Abstract

Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) have spread rapidly around the world in the past few years, posing great challenges to human health. The plasmid-mediated horizontal transmission of carbapenem-resistance genes is the main cause of the surge in the prevalence of CRE. Therefore, the timely and accurate detection of CRE, especially carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae, is very important for the clinical prevention and treatment of these infections. A variety of methods for the rapid detection of CRE phenotypes and genotypes have been developed for use in clinical microbiology laboratories. To overcome the lack of efficient antibiotics, CRE infections are often treated with combination therapies. Moreover, novel drugs and emerging strategies appeared successively and in various stages of development. In this article, we summarized the global distribution of various carbapenemases. And we focused on summarizing and comparing the advantages and limitations of the detection methods and the therapeutic strategies of CRE primarily.

Introduction

Carbapenem antibiotics are generally considered the most effective antibacterial agents for the treatment of multidrug-resistant bacterial infections. However, with the widespread use of carbapenem antibiotics, the prevalence of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) has increased rapidly, and has become a serious threat to public health. The production of carbapenemases is the major mechanism underlying carbapenem resistance in CRE throughout the world. Carbapenemases are a kind of β-lactamase that can hydrolyze carbapenem antibiotics. According to the Ambler classification method, carbapenemases can be divided into classes A, B, and D. Class A and class D carbapenemases are serine β-lactamases, and class B carbapenemases are metallo-β-lactamases (MBLs) (Ambler, 1980). There is a large overlap between CRE and carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae (CPE), but the difference is that they were named according to the carbapenem-resistant phenotype and the resistance mechanism (carbapenemase production), respectively. The correct distinction of CRE and CPE and the rapid detection of CPE are important in the treatment and management of clinical infections. This article summarizes the epidemiology of CRE, the detection of CPE, and the status of clinical treatments.

Epidemiological Analysis of CRE

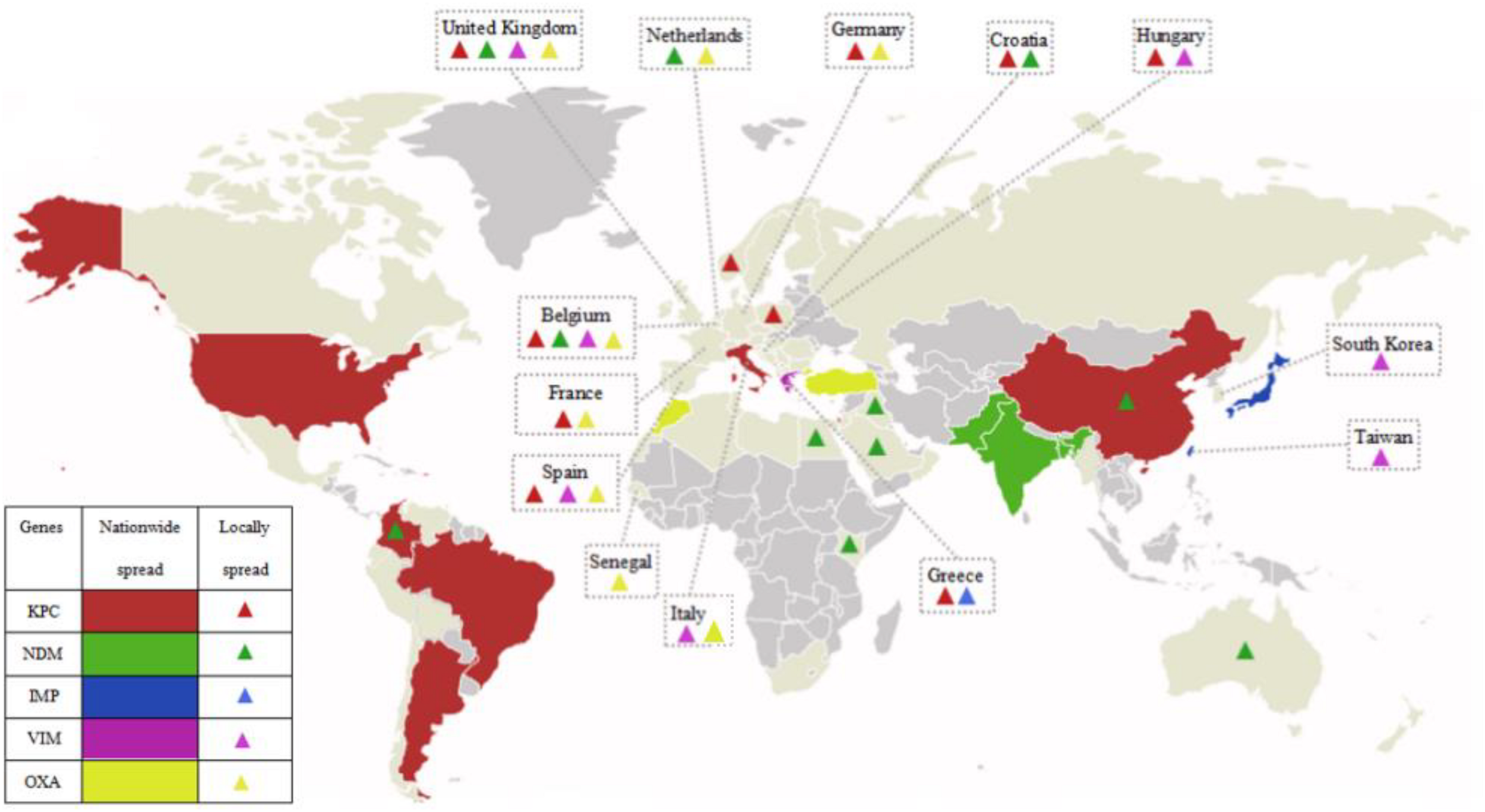

The widespread distribution of CRE is mainly attributable to their production of carbapenemases and the plasmid-mediated horizontal transmission of the encoding genes. The prevalence of CRE and the carbapenemase species involved are highly dependent upon the geographic region.

In 2001, the United States first reported a Klebsiella pneumoniae (KPN) strain carrying a plasmid-mediated carbapenemase gene encoding a protein later designated K. pneumoniae carbapenemase (KPC) (Yigit et al., 2001). From then on, blaKPC have spread widely in the United States and South America. And the outbreaks of KPC-producing Enterobacteriaceae are reported in majority of European regions successively (Munoz-Price et al., 2013; Patel and Bonomo, 2013). In China, the first KPC-producing CRE strain was identified in 2007 (Wei et al., 2007), and since then, blaKPC–2 has become the most widely spread carbapenemase gene (Zhang et al., 2017). KPN was the main clinically isolated CRE producing KPC. Among the KPC-producing KPN, multilocus sequence typing (MLST) of most strains is clonal complex 258 (CC258), which indicated that CC258 obtained a KPC-encoding gene in the early epidemic of CRE and spread rapidly (Bowers et al., 2015). The predominant sequence type (ST) in China is ST11, and ST258 is predominant in the United States while ST340, ST437, and ST512 predominate in other countries (Chen et al., 2014). Therefore, clonal transmission is considered the main mechanism by which KPC-producing KPN is disseminated.

In 2009, blaNDM-associated carbapenem-resistant KPN was first reported in India (Yong et al., 2009). Since then, blaNDM has been detected in most species of Enterobacteriaceae (Tsang et al., 2012; Berrazeg et al., 2014). NDM-type β-lactamase mainly spread in Asia like India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, especially in China (Dortet et al., 2014). In recent years, NDM has become the second commonest carbapenemase found among CRE in China (Zhang Y. et al., 2018), and blaNDM is more prevalent in Escherichia coli (Zhang et al., 2017). Due to the horizontal transfer of epidemic broad-host-range plasmids (Pitout et al., 2015), a high diversity of blaNDM-associated E. coli has been detected, among which ST131, ST167, and ST410 are the dominant types (Zhang et al., 2017). Besides, blaIMP have spread throughout Japan since the IMP-1 was first discovered in Okazaki (Ito et al., 1995). At present, IMP-producing Enterobacteriaceae were found in Japan and Taiwan, China with the highest frequency (Nordmann et al., 2011). In other countries, the outbreaks or reports of blaIMP are sporadic (Bush and Jacoby, 2010; Nordmann et al., 2011; Patel and Bonomo, 2013). As for VIM, Greece is the epicenter of VIM-producing Enterobacteriaceae (Walsh et al., 2005). Certainly, there are significant outbreaks in other parts of Europe such as the United Kingdom, Belgium, Spain, Italy, Hungary, and some Asian regions such as Taiwan, China, and South Korea. Moreover, the sporadic outbreaks of VIM-producing Enterobacteriaceae are globally reported (Walsh et al., 2005; Vatopoulos, 2008; Nordmann et al., 2011; Glasner et al., 2013).

The class D β-lactamases, which function by splitting oxacillin, are designated oxacillinases (OXA). In 1985, the first OXA-encoding gene was found in an Acinetobacter baumannii isolate from the United Kingdom and designated blaOXA–23 (Donald et al., 2000). Since then, a number of OXA family members have gradually been detected in the Enterobacteriaceae, including OXA-23-like, OXA-48-like, OXA-40-like, OXA-51-like, and OXA-58-like (Evans and Amyes, 2014). The commonest class D β-lactamases is OXA-48, which was first identified in a KPN isolate from Turkey in 2001 (Poirel et al., 2004). OXA-48 includes classical OXA-48 and its variants, OXA-181 and OXA-23 (Pitout et al., 2015). CRE producing OXA-48 are mainly concentrated in European countries (France, Germany, Netherlands, Italy, the United Kingdom, and so on), Middle East (Turkey), and Mediterranean countries, including North Africa (mainly Morocco, Tunisia, Egypt, and Libya) (Stewart et al., 2018). Figure 1 has shown the global distribution of CRE that produce various carbapenemases.

