- 1Education and Research, Clinical Research Education and Management Services (CREAMS), Lilongwe, Malawi

- 2Department of Laboratory Science, Dedza District Hospital, Ministry of Health, Dedza, Malawi

- 3Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Queen Elizabeth Central Hospital, Blantyre, Malawi

- 4National Antimicrobial Resistance Coordinating Center, Public Health Institute of Malawi, Lilongwe, Malawi

- 5Research Department, Afya na Haki Institute, Kampala, Uganda

- 6School of Public Health, Mount Kenya University, Thika, Kenya

- 7Department of Pharmacy, School of Health Sciences, University of Zambia, Lusaka, Zambia

- 8Pharmacy Council of Tanzania, Dar Es Salaam, Tanzania

- 9STEM Research Institute, Fairfax, VA, United States

- 10European and Developing Countries Clinical Trials Partnership (EDCTP), Strategic Partnerships and Capacity Development, Cape Town, South Africa

- 11Department of Global Health, Stellenbosch University, Cape Town, South Africa

Background: Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) poses a significant threat in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), where fragile health systems and under-resourced facilities exacerbate its burden. Antimicrobial stewardship (AMS) programs have been introduced as a key strategy to optimize antimicrobial use and curb AMR. However, the successful implementation of AMS in SSA remains limited. This systematic review assessed the implementation determinants of AMS programs in SSA using the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR).

Methods: A systematic search was conducted across PubMed and Google Scholar for articles published between 2018 and 2024, following PRISMA guidelines. Studies were included if they reported on factors influencing AMS implementation in SSA. Data from 31 eligible studies were extracted and mapped according to the CFIR framework's five domains to identify key barriers and facilitators.

Results: Major implementation barriers in SSA included underfunded health systems, limited diagnostic and laboratory infrastructure, lack of context-specific AMS guidelines, weak governance and policy enforcement, and insufficient training of healthcare providers. Enablers included hospital leadership support, stakeholder engagement, and existing global frameworks such as the WHO AWaRe guidelines. The review found poor integration of AMS into national health priorities and limited surveillance data, especially at the primary care level.

Conclusion: AMS implementation in SSA is constrained by systemic, infrastructural, and educational challenges. Strengthening leadership, surveillance systems, healthcare worker training, and the development of context-specific AMS protocols are essential. Effective implementation will require tailored strategies grounded in local realities and supported by strong governance and sustainable funding mechanisms.

Background

AMR is a top public health threat globally, claiming the lives over 1.27 million people annually (Iredell, 2019). Africa has the world's largest mortality rate from AMR infections, resulting in over 27 deaths per 100,000 (Africa CDC, 2024). It is estimated that the death toll from AMR could rise to as high as 10 million deaths annually by 2050 if the situation is left unchecked (Africa CDC, 2024). The fast rise in the incidence of AMR across African countries has led to the implementation of several strategies in the bid to curb its spread. Several studies have shown that measures to prevent infections, such as vaccinations and promoting hand hygiene, as well as improving hygiene in healthcare facilities, more than halves the risk of death and decrease the health burden of AMR (Horizon-europe, n.d.). Such AMS campaigns potentially reduce the burden of drug-resistant infections significantly, and in turn, reduce the morbidity and mortality associated with AMR (Baur et al., 2017).

As AMR continues to spread as far as to second- and third-line antimicrobial agents, the WHO has promoted a people-centered approach, a strategy that empowers individuals and communities to become AMR champions by improving knowledge and promoting responsible antimicrobial use (World Health Organization, 2023). It also supports AMS across all levels of care—community, primary, secondary, tertiary, and national—through practical interventions outlined in WHO's 2021 stewardship guide (WHO, 2022). These include clinician and public education, institutional treatment guidelines, antibiograms, and audit-feedback mechanisms, among others. Despite these tools, WHO acknowledges that local adaptation and implementation remain significant hurdles (WHO, 2022). According to WHO, antimicrobial stewardship (AMS) is defined as a systematic approach to educating and supporting healthcare professionals in following evidence-based guidelines for prescribing and administering antimicrobials (Toolkit AWHOP, 2019). This consists of integrated coherent actions which promotes the prudent use of antimicrobials to help improve patient outcomes across the continuum of care including prescribing antibiotics only when needed, selecting optimal drug regimens, drug dosing, route of administration, and duration of treatment following proper and optimized diagnosis. These actions, coupled with the implementation of infection prevention and control (IPC), enhancing water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH), and optimizing vaccination coverage, can significantly reduce the morbidity and mortality associated with AMR, particularly in developing countries (Lewnard et al., 2024).

To further curb the growing health and economic threat that is AMR, the World Health Organization (WHO) developed the Global Action Plan (GAP) to guide countries in creating comprehensive, inclusive strategies for AMR containment (OMS OM da S, 2017). The GAP emphasizes the continuity of successful treatment and prevention of infectious diseases with effective and safe medicines that are quality-assured, used responsibly, and accessible to all who need them. It also advocates for a continuous multi-sectoral approach to minimize the global impact of AMR and outlines important activities to be undertaken grounded in five key objectives: Improving awareness and understanding of AMR, Strengthening knowledge through surveillance and research, Reducing the incidence of infection, Optimizing the use of antimicrobial agents and Ensuring sustainable investment in countering AMR (OMS OM da S, 2017) at national level, National Action Plans (NAPs) serve as the main framework for country-level implementation of these goals. However, while they exist, their impact remains limited as many SSA countries struggle to translate these efforts into effective local implementation due to Inadequate funding, weak infrastructure, and limited local adaptation contribute to poor uptake of AMS interventions, especially at the primary and community levels (REVIVE, 2020). A report by the WHO in 2023 showed that only 28% (47 of 166 countries that reported for the AMR self-assessment survey) are implementing and monitoring their NAPs (World Health Organization, 2023). Understanding the contextual factors that shape AMS implementation is therefore essential for tailoring strategies that work in these resource-constrained settings.

To address this, implementation science offers useful frameworks for systematically identifying the barriers and facilitators to AMS uptake. One widely used model is the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR), which evaluates complex contextual factors that influence intervention success. The CFIR evaluates contextual factors across 5 domains, with 48 constructs and 19 sub-constructs (Means et al., 2020). The five domains consist of the innovation, the inner setting, the outer setting, individuals, and the implementation process. The inner setting is the place where the intervention is implemented, and the outer setting is the environment. Individuals refer to the people involved in implementing the intervention, and finally, the implementation process comprises activities or strategies deployed to implement the intervention (Means et al., 2020). This provides a better framework to evaluate AMS programs within multiple settings. In SSA, reviews evaluating AMS programs utilizing principles of implementation science in SSA remain limited. This review, therefore, seeks to address that gap by determining the implementation determinants for AMS programs within SSA and provide a description of how these determinants are embedded in complex systems.

Research question

What are the implementation determinants for AMS programs in SSA?

Methods

This systematic review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (Page et al., 2021) reporting checklist to ensure a thorough and transparent presentation of the research process and findings and ensure systematic addressing of all key aspects of the review.

