Abstract

Dead wood-associated fungi play an important role in wood degradation and the recycling of organic matter in the forest ecological system. Xenasmataceae is a cosmopolitan group of wood-rotting fungi that grows on tropical, subtropical, temperate, and boreal vegetation. In this study, a new fungal order, Xenasmatales, is introduced based on both morphology and multigene phylogeny to accommodate Xenasmataceae. According to the internal transcribed spacer and nuclear large subunit (ITS+nLSU) and nLSU-only analyses of 13 orders, Xenasmatales formed a single lineage and then grouped with orders Atheliales, Boletales, and Hymenochaetales. The ITS dataset revealed that the new taxon Xenasmatella nigroidea clustered into Xenasmatella and was closely grouped with Xenasmatella vaga. In the present study, Xenasmatella nigroidea collected from Southern China is proposed as a new taxon, based on a combination of morphology and phylogeny. Additionally, a key to the Xenasmatella worldwide is provided.

Introduction

Among eukaryotic microorganisms, wood-decaying fungi interact positively with dead wood, playing a fundamental ecological role as decomposers of plants in the fungal tree of life (James et al., 2020). Wood-associated fungi are cosmopolitan and rich in diversity since they grow on tropical, subtropical, temperate, and boreal vegetation (Gilbertson and Ryvarden, 1987; Núñez and Ryvarden, 2001; Bernicchia and Gorjón, 2010; Dai, 2012; Ryvarden and Melo, 2014; Dai et al., 2015, 2021; Wu et al., 2020).

Xenasmataceae Oberw., a typical wood-associated fungal group mainly distributed in the tropics was discovered by Oberwinkler (1966), and typified by Xenasma Donk. Three genera, namely, Xenasma, Xenasmatella Oberw., and Xenosperma Oberw., have been accommodated in this family, however, higher-level classification of the order has not been designated. The tenth edition of the Dictionary of the Fungi showed that Xenasmataceae belongs to Polyporales Gäum., and consists of three genera (Kirk et al., 2008). MycoBank indicates that Xenasmataceae has a higher classification within Polyporales, although the Index Fungorum shows that Xenasmataceae belongs to the order Russulales.

High phylogenetic diversity among corticioid homobasidiomycetes suggests a close relationship among Radulomyces M.P. Christ., Xenasmatella, and Coronicium J. Erikss. and Ryvarden. Xenasma pseudotsugae (Burt) J. Erikss. nested into the euagarics clade, in which it grouped with Coronicium and Radulomyces. The three taxa of Radulomyces grouped together with Phlebiella pseudotsugae (Burt) K.H. Larss. and Hjortstam and Coronicium alboglaucum (Bourdot and Galzin) Jülich, and were composed of a rather confusing group with no obvious morphological features or ecological specialization to tie these three genera together (Larsson et al., 2004). The classification of corticioid fungi with 50 putative families from published preliminary analyses and phylogenies of sequence data showed that three species of Xenasmatella formed a single lineage with strong support within the unplaced Phlebiella family, in which this clade was unclaimed to any orders (Larsson, 2007). A higher-level phylogenetic classification of the Kingdom Fungi revealed that the Phlebiella clade and Jaapia clade do not show affinities within any orders (Hibbett et al., 2007). An outline of all genera of Basidiomycota with combined SSU, ITS, LSU, tef1, rpb1, and rpb2 datasets showed that Xenasmatella was assigned to Xenasmataceae within the order Russulales (He et al., 2019). Therefore, there is debate on the classification at the order level for the Xenasmataceae.

Recently, Xenasmatella has been studied deeply on the basis of morphology and phylogeny. Phlebiella P. Karst. was deemed to have not been legitimately published previously, and the name Xenasmatella was accepted (Duhem, 2010; Larsson et al., 2020; Maekawa, 2021). Molecular systematics involving Xenasmatella was carried out recently. On the basis of morphological and molecular identification, Zong et al. (2021) studied the sequences of 27 fungal specimens representing 24 species between the Xenasmatella clade and related orders; and the Xenasmatella clade formed a single lineage and three new species, namely, X. rhizomorpha C.L. Zhao, X. tenuis C.L. Zhao, and X. xinpingensis C.L. Zhao. Both the MycoBank database (http://www.MycoBank.org) and Index Fungorum (http://www.indexfungorum.org, accessed on June 20, 2022) have recorded 41 specific and infraspecific names in Xenasmatella. To date, the number of Xenasmatella species accepted worldwide has reached 25 (Oberwinkler, 1966; Stalpers, 1996; Hjortstam and Ryvarden, 2005; Bernicchia and Gorjón, 2010; Duhem, 2010; Larsson et al., 2020; Maekawa, 2021), of which, nine species have been found in China (Dai et al., 2004; Dai, 2011; Huang et al., 2019; Zong and Zhao, 2021; Zong et al., 2021).

In the present study, we verified the taxonomy and phylogeny of Xenasmataceae. In addition, we analyzed the species diversity of Xenasmataceae and constructed a phylogeny to the order level of this family on the basis of large subunit nuclear ribosomal RNA gene (nLSU) sequences, the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) regions, and ITS+nLSU analyses. Based on both morphology and phylogeny, we propose a new fungal order, Xenasmatales and a new species, Xenasmatella nigroidea. A key to the 25 accepted species of Xenasmatella worldwide is also provided.

The accepted species list

Xenasma Donk (1957).

Xenasma Aculeatum C.E. Gómez (1972).

Xenasma Amylosporum Parmasto (1968).

Xenasma Longicystidiatum Boidin and Gilles (2000).

Xenasma Parvisporum Pouzar (1982).

Xenasma Praeteritum (H.S. Jacks.) Donk (1957).

Xenasma Pruinosum (Pat.) Donk (1957).

Xenasma Pulverulentum (H.S. Jacks.) Donk (1957).

Xenasma Rimicola (P. Karst.) Donk (1957).

Xenasma Subclematidis S.S. Rattan (1977).

Xenasma Tulasnelloideum (Höhn. and Litsch.) Donk (1957).

Xenasma Vassilievae Parmasto (1965).

Xenasmatella Oberwinkler (1966).

Xenasmatella Ailaoshanensis C.L. Zhao ex C.L. Zhao and T.K. Zong (2021).

Xenasmatella Alnicola (Bourdot and Galzin) K.H. Larss. and Ryvarden (2020).

Xenasmatella Ardosiaca (Bourdot and Galzin) Stalpers (1996).

Xenasmatella Athelioidea (N. Maek.) N. Maek. (2021).

Xenasmatella Bicornis (Boidin and Gilles) Piatek (2005).

Xenasmatella Borealis (K.H. Larss. and Hjortstam) Duhem (2010).

Xenasmatella Caricis-Pendulae (P. Roberts) Duhem (2010).

Xenasmatella Christiansenii (Parmasto) Stalpers (1996).

Xenasmatella Cinnamomea (Burds. and Nakasone) Stalpers (1996).

Xenasmatella Fibrillosa (Hallenb.) Stalpers (1996).

Xenasmatella Globigera (Hjortstam and Ryvarden) Duhem (2010).

Xenasmatella Gossypina (C.L. Zhao) G. Gruhn and Trichies (2021).

Xenasmatella Inopinata (H.S. Jacks.) Hjortstam and Ryvarden (1979).

Xenasmatella Insperata (H.S. Jacks.) Jülich (1979).

Xenasmatella Nasti Boidin and Gilles ex Stalpers (1996).

Xenasmatella Odontioidea Ryvarden and Liberta (1978).

Xenasmatella Palmicola (Hjortstam and Ryvarden) Duhem (2010).

Xenasmatella Rhizomorpha C.L. Zhao (2021).

Xenasmatella Romellii Hjortstam (1983).

Xenasmatella Sanguinescens Svrček (1973).

Xenasmatella Subflavidogrisea (Litsch.) Oberw. ex Jülich (1979).

Xenasmatella Tenuis C.L. Zhao (2021).

Xenasmatella Vaga (Fr.) Stalpers (1996).

Xenasmatella Wuliangshanensis (C.L. Zhao) G. Gruhn and Trichies (2021).

Xenasmatella Xinpingensis C.L. Zhao (2021).

Xenosperma Oberw. (1966).

Materials and methods

Sample collection and herbarium specimen preparation

Fresh fruit bodies of fungi growing on the stumps of angiosperms were collected from Honghe, Yunnan Province, P.R. China. The samples were photographed in situ, and macroscopic details were recorded. Field photographs were taken by a Jianeng 80D camera. All photographs were focus stacked and merged using Helicon Focus software. Once the macroscopic details were recorded, the specimens were transported to a field station where they were dried on an electronic food dryer at 45°C. Once dried, the specimens were labeled and sealed in envelopes and plastic bags. The dried specimens were deposited in the herbarium of the Southwest Forestry University (SWFC), Kunming, Yunnan Province, P.R. China.

Morphology

The macromorphological descriptions were based on field notes and photos captured in the field and laboratory. The color, texture, taste, and odor of fruit bodies were mostly based on the authors' field trip investigations. Rayner (1970) and Petersen (1996) were used for the color terms. All materials were examined under a Nikon 80i microscope. Drawings were made with the aid of a drawing tube. The measurements and drawings were made from slide preparations stained with cotton blue (0.1 mg aniline blue dissolved in 60 g pure lactic acid), melzer's reagent (1.5 g potassium iodide, 0.5 g crystalline iodine, 22 g chloral hydrate, and aq. dest. 20 ml), and 5% potassium hydroxide. Spores were measured from the sections of the tubes; and when presenting spore size data, 5% of the measurements excluded from each end of the range are shown in parentheses (Wu et al., 2022). The following abbreviations were used: KOH = 5% potassium hydroxide water solution, CB = cotton clue, CB– = acyanophilous, IKI = Melzer's reagent, IKI– = both inamyloid and indextrinoid, L = means spore length (arithmetic average for all spores), W = means spore width (arithmetic average for all spores), Q = variation in the L/W ratios between the specimens studied, and n = a/b (number of spores (a) measured from given number (b) of specimens).

Molecular phylogeny

The CTAB rapid plant genome extraction kit-DN14 (Aidlab Biotechnologies Co., Ltd., Beijing, P.R. China) was used to obtain genomic DNA from the dried specimens following the manufacturer's instructions (Zhao and Wu, 2017). The nuclear ribosomal ITS region was amplified with the primers ITS5 and ITS4 (White et al., 1990). The nuclear nLSU region was amplified with the primer pairs LR0R and LR7 (http://lutzonilab.org/nuclear-ribosomal-dna/, accessed on September 12, 2021). The PCR procedure used for ITS was as follows: initial denaturation at 95°C for 3 min, followed by 35 cycles at 94°C for 40 s, 58°C for 45 s, and 72°C for 1 min, and a final extension of 72°C for 10 min. The PCR procedure used for nLSU was as follows: initial denaturation at 94°C for 1 min, followed by 35 cycles at 94°C for 30 s, 48°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1.5 min, and a final extension of 72°C for 10 min. The PCR products were purified and sequenced at Kunming Tsingke Biological Technology Limited Company (Yunnan Province, P.R. China). All the newly generated sequences were deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) GenBank (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/, accessed on September 12, 2021) (Table 1).