FIGURE 1

The global distribution of various carbapenemases in CPE. Carbapenemases have emerged in majority regions all over the world. KPCs are the most common carbapenemases and mainly prevalent in China, the Unite States, Italy, and the majority regions of South America; NDMs are mainly prevalent in China, Pakistan, India, and Bangladesh, and widely spread around the world; IMPs are mainly prevalent in Japan and Taiwan, China; VIMs are mainly prevalent in Greece; OXA mainly refers to OXA-48, and is mainly prevalent in Turkey, Morocco, and European countries (France, Germany, Netherlands, Italy, the United Kingdom, and so on); and various carbapenemases locally spread in Europe.

In the past few years, cases of multiple carbapenemases in the same Enterobacteriaceae isolate have been reported. For example, blaNDM–1 and blaIMP–4 coexisted in KPN (Chen et al., 2015), Enterobacter cloacae or Citrobacter freundii carried both blaKPC and blaNDM (Feng et al., 2015; Du et al., 2016a; Yang et al., 2018). Besides, there was a Klebsiella oxytoca isolate coexpressing three carbapenemases, KPC-2, NDM-1, and IMP-4, which was identified in 2017, and the plasmids containing these three resistance genes have emerged in most other members of the family Enterobacteriaceae, including E. coli, E. cloacae, and Klebsiella species (Wang et al., 2017).

Rapid Detection of Carbapenemases

Initial susceptibility testing like broth microdilution techniques, the Kirby–Bauer disk diffusion method and automatic analysis systems were standardized and simple. But using the screening breakpoints recommended by the CLSI or EUCAST guidelines will miss the inefficient carbapenemases like KPC variants and OXA-48 (Fattouh et al., 2016; Gagetti et al., 2016). Automated systems may cause discrepancies in the detection of all types of carbapenemase producers (Woodford et al., 2010). Therefore, phenotypic assays and molecular-based techniques are the two main methods currently used to detect carbapenemases.

Phenotypic Detection Assays

The modified Hodge test (MHT) is a common phenotypic method for the detection of CPE. It is based on whether the growth of the indicator strain is enhanced at the junction of the inhibition zone and the growth line produced by the indicator strain and the test strain, respectively, and estimates whether the test strain has an inactivation effect on antibacterial drugs (Girlich et al., 2012). The method has high sensitivity and specificity in detecting KPC-producing CRE but poor sensitivity in detecting class B β-lactamases (<50%). However, this limitation can be overcome by the addition of Triton X-100, which was proposed and called the Triton Hodge test. This method increased the sensitivity of the detection of NDM-producing clinical isolates to >90% and improved its performance in detecting other carbapenemases at the same time (Pasteran et al., 2016). But the false-positive and false-negative results will affect clinical judgment (Carvalhaes et al., 2010).

Nordmann et al. (2012) subsequently developed a colorimetric assay, the Carba NP test, which is faster and has lower false-positive rate than MHT. In this test, the change in the pH of the reaction system caused by the carbapenemase hydrolysis of imipenem is monitored as the concomitant change in the color of phenol red, which is judged subjectively by the operator in the laboratory. Moreover, this method could preliminarily identify carbapenemases types based on tazobactam and EDTA (Dortet et al., 2012). And then Pires et al. (2013) replaced phenol red with bromothymol blue as the pH indicator when they developed the Blue-Carba test, which improved the assay sensitivity from 93.3 to 100% (Novais et al., 2015). Bogaerts et al. (2016) proposed an electrochemical method derived from the traditional assay, and designated it the Bogaerts–Yunus–Glupczynski (BYG) Carba test. This test reduces the time required from 2.5 h to about 30 min, and resulting from the real-time curve results, this test offers a real-time objective measurement of carbapenemase-producing isolates (Bogaerts et al., 2016). Various commercialized products are also available, such as Rapidec Carba NP (bioMérieux), Rosco Rapid Carb Screen, and the Rapid Carb Blue Kit. A study suggested that most manual and commercial rapid colorimetric assays are insufficiently sensitive for the detection of OXA-48-type producers (Tamma et al., 2017). In 2018, another study demonstrated that the MBT STAR-Carba kit (Bruker Daltonics), which is based on bicarbonate, displays higher sensitivity in the detection of OXA, but still cannot avoid undetected errors (Rapp et al., 2018).

The carbapenem inactivation method (CIM) is another effective phenotypic test. This method determines the carbapenemase activity of the tested bacteria by measuring the diameter of the inhibition zone of E. coli ATCC 25922 after the carbapenem disk is inactivated by the test bacterium. The results are highly consistent with the presence of carbapenemase genes, including those encoding KPC, NDM, VIM, IMP, OXA-48, and OXA-23, detected with polymerase chain reaction (PCR) (100% agreement for Enterobacteriaceae) (van der Zwaluw et al., 2015). The modified CIM (mCIM) became the CLSI-recommended method in 2017. A study indicated that both the sensitivity and specificity of mCIM were 100% (Kuchibiro et al., 2018). Because of its simplicity, clear criteria, cost-effectiveness, and availability in any laboratory, the mCIM has become a useful tool in microbiology laboratories.

Many tests that rely on directly monitoring the hydrolysis of β-lactamases to detect CPE have been reported, including a spectrophotometric method (Bernabeu et al., 2012), which is regarded as a reliable detection assay. But extracting the carbapenemases from the bacterial cells is time-consuming, and there were various factors reducing the veracity of the results. To overcome these limitations, Takeuchi et al. (2018) developed a dual-wavelength measurement which could measure the hydrolytic activity of carbapenemases using bacterial cells directly. On the one hand, this method is time saving (about 40 min for preparation and incubation, but the time of detecting OXA should be prolonged appropriately). On the other hand, this method showed higher sensitivity and specificity than carbaNP at the same incubation time, and obtained consistent results upon mCIM. However, the requirement for a specific instrument (spectrophotometer) and the small sample size limit its clinical application (Takeuchi et al., 2018).

In 2011, Hrabák et al. (2011) proposed that matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI–TOF MS) could be used to screen CPE by detecting the by-products of the hydrolyzed carbapenem. Since then, other groups have developed various MALDI–TOF-based methods to improve the sensitivity of the procedure, reduce the detection time, and facilitate the interpretation of the results (Johansson et al., 2014; Knox et al., 2014; Sauget et al., 2014; Lasserre et al., 2015; Papagiannitsis et al., 2015). For example, aiming at the low sensitivity mainly resulting from the false-negative results obtained with OXA-48-type producers, Papagiannitsis et al. (2015) added NH4HCO3 to the reaction buffer, which improved its sensitivity from 76 to 98%. To save time, Lasserre et al. (2015) developed a MALDI–TOF-based method that directly detects resistant Enterobacteriaceae from primary culture plates in <30 min and ensures high sensitivity and specificity. In 2018, a survey demonstrated that a MALDI–TOF-MS-based ertapenem hydrolysis assay rapidly and accurately detected the carbapenemase activity of Enterobacteriaceae strains in positive blood cultures (Yu et al., 2018a). Although the costs of measurement using MALDI–TOF MS are low, the equipment remains expensive, which limits the wide application of this method in clinic (Lasserre et al., 2015).

As well as all these methods, carbapenemase-inhibitor-based disc tests have been shown to detect carbapenemases (Tsakris et al., 2010). For example, combining boronic acid with an ertapenem or meropenem disk has been applied in detecting production of KPC (Doi et al., 2008). Adding ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid to a carbapenem disk makes it a useful compound in detecting MBLs (Franklin et al., 2006). Ote et al. developed an immunochromatographic assay to directly detect OXA-48-like carbapenemase using a monoclonal antibody, and the results were obtained in a very short time (Glupczynski et al., 2016). A bioluminescence-based carbapenem susceptibility detection assay was reported in 2018 that allows carbapenemase-producing CRE and non-carbapenemase-producing CRE to be distinguished with a sensitivity of 99% and a specificity of 98% (Van Almsick et al., 2018).

Molecular-Based Detection Methods

Tests based on molecular techniques are considered the gold standards for the identification of carbapenemase genes (Nordmann et al., 2011), the advantages and limitations have been summarized in Table 1. PCR is the most commonly used traditional molecular genotyping method. However, the traditional PCR method for identifying a single gene is time-consuming. Therefore, multiple PCR that was time-saving with high levels of sensitivity and specificity (Ellington et al., 2016) was proposed and developed. From 2006 to 2012, the multiplex real-time PCR systems have been initially established for the rapid detection of most carbapenemases like KPC, OXA-48 (Swayne et al., 2011), VIM, IMP (Mendes et al., 2006), and NDM (Monteiro et al., 2012). Furthermore, various modified methods were proposed to overcome the inaccuracy caused by the diversity of OXA-48-like carbapenemases (Hemarajata et al., 2015), such as a real-time PCR assay based on a high-resolution melt analysis (Hemarajata et al., 2015), and a multiplex PCR assay using peptide–nucleic acid probes, which could identify resistance genes in a mixture of Enterobacteriaceae isolates with highly efficient (Jeong et al., 2015).

TABLE 1

| Detection methods | Advantages | Limitations |

| Phenotypic detection assays | ||

| Modified Hodge test (MHT) |

|

|

| Colorimetric assay |

|

|

| Modified carbapenem inactivation method (mCIM) |

|

|

| Spectrophotometric method |

|

|

| MALDI–TOF-based methods |

|

|

| Molecular-based detection methods |

|

|

The advantages and limitations of common detection methods.

