- 1Laboratory of Bacterial Pathogenesis, Department of Microbiology and Immunology, Institutes of Medical Sciences, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, Shanghai, China

- 2School of Biomedical Sciences, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China

Lipoprotein NlpI of Escherichia coli is involved in the cell division, virulence, and bacterial interaction with eukaryotic host cells. To elucidate the functional mechanism of NlpI, we examined how NlpI affects cell division and found that induction of NlpI inhibits nucleoid division and halts cell growth. Consistent with these results, the cell division protein FtsZ failed to localize at the septum but diffused in the cytosol. Elevation of NlpI expression enhanced the transcription and the outer membrane localization of the heat shock protein IbpA and IbpB. Deletion of either ibpA or ibpB abolished the effects of NlpI induction, which could be restored by complementation. The C-terminus of NlpI is critical for the enhancement in IbpA and IbpB production, and the N-terminus of NlpI is required for the outer membrane localization of NlpI, IbpA, and IbpB. Furthermore, NlpI physically interacts with IbpB. These results indicate that over-expression of NlpI can interrupt the nucleoids division and the assembly of FtsZ at the septum, mediated by IbpA/IbpB, suggesting a role of the NlpI/IbpA/IbpB complex in the cell division.

Introduction

Bacterial lipoproteins are a group of membrane proteins and play important roles in bacterial physiology and virulence, including nutrient uptake, cell division, antibiotic resistance, cell wall metabolism, transmembrane signal transduction, and adhesion to eukaryotic host cells (Crago and Koronakis, 1998; Egan et al., 2014; Nesta et al., 2014; Zuckert, 2014). Lipoproteins are synthesized as precursor forms harboring an N-terminal signal peptide. In both Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria, to form mature lipoprotein, the precursors of lipoproteins are covalently modified by an amide-linked acyl group at the N-terminal cysteine residue and subsequently removed of signal peptide. More than 90 lipoproteins have been annotated in the Escherichia coli genome and some of them have been characterized (Ichihara et al., 1981; Yu et al., 1986; Ehlert et al., 1995).

NlpI is a lipoprotein broadly distributed in Gram-negative bacteria and conserved in E. coli strains (Ohara et al., 1999). Premature NlpI is a 34-kDa polypeptide containing 294 amino acid residues including an N-terminal signal sequence of 18 amino acid residues. NlpI is located in the outer membrane (OM) and may be processed by Prc protease (Tadokoro et al., 2004; Teng et al., 2010). Moreover, NlpI is a typical Tetratricopeptide repeat (TPR) protein and contains five TPR motifs, which usually mediate intermolecular protein–protein interactions (Das et al., 1998).

NlpI has multiple functions. NlpI contributes to the interaction of E. coli with intestine epithelial cells and human brain microvascular endothelial cells (Barnich et al., 2004; Teng et al., 2010). NlpI facilitates the deposition of the complement regulator C4bp to the bacterial surface to evade innate immune system (Tseng et al., 2012). Moreover, the over-production of nlpI inhibits the release of bacterial extracellular DNA (eDNA) (Sanchez-Torres et al., 2010). The homolog of NlpI inhibits biofilm formation and contributes to cell cold acclimatization in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (Rouf et al., 2011a,b).

A previous study suggested that NlpI plays a role in the bacterial cell division (Ohara et al., 1999). Insertion inactivation of E. coli nlpI results in abnormal cell division and formation of filaments at elevated temperature. Over-expression of nlpI in E. coli inhibits cell growth and results in the formation of ellipsoids. However, the underlying mechanism of how NlpI regulates cell division remains unknown. The first step in bacterial cytokinesis is the assembly of a stable but dynamic Z ring at the site of division. FtsZ is a tubulin-like filament-forming GTPase and assembles into the Z ring that determines the division plane (Li et al., 2013). The initial placement of FtsZ polymerization site is tightly regulated by multiple mechanisms (Wu and Errington, 2012) as are the subsequent polymer reshaping and force generation that separate the two daughter cells from each other. The interference with FtsZ polymerization disrupts the cell division (Bi and Lutkenhaus, 1993; Mukherjee et al., 1998). It is unclear whether NlpI is associated with FtsZ.

This study aims at understanding the role of NlpI in E. coli cell division. We found that the elevation of NlpI protein level not only led to severe inhibition of bacterial growth and the bacterial morphology change, but also inhibited nucleoid division and disturbed FtsZ localization in the septum in E. coli. Furthermore, we identified two small heat shock proteins (sHsps), IbpA and IbpB involving in the NlpI-participated cell division regulation and IbpB interacted with NlpI. Our data suggested that NlpI, IbpA, and IbpB form a complex, which most likely plays a role in nucleoid separation and FtsZ localization in cell division.

Materials and Methods

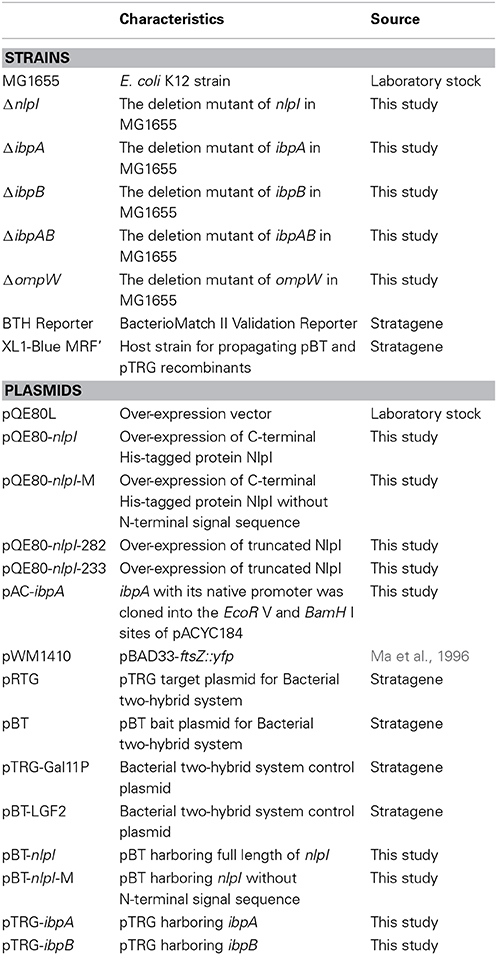

Bacterial Strains and Plasmids

The bacterial strains used in this study are derivatives of E. coli K12 strain MG1655 or MC1000. All E. coli strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. All primers used in this study are listed in Table S1.

The deletion mutants in E. coli were constructed as previously described (Datsenko and Wanner, 2000). The ΔibpA isogenic mutant strain was replacement of ibpA by the chloramphenicol resistance cassette in the E. coli strain MG1655. The ΔibpB, ΔibpAB (deletion of ibpA and ibpB), and ΔompW were constructed using the same method. ibpA with its native promoter was inserted into pACYC184 vector, and the resultant plasmid pAC-ibpA was used for complementation assay. His-tagged NlpI or NlpI-M (mature NlpI without signal peptide) was expressed from pQE80-nlpI or pQE80-nlpI-M, respectively.

The Growth Characteristics of Various E. coli Strains

E. coli strain MG1655 and its derivative mutants were transformed individually with the recombinant plasmids pQE80-nlpI by calcium chloride transformation method. Overnight cultures of the strains were subcultured in 40 ml LB broth (1:100) and incubated at 37°C with agitation until the OD600 was 0.5 as the zero hour reading. Then the cultures were divided into two bottles. One bottle was added with 0.5 mM isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) and the other one was not. The two bottles were incubated in 37°C while shaking at 250 rpm for 5 h. OD600 was monitored every hour by biophotometer (Eppendorf).

Microscopy Monitoring of Cells and Nucleoids

Bacterial morphology was visualized by light microscopy of Gram-stained cells and scanning electron microscopy. Nucleoids were stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) and observed by an Olympus fluorescence microscope according to the previously described method (Hiraga et al., 1989).

Microscopy Monitoring of FtsZ-YFP

E. coli strain MC1000 bearing FtsZ-YFP-expressing plasmid, pWM1410, was transformed with the recombinant plasmid pQE80-nlpI, pQE80-nlpI-M, pQE80-nlpI-282 or pQE80-nlpI-233, respectively. Overnight cultures of the strains were subcultured in 40 ml LB broth (1:100), supplemented with ampicillin and chloramphenicol, and incubated at 37°C with agitation until the OD600 was 0.5. Then the cultures were divided into two bottles. One bottle was added with 0.5 mM IPTG and 10mM L-arabinose (Ara), the other one was added with 10 mM Ara. The two bottles were incubated in 37°C while shaking at 250 rpm for 4 h. Bacteria were stained with DAPI. Nucleoids and FtsZ-YFP were observed by fluorescence microscope (Olympus).