Table 1

| Species Name | Specimen No. | GenBank Accession No. | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ITS | nLSU | |||

| Albatrellus confluens | PV 10193 | – | AF506393 | Larsson et al., 2004 |

| Aleurobotrys botryosus | CBS 336.66 | MH858812 | MH870451 | Vu et al., 2019 |

| Amaurodon viridis | TAA 149664 | AY463374 | AY586625 | Larsson et al., 2004 |

| Amphinema byssoides | EL 1198 | – | AY586626 | Larsson et al., 2004 |

| Amylostereum areolatum | NH 8041 | – | AF506405 | Larsson and Larsson, 2003 |

| Aphanobasidium pseudotsugae | NH 10396 | – | AY586696 | Larsson et al., 2004 |

| Auriscalpium vulgare | EL 3395 | – | AF506375 | Larsson and Larsson, 2003 |

| Athelia epiphylla | EL 1298 | AY463382 | AY586633 | Larsson et al., 2004 |

| Athelopsis subinconspicua | KHL 8490 | AY463383 | AY586634 | Larsson et al., 2004 |

| Bondarzewia dickinsii | Li 150909/19 | KX263721 | KX263723 | Unpublished |

| Candelabrochaete septocystidia | AS 95 | – | EU118609 | Larsson, 2007 |

| Chaetodermella luna | NH 8482 | EU118615 | – | Larsson, 2007 |

| C. luna | CBS 305.65 | – | MH870216 | Vu et al., 2019 |

| Chondrostereum purpureum | EL 5997 | – | AY586644 | Larsson et al., 2004 |

| Clavulicium delectabile | KHL 11147 | – | AY586688 | Larsson et al., 2004 |

| Clavulina cristata | EL 9597 | AY463398 | AY586648 | Larsson et al., 2004 |

| Columnocystis abietina | KHL 12474 | EU118619 | – | Larsson, 2007 |

| Coronicium alboglaucum | NH 4208 | – | AY586650 | Larsson et al., 2004 |

| Cystostereum murrayi | KHL 12496 | EU118623 | – | Larsson, 2007 |

| Dacrymyces stillatus | CBS 195.48 | MH856306 | MH867857 | Vu et al., 2019 |

| Dacryopinax spathularia | Miettinen 20559 | MW191976 | MW159092 | Unpublished |

| Erythricium laetum | NH 14530 | AY463407 | AY586655 | Larsson et al., 2004 |

| Exidia recisa | SL Lindberg 180317 | – | MT664783 | Unpublished |

| Exidiopsis calcea | KHL 11075 | – | AY586654 | Larsson et al., 2004 |

| Gloeocystidiellum porosum | FCUG 1933 | – | AF310094 | Larsson and Hallenberg, 2001 |

| Haplotrichum conspersum | KHL 11063 | AY463409 | AY586657 | Larsson et al., 2004 |

| Hydnocristella himantia | KUC 20131001-35 | – | KJ668382 | Unpublished |

| Hydnomerulius pinastri | 412 | – | AF352044 | Jarosch and Besl, 2001 |

| Hydnum repandum | 420526MF0827 | – | MG712372 | Unpublished |

| Hygrophoropsis aurantiaca | EL 4299 | – | AY586659 | Larsson et al., 2004 |

| Hymenochaete cinnamomea | EL 699 | AY463416 | AY586664 | Larsson et al., 2004 |

| Hyphodermella corrugate | KHL 3663 | – | EU118630 | Larsson, 2007 |

| Hyphodontia aspera | KHL 8530 | AY463427 | AY586675 | Larsson et al., 2004 |

| Inonotus radiatus | TW 704 | – | AF311018 | Wagner and Fischer, 2001 |

| Junghuhnia nitida | CBS 45950 | – | MH868226 | Vu et al., 2019 |

| Kavinia alboviridis | EL 1698 | – | AY463434 | Larsson et al., 2004 |

| Kavinia himantia | LL 98 | AY463435 | AY586682 | Larsson et al., 2004 |

| Lactarius volemus | KHL 8267 | – | AF506414 | Larsson and Larsson, 2003 |

| Laetisaria fuciformis | CBS 18249 | – | MH868023 | Vu et al., 2019 |

| Lentaria dendroidea | SJ 98012 | EU118640 | EU118641 | Larsson, 2007 |

| Lignosus hainanensis | Dai 10670 | NR154112 | GU580886 | Cui et al., 2011 |

| Merulicium fusisporum | Hjm s.n. | EU118647 | – | Larsson, 2007 |

| Mycoaciella bispora | EL 1399 | – | AY586692 | Larsson et al., 2004 |

| Peniophora pini | Hjm 18143 | – | EU118651 | Larsson, 2007 |

| Phanerochaete sordida | KHL 12054 | – | EU118653 | Larsson, 2007 |

| Phellinus chrysoloma | TN 4008 | – | AF311026 | Wagner and Fischer, 2001 |

| Phlebia nitidula | Nystroem 020830 | – | EU118655 | Larsson, 2007 |

| Podoscypha multizonata | CBS 66384 | – | MH873501 | Vu et al., 2019 |

| Polyporus tubiformis | WD 1839 | AB587634 | AB368101 | Sotome et al., 2011 |

| Porpomyces mucidus | KHL 11062 | AF347091 | – | Unpublished |

| P. mucidus | Dai 10726 | – | KT157839 | Wu et al., 2015 |

| Pseudomerulius aureus | BN 99 | – | AY586701 | Larsson et al., 2004 |

| Punctularia strigosozonata | LR 40885 | AY463456 | AY586702 | Larsson et al., 2004 |

| Rickenella fibula | AD 86033 | – | AY586710 | Larsson et al., 2004 |

| Russula violacea | SJ 93009 | AF506465 | AF506465 | Larsson and Larsson, 2003 |

| Scopuloides hydnoides | WEI 17569 | – | MZ637283 | Chen et al., 2021 |

| Sistotrema alboluteum | TAA 167982 | AY463467 | AY586713 | Larsson et al., 2004 |

| Sistotremastrum niveocremeum | MAFungi 12915 | – | JX310442 | Telleria et al., 2013 |

| Sistotremastrum suecicum | KHL 11849 | – | EU118667 | Larsson, 2007 |

| Sphaerobasidium minutum | KHL 11714 | – | DQ873653 | Larsson et al., 2006 |

| Stereum hirsutum | NH 7960 | AF506479 | – | Larsson and Larsson, 2003 |

| Tomentellopsis echinospora | KHL 8459 | AY463472 | AY586718 | Larsson et al., 2004 |

| Trametes suaveolens | CBS 279.28 | MH855012 | MH866480 | Vu et al., 2019 |

| Trechispora farinacea | KHL 8793 | AF347089 | – | Larsson et al., 2004 |

| T. farinacea | MAFungi 79474 | – | JX392856 | Telleria et al., 2013 |

| Tubulicrinis subulatus | KHL 11079 | AY463478 | AY586722 | Larsson et al., 2004 |

| Veluticeps abietina | HHB 13663 | – | KJ141191 | Unpublished |

| Veluticeps berkeleyi | HHB 8594 | – | HM536081 | Garcia-Sandoval et al., 2010 |

| Vuilleminia comedens | EL 199 | AY463482 | AY586725 | Larsson et al., 2004 |

| Wrightoporia lenta | KN 150311 | – | AF506489 | Larsson and Larsson, 2003 |

| Xerocomus chrysenteron | EL 3999 | AF347103 | – | Larsson et al., 2004 |

| Xenasma praeteritum | ACD 0185 | OM009268 | Unpublished | |

| Xenasma pruinosum | OTU 1299 | MT594801 | Unpublished | |

| Xenasma rimicola | NLB 1571 | MT571671 | Unpublished | |

| X. rimicola | NLB 1449 | MT537020 | Unpublished | |

| Xenasmatella ailaoshanensis | CLZhao 3895 | MN487105 | – | Huang et al., 2019 |

| X. ailaoshanensis | CLZhao 4839 | MN487106 | – | Huang et al., 2019 |

| Xenasmatella ardosiaca | CBS 126045 | MH864060 | MH875515 | Vu et al., 2019 |

| Xenasmatella borealis | UC 2022974 | KP814210 | – | Rosenthal et al., 2017 |

| X. borealis | UC 2023132 | KP814274 | – | Rosenthal et al., 2017 |

| Xenasmatella christiansenii | TASM YGG 26 | MT526341 | – | Gafforov et al., 2020 |

| X. christiansenii | TASM YGG 36 | MT526342 | – | Gafforov et al., 2020 |

| Xenasmatella gossypina | CLZhao 4149 | MW545958 | – | Zong and Zhao, 2021 |

| X. gossypina | CLZhao 8233 | MW545957 | – | Zong and Zhao, 2021 |

| Xenasmatella nigroidea | CLZhao 18300 | OK045679 | OK045677 | Present study |

| X. nigroidea | CLZhao 18333 * | OK045680 | OK045678 | Present study |

| Xenasmatella rhizomorpha | CLZhao 9156 | MT832954 | – | Zong et al., 2021 |

| X. rhizomorpha | CLZhao 9847 | MT832953 | – | Zong et al., 2021 |

| Xenasmatella tenuis | CLZhao 4528 | MT832960 | – | Zong et al., 2021 |

| X. tenuis | CLZhao 11258 | MT832959 | – | Zong et al., 2021 |

| Xenasmatella vaga | KHL 11065 | EU118660 | EU118661 | Larsson, 2007 |

| X. vaga | BHI-F 160a | MF161185 | – | Haelewaters et al., 2018 |

| Xenasmatella wuliangshanensis | CLZhao 4080 | MW545962 | – | Zong and Zhao, 2021 |

| X. wuliangshanensis | CLZhao 4308 | MW545963 | – | Zong and Zhao, 2021 |

| Xenasmatella xinpingensis | CLZhao 2216 | MT832961 | – | Zong et al., 2021 |

| X. xinpingensis | CLZhao 2467 | MT832962 | – | Zong et al., 2021 |

The list of species, specimens, and GenBank accession numbers of sequences used in this study.

Indicates type materials.