As well as the methods described above, several other molecular methods are used to detect CPE. For example, Walker et al. (2016) combined nested PCR, real-time PCR, and microfluidics to identify the common carbapenemases genes. A PCR-based method in a cartridge format developed to detect CPE in rectal swabs, which is run on the GeneXpert platform, displayed high sensitivity (96.6%) and specificity (98.6%) within a short time (32–48 min) (Tato et al., 2016). Srisrattakarn et al. (2017) developed a loop-mediated isothermal amplification method with hydroxynaphthol blue dye (LAMP-HNB), which was highly efficient (100% sensitivity and specificity). In 2018, the microfluidic chip technology which allows the rapid detection of pathogens and their resistance genes (Kim et al., 2017) was used to detect carbapenem-resistance genes, with high sensitivity and specificity (both >90.0%), and fully met the requirements for clinical diagnoses (Zhang G. et al., 2018). Verigene Gram-negative blood culture assay, the microarray-based commercialized products, was available to identify the carbapenemases (Ledeboer et al., 2015). But the materials cost is a little bit expensive approximately $60–80 per test (Hill et al., 2014). In addition, whole genome sequencing is the most reliable method for the detection of carbapenemase genes, but the high cost, long turnaround time, and difficult data management limit the routine clinical application of this method (Patel, 2016). Yu et al. (2018b) also developed a novel multiplex PCR amplification reaction to directly and rapidly identify the epidemic CRKP ST258/ST11 strain. The advantages and limitations of common detection methods have been shown in Table 1.

Treatment of CRE Infections

To the bests of our knowledge, almost all β-lactam antibiotics have limited effects on the treatment of CRE infections, and carbapenemases cannot be inhibited by traditional β-lactamase inhibitors (Zhang et al., 2017). Some restricted drugs, such as polymyxins, tigecycline, and fosfomycin, may be active. A proportion of CRE strains producing KPC and OXA-48 are also sensitive to aminoglycosides (gentamicin and amikacin). However, there are significant deficiencies in the use of monotherapy to treat CRE infections with these antibiotics. Polymyxin has significant nephrotoxicity and neurotoxicity (van Duin et al., 2013), and the optimal dose for treatment is unknown. This antibiotic has also been challenged by the emergence and global spread of mobilized colistin resistance (mcr) determinants. The presence of both mcr-1 and various blaNDM has been reported in Enterobacteriaceae isolates (Du et al., 2016b; Yao et al., 2016; Zheng et al., 2017; Li et al., 2018). The increased mortality risk conferred by tigecycline (Cai et al., 2010; Shen et al., 2015; Ni et al., 2016) has led to warnings by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA, 2013). Furthermore, reports of clinical tigecycline resistance were published soon after its first use in medical practice. The resistance mechanisms that have been reported including mutations in tet (Linkevicius et al., 2016; He et al., 2019) and the increased expression of RND efflux pumps (Nicoloff and Andersson, 2013; Fang et al., 2016). Besides, tigecycline tends to inducing resistance during therapy (Spanu et al., 2012; van Duin et al., 2014; Du et al., 2018). The therapeutic effects of aminoglycosides in CRE infections can be affected by rmtB which confers high-level and widespread resistance (Cheng et al., 2016). The efficacy of fosfomycin is limited and resistance to this drug develops rapidly during treatment (Karageorgopoulos et al., 2012). Moreover, fosfomycin-modified genes play the key role in fosfomycin resistance. It is noteworthy that a carbapenem-, colistin-, and tigecycline-resistant E. coli strain carrying the fosA3 was reported in China in 2018 (Wang et al., 2018), which poses a great threat to public health.

For the reasons described above, several methods have been proposed to enhance the efficacies of these antibiotics, including aerosolized antibiotics for treatment with colistin (Valachis et al., 2015) and higher maintenance doses of colistin and tigecycline (Falagas et al., 2014; Trifi et al., 2016). These regimens did improve the therapeutic effects, but convincing evidence is sparse. In this context, combination therapies have been recommended to treat multidrug-resistant CRE infections. Not only the retrospective studies but also the in vitro tests and clinical applications have proved that the combination therapies were effective for the treatment of CRE (Cprek and Gallagher, 2015; Oliva et al., 2015; Ku et al., 2017). And the mortality rates associated with combination therapies especially the carbapenem-containing combinations were lower than those associated with monotherapy (Mataseje et al., 2016). By combining previous researches on combination therapies (Entenza and Moreillon, 2009; Tzouvelekis et al., 2012; Falagas et al., 2014; Pontikis et al., 2014; Chinese XDR Consensus Working Group et al., 2016), several regimens were proposed in Table 2. However, the mechanistic basis of the synergy has not yet been established for most commonly used combination therapies (Baym et al., 2016).

TABLE 2

| Combination therapies | Advantages | Limitations | Mechanisms of resistance | |

| Tigecycline-based combinations |

|

|

|

|

| Polymyxin-based combinations |

|

|

||

| Other combinations |

|

|

The advantages and limitations of the combination therapies.

a Aminoglycosides refer to amikacin and isepamicin. bCarbapenems refer to meropenem and imipenem.

As well as the antibiotic combination treatments, novel β-lactamase inhibitors and antimicrobial therapeutics were developed to treat CRE infections and eliminate colonization. Avibactam (AVI) is a novel β-lactamase inhibitor that inhibits KPC, ESBL, AmpC, and OXA-48 (van Duin and Bonomo, 2016). Ceftazidime–AVI (CAZ–AVI) has been used in clinical treatments in the United States since 2015 and was recommended by CLSI in 2018. These combination is effective not only for strains producing KPC and OXA-48 (Castanheira et al., 2015), but also for hypervirulent KPN carrying blaKPC–2 (Yu et al., 2018c). CAZ-AVI combined with ertapenem also successfully treated a patient infected with NDM-producing KPN (Camargo et al., 2015). And clinical reports indicated that CAZ-AVI showed commendable therapeutic effect in treating complicated urinary tract or intra-abdominal infections (Tuon et al., 2018). Comparing with colistin, CAZ-AVI showed better efficacy, lower mortality, and fewer side effects in treating KPC-producing CRE (van Duin et al., 2018). However, CAZ–AVI-resistant isolates have been reported since 2015 (Humphries et al., 2015; Shields et al., 2017). To broaden the antibacterial spectrum, aztreonam–AVI was proposed, and effectively inhibited a variety of class A, B, and D carbapenemases (Vasoo et al., 2015). Another two novel carbapenem-β-lactamase inhibitor combinations, imipenem–relebactam and meropenem–vaborbactam, were developed to treat CPE infections. And the latter has been recommend by FDA1. In vitro data have indicated that the two combinations are highly active against KPC-producing Enterobacteriaceae but poorly susceptive against MBLs and OXA-type carbapenemases (Lapuebla et al., 2015a, b). And exact efficacy and safety must be defined with further clinical data (Zhanel et al., 2018). Besides, meropenem–nacubactam during clinical development have shown promising in vitro activity against KPC and MBL-producing CRE (Barnes et al., 2019; Mushtaq et al., 2019). Moreover, cefepime–zidebactam could inhibit CRE producing carbapenemases of classes A, B, and D (Thomson et al., 2019), other cefepime-β-lactam enhancer such as cefepime–enmetazobactam (AAI101)/WCK-5153, etc. which were in earlier stages of development may represent a novel carbapenem-sparing option (Giacobbe et al., 2018; Moya et al., 2019; Papp-Wallace et al., 2019). Several other new drugs such as plazomicin, eravacycline, and cefiderocol developed to treat CRE infections are in various stages of development (Kohira et al., 2016; Thaden et al., 2017; Rodríguez-Baño et al., 2018), among which plazomicin performed more potent effect and lower side effects than other aminoglycosides (Livermore et al., 2011; Riddle et al., 2012; Walkty et al., 2014; Castanheira et al., 2018) and eravacycline showed favorable clinical response and had well pharmacokinetics, tolerability, and in vitro activity (Zhanel et al., 2016; Thaden et al., 2017). The application of cefiderocol needs further clinical data. In 2018, the injection products of plazomicin and eravacycline have been recommend by FDA2. However, due to the emergence of resistant isolates (Livermore et al., 2011; Castanheira et al., 2018; He et al., 2019), enough attention should be paid to the development of drug resistance. The advantages, limitations, and mechanisms of resistance of novel antimicrobial therapeutics have been shown in Table 3.

TABLE 3

| Antimicrobial therapeutics | Advantages | Limitations | Mechanisms of resistance |

| Ceftazidime–avibactam |

|

|

|

| Aztreonam–avibactam |

|

|

|

| Imipenem–relebactam |

|

|

|

| Meropenem–vaborbactam |

|

|

|

| Plazomicin |

|

|

|

| Eravacycline |

|

|

|

| Cefiderocol |

|

|

The advantages and limitations of novel antimicrobial therapeutics.

As well as novel drugs, various strategies for the management of carbapenem resistance have recently emerged. For example, based on studies of fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) and enteric pathogens (Wang et al., 2014; Caballero et al., 2015), FMT was hypothetically suggested to be used as a clearance method for CRE colonized patients, but the feasibility requires further study (Wang et al., 2016; Qazi et al., 2017). Based on research into the mechanisms of antibiotic cytotoxicity (Cheng et al., 2014; Citorik et al., 2014; Dwyer et al., 2014), novel synthetic tools developed for the precise removal of genomic islands have been proposed to replace antibiotic treatments (Vercoe et al., 2013). Immunological-based therapies, such as monoclonal antibodies targeting poly-(-1,6)-N-acetyl glucosamine (Skurnik et al., 2016) and cationic antimicrobial peptides (Pan et al., 2015), are also under investigation as substitutes for traditional antibiotics (DiGiandomenico and Sellman, 2015). The ability of predatory bacteria to reduce the primary pathogen in mammalian system has been demonstrated, which suggested the application prospect in clinic (Shatzkes et al., 2016). The advantages and limitations of these main novel strategies have been summarized in Table 4.

