Abstract

Background:

Stroke disrupts the functions carried out by the brain such as the control of movement, sensation, and cognition. Disruption of movement control results in hemiparesis that affects the function of the diaphragm. Impaired function of the diaphragm can in turn affect many outcomes such as respiratory, cognitive, and motor function. The aim of this study is to carry out a systematic review and meta-analysis to determine the efficacy of diaphragmatic breathing exercise on respiratory, cognitive, and motor outcomes after stroke.

Method:

The study was registered in PROSPERO (CRD42023422293). PubMED, Embase, Web of Science (WoS), PEDro, Scopus, and CENTRAL databases were searched until September 2023. Only randomized controlled trials comparing diaphragmatic breathing exercise with a control were included. Information on the study authors, time since stroke, mean age, height, weight, sex, and the protocols of the experimental and control interventions including intensity, mean scores on the outcomes such as respiratory, cognitive, and motor functions were extracted. Cochrane risks of bias assessment tool and PEDro scale were used to assess the risks of bias and methodological quality of the studies. Narrative synthesis and meta-analysis were used to summarize the results, which were then presented in tables, risk-of-bias graph, and forest plots. The meta-analysis was carried out on respiratory function [forced vital capacity (FVC), forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1), FEV1/FVC, peak expiratory flow (PEF)] and motor function (trunk impairment, and internal and external oblique muscles activity).

Results:

Six studies consisting of 151 participants were included. The results of the meta-analyses showed that diaphragmatic breathing exercise is only superior to the control at improving respiratory function, FVC (MD = 0.90, 95% CI = 0.76 to 1.04, P < 0.00001), FEV1 (MD = 0.32, 95% CI = 0.11 to 0.52, P = 0.002), and PEF (MD = 1.48, 95% CI = 1.15 to 1.81, P < 0.00001).

Conclusion:

There is limited evidence suggesting that diaphragmatic breathing exercise may help enhance respiratory function, which may help enhance recovery of function post stroke.

Systematic Review Registration:

PROSPERO, identifier CRD42023422293.

Introduction

Stroke disrupts movement, sensation, and cognition functions that are normally carried out by the brain (1–3). One of the movement functions controlled by the brain is that of the trunk muscles, which gets impaired after stroke as a result of hemiparesis (4–7). The trunk muscles, especially the diaphragm, contribute to respiration by moving the chest up and down (8). However, following a stroke, it was noted that approximately 52% of the patients developed dysfunction of the diaphragm, such as reduced diaphragmatic excursion, that eventually resulted in respiratory compromise (4, 9). Consequently, compared with the healthy control, stroke survivors have lower values of forced vital capacity (FVC), forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1), peak expiratory flow (PEF), and diaphragmatic excursion (10).

Diaphragmatic excursion, movement of the diaphragm during breathing, directly and indirectly influences the parasympathetic and sympathetic nervous systems, consequently impacting the activities of the motor nerves (11, 12). This is because the diaphragm is supplied by the phrenic nerve, which is closely connected with the vagus nerve, the longest nerve in the body that controls many functions in the body (12). Thus, diaphragmatic breathing exercise, which is a type of breathing exercise that involves slow, smooth, and deep inspiration through the nose, accompanied by the displacement of the abdomen together with the diaphragm can be used to improve respiratory and other functions after stroke (13–16). It is usually carried out in supine position (sometimes with trunk inclination of approximately 30 degrees to help enhance the action of the diaphragm) with one hand placed on the chest to allow for only a minimal movement of the chest and the other hand on the belly (17, 18).

The main effects of diaphragmatic breathing exercise include increased tidal volume and oxygen saturation, reduction in breathing frequency, and improvement in ventilation and hematosis (19, 20). Normalization of breathing results in delivery of adequate oxygen to body tissues for many metabolic activities (21, 22). Consequently, it has been used to improve stress, attention, negative affect, FVC, FEV1, PEF, and head posture in both health and disease (23, 24). Thus, diaphragmatic breathing exercise seems to play role in improving respiratory, cognitive, and motor functions in patients with stroke. Improvement in respiratory, cognitive, and motor functions after stroke are related to the patients' ability to carry out activities of daily living (ADL), participate in activities, and to achieve increased quality of life (25–30). The aim of this systematic review and meta-analysis is to determine the evidence from the literature on the efficacy of diaphragmatic breathing exercise on respiratory, cognitive, and motor outcomes after stroke.

Materials and methods

This study is a systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature on the efficacy of diaphragmatic breathing exercise on outcomes after stroke. The review was conducted following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. For transparency in the process of conducting the review, it was registered in PROSPERO. The registration number is CRD42023422293.

Criteria for inclusion of studies in the review

The inclusion criteria used in the study is based on participants (patients with stroke who are 18 years or older), intervention (diaphragmatic breathing exercise), comparator (a control intervention such as usual care or any other intervention other than diaphragmatic breathing exercise), and outcomes (respiratory, cognitive, and motor functions). Studies were only included if they are randomized controlled trials (RCTs). However, studies that were published in languages other than English were excluded from the review.

Searching the literature

The search was carried out in PubMED, Embase, Web of Science (WoS), PEDro, Scopus, and CENTRAL from the inception of each database until September 2023. The search terms used are stroke, breathing exercises forced vital capacity, maximal expiratory pressure, maximal cognitive function, and motor activity. Each search was adapted to the specific requirement of the databases. The search strategy used is provided in the Appendix.

In addition, a manual search of the reference lists of the included studies and relevant systematic reviews was carried out. The search was performed by AA but was independently confirmed by TWLW.

Study selection

Eligible studies were independently selected using Endnote software by AA and TWLW. Initially, the selection was carried out based on titles and abstracts of the studies. In that case, studies that were deemed ineligible were immediately excluded. Subsequently, the full texts of the remaining studies were read to determine their eligibility. Following this, AA and TWLW held a meeting to agree on their independent selections of the studies. However, when they were unable to agree on the selection of a particular study, SSMN was contacted to help resolve the disagreement.

Data extraction

Information on the study authors, time since stroke, mean age, height, weight, sex, and the protocols of the experimental and control interventions including the intensity (how many minutes or hours per day, how many times a week, and for how many weeks the breathing exercise was carried out), mean scores on the outcomes of interest such as respiratory function [FVC, FEV1, FEV1/FVC, PEF, oxygen saturation (SPO2), maximal inspiratory pressure (MIP), and maximal expiratory pressure (MEP)], cognitive function, and motor function (muscle activation or activity and trunk impairment), chest circumference, and abdominal muscle thickness and balance were extracted by AA. However, TWLW and SSMN independently verified the extracted data for quality assurance. The extracted data were stored in a Microsoft Excel file.

