- 1Imperiled Species Management, Division of Habitat and Species Conservation, Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, Tallahassee, FL, United States

- 2Wildlife Research Section, Fish and Wildlife Research Institute, Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, New Smyrna Beach, FL, United States

- 3Wildlife Research Section, Fish and Wildlife Research Institute, Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, Tequesta, FL, United States

- 4Imperiled Species Management, Division of Habitat and Species Conservation, Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, Tequesta, FL, United States

- 5Information Science & Management Section, Fish and Wildlife Research Institute, Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, St. Petersburg, FL, United States

- 6Wildlife Research Section, Fish and Wildlife Research Institute, Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, Jacksonville, FL, United States

Incidental captures of sea turtles during fishing activities affect their populations worldwide. Previous research has documented the impacts of commercial fisheries in nearshore and offshore waters, and research-based minimization measures are now required to reduce sea turtle take. However, incidental captures of juvenile-to-adult sea turtles also occur in recreational fisheries in nearshore and inshore waters, although the magnitude and distribution of these events are poorly understood. We analyzed Florida Sea Turtle Stranding and Salvage Network (STSSN) reports between 2000 and 2022 to identify sea turtles incidentally captured by recreational anglers from fishing piers along Florida’s Gulf coastline. We used a negative binomial regression model to quantify temporal and spatial changes in the mean number of pier-captured sea turtles reported at Gulf piers over the 23-year study period. There were 452 documented incidents of loggerheads (Caretta caretta), green turtles (Chelonia mydas), and Kemp’s ridleys (Lepidochelys kempii) hooked at 33 different piers. Juvenile and subadult turtles of all three species were pier-captured as well as adult loggerhead and Kemp’s ridley turtles. The number of turtles for each of the three species captured varied over time, but overall the number of reported captures increased regionally over the 23-year study. Most turtles captured and recovered at recreational fishing piers were successfully rehabilitated and released back to the wild (84.7.%). The observed increases in sea turtle pier capture reports likely reflect some combination of increased turtle numbers in the nearshore environment, increased use of piers as foraging habitat, and increased reporting requirements and effort. This analysis offers insights into the complex interactions between sea turtles and pier-based recreational fishing in the Gulf and could help inform conservation efforts while supporting responsible recreational fishing practices.

1 Introduction

The state of Florida hosts globally significant populations of all size classes of five threatened and endangered sea turtle species while also supporting economically important recreational fishing opportunities. Though efforts have been made to mitigate and minimize the impacts of fisheries on sea turtle populations, the role of recreational fisheries in sea turtle interactions remains an area that warrants further study. Previous research throughout the past few decades has documented population-level negative impacts on sea turtles resulting from lethal and sublethal interactions with large-scale industrial fisheries across the world (Aguilar et al., 1995, National Marine Fisheries Service Southeast Fisheries Science Center, 2001, Lewison et al., 2004; Finkbeiner et al., 2011; Wallace et al., 2013). Recent studies have assessed interactions between smaller-scale fisheries and sea turtles (Alfaro-Shigueto et al., 2011; López-Barrera et al., 2012; Lloret et al., 2020), but very few studies have sought to quantify the impacts of recreational fishing on sea turtle populations (but see Putman et al., 2023). Monitoring bycatch in recreational fisheries is difficult due to the lack of substantive reporting requirements for recreational anglers and limited feasibility of implementing large-scale monitoring programs across such diverse and diffuse fisheries (Keithly and Roberts, 2017; Hyder et al., 2020; Putman et al., 2023; Grimm et al., 2025). Despite these challenges, a recent study has indicated that bycatch rates in recreational fisheries have surpassed sea turtle bycatch across several major commercial fisheries (Putman et al., 2023). Most studies on recreational fishing impacts on sea turtles rely on assessments of strandings (Chaloupka et al., 2008; Foley et al., 2014, Tagliolatto et al., 2020), which allow researchers to identify significant hotspots of turtle-fisheries interactions (Cannon et al., 1994; Coleman et al., 2016; Siegfried et al., 2021; Lawani et al., 2022; Rose et al., 2022; Reimer et al., 2023). Because of the dearth of information on the impacts of recreational fishing on sea turtle populations, recovery plans for all five Gulf sea turtle species (loggerhead – Caretta caretta, green turtle – Chelonia mydas, Kemp’s ridley – Lepidochelys kempii, hawksbill - Eretmochelys imbricata, leatherback - Dermochelys coriacea) emphasize the need to quantify these interactions and identify mitigation and minimization strategies to support population recovery (NMFS and USFWS, 1991, 1992, 1993, 2008, Seminoff et al., 2015; National Marine Fisheries Service, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and SEMARNAT et al., 2011).

Interactions with hook-and-line fishing gear can cause multiple lethal and sublethal effects on sea turtles. Turtles can suffer fatal consequences from hook ingestions due to tearing of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract or vasculature (Casale et al., 2008) and the introduction of toxins or bacteria into internal wounds and tissues (Oros et al., 2004). Other studies have noted that turtles in rehabilitation from commercial fisheries interactions can expel hooks within the upper GI tract that are not embedded with little medical assistance (Aguilar et al., 1995; Werneck et al., 2008; Heaton et al., 2016). Embedded hooks within the esophagus may break down or pass through the digestive tract over time (Alegre et al., 2006; Parga, 2012; Heaton et al., 2016). However, hook decomposition likely depends on the size and material of the hook (Mcgrath et al., 2011). Monofilament, braid, wire, and other forms of line attached to hooks can obstruct, sever, plicate (fold) the intestines, or cause intestinal inversion (intussusception), likely resulting in the mortality of the animal well after release (Bjorndal et al., 1994; Oros et al., 2004; Valente et al., 2007; Casale et al., 2008; Parga, 2012). Lifting a hooked turtle out of the water by pulling on the line or retrieving with a fishing rod creates the risk of hooks embedding deeper into tissues, leading to larger wounds or tears in the GI tract and oral cavity (Oros et al., 2004; Casale et al., 2008; Parga, 2012). Line trailing from the mouth or cloaca can become entangled around the flippers, submerged structures, or marine debris, potentially resulting in tissue necrosis, loss of flippers, and/or drowning (Watson et al., 2005). Turtles can also experience multiple sublethal effects from incidental capture if they are released without rehabilitation (Wilson et al., 2014). Williard et al. (2015) documented increased physiological stress in commercial long-line hooked turtles when compared to hand-caught turtles, including lower Packed Cell Volume (PCV) and higher levels of corticosterone, an indicator of stress, in circulating plasma.

Recreational fisheries provide significant economic and social benefits, offering diverse fishing opportunities across Florida’s coastal waters, including areas inhabited by sea turtles (Font et al., 2012; Keithly and Roberts, 2017; Hyder et al., 2020). The extent of potential recreational angler interactions with sea turtles is understudied, requiring more research to understand this industry’s effects on sea turtle populations worldwide (Oravetz, 1999; Hyder et al., 2020). Reporting procedures for incidental captures are further complicated by diverse regulations across different geographic regions. In the United States, the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) sets regulations for federal waters while state fishery agencies set regulations and are responsible for enforcement within state waters extending up to ~15 kilometers offshore (Hughes, 2015). Documentation of incidental sea turtle captures often relies on anglers to report the incidents to the local Sea Turtle Stranding and Salvage Network (STSSN). Whether these incidents are reported depends on an angler’s knowledge of when and how to report sea turtle incidental captures as well as their willingness to disclose the capture of an endangered species (Cook et al., 2020; Rose et al., 2022). As fishing participation and sea turtle populations both increase along coastal communities, interactions between anglers and sea turtles are likely to increase as well (Putman et al., 2020a, 2023).

Over the past three decades, reports of sea turtles incidentally captured on hook and line at large recreational fishing piers (i.e., pier captures) have increased across the United States’ Gulf and Atlantic coasts (Cannon et al., 1994; Rudloe and Rudloe, 2005; Seney, 2008; Coleman et al., 2016; Cook et al., 2020; Lawani et al., 2022; Lamont et al., 2022; Rose et al., 2022; Reimer et al., 2023). Piers offer several attractants for sea turtles, such as hard-bottom substrates that support epibenthic food webs (Glasby and Connell, 1999; Seney, 2016). Discarded and active fishing bait around piers also creates opportunistic foraging opportunities for turtles (Shaver, 1991). Thus, fishing piers offer an opportunity to study sea turtle interactions with recreational anglers at discrete locations with concentrated fishing effort. To better understand the nature, extent, outcome, and trends in incidental captures at Florida Gulf piers, we analyzed STSSN records of pier captures (hooked or entangled) over a 23-year period. We also documented the outcome of these interactions by inspecting state records from facilities authorized to rehabilitate injured sea turtles for release. We then modeled capture trends to identify spatial and temporal trends in the daily mean number of reported captures.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Analysis of florida sea turtle stranding and salvage network reports

Sea turtle incidental capture data were obtained from Florida’s STSSN database. In Florida, the Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC) authorizes stranding responders and, in cooperation with the NMFS’s staff, manages the collection of stranding data. Florida’s STSSN consists of biologists, private citizens, and sea turtle rehabilitation facilities authorized by the FWC to rescue, rehabilitate, and release sea turtles. Since the 1980s, Florida’s STSSN program has been collecting data on dead, sick, or injured (i.e., stranded) sea turtles, as well as those incidentally captured by commercial and recreational fishing. The data collected include date, species, location, condition of the turtle, and carapace measurements. Stranded turtles are evaluated for the presence of flipper tags, Passive Integrated Transponder (PIT) tags, living tags, tracking gear, and/or tag scars. FWC-authorized STSSN participants report any anomalies that may have contributed to the turtle’s stranding (e.g., evidence of boat strikes, interactions with anthropogenic material, and signs of disease). Living turtles showing signs of illness or injury are transported to FWC-permitted rehabilitation centers where they are evaluated and treated for their maladies. Upon successful rehabilitation, all turtles are tagged if a tag is not already present (all with a PIT tag and most also with one or more Inconel flipper tags) and released.