Search strategy

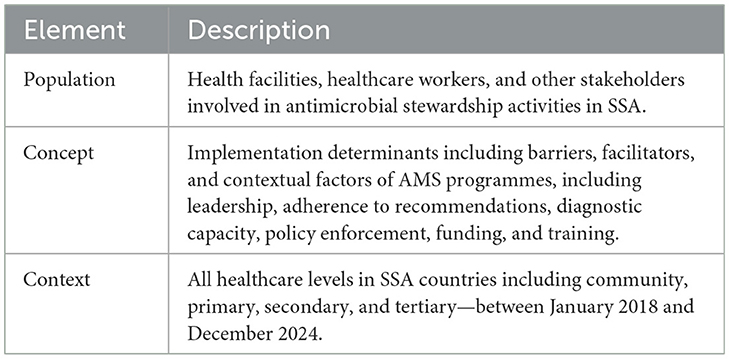

To guide the identification and selection of relevant studies, we applied the PCC (Population–Concept–Context) framework recommended by the Joanna Briggs Institute for systematic reviews of implementation determinants. This framework is summarized in Table 1.

A comprehensive search was conducted in PubMed and Google Scholar between 1 and 28 February 2025 to identify articles on factors associated with AMS programme implementation in SSA, in accordance with PRISMA guidelines.

Literature search strategies were constructed using medical subject headings (MeSH) and text words related to the study's outcomes. Search terms were developed along the following key words: “Antimicrobial resistance,” “Antimicrobial Stewardship programmes,” “determinants” “SSA,” “barriers,” “facilitators” and specific names of countries within SSA. The keywords were combined using Boolean operators and applied truncations where necessary. All the relevant papers' reference lists were also checked for additional articles that could be included in the review.

Inclusion criteria

Eligible studies for this review included original quantitative studies, qualitative observational studies as well as interventional studies published in English from January 1st, 2018 to December 31st 2024 that examined factors influencing the implementation of AMS programmes at any healthcare level in SSA or reported empirical data related to AMS implementation. This time period was purposely established to ensure that the systematic review captured the most recent research studies on the factors associated with the implementation of AMS programs in SSA. This timeframe also follows the formal establishment of the Africa Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Africa CDC) in 2017 and its subsequent leadership role in AMR control across the continent. Study eligibility was also based on the papers.

Exclusion criteria

Non-research articles, duplicates, editorials, commentaries, non-English publications, study protocols, case reports, opinion pieces lacking original data or empirical evidence and studies published before 2018 and outside of the SSA region were excluded from this systematic review. This review also excluded studies on AMR not directly addressing any AMS implementation factors.

Article quality assessment

The quality of each article was assessed using the Cochrane guidelines for assessing bias in observational studies. The appraisal was conducted independently by two reviewers. A simplified quality appraisal checklist adapted from Cochrane guidance for observational studies covering key domains such as study design, sampling strategy, outcome measurement, data reporting, and quality assurance was applied to all included studies to provide an overview of potential sources of bias. The appraisal was conducted independently by two reviewers conducted, and any discrepancies were resolved through discussion until consensus was reached.

Data extraction and synthesis

Retrieved articles were first systematically screened for relevance by two reviewers who independently screened titles/abstracts, assessed full-text eligibility, and applied the quality appraisal checklist. Inter-rater agreement in Rayyan was 99%, indicating almost perfect concordance. Discrepancies were resolved by discussion, where the two reviewers re-examined the original full text together, compared their extracted fields, and discussed the rationale for their interpretations until consensus was reached. Relevant articles that met the inclusion criteria were included in the data extraction process. The two researchers' extracted data independently using a standardized data extraction form was developed in Microsoft Excel based on PRISMA recommendations and the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) developed in Microsoft word. The extracted data covered the following common areas: description of AMS interventions, the implementation context and strategy, reported implementation determinants (barriers, enablers, contextual factors) and the implementation outcomes. After the data had been obtained, a detailed summary was produced, capturing the study characteristics and their respective implementation determinants identified. The Implementation determinants were coded and categorized according to the CFIR domains and construct.