Risks of bias and methodological quality assessments

The Cochrane Risk of Bias Assessment tool was used to assess the risks of bias of the included studies. It is a valid and reliable instrument that assesses selection, performance, detection, attrition, and reporting biases in addition to any other action deemed as a bias in the conduct of a study (31).

For the methodological quality assessment, a tool known as PEDro scale that consists of 11 items was used (32). The first item of the tool assesses internal validity, whereas the remaining 10 items assess external validity, which are rated on a two-point scale, 0 (when the answer to an item is no) and 1 (when the answer to an item is yes) (32). The total scores obtained from the scale can be designated as low, moderate, or high quality when it is between 0 and 3, 4 and 5, or 6 and 10, respectively (33–35).

Both the assessments of the risks of bias and methodological quality were carried out by AA and TWLW independently. Following that, they met to agree on their assessments. However, SSMN was involved when they could not agree on a particular assessment.

Synthesis of the extracted data

The extracted data were synthesized using both qualitative and quantitative syntheses. The qualitative synthesis was used to provide a summary of the characteristics of the participants in the included studies. The quantitative synthesis was carried using both fixed effect model and random effect model meta-analyses to pool together the means and standard deviations of the scores on the outcomes of interest and the study sample sizes in the included studies.

Initially, fixed effect model meta-analysis was used to determine the effect size. The fixed effect model meta-analysis is used based on the assumption that all effect estimates are estimating the same intervention effect (36). In a subsequent step, a sensitivity analysis was carried out using a random-effect model meta-analysis. The random-effect model meta-analysis is used based on the assumption that different studies are estimating different but related intervention effects (36, 37). However, conducting further sensitivity analyses in terms of, for example, time since stroke, the type of outcomes, the interventions used, and other characteristics of the participants in the included studies was not possible due to lack of adequate information. Percentage variation due to heterogeneity between the included studies was determined using I2 statistics. Consequently, I2 statistics values between 50 and 90% at P < 0.05 were regarded to indicate the presence of significant heterogeneity between the included studies.

The meta-analysis was carried out on the respiratory function (forced vital capacity (FVC), forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1), and FEV1/FVC), and motor function (trunk impairment, and internal and external oblique muscle activity). All the meta-analyses were carried out using RevMan version 5.3 software (38). In addition, we did not require further information, and as such, we did not contact the authors of the included studies.

Evidence interpretation

The Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation instrument (GRADE) was used to interpret the evidence (39). It is an instrument that consists of five domains: risks of bias, imprecision, inconsistency, indirectness, and publication bias. The evidence is summarized in a table.

Results

Selection of the included studies

In total, there were 3,088 hits from the literature. Out of these hits, only six studies were eligible for inclusion in the review (40–45). However, two other potential eligible studies were excluded for being a non-randomized trial and having multiple interventions including two different breathing exercises in the experimental group, respectively (16, 46). Details of the literature search and the selection of the studies are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1

The study flowchart.

Characteristics of the included studies

In the included studies, there were 151 patients with stroke, out of which 64 were women. The participants have a mean age ranging from 50.10±3.213 to 73.92±7.93 years and mean time since stroke range between 90.33 ± 69.63 days and 20.33± 8.52 months.

Both participants with ischaemic and hemorrahagic types of stroke were included in the studies. However, the information was provided by only three studies, wherein 55 and 31 of the participants had ischemic and hemorrahgic strokes, respectviely (40, 43, 45). Similarly, only five studies provided information on the side affected, 68 on the right side and 49 on the left side (40, 41, 43–45).

Moreover, only five studies provided information on the participants' height and weight, which we used to calculate their mean BMI (40–42, 44, 45). However, in one of the studies, the BMI value is 25.29kg/m2 for the experimental group (41), which indicates that they have grade I obesity (47).

For the inclusion criteria, diagnosis of stroke was achieved using computed tomography (CT) and/or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in only two studies (41, 43). However, in all the studies, only participants with no significant cognitive impairment were included (40–45). In addition, only four studies provided information on the severity of the disability the included participants had, which was moderate as indicated by the participants' ability to stand independently (40, 41, 43, 45).

For the exclusion criteria, some of the studies excluded participants with musculoskeletal disorders (40–42, 44); previous neurological disorders (40, 43); previous pulmonary disorders (41, 45); cardiac problems (44, 45); pain (40); visual problem (40); and hemineglect (40).

For the differences in the protocols of the included studies, participants performed only diaphragmatic breathing exercise without any additional intervention aside from conventional therapy or usual care in only two studies (40, 43). In the remaining studies, other interventions were added to diaphragmatic breathing exercise (41, 42, 44, 45).

Similarly, the outcomes assessed in the studies include forced vital capacity (FVC) (42, 44, 45); forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) (42, 44, 45); FEV1/FVC (42, 45); peak expiratory flow (PEF) (42, 44, 45); SPO2 (42); motor impairment of the trunk (40, 43); balance (40); cognitive ability (42); muscle activation (41); abdominal muscles thickness (40); and chest circumference (44, 45). Details of the characteristics of the included studies are presented in Table 1.

Table 1

| References | N | Stroke duration | Mean age (years) | BMI (kg/m2) | Intervention | Outcomes | Findings | Adverse events |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kim et al. (40) | Inpatient N = 19; experimental (n = 9, female = 2); control (n = 10, female = 4); | Experimental (16.8 ± 8.6); control (19.3 ± 9.5) months | Experimental (59.1 ± 13.7); control (59.3 ± 10.5) | Experimental (23.95); control (22.87) | Participants in both groups received 60 mins conventional rehabilitation, 3 times a week for 4 weeks. Experimental = diaphragmatic breathing maneuver Control = abdominal drawing-in maneuver In both groups, participants performed the maneuvers and maintained them for 5 seconds with normal breathing, and a 3 second rest afterward. This carried 10 times per session, 3 times a day, 3 times a week for 4 weeks. Between sessions, there was 60 seconds rest. |

Abdominal muscle thickness (ultrasound), motor impairment of the trunk (TIS), and balance (BBS). | All outcomes improved post intervention in both groups. However, motor impairment of the trunk improved more significantly in the experimental group. |

