- Emmett Interdisciplinary Program in Environment and Resources, School of Earth, Energy, and Environmental Sciences, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, United States

Seafood is the world’s most traded food commodity, and the international trade in seafood is promoted as a development strategy in low-income coastal communities across the globe. However, the seafood trade can drive negative social and environmental impacts in fishing communities, and whether the benefits of trade actually reach fishers is a subject of ongoing scholarship. Furthermore, scholars and policymakers have tended to treat fishing communities as homogeneous, assuming that trade policies will impact all members equally. Yet individual community members have different roles, statuses, and entitlements according to their intersecting identities, meaning that different fishers will be differently impacted by the seafood trade. In particular, women occupy different positions than men in seafood value chains and in fishing communities. There are also important within-group differences among men and among women depending on their nationality, marital status, and other identity markers. Through 205 surveys, 54 interviews, and ethnographic field methods conducted in fifteen rural Palauan fishing communities between November 2019 and March 2020, this case study of the sea cucumber trade in Palau brings together theories of gender, intersectionality, and access to answer the question, “How are the harms and benefits of the seafood trade distributed in fishing communities?” In this case, men benefited more than women from the export of sea cucumbers by leveraging access to technology; knowledge; and authority, and the trade depleted resources relied on primarily by women for their food security and livelihoods. An intersectional analysis revealed that marital status and nationality determined access among women, with married women having greater access than unmarried women and immigrant women having greater access than immigrant men, demonstrating the importance of intersectionality as an analytical tool.

Introduction

As the global seafood trade rapidly expands (Gephart and Pace, 2015), the export of high-value fisheries products from coastal communities to luxury markets is promoted as a vehicle for poverty alleviation (Barclay et al., 2019). Whether the benefits of trade actually reach fishers is a subject of ongoing scholarship (e.g., Béné et al., 2010; Crona et al., 2015; O’Neill et al., 2018), and case studies from across the globe show that trade can have harmful impacts on fishing communities and their resources (e.g., Porter et al., 2008; Campling, 2012; Fabinyi et al., 2018; Nolan, 2019). Moreover, scholars and policymakers have tended to treat fishing communities as homogenous groups, assuming that policies will affect all fishing community members equally (Agrawal et al., 1997; Agrawal and Gibson, 1999, 2001; Allison and Ellis, 2001). But we know that fishing communities are diverse across many dimensions, including gender (Harper et al., 2020), ethnicity (Lau and Scales, 2016), power and class (Colwell et al., 2017), religious denomination and place of birth (Rohe et al., 2018), and nationality (Yingst and Skaptadóttir, 2018), as well as other identity markers, which intersect with one another (Hooks, 1984; Collins, 1986; Crenshaw, 1989, 1991). Fishers’ identities shape their access to marine resources and their interactions with globalized seafood markets (Porter et al., 2008; Fabinyi et al., 2018; O’Neill et al., 2018). In this paper, I examine whether and how different fishers are impacted differently by the seafood trade according to their intersecting identities.

The trade in dried sea cucumbers, also known as bêche-de-mer, epitomizes many of the social and environmental challenges of high-value export fisheries. Driven by the growing demand for luxury seafood products in China (Fabinyi, 2012; Purcell et al., 2014), cases of “boom-bust” fishery collapse have been documented across the Pacific and Indian Oceans, in a pattern of serial depletion (Anderson et al., 2011; Purcell et al., 2013; Eriksson et al., 2015). There has been rapid geographic expansion to meet increasing demand from China, with sea cucumber fisheries serving the Chinese market now operating within countries cumulatively spanning over 90% of the world’s tropical coastlines (Eriksson et al., 2015), with the Western Central Pacific being the most important exporting region (Conand, 2017). Sea cucumbers are highly vulnerable to overfishing due to their slow growth, late age of maturity, ease of capture, and reproductive strategy (Uthicke et al., 2004). Markets for new and lower-value species, such as Stichopus herrmanni; Bodaschia vitiensis; and Holothuria fuscopuntata, are growing as the highest-value species are becoming depleted at an alarming rate (Purcell et al., 2013, 2018).

The sea cucumber trade may also fail to deliver the hoped-for economic development. Sea cucumber fisheries are generally characterized by patron-client relationships, defined by socioeconomic asymmetries (Ferrol-Schulte et al., 2014), which result in disproportionate wealth capture by exporters and other middlemen, particularly for the highest-value species (Purcell et al., 2017). Where targeted species are important for local consumption and not easily substituted, export can exacerbate food security challenges for poor community members by increasing prices (Crona et al., 2016). And the rapid overexploitation of fisheries resources threatens fishers’ livelihoods and ways of life in the long-term (Christensen, 2011).

Furthermore, the seafood trade does not impact all fishers equally (Crona et al., 2016). For instance, there is evidence that men displace women in areas where locally consumed resources become commoditized, limiting women’s access to trade benefits (Porter et al., 2008; Pinca et al., 2010; Williams, 2015). We therefore cannot understand the processes that shape relations to the seafood trade without first understanding the identities that shape fishers’ relations to one another and to marine resources.

Gender is a central organizing identity for marine resource use globally and in the Pacific. In many Pacific island nations, women are the customary harvesters of sea cucumbers and dominate local markets for sea cucumber products (Matthews, 1991; Williams, 2015). Using minimal technologies to collect sea cucumbers in the nearshore environment at low tide, a fishing practice known as “gleaning,” women in the Pacific contribute critically to household food security and income (Weeratunge et al., 2010; Rohe et al., 2018; De Guzman, 2019). Across the Pacific, women’s harvesting activities, including gleaning, account for approximately 56% of the total catch in small-scale fisheries (Harper et al., 2013).

Yet women are frequently overlooked in fisheries research (Kleiber et al., 2015). As a result, we understand little about how women are impacted by the seafood trade. Recent reviews have highlighted the need to include gender as a key variable in our understanding of fishing communities and economies, as women participate in—and often dominate—many aspects of the seafood production chain (Bennett, 2005; Williams, 2008; Weeratunge et al., 2010; Harper et al., 2013, 2020; Kleiber et al., 2015). In the context of the ever-expanding reach of the global seafood trade and global commitments to achieving gender equality (UN General Assembly, 2015), it is important to examine not only the roles women play in seafood value chains, but also the role of the global seafood trade in shaping gender inequalities among fishers.

Critically, gender is not the only—or necessarily the principal—identity that shapes fishers’ relations to marine resources. In this analysis, I also examine how two locally relevant identities, nationality and marital status, intersect with gender to produce unique relations to the seafood trade in Palau.

Gender and Intersectionality

The terms “gender” and “sex” mean different things to different feminist theorists, and neither is easy or straightforward to characterize. In this paper, I use “gender” to refer to sociocultural, political, and behavioral attributes that are typically associated with “men” and “women”—though there is significant variation and complexity beyond this binary—in contrast to “sex,” which refers to biological attributes such as chromosomes and reproductive organs. Constructions of gender are neither uniform across societies nor historically static, and they interact with other identity markers, such as ethnicity, race, and age, to produce unique positions within the social hierarchy (Crenshaw, 1989, 1991). It should be noted that the dominant binary construction of gender is itself culturally contextualized, and many Pacific cultures have customarily recognized gender variance including third gender constructions (Presterudstuen, 2019).

Feminist political ecologists have examined the importance of nature in producing gender and gendered power relations (Gururani, 2002; Harris, 2006; Nightingale, 2006, 2011), arguing that gender and other social identities emerge through “everyday, embodied activities” such as agro-forestry (Nightingale, 2011). Gendered power relations are revealed not only in the division of labor and resources between women and men, but also in the ideas and representations of women and men as having different abilities, attitudes, desires, personality traits, behavior patterns, etc., often in opposition to one another (Agarwal, 1997). Gendered power relations are constructed through differentiated relations with the environment, based on gendered work patterns, access to and rights over resources, cultural concepts regarding masculinity and femininity, and belief systems (e.g., Singh and Burra, 1993; Krishna, 1998; Vedavalli and Anil Kumar, 1998; Sillitoe, 2003; Gurung and Gurung, 2006; Kelkar, 2007). Gender and gendered power relations are thus critical variables shaping processes of ecological change (Elmhirst and Resurreccion, 2008), and ecological change, in turn, shapes gendered power relations (Agarwal, 1997; Gururani, 2002; Nightingale, 2011).

While researchers have tended to examine social inequities along only a single axis (e.g., gender, nationality, or marital status), feminist scholars have critiqued single-axis frameworks that consider gender in isolation from other social identities and have highlighted the value of intersectional approaches that account for the interdependent nature of identities (Crenshaw, 1989, 1991). Intersectionality is a framework that “promotes an understanding of human beings as shaped by the interaction of different identity markers (e.g., “race”/ethnicity, indigeneity, gender, class, sexuality, geography, age, disability/ability, migration status, religion) [which] occur within a context of connected systems and structures of power” (Hankivsky, 2014, p. 2). Intersectionality can deepen our understanding of fishers and fishing communities by revealing how different forms of social difference (e.g., gender and nationality, or gender; nationality; and marital status) interact to produce unique positions within power structures governing resource access and use, moving away from models that assume homogeneity among fishers, or among women fishers.