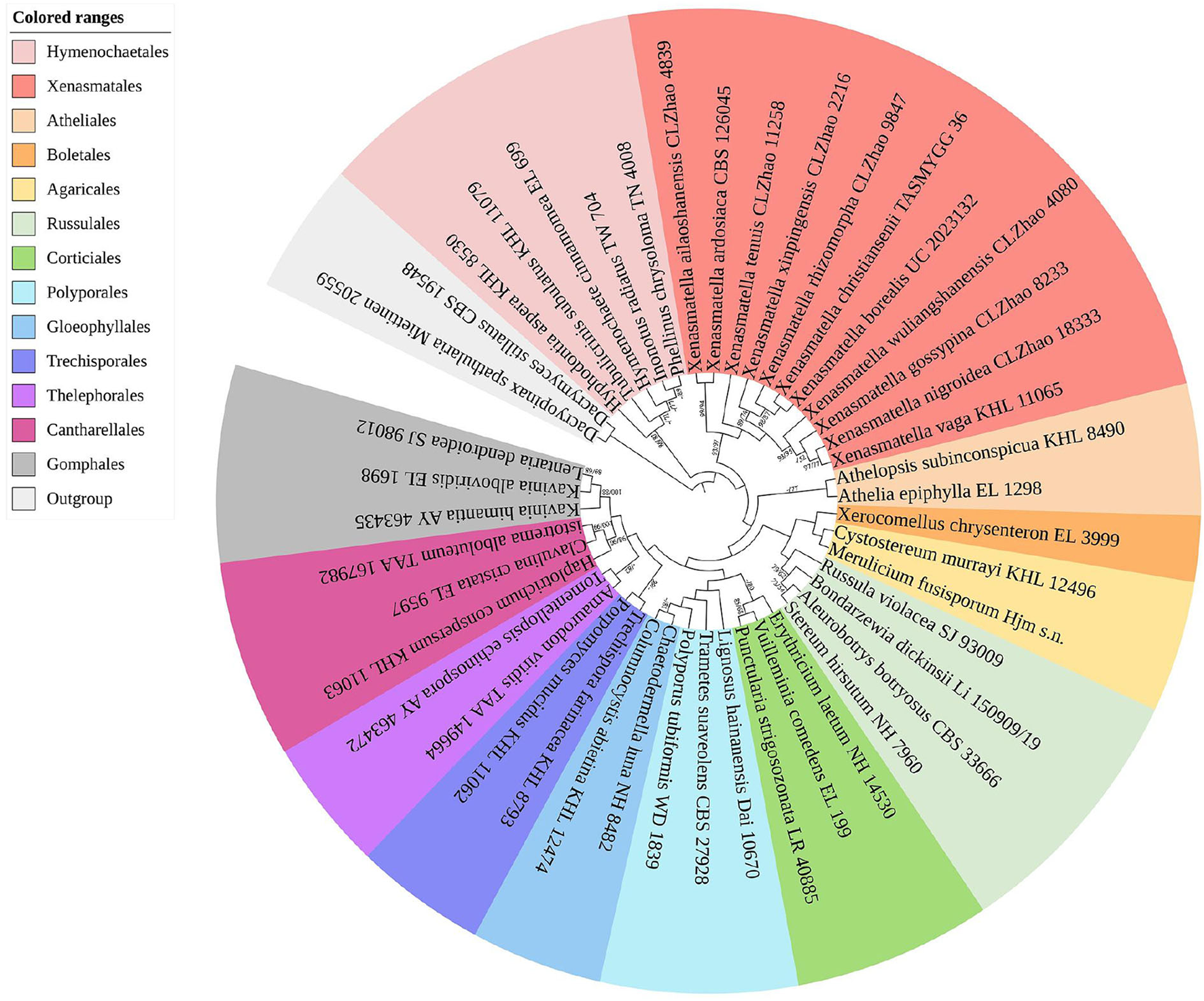

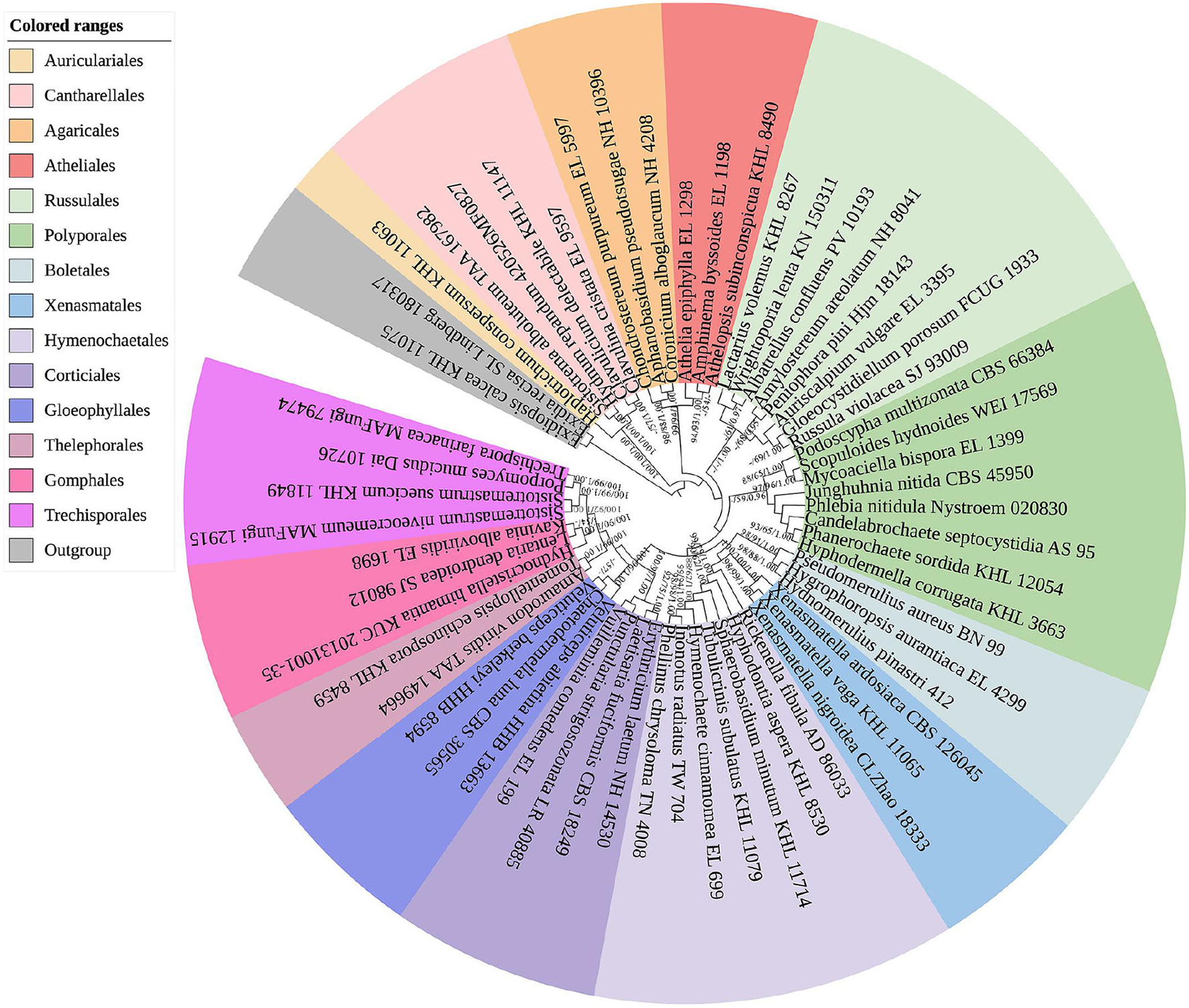

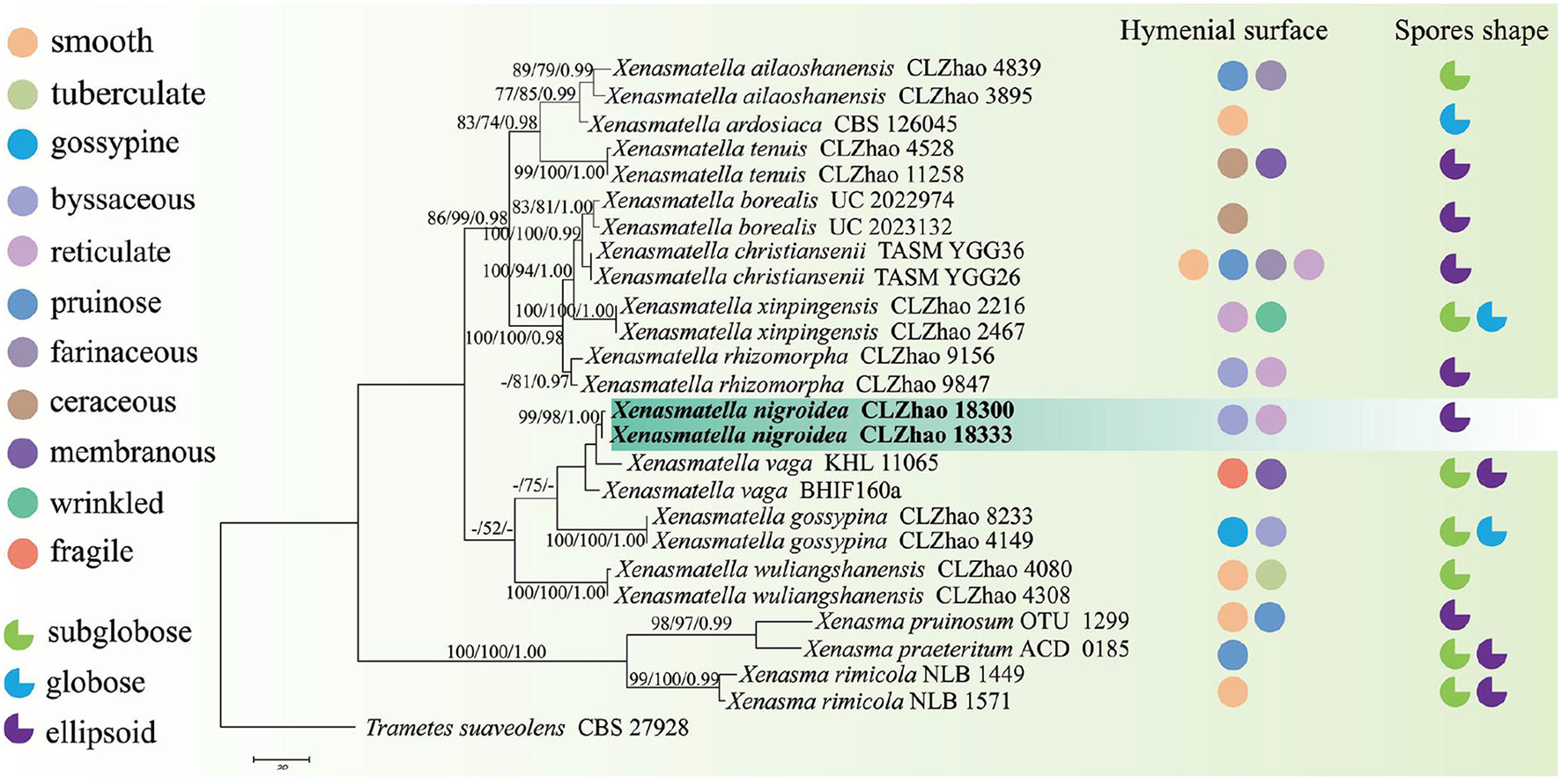

The sequences and alignment were adjusted manually using AliView version 1.27 (Larsson, 2014). The datasets were aligned with Mesquite version 3.51. The ITS+nLSU dataset and the nLSU-only sequence dataset were used to position a new order, Xenasmatales, and the ITS-only dataset was used to position a new species among the Xenasmatella-related taxa. Sequences of Dacrymyces stillatus and Dacryopinax spathularia retrieved from GenBank were used as the outgroup for the ITS+nLSU sequences (Figure 1) (He et al., 2019); sequences of Exidia recisa and Exidiopsis calcea retrieved from GenBank were used as the outgroup for the nLSU sequences (Figure 2) (Larsson, 2007); and the sequence of Trametes suaveolens was used as the outgroup for the ITS-only sequences (Figure 3) (Zong and Zhao, 2021).

Figure 1

A maximum parsimony strict consensus tree illustrating the phylogeny of the new order Xenasmatales and related order in the class Agaricomycetes based on ITS+nLSU sequences. The orders represented by each color are indicated in the upper left of the phylogenetic tree. Branches are labeled with a maximum likelihood bootstrap value ≥ 70%, and a parsimony bootstrap value ≥ 50, respectively.

Figure 2

A maximum parsimony strict consensus tree illustrating the phylogeny of the new order Xenasmatales and related order in the class Agaricomycetes based on nLSU sequences. The orders represented by each color are indicated in the upper left of the phylogenetic tree. Branches are labeled with a maximum likelihood bootstrap value ≥ 70%, a parsimony bootstrap value ≥ 50%, and Bayesian posterior probabilities ≥ 0.95, respectively.

Figure 3

A maximum parsimony strict consensus tree illustrating the phylogeny of a new species and related species in Xenasmatella and Xenasma based on ITS sequences. Branches are labeled with a maximum likelihood bootstrap value ≥ 70%, a parsimony bootstrap value ≥ 50%, and Bayesian posterior probabilities ≥ 0.95, respectively. The new species are in bold.