Not reported |

| Seo et al. (41) | N = 30; experimental (n = 15, female = 8); control (n = 15, female = 7); | Experimental (9.1 ± 6.8); control (10.3 ± 3.1) months | Experimental (63.6 ± 3.7); control (66.5 ± 8.1) | Experimental (25.29); control (22.72) | Experimental = 15 minutes inspiratory diaphragm breathing and expiratory pursed-lip breathing exercises in addition to conventional physical therapy consisting of joint mobilization, muscular strengthening and extension exercises, 5 times a week for 4 weeks. Control: received conventional physical therapy consisting of joint mobilization, muscular strengthening and extension exercises for 15 minutes, 5 times a week for 4 weeks. |

Activation of UT, LD, RA, EAO, and IAO. (EMG). | Significantly improvement in the activation of UT, LD, RA, EAO, and IAO occurred only in the experimental group | Dizziness and fatigue |

| Kim et al. (44) | N = 24; experimental (n = 12, female = 2); control (n = 12, female = 4) | Experimental (9.33 ± 1.50); control (9.42 ± 2.07) months | Experimental (64.83 ± 13.10); control (65.42 ± 9.71) | Experimental (23.51); control (23.35) | Participants in both groups received the intervention for 30 mins per day, 3 times a week for 4 weeks. Experimental = diaphragmatic breathing exercise + rib cage joint mobilization. Control = diaphragmatic breathing exercise. |

FVC, FEV1 and PEF (spirometry); chest circumference (tape measure). | FEV1, PEF and upper chest circumference improved more significantly in the experimental groups. | Not reported |

| Rasheed et al. (43) | Outpatient N = 36; experimental (n = 18, female = 9); control (n = 18, female = 10); | Experimental (120.56 ± 75.63); control (90.33 ± 69.63) days | Experimental (59.94 ± 9.14); control (55 ± 10.387) | Not reported | Participants in both groups received physical therapy, 5 times a week for 4 weeks. Experimental = In crook lying position, participants inhaled deeply through the nose so that they could see their abdomen expanding and held this position for 5 seconds and then exhaled through mouth, 10 times per session for total of 3 sessions with 1-minute rest between each session. Control = performed abdominal drawing-in maneuver in crook lying position by drawing-in the lower abdomen (below umbilicus) and tilting the pelvis posteriorly and holding the position for 5 seconds, 10 times per session for total of 3 sessions with 1-minute. |

Motor impairment of the trunk (TIS) | Trunk motor impairment improved in both groups. However, it improved significantly better in the experimental group compared to the controls. | Not reported |

| Yoon et al. (45) | N = 22; experimental (n = 16, female = 6); control (n = 16, female = 7) | Experimental (13.31 ± 2.21); control (12.25 ± 2.14) months | Experimental (73.92 ± 7.93); control (71.09 ± 6.80) | Experimental (22.98); control (24.34) | All participants received comprehensive rehabilitation therapy, including central nervous system training and 30-minute walking exercises, five times a week for 4 weeks Experimental = breathing exercise group performed 20 minutes of diaphragmatic breathing in combination with pursed lip breathing exercises, three times a week for 4 weeks Control = performed 20 minutes of non-resistant cycle ergometer exercise three times a week for 4 weeks |

FVC, FEV1, FVC/FEV1, PEF (spirometry); chest circumference (MEP-MIP); endurance (6MWT) | Only the experimental group improved FVC, FEV1, PEF and chest circumference post intervention. However, both groups improved endurance post intervention. | Not reported |

| Mushtaq et al. (42) | N = 20; experimental (n = 10, female = 2); control (n = 10, female = 3) | Experimental (17.33± 7.13); control (20.33± 8.52) months | Experimental (50.10 ± 3.213); control (55.30 ± 5.945) | Experimental (23.03); control (23.20) | Experimental = diaphragmatic breathing exercise with resistance for 30 minutes + 15 minutes receive digital spirometer training Control = 15 minutes receive digital spirometer training Both groups received the interventions 3 times a week for 4 weeks |

FVC, FEV1, FVC/FEV1 and PEF (spirometry); SPO2 (pulsed oximetry); cognitive ability (K-MMSE) | All outcomes improved post intervention in both groups. However, the improvement in the experimental group is significantly higher than that of the control. | Not reported |

Characteristics of the included studies.

FVC, forced vital capacity; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second; PEF, peak expiratory flow; sEMG, surface electromyography; MIP, maximal inspiratory pressure; MEP, maximal expiratory pressure; FSS, fatigue severity scale; ADL, activities of daily living; FIM, functional independence measure; TIS, trunk impairment scale; BBS, Berg balance scale; K-MMSE, Korean version of minimental state examination; 6MWT, six-minute walk test; UT, upper trapezius; LD, lattismus dorsi; RA, rectus abdominus; EAO, external abdominal oblique; IAO, internal abdominal oblique; EMG, electromyography.

Methodological quality and risks of bias of the included studies

Among the studies, four have high methodological quality (40, 43–45), while the remaining two have moderate methodological quality (41, 42). Details of the methodological quality of the included studies are presented in Table 2.

Table 2

| Study | Eligibility criteria specified | Random allocation | Concealed allocation | Comparable subjects | Blind subjects | Blind therapists | Blind assessors | Adequate follow-up | Intention to treat analysis | Between group comparison | Point estimation and variability | Total score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kim et al. (40) | Yes | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 6/10 |

| Seo et al. (41) | Yes | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 5/10 |

| Kim et al. (44) | Yes | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7/10 |

| Rasheed et al. (43) | Yes | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7/10 |

| Yoon et al. (45) | Yes | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6/10 |

| Mushtaq et al. (42) | Yes | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5/10 |

Methodological quality of the included studies.

