active sites adsorb the other oxyanions. Furthermore, experiments conducted with river water spiked with Pi reveal greater selectivity of the MO-based adsorbents with phosphate but with low adsorption capacity (ca. 0.5 mg/g for Al-A and 0.4 mg/g for Fe-B), which is attributed to the role of the competitor anion effects.

This study highlights the preparation of sustainable and low-cost adsorbents with 80% SCG, 15%–19% chitosan, and variable MO (1% or 5%). The Pi adsorption selectivity occurs at environmentally relevant levels, even in the presence of sulfate anions. Furthermore, this study also showed that once the phosphate-selective sites are exhausted, the overall salinity is decreased through co-adsorption of competitor anions without any detrimental effect on the Pi adsorption capacity. This study reports on several phosphate-selective granular adsorbent systems with excellent adsorption properties in the presence of competitor sulfate anions. However, some limitations remain that can be addressed through future work, which include a systematic evaluation of the thermodynamic and kinetic parameters in different environmental matrices to advance practical applications.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

BS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft. AF: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – review and editing. BB: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – review and editing. LW: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review and editing.

Funding

The authors declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. L.D.W. acknowledges the support provided by the Government of Canada through the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC Discovery Grant Number: RGPIN 04315-2021).

Acknowledgements

The Saskatchewan Structural Science Centre (SSSC) is acknowledged for providing facilities to conduct this research. The authors acknowledge that this work was carried out in Treaty 6 Territory and the Homeland of the Métis. As such, they pay their respect to the First Nations and Métis ancestors of this place and reaffirm their relationship with one another. Aauyshi Chauhan is acknowledged for adsorbent preparation and for providing the preliminary measurements as part of an undergraduate research project.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fenvc.2025.1713367/full#supplementary-material

References

Abin-Bazaine, A., Campos Trujillo, A., and Olmos-Marquez, M. (2022). Adsorption isotherms: enlightenment of the phenomenon of adsorption. In: Wastewater treatment. London, UK: IntechOpen. doi:10.5772/intechopen.104260

S. Ahmed, IkramS., S. Ahmed, and S. Ikram (2017). Chitosan. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley and Sons, Inc. doi:10.1002/9781119364849

Ajmal, Z., Muhmood, A., Usman, M., Kizito, S., Lu, J., Dong, R., et al. (2018). Phosphate removal from aqueous solution using iron oxides: adsorption, desorption and regeneration characteristics. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 528, 145–155. doi:10.1016/j.jcis.2018.05.084

Alvares, E., Tantoro, S., Wijaya, C. J., Cheng, K.-C., Soetaredjo, F. E., Hsu, H.-Y., et al. (2023). Preparation of MIL100/MIL101-Alginate composite beads for selective phosphate removal from aqueous solution. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 231, 123322. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.123322

Atalla, R., and VanderHart, D. (1999). The role of solid state NMR spectroscopy in studies of the nature of native celluloses. Solid State Nucl. Magn. Reson. 15 (1), 1–19. doi:10.1016/S0926-2040(99)00042-9

Blaney, L., Cinar, S., and Sengupta, A. (2007). Hybrid anion exchanger for trace phosphate removal from water and wastewater. Water Res. 41 (7), 1603–1613. doi:10.1016/j.watres.2007.01.008

Brachi, P., Santes, V., and Torres-Garcia, E. (2021). Pyrolytic degradation of spent coffee ground: a thermokinetic analysis through the dependence of activation energy on conversion and temperature. Fuel 302, 120995. doi:10.1016/j.fuel.2021.120995

Bui, N. T., Steiger, B. G. K., and Wilson, L. D. (2024). A route to selective arsenate adsorption in phosphate solutions via ternary metal biopolymer composites. Appl. Sci. 14 (17), 7577. doi:10.3390/app14177577

Carruthers-Taylor, T., Banerjee, J., Little, K., Wong, Y. F., Jackson, W. R., and Patti, A. F. (2020). Chemical nature of spent coffee grounds and husks. Aust. J. Chem. 73 (12), 1284–1291. doi:10.1071/CH20189