Cell Fractionation

Cell fractionation was carried out as described previously (Wai et al., 2003; Zhou et al., 2012). Briefly, the bacterial cells were harvested by centrifugation and washed with 10 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.0) followed by sonication to disrupt the cells. The cell debris and unbroken cells were removed by centrifugation at 5000 g for 10 min at 4°C, and the supernatant was fractionated into the membrane and cytoplasmic fractions by centrifugation at 10,000 g for 30 min at 4°C. The supernatant was cytoplasmic fraction (CP). The sediment was treated with N-lauryl sarcosine at a final concentration of 2% at room temperature for 30 min and then centrifuged at 15,000 g for 30 min at 4°C. The resulting sediment was OM fraction, and the supernatant was inner membrane fraction. Samples were analyzed by 15% SDS-PAGE. The discrepant bands on the 15% SDS-PAGE were applied to mass spectrometry (MS) analysis by using ABI 4700 TOF/TOF.

RNA Manipulation and Quantitative Real-Time RT-PCR

Total bacterial RNA was extracted using RiboPure-Bacteria kit (Ambion) and treated with DNase I to remove genomic DNA according to the manufacturer's instructions. RNA concentrations were measured using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo). Reverse transcription (RT) was implemented using the SuperScript III First-Stand Synthesis System (Invitrogen). The quantification of the target gene mRNA level was performed by the quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) with a SYBR Premix Ex Taq II (TaKaRa) and the ABI PRISM 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR System according to the manufacturer's instructions. The primers of nlpI, ibpA, ibpB, ompW or 16S rRNA (internal control) were listed in Table S1.

Microarray Analysis

Microarray was carried out as described previously (Yao et al., 2005, 2006). A total of 7644 70-mer oligonucleotides from E. coli were spotted in replicate onto aminosilane slides. The oligonucleotides that are targeting backbone genes in E. coli genomes were derived from an oligonucleotide set (http://pfgrc.jcvi.org/index.php/microarray/array_description/escherichia_coli/version1.html). It is a pan E. coli genome chip and covers all the ORFs in E. coli strain MG1655. E. coli strain MG1655 harboring plasmids pQE80-nlpI or pQE80L were grown in LB medium at 37°C with agitation until the OD600 was 0.5. Then IPTG was added at a final concentration of 0.5 mM followed by incubation with shaking for 2 h at 250 rpm. Total RNA was immediately isolated by using RiboPure-Bacteria kit (Ambion) and treated with DNase I. Ten micrograms of total RNA was denatured in the presence of 600 ng of random hexamers and 2 μl of 10X dNTPs [dATP, dCTP, dGTP, and aminoallyl-dUTP (100 mM each)] (total, 20 μl) for 5 min at 65°C and was snap-cooled on the ice. Then, cDNA synthesis was implemented by the SuperScript III First-Stand Synthesis System for RT-PCR kit (Invitrogen). Residual RNA was hydrolyzed by alkaline, and bacterial cDNA was purified by QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen) and labeled by use of ARES Alexa Fluor dye at 488 or 594 nm (Molecular Probes, Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The labeled cDNA was purified by Centri-Spin 20 Columns (Princeton Separations). The microarray slides were prehybridized. Equal amounts of two oppositely labeled cDNA were mixed together with equal volume of SlideHybe#3 (Ambion) and loaded onto the slide. The slide was incubated for 16 to 18 h at 42°C and washed at 55°C by 2X SSC/0.1% SDS, 10 min in 0.1X SSC/0.1% SDS at room temperature twice, 5 min in 0.1X SSC at room temperature twice and 2 min in 0.05X SSC. After drying, the slide was scanned at 594 and 488 nm with a GenePix™ 4200A Scanner (Molecular Devices). Three independent experiments were performed by reversing dyes. Image processing and data extraction were accomplished by using GenePix Pro 6.0.1.27 (Axon Instruments). Microarrays were analyzed using R with “limma” package. After loading the microarray data into R, several steps were done following the limma user guides, including: Background Correction (method = “normexp,” offset = 50); Within-Array Normalization (method = “loess”); Between-Array Normalization (method = “quantile”). Two kinds of plots were used to assess the normalization procedures: MA-plot (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/MA_plot); Individual-channel Densities.

Western Blot Analysis

Protein samples were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membranes. Membranes were blocked by 5% non-fat milk in Tris Buffered Saline (TBS), with 0.1% Tween-20 added. The rabbit anti-sera against NlpI (1:3000) or anti-IbpA (1:3000) or anti-Crp (1:4000), the mouse anti-sera against-His (1:4000), and the goat horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-rabbit or anti-mouse IgG antibodies (1: 4000) were used as the primary or secondary antibodies to detect the target proteins. The rabbit anti-sera against NlpI is a gift from Dr. Kwang Sik Kim at Johns Hopkins University. The rabbit anti-IbpA and anti-Crp sera were customized by Beijing ComWin Biotech. The mouse anti-sera against-His was purchased from Tiangen. HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit or anti-mouse IgG antibodies were purchased from Beijing ComWin Biotech. The antibody of RNAP (RNA polymerase) was purchased from Santa Cruz and used according to manufacturer's manual. The blots were developed with Super Signal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate (Thermo).

Co-Immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) Assay

The interactions between NlpI and IbpA or IbpB were analyzed by Co-IP according to the Pierce Crosslink Immunoprecipitation Kit (Thermo) with some modifications. E. coli strain MG1655 harboring pQE80-nlpI-M were induced with 500 μM IPTG for 4 h and then harvested and resuspended in 1 ml of ice cold buffer (25 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% NP-40, 5% glycerol, pH 7.4). After sonication, cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 10,000 g for 30 min at 4°C. Co-IP were performed by binding of 10 μg of anti-HisTag antibody to 20 μl protein A/G plus agarose for 1 h, crosslinking, and then incubating with 150 μg of cell extracts in 300 μl of IP Lysis/Wash buffer for 2 h at 4°C with shaking. The beads were washed with the IP Lysis/Wash buffer. Immune complexes were eluted and analyzed by Western blot using anti-IbpA, anti-NlpI or anti-HisTag antibody.

Bacterial Two-Hybrid Assay

The protein-protein interaction between NlpI and IbpA or IbpB was examined by BacterioMatch II Two-Hybrid System (Stratagene) according to the previous description (Du et al., 2012). The nlpI-M and nlpI were cloned into the pBT individually. The ibpA and ibpB genes were cloned into the pTRG individually. The reporter strain was co-transformed with the recombinant plasmids pBT-nlpI-M and pTRG-ibpA or pTRG-ibpB and streaked onto the dual selective screening medium (DSSM) containing 5 mM 3-amino-1,2,4-triazole (3-AT), 12.5 mM streptomycin, 12.5 mM tetracycline, 25 mM chloramphenicol and 50 mg/ml kanamycin. A cotransformant containing pBT-LGF2 and pTRG-Gal11P was used as a positive control for expected growth on DSSM. A cotransformant containing pBT and pTRG was used as a negative control. Bacterial two-hybrid assay between the recombinant plasmids pBT-nlpI and pTRG-ibpA or pTRG-ibpB were carried out similarly.

Statistical Analysis

qRT-PCR data are shown as means ± standard deviations. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 5. Paired t-tests were used to determine P-values. With regard to the microarray data analysis, after analyzed by R package, genes with the expression fold change greater than 2 or less than 0.5 and P-value < 0.01 were considered as differential expression.