The three combined datasets were analyzed using maximum parsimony (MP), maximum likelihood (ML), and Bayesian inference (BI), according to Zhao and Wu (2017), and the tree was constructed using PAUP* version 4.0b10 (Swofford, 2002). All characters were equally weighted and gaps were treated as missing data. Trees were inferred using the heuristic search option with TBR branch swapping and 1,000 random sequence additions. Max-trees were set to 5,000, branches of zero length were collapsed, and all parsimonious trees were saved. Clade robustness was assessed using the bootstrap (BT) analysis with 1,000 replicates (Felsenstein, 1985). Descriptive tree statistics—tree length (TL), consistency index (CI), retention index (RI), rescaled consistency index (RC), and homoplasy index (HI)—were calculated for each maximum parsimonious tree generated. In addition, multiple sequence alignment was analyzed using ML in RAxML-HPC2 through the Cipres Science Gateway (Miller et al., 2012). Branch support (BS) for ML analysis was determined by 1,000 bootstrap replicates.

MrModeltest 2.3 (Nylander, 2004) was used to determine the best-fit evolution model for each dataset of BI, which was performed using MrBayes 3.2.7a with a GTR+I+G model of DNA substitution and a gamma distribution rate variation across sites (Ronquist et al., 2012). A total of 4 Markov chains were run for 2 runs from random starting trees for 1 million generations for the ITS+nLSU dataset (Figure 1), 1.4 million generations for the nLSU-only sequences (Figure 2), and 0.5 million generations for the ITS-only sequences (Figure 3), with trees and parameters sampled every 1,000 generations. The first one-fourth of all generations was discarded as a burn-in. The majority rule consensus tree of all remaining trees was calculated. Branches were considered significantly supported if they received a maximum likelihood bootstrap value (BS) ≥70%, a maximum parsimony bootstrap value (BT) ≥70%, or Bayesian posterior probabilities (BPP) ≥0.95.

Results

Phylogenetic analyses

The ITS+nLSU dataset (Figure 1) included sequences from 45 fungal specimens representing 45 species. The dataset had an aligned length of 3,095 characters, of which 1,910 characters are constant, 353 are variable and parsimony uninformative, and 832 are parsimony informative. Maximum parsimony analysis yielded 45 equally parsimonious trees (TL = 3,984, CI = 0.4666, HI = 0.5334, RI = 0.3909, and RC = 0.1824). The best model was GTR+I+G [lset nst = 6, rates = invgamma; prset statefreqpr = dirichlet (1,1,1,1)]. Bayesian and ML analyses showed a topology similar to that of MP analysis with split frequencies equal to 0.009126 (BI), and the effective sample size (ESS) across the two runs is double that of the average ESS (avg ESS) = 250.5.

The ITS+nLSU rDNA gene regions (Figure 1) were based on 13 orders, namely, Agaricales Underw., Atheliales Jülich, Boletales E.J. Gilbert, Cantharellales Gäum., Corticiales K.H. Larss., Gloeophyllales Thorn, Gomphales Jülich, Hymenochaetales Oberw., Polyporales, Russulales, Thelephorales Corner ex Oberw., Trechisporales, and Xenasmatales, while Xenasmatella was separated from the other orders.

The nLSU-alone dataset (Figure 2) included sequences from 58 fungal specimens representing 58 species. The dataset had an aligned length of 1,343 characters, of which 726 characters are constant, 176 are variable and parsimony-uninformative, and 441 are parsimony-informative. Maximum parsimony analysis yielded 3 equally parsimonious trees (TL = 2,864, CI = 0.3209, HI = 0.6791, RI = 0.4476, and RC = 0.1436). The best model for the ITS dataset estimated and applied in the Bayesian analysis was GTR+I+G [lset nst = 6, rates = invgamma; prset statefreqpr = dirichlet (1,1,1,1)]. The Bayesian and ML analyses resulted in a topology similar to that of MP analysis with split frequencies equal to 0.009830 (BI), and the effective sample size (ESS) across the two runs is double that of the average ESS (avg ESS) = 402.

The nLSU regions (Figure 2) were based on 13 orders, namely, Agaricales, Atheliales, Boletales, Cantharellales, Corticiales, Gloeophyllales, Gomphales, Hymenochaetales, Polyporales, Russulales, Thelephorales, Trechisporales, and Xenasmatales, while Xenasmatella was separated from the other orders.

The ITS-alone dataset (Figure 3) included sequences from 26 fungal specimens representing 15 species belonging to Xenasma and Xenasmatella. The dataset had an aligned length of 598 characters, of which 267 characters are constant, 74 are variable and parsimony-uninformative, and 257 are parsimony-informative. Maximum parsimony analysis yielded 1 equally parsimonious tree (TL = 629, CI = 0.7329, HI = 0.2671, RI = 0.8301, and RC = 0.6084). The best model for the ITS dataset estimated and applied in the Bayesian analysis was GTR+I+G [lset nst = 6, rates = invgamma; prset statefreqpr = dirichlet (1,1,1,1)]. The Bayesian and ML analyses resulted in a topology similar to MP analysis with split frequencies equal to 0.007632 (BI), and the effective sample size (ESS) across the two runs is double that of the average ESS (avg ESS) = 300.5.

In the ITS sequence analysis (Figure 3), a previously undescribed species was grouped into Xenasmatella with a sister group to X. vaga (Fr.) Stalpers.

Taxonomy

Xenasmatales K.Y. Luo and C.L. Zhao, ord. nov.

MycoBank no.: MB 842882

Type family: Xenasmataceae Oberw.

Basidiomata resupinate. Hyphal systems are monomitic, generative hyphae with clamp connections. Basidia pleural. Basidiospores are colorless.

Xenasmataceae Oberw., Sydowia 19(1–6): 25 (1966).

MycoBank no.: MB 81527

Type genus: Xenasma Donk

Basidiomata resupinate, ceraceous to geletinous. Hyphal systems are monomitic, generative hyphae with clamp connections. Basidia pleural usually with 4 sterigmata and a basal clamp connection. Basidiospores are colorless.

Xenasma Donk, Fungus, Wageningen 27: 25 (1957).

MycoBank no.: MB 18755

Type species: Xenasma rimicola (P. Karst.) Donk.

Basidiomata resupinate, adnate, are ceraceous to gelatinous when fresh, membranaceous when dry, and have a hymenophore smooth. Hyphal system are monomitic, generative hyphae with clamp connections. Cystidia and cystidioles are present. Basidia are cylindrical to subclavate, pleural, usually with 4 sterigmata and a basal clamp connection. Basidiospores are globose to cylindrical, colorless, thin-walled, warted to striate, non-amyloid, and weakly dextrinoid.

Xenosperma Oberw., Sydowia 19(1–6): 45 (1966).

MycoBank no.: MB 18759

Type species: Xenosperma ludibundum (D.P. Rogers and Liberta) Oberw.

Basidiomata resupinate, closely adnate to the substratum, are gelatinous when fresh and pruinose when dry. Hyphal systems are monomitic, generative hyphae with clamp connections. Cystidia are absent. Basidia pleural, usually with 2–4 sterigmata and a basal clamp connection. Basidiospores are angular, colorless, thin-walled, tetrahedral, with some protuberances, IKI–, and CB–.

Xenasmatella Oberw., Sydowia 19(1–6): 28 (1966).

MycoBank no.: MB 18756

Type species: Xenasmatella subflavidogrisea (Litsch.) Oberw. ex Jülich.

Basidiomata resupinate with a gelatinous. Hyphal system with clamped generative hyphae. Cystidia are absent. Basidia pleural, usually with 4 sterigmata and a basal clamp connection. Basidiospores are hyaline, thin-walled, warted, IKI–, and CB–.

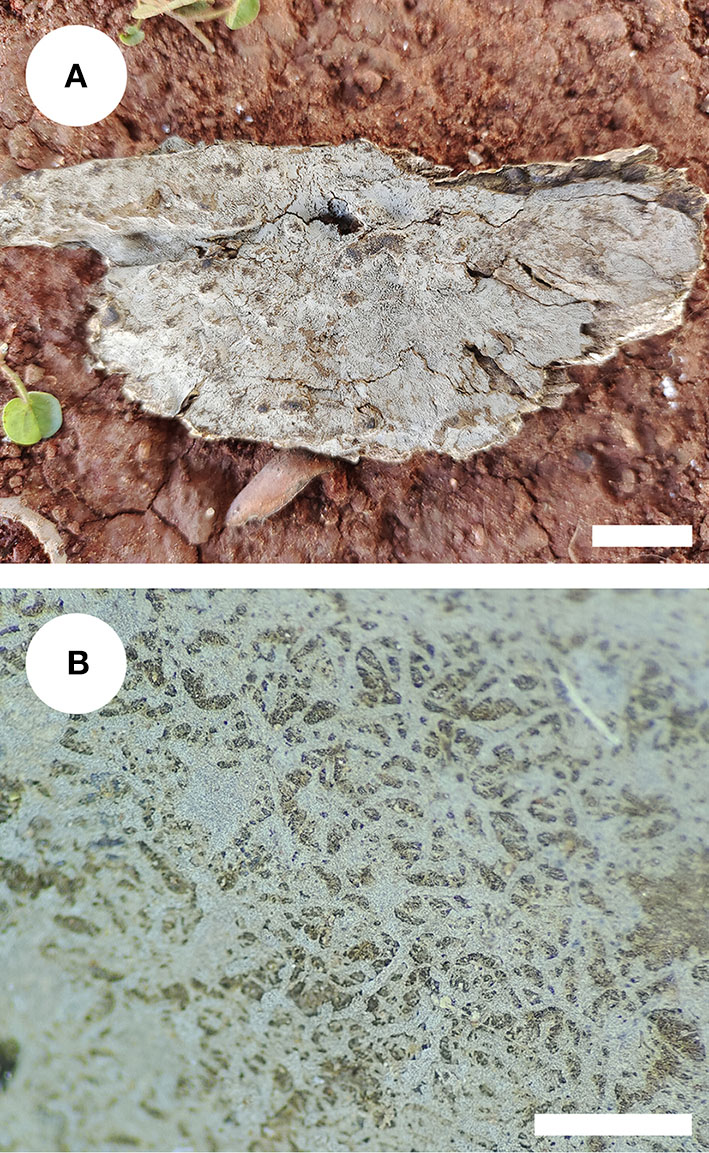

Figure 4

Basidiomata of Xenasmatella nigroidea (holotype). Bars: (A) 1 cm; (B) 1 mm.

