Abstract

An in-depth study of the phylogeny and taxonomy of the corticioid genus Phlebiopsis (Phanerochaetaceae) was conducted. Phylogenetic analyses of the ITS1-5.8S-ITS2 and nrLSU sequences demonstrated that Phlebiopsis is a strongly supported clade which is distinct from its sister clades of Phaeophlebiopsis, Hapalopilus, and Rhizochaete. Two genera, Australohydnum and Hjortstamia, are reduced to synonyms under Phlebiopsis as generic type species A. griseofuscescens and H. friesii, respectively, are embedded in the Phlebiopsis clade. Twenty-four lineages are resolved in the ITS phylogenetic tree of Phlebiopsis, including six new taxa, viz. P. albescens, P. brunnea, P. cylindrospora, P. magnicystidiata, P. membranacea and P. sinensis, from Sri Lanka and China. Five new combinations, viz. Phaeophlebiopsis mussooriensis, Phlebiopsis bambusicola, P. dregeana, P. griseofuscescens and P. novae-granatae, are proposed. Phlebiopsis crassa is a morphological species complex with three distinct lineages. Phlebiopsis lamprocystidiata is determined to be a later synonym of P. darjeelingensis. The new taxa are described, illustrated, and compared and contrasted to morphologically similar species. An emended description of Phlebiopsis is provided along with an identification key to 27 accepted species.

Introduction

In 1978, Phlebiopsis Jülich was suggested for Thelephora gigantea Fr. that has effused, ceraceous basidiomata with a smooth to odontoid hymenophore, a monomitic hyphal system with colorless, partially agglutinated, simple-septate hyphae, lamprocystidia with thick, colorless walls, and basidiospores with colorless, thin, smooth walls that do not react in Melzer’s reagent or cotton blue (Jülich, 1978; Bernicchia and Gorjón, 2010). Over the next 40 years, 12 species with similar morphology were described in or transferred to the genus by Hjortstam and Ryvarden (1980), Jülich and Stalpers (1980), Dhingra (1987), Hjortstam (1987), Gilbertson and Adaskaveg (1993), Douanla-Meli and Langer (2009), Wu et al. (2010), Priyanka et al. (2011), Kaur et al. (2015), and Zhao et al. (2018). Morphologically, Phlebiopsis is similar to Scopuloides (Massee) Höhn. & Litsch. and some species of Phanerochaete P. Karst based on the characteristics of lamprocystidia and simple-septate generative hyphae. It was traditionally placed in the Phanerochaete sensu lato group (Rattan, 1977; Burdsall, 1985). Although Burdsall (1985) considered Phlebiopsis and Scopuloides to be synonyms of Phanerochaete, most researchers at the time recognized the genera as distinct (Eriksson et al., 1978, 1981, 1984; Jülich and Stalpers, 1980; Wu, 1990).

The generic circumscription of Phlebiopsis was expanded when molecular studies showed that Phanerochaete crassa (Lév.) Burds. and Phlebiopsis gigantea (Fr.) Jülich were closely related (de Koker et al., 2003; Greslebin et al., 2004; Wu et al., 2010; Floudas and Hibbett, 2015). With the inclusion of P. crassa, Phlebiopsis now also includes species with effused-reflexed, coriaceous basidiomata, a dimitic hyphal system, and lamprocystidia or skeletocystidia with light brown walls. In addition, based on both phylogenetic and morphological evidence, Floudas and Hibbett (2015) created Phaeophlebiopsis Floudas & Hibbett to accommodate Phlebiopsis peniophoroides Gilb. & Adask. and similar species with ceraceous, beige-brown basidiomata and subicula, lamprocystidia with brown walls, and small basidiospores. The limits of the Phlebiopsis clade were extended by Miettinen et al. (2016) who transferred six species into Phlebiopsis. The results of their phylogenetic study showed that the type species of Castanoporus Ryvarden, Merulius castaneus Lloyd, was nested in a clade with P. gigantea and, therefore, a synonym of Phlebiopsis. Similarly, Dentocorticium pilatii (Parmasto) Duehm & Michel, Lopharia papyrina (Mont.) Boidin, Phanerochaete brunneocystidiata Sheng H. Wu, and Phanerochaete laxa Sheng H. Wu clustered in the Phlebiopsis clade, and were all transferred to the genus. Based on the morphological similarity of Thelephora friesii Lév., the type of HjortstamiaBoidin and Gilles, 2003 to L. papyrina and P. crassa, they also transferred T. friesii to Phlebiopsis, thereby reducing Hjortstamia to a synonym of Phlebiopsis. Phlebiopsis pilatii (Parmasto) Spirin & Miettinen is unique in the genus for it has a dimitic hyphal system of simple-septate generative and microbinding (squeletto-ligatives) hyphae and finely branched hyphidia but lacks lamprocystidia or skeletal cystidia (Larsen and Gilberston, 1977; Duhem and Michel, 2009).

With Hjortstamia and Castanoporus as synonyms, Phlebiopsis became a morphologically heterogeneous genus with effused, effused-reflexed or pileate basidiomata with a membranous, ceraceous, corneous or coriaceous texture, hymenophore smooth to tuberculate, odontoid, or poroid, hyphal system monomitic or dimitic with a loose to compact subiculum, and typically with lamprocystidia or skeletocystidia with colorless to brown walls. In phylogenetic analyses of Phanerochaetaceae, Phlebiopsis species are in a clade sister to Rhizochaete Gresl., Nakasone & Rajchenb., Hapalopilus P. Karst. and Phaeophlebiopsis, but distant from Phanerochaete sensu stricto and Scopuloides (Floudas and Hibbett, 2015; Miettinen et al., 2016).

Another genus of interest is Australohydnum Jülich for it is similar to Phlebiopsis by its warted, irpicoid to hydnoid hymenophore, a dimitic hyphal system with colorless, encrusted skeletocystidia, and thin-walled, smooth basidiospores (Jülich, 1978). The morphological similarities between Australohydnum and Phanerochaete sensu lato were observed by Hjortstam and Ryvarden (1990). In a limited study of Irpex sensu stricto, sequences of A. dregeanum (Berk.) Hjortstam & Ryvarden and I. vellereus Berk. & Broome (a possible synonym of A. dregeanum) clustered together in a clade sister to Phanerochaete chrysosporium Burds. and Phanerochaete sordida (P. Karst.) J. Erikss. & Ryvarden (Lim and Jung, 2003). However, the phylogenetic relationship of Australohydnum within the Phanerochaetaceae remained unknown (Miettinen et al., 2016).

Among the 24 names of Phlebiopsis recovered in Index Fungorum1 (accessed on 21 January2020), four species were transferred to Phaeophlebiopsis. Of the remaining 20 species, 11 were described originally from Asia (Dhingra, 1987; Wu, 2000, 2004; Priyanka et al., 2011; Kaur et al., 2015; Zhao et al., 2018; Xu et al., 2020). More than 150 specimens of Phlebiopsis were collected by the corresponding author from China and Southeast Asia in recent years. Based on these specimens and sequences obtained from GenBank, the phylogenetic analyses and taxonomic study of Phlebiopsis and related taxa in the Phanerochaetaceae were undertaken. This study is a contribution to the understanding of the diversity and phylogenetic relationships of crust fungi in China.

Materials and Methods

Specimen Collection

Field trips for specimen collection in many kinds of Nature Reserves and Forest Parks in China and other countries were carried out by the authors. In situ photos of the fungi were taken with a Canon camera EOS 70D (Canon Corporation, Japan). Fresh specimens were dried with a portable drier (manufactured in Finland). Dried specimens were labeled and then stored in a refrigerator of minus 40°C for 2 weeks to kill the insects and their eggs before they were ready for morphological and molecular studies.

Morphological Studies

Voucher specimens are deposited at the herbaria of Beijing Forestry University, Beijing, China (BJFC), Centre for Forest Mycology Research, U.S. Forest Service, Madison, WI, United States (CFMR), National Museum of Natural Science, Taichung, Taiwan, China (TNM) and Beijing Museum of Natural History, Beijing, China (BJM). The Sri Lankan voucher specimens are deposited in the Faculty of Agriculture, University of Ruhuna, Kamburupitiya, Sri Lanka and the herbarium of Beijing Forestry University, Beijing, China (BJFC), and were studied under the material transfer agreement signed by the two universities. Freehand sections were made from dried basidiomata and mounted in 2% (w/v) potassium hydroxide (KOH), 1% (w/v) phloxine, Melzer’s reagent (IKI) or cotton blue (CB). Microscopic examinations were carried out with a Nikon Eclipse 80i microscope (Nikon Corporation, Japan) at magnifications up to 1000×. Drawings were made with the aid of a drawing tube. The following abbreviations are used: IKI–, neither amyloid nor dextrinoid; CB–, acyanophilous; L, mean spore length; W, mean spore width; Q, L/W ratio; n (a/b), number of spores (a) measured from number of specimens (b). Color codes and names follow Kornerup and Wanscher (1978).

DNA Extraction and Sequencing

A CTAB plant genomic DNA extraction Kit DN14 (Aidlab Biotechnologies Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) was used to extract total genomic DNA from dried specimens then amplified by the polymerase chain reaction (PCR), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The ITS1-5.8S-ITS2 region was amplified with the primer pair ITS5/ITS4 (White et al., 1990) using the following protocol: initial denaturation at 95°C for 4 min, followed by 34 cycles at 94°C for 40 s, 58°C for 45 s and 72°C for 1 min, and final extension at 72°C for 10 min. The nrLSU D1-D2 region was amplified with the primer pair LR0R/LR72 employing the following procedure: initial denaturation at 94°C for 1 min, followed by 34 cycles at 94°C for 30 s, 50°C for 1 min and 72°C for 1.5 min, and final extension at 72°C for 10 min. DNA sequencing was performed at Beijing Genomics Institute, and the sequences were deposited in GenBank3 (Table 1). BioEdit v.7.0.5.3 (Hall, 1999) and Geneious Basic v.11.1.15 (Kearse et al., 2012) were used to review the chromatograms and for contig assembly.

TABLE 1

| Taxa | Voucher | Locality | ITS | nrLSU | References |

| Bjerkandera adusta | HHB-12826-Sp | United States | KP134983 | KP135198 | Floudas and Hibbett (2015) |

| B. centroamericana | L-13104-sp | Costa Rica | KY948791 | KY948855 | Justo et al. (2017) |

| Crepatura ellipsospora | CLZhao 1265 | China | MK343692 | MK343696 | Ma and Zhao (2019) |

| Donkia pulcherrima | GC 1707-11 | China | LC378994 | LC379152 | Chen et al. (2018b) |

| Geliporus exilisporus | Dai 2172 | China | KU598211 | KU598216 | Yuan et al. (2017) |

| Hapalopilus eupatorii | Dammrich 10744 | Germany | KX752620 | KX752620 | Miettinen et al. (2016) |

| H. percoctus | Miettinen 2008 | Botswana | KX752597 | KX752597 | Miettinen et al. (2016) |

| H. nidulans | JV0206/2 | Sweden | KX752623 | KX752623 | Miettinen et al. (2016) |

| Hyphodermella corrugata | MA-Fungi 5527 | Morocco | FN600372 | JN939597 | Telleria et al. (2010) |

| H. poroides | Dai 10848 | China | KX008368 | KX011853 | Zhao et al. (2017) |

| H. rosae | FP-150552 | United States | KP134978 | KP135223 | Floudas and Hibbett (2015) |

| Irpex vellereus | CBS 515.92 | India | AF479670 | — | Lim and Jung (2003) |

| Odontoefibula orientalis | GC 1703-76 | China | LC379004 | LC379156 | Chen et al. (2018b) |

| Oxychaete cervinogilvus | Schigel-5216 | Australia | KX752596 | KX752596 | Miettinen et al. (2016) |

| Phaeophlebiopsis caribbeana | HHB-6990 | United States | KP135415 | KP135243 | Floudas and Hibbett (2015) |

| P. himalayensis | He 3854 | China | MT386378 | MT447410 | Present study |

| P. peniophoroides | FP-150577 | United States | KP135417 | KP135273 | Floudas and Hibbett (2015) |

| P. ravenelii | CBS 411.50 | France | MH856691 | MH868208 | Vu et al. (2019) |

| P. ravenelii | FCUG 2216 | France | — | GQ470674 | Wu et al. (2010) |

| Phanerina mellea | Miettinen 11393 | Indonesia | KX752602 | KX752602 | Miettinen et al. (2016) |

| Phanerochaete arizonica | RLG-10248-Sp | United States | KP135170 | KP135239 | Floudas and Hibbett (2015) |

| P. australis | HHB-7105-Sp | United States | KP135081 | KP135240 | Floudas and Hibbett (2015) |