Chen, X., Wang, Y., Bai, Z., Ma, L., Strokal, M., Kroeze, C., et al. (2022). Mitigating phosphorus pollution from detergents in the surface waters of China. Sci. Total Environ. 804, 150125. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.150125

Chu, K. H., Hashim, M. A., Zawawi, M. H., and Bollinger, J.-C. (2025). The weber–morris model in water contaminant adsorption: shattering long-standing misconceptions. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 13 (4), 117266. doi:10.1016/j.jece.2025.117266

Crini, G. (2005). Recent developments in polysaccharide-based materials used as adsorbents in wastewater treatment. Prog. Polym. Sci. 30 (1), 38–70. doi:10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2004.11.002

Desbrières, J., and Guibal, E. (2018). Chitosan for wastewater treatment. Polym. Int. 67 (1), 7–14. doi:10.1002/pi.5464

Du, M., Sun, Z., Liu, Y., Wang, A., Zhang, Y., Chen, Z., et al. (2024). Selective phosphate adsorption using topologically regulated binary-defect metal–organic frameworks: essential role of interfacial electron mobility. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 16 (11), 14333–14344. doi:10.1021/acsami.4c00035

Geies, A., Abdul-Moneim, M., and Farghaly, S. (2018). Utilization of anion exchange resins: amberlyst A21 for sulfate reduction in drinking ground water and its characterization. Int. Conf. Chem. Environ. Eng. 9 (6), 273–294. doi:10.21608/iccee.2018.34669

Guimarães, D., and Leão, V. A. (2014). Batch and fixed-bed assessment of sulphate removal by the weak base ion exchange resin amberlyst A21. J. Hazard. Mater. 280, 209–215. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2014.07.071

Hamad, H. N., and Idrus, S. (2022). Recent developments in the application of bio-waste-derived adsorbents for the removal of methylene blue from wastewater: a review. Polym. (Basel) 14 (4), 783. doi:10.3390/polym14040783

Huang, Y., He, Y., Zhang, H., Wang, H., Li, W., Li, Y., et al. (2022). Selective adsorption behavior and mechanism of phosphate in water by different lanthanum modified biochar. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 10 (3), 107476. doi:10.1016/j.jece.2022.107476

Ibnul, N. K., and Tripp, C. P. (2022). A simple solution to the problem of selective detection of phosphate and arsenate by the molybdenum blue method. Talanta 238, 123043. doi:10.1016/j.talanta.2021.123043

Bureau of Indian Standards (BIS) (2003). IS 3025 (part 24): Method of sampling and test (physical and chemical) for water and wastewater, Part 24: Sulphates (First Revision). Bureau: Bureau of Indian Standards. Available online at: https://archive.org/details/gov.law.is.3025.24.1986 (Accessed April 25, 2018).

Jiang, S., Wu, X., Du, S., Wang, Q., and Han, D. (2022). Are UK Rivers getting saltier and more alkaline? Water 14 (18), 2813. doi:10.3390/w14182813

Kanai, N., Yoshihara, N., and Kawamura, I. (2019). Solid-state NMR characterization of triacylglycerol and polysaccharides in coffee beans. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 83 (5), 803–809. doi:10.1080/09168451.2019.1571899

Kheilkordi, Z., Mohammadi Ziarani, G., Mohajer, F., Badiei, A., and Varma, R. S. (2022). Waste-to-Wealth transition: application of natural waste materials as sustainable catalysts in multicomponent reactions. Green Chem. 24 (11), 4304–4327. doi:10.1039/D2GC00704E

Kögel-Knabner, I. (2002). The macromolecular organic composition of plant and microbial residues as inputs to soil organic matter. Soil Biol. Biochem. 34 (2), 139–162. doi:10.1016/S0038-0717(01)00158-4

Kostryukov, S. G., Petrov, P. S., Tezikova, V. S., Masterova, Y. Y., Idris, T. J., and Kostryukov, N. S. (2021). Determination of wood composition using solid-state 13C NMR spectroscopy. Cellul. Chem. Technol. 55 (5–6), 461–468. doi:10.35812/CelluloseChemTechnol.2021.55.42