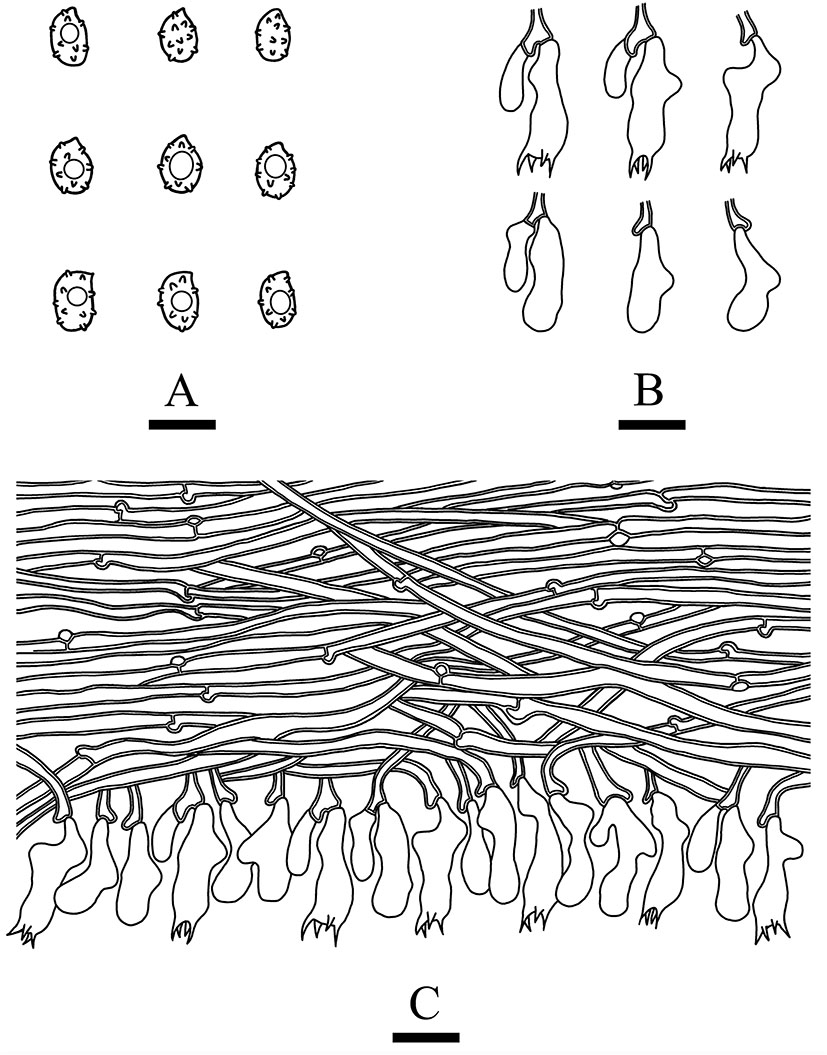

Figure 5

Microscopic structures of Xenasmatella nigroidea (drawn from the holotype). (A) Basidiospores. (B) Basidia and basidioles. (C) A section of hymenium. Bars: (A) 5 μm; (B,C) 10 μm.

Holotype—China. Yunnan Province, Honghe, Pingbian County, Daweishan National Nature Reserve, GPS coordinates 23°42′ N, 103°32′ E, altitude 1,500 m asl., on angiosperm stump, leg. C.L. Zhao, August 3, 2019, CLZhao 18333 (SWFC).

Etymology—nigroidea (Lat.): refers to the black hymenial surface.

Basidiomata: Basidiomata are annuals, resupinate, thin, very hard to separate from substrate, odorless or tasteless when fresh, grayish when fresh, gray to black and brittle when dry, up to 7.5 cm long, 3.5 cm wide, 70–150 μm thick. Hymenial is surface smooth, and byssaceous to reticulate under the lens. Sterile margin indistinct, black, up to 1 mm wide.

Hyphal system: monomitic, generative hyphae with clamp connections, thick-walled, unbranched, 2.5–4 μm in diameter, IKI–, CB–, and tissues unchanged in KOH.

Hymenium: cystidia and cystidioles are absent; basidia are pleural, clavate, with 4 sterigmata and a basal clamp connection, 12.0–18.0 × 4.5–6 μm; basidioles are shaped similar to basidia but slightly smaller.

Basidiospores: ellipsoid, colorless, thin-walled, warted throughout, asperulate with blunt spines up to 0.2 μm long, with one oil drop inside, IKI–, CB–, 3.5–4.5 × 2.5–3.5 μm, L = 4.07 μm, W = 2.87 μm, Q = 1.38–1.45 (n = 60/2).

Type of rot: White rot.

Additional specimen examined: CHINA, Yunnan Province, Honghe, Pingbian County, Daweishan National Nature Reserve, GPS coordinates 23°40′ N, 103°31′ E, altitude 1,500 m asl., on the angiosperm stump, leg. C.L. Zhao, August 3, 2019, CLZhao 18300 (SWFC).

Discussion

There have been debates among mycologists regarding the order level taxonomic status of the Xenasmataceae. Corticioid homobasidiomycetes have a high phylogenetic diversity. Thus, an accurate place for the taxa of Xenasmataceae has not been decided. However, it was only assigned to euagarics clade (Larsson et al., 2004). Later, the Phlebiella family was proposed by Larsson (2007) on the basis of corticioid fungi; however, this group was not placed under any order. Recently, Xenasmataceae was placed under Russulales by He et al. (2019). Zong et al. (2021) studied the specimens and sequences from China and treated this group as Xenasmatella as the phylogenetic datasets showed that this clade does not belong to any order. In the present study (Figure 1), the ITS+nLSU analyses of 13 orders, namely, Agaricales, Atheliales, Boletales, Cantharellales, Corticiales, Gloeophyllales, Gomphales, Hymenochaetales, Polyporales, Russulales, Thelephorales, Trechisporales, and Xenasmatales showed that the taxa of Xenasmataceae form a single lineage with the sequences of Hymenochaetales and Atheliales; and this is similar to the results of Larsson (2007). In the present study (Figure 2), the nLSU analysis showed that the taxa of Xenasmataceae form a single lineage with the sequences of Hymenochaetales and Boletales; and this is similar to the results of Larsson (2007). In the present study (Table 2), we have enumerated morphological differences among the related orders. Therefore, a new fungal order, Xenasmatales, is proposed on the basis of morphological and molecular identification.

Table 2

| Order Name | Morphological characteristics | References |

|---|---|---|

| Agaricales | Hymenophore type gilled, poroid, ridged, veined, spinose, papillate, and smooth; spore deposit color white, pink, brown, purple-brown and black | Fries, 1821–1832, 1828, 1857–1863, 1874 |

| Atheliales | Generally corticioid and athelioid, producing effused, crust like fruiting bodies that are loosely attached to the substrate and with non-differentiated margins | Eriksson et al., 1978, 1981, 1984 |

| Boletales | Includes conspicuous stipitate-pileate forms that mainly have tubular and sometimes lamellate hymenophores or intermediates that show transitions between the two types of hymenophores. Also includes gasteromycetes (puffball-like forms), resupinate or crust-like fungi that produce smooth, merulioid (wrinkled to warted), or hydnoid (toothed) hymenophores, and a single polypore-like species, Bondarcevomyces taxi | Gilbert, 1931; Besl and Bresinsky, 1997; Jarosch, 2001; Larsson et al., 2004 |

| Corticiales | Basidiomata resupinata, effuso-reflexa vel discoidea; hymenophora laevia; systema hypharum monomiticum; dendrohyphidia raro absentia; basidia saepe e probasidiis oriuntur. Cystidia presentia vel absentia. Sporae hyalinae, tenuitunicatae, albae vel aggregatae roseae. | Hibbett et al., 2007 |

| Gloeophyllales | Basidiomata annua vel perennia, resupinata, effuso-reflexa, dimidiata vel pileata; hymenophora laevia, merulioidea, odontioidea vel poroidea. Systema hypharum monomiticum, dimiticum vel trimiticum. Hyphae generativae fibulatae vel efibulatae. Leptocystidia ex trama in hymenium projecta, hyalina vel brunnea, tenuitunicata vel crassitunicata. Basidiosporae laeves, hyalinae, tenuitunicatae, ellipsoideae vel cylindricae vel allantoideae, inamyloideae. Lignum decompositum brunneum vel album. | Hibbett et al., 2007 |

| Gomphales | Basidiomata can be coralloid, unipileate or merismatoid (having a pileus divided into many smaller pilei); the pileus, if present, can be fan- to funnel-shaped | Gonzalez-Avila et al., 2017 |

| Hymenochaetales | Hymenial structure (corticioid, hydnoid or poroid) and basidiocarps (resupinate, pileate or stipitate); the main characters are the xanthochroic reaction, the lack of clamps, the frequent occurrence of setae | Tobias and Michael, 2002 |

| Thelephorales | Basidiospores tuberosae spinosaeque plus minusve coloratae | Oberwinkler, 1975 |

| Trechisporales | Basidiomata resupinata, stipitata vel clavarioidea. Hymenophora laevia, grandinioidea, hydnoidea vel poroidea. Systema hypharum monomiticum vel dimiticum. Hyphae fibulatae, septa hypharum interdum inflata (ampullata). Cystidia praesentia vel absentia. Basidia 4-6 sterigmata formantia. Sporae laeves vel ornatae. Species lignicolae vel terricolae. | Hibbett et al., 2007 |

| Xenasmatales | Basidiomata resupinate. Hyphal system monomitic, generative hyphae with clamp connections. Basidia pleural. Basidiospores colorless. | Present study |

Morphological characteristics of the relevant orders used in this study.

Phlebiella was not deemed to be a legitimately published genus (Duhem, 2010), and transferring to Xenasmatella was proposed. Later, Larsson et al. (2020) studied corticioid fungi (Basidiomycota and Agaricomycetes) and agreed with Duhem (2010), who suggested accepting the genus Xenasmatella. Recently, several mycologists have suggested the replacement of the invalid genus Phlebiella with Xenasmatella on the basis of morphology and molecular analyses (Maekawa, 2021; Zong et al., 2021).

On the basis of ITS dataset, a previous study showed that nine species of Xenasmatella have been reported, of which 6 new species were found in China, namely, X. ailaoshanensis C.L. Zhao ex C.L. Zhao and T.K. Zong, X. gossypina, X. rhizomorpha, X. tenuis, X. wuliangshanensis, and X. xinpingensis. According to our sequence data, Xenasmatella nigroidea was nested into Xenasmatella with strong statistical support (Figure 3), and formed a sister group with X. vaga. However, X. nigroidea is morphologically distinguished from X. vaga by larger basidiospores (5–5.5 × 4–4.5 μm). In addition, it turns dark red or purplish with KOH (Bernicchia and Gorjón, 2010).

Morphological comparisons of Xenasmatella nigroidea and other species are included in Table 3. Xenasmatella nigroidea is similar to X. christiansenii (Parmasto) Stalpers, X. fibrillosa (Hallenb.) Stalpers, X. gossypina, and X. rhizomorpha C.L. Zhao by having gossypine, byssaceous to reticulate hymenial surface, however, X. christiansenii is distinguished from X. nigroidea by its larger basidiospores (6–7 × 4–4.5 μm) and asperulate with blunt spines (up to 1 μm long; Bernicchia and Gorjón, 2010). Xenasmatella fibrillosa differs from X. nigroidea due to the presence of a white to pale yellowish white hymenial surface and longer basidiospores (4.5–5.5 μm; Bernicchia and Gorjón, 2010). Xenasmatella gossypina can be distinguished from X. nigroidea because it has cotton to flocculent basidiomata with a cream to buff hymenial surface and subglobose to globose basidiospores (Zong and Zhao, 2021). Xenasmatella rhizomorpha is separated from X. nigroidea by the clay-buff to cinnamon hymenial surface and the presence of the rhizomorphs (Zong et al., 2021).