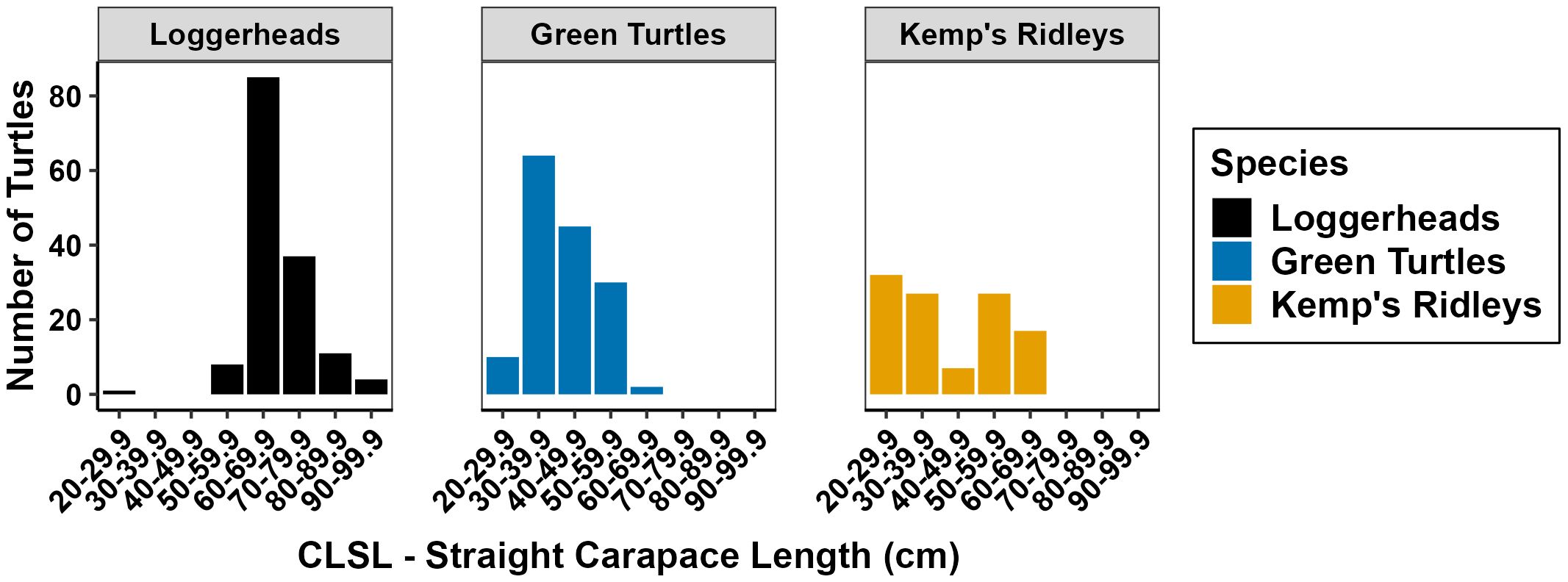

We used R statistical software (v4.3.1; R Core Team, 2022) to filter stranding records and identify the number of pier-captured sea turtles per year in Florida’s Gulf counties, the time of year when captures occurred, and the species and size of each sea turtle. Google Earth (Gorelick et al., 2017, v7.3.6.9796) and ArcGIS Pro (Esri Inc., 2022, v3.0.0) were used to confirm reported GPS coordinates were consistent with existing fishing piers. For the purpose of this report, we limited analysis to municipally owned (i.e., city, county, or state-owned) fishing structures. We did not include piers or docks owned by private individuals or organizations. We reported the means and standard deviations (denoted mean ± SD in results below) for pier-captured turtles by month. Recovered turtles with reported straight carapace length measurements (CLSL: the straight length measurement from the anterior notch to the posterior tip of the carapace) were categorized by size classes based on FWC reporting guidelines (Table 1). We reported the mean and SD of turtle size by species, as well as the percent of each size-class represented by recovered turtles. To assess recapture data, we analyzed the FWC stranding database for repeated flipper and PIT tag entries. We expanded this analysis to Atlantic Coast strandings to identify whether repeat pier captures transported from the Gulf to the Atlantic Coast returned to any Atlantic Coast piers. We then reviewed quarterly rehabilitation facility reports submitted to the FWC to document status and outcome for each turtle.

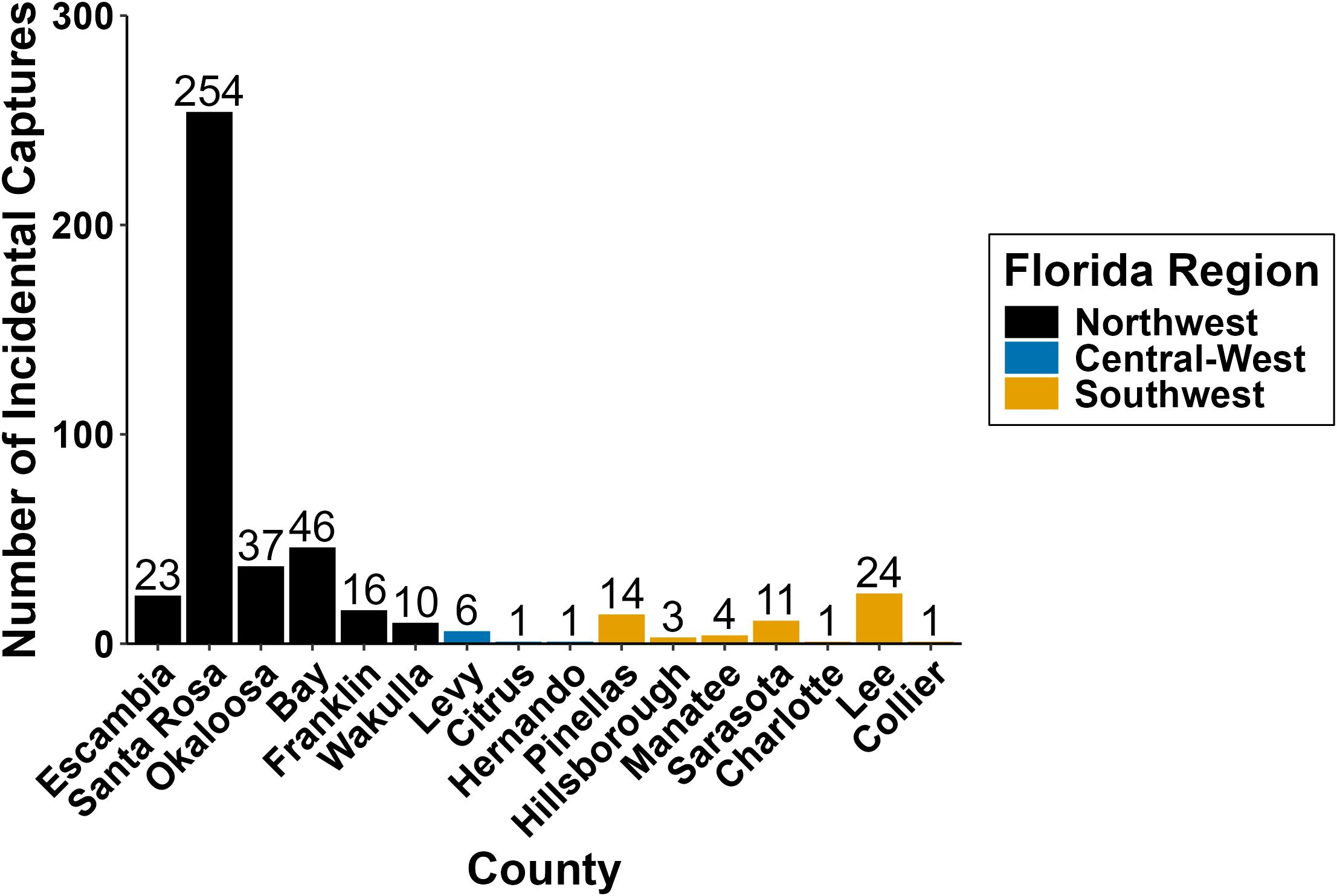

Table 1. Size classifications of sea turtles by species based on straight carapace lengths (CLSL). Corresponds to FL Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission’s rehabilitation quarterly report guidelines.