Results

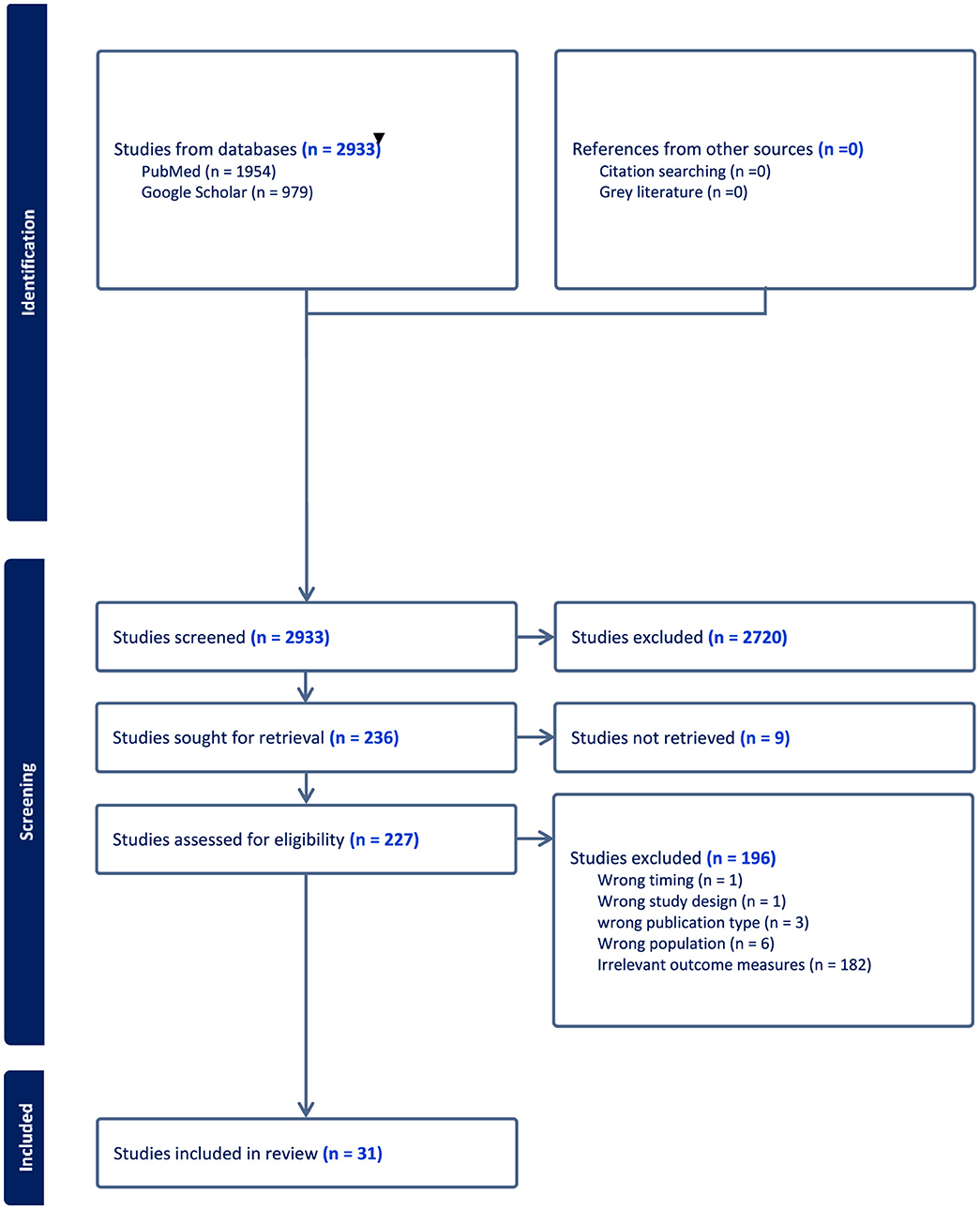

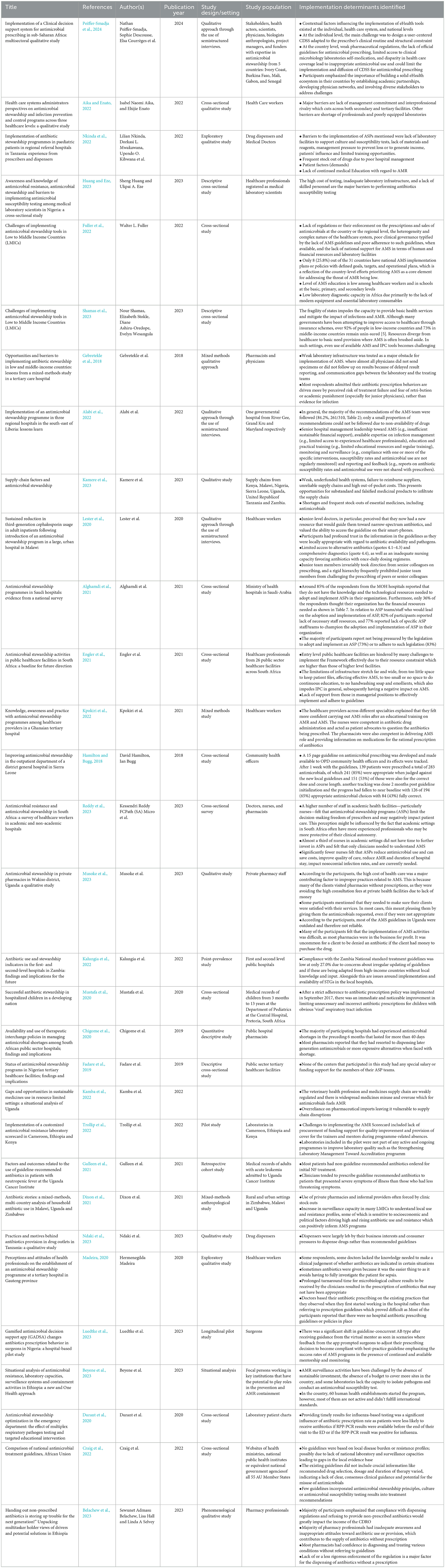

A total of 2,933 articles were initially identified through a comprehensive search of two primary databases: PubMed (1,954 articles) and Google Scholar (979 articles), as depicted in Figure 1. Following a rigorous screening process based on a pre-established inclusion criteria, 31 studies were selected and included in this review. Overall, of the 30 included studies, 4 were judged to be relatively high quality, 18 of moderate quality, and 9 of lower quality based on our adapted Cochrane checklist. The higher-quality studies tended to use mixed-methods, longitudinal, or cohort designs with clearer reporting, while most were observational cross-sectional or qualitative studies with limited methodological detail. Common weaknesses included small sample sizes, reliance on descriptive study designs, and insufficient reporting of study procedures. No studies were excluded on the basis of quality as the quality appraisal was used only to guide the interpretation of findings (Table 2).

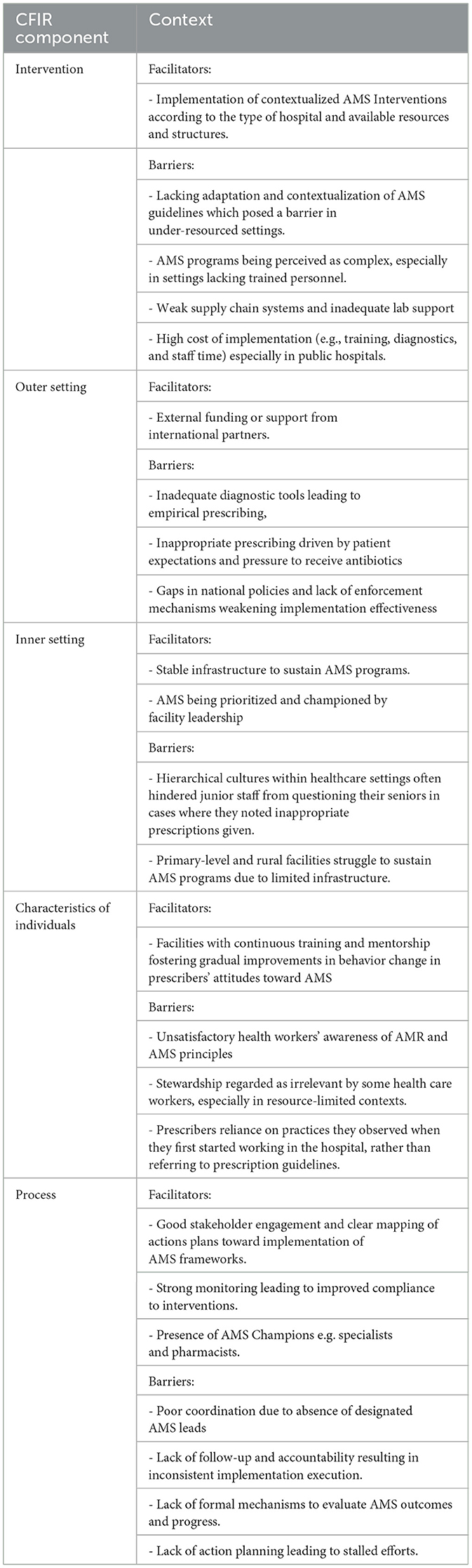

The characteristics of these studies are presented in Table 1. Additionally, data extracted from the included studies were synthesized by two reviewers independently, according to the components of the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR): the outer and inner setting, the individual, the intervention characteristics, and the implementation process, as outlined in Table 3.

The review identified several common implementation determinants affecting AMS in SSA. These included underfunded health systems, characterized by frequent stock-outs of essential antimicrobials and limited laboratory diagnostic capacity, which impairs the confirmation of infections and appropriate antimicrobial use. Furthermore, significant policy and regulatory gaps were observed, with only a few countries having functional AMS implementation plans and weak enforcement of pharmaceutical regulations resulting in widespread over-the-counter sales without prescriptions. The absence of digital health tools, reliance on outdated clinical guidelines, and lack of continuous professional development for healthcare workers were also noted as critical barriers to effective AMS implementation.