| P. bambusicola | Wu 0707-2 | China | MF399404 | MF399395 | Wu et al. (2018b) |

| P. brunnea | He 1873 | China | KX212220 | KX212224 | Liu and He (2016) |

| P. burtii | HHB-4618-Sp | United States | KP135117 | KP135241 | Floudas and Hibbett (2015) |

| P. canobrunnea | CHWC 1506-66 | China | LC412095 | LC412104 | Wu et al. (2018a) |

| P. carnosa | HHB-9195 | United States | KP135129 | KP135242 | Floudas and Hibbett (2015) |

| P. chrysosporium | HHB-6251-Sp | United States | KP135094 | KP135246 | Floudas and Hibbett (2015) |

| P. citrinosanguinea | FP-105385-Sp | United States | KP135100 | KP135234 | Floudas and Hibbett (2015) |

| P. concrescens | Spirin 7322 | Russia | KP994380 | KP994382 | Volobuev et al. (2015) |

| P. cumulodentata | LE 298935 | Russia | KP994359 | KP994386 | Volobuev et al. (2015) |

| P. cystidiata | Wu 1708-326 | China | LC412097 | LC412100 | Wu et al. (2018a) |

| P. ericina | HHB-2288 | United States | KP135167 | KP135247 | Floudas and Hibbett (2015) |

| P. incarnata | WEI 16-075 | China | MF399406 | MF399397 | Wu et al. (2018b) |

| P. inflata | Dai 10376 | China | JX623929 | JX644062 | Jia et al. (2014) |

| P. laevis | HHB-15519 | United States | KP135149 | KP135249 | Floudas and Hibbett (2015) |

| P. livescens | FD-106 | United States | KP135070 | KP135253 | Floudas and Hibbett (2015) |

| P. magnoliae | HHB-9829-Sp | United States | KP135089 | KP135237 | Floudas and Hibbett (2015) |

| P. porostereoides | He 1902 | China | KX212217 | KX212221 | Liu and He (2016) |

| P. pseudomagnoliae | PP-25 | South Africa | KP135091 | KP135250 | Floudas and Hibbett (2015) |

| P. pseudosanguinea | FD-244 | United States | KP135098 | KP135251 | Floudas and Hibbett (2015) |

| P. rhodella | FD-18 | United States | KP135187 | KP135258 | Floudas and Hibbett (2015) |

| P. robusta | Wu 1109-69 | China | MF399409 | MF399400 | Wu et al. (2018b) |

| P. sanguinea | HHB-7524 | United States | KP135101 | KP135244 | Floudas and Hibbett (2015) |

| P. sanguineocarnosa | FD-359 | United States | KP135122 | KP135245 | Floudas and Hibbett (2015) |

| P. sordida | FD-241 | United States | KP135136 | KP135252 | Floudas and Hibbett (2015) |

| P. stereoides | He 2309 | China | KX212219 | KX212223 | Liu and He (2016) |

| P. subceracea | FP-105974-R | United States | KP135162 | KP135255 | Floudas and Hibbett (2015) |

| P. taiwaniana | Wu 0112-13 | China | MF399412 | MF399403 | Wu et al. (2018b) |

| P. velutina | Kotiranta 25567 | Russia | KP994354 | KP994387 | Volobuev et al. (2015) |

| Phlebia firma | Edman K268 | Sweden | EU118654 | EU118654 | Larsson (2007) |

| P. lilascens | FCUG 2005 | — | AF141622 | AF141622 | — |

| Phlebiopsis albescens | He 5805* | Sri Lanka | MT452526 | — | Present study |

| P. amethystea | URM 93248 | Brazil | MK993644 | MK993638 | Xavier de Lima et al. (2020) |

| P. amethystea | URM 84741 | Brazil | MK993645 | MK993639 | Xavier de Lima et al. (2020) |

| P. brunnea | He 5822* | Sri Lanka | MT452527 | MT447451 | Present study |

| P. brunneocystidiata | Chen 666 | China | MT561707 | GQ470640 | Wu et al. (2010), present study |

| P. brunneocystidiata | Chen 1143 | China | — | GQ470639 | Wu et al. (2010) |

| P. castanea | Spirin-5295 | Russia | KX752610 | KX752610 | Miettinen et al. (2016) |

| P. castanea | GC 1612-6 | China | KY688208 | — | Chen et al. (2018a) |

| P. castanea | CLZhao 3501 | China | MK269230 | — | — |

| P. castanea | He 2489 | China | — | MT447406 | Present study |

| P. crassa group A | He 5205 | Vietnam | MT452523 | MT447448 | Present study |

| P. crassa group A | He 5763 | Sri Lanka | MT452524 | MT447449 | Present study |

| P. crassa group A | He 5855 | China | MT452525 | MT447450 | Present study |

| P. crassa group A | He 6304 | China | MT561714 | MT598029 | Present study |

| P. crassa group A | Wu 0504-22 | China | MT561715 | GQ470634 | Wu et al. (2010), present study |

| P. crassa group B | He 3349 | China | MT561712 | MT447407 | Present study |

| P. crassa group B | He 5866 | China | MT386376 | MT447408 | Present study |

| P. crassa group B | He 6266 | China | MT561713 | MT598035 | Present study |

| P. crassa group B | CLZhao 724 | China | MG231790 | — | — |

| P. crassa group B | MAFF 420737 | Japan | AB809163 | AB809163 | — |

| P. crassa group C | KKN-86-Sp | United States | KP135394 | KP135215 | Floudas and Hibbett (2015) |

| P. crassa group C | FP-102496-sp | United States | AY219341 | — | de Koker et al. (2003) |

| P. crassa group C | HHB 8834 | United States | KP135393 | — | Floudas and Hibbett (2015) |

| P. crassa group C | ME 516 | United States | KP135395 | — | Floudas and Hibbett (2015) |

| P. cylindrospora | He 5932 | China | MT386403 | MT447444 | Present study |

| P. cylindrospora | He 5984* | China | MT386404 | MT447445 | Present study |

| P. cylindrospora | He 6054 | China | MT561716 | MT598030 | Present study |

| P. cylindrospora | He 6063 | China | MT561717 | MT598031 | Present study |

| P. darjeelingensis | He 3874 | China | MT386382 | MT447418 | Present study |

| P. darjeelingensis | He 5910 | China | MT386383 | MT447419 | Present study |

| P. darjeelingensis | He 5913 | China | MT386384 | MT447420 | Present study |

| P. darjeelingensis | Chen 1018 | China | MT561709 | GQ470647 | Wu et al. (2010), present study |

| P. cf. dregeana | SFC 980804-4 | Korea | AF479669 | — | Lim and Jung (2003) |

| P. cf. dregeana | UOC-DAMIA-D46 | Sri Lanka | KP734203 | — | — |

| P. cf. dregeana | FLAS-F-60030 | United States | KY654737 | — | — |

| P. flavidoalba | FD-263 | United States | KP135402 | KP135271 | Floudas and Hibbett (2015) |

| P. flavidoalba | Miettinen 17896 | United States | KX752607 | KX752607 | Miettinen et al. (2016) |

| P. flavidoalba | CFMR4167 | United States | KX065957 | — | — |

| P. flavidoalba | HHB-4617 | United States | KP135401 | — | Floudas and Hibbett (2015) |

| P. friesii | He 5722 | Sri Lanka | MT452528 | MT447413 | Present study |

| P. friesii | He 5817 | Sri Lanka | MT452529 | MT447414 | Present study |

| P. friesii | He 5820 | Sri Lanka | MT452530 | MT447415 | Present study |

| P. gigantea | He 5290 | China | MT386381 | MT447416 | Present study |

| P. gigantea | Miettinen 15354 | Finland | KX752605 | — | Miettinen et al. (2016) |

| P. gigantea | CBS 935.70 | Germany | MH860011 | MH871798 | Vu et al. (2019) |

| P. gigantea | FP-70857-Sp | United States | KP135390 | KP135272 | Floudas and Hibbett (2015) |

| P. griseofuscescens | He 5734 | Sri Lanka | MT561708 | MT598032 | Present study |

| P. griseofuscescens | Cui 12629 | China | MT561718 | — | Present study |

| P. griseofuscescens | CLZhao 3692 | China | MT180946 | MT180950 | Xu et al. (2020) |

| P. griseofuscescens | CLZhao 3705 | China | MT180947 | MT180951 | Xu et al. (2020) |

| P. laxa | Wu 9311-17 | China | MT561710 | GQ470649 | Wu et al. (2010), present study |

| P. magnicystidiata | He 5648* | China | MT386377 | MT447409 | Present study |

| P. magnicystidiata | He 20140719_18 | China | MT561719 | — | Present study |

| P. magnicystidiata | Wu 890805-1 | China | MT561711 | GQ470667 | Wu et al. (2010) , present study |

| P. membranacea | He 3842 | China | MT386400 | MT447440 | Present study |

| P. membranacea | He 3849* | China | MT386401 | MT447441 | Present study |

| P. membranacea | He 6062 | China | MT386402 | MT447442 | Present study |

| P. pilatii | He 5114 | China | MT386385 | MT447421 | Present study |

| P. pilatii | He 5165 | China | MT386386 | MT447422 | Present study |

| P. pilatii | Dai 17041 | China | KY971603 | KY971604 | Wu et al. (2017) |

| P. pilatii | Spirin 5048 | Russia | KX752590 | KX752590 | Miettinen et al. (2016) |

| P. sinensis | He 4295 | China | MT386395 | MT447433 | Present study |

| P. sinensis | He 4665 | China | MT386396 | MT447434 | Present study |

| P. sinensis | He 4673* | China | MT386397 | MT447435 | Present study |

| P. sinensis | He 5662 | China | MT386398 | MT447436 | Present study |

| P. sp. | FP-102937 | United States | KP135391 | KP135270 | Floudas and Hibbett (2015) |

| P. sp. | ECS1971 | United States | KP135392 | — | Floudas and Hibbett (2015) |

| P. sp. | He 3827 | China | — | MT447437 | Present study |

| P. yunnanensis | He 2623 | China | MT386387 | MT447423 | Present study |

| P. yunnanensis | He 3249 | China | MT386375 | MT447425 | Present study |

| P. yunnanensis | CLZhao 3958 | China | MH744140 | MH744142 | Zhao et al. (2018) |

| P. yunnanensis | CLZhao 3990 | China | MH744141 | MH744143 | Zhao et al. (2018) |

| Pirex concentricus | OSC-41587 | United States | KP134984 | KP135275 | Floudas and Hibbett (2015) |

| Porostereum fulvum | LY: 18496 | France | MG649453 | MG649455 | — |

| P. spadiceum | CBS 474.48 | France | MH856438 | MH867984 | Vu et al. (2019) |

| Rhizochaete americana | FP-102188 | United States | KP135409 | KP135277 | Floudas and Hibbett (2015) |

| R. belizensis | FP-150712 | Belize | KP135408 | KP135280 | Floudas and Hibbett (2015) |

| R. brunnea | MR 229 | Argentina | AY219389 | AY219389 | Greslebin et al. (2004) |

| R. violascens | KHL 11169 | Norway | EU118612 | EU118612 | Larsson (2007) |

| R. filamentosa | HHB-3169-Sp | United States | KP135410 | KP135278 | Floudas and Hibbett (2015) |

| R. flava | PR 1141 | Puerto Rico | KY273030 | KY273033 | Nakasone et al. (2017) |

| R. fouqueriae | KKN-121-sp | United States | KY948786 | KY948858 | Justo et al. (2017) |

| R. radicata | FD-123 | United States | KP135407 | KP135279 | Floudas and Hibbett (2015) |

| R. sulphurina | HHB-5604 | United States | KY273031 | GU187610 | Binder et al. (2010) |

| R. sulphurosa | URM 87190 | Brazil | KT003522 | KT003519 | Chikowski et al. (2015) |

| Riopa metamorphosa | Spirin 2395 | Russia | KX752601 | KX752601 | Miettinen et al. (2016) |

| R. pudens | Cui 3238 | China | JX623931 | JX644060 | Jia et al. (2014) |

| Terana caerulea | FP-104073 | United States | KP134980 | KP135276 | Floudas and Hibbett (2015) |

| Outgroup | |||||

| Ceraceomyces serpens | HHB-15692-Sp | United States | KP135031 | KP135200 | Floudas and Hibbett (2015) |

| Phlebia acerina | FD-301 | United States | KP135378 | KP135260 | Floudas and Hibbett (2015) |

Species and sequences used in the phylogenetic analyses.

New species are set in bold with type specimens indicated with an asterisk (*).