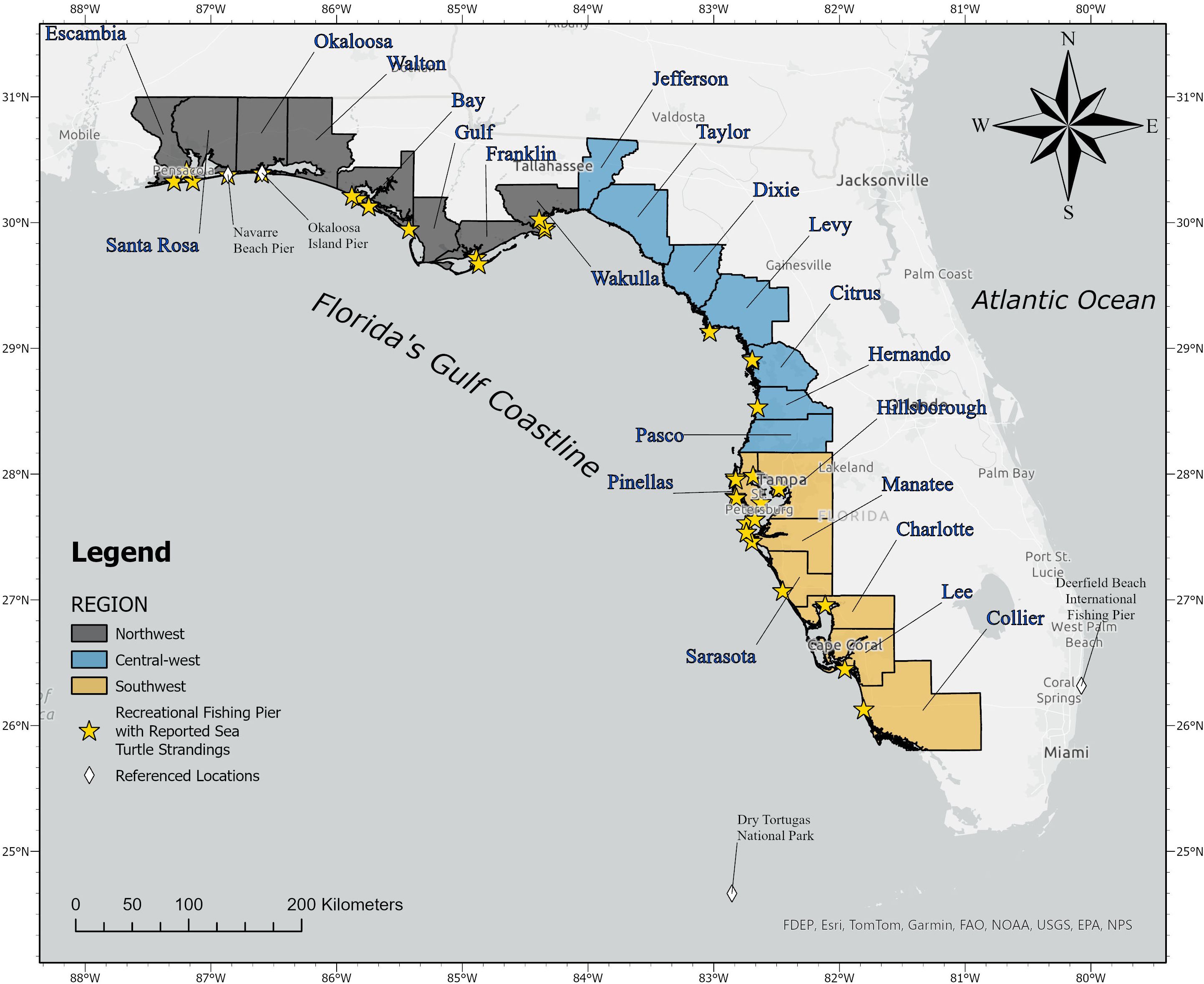

To assess spatial differences in pier captures, coastal counties were organized into three different regions to compare the number of strandings from each region’s piers (Figure 1). Regions were assigned based on coastal geography and by the relative characterization of the types of fishing piers in the area. The Northwest and Southwest regions were characterized by having large, staffed fishing piers that operate under commercial licenses allowing anglers to fish regardless of having a personal license. The Central-west region lacked these large commercial piers and contained smaller, unmanned piers that require personal Florida recreational licenses to fish from. The Northwest region consisted of Escambia, Santa Rosa, Okaloosa, Walton, Bay, Gulf, Franklin, Wakulla, and Jefferson counties. The Central-west region consisted of Taylor, Dixie, Levy, Citrus, Hernando, and Pasco counties. The Southwest region consisted of Pinellas, Hillsborough, Manatee, Sarasota, Charlotte, Lee, and Collier counties.

2.2 Modeling and statistical analysis

We collated data into spreadsheets using Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation, v2403) and imported them into R statistical software for statistical analysis and graphical representation. We compiled all Gulf pier capture reports over the 23-year sampling period by the months they occurred and used a Kruskal-Wallis test (Tagliolatto et al., 2020) to identify significant differences in pier capture rates among months. Dunn’s multiple comparison post-hoc tests with Bonferroni corrected p-values were used to determine significance between different months.

To account for variations in the number of reporting days across piers and years, we generated a large dataset which included every day from January 1, 2000, to December 31, 2022. We repeated this process for every pier identified in the stranding records (n = 33) and every species involved in a pier capture (n = 3). Captured turtles that could not be identified to species level were removed from this analysis (n = 6). Reported captures were entered into the dataset by date of capture, species caught, and the pier where the capture took place. Days with no captures reported at a given pier were assigned a zero value, which represented two possibilities: (1) no turtles were pier-captured on that day or (2) at least one turtle was observed as pier-captured, but no reports were made to STSSN. It is currently impossible to know how frequently pier-captured turtles go unreported, hence for the purposes of this analysis, we explicitly assumed that a zero-observation meant that no turtles were pier-captured on a given day. Because of the spontaneous nature of pier capture events, FWC STSSN staff typically rely on anglers to self-report these events to the FWC Wildlife Alert Hotline. STSSN stranding coordinators monitor calls to the FWC Wildlife Alert hotline every day from 8am to 8pm ET. However, there is no standardized metric to measure differences in fishing or reporting effort across piers, regions, or times of the year. For our model, we assumed equal reporting effort and equal fishing effort across piers and days. Because of these assumptions, our modeled reporting rate for the mean number of turtles pier-captured per day (described below) should be considered a conservative estimate of sea turtle bycatch across Florida’s Gulf Coast.

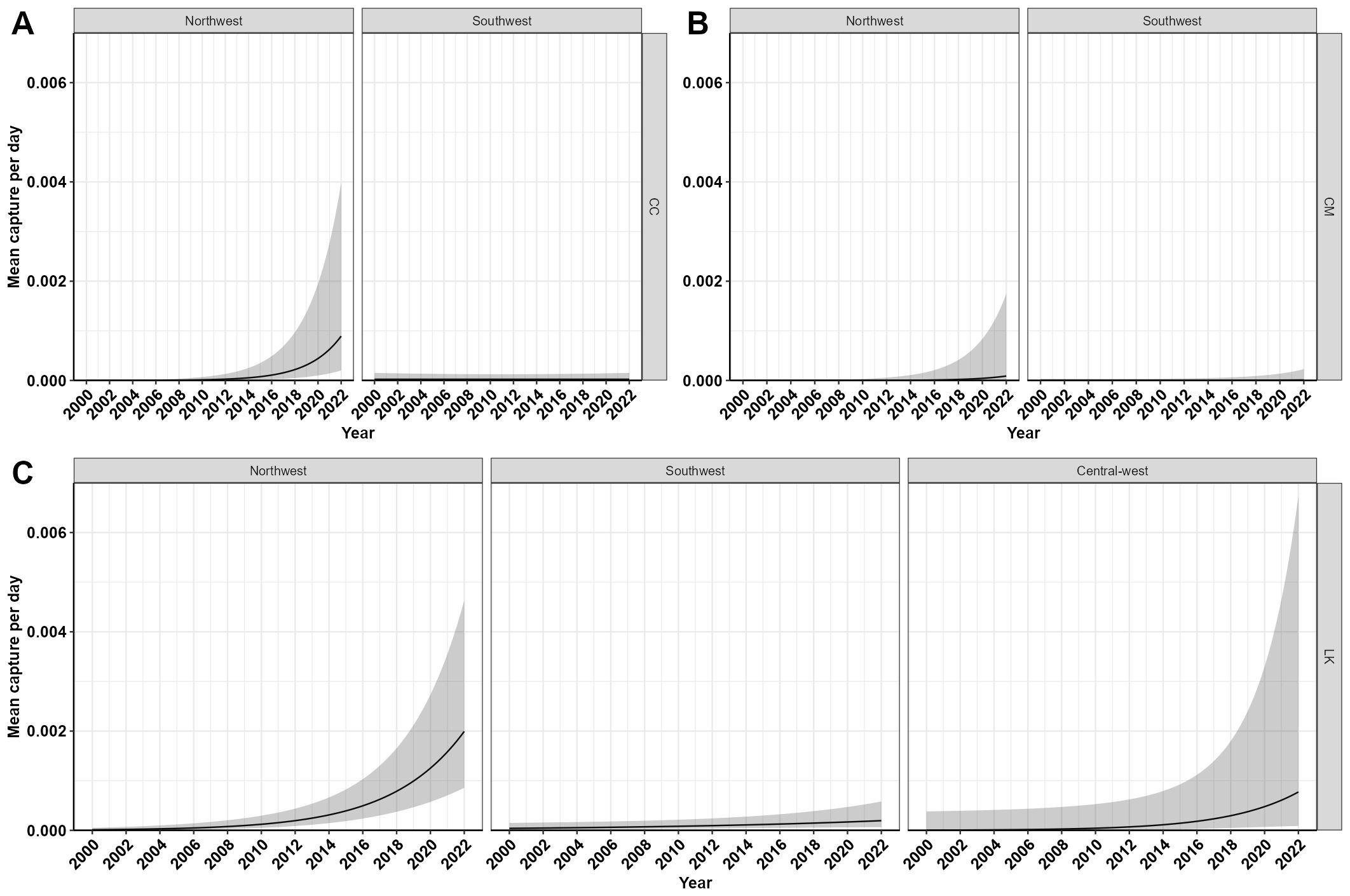

We applied negative binomial generalized linear mixed models (GLMMs; Zuur et al., 2009) to analyze annual and regional trends in the mean number of loggerhead turtles (Caretta caretta), green turtles (Chelonia mydas), and Kemp’s ridley turtles (Lepidochelys kempii) caught per day on Florida’s Gulf fishing piers. Our primary modeling objective was to assess regional trends in turtle pier captures for each species; hence, a separate model was fit to each species’ data. For each species, the model included year as a continuous predictor, region as a categorical predictor, and year × region as an interaction term. For Kemp’s ridleys, region was included as a three-level factor, whereas for green turtles and loggerheads, region was a two-level factor (Northwest and Southwest) because those species were never reported at Central-west piers. To facilitate model fitting and model convergence, the year predictor was standardized to a mean of 0 and standard deviation of 1; hence, parameter estimates associated with year were interpreted as a change in the mean number of incidentally captured turtles reported for Florida’s Gulf piers per every standard deviation increase in year (i.e., each unit increase in the standardized year value equates to approximately 6.68 years). Each model also included an offset representing the number of days within a year that a turtle could be reported as incidentally captured (n = 365 or 366 for leap years), meaning that parameter estimates were interpreted as the expected number of reported turtles per day. Lastly, each model included a pier random intercept variable to account for non-independence of observations collected from the same piers.

All model-fitting was conducted in R using the package `glmmTMB` (Brooks et al., 2017). Goodness-of-fit tests, including tests for uniformity of scaled model residuals and tests for overdispersion and zero-inflation, were conducted for each model using a simulation-based approach, implemented in the R package `DHARMa` (Hartig, 2022). For each species, the `emmeans` package (Lenth, 2023) was used to calculate marginal means and post-hoc contrasts, where contrasts were conducted on a regional basis to test for differences in the mean number of pier-captured turtles reported between the first year (2000) and last year (2022) of observation. The `rstatix` package (v0.7.7; Kassambara, 2023) was used for the Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA test and post-hoc analysis to analyze the number of reported pier captures per month. Finally, the `tidyverse` package (v2.0.0; Wickham et al., 2019) was used for data organization and graphing.

