Abstract

It was hypothesized that a lack of acetogenic biomass (biocatalyst) at the cathode of a microbial electrosynthesis system, due to electron and nutrient limitations, has prevented further improvement in acetate productivity and efficiency. In order to increase the biomass at the cathode and thereby performance, a bioelectrochemical system with this acetogenic community was operated under galvanostatic control and continuous media flow through a reticulated vitreous carbon (RVC) foam cathode. The combination of galvanostatic control and the high surface area cathode reduced the electron limitation and the continuous flow overcame the nutrient limitation while avoiding the accumulation of products and potential inhibitors. These conditions were set with the intention of operating the biocathode through the production of H2. Biofilm growth occurred on and within the unmodified RVC foam regardless of vigorous H2 generation on the cathode surface. A maximum volumetric rate or space time yield for acetate production of 0.78 g/Lcatholyte/h was achieved with 8 A/Lcatholyte (83.3 A/m2projected surface area of cathode) supplied to the continuous flow/culture bioelectrochemical reactors. The total Coulombic efficiency in H2 and acetate ranged from approximately 80–100%, with a maximum of 35% in acetate. The overall energy efficiency ranged from approximately 35–42% with a maximum to acetate of 12%.

Introduction

The desire to mitigate carbon dioxide emissions (32.1 billion tons CO2 emitted globally in 2015) (IEA, 2016) and find sustainable energy sources for increasing global demand have stimulated research in alternative electricity generation and non-fossil fuels. In 2015, 90% of new global electricity generation capacity was renewable (IEA, 2016). With stranded and off peak power, there is a need to balance the energy in the grid and take advantage of every renewable kWh available. One technology that may help address this in the future is microbial electrosynthesis. Utilizing any electricity source, but preferably a sustainable one, different anaerobic microbes have produced several chemicals of interest by using CO2 as the sole carbon source when operating at the cathode of an electrochemical cell (Nevin et al., 2010; Logan and Rabaey, 2012; Marshall et al., 2012, 2013; Lovley and Nevin, 2013; LaBelle et al., 2014; Blanchet et al., 2015; Jourdin et al., 2015; Schröder et al., 2015; Ammam et al., 2016; Deutzmann and Spormann, 2016).

Ultimately, products from microbial electrosynthesis would include high value chemicals and liquid fuels. However, simply producing a single C-C bond such as in acetate would be worthwhile and much of the work done thus far has focused on electroacetogenesis (Conrado et al., 2013; May et al., 2016). Closely related to this is the bioconversion of syngas (H2, CO, and CO2) to fuels and chemicals (Daniell et al., 2012, 2016; Hu et al., 2013, 2016), and within this area of research is the study of H2:CO2 transformation to acetate by acetogenic bacteria. Acetate itself is of commercial importance and it can be transformed further into other products (Andersen et al., 2014; Hu et al., 2016; Pal and Nayak, 2016). For these reasons there has been a significant effort recently to improve the rates and efficiency of acetogenesis with H2:CO2 or bioelectrochemically.

Previous work in gas fermentations has illuminated reaction conditions that can limit or enhance the rates of acetogenesis. Demler and Weuster-Botz (2011) achieved a volumetric productivity or space time yield (STY) of 0.31 g/L/h with Acetobacterium woodii in a batch stirred tank reactor pressurized with H2:CO2. Later Kantzow et al. (2015) achieved an impressive STY of 6.16 g/L/h in continuous flow stirred tank reactors (CSTR). The investigators demonstrated that increasing the dilution rate and increasing biomass retention led to higher acetate productivity. Hu et al. (2013) showed that in bubble columns, electron transfer to Moorella thermoacetica was limited by the mass transfer of CO into solution at rates below 30 mM/h, which is a volumetric current density equivalent to 1.6 A/L. Hu et al. (2016), an improved design led to a STY of 1.1 g/L/h of acetate from H2:CO2 by M. thermoacetica first grown with CO. The investigators integrated the process with Yarrowia lipolytica to produce biodiesel precursors, thereby demonstrating the feasibility of linking syngas fermentation with an acetate-consuming biofuel-producing process. Overall, these investigations indicate that fuel and chemical production could be driven by H2 gas fermentations at industrially relevant rates. Could this be accomplished with microbial electrosynthesis?

The objective of this study was to improve the productivity and efficiency of microbial electrosynthesis through reactor design and operation (galvanostatic mode, H2 mediation, continuous flow). Data from previous studies with an acetogenic community used in bioelectrochemical systems with graphite granule cathodes (Marshall et al., 2012, 2013; LaBelle et al., 2014) generally indicated that the early reactors were of an inefficient design and that more biomass at the cathode was likely needed to improve performance. Patil et al. (2015) discussed and demonstrated the utility of delivering electrons in a MES with galvanostatic operation, and this also resulted in faster startup times and improved scalability. Instead of waiting for higher rates of H2 evolution from the electrode as in previous MES studies operated potentiostatically, here it was hypothesized that using a high volumetric current density surpassing the 1.6 A/L elucidated from Hu et al. (2013) would result in shorter startup times, faster biomass growth rate, and faster acetate production. Biomass growth would also benefit from a continuous flow of nutrients, and a nitrogen limitation was indicated by the upregulation of nitrogen fixing enzymes in batch-fed bioelectrochemical reactors (Marshall et al., 2016). Continuous flow of media will also alleviate product inhibition (Demler and Weuster-Botz, 2011; Kantzow et al., 2015), decrease the reactor footprint, and facilitate pH control; this acetogenic community has an acetate and H2 product ratio that is affected by pH in potentiostatic systems (LaBelle et al., 2014). Thus, galvanostatic control and continuous flow were applied to a reactor designed for better energy efficiency and STY, which are also important to decrease capital and operating costs (Krieg et al., 2014; Papoutsakis, 2015). The goal was to develop a system that could be used to reach g/L/h productivity while maintaining a high energy efficiency. This was done with high current density normalized to surface area (projected and geometric). However, since the acetate product is soluble, the volumetric current density is important when considering the reactor productivity as well as product titer needed to devise an efficient extraction scheme (Krieg et al., 2014; Gildemyn et al., 2015; Papoutsakis, 2015; Patil et al., 2015). The approach resulted in a considerable enhancement of productivity and efficiency.

Materials and Methods

Bioelectrochemical Reactor

The modular and scalable reactors were designed and constructed as depicted in Supplementary Figures S1A,B. The 45 pores per inch (17.7 pores per cm) reticulated vitreous carbon (RVC) foam cathode (KR Reynolds Company) was 0.6 cm × 6 cm × 8 cm (surface area to volume ratio of 26.2 cm2/cm3 per manufacturer). It was pretreated in 2N nitric acid and rinsed thoroughly with MilliQ water. It was then attached to a 6 × 6 mesh, 0.89 mm wire diameter 316L stainless steel mesh (6 cm × 8 cm) current collector that was coated with a conductive graphite and carbon black acrylic glue (Ted Pella Inc. #16050) thinned with 1:1 (v/v) acetone. Two applications were coated onto the mesh before the same glue was used to attach the RVC foam. The anode was a mixed metal oxide (IrO2/Ta2O5) catalyzed titanium anode (MMO; Magneto).