TABLE 4

| Strategies | Advantages | Limitations |

| FMT |

|

|

| Novel synthetic tools | Favorable treatment effect | High technical requirements |

| Immunological-based therapies |

|

|

| Predatory bacteria |

|

|

The advantages and limitations of the novel strategies.

Summary

In recent decades, CRE have spread widely in various medical institutions around the world, and due to the time-consuming detection methods and limited treatment regimens, the mortality rates among patients are high. Therefore, the timely and accurate detection of CRE, especially CPE, is essential for the clinical treatment and prevention of infections. A variety of phenotypic methods and gene-based methods are available for the rapid detection of carbapenemases, and these are expected to be used routinely in clinical microbiology laboratories. At present, novel antibacterial drugs and emerging strategies which have been recommend or during development, with good activity and safety profiles, are expected to be applied to the clinical treatment of these infections in the near future.

Statements

Author contributions

HD designed the study. XC and HZ performed data analysis and prepared the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Six Talent Peaks Project in Jiangsu Province (2016-WSN-112); the Key Research and Development Project of Jiangsu Provincial Science and Technology Department (BE2017654); Gusu Key Health Talent of Suzhou; the Jiangsu Youth Medical Talents Program (QN-866, 867); the Science and Technology Program of Suzhou (SZS201715).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

1.^ https://www.fda.gov/drugs/development-resources/meropenem-and-vaborbactam-injection

2.^ https://www.fda.gov/drugs/development-resources/notice-updates

References

1

Ambler R. P. (1980). The structure of beta-lactamases.Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci.289321–331.

2

Barnes M. D. Taracila M. A. Good C. E. Bajaksouzian S. Rojas L. J. van Duin D. et al (2019). Nacubactam enhances meropenem activity against carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae producing Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemases (KPC).Antimicrob. Agents Chemother.10.1128/AAC.00432-19[Epub ahead of print].

3

Baym M. Stone L. K. Kishony R. (2016). Multidrug evolutionary strategies to reverse antibiotic resistance.Science351:aad3292. 10.1126/science.aad3292

4

Bernabeu S. Poirel L. Nordmann P. (2012). Spectrophotometry-based detection of carbapenemase producers among Enterobacteriaceae.Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis.7488–90. 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2012.05.021

5

Berrazeg M. Diene S. Medjahed L. Parola P. Drissi M. Raoult D. et al (2014). New Delhi Metallo-beta-lactamase around the world:an eReview using Google Maps.Euro Surveill.19:20809. 10.2807/1560-7917.es2014.19.20.20809

6

Bogaerts P. Yunus S. Massart M. Huang T. D. Glupczynski Y. (2016). Evaluation of the BYG carba test, a new electrochemical assay for rapid laboratory detection of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae.J. Clin. Microbiol.54349–358. 10.1128/JCM.02404-15

7

Bowers J. R. Kitchel B. Driebe E. M. MacCannell D. R. Roe C. Lemmer D. et al (2015). Genomic analysis of the emergence and rapid global dissemination of the clonal group 258 Klebsiella pneumoniae pandemic.PLoS One10:e0133727. 10.1371/journal.pone.0133727

8

Bush K. Jacoby G. A. (2010). Updated functional classification of beta-lactamases.Antimicrob. Agents Chemother.54969–976. 10.1128/AAC.01009-09

9

Caballero S. Carter R. Ke X. Susac B. Leiner I. M. Kim G. J. et al (2015). Distinct but spatially overlapping intestinal niches for vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium and carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae.PLoS Pathog.11:e1005132. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005132

10

Cai Y. Wang R. Liang B. Bai N. Liu Y. (2010). Systematic review and meta-analysis of the effectiveness and safety of tigecycline for treatment of infectious disease.Antimicrob. Agents Chemother.551162–1172. 10.1128/AAC.01402-10

11

Camargo J. F. Simkins J. Beduschi T. Tekin A. Aragon L. Perez-Cardona A. et al (2015). Successful treatment of carbapenemase-producing pandrugresistant Klebsiella pneumoniae bacteremia.Antimicrob. Agents Chemother.595903–5908. 10.1128/aac.00655-15

12

Carvalhaes C. G. Picão R. C. Nicoletti A. G. Xavier D. E. Gales A. C. (2010). Cloverleaf test (modified Hodge test) for detecting carbapenemase production in Klebsiella pneumoniae: be aware of false positive results.J. Antimicrob. Chemother.65249–251. 10.1093/jac/dkp431

13

Castanheira M. Deshpande L. M. Woosley L. N. Serio A. W. Krause K. M. Flamm R. K. (2018). Activity of plazomicin compared with other aminoglycosides against isolates from European and adjacent countries, including Enterobacteriaceae molecularly characterized for aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes and other resistance mechanisms.J. Antimicrob. Chemother.733346–3354. 10.1093/jac/dky344

14

Castanheira M. Mills J. C. Costello S. E. Jones R. N. Sader H. S. (2015). Ceftazidimeavibactam activity tested against Enterobacteriaceae isolates from U.S. hospitals(2011 to 2013) and characterization of beta-lactamase-producing strains.Antimicrob. Agents Chemother.593509–3517. 10.1128/AAC.00163-15

15

Chen L. Mathema B. Chavda K. D. DeLeo F. R. Bonomo R. A. Kreiswirth B. N. (2014). Carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae: molecular and genetic decoding.Trends Microbiol.22686–696. 10.1016/j.tim.2014.09.003

16

Chen Z. Wang Y. Tian L. Zhu X. Li L. Zhang B. et al (2015). First report in China of Enterobacteriaceae clinical isolates coharboring blaNDM-1 and blaIMP-4 drug resistance genes.Microb. Drug Resist.21167–170. 10.1089/mdr.2014.0087

17

Cheng A. A. Ding H. Lu T. K. (2014). Enhanced killing of antibiotic-resistant bacteria enabled by massively parallel combinatorial genetics.Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.11112462–12467. 10.1073/pnas.1400093111

18

Cheng L. Cao X. L. Zhang Z. F. Ning M. Z. Xu X. J. Zhou W. et al (2016). Clonal dissemination of KPC-2 producing Klebsiella pneumoniae ST11 clone with high prevalence of oqxAB and rmtB in a tertiary hospital in China: results from a 3-year period.Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob.15:1. 10.1186/s12941-015-0109-x

19

Chinese XDR Consensus Working Group Guan X. He L. Hu B. Hu J. Huang X. et al (2016). Laboratory diagnosis, clinical management and infection control of the infections caused by extensively drug-resistant gram-negative bacilli: a Chinese consensus statement.Clin. Microbiol. Infect.22(Suppl.1), S15–S25. 10.1016/j.cmi.2015.11.004

20

Citorik R. J. Mimee M. Lu T. K. (2014). Sequence-specific antimicrobials using efficiently delivered RNA-guided nucleases.Nat. Biotechnol.321141–1145. 10.1038/nbt.3011

21

Cprek J. B. Gallagher J. C. (2015). Ertapenem-Containing double-carbapenem therapy for treatment of infections caused by carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae.Antimicrob. Agents Chemother.60669–673. 10.1128/AAC.01569-15

22

DiGiandomenico A. Sellman B. R. (2015). Antibacterial monoclonal antibodies: the next generation?Curr. Opin. Microbiol.2778–85. 10.1016/j.mib.2015.07.014

23

Doi Y. Potoski B. A. Adams-Haduch J. M. Sidjabat H. E. Pasculle A. W. Paterson D. L. (2008). Simple diskbased method for detection of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase-type β-lactamase by use of a boronic acid compound.J. Clin. Microbiol.464083–4086. 10.1128/JCM.01408-08

24

Donald H. M. Scaife W. Amyes S. G. Young H. K. (2000). Sequence analysis of ARI-1, a novel OXA beta-lactamase, responsible for imipenem resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii 6B92.Antimicrob. Agents Chemother.44196–199. 10.1128/aac.44.1.196-199.2000

25

Dortet L. Poirel L. Nordmann P. (2012). Rapid identification of carbapenemase types in Enterobacteriaceae and Pseudomonas spp. by using a biochemical test.Antimicrob. Agents Chemother.566437–6440. 10.1128/AAC.01395-12

26

Dortet L. Poirel L. Nordmann P. (2014). Worldwide dissemination of the NDM-type carbapenemases in Gram-negative bacteria.Biomed. Res. Int.2014:249856. 10.1155/2014/249856

27

Du H. Chen L. Chavda K. D. Pandey R. Zhang H. Xie X. et al (2016a). Genomic characterization of Enterobacter cloacae isolates from china that coproduce KPC-3 and NDM-1 carbapenemases.Antimicrob. Agents Chemother.602519–2523. 10.1128/AAC.03053-15

28

Du H. Chen L. Tang Y. W. Kreiswirth B. N. (2016b). Emergence of the mcr-1 colistin resistance gene in carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae.Lancet Infect. Dis.16287–288. 10.1016/s1473-3099(16)00056-6

29

Du X. He F. Shi Q. Zhao F. Xu J. Fu Y. et al (2018). The rapid emergence of tigecycline resistance in blaKPC-2 harboring Klebsiella pneumoniae, as mediated in vivo by mutation in teta during tigecycline treatment.Front. Microbiol.9:648. 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00648

