- Integrative Multiomics Laboratory, Department of Biotechnology, School of Bio Sciences and Technology, Vellore Institute of Technology, Vellore, India

Migraine is a primary headache disorder characterized by unilateral pain usually with aura, that affects approximately one in six individuals in India. The underlying biomechanical processes of migraine are still poorly understood, and new research is constantly being published. One of the major factors in migraine pathogenesis is the dysfunction of ion channels in the trigeminal nuclei and sensory cortices. Potassium channels are modulators and regulators of neuronal signaling and conductance, playing an important role in maintenance of the membrane potential and neuronal conduction. Therefore, potassium channel dysfunctions are potential factors in migraine pathogenesis, and thus targets for specific antimigraine prophylaxis. This review reveals that potassium channels play a significant role in pathogenesis and management of migraine. Dysfunctions in KATP channels, K2P channels including TRESK and TREK-1, small and large conductance calcium-sensitive potassium channels (SKCa and BKCa), and voltage-gated potassium channels (KV) are known to affect the incidence and progression of migraine in the general populace. KATP openers can induce migraine like phenotype, but KATP blockers have so far not been effective in reducing the intensity of migraine headache. Potassium channels are a potential druggable target for migraine prophylaxis with several compounds currently in preclinical trials.

1 Introduction

Migraine can be defined as an recurrent headache disorder (1), and is diagnosed clinically based on criteria outlined in ICHD–3 (2). It is one of eleven primary headache disorders (3). It consists of unilateral acute or chronic period headaches with some presentation of nausea and/or light, sound, or smell sensitivity (1, 4). For a while, migraine was considered as a primarily vascular disorder with neurological symptoms emerging as epiphenomenons due to vascular changes; however, that theory is no longer considered viable (5–7). Vasodilation or constriction is instead thought to be an emergent symptom as a result of instability in neuronal control mechanisms (8).

Migraine presents in four stages that each occur sequentially from or simultaneously with the previous: premonitory symptoms or prodrome, aura, headache, and postdrome (1, 4). Aura may not be apparent in all cases of migraine.

The genetic or inheritable factors influencing migraine are varied and poorly understood. Several genes have been implicated in familial hemiplegic migraine, and in chronic and acute migraine, both nuclear and mitochondrial in origin (9–12). The exact functional impact of these genes in predisposition to migraine is not yet fully elucidated, but several theories have been put forth (9–12).

2 Mechanisms underlying migraine symptoms

The current understanding of the mechanisms underlying migraine is as follows:

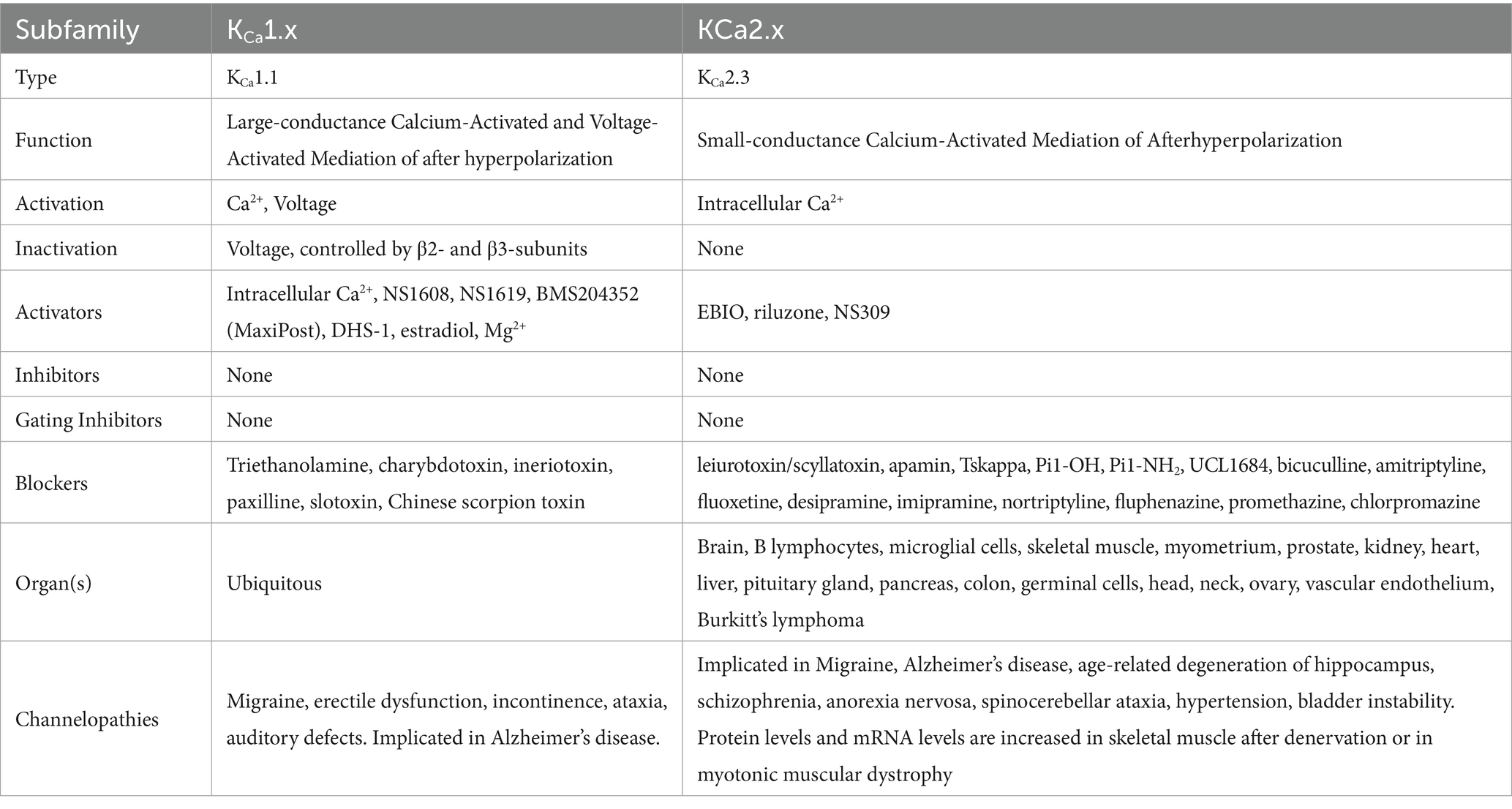

A dysfunction of neuronal polarization in the brain results in a sequence of intracranial and extracranial changes that result in migraine symptoms (1, 4). Figure 1 shows the currently accepted mechanism behind migraine attacks.

Figure 1. Mechanisms of migraine—environmental triggers and genetic predisposition result in cortical spreading depression, which has three effects: irregular activation of cortices, which results in aura and sensitivity to senses; and triggering of trigeminal nerves and increased permeability of blood–brain barrier, which result in pain due to vasodilation and sterile inflammation.

2.1 Cortical spreading depression

The phenomenon known as cortical spreading depression (CSD), first described by Leão in 1944 (13, 14), is the currently accepted physiological phenomenon that causes both headaches and aura in migraine (5). CSD is a wave of depolarization that spreads across the nerves and glial cells in the cerebral cortex in a self-propagating manner. CSD has been theorized to:

1. Directly cause the aura in migraine through abnormal activation of neurons in the sensory cortices (15).

2. Induce altered nociception by activating trigeminal nerve afferents (16, 17), and

3. Alter the permeability of the blood–brain barrier (18).

The activation of afferent nerves to the trigeminal nerves, resulting in inflammatory changes in pain-sensitive regions of the meninges, causes the headache of migraine (18). A molecular cascade of events—likely involving pannexin-1, capsase-1, and several proinflammatory mediators (16, 17)—is the likely pathway linking CSD to the prolonged activation of trigeminal nociception that is the generating source of the pain of migraine. Migraine without aura might be linked to CSD in regions of the brain where the depolarization does not result in sensory alteration (19).

2.2 The trigeminovascular system

The trigeminovascular system is a primarily nociceptive system of neurons consisting of several small caliber pseudo-unipolar sensory neurons that originate from the trigeminal ganglion and cervical dorsal roots (20), before spreading to innervate cerebral vessels, vessels in the pia and dura matters, and venous sinuses. The nerves from the cervical roots and the trigeminal ganglion converge at the trigeminal nucleus caudalis (21, 22). The trigeminovascular system also receives signals from a vast array of regions in the brain and brain-stem (20, 23–32) and transmits nociceptive signals to the limbic system for the emotional and vegetative processes following pain (30).

The activation of the trigeminovascular system either by physical pain signals or CSD results in the release of vasoactive compounds including Substance P, calcitonin gene related peptide (CGRP), and Neurokinin A (33). These result in vasodilation and neurogenic inflammation, which are both important in the prolongation and intensification of pain from migraine (34).

3 Review methodology

Articles were retrieved from PubMed and SCOPUS in a manner respecting the PRISMA–2020 guidelines using the following search criteria (exact text was modified for SCOPUS to adhere to the functional words in the SCOPUS search engine):

1. (potassium channels) AND (migraine)

2. ((potassium channels) AND (migraine)) AND (treatment)

3. (potassium channels) AND (channelopathies)

4. (voltage gated potassium channels) AND (channelopathies)

5. (calcium gated potassium channels) AND (channelopathies)

6. (ATP sensitive potassium channels) AND (channelopathies)

7. (two-pore domain gated potassium channels) AND (channelopathies)

8. (inward rectifying potassium channels) AND (channelopathies)

Bulk deduplication was done using a deduplicator plugin for Zotero, and the results manually curated.