Phylogenetic Analyses

Two separate datasets, the concatenated ITS-nrLSU sequences of species in the Phanerochaetaceae and ITS only sequences of Phlebiopsis, were analyzed. Ceraceomyces serpens (Tode) Ginns and Phlebia acerina Peck were selected as an outgroup for the ITS-LSU dataset, whilst Rhizochaete radicata (Henn.) Gresl., Nakasone & Rajchenb. was used in the ITS dataset (Floudas and Hibbett, 2015). For the concatenated dataset, the sequences of ITS and nrLSU were aligned separately using MAFFT v.74 (Katoh et al., 2017) with the G-INS-I iterative refinement algorithm, and optimized manually in BioEdit v.7.0.5.3. The separate alignments were then concatenated using Mesquite v.3.5.1 (Maddison and Maddison, 2018). The datasets were deposited in TreeBase5 (submission ID: 26529 for Phanerochaetaceae ITS-LSU, 26530 for Phlebiopsis ITS).

Maximum parsimony (MP), maximum likelihood (ML) analyses and Bayesian inference (BI) were carried out by using PAUP∗ v.4.0b10 (Swofford, 2002), RAxML v.8.2.10 (Stamatakis, 2014), and MrBayes 3.2.6 (Ronquist et al., 2012), respectively. In MP analysis, trees were generated using 100 replicates of random stepwise addition of sequence and tree-bisection reconnection (TBR) branch-swapping algorithm with all characters given equal weight. Branch supports for all parsimony analyses were estimated by performing 1000 bootstrap replicates with a heuristic search of 10 random-addition replicates for each bootstrap replicate. In ML analysis, statistical support values were obtained using rapid bootstrapping with 1000 replicates, with default settings used for other parameters. For BI, the best-fit substitution model was estimated with jModeltest v.2.17 (Darriba et al., 2012). Four Markov chains were run for five million and three million generations for the Phanerochaetaceae ITS-LSU and Phlebiopsis ITS datasets, respectively, until the split deviation frequency value was lower than 0.01. Trees were sampled every 100th generation. The first quarter of the trees, which represented the burn-in phase of the analyses, were discarded, and the remaining trees were used to calculate posterior probabilities (BPP) in the majority rule consensus tree.

Results

Phylogenetic Analyses

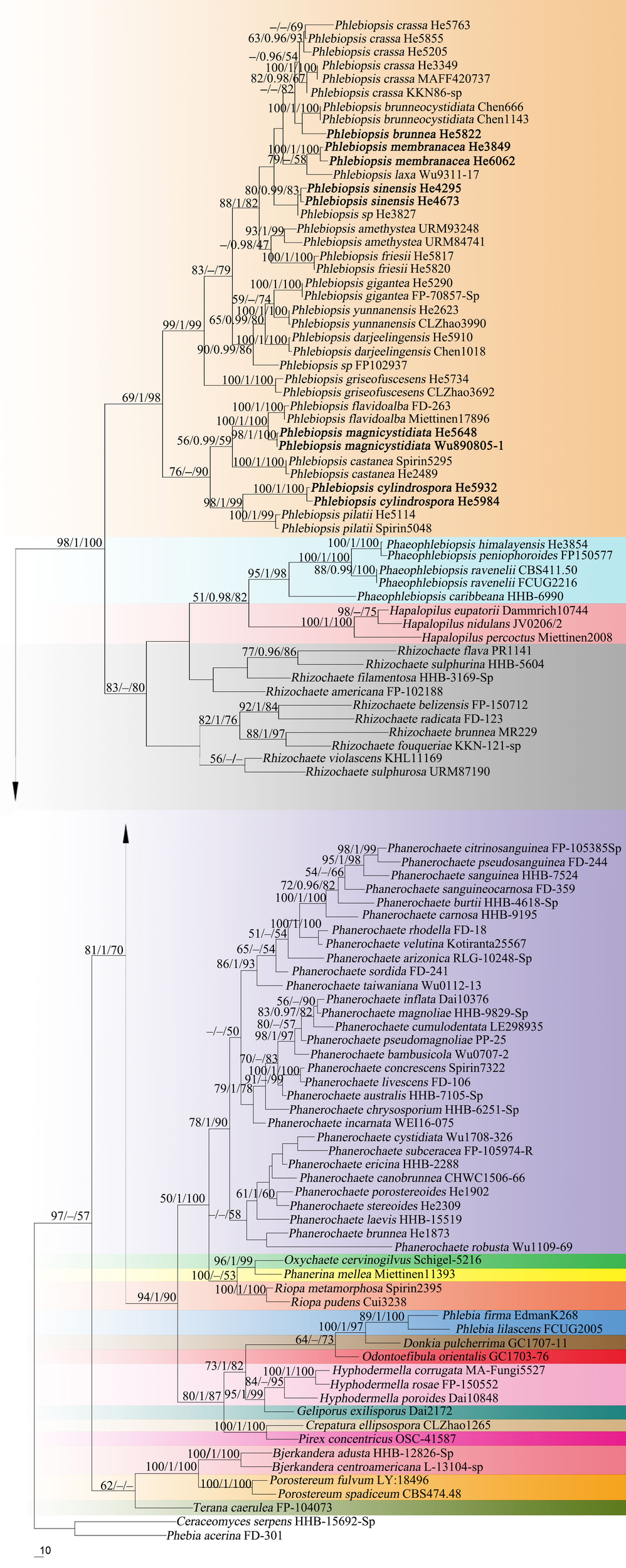

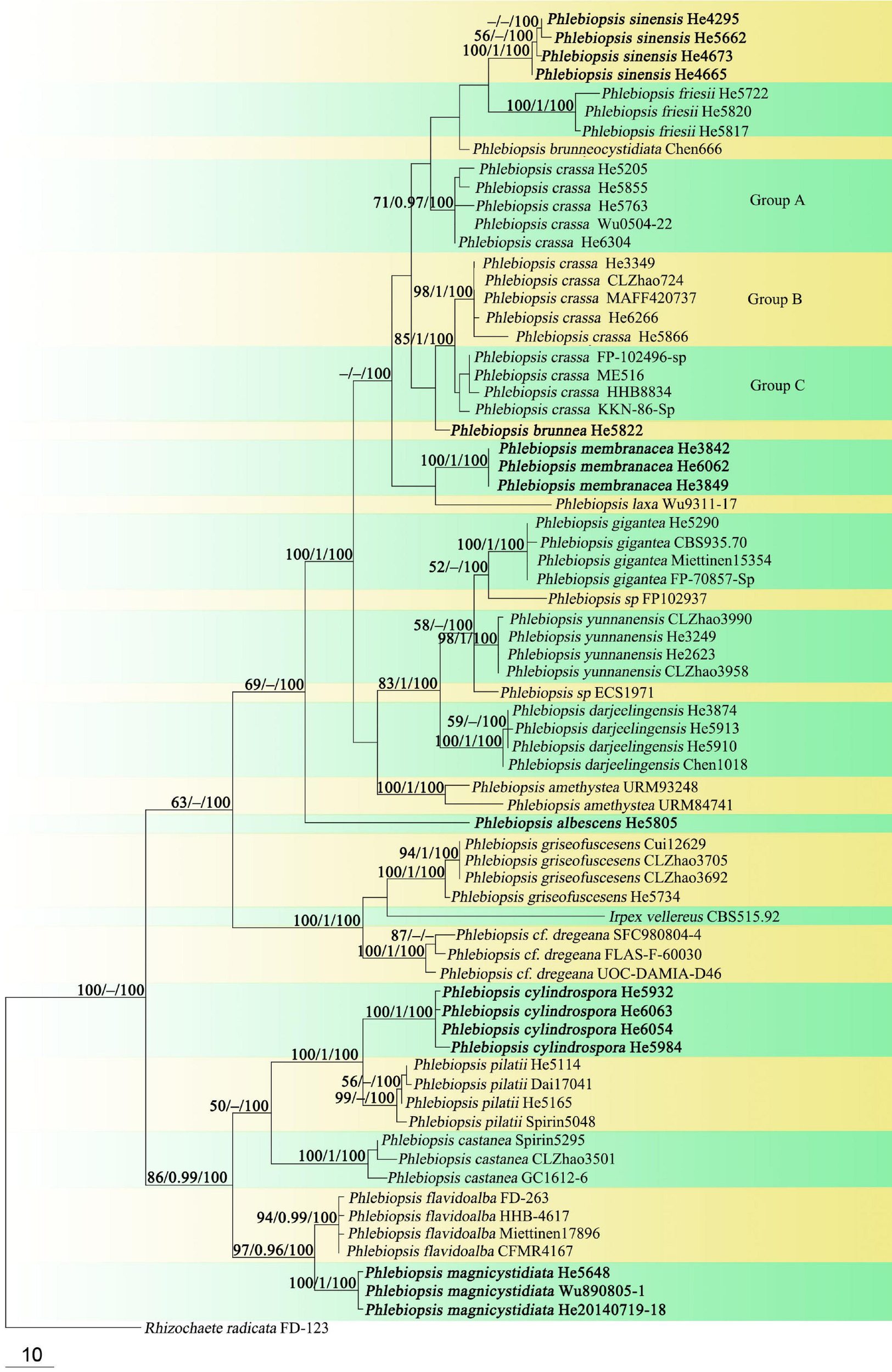

Forty-three ITS and 37 nrLSU sequences were generated for this study. The concatenated ITS-LSU dataset contained 101 ITS and 107 nrLSU sequences from 107 samples representing 86 Phanerochaetaceae taxa and the outgroup, while the ITS dataset contained 71 samples representing 21 Phlebiopsis s.s. taxa, a sample of Irpex vellereus and the outgroup (Table 1). The concatenated dataset had an aligned length of 2339 characters, of which 554 were parsimony-informative. MP analysis yielded one equally parsimonious tree (TL = 3603, CI = 0.360, RI = 0.695, RC = 0.250, HI = 0.640). The ITS dataset had an aligned length of 726 characters, of which 178 were parsimony-informative. MP analysis yielded 92 equally parsimonious trees (TL = 658, CI = 0.579, RI = 0.870, RC = 0.504, HI = 0.421). jModelTest suggested GTR + I + G and HKY + G were the best-fit models of nucleotide evolution for the concatenated ITS-LSU and ITS datasets, respectively. The average standard deviation of split frequencies of BI was 0.009223 and 0.007710 at the end of the run. ML and BI analyses resulted in almost identical tree topologies compared to the MP analysis. The MP trees are shown in Figures 1, 2 with the parsimony bootstrap values (≥50%, first), Bayesian posterior probabilities (≥0.95, second) and likelihood bootstrap values (≥50%, third) labeled along the branches.

FIGURE 1

Phylogenetic tree from maximum parsimony analysis from the concatenated ITS and nrLSU sequences of Phanerochaetaceae taxa. Branches are labeled with parsimony bootstrap values (≥50%, first), Bayesian posterior probabilities (≥0.95, second) and likelihood bootstrap values (≥50%, third). New species are set in bold.

FIGURE 2

Phylogenetic tree obtained from maximum parsimony analysis of ITS sequence data of Phlebiopsis. Branches are labeled with parsimony bootstrap values (≥50%, first), Bayesian posterior probabilities (≥0.95, second) and likelihood bootstrap values (≥50%, third). New species are set in bold.

In the Phanerochaetaceae ITS-LSU tree (Figure 1), Phlebiopsis, Phaeophlebiopsis, Hapalopilus, and Rhizochaete formed a strongly supported clade (98/1/100). Within this clade, the Phlebiopsis species clustered together with relatively strong support values (69/1/98), and species of Phaeophlebiopsis, Hapalopilus and Rhizochaete were in the sister subclades. In the Phlebiopsis ITS tree (Figure 2), 24 lineages were resolved including 21 taxa of Phlebiopsis and ‘Irpex vellereus.’ Samples of P. crassa were distributed in three distinct lineages. The six new species, P. albescens, P. brunnea, P. cylindrospora, P. magnicystidiata, P. membranacea and P. sinensis, formed distinct lineages.

Taxonomy

Phlebiopsis albescens Y.N. Zhao & S.H. He, sp. nov.

MycoBank: MB836023

Type – Sri Lanka, Avissawella, Salgala Forest, on fallen angiosperm twig, 3 March 2019, He 5805 (BJFC 030672, holotype; isotype in BJM).

Etymology – Refers to the white basidiomata.

Fruiting body – Basidiomata annual, resupinate, widely effused, closely adnate, inseparable from substrate, ceraceous to crustose, first as small patches, later confluent up to 15 cm long, 1 cm wide, up to 80 μm thick in section. Hymenophore smooth, white (6A1), orange white (6A2) to pale orange (6A3), unchanged in KOH, not cracking on drying; margin indistinct, concolorous with hymenophore. Context white.