30

Dwidar M. Monnappa A. K. Mitchell R. J. (2012). The dual probiotic and antibiotic nature of Bdellovibrio bacteriovorus.BMB Rep.4571–78. 10.5483/BMBRep.2012.45.2.71

31

Dwyer D. J. Belenky P. A. Yang J. H. MacDonald I. C. Martell J. D. Takahashi N. et al (2014). Antibiotics induce redox-related physiological alterations as part of their lethality.Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.111E2100–E2109. 10.1073/pnas.1401876111

32

Ellington M. J. Findlay J. Hopkins K. L. Meunier D. Alvarez-Buylla A. Horner C. et al (2016). Multicentre evaluation of a real-time PCR assay to detect genes encoding clinically relevant carbapenemases in cultured bacteria.Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents47151–154. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2015.11.013

33

Entenza J. M. Moreillon P. (2009). Tigecycline in combination with other antimicrobials: a review of in vitro, animal and case report studies.Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents341–9. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2008.11.006

34

Evans B. A. Amyes S. G. (2014). OXA β-lactamases.Clin. Microbiol. Rev.27241–263. 10.1128/CMR.00117-13

35

Falagas M. E. Vardakas K. Z. Tsiveriotis K. P. Triarides N. A. Tansarli G. S. (2014). Effectiveness and safety of high-dose tigecycline-containing regimens for the treatment of severe bacterial infections.Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents441–7. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2014.01.006

36

Fang L. Chen Q. Shi K. Li X. Shi Q. He F. et al (2016). Step-Wise increase in tigecycline resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae associated with mutations in ramR, lon and rpsJ.PLoS One11:e0165019. 10.1371/journal.pone.0165019

37

Fattouh R. Tijet N. McGeer A. Poutanen S. M. Melano R. G. Patel S. N. (2016). What is the appropriate meropenem MIC for screening of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in low-prevalence settings?Antimicrob. Agents Chemother.601556–1559. 10.1128/AAC.02304-15

38

FDA (2013). Drug safety Announcement–Tigecycline.Rockville, MD: FDA.

39

Feng J. Qiu Y. Yin Z. Chen W. Yang H. Yang W. et al (2015). Coexistence of a novel KPC-2-encoding MDR plasmid and an NDM-1-encoding pNDM-HN380-like plasmid in a clinical isolate of Citrobacter freundii.J. Antimicrob. Chemother.702987–2991. 10.1093/jac/dkv232

40

Franklin C. Liolios L. Peleg A. Y. (2006). Phenotypic detection of carbapenem-susceptible metallo-βlactamase-producing gram-negative bacilli in the clinical laboratory.J. Clin. Microbiol.443139–3144. 10.1128/jcm.00879-06

41

Gagetti P. Pasteran F. Martinez M. P. Fatouraei M. Gu J. Fernandez R. et al (2016). Modeling meropenem treatment, alone and in combination with daptomycin, for KPC-Producing Klebsiella pneumoniae strains with unusually low carbapenem MICs.Antimicrob. Agents Chemother.605047–5050. 10.1128/AAC.00168-16

42

Giacobbe D. R. Mikulska M. Viscoli C. (2018). Recent advances in the pharmacological management of infections due to multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria.Expert Rev. Clin. Pharmacol.111219–1236. 10.1080/17512433.2018.1549487

43

Giamarellou H. Poulakou G. (2011). Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic evaluation of tigecycline.Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol.71459–1470. 10.1517/17425255.2011.623126

44

Girlich D. Poirel L. Nordmann P. (2012). Value of the modified Hodge test for detection of emerging carbapenemases in Enterobacteriaceae.J. Clin. Microbiol.50477–479. 10.1128/JCM.05247-11

45

Glasner C. Albiger B. Buist G. Tambić Andrasević A. Canton R. Carmeli Y. et al (2013). Carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in Europe: a survey among national experts from 39 countries, February 2013.Euro Surveill.18:20525.

46

Glupczynski Y. Evrard S. Ote I. Mertens P. Huang T. D. Leclipteux T. et al (2016). Evaluation of two new commercial immunochromatographic assays for the rapid detection of OXA-48 and KPC carbapenemases from cultured bacteria.J. Antimicrob. Chemother.711217–1222. 10.1093/jac/dkv472

47

He T. Wang R. Liu D. Walsh T. R. Zhang R. Lv Y. et al (2019). Emergence of plasmid-mediated high-level tigecycline resistance genes in animals and humans.Nat. Microbiol.10.1038/s41564-019-0445-2[Epub ahead of print].

48

Heaney M. Mahoney M. V. Gallagher J. C. (2019). Eravacycline: the tetracyclines strike back.Ann. Pharmacother.10.1177/1060028019850173[Epub ahead of print].

49

Hecker S. J. Reddy K. R. Totrov M. Hirst G. C. Lomovskaya O. Griffith D. C. et al (2015). Discovery of a cyclic boronic acid b-Lactamase inhibitor (RPX7009) with Utility vs Class A Serine Carbapenemases.J. Med. Chem.583682–3692. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b00127

50

Hemarajata P. Yang S. Hindler J. A. Humphries R. M. (2015). Development of a novel real-time PCR assay with high-resolution melt analysis to detect and differentiate OXA-48-Like β-lactamases in carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae.Antimicrob. Agents Chemother.595574–5580. 10.1128/aac.00425-15

51

Hill J. T. Tran K. D. Barton K. L. Labreche M. J. Sharp S. E. (2014). Evaluation of the nanosphere Verigene BCGN assay for direct identification of gram-negative bacilli and antibiotic resistance markers from positive blood cultures and potential impact for more-rapid antibiotic interventions.J. Clin. Microbiol.523805–3807. 10.1128/JCM.01537-14

52

Hrabák J. Walková R. Studentová V. Chudácková E. Bergerová T. (2011). Carbapenemase activity detection by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry.J. Clin. Microbiol.493222–3227. 10.1128/JCM.00984-11

53

Humphries R. M. Yang S. Hemarajata P. Ward K. W. Hindler J. A. Miller S. A. et al (2015). First report of ceftazidime-avibactam resistance in a KPC-3-expressing Klebsiella pneumoniae isolate.Antimicrob. Agents Chemother.596605–6607. 10.1128/AAC.01165-15

54

Ito H. Arakawa Y. Ohsuka S. Wacharotayankun R. Kato N. Ohta M. (1995). Plasmid-mediated dissemination of the metallo-beta-lactamase gene blaIMP among clinically isolated strains of Serratia marcescens.Antimicrob. Agents Chemother.39824–829. 10.1128/aac.39.4.824

55

Jeong S. Kim J. O. Jeong S. H. Bae I. K. Song W. (2015). Evaluation of peptide nucleic acid-mediated multiplex real-time PCR kits for rapid detection of carbapenemase genes in gram-negative clinical isolates.J. Microbiol. Methods1134–9. 10.1016/j.mimet.2015.03.019

56

Johansson Å. Nagy E. Sóki J. (2014). Instant screening and verification of carbapenemase activity in Bacteroides fragilis in positive blood culture, using matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight mass spectrometry.J. Med. Microbiol.631105–1110. 10.1099/jmm.0.075465-0

57

Karageorgopoulos D. E. Wang R. Yu X. H. Falagas M. E. (2012). Fosfomycin: evaluation of the published evidence on the emergence of anti-microbial resistance in Gram-negative pathogens.J. Anti Microb. Chemother.67255–268. 10.1093/jac/dkr466

58

Kim S. De Jonghe J. Kulesa A. B. Feldman D. Vatanen T. Bhattacharyya R. P. et al (2017). High-throughput automated microfluidic sample preparation for accurate microbial genomics.Nat. Commun.8:13919. 10.1038/ncomms13919

59

Knox J. Jadhav S. Sevior D. Agyekum A. Whipp M. Waring L. et al (2014). Phenotypic detection of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae by use of matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry and the Carba NP test.J. Clin. Microbiol.524075–4077. 10.1128/JCM.02121-14

60

Kohira N. West J. Ito A. Ito-Horiyama T. Nakamura R. Sato T. et al (2016). In Vitro antimicrobial activity of a siderophore cephalosporin, S-649266, against Enterobacteriaceae clinical isolates, including carbapenem-resistant strains.Antimicrob. Agents Chemother.60729–734. 10.1128/AAC.01695-15

61

Ku Y. H. Chen C. C. Lee M. F. Chuang Y. C. Tang H. J. Yu W. L. (2017). Comparison of synergism between colistin, fosfomycin and tigecycline against extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates or with carbapenem resistance.J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect.50931–939. 10.1016/j.jmii.2016.12.008

62

Kuchibiro T. Komatsu M. Yamasaki K. Nakamura T. Nishio H. Nishi I. et al (2018). Evaluation of the modified carbapenem inactivation method for the detection of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae.J. Infect. Chemother.24262–266. 10.1016/j.jiac.2017.11.010

63

Lan S. H. Chang S. P. Lai C. C. Lu L. C. Chao C. M. (2019). The efficacy and safety of eravacycline in the treatment of complicated intra-abdominal infections: a systemic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials.J. Clin. Med.8:866. 10.3390/jcm8060866

64

Lapuebla A. Abdallah M. Olafisoye O. Cortes C. Urban C. Landman D. et al (2015a). Activity of imipenem with relebactam against gram-negative pathogens from New York City.Antimicrob. Agents Chemother.595029–5031. 10.1128/AAC.00830-15

65

Lapuebla A. Abdallah M. Olafisoye O. Cortes C. Urban C. Quale J. et al (2015b). Activity of meropenem combined with RPX7009, a Novel b-Lactamase inhibitor, against gram-negative clinical isolates in New York City.Antimicrob. Agents Chemother.594856–4860. 10.1128/aac.00843-15

66

Lasserre C. De Saint Martin L. Cuzon G. Bogaerts P. Lamar E. Glupczynski Y. et al (2015). Efficient detection of carbapenemase activity in Enterobacteriaceae by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry in Less Than 30 Minutes.J. Clin. Microbiol.532163–2171. 10.1128/JCM.03467-14

67

Ledeboer N. A. Lopansri B. K. Dhiman N. Cavagnolo R. Carroll K. C. Granato P. et al (2015). Identification of gram-negative bacteria and genetic resistance determinants from positive blood culture broths by use of the Verigene Gram-negative blood culture multiplex microarray-based molecular assay.J. Clin. Microbiol.532460–2472. 10.1128/JCM.00581-15

68

Lee Y. R. Burton C. E. (2019). Eravacycline, a newly approved fluorocycline.Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis.10.1007/s10096-019-03590-3[Epub ahead of print].