Researchers have increasingly applied intersectionality within the context of natural resources, highlighting the role of natural resource systems in producing and maintaining social differences and power hierarchies (Nightingale, 2006; Valentine, 2007). Recent studies have examined how gender interacts with ethnicity (Lau and Scales, 2016), class (Colwell et al., 2017), individual decision-making (Kusakabe and Sereyvath, 2014), religious denomination and place of birth (Rohe et al., 2018), and nationality (Yingst and Skaptadóttir, 2018) to shape fishers’ access to and control of marine resources. In this paper, I examine how the harms and benefits of the seafood trade are distributed among fishers, focusing on gender as it intersects with nationality and marital status, in the context of the sea cucumber trade in Palau.

Sea Cucumber Fishing in Palau

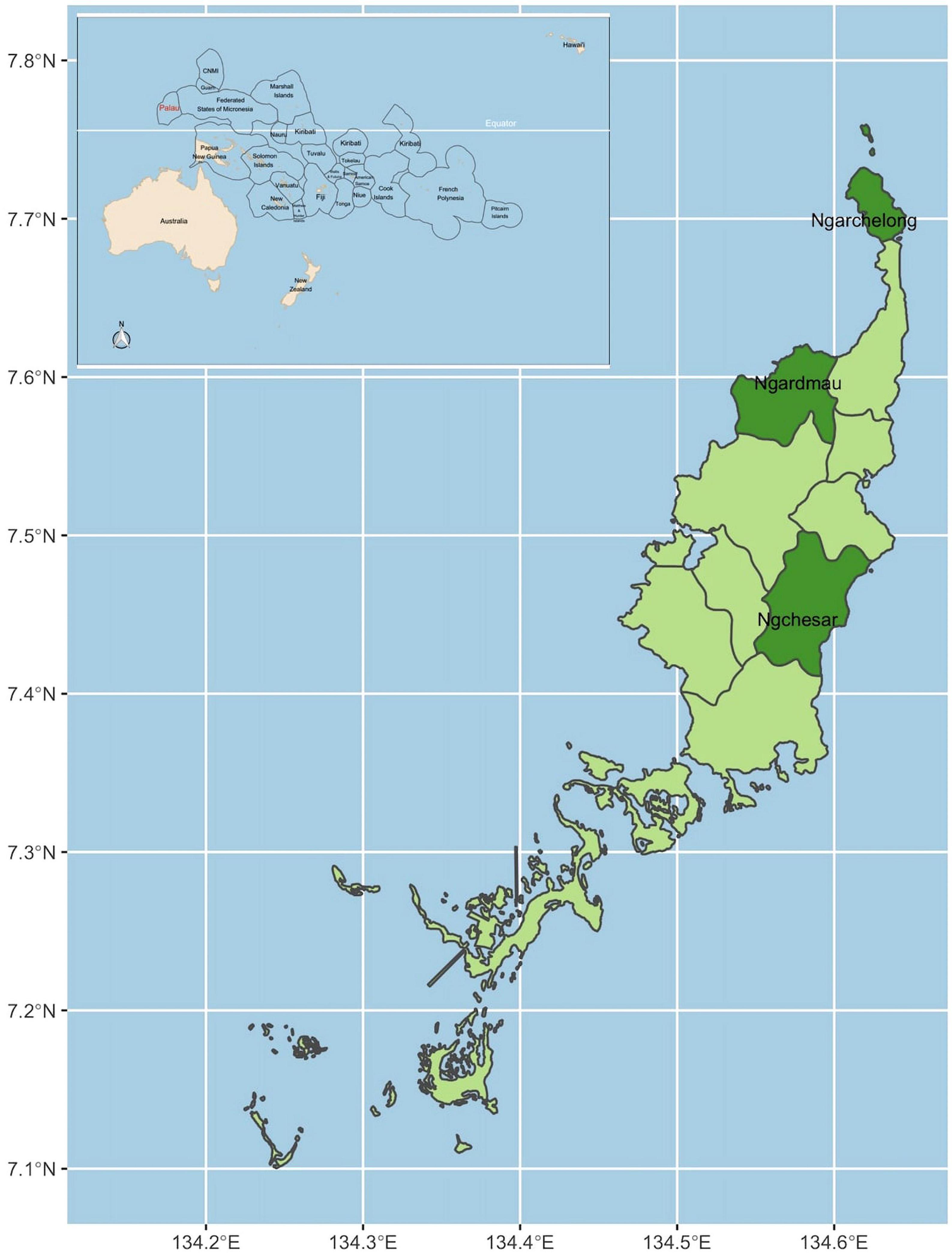

The Republic of Palau comprises more than 340 islands across over 475,000 km2, eight of which are inhabited (Figure 1). Palau is renowned for its high marine biodiversity, the health of its coral reef and seagrass systems (Golbuu et al., 2005), and its leadership in marine conservation (Gibbens, 2017). The town of Koror is the economic center of Palau, where two-thirds of the population resides and the majority of commercial activity is located.

Sixty-eight percent of Palau’s 17,661 residents are Palauan citizens; citizenship is only available to those who can trace their lineage to Indigenous Palauan ancestors, meaning that nationality, indigeneity, and power are closely linked (Palau Const. art. III, 1994). The remaining residents are immigrants: the majority of women immigrants (60%) are from the Philippines, and men immigrants originate from a diversity of countries including Bangladesh, the United States, China, Japan, and the Federated States of Micronesia (Palau Bureau of Planning and Statistics, 2015).

In 1994, Palau regained its sovereign status after enduring three centuries of colonial rule by Spain, Germany, Japan, and the United States. Today, Palau maintains a close relationship with the United States according to the Compact of Free Association, the treaty that established Palau as an independent nation “freely associated” with the United States. The Compact grants the United States military control of Palau in exchange for economic aid to Palau, freedom of Palauan residency in the United States, and the possibility for Palauans to serve in the U.S. military (Compact of Free Association, 1994).

Palauan culture has been fundamentally re-shaped by the values of colonizers and renegotiated to meet modern challenges, notably with respect to fisheries management and gender. Colonial policies created a centralized, democratic governance system that has undermined traditional leaders’ powers, challenging customary natural resource management practices that once relied on enforcement by local chiefs (Graham and Idechong, 1998). Meanwhile, the import of highly efficient fishing technologies and the marketization of the Palauan economy created the means and incentives to overfish (Graham and Idechong, 1998).

Colonization also shifted relations between men and women, both through the introduction of Christianity and through the privileging of Palauan men in positions of power within the patriarchal Japanese and American administrations of the islands (Wilson, 1995). Though Palauan women still enjoy a relatively high degree of authority within traditional governance systems, they are highly underrepresented in elected positions.

In Palau, the use of marine resources is customarily gendered, with men “fishing” finfish and women “gleaning” marine invertebrates, including sea cucumbers. These activities require different technologies and knowledges. Men typically use motorboats and gears such as spearguns and fishing poles to access their resources. Boys are taught to freedive, including long breath holds, from a young age. Men’s ecological knowledge is thus associated with reef habitats and deeper waters. Though sea cucumbers are found in these waters—in fact, the largest species are found there—men rarely collect them. Women, on the other hand, typically wade into shallow waters on foot or use man-powered boats (e.g., kayaks, bamboo rafts) to access nearshore invertebrates in waters typically less than 1 m deep. Girls typically do not learn to freedive. Women’s ecological knowledge is associated with seagrasses and shallow water habitats.

This traditional gender division of marine resources remains widespread but is evolving. The norm against women fishing is apparently stronger than the norm against men gleaning. In a 2020 nationwide survey, 86% of spearfishers in Palau were men and 57% of gleaners were women, with 72% of sea cucumber gleaners being women (Ferguson and Singeo, unpublished data). Ota (2006) explored the significance of spearfishing to Palauan masculine identity, arguing that fishermen prefer to use tools and techniques that create physical challenges because it allows them to express particular notions of masculinity. Ota also noted the common narrative provided by Palauan fishermen that spearfishing is too difficult for women to practice. The cultural construction of spearfishing as being highly masculine at least partially explains women’s lack of participation, while gleaning, which is physically less demanding, is feminized and done primarily by women. This gendered pattern of marine resource use is not uncommon in the Pacific or other geographies (Kleiber, 2014). Previous scholarship has found that women’s labor is spatially constrained by their responsibilities in the home (Gustavsson, 2020). Indeed, children in Palau often accompany women while they glean.

Palauans regularly consume twenty species of sea cucumbers, 12 of which are valuable for the bêche-de-mer trade (Pakoa et al., 2009; Purcell et al., 2018). Pacific nations including Palau have been producing beĉhe-de-mer for Chinese consumers for over a century (Conand and Sloan, 1989); however, mounting concerns about the social and environmental sustainability of the fishery eventually led to a moratorium on the export of sea cucumbers from Palau Marine Protection Act (1994).