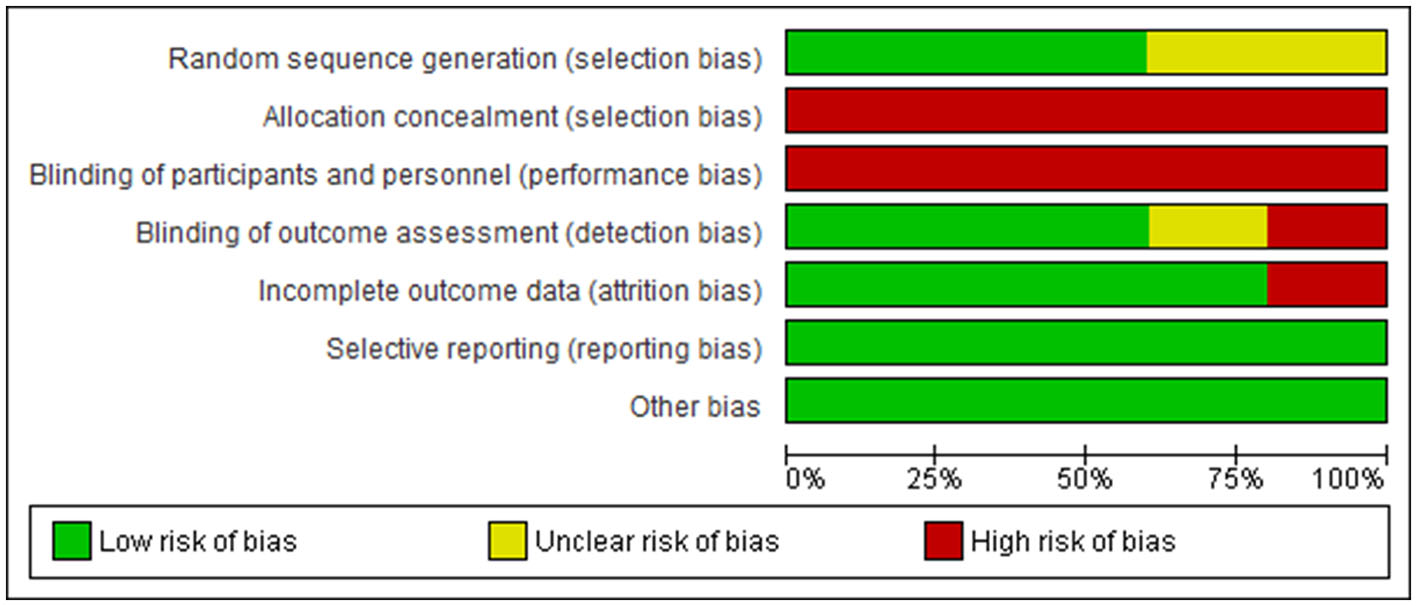

However, in the studies, there are high risks of bias in allocation concealment (selection bias) (40–45); blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) (40, 42–45); incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) (40, 42); and blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) (41, 42, 45). In addition, there is unclear risk of bias in random sequence generation (selection bias) (41, 44) in two of the sudies. See Figure 2 for the risks-of-bias graph.

Figure 2

Risk of bias graph.

Quantitative synthesis

Respiratory function

The test for overall effects post intervention showed that respiratory function improved significantly higher in the experimental group compared with the control (MD = 0.78, 95% CI = 0.67 to 0.89, P < 0.00001). However, the heterogeneity between the included studies is significant (I2=86%, p < 0.00001). See Figure 3A for the forest plot showing the details of the result. In addition, following sensitivity analysis, the test for overall effects post intervention still showed that respiratory function improved significantly higher in the experimental group compared to the control (SMD = 0.96, 95% CI = 0.42 to 1.50, P = 0.0005). See Figure 3B for the details of the result.

Figure 3

(A) Effect of diaphragmatic breathing exercise on respiratory function post-intervention. (B) Effect of diaphragmatic breathing exercise on respiratory function post-intervention (sensitivity analysis).

For the individual respiratory function parameters, FVC improved significantly better in the experimental group compared with the control (MD = 0.90, 95% CI = 0.76 to 1.04, P < 0.00001) post intervention. However, the heterogeneity between the included studies is significant (I2=90%, p < 0.0001). See Figure 3A for the forest plot showing the details of the result.

For FEV1, the experimental group improved significantly better compared to the control (MD = 0.32, 95% CI = 0.11 to 0.52, P = 0.002) post intervention. In addition, there is no significant heterogeneity between the included studies (I2=90%, p = 0.92). See Figure 3A for the forest plot showing the details of the result.

For PEF, the experimental group improved significantly better compared to the control (MD = 1.48, 95% CI = 1.15 to 1.81, P < 0.00001) post intervention. However, the heterogeneity between the included studies is significant (I2=80%, p = 0.006). See Figure 3A for the forest plot showing the details of the result.

For FEV1/FVC, the result showed that the experimental group is not significantly better than the control (MD = 0.26, 95% CI = −0.65 to 1.16, P = 0.58) post intervention. In addition, there is significant heterogeneity between the included studies (I2= 86%, p < 0.00001). See Figure 3A for the forest plot showing the details of the result.