The following screening, inclusion, and exclusion criteria were used to refine the results:

1. Screening criteria:

a) DOI leads to empty or broken website

b) source type is correspondence, editorial, operative editorial, or other form of non-rigorous writing

c) article not in English AND English translation cannot be acquired or generated

2. Inclusion criteria:

a) Discusses potassium channels with respect to migraine

3. Exclusion criteria:

a) Article focused on disease other than migraine

b) Article focused on molecule other than potassium channel protein

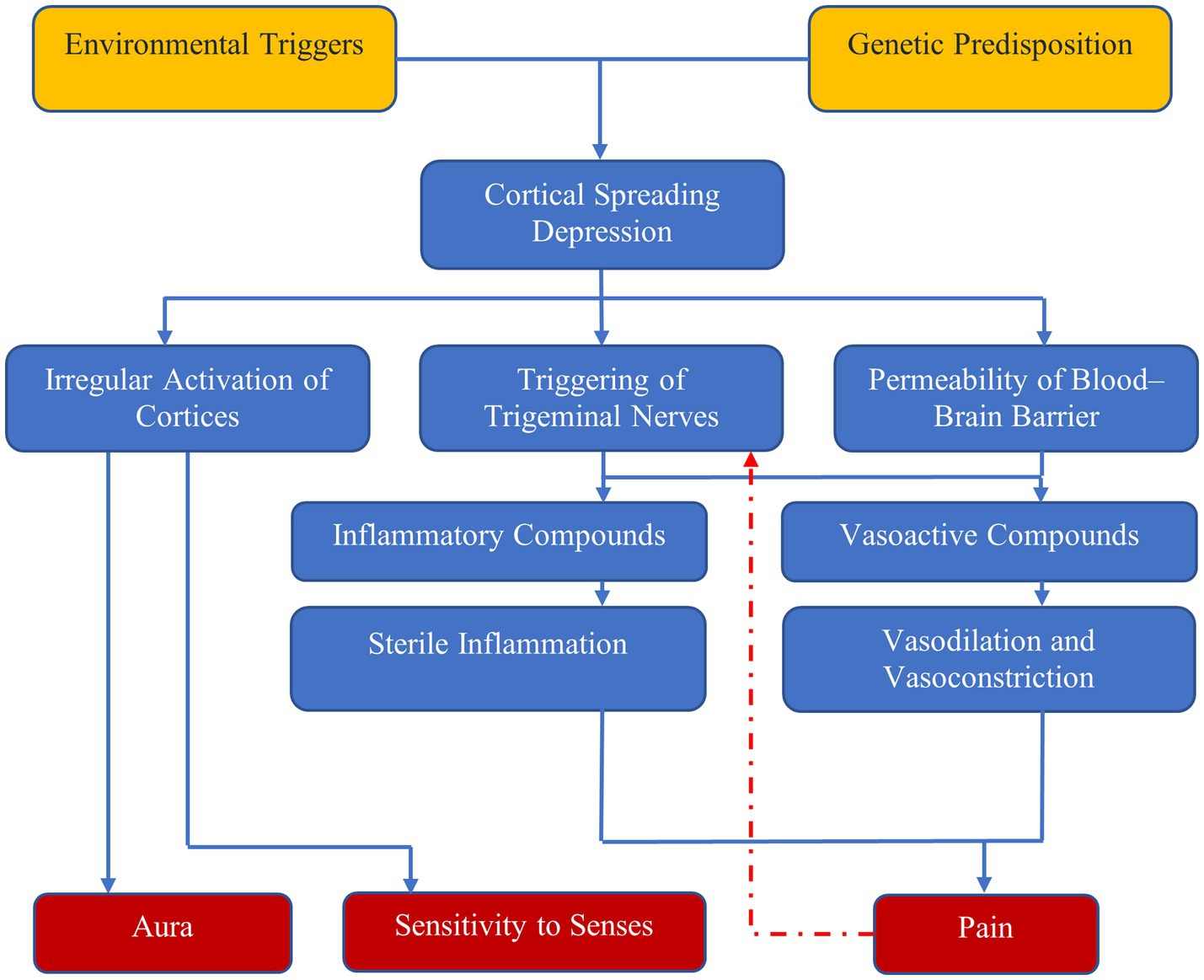

Figure 2 shows retrieval, screening, and assessment process for the review. Supplementary Table 1 holds the final set of included articles with the information contained relevant to the review.

Figure 2. Flowchart showing the retrieval, screening, and assessment process for the review generated using the web tool PRISMA2020 (183).

4 Ion channels

Ion channels are pore-forming transmembrane proteins that facilitate the transfer of ions across the cell membrane. Ion channels are found in most cells across various tissues, however the ion channels implicated in migraine are those found in neural tissues and the endothelial, epithelial, or smooth muscle cells of the vascular tissues (35–44). As ion channels are essential agents in the creation and propagation of potential across the neuronal cells, it is no surprise that several ion channel proteins have been implicated in hereditary forms of migraine. The voltage-gated calcium channel coded by members of the CACNA1 family of genes, the sodium-potassium ATPase pumps from the ATP1A family of genes, and the voltage-gated sodium channel coded by the SCN1A gene have been long associated with familial hemiplegic migraine (40, 43–59). However, these same channels do not seem to be associated with non-hemiplegic migraine (46), and therefore there must be a different channel or channels that are involved more closely with these types of migraine.

4.1 Potassium channels

Potassium channels are regulatory channels that control cell potential, and the secretion of hormones and neurotransmitters, and modulate the frequency and shape of the action potential waveform both in the peripheral and central nervous systems. They are regulated in turn by either transmembrane voltage, calcium ions, or neurotransmitters, or by the very signal pathways they stimulate. Potassium channels are classified into three families, depending on the number of transmembrane domains in the protein structure: Two Trans-Membrane Domains (2TM), Four Trans-Membrane Domains (4TM), and Six Trans-Membrane Domains (6TM) (39).