In 2011, exporters and their Palauan partners circumvented this moratorium to export cherumrum (Latin: Actinopyga miliaris, A. mauitania, and A. lecanora; English: hairy blackfish, surf redfish, white-bottomed sea cucumber), as well as other species illegally (Pakoa et al., 2014). For six months, five foreign companies exported unprecedented volumes of sea cucumbers from Palau for the bêche-de-mer trade, before national legislation forced the companies to shutter operations in early 2012 (Pakoa et al., 2014). During those six months, fishers were allowed to harvest and sell an unlimited amount of sea cucumbers on Mondays and Thursdays, from 6 am to 6 pm (Pakoa et al., 2014). In just forty-eight total legal fishing days, approximately 1,160,392 kg (1,279 tons) of sea cucumbers were landed and sold at an estimated total value of US$1.3 million (Pakoa et al., 2014).

Once national action banned the export of all sea cucumbers, the exporters left Palau. Sea cucumber harvesting then returned to pre-export levels, with most of the collection being done by women for subsistence and small local markets. However, the environmental impacts of the export period were immediately felt and have proven to be long-lasting: a report produced by the Palau International Coral Reef Center in April 2012 demonstrated an 88% decline in the target species from pre-export levels (Golbuu et al., 2012), and recent monitoring indicates further decline in fished areas (Ferguson and Singeo, unpublished data). The ban on exporting sea cucumbers is still in place today. Thus, the special events of 2011 offer an opportunity to study how fishers quickly leverage their assets and social relations to access seafood trade benefits under new and short-term trade conditions.

Materials and Methods

I used a mixed methods single case study approach over multiple visits to the fifteen study communities between September 2019 and March 2020. In total, I spent 3 months in Palau during this period, based in Ollei village in Ngarchelong State. The research question, “How were the harms and benefits of the sea cucumber trade distributed among fishers in Palau?” was developed after a 1-year period of preliminary, unstructured interviews with Palauan fishers, marine scientists, fisheries management professionals, and conservationists from June 2018 to June 2019 based on frequently cited concerns and areas of research interest. Data were collected by me and five Palauan field assistants. Access theory (Ribot and Peluso, 2003) was chosen as an analytical frame to identify how individual fishers accessed the benefits of the sea cucumber trade. In the following sections, I justify site selection, provide a brief background on access theory, followed by a detailed description of each data collection method, and a summary of how data were analyzed. More detail is provided in Supplementary Material.

Site Selection

The fifteen rural villages included in this study represent every village in Ngardmau, Ngarchelong, and Ngchesar states (Figure 1). These small communities are all engaged in gleaning sea cucumbers for food security and income, particularly but not exclusively among women. Ngardmau was the most intensive site of harvest for the bêche-de-mer trade and is the site known throughout Palau for the quality and abundance of its sea cucumbers. Ngarchelong was intensely engaged in the harvest for the last month of the trade. Ngchesar, which is physically distant from the other states, was largely uninvolved in the trade, providing perspectives from fishers who rely heavily on the resource but who were impacted relatively little by the trade. At the 2015 census, the total population of these three states was 792, including 77 non-Palauan immigrants (Palau Bureau of Planning and Statistics, 2015).

Access Theory

Access theory is a political ecology approach to understanding how individual actors “derive benefits from things” (Ribot and Peluso, 2003), with a focus on natural resources as the “things”. Ribot and Peluso (2003) placed differential relations among actors and the “things” they want to benefit from at the center of their theory. They were informed by the popular critique that the common property literature is ahistorical and apolitical (Peters, 1993; Cleaver, 2002; Forsyth and Johnson, 2014). “A Theory of Access” took the notion of access as being associated chiefly with enforceable rights and expanded it to encompass a broader range of actors, structures, and social relations, including the illicit (Myers and Hansen, 2020). Ribot and Peluso (2003) focused on access as an ability, including but not limited to rights. They identified eight structural and relational “access mechanisms” (technology, capital, markets, labor, knowledge, authority, identities, and social relations) in addition to two rights-based mechanisms (legal and illegal access). Survey questions were structured by these mechanisms to understand individual fishers’ abilities to derive benefits from the sea cucumber trade.

Data Collection

Survey

To be able to make generalizable and quantifiable conclusions, I used a random sampling approach. I stratified the sample by gender to ensure near-equal representation of women and men. Survey data collection was done by four Palauan field assistants, in Palauan and English depending on the preference of the respondent. Survey respondents were randomly selected by knocking on every other door in each study community on weekends and evenings, when people were most likely to be home and available to respond. In order to capture the greatest possible diversity of respondents, enumerators surveyed as many people within the household as were willing and able. We continued to survey until we reached a sample achieving a 95% confidence interval with a 10% margin of error. In total, we surveyed 100 women and 105 men, including 11 non-Palauan immigrant women and 19 non-Palauan immigrant men.

Recognizing that gender and other identities are socially constructed, we asked respondents to self-identify their gender, nationality, marital status, age, level of education, employment status, and whether they held a customary title (a locally relevant measure of power and status). Although we offered multiple gender responses, including “transgender,” “non-binary,” and “other,” 100% of respondents self-identified as “woman” or “man.” Thus, results are reported in alignment with these categories. In addition to these identity questions, the survey included questions related to gleaning and local marketing of sea cucumbers, questions related to participation in the 2011 bêche-de-mer trade (e.g., “Did you participate?,” “Which species did you target?” with at least 1 question addressing each of the 10 access mechanisms identified by access theory), as well as observations of environmental changes. At the end of each survey, we asked respondents whether they would be interested in being contacted for a follow-up interview.

Interviews

To develop a more in-depth understanding of individual experiences and attitudes, I purposively sampled interview participants from the pool of survey respondents, as well as seven Palauan experts on women’s fisheries. Interviews were conducted by me, with the support of a Palauan field assistant and translator. Interviews ranged from ten to ninety min and were conducted in English or in Palauan, whichever was preferred by the respondent. Most Palauans today are fluent in English, and some younger Palauans are more comfortable speaking English than Palauan. A limitation of this study is that interviews with non-Palauans were all conducted in English due to a lack of appropriate translators of other languages, so some nuances may have been lost. I selected individuals to interview based on their level of experience gleaning, their participation in the bêche-de-mer harvest, their role in management and decision-making (i.e., state rangers and traditional leaders), and their intersecting identities, with the goal of hearing perspectives from people representing a diversity of social positions. In total, I interviewed 26 women and 23 men, including 4 non-Palauan immigrant women. Interviews were audio recorded and transcribed in English. In the case of interviews conducted in Palauan, I have not used direct quotes due to the imperfect nature of translations.

Semi-structured interviews focused in greater detail on fishers’ access mechanisms to sea cucumbers during the 2011 bêche-de-mer harvest, attitudes toward the bêche-de-mer trade, and ecological knowledge related to local sea cucumber populations. Questions related to the precise details of catch amounts and prices were generally avoided due to the eight year gap between the event and this investigation. Such details were thoroughly documented by managers and researchers during and shortly after the trade was closed, which were used to verify information recalled by fishers (Pakoa et al., 2014; Barr et al., 2016). Each interview included an opportunity for the participant to ask questions and provide informed consent, following ethical guidelines and approval from the Stanford University Institutional Review Board.

Data Analysis

Identifying Mechanisms of Access

To identify key mechanisms of access, I first coded interview data deductively in the Dovetail app1 using the access theory framework. After coding all interviews, “technology,” “knowledge,” and “authority” arose as the most common and explanatory access mechanisms. I then cross-referenced this finding with survey data, examining how fishers responded to questions on those access mechanisms.

Assessing the Distribution of Benefits and Harms

To assess the distribution of benefits and harms, I first coded interview data deductively in the Dovetail app (see text footnote 1) using the intersectionality framework. After coding all interviews, gender, marital status, and nationality arose as the most explanatory identities. I then used survey respondents’ self-identified identity markers (e.g., woman, Palauan, 40–45 years old, married, no title, etc.) to assess which actors had the ability to leverage key mechanisms of access during the trade, using Pearson chi-square tests for independence. Significance level was set at p < 0.05.

Finally, to understand the distribution of harms, I asked survey respondents about changes in local sea cucumber populations since the trade. I also coded interviews for any reference to “environmental harm.” This included references to resource degradation, difficulty finding sea cucumbers, and associated challenges obtaining food and income from gleaning.

Results

Distribution of Access to the Benefits of Trade

The sea cucumber fishery transformed swiftly during the export period from a low-tech, low volume gleaning activity done primarily by Palauan and immigrant women to a capital-intensive, high volume activity dominated by Palauan men. I use “gleaner” to describe the harvesters using traditional gleaning methods and “fisher” to describe the harvesters using these “new” methods normally reserved for harvesting finfish. I use “harvester” generically to refer to people harvesting sea cucumbers using any method.

Men largely displaced women in the trade. Under normal (i.e., non-trade) conditions, women in the study communities participate in sea cucumber gleaning at a significantly higher rate than men, representing 58% of gleaners, X2 (1, N = 206) = 6.0, p = 0.0140. However, during the export period in 2011, women represented only 38% of harvesters, participating significantly less than men X2 (1, N = 206) = 4.1, p = 0.0423.