Table 3

| Species name | Basidiomata | Hymenial surface | Basidia | Basidiospores | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Xenasmatella nigroidea | Thin, very hard to separate from substrate | Smooth, byssaceous to reticulate under the lens | 12–18 × 4.5–6 μm | Ellipsoid, 3.5–4.5 × 2.5–3.5 μm; asperulate with blunt spines up to 0.2 μm long | Present study |

| X. christiansenii | Fragile | Smooth, pruinose to farinaceous or more or less reticulate | 6–7 × 4–4.5 μm | Ellipsoid, 6–7 × 4–4.5 μm; asperulate with blunt spines up to 1 μm long | Bernicchia and Gorjón, 2010 |

| X. fibrillosa | Thin, fragile | Porulose to reticulate or formed by radially arranged, white to pale yellowish white | 12–15 × 4–5 μm | Ellipsoid, 4.5–5.5 × 3–3.5 μm | Bernicchia and Gorjón, 2010 |

| X. gaspesica | Small spots and becoming a closed coating, firmly attached | Resh smooth and somewhat gelatinous, light gray, dry waxy, white gray | 7–11 × 4–4.5 μm | Ellipsoid, 8–10 × 2–2.5 μm | Grosse-Brauckmann and Kummer, 2004 |

| X. gossypina | Cotton to flocculent | Cream to buff | 14–23.5 × 4–7 μm | Subglobose to globose, 3.3–4.4 × 2.8–4 μm | Zong and Zhao, 2021 |

| X. odontioidea | Colliculosa | Ceraceo-membranacea | 17.5–20 × 4.5–5 μm | Ovale-ellipsoid, 2.5–3.5 μm | Ryvarden and Liberta, 1978 |

| X. rhizomorpha | Presence of the rhizomorph | Clay-buff to cinnamon | 10.5–17.5 × 3.5–6.5 μm | Ellipsoid, 3.1–4.9 × 2.3–3.3 μm | Zong et al., 2021 |

| X. subflavidogrisea | Thin | White to grayish | 10–12 × 4–5 μm | Ellipsoid, 3.5–4.5 × 2–2.5 μm | Bernicchia and Gorjón, 2010 |

| X. vaga | Detachable | Grandinioid | 15–20 × 5–6 μm | Ellipsoid, 5–5.5 × 4–4.5 μm | Bernicchia and Gorjón, 2010 |

Morphological characteristic comparison of Xenasmatella nigroidea and other species.

Xenasmatella nigroidea is similar to X. gaspesica (Liberta) Hjortstam, X. odontioidea Ryvarden & Liberta, X. subflavidogrisea (Litsch.) Oberw. ex Jülich, and X. vaga (Fr.) Stalpers due to the presence of the ellipsoid or narrowly ellipsoid basidiospores. However, X. gaspesica differs from X. nigroidea because it has smaller basidia (7–11 × 4–4.5 μm) and larger basidiospores (8–10 × 2–2.5 μm; Grosse-Brauckmann and Kummer, 2004). Xenasmatella odontioidea can be distinguished from X. nigroidea by its colliculosa hymenial surface and shorter basidiospores (2.5–3.5 μm; Ryvarden and Liberta, 1978). Xenasmatella subflavidogrisea is separated from X. nigroidea due to the presence of a white to grayish hymenial surface, turning dark reddish brown in KOH and narrower basidiospores (2–2.5 μm; Bernicchia and Gorjón, 2010). Xenasmatella vaga differs from X. nigroidea due to its grandinioid hymenial surface and larger basidiospores (5–5.5 × 4–4.5 μm; Bernicchia and Gorjón, 2010).

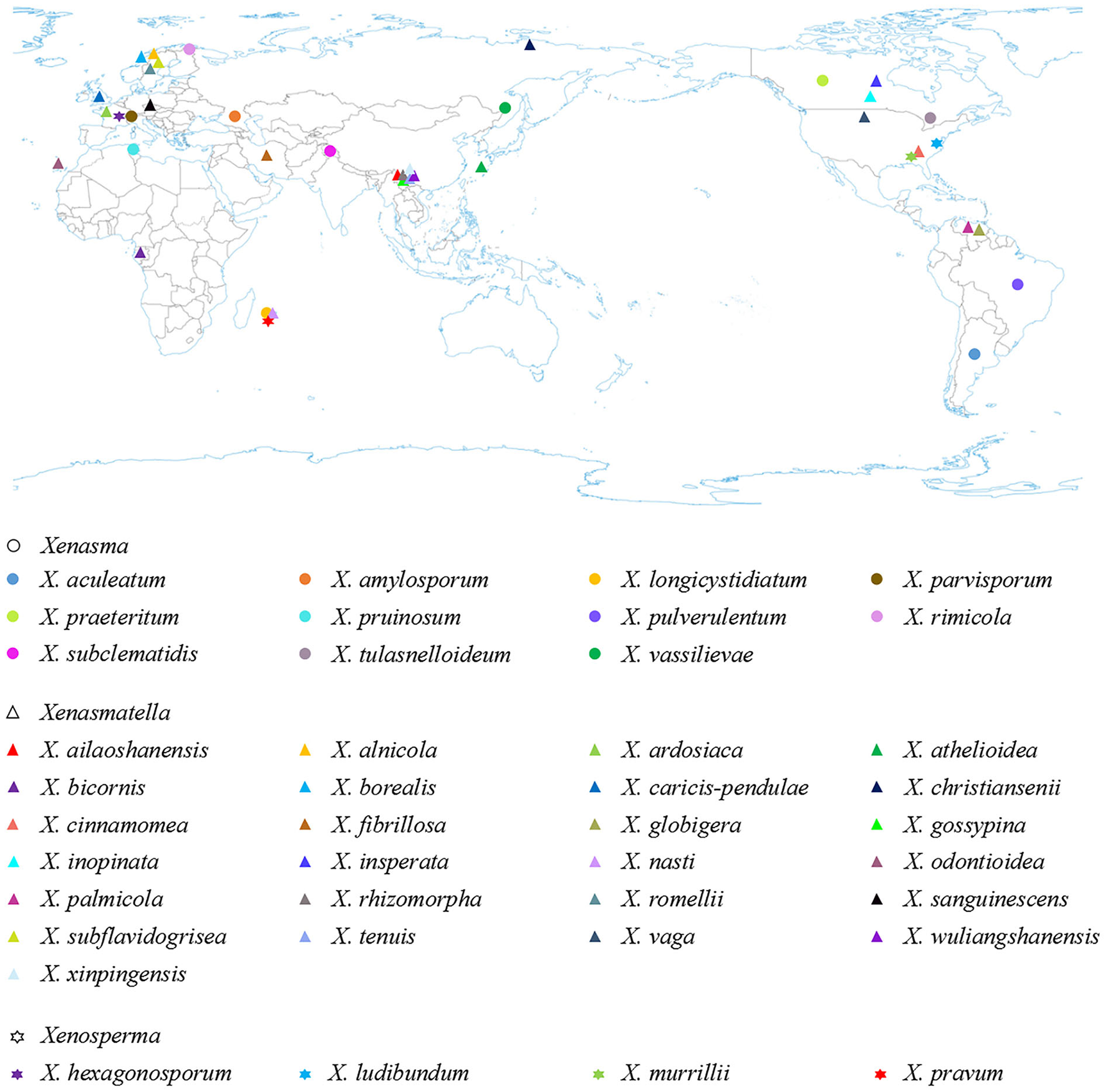

Based on the geographical distribution in America, Asia, and Europe, and ecological habits, white-rot causing Xenasmataceae have been reported in angiosperms and gymnosperms (Figure 6 and Table 4) (Stalpers, 1996; Dai et al., 2004; Hjortstam and Ryvarden, 2005; Bernicchia and Gorjón, 2010; Duhem, 2010; Dai, 2011; Huang et al., 2019; Larsson et al., 2020; Maekawa, 2021; Zong and Zhao, 2021; Zong et al., 2021). Key to 25 accepted species of Xenasmatella worldwide in Table 5. Many wood-decaying fungi have been recently reported worldwide (Zhu et al., 2019; Angelini et al., 2020; Gafforov et al., 2020; Zhao and Zhao, 2021). According to the results of our study on Xenasmatella, all these fungi can be classified into a new taxon (Figure 3). In addition, this study contributes to the knowledge of the fungal diversity in Asia.

Figure 6

The geographic distribution of Xenasmataceae species (holotype) worldwide.

Table 4

| Species name | Geographic distribution | Host-substratum | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Xenasma aculeatum | Argentina | On fructifications of Hypoxylon | Gómez, 1972 |

| X. amylosporum | Primorye | On rotten trunk of Picea jezoensis | Parmasto, 1968 |

| X. longicystidiatum | Réunion | On Rubus alcaefolius | Boidin and Gilles, 2000 |

| X. parvisporum | Czech Republic | On fallen branch of Quercus petraea | Pouzar, 1982 |

| X. praeteritum | Ontario | On wood | Donk, 1957 |

| X. pruinosum | Tunisia | On oak tree, bared and rotten | Donk, 1957 |

| X. pulverulentum | Austria | On rotten wood | Donk, 1957 |

| X. rimicola | Finland | On cracks in bark | Donk, 1957 |

| X. subclematidis | Jammu-Kashmir | On log | Rattan, 1977 |

| X. tulasnelloideum | America | On very rotten wood | Höhnel and Litschauer, 1908 |

| X. vassilievae | Khabarovsk | On fallen trunk of Taxus cuspidata | Parmasto, 1965 |

| Xenasmatella ailaoshanensis | Yunnan | On trunk of Angiospermae | Huang et al., 2019 |

| X. alnicola | Allier | Sur bois humides, aune, saule blane | Bourdot and Galzin, 1928 |

| X. ardosiaca | France | On decayed wood | Bourdot and Galzin, 1928 |

| X. athelioidea | Japan | On rotten trunk of Quercus | Maekawa, 2021 |

| X. bicornis | Gabon | Among shrubs on shore | Boidin and Gilles, 2004 |

| X. borealis | Norway | On rotten Pinus sylvestris | Hjortstam and Larsson, 1987 |

| X. caricis-pendulae | Great Britain | On dead attached leaf of Carex pendula | Roberts, 2007 |

| X. christiansenii | Kamchatka | On fallen branch of Larix kurilensis var. glabra | Parmasto, 1965 |

| X. cinnamomea | Florida | On Magnolia | Burdsall and Nakasone, 1981 |

| X. fibrillosa | Iran | On decayed wood | Hallenberg, 1978 |

| X. globigera | Venezuela | On hardwood | Hjortstam and Ryvarden, 2005 |

| X. gossypina | Yunnan | On trunk of Angiospermae | Zong and Zhao, 2021 |

| X. inopinata | Ontario | On Tsuga canadensis | Jackson, 1950 |

| X. insperata | Ontario | On bark | Jackson, 1950 |

| X. nasti | Reunion | Under Nastus borbonicus | Stalpers, 1996 |

| X. odontioidea | Canary | On decayed wood | Ryvarden and Liberta, 1978 |

| X. palmicola | Venezuela | On palm | Hjortstam and Ryvarden, 2007 |

| X. rhizomorpha | Yunnan | On trunk of Angiospermae | Zong et al., 2021 |

| X. romellii | Sweden | On deciduous wood | Hjortstam, 1983 |

| X. sanguinescens | Czech Republic | On decayed wood | Svrcek, 1973 |

| X. subflavidogrisea | Sweden | On rotten wood of Pinus sylvestris | Jülich, 1979 |

| X. tenuis | Yunnan | On trunk of Angiospermae | Zong et al., 2021 |

| X. vaga | Italy | On Robinia pseudoacacia | Stalpers, 1996 |

| X. wuliangshanensis | Yunnan | On trunk of Angiospermae | Zong and Zhao, 2021 |

| X. xinpingensis | Yunnan | On trunk of Angiospermae | Zong et al., 2021 |

| Xenosperma hexagonosporum | France | On wood of Platanus acerifolia | Boidin and Gilles, 1989 |

| X. ludibundum | Massachusetts | On bark of Quercus and decayed wood of Chamaecyparis thyoides | Jülich, 1979 |

| X. murrillii | Florida | On branch of Juniperus virginiana | Gilbertson and Blackwell, 1987 |

| X. pravum | Réunion | On dead branch | Boidin and Gilles, 1989 |

The geographic distribution and host-substratum of Xenasmataceae species (holotype).