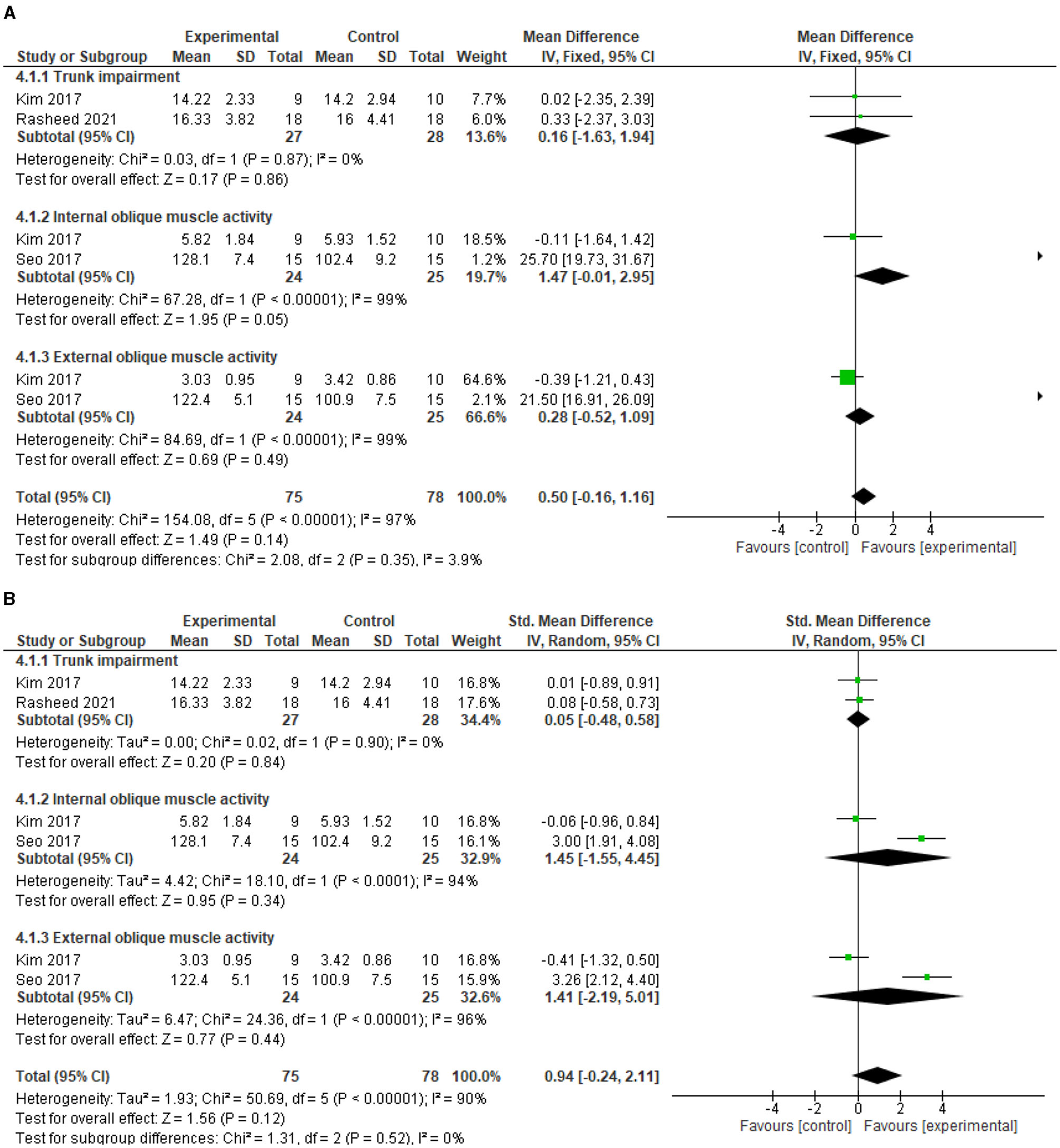

Motor function

The test for overall effects post intervention showed that the experimental group is not superior to the control (MD = 0.5, 95% CI = −0.16 to 1.16, P = 0.14) post intervention, although there was a trend toward better improvement in the experimental group. In addition, there was significant heterogeneity between the included studies (I2= 97%, p < 0.00001). See Figure 4A for the forest plot showing the details of the result. In addition, following sensitivity analysis, the test for overall effects post intervention still showed that motor impairment of the trunk did not improve significantly higher in the experimental group compared with the control (SMD = 0.94, 95% CI = −0.24 to 2.11, P = 0.12). See Figure 4B for the details of the result.

Figure 4

(A) Effect of diaphragmatic breathing exercise on motor function post-intervention. (B) Effect of diaphragmatic breathing exercise on motor function post-intervention (sensitivity analysis).

For the individual motor impairment of trunk parameters, trunk impairment did not improve significantly better in the experimental group compared with the control (MD = 0.16, 95% CI = −1.63 to 1.94, P = 0.86) post intervention. However, the heterogeneity between the included studies is not significant (I2=0%, p = 0.87). See Figure 4A for the forest plot showing the details of the result.

For motor activity of internal abdominal oblique muscle, there was a trend toward better improvement in the experimental group compared to the control (MD = 1.47, 95% CI = −0.01 to 2.95, P = 0.05) post intervention. However, there is significant heterogeneity between the included studies (I2= 99%, p < 0.00001). See Figure 4A for the forest plot showing the details of the result.

For motor activity of external abdominal oblique muscle, the experimental group did not improve significantly better compared to the control (MD = 0.28, 95% CI = −0.52 to 1.09, P = 0.49) post intervention. In addition, the heterogeneity between the included studies is significant (I2=99%, p < 0.00001). See Figure 4A for the forest plot showing the details of the result.

Interpretation of the evidence

Based on the current available literature, there is limited evidence on the superior effect of deep breathing exercise compared with the control on FVC, FEV1, and PEF in patients with stroke. See Table 3 for the details of the interpretation of the evidence.

Table 3

| Number of participants | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | Number of studies | Risks of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Experimental | Control | Effect size (95% CI) | Overall certainty of the evidence |

| FVC | 3 | Serious | Very seriousa | Not serious | Serious | 38 | 38 | −0.90 (0.76 to 1.04) | ⊕⊕○○ Low |

| FEV1 | 3 | Serious | Very seriousa | Not serious | Serious | 38 | 38 | −0.32 (0.11 to 0.52) | ⊕⊕○○ Low |

| PEF | 3 | Serious | Very seriousa | Not serious | Serious | 38 | 38 | 1.48 (1.15 to 1.81) | ⊕⊕○○ Low |

| FEV1/FVC | 2 | Serious | Not serious | Not serious | Serious | 28 | 28 | 0.26 (−0.65 to 1.16) | ⊕⊕○○ Low |

| Trunk impairment | 2 | Serious | Not serious | Not serious | Serious | 27 | 28 | 0.16 (1.63 to 1.94) | ⊕⊕○○ Low |

Evidence quality assessment.

asignificant heterogeneity.

bsample size < 400.

Discussion

The aim of this study is to determine the effects of diaphragmatic breathing exercise on respiratory, cognitive, and motor functions outcomes after stroke. The results showed that diaphragmatic breathing exercise is only superior to the control at improving FVC, FEV1, and PEF. Outcomes such as the FVC, FEV1, FEV1/FVC, PEF, MIP, MEP, motor impairment of the trunk, abdominal muscles thickness, balance, and cognitive ability are required to effectively carry out the activities of daily living (ADL) (25, 48).

The ability to carry out ADL gets impaired following a stroke (49, 50). The inability to carry out ADL can result in reduced quality of life (27, 51). Thus, improving ADL and increasing quality of life are the most significant goals in stroke rehabilitation (52, 53). Diaphragmatic breathing exercise can be used to help improve respiratory function and functional outcomes that will eventually translate to improvement in the patients' ability to carry out ADL and increase in their quality of life. This is because diaphragmatic breathing helps to improve delivery of oxygen to tissues, which is important for various metabolic activities in the body (21, 54). However, it should be noted that outcomes such as trunk motor impairment, abdominal muscle thickness, balance, and cognitive capacity may also be necessary for the effective performance of activities of daily living. As a result, our findings need to be interpreted with caution.