3 Results

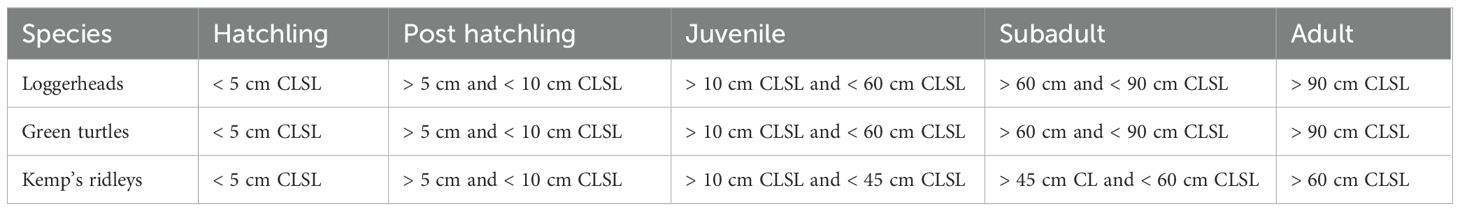

Between 2000 and 2022, we identified 452 pier-capture events on 33 different piers along the Gulf coastline (Figure 1). Santa Rosa County, located within the Northwest region, accounted for 55.8% of all Gulf pier captures (Figure 2, n = 254) over the 23-year period. All Santa Rosa County reports originated from the Navarre Beach Fishing Pier between 2014 and 2022. Bay County and Okaloosa County had the second and third most reported captures with 46 and 37 turtles, respectively. Bay County had four different piers contributing to its total reports, while the 37 reports from Okaloosa County came from the Okaloosa Island Fishing Pier.

Figure 2. Number of sea turtle incidental captures reported in each Florida Gulf Coast county from 2000 to 2022.

The cumulative number of sea turtles caught each month varied significantly over the 23-year study period (Figure 3, Kruskal-Wallis χ2 (11) = 52.21, p < 0.0001, n = 276). Pier captures increased during the spring months and were at significantly higher levels during May and June than early spring, winter or fall levels. Reports generally decreased from July through August and reached their lowest level during the winter months (Table 2). Dunn’s tests revealed that May (4.09 ± 6.33 pier captures) had significantly more captures than February (z = 3.86, p = 0.01), March (z = 3.58, p = 0.02), and December (z = -3.55, p < 0.001). June (4.57 ± 6.04 pier captures) had significantly more captures than January (z = 4.14, p < 0.001), February (p < 0.001), March (z = 4.39, p < 0.001), September (z = -3.41, p = 0.04), November (z = -3.40, p = 0.04), and December (z = -4.36, p = 0.001).

Figure 3. Number of incidental sea turtle captures reported at Gulf recreational fishing piers from 2000-2022. Error bars represent the upper and lower standard deviations surrounding the monthly mean (white filled circle) number of captures. Dots represent reported captures from each year during a given month.

Table 2. The minimum, maximum, median, and mean number of sea turtle pier captures throughout each month from 2000 to 2022.

Pier captures included three different sea turtle species and six turtles that could not be identified down to species (Table 3). Loggerhead turtles were the most commonly caught species (36.3%), followed closely by green turtles (34.1%), and Kemp’s ridleys (28.4%). Capture rates of different species varied from year to year (Figure 4). Green turtles were not reported as pier-captured until 2013. Loggerhead and Kemp’s ridley pier captures have been trending upward since 2019. Of the 446 pier-captured turtles identified to species, responders measured the CLSL of 407 turtles (Figure 5). Mean straight carapace lengths ± SD (size range) were as follows: loggerhead turtles 69.1 ± 8.67 cm (26.9 – 97.9 cm), green turtles 41.8 ± 8.87 cm (21.4 - 66.3 cm), and Kemp’s ridley turtles 42.3 ± 14.2 cm (21.2 – 66.9 cm). Of the 146 measured loggerheads, 6.2% were juvenile, 91.8% were subadult, and 2.1% were adult sized. Of the 110 Kemp’s ridleys measured, 58.2% were juvenile, 26.4% were subadult, and 15.5% were adult sized. Of the 151 green turtles, 98.7% were juvenile while 1.3% were adult sized.

Table 3. Number of sea turtles of each species caught at Florida Gulf Coast recreational fishing piers during 2000-2022.

Figure 4. Number of sea turtles of each species caught by year at Florida Gulf Coast recreational fishing piers during 2000-2022.

Figure 5. Size distribution of incidentally captured sea turtles from Gulf fishing piers during 2000-2022. Size measured as the straight length from the anterior notch to the posterior tip of the carapace.

Overall, outcomes were non-lethal for recovered pier-captured sea turtles (Figure 6). Most turtles (n = 425) survived the initial pier capture. Stranding and rehabilitation teams successfully rescued, rehabilitated, and released 85% of reported pier-captures (a total of 383 turtles returned to the water). A single turtle was unable to be released and was moved to an FWC-authorized facility for educational display. There were 41 reports where the turtle was either “immediately released” or “not recovered” during the pier capture. These reports included turtles released by the angler before responding organizations could recover the animal, turtles that broke the line before recovery, and turtles released onsite by responders or veterinary staff. More recent agency protocols require responders to designate turtles as “Not Recovered” when turtles cannot be recovered by STSSN members. Pier capture reports indicated fatality in 6% of cases. Twenty-five turtles succumbed to their wounds after being brought to a rehabilitation facility. An additional two turtles were listed as “Not Recovered” due to perishing before or during rescue efforts.

Figure 6. Outcome of turtles (n = 452) involved in incidental captures at Gulf recreational fishing piers from 2000-2022.

For the 452 pier- capture events, a scan for PIT tags and a check for external flipper tags were conducted 413 times by STSSN responders and rehabilitation center staff. Existing tags (either internal, external, or both) were documented in 187 of these reports. Flipper and passive integrated transponder (PIT) tag analysis revealed high recapture rates among pier-captured turtles. We identified 168 pier-capture events that were attributed to 59 individuals. Most recaptures occurred in the Northwest region, with 87.5% of recaptures occurring at the Navarre Beach Fishing Pier. Recaptures showed high site fidelity, with all but two turtles returning to the same pier. One turtle in Panama City Beach was recaptured 685 days later at a pier approximately 5 km southwest of its original point of capture. Another turtle was captured at the Navarre Beach Pier and recaptured 39 days later at the Okaloosa Island Pier approximately 26 km west of its original point of capture. Of the 59 recaptured turtles, 57.5% were caught twice, 25.4% were caught three times, 13% were caught four times, 5.1% were caught five times, and 3.4% were caught seven times. The interval between recaptures ranged from 1–2417 days (Mean = 235.09 days, SD = 305.4).

In five instances, subadult loggerhead sea turtles (CLSL ranged from 61–70 cm, sex undetermined) captured more than five times on Gulf piers were released on the Atlantic Coast to reduce the potential for returning to the original capture site. A subsequent review of PIT tags from these Gulf turtles against Atlantic stranding reports identified two additional Pier captures involving a single Gulf turtle. After three Navarre Pier captures, FWC staff authorized the release of a loggerhead turtle into the northeast Florida Atlantic in 2020. This turtle was subsequently captured at Deerfield Beach International Fishing Pier (Deerfield, FL on the southeast Florida Atlantic Coast, Figure 1) in late 2021. After rehabilitation, FWC staff authorized the release of this turtle in the Dry Tortugas (lower southwest Gulf Florida Coast). This animal was recaptured at the Navarre pier in 2022, and after rehabilitation and release into the Atlantic, it was again captured at Deerfield Pier in later 2022.

GLM modeling revealed significant effects of the standardized year on the mean number of reported loggerhead and green turtle captures at Gulf piers per day (Figure 7), although the effect was not significant at p≤ 0.05 for Kemp’s ridley turtles (p = 0.056). Loggerhead and green turtles were reported as pier captures in the Northwest and Southwest regions, but neither of these species were reported in the Central-west region. Loggerhead pier captures showed a significant interaction effect between the region and the year (Estimate = -2.334, z-value = -6.423, p < 0.000). Parameter estimates, marginal means, and post-hoc contrasts revealed significant differences in the daily number of pier-captured sea turtles in the Northwest region between 2000 and 2022 (Supplementary Tables 1, 2). Notably, capture rates for all three species increased between 2000 and 2022 within the Northwest region (Table 3). Kemp’s ridley turtles were pier captured in all three regions throughout the period analyzed. Kemp’s ridley turtle pier captures significantly increased in the Southwest region as well between the first and final year of the observed period. Marginal increases in mean pier-captures were seen in Kemp’s ridleys in the Central-west region; however, they were not significantly different from the start of the observed time frame to the end of the observed time frame (p > 0.0564). Finally, goodness-of-fit diagnostics simulated through the DHARMa package indicated that all negative binomial regression models provided an adequate fit to the pier-capture data.

Figure 7. Annual predicted mean number of pier-captured turtles per day at Gulf fishing piers based on the negative binomial model results. (A) represents loggerheads (CC, Caretta caretta), (B) represents green sea turtles (CM, Chelonia mydas), and (C) represents Kemp’s ridley sea turtles (LK, Lepidochelys kempii).

4 Discussion

Daily mean numbers of sea turtles pier-captured on Florida Gulf recreational fishing piers were relatively small, indicating that reported events were rare throughout time and over a large geographic area. A previous analysis of Florida’s STSSN records from 1986 to 2014 documented 187 pier-capture events across the entire state of Florida, with 105 events reported at Gulf piers specifically (Foley et al., 2014). These numbers represented approximately 0.004% of all reported strandings from 1980 – 2014; however, the authors noted significant increases in reported pier captures throughout the time period. While our study overlapped this previous analysis from 2000 to 2014, our findings highlighted similar increasing trends in the reported impact of recreational fishing on sea turtles going back to the late 1980s. Our data showed similar rarity in reported events, with pier strandings representing 0.008% of all reported strandings. Nevertheless, GLM modeling suggested these reports were significantly increasing throughout time on regional scales. Given the potential for pier strandings to go undocumented (Cook et al., 2020; Rose et al., 2022) and the disproportionate impacts of removing juvenile and adult females from populations in recovery (Crouse et al., 1987), measures that increase angler awareness, minimize potential interactions, and promote safe and efficient recoveries of incidentally caught sea turtles should be implemented at piers to minimize unreported and negative interactions.

