- 1University Medical Center Utrecht, Utrecht, Netherlands

- 2Brain Center Rudolf Magnus, University Medical Center Utrecht, Utrecht, Netherlands

- 3Radboud University Nijmegen Medical Centre, Nijmegen, Netherlands

Objectives: In this systematic review, we aim to evaluate the evidence regarding the correlation between tinnitus distress and the severity of depressive symptoms in patients with chronic tinnitus. Also, the prevalence of clinically relevant depressive symptoms scores in patients with chronic tinnitus was evaluated.

Methods: We performed a systematic review in PubMed, EMBASE, and the Cochrane library in June 2021 using the terms “depression” and “tinnitus,” and their synonyms, following PRISMA guidelines. Studies were selected on relevance and critically appraised regarding risk of bias using the Newcastle–Ottowa Quality Assessment Scale.

Results: A total of 1,912 articles were screened on title and abstract after the removal of the duplicates. Eventually, 33 (1.5%) articles were included for the final analysis. Only cross-sectional cohort studies and case–control studies with a low level of evidence and a high risk of bias due to the study design and patient selection were found. Statistically significant correlations between the experienced tinnitus distress and depressive symptoms were reported in 31 out of 33 studies. Clinically relevant depression scores had a prevalence of 4.6–41.7%.

Conclusions: In this systematic review, in which mostly cross-sectional studies were included, a statistically significant correlation was found between the experienced tinnitus distress and the reported severity of symptoms of depression in patients with chronic tinnitus. A wide range of clinically relevant depression scores were reported in included studies. Due to the high risk of bias of included studies it is not possible to provide a definite answer on the existence of this relationship. Future population-based studies are necessary to provide more clarity.

Introduction

The subjective tinnitus is the perception of a noise or sound without an external acoustic stimulus (1). It is a phenomenon with a reported prevalence between 5.1 and 42.7% (2). The impact chronic tinnitus has on the patients differs widely and is associated with comorbidities such as sleep and/or concentration problems (3). Many patients with tinnitus have some kind of hearing impairment and their hearing status have been found to be correlated to the experienced tinnitus distress in previous studies (4, 5). As tinnitus itself is a symptom, the treatment options depend on the etiology of the underlying disease (6). However, in the majority of patients with tinnitus the underlying cause is unknown and symptom reduction seems to be the highest achievable goal for many patients affected. All in all, tinnitus can be responsible for a reduced quality of life and impaired psychological functioning (7).

The depressive feelings and depression have frequently been reported in patients with chronic tinnitus, with studies dating back till the 1980s (8). In 2019, Salazar et al. (9) published a review of the literature on the prevalence of depression in the adult populations with tinnitus, including patients with both chronic and acute tinnitus. From the 28 studies that were included, the authors distracted a mean prevalence of depression of 33% (range: 6–84%) (9). However, no details were provided about the experienced tinnitus distress, severity or impact on daily life in relation to the depression or depressive symptoms of the studied patients. In addition, several of the included studies did not use clear criteria on which the diagnosis depression was made. This is of importance for the interpretation of outcomes as in clinical practice the diagnosis depression can only be made by a physician and based on the Diagnostical and Statistical Manual of Mental disorders (DSM-V) (10), while depressive symptoms can be measured using a variety of questionnaires; most of which are self-rating questionnaires (11, 12).

In the earlier reports, several hypotheses have been made about the simultaneous finding of these entities. It is hypothesized that the impact of tinnitus on daily life can trigger a depression in depression-prone persons (9, 13, 14). In other studies, it was suggested that tinnitus-related stress can cause alterations in the limbic–cortical pathways of the brain which result in a more depressive state, similar to chronic pain (15–17). Although, so far, it is unknown if the relation between both is causal in one or the other way, or if the co-occurrence of both is related to other entities or variables.

More knowledge about the relationship between the experienced tinnitus distress and the severity of the depressive symptoms or the existence of a clinical depression in patients with chronic tinnitus is of upmost importance. More insight in this relationship would provide essential information for healthcare professionals in tinnitus care. Awareness of depressive symptoms or the existence of a depression could warrant specialized treatment for these patients aimed at relief for these symptoms apart from their tinnitus. Therefore, we aim to systematically asses the correlation between the severity of tinnitus distress and the severity of depressive symptoms. As a secondary objective, we aim to investigate the prevalence of clinically relevant depressive symptoms scores in patients with chronic tinnitus.

Methods

We used the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guideline for this systematic review (18).

Search Strategy

We conducted a systematic search of the literature on 26 June 2021. The electronic databases of PubMed, EMBASE, and the Cochrane Library were searched (Appendix 1). We used search terms and their synonyms of tinnitus and depressive symptoms or depression in title/abstract, medical subject headings (MeSH) terms, and Emtree fields. In addition to electronic database searches, reference lists were scanned to identify additional studies.

Study Selection

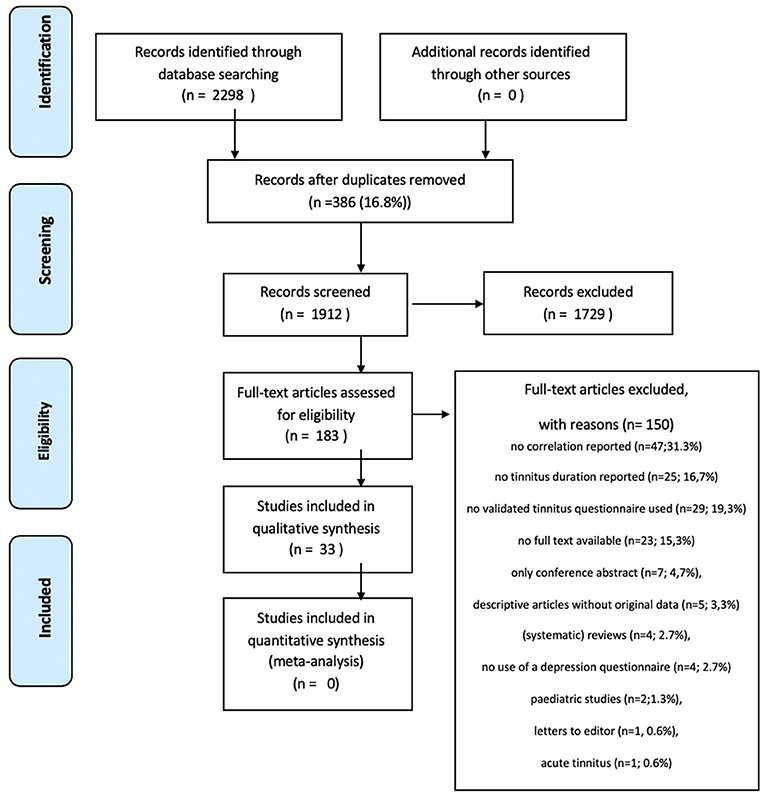

Three authors (SM, RM, and MR) independently scanned the initial search results on title/abstract to identify the studies, which met the predefined inclusion criteria. The retrieved studies were reviewed full text using the predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria (Figure 1). If an article was not available in full text, the author was contacted to request the full text article. Differences in opinion regarding the inclusion of studies were resolved by discussions.

We included the studies that described adults with chronic subjective tinnitus (defined as a minimum duration of 3 months). The randomized controlled trials and (retrospective and prospective) cohort studies reporting on the experienced tinnitus distress and depressive symptoms using validated questionnaires were selected. We excluded the pediatric studies, non-original study designs, animal studies, case reports (n <5), studies on the patients with cochlear implantation(s), studies with the overlapping populations or studies with non-available abstract or full text.