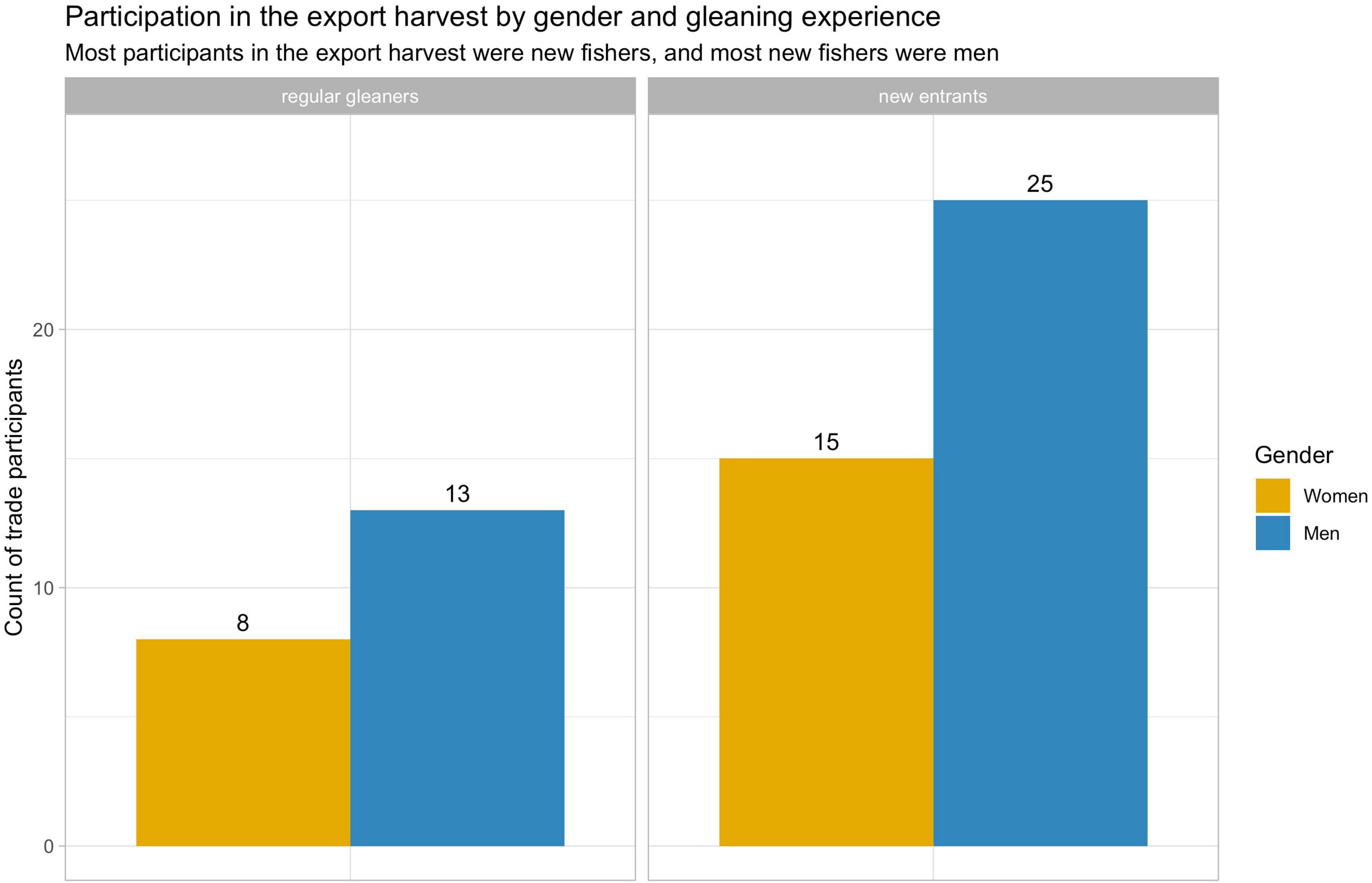

Most of the harvesters (66%) who participated in the trade (N = 61) were new entrants to the sea cucumber fishery, not gleaners who utilize sea cucumber resources under normal conditions (Figure 2). 63% of these new harvesters (N = 40) were men. Men gleaners were also significantly more likely (57%) to continue harvesting than women gleaners (25%) during the trade, X2 (1, N = 55) = 5.6, p = 0.0176.

Figure 2. Most fishers who participated in the trade were new entrants, and most new entrants were men. Whether or not a regular gleaner participated in the trade depended on their gender, with men gleaners more likely to participate.

The disproportionate and, according to some, culturally inappropriate role of men in the sea cucumber trade was noted by community members. One middle-aged Palauan woman gleaner in Ngarchelong remembered,

“It was the men, not the women. I remember sitting there, asking the men in our community, “Excuse me, it belongs to the women. Why are you encroaching?” It’s about money. It’s not about the people or the culture, it’s really just about money.”

Men justified their participation in the otherwise feminized, “easy” practice of sea cucumber harvesting by referencing the financial rewards. A middle-aged Palauan fisherman in Ngarchelong explained,

“It’s easy fishing, that’s why only women do it. But during that time, the buyer is here with a sack of money, then we ain’t waiting for our women, yeah? We got to go help them, get out the boat, you know? So, it was a different thing…. It was just money waiting.”

While gender was highly explanatory of which fishers participated in the trade, nationality was even more deterministic. 100% of people who reported participating in the trade (N = 61) were Palauan; none of the non-Palauans in the sample (N = 21), including the subset (N = 4) who glean under normal conditions, participated. Reasons for not participating varied among individuals in this group, and I was not able to interview all of them. Two Filipina women reported that they were working full-time in 2011 and unable to take time off to collect; it is likely that similar restrictions imposed by work visas applied to some other immigrants.

Mechanisms of Access

Access to Technology: Motorboats

Motorboats proved to be a critical technology for accessing and storing large volumes of sea cucumbers during the export period. Because gleaners do not typically collect in waters deeper than about a meter (3.28 feet), harvesters explained that deeper water populations of all species, further from shore, tended to be more abundant and home to larger individuals. Motorboats enabled access to these populations. Furthermore, harvesters without motorboats were more limited in how many sea cucumbers they could collect before returning to the port with full buckets. Only those harvesters with access to motorboats were able to store sea cucumbers in large volumes.

A middle-aged fisherman from Ngarchelong described the spectacle of fishing boats at Ngerkeklau, an island 2.7 km (1.7 miles) from the village, known for its abundance of sea cucumbers. He remembered with excitement, “The place looked like this new city, new village over there. Really! More than 40 lights every night,” referring to the lights of boats. The distance to Ngerkeklau and other unfished sites was too great to swim or paddle, meaning fishers without motorboats were harvesting in already exploited areas.

Among those who did not own boats, men reported significantly higher access to motorboats than women, with 81% of men and 69% of women in the sample reporting that they had access to a motorboat, X2 (1, N = 205) = 4.1, p = 0.0438. When asked whose motorboat a respondent had access to, 96% of gendered responses (N = 83) were male (e.g., brother, husband, male friend), indicating that the vast majority of those who control access to motorboats are men.