Results

Inhibition of E. coli Growth by Induction of nlpI

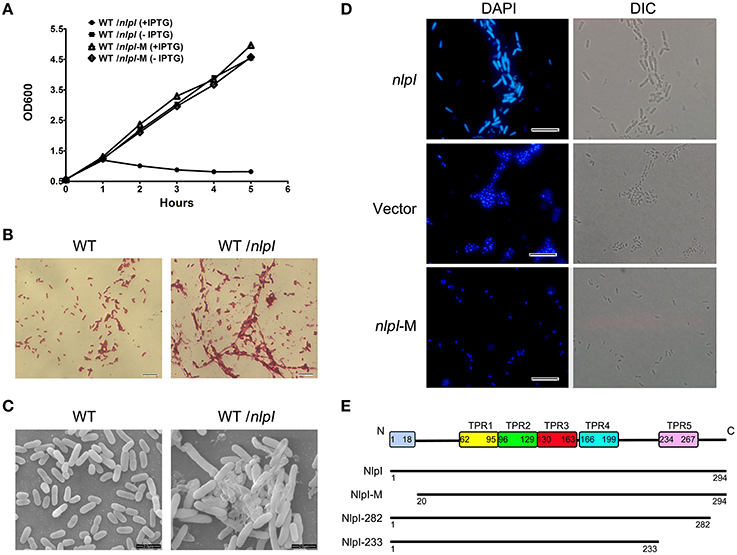

The previous study found that the over-expression of nlpI affects cell growth and cellular morphology in E. coli strain MO101 (Ohara et al., 1999). It promoted us to test whether this phenotype is unique in a certain E. coli strain or not. Therefore, E. coli strain MG1655 harboring plasmid pQE80-nlpI was tested. When the bacteria were induced with 0.5 mM IPTG at 37°C, the cell growth was inhibited severely (Figure 1A). Light microscopy showed the increase of width and length of cell and the aggregation of bacterial cells after induction (Figure 1B), and scanning electron microscopy illustrated the appearance of swollen prolate ellipsoids and cell envelope invagination and damage (Figure 1C). Since the bacterial filamentation was observed with over-expression of nlpI, we want to check the nucleoids division in these cells. DAPI staining showed that the bacterial nucleoids were anomalous after the induction of nlpI compared with control cells (Figure 1D). We suspect that over-expression of nlpI affected the cell division by influencing nucleoids division. Another E. coli strain DH5α was applied to the above assays and showed similar phenotypes (data not shown). This means that the phenotypes we observed are not strain specific.

Figure 1. The elevation of nlpI in E. coli inhibited the host cell growth. (A) The growth curves of the wild type (WT) strain MG1655 harboring the plasmid pQE80-nlpI or pQE80-nlpI-M in the presence or absence of inducer. Results shown are representative of three independent experiments. (B) The cellular morphology of Gram-stained bacteria. E. coli strain MG1655 harboring plasmid pQE80-nlpI was incubated in LB broth at 37°C with shaking until OD600 reached 0.5. Then the bacteria were induced by adding IPTG to a final concentration of 0.5 mM for 4 h. The cells were subsequently stained with Gram stain and observed by light microscope. Magnification, X1000. (C) Scanning electron microscopy examined the cellular morphology change and aggregation. Magnification, X10,000. (D) Bacteria were stained with DAPI and nucleoids were observed by fluorescence microscopy. Magnification, X1000. Scale bar, 10 μm. (E) Schematic presentation of NlpI and its three variants. The full length NlpI contains 294 amino acids including an N-terminal signal sequence and five TPR motifs. NlpI-M represents a mature NlpI protein without N-terminal signal sequence. NlpI-282 and NlpI-233 are truncated NlpI lacking the C-terminal 12 residues and the fifth TPR, respectively.

During export of OM lipoprotein across the cytoplasmic membrane, the lipoprotein signal peptide is cleaved by signal peptidase, which is critical for the function of lipoprotein (Zuckert, 2014). In order to investigate the role of NlpI signal peptide in bacterial growth and division, we constructed pQE80-nlpI-M that contained the sequence in accordance with the mature polypeptide (residues 20–294, lacking the signal sequence and Cys19) (Figure 1E). With the IPTG induction, the growth curve showed the bacterial growth rate was comparable to that of control strain without induction (Figure 1A). DAPI staining showed that the bacterial nucleoids were normal (Figure 1D). This highly suggests that the signal peptide sequence is required for the phenotypes caused by NlpI over-expression.

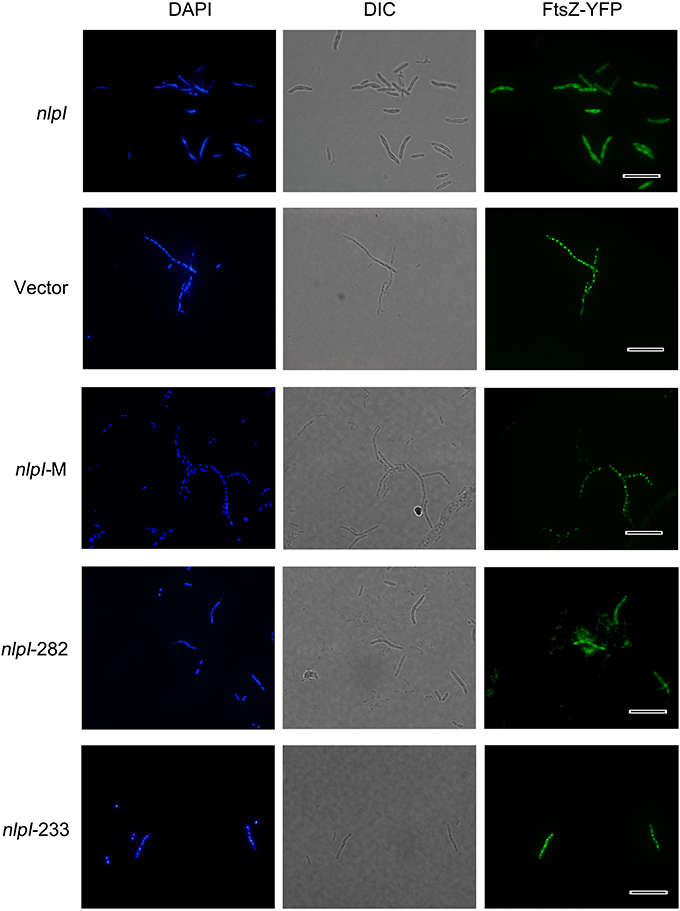

It has been shown that the C-terminus of NlpI is critical to correct the thermosensitivity of the nlpI mutant (Tadokoro et al., 2004). Moreover, the amino acid sequence showed that NlpI contains five TPR motifs (Wilson et al., 2005). To determine the role of NlpI C-terminus, we constructed two plasmids, pQE80-nlpI-282 (lacking the C-terminal 12 residues) and pQE80-nlpI-233 (lacking the C-terminal 61 residues including the fifth TPR) (Figure 1E). These two plasmids were introduced individually into E. coli strain MG1655 followed by induction with IPTG. We found that the over-expression of nlpI-282 severely inhibited the bacterial growth, but nlpI-233 failed (data not shown). DAPI staining showed the bacterial nucleoids in the over-expression of nlpI-282 cell were anomalous, which was similar to that of the full length nlpI (Figure 2), while the nucleoids were normally divided in the nlpI-233 over expression cells (Supplementary Figure S1). The above experiments suggested that NlpI was involved in the bacterial division in E. coli, and both N-terminal and C-terminal sequences were critical to the role of NlpI in the cell division.

Figure 2. Elevation of nlpI in E. coli disturbed FtsZ localization. Plasmids pQE80-nlpI, pQE80-nlpI-M, pQE80-nlpI-282 and pQE80-nlpI-233 were transformed individually into E. coli strain MC1000 carrying ftsZ-yfp fusion plasmid pWM1410, the resultant strains were induced with 0.5 mM IPTG and 10 mM Ara for 4 h. Bacteria were stained with DAPI. Nucleoids and FtsZ-YFPs were observed by fluorescence microscope. Magnification, X1000. Scale bar, 10 μm.

Elevation of nlpI Protein Level Disturbed FtsZ Localization

Bacterial cell division requires accurate localization of the cytoskeletal protein FtsZ at the nascent division site and assembly into Z-ring (Bi and Lutkenhaus, 1991). Since over-expression of nlpI inhibited nucleoids division in E. coli, we speculate that the increase of NlpI protein level perhaps influences FtsZ localization. We induced nlpI and ftsZ-yfp with IPTG and arabinose, respectively in E. coli strain MC1000, and found that the nucleoids were anomalous and FtsZ-YFPs were diffusive in the cytoplasm in nlpI over-expression cells. Induction of nlpI-282 and ftsZ-yfp caused the same change of the nucleoids and FtsZ localization as that of the full length of nlpI (Figure 2). However, both nucleoid division and FtsZ localization were normal after induction of nlpI-M or nlpI-233 (Figure 2). These results indicated that increase of NlpI inhibited nucleoid division and interfered with FtsZ localization, and both N-terminus and C-terminus contributed to this process.

The Transcriptome with Elevation of nlpI Protein Level

The above results suggest that NlpI is involved in the nucleoid separation and FtsZ localization. Since we failed to detect the interaction of NlpI and FtsZ in Co-IP assay (data not shown), we performed microarray analyses to identify other factors that may participate in this process. The total RNA from E. coli strain MG1655 harboring plasmid pQE80-nlpI or pQE80L induced with IPTG were isolated followed by reverse transcription, fluorescent labeling, hybridization, microarray scanning, and data were analyzed as previous description (Yao et al., 2005, 2006).