Data Collection and Analysis

Quality Assessment of the Studies

Two authors (SM and MR) independently assessed the risk of bias of the included studies. The Newcastle–Ottawa Quality assessment scale (NOS) was used to assess the representativeness of the exposed cohort, selection of the non-exposed cohort (if present), ascertainment of exposure, demonstration that outcome of interest was not present at start of study (if possible), comparability (if possible), follow-up long enough for outcomes to occur, and adequacy of follow-up of cohorts. Two versions of NOS were used: one version for the cohort studies and one for the case–control studies. Using the NOS tool, the studies were judged to be of poor, fair or good quality (19). The scoring system is described in the legends of Supplementary Tables 1A,B, and they are provided as supplementary files.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

The following data was extracted by one author (SM): (1) The total number of participants in one study and their sex and age; (2) The type of tinnitus questionnaire (TQ) used; (3) The mean score on TQ; (4) The type of depression questionnaire used; (5) The mean score on depression questionnaire; (6) The clinical depression score (when reported); (7) The data about the correlation between tinnitus distress and depressive symptoms; (8) The data about hearing status of included participants. The second author (MR) checked the extracted data. The differences were solved in a consensus meeting.

Outcome Measures

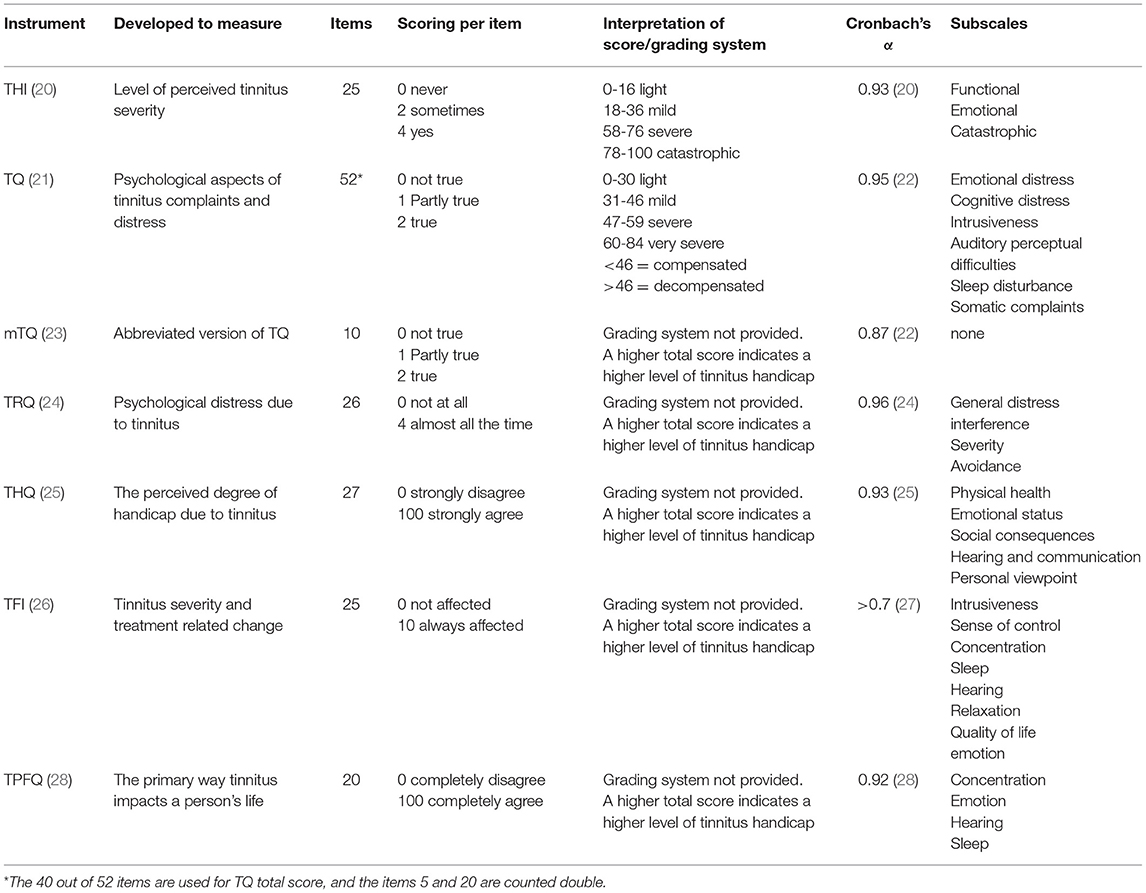

The studies using multi-item validated questionnaires to measure tinnitus distress, severity or impact on daily life were included (Table 1A). These include the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory (THI), the TQ, the mini Tinnitus Questionnaire (mTQ), the Tinnitus Functional index (TFI), the Tinnitus Handicap Questionnaire (THQ), the Tinnitus Primary Function Questionnaire (TPFQ), and the Tinnitus Reaction Questionnaire (TRQ) (20, 21, 23–26, 28).

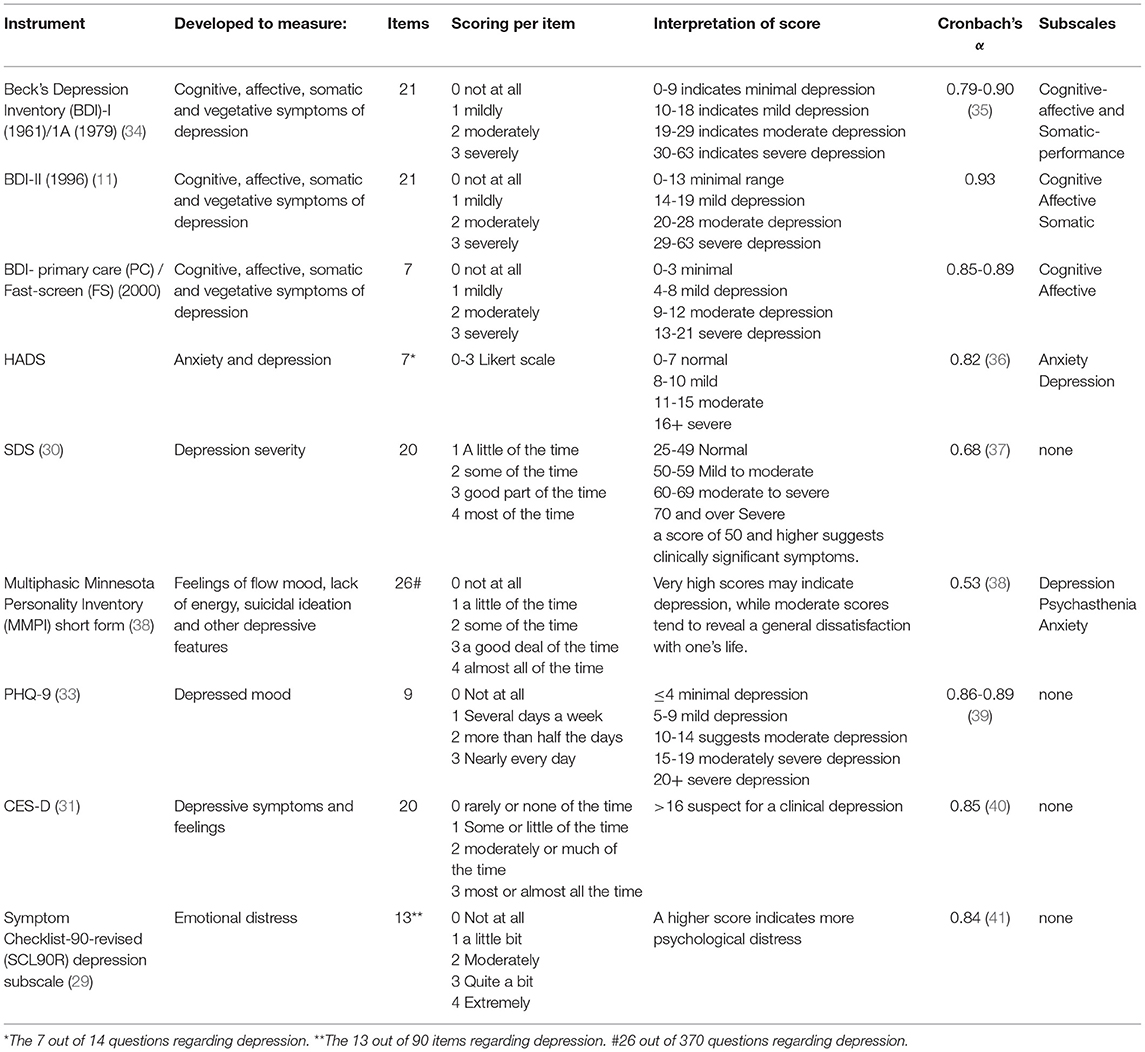

The studies were used in which the outcomes of validated multi-item questionnaires were reported to measure the severity of depressive symptoms. These questionnaires are the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), Symptom Checklist Revised (SCL90-R) subscale depression, self-rating depression scale (SDS), the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Index (MMPI) subscale depression, and the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) (11, 12, 29–33). The definition of having a clinically relevant depressive symptom score was based on the provided cut-off score by the study reporting this outcome. If this definition or criterion was not provided, the cut-off score out of the manual or validation study describing the specific questionnaire was used to define “having a depression” (Table 1B).