4.1.1 2TM channels

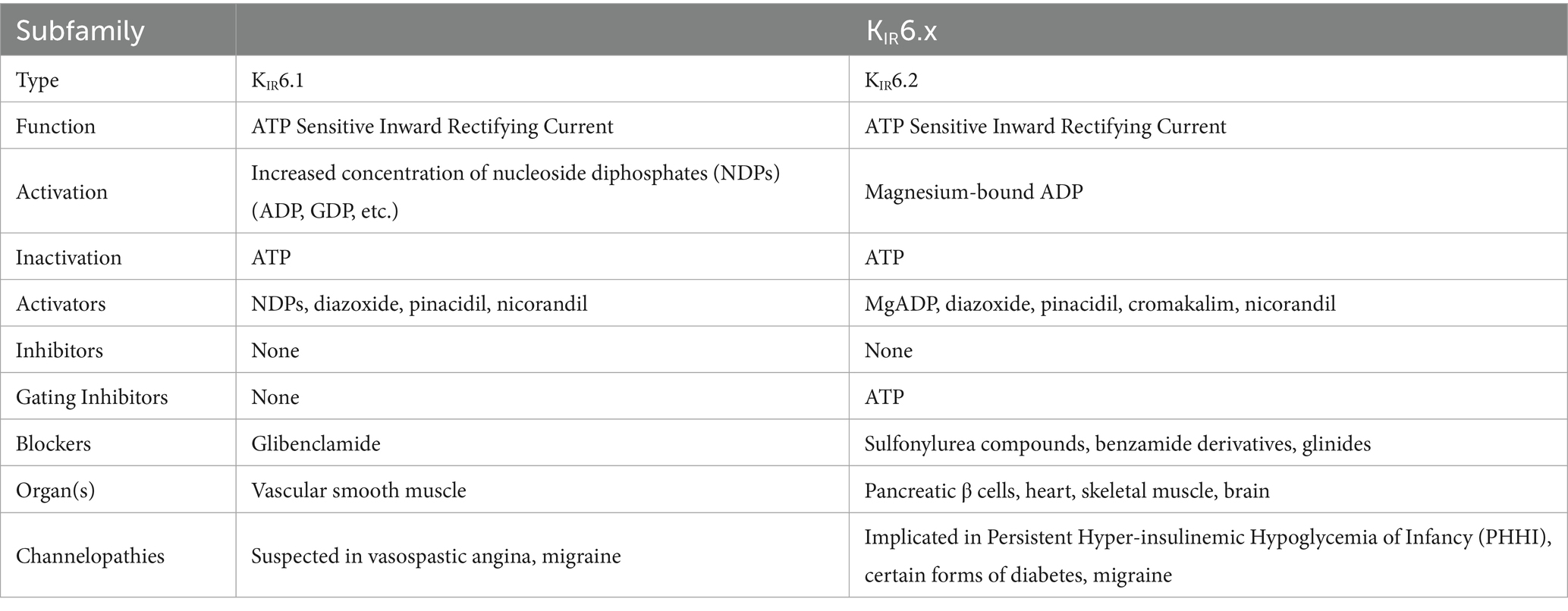

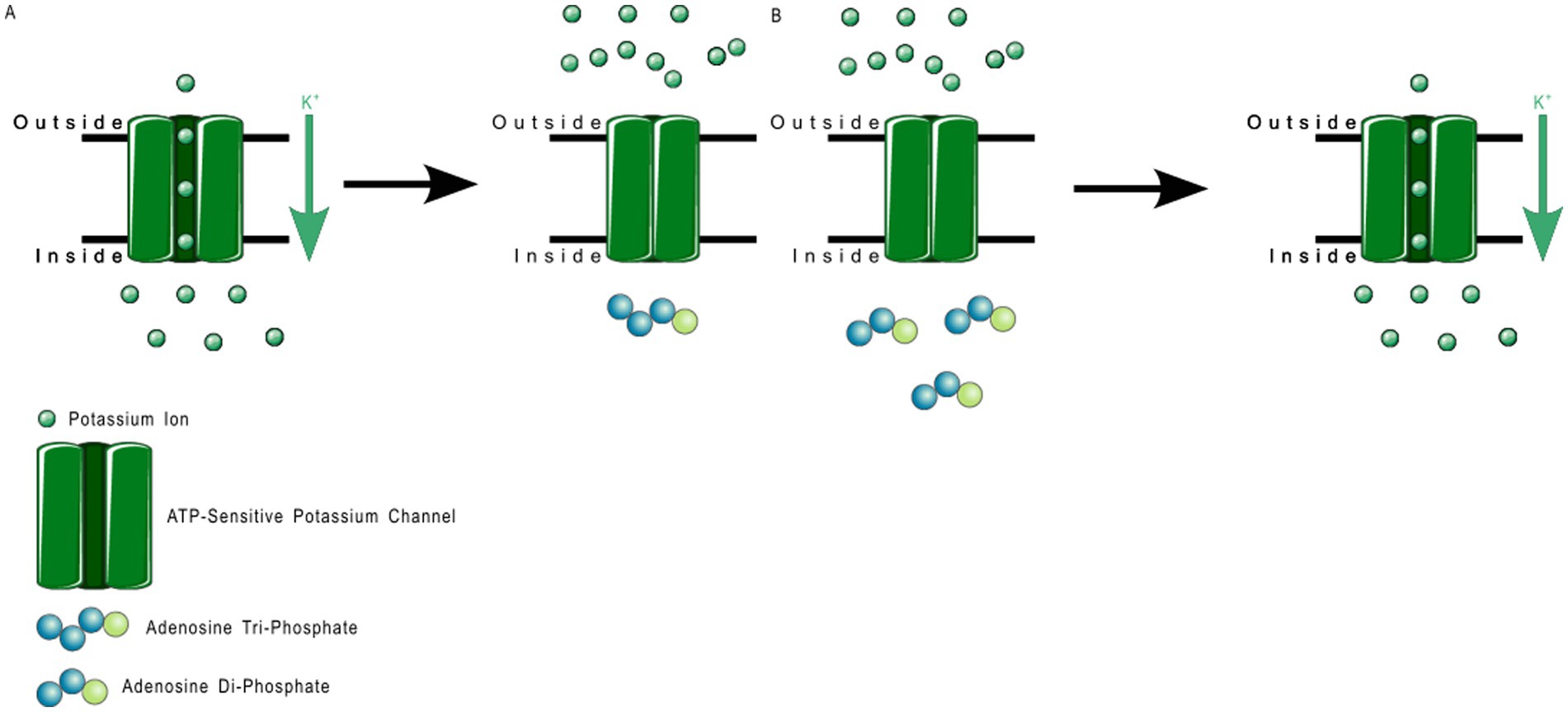

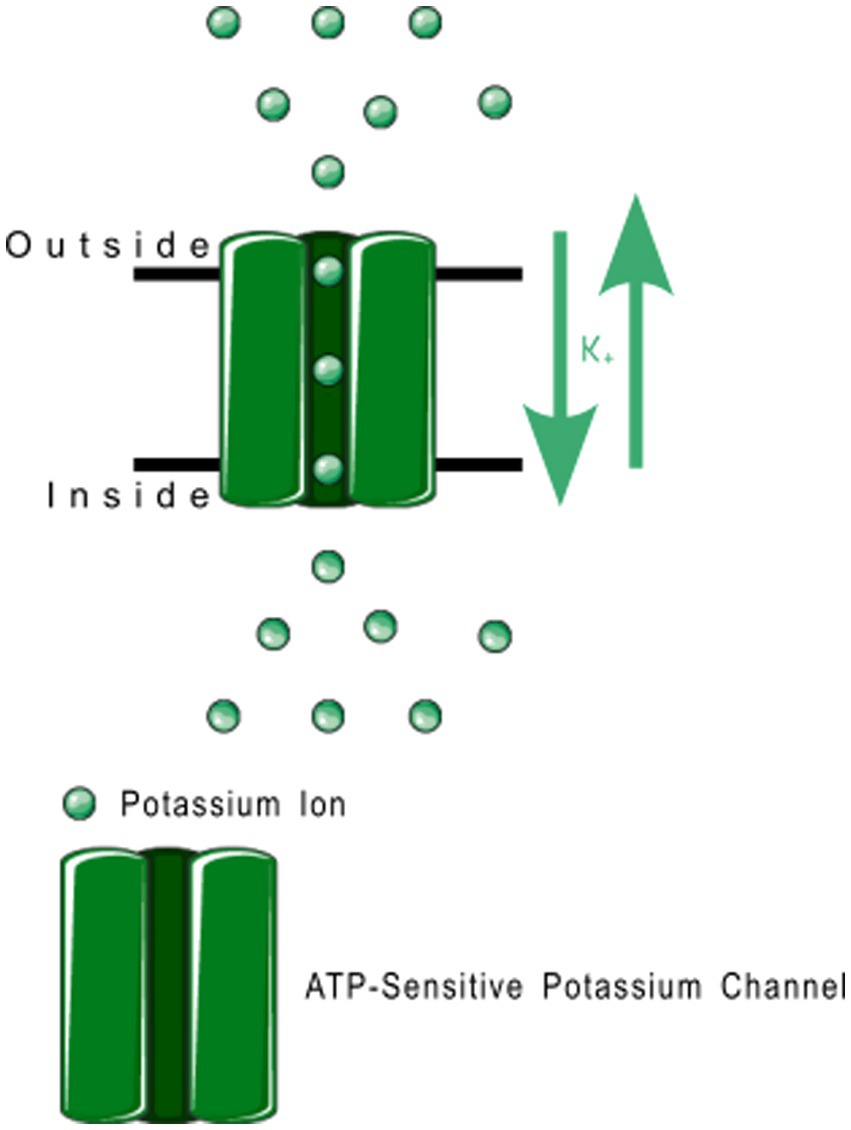

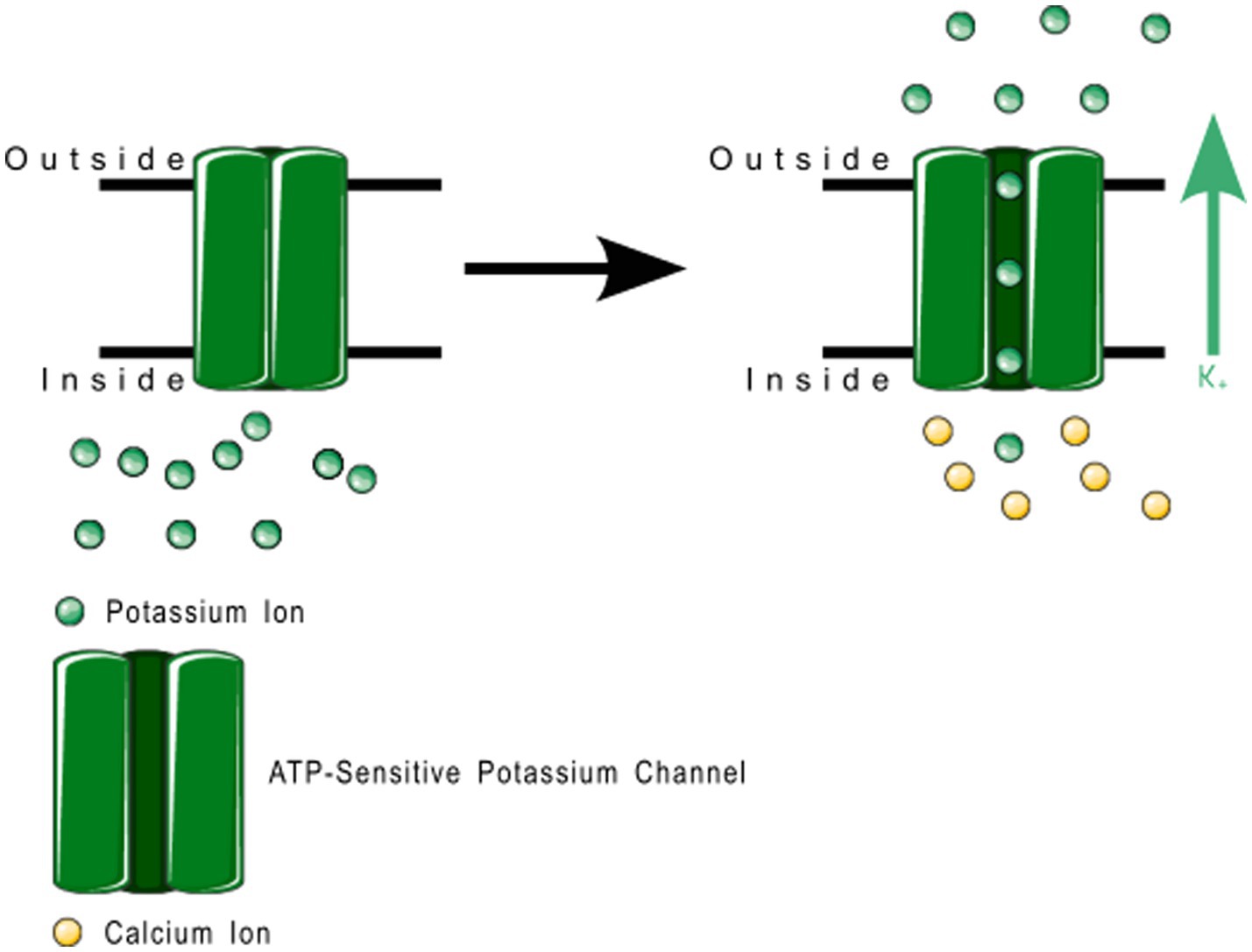

2TM channels are inward rectifying channels (KIR) responsible for controlling the rate of depolarization and repolarization. They play important roles in the functioning of various organs including the brain, heart, liver, kidney, skeletal muscle, pancreas, and retina (39, 60–66). KIR channels are usually constitutively active, but two subfamilies are activated by specific proteins or cytosolic concentrations of certain compounds (39, 60). KIR channels are described in more detail in Table 1. Figure 3 shows the normal functioning of KIR6.1, where (Figure 3B) increasing ADP concentration opens the channel but (Figure 3A) even a small concentration of ATP near the channel closes it.

Figure 3. ATP-sensitive KIR6.1 function. (A) Depicts the deactivation trigger: the presence of adenosine triphosphate near the cell interior region of the channel protein prevents potassium transport; and (B) depicts the activation trigger: the absence of adenosine diphosphate near the cell interior region of the channel protein allows potassium transport.