Incidental captures at Gulf fishing piers included three of the five sea turtle species found throughout Gulf waters: loggerheads, Kemp’s ridleys, and green sea turtles. Juvenile, subadult, and adult size turtles were represented in the loggerhead and Kemp’s ridley captures. Most pier captured green turtles were juvenile-size, with two being subadult size. Captures of juvenile turtles in the Northwest region may be driven by increased hatchling output at nesting beaches and increased use of Gulf nearshore areas as foraging and developmental habitat (Gallaway et al., 2016; van der Zee et al., 2019; Putman et al., 2020b, 2023). Tracking studies identified the bays and estuaries throughout the Northwest Florida region as important foraging grounds for all three species (Eaton et al., 2008; Lamont and Iverson, 2018; Putman et al., 2023). Oceanic circulation models that investigated Kemp’s ridley, green turtle, and loggerhead hatchling dispersal from rookery sites predicted increased densities of juvenile turtles aggregating in the northern Gulf (Putman et al., 2020b). Genetic studies also documented increased connectivity from green turtle rookeries along Mexico’s Gulf Coast and the Yucatan Peninsula to foraging grounds in the northern Gulf (Phillips et al., 2022; Shamblin et al., 2023). Increased nest numbers have been observed on many of these beaches along the southern Gulf coastline as well, though reproductive success and hatchling production have remained relatively stable over time (López-Castro et al., 2022). Both loggerhead and green turtle nest numbers have increased in Southwest Florida over the past 40 years (Lasala et al., 2023). More localized inputs may contribute to increased juvenile recruitment over time if oceanic currents and active swimming lead to retention of juveniles within the area (Jensen et al., 2016; Putman et al., 2020b), but further study is warranted to identify dispersal patterns of juveniles originating from Florida Gulf rookeries.

Captures may also be biased to smaller turtles due to the difficulty in recovering larger turtles from high piers. Anecdotal reports from Virginia (Rose et al., 2022) and from Florida response teams noted that larger turtles often broke the line before responders could recover them. However, this is difficult to confirm since no measurement data exists for these non-recovered turtles. Incidents of turtles breaking the line before responders are notified are also less likely to be reported to the STSSN. Given the potential for lethal and sublethal injuries from trailing line and internal hooks on non-recovered turtles (Bjorndal et al., 1994; Oros et al., 2004; Valente et al., 2007; Casale et al., 2008; Parga, 2012), piers where larger turtles are captured may need additional resources to ensure the successful recovery of these animals.

Modeling results indicated significant increases in the mean number of pier-captured loggerheads and greens per day were driven primarily by pier captures in Northwest Florida. Post-hoc contrasts of estimated marginal means further identified significant increases in captures of all three species within the Northwest region. While significant cumulative increases in mean captures per day by year were not observed in Kemp’s ridleys, significant increases in the numbers of this species captured were detected in Northwest Florida when comparing the beginning and end of the time series. Future studies should assess whether sea turtles within the Southwest and Central-west regions have the same rates of occurrence around piers as those in the Northwest region. Preliminary data from sea turtle abundance surveys at piers suggest fewer reports of sea turtles at southwestern sites, though this sampling data is restricted to only two locations in the southwest at small temporal scales (FWC unpublished data). It is likely that reporting effort varies from region to region based on angler willingness or knowledge to report incidental captures (Cook et al., 2020; Henry et al., 2025). If turtles are indeed present around these piers at similar rates and are being hooked but not reported to STSSN, then increased resources to communicate and educate anglers on the need for reporting may promote better rescue attempts.

Kemp’s ridley turtles were historically the most common sea turtle species documented as pier-captured, followed by loggerheads (Cannon et al., 1994; Rudloe and Rudloe, 2005; Seney, 2008; Foley et al., 2014; Coleman et al., 2016; Rose et al., 2022). The increased number of green turtle pier captures, first documented in 2022 (Lawani et al., 2022; Lamont et al., 2022), could be attributed to the increase in green turtle numbers across the Gulf (López-Castro et al., 2022; Lasala et al., 2023). Recent modeling highlighted spatial overlap between juvenile Kemp’s ridley and green turtle foraging grounds and areas of increased recreational fishing activity (Putman et al., 2023). When accounting for relative abundance of each species, Kemp’s ridley turtles were projected to have a higher risk of bycatch in recreational fisheries due to habitat overlap and foraging behaviors, while the mainly herbivorous diet of green turtles was thought to preclude them from most fishing risk (Putman et al., 2023). Our results showed a spike in juvenile green turtle pier-captures in the mid-2010s, which has since declined. The large amount of juvenile green turtle captures may reflect a cohort of young turtles recruiting to nearshore environments that still display omnivorous feeding strategies. Juvenile green turtles recruiting to inshore foraging grounds have been documented with omnivorous feeding strategies that may include invertebrates found around piers or opportunistic scavenging of bait (Cardona et al., 2009; Howell et al., 2016; Howell and Shaver, 2021). Contrary to the decline in green capture rates, Kemp’s ridley captures were reportedly increasing over the last three years of the study.

Sea turtles caught and recovered on Gulf fishing piers exhibited high recovery rates and low incidents of mortality. FWC procedures require recovered pier captures to be examined by a vet who determines suitability for release, but we do not know if the experience leads to reduced fitness following rehabilitation. The high recapture rate (discussed below) confirmed initial survivorship for 59 individuals post-release. Few studies have quantified the mortality associated with hook and line interactions from recreational fisheries specifically. Virginia rehabilitators reported a 99% survival rate of 170 turtles caught at piers, with only two Kemp’s ridley turtles succumbing to wounds involving hook trauma (Rose et al., 2022). A long-term analysis of green turtle strandings in the Hawaiian Islands found that recreational hook and line interactions were a common cause of stranding for green turtles, but it was the least-likely interaction to result in death of a turtle (Chaloupka et al., 2008). Mortality and sublethal effects from hook and line interactions have largely been derived from analyses of commercial fisheries bycatch. Analysis of a small sample of loggerhead turtles captured after deeply ingesting hooks from the Spanish swordfish longline industry showed a mortality rate between 20 to 30% (Aguilar et al., 1995). The NMFS estimated mortality rates of 17 to 42% for loggerheads caught in the Pacific long-line industry (National Marine Fisheries Service Southeast Fisheries Science Center, 2001). Some studies noted that hooks can pass or break down over time without medical assistance (Werneck et al., 2008; Heaton et al., 2016), though this likely varies based on the hook’s composition and size. Further, internal wounds from hook and line can cause infections that reduce a turtle’s chances of survival (Oros et al., 2004). Incidentally-caught turtles released without medical assistance may suffer sub-lethal or lethal effects from their experience. They may succumb to their wounds or re-strand at a later time. Broken or cut lines from non-recovered turtles also increase the chances of entanglement or damage to the GI tract that can result in mortality (Bjorndal et al., 1994; Oros et al., 2004; Valente et al., 2007; Casale et al., 2008; Parga, 2012). These threats highlight the need for management strategies to prevent pier captures as well as the need for efficient response strategies that promote recovery and transport of pier-captured sea turtles to rehabilitation centers.

Recaptures accounted for over a third of reported incidental captures, suggesting turtles have strong site fidelity to foraging grounds surrounding the piers. Juvenile homing behaviors to foraging grounds have been documented in multiple sea turtle species. Juvenile loggerheads displaced from their original foraging grounds were recaptured close to their original capture location (Avens et al., 2003). Another study reported that displaced juvenile greens and loggerheads oriented their swimming patterns toward direct routes back to their original foraging habitat (Avens and Lohmann, 2004). Previous research on pier-captured turtles documented high site fidelity to piers in the Mississippi Sound (Coleman et al., 2016) and in Northwest Florida (Rudloe and Rudloe, 2005; Lamont et al., 2022). A Kemp’s ridley turtle captured in Virginia was transported 30 km from its initial capture location. This animal was recaptured a week later within 7 km of its origin (Rose et al., 2022). Kemp’s ridley turtles captured at Texas piers did not display high site fidelity, possibly due to a lack of tag returns and release sites far away from the point of origin (Seney, 2008). The FWC has authorized release of repetitively recaptured turtles farther away from the point of origin to prevent further habituation to specific piers. However, this strategy requires additional logistics to transport turtles considerable distances across the state. Relocation and reintroduction to a new environment may also cause stress for recaptured sea turtles. Pier-captured turtles released in different environments may still rely on foraging strategies that bring them to piers within their new environment. While it represents a single data point, the turtle recaptured on both Gulf and Atlantic Coast piers is concerning. Future studies should explore the movement patterns of turtles released in this manner to better understand their habitat use.

Regional drivers of pier-capture depend on the number of turtles present to be captured and the fishing effort associated with a given area (Chaloupka et al., 2008; Putman et al., 2020a). The NMFS’ Marine Recreational Fishing Program (MRIP) monitors fishing efforts at piers and docks. Putman et al. (2023) noted significant increases in MRIP-derived recreational fishing effort across the Atlantic and the Gulf of Mexico from 1996 to 2017. Significant seasonal variation in the number of cumulative pier captures throughout all years aligned with previous reports, which noted increased pier-captures in the late spring-early summer (Coleman et al., 2016; Rose et al., 2022). These seasonal variations are potentially due to overlap in human fishing behavior and seasonal migration patterns. Cooler temperatures and reduced tourism during the winter months in the northern Gulf may reduce shore-based fishing effort. While St Joseph’s Bay in the Northwest region supports a year-round aggregation of turtles active in the winter months, turtles have been documented moving to deeper waters during the cooler seasons (Lamont et al., 2018; Lamont and Iverson, 2018; Lamont et al., 2024).

Sea turtle foraging and habitat usage around piers and surrounding hard-bottom structures likely contribute to incidental captures. Sea turtles likely forage on algae and invertebrate communities that use pier pilings as structural habitat (Glasby and Connell, 1999). Loggerheads and Kemp’s ridleys have been documented feeding on fisheries discards (Houghton et al., 2000; Tomas et al., 2001; Seney and Musick, 2007; Peckham et al., 2011; Coleman et al., 2016). This scavenging behavior may be a learned response to compensate for declines in invertebrate prey populations (Seney and Musick, 2007; Coleman et al., 2016). A recent modeling study examining foraging of juvenile Kemp’s ridleys suggested higher per capita food availability offshore across the West Florida Shelf than in more nearshore areas (Scott et al., 2024), which could suggest that neritic-stage juveniles and adults may have higher rates of competition for prey items when foraging in nearshore habitat, leading to more instances of supplemental scavenging from baited hooks, or pier discards.