Custom machined polypropylene spacers were used with customized Viton gaskets to sandwich a cation exchange membrane (CMI-7000, Membranes International Inc.) between the electrodes with a 316L stainless steel endplate and a poly(methyl methacrylate; PMMA) cathode viewing plate held together by stainless steel nuts, bolts and washers. The polypropylene spacers were 0.95 cm × 10 cm × 10 cm, with a square opening of 8 cm × 8 cm. The steel plate was 0.95 cm × 15.2 cm × 15.2 cm. The PMMA cathode viewing plate was 1.25 cm × 15.2 cm × 15.2 cm. The membrane and exposed anode surface area were each 64 cm2. The projected cathode surface area was 48 cm2. Polypropylene Luer fittings (McMaster Carr) were used as ports to connect tubing. Reference electrodes were constructed using a AgCl coated silver wire immersed in 3M KCl saturated with AgCl in a glass capillary tube with a Vycor frit attached via heat shrink tubing. A Luggin capillary was integrated in the reactor using 1 M KCl as supporting electrolyte, and its Vycor frit was ∼2 mm from the cathode.

The anolyte was 75 mL of 50 mM sodium sulfate acidified with sulfuric acid to pH = 2. The catholyte was 50 mL of a phosphate-based medium initially prepared at pH 7 under 100% N2 as described in LaBelle et al. (2014). It contained salts, vitamins and trace metals and minerals. 50 mM NaCl was used instead of sodium bromoethanesulfonate. No yeast extract, sulfide or cysteine was used.

Reactor Operation

An acetogenic microbiome previously enriched on graphite granule cathodes at potentials from -590 to -800 mV vs. SHE was used to inoculate the bioreactors (LaBelle et al., 2014). The cells were drawn from the cathode compartment of an active reactor and were concentrated using tangential flow filtration using a 0.2 μm polyethersulfone filter (Sartorius), spun at 5000 (RCF) for 10 min and re-suspended in fresh medium before transfer to the RVC cathode reactors. The culture, inoculum and reactor, were treated as an open, non-aseptic system.

The reactor was operated at 25°C with constant current supplied from a VMP3 Potentiostat (BioLogic) set in galvanostatic mode and the voltage monitored with EC Lab software. A galvanostatic operation of 8 A/Lcatholyte was chosen to overcome electron limitation to a biofilm immobilized on the cathode and promote fast colonization. Humidified 100% CO2 was passed through the catholyte headspace using Norprene tubing at an initially set rate of 25 mL/min. Filter sterilized medium was flowed into the base of the cathode compartment and exited just above the top of the RVC cathode at a rate of 250 mL/day (a dilution rate of 5 day-1) using a peristaltic pump and PharMed BPT tubing. Deionized water was added to ports made from syringe housing on the anolyte compartment daily to compensate for water oxidation and evaporation.

Sampling and Analysis

The gas flow rate was monitored with an Agilent gas flow meter when sampling headspace for gas chromatographic analysis, and fatty acids were analyzed via HPLC (LaBelle et al., 2014). The pH of samples drawn from the cathode chamber was checked with a pH meter (Mettler Toledo). Optical density of the planktonic cells (OD600nm) was measured at 600 nm using a Genesys UV/Vis spectrophotometer.

Space time yield was calculated as the STY = concentration times flow rate divided by catholyte volume (Krieg et al., 2014). The Coulombic efficiencies were calculated from the partial current densities of each product divided by the total applied current. Energy efficiencies were obtained by using the higher heating value (HHV) of product multiplied by the STY and then divided by the applied electrical energy to the reactor per time (Krieg et al., 2014).

Results and Discussion

Biomass Growth

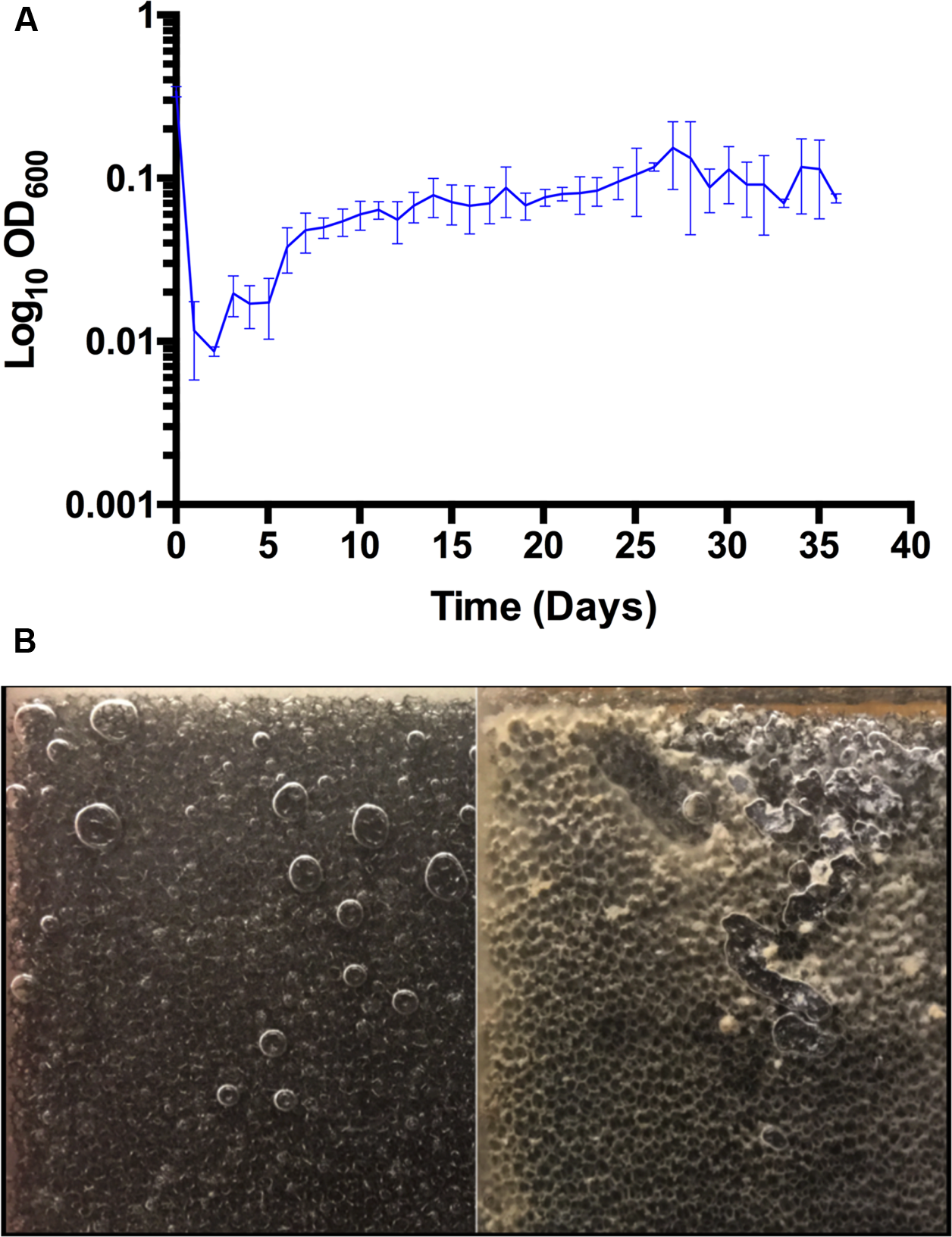

The initial inoculum resulted in an optical density (OD600nm) of 0.34 ± 0.01 (n = 3) within the cathode chamber of three inoculated reactors (Figure 1A). The continuous flow of media through the reactors, and perhaps adsorption of biomass to the electrode surface, drove the OD600nm down by more than an order of magnitude. Shortly thereafter the OD600nm began to steadily increase and eventually remained near or above 0.1 within the reactors, indicating a constant production of bacterial cells including those that remained planktonic and were washed away with the effluent. A coating of the unmodified cathode surface with yellow and off-white material became apparent within a week of inoculation and grew heavier until the end of the experiment (Figure 1B). Microscopic examination of the material from the electrode surface and from within the interstitial space revealed that it was densely populated with bacterial cells similar to Acetobacterium in morphology, the genus that dominated the inoculum (LaBelle et al., 2014). Although the biomass on the electrodes was not quantified, visually it was apparent that the colonization of the electrode continued until the experiment was terminated.