Microscopic structures – Hyphal system monomitic; generative hyphae simple-septate. Subiculum indistinct to absent. Subhymenium well developed; hyphae colorless, thin- to slightly thick-walled, tightly agglutinated, 2.5–4 μm in diam. Lamprocystidia abundant, conical, colorless to pale yellow, thick-walled, heavily encrusted with crystals along entire length, embedded or slightly projecting beyond hymenium, with one or two secondary septa, with a basal simple septum, 25–40 × 8–12 μm (without encrustations). Basidia clavate to cylindrical, colorless, thin-walled, with a basal simple septum and four sterigmata, 10–16 × 3–4.5 μm; basidioles numerous, similar to basidia but slightly smaller. Basidiospores oblong ellipsoid to short cylindrical, colorless, thin-walled, smooth, IKI–, CB–, 3.5–5 × 2–2.2 (–2.5) μm, L = 4.4 μm, W = 2.1 μm, Q = 2.1 (n = 30/1).

Distribution – Sri Lanka.

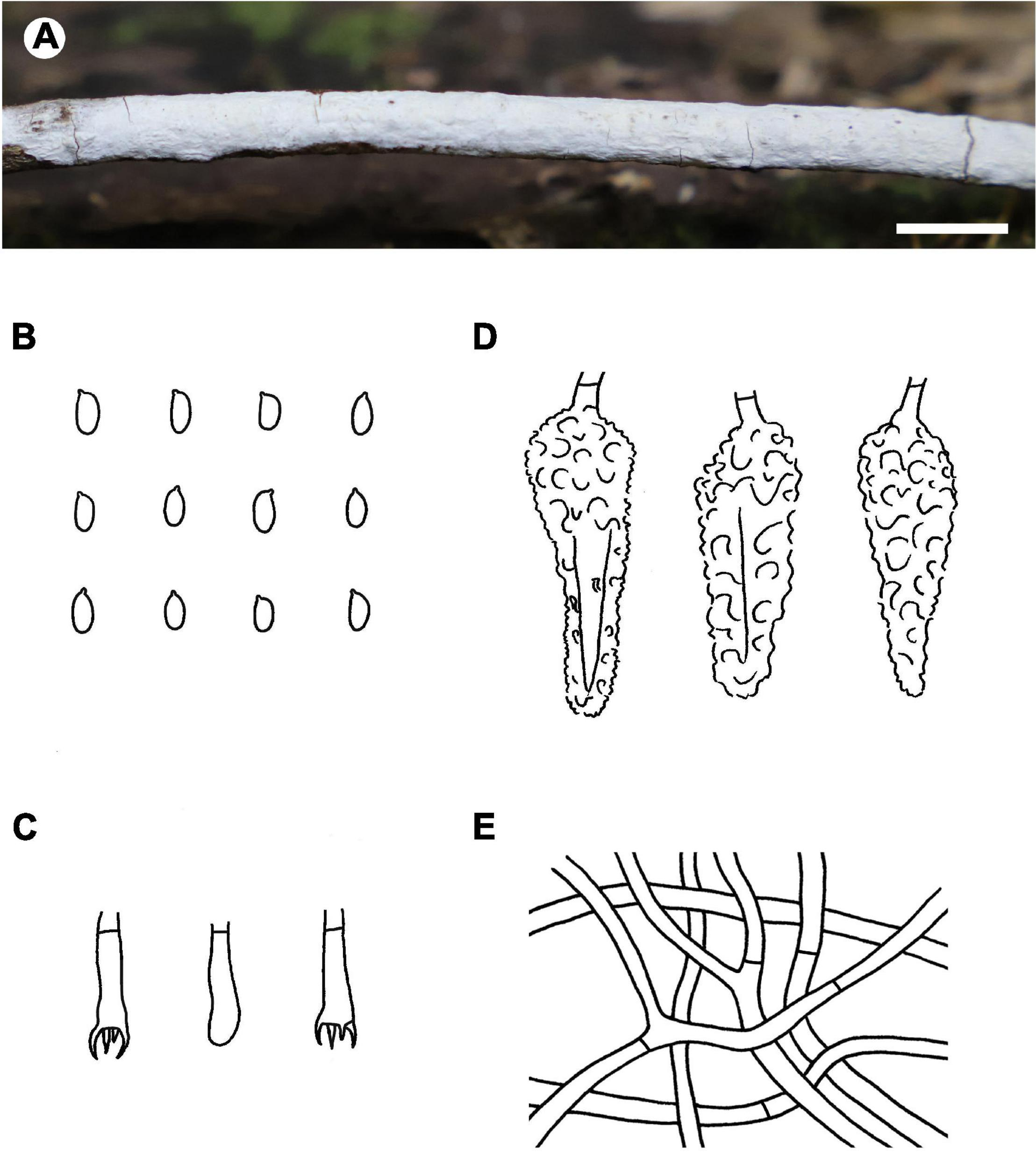

Notes – Phlebiopsis albescens (Figure 3) is characterized by thin, white to pale orange basidiomata, an indistinct subiculum, short lamprocystidia (<40 μm long) and basidia (<16 μm long), and small basidiospores (<5 μm long). Phlebiopsis punjabensis G. Kaur, Avn.P. Singh & Dhingra, from India, also has thin, white basidomata and short lamprocystidia, 20–36 × 7–9.8 μm, but larger basidiospores, 5.3–8.5 × 2.5–4 μm (Kaur et al., 2015). Another species with short basidiospores, P. yunnanensis C.L. Zhao, from southern China, has thicker basidiomata, 100–500 μm thick, with a smooth to odontoid hymenophore, and ellipsoid basidiospores, 2.5–3.5 μm wide (Zhao et al., 2018). In the ITS phylogenetic tree (Figure 2), P. albescens formed its lineage and was not closely related to any other species for current sequences.

FIGURE 3

Phlebiopsis albescens [from the holotype He 5805; scale bars: A = 1 cm, B–E = 10 μm]. (A) Basidiomata; (B) basidiospores; (C) basidia; (D) basidioles; (E) lamprocystidia.

Phlebiopsis brunnea Y.N. Zhao & S.H. He, sp. nov.

MycoBank: MB836024

Type – Sri Lanka, Western Province, Mitirigala Nissarana Vanaya Forest Monastery, on fallen angiosperm branch, 4 March 2019, He 5822 (BJFC 030689, holotype; isotype in BJM).

Etymology – Refers to the brown context of basidiomata.

Fruiting body – Basidiomata annual, resupinate, widely effused, closely adnate, inseparable from substrate, coriaceous, developing as small patches then confluent, up to 20 cm long, 5 cm wide, up to 350 μm thick in section. Hymenophore smooth, brownish gray (6C2–6D2), brownish orange (6C3) to grayish brown (6D3), unchanged in KOH, not cracking on drying; margin thinning out, indistinct, concolorous or darker than hymenophore. Context pale brown.

Microscopic structures – Hyphal system pseudodimitic; generative hyphae simple-septate. Subiculum well-developed, a non-agglutinated, loosely interwoven tissue; skeletocystidia (skeletal hyphae) brown, distinctly thick-walled, slightly encrusted, up to 120 μm long, 14 μm wide; hyphae colorless to pale yellowish brown, thick-walled, smooth, moderately branched at right angles, frequently septate, 2–5 μm in diam. Subhymenium thin; skeletocystidia as in subiculum but shorter and more heavily encrusted; generative hyphae colorless, thin- to thick-walled, moderately branched, frequently septate, loosely interwoven, 2–4.5 μm in diam. Lamprocystidia subulate to fusiform, colorless, thin- to thick-walled, distal end encrusted with small crystals, projecting up to 30 μm beyond hymenium, with an obtuse or acute tip, with a basal simple septum, 35–65 × 7–12 μm. Basidia clavate to subcylindrical, colorless, thin-walled, with a basal simple septum and four sterigmata, 20–33 × 4.5–6 μm; basidioles numerous, similar to basidia but slightly smaller. Basidiospores oblong ellipsoid to subcylindrical, colorless, thin-walled, smooth, IKI–, CB–, 6.5–7.5 (–8) × 3–3.6 (–4) μm, L = 7.3 μm, W = 3.3 μm, Q = 2.2 (n = 30/1).

Distribution – Sri Lanka.

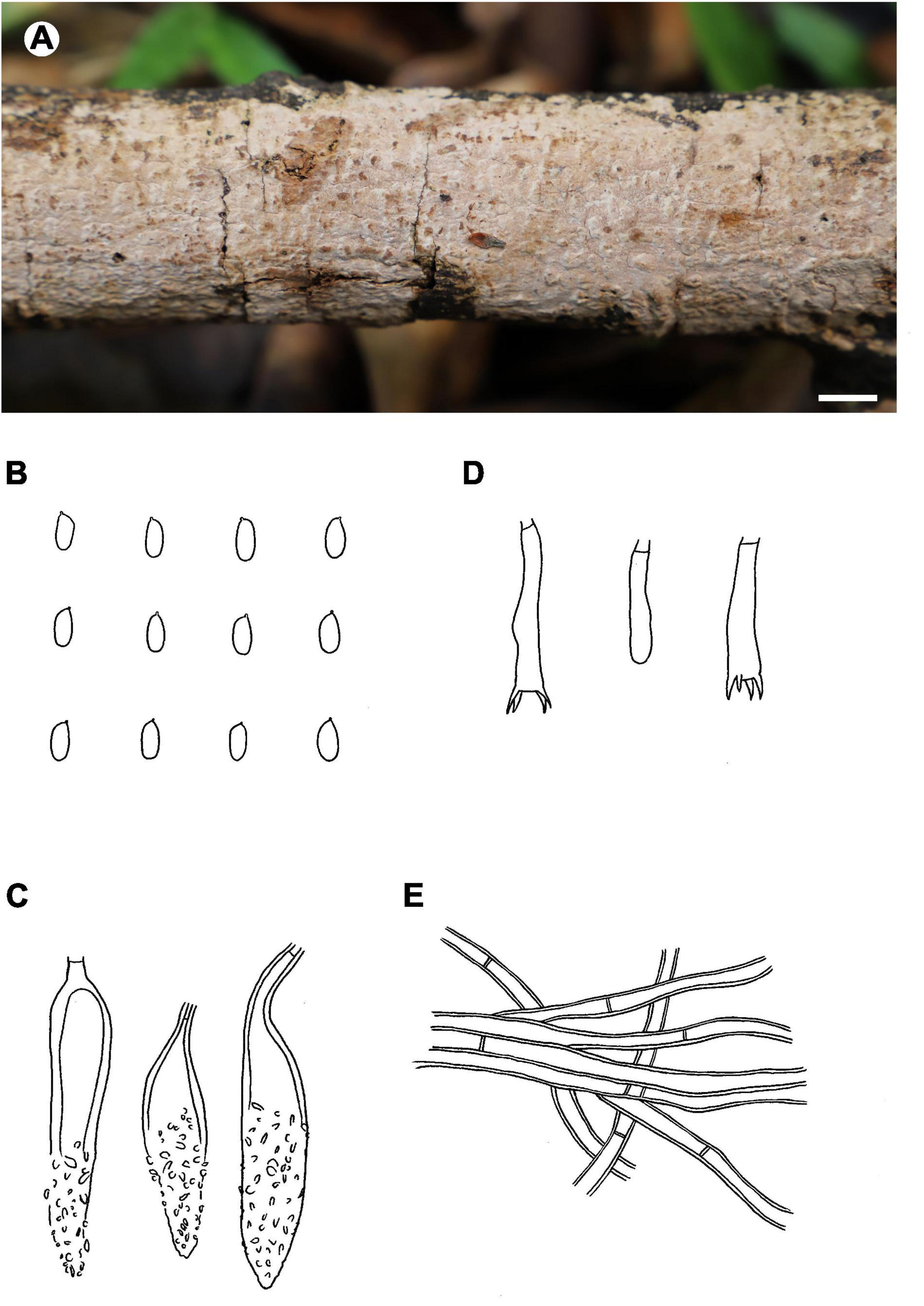

Notes – Phlebiopsis brunnea (Figure 4) is characterized by a coriaceous basidiomata with a smooth hymenophore and brown context, abundant, brown skeletocystidia in the subiculum and subhymenium, lamprocystidia, and oblong ellipsoid to subcylindrical basidiospores. Hjortstamia bambusicola (Berk. & Broome) Hjortstam & Ryvarden is similar with its grayish brown hymenophore and pseudodimitic hyphal system with brown skeletocystidia but with narrower basidiospores (2.5–3 μm wide) and grows on bamboo in Australia (Hjortstam and Ryvarden, 2005). Phlebiopsis brunneocystidiata (Sheng H. Wu) Miettinen has narrower lamprocystidia (5–8 μm wide) with brown walls and a host preference for Pandanaceae in Taiwan (Wu, 2004). Another similar species, P. crassa differs from P. brunnea by having effused-reflexed basidiomata with a more or less purple hymenophore and larger lamprocystidia, 50–120 × 8–20 μm (Burdsall, 1985; Hjortstam and Ryvarden, 1990). Phlebiopsis brunnea formed weakly supported sister lineages to P. brunneocystidiata or P. crassa group B and C in the ITS-LSU and ITS trees, respectively (Figures 1, 2).