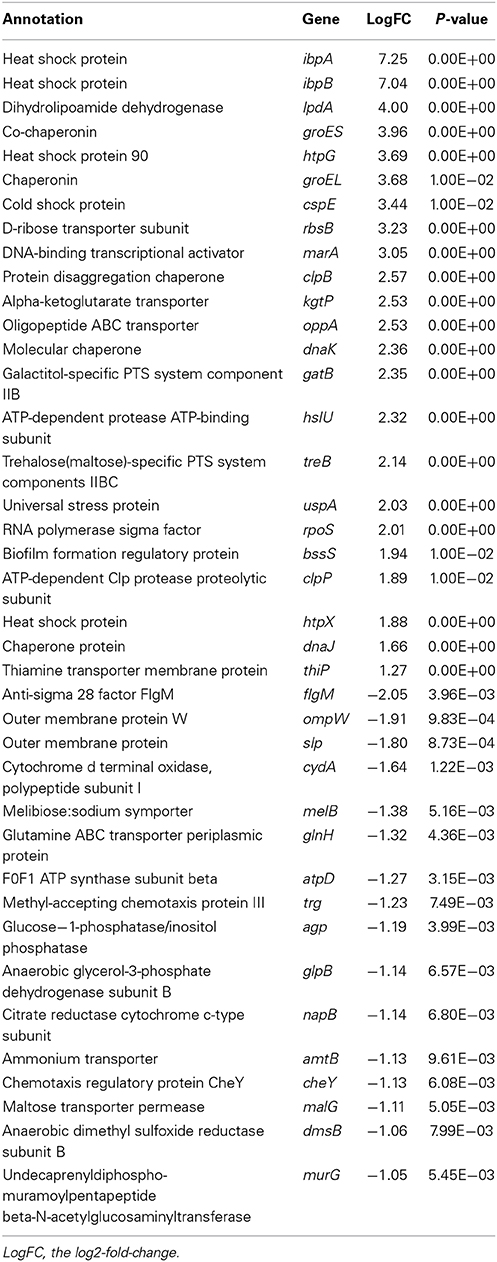

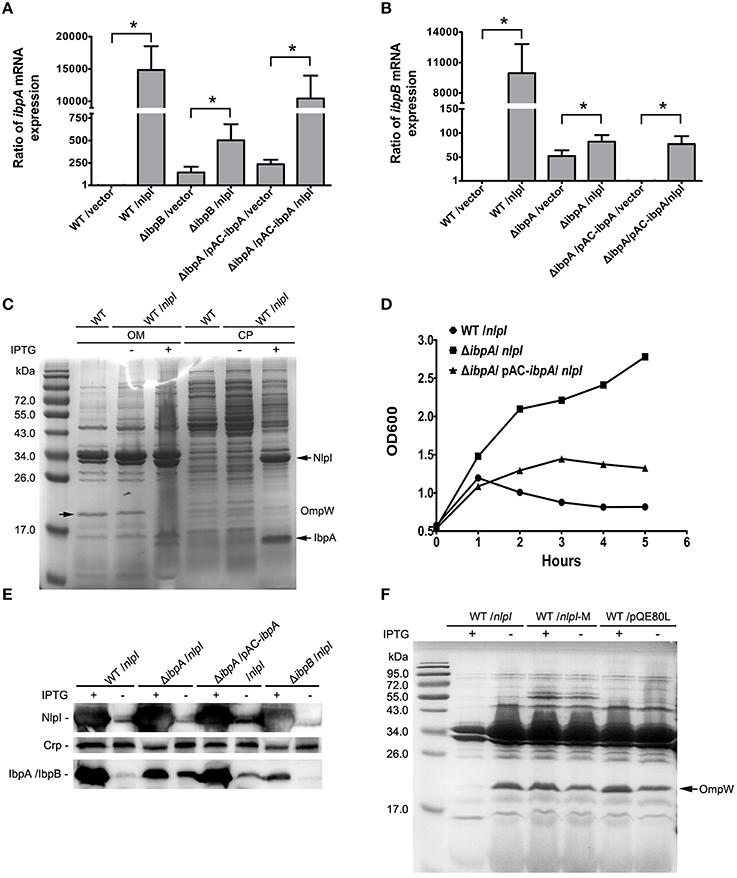

A total of 142 genes (68 up-regulated and 74 down-regulated genes) were found to be differentially expressed (Supplementary Tables S2 and S3). Some up-regulated and down-regulated genes were listed in Table 2. We did not find the change of transcriptional level of ftsZ, but we found that the transcriptional level of genes encoding heat shock proteins and chaperones, such as ibpA, ibpB, groES, groEL, htpG, clpB, dnaK, were significantly increased under NlpI overexpression. The expression of genes encoding outer membrane proteins, such as ompW and slp was significantly decreased. Small heat shock proteins lbpA and lbpB (inclusion body-associated protein) protect heat-denatured proteins from irreversible aggregation (Kuczynska-Wisnik et al., 2004). The heat shock proteins and chaperones including GroEL–GroES, DnaK, and ClpB are involved in preventing aggregation of heat-denatured proteins (Mogk et al., 2002; Sorensen and Mortensen, 2005). We suspect that the significantly up-regulated expression of above genes may be a concomitant event of the elevation of NlpI protein level and play an important role in the NlpI-participated cell division. Quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) showed that the level of ibpA mRNA was increased by 14,839.7 ± 3672.3 fold (means ± standard deviations), and that the levels of ibpB mRNA was obviously increased by 9947.3 ± 2867.9 fold in the NlpI over-expression cells (Figures 3A,B), and the transcriptional level of ompW was decreased dramatically (Supplementary Figure S2A). These findings confirmed the result of microarray (Table 2), and illustrated that the transcription of ibpA and ibpB was activated by over-expression of nlpI.

Figure 3. IbpA and IbpB are required for the NlpI-participated cell division. (A) The levels of ibpA mRNA were significantly increased with induction of nlpI in wild type strain or complementation strain. The level of ibpA mRNA in wild type strain with vector was set at one. The levels of ibpA mRNA in MG1655/pQE80-nlpI and ΔibpB/pQE80-nlpI were increased 14,839.7 ± 3672.3 and 502.2 ± 178.8 fold, respectively, compared with control. The level of ibpA mRNA in ΔibpA/pAC-ibpA/pQE80-nlpI was increased by 10,437.3 ± 3536.5 fold. The error bars indicated the SD representing the means from three independent experiments. (B) The levels of ibpB mRNA were the remarkably increased with over-expression of nlpI in wild type strain. The level of ibpB mRNA of wild type strain with empty vector was set at 1. The levels of ibpB mRNA of wild type strain and ΔibpA with inducer were increased by 9947.3 ± 2867.9 and 82.2 ± 13.6 fold, respectively. The level of ibpB mRNA in ΔibpA/pAC-ibpA was increased by 77.2 ± 16.3 fold. (C) The induction of nlpI caused the dramatic change of protein profiles of CP and OM of the host cells. Mass spectrometry identified two significantly discrepant bands, IbpA and OmpW. (D) The growth curves of wild type strain, ΔibpA and the complementation strain of ΔibpA with over-expression of nlpI were determined. The growth of wild type strain and the complementation strain of ΔibpA were inhibited. (E) Western blot analysis of the protein levels of NlpI or IbpA/IbpB in CP of the host cells, using polyclonal antibodies anti-NlpI, anti-Crp and anti-IbpA. Crp is a cytoplasmic protein marker. (F) The OM protein profiling of MG1655/pQE80-nlpI, MG1655/pQE80-nlpI-M and MG1655/pQE80L with/without inducer. *P < 0.05.

ibpA and ibpB are Required for the nlpI-Participated Cell Division

Since the over expression of nlpI cause the expression change of genes, such as ibpA, ibpB and ompW, we speculate that the protein profiling in the nlpI-induced cells differs from that of control cells. The bacterial cells were separated into two fractions: CP and OM. SDS-PAGE analysis showed that the over-expression of nlpI caused the dramatic changes of the proteins profiling in CP and OM of the host cells compared with those of the control cells (Figure 3C). The two significantly discrepant bands on the SDS-PAGE were applied to MS analysis. One band with increased amount was identified as the heat shock protein IbpA, while the other decreased band was outer membrane protein OmpW (Supplementary Table S4). These findings confirmed the result of microarray and qRT-PCR, and indicated that the elevation of NlpI protein level affected bacterial transcriptome and proteome.