FIGURE 1

(A) Optical density (600 nm) of planktonic cells in triplicate bioelectrochemical reactors (SD, n = 3). (B) Biofilm growth on RVC cathode. Photographs of uninoculated (left) and inoculated (right) 45 ppi RVC cathodes at 36 days.

While graphite granule cathodes were effective at enriching the community (Marshall et al., 2012, 2013; LaBelle et al., 2014), and are a relatively inexpensive and high surface area electrode for electroactive biofilms, their drawbacks include gas hold up, high resistance, high granular void volume, and restriction of liquid flow for continuous operation, thus warranting a different electrode geometry. RVC was chosen because of its high surface area to volume ratio, low solid void volume due to the glassy carbon (97% air-liquid void volume), and this electrode material performs well for flow through systems (Krieg et al., 2014). Unmodified RVC has been reported to be a poor surface for bioelectrochemical systems (Flexer et al., 2013), and it did not support the electrosynthesis of any acetate with another microbial community (Jourdin et al., 2014) unless its glassy carbon surface was coated with carbon nanotubes (Jourdin et al., 2015). For the latter case a current density of 0.055 A/L (102 A/m2projected surface area) and an acetate rate of 0.015 g/L/h and electron recovery of 100% were achieved under poised potential conditions in a batch-fed reactor. In contrast, the microbial community used under the conditions described here (8 A/L, 83 A/m2projected surface area) readily colonized the unmodified RVC and generated acetate (see below) with this material serving as a biocathode. Microbubbles vigorously effervesced throughout and larger bubbles coalesced on the cathodes during the start-up. One may expect this to limit or even prevent the formation of a biofilm on the surface and within the honeycomb of the cathode (Blanchet et al., 2015; Bergel, 2016). However, biofilm became clearly visible on the cathodes following inoculation (confirmed by optical microscopy) while no visible changes were observed for more than a month with uninoculated RVC maintained under the same conditions. It is likely that biological and non-biological material was deposited on the cathode, but this was only visible when the cathodes were inoculated and the key to improved productivity was probably due to the increase in biomass on and within the RVC. Furthermore, there were no indications at the end of the experiment that the biomass/biofilm could not be increased further, which may additionally improve productivity and efficiency. How this biofilm forms and how it influences hydrogen formation and transfer, acetogenesis, and overall performance will require further inquiry.

Productivity

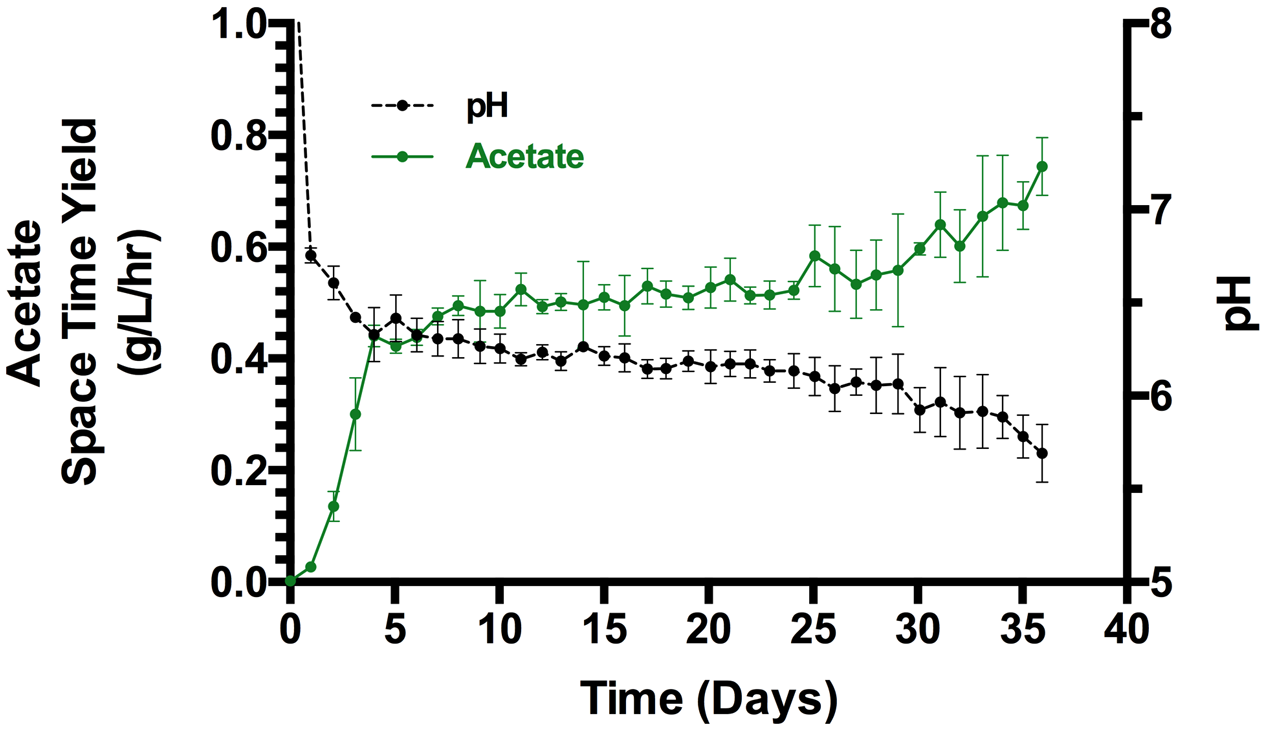

The STY of acetate was monitored in the three inoculated continuous flow/constant current reactors (Figure 2). Within the first 4 days of operation, the STY rapidly increased to >0.4 g/Lcatholyte/h. From this point forward the rate steadily increased and was accelerating at the end of the experiment (day 36) when the STY reached a maximum of 0.78 g/Lcatholyte/h, 0.74 ± 0.05 g/Lcatholyte/h in replicates (n = 3). The maximum acetate produced per electrode surface area was 8.2 g/m2projected/h. Hydrogen was co-produced at 0.2 g/Lcatholyte/h at the end of the experiment. Other products included formate, propionate, and butyrate produced at <0.02 g/Lcatholyte/h (Supplementary Figure S2). No methane was detected and biomass growth and acetate production were sustained without the addition of methanogenic inhibitors, yeast extract, or chemical reducing agents.

FIGURE 2

Space time yield of acetate and pH of triplicate bioelectrochemical reactors (SD, n = 3).

Shortly after inoculation, the pH of the biotic reactors rose abruptly to 8.88 ± 0.53 due to the production of base at the cathode of the electrochemical cell. However, the continuous supply of CO2 and medium flow returned the pH to 6.75 ± 0.03 within 24 h. The pH decreased as the microbial production of acetic acid increased and the change in pH was more rapid at the end of the experiment. A single uninoculated reactor was maintained under the same conditions as the three inoculated reactors (Supplementary Figure S3). After an initial upward spike in pH during the 1st day, the pH stabilized at 6.67 ± 0.03 for the remainder of the experiment.