Sea turtles also use artificial reefs as resting and foraging locations (Barnette, 2017), and a recent spatial analysis suggested that increased presence and size of artificial reefs near fishing piers positively predicted increased incidental capture of sea turtles (Reimer et al., 2023). While the majority of artificial reefs off Florida’s Gulf coast are located more than 2 km offshore, approximately 39 patch reefs have been installed within 2000-feet of the Gulf shoreline in the Northwest region since 2012 (FWC Division of Marine Fisheries Management, 2025).More recently, turtles have been documented using snorkeling reefs within close proximity (approximately 1-1.6 km) to the Navarre Beach Fishing Pier and the Okaloosa Island Pier (Siegfried et al., 2021). Other biological and environmental factors must also be considered for this regional increase, but future artificial reef planning may need to consider distances from shoreline fishing hotspots to prevent attracting sea turtles to riskier areas. Future studies should also investigate movement and foraging patterns of sea turtles using artificial structures across the coast.

For our GLM model, we assumed that each pier had a similar reporting effort every day throughout the study period. Future analyses may benefit in developing a reporting effort parameter as piers exist in different ecosystems that affect the rate of reported bycatch. Recent changes to pier management reporting requirements, along with increased outreach and education efforts, may have resulted in an increased likelihood of anglers reporting turtles to STSSN responders. Over the past thirty years, many of Florida’s new piers were required by the FWC and the FL Department of Environmental Protection to have management plans that dictate specific reporting and mitigation requirements for threatened and endangered species incidentally caught at those piers. Outreach efforts in Mississippi and Virginia aimed at educating pier anglers to report hooked sea turtles resulted in increased reporting of pier captures from each state (Cook et al., 2020; Rose et al., 2022). Similar efforts have been undertaken by sea turtle conservation organizations across Florida. The Loggerhead MarineLife Center’s Responsible Pier Initiative (RPI) began coordinating with piers and STSSN responders in the mid-2010s to increase angler awareness and reporting of hooked sea turtles at fishing piers (RPI public data). Other groups in areas of high reported pier captures, including the Navarre Beach Sea Turtle Conservation Center (NBSTCC, Navarre, FL), the Gulfarium CARE Center (Conserve Act Rehabilitate Educate, Ft. Walton Beach, FL), and the Gulf World Marine Institute (Panama City Beach, FL), have created programs to engage local stakeholders to report and aide in recovering pier-hooked sea turtles. Similar programs work with piers throughout the Central-west and Southwest regions of Florida (Gulf Specimen Marine Lab in Panacea, University of Florida Marine Animal Rescue Program in Chiefland, Clearwater Marine Aquarium in Clearwater Beach, Florida Aquarium in Tampa, Mote Marine Lab in Sarasota, The Conservancy of Southwest Florida in Naples, and the Clinic for the Rehabilitation of Wildlife in Sanibel). These conservation groups have mobilized volunteer networks and created working relationships with pier staff and angler communities, which potentially has helped increase the reporting and recovery of hooked sea turtles.

Though the mean number of pier captures per day followed an exponentially increasing pattern, the order of magnitude of these increases was small when contextualized with how often these events were reported throughout the years across large geographic ranges. We have discussed multiple potential causative agents for the regional increases in reported captures, which may be acting individually or synergistically. While these increases are relatively small, regional increases can still overwhelm response and rehabilitation teams dealing with more pier patients on top of other strandings. Rehabilitation centers also struggle with the increased financial burden of treatment expenses for each animal. Our estimates are also conservative because of our assumption that days with zero reported events reflect no bycatch. It is unknown how many events go unreported due to fear of legal repercussions for hooking an endangered species or because anglers do not know that the event should be reported (Cook et al., 2020; Henry et al., 2025). Further, previous STSSN records may under-represent the number of turtles that broke the line or had the line cut. Recent changes to the Florida STSSN reporting methodology require all turtles that are caught or hooked in recreational fishing gear to be reported, regardless of whether the sea turtle was recovered or not. Finally, public education efforts to minimize potential interactions with sea turtles around piers, combined with increased resources for recovery and rehabilitation of captured animals, should be implemented in areas with higher rates of incidental capture. Enhancing education on best practices for avoiding and handling incidental captures can help support conservation while allowing for responsible recreational fishing. These actions can benefit recreational fisheries by limiting negative interactions with a non-target, endangered species, thereby bolstering conservation efforts for threatened and endangered sea turtles.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the study involving animals in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements because this work involved sea turtles incidentally captured during legal recreational fishing activities that were recovered under Florida’s Sea Turtle Stranding and Salvage Network. Florida’s sea turtle stranding, salvage, and rehabilitation tasks are conducted under an Endangered Species Act Section 6 Cooperative Agreement between the FWC and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Stranding and salvage teams across the state work under FWC-issued Marine Turtle Permits as allowed by the Section 6 Cooperative Agreement and Florida State Statute.

Author contributions

RB: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Methodology. KM: Data curation, Methodology, Resources, Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Validation, Supervision. MW: Data curation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Resources, Validation, Supervision. MK: Data curation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Resources, Validation, Supervision, Conceptualization. CS: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Resources, Validation, Visualization. AF: Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Validation. RT: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Validation.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. Funding for FWC staff was provided by the Florida Sea Turtle License Plate with additional funding from the National Marine Fisheries Service (grants from NOAA’s Species Recovery Grants to States and from the NMFS Southeast Regional Office) for the STSSN program. Funding for this project was provided by the Florida Trustee Implementation Group as part of the Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill Natural Resource Damage Assessment process, Gulf Spill Restoration Project ID 278.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the many participants in Florida’s Stranding and Salvage Network and all of Florida’s sea turtle rehabilitation teams for their hard work and dedication. We would like to thank Maria Merrill and the FWC Department of Marine Fisheries Management, especially Erica Burgess, Keith Mille, and Rae Rodriguez, for reviewing the manuscript and providing comments on recreational fisheries and artificial reefs topics.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. ChatGPT (OpenAI, 2024) was used on an initial draft of the manuscript to identify grammar usage of active voice versus passive voice. All ChatGPT suggestions for edits were reviewed and edited by the corresponding author before being accepted. Suggested edits were checked for correct grammar and context in relation to the overall text.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmars.2025.1686607/full#supplementary-material

Supplementary Table 1 | Parameter estimates, standard errors (SE), lower and upper 95% confidence limits, z-values (Estimate/SE), and p-values from the negative binomial regression models relating year and region to the mean number of turtles caught at piers. All values are on the natural log scale, all estimates are interpreted as the expected number of strandings per day due to the inclusion of an offset, and all random effects are expressed as standard deviations. Year was standardized for model fitting so coefficients associated with year for each species are interpreted as the change in mean number of incidental captures for every one standard deviation increase in year, or 6.64 years.

Supplementary Table 2 | Marginal means, pairwise contrasts (Difference), standard errors, lower and upper 95% confidence limits, z-values (Difference/SE), and p-values based on the negative binomial regression models relating year and region to the mean number of loggerhead, green, and Kemp’s ridley sea turtles caught at piers. Marginal means and pairwise contrasts are reported on the response and natural log scale, respectively. All marginal means and contrasts are interpreted as the expected number of strandings at piers per day due to the inclusion of an offset in the regression models.

References

Aguilar R., Mas J., and Pastor X. (1995). “Impact of the Spanish swordfish long-line fisheries on the loggerhead sea turtle (Caretta caretta) population in the western Mediterranean,” in Proceedings of the 12th Annual Workshop on Sea Turtle Biology and Conservation. Eds. Richardson J. I. and Richardson T. H. (Jekyll Island, GA: NOAA Technical Memorandum, NMFS-SEFSC) 361, 1–16.

Alegre F., Parga M., Castillo C., and Pont S. (2006). “Study on the long-term effect of hooks lodged in the mid-esophagus of sea turtles,” in Twenty-sixth Annual Symposium on Sea Turtle Biology and Conservation Book of Abstracts eds. Frick M., Panagopoulou A., Rees A. F., and Williams K. (Athens, Greece: International Sea Turtle Society). 234.

Alfaro-Shigueto J., Mangel J. C., Bernedo F., Dutton P. H., Seminoff J. A., and Godley B. J. (2011). Small-scale fisheries of Peru: a major sink for marine turtles in the Pacific. J. Appl. Ecol. 48, 1432–1440. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2664.2011.02040

Avens L., Braun-McNeill J., Epperly S., and Lohmann K. J. (2003). Site fidelity and homing behavior in juvenile loggerhead sea turtles (Caretta caretta). Mar. Biol. 143, 211–220. doi: 10.1007/s00227-003-1085-9

Avens L. and Lohmann K. J. (2004). Navigation and seasonal migratory orientation in juvenile sea turtles. J. Exp. Biol. 207, 1771–1778. doi: 10.1242/jeb.00946

Barnette M. C. (2017). Potential impacts of artificial reef development on sea turtle conservation in Florida (St. Petersburg, FL: NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-SER-5), 36. doi: 10.7289/V5/TM-NMFS-SER-5

Bjorndal K. A., Bolten A. B., and Lagueux C. J. (1994). Ingestion of marine debris by juvenile sea turtles in coastal Florida habitats. Mar. pollut. Bull. 28, 154–158. doi: 10.1016/0025-326X(94)90391-3

Brooks M. E., Kristensen K., van Benthem K. J., Magnusson A., Berg C. W., Nielsen A., et al. (2017). glmmTMB balances speed and flexibility among packages for zero-inflated generalized linear mixed modeling. R. J. 9, 378–400. doi: 10.32614/RJ-2017-066

Cannon A. C., Fontaine C. T., Williams T. D., Revera D. B., and Caillouet C. W. Jr. (1994). Incidental catch of Kemp’s ridley sea turtles (Lepidochelys kempi), by hook and line, along the Texas coast 1980-1992 in Proceedings of the Thirteenth Annual Symposium on Sea Turtle Biology and Conservation eds. Schroeder B. A. and Witherington B. E. (Jekyll Island, Georgia: NOAA technical memorandum NMFS-SEFSC) 341, 40–42.