Since the expression of ibpA and ibpB are significantly elevated in NlpI over expression cells, we sought to unveil their contribution in NlpI-participated cell division. The ibpA and ibpB form an operon, and are regulated by the σ32 protein, which is encoded by rpoH. The open reading frames are separated by 111 bp. A σ54-dependent promoter locates upstream of ibpB (Allen et al., 1992; Kuczynska-Wisnik et al., 2001). IbpA and IbpB appear in aggregated protein fractions after heat shock (Laskowska et al., 1996). To test whether IbpA and IbpB are involved in the NlpI-participated cell division, we constructed the deletion mutants of ibpA, ibpB, and ibpAB (ibpA and ibpB) in E. coli, and induced nlpI in these mutants. Surprisingly, the growth curves showed that the elevation of NlpI did not inhibit cell growth of these three deletion mutants (Figure 3D, Supplementary Figure S2B). After complementation of a copy of ibpA with its native promoter into the deletion mutant of ibpA, we found that over-expression of nlpI could inhibit the cell growth (Figure 3D). qRT-PCR showed that the level of ibpA mRNA in the complementation strain was restored to the level of the wild type strain (Figure 3A). The inhibition of cell growth by the over-expression of nlpI was abolished when ibpB or ibpAB was deleted (Supplementary Figure S2B). Interestingly, qRT-PCR results showed that the level of ibpA mRNA in ΔibpB was increased by 502.2 ± 178.8 fold after the nlpI induction, but was significantly lower than in MG1655 or the complementation strains of ΔibpA (Figure 3A, Supplementary Figure S2C). Likewise, we detected that the level of ibpB mRNA in ΔibpA was increased by 82.2 ± 13.6 fold after the nlpI over-expression, which was strikingly lower than that of the wild type strain with IPTG induction (Figure 3B). These results indicated that both IbpA and IbpB were required for the NlpI-participated cell division, and IbpA promoted the transcription level of ibpB in the over-expression of nlpI cells, and vice versa.

qRT-PCR showed that the transcriptional level of ibpB was increased by 52.4 ± 11.9 fold in ΔibpA cells compared with wild type strain, which could be restored by trans-complementation (Figure 3B). We prepared the polyclonal antibody of IbpA and NlpI and tested the expression of NlpI and IbpA/IbpB in the cytoplasm by Western blot. Since IbpA and IbpB, whose molecular masses were both about 16-kDa, shared 48% identity at the amino acid level, the IbpA polyclonal antibody can recognize both IbpA and IbpB. We found the result of Western blot was consistent with that of qRT-PCR (Figure 3E). Western blot detected IbpB in ΔibpA cells and IbpA in the complementation strain of ΔibpA (Figure 3E). These results showed that IbpA inhibited transcription of ibpB in wild type strain in accord with the previous finding (Gaubig et al., 2011). The level of ibpA mRNA were increased by 144.2 ± 64.4 fold in ΔibpB cells compared with that of wild type strain (Figure 3A). This means that IbpB inhibited the transcription of ibpA.

With the elevation of NlpI, DAPI staining showed that the nucleoids divided normally in both ΔibpA and ΔibpB, but the nucleoids were anomalous in the complementation strains of ΔibpA (Supplementary Figure S2D). Furthermore, the wild type strain MG1655 with either over-expression of ibpA or ibpB, or both ibpA and ibpB, showed normal growth and nucleoids division (Supplementary Figure S2D). Therefore, these data indicated that nucleoids division defect cause by NlpI overexpression was dependent on IbpA and IbpB in E. coli, and other factor(s) may be involved in this process.

To further test whether the decrease of OmpW is related to the NlpI-participated cell division, we constructed the deletion mutant of ompW followed by the over-expression of nlpI. The growth of ΔompW was inhibited as the wild type strain when nlpI was induced (Supplementary Figure S2B). We found both protein and mRNA levels of ompW were decreased by the over-expression of nlpI in the deletion mutants of ibpA, ibpB, ibpAB and ibpA complementation strains (Supplementary Figures S2A,E). Interestingly, SDS-PAGE showed that OmpW was not decreased by increasing NlpI-M protein level (Figure 3F). These results indicated that the over-expression of full length nlpI inhibited the expression of ompW in an IbpA/B independent manner.

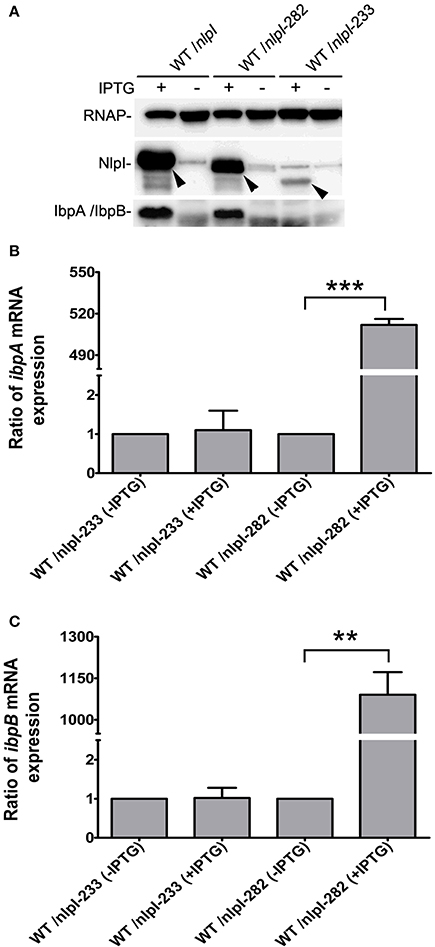

C-terminus of nlpI Involved in the Transcription of ibpA and ibpB

It has been shown that the C-terminus of NlpI is critical to its function (Tadokoro et al., 2004), we want to test the role of the C-terminal NlpI in the transcription of ibpA and ibpB by over-expressing of nlpI-282 or nlpI-233 in the wild type strain. Western blot showed that the amount of IbpA/IbpB was increased in CP fraction in the over-expression of nlpI-282 cells, but not in the over-expression of nlpI-233 cells (Figure 4A). qRT-PCR showed that the levels of ibpA and ibpB mRNA were not elevated in the over-expression of nlpI-233 cell, but increased by 511.8 ± 4.4 and 1090.7 ± 81.4 fold after the induction of nlpI-282, respectively (Figures 4B,C, Supplementary Figure S3). These results indicated that C-terminus of NlpI played an important role in the transcription of ibpA or ibpB.

Figure 4. C-terminal of NlpI involved in the transcription of ibpA and ibpB. (A) Western blot with anti-NlpI and anti-IbpA antibody detected that IbpA and IbpB were increased in CP after the induction of nlpI or nlpI-282, but not in the over-expression of nlpI-233 cells. (B, C) qRT-PCR showed that the mRNA levels of ibpA and ibpB after the induction of nlpI-282 were increased by 511.8 ± 4.4, 1090.7 ± 81.4 fold, respectively, compared with corresponding stain without IPTG. But the mRNA levels of ibpA and ibpB after the induction of nlpI-233 were 1.1 ± 0.5, 1.02 ± 0.26 fold, respectively, compared with corresponding stain without IPTG. ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01.