69

Li X. Mu X. Zhang P. Zhao D. Ji J. Quan J. et al (2018). Detection and characterization of a clinical Escherichia coli ST3204 strain coproducing NDM-16 and MCR-1.Infect. Drug Resist.111189–1195. 10.2147/IDR.S175041

70

Linkevicius M. Sandegren L. Andersson D. I. (2016). Potential of tetracycline resistance proteins to evolve tigecycline resistance.Antimicrob. Agents Chemother.60789–796. 10.1128/AAC.02465-15

71

Livermore D. M. Mushtaq S. Warner M. Woodford N. (2016). Invitro activity of eravacycline against carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae and Acinetobacter baumannii.Antimicrob. Agents Chemother.603840–3844. 10.1128/aac.00436-16

72

Livermore D. M. Mushtaq S. Warner M. Zhang J. C. Maharjan S. Doumith M. et al (2011). Activity of aminoglycosides, including ACHN-490, against carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae isolates.J. Antimicrob. Chemother.6648–53. 10.1093/jac/dkq408

73

Lob S. H. Hackel M. A. Kazmierczak K. M. Young K. Motyl M. R. Karlowsky J. A. et al (2017). In Vitro activity of imipenem-relebactam against gram-negative ESKAPE pathogens isolated by clinical laboratories in the United States in 2015 (Results from the SMART Global Surveillance Program).Antimicrob. Agents Chemother.61:e02209-16. 10.1128/AAC.02209-16

74

Mataseje L. F. Peirano G. Church D. L. Conly J. Mulvey M. Pitout J. D. (2016). Colistin-Nonsusceptible Pseudomonas aeruginosa Sequence Type 654 with blaNDM-1 Arrives in North America.Antimicrob. Agents Chemother.601794–1800. 10.1128/AAC.02591-15

75

McCarthy M. W. (2019). Clinical pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of eravacycline.Clin. Pharmacokinet.10.1007/s40262-019-00767-z[Epub ahead of print].

76

Mendes R. E. Kiyota K. A. Monteiro J. Castanheira M. Andrade S. S. Gales A. C. et al (2006). Rapid detection and identification of metallo-beta-lactamase-encoding genes by multiplex real-time PCR assay and melt curve analysis.J. Clin. Microbiol.45544–547. 10.1128/jcm.01728-06

77

Monteiro J. Widen R. H. Pignatari A. C. Kubasek C. Silbert S. (2012). Rapid detection of carbapenemase genes by multiplex real-time PCR.J. Antimicrob. Chemother.67906–909. 10.1093/jac/dkr563

78

Moya B. Barcelo I. M. Cabot G. Torrens G. Palwe S. Joshi P. et al (2019). In Vitro and In Vivo activities of β-Lactams in combination with the Novel β-Lactam Enhancers Zidebactam and WCK 5153 against Multidrug-Resistant Metallo-β-Lactamase-Producing Klebsiella pneumoniae.Antimicrob. Agents Chemother.63:e0128-19.

79

Munoz-Price L. S. Poirel L. Bonomo R. A. Schwaber M. J. Daikos G. L. Cormican M. et al (2013). Clinical epidemiology of the global expansion of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemases.Lancet Infect. Dis.13785–796. 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70190-7

80

Mushtaq S. Vickers A. Woodford N. Haldimann A. Livermore D. M. (2019). Activity of nacubactam (RG6080/OP0595) combinations against MBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae.J. Antimicrob. Chemother.74953–960. 10.1093/jac/dky522

81

Nelson K. Hemarajata P. Sun D. Rubio-Aparicio D. Tsivkovski R. Yang S. et al (2017). Resistance to ceftazidime-avibactam is due to transposition of KPC in a porin-deficient strain of Klebsiella pneumoniae with increased efflux activity.Antimicrob. Agents Chemother.61:e0989-17. 10.1128/AAC.00989-17

82

Ni W. Han Y. Liu J. Wei C. Zhao J. Cui J. et al (2016). Tigecycline treatment for carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis.Medicine95:e3126. 10.1097/md.0000000000003126

83

Nicoloff H. Andersson D. I. (2013). Lon protease inactivation, or translocation of the lon gene, potentiate bacterial evolution to antibiotic resistance.Mol. Microbiol.901233–1248. 10.1111/mmi.12429

84

Nordmann P. Naas T. Poirel L. (2011). Global spread of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae.Emerg. Infect. Dis.171791–1798. 10.3201/eid1710.110655

85

Nordmann P. Poirel L. Dortet L. (2012). Rapid detection of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae.Emerg. Infect. Dis.181503–1507. 10.3201/eid1809.120355

86

Novais Â. Brilhante M. Pires J. Peixe L. (2015). Evaluation of the recently launched rapid carb blue kit for detection of carbapenemase-producing gram-negative bacteria.J. Clin. Microbiol.533105–3107. 10.1128/jcm.01170-15

87

Oliva A. Mascellino M. T. Cipolla A. D’Abramo A. De Rosa A. Savinelli S. et al (2015). Therapeutic strategy for pandrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae severe infections: short-course treatment with colistin increases the in vivo and in vitro activity of double carbapenem regimen.Int. J. Infect. Dis.33132–134. 10.1016/j.ijid.2015.01.011

88

Pan C. Y. Chen J. C. Chen T. L. Wu J. L. Hui C. F. Chen J. Y. (2015). Piscidin is highly active against carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii and NDM-1-producing Klebsiella pneumonia in a systemic septicaemia infection mouse model.Drugs132287–2305. 10.3390/md13042287

89

Papagiannitsis C. C. Študentová V. Izdebski R. Oikonomou O. Pfeifer Y. Petinaki E. et al (2015). Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry meropenem hydrolysis assay with NH4HCO3, a reliable tool for direct detection of carbapenemase activity.J. Clin. Microbiol.531731–1735. 10.1128/JCM.03094-14

90

Papp-Wallace K. M. Bethel C. R. Caillon J. Barnes M. D. Potel G. Bajaksouzian S. et al (2019). Beyond piperacillin-tazobactam: cefepime and AAI101 as a Potent β-Lactam-β-Lactamase inhibitor combination.Antimicrob. Agents Chemother.65:e00105-19.

91

Pasteran F. Gonzalez L. J. Albornoz E. Bahr G. Vila A. J. Corso A. (2016). Triton hodge test: improved protocol for modified hodge test for enhanced detection of NDM and other carbapenemase producers.J. Clin. Microbiol.54640–649. 10.1128/JCM.01298-15

92

Patel G. Bonomo R. A. (2013). “Stormy waters ahead”: global emergence of carbapenemases.Front. Microbiol.4:48. 10.3389/fmicb.2013.00048

93

Patel R. (2016). New developments in clinical bacteriology laboratories.Mayo Clin. Proc.911448–1459. 10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.06.020

94

Pires J. Novais A. Peixe L. (2013). Blue-carba, an easy biochemical test for detection of diverse carbapenemase producers directly from bacterial cultures.J. Clin. Microbiol.514281–4283. 10.1128/jcm.01634-13

95

Pitout J. D. Nordmann P. Poirel L. (2015). Carbapenemase-Producing Klebsiella pneumoniae, a key pathogen set for global nosocomial dominance.Antimicrob. Agents Chemother.595873–5884. 10.1128/AAC.01019-15

96

Poirel L. Héritier C. Nordmann P. (2004). Chromosome-encoded ambler class D beta-lactamase of Shewanella oneidensis as a progenitor of carbapenem-hydrolyzing oxacillinase.Antimicrob. Agents Chemother.48348–351. 10.1128/aac.48.1.348-351.2004

97

Pontikis K. Karaiskos I. Bastani S. Dimopoulos G. Kalogirou M. Katsiari M. et al (2014). Outcomes of critically ill intensive care unit patients treated with fosfomycin for infections due to pandrug-resistant and extensively drug-resistant carbapenemase-producing Gram-negative bacteria.Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents4352–59. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2013.09.010

98

Qazi T. Amaratunga T. Barnes E. L. Fischer M. Kassam Z. Allegretti J. R. (2017). The risk of inflammatory bowel disease flares after fecal microbiota transplantation: systematic review and meta-analysis.Gut Microbes8574–588. 10.1080/19490976.2017.1353848

99

Ramirez J. Dartois N. Gandjini H. Yan J. L. KorthBradley J. McGovern P. C. (2013). Randomized phase 2 trial to evaluate the clinical efficacy of two high-dosage tigecycline regimens versus imipenem-cilastatin for treatment of hospital-acquired pneumonia.Antimicrob. Agents Chemother.571756–1762. 10.1128/AAC.01232-12

100

Rapp E. Samuelsen Ø. Sundqvist M. (2018). Detection of carbapenemases with a newly developed commercial assay using matrix assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight.J. Microbiol. Methods14637–39. 10.1016/j.mimet.2018.01.008

101

Riddle V. D. Cebrik D. S. Armstrong E. S. Cass R. T. Clobes T. C. Hillan K. J. (2012). “Plazomicin Safety and Efficacy in Patients with Complicated Urinary Tract Infection (cUTI) or Acute Pyelonephritis (AP),” in Proceedings of the Poster L2-2118a. Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy Annual Conference, San Francisco, CA.