Efficiency

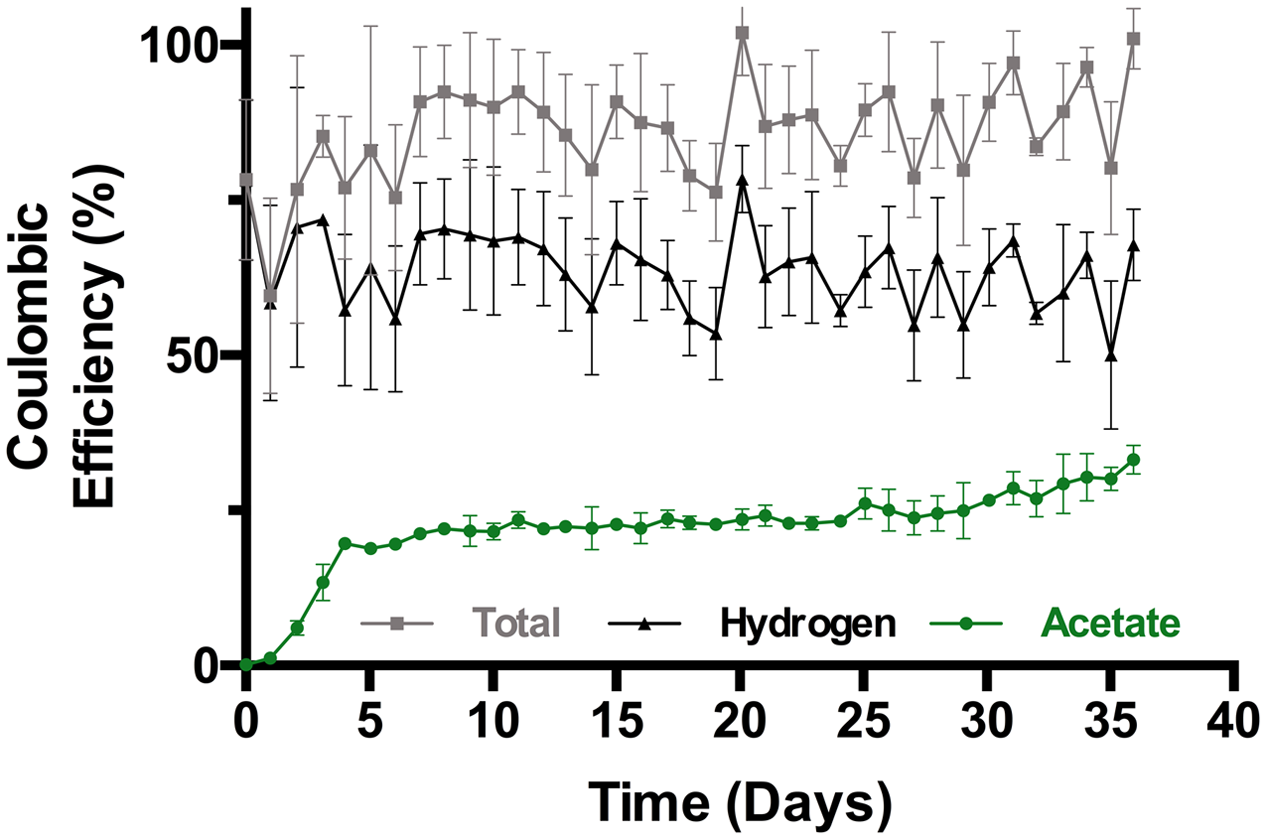

Following the initial start-up, the overall Coulombic efficiency (CE) ranged from approximately 75–85% with about 20% in acetate (Figure 3). From then to the end of the experiment the overall CE ranged between approximately 80 and 100% with most of the variability in the measurement of H2 (the CE for the single uninoculated control reactor was 88%). The electron recovery in acetate steadily increased to 33.2% ± 2.3% (n = 3) at day 36 with 35% in one reactor.

FIGURE 3

Coulombic efficiency of triplicate bioelectrochemical reactors (SD, n = 3).

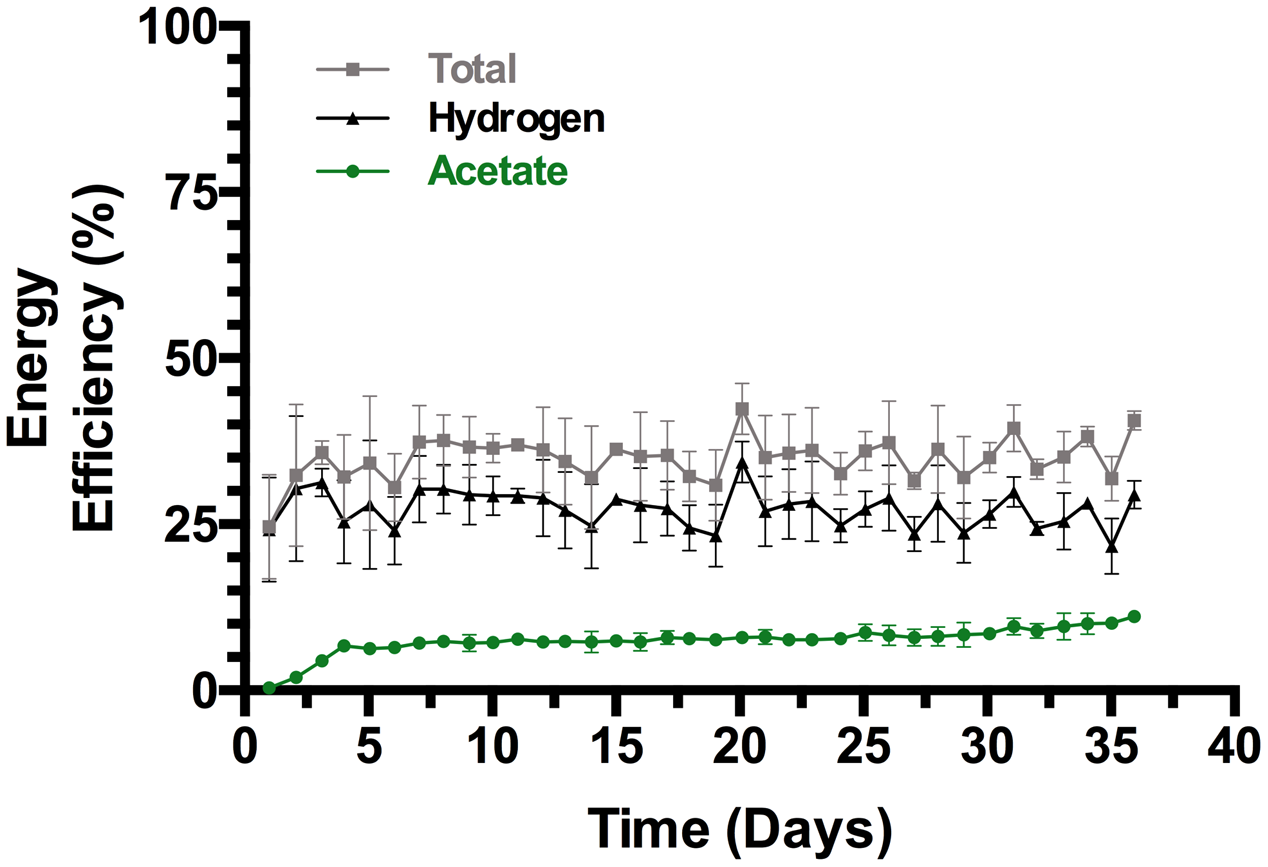

The trend in energy efficiency (Figure 4) generally followed that of the CE (Figure 3), and both efficiencies paralleled the increase in the STY of acetate (Figure 2). Following the initial increase in productivity during the first 4 days of incubation the energy efficiency fluctuated between 30 and 35% with approximately 7% invested in acetate. From then to the end of the experiment, the overall energy efficiency varied between 35 and 42% while the energetic efficiency in acetate steadily increased to 11.2% ± 0.8% (n = 3) with a 12.1% maximum in one reactor at the end of the experiment. Both the CE and energy transferred to acetate were increasing at the end of the experiment.