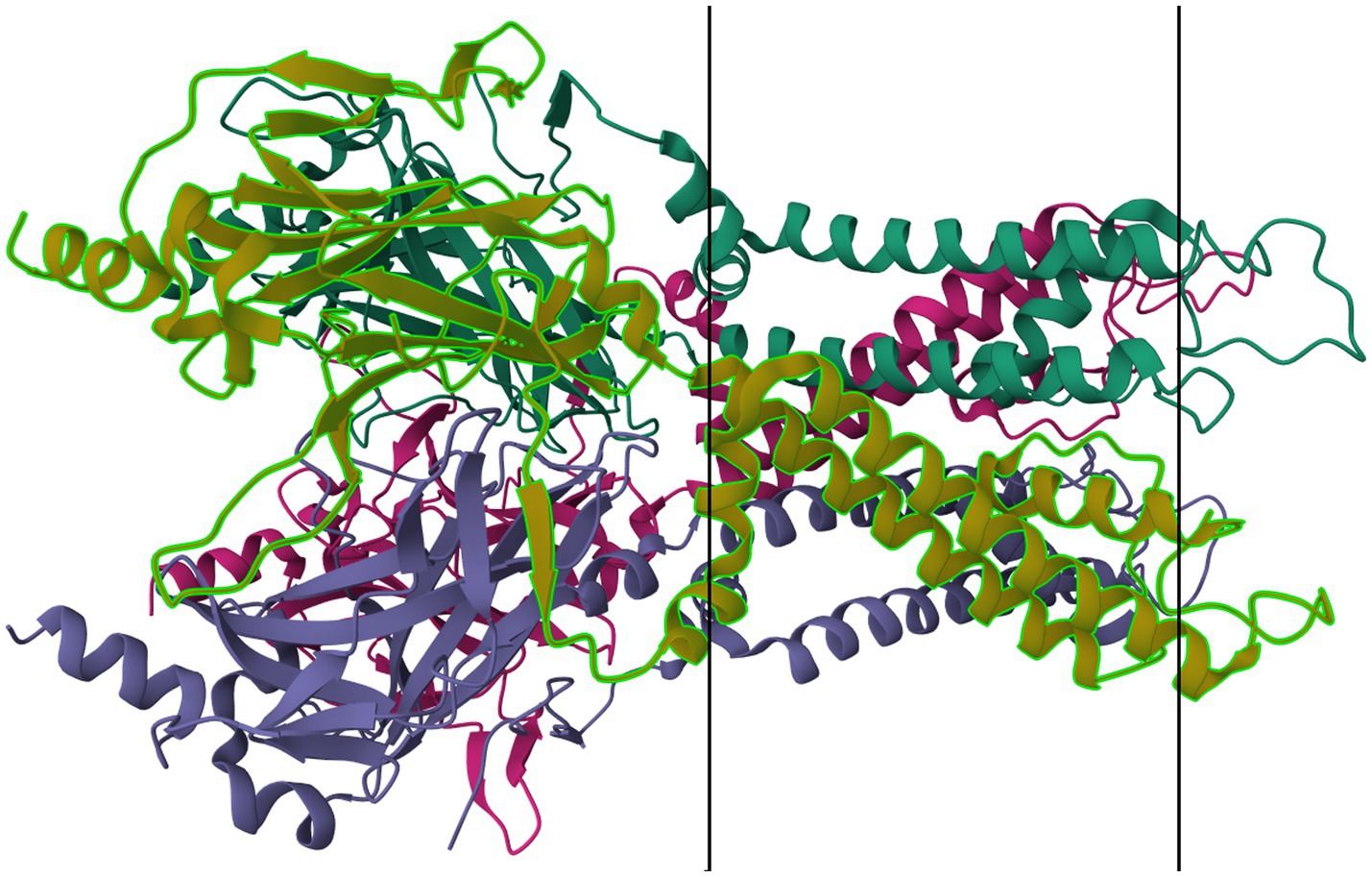

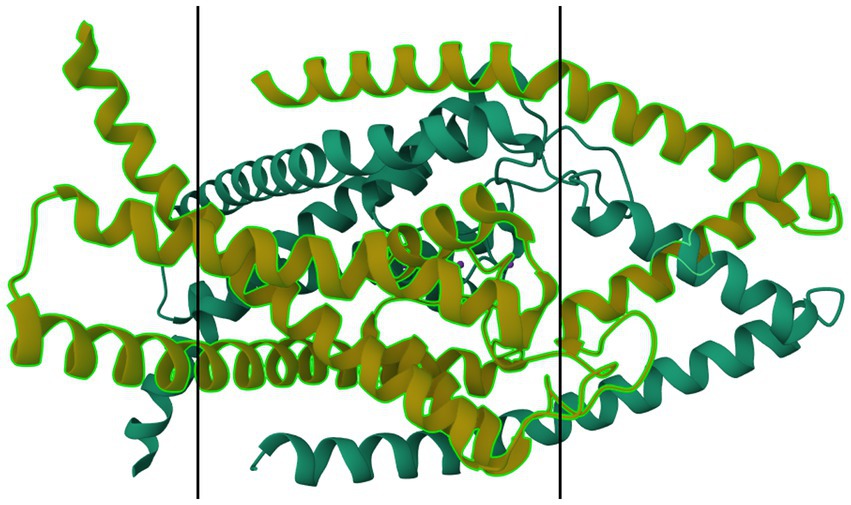

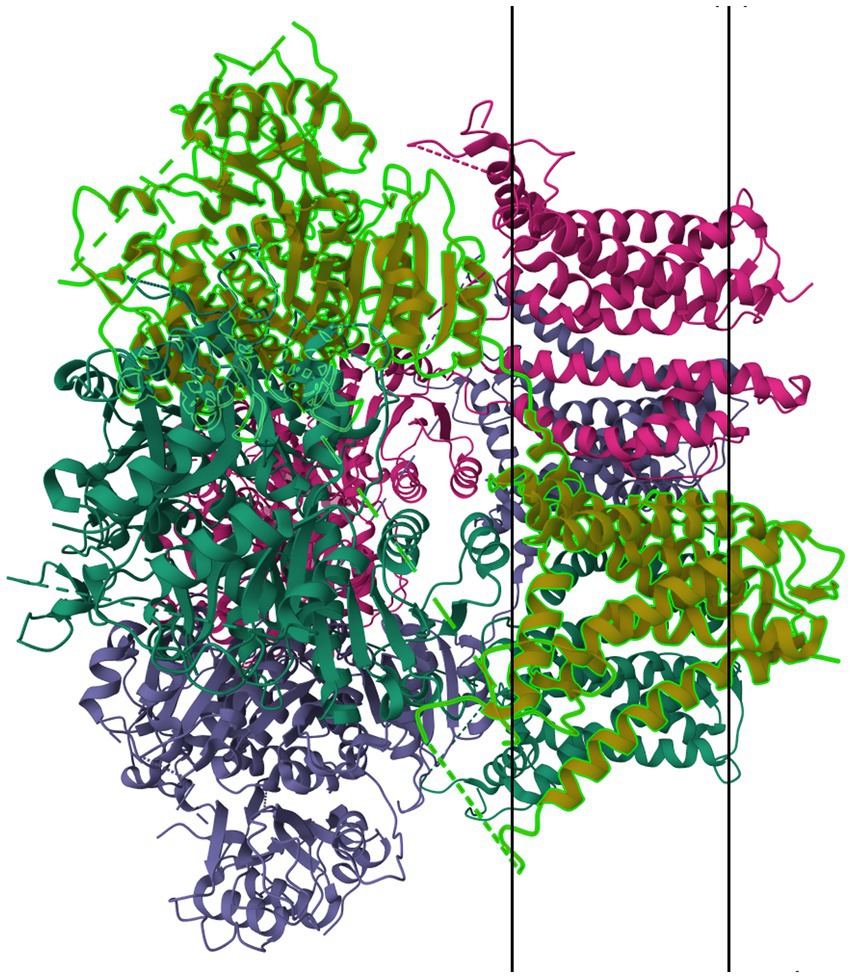

Members of the KIR6.x subfamily are ATP-sensitive, and are implicated in the pathology of several primary headache disorders, including migraine (67, 68). Kubo et al. (60) in their 2005 publication refer to two articles that describe mutations in KIR4.1 that confer resistance or susceptibility to hyperexcitability. Al-Karagholi and Hansen et al. —in their 2019 study of 16 patients—implicate KIR6 in migraine onset, using response to levcromakalim, a potent KIR6 blocker (69). Al-Karagholi et al., later in 2019, however, show that levcromakalim does not cause migraine through affecting peripheral neurons (70). Al-Karagholi and Ghanizada et al. in 2021 repeated their study on the role of levcromakalim in the central nervous system (CNS) and showed again an association with migraine (71). Christensen et al. —in their 2020 publication—describe glibenclamide-induced reversal of cephalic hypersensitivity and CGRP release by interacting with regulatory subunits of KIR6.1 (72). Clement et al. —in their 2022 (73) and 2023 (74) reviews on the subject—strongly recommend further research into KIR6. 1 and 6.2 blockers as migraine prophylactics, based on findings in mouse models. Dyhring et al. in 2023 also recognize KATP blockers as potential migraine prophylactics, recommending KIR6.1/SUR2B as a potential drug target for discovery studies (75). Figure 4 shows a ribbon model of the KIR6.2 tetramer.

Figure 4. Protein model of KIR6.2 tetramer. The molecule is oriented such that the cytosolic region falls to the left of the manuscript. The two surfaces of the cell membrane are denoted by two black bars. Image modified from Martin et al. (184) as retrieved from the RCSB Protein Data Bank.