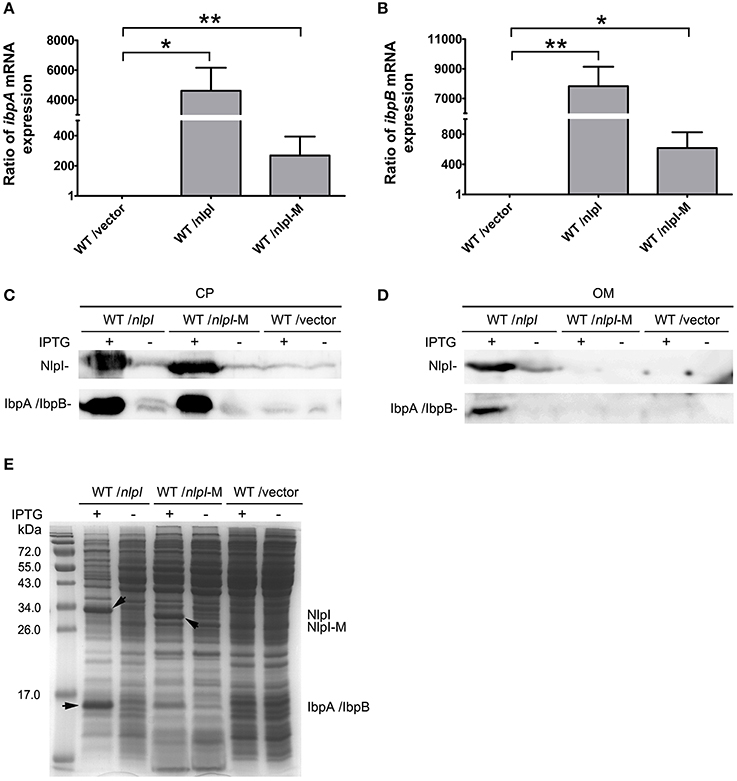

nlpI mediated IbpA and IbpB Localization to Outer Membrane

It has been shown that IbpA and IbpB are localized to OM (Laskowska et al., 1996), and our data showed that over-expression of nlpI promoted the expression of ibpA and ibpB, we speculate that the localization of IbpA and IbpB might be affected. To test this hypothesis, we over-expressed nlpI or nlpI-M in the wild type cells followed by RNA isolation and cell fractionation. qRT-PCR showed that the mRNA levels of ibpA and ibpB were increased after the over-expression of nlpI or nlpI-M (Figures 5A,B). We detected the dramatic increase of NlpI in the OM of cells with over-expression of nlpI by using His-tag antibody, but not in the cells with over-expression of nlpI-M (Figure 5D). This result showed that N-terminal signal sequence is required for NlpI localization to OM. The amount of IbpA/IbpB was increased in CP fraction after the over-expression of either nlpI or nlpI-M as expected (Figures 5C,E). However, the amount of IbpA/IbpB in OM fraction was increased only after the over-expression of nlpI, but not nlpI-M (Figure 5D). These data indicated that localization of NlpI to OM is related to the process of IbpA and IbpB localizing to OM.

Figure 5. NlpI mediated IbpA and IbpB localization to outer membrane. (A, B) qRT-PCR showed that the mRNA levels of ibpA (A) and ibpB (B) by over-expression of nlpI or nlpI-M were increased dramatically, compared with control. (C) Western blot probed with anti-NlpI and anti-IbpA antibody showed that over-expression of nlpI or nlpI-M induced IbpA and/or IbpB in CP. (D) Western blot with anti-HisTag and anti-IbpA antibody showed that NlpI and IbpA/IbpB were present in OM of MG1655/pQE80-nlpI with inducer, but did not detected NlpI and IbpA/IbpB in OM of MG1655/pQE80-nlpI-M with inducer. (E) The CP protein profiling of MG1655/pQE80-nlpI, MG1655/pQE80-nlpI-M and MG1655/pQE80L with/without inducer. **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05.

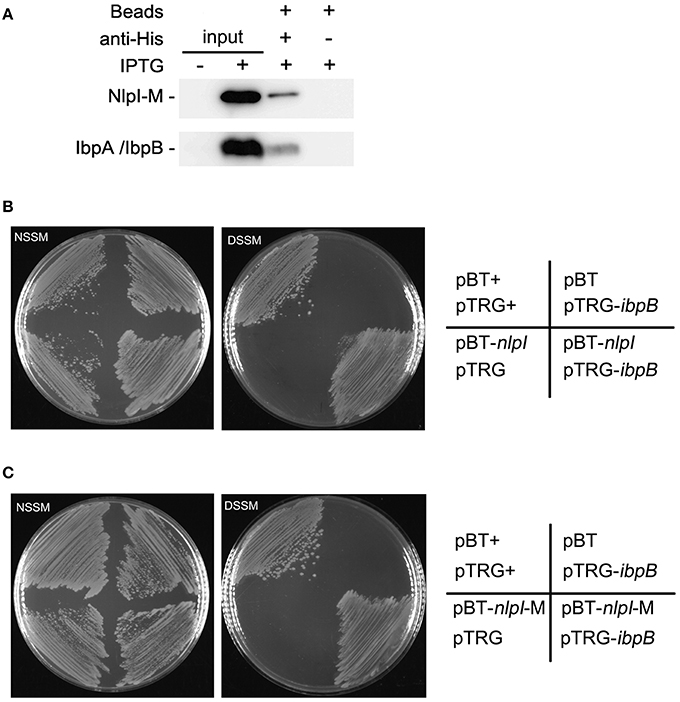

NlpI Physically Interacts with IbpB

Upregulation of IbpA and IbpB by NlpI over-expression and their co-localization to the OM suggested that these two proteins may function together with NlpI to cause growth retardation. Thus, we checked the interaction between NlpI and IbpA or IbpB. Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) assay was applied to detect the potential interaction between NlpI and IbpA/IbpB. Co-IP assay was performed by binding of His-tag antibody to protein A/G plus agarose beads and incubating with cell extracts. Immune complexes were eluted in elution buffer and analyzed by Western blot using anti-IbpA and anti-HisTag antibody (Figure 6A). The results showed that NlpI interacted with IbpA and/or IbpB. We expressed and purified NlpI-M in wild type strain, ΔibpA, ΔibpB or ΔibpAB, respectively. Western blot and MS analysis showed IbpA and IbpB were co-eluted when NlpI-M was purified in wild type strain (Supplementary Figure S4 and Table S5). Moreover, Western blot confirmed that IbpB was co-eluted in purified NlpI-M from ΔibpA. We used another method, bacterial two-hybrid assay to confirm the interaction between NlpI and IbpA/IbpB. As shown in Figures 6B,C, the co-transformants containing IbpB and NlpI or NlpI-M grew well-on DSSM. But the co-transformants containing IbpA and NlpI or NlpI-M had no obvious growth phenomenon on DSSM (data no shown). These results suggested that NlpI, IbpA, and IbpB may form a complex to mediate the cell division.

Figure 6. NlpI physically interacts with IbpB. (A) Co-IP assays for the binding of NlpI-M with protein A beads by using anti-HisTag antibody. Immune complexes in MG1655/pQE80-nlpI-M induced with IPTG were collected, and the beads were washed with IP Lysis/Wash buffer. The samples were analyzed by using anti-IbpA antibody and anti-HisTag antibody, respectively. Lane 1 and lane 2 represented input CP of the bacteria without or with IPTG for Co-IP assay. Lane 3 and lane 4 are results of Co-IP assay. (B, C) Bacterial two-hybrid assays detected the interaction between IbpB and NlpI (B) or NlpI-M (C). NSSM, Non-selective Screening Medium. DSSM, Dual Selective Screening Media (plate contained str and 5 mM 3-AT). pBT+ and pTRG+, co-transformant containing pBT-LGF2 and pTRG-Gal11P as a positive control.

Discussion

In this study, we found that the over-expression of NlpI severely inhibited the bacterial growth, influenced nucleoids division and FtsZ localization in the septum, and that nlpI-282 lacking C-terminal 12 amino acid residues sequence showed similar phenotypes. However, the over-expression of nlpI-M and nlpI-233 failed to inhibit nucleoids division and FtsZ localization. Considering the fact that we did not detect the interaction between NlpI and FtsZ, we speculated that NlpI participated in cell division by inhibiting nucleoid division and interfering with FtsZ localization in a contact independent manner.

The previous study showed that the over-expression of recombinant proteins result in heat shock-like response in E. coli (Gill et al., 2000). Under this condition, the mRNA levels of ibpA and ibpB are highly expressed (Gill et al., 2000; Jurgen et al., 2000). IbpA and IbpB are molecular chaperone proteins (Jiao et al., 2005; Strozecka et al., 2012), which are involved in resistance to heat and superoxide stresses (Kitagawa et al., 2000) and protect enzymes from inactivation by heat (Kitagawa et al., 2002). IbpA decreases the size of substrate complexes and inhibits their further processing (Ratajczak et al., 2009). IbpB, which is associated with its substrate via forming complexes with IbpA (Matuszewska et al., 2005), facilitates substrate transfer to the Hsp70/40 and the Hsp100 chaperone machinery (Ratajczak et al., 2009). In this study, the DNA microarray analysis showed that the expression of IbpA, IbpB, the Hsp70 chaperone DnaK and the Hsp100 chaperone ClpB significantly increased after the over-expression of nlpI (Table 2). Furthermore, the protein amount of IbpA and IbpB were significantly increased in CP and OM. The deletion of ibpA or ibpB and the trans-complementation of ΔibpA experiments indicated that both IbpA and IbpB were involved in the NlpI-participated cell division.