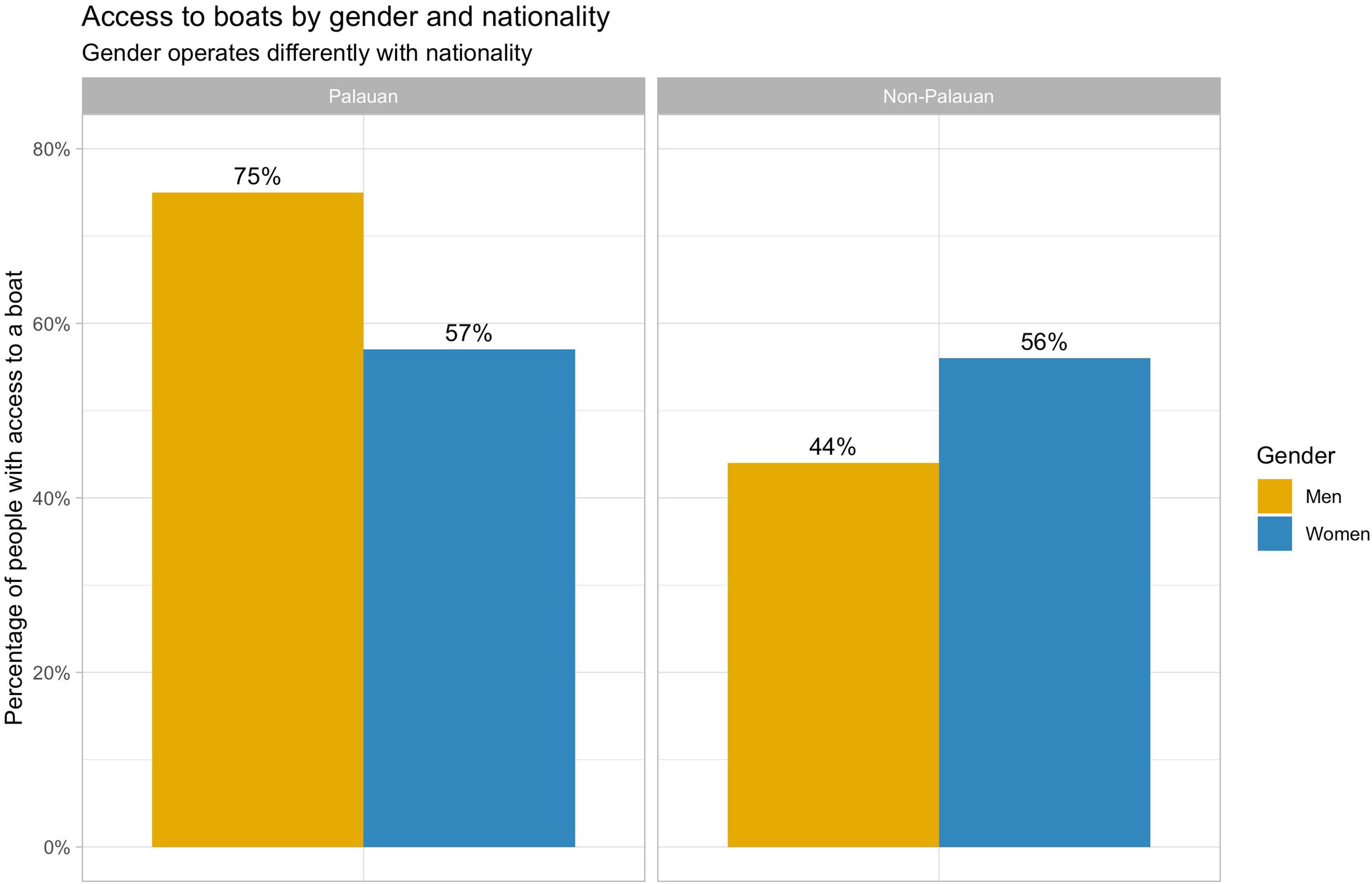

Both nationality and marital status profoundly shaped which women had close relations to Palauan men and thus had access to motorboats.

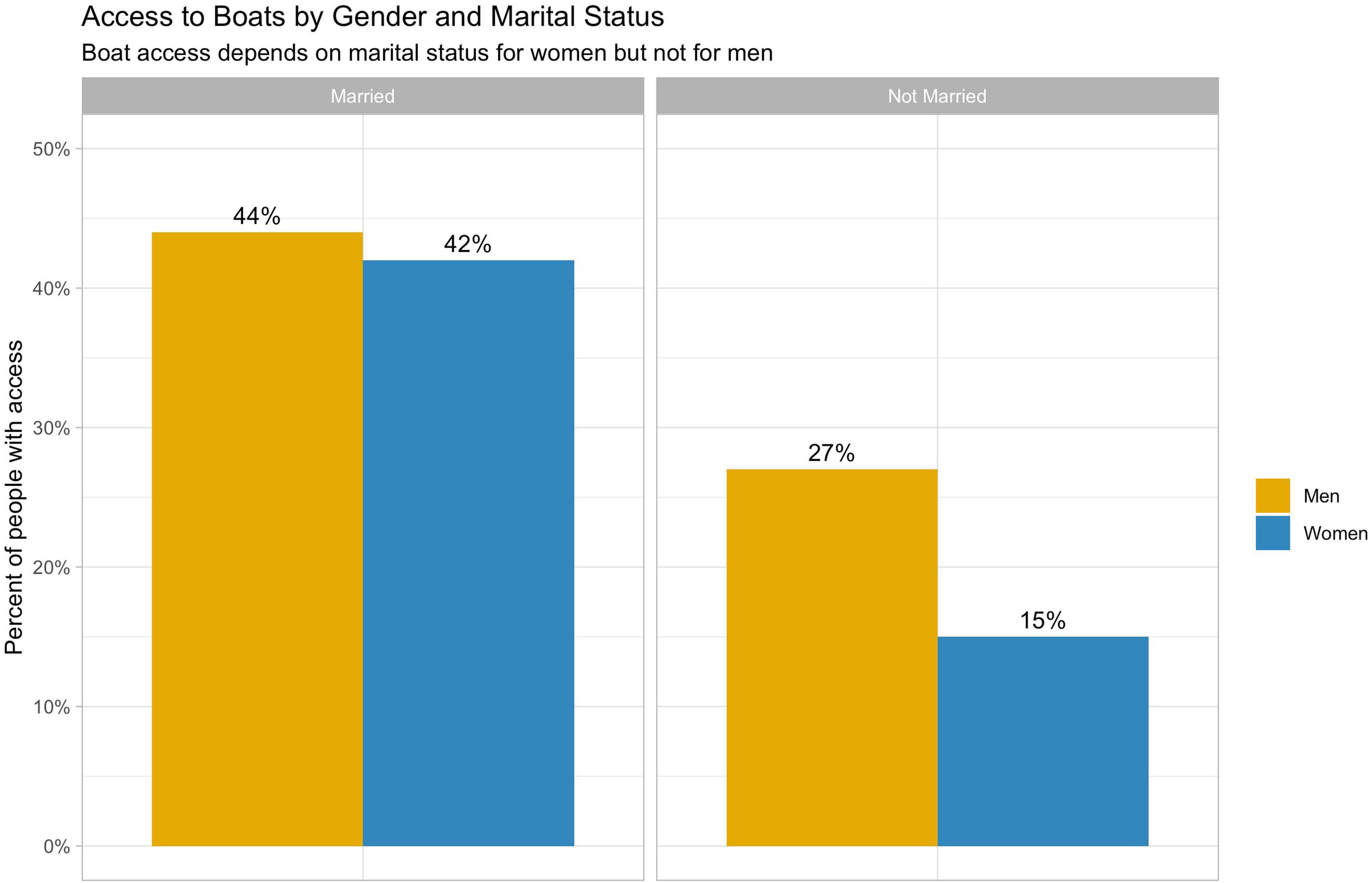

Among women in the sample who did not own boats, married women had significantly more access to motorboats than unmarried women, X2 (1, N = 63) = 7.3, p = 0.0071 (Figure 3). Meanwhile, among men in the sample, marital status had no significant effect on motorboat access, X2 (1, N = 69) = 1.9, p = 0.1632.

Among Palauans in the sample who did not own boats (N = 124), 66% reported having access to one; among immigrants (N = 20), fewer than half (45%) reported having access. Among non-Palauans, women actually had more access to motorboats than men, representing 56% of those with access (Figure 4). All of these women (N = 5) were married to Palauan men. However, the sample size of immigrants with access to motorboats was small, and the difference between immigrant men and immigrant women was not statistically significant.

Figure 4. Gender operates differently depending on a harvester’s nationality, with immigrant women having greater access to boats than immigrant men.

Access to Knowledge: Freediving, Gendered Ecological Knowledge, and Night Fishing

Knowledge of both freediving as a practice and of the deeper water habitats associated with this practice placed Palauan men in a better position to capitalize on the sea cucumber trade than other harvesters. A middle-aged Palauan fisherman from Ngarchelong explained,

“The guys that made the big bucks were the real fishermen. You know, they can stay down there ten minutes, they have like ten buckets. They’re faster and have more air to stay down and collect, collect.”

As a result of the gender division of marine resource use in Palau, marine ecological knowledge is gendered. Sea cucumber gleaners—primarily Palauan women—are the most knowledgeable about nearshore sea cucumber habitats and behaviors and thus might have been best positioned to capitalize on the sea cucumber trade. However, harvesting in these nearshore areas proved less efficient than harvesting in the deeper waters where spearfishers—primarily Palauan men—had more applicable ecological knowledge.

Though sea cucumbers are not their target species, fishermen’s extensive ecological knowledge of deeper water areas includes an awareness of sea cucumber habitats and behaviors that could be called upon when it became profitable. For example, bakelungal (Latin: Holothuria fuscogilva and H. whitmaei; English: white teatfish and black teatfish), the largest and highest-value species for bêche-de-mer in Palau, is found only in deeper waters, where typically only Palauan men fish. An elder Palauan fisherwoman and expert explained, “The men dive when they go fishing, so they know where to collect bakelungal. The women don’t collect those.” A middle-aged Palauan fisherman from Ngarchelong echoed this claim, “We [men] know where to find [bakelungal] from spearfishing and also net fishing.”

Ecological knowledge of Palauan marine environments is not only gendered but is also associated with being Palauan. A Yapese immigrant woman married to a Palauan man explained that sea cucumbers are not eaten in Yap and that she learned to glean them from her husband’s family when she moved to Palau. She said that, because she had not grown-up gleaning sea cucumbers, she had less knowledge of the animals and their habitats than Palauan women. To the extent that she does have ecological knowledge of sea cucumbers, she attributes it in large part to her marriage to a Palauan man.

Knowledge of nighttime fishing also proved advantageous and is also gendered in Palau. A middle-aged Palauan fisherman from Ngarchelong explained the advantage of night fishing thusly, “You know, at night [the sea cucumbers] come out. So it’s much easier. And once the tide gets lower, they’re just right there. You’re just walking, picking them up. Quick, quick money.” This nighttime behavior of sea cucumbers was noted by several participants in the study and is widely known by gleaners. However, nighttime fishing is not practiced by gleaners under normal conditions, who prefer to collect in the early morning, when “the sea cucumber hasn’t eaten yet so the intestines are clean,” according to an elder fisherwoman and expert. But because sea cucumbers are processed differently (i.e., smoked and dried) for bêche-de-mer, the cleanliness of the intestines was not a relevant quality criterion for the trade. An elder Palauan woman chief from Ngarchelong commented on the unusual and gendered nature of nighttime fishing for sea cucumbers, stating, “These people collected during nighttime. The [sea cucumber] comes out at night. And women don’t dive at night… it was a very different way of collecting.”