FIGURE 4

Energy efficiency of triplicate bioelectrochemical reactors (SD, n = 3).

Voltage ranged from 3.2 to 3.6 over time with all three reactors, and potential at the cathodes was -1.1 to -1.3 V vs. SHE (Standard Hydrogen Electrode) with no clear trend up or down. The power consumption of the reactors is depicted in Supplementary Figure S4. Better electrode spacing and a more efficient anode may improve the efficiency of the reactors. What would likely most improve the efficiency to acetate for these bioelectrochemical reactors is to avoid the loss of H2; this may be related to retaining more biomass in the reactor. Adding pH control and additional cell retention to the system may be the solution. The RVC is enabling some cell retention in the reactor in addition to efficient electron delivery, but the contribution from cells on the electrode vs. within the honeycomb of the electrode or suspended in the medium is unknown, and there is a significant fraction of planktonic biomass that is presently lost with the continuous flow (∼0.1 OD600nm). Hence further cell retention in the cathode chamber may additionally enhance productivity and efficiency and the results warrant a more detailed examination of the biofilm formation on the cathodes in relation to productivity and efficiency. For example, attaining a 100% CE to acetate under the current presently applied could result in a STY of 2.2 g/L/h and an energy efficiency >30% to acetate.

Microbial Electrosynthesis vs. Gas Fermentations

When comparing the supply of electrons (H2) supplied to gas-liquid contacting (GLC) bioreactors (Demler and Weuster-Botz, 2011; Hu et al., 2013, 2016; Kantzow et al., 2015), it became apparent that the electrons supplied to the bioelectrochemical reactors in the past (Marshall et al., 2012, 2013; LaBelle et al., 2014) were limited and this precluded any chance of high productivity and likely blunted the growth of biomass; hence the remedy described above. Abiotic and biotic activity may functionalize the surface of the cathode, thereby facilitating the production of H2 or formate for the eventual generation of acetate and other products (LaBelle et al., 2014; Yates et al., 2014; Deutzmann et al., 2015; Marshall et al., 2016; May et al., 2016), and the results presented here were dependent upon the addition of the microbial community, but the electrochemical bioreactors were intentionally operated through H2 with the goal of improving productivity and efficiency. Therefore, it is reasonable to compare microbial electrosynthesis with H2 gas fermentations (Blanchet et al., 2015; Tremblay et al., 2016).

Microbial electrosynthesis may be indirectly approached by the coupling of a H2 producing electrolyzer with a GLC bioreactor such as a CSTR or a continuous flow bubble column where H2 is delivered to a fuel or chemical producing microbe (e.g., an acetogen). Alternatively, during direct MES the microbes are incubated with the cathode of an electrochemical cell where they capture H2 or possibly electrons directly from an electrode (Butler and Lovley, 2016; Tremblay et al., 2016). Productivity and efficiency data from these two approaches are presented in Table 1. A 70% energy efficiency for an electrolyzer (Körner et al., 2015), based on a HHV of H2, was assumed for calculating the efficiency of an indirect MES with two reactors. Following growth with CO in a continuous flow bubble column with cell retention, the thermophile M. thermoacetica produced acetate at 1.1 g/L/h when supplied with H2:CO2, but there was a trade-off with efficiency when examining it as part of an indirect MES. The M. thermoacetica system was designed for use with hot syngas and the high temperature (60°) lowered the solubility of the H2 (Hu et al., 2013, 2016), which required high sparging rates to overcome mass transfer and reduced efficiency.

Table 1

| Organism | Reactors | Temp. (C) | Dilution rate (d-1) | Yeast extract (g/L) | HFM# | pH stat∗ | Acetate (g/L/h) | Acetate electron recovery | Acetate energy efficiency | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moorella thermoacetica | 70% EE electrolyzer | Bubble column | 60° | 2.16 | 10 | Yes | Yes | 1.1 | 3.7% | 2.0% | Hu et al., 2016 |

| Acetobacterium woodii | 70% EE electrolyzer | CSTR | 30° | 0.84 | 4 | No | Yes | 0.76 | 10.3% | 4.6%a | Kantzow et al., 2015 |

| Acetobacterium woodii | 70% EE electrolyzer | CSTR | 30° | 8.4 | 4 | Yes | Yes | 6.16 | 55.9% | 26.4%a | Kantzow et al., 2015 |

| Acetobacterium sp. (mix) | Bioelectrochemical constant currentb | 25° | 5 | 0 | No | No | 0.78 | 35% | 12.1% | This study | |

| Clostridiales (mix) | Bioelectrochemical constant currentc | 21° | Batch | 0 | No | No | 0.024 | 61% | 21% | Gildemyn et al., 2015 | |

| Sporomusa ovata | Bioelectrochemical constant voltaged | 25° | 0.0144 | 0 | No | No | 0.0009 | 105% | 50% | Giddings et al., 2015 | |

Indirect vs. direct microbial electrosynthesis of acetate.

Acetate electron recovery for indirect MES was based on electrons in acetate produced divided by the total electrons sparged as H2 through the reactor from the electrolyzer. Acetate energy efficiency was calculated using the HHV of acetate produced divided by the energy to power an electrolyzer that has a 70% energy efficiency (EE) based on the HHV of H2 produced. aTotal energy applied included energy required for stirring the CSTR. bApplied Current: 8 A/Lcatholyte (83.3 A/m2projected). cApplied Current: 0.143 A/Lcatholyte (5 A/m2projected). dApplied Voltage: 1.9 V. Hollow fiber membranes are used for full cell retention. #Hollow fiber membrane. ∗pH auxostat system.

When assessed as an indirect MES, a CSTR with A. woodii (Kantzow et al., 2015) produced acetate at nearly the same rate (0.76 g/L/h) but with substantially higher efficiency than M. thermoacetica in a bubble column. The highest acetate productivity (6.16 g/L/h) in combination with a high CE (55.9%) and energy efficiency (26.4%, estimated as an indirect MES including stirring energy) was achieved with A. woodii incubated in a CSTR with cell retention and a high rate of dilution (Kantzow et al., 2015). This energy efficiency does not match the 39–50% reported for a membraneless direct MES reactor operated in batch under constant applied voltage (Giddings et al., 2015), but due to its productivity the CSTR coupled with an electrolyzer is for now a more feasible approach. The energy efficiency of the direct MES described in the present study does exceed many of these other systems while maintaining high productivity, but its performance does not yet match that of the CSTR run with cell retention and a high dilution rate. However, as noted above the productivity and efficiency of the direct MES may be improved with more pH control and cell retention.

The results described here indicate the productivity and efficiency of a direct MES operating through H2 in a single reactor is approaching that of an indirect MES using two reactors. Furthermore, rates of acetogenesis from H2:CO2 within GLC bioreactors are now on par with the productivity of ethanol fermentation and direct MES is approaching it. Starch (corn) ethanol is commercially produced at 1.25 to 3.75 g/Lreactor volume/h (Graves et al., 2006; Richter et al., 2013), but this rate of production ignores the time, arable land, and energy needed to grow, harvest, transport, and pretreat the substrate prior to fermentation (Fast and Papoutsakis, 2012; Conrado et al., 2013). Ethanol and acetate do not possess the same energy or commercial value and absolute comparisons of their production cannot be made. But the aforementioned comments are insightful since bioethanol from starch is the largest biorefinery process scaled to date, and if electrosynthesis of acetate or any other chemical is to ever be viable then productivity must be within the range of bioethanol production.