Table 5

| 1. Gloeocystidia present | X. inopinata |

| 1. Cystidia absent | 2 |

| 2. Basidia with 2, 3 sterigmata | X. bicornis |

| 2. Basidia with 4 sterigmata | 3 |

| 3. Basidia sterigmata > 5 μm in length | X. nasti |

| 3. Basidia sterigmata < 5 μm in length | 4 |

| 4. Basidiospores > 5 μm in length | 5 |

| 4. Basidiospores < 5 μm in length | 12 |

| 5. Basidiospores > 4 μm in width | 6 |

| 5. Basidiospores < 4 μm in width | 9 |

| 6. Basidiospores globose | X. ardosiaca |

| 6. Basidiospores ellipsoid | 7 |

| 7. Basidia < 6 μm in width | X. vaga |

| 7. Basidia > 6 μm in width | 8 |

| 8. Growth on dead angiosperm | X. caricis-pendulae |

| 8. Growth on the trunk of gymnosperm | X. christiansenii |

| 9. Basidiospores < 2 μm in width | X. athelioidea |

| 9. Basidiospores > 2 μm in width | 10 |

| 10. Hymenial margin with fimbriae | X. romellii |

| 10. Hymenial margin without fimbriae | 11 |

| 11. Hymenial surface arachnoid or byssoid | X. borealis |

| 11. Hymenial surface smooth | X. insperata |

| 12. Basidiospores subglobose to globose | 13 |

| 12. Basidiospores ellipsoid to subcylindrical | 17 |

| 13. Basidiospores thick-walled | X. globigera |

| 13. Basidiospores thin-walled | 14 |

| 14. Hymenial surface clay-pink to saffron | X. wuliangshanensis |

| 14. Hymenial surface white to grayish or cream to buff | 15 |

| 15. Generative hyphae thick-walled, unbranched | X. xinpingensis |

| 15. Generative hyphae thin-walled, branched | 16 |

| 16. Hymenial surface gossypine to byssaceous | X. gossypina |

| 16. Hymenial surface pruinose to farinaceous | X. ailaoshanensis |

| 17. Generative hyphae thick-walled | 18 |

| 17. Generative hyphae thin-walled | 19 |

| 18. Hymenial surface gray to black | X. nigroidea |

| 18. Hymenial surface clay-buff to cinnamon | X. rhizomorpha |

| 19. Growth on palm | X. palmicola |

| 19. Growth on other plant | 20 |

| 20. Growth on the bark of magnolia | X. cinnamomea |

| 20. Growth on other wood | 21 |

| 21. Basidiospores slightly thick-walled | X. alnicola |

| 21. Basidiospores thin-walled | 22 |

| 22. Basidia barrel-shaped | X. tenuis |

| 22. Basidia cylindrical | 23 |

| 23. Basidiomata ochreous | X. odontioidea |

| 23. Basidiomata white to gray | 24 |

| 24. Basidiospores > 3 μm in width | X. fibrillosa |

| 24. Basidiospores < 3 μm in width | X. subflavidogrisea |

Key to 25 accepted species of Xenasmatella worldwide.

Funding

The research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Project No. 32170004, U2102220) to C-LZ, the Yunnan Fundamental Research Project (Grant No. 202001AS070043) to C-LZ, the High-level Talents Program of Yunnan Province (YNQR-QNRC-2018-111) to C-LZ, and the Yunnan Key Laboratory of Plateau Wetland Conservation, Restoration, and Ecological Services (202105AG070002) to K-YL.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Statements

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/supplementary material.

Author contributions

C-LZ: conceptualization, resources, supervision, project administration, and funding acquisition. C-LZ and K-YL: methodology, software, validation, formal analysis, investigation, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing, and visualization. Both authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1

AngeliniC.VizziniA.JustoA.BizziA.KayaE. (2020). First report of a neotropical agaric (lepiota spiculata, agaricales, basidiomycota) containing lethal α-amanitin at toxicologically relevant levels. Front. Microbiol.11, 1833. 10.3389/fmicb.2020.01833

2

BernicchiaA.GorjónS. P. (2010). Fungi Europaei 12: Corticiaceae s.l.Alassio: Edizioni Candusso.

3

BeslH.BresinskyA. (1997). Chemosystematics of suillaceae and gomphidiaceae (suborder Suillineae). Plant Syst. Evol.206, 223–242. 10.1007/BF00987949

4

BoidinJ.GillesG. (1989). Les Corticiés pleurobasidiés (Basidiomycotina) en France. Cryptogamic Bot.1, 70–79.

5

BoidinJ.GillesG. (2000). Basidiomycètes Aphyllophorales de l'ile de La Reunion. XXI - Suite. Mycotaxon75, 357–387.

6

BoidinJ.GillesG. (2004). Homobasidiomycètes Aphyllophorales non porés à basides dominantes à 2 (3) stérigmates. Bull. Trimest. Soc. Mycol. Fr.119, 1–17.

7

BourdotH.GalzinA. (1928). Hyménomycètes de France : Hétérobasidiés. Homobasidiés gymnocarpes / par MM. l'abbé H. Bourdot et A. Galzin.Paris: Bibliothèque nationale de France, département Sciences et techniques, 786.

8

BurdsallH. H.NakasoneK. K. (1981). New or little known lignicolous aphyllophorales (Basidiomycotina) from southeastern United States. Mycologia73, 454–476. 10.1080/00275514.1981.12021368

9

ChenC. C.ChenC. Y.WuS. H. (2021). Species diversity, taxonomy and multi-gene phylogeny of phlebioid clade (Phanerochaetaceae, Irpicaceae, Meruliaceae) of polyporales. Fungal Divers.111, 1–106. 10.1007/s13225-021-00490-w

10

CuiB. K.DuP.DaiY. C. (2011). Three new species of Inonotus (Basidiomycota, Hymenochaetaceae) from China. Mycol. Prog.10, 107–114. 10.1007/s11557-010-0681-6

11

DaiY. C. (2011). A revised checklist of corticioid and hydnoid fungi in China for 2010. Mycoscience52, 69–79. 10.1007/S10267-010-0068-1

12

DaiY. C. (2012). Polypore diversity in China with an annotated checklist of Chinese polypores. Mycoscience53, 49–80. 10.1007/s10267-011-0134-3

13

DaiY. C.CuiB. K.SiJ.HeS. H.HydeK. D.YuanH. S.et al. (2015). Dynamics of the worldwide number of fungi with emphasis on fungal diversity in China. Mycol. Prog.14, 62. 10.1007/s11557-015-1084-5

14

DaiY. C.WeiY. L.ZhangX. Q. (2004). An annotated checklist of non-poroid Aphyllophorales in China. Ann. Bot. Fennici41, 233–247.

15

DaiY. C.YangZ. L.CuiB. K.WuG.YuanH. S.ZhouL. W.et al. (2021). Diversity and systematics of the important macrofungi in Chinese forests. Mycosystema40, 770–805.

16

DonkM. A. (1957). Notes on resupinate Hymenomycetes IV. Fungus27, 1–29.

17

DuhemB. (2010). Deux corticiés nouveaux méditerranéens à spores allantoïdes. Cryptogam. Mycol.31, 143–152.

18

ErikssonJ.HjortstamK.RyvardenL. (1978). Corticiaceae of North Europe Volume 5: Mycoaciella-Phanerochaete. Oslo: Fungiflora.

19

ErikssonJ.HjortstamK.RyvardenL. (1981). Corticiaceae of North Europe Volume 6: Phlebia-Sarcodontia. Oslo: Fungiflora.

20

ErikssonJ.HjortstamK.RyvardenL. (1984). Corticiaceae of North Europe Volume 7: Schizopora-Suillosporium. Oslo: Fungiflora.

21

FelsensteinJ. (1985). Confidence intervals on phylogenetics: an approach using bootstrap. Evolution39, 783–791. 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1985.tb00420.x

22

FriesE. (1821–1832). Systema Mycologicum, Sistens Fungorum Ordines, Generaet Species Hucusque Cognitas. Gryphiswaldiae: Ernestus Mauritius.

23

FriesE. (1828). Elenchus Fungorum. Vols. I and II. Germany: Greifswald.

24

FriesE. (1857–1863). Monographia Hymenomycetum Sueciae. Vols. I and II. Leffler, C. A.Uppsala: Nabu Press.

25

FriesE. (1874). Hymenomycetes Europaei. Berling; Uppsala: Typis descripsip Ed. p. 755.

26

GafforovY.OrdynetsA.LangerE.YarashevaM.de Mello GugliottaA.SchigelD.et al. (2020). Species diversity with comprehensive annotations of wood-inhabiting poroid and corticioid fungi in Uzbekistan. Front. Microbiol.11, 598321. 10.3389/fmicb.2020.598321

27

Garcia-SandovalR.WangZ.BinderM.HibbettD. S. (2010). Molecular phylogenetics of the Gloeophyllales and relative ages of clades of Agaricomycotina producing a brown rot. Mycologia103, 510–524. 10.3852/10-209

28

GilbertJ. E. (1931). Les Bolets, in les livres du Mycologue. Paris: Le Village du Livre. p. 254.

29

GilbertsonR. L.BlackwellM. (1987). Notes on wood-rotting fungi on Junipers in the Gulf Coast region. II. Mycotaxon28, 369–402.

30

GilbertsonR. L.RyvardenL. (1987). North American Polypores 1-2. Fungiflora; Oslo: Lubrecht and Cramer Ltd. p. 1–433.

31

GómezC. E. (1972). Xenasma y géneros afines de los alrededores de Buenos Aires (Aphyllophorales). Bol Soc Argent Bot14, 269–281.

32

Gonzalez-AvilaA.Contreras-MedinaR.EspinosaD.Luna-VegaI. (2017). Track analysis of the order Gomphales (Fungi: Basidiomycota) in Mexico. Phytotaxa316, 22–38. 10.11646/phytotaxa.316.1.2

33

Grosse-BrauckmannH.KummerV. (2004). Fünf bemerkenswerte Funde corticioider Pilze aus Deutschland. Feddes Repert.115, 90–101. 10.1002/fedr.200311029

34

HaelewatersD.DirksA. C.KapplerL. A.MitchellJ. K.QuijadaL.VandegriftR.et al. (2018). A preliminary checklist of fungi at the Boston Harbor Islands. Northeast. Nat.25, 45–76. 10.1656/045.025.s904

35

HallenbergN. (1978). Wood-Fungi (Corticiaceae, Coniophoraceae, Lachnocladiaceae, Thelephoraceae) in N. Iran. I. Iran. J. Plant Pathol. 14, 38–87.

36

HeM. Q.ZhaoR. L.HydeK. D.BegerowD.KemlerM.YurkovA.et al. (2019). Notes, outline and divergence times of Basidiomycota. Fungal Divers.99, 105–367. 10.1007/s13225-019-00435-4

37

HibbettD. S.BinderM.BischoffJ. F.BlackwellM.CannonP. F.ErikssonO. E.et al. (2007). A higher-level phylogenetic classification of the Fungi. Mycol. Res.111, 509–547. 10.1016/j.mycres.2007.03.004

38

HjortstamK. (1983). Notes on Corticiaceae (Basidiomycetes). XII. Mycotaxon17, 577–584.

39

HjortstamK.LarssonK. H. (1987). Additions to Phlebiella (Corticiaceae, Basidiomycetes), with notes on Xenasma and Sistotrema. Mycotaxon29, 315–319.