Access to Authority: State Rangers

State rangers are responsible for enforcing fisheries regulations within state waters in Palau. State rangers are overwhelmingly Palauan men. Eighty percentage of those in the study who had ever served as a state ranger (N = 20) were men and 100% were Palauan.

Palauan law required that exporting companies have a Palauan business partner to obtain a license, and all five exporting companies partnered with state rangers in this capacity. These partners were compensated with percentages of profits, with one ranger estimating he received over US$50,000 from the partnership (for comparison, the median annual income in rural areas in Palau is around US$12,870, Palau Office of Planning and Statistics, 2014). As business partners, these rangers gained early access to the market, weeks or even months before other fishers knew of the buyers’ presence. One ranger, a Palauan fisherman from Ngardmau who partnered with one of the companies, explained that, “Actually, the harvest was [going on for] more than a year,” with fishers who knew of the buyers’ presence collecting illegally for the first 6 months. Another Palauan fisherman, who was a state ranger in Ngarchelong at the time, reported that he kept the buyers’ presence a secret initially because, in his determination, prices were too low,

“I [was] the first one who went to collect. But I never told anybody because I wanted to see if they’re really buying at a good price… But they were buying really cheap. Ten cents per [sea] cucumber. So, I went one time, I deliver, and then I see it’s not worth it. I’m already killing my resources, my water, I’m killing it… So, I told them off. Okay, either you raise the price or I’m going to stop. So, I stopped and then they went to the other [state rangers].”

In their capacity as state rangers, a highly gendered position of authority restricted to Palauans, a small number of Palauan men benefited especially greatly from the trade.

Distribution of the Harms of Trade

After 6 months, legislation at the national level ended the legal harvest of sea cucumbers for export to the bêche-de-mer trade. Fishing quickly returned to normal conditions, with primarily women (58%) gleaning sea cucumbers using low-tech practices. An elder Palauan fisherman in Ngarchelong commented that he no longer collects since the exporters left because prices are too low and because he considers gleaning to be women’s work.

Predictably, severe decline in sea cucumber populations resulted from the trade. When asked how sea cucumber populations have changed in the past 10 years, 73% of survey respondents (N = 161) reported a decline since 2009. Fishers and gleaners connected this decline directly to the bêche-de-mer harvest. An elder fisherwoman from Ngardmau said the export harvest, “totally wiped them out, and fast.”

For gleaners, the decline in sea cucumbers is experienced as a decrease in their catch per unit effort. Nearly every active gleaner in the study commented on the decline in sea cucumbers, and a few former gleaners shared that they had stopped gleaning altogether because of the difficulty finding sea cucumbers. One elder Palauan woman and former gleaner from Ngardmau complained, “Nowadays, it’s too much walking around and looking.” As a result of resource degradation from the trade, gleaners—mostly Palauan and immigrant women—must work harder for longer to collect the same number of sea cucumbers as before the trade, resulting is less food and income for the same effort.

Discussion

This empirical case study demonstrates that the seafood trade does not impact all fishers equally and can serve to reinforce or exacerbate local power inequities. Fishers’ intersecting identities shaped how the benefits and harms of the sea cucumber trade were distributed among them in Palau. Palauan men benefited most while Palauan and immigrant women bear a disproportionate share of the short- and long-term harms. This result is surprising in light of the feminized nature of sea cucumber harvesting in Palau and represents a case of masculinization, in which women were largely displaced by men in the harvesting of their customary resources when those resources became more profitable. Masculinization has been documented under similar circumstances in the octopus trade in Tanzania (Porter et al., 2008) and invertebrate fisheries in the Pacific (Pinca et al., 2010; Williams, 2015). Today, the burden of resource degradation associated with the trade is borne primarily by women. It is thus critical that seafood trade policies consider local power dynamics, evaluate possible unintended consequences, and ensure that benefits are distributed equitably in fishing communities, while also managing environmental impacts that may affect less powerful fishers disproportionately.

While gender explains much of the difference in how harvesters interacted with the sea cucumber trade, results highlight the relevance of intersectionality as an analytical tool (Crenshaw, 1989, 1991). In particular, marital status and nationality both shaped which men and which women benefited. Married women benefited more than unmarried women, Palauan women benefited more than non-Palauan women, and non-Palauan men benefited least of everyone, undermining a simplistic interpretation of outcomes based on gender alone.

The literature on women in fisheries tends to conceptualize women as either being deprived of agency or having full agency (Gustavsson, 2020). However, this case demonstrates that women (and men) have limited agency within a given historical, spatial, and political context. In this case, less powerful actors leveraged their relationships with more powerful and resourced actors to access trade benefits; for example, married women gained access to motorboats through their husbands. Such nuances in the distribution of benefits would have been masked by an analysis that narrowly focused on gender and therefore highlights the importance of intersectional analysis in small-scale fisheries contexts (e.g., Kusakabe and Sereyvath, 2014; Lau and Scales, 2016; Colwell et al., 2017; Lokuge and Hilhorst, 2017; Rohe et al., 2018; Yingst and Skaptadóttir, 2018; Gustavsson, 2020). Furthermore, while many women in Palau may have accrued indirect financial benefits from their men family members’ earnings from the sea cucumber trade, such indirect benefits do not yield the same advancements in gender equality (U.N. Women., 2018), economic development and resilience (IMF., 2018), freedom from domestic violence (Conner, 2013), and political participation (Bari, 2005). In order to achieve global commitments to gender equality (UN General Assembly, 2015), it remains crucial that women enjoy individual economic empowerment within their households and in their communities. By definition, women’s economic empowerment “includes women’s ability to participate equally in existing markets; their access to and control over productive resources…” (U.N. Women., 2018). It is thus critical that trade policies account not only for benefits flowing to households but also to individuals, with consideration not only of their gender but also of their intersecting identities.

The harms of the trade were distributed in almost the opposite pattern of benefits. The majority of Palauan fishermen, who benefited most from the trade, only collected sea cucumbers in 2011, when exporters were paying very high prices, and do not collect anymore. They are therefore quite unimpacted by the decline in the fishery associated with overexploitation during the export period. Meanwhile, the women gleaners who benefited relatively little from the trade or—in the case of immigrant women—not at all must work harder and longer to collect even a fraction as many sea cucumbers as before the export period. This has direct impacts on their livelihoods, food security, cultural identity, and well-being (Grantham et al., 2020).

This case provides further support for the argument of feminist political ecologists that gendered power relations are constructed through relations with the environment (e.g., Agarwal, 1997; Gururani, 2002; Elmhirst and Resurreccion, 2008; Nightingale, 2011). In Palau, the preexisting gender division in access to and use of marine resources, with women primarily gleaning using minimal technologies and men primarily freediving for reef fish using motorboats, set the stage for the sudden masculinization of the sea cucumber fishery upon the arrival of exporters. Furthermore, the inequitable distribution of trade benefits and harms between women and men served to reinforce gendered power dynamics. Results also indicate that power hierarchies based not only on gender but also on intersecting identities are critical determinants of how actors interact with the environment and how resource degradation, in turn, shapes local power dynamics.

Nightingale (2011) argues that social inequalities are constantly shifting yet surprisingly resilient to major reconfigurations. In this case, the opening of the sea cucumber fishery to exporters was a monumental shift in how the fishery operated, presenting an opportunity for an unsettling and restructuring of local power hierarchies. Given the feminized nature of sea cucumber harvesting in Palau, one might have predicted that opening the trade would create an opportunity for women’s economic empowerment and the advancement of gender equality. Yet preexisting power hierarchies appear to have been further entrenched, rather than challenged, by the sea cucumber trade. This resilience of social inequalities in fishing communities and the configurations of fisheries management and practices that disrupt or entrench them warrants further study.

Conclusion

Fishing communities are not homogeneous, and fisheries policies do not impact all fishing community members equally. Fisheries policies and development strategy should carefully account for and include in decision-making a diversity of actors across intersecting lines of identity to assess and anticipate possible unintended consequences. This case study demonstrates that a failure to account for these intersections can lead to the unintended exclusion of the most vulnerable groups and risks entrenching inequities in fishing communities.

Small-scale fisheries around the globe are increasingly subject to global market forces that can have severe short- and long-term impacts on fishing communities and their resources. While increased connectivity through trade has the potential to deliver economic development, it also poses sustainability and equity challenges. This case provides one of many examples of resource degradation resulting from the seafood trade (Crona et al., 2015)—an issue that is particularly common in sea cucumber fisheries (Anderson et al., 2011; Purcell et al., 2013)—and expands our understanding of the longer-term impacts of resource degradation on the (re)production of social inequities. Policymakers and community-level decision-makers should therefore adopt a precautionary and inclusive approach when addressing new market opportunities for locally utilized marine resources.

It is critically important to increase understanding and consideration of how the intersecting identities of actors in fisheries, aquaculture, and other socio-ecological systems shape their access to and use of resources, and how resource degradation in turn may serve to entrench inequities. Paying attention to resource users’ intersecting identities has profound implications for designing processes and policies that promote equity in socio-ecological systems across the globe.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Stanford University Institutional Review Board. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

CF was the sole author of this manuscript. CF developed the research question and protocol, conducted data collection and analysis, and wrote the manuscript.