4.1.2 4TM channels

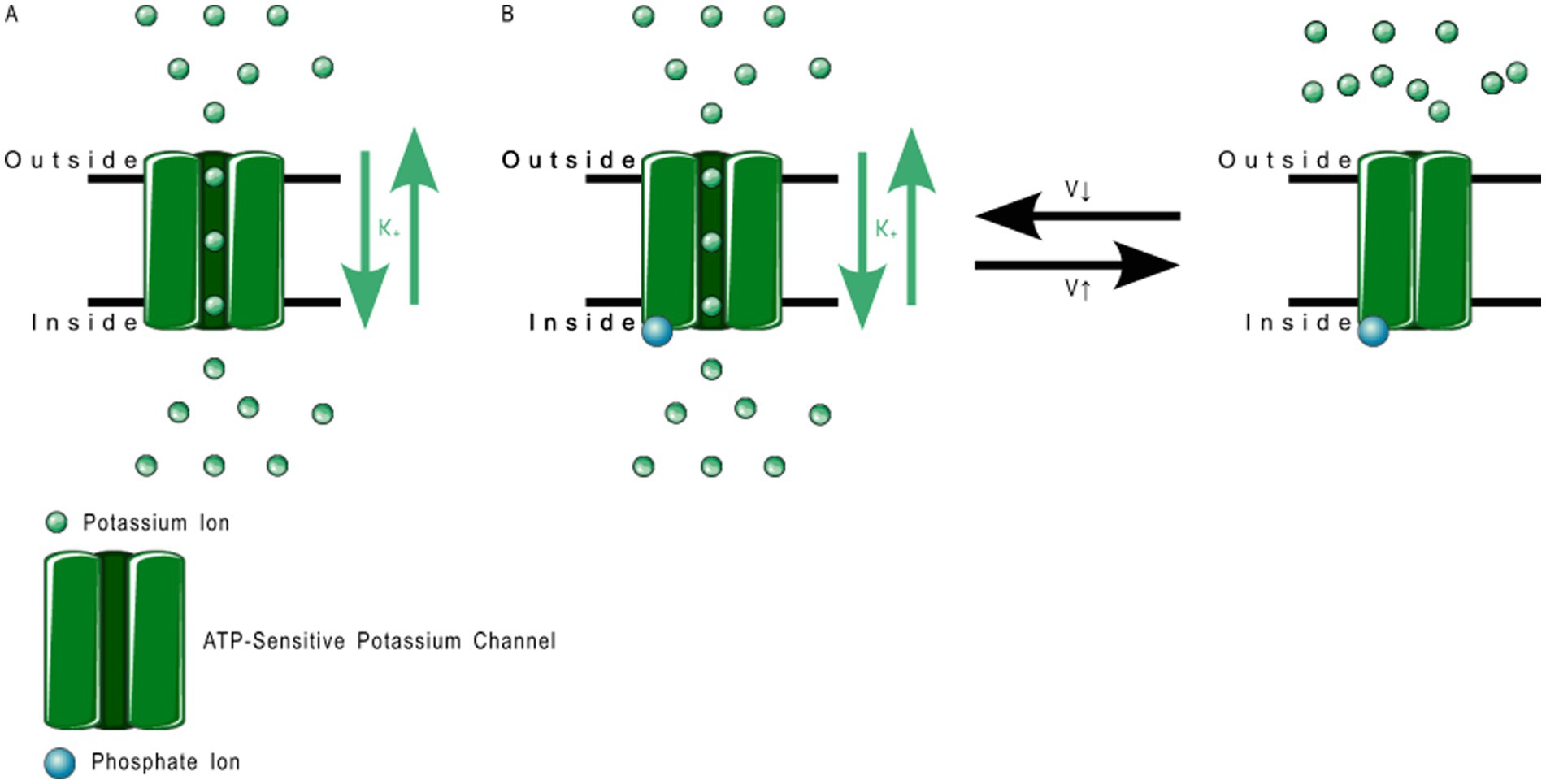

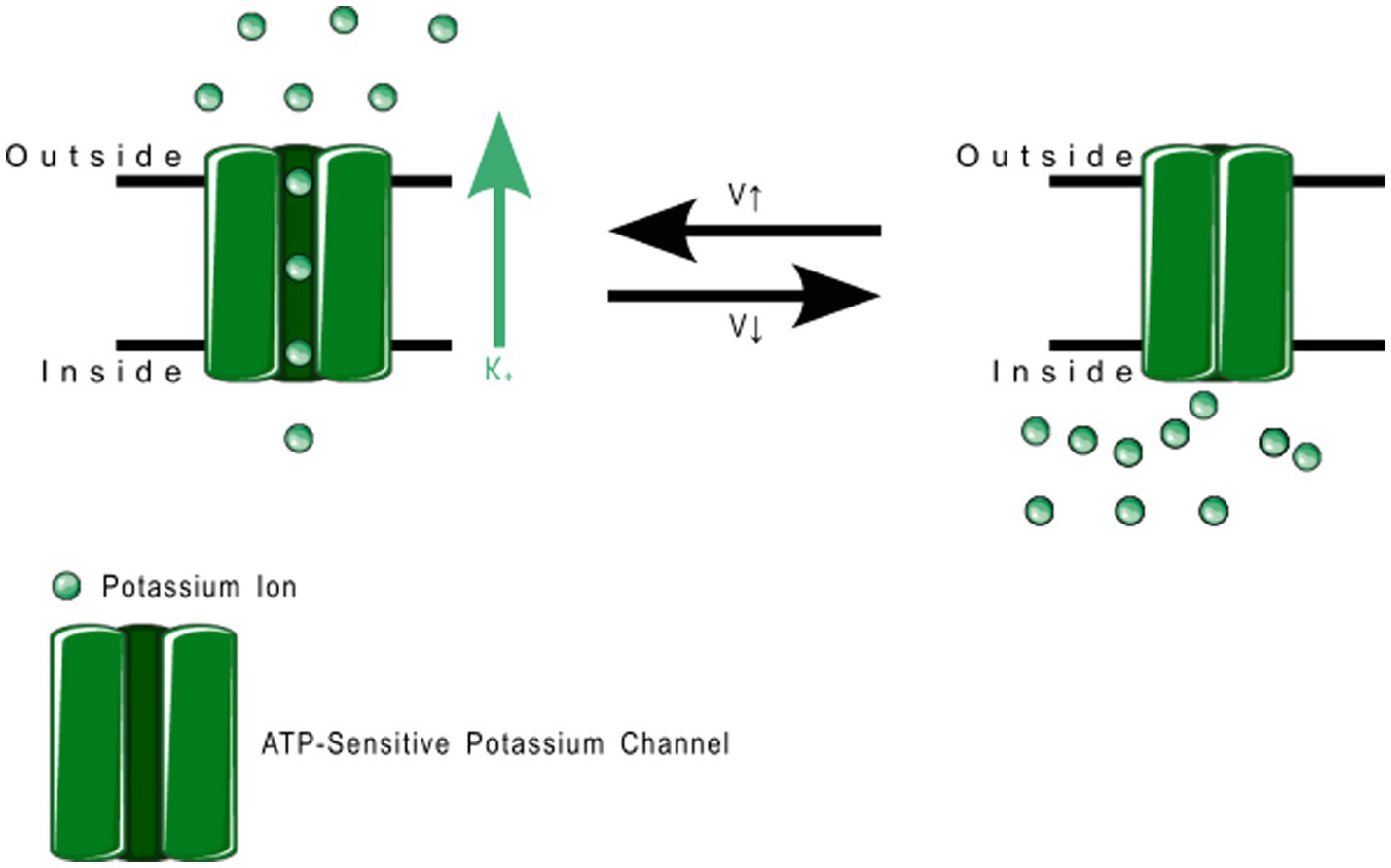

4TM channels are tandem–pore-domain channels responsible for controlling leak currents and are constitutively active at all voltages. The type family is Tandem–Pore-Domain-Containing Weak Inward-Rectifying Potassium(K) channel 1 (TWIK-1 or K2P1.1) K2P channels stabilize resting membrane potential and counteract depolarization (76–78). K2P channels are described in more detail in Table 2. Figure 5 shows the Normal Function of TWIK-Related Potassium(K) Channel 1 (TREK-1 or K2P2.1): it is an open rectifier channel that allows potassium ions to move in or out of the cytosol to maintain homeostasis. However, as shown in B, TREK-1 can be phosphorylated to turn it into a voltage-gated rectifier instead, which allows ions through dependent on the local membrane potential. Figure 6 shows the general normal function of K2P channels. TREK-2 (K2P10.1), TWIK-Related Spinal-Cord Potassium(K) Channel (TRESK or K2P18.1), TWIK-Related Acid-Sensitive Potassium (K) Channel (TASK or K2P3.1, 5.1, and 9.1) and TWIK-Related Arachidonic-Acid Sensitive Potassium(K) Channel (TRAAK or K2P4.1) are always open rectifiers. TASK family channels are blocked — physiologically — when the pH inside the cell lowers below certain thresholds. TRAAK only activates when the temperature rises above 31° C. TRESK is dependent on intracellular calcium concentration.

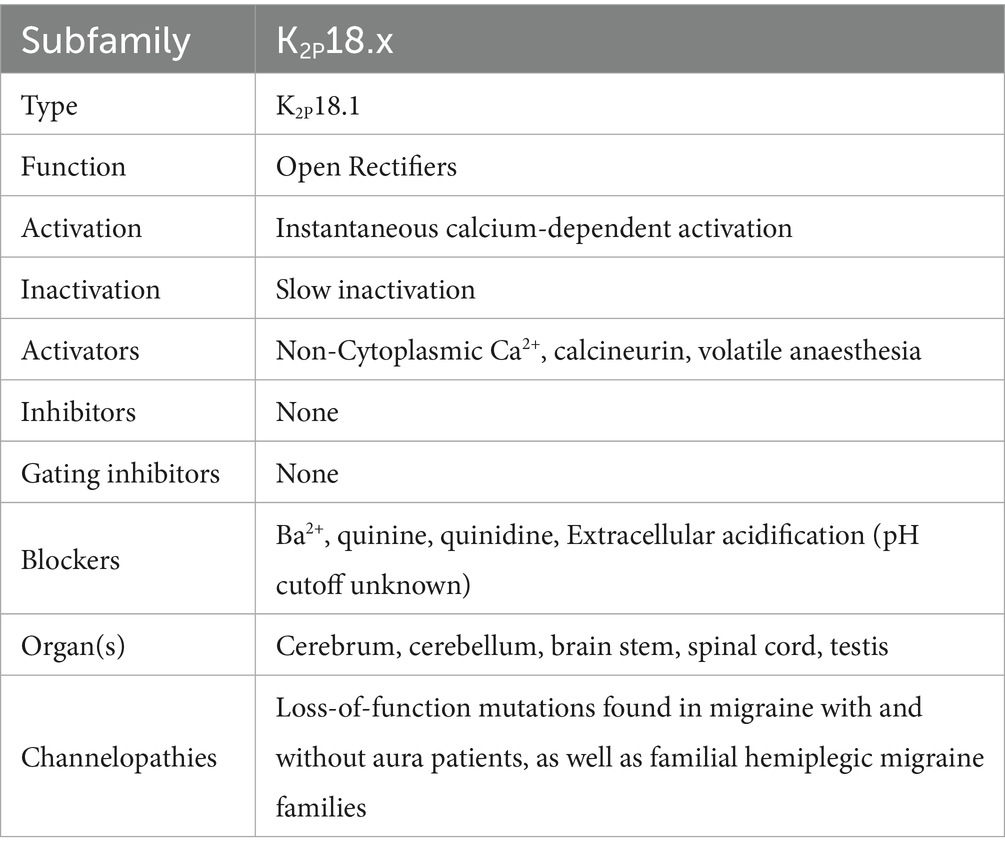

Table 2. Two-pore doman potassium channels—data taken from several sources (39, 76, 79, 80, 118, 135, 138, 142, 188–191).

Figure 5. TREK-1 function. (A) Depicts the normal function: open rectification where the ions flow according to the charge gradient, whereas (B) depicts the altered function upon phosphorylation, where change in membrane voltage switches the channel between open and closed.

Figure 6. Open rectifier function. TRESK, TASK, TREK-2, and TRAAK are all open rectifiers, which allow free flow of potassium ions both ways across the plasma membrane.