40

HjortstamK.RyvardenL. (2005). New taxa and new combinations in tropical corticioid fungi, (Basidiomycotina, Aphyllophorales). Synop. Fungorum20, 33–41.

41

HjortstamK.RyvardenL. (2007). Studies in corticioid fungi from Venezuela III (Basidiomycotina, Aphyllophorales). Synop. Fungorum23, 56–107.

42

HöhnelF.LitschauerV. (1908). Beiträge zur Kenntnis der Corticieen: III. Sitz. K. Akad. Wiss. Math. Naturw. Klasse Abt. I.117, 1081–1124.

43

HuangR. X.ChenJ. Z.WuJ. R.ZhaoC. L. (2019). Phlebiella ailaoshanensis sp. nov. (Polyporales, Basidiomycota) described from China. Phytotaxa419, 105–109. 10.11646/phytotaxa.419.1.8

44

JacksonH. S. (1950). Studies of Canadian Thelephoraceae. VII. Some new species of Corticium, section Athele. Can. J. Res.28, 716–725. 10.1139/cjr50c-045

45

JamesT. Y.StajichJ. E.HittingerC. T.RokasA. (2020). Toward a fully resolved fungal tree of life. Annu. Rev. Microbiol.74, 291–313. 10.1146/annurev-micro-022020-051835

46

JaroschM. (2001). Zur molekularen systematik der boletales: coniophorineae, paxillineae und suillineae. Bibl. Mycol.191, 1–158.

47

JaroschM.BeslH. (2001). Leucogyrophana, a polyphyletic genus of the order boletales (Basidiomycetes). Plant Biol.3, 443–448. 10.1055/s-2001-16455

48

JülichW. (1979). Studies in resupinate Basidiomycetes - V. On some new taxa. Persoonia10, 325–336.

49

KirkP. M.CannonP. F.DavidJ. C.MinterD. W.StalpersJ. A. (2008). Ainsworth and bisby's dictionary of the fungi. 10th ed. Wallingford, Oxon, UK: CAB International Press, 783.

50

LarssonA. (2014). AliView: a fast and lightweight alignment viewer and editor for large data sets. Bioinformatics30, 3276–3278. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu531

51

LarssonE.HallenbergN. (2001). Species delimitation in the Gloeocystidiellum Porosum-Clavuligerum complex inferred from compatibility studies and nuclear RDNA sequence data. Mycologia93, 907–914. 10.1080/00275514.2001.12063225

52

LarssonE.LarssonK. H. (2003). Phylogenetic relationships of Russuloid Basidiomycetes with emphasis on Aphyllophoralean taxa. Mycologia95, 1037–1065. 10.1080/15572536.2004.11833020

53

LarssonK. H. (2007). Re-thinking the classification of corticioid fungi. Mycol. Res.111, 1040–1063. 10.1016/j.mycres.2007.08.001

54

LarssonK. H.LarssonE.KoljalgU. (2004). High phylogenetic diversity among corticioid homobasidiomycetes. Mycol. Res.108, 983–1002. 10.1017/S0953756204000851

55

LarssonK. H.LarssonE.RyvardenL.SpirinV. (2020). Some new combinations of corticioid fungi (Basidiomycota. Agaricomycetes). Synop. Fungorum40, 113–117.

56

LarssonK. H.ParmastoE.FischerM.LangerE.NakasoneK. K.RedheadS. A. (2006). Hymenochaetales: a molecular phylogeny for the hymenochaetoid clade. Mycologia98, 926–936. 10.1080/15572536.2006.11832622

57

MaekawaN. (2021). Taxonomy of corticioid fungi in Japan: present status and future prospects. Mycoscience62, 345–355. 10.47371/mycosci.2021.10.002

58

MillerM. A.PfeifferW.SchwartzT. (2012). The CIPRES science gateway: enabling high-impact science for phylogenetics researchers with limited resources. Assoc. Comput. Mach.39, 1–8. 10.1145/2335755.2335836

59

NúñezM.RyvardenL. (2001). East Asian polypores 2. Synop. Fungorum14, 165–522.

60

NylanderJ. A. A. (2004). MrModeltest v2. Program Distributed by the Author. Uppsala: Evolutionary Biology Centre; Uppsala Univeristy.

61

OberwinklerF. (1966). Primitive Basidiomyceten. Revision einiger Formenkreise von Basidienpilzen mit plastischer Basidie. Sydowia19, 1–72.

62

OberwinklerF. (1975). Eine agaricoide Gattung der Thelephorales. Sydowia28, 359–362.

63

ParmastoE. (1965). Corticiaceae U.R.S.S. I. Descriptiones taxorum novarum. Combinationes novae. Eesti NSV Tead. Akad. TOIM.14, 220–233. 10.3176/biol.1965.2.06

64

ParmastoE. (1968). Conspectus Systematis Corticiacearum. Spain: Euorpa Press. p. 1–261.

65

PetersenJ. H. (1996). Farvekort. The Danish Mycological Society's Colour-Chart.Greve: Foreningen til Svampekundskabens Fremme.

66

PiatekM. (2005). A note on the genus Xenosmatella (Fungi, Basidiomycetes). Polish Bot. J.50, 11–13.

67

PouzarZ. (1982). Taxonomic studies in resupinate fungi I. Ceská Mykol.36, 141–145.

68

RattanS. S. (1977). The resupinate Aphyllophorales of the North Western Himalayas. Bibl. Mycol.60, 1–427.

69

RaynerR. W. (1970). A Mycological Colour Chart. Commonwealth Mycological Institute, Kew and British Mycological Society, Kew, United Kingdom. p. 1–34.

70

RobertsP. J. (2007). Phlebiella caricis-pendulae: A new corticoid fungus from Wales. Synop. Fungorum22, 25–26.

71

RonquistF.TeslenkoM.van der MarkP.AyresD. L.DarlingA.HohnaS.et al. (2012). Mrbayes 3.2: efficient bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst. Biol.61, 539–542. 10.1093/sysbio/sys029

72

RosenthalL. M.LarssonK. H.BrancoS.ChungJ. A.GlassmanS. I.LiaoH. L.et al. (2017). Survey of corticioid fungi in North American pinaceous forests reveals hyperdi-versity, underpopulated sequence databases, and species that are potentially ectomycorrhizal. Mycologia109, 115–127. 10.1080/00275514.2017.1281677

73

RyvardenL.LibertaA. E. (1978). Contribution to the Aphyllophoralles of the Canary Islands 4. Two new species of Trechispora and Xenmastella. Can. J. Bot.56, 2617–2619. 10.1139/b78-314

74

RyvardenL.MeloI. (2014). Poroid fungi of Europe. Synop. Fungorum31, 1–455.

75

SotomeK.HattoriT.OtaY. (2011). Taxonomic study on a threatened polypore, Polyporus pseudobetulinus, and a morphologically similar species, P. subvarius. Mycoscience52, 319–326. 10.1007/S10267-011-0111-X

76

StalpersJ. A. (1996). The aphyllophoraceous fungi II. Keys to the species of the Hericiales. Stud. Mycol.40, 1–185.

77

SvrcekM. (1973). Species novae Corticiacearum e Bohemia. Ceská Mykol. 27, 201–206.

78

SwoffordD. L. (2002). PAUP*: Phylogenetic Analysis Using Parsimony (*and other methods). Version 4.0b10. Sunderland, Massachusetts: Sinauer Associates.

79

TelleriaM. T.MeloI.DuenasM.LarssonK. H.Paz MartinM. P. (2013). Molecular analyses confirm Brevicellicium in Trechisporales. IMA Fungus4, 21–28. 10.5598/imafungus.2013.04.01.03

80

TobiasW.MichaelF. (2002). Classification and phylogenetic relationships of Hymenochaete and allied genera of the Hymenochaetales, inferred from rDNA sequence data and nuclear behaviour of vegetative mycelium. Mycol. Prog.1, 93–104. 10.1007/s11557-006-0008-9

81

VuD.GroenewaldM.de VriesM.GehrmannT.StielowB.EberhardtU.et al. (2019). Large-scale generation and analysis of filamentous fungal DNA barcodes boosts coverage for kingdom fungi and reveals thresholds for fungal species and higher taxon delimitation. Stud. Mycol.92, 135–154. 10.1016/j.simyco.2018.05.001

82

WagnerT.FischerM. (2001). Natural groups and a revised system for the European poroid Hymenochaetales (Basidiomycota) supported by nLSU rDNA sequence data. Mycol. Res.105, 773–782. 10.1017/S0953756201004257

83

WhiteT. J.BrunsT.LeeS.TaylorJ. (1990). “Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics,” in PCR protocols: A Guide to Methods And Applications, eds InnisM. A.GelfandD. H.SninskyJ. J.WhiteT. J. (San Diego, CA: Academic Press), 315–322.

84

WuF.YuanH. S.ZhouL. W.YuanY.CuiB. K.DaiY. C. (2020). Polypore diversity in South China. Mycosystema39, 653–682.

85

WuF.YuanY.ZhaoC. L. (2015). Porpomyces submucidus (Hydnodontaceae, Basidiomycota), a new species from tropical China based on morphological and molecular evidence. Phytotaxa230, 61–68. 10.11646/phytotaxa.230.1.5

86

WuF.ZhouL. W.VlasákJ.DaiY. C. (2022). Global diversity and systematics of Hymenochaetaceae with poroid hymenophore. Fungal Divers.113, 1–192. 10.1007/s13225-021-00496-4

87

ZhaoC. L.WuZ. Q. (2017). Ceriporiopsis kunmingensis sp. nov. (Polyporales, Basidiomycota) evidenced by morphological characters and phylogenetic analysis. Mycol. Prog.16, 93–100. 10.1007/s11557-016-1259-8

88

ZhaoW.ZhaoC. L. (2021). The phylogenetic relationship revealed three new wood-inhabiting fungal species from genus Trechispora. Front. Microbiol.12, 650195. 10.3389/fmicb.2021.650195

89

ZhuL.SongJ.ZhouJ. L.SiJ.CuiB. K. (2019). Species diversity, phylogeny, divergence time and biogeography of the genus Sanghuangporus (Basidiomycota). Front. Microbiol.10, 812. 10.3389/fmicb.2019.00812

90

ZongT. K.WuJ. R.ZhaoC. L. (2021). Three new Xenasmatella (Polyporales, Basidiomycota) species from China. Phytotaxa489, 111–120. 10.11646/phytotaxa.489.2.1

91

ZongT. K.ZhaoC. L. (2021). Morphological and molecular identification of two new species of Phlebiella (Polyporales, Basidiomycota) from southern China. Nova Hedwig.112, 501–514. 10.1127/nova_hedwigia/2021/0628

Summary

Keywords

biodiversity, fungal systematics, ITS, LSU, new taxa, wood-decaying fungi, Xenasmatales, Xenasmatella nigroidea

Citation

Luo K-Y and Zhao C-L (2022) Morphology and multigene phylogeny reveal a new order and a new species of wood-inhabiting basidiomycete fungi (Agaricomycetes). Front. Microbiol. 13:970731. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.970731

Received

16 June 2022

Accepted

08 August 2022

Published

31 August 2022

Volume

13 - 2022

Edited by

Samantha Chandranath Karunarathna, Qujing Normal University, China

Reviewed by

Yusufjon Gafforov, Academy of Science of the Republic of Uzbekistan, Uzbekistan; Kalani Hapuarachchi, Guizhou University, China

Updates

Copyright

© 2022 Luo and Zhao.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Chang-Lin Zhao fungi@swfu.edu.cn

This article was submitted to Microbe and Virus Interactions with Plants, a section of the journal Frontiers in Microbiology

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.