It is also important to note that most of the studies included in the review used participants who have normal BMI and moderate disability. Mechanics of the lungs and the chest wall are altered with increasing BMI because of fat deposit in the mediastinum and the abdominal cavity (55). In addition, respiratory function has significant correlation with functional ability (56). Therefore, it is possible that most of the participants in the included studies had moderate impairment in respiratory function as well. Thus, the findings seem to suggest that diaphragmatic breathing exercise improves outcomes in patients with stroke who have moderate disability.

Although the result of the meta-analysis showed that there was no significant difference in motor function between groups post intervention, there was a trend toward better improvement in motor function in the experimental group. Thus, it is possible that the effect on motor function in favor of the experimental group was masked by confounding or control variables such as the small number of studies included in the meta-analysis and/or their small sample sizes. Small sample size can undermine the effect of an intervention (57). Similarly, for cognitive function, there was no adequate number of studies to carry out a meta-analysis. Therefore, future studies on the effect of diaphragmatic breathing exercise in patients with stroke should assess both cognitive and motor function outcomes in addition to those of respiratory function. This is because diaphragmatic breathing exercise may have the potential to enhance improvement in cognitive and motor functions after stroke.

In addition, the findings of the study should be interpreted in light of several factors. First, there is significant heterogeneity in most of the results of the study outcomes which can undermine the validity and reliability of the result (58). This heterogeneity might be caused by the use of different control group interventions, outcome measures, and probably other characteristics of the participants in the included studies. Similarly, in most of the studies, diaphragmatic breathing exercise was not practiced as a stand-alone intervention; it was combined with other forms of interventions such as the pursed-lip breathing exercise. Such exercises are reported to improve respiratory function and other outcomes after stroke (59, 60). Thus, it is probably way better if diaphragmatic breathing exercise is used as an adjunct therapy in combination with other interventions such as pursed-lip breathing and relaxation training (46).

Similarly, it is worth noting that diaphragmatic breathing exercise is not without any adverse events. This is because adverse events such as dizziness and fatigue can occur during breathing exercises (41). Therefore, it should be administered with caution, close monitoring, and supervision. In addition, in most of the studies, the intensity of diaphragmatic breathing exercise used is not clear. Lack of clarity in the protocol of an intervention can affect its reproducibility; and clinical replicability must be considered in RCTs (61). Therefore, it is important that studies determining the effects of diaphragmatic breathing exercise on outcomes after stroke be standardized and well-controlled.

Furthermore, although the present study has some strengths such as extensive literature search of multiple databases, it is also not without limitations. One of these limitations is the exclusion of any literature published in languages other than English. This exclusion might have limited the contributions of many quality studies on the subject matter. Additionally, we included studies with variability in the protocols of breathing exercise, wherein some studies used breathing exercise in addition to other intervention which is another potential limitation that can affect the generalizability of this study. Thus, interpretation of the findings of this study should be made in light of all its potential limitations.

Conclusion

There is limited evidence that diaphragmatic breathing exercise may help improve FVC, FEV1, and PEF which may in turn enhance recovery of function post stroke. Therefore, there should be more consideration given to implementing of diaphragmatic breathing exercise for the rehabilitation of some patients with stroke. However, the significant statistical heterogeneity between studies in some of the outcomes should be noted when interpreting the findings of this study. Thus, standardized and well-controlled RCTs should be conducted to further determine this effect, required intensity, and the most suitable protocol.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

Design, data collection, and critical review of the manuscript: AA, TW, and SN. Writing of the draft: AA. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This study was supported by the Faculty Collaborative Research Scheme between Social Sciences and Health Sciences (P0043965), the Hong Kong Polytechnic University awarded to SN and her team, and PolyU Distinguished Postdoctoral Fellowship Scheme (P0035217).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fneur.2023.1233408/full#supplementary-material

References

1.

Kamper DG Fischer HC Cruz EG Rymer WZ . Weakness is the primary contributor to finger impairment in chronic stroke. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. (2006) 87:1262–9. 10.1016/j.apmr.2006.05.013

2.

Zorowitz RD Gillard PJ Brainin M . Poststroke spasticity: sequelae and burden on stroke survivors and caregivers. Neurology. (2013) 80:S45–52. 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182764c86

3.

Al-Qazzaz NK Ali SH Ahmad SA Islam S Mohamad K . Cognitive impairment and memory dysfunction after a stroke diagnosis: a post-stroke memory assessment. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. (2014) 10:1677–91. 10.2147/NDT.S67184

4.

Catalá-Ripoll JV Monsalve-Naharro J Hernández-Fernández F . Incidence and predictive factors of diaphragmatic dysfunction in acute stroke. BMC Neurol. (2020) 20:79. 10.1186/s12883-020-01664-w

5.

Lee K Lee D Hong S Shin D Jeong S Shin H et al . The relationship between sitting balance, trunk control and mobility with predictive for current mobility level in survivors of sub-acute stroke. PLoS ONE. (2021) 16:e0251977. 10.1371/journal.pone.0251977

6.

Jijimol G Fayaz RK Vijesh PV . Correlation of trunk impairment with balance in patients with chronic stroke. NeuroRehabilitation. (2013) 32:323–5. 10.3233/NRE-130851

7.

Verheyden G Vereeck L Truijen S Troch M Herregodts I Lafosse C et al . Trunk performance after stroke and the relationship with balance, gait and functional ability. Clin Rehabil. (2006) 20:451–8. 10.1191/0269215505cr955oa

8.

Saunders SW Rath D Hodges PW . Postural and respiratory activation of the trunk muscles changes with mode and speed of locomotion. Gait Posture. (2004) 20:280–90. 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2003.10.003

9.

Jung KJ Park JY Hwang DW Kim JH Kim JH . Ultrasonographic diaphragmatic motion analysis and its correlation with pulmonary function in hemiplegic stroke patients. Ann Rehabil Med. (2014) 38:29–37. 10.5535/arm.2014.38.1.29

10.

Ezeugwu VE Olaogun M Mbada CE Adedoyin R . Comparative lung function performance of stroke survivors and age-matched and sex-matched controls. Physiother Res Int. (2013) 18:212–9. 10.1002/pri.1547

11.

Bordoni B Purgol S Bizzarri A Modica M Morabito B . The influence of breathing on the central nervous system. Cureus. (2018) 10:e2724. 10.7759/cureus.2724

12.