Because of the expected heterogeneity of studies in methodology, inclusion criteria of participants, and assessed outcomes, the intentional analysis is a descriptive synthesis of results and not a meta-analysis.

Results

Search Strategy and Study Selection

The electronic search yielded a total of 2,298 articles. After removal of 386 duplicates, 1,912 studies were screened on title and abstract (see Figure 1). The title/abstract screening resulted in 183 studies to read in full text. A total of 150 studies were excluded due to various reasons; no correlation reported between tinnitus distress and depressive symptoms (n = 47); no tinnitus duration reported (n = 25); no validated TQ used (n = 29); no full text available (n = 23); only conference abstract (n = 7); descriptive articles without original data (n = 5); (systematic) reviews (n = 4); no use of a validated depression questionnaire (n = 4); pediatric studies (n = 2); letters to the editor (n = 1) or studies on acute tinnitus (n = 1). Finally, 33 studies (18.0%) were included in this review.

Study Characteristics

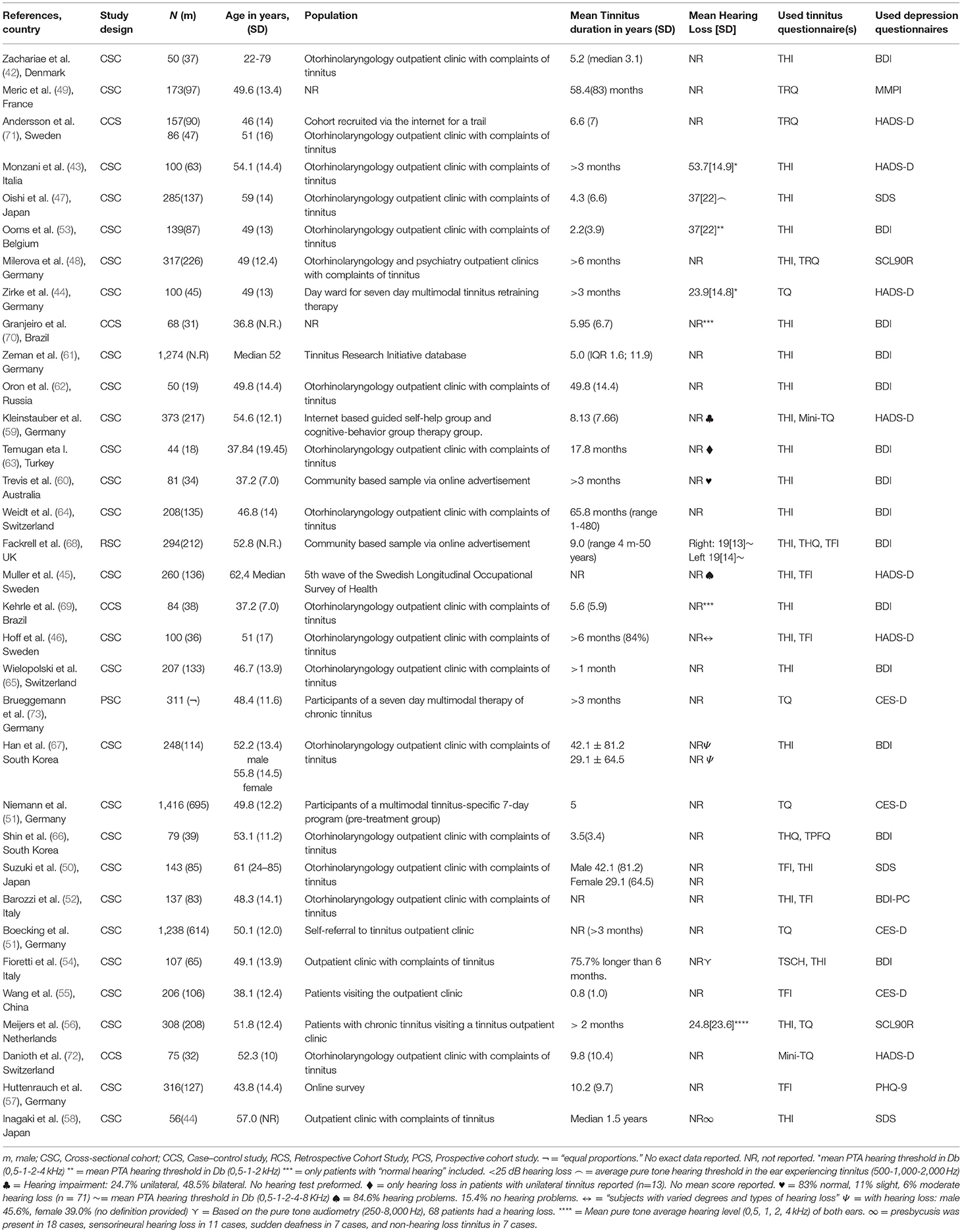

Of the 33 included studies, 27 studies were cross-sectional cohort studies (16, 42–67) as discussed in the following: One was a retrospective cohort study (68), four were case–control studies (69–72), and one was a prospective study (73). The studies were published between 2000 and 2021 and described 8,990 participants (range: 44–1,416 participants per study) (Table 2).

Risk of Bias Assessment

Quality of the Included Studies

The risk of bias assessment of included studies can be found in Supplementary Tables 1A,B. Four case–control studies were found. For these studies, the NOS assessment scale for case–control studies was used (69–72). All other studies were cohort studies for which the NOS assessment scale for cohort studies was used (16, 42–66, 73). Due to the study design the subsection “selection of the exposed cohort” and main sections “outcome,” and “comparability” were not achieved in these cohort studies. Because of the cross-sectional design of all cohort studies “demonstration that outcome of interest was not present at start of study” could not be judged.

Selection of Patients in the Cohort Studies

The representativeness of the exposed cohort was of poor quality in all included studies. In the 29 cohort studies, this was related to the highly selected patient groups included in those studies. The ascertainment of exposure was of good quality in these studies due to the use of the predefined TQs. The representativeness of the exposed cohort in the other four studies [Meric et al. (49), Shin et al. (66), Fioretti et al. (54), and Wang et al. (55)] was also judged to be of poor quality because of other reasons. Meric et al. (49) did not report about where the cohort was recruited from. Shin et al. (66), Fioretti et al. (54), and Wang et al. (55) gave no insight in the used selection procedure of the patients. The ascertainment of exposure was of good quality in all 29 studies due to the use of the predefined TQs.

Comparability of the Patients in the Cohort Studies

Among the cohort studies, only the study of Han et al. (67) compared two groups. Han et al. (67) compared the results of male and female patients with tinnitus. The other studies did not compare different study populations and therefore comparability was judged as not applicable.

Selection of Patients in the Case–Control Studies

The case definition was valid in all four case–control studies (Supplementary Table 1B). In the studies of Kehrle et al. (69), Granjeiro et al. (70), and Danioth et al. (72), the case definition was validated independently based on predefined inclusion criteria. Andersson et al. (71) recruited a cohort of patients with tinnitus from the internet and let them fill out questionnaires regarding their tinnitus distress and depressive symptoms. The representativeness was of low quality in all four case–control studies because of the potential selection bias. The method of selection of the control group was unclear in the studies of Kehrle et al. (69) and Granjeiro et al. (70). In the study of Andersson et al. (71), they recruited a control group from a clinical sample of patients which were seen by a psychologist because of tinnitus to compare to their internet cohort. Danioth recruited a control group using word of mouth advertisement. Only Kerle et al. (69) and Danioth et al. (72) had a control group with no history of tinnitus.