Li, K., Li, P., Cai, J., Xiao, S., Yang, H., and Li, A. (2016). Efficient adsorption of both methyl Orange and chromium from their aqueous mixtures using a Quaternary ammonium salt modified chitosan magnetic composite adsorbent. Chemosphere 154, 310–318. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2016.03.100

Liang, H., Zhang, H., Wang, Q., Xu, C., Geng, Z., She, D., et al. (2021). A novel glucose-based highly selective phosphate adsorbent. Sci. Total Environ. 792, 148452. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.148452

Liu, J., Elliott, J. A., Wilson, H. F., Macrae, M. L., Baulch, H. M., and Lobb, D. A. (2021). Phosphorus runoff from Canadian agricultural land: a cross-region synthesis of edge-of-field results. Agric. Water Manag. 255, 107030. doi:10.1016/j.agwat.2021.107030

Mayer, B. K., Gerrity, D., Rittmann, B. E., Reisinger, D., and Brandt-Williams, S. (2013). Innovative strategies to achieve low total phosphorus concentrations in high water flows. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 43 (4), 409–441. doi:10.1080/10643389.2011.604262

Mekonnen, M. M., and Hoekstra, A. Y. (2018). Global anthropogenic phosphorus loads to freshwater and associated Grey water footprints and water pollution levels: a high-resolution global study. Water Resour. Res. 54 (1), 345–358. doi:10.1002/2017WR020448

Mohamed, M. H., Udoetok, I. A., Solgi, M., Steiger, B. G. K., Zhou, Z., and Wilson, L. D. (2022). Design of sustainable biomaterial composite adsorbents for point-of-use removal of lead ions from water. Front. Water 4, 739492. doi:10.3389/frwa.2022.739492

Namasivayam, C., and Sangeetha, D. (2008). Application of coconut coir pith for the removal of sulfate and other anions from water. Desalination 219 (1–3), 1–13. doi:10.1016/j.desal.2007.03.008

Nehls, I., Wagenknecht, W., Philipp, B., and Stscherbina, D. (1994). Characterization of cellulose and cellulose derivatives in solution by high resolution 13C-NMR spectroscopy. Prog. Polym. Sci. 19 (1), 29–78. doi:10.1016/0079-6700(94)90037-X

Nepal, R., Kim, H. J., Poudel, J., and Oh, S. C. (2022). A study on torrefaction of spent coffee ground to improve its fuel properties. Fuel 318, 123643. doi:10.1016/j.fuel.2022.123643

Nuryono, N., Sukamto, S., Kunarti, E. S., Krisbiantoro, P. A., Wan Abdullah, W. N., and Kamiya, Y. (2025). Magnetically separable silica-chitosan hybrids for efficient phosphate adsorption in aqueous solution. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 11, 101100. doi:10.1016/j.cscee.2025.101100

Okazaki, T., Kuramitz, H., Hata, N., Taguchi, S., Murai, K., and Okauchi, K. (2015). Visual colorimetry for determination of trace arsenic in groundwater based on improved molybdenum blue spectrophotometry. Anal. Methods 7 (6), 2794–2799. doi:10.1039/C4AY03021D

Owodunni, A. A., Ismail, S., Kurniawan, S. B., Ahmad, A., Imron, M. F., and Abdullah, S. R. S. (2023). A review on revolutionary technique for phosphate removal in wastewater using green coagulant. J. Water Process Eng. 52, 103573. doi:10.1016/j.jwpe.2023.103573

Park, S., Baker, J. O., Himmel, M. E., Parilla, P. A., and Johnson, D. K. (2010). Cellulose crystallinity index: measurement techniques and their impact on interpreting cellulase performance. Biotechnol. Biofuels 3 (1), 10. doi:10.1186/1754-6834-3-10

Pearson, R. G. (1963). Hard and soft acids and bases. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 85 (22), 3533–3539. doi:10.1021/ja00905a001