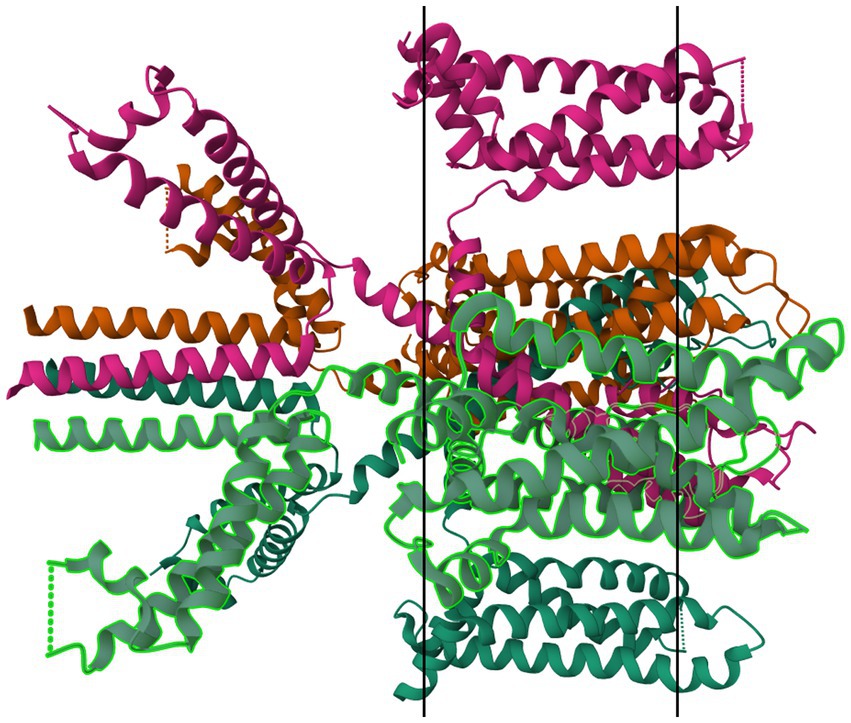

Mutations in many subfamilies of the 4TM family, especially TRESK and TREK, are strongly associated with inheritable (familial) migraine with aura. Lafrenière et al. in 2010 discovered a frameshift mutation in migraine patients that was predicted through functional characterization to cause a complete lack of TRESK function (79). Lafrenière and Rouleau—in their 2011 review—discuss the role of TRESK channels in migraine, including a potential role of TRESK loss-of-function in migraine-like side effects of cyclosporin treatment (80). Royal et al. —in their English-language publication in 2019—discuss the role of a TRESK mutation (TRESK-MT) that causes loss-of-function of TRESK channels, associating this shift with primary headache disorders including migraine (81). Royal, with a different group of authors, also published a French-language review in the same year discussing the role of TRESK-MT and other loss-of-function TRESK mutations in migraine (82). Verkest et al. in their 2021 review discuss activators and inhibitors of TRESK, TREK-1, and TREK-2 as playing “a key role in […] neuronal excitability,” recommending these channels as targets for migraine treatment. Lengyel et al. in 2020 showed that this mutation produced a fragment that also interfered with TREK-2 (83). Ávalos Prado et al. published a focused review of TREK family channels and their role in headache and migraine. The paper describes increased neuronal excitability, especially in trigeminal neurons, as a triggering factor for migraine attacks caused by mutations in TREK family channels, especially TREK-1, TREK-2, and TRAAK (Twik-Related Arachidonic Acid-sensitive K+ channels) (84). Figure 7 shows a ribbon model of the TASK-2 dimer.

Figure 7. Protein model of TASK-2 channel (K2P5.1) dimer. The molecule is oriented such that the cytosolic region falls to the left of the manuscript. The two surfaces of the cell membrane are denoted by two black bars. Image modified from Li et al. (185) as retrieved from the RCSB Protein Data Bank.

4.1.3 6TM channels

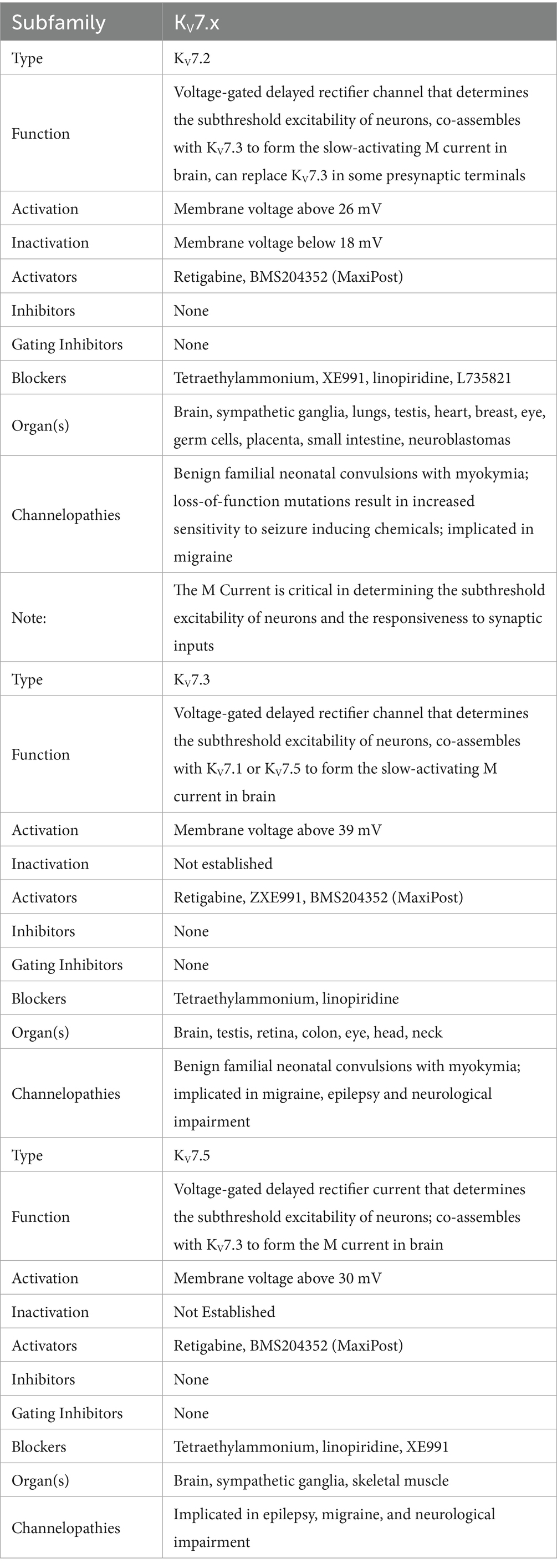

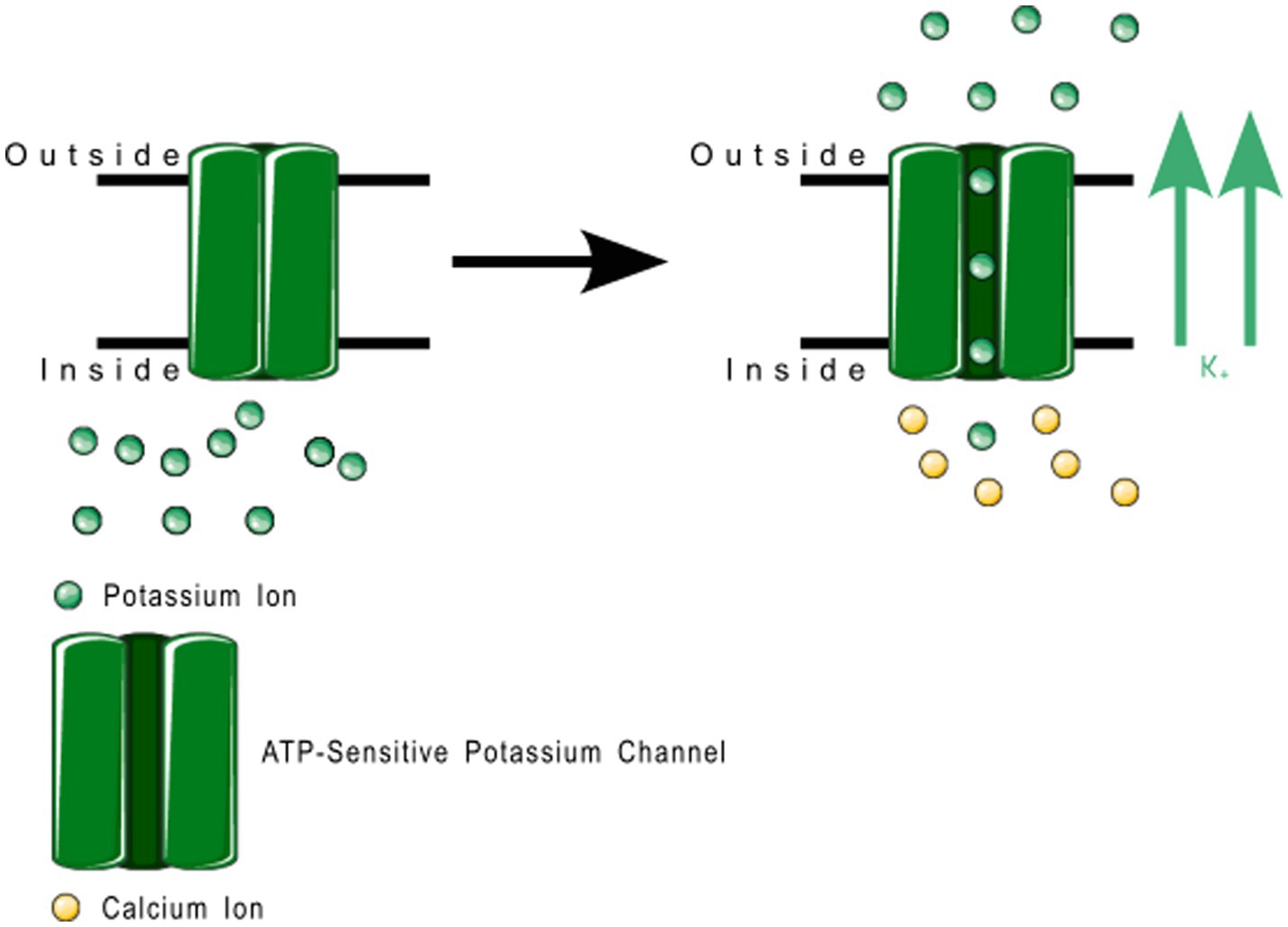

6TM channels are voltage-gated and calcium-gated potassium channels. The members of this family of channels are divided between voltage-gated channels (KV), which perform various functions, ranging from maintaining membrane potential in various organs to controlling the calcium signaling of leukocytes (85); and calcium-gated channels (KCa), which are pleiotropic and mostly involved in the modulation of depolarization in the after hyperpolarization phase. The physiological function of KCa4.x and KCa5.x are not well understood (86). KCa channels are described in more detail in Table 3, and KV in Table 4. Figure 8 shows the normal function of the large-conductance calcium-gated potassium channel (BKCa). This channel regulates membrane potential by pushing potassium ions into the extracellular space. The potassium current induced by this channel results in a large efflux of potassium ions from the cytoplasm. Figure 9 shows the normal function of the small-conductance calcium-gated potassium channel (SKCa). This channel acts in tandem with BKCa to regulate membrane potential by pushing potassium ions into the extracellular space. The potassium current induced by this channel results in a smaller efflux of ions than its ‘large’ counterpart. Figure 10 shows the normal function of the KV7.x channels; specifically, the channels formed by KV7.2, 7.3, and 7.5 channel proteins. The channels formed by these proteins are responsible for slow-activating outward currents (M currents) that moderate the membrane voltage by pushing potassium channels into the extracellular space to increase the threshold for triggering an action potential. These proteins can heteromerize with each other to form channels with a large range of threshold voltages.