The Comparability and Expose of the Patients in Case–Control Studies

Among the four case–control studies, only Danioth et al. (72) and Kehrle et al. (69) controlled for multiple factors such as sex, age, and hearing thresholds. Granjeiro et al. (70), and Andersson et al. (71) did not provide the data regarding this subject. Exposure was scored of good quality in all studies.

Data Extraction and Study Characteristics

Outcome Measures

The tinnitus distress was assessed by using different multi-item questionnaires as listed as follows: The THI was used in 20 out of 33 studies (42, 52–54, 56, 58, 60–66, 68–70, 74), TFI by seven (45, 46, 50, 52, 55, 57, 68), TQ by five (44, 48, 51, 56, 73), TRQ by two (49, 71), mini-TQ by two (59, 72), and both THQ (66) and TPFQ by one study (66). The depressive symptoms were also assessed by using different multi-item questionnaires. The BDI was used in 15 studies (42, 52–54, 60–63, 65, 66, 68, 69, 74), HADS-D was used by seven studies (43–46, 59, 71, 72), CES-D by four studies (16, 51, 55, 73), SDS by three studies (47, 50, 58), SCL-90R (48, 56). The MMPI and the PHQ-9 were both used once in two different studies (49, 57) (Tables 4–6).

Outcomes

Studies Using BDI

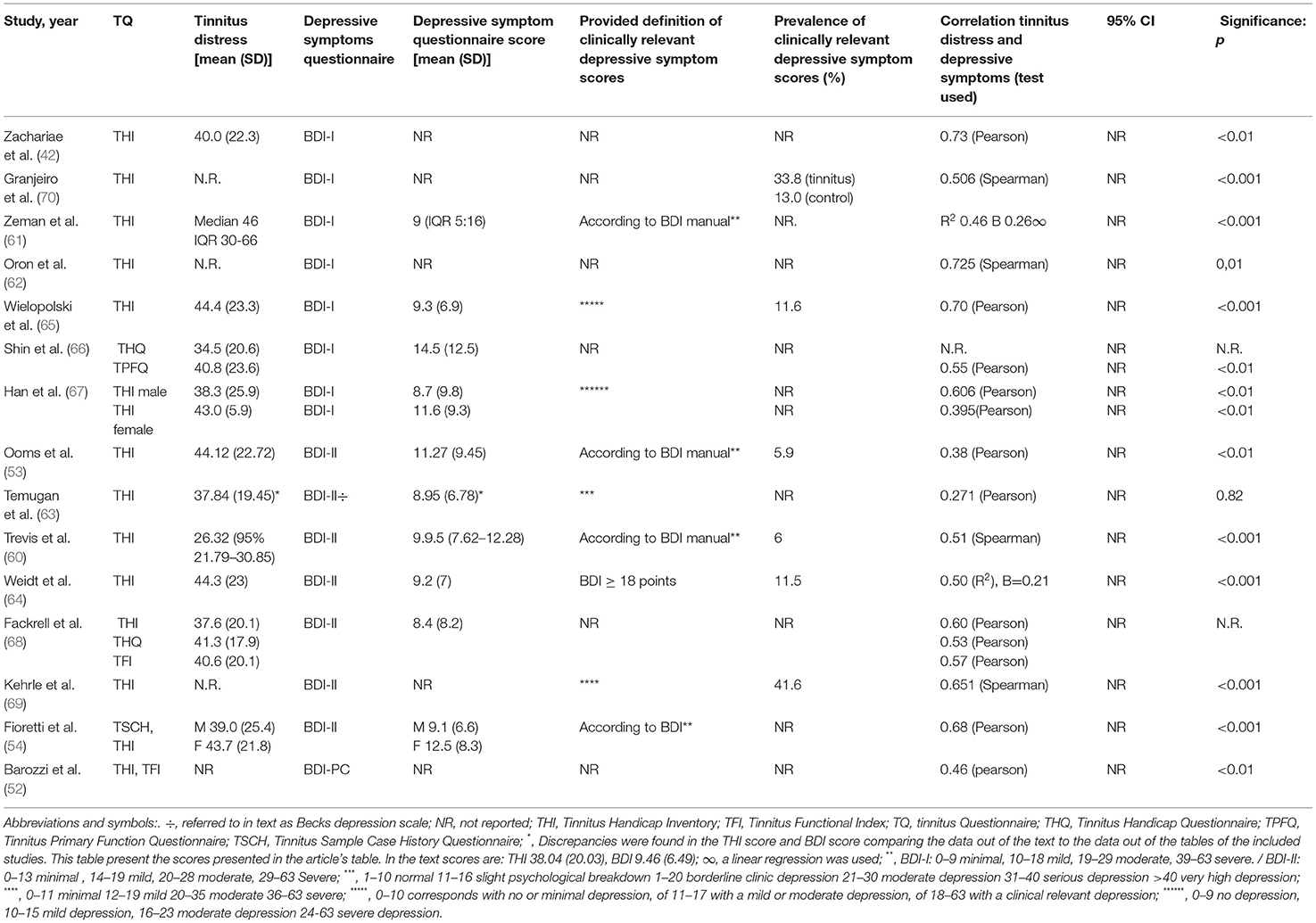

The 15 out of 33 studies (45%) used the BDI to report depression severity (Table 3) (42, 52–54, 60–66, 68–70). Correlations between measures of tinnitus distress and depression severity were calculated using Pearson's test in 9 out of 15 studies (42, 52–54, 63, 65–68), Spearman's tests in four out of 15 studies (60, 62, 69, 70) and univariate regressions analysis in two of 15 studies (61, 64). The 13 out of 15 studies reported a statistical significant positive correlation, which varied between 0.51 and 0.73 in the studies using Spearman correlation and between 0.46 and 0.7 in the studies using Pearson's correlation (Table 3) (42, 52–54, 60–62, 64, 65, 67, 69, 70).

Table 3. Outcomes of studies using BDI to measure depressive symptoms/clinically relevant depressive symptom scores.

All 15 studies except Shin et al. (66) used the THI to measure tinnitus distress. Fackrell et al. (68) described the correlation between BDI and THI; THQ and TFI using a Pearson correlation (THI 0.60, THQ 0.53, TFI 0.57) without reporting an estimate or significance. Shin et al. (66) found a significant correlation using the TPFQ questionnaire [r = 0.55 p < 0.01 using Pearson correlation, confidence interval (CI) which was not reported], and they did not report on the correlation with THQ scores.