FIGURE 4

Phlebiopsis brunnea (from the holotype He 5822; scale bars: A = 1 cm, B–E = 10 μm). (A) Basidiomata; (B) basidiospores; (C) lamprocystidia; (D) basidia and basidiole; (E) hyphae from subiculum.

Phlebiopsis cylindrospora Y.N. Zhao & S.H. He, sp. nov.

MycoBank: MB836025

Type – China, Hainan Province, Lingshui County, Diaoluoshan Nature Reserve, on dead, small diameter bamboo, 2 July 2019, He 5984 (BJFC 030860, holotype; isotype in BJM).

Etymology – Refers to the cylindrical basidiospores.

Fruiting body – Basidiomata annual, resupinate, widely effused, closely adnate, inseparable from substrate, coriaceous, first as small patches, later confluent up to 20 cm long, 4 cm wide, up to 150 μm thick in section. Hymenophore smooth, orange white (6A2), orange gray (6B2) to grayish orange (6B3), turning purple in KOH, not cracking on drying; margin thinning out, indistinct, slightly fimbriate, paler than or concolorous with hymenophore. Context gray.

Microscopic structures – Hyphal system monomitic; generative hyphae simple-septate. Subiculum distinct, a somewhat agglutinated, compact tissue, arranged more or less parallel to substrate; hyphae colorless, thick-walled, encrusted with yellow, resinous granules, infrequently branched, moderately septate, 2–4.5 μm in diam. Subhymenium indistinct; hyphae thin- to slightly thick-walled, heavily encrusted with yellow, resinous granules, frequently septate, more or less agglutinated, 2–4 μm in diam. Lamprocystidia numerous, subfusiform, colorless, thick-walled, apically encrusted with small crystals, embedded or slightly projecting beyond hymenium, 20–36 (–40) × 5–9 μm. Basidia clavate to subcylindrical, colorless, thin-walled, with a basal simple septum and four sterigmata, 12–16 × 4–5 μm; basidioles numerous, similar to basidia but slightly smaller. Basidiospores cylindrical, colorless, thin-walled, smooth, IKI–, CB–, (5–) 5.5–7.5 (–8) × 1.8–2.8 (–3) μm, L = 5.9 μm, W = 2.2 μm, Q = 2.4–3.1 (n = 90/3).

Additional specimens examined – China, Hainan Province, Qiongzhong County, Limushan Nature Reserve, on fallen angiosperm twig, 8 June 2016, He 3831 (BJFC 022333); on dead, small diameter bamboo, 8 June 2016, He 3882 (BJFC 022384, CFMR); Wuzhishan County, Wuzhishan Nature Reserve, on dead, small diameter bamboo, 10 June 2016, He 3926 (BJFC 022428); 30 June 2019, He 5922 (BJFC 030797), He 5932 (BJFC 030807), He 5936 (BJFC 030811) & He 5938 (BJFC 030813); Lingshui County, Diaoluoshan Nature Reserve, on dead, small diameter bamboo, 2 July 2019, He 5981 (BJFC 030857); 5 July 2019, He 6054 (BJFC 030930), He 6061 (BJFC 030937) & He 6063 (BJFC 030939); on fallen angiosperm branch, 5 July 2019, He 6038 (BJFC 030914). Thailand, Chiang Rai, Doi Pui, on rotten bamboo, 23 July 2016, He 4080 (BJFC 023521), He 4083 (BJFC 023524) & He 4094 (BJFC 023535, CFMR).

Distribution – China and Thailand.

Notes – Phlebiopsis cylindrospora (Figure 5) is characterized by pale-colored, smooth hymenophore that turns purple in KOH, a monomitic hyphal system with generative hyphae encrusted with yellow, resinous granules, small subfusiform lamprocystidia, cylindrical basidiospores, and habit on bamboo and woody angiosperms. It is similar to P. punjabensis that also has a pale-colored, smooth hymenophore and short lamprocystidia, but the latter species does not react with KOH and develops longer basidia (14–26 μm long), and slightly larger basidiospores (5.3–8.5 × 2.5–4 μm, Kaur et al., 2015). Phlebiopsis albescens differs from P. cylindrospora by its white hymenophore that is unchanged in KOH and distinctly smaller basidiospores (3.5–5 × 2–2.2 μm). The hymenophore in P. friesii (Lév.) Spirin & Miettinen turns purple in KOH also but is distinct from P. cylindrospora by having effused-reflexed basidiomata, a pseudodimitic hyphal system, and larger lamprocystidia, up to 80 × 20 μm (Hjortstam and Ryvarden, 1990). Although the phylogenetic trees (Figures 1, 2) show that P. cylindrospora and P. pilatii are closely related, the latter species is distinct morphologically for it lacks lamprocystidia and develops finely branched dendrohyphidia and larger basidiospores, 8–10 × 4–4.5 μm (Parmasto, 1965; Larsen and Gilberston, 1977; Duhem and Michel, 2009).

FIGURE 5

Phlebiopsis cylindrospora (from the holotype He 5984; scale bars: A = 1 cm, B–E = 10 μm). (A) Basidiomata; (B) basidiospores; (C) basidia and basidiole; (D) lamprocystidia; (E) hyphae from subiculum.

Phlebiopsis magnicystidiata Y.N. Zhao & S.H. He, sp. nov.

MycoBank: MB836026

Type – China, Hunan Province, Guzhang County, Gaowangjie Nature Reserve, on dead angiosperm branch, 4 August 2018, He 5648 (BJFC 026710, holotype; isotype in BJM).

Etymology – Refers to the large lamprocystidia.

Fruiting body – Basidiomata annual, resupinate, widely effused, closely adnate, inseparable from substrate, ceraceous to coriaceous, up to 15 cm long, 5 cm wide, up to 400 μm thick in section. Hymenophore smooth to slightly odontoid with scattered tubercles, pruinose from projecting cystidia, grayish orange [6B(3–5)], brownish orange [6C(3–5)] to light brown [6D(4–6)], unchanged in KOH, sometimes sparsely and deeply cracked with age; margin thinning out, indistinct, concolorous with hymenophore. Context white.

Microscopic structures – Hyphal system monomitic; generative hyphae simple-septate. Subiculum indistinct to absent. Subhymenium thickening, well-developed; hyphae colorless, thin- to slightly thick-walled, frequently septate, slightly agglutinated, vertically arranged, 2–4.5 μm in diam. Lamprocystidia numerous, fusiform to subulate, colorless, thick-walled, heavily encrusted with crystals, embedded or projecting beyond hymenium up to 40 μm, with a basal simple septum, apex subacute, 40–80 × (7–) 9–13 (–15) μm (without encrustations). Basidia clavate, colorless, thin-walled, with a basal simple septum and four sterigmata, 20–30 × 5–6 μm; basidioles numerous, similar to basidia but slightly smaller. Basidiospores broadly ellipsoid to subglobose, colorless, thin-walled, smooth, IKI–, CB–, 4.5–6.5 (–6.8) × (3.5–) 3.8–4.8 μm, L = 5.6 μm, W = 4.3 μm, Q = 1.3–1.4 (n = 60/2).

Additional specimens examined – China, Yunnan Province, Mengla County, Wangtianshu Forest Park, on fallen angiosperm branch, 19 July 2014, He 20140719-18 (BJFC 019145); Taiwan Province, Taichung, Tunghai University, on dead branch of Cassia siamea, 5 August 1989, Wu 890805-1 (TNM F0022186).

Distribution – Hunan, Yunnan, and Taiwan Provinces in southern China.

Notes – Phlebiopsis magnicystidiata (Figure 6) is characterized by large lamprocystidia and broadly ellipsoid to subglobose basidiospores. It is morphologically similar to and phylogenetically closely related to P. flavidoalba (Cooke) Hjortstam (Figures 1, 2) that has smooth hymenophore, slightly longer ellipsoid basidiospores (6–7.5 μm long) and a distribution in North and South America (Burdsall, 1985; Gilbertson and Blackwell, 1985). Phlebiopsis gigantea and P. magnicystidiata have similar lamprocystidia but the former differs in its well-developed subiculum, narrowly ellipsoid basidiospores, 5–7 × 2.5–3.5 μm, and often occurs on gymnospermous wood in the North Hemisphere (Eriksson et al., 1981; Bernicchia and Gorjón, 2010). Except for developing a distinct subiculum, P. darjeelingensis and P. magnicystidiata have similar sized lamprocystidia, basidia, and basidiospores (Dhingra, 1987). Reports of P. flavidoalba from India (Rattan, 1977) and Taiwan (Wu, 1990) need to be confirmed for they may be P. magnicystidiata instead.

FIGURE 6

Phlebiopsis magnicystidiata (A from He 20140719-18, B–E from the holotype He 5648; scale bars: A = 1 cm, B–E = 10 μm). (A) Basidiomata; (B) basidiospores; (C) basidia and basidiole; (D) lamprocystidia; (E) hyphae from subiculum.

Phlebiopsis membranacea Y.N. Zhao & S.H. He, sp. nov.

MycoBank: MB836027

Type – China, Hainan Province, Qiongzhong County, Limushan Nature Reserve, on dead, small diameter bamboo, 8 June 2016, He 3849 (BJFC 022351, holotype; isotype in BJM).

Etymology – Refers to the membranaceous basidiomata.

Fruiting body – Basidiomata annual, resupinate, widely effused, adnate, separable from substrate, membranaceous, up to 20 cm long, 5 cm wide, up to 250 μm thick in section. Hymenophore smooth, orange white (6A2), orange gray (6B2), grayish orange [6B(3–5)] to brownish orange [6C(3–5)], unchanged in KOH, sometimes sparsely and finely cracked with age; margin thinning out, fimbriate, concolorous with hymenophore. Context gray.

Microscopic structures – Hyphal system pseudodimitic; generative hyphae simple-septate. Subiculum well-developed, a non-agglutinated, loosely interwoven tissue; skeletocystidia abundant, fusiform to clavate, brown, thick-walled, smooth, with an acute or obtuse apex, embedded, (30–) 40–70 × 8–15 μm; hyphae colorless, moderately to distinctly thick-walled, smooth, rigid, frequently branched at right angles, frequently septate, 3–5 μm in diam. Subhymenium thin; hyphae colorless, thin-walled, smooth, somewhat agglutinated, interwoven, 2–4.5 μm in diam. Hymenial cystidia scattered, similar to skeletocystidia in shape and size but with paler, thinner walls, and sparse encrustations at apex. Basidia clavate, colorless, thin-walled, with a basal simple septum and four sterigmata, 15–22 × 4–5 μm; basidioles numerous, similar to basidia but slightly smaller. Basidiospores oblong ellipsoid to subcylindrical, colorless, thin-walled, smooth, IKI–, CB–, 4.2–6.2 (–6.8) × 2–3 (–3.2) μm, L = 5.5 μm, W = 2.6 μm, Q = 1.9–2.3 (n = 90/3).

Additional specimens examined – China, Hainan Province, Qiongzhong County, Limushan Nature Reserve, on dead, small diameter bamboo, 8 June 2016, He 3842 (BJFC 022344); Lingshui County, Diaoluoshan Nature Reserve, on dead, small diameter bamboo, 5 July 2019, He 6062 (BJFC 030938).

Distribution – Hainan Province, southern tropical China.

Notes – Phlebiopsis membranacea (Figure 7) is characterized by membranaceous basidiomata with well-developed subicula, brown, smooth, thick-walled skeletocystidia, without lamprocystidia, and habit on bamboo in tropical China. Like P. membranacea, Hjortstamia novae-granatae (A.L. Welden) Hjortstam & Ryvarden, from Columbia, grows on bamboo but its brown, smooth skeletocystidia are tubular in shape and its basidiospores are larger, 5.5–7 × 3–4 μm (Hjortstam and Ryvarden, 1990). Phlebiopsis laxa (Sheng H. Wu) Miettinen like P. membranacea has membranaceous basidiomata and loosely arranged subicular hyphae but differs in having lamprocystidia and larger basidiospores, 8–10 × 4–5 μm (Wu, 2000). In the phylogenetic trees (Figures 1, 2), P. membranacea is sister to P. laxa, though their relationship is not strongly supported.