Cardona L., Aguilar A., and Pazos L. (2009). Delayed ontogenic dietary shift and high levels of omnivory in green turtles (Chelonia mydas) from the NW coast of Africa. Mar. Biol. 156, 1487–1495. doi: 10.1007/s00227-009-1188-z

Casale P., Freggi D., and Rocco M. (2008). Mortality induced by drifting longline hooks and branchlines in loggerhead sea turtles, estimated through observation in captivity. Aquat. Conserv.: Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 18, 945–954. doi: 10.1002/aqc.894

Chaloupka M., Work T. M., Balazs G. H., Murakawa S. K., and Morris R. (2008). Cause-specific temporal and spatial trends in green sea turtle strandings in the Hawaiian Archipelago, (1982–2003. Mar. Biol. 154, 887–898. doi: 10.1007/s00227-008-0981-4

Coleman A. T., Pulis E. E., Pitchford J. L., Crocker K., Heaton A. J., Carron A. M., et al. (2016). Population ecology and rehabilitation of incidentally captured Kemp’s ridley sea turtles (Lepidochelys kempii) in the Mississippi Sound, USA. Herpetol. Conserv. Biol. 11, 253–264.

Cook M., Dunch V. S., and Coleman A. T. (2020). An interview-based approach to assess angler practices and sea turtle captures on Mississippi fishing piers. Front. Mar. Sci. 7. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2020.00655

Crouse D. T., Crowder L. B., and Caswell H. (1987). A stage-based population model for loggerhead sea turtles and implications for conservation. Ecology 68, 1412–1423. doi: 10.2307/1939225

Eaton C., McMichael E., Witherington B., Foley A., Hardy R., and Meylan A. (2008). In-water sea turtle monitoring and research in Florida: review and recommendations (Silver Spring, MD: U.S. Dep. Commerce, NOAA Tech. Memo. NMFS-OPR-38), 233.

Finkbeiner E. M., Wallace B. P., Moore J. E., Lewison R. L., Crowder L. B., and Read A. J. (2011). Cumulative estimates of sea turtle bycatch and mortality in USA fisheries between 1990 and 2007. Biol. Conserv. 144, 2719–2727. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2011.07.033

Foley A. M., Minch K., Hardy R., Bailey R., Schaf S., and Young M. (2014). Distributions, relative abundances, and mortality factors of sea turtles in Florida during 1980–2014 as determined from strandings. Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission Report (Jacksonville, FL: Fish and Wildlife Research Institute).

Font T., Lloret J., and Piante C. (2012). Recreational fishing within marine protected areas in the Mediterranean. MedPAN North Project (France: WWF).

FWC Division of Marine Fisheries Management (2024). Data from: State of Florida Artificial Reef Locations (as of May 1, 2024). Artificial Reef Program. Available online at: https://myfwc.com/fishing/saltwater/artificial-reefs/locate/ (Accessed May 2, 2025).

FWC Division of Marine Fisheries Management (2025). Available online at: https://myfwc.com/fishing/saltwater/artificial-reefs/ (Accessed May 2, 2025).

Gallaway B. J., Gazey W. J., Caillouet C. W., Plotkin P. T., Abreu Grobois F. A., Amos A. F., et al. (2016). Development of a Kemp’s ridley sea turtle stock assessment model. Gulf. Mexico. Sci. 33, 138–157. doi: 10.18785/goms.3302.03

Glasby T. M. and Connell S. D. (1999). Urban structures as marine habitats. Ambio 28, 595–598. doi: 10.1016/S0141-1136(00)00266-X

Gorelick N., Hancher M., Dixon M., Ilyushchenko S., Thau D., and Moore R. (2017).Google Earth Engine: Planetary-scale geospatial analysis for everyone. Remote Sensing of Environment. (Accessed December 12, 2023).

Grimm K. E., Mancini A., Seminoff J. A., Alfaro-Shigueto J., Andrade Valencia V., Barragán Rocha A. R., et al. (2025). Fisher-based assessments of sea turtle bycatch in small-scale fisheries in Pacific Mexico. Endang. Species. Res. 58, 205–221. doi: 10.3354/esr01446

Hartig F. (2022). DHARMa: residual diagnostics for hierarchical (multi-level/mixed) regression models. R package version 0.4.7. Available online at: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=DHARMa (Accessed December 1, 2024).

Heaton A. J., Pulis E. E., Pitchford J. L., Hatchett W. L., Carron A. M., and Solangi M. (2016). Prevalence and transience of ingested fishing hooks in Kemp’s ridley sea turtles. Chelonian. Conserv. Biol. 15, 257–264. doi: 10.2744/CCB-1227.1

Henry H., Olivas T., Gumbleton S., Beckham N., Steury T. D., Willoughby J. R., et al. (2025). Willingness of recreational anglers to modify hook and bait choices for sea turtle conservation in mobile bay, Alabama, gulf of Mexico. Fish. Manage. Ecol. 32, e12766. doi: 10.1111/fme.12766

Houghton J. D., Woolmer A., and Hays G. C.(2000).Sea turtle diving and foraging behaviour around the Greek Island of Kefalonia. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. U. K. 80, 761–762.doi: 10.1017/S002531540000271X

Howell L. N., Reich K. J., Shaver D. J., Landry A. M. Jr., and Gorga C. C. (2016). Ontogenetic shifts in diet and habitat of juvenile green sea turtles in the northwestern Gulf of Mexico. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 559, 217–229. doi: 10.3354/meps11897

Howell L. N. and Shaver D. J. (2021). Foraging habits of green sea turtles (Chelonia mydas) in the northwestern Gulf of Mexico. Front. Mar. Sci. 8. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2021.658368

Hughes R. M. (2015). Recreational fisheries in the USA: economics, management strategies, and ecological threats. Fish. Sci. 81, 1–9. doi: 10.1007/s12562-014-0815-x

Hyder K., Maravelias C. D., Kraan M., Radford Z., and Prellezo R. (2020). Marine recreational fisheries—current state and future opportunities. ICES. J. Mar. Sci. 77, 2171–2180. doi: 10.1093/icesjms/fsaa147

Jensen M. P., Bell I., Limpus C. J., Hamann M., Ambar S., Whap T., et al. (2016). Spatial and temporal genetic variation among size classes of green turtles (Chelonia mydas) provides information on oceanic dispersal and population dynamics. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 543, 241–256. doi: 10.3354/meps11521

Kassambara A. (2023). rstatix: Pipe-Friendly Framework for Basic Statistical Tests. R package version 0.7.2. Available online at: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=rstatix (Accessed September 1, 2023).

Keithly W. R. Jr. and Roberts K. J. (2017). “Commercial and recreational fisheries of the Gulf of Mexico,” in Habitats and Biota of the Gulf of Mexico: Before the Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill Ed. Ward C. H. (New York, NY: Springer) 2, 1039–1188.

Lamont M. M. and Iverson A. R. (2018). Shared habitat use by juveniles of three sea turtle species. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 606, 187–200. doi: 10.3354/meps12748

Lamont M. M., Mollenhauer R., and Foley A. M. (2022). Capture vulnerability of sea turtles on recreational fishing piers. Ecol. Evol. 12, e8473. doi: 10.1002/ece3.8473

Lamont M. M., Seay D. R., and Gault K. (2018). Overwintering behavior of juvenile sea turtles at a temperate foraging ground. Ecology 99, 2621–2624. doi: 10.1002/ecy.2439

Lamont M. M., Slone D., Reid J. P., Butler S. M., and Alday J. (2024). Deep vs shallow: GPS tags reveal a dichotomy in movement patterns of loggerhead turtles foraging in a coastal bay. Movement. Ecol. 12, 40. doi: 10.1186/s40462-024-00480-y

Lasala J. A., Macksey M. C., Mazzarella K. T., Main K. L., Foote J. J., and Tucker A. D. (2023). Forty years of monitoring increasing sea turtle relative abundance in the Gulf of Mexico. Sci. Rep. 13, 17213. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-43651-4

Lawani A., Holmes C., Throgmorten T., and Coleman A. T. (2022). Characteristics of immature green turtles (Chelonia mydas) incidentally captured at a fishing pier in Northwest Florida. Mar. Turtle. Newsl. 165, 12–14.

Lenth R. (2023). emmeans: Estimated marginal means, aka least-squares means. R package version 1.9.0. Available online at: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=emmeans (Accessed December 12, 2024).

Lewison R. L., Freeman S. A., and Crowder L. B. (2004). Quantifying the effects of fisheries on threatened species: the impact of pelagic longlines on loggerhead and leatherback sea turtles. Ecol. Lett. 7, 221–231. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2004.00573.x

Lloret J., Biton-Porsmoguer S., Carreño A., Di Franco A., Sahyoun R., Melià P., et al. (2020). Recreational and small-scale fisheries may pose a threat to vulnerable species in coastal and offshore waters of the western Mediterranean. ICES. J. Mar. Sci. 77, 2255–2264. doi: 10.1093/icesjms/fsz071

López-Barrera E. A., Longo G. O., and Monteiro-Filho E. L. A. (2012). Incidental capture of green turtle (Chelonia mydas) in gillnets of small-scale fisheries in the Paranaguá Bay, Southern Brazil. Ocean. Coast. Manage. 60, 11–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2011.12.023

López-Castro M. C., Cuevas E., Guzmán Hernández V., Raymundo Sánchez Á., Martínez-Portugal R. C., Reyes D. J. L., et al. (2022). Trends in reproductive indicators of green and hawksbill sea turtles over a 30-year monitoring period in the Southern Gulf of Mexico and their conservation implications. Animals 12, 3280. doi: 10.3390/ani12233280

Mcgrath S., Butcher P., Broadhurst M., and Cairns. S. (2011). Reviewing hook degradation to promote ejection after ingestion by marine fish. Aust. J. Mar. Freshw. Res. 62, 1237–1247. doi: 10.1071/MF11082

National Marine Fisheries Service and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (1991). Recovery Plan for U.S. Population of Atlantic Green Turtle (Washington, D.C: National Marine Fisheries Service).