Although the increase of NlpI protein level induced the expression of ibpA and ibpB and disrupted the bacterial nucleoids division, over-expression of ibpA and/or ibpB did not show similar phenotypes. In ΔibpA, ΔibpB or ΔibpAB, nucleoids division was normal under the over-expression of nlpI, but the nucleoids were anomalous in the trans-complementation strains of ΔibpA with the over-expression of nlpI (Supplementary Figure S2D). The results indicated that inhibition nucleoids division of NlpI was dependent on the heat shock proteins IbpA and IbpB. Over-expression of nlpI-M did not inhibit the bacterial growth and nucleoid division, but induced the mRNA levels of ibpA and ibpB. Moreover, the over-expression of nlpI-M caused the increase of IbpA/IbpB in CP, but not in OM. These results demonstrated that localization of IbpA/IbpB in OM played an important role in the NlpI-participated cell division. Co-immunoprecipitation assay, proteins MS analysis (Supplementary Figure S4 and Table S5) and bacterial two-hybrid assay showed that NlpI physically interacts with IbpB. Moreover, IbpA was not found to interact with NlpI, which highly suggests that the interaction between IbpB and NlpI is specific. It has been shown that IbpA interacts with IbpB (Matuszewska et al., 2005). We speculated that localization of NlpI in OM was essential for the export of IbpB, together with IbpA to OM and required for the NlpI-participated cell division. IbpA and IbpB play important roles in protecting recombinant proteins from degradation by cytoplasmic proteases (Han et al., 2004) and optimize recombinant proteins de novo folding (de Marco et al., 2007). Here, we found that IbpAB are esstential mediators in NlpI-participated cell division process. This is different from their above mentioned chaperones roles. We propose that IbpA, IbpB and NlpI form a protein complex, which plays an essential role in the detrimental effect of NlpI over-expression because deletion of IbpA or IbpB abolished the effect. This unkown protein complex will be explored in the future to find out the role of IbpAB in the NlpI-participated cell division.

The previous studies reported that the insertion mutant of nlpI shows osmotic-sensitive growth at 42°C in E. coli (Ohara et al., 1999), and nlpI is up-regulated in response to high-pressure and the deletion mutant of nlpI is more sensitive to high-pressure than the wild type strain (Malone et al., 2006; Charoenwong et al., 2011). In this study, we found that the growth of ΔnlpI was inhibited more severely than the wild type strain at 50°C (Figure S5). Moreover, NlpI contributes to the cold acclimatization response in Salmonella Thyphimurium (Rouf et al., 2011b). We speculate that NlpI is a stress response protein and especially responds to high temperature. The up-regulation of ibpA and ibpB may be linked to the NlpI-participated stress response.

In summary, we found that over-expression of nlpI interrupts the nucleoids division and the assembly of FtsZ at the septum, and IbpA/B are required for this process, possibly by forming a NlpI/IbpA/IbpB protein complex. Other unknown factor(s) must be involved in the cell division defect caused by over-expression of nlpI. Since NlpI is a potential stress response protein, we proposed that NlpI can slow down the cell growth by inhibiting cell division to contribute the host survival when bacteria encounter heat shock stress.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The Review Editor Ching-Hao Teng declares that, despite having collaborated with author Yufeng Yao, the review process was handled objectively and no conflict of interest exists. The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully thank Dr. Baoli Zhu and Dr. Yuanlong Pan at Institute of Microbiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences for the assistance in the microarray data analysis and Dr. Benfang Lei at Montana State University for helpful discussions and critical comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Number. 30870100, Number. 31270173), the State Key Development Programs for Basic Research of China (973 Program No. 2009CB522600 and 2015CB554203), and the Program for Professor of Special Appointment (Eastern Scholar) at Shanghai Institutions of Higher Learning.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://www.frontiersin.org/journal/10.3389/fmicb.2015.00051/abstract

References

Allen, S. P., Polazzi, J. O., Gierse, J. K., and Easton, A. M. (1992). Two novel heat shock genes encoding proteins produced in response to heterologous protein expression in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 174, 6938–6947.

Barnich, N., Bringer, M. A., Claret, L., and Darfeuille-Michaud, A. (2004). Involvement of lipoprotein NlpI in the virulence of adherent invasive Escherichia coli strain LF82 isolated from a patient with Crohn's disease. Infect. Immun. 72, 2484–2493. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.5.2484-2493.2004

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Bi, E. F., and Lutkenhaus, J. (1991). FtsZ ring structure associated with division in Escherichia coli. Nature 354, 161–164. doi: 10.1038/354161a0

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Bi, E., and Lutkenhaus, J. (1993). Cell division inhibitors SulA and MinCD prevent formation of the FtsZ ring. J. Bacteriol. 175, 1118–1125.

Charoenwong, D., Andrews, S., and Mackey, B. (2011). Role of rpoS in the development of cell envelope resilience and pressure resistance in stationary-phase Escherichia coli. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77, 5220–5229. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00648-11

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Crago, A. M., and Koronakis, V. (1998). Salmonella InvG forms a ring-like multimer that requires the InvH lipoprotein for outer membrane localization. Mol. Microbiol. 30, 47–56. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01036.x

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Das, A. K., Cohen, P. W., and Barford, D. (1998). The structure of the tetratricopeptide repeats of protein phosphatase 5: implications for TPR-mediated protein-protein interactions. EMBO J. 17, 1192–1199. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.5.1192

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Datsenko, K. A., and Wanner, B. L. (2000). One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 6640–6645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.120163297

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

de Marco, A., Deuerling, E., Mogk, A., Tomoyasu, T., and Bukau, B. (2007). Chaperone-based procedure to increase yields of soluble recombinant proteins produced in E. coli. BMC Biotechnol. 7:32. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-7-32

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Du, Y., Zhang, H., He, Y., Huang, F., and He, Z. G. (2012). Mycobacterium smegmatis Lsr2 physically and functionally interacts with a new flavoprotein involved in bacterial resistance to oxidative stress. J. Biochem. 152, 479–486. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvs095

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Egan, A. J., Jean, N. L., Koumoutsi, A., Bougault, C. M., Biboy, J., Sassine, J., et al. (2014). Outer-membrane lipoprotein LpoB spans the periplasm to stimulate the peptidoglycan synthase PBP1B. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, 8197–8202. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1400376111

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Ehlert, K., Holtje, J. V., and Templin, M. F. (1995). Cloning and expression of a murein hydrolase lipoprotein from Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 16, 761–768. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02437.x

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Gaubig, L. C., Waldminghaus, T., and Narberhaus, F. (2011). Multiple layers of control govern expression of the Escherichia coli ibpAB heat-shock operon. Microbiology 157, 66–76. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.043802-0

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Gill, R. T., Valdes, J. J., and Bentley, W. E. (2000). A comparative study of global stress gene regulation in response to overexpression of recombinant proteins in Escherichia coli. Metab. Eng. 2, 178–189. doi: 10.1006/mben.2000.0148

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Han, M. J., Park, S. J., Park, T. J., and Lee, S. Y. (2004). Roles and applications of small heat shock proteins in the production of recombinant proteins in Escherichia coli. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 88, 426–436. doi: 10.1002/bit.20227

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Hiraga, S., Niki, H., Ogura, T., Ichinose, C., Mori, H., Ezaki, B., et al. (1989). Chromosome partitioning in Escherichia coli: novel mutants producing anucleate cells. J. Bacteriol. 171, 1496–1505.

Ichihara, S., Hussain, M., and Mizushima, S. (1981). Characterization of new membrane lipoproteins and their precursors of Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 256, 3125–3129.

Jiao, W., Qian, M., Li, P., Zhao, L., and Chang, Z. (2005). The essential role of the flexible termini in the temperature-responsiveness of the oligomeric state and chaperone-like activity for the polydisperse small heat shock protein IbpB from Escherichia coli. J. Mol. Biol. 347, 871–884. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.01.029

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Jurgen, B., Lin, H. Y., Riemschneider, S., Scharf, C., Neubauer, P., Schmid, R., et al. (2000). Monitoring of genes that respond to overproduction of an insoluble recombinant protein in Escherichia coli glucose-limited fed-batch fermentations. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 70, 217–224. doi: 10.1002/1097-0290(20001020)70:2<217::AID-BIT11>3.0.CO;2-W

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Kitagawa, M., Matsumura, Y., and Tsuchido, T. (2000). Small heat shock proteins, IbpA and IbpB, are involved in resistances to heat and superoxide stresses in Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 184, 165–171. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2000.tb09009.x

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Kitagawa, M., Miyakawa, M., Matsumura, Y., and Tsuchido, T. (2002). Escherichia coli small heat shock proteins, IbpA and IbpB, protect enzymes from inactivation by heat and oxidants. Eur. J. Biochem. 269, 2907–2917. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2002.02958.x

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Kuczynska-Wisnik, D., Laskowska, E., and Taylor, A. (2001). Transcription of the ibpB heat-shock gene is under control of sigma(32)- and sigma(54)-promoters, a third regulon of heat-shock response. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 284, 57–64. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.4926

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Kuczynska-Wisnik, D., Zurawa-Janicka, D., Narkiewicz, J., Kwiatkowska, J., Lipinska, B., and Laskowska, E. (2004). Escherichia coli small heat shock proteins IbpA/B enhance activity of enzymes sequestered in inclusion bodies. Acta Biochim. Pol. 51, 925–931.