FIGURE 7

Phlebiopsis membranacea (A from He 3842, B–E from the holotype He 3849; scale bars: A = 1 cm, B–E = 10 μm). (A) Basidiomata; (B) basidiospores; (C) basidia and basidiole; (D) hymenial cystidia; (E) hyphae from subiculum.

Phlebiopsis sinensis Y.N. Zhao & S.H. He, sp. nov.

MycoBank: MB836028

Type – China, Sichuan Province, Wanyuan County, Huaeshan Nature Reserve, on fallen angiosperm branch, 17 July 2013, He 4673 (BJFC 024192, holotype; isotype in BJM).

Etymology – Refers to the distribution in China.

Fruiting body – Basidiomata annual, resupinate to effused-reflexed with reflexed edges elevated and incurved with age, loosely adnate, easily detached from substrate, coriaceous, first as small patches, later confluent up to 15 cm long, 5 cm wide, up to 300 μm thick in section. Pileus projecting up to 1.5 mm; upper surface gray, slightly sulcate. Hymenophore smooth, brownish orange [6C(3–5)], grayish brown [6(D–F)3] to brown [6E(4–6)], unchanged in KOH, sometimes finely cracked with age; margin thinning out, distinct, white to gray, silky, slightly fimbriate, up to 1 mm wide. Context gray to yellowish brown.

Microscopic structures – Hyphal system pseudodimitic; generative hyphae simple-septate. Tomentum and cortex (a dark line between the tomentum and subiculum) present. Subiculum well-developed, a non-agglutinated tissue; skeletocystidia brown, thick-walled, encrusted at apex, embedded, intermediate forms between skeletocystidia and lamprocystidia observed; hyphae colorless to pale yellow, moderately to distinctly thick-walled, smooth, rarely branched, moderately septate, easily separated, more or less parallel to substrate, 3–6 μm in diam. Subhymenium indistinct. Lamprocystidia abundant, broadly fusiform to broadly subulate, usually with a long, curved stalk and resembling skeletocystidia, colorless to brown, thick-walled, heavily encrusted, 30–60 × 8–13 μm, projecting up to 30 μm. Basidia clavate, colorless, thin-walled, with a basal simple septum and four sterigmata, 20–30 × 4.5–5.5 μm; basidioles numerous, similar to basidia but slightly smaller. Basidiospores oblong ellipsoid to subcylindrical, colorless, thin-walled, smooth, IKI–, CB–, (5–) 5.8–7.8 (–8) × (2.2–) 2.5–3.5 (–3.8) μm, L = 6.4 μm, W = 2.9 μm, Q = 2.1–2.4 (n = 90/3).

Additional specimens examined – China, Gansu Province, Pingliang County, Kongtongshan Nature Reserve, on construction wood, 3 August 2015, He 2416 (BJFC 020870, CFMR); Hubei Province, Wufeng County, Houhe Nature Reserve, on dead angiosperm branch, 16 August 2017, He 5081 (BJFC 024599); Hunan Province, Yongshun County, Xiaoxi Nature Reserve, on dead angiosperm branch, 6 August 2018, He 5662 (BJFC 026724); Inner Mongolia, Chifeng, Aohan County, Daheishan Nature Reserve, on fallen Quercus mongolia branch, 3 September 2015, Tiezhi Liu et al. (CFSZ 10714), on fallen Pinus tabuliformis branch, 19 September 2016, Tiezhi Liu et al. (CFSZ 12436); Jiangxi Province, Ji’an County, Jinggangshan Nature Reserve, on dead Rhododendron branch, 11 August 2016, He 4295 (BJFC 023737, CFMR); Liaoning Province, Zhuanghe County, Xianrendong Forest Park, on dead Quercus branch, 5 August 2017, He 4665 (BJFC 024184); Shaanxi Province, Foping County, Foping Nature Reserve, on fallen Betula branch, 11 September 2013, He 1907 (BJFC 016374); Sichuan Province, Baoxing County, Fengtongzhai Nature Reserve, on fallen angiosperm trunk, 18 September 2012, He 20120918-3 (BJFC 014609).

Distribution – Gansu, Hubei, Hunan, Jiangxi, Liaoning, Shaanxi and Sichuan Provinces and Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region of China.

Notes – Phlebiopsis sinensis (Figure 8) is characterized by effused to effused-reflexed, coriaceous basidiomata with well-developed subicula, brown skeletocystidia, lamprocystidia, and a temperate distribution. Submembranaceous-pellicular basidiomata, narrower cystidia (5–8 μm wide), and a tropical distribution distinguish P. brunneocystidiata from P. sinensis (Wu, 2004). Both P. crassa and P. sinensis develop effused-reflexed basidiomata, but the former species has a purple-tinted hymenophore, larger lamprocystidia, 50–120 × 8–20 μm, and a tropical distribution (Hjortstam and Ryvarden, 1990). Although the ITS tree (Figure 2) shows that P. sinensis and P. friesii are sister taxa, P. friesii is distinct morphologically with a hymenophore that turns purple in KOH and has a dimitic hyphal system with colorless to yellow skeletal hyphae (Hjortstam and Ryvarden, 1990).

FIGURE 8

Phlebiopsis sinensis (from He 4673; scale bars: A = 1 cm, B–E = 10 μm). (A) Basidiomata; (B) basidiospores; (C) basidia and basidiole; (D) lamprocystidia; (E) hyphae from subiculum.

Phaeophlebiopsis mussooriensis (Priyanka, Dhingra & N. Kaur) Nakasone & S.H. He, comb. nov.

MycoBank: MB836029

Synonym: Phlebiopsis mussooriensis Priyanka, Dhingra & N. Kaur, Mycotaxon 115: 255, 2011.

Notes – This species is characterized by a grayish yellow hymenophore, well-developed subiculum, thin-walled generative hyphae, lamprocystidia, and ellipsoid basidiospores (Priyanka et al., 2011). As mentioned in the protolog, P. mussooriensis is quite similar to P. himalayensis, now Phaeophlebiopsis himalayensis (Dhingra) Zmitr., differing primarily in basidiospore size and color change of hymenophore in KOH. Based on Priyanka et al.’s 2011 description, illustration, and comments, we propose the transfer of P. mussooriensis into Phaeophlebiopsis.

Phlebiopsis bambusicola (Berk. & Broome) Nakasone & S.H. He, comb. nov.

MycoBank: MB836030

Synonyms: Corticium bambusicola Berk. & Broome, Transactions of the Linnaean Society of London 2: 64, 1882. Peniophora bambusicola (Berk. & Broome) Sacc., Sylloge Fungorum 6: 647, 1888. Hjortstamia bambusicola (Berk. & Broome) Hjortstam & Ryvarden, Synopsis Fungorum 20: 37, 2005.

Notes – This Australian species is known only from the type and is characterized by a grayish brown hymenophore, a dimitic hyphal system, large, brown skeletocystidia, lamprocystidia, narrowly ellipsoid to allantoid basidiospores, and a habit on bamboo (Hjortstam and Ryvarden, 2005). Although similar to P. crassa, P. bambusicola has narrower basidiospores, 2.5–3 μm broad and is restricted by host preference and distribution.

Phlebiopsis dregeana (Berk.) Nakasone & S.H. He, comb. nov.

MycoBank: MB836031

Synonyms: Corticium dregeanum Berk., London Journal of Botany 5: 3, 1846. Hymenochaete dregeana (Berk.) Massee, Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 27: 114, 1890. Terana dregeana (Berk.) Kuntze, Revisio generum plantarum 2: 872, 1891. Lopharia dregeana (Berk.) P.H.B. Talbot, Bothalia 6: 57, 1951. Irpex dregeanus (Berk.) P.H.B. Talbot, Bothalia 6: 344, 1954. Australohydnum dregeanum (Berk.) Hjortstam & Ryvarden, Synopsis Fungorum 4: 61, 1990.

Notes – This is a poorly understood species that has been interpreted differently by various researchers. We take a narrow concept of P. dreageana based on studies of the type specimen and specimens restricted to Africa as described and illustrated by Massee (1891), Talbot (1951), Reid (1975), and Hjortstam and Ryvarden (1990). The ellipsoid basidiospores based on these studies are approximately 6.5–8 × 4–5 μm in size. Note that the cylindrical basidiospores illustrated by Reid (1975) are questionable for Hjortstam (1989) noted that basidia and spores were not observed in the type. Hjortstam and Ryvarden (1990) took a broad interpretation of A. dreageanum when they placed Hydnum griseofuscescens Reichardt from Australia and Irpex vellereus Berk. & Broome from Sri Lanka in synonymy; see below for further discussion of these two taxa. Although A. dregeanum has since been reported from India (De, 1998, as Oxyporus vellereus), South Korea (Lim, 2001; Lim and Jung, 2003), New Zealand (Buchanan and Ryvarden, 2000), Portugal (Melo and Hjortstam, 2002), Israel (Ţura et al., 2011), and Italy (Saitta et al., 2014), the basidiospore size, when given, is significantly smaller than the African collections.

Sequences from authentic specimens of the species are not available at present, but ITS sequences labeled “Australohydnum dregeanum” in GenBank, from United States, Korea and Sri Lanka, formed a strongly supported lineage within Phlebiopsis (Figure 2). The identity of the taxa in this lineage needs further study.

Phlebiopsis griseofuscescens (Reichardt) Nakasone & S.H. He, comb. nov.

MycoBank: MB836032

Synonyms: Hydnum griseofuscescens Reichardt, Verhandlungen der Zoologisch-Botanischen Gesellschaft Wien 16: 374, 1866. Irpex griseofuscescens (Reichardt) D.A. Reid, Kew Bulletin 17 (2): 273, 1963. Australohydnum griseofuscescens (Reichardt) Jülich, Persoonia 10 (1): 138, 1978. Irpex vellereus Berk. & Broome, Journal of the Linnean Society. Botany 14: 61, 1875. Xylodon vellereus (Berk. & Broome) Kuntze, Revisio generum plantarum 3 (2): 541, 1898. Hirschioporus vellereus (Berk. & Broome) Teng, Zhong Guo De Zhen Jun [Fungi of China]: 761, 1963. Oxyporus vellereus (Berk. & Broome) A. Roy & A.B. De, J. Mycopathol. Res.: 41, 1998. Phlebiopsis lacerata C.L. Zhao, Phytotaxa 440 (4): 274, 2020. Hydnochaete philippinensis Lloyd (as “philippensis”), Mycological Writings 7 (67): 1154, 1922. Trichaptum venustum (Berk.) G. Cunn., Bulletin of the New Zealand Department of Scientific and Industrial Research 164: 97, 1965.

Specimens examined – Sri Lanka, Western Province, Ingiriya, Dombagaskanda Forest Reserve, on fallen angiosperm branch, 27 February 2019, He 5734 (BJFC 030601). China, Sichuan Province, Miyi County, Haita Village, on fallen Quercus trunk, 13 September 2015, Cui 12629 (BJFC 028408) & Cui 12637 (BJFC 028416).

Notes – Hydnum griseofuscescens was described from Australia and is the type of Australohydnum (Jülich, 1978). It is characterized by resupinate to effused-reflexed basidiomata with a hydnoid, purplish brown hymenophore, a pseudodimitic hyphal system with simple-septate, colorless, generative hyphae, 4–9 μm broad, encrusted hymenial cystidia with colorless walls, and small ellipsoid basidiospores, 4–6 × 2.5–3 μm (Reid, 1956 as Irpex vellerus, Jülich, 1978). We follow Reid (1956, 1963) who determined that H. griseofuscescens and I. vellereus, described from Sri Lanka, were synonyms after studying the types of both species. Reid (1967) also reported that T. venustum sensu Cunningham (1965) is H. griseofuscescens. Based on morphological studies and sequence analyses, we determined that P. lacerata described from southern China (Xu et al., 2020) is conspecific with P. griseofuscescens.

Gilbertson and Adaskaveg (1993) described and illustrated I. griseofuscescens from Hawaii, but this species lacks encrusted hymenial cystidia and has small basidiospores, 4–4.5 × 2–2.5 μm. Similarly, De’s (1998) description of O. vellereus from India appears to represent a different species with a monomitic hyphal system of colorless to pale brown hyphae and cylindrical basidiospores, 5.2–7 × 2–3 μm. One of the specimens cited, VBMN 80451, is also at CBS, CBS 515.92, and its ITS sequence is available from GenBank (AF479670) as “Irpex vellereus.” This sequence was included in Lim and Jung (2003) and Figure 2, herein, where it is on a long branch, sister to P. griseofuscescens.