Table 4. Voltage-gated potassium channels—data taken from several sources (39, 85, 92, 181, 194–199).

Figure 8. Large conductance calcium-gated potassium channel function. These channels regulate membrane depolarization by pushing potassium channels into the extracellular space.

Figure 9. Small conductance calcium-gated potassium channel function. These channels regulate membrane depolarization by pushing potassium channels into the extracellular space.

Figure 10. Voltage gated potassium channel family 7 function. KV7.2, 7.3, and 7.5 can heteromerize with each other to regulate the exact threshold voltage that opens the channel. These produce the slow-activating M current in the brain.

A large number of articles have been published implicating voltage-gated and calcium-gated potassium channels in migraine pathogenesis, especially large-conductance calcium-gated potassium channels (BKCa) and KV7. Episodic ataxias, characterized by sporadic bouts of severe discoordination, are closely related to familial hemiplegic migraine, and have been associated with voltage-gated potassium channels. Lerche, Mitrovic, and Lehmann-Horn in 1997 describe potassium channels as playing important roles in episodic ataxias (35). Ptácek in 1997 also mentions KV1.1 in association with episodic ataxias (87), as does Felix in 2000 (88) and Kullmann in 2002 (89). Lehmann-Horn and Jurkat-Rott in 1999 describe voltage-gated potassium channels KV1.1, 1.2 and 1.3 in convulsions and episodic ataxias (90). Gribkoff in 2003 already mentions the use of KV7 channel openers as analgesics, including retigabine, gabapentin, and flupirtine, and recommends further study on channel openers for migraine treatment (91). Gutman et al. — in their 2005 publication — discuss the role of KV7 in mediating the M current, a noninactivating current implicated in several neurological disorders including migraine and seizures (85). Wei et al. in their 2005 publication describe the effect of BKCa and Small-Conductance calcium-gated potassium channels (SKCa) in epilepsy and headache (92). Maljevic et al. — separately in 2008 and 2010 — discuss the role of KV7 in disorders of neuronal hyperexcitability, implicating these channels in migraine and epilepsy among other disorders (93, 94). Maljevic and Lerche — in their 2013 paper — discuss the potential use of KV7 openers in treatment of neurological syndromes, but raise concerns as to side-effects due to the abundant distribution of KV channels in various tissues (95). Citak et al. in 2022 describe the involvement of retigabine-induced KV7.x activation in reducing the CGRP release due to Transient Receptor Potential Ion Channel (TRP) activation, a phenomenon known in migraine (96). Several pharmaceutical compounds have also been patented or tested for their efficacy as migraine abortives based on their effect on voltage-gated or calcium-gated potassium channels (35, 85–91, 95–106). Figure 11 shows a ribbon model of the BKCa tetramer, and Figure 12 a ribbon model of the KV7.1 tetramer.

Figure 11. Protein model of BKCa channel (KCa1.1) tetramer. The molecule is oriented such that the cytosolic region falls to the left of the manuscript. The two surfaces of the cell membrane are denoted by two black bars. Image modified from Tao et al. (186) as retrieved from the RCSB Protein Data Bank.

Figure 12. Protein model of KV7.1 tetramer. The molecule is oriented such that the cytosolic region falls to the left of the manuscript. The two surfaces of the cell membrane are denoted by two black bars. Image modified from Ma et al. (187) as retrieved from the RCSB Protein Data Bank.

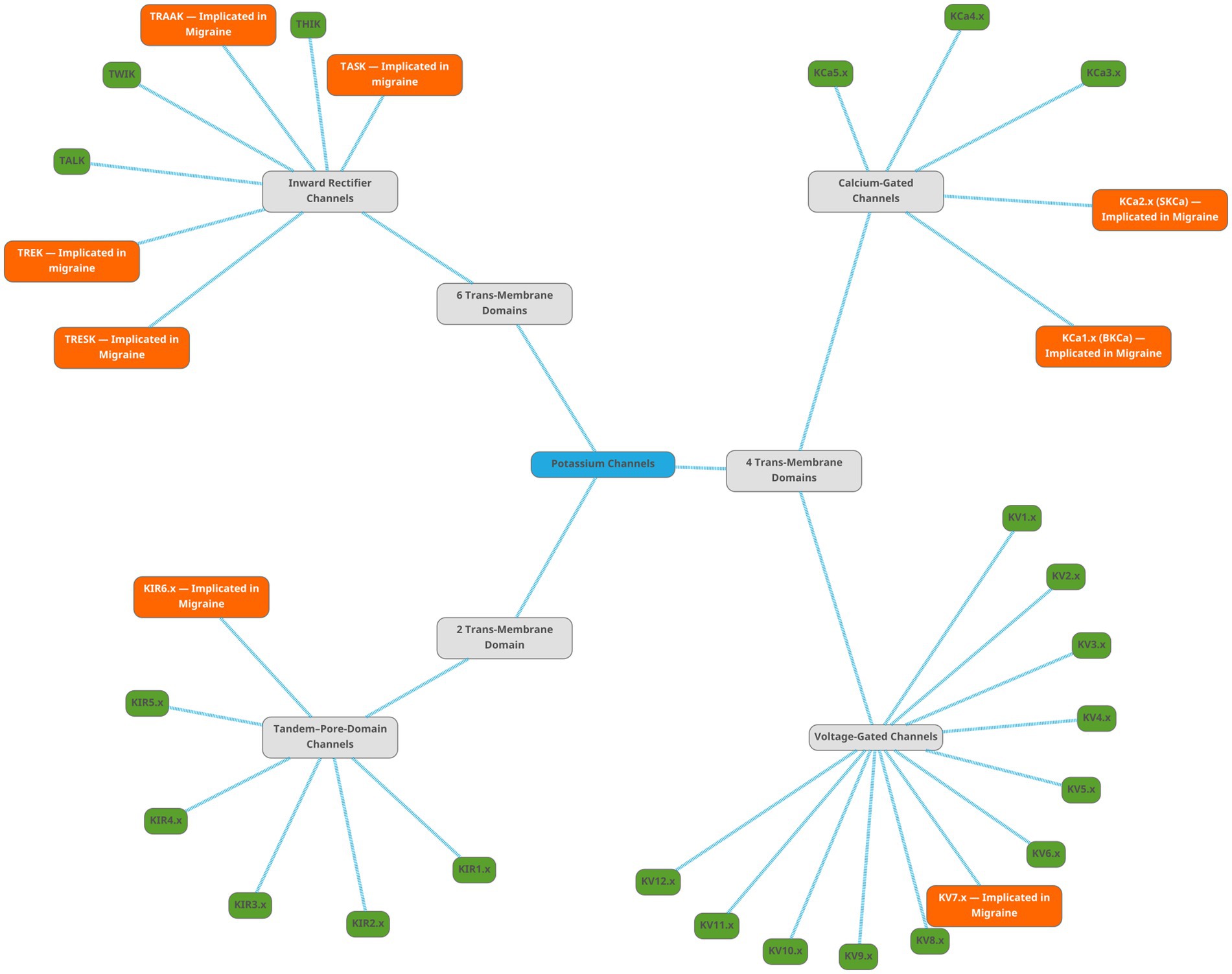

Figure 13 is a mind map of the subtypes of potassium channels. The figures representing the channel functions were created by using pictures from Servier Medical Art. Servier Medical Art by Servier is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License.1 The mind map was created using the free vector graphics editor Inkscape v. 1.3.2.2 The protein structure images were retrieved from the RSCB Protein Data Bank (107, 108) and the membrane markers added using the free image manipulation software GIMP 2.10.34.3

Figure 13. Mind map showing the subtypes of potassium channels. The root node, labelled ‘Potassium Channels’, is light-blue. There are three subtypes of potassium channels, shown as gray nodes. The families are shown as green nodes for families not implicated in migraine, and orange nodes for families implicated in migraine literature.

5 Discussion

5.1 The pathophysiology of migraine and the role of potassium channels

Migraine is a primary headache disorder that is caused by a spreading depolarization in cortical neurons (2, 5). Several inducing and exacerbating factors for cortical spreading depression are known and each individual case of migraine is likely to be a combination of several of these factors. A combination of genetic factors, environmental triggers, and physiological factors are implicated as affecting the intensity, frequency, and duration of migraine attacks, as well as the attendant symptoms and phenotypes (1, 5, 10, 15, 40, 109–114). The nociceptive symptoms of migraine are caused by signal induction in the trigeminal nerve system due to CSD waves perpetuating into TG afferents in the cortex. Ion channels and neurotransmitters in TG nerves and the nucleus caudalis are involved in the indigenous generation of pain impulses from polarization changes caused by the CSD (4, 16–18, 20–25, 27–30, 33, 34, 70, 72, 77, 78, 81, 83, 96, 102, 103, 115–121).

Cortical spreading depression has been known to induce extreme acute increase in extracellular potassium levels since 1974 (122–124). Other than the well-described role of ATP-Dependent Sodium-Potassium Pump genes in Familial Hemiplegic Migraine (10, 19, 40, 48, 52, 58, 89, 90, 110–114, 125–128), there have been several potassium channels implicated in migraine pathogenesis and progression in several papers over the last 20–25 years.

5.2 Classification of potassium channels

Potassium channels are classified into three families based on their molecular structure (39). 2 Trans-Membrane domain channels are generally responsible for rectifying neuronal polarization, 4TM channels are responsible for maintaining ion balance across the axonal membrane, and 6 TM channels are responsible for weak and strong modulatory currents in the CNS and in the heart and gut. Among the 2TM channels, KATP has been shown the highest promise as a target for migraine prophylaxis, especially in association with the SUR2B modulatory subunit, with several drugs having been described and patented that that target the same. Among the 4TM channels, mutations in the TRESK protein that interact with TREK1 and 2 have been shown to be associated with certain pedigrees of migraine.