102

Ritchie D. J. Garavaglia-Wilson A. (2014). A review of intravenous minocycline for treatment of multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter infections.Clin. Infect. Dis.59(Suppl.6), S374–S380. 10.1093/cid/ciu613

103

Rodríguez-Baño J. Gutiérrez-Gutiérrez B. Machuca I. Pascual A. (2018). Treatment of infections caused by extended-spectrum-beta-lactamase-, AmpC-, and carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae.Clin. Microbiol. Rev.31:e079-17. 10.1128/CMR.00079-17

104

Sader H. S. Castanheira M. Flamm R. K. Mendes R. E. Farrell D. J. Jones R. N. (2015). Tigecycline activity tested against carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae from 18 European nations: results from the SENTRY surveillance program (2010–2013).Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis.83183–186. 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2015.06.011

105

Sauget M. Cabrolier N. Manzoni M. Bertrand X. Hocquet D. (2014). Rapid, sensitive and specific detection of OXA-48-like-producing Enterobacteriaceae by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry.J. Microbiol. Methods10588–91. 10.1016/j.mimet.2014.07.004

106

Shatzkes K. Singleton E. Tang C. Zuena M. Shukla S. Gupta S. et al (2016). Predatory bacteria attenuate Klebsiella pneumoniae burden in rat lungs.mBio7:e01847-16. 10.1128/mBio.01847-16

107

Shen F. Han Q. Xie D. Fang M. Zeng H. Deng Y. (2015). Efficacy and safety of tigecycline for the treatment of severe infectious diseases: an updated meta-analysis of RCTs.Int. J. Infect. Dis.3925–33. 10.1016/j.ijid.2015.08.009

108

Shields R. K. Chen L. Cheng S. Chavda K. D. Press E. G. Snyder A. et al (2017). Emergence of ceftazidime-avibactam resistance due to plasmid-borne blaKPC-3 mutations during treatment of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae Infections.Antimicrob. Agents Chemother61:e02097-16. 10.1128/AAC.02097-16

109

Shields R. K. Potoski B. A. Haidar G. Hao B. Doi Y. Chen L. et al (2016). Clinical outcomes, drug toxicity and emergence of ceftazidime-avibactam resistance among patients treated for carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae infections.Clin. Infect. Dis.631615–1618. 10.1093/cid/ciw636

110

Sims M. Mariyanovski V. Mcleroth P. Akers W. Lee Y. C. Brown M. L. et al (2017). Prospective, randomized, double-blind, Phase 2 dose-ranging study comparing efficacy and safety of imipenem/cilastatin plus relebactam with imipenem/cilastatin alone in patients with complicated urinary tract infections.J. Antimicrob. Chemother.722616–2626. 10.1093/jac/dkx139

111

Skurnik D. Roux D. Pons S. Guillard T. Lu X. Cywes-Bentley C. et al (2016). Extended-spectrum antibodies protective against carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae.J. Antimicrob. Chemother.71927–935. 10.1093/jac/dkv448

112

Solomkin J. S. Ramesh M. K. Cesnauskas G. Novikovs N. Stefanova P. Sutcliffe J. A. et al (2014). Phase 2, randomized, double-blind study of the efficacy and safety of two dose regimens of eravacycline versus ertapenem for adult community-acquired complicated intra-abdominal infections.Antimicrob. Agents Chemother.581847–1854. 10.1128/AAC.01614-13

113

Spanu T. De Angelis G. Cipriani M. Pedruzzi B. D’Inzeo T. Cataldo M. A. et al (2012). In vivo emergence of tigecycline resistance in multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae and Escherichia coli.Antimicrob. Agents Chemother.564516–4518. 10.1128/AAC.00234-12

114

Srisrattakarn A. Lulitanond A. Wilailuckana C. Charoensri N. Wonglakorn L. Saenjamla P. et al (2017). Rapid and simple identification of carbapenemase genes, blaNDM, blaOXA-48, blaVIM, blaIMP-14 and blaKPC groups, in Gram-negative bacilli by in-house loop-mediated isothermal amplification with hydroxynaphthol blue dye.World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol.33:130.

115

Stewart A. Harris P. Henderson A. Paterson D. (2018). Treatment of infections by OXA-48-producing Enterobacteriaceae.Antimicrob. Agents Chemother.62:e01195-18. 10.1128/AAC.01195-18

116

Swayne R. L. Ludlam H. A. Shet V. G. Woodford N. Curran M. D. (2011). Real-time TaqMan PCR for rapid detection of genes encoding five types of non-metallo- (class A and D) carbapenemases in Enterobacteriaceae.Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents3835–38. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2011.03.010

117

Takeuchi D. Akeda Y. Sugawara Y. Sakamoto N. Yamamoto N. Shanmugakani R. K. et al (2018). Establishment of a dual-wavelength spectrophotometric method for analysing and detecting carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae.Sci. Rep.8:15689. 10.1038/s41598-018-33883-0

118

Tamma P. D. Opene B. N. Gluck A. Chambers K. K. Carroll K. C. Simner P. J. (2017). Comparison of 11 phenotypic assays for accurate detection of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae.J. Clin. Microbiol.551046–1055. 10.1128/JCM.02338-16

119

Tasina E. Haidich A. B. Kokkali S. Arvanitidou M. (2011). Efficacy and safety of tigecycline for the treatment of infectious diseases: a meta-analysis.Lancet Infect. Dis.11834–844. 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70177-3

120

Tato M. Ruiz-Garbajosa P. Traczewski M. Dodgson A. McEwan A. Humphries R. et al (2016). Multisite evaluation of cepheid Xpert Carba-R Assay for detection of carbapenemase-producing organisms in rectal swabs.J. Clin. Microbiol.541814–1819. 10.1128/JCM.00341-16

121

Thaden J. T. Pogue J. M. Kaye K. S. (2017). Role of newer and re-emerging older agents in the treatment of infections caused by carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae.Virulence8403–416. 10.1080/21505594.2016.1207834

122

Thomson K. S. AbdelGhani S. Snyder J. W. Thomson G. K. (2019). Activity of cefepime-zidebactam against multidrug-resistant (MDR) gram-negative pathogens.Antibiotics8:32. 10.3390/antibiotics8010032

123

Trifi A. Abdellatif S. Daly F. Mahjoub K. Nasri R. Oueslati M. et al (2016). Efficacy and toxicity of high-dose colistin in multidrug-resistant gram-negative bacilli infections: a comparative study of a matched series.Chemotherapy61190–196. 10.1159/000442786

124

Tsakris A. Poulou A. Pournaras S. Voulgari E. Vrioni G. Themeli-Digalaki K. et al (2010). A simple phenotypic method for the differentiation of metallo-b-lactamases and class A KPC carbapenemases in Enterobacteriaceae clinical isolates.J. Antimicrob. Chemother.651664–1671. 10.1093/jac/dkq210

125

Tsang K. Y. Luk S. Lo J. Y. Tsang T. Y. Lai S. T. Ng T. K. (2012). HongKong experiences the ‘Ultimate superbug’: NDM-1 Enterobacteriaceae.Hong Kong Med. J.18439–441.

126

Tuon F. F. Rocha J. L. Formigoni-Pinto M. R. (2018). Pharmacological aspects and spectrum of action of ceftazidime-avibactam: a systematic review.Infection46165–181. 10.1007/s15010-017-1096-y

127

Tzouvelekis L. S. Markogiannakis A. Psichogiou M. Tassios P. T. Daikos G. L. (2012). Carbapenemases in Klebsiella pneumoniae and other Enterobacteriaceae: an evolving crisis of global dimensions.Clin. Microbiol. Rev.25682–707. 10.1128/CMR.05035-11

128

Valachis A. Samonis G. Kofteridis D. P. (2015). The role of aerosolized colistin in the treatment of ventilator-associated pneumonia: a systematic review and meta-analysis.Crit. Care Med.43527–533. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000771

129

Van Almsick V. Ghebremedhin B. Pfennigwerth N. Ahmad-Nejad P. (2018). Rapid detection of carbapenemase-producing Acinetobacter baumannii and carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae using a bioluminescence-based phenotypic method.J. Microbiol. Methods14720–25. 10.1016/j.mimet.2018.02.004

130

van der Zwaluw K. de Haan A. Pluister G. N. Bootsma H. J. de Neeling A. J. Schouls L. M. (2015). The carbapenem inactivation method (CIM), a simple and low-cost alternative for the Carba NP test to assess phenotypic carbapenemase activity in gram-negative rods.PLoS One10:e0123690. 10.1371/journal.pone.0123690

131

van Duin D. Bonomo R. A. (2016). Ceftazidime/Avibactam and Ceftolozane/Tazobactam: second-generation β-Lactam/β-Lactamase inhibitor combinations.Clin. Infect. Dis.63234–241. 10.1093/cid/ciw243

132

van Duin D. Cober E. D. Richter S. S. Perez F. Cline M. Kaye K. S. et al (2014). Tigecycline therapy for carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae (CRKP) bacteriuria leads to tigecycline resistance.Clin. Microbiol. Infect.20O1117–O1120. 10.1111/1469-0691.12714

133

van Duin D. Kaye K. S. Neuner E. A. Bonomo R. A. (2013). Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae: a review of treatment and outcomes.Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis.75115–120. 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2012.11.009

134

van Duin D. Lok J. J. Earley M. Cober E. Richter S. S. Perez F. et al (2018). Colistin versus ceftazidime-avibactam in the treatment of infections due to carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae.Clin. Infect. Dis.66163–171. 10.1093/cid/cix783

135

Vasoo S. Cunningham S. A. Cole N. C. Kohner P. C. Menon S. R. Krause K. M. et al (2015). In vitro activities of ceftazidime-avibactam, aztreonamavibactam, and a panel of older and contemporary antimicrobial agents against carbapenemase-producing gram-negative bacilli.Antimicrob. Agents Chemother.597842–7846. 10.1128/AAC.02019-15

136

Vatopoulos A. (2008). High rates of metallo-beta-lactamase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in Greece–a review of the current evidence.Euro Surveill.13:8023.