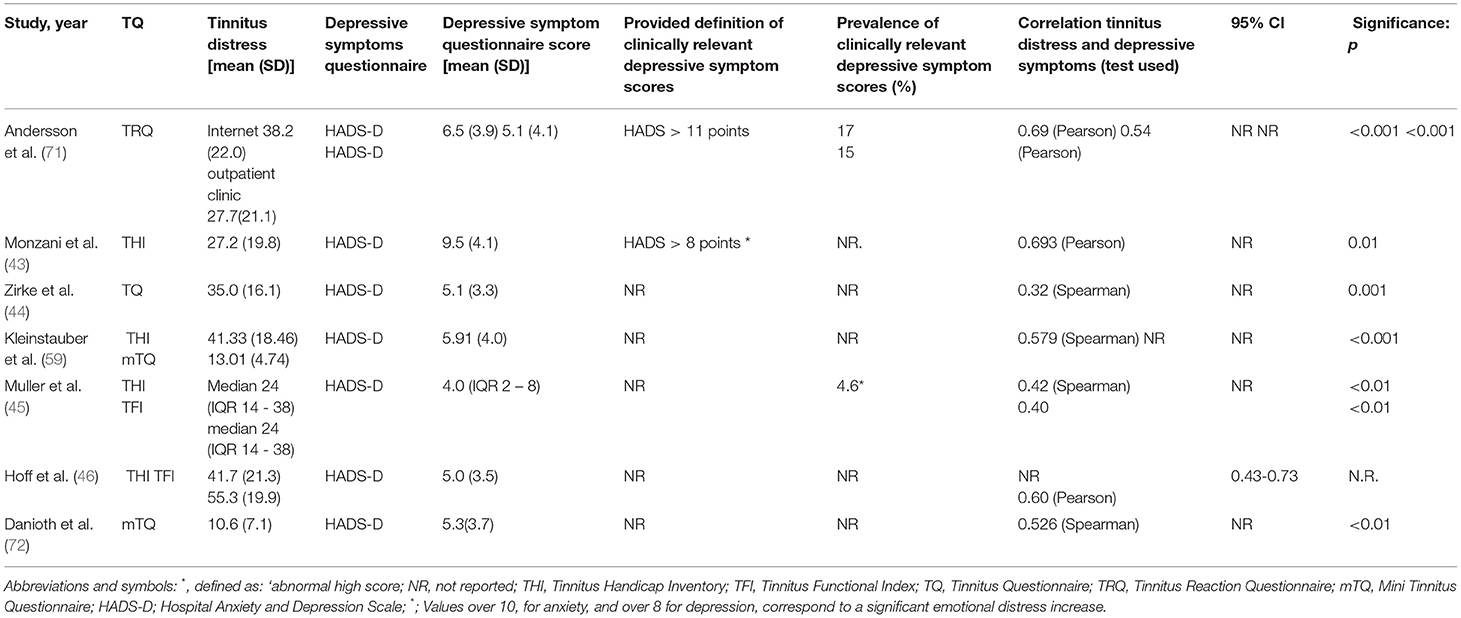

Studies Using Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale

The 7 out of 33 studies (23%) studies used the HADS-D to report depressive symptom severity (43–46, 59, 71, 72) (Table 4). Both Hoff et al. (46) and Andersson et al. (71) found significant positive correlations between tinnitus distress and severity of depression using a Pearson correlation (Hoff: r = 0.6, no p-value reported, CI = 0.43–0.70; Andersson: r = 0.54 p < 0.001 no CI value reported). Monzani et al. (43) also used a Pearson correlation and found a positive significant relation but referred to this as “a significant emotional distress increase” instead of a depression. Four other studies reported significant positive correlations ranging between 0.32–0.526 for studies using Spearman's correlation (44, 45, 59, 71). These correlations were found in studies in which the TQ, TRQ, and/or TFI were used (Zirke: TQ: 0.32, no CI value reported, p < 0.001; Muller: THI: 0.42, no CI value reported, p < 0.01, TFI: 40 no CI value reported, p < 0.01; Kleinstauber: THI 0.579, no CI value reported, p < 0.001).

Table 4. Outcomes of studies using HADS to measure depressive symptoms/clinically relevant depressive symptom scores.

Studies Using Other Scales Than BDI or HADS

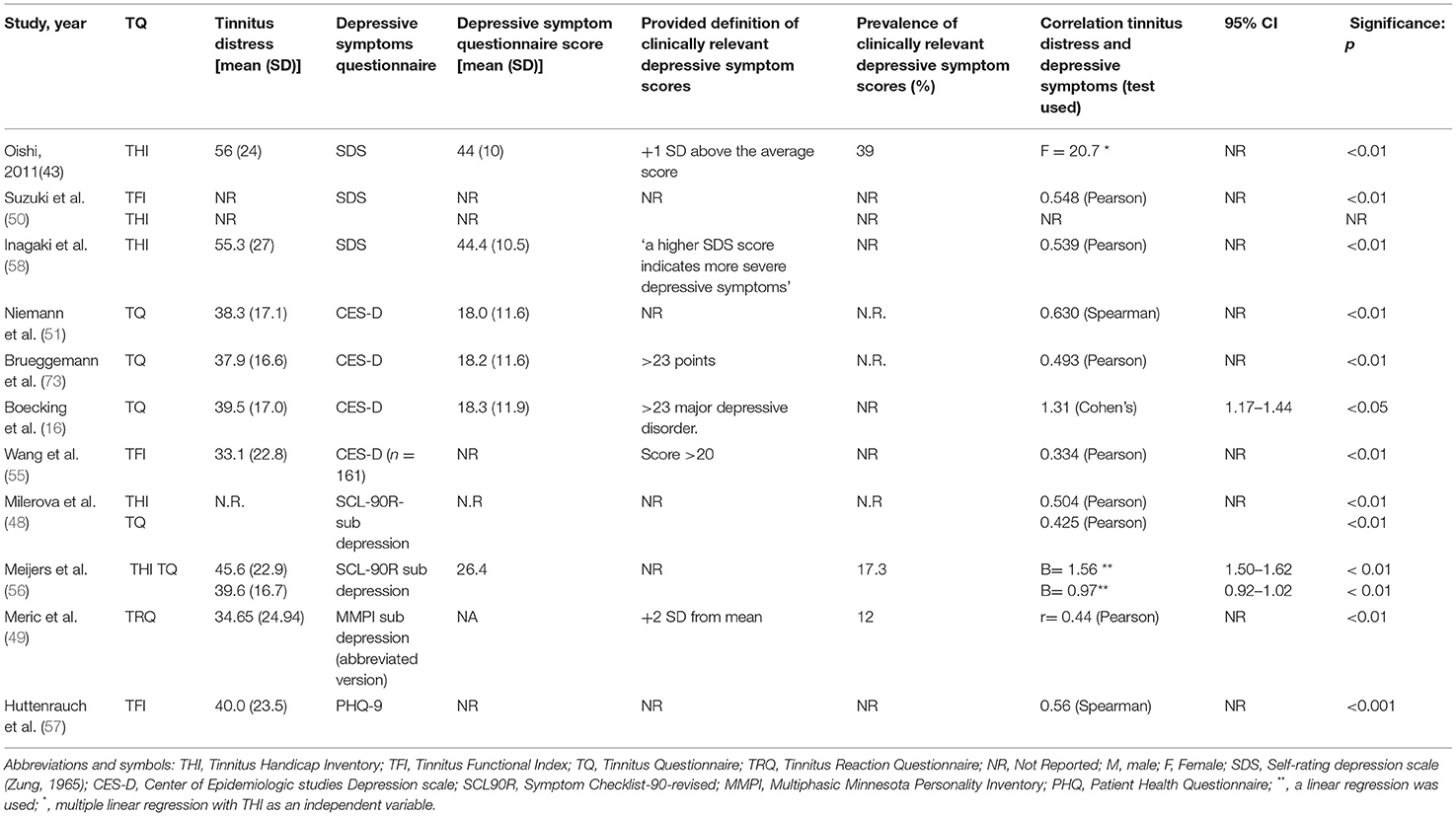

The 11 of 33 studies (33%) used another instrument to measure depressive symptoms rather than BDI or HADS-D (16, 47–51, 55–58, 73) (Table 5).

Table 5. Outcomes of studies using other questionnaires to measure depressive symptoms/clinically relevant depressive symptom scores.

Oishi et al. (47) used the SDS and found a statistical significant positive correlation (F = 20.7, p < 0.01, no CI value reported) with the THI using a multiple linear regression. Suzuki et al. (50) and Inagaki et al. (58) also used the SDS and both found a statistical significant positive correlations with the THI using a Pearson correlation (Suzuki: 0.548, p < 0.01, no CI value reported, Inagaki: 0.539, p > 0.01, no CI value reported).

Milerová et al. (48) and Meijers et al. (56) used the subscale depression of the SCL-90R questionnaire and both found a statistical significant positive correlation with THI and TQ using different statistical tests (Milerova—SCL90-THI: 0.504 (Pearson) p < 0.01, no CI value reported, SCL-TQ: 0.425 (Pearson), p < 0.01, no CI reported; Meijers—SCL90-THI: B = 1.56 (linear regression), p < 0.01. CI = 1.50–1.92, SCL90-TQ: 0.97 (linear regression), p < 0.01, CI = 0.92–1.02).