Discussion

This systematic review aimed at assessing the implementation determinants of AMS programs in SSA using the consolidated framework for implementation research. The findings highlighted the underlying causes of limited progress in AMS implementations and sustenance among many countries in the sub-Saharan region, despite overwhelming evidence recognizing AMR as a global. The review further offers directions toward necessary targeted interventions that could be most effective to tackle AMR in the SSA context. These results align with existing literature in indicating the need for a comprehensive understanding of contextual, behavioral, technological, and sociocultural factors associated with AMS programs if they are to be successfully implemented and sustained.

Resource constraints and health system fragility

Resource limitation emerged as one of the central barriers to AMS implementation. Many public health facilities in SSA are under-resourced, with budget allocations often favoring high-profile programs such as HIV/AIDS, malaria, and tuberculosis over AMS activities which are perceived as less significant (African Union, 2021). A study by Shamas et al. (2023) highlighted the fragility of health systems in LMICs that consequently impede the provision of basic services. In such settings, specialized programs like AMS are unlikely to receive attention or funding, as limited resources are typically directed toward more immediate healthcare needs (Shamas et al., 2023). Globally, the WHO has advocated for national AMS budgets, yet 74.2% of countries in the WHO African region lack dedicated AMS budget lines, and only 25.8% have national AMS implementation policies (Fuller et al., 2022). These findings suggest that strengthening health system governance and securing dedicated AMS funding by governments in low and middle-income countries is critical for the sustainable implementation of the activities.

Limited diagnostic capabilities and laboratory infrastructure

Low to middle income countries face numerous challenges in implementing effective and sustainable AMR surveillance programs. These challenges include lack of infrastructural and institutional capacities, inadequate AMR surveillance, insufficient investment and human resources, underutilization of available data, and limited dissemination of such data to regulatory bodies. Viewed through a complexity lens, these challenges are not isolated obstacles but interrelated factors within health systems that interact to influence how AMS and AMR surveillance are implemented. Inadequacy of diagnostic microbiology services was found to be a major hindrance in most countries in SSA (Fuller et al., 2022; Lester et al., 2020). This often limits antimicrobial susceptibility testing, as the high cost of testing, inadequate laboratory infrastructure, and a lack of skilled personnel serve as major barriers ultimately promoting empirical prescribing (Huang and Eze, 2023) which runs counter to the goals of AMS. A study by Kamba et al. (2022) emphasized how poorly equipped laboratories, stockouts, and inadequate supply chains hinder effective AMS. Five of the 31 studies in this review also highlighted frequent shortages of essential medicines in public health facilities, which drove patients to private pharmacies and informal providers, undermining stewardship efforts (Dixon et al., 2021). Some hospitals had experienced these stock-outs, lasting over 40 days in the previous six months, prompting pharmacists to dispense later-generation or more expensive alternatives (Chigome et al., 2020). In some cases, a proportion of AMS recommendations could not be followed due to unavailability of the prescribed drugs (Alabi et al., 2022).

These issues stem from weak, underfunded health systems, failure to reimburse suppliers, unreliable supply chains, and high out-of-pocket costs which together create opportunities for substandard and falsified medicinal products to infiltrate the supply chain (Kamere et al., 2023). While the WHO recommends clinical bacteriology services at the primary hospital level, in practice, these are often limited to tertiary facilities and poorly integrated with clinical care (Jacobs et al., 2019). Strengthening bacteriological diagnostic capacity at primary healthcare facilities is essential, as these are often the first point of contact for a wide range of patients. Without access to proper diagnostic services at this level, patients are frequently treated empirically, increasing the risk of inappropriate antibiotic use and the spread of AMR (Lubanga et al., 2024). In ideal situations where rapid diagnostic test results are available in time, clinicians are less likely to prescribe antibiotics unnecessarily. This highlights how timely and accessible diagnostics can support more informed prescribing. However, such tools remain scarce across most settings in SSA (Durant et al., 2020). Additionally, significant data gaps persist regarding AMR in Africa, with estimates of over 40% of SSA countries lacking AMR data. This includesgaps on the true burden of AMR across humans, animals, and the environment, as well as on its transmission, evolution, and asymptomatic carriage (Shomuyiwa et al., 2022). This paucity of data frequently leads to insufficient treatment recommendations tailored to local circumstances.

Lack of context specific AMS guidelines

Although AMS guidelines exist in various forms, their effectiveness is often undermined by poor adherence and a lack of contextual relevance. This review found that even where AMS guidelines were available, adherence remains suboptimal. Contributing factors include limited awareness, poor accessibility, and guidelines that are not well-aligned with local clinical realities (Wehking et al., 2024). In some instances, the available guidelines could not be used as they were outdated and therefore not reliable (Musoke et al., 2023). In a study by Kalungia et al. (2022), compliance to treatment guidelines was as low as 27.0% due to concerns about irregular updating of guidelines and their adaptation from high-income countries without local knowledge and input. Context-specific AMS guidelines, tailored to local antibiotic availability, have been shown to improve practitioners' adherence to recommended practices. In a Tanzanian study, antimicrobial surveillance was key to formulating locally relevant AMS protocols related to high E. coli resistance, particularly against trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and penicillin (Gentilotti et al., 2020). This allows for healthcare providers to optimize empiric therapy, reduce treatment failures, and preserve the effectiveness of remaining antibiotics by aligning prescribing practices with local resistance patterns. For example, locally tailored AMS guidelines in Sierra Leone was associated with improved adherence, underscoring how national context can shape implementation success (Hamilton and Bugg, 2018). Similarly, the WHO AWaRe antibiotic book offers concise, evidence-based guidance on selecting, dosing, and administering antibiotics for over 30 common infections in children and adults across primary and hospital care that can be adapted to local contexts (WHO, 2020). However, the development of such guidelines requires country-level surveillance data generated from adequate laboratories which scarce in SSA due to the absence of sustainable investment, the absence of a budget to cover more sites in the country, and lack the capacity to isolate pathogens and conduct an antimicrobial susceptibility tests (Beyene et al., 2023; Craig et al., 2022). Shomuyiwa et al. (2022) highlighted that over 40% of SSAn countries lack comprehensive AMR data, particularly on community-acquired infections, environmental reservoirs, and AMR mechanisms. These examples illustrate the complex interplay between surveillance capacity, data quality, and guideline adaptation as guidelines remain poorly contextualized without local data; yet poorly contextualized guidelines undermine stewardship and data collection, creating a reinforcing loop typical of complex systems. This highlights a critical gap in the region's ability to generate reliable data necessary for context-specific AMS guideline development, ultimately undermining efforts to improve antimicrobial use and curb resistance.

Governance, regulation, and policy enforcement

Hospital leadership support plays a crucial role in AMS implementation through allocating resources, granting AMS teams the necessary authority, participating in AMS meetings, and helping resolve conflicts (Pauwels et al., 2025). Leadership, governance and regulatory enforcement act as interconnected, system-level factors that together shape the authority, resources and behavior of AMS teams across all levels of the health system. Weak governance and poor regulatory enforcement significantly hinder AMS practices as seen in a Saudi-Arabian study where over 70% of the participants reported not being pressured by the legislation to adopt and implement or to adhere to such legislation (Alghamdi et al., 2021). In the absence of managerial support, healthcare workers may lack the authority, resources, or motivation to implement AMS guidelines consistently and a perception that adherence is optional rather than essential. At the facility level, stewardship efforts require leadership commitment and clear accountability structures, yet major barriers such as lack of management commitment and inter-professional rivalry spanning both secondary and tertiary facilities undermine these efforts (Aika and Enato, 2022). Pollack and Srinivasan (2014) emphasized that hospital management plays a critical role in driving stewardship initiatives.