Pereira, L. H., Catelani, T. A., Costa, É. D. ’M., Garcia, J. S., and Trevisan, M. G. (2022). Coffee adulterant quantification by derivative thermogravimetry and chemometrics analysis. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 147 (13), 7353–7362. doi:10.1007/s10973-021-11016-6

Pincus, L. N., Rudel, H. E., Petrović, P. V., Gupta, S., Westerhoff, P., Muhich, C. L., et al. (2020). Exploring the mechanisms of selectivity for environmentally significant oxo-anion removal during water treatment: a review of common competing oxo-anions and tools for quantifying selective adsorption. Environ. Sci. Technol. 54 (16), 9769–9790. doi:10.1021/acs.est.0c01666

Quintana-Baquedano, A. A., Sanchez-Salas, J. L., and Flores-Cervantes, D. X. (2023). A review of technologies for the removal of sulfate from drinking water. Water Environ. J. 37, 718–728. doi:10.1111/wej.12889

Radwan-Pragłowska, J., Piątkowski, M., Deineka, V., Janus, Ł., Korniienko, V., Husak, E., et al. (2019). Chitosan-based bioactive hemostatic agents with antibacterial properties—synthesis and characterization. Molecules 24 (14), 2629. doi:10.3390/molecules24142629

Roy, T., Wisser, D., Rivallan, M., Valero, M. C., Corre, T., Delpoux, O., et al. (2021). Phosphate adsorption on γ-Alumina: a surface complex model based on surface characterization and zeta potential measurements. J. Phys. Chem. C 125 (20), 10909–10918. doi:10.1021/acs.jpcc.0c11553

Shan, X., Yang, L., Zhao, Y., Yang, H., Xiao, Z., An, Q., et al. (2022). Biochar/Mg-Al spinel carboxymethyl Cellulose-La hydrogels with cationic polymeric layers for selective phosphate capture. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 606, 736–747. doi:10.1016/j.jcis.2021.08.078

Sips, R. (1948). On the structure of a catalyst surface. J. Chem. Phys. 16 (5), 490–495. doi:10.1063/1.1746922

Solgi, M., Tabil, L. G., and Wilson, L. D. (2020). Modified biopolymer adsorbents for column treatment of sulfate species in saline aquifers. Mater. (Basel). 13 (10), 2408. doi:10.3390/ma13102408

Solgi, M., Steiger, B. G. K., and Wilson, L. D. (2023). A fixed-bed column with an agro-waste biomass composite for controlled separation of sulfate from aqueous media. Separations 10 (4), 262. doi:10.3390/separations10040262

Solgi, M., Mohamed, M. H., Udoetok, I. A., Steiger, B. G. K., and Wilson, L. D. (2024). Evaluation of a granular Cu-Modified chitosan biocomposite for sustainable sulfate removal from aqueous media: a batch and fixed-bed column study. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 260, 129275. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.129275

Sousa, A. F. de, Braga, T. P., Gomes, E. C. C., Valentini, A., and Longhinotti, E. (2012). Adsorption of phosphate using mesoporous spheres containing iron and aluminum oxide. Chem. Eng. J. 210, 143–149. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2012.08.080

Steiger, B. G. K., Zhou, Z., Anisimov, Y. A., Evitts, R. W., and Wilson, L. D. (2023). Valorization of agro-waste biomass as composite adsorbents for sustainable wastewater treatment. Ind. Crops Prod. 191, 115913. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2022.115913

Steiger, B. G. K., Bui, N. T., Babalola, B. M., and Wilson, L. D. (2024). Eggshell incorporated agro-waste adsorbent pellets for sustainable orthophosphate capture from aqueous media. RSC Sustain 2 (5), 1498–1507. doi:10.1039/D3SU00415E

Taleb, F., Ammar, M., Mosbah, M., Salem, R., and Moussaoui, Y. (2020). Chemical modification of lignin derived from spent coffee grounds for methylene blue adsorption. Sci. Rep. 10 (1), 11048. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-68047-6