Funding

This research was generously funded by the Stanford VPGE Diversity Dissertation Research Opportunity, E-IPER Summer Research Grant, and McGee-Levorsen Grant from the Stanford School of Earth, Energy & Environmental Sciences.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This study would not have been possible without the support and hard work of Ann Singeo, Surech Bells, John Chilton, Ladrick Ngedebuu, Amber Sky Skiwo, and Raegeen Tadao. Thank you also to Fiorenza Micheli, William Durham, Bob Richmond, and Kevin Arrigo, who advised on this project from its earliest stages. I am indebted to Autumn Bordner for her assistance with the figures and to Josheena Naggea for early and insightful reviews of this article. Thank you also to the reviewers, whose comments greatly improved the article. This study was done under the advisement of the Palauan NGO, Ebiil Society, and in conjunction with our ongoing collaborative research efforts. Leaders and members of Ebiil Society advised on the cultural appropriateness of survey and interview questions, provided translations, acted as field assistants, and facilitated the relationship building in communities that enabled these data to be collected. Finally, my gratitude to the fishers and gleaners who participated in this study, welcomed me into their communities, and shared their knowledge.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmars.2021.625389/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

References

Agarwal, B. (1997). “Bargaining” and gender relations: within and beyond the household. Feminist Eco. 3, 1–51. doi: 10.1080/135457097338799

Agrawal, A., and Gibson, C. C. (2001). Communities and the environment: ethnicity, gender, and the state in community-based conservation. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Agrawal, A., and Gibson, C. C. (1999). Enchantment and disenchantment: the role of community in natural resource conservation. World Dev. 27, 629–649. doi: 10.1016/s0305-750x(98)00161-2

Agrawal, A., Smith, R. C., and Li, T. (1997). Community in conservation: beyond enchantment and disenchantment. Gainesville, FL: Conservation & Development Forum.

Allison, E. H., and Ellis, F. (2001). The livelihoods approach and management of small-scale fisheries. Marine policy 25, 377–388. doi: 10.1016/s0308-597x(01)00023-9

Anderson, S. C., Flemming, J. M., Watson, R., and Lotze, H. K. (2011). Serial exploitation of global sea cucumber fisheries. Fish Fisheries 12, 317–339. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-2979.2010.00397.x

Barclay, K., Fabinyi, M., Kinch, J., and Foale, S. (2019). Governability of high-value fisheries in low-income contexts: a case study of the sea cucumber fishery in papua new guinea. Hum. Ecol. 47, 381–396. doi: 10.1007/s10745-019-00078-8

Bari, F. (2005). Women’s political participation: Issues and Challenges. In United Nations Division for the Advancement of Women Expert Group Meeting: Enhancing Participation of Women in Development through an Enabling Environment for Achieving Gender Equality and the Advancement of Women. Bangkok: Division for the Advancement of Women.

Barr, R., Ullery, N., Dwight, I., and Bruner, A. (2016). Palau’s sea cucumber fisheries: the economic rationale for sustainable management. Washington DC: Conservation Strategy Fund.

Béné, C., Lawton, R., and Allison, E. H. (2010). “Trade matters in the fight against poverty”: narratives, perceptions, and (lack of) evidence in the case of fish trade in africa. World Dev. 38, 933–954. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2009.12.010

Campling, L. (2012). The tuna ‘commodity frontier’: business strategies and environment in the industrial tuna fisheries of the western indian ocean. J. Agrarian Change 12, 252–278. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0366.2011.00354.x

Christensen, A. E. (2011). Marine gold and atoll livelihoods: the rise and fall of the bêche-de-mer trade on ontong java, solomon islands. Nat. Res. Forum 35, 9–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-8947.2011.01343.x

Cleaver, F. (2002). Reinventing institutions: Bricolage and the social embeddedness of natural resource management. Eur. J. Dev. Res. 14, 11–30. doi: 10.1080/714000425

Collins, P. H. (1986). Learning from the outsider within: the sociological significance of black feminist thought. Soc. Prob. 33, s14–s32.

Compact of Free Association (1994). Republic of Palau. Available online at: https://pw.usembassy.gov/wp-content/uploads/sites/282/2017/05/rop_cofa.pdf

Colwell, J. M. N., Axelrod, M., Salim, S. S., and Velvizhi, S. (2017). A gendered analysis of fisherfolk’s livelihood adaptation and coping responses in the face of a seasonal fishing ban in Tamil Nadu & Puducherry, India. World Dev. 98, 325–337. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2017.04.033

Conand, C. (2017). Expansion of global sea cucumber fisheries buoys exports. Revista de Biología Tropical 65, S1–S10.

Conand, C., and Sloan, N. A. (1989). “World fisheries for echinoderms,” in Marine invertebrate fisheries: their assessment and management, ed. J. F. Caddy, (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley).

Conner, D. H. (2013). Financial freedom: women, money, and domestic abuse. Wm. Mary J. Women L. 20:339.

Crenshaw, K. (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: a black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. U. Chi. Legal F. 1, 139–167.

Crenshaw, K. (1991). Mapping the margins: Identity politics, intersectionality, and violence against women. Stanford Law Rev. 43, 1241–1299. doi: 10.2307/1229039

Crona, B. I., Basurto, X., Squires, D., Gelcich, S., Daw, T. M., Khan, A., et al. (2016). Towards a typology of interactions between small-scale fisheries and global seafood trade. Marine Policy 65, 1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2015.11.016

Crona, B. I., Van Holt, T., Petersson, M., Daw, T. M., and Buchary, E. (2015). Using social–ecological syndromes to understand impacts of international seafood trade on small-scale fisheries. Global Environ. Change 35, 162–175. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2015.07.006

De Guzman, A. B. (2019). Women in subsistence fisheries in the philippines: the undervalued contribution of reef gleaning to food and nutrition security of coastal households. SPC Women Fisheries Bull. 29, 34–40.

Elmhirst, R., and Resurreccion, B. P. (2008). Gender, Environment and Natural Resource Management: New Dimensions, New Debates. Gender and Natural Resource Management: Livelihoods, Mobility and Interventions, 3–22. doi: 10.4324/9781849771436

Eriksson, H., Österblom, H., Crona, B., Troell, M., Andrew, N., Wilen, J., et al. (2015). Contagious exploitation of marine resources. Front. Ecol. Environ. 13:435–440. doi: 10.1890/140312

Fabinyi, M. (2012). Historical, cultural and social perspectives on luxury seafood consumption in china. Environ. Conserv. 39, 83–92. doi: 10.1017/s0376892911000609

Fabinyi, M., Dressler, W. H., and Pido, M. D. (2018). Moving beyond financial value in seafood commodity chains. Marine Policy 94, 89–92. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2018.04.033

Ferrol-Schulte, D., Ferse, S. C., and Glaser, M. (2014). Patron–client relationships, livelihoods and natural resource management in tropical coastal communities. Ocean Coastal Manag. 100, 63–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2014.07.016

Forsyth, T., and Johnson, C. (2014). Elinor Ostrom’s legacy: Governing the commons and the rational choice controversy. Dev. Chan. 45, 1093–1110. doi: 10.1111/dech.12110

Gephart, J. A., and Pace, M. L. (2015). Structure and evolution of the global seafood trade network. Environ. Res. Lett. 10:125014. doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/10/12/125014

Gibbens, S. (2017). This Small Island Nation Makes a Big Case For Protecting Our Oceans. Washington, DC: National Geographic.

Golbuu, Y., Andrew, J., Koshiba, S., Mereb, G., Merep, A., Olsudong, D., et al. (2012). Status of sea cucumber population at Ngardmau State, Republic of Palau. Koror: Palau International Coral Reef Center, 11–12.

Golbuu, Y., Bauman, A., Kuartei, J., and Victor, S. (2005). The state of coral reef ecosystems of palau. State Coral Reef Ecosyst. U S Pacific Freely Assoc. States 2005, 488–507.

Graham, T., and Idechong, N. (1998). Reconciling customary and constitutional law: managing marine resources in palau, micronesia. Ocean Coastal Manag. 40, 143–164. doi: 10.1016/s0964-5691(98)00045-3

Grantham, R., Lau, J., and Kleiber, D. (2020). Gleaning: beyond the subsistence narrative. Maritime Stud. 19, 509–524. doi: 10.1007/s40152-020-00200-3

Gurung, C., and Gurung, N. (2006). The social and gendered nature of ginger production and commercialization: a case study of the Rai, Lepcha and Brahmin-Chhetri in Sikkim and Kalimpong, West Bengal, India. Ottawa, CA: International Development Research Centre.

Gururani, S. (2002). Forests of pleasure and pain: Gendered practices of labor and livelihood in the forests of the Kumaon Himalayas, India. Gender Place Cult. J. Femin. Geogr. 9, 229–243. doi: 10.1080/0966369022000003842

Gustavsson, M. (2020). Women’s changing productive practices, gender relations and identities in fishing through a critical feminisation perspective. J. Rural Stud. 78, 36–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2020.06.006

Hankivsky, O. (2014). Intersectionality 101. Vancouver, CA: Institute for Intersectionality Research & Policy, SFU, 1–34.