Among included studies, 10 studies specifically highlight the need for stronger regulatory frameworks to enforce appropriate antimicrobial use, alongside the integration of AMS into broader health governance structures such as establishing academic partnerships, developing physician networks, and involving diverse stakeholders to address challenges which are essential for building a solid e-Health ecosystems (Peiffer-Smadja et al., 2024). They also underscore a lack of managerial commitment and resource prioritization at both national and facility levels—key factors affecting the successful implementation and sustainability of AMS initiatives (Engler et al., 2021; Belachew et al., 2023). In the absence of strict regulatory oversight, drug dispensers may prioritize business interests and respond to consumer demand, frequently dispensing antibiotics contrary to established guidelines (Ndaki et al., 2023). This further calls for clear penalties to entities that contravene laws related to the sale of controlled antibiotics over the counter in drug stores and unregistered pharmacies. For example, In Saudi Arabia, the Ministry of Health enacted a nationwide antibiotic restriction policy in 2018, making it illegal to dispense antibiotics in private pharmacies without a valid prescription. This came with strict penalties including fines of up to 100,000 SAR, cancellation of pharmacy licensing, and even potential imprisonment. As a result, the proportion of pharmacies dispensing antibiotics without prescriptions dropped dramatically from nearly 97% to around 12%, according to simulated client studies (Bin Abdulhak et al., 2011). Similarly, the department of Pediatrics at the Central Hospital, Pretoria, South Africa saw an immediate and noticeable improvement in limiting unnecessary and incorrect antibiotic prescriptions for children with obvious viral respiratory tract infections after a strict adherence to an antibiotic prescription policy was implemented in September 2017 (Mustafa et al., 2020).

Knowledge and training of healthcare providers

This review found widespread gaps in AMS knowledge among healthcare workers, rooted in poor awareness from basic through secondary education and worsened by limited ongoing training on AMR (Fuller et al., 2022; Nkinda et al., 2022). In some cases, prescribers lacked the knowledge needed to make a clinical judgment of whether antibiotics are indicated in certain situations (Madeira, 2020). A study among pharmacists and physicians revealed that most respondents' prescription behaviors were driven more by the perceived risk of treatment failure and fear of retribution or academic punishment rather than by clear clinical evidence of infection (Gebretekle et al., 2018). There was also a tendency among clinicians to prescribe guideline recommended antibiotics to patients that presented severe symptoms of illness than those who had less threatening symptoms (Gulleen et al., 2021). In some cases, prescribers undermined existing guidelines and based their antibiotic prescriptions on the existing practices that they observed when they first started working in the hospital rather than referring to prescription guidelines while others preferred to protect their clinical autonomy as they felt AMS programs limit their decision-making freedom and may negatively impact patient care (Reddy et al., 2023).

This clearly shows how AMS guidelines are undermined by healthcare workers even when they are readily available. For example, a study in Thailand reported that the stewardship team lacked the authority to directly intervene in prescribing practices; consequently, their recommendations were often ignored by individual clinicians (Anugulruengkitt et al., 2025). Our review also found that pre-service training on AMS was inconsistently incorporated into health professional curricula, with seven of the included studies calling for continuous professional development to keep practitioners updated on evolving AMR trends as they felt more confident carrying out AMS roles after an educational training on AMR and AMS (Kpokiri et al., 2022). There was however in some instances, a notable shift in guideline adherence among clinicians after receiving guidance from a mentor, illustrating that continued mentorship and monitoring can greatly improve compliance with best-practice AMS guidelines (Luedtke et al., 2023). These findings underscore the urgent need to institutionalize AMS training at both pre-service and in-service levels to ensure healthcare professionals are well-equipped to implement effective stewardship practices from the outset of their careers. This also clearly shows how governance gaps, prescriber behaviors, and training practices do not act in isolation but are inter-connected, making AMS implementation more complex especially in SSA contexts.

Limited funding for AMS programs

A majority of the health care institutions in SSA are public, government owned facilities that are supported by national budgets. Health care financing is at the core of multiple implementation challenges noted in this study. As highlighted by Shamas et al. (2023), the fragility of LMICs impede capacity to provide basic health services where resources diverge from healthcare to basic need provision. Consequently, there is hardly any procurement of funding support for quality improvement, provision of cover for AMS trainers and mentors during programme-related absences, or special salary or funding support for members of their ASP teams. No Matches Found This was demonstrated repeatedly at national and facility levels in this review where resources diverge from healthcare to basic need provision where AMS is often brushed aside. In such settings, even use of available AMS and IPC tools becomes challenging as resources are diverged to other competing priorities such as acquisition of pharmaceuticals, tuberculosis and HIV/AIDS programs (Shamas et al., 2023). The Global Action Plan on AMR calls for LMIC's to allocate dedicated AMR funds toward implementation of AMR strategies, however there are low country efforts in the region as demonstrated by the lack of budget lines for AMS activities in over 70% of the 47 member states of the WHO African region and only 25.8% of the states having a national AMS implementation policy (WHO, 2021). Although national action plans on AMR are publicly available in some countries, with at least one individual responsible for AMR nationally, it appears that commitments on AMR made in the often-comprehensive NAPs are rarely met on time, exhibiting weak accountability for AMR results (Harant, 2022). This calls for strengthened governance of AMR and stewardship, raising an awareness of AMR among key stakeholders and the prioritization of AMR in the region amidst other competing priorities. At facility level, successful AMS relies on a strong commitment from senior hospital management leadership, accountability, and responsibilities, among other core elements (Pollack and Srinivasan, 2016).

Study limitations

Our review used the CFIR to organize and synthesize findings from studies that did not use implementation science frameworks at any point. This required retrospective mapping of reported determinants onto CFIR domains, which may introduce interpretive bias and limit the precision of categorization of some of the identified themes. The review focused on SSA, and while regionally representative, some countries were underrepresented due to a limited published literature. Due to the use of the English language in our search strategy, some studies could have been missed with equally important findings from Francophone and Lusophone countries within SSA. This review relied on PubMed and Google Scholar for article retrieval and did not include gray literature which may have excluded relevant unpublished or non-indexed reports. In addition, the majority of included studies were observational and descriptive, with small sample sizes and limited methodological detail, which may affect the strength and generalizability of the findings.

Future research directions

Future research should prioritize the use of other implementation science frameworks to evaluate AMS initiatives in SSA. Such approaches will help generate deeper insights into the contextual, behavioral, and organizational factors influencing program outcomes which will in the end improve the impact of AMS programs. Operational research focused on improving the uptake and adaptation of AMS guidelines in diverse healthcare settings is urgently needed, particularly in under-resourced rural and peri-urban environments. Further studies should also investigate community-level AMS interventions, such as school-based education, engagement with traditional healers, and public awareness campaigns, to better understand how grassroots strategies can complement institutional efforts. Future research should also link hospital AMS initiatives to wider One Health contexts since antibiotic use in community pharmacies, veterinary practice, agriculture and environmental factors are interconnected with hospital practices. Integrating these domains will be important for developing sustainable stewardship strategies. Future research should also explore AMS financing in low- and middle-income countries, focusing on public-private partnerships, donor support, and domestic funding to identify strategies for sustainable program implementation. There is also a need for longitudinal studies assessing the long-term impact of AMS implementation on prescribing behaviors and AMR trends. This will be critical in guiding policies and refining stewardship approaches across the region.