National Marine Fisheries Service and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (1992). Recovery Plan for leatherback turtles in the U.S. Caribbean, Atlantic, and Gulf of Mexico (Washington D.C: National Marine Fisheries Service). Available online at: https://repository.library.noaa.gov/view/noaa/15994.

National Marine Fisheries Service and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (1993). Recovery plan for hawksbill turtles in the U.S. Caribbean Sea, Atlantic Ocean, and Gulf of Mexico (St. Petersburg, Florida: National Marine Fisheries Service).

National Marine Fisheries Service and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (2008). Recovery Plan for the Northwest Atlantic Population of the Loggerhead Sea Turtle (Caretta caretta), Second Revision (Silver Spring, MD: National Marine Fisheries Service).

National Marine Fisheries Service Southeast Fisheries Science Center (2001). Stock assessments of loggerhead and leatherback sea turtles and an assessment of the impact of the pelagic longline fishery on the loggerhead and leatherback sea turtles of the Western North Atlantic (Miami, FL: U.S. Department of Commerce NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS- SEFSC-455), 343.

National Marine Fisheries Service, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and SEMARNAT (2011). Bi-national recovery plan for the Kemp’s ridley sea turtle (Lepidochelys kempii), Second Revision (Silver Spring, Maryland: National Marine Fisheries Service), 155 pp + appendices.

OpenAI (2024). ChatGPT [Computer software]. Available online at: https://www.openai.com/chatgpt (Accessed January 1, 2025).

Oravetz C. A. (1999). “Reducing incidental catch in fisheries,” in Research and Management Techniques for the Conservation of Sea Turtles. Eds. Eckert K. L., Bjorndal K. A., Abreu-Grobois F. A., and Donnelly M. (Consolidated Graphic Communications, Blanchard, Pennsylvania), 189–196.

Oros J., Calabuig P., and Deniz S. (2004). Digestive pathology of sea turtles stranded in the Canary Islands between 1993 and 2001. Vet. Rec. 155, 169–174. doi: 10.1136/vr.155.6.169

Parga M. L. (2012). Hooks and sea turtles: A Veterinarians Perspective. Bull. Mar. Sci. 88, 731–741. doi: 10.5343/bms.2011.1063

Peckham S. H., Maldonado-Diaz D., Tremblay Y., Ochoa R., Polovina J., Balazs G., et al. (2011). Demographic implications of alternative foraging strategies in juvenile loggerhead turtles Caretta caretta of the North Pacific Ocean. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 425, 269–280. doi: 10.3354/meps08995

Phillips K. F., Martin K. R., Stahelin G. D., Savage A. E., and Mansfield K. L. (2022). Genetic variation among sea turtle life stages and species suggests connectivity among ocean basins. Ecol. Evol. 12, e9426. doi: 10.1002/ece3.9426

Putman N. F., Hawkins J., and Gallaway B. J. (2020a). Managing fisheries in a world with more sea turtles. Proc. R. Soc B. 287, 20200220. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2020.0220

Putman N. F., Richards P. M., Dufault S. G., Scott-Dention E., McCarthy K., Beyea R. T., et al. (2023). Modeling juvenile sea turtle bycatch risk in commercial and recreational fisheries. Iscience 26, 105977. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2023.105977

Putman N. F., Seney E. E., Verley P., Shaver D. J., López-Castro M. C., Cook M., et al. (2020b). Predicted distributions and abundances of the sea turtle ‘lost years’ in the western North Atlantic Ocean. Ecography 43, 506–517. doi: 10.1111/ecog.04929

R Core Team (2022). R: A language and environment for statistical computing (Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing). Available online at: https://www.R-project.org/ (Accessed September 1, 2023).

Reimer J., Siegfried T., Roberto E., and Piacenza S. E. (2023). Influence of nearby environment on recreational bycatch of sea turtles at fishing piers in the eastern Gulf of Mexico. Endang. Species. Res. 50, 279–294. doi: 10.3354/esr01232

Rose S. A., Bates E. B., McNaughton A. N., O’Hara K. J., and Barco S. G. (2022). Characterizing sea turtle bycatch in the recreational hook and line fishery in Southeastern Virginia, USA. Chelonian. Conserv. Biol. 21, 63–73. doi: 10.2744/CCB-1476.1

Rudloe A. and Rudloe J. (2005). Site specificity and the impact of recreational fishing activity on subadult endangered Kemp’s ridley sea turtles in estuarine foraging habitats in the northeastern Gulf of Mexico. Gulf. Mex. Sci. 23, 186–191. doi: 10.18785/goms.2302.05

Scott R. L., Putman N. F., Beyea R. T., Repeta H. C., and Ainsworth C. H. (2024). Modeling transport and feeding of juvenile Kemp’s ridley sea turtles on the West Florida shelf. Ecol. Modell. 490, 110659. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2024.110659

Seminoff J. A., Allen C. D., Balazs G. H., Dutton P. H., Eguchi T., Haas H. L., et al. (2015). Status review of the green turtle (Chelonia mydas) under the U.S. Endangered Species Act (La Jolla, California: NOAA Technical Memorandum, NOAANMFS-SWFSC-539), 571pp.

Seney E. E. (2008). Population dynamics and movements of the Kemp’s ridley sea turtle, Lepidochelys kempii, in the northwestern Gulf of Mexico (College Station (Texas: Texas A&M University).

Seney E. E. (2016). Diet of Kemp’s ridley sea turtles incidentally caught on recreational fishing gear in the northwestern Gulf of Mexico. Chelonian. Conserv. Biol. 15, 132–137. doi: 10.2744/CCB-1191.1

Seney E. E. and Musick J. A. (2007). Historical diet analysis of loggerhead sea turtles (Caretta caretta) in Virginia (Copeia) 2, 478–489. doi: 10.1643/0045-8511(2007)7[478:HDAOLS]2.0.CO;2

Shamblin B. M., Hart K. M., Lamont M. M., Shaver D. J., Dutton P. H., LaCasella E. L., et al. (2023). United States Gulf of Mexico waters provide important nursery habitat for Mexico’s green turtle nesting populations. Front. Mar. Sci. 9. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2022.1035834

Shaver D. J. (1991). Feeding ecology of wild and head-started Kemp’s ridley sea turtles in South Texas waters. J. Herpetol. 25, 327–334. doi: 10.2307/1564592

Siegfried T., Noren C., Reimer J., Ware M., Fuentes M. M., and Piacenza S. E. (2021). Insights into sea turtle population composition obtained with stereo-video cameras in situ across nearshore habitats in the northeastern Gulf of Mexico. Front. Mar. Sci. 8. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2021.746500

Tagliolatto A. B., Goldberg D. W., Godfrey M. H., and Monteiro-Neto C. (2020). Spatio-temporal distribution of sea turtle strandings and factors contributing to their mortality in south-eastern Brazil. Aquat. Conserv.: Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 30, 331–350. doi: 10.1002/aqc.3244

Tomas J., Aznar F. J., and Raga. J. A. (2001). Feeding ecology of the loggerhead turtle Caretta caretta in the western Mediterranean. J. Zool. 255, 525–532. doi: 10.1017/S0952836901001613

Valente A. L. S., Parga M. L., Velarde R., Marco I., Lavin S., Alegre F., et al. (2007). Fishhook lesions in loggerhead sea turtles. J. Wildl. Dis. 43, 737–741. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-43.4.737

van der Zee J. P., Christianen M. J. A., Nava M., Velez-Zuazo X., Hao W, Bérubé M., et al. (2019). Population recovery changes population composition at a major southern Caribbean juvenile developmental habitat for the green turtle, Chelonia mydas. Sci. Rep. 9, 14392. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-50753-5

Wallace B. P., Kot C. Y., DiMatteo A. D., Lee T., Crowder L. B., and Lewison R. L. (2013). Impacts of fisheries bycatch on marine turtle populations worldwide: toward conservation and research priorities. Ecosphere 4, 1–49. doi: 10.1890/ES12-00388.1

Watson J. W., Epperly S. P., Shah A. K., and Foster D. G. (2005). Fishing methods to reduce sea turtle mortality associated with pelagic longlines. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 62, 965–981. doi: 10.1139/f05-004

Werneck M. R., Giffoni B. B., Consulim C. E. N., and Gallo G. G. (2008). A case report of hook ingestion and expelling by a green turtle. Mar. Turtle. Newsl. 120, 11–12.

Wickham H., Averick M., Bryan J., Chang W., McGowan L. D., François R., et al. (2019). Welcome to the tidyverse. J. Open Source Softw. 4, 1686. doi: 10.21105/joss.01686

Williard A., Parga M., Sagarminaga R., and Swimmer Y. (2015). Physiological ramifications for loggerhead turtles captured in pelagic longlines. Biol. Lett. 11, 20150607. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2015.0607

Wilson S. M., Raby G. D., Burnett N. J., Hinch S. G., and Cooke S. J. (2014). Looking beyond the mortality of bycatch: Sublethal effects of incidental capture on marine animals. Biol. Conserv. 171, 61–72. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2014.01.020

Keywords: sea turtle, recreational fisheries, bycatch, incidental capture, Florida

Citation: Brannum RJ, Minch K, Wideroff M, Koperski ME, Shea CP, Foley AM and Trindell RN (2025) Pier pressure: 23 years of incidental sea turtle captures at recreational fishing piers along Florida’s Gulf coastline. Front. Mar. Sci. 12:1686607. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2025.1686607

Received: 15 August 2025; Accepted: 24 November 2025; Revised: 11 November 2025;

Published: 10 December 2025.

Edited by:

André Sucena Afonso, University of Coimbra, PortugalReviewed by:

Nathan Freeman Putman, LGL, United StatesArmando Jose Barsante Santos, Florida State University, United States

Copyright © 2025 Brannum, Minch, Wideroff, Koperski, Shea, Foley and Trindell. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Robby J. Brannum, cm9iYnkuYnJhbm51bUBteWZ3Yy5jb20=

†ORCID: Meghan E. Koperski, orcid.org/0009-0008-9463-0906

Robby J. Brannum

Robby J. Brannum Karrie Minch2

Karrie Minch2 Colin P. Shea

Colin P. Shea Allen M. Foley

Allen M. Foley Robbin N. Trindell

Robbin N. Trindell