Cost, Titer, and Extraction

At the efficiency and rates described here for electroacetogenesis, 33.6 kWh are needed to produce 1 kg of acetate with a direct MES and 15.4 kWh with an indirect MES using a CSTR. At $0.02 per kWh (national average levelized price of wind power purchase agreements) (Wiser and Bolinger, 2016), the electricity cost for 1 kg of acetate would range from $0.31 to $0.67; as with any system, the need for extraction and purification would undoubtedly add to this cost (Gildemyn et al., 2015; Papoutsakis, 2015; Xu et al., 2015). The global price of acetic acid has ranged from $0.35 to $0.95 per kg between 2010 and 2015 (Wakatsuki, 2015), while U.S. domestic acetic acid spot pricing was at $0.49 per kg and U.S. spot export pricing was at $0.60–$0.63 per kg in September of 2016 (Raizada, 2016). Prices from $0.90 to $1.60 per kg were also reported in a variety of countries during 2015 and 2016 (Nayak and Pal, 2015; Nayak et al., 2015; Pal and Nayak, 2016). While these quotes indicate a range of possible commercial values for acetate, they also show that further improvements in electrosynthesis performance remain desirable. Selling the excess hydrogen and oxygen simultaneously produced could attain additional revenue, and increases in efficiency will help. For example, achieving 100% CE under the same conditions in this work would lower the energy requirement to 12 kWh per kg, with $0.24 in electricity costs per kg acetate produced. However, titer is another factor that affects purification costs. The titer reached 3.6 g/L in the present experiment and 10.5 g/L in past batch experiments with the same microbial community (Marshall et al., 2013). Optimizing the dilution rate in relation to nutrient supply, pH control, and cell retention will increase the titer in the continuous flow/constant current reactors, but significantly higher titer still needs to be achieved.

A promising approach to increase titer has been demonstrated by Gildemyn et al. (2015), who reported on a galvanostatic microbial electrosynthesis system in batch mode that produced acetate at 0.024 g/L/h, and simultaneously extracted the acetate across an anion exchange membrane to concentrate the product in an integrated extraction compartment of equal volume to the catholyte. This method obviates the need for an external pH control system, and the 13.5 g/L titer achieved with this method is the highest reported for a direct MES. The energy efficiency to acetate, including the extraction, reached an impressive 21%.

Another possible solution is to supply the acetate to a second bioreactor that produces higher value products that may be produced at a higher titer and are more readily extracted, such as demonstrated by Hu et al. (2016) for the production of biodiesel precursors. Chemocatalytic upgrading has also been used to produce ethyl acetate by combining biphasic esterification with an integrated electrolytic membrane extraction of acetate from fermentation of thin stillage biomass (Andersen et al., 2014). This process was also adopted to utilize acetate made from electricity and CO2 to produce the ethyl acetate (Andersen et al., 2016).

Additional Considerations

Yeast extract has been required for the growth of acetogens in some studies (Kantzow et al., 2015; Hu et al., 2016), and at the concentrations and dilution rates used would be cost prohibitive (Lawford and Rousseau, 1997; Lau et al., 2012). A metagenomic analysis indicated that the microbial community used here possesses the full complement of genes required for the synthesis of all amino acids and vitamins needed for growth (Marshall et al., 2016), and yeast extract has never been used with this community.

The experiments reported here were done with a phosphate buffer, and to continuously supply that would also be cost prohibitive at the dilution rates in this study. Past batch-fed experiments were done with a bicarbonate buffer in place of the phosphate (LaBelle et al., 2014), which would be far more cost effective (est. 80% media cost reduction).

Both hydrogenotrophic and acetoclastic methanogens would divert electrons away from acetate synthesis. Inhibition of methanogenesis can be costly, but no inhibitor was needed for this experiment or for preparation of the inoculum. Operating a direct MES reactor through H2 under galvanostatic control may offer a competitive advantage for the acetogens versus methanogens in that high H2 partial pressure favors acetogenesis. Furthermore, allowing the pH to drop below 6 may also favor the acetogens since lower pH can also inhibit methanogenesis (Ni et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2013; Spirito et al., 2014). Methanogens initially present in the community enriched for this biocathode were eliminated by repeated exposure to high H2, low pH, and the addition of the inhibitor sodium bromoethanesulfonate (NaBES) (Marshall et al., 2012, 2013; LaBelle et al., 2014). The use of NaBES with this microbial community was ended in 2014, it was not used at any time in this study, and the inoculum used was transferred more than three times without NaBES before use in this study. The community used in this study has always been maintained in an open system (non-aseptic) in a laboratory with methanogenic cultures and sediments under investigation nearby.

The scalability and economics of MESs has been addressed in several studies and reviews (Foley et al., 2010; Desloover et al., 2012; Logan and Rabaey, 2012; Conrado et al., 2013; Brown et al., 2014; Harnisch et al., 2014; ElMekawy et al., 2016; Zhang and Angelidaki, 2016). Additionally, current legislation concerning whether the CO2 is obtained from renewable or waste gasses can vary geographically (Daniell et al., 2016; Dürre, 2016). This can affect whether the product can qualify for credits and incentives, and thus be sold competitively. However, a life cycle analysis has shown that ethanol produced from CO2 recycled from a fossil fuel waste stream can still attain a net carbon emission reduction (Daniell et al., 2016; Handler et al., 2016). Further improvements in performance are still desired and product selection should go beyond acetate, but with productivity and efficiency for a direct single reactor MES approaching the best reported for an indirect MES with two reactors, successful scaling and improved performance of microbial electrosynthesis is now more feasible. Building and operating one reactor versus two may reduce capital and operating costs, and the performance of the reactor systems for acetogenesis compared in Table 1 suggest such a consolidation warrants further consideration. What is needed is a systematic laboratory comparison of direct and indirect MES systems. Such data will help develop practical process systems and better inform life cycle assessments and technoeconomic analyses to contribute to proper implementation of MES.

Conclusion

This work contributes practical operating conditions for microbially producing acetic acid from electricity and carbon dioxide, with hydrogen as co-product, bringing the technology closer to real world implementation. Additionally new benchmarks in STY and efficiency are presented. Acetate was produced at a maximum STY of 0.78 g/L/h, and in replicate 0.74 ± 0.05 g/L/h (n = 3). The growth of this technology and its promise in complementation to other established and emerging technologies indicate the viability of microbial electrosynthesis to aid in carbon and energy management.

Statements

Author contributions

EL and HM designed and planned the research, EL conducted the experiments, and EL and HM analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the Office of Naval Research grant #N00014-15-1-2219.