Recommendations

To effectively address the implementation challenges of AMS programs in SSA, there is a critical need to institutionalize AMS training at both pre-service and in-service levels across all cadres of healthcare professionals. This will build foundational knowledge, promote adherence to guidelines, and foster a culture of rational antimicrobial use from the onset of clinical practice. Equally important is investing in diagnostic capacity, particularly at primary healthcare levels, to enable evidence-based prescribing and reduce the prevalent reliance on empirical treatment approaches, as highlighted in numerous studies. Countries should also prioritize the development of context-specific AMS guidelines informed by local resistance patterns and available resources that are accessible, practical, and adaptable to real-world clinical scenarios.

Leadership commitment, allocation of dedicated budget lines for AMS activities, and clear accountability frameworks is crucial to support program sustainability and integration into routine care. Several studies in this review highlighted that, without political and financial commitment, other AMS interventions struggled to take root or were short-lived. Additionally, policy enforcement must be intensified to curb inappropriate antimicrobial sales, particularly over-the-counter access in unregulated settings as evidence from included studies consistently showed widespread over the counter antibiotic misuse, underscoring the urgency of regulatory action. Regulatory bodies should actively monitor compliance and implement penalties where necessary. Finally, it is crucial to foster opportunities for sharing best practices, harmonizing data systems, and leveraging technical and financial support for AMS implementation regional through collaboration and partnerships with international organizations.

Alongside long-term changes, there is also need for immediate improvement measures in AMS implementation, including training healthcare professionals at both pre-service and in-service levels to enhance their knowledge and encourage rational prescribing. There is also need for AMS champions and mentorship programmes that will help motivate staff and improve adherence.

Conclusion

This review highlights the multifaceted challenges impeding the effective implementation of AMS programs across SSA. While AMS is globally recognized as essential to combating AMR, its integration into fragile health systems is undermined by limited funding, poor diagnostic infrastructure, weak regulatory enforcement, and insufficient training of healthcare workers. Addressing these gaps requires dedicated investment, contextual adaptation of guidelines, and sustained political and institutional commitment. A complexity-informed, implementation science approach such as the CFIR proves critical for designing and evaluating stewardship programs that can thrive in diverse African contexts.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

TK: Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Validation, Writing – original draft. AB: Validation, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. LK: Writing – review & editing. VM: Writing – review & editing. GM: Writing – review & editing. GH: Writing – review & editing. SS: Writing – review & editing. AA: Writing – review & editing. SM: Writing – review & editing. AM: Writing – review & editing. GC: Writing – review & editing. CM: Writing – review & editing. TM: Writing – review & editing. JC: Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. SuC: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. DC: Writing – review & editing. SeC: Writing – review & editing. VH: Writing – review & editing. CH: Writing – review & editing. GL: Writing – review & editing. CC: Writing – review & editing. TN: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Validation, Supervision. AL: Writing – original draft, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Methodology, Data curation, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the authors of the original studies included in this systematic review and all contributing authors at any point during the production of this systematic review.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Africa CDC (2024). Antimicrobial Resistance: New Report Warns of Growing Threat. Africa CDC. Available online at: https://africacdc.org/news-item/antimicrobial-resistance-new-report-warns-of-growing-threat/ (Accessed August 1, 2025).

Aika, I. N., and Enato, E. (2022). Health care systems administrators perspectives on antimicrobial stewardship and infection prevention and control programs across three healthcare levels: a qualitative study. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control. 11, 1–9. doi: 10.1186/s13756-022-01196-7

Alabi, A. S., Picka, S. W., Sirleaf, R., Ntirenganya, P. R., Ayebare, A., Correa, N., et al. (2022). Implementation of an antimicrobial stewardship programme in three regional hospitals in the south-east of Liberia: lessons learned. JAC-Antimicrobial Resist. 4:dlac069. doi: 10.1093/jacamr/dlac069

Alghamdi, S., Berrou, I., Aslanpour, Z., Mutlaq, A., Haseeb, A., Albanghali, M., et al. (2021). Antimicrobial stewardship programmes in saudi hospitals: evidence from a national survey. Antibiotics 10, 1–11. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics10020193

Anugulruengkitt, S., Jupimai, T., Wongharn, P., and Puthanakit, T. (2025). Barriers in implementing antibiotic stewardship programmes at paediatric units in academic hospitals in Thailand: a qualitative study. BMJ Open 15, 1–8. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2024-092509

Baur, D., Gladstone, B. P., Burkert, F., Carrara, E., Foschi, F., Döbele, S., et al. (2017). Effect of antibiotic stewardship on the incidence of infection and colonisation with antibiotic-resistant bacteria and Clostridium difficile infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 17, 990–1001. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30325-0

Belachew, S. A., Hall, L., and Selvey, L. A. (2023). “Handing out non-prescribed antibiotics is storing up trouble for the next generation!” Unpacking multistakeholder views of drivers and potential solutions in Ethiopia. BMC Health Serv. Res. 23, 1–14. doi: 10.1186/s12913-023-09819-4

Beyene, A. M., Andualem, T., Dagnaw, G. G., Getahun, M., LeJeune, J., and Ferreira, J. P. (2023). Situational analysis of antimicrobial resistance, laboratory capacities, surveillance systems and containment activities in Ethiopia: a new and one health approach. One Heal. 16:100527. doi: 10.1016/j.onehlt.2023.100527

Bin Abdulhak, A. A., Altannir, M. A., Almansor, M. A., Almohaya, M. S., Onazi, A. S., Marei, M. A., et al. (2011). Non prescribed sale of antibiotics in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia: a cross sectional study. BMC Public Health. 11:538. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-538

Chigome, A. K., Matlala, M., Godman, B., and Meyer, J. C. (2020). Availability and use of therapeutic interchange policies in managing antimicrobial shortages among south african public sector hospitals; findings and implications. Antibiotics 9, 1–11. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics9010004

Craig, J., Hiban, K., Frost, I., Kapoor, G., Alimi, Y., Varma, J. K., et al. (2022). Comparison of national antimicrobial treatment guidelines, African Union. Bull. World Health Organ. 100, 50–59. doi: 10.2471/BLT.21.286689

Dixon, J., Macpherson, E. E., Nayiga, S., Manyau, S., Nabirye, C., Kayendeke, M., et al. (2021). Antibiotic stories: a mixed-methods, multi-country analysis of household antibiotic use in Malawi, Uganda and Zimbabwe. BMJ Glob. Heal. 6, 1–15. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2021-006920