Tseng, R.-L., Wu, P.-H., Wu, F.-C., and Juang, R.-S. (2014). A convenient method to determine kinetic parameters of adsorption processes by nonlinear regression of pseudo-nth-order equation. Chem. Eng. J. 237, 153–161. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2013.10.013

Usman, M. O., Aturagaba, G., Ntale, M., and Nyakairu, G. W. (2022). A review of adsorption techniques for removal of phosphates from wastewater. Water Sci. Technol. 86 (12), 3113–3132. doi:10.2166/wst.2022.382

Venegas-García, D. J., Steiger, B. G. K., and Wilson, L. D. (2023). A pyridinium-modified chitosan-based adsorbent for arsenic removal via a coagulation-like methodology. RSC Sustain 1 (5), 1259–1269. doi:10.1039/D3SU00130J

Wang, J., and Guo, X. (2022). Rethinking of the intraparticle diffusion adsorption kinetics model: interpretation, solving methods and applications. Chemosphere 309, 136732. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2022.136732

Wang, C., Huang, K., Mao, L., Liang, X., and Wang, Z. (2024). Incorporation of La/UiO66-NH2 into cellulose fiber for efficient and selective phosphate adsorption. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 12 (2), 112257. doi:10.1016/j.jece.2024.112257

William Kajjumba, G., Emik, S., Öngen, A., Kurtulus Özcan, H., and Aydın, S. (2019). Modelling of adsorption kinetic processes—errors, theory and application. In: Advanced sorption process applications. London, UK: IntechOpen. doi:10.5772/intechopen.80495

Wu, B., Wan, J., Zhang, Y., Pan, B., and Lo, I. M. C. (2020). Selective phosphate removal from water and wastewater using sorption: process fundamentals and removal mechanisms. Environ. Sci. Technol. 54 (1), 50–66. doi:10.1021/acs.est.9b05569

Xu, H., Xu, D. C., and Wang, Y. (2017). Natural indices for the chemical hardness/softness of metal cations and ligands. ACS Omega 2 (10), 7185–7193. doi:10.1021/acsomega.7b01039

Zhang, X., Xiong, Y., Wang, X., Wen, Z., Xu, X., Cui, J., et al. (2024). MgO-Modified biochar by modifying Hydroxyl and amino groups for selective phosphate removal: insight into phosphate selectivity adsorption mechanism through experimental and theoretical. Sci. Total Environ. 918, 170571. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.170571

Zuluaga, R., Hoyos, C. G., Velásquez-Cock, J., Vélez-Acosta, L., Palacio Valencia, I., Rodríguez Torres, J. A., et al. (2024). Exploring spent coffee grounds: comprehensive morphological analysis and chemical characterization for potential uses. Molecules 29 (24), 5866. doi:10.3390/molecules29245866

Keywords: river water, environmental matrix, adsorption, granular adsorbents, spent coffee grounds, chitosan

Citation: Steiger BGK, Faleye AC, Babalola BM and Wilson LD (2025) Selective phosphate uptake in the presence of sulfate with granular spent coffee grounds-based adsorbents via metal oxide modification. Front. Environ. Chem. 6:1713367. doi: 10.3389/fenvc.2025.1713367

Received: 25 September 2025; Accepted: 14 November 2025;

Published: 05 December 2025.

Edited by:

Hai Nguyen Tran, Duy Tan University, VietnamReviewed by:

Van Thuan Le, Duy Tan University, VietnamQuoc-An Trieu, Nguyen Tat Thanh University, Vietnam

Copyright © 2025 Steiger, Faleye, Babalola and Wilson. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Lee D. Wilson, bGVlLndpbHNvbkB1c2Fzay5jYQ==

†ORCID: Bernd G. K. Steiger, orcid.org/0000-0001-7099-4934; Bolanle M. Babalola, orcid.org/0000-0001-7428-1317; Lee D. Wilson, orcid.org/0000-0002-0688-3102

Bernd G. K. Steiger

Bernd G. K. Steiger Adekunle C. Faleye2

Adekunle C. Faleye2 Bolanle M. Babalola

Bolanle M. Babalola Lee D. Wilson

Lee D. Wilson