Phlebiopsis novae-granatae (A.L. Welden) Nakasone & S.H. He, comb. nov.

MycoBank: MB836033

Synonyms: Lopharia novae-granatae A.L. Welden [as ‘nova-granata’], Mycologia 67: 540, 1975. Porostereum novae-granatum (A.L. Welden) Hjortstam & Ryvarden [as ‘nova-granatum’], Synopsis Fungorum 4: 41, 1990. Phanerochaete novae-granatae (A.L. Welden) Sheng H. Wu [as ‘nova-granata’], Mycotaxon 88: 375, 2003. Hjortstamia novae-granatae (A.L. Welden) Hjortstam & Ryvarden [as ‘nova-granata’], Synopsis Fungorum 25: 19, 2008.

Notes – Reported from Colombia on bamboo, this species is characterized by a pale brown hymenophore and smooth skeletocystidia but lacking lamprocystidia (Welden, 1975; Hjortstam and Ryvarden, 1990). Because of its morphological similarity to P. crassa, the transfer of P. novae-granatae is proposed.

Phlebiopsis crassa Species Complex

Specimens examined – Phlebiopsis crassa group A: Vietnam, Ho Chi Minh City, the Botanical Garden Padua, on fallen angiosperm trunk, 13 October 2017, He 5205 (BJFC 024723). Sri Lanka, Central Province, Kandy, Peradeniya Botanic Garden, on fallen angiosperm branch, 2 March 2019, He 5763 (BJFC 030630). China, Guangdong Province, Renhua County, Danxiashan Nature Reserve, on fallen angiosperm trunk, 4 June 2019, He 5855 (BJFC 030730, Figure 9A); Yunnan Province, Qiubei County, Puzhehei Nature Reserve, 17 November 2019, He 6300 (BJFC, Figure 9C), He 6301 (BJFC, Figure 9D), He 6303 (BJFC, Figure 9B) & He 6304 (BJFC); Ximeng County, Mengsuolongtan Forest Park, on fallen angiosperm branch, 15 April 2005, Wu 0504-22 (TNM F0018719).

FIGURE 9

Basidiomata of Phlebiopsis crassa s.l. (A–D: P. crassa group A, E–H: P. crassa group B; scale bars: A–H = 1 cm). (A) He 5855; (B) He 6303; (C) He 6300; (D) He 6301; (E) He 6266; (F) He 5866; (G,H) He 3349.

Phlebiopsis crassa group B: China, Guangdong Province, Renhua County, Danxiashan Nature Reserve, on fallen angiosperm branch, 4 June 2019, He 5866 (BJFC 030741, Figure 9F); Yunnan Province, Lushui County, Gaoligongshan Nature Reserve, on fallen angiosperm trunk, 29 November 2015, He 3349 (BJFC 021744, Figures 9G,H); Maguan County, Gulinqing Nature Reserve, on fallen angiosperm branch, 14 November 2019, He 6266 (BJFC, Figure 9E).

Phlebiopsis crassa group C: United States, Arizona, Pima County, Santa Rita Experimental Range, on Fouquieria splendens, 31 July 1976, K.K. Nakasone, KKN-86-sp (CFMR); Illinois, Coles County, Fox Ridge State Park, on hardwood, 24 September 1990, A.S. Methven, FP-1024996-sp (CFMR); Mississippi, Harrison County, Harrison Experimental Forest, on Quercus sp., 26 March 1976, H.H. Burdsall, Jr., HHB-8834-sp (CFMR).

Notes – Our phylogenetic analyses showed that samples of P. crassa group A from Vietnam, Sri Lanka and southern China formed a distinct lineage and represent P. crassa s.s., for the type was described from Vietnam (Figures 1, 2). Collections from southern China and Japan, group B, and the United States, group C, clustered into two lineages in the ITS tree (Figure 2). All three lineages of P. crassa are morphologically similar, however. Unraveling this species complex is beyond the scope of this study, involving a number of presumed synonyms of P. crassa; see Lentz (1955) and Burdsall (1985).

Phlebiopsis darjeelingensis Dhingra, Nova Hedwigia 44: 222, 1987

Synonyms: Phanerochaete lamprocystidiata Sheng. H. Wu, Mycotaxon 90: 426, 2004. Phlebiopsis lamprocystidiata (Sheng H. Wu) Sheng H. Wu & Hallenb., Fungal Diversity 42: 116, 2010.

Notes – Because P. darjeelingensis, from India, and P. lamprocystidiata, from Taiwan, are nearly identical in morphology — basidiomata ceraceous when fresh then corneous when dried, well-developed subiculum of compactly packed, colorless hyphae, and cystidia and basidiospores of similar shape and size (Dhingra, 1987; Wu, 2004), we consider P. lamprocystidiata to be a later synonym of P. darjeelingensis. Zmitrovich (2018) transferred Phlebiopsis lamprocystidiata to Phaeophlebiopsis based on morphology, our phylogenetic analyses show that it belongs to Phlebiopsis s.s., however.

Discussion

The generic limits of Phlebiopsis has expanded over the last 40 years since its introduction in 1978 to include significant morphological range in basidiomata habit and texture and hymenophore configuration with the aid of molecular phylogenetic methods (Floudas and Hibbett, 2015; Miettinen et al., 2016; Zhao et al., 2018; Xavier de Lima et al., 2020; Xu et al., 2020). In this study, we emphasized sampling of Phlebiopsis taxa, and our overall results confirm those of Floudas and Hibbett (2015), Miettinen et al. (2016), and Chen et al. (2018b). In Figures 1, 2, Phlebiopsis, including the types of Australohydnum, P. griseofuscescens and Hjortstamia, P. friesii, formed a well-supported clade in the Phanerochaetaceae and is closely related to Phaeophlebiopsis, Hapalopilus and Rhizochaete. The genera Phlebiopsis and Australohydnum were published simultaneously (Jülich, 1978) but the former is favored to avoid unnecessary name changes. So, we propose that Australohydnum is a synonym of Phlebiopsis. Twenty-four lineages were resolved in the ITS tree of Phlebiopsis, among which 18 are accepted species, including the P. crassa species complex and six new species described herein. Further study is required to identify the taxa named P. cf. dregeana, Irpex vellerus, Phlebiopsis sp. FP-102937 and Phlebiopsis sp. ECS-1971.

Among the 24 names of Phlebiopsis in Index Fungorum (accessed on 21 January 2021), we accept 17 taxa in Phlebiopsis s.s., including 11 that are supported by molecular data. Five taxa, P. himalayensis Dhingra, P. mussooriensis, P. peniophoroides Gilb. & Adask., P. ravenelii (Cooke) Hjortstam, and P. roumeguerei (Bres.) Jülich & Stalpers were transferred to Phaeophlebiopsis based on morphology and sequence data. Phlebiopsis lacerata and P. lamprocystidiata are synonyms of P. griseofuscescens and P. darjeelingensis, respectively, as discussed above. Thus, 27 species of Phlebiopsis worldwide are accepted, including the six new species and four new combinations reported herein. An emended description of Phlebiopsis and an identification key to all species in the genus worldwide are presented below.

Phlebiopsis (Jülich) Nakasone & S.H. He, Emended

Synonyms: CastanoporusRyvarden, 1991 Synopsis Fungorum 5: 121, 1991. HjortstamiaBoidin and Gilles, 2003 Bulletin de la Société Mycologique de France 118 (2): 99, 2003. Australohydnum Jülich, Persoonia 10 (1): 138, 1978.

Description: Basidiomata annual, resupinate, effused, effused-reflexed or pileate, ceraceous, membranaceous to coriaceous. Pilei, when present, tomentose, gray to brown. Hymenophore smooth, tuberculate, odontoid, hydnoid to poroid, white, gray, grayish brown, purplish brown or brown, turning purple in KOH in two species. Hyphal system monomitic or dimitic; generative hyphae simple-septate, colorless or rarely pale brown, in dimitic species with skeletal or, in one species, micro-binding hyphae. Subiculum absent to well-developed, colorless, brown, agglutinated or not, compact to loosely interwoven. Skeletocystidia absent or present, colorless or brown, distinctly thick-walled, smooth or encrusted. Hymenial cystidia or lamprocystidia typically present, colorless or light brown, thick-walled, usually encrusted. Dendrohyphidia present in one species, colorless, thin-walled, smooth, branched. Basidia clavate or subcylindrical, with four sterigmata and a basal simple septum. Basidiospores cylindrical, ellipsoid, broadly ellipsoid or subglobose, colorless, thin-walled, smooth, negative in Melzer’s reagent, acyanophilous.

Type species: Phlebiopsis gigantea (Fr.) Jülich

Notes – The terminology relating to the cystidia observed in Phlebiopsis species is varied in the literature and thus confusing. There are up to three kinds of cystidia, but intermediate forms can develop to blur their distinctiveness. Lamprocystidia are found in most species of Phlebiopsis in the hymenium, often projecting, and may become embedded as the basidiomata thickens. They are typically conical or subfusiform with thick walls that are lightly to heavily encrusted in the upper half or apex. Skeletocystidia are found in dimitic or pseudodimitic species in which thick-walled hyphae in the subiculum curve toward the hymenium but remain embedded in the subiculum or subhymenium. The terminal ends may or may not be differentiated and usually lack encrustations. Hymenial cystidia are those structures that are similar to skeletocystidia but terminate in the hymenium and may be encrusted. In other cases, they are formed in the subhymenium and are smaller than lamprocystidia and not conical or heavily encrusted.

Key to 27 Phlebiopsis Species

1. Hymenophore poroid, irpicoid or hydnoid……………………… 2

1. Hymenophore smooth, tuberculate or odontoid……………… 4

2. Basidiomata resupinate; hymenophore poroid to irpicoid; on gymnosperms……………………………………………………… P. castanea

2. Basidiomata effused-reflexed; hymenophore hydnoid; on angiosperms……………………………………………………………………………. 3

3. Basidiospores 6.5–8 × 4–5 μm………………………..P. dregeana

3. Basidiospores 4.5–6 × 2.5–3 μm……………. P. griseofuscescens

4. Dendrohyphidia present………………………………………. P. pilatii

4. Dendrohyphidia absent…………………………………………………… 5

5. Hyphal system pseudodimitic or dimitic…………………………. 6

5. Hyphal system monomitic…………………………………………….. 13

6. Hymenophore turning purple in KOH………………….. P. friesii

6. Hymenophore unchanged in KOH…………………………………. 7

7. Basidiomata with well-developed pilei; skeletocystidia absent……………………………………………………………………… P. papyrina

7. Basidiomata resupinate to effused-reflexed; skeletocystidia present…………………………………………………………………………………….. 8

8. Hymenophore without purple tints…………………………………. 9

8. Hymenophore with purple tint………………………………………. 12

9. Lamprocystidia none; basidiospores ≤ 6 μm long…………………………………………………………………. P. membranacea

9. Lamprocystidia present; basidiospores ≥ 6 μm long……… 10

10. Basidiomata resupinate to effused-reflexed; from temperate China………………………………………………………… P. sinensis

10. Basidiomata strictly resupinate; from tropical-subtropical Asia or Australia……………………………………………………………………. 11

11. Basidiospores 6–7 × 2.5–3 μm; on bamboo; from Australia……………………………………………………………. P. bambusicola

11. Basidiospores 6.5–7.5 × 3–3.6 μm; on angiospermous wood; from Sri Lanka………………………………………………. P. brunnea

12. Lamprocystidia brown to dark brown; South American species…………………………………………………………………. P. amethystea

12. Lamprocystidia colorless to pale brown; North American or Asian species………………………………………………………. P. crassa s.l.

13. Lamprocystidia none; skeletocystidia or hymenial cystidia present………………………………………………………………………………….. 14

13. Lamprocystidia present; skeletocystidia absent……………. 15

14. Basidiospores 5.5–7 × 3–4 μm; on bamboo; from Colombia………………………………………………………. P. novae-granatae

14. Basidiospores 3.7–5.5 × 2.5–3.3 μm; on hardwood; from New Zealand……………………………………………………………. P. afibulata

15. Basidiospores > 8 μm long, >4 μm broad…………….. P. laxa

15. Basidiospores < 8 μm long, <4 μm broad…………………… 16

16. Lamprocystidia small, generally <40 μm long……………… 17

16. Lamprocystidia large, generally >40 μm long……………… 20

17. Hymenophore purple in KOH………………… P. cylindrospora

17. Hymenophore unchanged in KOH……………………………… 18

18. Basidiospores broadly ellipsoid, 3.5–4.5 × 2.5–3.5 μm, Q = 1.3……………………………………………………………….. P. yunnanensis

18. Basidiospores narrowly ellipsoid to cylindrical…………….. 19

19. Basidiospores 3.5–5 × 2–2.2 μm……………………. P. albescens

19. Basidiospores 5.3–8.5 × 2.5–4 μm……………. P. punjabensis

20. Lamprocystidia brown; on Pandanaceae; from Taiwan……………………………………………………….. P. brunneocystidiata

20. Lamprocystidia colorless; on other plants; from various locations………………………………………………………………………………… 21

21. Subiculum indistinct to absent…………………………………….. 22

21. Subiculum distinct to well-developed…………………………… 24

22. Basidia with two sterigmata…………………………….. P. bicornis

22. Basidia with four sterigmata………………………………………… 23

23. Basidiospores 5.5–7.5 × 3.5–4.5 μm; from North and South America……………………………………………………… P. flavidoalba

23. Basidiospores 4.5–6.5 × 3.8–4.8 μm; from Asia………………………………………………………………. P. magnicystidiata

24. Basidiospores narrowly ellipsoid to ellipsoid, ≤ 3 μm broad…………………………………………………………………………………….. 25

24. Basidiospores broadly ellipsoid, ≥4 μm broad…………….. 26

25. Hymenophore smooth, pale orange to rosy; lamprocystidia 40–50 × 6–7 μm; basidiospores < 2.5 μm wide; from Argentina……………………………………………………………… P. erubescens

25. Hymenophore smooth to tuberculate, pale white to gray; lamprocystidia 60–90 × 10–20 μm; basidiospores ≥ 2.5 μm wide; from Northern Hemisphere…………………………………….. P. gigantea

26. Lamprocystidia < 10 μm wide; from South America………………………………………………………………….. P. galochroa

26. Lamprocystidia > 10 μm wide; from Asia………………………………………………………………… P. darjeelingensis

Statements

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/supplementary material.