Durant, T. J. S., Kubilay, N. Z., Reynolds, J., Tarabar, A. F., Dembry, L. M., Peaper, D. R., et al. (2020). Antimicrobial stewardship optimization in the emergency department: the effect of multiplex respiratory pathogen testing and targeted educational intervention. J. Appl. Lab. Med. 5, 1172–1183. doi: 10.1093/jalm/jfaa130

Engler, D., Meyer, J. C., Schellack, N., Kurdi, A., and Godman, B. (2021). Antimicrobial stewardship activities in public healthcare facilities in South Africa: a baseline for future direction. Antibiotics 10, 1–23. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics10080996

Fadare, J. O., Ogunleye, O., Iliyasu, G., Adeoti, A., Schellack, N., Engler, D., et al. (2019). Status of antimicrobial stewardship programmes in Nigerian tertiary healthcare facilities: findings and implications. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 17, 132–136. doi: 10.1016/j.jgar.2018.11.025

Fuller, W. L., Aboderin, A. O., Yahaya, A., Adeyemo, A. T., Gahimbare, L., Kapona, O., et al. (2022). Gaps in the implementation of national core elements for sustainable antimicrobial use in the WHO-African region. Front. Antibiot. 1:1047565. doi: 10.3389/frabi.2022.1047565

Gebretekle, G. B., Mariam, D. H., Abebe, W., Amogne, W., Tenna, A., Fenta, T. G., et al. (2018). Opportunities and barriers to implementing antibiotic stewardship in low and middle-income countries: lessons from a mixed-methods study in a tertiary care hospital in Ethiopia. PLoS ONE 13:e0208447. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0208447

Gentilotti, E., De Nardo, P., Nguhuni, B., Piscini, A., Damian, C., Vairo, F., et al. (2020). Implementing a combined infection prevention and control with antimicrobial stewardship joint program to prevent caesarean section surgical site infections and antimicrobial resistance: a Tanzanian tertiary hospital experience. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 9:69. doi: 10.1186/s13756-020-00740-7

Gulleen, E. A., Adams, S. V., Chang, B. H., Falk, L., Hazard, R., Kabukye, J., et al. (2021). Factors and outcomes related to the use of guideline-recommended antibiotics in patients with neutropenic fever at the Uganda Cancer Institute. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 8:ofab307. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofab307

Hamilton, D., and Bugg, I. (2018). Improving antimicrobial stewardship in the outpatient department of a district general hospital in Sierra Leone. BMJ Open Qual. 7, 1–6. doi: 10.1136/bmjoq-2018-000495

Harant, A. (2022). Assessing transparency and accountability of national action plans on antimicrobial resistance in 15 African countries. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 11, 1–16. doi: 10.1186/s13756-021-01040-4

Horizon-europe (n.d.). Tackling Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) through RandD in Novel and Existing Antimicrobials. Addiss Abbaba: Horizon-europe. Available online at: https://www.horizon-europe.gouv.fr/tackling-antimicrobial-resistance-amr-through-rd-novel-and-existing-antimicrobials-36612 (Accessed August 1, 2025).

Huang, S., and Eze, U. A. (2023). Awareness and knowledge of antimicrobial resistance, antimicrobial stewardship and barriers to implementing antimicrobial susceptibility testing among medical laboratory scientists in Nigeria: a cross-sectional study. Antibiotics 12:815. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics12050815

Jacobs, J., Hardy, L., Semret, M., Lunguya, O., Phe, T., Affolabi, D., et al. (2019). Diagnostic bacteriology in District Hospitals in Sub-Saharan Africa: at the forefront of the containment of antimicrobial resistance. Front. Med. 6:205. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2019.00205

Kalungia, A. C., Mukosha, M., Mwila, C., Banda, D., Mwale, M., Kagulura, S., et al. (2022). Antibiotic use and stewardship indicators in the first- and second-level hospitals in Zambia: findings and implications for the future. Antibiotics 11, 1–17. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics11111626

Kamba, P. F., Nambatya, W., Aguma, H. B., Charani, E., and Rajab, K. (2022). Gaps and opportunities in sustainable medicines use in resource limited settings: a situational analysis of Uganda. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 88, 3936–3942. doi: 10.1111/bcp.15324

Kamere, N., Rutter, V., Munkombwe, D., Aywak, D. A., Muro, E. P., Kaminyoghe, F., et al. (2023). Supply-chain factors and antimicrobial stewardship | Facteurs liés aux chaînes d'approvisionnement et gestion des antimicrobiens | Factores de la cadena de suministro y administración antimicrobiana. Bull. World Health Organ. 101, 403–411. doi: 10.2471/BLT.22.288650

Kpokiri, E. E., Ladva, M., Dodoo, C. C., Orman, E., Aku, T. A., Mensah, A., et al. (2022). Knowledge, awareness and practice with antimicrobial stewardship programmes among healthcare providers in a ghanaian tertiary hospital. Antibiotics 11, 1–11. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics11010006

Lester, R., Haigh, K., Wood, A., Macpherson, E. E., Maheswaran, H., Bogue, P., et al. (2020). Sustained reduction in third-generation cephalosporin usage in adult inpatients following introduction of an antimicrobial stewardship program in a large, urban hospital in Malawi. Clin. Infect. Dis. 71, E478–E486. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa162

Lewnard, J. A., Charani, E., Gleason, A., Hsu, L. Y., Khan, W. A., Karkey, A., et al. (2024). Burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in low-income and middle-income countries avertible by existing interventions: an evidence review and modelling analysis. Lancet 403, 2439–2454. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(24)00862-6

Lubanga, A. F., Bwanali, A. N., Kambiri, F., Harawa, G., Mudenda, S., Mpinganjira, S. L., et al. (2024). Tackling antimicrobial resistance in sub-Saharan Africa: challenges and opportunities for implementing the new people-centered WHO guidelines. Expert Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 22, 379–386. doi: 10.1080/14787210.2024.2362270

Luedtke, S., Wood, C., Olufemi, O., Okonji, P., Kpokiri, E. E., Musah, A., et al. (2023). Gamified antimicrobial decision support app (GADSA) changes antibiotics prescription behaviour in surgeons in Nigeria: a hospital-based pilot study. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 12:141. doi: 10.1186/s13756-023-01342-9

Madeira, H. (2020). Perceptions and attitudes of health professionals on the establishment of an antimicrobial stewardship programme at a tertiary hospital in gauteng province. Otonomi 20, 396–406. Available online at: https://hdl.handle.net/10539/31623

Means, A. R., Kemp, C. G., Gwayi-Chore, M. C., Gimbel, S., Soi, C., Sherr, K., et al. (2020). Evaluating and optimizing the consolidated framework for implementation research (CFIR) for use in low- And middle-income countries: a systematic review. Implement Sci. 15, 1–20. doi: 10.1186/s13012-020-0977-0

Musoke, D., Lubega, G. B., Gbadesire, M. S., Boateng, S., Twesigye, B., Gheer, J., et al. (2023). Antimicrobial stewardship in private pharmacies in Wakiso district, Uganda: a qualitative study. J. Pharm. Policy Pract. 16, 1–13. doi: 10.1186/s40545-023-00659-5