Kocjan J Adamek M Gzik-Zroska B Czyzewski D Rydel M . Network of breathing. Multifunctional role of the diaphragm: a review. Adv Respir Med. (2017) 85:224–32. 10.5603/ARM.2017.0037

13.

Dechman G Wilson CR . Evidence underlying breathing retraining in people with stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Phys Ther. (2004) 84:1189–97. 10.1093/ptj/84.12.1189

14.

Gosselink R . Breathing techniques in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (copd). Chron Respir Dis. (2004) 1:163–72. 10.1191/1479972304cd020rs

15.

Netti N Suryarinilsih Y . Effectiveness of range of motion (rom) and deep breathing exercise (dbe) in increasing muscle strength in post-stroke patients at pariaman hospital in (2018). Malaysian J Nurs (MJN). (2022) 14:128–32. 10.31674/mjn.2022.v14i02.021

16.

Shetty N Samuel SR Alaparthi GK Amaravadi SK Joshua AM Pai S . Comparison of diaphragmatic breathing exercises, volume, and flow-oriented incentive spirometry on respiratory function in stroke subjects: a non-randomized study. Ann Neurosci. (2020) 27:232–41.

17.

Rama S Ballentine R Hymes A . Science of breath: A practical guide. Honesdale, PA: Himalayan Institute Press. (1998).

18.

Vieira DSR Mendes LPS Elmiro NS Velloso M Britto RR Parreira VF . Breathing exercises: Influence on breathing patterns and thoracoabdominal motion in healthy subjects. Braz J Phys Ther. (2014) 18:544–52 10.1590/bjpt-rbf.2014.0048

19.

Cahalin LP Braga M Matsuo Y Hernandez ED . Efficacy of diaphragmatic breathing in persons with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a review of the literature. J Cardiopulm Rehabil. (2002) 22:7–21. 10.1097/00008483-200201000-00002

20.

Fernandes M Cukier A Feltrim MI . Efficacy of diaphragmatic breathing in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Chron Respir Dis. (2011) 8:237–44. 10.1177/1479972311424296

21.

McLellan SA Walsh TS . Oxygen delivery and haemoglobin. Cont Edu Anaesth Crit Care & Pain. (2004) 4:123–6. 10.1093/bjaceaccp/mkh033

22.

Carreau A Hafny-Rahbi BE Matejuk A Grillon C Kieda C . Why is the partial oxygen pressure of human tissues a crucial parameter? Small molecules and hypoxia. J Cellular Mol Med. (2011) 15:1239–53. 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2011.01258.x

23.

Ma X Yue ZQ Gong ZQ Zhang H Duan NY Shi YT et al . The effect of diaphragmatic breathing on attention, negative affect and stress in healthy adults. Front Psychol. (2017) 8:874. 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00874

24.

An HJ Kim AY Park SJ . Immediate effects of diaphragmatic breathing with cervical spine mobilization on the pulmonary function and craniovertebral angle in patients with chronic stroke. Medicina (Kaunas). (2021). 57:826. 10.3390/medicina57080826

25.

Wei H Sheng Y Peng T Yang D Zhao Q Xie L et al . Effect of pulmonary function training with a respirator on functional recovery and quality of life of patients with stroke. Contrast Media Mol Imaging. (2022) 2022:6005914. 10.1155/2022/6005914

26.

Boz K Saka S Çetinkaya I . The relationship of respiratory functions and respiratory muscle strength with trunk control, functional capacity, and functional independence in post-stroke hemiplegic patients. Physiother Res Int. (2023) 28:e1985. 10.1002/pri.1985

27.

Kim K Kim YM Kim EK . Correlation between the activities of daily living of stroke patients in a community setting and their quality of life. J Phys Ther Sci. (2014) 26:417–9. 10.1589/jpts.26.417

28.

Yamamoto H Takeda K Koyama S Morishima K Hirakawa Y Motoya I et al . Relationship between upper limb motor function and activities of daily living after removing the influence of lower limb motor function in subacute patients with stroke: a cross-sectional study. Hong Kong J Occup Ther. (2020) 33:12–7. 10.1177/1569186120926609

29.

Einstad MS Saltvedt I Lydersen S Ursin MH Munthe-Kaas R Ihle-Hansen H et al . Associations between post-stroke motor and cognitive function: a cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr. (2021) 21:103. 10.1186/s12877-021-02055-7

30.

Stolwyk RJ Mihaljcic T Wong DK Chapman JE Rogers JM . Poststroke cognitive impairment negatively impacts activity and participation outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Stroke. (2021) 52:748–60. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.032215

31.

Higgins JP Altman DG Gøtzsche PC Jüni P Moher D Oxman AD et al . The cochrane collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. (2011) 343:d5928. 10.1136/bmj.d5928

32.

Maher CG Sherrington C Herbert RD Moseley AM Elkins M . Reliability of the pedro scale for rating quality of randomized controlled trials. Phys Ther. (2003) 83:713–21. 10.1093/ptj/83.8.713

33.

Herbert R Moseley A Sherrington C . Pedro: a database of randomised controlled trials in physiotherapy. Health Inf Manag. (1998) 28:186–8. 10.1177/183335839902800410

34.

Moseley AM Herbert RD Maher CG Sherrington C Elkins MR . Reported quality of randomized controlled trials of physiotherapy interventions has improved over time. J Clin Epidemiol. (2011) 64:594–601. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.08.009

35.

da Costa BR Hilfiker R Egger M . Pedro's bias: summary quality scores should not be used in meta-analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. (2013) 66:75–7. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2012.08.003

36.

Kanters S . Fixed- and random-effects models. Methods Mol Biol. (2022) 2345:41–65. 10.1007/978-1-0716-1566-9_3

37.

Higgins JP Thompson SG Spiegelhalter DJ . A re-evaluation of random-effects meta-analysis. J R Stat Soc Ser A Stat Soc. (2009) 172:137–59. 10.1111/j.1467-985X.2008.00552.x

38.

Review Manager Web (RevMan Web) . RevMan Web, (Version 5.4) (2020). The Cochrane Collaboration. Available online at: revman.cochrane.org

39.

Guyatt GH Oxman AD Vist GE Kunz R Falck-Ytter Y Alonso-Coello P et al . Grade: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. Bmj. (2008) 336:924–6. 10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.AD

40.