Conflict of interest

Patents pending in relation to this work: 1. Harold D. May, Marshall CW, and Edward V. LaBelle. Microbial Electrosynthetic Cells. PCT/US2013/060131. International filing date: 17 September 2013. 2. 1. Harold D. May and Edward V. LaBelle. Provisional Application for United States Letters Patent for Bioelectrosynthesis of Organic Compounds. November 3, 2016.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fmicb.2017.00756/full#supplementary-material

References

1

AmmamF.TremblayP. L.LizakD. M.ZhangT. (2016). Effect of tungstate on acetate and ethanol production by the electrosynthetic bacterium Sporomusa ovata.Biotechnol. Biofuels9163. 10.1186/s13068-016-0576-0

2

AndersenS. J.BertonJ. K. E. T.NaertP.GildemynS.RabaeyK.StevensC. V. (2016). Extraction and esterification of low-titer short-chain volatile fatty acids from anaerobic fermentation with ionic liquids.ChemSusChem92059–2063. 10.1002/cssc.201600473

3

AndersenS. J.HennebelT.GildemynS.ComaM.DeslooverJ.BertonJ.et al (2014). Electrolytic membrane extraction enables production of fine chemicals from biorefinery sidestreams.Environ. Sci. Technol.487135–7142. 10.1021/es500483w

4

BergelA. (2016). How could chemical engineering help in deciphering electromicrobial mechanisms?BIO Web Conf.6:02005. 10.1051/bioconf/20160602005

5

BlanchetE.DuquenneF.RafrafiY.EtcheverryL.ErableB.BergelA. (2015). Importance of the hydrogen route in up-scaling electrosynthesis for microbial CO2 reduction.Energy Environ. Sci.83731–3744. 10.1039/C5EE03088A

6

BrownR. K.HarnischF.WirthS.WahlandtH.DockhornT.DichtlN.et al (2014). Evaluating the effects of scaling up on the performance of bioelectrochemical systems using a technical scale microbial electrolysis cell.Bioresour. Technol.163206–213. 10.1016/j.biortech.2014.04.044

7

ButlerC. S.LovleyD. R. (2016). How to sustainably feed a microbe: strategies for biological production of carbon-based commodities with renewable electricity.Front. Microbiol.7:1879. 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01879

8

ConradoR. J.HaynesC. A.HaendlerB. E.TooneE. J. (2013). “Electrofuels: a new paradigm for renewable fuels,” in Advanced Biofuels and Bioproducts, ed.LeeJ. W. (New York, NY: Springer Science & Business Media), 1037–1064. 10.1007/978-1-4614-3348-4_38

9

DaniellJ.KöpkeM.SimpsonS. D. (2012). Commercial biomass syngas fermentation.Energies5:5372. 10.3390/en5125372

10

DaniellJ.NagarajuS.BurtonF.KöpkeM.SimpsonS. D. (2016). Low-carbon fuel and chemical production by anaerobic gas fermentation.Adv. Biochem. Eng.156293–321.

11

DemlerM.Weuster-BotzD. (2011). Reaction engineering analysis of hydrogenotrophic production of acetic acid by Acetobacterium woodii.Biotechnol. Bioeng.108470–474. 10.1002/bit.22935

12

DeslooverJ.ArendsJ. B. A.HennebelT.RabaeyK. (2012). Operational and technical considerations for microbial electrosynthesis.Biochem. Soc. Trans.401233–1238. 10.1042/BST20120111

13

DeutzmannJ. S.SahinM.SpormannA. M. (2015). Extracellular enzymes facilitate electron uptake in biocorrosion and bioelectrosynthesis.mBio6:e00496–15. 10.1128/mBio.00496-15

14

DeutzmannJ. S.SpormannA. M. (2016). Enhanced microbial electrosynthesis by using defined co-cultures.ISME J.11704–714. 10.1038/ismej.2016.149

15

DürreP. (2016). Gas fermentation - a biotechnological solution for today’s challenges.Microb. Biotechnol.1014–16. 10.1111/1751-7915.12431

16

ElMekawyA.HegabH. M.MohanakrishnaG.ElbazA. F.BulutM.PantD. (2016). Technological advances in CO2 conversion electro-biorefinery: a step toward commercialization.Bioresour. Technol.215357–370. 10.1016/j.biortech.2016.03.023

17

FastA. G.PapoutsakisE. T. (2012). Stoichiometric and energetic analyses of non-photosynthetic CO2-fixation pathways to support synthetic biology strategies for production of fuels and chemicals.Curr. Opin. Chem. Eng.11–16. 10.1016/j.coche.2012.07.005

18

FlexerV.ChenJ.DonoseB. C.SherrellP.WallaceG. G.KellerJ. (2013). The nanostructure of three-dimensional scaffolds enhances the current density of microbial bioelectrochemical systems.Energy Environ. Sci.61291–1298. 10.1039/c3ee00052d

19

FoleyJ. M.RozendalR. A.HertleC. K.LantP. A.RabaeyK. (2010). Life cycle assessment of high-rate anaerobic treatment, microbial fuel cells, and microbial electrolysis cells.Environ. Sci. Technol.443629–3637. 10.1021/es100125h

20

GiddingsC. G. S.NevinK. P.WoodwardT.LovleyD. R.ButlerC. S. (2015). Simplifying microbial electrosynthesis reactor design.Front. Microbiol.6:468. 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00468

21

GildemynS.VerbeeckK.SlabbinckR.AndersenS. J.PrévoteauA.RabaeyK. (2015). Integrated production, extraction, and concentration of acetic acid from CO2 through microbial electrosynthesis.Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett.2325–328. 10.1021/acs.estlett.5b00212

22

GravesT.NarendranathN. V.DawsonK.PowerR. (2006). Effect of pH and lactic or acetic acid on ethanol productivity by Saccharomyces cerevisiae in corn mash.J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol.33469–474. 10.1007/s10295-006-0091-6

23

HandlerR. M.ShonnardD. R.GriffingE. M.LaiA.Palou-RiveraI. (2016). Life cycle assessments of ethanol production via gas fermentation: anticipated greenhouse gas emissions for cellulosic and waste gas feedstocks.Ind. Eng. Chem. Res.553253–3261. 10.1021/acs.iecr.5b03215

24

HarnischF.RosaL. F. M.KrackeF.VirdisB.KrömerJ. O. (2014). Electrifying white biotechnology: engineering and economic potential of electricity-driven bio-production.ChemSusChem8758–766. 10.1002/cssc.201402736

25

HuP.ChakrabortyS.KumaraA.WoolstonB.LiuH.EmersonD.et al (2016). Integrated bioprocess for conversion of gaseous substrates to liquids.Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.1133773–3778. 10.1073/pnas.1516867113

26

HuP.Rismani-YazdiH.StephanopoulosG. (2013). Anaerobic CO2 fixation by the acetogenic bacterium Moorella thermoacetica.AIChE J.593176–3183. 10.1002/aic.14127

27

IEA (2016). Decoupling of Global Emissions and Economic growth Confirmed.Paris: International Energy Agency.

28

JourdinL.FreguiaS.DonoseB. C.ChenJ.WallaceG. G.KellerJ.et al (2014). A novel carbon nanotube modified scaffold as an efficient biocathode material for improved microbial electrosynthesis.J. Mater. Chem. A213093–13102. 10.1039/C4TA03101F

29

JourdinL.GriegerT.MonettiJ.FlexerV.FreguiaS.LuY.et al (2015). High acetic acid production rate obtained by microbial electrosynthesis from carbon dioxide.Environ. Sci. Technol.4913566–13574. 10.1021/acs.est.5b03821

30

KantzowC.MayerA.Weuster-BotzD. (2015). Continuous gas fermentation by Acetobacterium woodii in a submerged membrane reactor with full cell retention.J. Biotechnol.21211–15. 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2015.07.020

31

KörnerA.TamC.BennettS.GagnéJ. F. (2015). Technology Roadmap-Hydrogen and Fuel Cells.Paris: International Energy Agency (IEA).