Meric et al. (49) used the subscale depression of a French adaptation of the MMPI and found a statistical significant positive correlation with the TRQ using a Pearson correlation (0.44, p < 0.01 no CI value reported).

Niemann et al. (51), Brueggemann et al. (73) and Boecking et al. (16) used the CES-D and found statistical significant positive results using the TQ [Niemann: 0.63 (Spearman) p < 0.01, no CI value reported; Brueggeman: 0.493 (Pearson), p < 0.01, no CI value reported; Boecking: 1.31 (Cohen's), CI: 1.17–1.44, p < 0.01]. Wang et al. (55) used the CES-D questionnaire in combination with the TFI and reported a significantly positive score of 0.334 using a Pearson correlation (p < 0.01, no CI value reported).

Data Regarding Prevalence of Clinically Relevant Depressive Symptom Scores

Among the 33 studies, 11 studies reported on the prevalence of clinical relevant depressive symptom scores (45, 47, 49, 53, 56, 60, 64, 65, 69–71). Of these studies, in six studies, this was based on the BDI; in two studies, this was based on HADS outcomes; and in three studies, this was based on other questionnaires. The reported prevalence range varied from 4.6–41.6% in these 11 studies.

Discussion

In this systematic review, we investigated the correlation between the experienced tinnitus distress and the severity of depressive symptoms in patients with chronic tinnitus using validated questionnaires. Also, the prevalence of clinically relevant depressive symptoms or a clinical depression in patients with chronic tinnitus was evaluated. We systematically searched three databases using predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. A total of 33 studies were included with a total of 8,990 patients with chronic tinnitus of which 29 were cohort studies and four case-control studies, all with a high risk of bias. All included studies reported a significant positive correlation between tinnitus distress and the severity of depressive symptoms, mostly with moderate to strong correlations.

Multiple factors could have influenced the results of this review. First, included studies were judged as having a high risk of bias and described highly selected patient groups. This high risk of bias was caused by vague inclusion and exclusion criteria, relatively small patient groups and the use of a cross-sectional study design in all but four studies. In addition, in the majority of the included studies patients were investigated that were recruited in outpatient (tinnitus) clinics or by using online advertisements, which makes these studies more prone for selection bias. Patients selected by the fact that they seek medical help for their tinnitus or react on online advertisements may differ from others with tinnitus and from those who never seek any medical help (75). Furthermore, only 4 out of the 33 included studies reported on the hearing status of the study participants. Hearing loss in itself is associated with a higher risk of depression and also is common in patients with chronic tinnitus (76). Therefore, the lack of information about hearing loss as a confounder of the association between tinnitus and depression is regarded as an important limitation of the outcomes of the current study.

Most of the included studies used either the BDI or HADS-D questionnaire to measure levels of depressive symptoms in patients with chronic tinnitus but only 11 studies reported on the prevalence of clinical relevant depressive symptom scores (45, 47, 49, 56, 60, 64, 65, 69–71, 74). The cut-off scores of a “significant” depression were not defined uniformly in the selected studies. For example, in the 15 studies who used the BDI, only 4 studies referred to the original BDI manual for interpretation of the score (53, 54, 60, 61). Some studies provided different interpretations of scores using the same measure (63, 65, 67, 69) and most studies did not provide a definition at all of a cut-off for a clinical relevant depressive symptom scores (42, 52, 62, 66, 68, 69). The wide variety of questionnaires, definitions and cut-off values used to measure and define (symptoms of) depression could all contribute to the wide range of reported prevalence numbers of clinically relevant depressive symptom scores (4.6–41.7%).

When the mean depression scores of the included studies are interpreted based on the questionnaire specific scoring system, the overall minimal-to-mild BDI depression scores were found. In addition, the reported mean HADS-D scores of the included studies should be interpreted as “normal” and mean CES-D scores were far below the definition of a clinical depression/severe depressive symptoms. This could indicate that even if there is a statistically significant positive correlation between tinnitus distress and severity of depressive symptoms, a clinical symptomatic depression was relatively rare in studied patients with chronic tinnitus. This is of special interest as most studies were describing participants recruited in outpatient clinics or by using online advertisements of which it is more likely that participants were having a high tinnitus impact and/or in need for medical help.

The questionnaire design itself could also have influenced the results. Ooms et al. (53) reported about overlap in the content of frequently used depressive symptom questionnaires and TQs. When comparing THI to the BDI questionnaire, the similarities in the content of 15 out of the 25 questions of the THI with 13 out of 21 questions of the BDI were found. This was partly explained by the similarities between the symptoms mentioned by patients with tinnitus or with a depression (e.g., insomnia, concentration difficulties, annoyance, and fear) (77). The THI, SCL90-R, and HADS-D also demonstrated an overlap in questions, but in lesser effect. This is potentially caused by the design of HADS-D, were questions of somatic symptoms are excluded from the questionnaire (36). Beside this, also the differences in TQ design itself could have influenced the results. Because different TQs are designed to measure different aspects of tinnitus, their exposure to psychological facets of tinnitus differs. For example, the TRQ consists for 77% out of questionnaires which investigate the psychological/emotional effects of tinnitus, whereas the THQ only does so for 44% (78). Possibly, this results in stronger correlations between tinnitus and depression in more psychological aimed questionnaires. This could be an important factor to explain the findings of our study with overall significant positive correlations found between tinnitus distress and the severity of depressive symptoms. This raises questions about the validity to distinguish symptoms of both entities. On the other hand, this also underlines the close relationship between both disorders and warrants a multidisciplinary diagnostic and therapeutically approach to treat individuals based on their needs.

Conclusions

All of the included studies found statistically significant correlations between the experienced tinnitus distress and the severity of depressive symptoms in patients with chronic tinnitus. The reported prevalence of having a clinically relevant depressive symptom scores varied from 4.6–41.6% in included studies, but mean depression scores were low in all studies. This contrast, in combination with the quality of studies and risk of bias makes it impossible to conclude about the stated relationship based on current evidence. Besides this, the heterogeneity in used tinnitus and depression symptoms scores and the overlap between the content of these questionnaires hinders drawing conclusions. To answer this question, the future population-based studies with updated methodology will be necessary.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author Contributions

SM, RM, and MR contributed to articles screening. SM, MR, AS, and IS were involved in critical appraisal. All authors revised the manuscript and contributed to the interpretation of the results and approved the final version of this study.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fneur.2022.870433/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Heller AJ. Classification and epidemiology of tinnitus. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. (2003) 36:239–48. doi: 10.1016/S0030-6665(02)00160-3

2. McFerran DJ, Stockdale D, Holme R, Large CH, Baguley DM. Why is there no cure for tinnitus? Front Neurosci. (2019) 13:802. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2019.00802

3. Gu H, Kong W, Yin H, Zheng Y. Prevalence of sleep impairment in patients with tinnitus: a systematic review and single-arm meta-analysis. Eur Arch otorhinolaryngol. (2021) 279:2211-21. doi: 10.1007/s00405-021-07092-x

4. Oosterloo BC, Croll PH, Baatenburg de Jong RJ, Ikram MK, Goedegebure A. Prevalence of tinnitus in an aging population and its relation to age and hearing loss. Otolaryngol neck Surg. (2021) 164:859–68. doi: 10.1177/0194599820957296

5. Waechter S. Association between hearing status and tinnitus distress. Acta Otolaryngol. (2021) 141:381–5. doi: 10.1080/00016489.2021.1876919

6. Han BI, Lee HW, Ryu S, Kim JS. Tinnitus update. J Clin Neurol. (2021) 17:1–10. doi: 10.3988/jcn.2021.17.1.1

7. Trevis KJ, McLachlan NM, Wilson SJ. A systematic review and meta-analysis of psychological functioning in chronic tinnitus. Clin Psychol Rev. (2018) 60:62–86. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2017.12.006