Author contributions

S-HH designed the research, collected most of the specimens, andwrote the text. Y-NZ performed the phylogenetic analyses and did most of the measurement, descriptions and illustrations. KN loaned and examined type specimens of some related species, and revised language of the text. C-CC provided with some specimens and sequences. S-LL helped in field trips and species illustrations. KLWK and H-XM helped in field trips and collected some specimens. M-RH collected some specimens and helped in specimen preservation. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

Financial support was provided by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 31870011 and 31750001).

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our deep appreciation to Profs. Sheng-Hua Wu (National Museum of Natural Science, Taiwan, China), Tie-Zhi Liu (Chifeng University, Inner Mongolia, China), and Bao-Kai Cui (Beijing Forestry University, Beijing, China) for allowing us to study their specimens.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

- ITS

internal transcribed spacer

- nrLSU

nuclear ribosomal large subunit

- BJFC

herbarium of Beijing Forestry University, Beijing, China

- CFMR

Centre for Forest Mycology Research, U.S. Forest Service, Madison, WI, United States

- TNM

National Museum of Natural Science, Taichung, Taiwan, China

- KOH

2% (w/v) potassium hydroxide

- IKI

Melzer’s reagent

- CB

cotton blue

- IKI–

neither amyloid nor dextrinoid

- CB–

acyanophilous

- L

mean spore length

- W

mean spore width

- Q, L/W ratio, n (a/b)

number of spores (a) measured from number of specimens (b)

- CTAB

cetyltrimethylammonium bromide

- DNA

deoxyribonucleic acid

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- MP

maximum parsimony

- ML

maximum likelihood

- BI

Bayesian inference

- TBR

tree-bisection reconnection

- BPP

Bayesian posterior probability

Footnotes

1.^ http://www.indexfungorum.org/

2.^ http://www.biology.duke.edu/fungi/mycolab/primers.htm

3.^ https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/

References

1

Bernicchia A. Gorjón S. P. (2010). Fungi Europaei 12. Corticiaceae s.l.Alassio: Edizioni Candusso.

2

Binder M. Larsson K. H. Matheny P. B. Hibbett D. S. (2010). Amylocorticiales ord. nov. and Jaapiales ord. nov.: early-diverging clades of Agaricomycetidae dominated by corticioid forms.Mycologia102865–880. 10.3852/09-288

3

Boidin J. Gilles G. (2003). À propos du genre Lopharia sensu lato (Basidiomycètes, Aphyllophorales).Bull. Soc. Mycol. France11891–115.

4

Buchanan P. K. Ryvarden L. (2000). An annotated checklist of polypore and polypore-like fungi recorded from New Zealand.N. Zeal. J. Bot.38265–323. 10.1080/0028825X.2000.9512683

5

Burdsall H. H. Jr. (1985). A Contribution to the Taxonomy of the Genus Phanerochaete. Mycologia Memoirs.Lehre: J. Cramer. 10.1080/0028825x.2000.9512683

6

Chen C. C. Wu S. H. Chen C. Y. (2018a). Four species of polyporoid fungi newly recorded from Taiwan.Mycotaxon13345–54. 10.5248/133.45

7

Chen C. C. Wu S. H. Chen C. Y. (2018b). Hydnophanerochaete and Odontoefibula, two new genera of phanerochaetoid fungi (Polyporales, Basidiomycota) from East Asia.Mycokeys3975–96. 10.3897/mycokeys.39.28010

8

Chikowski R. S. Larsson K. H. Gibertoni T. B. (2015). Three new combinations in Rhizochaete (Agaricomycetes, Fungi) and a new record to the Brazilian Amazonia.Nova Hedwig.102185–196. 10.1127/nova_hedwigia/2015/0298

9

Cunningham G. H. (1965). Polyporaceae of New Zealand.N. Zeal. Depart. Sci. Industr. Res. Bull.164:304.

10

Darriba D. Taboada G. L. Doallo R. Posada D. (2012). jModelTest 2: more models, new heuristics and parallel computing.Nat. Methods9:772. 10.1038/nmeth.2109

11

De A. B. (1998). Taxonomy of Oxyporus vellereus comb. nov.J. Mycopathol. Res.3641–44.

12

de Koker T. Nakasone K. K. Haarhof J. Burdsall H. H. Jr. Janse B. J. H. (2003). Phylogenetic relationships of the genus Phanerochaete inferred from the internal transcribed spacer region.Mycol. Res.1071032–1040. 10.1017/S095375620300827X

13

Dhingra G. S. (1987). The genus Phlebiopsis in the Eastern Himalayas.Nova Hedwig.44221–227.

14

Douanla-Meli C. Langer E. (2009). Fungi of Cameroon I. New corticioid species (Basidiomycetes).Mycotaxon10795–103. 10.5248/107.95

15

Duhem B. Michel H. (2009). Une espèce nouvelle de Corticium s. st. Études dans les genre Dendrocorticium et Dentocorticium (Basidiomycotina).Cryptogam. Mycol.30161–179.

16

Eriksson J. Hjortstam K. Ryvarden L. (1978). The Corticiaceae of North Europe. Mycoaciella - Phanerochaete, Vol. 5. Oslo, NO: Fungiflora.

17

Eriksson J. Hjortstam K. Ryvarden L. (1981). The Corticiaceae of North Europe. Phlebia - Sarcodontia, Vol. 6. Oslo, NO: Fungiflora.

18

Eriksson J. Hjortstam K. Ryvarden L. (1984). The Corticiaceae of North Europe. Schizopora - Suillosporium, Vol. 7. Oslo, NO: Fungiflora.

19

Floudas D. Hibbett D. S. (2015). Revisiting the taxonomy of Phanerochaete (Polyporales, Basidiomycota) using a four gene dataset and extensive ITS sampling.Fungal Biol.119679–719. 10.1016/j.funbio.2015.04.003

20

Gilbertson R. L. Adaskaveg J. E. (1993). Studies on wood-rotting basidiomycetes of Hawaii.Mycotaxon49369–397.

21

Gilbertson R. L. Blackwell M. (1985). Notes on the wood-rotting fungi on Junipers in the Gulf Coast region.Mycotaxon24325–348.

22

Greslebin A. G. Nakasone K. K. Rajchenberg M. (2004). Rhizochaete, a new genus of phanerochaetoid fungi.Mycologia96260–271. 10.1080/15572536.2005.11832976

23

Hall T. A. (1999). Bioedit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT.Nucleic Acids Symp. Ser.4195–98.

24

Hjortstam K. (1987). A check-list to genera and species of corticioid fungi (Hymenomycetes).Windahlia1755–85.

25

Hjortstam K. (1989). Corticioid fungi described by M. J. Berkeley.Kew Bull.44301–315. 10.2307/4110803

26

Hjortstam K. Ryvarden L. (1980). Studies in tropical Corticiaceae (Basidiomycetes) I.Mycotaxon10269–287.

27

Hjortstam K. Ryvarden L. (1990). Lopharia and Porostereum (Corticiacae).Synopsis Fungorum41–68. 10.1007/978-3-319-23534-9_1

28

Hjortstam K. Ryvarden L. (2005). New taxa and new combinations in tropical corticioid fungi, (Basidiomycotina, Aphyllophorales).Synopsis Fungorum2033–41.

29

Jia B. S. Zhou L. W. Cui B. K. Rivoire B. Dai Y. C. (2014). Taxonomy and phylogeny of Ceriporia (Polyporales, Basidiomycota) with an emphasis of Chinese collections.Mycol. Prog.1381–93. 10.1007/s11557-013-0895-5

30

Jülich W. (1978). Studies in resupinate Basidiomycetes - V. Some new genera and species.Persoonia10137–140.

31

Jülich W. Stalpers J. A. (1980). The Resupinate Non-Poroid Aphyllophorales of the Temperate Northern Hemisphere. Verhandelingen der Koninklijke Nederlandse Akademie van Wetenschappen, Afd.Amsterdam: Elsevier Science Ltd.

32

Justo A. Miettinen O. Floudas D. Ortiz-Santana B. Sjokvist E. Lindner D. et al (2017). A revised family-level classification of the Polyporales (Basidiomycota).Fungal Biol.121798–824. 10.1016/j.funbio.2017.05.010

33

Katoh K. Rozewicki J. Yamada K. D. (2017). MAFFT online service: multiple sequence alignment, interactive sequence choice and visualization.Brief. Bioinform.201160–1166. 10.1093/bib/bbx108

34

Kaur G. Singh A. P. Dhingra G. S. (2015). Phlebiopsis punjabensis, a new species from India.Mycotaxon130907–909. 10.5248/130.907

35

Kearse M. Moir R. Wilson A. Stones-Havas S. Cheung M. Sturrock S. et al (2012). Geneious Basic: an integrated and extendable desktop software platform for the organization and analysis of sequence data.Bioinformatics281647–1649. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts199

36

Kornerup A. Wanscher J. H. (1978). Methuen Handbook of Colour, 3rd Edn, London: E. Methuen and Co. Ltd.

37

Larsen M. J. Gilberston R. L. (1977). Studies in Laeticorticium (Aphyllophorales, Corticiaceae) and related genera.Norweg. J. Bot.2499–121.

38

Larsson K. H. (2007). Re-thinking the classification of corticioid fungi.Mycol. Res.1111040–1063. 10.1016/j.mycres.2007.08.001

39

Lentz P. L. (1955). Stereum and Allied Genera of Fungi in the Upper Mississippi Valley.Agriculture Monograph No. 24. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture.

40

Lim Y. W. (2001). Systematic Study of Corticioid Fungi Based on Molecular Sequence Analyses.Thesis, Seoul National University, Seoul.

41

Lim Y. W. Jung H. S. (2003). Irpex hydnoides, sp. nov. is new to science, based on morphological, cultural and molecular characters.Mycologia95694–699. 10.1080/15572536.2004.11833073

42

Liu S. L. He S. H. (2016). Phanerochaete porostereoides, a new species in the core clade with brown generative hyphae from China.Mycosphere7648–655. 10.5943/mycosphere/7/5/10

43

Ma X. Zhao C. L. (2019). Crepatura ellipsospora gen. et sp. nov. in Phanerochaetaceae (Polyporales, Basidiomycota) bearing a tuberculate hymenial surface.Mycol. Prog.18785–793. 10.1007/s11557-019-01488-0

44

Maddison W. P. Maddison D. R. (2018). Mesquite: A Modular System for Evolutionary Analysis. Version 3.5.1. Available online at: http://www.mesquiteproject.org(accessed April 15, 2020).

45

Massee G. (1891). A monograph of the Thelephoraceae Part II.J. Linnean Soc. Bot.2795–205. 10.1111/j.1095-8339.1890.tb00801.x

46

Melo I. Hjortstam K. (2002). Australohydnum dregeanum (Basidiomycetes, Stereaceae) in Europe.Nova Hedwig.74527–532. 10.1127/0029-5035/2002/0074-0527

47