Laskowska, E., Wawrzynow, A., and Taylor, A. (1996). IbpA and IbpB, the new heat-shock proteins, bind to endogenous Escherichia coli proteins aggregated intracellularly by heat shock. Biochimie 78, 117–122. doi: 10.1016/0300-9084(96)82643-5

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Li, Y., Hsin, J., Zhao, L., Cheng, Y., Shang, W., Huang, K. C., et al. (2013). FtsZ protofilaments use a hinge-opening mechanism for constrictive force generation. Science 341, 392–395. doi: 10.1126/science.1239248

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Ma, X., Ehrhardt, D. W., and Margolin, W. (1996). Colocalization of cell division proteins FtsZ and FtsA to cytoskeletal structures in living Escherichia coli cells by using green fluorescent protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 12998–13003. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.23.12998

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Malone, A. S., Chung, Y. K., and Yousef, A. E. (2006). Genes of Escherichia coli O157:H7 that are involved in high-pressure resistance. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72, 2661–2671. doi: 10.1128/AEM.72.4.2661-2671.2006

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Matuszewska, M., Kuczynska-Wisnik, D., Laskowska, E., and Liberek, K. (2005). The small heat shock protein IbpA of Escherichia coli cooperates with IbpB in stabilization of thermally aggregated proteins in a disaggregation competent state. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 12292–12298. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412706200

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Mogk, A., Mayer, M. P., and Deuerling, E. (2002). Mechanisms of protein folding: molecular chaperones and their application in biotechnology. Chembiochem 3, 807–814. doi: 10.1002/1439-7633(20020902)3:9<807::AID-CBIC807>3.0.CO;2-A

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Mukherjee, A., Cao, C., and Lutkenhaus, J. (1998). Inhibition of FtsZ polymerization by SulA, an inhibitor of septation in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 2885–2890. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.6.2885

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Nesta, B., Valeri, M., Spagnuolo, A., Rosini, R., Mora, M., Donato, P., et al. (2014). SslE elicits functional antibodies that impair in vitro mucinase activity and in vivo colonization by both intestinal and extraintestinal Escherichia coli strains. PLoS Pathog. 10:e1004124. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004124

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Ohara, M., Wu, H. C., Sankaran, K., and Rick, P. D. (1999). Identification and characterization of a new lipoprotein, NlpI, in Escherichia coli K-12. J. Bacteriol. 181, 4318–4325.

Ratajczak, E., Zietkiewicz, S., and Liberek, K. (2009). Distinct activities of Escherichia coli small heat shock proteins IbpA and IbpB promote efficient protein disaggregation. J. Mol. Biol. 386, 178–189. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.12.009

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Rouf, S. F., Ahmad, I., Anwar, N., Vodnala, S. K., Kader, A., Romling, U., et al. (2011a). Opposing contributions of polynucleotide phosphorylase and the membrane protein NlpI to biofilm formation by Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 193, 580–582. doi: 10.1128/JB.00905-10

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Rouf, S. F., Anwar, N., Clements, M. O., and Rhen, M. (2011b). Genetic analysis of the pnp-deaD genetic region reveals membrane lipoprotein NlpI as an independent participant in cold acclimatization of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 325, 56–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2011.02416.x

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Sanchez-Torres, V., Maeda, T., and Wood, T. K. (2010). Global regulator H-NS and lipoprotein NlpI influence production of extracellular DNA in Escherichia coli. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 401, 197–202. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.09.026

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Sorensen, H. P., and Mortensen, K. K. (2005). Advanced genetic strategies for recombinant protein expression in Escherichia coli. J. Biotechnol. 115, 113–128. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2004.08.004

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Strozecka, J., Chrusciel, E., Gorna, E., Szymanska, A., Zietkiewicz, S., and Liberek, K. (2012). Importance of N- and C-terminal regions of IbpA, Escherichia coli small heat shock protein, for chaperone function and oligomerization. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 2843–2853. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.273847

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Tadokoro, A., Hayashi, H., Kishimoto, T., Makino, Y., Fujisaki, S., and Nishimura, Y. (2004). Interaction of the Escherichia coli lipoprotein NlpI with periplasmic Prc (Tsp) protease. J. Biochem. 135, 185–191. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvh022

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Teng, C. H., Tseng, Y. T., Maruvada, R., Pearce, D., Xie, Y., Paul-Satyaseela, M., et al. (2010). NlpI contributes to Escherichia coli K1 strain RS218 interaction with human brain microvascular endothelial cells. Infect. Immun. 78, 3090–3096. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00034-10

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Tseng, Y. T., Wang, S. W., Kim, K. S., Wang, Y. H., Yao, Y., Chen, C. C., et al. (2012). NlpI facilitates deposition of C4bp on Escherichia coli by blocking classical complement-mediated killing, which results in high-level bacteremia. Infect. Immun. 80, 3669–3678. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00320-12

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Wai, S. N., Westermark, M., Oscarsson, J., Jass, J., Maier, E., Benz, R., et al. (2003). Characterization of dominantly negative mutant ClyA cytotoxin proteins in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 185, 5491–5499. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.18.5491-5499.2003

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Wilson, C. G., Kajander, T., and Regan, L. (2005). The crystal structure of NlpI. prokaryotic tetratricopeptide repeat protein with a globular fold. FEBS J. 272, 166–179. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.2004.04397.x

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Wu, L. J., and Errington, J. (2012). Nucleoid occlusion and bacterial cell division. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 10, 8–12. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2671

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Yao, Y., Sturdevant, D. E., and Otto, M. (2005). Genomewide analysis of gene expression in Staphylococcus epidermidis biofilms: insights into the pathophysiology of S. epidermidis biofilms and the role of phenol-soluble modulins in formation of biofilms. J. Infect. Dis. 191, 289–298. doi: 10.1086/426945

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Yao, Y., Xie, Y., and Kim, K. S. (2006). Genomic comparison of Escherichia coli K1 strains isolated from the cerebrospinal fluid of patients with meningitis. Infect. Immun. 74, 2196–2206. doi: 10.1128/IAI.74.4.2196-2206.2006

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Yu, F., Inouye, S., and Inouye, M. (1986). Lipoprotein-28, a cytoplasmic membrane lipoprotein from Escherichia coli. Cloning, DNA sequence, and expression of its gene. J. Biol. Chem. 261, 2284–2288.

Zhou, Y., Tao, J., Yu, H., Ni, J., Zeng, L., Teng, Q., et al. (2012). Hcp family proteins secreted via the type VI secretion system coordinately regulate Escherichia coli K1 interaction with human brain microvascular endothelial cells. Infect. Immun. 80, 1243–1251. doi: 10.1128/IAI.05994-11

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Zuckert, W. R. (2014). Secretion of bacterial lipoproteins: through the cytoplasmic membrane, the periplasm and beyond. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1843, 1509–1516. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2014.04.022

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Keywords: NlpI, Escherichia coli, cell division, heat shock protein IbpA and IbpB, stress response

Citation: Tao J, Sang Y, Teng Q, Ni J, Yang Y, Tsui SK-W and Yao Y-F (2015) Heat shock proteins IbpA and IbpB are required for NlpI-participated cell division in Escherichia coli. Front. Microbiol. 6:51. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00051

Received: 02 September 2014; Accepted: 15 January 2015;

Published online: 04 February 2015.

Edited by:

Dongsheng Zhou, Beijing Institute of Microbiology and Epidemiology, ChinaReviewed by:

Ching-Hao Teng, National Cheng Kung University, TaiwanMikael Rhen, Karolinska Institutet, Sweden

Copyright © 2015 Tao, Sang, Teng, Ni, Yang, Tsui and Yao. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yu-Feng Yao, Department of Microbiology and Immunology, Institutes of Medical Sciences, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, Rm 710, Bldg 5, 280 S. Chongqing Rd, Shanghai 200025, China e-mail:eWZ5YW9Ac2p0dS5lZHUuY24=

Jing Tao

Jing Tao Yu Sang1

Yu Sang1 Yi Yang

Yi Yang Stephen Kwok-Wing Tsui

Stephen Kwok-Wing Tsui Yu-Feng Yao

Yu-Feng Yao