32

KriegT.SydowA.SchröderU.SchraderJ.HoltmannD. (2014). Reactor concepts for bioelectrochemical syntheses and energy conversion.Trends Biotechnol.321–11. 10.1016/j.tibtech.2014.10.004

33

LaBelleE. V.MarshallC. W.GilbertJ. A.MayH. D. (2014). Influence of acidic pH on hydrogen and acetate production by an electrosynthetic microbiome.PLoS ONE9:e109935. 10.1371/journal.pone.0109935

34

LauM. W.BalsB. D.ChundawatS. P. S.JinM.GunawanC.BalanV.et al (2012). An integrated paradigm for cellulosic biorefineries: utilization of lignocellulosic biomass as self-sufficient feedstocks for fuel, food precursors and saccharolytic enzyme production.Energy Environ. Sci.57100–7110. 10.1039/c2ee03596k

35

LawfordH. G.RousseauJ. D. (1997). Corn steep liquor as a cost-effective nutrition adjunct in high-performance Zymomonas ethanol fermentations.Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol.6287–304. 10.1007/BF02920431

36

LoganB. E.RabaeyK. (2012). Conversion of wastes into bioelectricity and chemicals by using microbial electrochemical technologies.Science337686–690. 10.1126/science.1217412

37

LovleyD. R.NevinK. P. (2013). Electrobiocommodities: powering microbial production of fuels and commodity chemicals from carbon dioxide with electricity.Curr. Opin. Biotechnol.241–6. 10.1016/j.copbio.2013.02.012

38

MarshallC.RossD.HandleyK.WeisenhornP.EdirisingheJ. N.HenryC. S.et al (2016). Metabolic reconstruction and modeling microbial electrosynthesis.bioRxiv 059410. 10.1101/059410

39

MarshallC. W.RossD. E.FichotE. B.NormanR. S.MayH. D. (2012). Electrosynthesis of commodity chemicals by an autotrophic microbial community.Appl. Environ. Microbiol.788412–8420. 10.1128/AEM.02401-12

40

MarshallC. W.RossD. E.FichotE. B.NormanR. S.MayH. D. (2013). Long-term operation of microbial electrosynthesis systems improves acetate production by autotrophic microbiomes.Environ. Sci. Technol.476023–6029. 10.1021/es400341b

41

MayH. D.EvansP. J.LaBelleE. V. (2016). The bioelectrosynthesis of acetate.Curr. Opin. Biotechnol.42225–233. 10.1016/j.copbio.2016.09.004

42

NayakJ.PalM.PalP. (2015). Modeling and simulation of direct production of acetic acid from cheese whey in a multi-stage membrane-integrated bioreactor.Biochem. Eng. J.93179–195. 10.1016/j.bej.2014.10.002

43

NayakJ.PalP. (2015). “A green process for acetic acid production,” in Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Chemical, Ecology and Environmental Sciences, Pattaya.

44

NevinK. P.WoodardT. L.FranksA. E.SummersZ. M.LovleyD. R. (2010). Microbial electrosynthesis: feeding microbes electricity to convert carbon dioxide and water to multicarbon extracellular organic compounds.mBio1:e00103–10. 10.1128/mBio.00103-10

45

NiB.-J.LiuH.NieY.-Q.ZengR. J.DuG.-C.ChenJ.et al (2010). Coupling glucose fermentation and homoacetogenesis for elevated acetate production: experimental and mathematical approaches.Biotechnol. Bioeng.108345–353. 10.1002/bit.22908

46

PalP.NayakJ. (2016). Acetic acid production and purification: critical review towards process intensification.Sep. Purif. Rev.4644–61. 10.1080/15422119.2016.1185017

47

PapoutsakisE. T. (2015). Reassessing the progress in the production of advanced biofuels in the current competitive environment and beyond: what are the successes and where progress eludes us and why.Ind. Eng. Chem. Res.5410170–10182. 10.1021/acs.iecr.5b01695

48

PatilS. A.ArendsJ.VanwonterghemI.van MeerbergenJ.GuoK.TysonG.et al (2015). Selective enrichment establishes a stable performing community for microbial electrosynthesis of acetate from CO2.Environ. Sci. Technol.498833–8843. 10.1021/es506149d

49

RaizadaT. (2016). US Acetic Acid Demand Soft in Americas. Available at: http://www.icis.com/resources/news/2016/09/02/10031371/us-acetic-acid-demand-soft-in-the-americas/[accessed November 10, 2016].

50

RichterH.MartinM.AngenentL. T. (2013). A two-stage continuous fermentation system for conversion of syngas into ethanol.Energies63987–4000. 10.3390/en6083987

51

SchröderU.HarnischF.AngenentL. T. (2015). Microbial electrochemistry and technology: terminology and classification.Energy Environ. Sci.8513–519. 10.1039/C4EE03359K

52

SpiritoC. M.RichterH.RabaeyK.StamsA. J.AngenentL. T. (2014). Chain elongation in anaerobic reactor microbiomes to recover resources from waste.Curr. Opin. Biotechnol.27115–122. 10.1016/j.copbio.2014.01.003

53

TremblayP. L.AngenentL. T.ZhangT. (2016). Extracellular electron uptake: among autotrophs and mediated by surfaces.Trends Biotechnol.35360–371. 10.1016/j.tibtech.2016.10.004

54

WakatsukiK. (2015). Acetyls Chain - World Market Overview. Chemicals Committee Meeting at APIC 2015. Available at: http://www.orbichem.com/userfiles/APIC%202015/APIC2015_Keiji_Wakatsuki.pdf[accessed November 10, 2016].

55

WiserR.BolingerM. (2016). 2015 Wind Technologies Market Report.Report No: LBNL-1005951. Germantown, MD: United States Department of Energy.

56

XuJ.GuzmanJ. J. L.AndersenS. J.RabaeyK.AngenentL. T. (2015). In-line and selective phase separation of medium-chain carboxylic acids using membrane electrolysis.Chem. Commun.516847–6850. 10.1039/C5CC01897H

57

YatesM. D.SiegertM.LoganB. E. (2014). Hydrogen evolution catalyzed by viable and non-viable cells on biocathodes.Int. J. Hydrogen Energy3916841–16851. 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2014.08.015

58

ZhangF.DingJ.ZhangY.ChenM.DingZ. W.van LoosdrechtM. C. M.et al (2013). Fatty acids production from hydrogen and carbon dioxide by mixed culture in the membrane biofilm reactor.Water Res.476122–6129. 10.1016/j.watres.2013.07.033

59

ZhangY.AngelidakiI. (2016). Microbial electrochemical systems and technologies: it is time to report the capital costs.Environ. Sci. Technol.505432–5433. 10.1021/acs.est.6b01601

Summary

Keywords

microbial electrosynthesis, acetate, hydrogen, chemicals from CO2, biocathode, industrial biotechnology

Citation

LaBelle EV and May HD (2017) Energy Efficiency and Productivity Enhancement of Microbial Electrosynthesis of Acetate. Front. Microbiol. 8:756. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00756

Received

22 February 2017

Accepted

12 April 2017

Published

03 May 2017

Volume

8 - 2017

Edited by

Feng Zhao, Chinese Academy of Sciences, China

Reviewed by

Ahmed ElMekawy, University of Adelaide, Australia; Seung Gu Shin, Pohang University of Science and Technology, South Korea; G. Velvizhi, Indian Institute of Chemical Technology (Council of Scientific and Industrial Research), India

Updates

Copyright

© 2017 LaBelle and May.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Harold D. May, mayh@musc.edu

This article was submitted to Microbiotechnology, Ecotoxicology and Bioremediation, a section of the journal Frontiers in Microbiology

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.