Mustafa, F., Koekemoer, L. A., Green, R. J., Turner, A. C., Becker, P., van Biljon, G., et al. (2020). Successful antibiotic stewardship in hospitalised children in a developing nation. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 23, 217–220. doi: 10.1016/j.jgar.2020.09.014

Ndaki, P. M., Mwanga, J. R., Mushi, M. F., Konje, E. T., Fredricks, K. J., Kesby, M., et al. (2023). Practices and motives behind antibiotics provision in drug outlets in Tanzania: a qualitative study. PLoS ONE 18:e0290638. Available from: doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0290638

Nkinda, L., Mwakawanga, D. L., Kibwana, U. O., Mikomangwa, W. P., Myemba, D. T., Sirili, N., et al. (2022). Implementation of antibiotic stewardship programmes in paediatric patients in regional referral hospitals in Tanzania: experience from prescribers and dispensers. JAC-Antimicrob. Resist. 4, 1–8. doi: 10.1093/jacamr/dlac118

Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., et al. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71

Pauwels, I., Versporten, A., Ashiru-Oredope, D., Costa, S. F., Maldonado, H., Porto, A. P. M., et al. (2025). Implementation of hospital antimicrobial stewardship programmes in low- and middle-income countries: a qualitative study from a multi-professional perspective in the Global-PPS network. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 14, 1–14. doi: 10.1186/s13756-025-01541-6

Peiffer-Smadja, N., Descousse, S., Courrèges, E., Nganbou, A., Jeanmougin, P., Birgand, G., et al. (2024). Implementation of a clinical decision support system for antimicrobial prescribing in sub-Saharan africa: multisectoral qualitative study. J. Med. Internet Res. 26:45122. doi: 10.2196/45122

Pollack, L. A., and Srinivasan, A. (2014). Core elements of hospital antibiotic stewardship programs from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Clin. Infect. Dis. Off. Publ. Infect. Dis. Soc. Am. 59, S97–S100. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu542

Pollack, L. A., and Srinivasan, A. (2016). Ion core elements of hospital antibiotic stewardship programs from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevent Loria. Clin. Infect. Dis. 176, 139–148.

Reddy, K., Ramsamy, Y., Swe Swe-Han, K., Nana, T., Black, M., Kolojane, M., et al. (2023). Antimicrobial resistance and antimicrobial stewardship in South Africa: a survey of healthcare workers in academic and nonacademic hospitals. Antimicrob. Steward Healthc. Epidemiol. 3, 1–7. doi: 10.1017/ash.2023.483

REVIVE (2020). Moving from Paper to Action – The Status of National AMR Action Plans in African Countries – by Mirfin Mpundu – REVIVE. Available online at: https://revive.gardp.org/moving-from-paper-to-action-the-status-of-national-amr-action-plans-in-african-countries/ (Accessed August 1, 2025).

Shamas, N., Stokle, E., Ashiru-Oredope, D., and Wesangula, E. (2023). Challenges of implementing antimicrobial stewardship tools in Low to Middle Income Countries (LMICs). Infect. Prev. Pract. 5:100315. doi: 10.1016/j.infpip.2023.100315

Shomuyiwa, D. O., Lucero-Prisno, D. E., Manirambona, E., Suleman, M. H., Rayan, R. A., Huang, J., et al. (2022). Curbing antimicrobial resistance in post-COVID Africa: challenges, actions and recommendations. Heal. Sci. Rep. 5:hsr2.771. doi: 10.1002/hsr2.771

Toolkit AWHOP (2019). Antimicrobial stewardship programmes in health-care facilities in low- and middle-income countries: a WHO practical toolkit. Antimicrob. Resist. 1:dlz072. doi: 10.1093/jacamr/dlz072

Trollip, A., Gadde, R., Datema, T., Gatwechi, K., Oskam, L., Katz, Z., et al. (2022). Implementation of a customised antimicrobial resistance laboratory scorecard in Cameroon Ethiopia and Kenya. Afr. J. Lab. Med. 11, 1–9. doi: 10.4102/ajlm.v11i1.1476

Wehking, F., Debrouwere, M., Danner, M., Geiger, F., Buenzen, C., Lewejohann, J. C., et al. (2024). Impact of shared decision making on healthcare in recent literature: a scoping review using a novel taxonomy. J. Public Heal. 32, 2255–2266. doi: 10.1007/s10389-023-01962-w

WHO (2020). The WHO AWaRe (Access, Watch, Reserve) Antibiotic Book. Geneva: World Health Organization, 697.

WHO (2021). Comprehensive Review of the WHO Global Action Plan on Antimicrobial Resistance, Vol. 1 (Geneva), 112.

WHO (2022). Antimicrobial Stewardship Interventions: A Practical Guide, Vol. 14. World Health Organisation, 611–746. Available online at: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/340709/9789289054980-eng.pdf (Accessed August 1, 2025).

Keywords: antimicrobial stewardship (AMS), implementation determinants, complexity science, CFIR framework, health systems, sub-Saharan Africa

Citation: Kapatsa T, Bwanali AN, Kambewa LN, Mkandawire V, Mwale G, Harawa G, Ssebibubbu S, Ali AY, Mudenda S, Masi A, Chumbi G, Moyo C, Makole T, Chung JS, Chung S, Chung D, Chung S, Hwang V, Han C, Lee G, Chitule C, Nyirenda T and Lubanga AF (2025) Assessing the implementation determinants of antimicrobial stewardship programmes in sub-Saharan Africa through the complexity lens. A CFIR-guided systematic review. Front. Microbiol. 16:1660778. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2025.1660778

Received: 07 July 2025; Accepted: 15 October 2025;

Published: 19 November 2025.

Edited by:

Branka Bedenić, University of Zagreb, CroatiaReviewed by:

Reham Khedr, Cairo University, EgyptSuwayda Ahmed, University of the Western Cape, South Africa

Copyright © 2025 Kapatsa, Bwanali, Kambewa, Mkandawire, Mwale, Harawa, Ssebibubbu, Ali, Mudenda, Masi, Chumbi, Moyo, Makole, Chung, Chung, Chung, Chung, Hwang, Han, Lee, Chitule, Nyirenda and Lubanga. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Adriano Focus Lubanga, bHViYW5nYWZvY3VzYWRyaWFubzFAZ21haWwuY29t; YWRyaWFuby5sdWJhbmdhQGNyZWFtc213LmNvbQ==

Thandizo Kapatsa

Thandizo Kapatsa Akim Nelson Bwanali

Akim Nelson Bwanali Leonard Naphazi Kambewa

Leonard Naphazi Kambewa Vitumbiko Mkandawire

Vitumbiko Mkandawire Gillian Mwale

Gillian Mwale Gracian Harawa4

Gracian Harawa4 Stuart Ssebibubbu

Stuart Ssebibubbu Abdisalam Yusuf Ali

Abdisalam Yusuf Ali Steward Mudenda

Steward Mudenda Gertrude Chumbi

Gertrude Chumbi Chitemwa Moyo

Chitemwa Moyo SungJae Chung

SungJae Chung Dowon Chung

Dowon Chung Chloe Han

Chloe Han Adriano Focus Lubanga

Adriano Focus Lubanga