137

Vercoe R. B. Chang J. T. Dy R. L. Taylor C. Gristwood T. Clulow J. S. et al (2013). Cytotoxic chromosomal targeting by CRISPR/Cas systems can reshape bacterial genomes and expel or remodel pathogenicity islands.PLoS Genet.9:e1003454. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003454

138

Walker G. T. Rockweiler T. J. Kersey R. K. Frye K. L. Mitchner S. R. Toal D. R. et al (2016). Analytical performance of multiplexed screening test for 10 antibiotic resistance genes from perianal swab samples.Clin. Chem.62353–359. 10.1373/clinchem.2015.246371

139

Walkty A. Adam H. Baxter M. Denisuik A. LagaceWiens P. Karlowsky J. A. et al (2014). In vitro activity of plazomicin against 5,015 g-negative and gram-positive clinical isolates obtained from patients in canadian hospitals as part of the CANWARD study,2011–2012.Antimicrob. Agents Chemother.582554–2563. 10.1128/aac.02744-13

140

Walsh T. R. Toleman M. A. Poirel L. Nordmann P. (2005). Metallo-ß-lactamases: the quiet before the storm?Clin. Microbiol. Rev.18306–325. 10.1128/cmr.18.2.306-325.2005

141

Wang J. Yuan M. Chen H. Chen X. Jia Y. Zhu X. et al (2017). First report of Klebsiella oxytoca strain simultaneously producing NDM-1, IMP-4, and KPC-2 carbapenemases.Antimicrob. Agents Chemother.61:e0877-17. 10.1128/AAC.00877-17

142

Wang Q. Zhang P. Zhao D. Jiang Y. Zhao F. Wang Y. et al (2018). Emergence of tigecycline resistance in Escherichia coli co-producing MCR-1 and NDM-5 during tigecycline salvage treatment.Infect. Drug Resist.112241–2248. 10.2147/IDR.S179618

143

Wang S. Xu M. Wang W. Cao X. Piao M. Khan S. et al (2016). Systematic review: adverse events of fecal microbiota transplantation.PLoS One11:e0161174. 10.1371/journal.pone.0161174

144

Wang Z. K. Yang Y. S. Chen Y. Yuan J. Sun G. Peng L. H. (2014). Intestinal microbiota pathogenesis and fecal microbiota transplantation for inflammatory bowel disease.World J. Gastroenterol.2014805–14820. 10.3748/wjg.v20.i40.14805

145

Wei Z. Q. Du X. X. Yu Y. S. Shen P. Chen Y. G. Li L. J. (2007). Plasmid-mediated KPC-2 in a Klebsiella pneumoniae isolate from China.Antimicrob. Agents Chemother.51763–765. 10.1128/aac.01053-06

146

Woodford N. Eastaway A. T. Ford M. Leanord A. Keane C. Quayle R. M. et al (2010). Comparison of BD Phoenix, Vitek2 and MicroScan automated systems for detection and inference of mechanisms responsible for carbapenem resistance in Enterobacteriaceae.J. Clin. Microbiol.482999–3002. 10.1128/jcm.00341-10

147

Yang B. Feng Y. McNally A. Zong Z. (2018). Occurrence of Enterobacter hormaechei carrying blaNDM-1 and blaKPC-2 in China.Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis.90139–142. 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2017.10.007

148

Yao X. Doi Y. Zeng L. Lv L. Liu J. H. (2016). Carbapenem-resistant and colistinresistant Escherichia coli co-producing NDM-9 and MCR-1.Lancet Infect. Dis.16288–289. 10.1016/s1473-3099(16)00057-8

149

Yigit H. Queenan A. M. Anderson G. J. Domenech-Sanchez A. Biddle J. W. Steward C. D. et al (2001). Novel carbapenem-hydrolyzing beta-lactamase, KPC-1, from a carbapenem-resistant strain of Klebsiella pneumoniae.Antimicrob. Agents Chemother.451151–1161. 10.1128/aac.45.4.1151-1161.2001

150

Yong D. Toleman M. A. Giske C. G. Cho H. S. Sundman K. Lee K. et al (2009). Characterization of a new metallo-beta-lactamase gene, blaNDM-1, and a novel erythromycin esterase gene carried on a unique genetic structure in Klebsiella pneumoniae sequence type 14 from India.Antimicrob. Agents Chemother.535046–5054. 10.1128/aac.00774-09

151

Yu J. Liu J. Li Y. Yu J. Zhu W. Liu Y. et al (2018a). Rapid detection of carbapenemase activity of Enterobacteriaceae isolated from positive blood cultures by MALDI-TOF MS.Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob.17:22. 10.1186/s12941-018-0274-9

152

Yu F. Lv J. Niu S. Du H. Tang Y. W. Pitout J. et al (2018b). Multiplex PCR analysis for rapid detection of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenem-resistant (Sequence Type 258 [ST258] and ST11) and Hypervirulent (ST23, ST65, ST86, and ST375) Strains.J. Clin. Microbiol.56:e0731-18. 10.1128/JCM.00731-18

153

Yu F. Lv J. Niu S. Du H. Tang Y. W. Bonomo R. A. et al (2018c). In Vitro activity of ceftazidime-avibactam against carbapenem-resistant and hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates.Antimicrob. Agents Chemother.62:e1031-18. 10.1128/AAC.01031-18

154

Zendo T. (2013). Screening and characterization of novel bacteriocins from lactic acid bacteria.Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem.77893–899. 10.1271/bbb.130014

155

Zhanel G. G. Cheung D. Adam H. Zelenitsky S. Golden A. Schweizer F. et al (2016). Review of eravacycline, a novel fluorocycline antibacterial agent.Drugs76567–588. 10.1007/s40265-016-0545-8

156

Zhanel G. G. Golden A. R. Zelenitsky S. Wiebe K. Lawrence C. K. Adam H. J. et al (2019). Cefiderocol: a siderophore cephalosporin with activity against carbapenem-resistant and multidrug-resistant gram-negative bacilli.Drugs79271–289. 10.1007/s40265-019-1055-2

157

Zhanel G. G. Lawrence C. K. Adam H. Schweizer F. Zelenitsky S. Zhanel M. et al (2018). Imipenem-Relebactam and meropenem-vaborbactam: two novel Carbapenem-β-Lactamase inhibitor combinations.Drugs7865–98. 10.1007/s40265-017-0851-9

158

Zhang R. Liu L. Zhou H. Chan E. W. Li J. Fang Y. et al (2017). Nationwide surveillance of clinical Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) strains in China.EBioMedicine1998–106. 10.1016/j.ebiom.2017.04.032

159

Zhang Y. Wang Q. Yin Y. Chen H. Jin L. Gu B. et al (2018). Epidemiology of Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae infections: report from the China CRE Network.Antimicrob. Agents Chemother.62:e1882-17. 10.1128/AAC.01882-17

160

Zhang G. Zheng G. Zhang Y. Ma R. Kang X. (2018). Evaluation of a micro/nanofluidic chip platform for the high-throughput detection of bacteria and their antibiotic resistance genes in post-neurosurgical meningitis.Int. J. Infect. Dis.70115–120. 10.1016/j.ijid.2018.03.012

161

Zheng B. Yu X. Xu H. Guo L. Zhang J. Huang C. et al (2017). Complete genome sequencing and genomic characterization of two Escherichia coli strains co-producing MCR-1 and NDM-1 from bloodstream infection.Sci. Rep.7:17885. 10.1038/s41598-017-18273-2

Summary

Keywords

carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae, CRE, prevalence, rapid detection, treatment

Citation

Cui X, Zhang H and Du H (2019) Carbapenemases in Enterobacteriaceae: Detection and Antimicrobial Therapy. Front. Microbiol. 10:1823. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.01823

Received

03 March 2019

Accepted

24 July 2019

Published

20 August 2019

Volume

10 - 2019

Edited by

Bing Gu, Xuzhou Medical University, China

Reviewed by

Murat Akova, Hacettepe University, Turkey; Yukihiro Akeda, Osaka University, Japan; Qiwen Yang, Peking Union Medical College Hospital (CAMS), China

Updates

Copyright

© 2019 Cui, Zhang and Du.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Hong Du, hong_du@126.com; hongdu@suda.edu.cn

This article was submitted to Infectious Diseases, a section of the journal Frontiers in Microbiology

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.