Kim SK Kang T Park D Lee J-H Cynn H-s . Four-week comparative effects of abdominal drawing-in and diaphragmatic breathing maneuvers on abdominal muscle thickness, trunk control, and balance in patients with chronic stroke. Phys Ther Korea. (2017) 24:10–20. 10.12674/ptk.2017.24.3.010

41.

Seo K Hwan PS Park K . The effects of inspiratory diaphragm breathing exercise and expiratory pursed-lip breathing exercise on chronic stroke patients' respiratory muscle activation. J Phys Ther Sci. (2017) 29:465–9. 10.1589/jpts.29.465

42.

Mushtaq H Aftab A Iqbal A Muzummil A Altaf S . Effects of resistive diaphragmatic training on the pulmonary functions in patients with chronic stroke. Pak J Med Health Sci. (2023) 17:4. 10.53350/pjmhs202317179

43.

Rasheed H Ahmad I Javed MA Rashid J Javeed RS . Effects of diaphragmatic breathing maneuver and abdominal drawing-in maneuver on trunk stability in stroke patients. Phys Occup Ther Geriatr. (2021) 39:1–10. 10.1080/02703181.2020.1770395

44.

Kim ASY Hong G Kim D Kim S . Effects of rib cage joint mobilization combined with diaphragmatic breathing exercise on the pulmonary function and chest circumference in patients with stroke. J Int Acad Phys Ther Res. (2020) 11:6. 10.20540/JIAPTR.2020.11.3.2113

45.

Yoon J-M Im S-C Kim K . Effects of diaphragmatic breathing and pursed lip breathing exercises on the pulmonary function and walking endurance in patients with chronic stroke: a randomised controlled trial. Int J Ther Rehabil. (2022) 29:1–11. 10.12968/ijtr.2021.0027

46.

Deng W Yang M Shu X Wu Z Xu F Chang R . Respiratory training combined with core training improves lower limb function in patients with ischemic stroke. Am J Transl Res. (2023) 15:1880−8.

47.

Nuttall FQ . Body mass index: Obesity, BMI, and health: a critical review. Nutr Today. (2015) 50:117–28. 10.1097/NT.0000000000000092

48.

Lee PH Yeh TT Yen HY Hsu WL Chiu VJ Lee SC . Impacts of stroke and cognitive impairment on activities of daily living in the taiwan longitudinal study on aging. Sci Rep. (2021) 11:12199. 10.1038/s41598-021-91838-4

49.

Blomgren C Jood K Jern C Holmegaard L Redfors P Blomstrand C et al . Long-term performance of instrumental activities of daily living (iadl) in young and middle-aged stroke survivors: Results from sahlsis outcome. Scand J Occup Ther. (2018) 25:119–26. 10.1080/11038128.2017.1329343

50.

Wolfe CD Crichton SL Heuschmann PU McKevitt CJ Toschke AM Grieve AP et al . Estimates of outcomes up to ten years after stroke: Analysis from the prospective south london stroke register. PLoS Med. (2011) 8:e1001033. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001033

51.

Fatema Z Sigamani AGV Manuel D . ‘Quality of life at 90 days after stroke and its correlation to activities of daily living': a prospective cohort study. J Stroke Cerebrovas Dis. (2022) 31:106806. 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2022.106806

52.

O'Sullivan SB Schmitz TJ Fulk G . Physical Rehabilitation. Philadelphia, PA: FA Davis. (2019).

53.

Rice DB McIntyre A Mirkowski M Janzen S Viana R Britt E et al . Patient-centered goal setting in a hospital-based outpatient stroke rehabilitation center. PM&R. (2017) 9:856–65. 10.1016/j.pmrj.2016.12.004

54.

Russo MA Santarelli DM O'Rourke D . The physiological effects of slow breathing in the healthy human. Breathe (Sheff). (2017) 13:298–309. 10.1183/20734735.009817

55.

Dixon AE Peters U . The effect of obesity on lung function. Expert Rev Respir Med. (2018) 12:755–67. 10.1080/17476348.2018.1506331

56.

Santos R Dall'Alba SCF Forgiarini SGI Rossato D Dias AS Forgiarini LA . Relationship between pulmonary function, functional independence, and trunk control in patients with stroke. Arquivos de Neuro-Psiquiatria. (2019) 77:387–92. 10.1590/0004-282x20190048

57.

Faber J Fonseca LM . How sample size influences research outcomes. Dental Press J Orthod. (2014) 19:27–9. 10.1590/2176-9451.19.4.027-029.ebo

58.

Ward SL Flori HR . Evaluating the impact of heterogeneity on results of meta analyses evaluating nutritional status and clinical outcomes in pediatric intensive care. Clin Nutr. (2021) 40:5440–1. 10.1016/j.clnu.2021.09.016

59.

Lee D-K . The effect of breathing training on the physical function and psychological problems in patients with chronic stroke. J Korean Phys Ther. (2020) 32:6. 10.18857/jkpt.2020.32.3.146

60.

Menezes KK Nascimento LR Avelino PR Alvarenga MTM Teixeira-Salmela LF . Efficacy of interventions to improve respiratory function after stroke. Respir Care. (2018) 63:920–33. 10.4187/respcare.06000

61.

Negrini S Arienti C Pollet J Engkasan JP Francisco GE Frontera WR et al . Clinical replicability of rehabilitation interventions in randomized controlled trials reported in main journals is inadequate. J Clin Epidemiol. (2019) 114:108–17. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2019.06.008

Summary

Keywords

stroke, breathing exercises, vital capacity, forced expiratory volume, maximal respiratory pressures, activities of daily living, quality of life

Citation

Abdullahi A, Wong TWL and Ng SSM (2024) Efficacy of diaphragmatic breathing exercise on respiratory, cognitive, and motor function outcomes in patients with stroke: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Neurol. 14:1233408. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2023.1233408

Received

27 June 2023

Accepted

28 December 2023

Published

12 January 2024

Volume

14 - 2023

Edited by

Sławomir Kujawski, Nicolaus Copernicus University in Toruń, Poland

Reviewed by

Ni Luh Putu Dewi Puspawati, Wira Medika Bali College of Health Sciences (STIKes), Indonesia

Victor Marinho, Federal University of the Parnaíba Delta, Brazil

Updates

Copyright

© 2024 Abdullahi, Wong and Ng.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Shamay SM Ng shamay.ng@polyu.edu.hk

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.