8. Sullivan MD, Katon W, Dobie R, Sakai C, Russo J, Harrop-Griffiths J. Disabling tinnitus. Association with affective disorder. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. (1988) 10:285–91. doi: 10.1016/0163-8343(88)90037-0

9. Salazar JW, Meisel K, Smith ER, Quiggle A, McCoy DB, Amans MR. Depression in patients with tinnitus: a systematic review. Otolaryngol neck Surg. (2019) 161:28–35. doi: 10.1177/0194599819835178

10. Asken MJ, Grossman D, Christensen LW. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Pub-lishing (2013).

11. Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory-II. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation (1996). doi: 10.1037/t00742-000

12. Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. (1983) 67:361–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x

13. Dobie RA. Depression and tinnitus. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. (2003) 36:383–8. doi: 10.1016/S0030-6665(02)00168-8

14. Folmer RL, Griest SE, Meikle MB, Martin WH. Tinnitus severity, loudness, and depression. Otolaryngol neck Surg. (1999) 121:48–51. doi: 10.1016/S0194-5998(99)70123-3

15. Joos K, Vanneste S, De Ridder D. Disentangling depression and distress networks in the tinnitus brain. PLoS ONE. (2012) 7:e40544. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040544

16. Boecking B, von Sass J, Sieveking A, Schaefer C, Brueggemann P, Rose M, et al. Tinnitus-related distress and pain perceptions in patients with chronic tinnitus - do psychological factors constitute a link? PLoS ONE. (2020) 15:e0234807. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0234807

17. Vanneste S, Plazier M, der Loo E van, de Heyning P Van, Congedo M, De Ridder D. The neural correlates of tinnitus-related distress. Neuroimage. (2010) 52:470–80. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.04.029

18. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. (2009) 6:e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

19. Wells GA, Shea B, O'Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, et al. The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality if nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Available online at: http://www.ohrica/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxfordasp. 2009.

20. Newman CW, Jacobson GP, Spitzer JB. Development of the tinnitus handicap inventory. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. (1996) 122:143–8. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1996.01890140029007

21. Goebel G, Hiller W. The tinnitus questionnaire. A standard instrument for grading the degree of tinnitus. Results of a multicenter study with the tinnitus questionnaire. HNO. (1994) 42:166–72.

22. Zeman F, Koller M, Schecklmann M, Langguth B, Landgrebe M. Tinnitus assessment by means of standardized self-report questionnaires: psychometric properties of the Tinnitus Questionnaire (TQ), the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory (THI), and their short versions in an international and multi-lingual sample. Health Qual Life Outcomes. (2012) 10:128. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-10-128

23. Hiller W, Goebel G. Rapid assessment of tinnitus-related psychological distress using the Mini-TQ. Int J Audiol. (2004) 43:600–4. doi: 10.1080/14992020400050077

24. Wilson PH, Henry J, Bowen M, Haralambous G. Tinnitus reaction questionnaire: psychometric properties of a measure of distress associated with tinnitus. J Speech Hear Res. (1991) 34:197–201. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3401.197

25. Kuk FK, Tyler RS, Russell D, Jordan H. The psychometric properties of a tinnitus handicap questionnaire. Ear Hear. (1990) 11:434–45. doi: 10.1097/00003446-199012000-00005

26. Meikle MB, Henry JA, Griest SE, Stewart BJ, Abrams HB, McArdle R, et al. The tinnitus functional index: development of a new clinical measure for chronic, intrusive tinnitus. Ear Hear. (2012) 33:153–76. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0b013e31822f67c0

27. Chandra N, Chang K, Lee A, Shekhawat GS, Searchfield GD. Psychometric validity, reliability, and responsiveness of the tinnitus functional index. J Am Acad Audiol. (2018) 29:609–25. doi: 10.3766/jaaa.16171

28. Tyler R, Ji H, Perreau A, Witt S, Noble W, Coelho C. Development and validation of the tinnitus primary function questionnaire. Am J Audiol. (2014) 23:260–72. doi: 10.1044/2014_AJA-13-0014

29. Derogatis LR, Unger R. (2010). Symptom checklist-90-revised. In Weiner IB, Craighead WE, editors. The Corsini Encyclopedia of Psychology. 4th edn. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. doi: 10.1002/9780470479216.corpsy0970

30. Zung WW. A self-rating depression scale. Arch Gen Psychiatry. (1965) 12:63–70. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1965.01720310065008

31. Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. (1977) 1:385–401. doi: 10.1177/014662167700100306

32. Hathaway SR, Mckinley JC. A Multiphasic personality schedule (Minnesota) : I. Construction of the schedule. J Psychol. (1940) 10:249–54. doi: 10.1080/00223980.1940.9917000

33. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. (2001) 16:606–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x

34. Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. (1961) 4:561–71. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004

35. Beck AT, Steer RA, Carbin MG. Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory: twenty-five years of evaluation. Clin Psychol Rev. (1988) 8:77–100. doi: 10.1016/0272-7358(88)90050-5

36. Bjelland I, Dahl AA, Haug TT, Neckelmann D. The validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. An updated literature review. J Psychosom Res. (2002) 52:69–77. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(01)00296-3

37. Dunstan DA, Scott N, Todd AK. Screening for anxiety and depression: reassessing the utility of the Zung scales. BMC Psychiatry. (2017) 17:329. doi: 10.1186/s12888-017-1489-6

38. McGrath RE, Terranova R, Pogge DL, Kravic C. Development of a short form for the MMPI-2 based on scale elevation congruence. Assessment. (2003) 10:13–28. doi: 10.1177/1073191102250333

39. Gilbody S, Richards D, Brealey S, Hewitt C. Screening for depression in medical settings with the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ): a diagnostic meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med. (2007) 22:1596–602. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0333-y

40. Smarr KL, Keefer AL. Measures of depression and depressive symptoms: Beck depression inventory-II (BDI-II), Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS), Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), and Patient Health Questionn. Arthritis Care Res. (2011) 63(Suppl 1):S454-66. doi: 10.1002/acr.20556

41. Sereda Y, Dembitskyi S. Validity assessment of the symptom checklist SCL-90-R and shortened versions for the general population in Ukraine. BMC Psychiatry. (2016) 16:300. doi: 10.1186/s12888-016-1014-3

42. Zachariae R, Mirz F, Johansen L V, Andersen SE, Bjerring P, Pedersen CB. Reliability and validity of a Danish adaptation of the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory. Scand Audiol. (2000) 29:37–43. doi: 10.1080/010503900424589

43. Monzani D, Genovese E, Marrara A, Gherpelli C, Pingani L, Forghieri M, et al. Validity of the Italian adaptation of the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory; focus on quality of life and psychological distress in tinnitus-sufferers. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. (2008) 28:126–34.

44. Zirke N, Seydel C, Arsoy D, Klapp BF, Haupt H, Szczepek AJ, et al. Analysis of mental disorders in tinnitus patients performed with Composite International Diagnostic Interview. Qual life Res. (2013) 22:2095–104. doi: 10.1007/s11136-012-0338-9

45. Müller K, Edvall NK, Idrizbegovic E, Huhn R, Cima R, Persson V, et al. Validation of online versions of tinnitus questionnaires translated into Swedish. Front Aging Neurosci. (2016) 8:272. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2016.00272

46. Hoff M, Kähäri K. A Swedish cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the Tinnitus Functional Index. Int J Audiol. (2017) 56:277–85. doi: 10.1080/14992027.2016.1265154

47. Oishi N, Shinden S, Kanzaki S, Saito H, Inoue Y, Ogawa K. Influence of depressive symptoms, state anxiety, and pure-tone thresholds on the tinnitus handicap inventory in Japan. Int J Audiol. (2011) 50:491–5. doi: 10.3109/14992027.2011.560904

48. Milerová J, Anders M, Dvorák T, Sand PG, Königer S, Langguth B. The influence of psychological factors on tinnitus severity. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. (2013) 35:412–6. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2013.02.008

49. Meric C, Pham E, Chéry-Croze S. Validation assessment of a French version of the tinnitus reaction questionnaire: a comparison between data from English and French versions. J Speech Lang Hear Res. (2000) 43:184–90. doi: 10.1044/jslhr.4301.184