Harper, S., Adshade, M., Lam, V. W., Pauly, D., and Sumaila, U. R. (2020). Valuing invisible catches: estimating the global contribution by women to small-scale marine capture fisheries production. PloS One 15:e0228912. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0228912

Harper, S., Zeller, D., Hauzer, M., Pauly, D., and Sumaila, U. R. (2013). Women and fisheries: contribution to food security and local economies. Marine Policy 39, 56–63. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2012.10.018

Harris, L. M. (2006). Irrigation, gender, and social geographies of the changing waterscapes of southeastern anatolia. Environ.Plan. D Soc. Space 24, 187–213. doi: 10.1068/d03k

Kelkar, M. (2007). Local knowledge and natural resource management: a gender perspective. Ind. J. Gender Stud. 14, 295–306. doi: 10.1177/097152150701400205

Kleiber, D. (2014). Gender and small-scale fisheries in the Central Philippines. Doctoral dissertation. Columbia: University of British Columbia.

Kleiber, D., Harris, L. M., and Vincent, A. C. (2015). Gender and small-scale fisheries: a case for counting women and beyond. Fish Fisheries 16, 547–562. doi: 10.1111/faf.12075

Krishna, S. (1998). Gender Dimensions in Biodiversity Management. Arunachal Pradesh, IND: Sage Publication, 148–181.

Kusakabe, K. Y. O. K. O., and Sereyvath, P. R. A. K. (2014). Women fish border traders in cambodia: what shapes women’s business trajectories. Asian Fisheries Sci. 27, 43–57.

Lau, J. D., and Scales, I. R. (2016). Identity, subjectivity and natural resource use: How ethnicity, gender and class intersect to influence mangrove oyster harvesting in the gambia. Geoforum 69, 136–146. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2016.01.002

Lokuge, G., and Hilhorst, D. (2017). Outside the net: Intersectionality and inequality in the fisheries of trincomalee, Sri Lanka. Asian J. Women Stud. 23, 473–497. doi: 10.1080/12259276.2017.1386839

Matthews, E. (1991). The role of women in the fisheries of Palau. Corvallis, USA: Oregon State University.

Nightingale, A. (2006). The nature of gender: work, gender, and environment. Environ. Plan. D Soc. space 24, 165–185. doi: 10.1068/d01k

Nightingale, A. J. (2011). Bounding difference: Intersectionality and the material production of gender, caste, class and environment in Nepal. Geoforum 42, 153–162. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2010.03.004

Nolan, C. (2019). Power and access issues in Ghana’s coastal fisheries: A political ecology of a closing commodity frontier. Marine Policy 108:103621. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2019.103621

Myers, R. and Hansen, C. P. (2020). Revisiting a theory of access: a review. Soc. Nat. Resour. 33, 146–166. doi: 10.1080/08941920.2018.1560522

O’Neill, E. D., Crona, B., Ferrer, A. J. G., Pomeroy, R., and Jiddawi, N. S. (2018). Who benefits from seafood trade? a comparison of social and market structures in small-scale fisheries. Ecol. Soc. 23:26799136.

Ota, Y. (2006). Fluid bodies in the sea: an ethnography of underwater spear gun fishing in palau, micronesia. Worldviews Global Rel. Cul. Ecol. 10, 205–219. doi: 10.1163/156853506777965811

Pakoa, K., Friedman, K., Moore, B., Tardy, E., and Bertram, I. (2014). Assessing tropical marine invertebrates: A manual for Pacific Island resource managers. Noumea, NC: Secretariat of the Pacific Community, 118.

Pakoa, K., Lasi, F., Tardy, E., and Friedman, K. (2009). The status of sea cucumbers exploited by Palau’s subsistence fishery. Noumea, NC: Secretariat of the Pacific Community.

Palau Bureau of Planning and Statistics. (2015). 2015 Census of Population and Housing. Palau: Office of Planning & Statistics.

Palau Const. art. III (1994). Palau’s Constitution of 1981 with Amendments through 1992. Available online at: https://www.constituteproject.org/constitution/Palau_1992.pdf?lang=en

Palau Office of Planning and Statistics. (2014). 2014 Household Income and Expenditure Survey. Koror, Palau: Economics Departments, Institutes and Research Centers in the World.

Palau Marine Protection Act (1994). RPPL No. 4-18. Available online at: http://extwprlegs1.fao.org/docs/pdf/pau38135.pdf

Peters, P. E. (1993). Is “rational choice” the best choice for Robert Bates? An anthropologist’s reading of Bates’s work. World Dev. 21, 1063–1076. doi: 10.1016/0305-750X(93)90062-E

Pinca, S., Kronen, M., Friedman, K., Magron, F., Chapman, L., Tardy, E., et al. (2010). Regional assessment report: Profiles and results from survey work at 63 sites across 17 Pacific Island Countries and Territories. Pacific Regional Oceanic and Coastal Fisheries Development Programme (PROCFish/C/CoFish). Noumea, New Caledonia: Secretariat of the Pacific Community, 512.

Porter, M., Mwaipopo, R., Faustine, R., and Mzuma, M. (2008). Globalization and women in coastal communities in tanzania. Development 51, 193–198. doi: 10.1057/dev.2008.4

Presterudstuen, G. H. (2019). “Understanding sexual and gender diversity in the Pacific Islands,” in Pacific Social Work: Navigating Practice, Policy and Research, eds J. Ravulo, T. Mafile’o, and D. B. Yeates, (Abingdon, VA: Routledge), 161–171. doi: 10.4324/9781315144252-15

Purcell, S. W., Crona, B. I., Lalavanua, W., and Eriksson, H. (2017). Distribution of economic returns in small-scale fisheries for international markets: a value-chain analysis. Marine Policy 86, 9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2017.09.001

Purcell, S. W., Mercier, A., Conand, C., Hamel, J. F., Toral-Granda, M. V., Lovatelli, A., et al. (2013). Sea cucumber fisheries: global analysis of stocks, management measures and drivers of overfishing. Fish Fisheries 14, 34–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-2979.2011.00443.x

Purcell, S. W., Polidoro, B. A., Hamel, J. F., Gamboa, R. U., and Mercier, A. (2014). The cost of being valuable: predictors of extinction risk in marine invertebrates exploited as luxury seafood. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 281:20133296. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2013.3296

Purcell, S. W., Williamson, D. H., and Ngaluafe, P. (2018). Chinese market prices of beche-de-mer: implications for fisheries and aquaculture. Marine Policy 91, 58–65. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2018.02.005

Rohe, J., Schlüter, A., and Ferse, S. C. (2018). A gender lens on women’s harvesting activities and interactions with local marine governance in a south pacific fishing community. Maritime Stud. 17, 155–162. doi: 10.1007/s40152-018-0106-8

Sillitoe, P. (2003). The gender of crops in the papua new guinea highlands. Women and plants. Gender Relat. Biodivers. Manag. Conserv. 2003, 165–180.

Singh, A. M., and Burra, N. (1993). Women and wasteland development in India. New Delhi: Sage Publications.

U. N. Women. (2018). Facts and Figures: Economic Empowerment Benefits of Economic Empowerment. New York, NY: UN Women.

UN General Assembly (2015). Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. New York, NY: UN General Assembly.

Uthicke, S., Welch, D., and Benzie, J. A. H. (2004). Slow growth and lack of recovery in overfished holothurians on the great barrier reef: evidence from DNA fingerprints and repeated large-scale surveys. Conserv. Biol. 18, 1395–1404. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2004.00309.x

Valentine, G. (2007). Theorizing and researching intersectionality: a challenge for feminist geography. Prof. Geogr. 59, 10–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9272.2007.00587.x

Vedavalli, L., and Anil Kumar, N. (1998). “Wayanad, Kerala,” in Gender dimensions in biodiversity management, ed. M. Swaminathan (Delhi: Konark Publishers Pvt. Ltd.), 96–106.

Weeratunge, N., Snyder, K. A., and Choo, P. S. (2010). Gleaner, fisher, trader, processor: understanding gendered employment in fisheries and aquaculture. Fish Isheries 11, 405–420. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-2979.2010.00368.x

Williams, M. J. (2008). Why look at fisheries through a gender lens? Development 51, 180–185. doi: 10.1057/dev.2008.2

Williams, M. J. (2015). Pacific invertebrate fisheries and gender–Key results from PROCFish. SPC Women Fisheries Inf. Bull. 26, 12–16.

Wilson, L. B. (1995). Speaking to power: Gender and politics in the Western Pacific. East Sussex, UK: Psychology Press.

Keywords: seafood trade, gender, small-scale fisheries, equity, intersectionality

Citation: Ferguson CE (2021) A Rising Tide Does Not Lift All Boats: Intersectional Analysis Reveals Inequitable Impacts of the Seafood Trade in Fishing Communities. Front. Mar. Sci. 8:625389. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2021.625389

Received: 02 November 2020; Accepted: 25 February 2021;

Published: 12 April 2021.

Edited by:

Holly J. Niner, University of Plymouth, United KingdomReviewed by:

Madeleine Gustavsson, Institute for Rural and Regional Research (RURALIS), NorwaySarah Lawless, ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies, Australia

Copyright © 2021 Ferguson. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Caroline E. Ferguson, Y2VmZXJndXNAc3RhbmZvcmQuZWR1

Caroline E. Ferguson

Caroline E. Ferguson