50. Suzuki N, Oishi N, Ogawa K. Validation of the Japanese version of the tinnitus functional index (TFI). Int J Audiol. (2019) 58:167–73. doi: 10.1080/14992027.2018.1534279

51. Niemann U, Boecking B, Brueggemann P, Mebus W, Mazurek B, Spiliopoulou M. Tinnitus-related distress after multimodal treatment can be characterized using a key subset of baseline variables. PLoS ONE. (2020) 15:e0228037. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0228037

52. Barozzi S, Del Bo L, Passoni S, Ginocchio D, Negri L, Crocetti A, et al. Psychometric properties of the Italian Tinnitus Functional Index (TFI). Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. (2020) 40:230–7. doi: 10.14639/0392-100X-2432

53. Ooms E, Meganck R, Vanheule S, Vinck B, Watelet J-B, Dhooge I. Tinnitus severity and the relation to depressive symptoms: a critical study. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. (2011) 145:276–81. doi: 10.1177/0194599811403381

54. Fioretti A, Natalini E, Riedl D, Moschen R, Eibenstein A. Gender comparison of psychological comorbidities in tinnitus patients - results of a cross-sectional Study. Front Neurosci. (2020) 14:704. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2020.00704

55. Wang X, Zeng R, Zhuang H, Sun Q, Yang Z, Sun C, et al. Chinese validation and clinical application of the tinnitus functional index. Health Qual Life Outcomes. (2020) 18:272. doi: 10.1186/s12955-020-01514-w

56. Meijers SM, Lieftink AF, Stegeman I, Smit AL. Coping in chronic tinnitus patients. Front Neurol. (2020) 11:570989. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2020.570989

57. Hüttenrauch E, Jensen M, Ivanšić D, Dobel C, Weise C. Improving the assessment of functional impairment in tinnitus sufferers: validation of the German version of the Tinnitus Functional Index using a confirmatory factor analysis. Int J Audiol. (2021) 61:1–8. doi: 10.1080/14992027.2021.1919766

58. Inagaki Y, Suzuki N, Oishi N, Goto F, Shinden S, Ogawa K. Personality and sleep evaluation of patients with Tinnitus in Japan. Psychiatr Q. (2021) 92:249–57. doi: 10.1007/s11126-020-09794-7

59. Kleinstäuber M, Frank I, Weise C. A confirmatory factor analytic validation of the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory. J Psychosom Res. (2015) 78:277–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2014.12.001

60. Trevis KJ, McLachlan NM, Wilson SJ. Psychological mediators of chronic tinnitus: the critical role of depression. J Affect Disord. (2016) 204:234–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.06.055

61. Zeman F, Koller M, Langguth B, Landgrebe M. Which tinnitus-related aspects are relevant for quality of life and depression: results from a large international multicentre sample. Health Qual Life Outcomes. (2014) 12:7. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-12-7

62. Oron Y, Sergeeva NV, Kazlak M, Barbalat I, Spevak S, Lopatin AS, et al. A Russian adaptation of the tinnitus handicap inventory. Int J Audiol. (2015) 54:485–9. doi: 10.3109/14992027.2014.996823

63. Temugan E, Yildirim RB, Onat H, Susuz M, Elden C, Unsal S, et al. Does Tinnitus lead to depression? Clin Invest Med. (2016) 39:27505. doi: 10.25011/cim.v39i6.27505

64. Weidt S, Delsignore A, Meyer M, Rufer M, Peter N, Drabe N, et al. Which tinnitus-related characteristics affect current health-related quality of life and depression? A cross-sectional cohort study. Psychiatry Res. (2016) 237:114–21. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.01.065

65. Wielopolski J, Kleinjung T, Koch M, Peter N, Meyer M, Rufer M, et al. Alexithymia is associated with tinnitus severity. Front Psychiatry. (2017) 8:223. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2017.00223

66. Shin J, Heo S, Lee H-K, Tyler R, Jin I-K. Reliability and validity of a Korean version of the Tinnitus primary function questionnaire. Am J Audiol. (2019) 28:362–8. doi: 10.1044/2018_AJA-18-0131

67. Han TS, Jeong J-E, Park S-N, Kim JJ. Gender differences affecting psychiatric distress and tinnitus severity. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. (2019) 17:113–20. doi: 10.9758/cpn.2019.17.1.113

68. Fackrell K, Hall DA, Barry JG, Hoare DJ. Psychometric properties of the Tinnitus Functional Index (TFI): assessment in a UK research volunteer population. Hear Res. (2016) 335:220–35. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2015.09.009

69. Kehrle HM, Sampaio ALL, Granjeiro RC, de Oliveira TS, Oliveira CACP. Tinnitus annoyance in normal-hearing individuals: correlation with depression and anxiety. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. (2016) 125:185–94. doi: 10.1177/0003489415606445

70. Granjeiro RC, Kehrle HM, de Oliveira TSC, Sampaio ALL, de Oliveira CACP. Is the degree of discomfort caused by tinnitus in normal-hearing individuals correlated with psychiatric disorders? Otolaryngol neck Surg. (2013) 148:658–63. doi: 10.1177/0194599812473554

71. Andersson G, Kaldo-Sandström V, Ström L, Strömgren T. Internet administration of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale in a sample of tinnitus patients. J Psychosom Res. (2003) 55:259–62. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(02)00575-5

72. Danioth L, Brotschi G, Croy I, Friedrich H, Caversaccio M-D, Negoias S. Multisensory environmental sensitivity in patients with chronic tinnitus. J Psychosom Res. (2020) 135:110155. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2020.110155

73. Brueggemann P, Seydel C, Schaefer C, Szczepek AJ, Amarjargal N, Boecking B, et al. ICD-10 Symptom Rating questionnaire for assessment of psychological comorbidities in patients with chronic tinnitus. HNO. (2019) 67(Suppl 2):46–50. doi: 10.1007/s00106-019-0625-7

74. Figueiredo RR, Rates MA, Azevedo AA de, Oliveira PM de, Navarro PBA de. Correlation analysis of hearing thresholds, validated questionnaires and psychoacoustic measurements in tinnitus patients. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. (2010) 76:522–6.

75. Scott B, Lindberg P. Psychological profile and somatic complaints between help-seeking and non-help-seeking tinnitus subjects. Psychosomatics. (2000) 41:347–52. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.41.4.347

76. Lawrence BJ, Jayakody DMP, Bennett RJ, Eikelboom RH, Gasson N, Friedland PL. Hearing loss and depression in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gerontologist. (2020) 60:e137–54. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnz009

77. Langguth B, Landgrebe M, Kleinjung T, Sand GP, Hajak G. Tinnitus and depression. World J Biol Psychiatry. (2011) 12:489–500. doi: 10.3109/15622975.2011.575178

Keywords: tinnitus, burden, depression, depressive symptoms, impact

Citation: Meijers SM, Rademaker M, Meijers RL, Stegeman I and Smit AL (2022) Correlation Between Chronic Tinnitus Distress and Symptoms of Depression: A Systematic Review. Front. Neurol. 13:870433. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2022.870433

Received: 06 February 2022; Accepted: 30 March 2022;

Published: 02 May 2022.

Edited by:

Agnieszka J. Szczepek, Charité Universitätsmedizin Berlin, GermanyReviewed by:

Alessandra Fioretti, Tinnitus Center, European Hospital, ItalyPedro L. Mangabeira-Albernaz, Hospital Israelita Albert Einstein, Brazil

Sebastian Waechter, Lund University, Sweden

Copyright © 2022 Meijers, Rademaker, Meijers, Stegeman and Smit. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Adriana L. Smit, YS5sLnNtaXQtOUB1bWN1dHJlY2h0Lm5s

Sebastiaan M. Meijers

Sebastiaan M. Meijers Maaike Rademaker

Maaike Rademaker Rutger L. Meijers3

Rutger L. Meijers3 Inge Stegeman

Inge Stegeman Adriana L. Smit

Adriana L. Smit