5.3 On the role played by potassium channels in migraine

5.3.1 2TM channels

Downregulation of KIR channels in astrocytes has been linked to altered nociception and one article (129) describes a potential link to migraine. When ATP-sensitive potassium channels were targeted for treatment of asthma and angina pectoris, KATP channel openers were found to induce migraine in migraine patients. While some papers have disputed this finding with opposing findings, the headaches reported as a side effect of levcromakalim and other KATP channel openers have been used as proof that KATP channels are involved in migraine pathogenesis (40, 68–75, 106, 130–132). Glibenclamide, a KATP/SUR1A inhibitor has been tested extensively as a migraine abortive or suppressant due to its opposing effect on KATP to levcromakalim (68, 72, 133, 134), but results have so far been inconclusive. As glibenclamide targets SUR1A more than SUR1B, and as SUR1B mutations are more known in migraine pathogenesis, the latter has been suggested as a target for migraine prophylaxis (74).

5.3.2 4TM channels

Two pore-domain open rectifier channels, especially TRESK (12, 40, 41, 43, 77, 79, 80, 83, 119, 120, 135–147), TREK-1 (84, 119, 144, 145, 148) and TASK-2 (144, 145) have been shown to be involved in cortical spreading depression and migraine nociception. Overexpression of TRESK in post-synaptic regions of neurons is linked to neurotransmitter dysmodulation (137); and is suspected to result in migraine due to serotonin or GABA dysfunction. Cloxyquin, a TRESK opener, has been studied as a migraine prophylactic (141, 149, 150). A particular frameshift mutation of TRESK has been described as closely segregating with migraine phenotype in certain pedigrees of migraine (10, 12, 41, 42, 78, 80, 114, 118, 138, 139, 141, 142, 144, 146, 151–167), and has been shown to have migraine-inducing effect due to its inhibitory effect on TREK-1 and TREK-2 proteins (81–84, 143, 168–170).

5.3.3 6TM channels

Calcium-gated potassium channels such as large-conductance calcium-gated potassium channels (BKCa or MaxiK) are responsible for reducing inflammatory pain in both central and peripheral tissues (103, 104, 106, 171). Genes coding for small conductance calcium-gated potassium channels (SKCa) such as KCNN3 have been associated with Familial Hemiplegic Migraine in some pedigrees (101), alongside the more well known CANCA1A and ATP1A2. BKCa channel openers such as MaxiPost have been shown clinically to induce migraine and other primary headache symptoms (104). Openers and blockers of potassium channels have been studied for treatment of neurological conditions including migraine with multiple papers published in the last 18–20 years (75, 91, 100, 172–174). Other targets for migraine treatment have been blockers of voltage-gated potassium channels such as benzylamide derivatives and other heterocyclic compounds and KV7 openers.

5.4 Therapeutic implications

Various potassium channels are currently known to play important roles in migraine pathogenesis. Targeting these potassium channels is very likely therefore to yield actionable results toward the treatment, prevention, abortion, or amelioration of migraine attacks and pain. However, potassium is a ubiquitous ion in the human body, involved in a vast array of disparate modulatory and sensory pathways in various organs in the body, including gastrointestinal, hepatic, cardiovascular, and lymphatic systems. Therefore, any treatment for migraine that targets potassium channel proteins would have to be capable of doing so in an organ-specific manner, so as to minimize extracranial side-effects, either by targeting accessory molecules, proteins, or peptides unique to potassium channels in neuronal tissue or by targeting specific functionality of potassium channels in neuronal tissue.

Pharmaceutical ingredients that act as KV7.x openers and partial inhibitors—including retigabine (91, 96, 97, 117, 175–177), ezogabine (178), flupirtine (91, 175, 177, 179), and linopiridine (91), along with several substituted acrylamide compounds (91, 97, 172, 173, 175–177, 180)—have been and are continuing to be tested as migraine abortives or prophylactics for nigh-on two decades. Loss of function mutations in voltage-gated potassium channels are linked to reduced sensitivity to analgesics including paracetamol and opioids (181). Tricyclic antidepressants such as amitriptyline act at least partially on voltage-gated potassium channels (83, 182), and this might be the target of action of tricyclic antidepressants as migraine prophylactics. Whereas several migraine prophylactic drugs are known to act at least in part through their effect on cerebral and vascular potassium channels no specific potassium channel modulator compounds have been released as commercial products yet. However, with modern techniques and computational analysis we can hope to find suitable candidates for targeted and specific anti-migraine prophylactics either from scratch or by repurposing compounds used in treatments for other channelopathies.

6 Summary and conclusion

Migraine, despite being one of the most common primary headache disorders, still has many unknowns in both the underlying mechanisms and in the treatment. The functional mechanism behind migraine is thought to be the triggering by environmental triggers of cortical spreading depression, which results in an adverse activation of nociceptive structures in the brain and CNS. Three neurochemicals are most closely associated with migraine: serotonin, CGRP, and γ-amino butyric acid (GABA) but several other pathways including Poly-Adenylate Cyclase Activating Peptide (PACAP) and Vasoactive Intestinal Peptide (VIP) are also involved. Migraine pathogenesis is also strongly associated with the functioning of neuronal ion channels, and familial hemiplegic migraine in particular has been linked to mutations in calcium channels, sodium channels, and sodium-potassium ATPase exchanger channels. However, these same channels do not seem to have any association to non-hemiplegic familial migraine with aura or migraine without aura. Non-hemiplegic familial migraine cases are still likely to be associated with some channel or other, and to date the most promising candidates have been potassium channels, with several articles (as discussed in detail above) associating these channels with migraine phenotypes in various regions.

Potassium channels are transmembrane proteins found in various tissues ranging from cardiac tissue and gastrointestinal tissue to neurons, and are involved in autocellular signaling and regulation of membrane potential. Potassium channels have been studied as potential actors in migraine pathogenesis for several years, and the current sum of understanding of migraine pathogenesis gives more than a little import to the proper functioning of potassium channels, especially those that are involved in membrane potential maintenance and in resetting neuronal potential after firing. Dysfunctions of potassium channels have been linked to several neurological disorders including long QT syndrome, epilepsy, Barrette’s syndrome, dementia and delirium, neurodevelopmental disorders, and migraine. Whereas gene mutations involving open rectifier channels such as TRESK, TREK, and TASK have been identified for a long time in familial non-hemiplegic migraine lines, current focus on treatment has been more focused on ATP-sensitive potassium channels and calcium- or voltage-dependent potassium channels. Several existing migraine prophylactics — including analgesics, antiepileptics, and antidepressants — have been shown to act against migraine at least partially via targeting one or more potassium channels. The targeting of potassium channels, either through activation or blocking of the channel function, is a constantly updating and novel research focus with primarily clinical and case–control or cohort studies. Identification of novel agents acting on potassium channels in the meningeal and cortical regions of the brain with minimal side-effects in other organs could lead to novel treatment of currently resistant migraine phenotypes.

Potassium channels in the cortex and in cerebral vasculature clearly play an important role in modulating both the neurological and vasodilatory symptoms of migraine. The current avenues of research on potassium channels are focused on clinical presentations and identification of channel function in migraine patients, but very little consideration has been given so far to approaches from the molecular analysis side. Future investigations should aim to elucidate both the exact function of potassium channels in migraine and the reasoning behind the observed effects of blocking or opening potassium channels in the cortex or the trigeminovascular system, and the discovery or repurposing of drugs and active pharmaceutical ingredients for the treatment of migraine via their interactions with potassium channels. The use of novel analytic and exploratory tools to better classify and diagnose migraine subtypes based on channel patterns is likely to result in a more designer-care angle to treatment of migraine, moving away from the current ‘migraine cocktail’ treatment to a more specialized treatment plan with less side effects and quicker action.

6.1 Future directions

Potassium channels are ubiquitous in the body and perform various roles, sometimes resulting in apparent conflicts where openers and closers of the same channel can appear to have similar effects, due to the two molecules being segregated to different parts of the body. It is still unknown whether small molecules that target potassium channel accessory proteins such as sulfonylurea receptors and regulatory domains could be used to treat migraine phenotypes. Current research is focused predominantly on describing the effect and functioning of potassium channels and has not made inroads into analysis and prediction of potential therapeutic agents or avenues of treatment. There exists therefore a striking gap in knowledge as to the pharmacological and therapeutic potential of the knowledge being discovered about the role of ion channels in primary neurogenic pain disorders including migraine. Investigations along these lines can most efficiently be done in a computational manner, integrating genomic, epigenomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic approaches to identify viable druggable targets and novel active pharmaceutical ingredients in a synergistic manner. Exploration into this field could result not only in novel therapeutic methods for migraine and other related headache disorders but also for anesthesia and analgesia in general. As the covert phenotype of migraine is thought to be related to epilepsy and other dyspolarization disorders, research into migraine therapeutics could also result in discovery of safer or more specific anticonvulsants and antiepileptic drugs as well.

Author contributions

GM: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Data curation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Investigation. SL: Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Validation, Supervision.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fneur.2025.1622994/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

References

2. Cephalalgia. Headache classification committee of the international headache society (IHS) the international classification of headache disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia. (2018) 38:1–211. doi: 10.1177/0333102417738202

3. WippoldII, FJ, and Whealy, MA Evaluation of headache in adults - UpToDate. (2023) Available online at: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/evaluation-of-headache-in-adults (Accessed April 4, 2023).

4. Cutrer, FM. Pathophysiology of migraine. Semin Neurol. (2006) 26:171–80. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-939917

5. Charles, A. Advances in the basic and clinical science of migraine. Ann Neurol. (2009) 65:491–8. doi: 10.1002/ana.21691

6. Charles, A. Vasodilation out of the picture as a cause of migraine headache. Lancet Neurol. (2013) 12:419–20. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70051-6

7. Amin, FM, Asghar, MS, Hougaard, A, Hansen, AE, Larsen, VA, Koning, PJH, et al. Magnetic resonance angiography of intracranial and extracranial arteries in patients with spontaneous migraine without aura: a cross-section al study. Lancet Neurol. (2013) 12:454–61. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70067-X

8. Welch, KM. Drug therapy of migraine. N Engl J Med. (1993) 329:1476–83. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199311113292008

9. Sparaco, M, Feleppa, M, Lipton, R, Rapoport, A, and Bigal, M. Mitochondrial dysfunction and migraine: evidence and hypotheses. Cephalalgia. (2006) 26:361–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2005.01059.x

10. Sutherland, HG, Albury, CL, and Griffiths, LR. Advances in genetics of migraine. J Headache Pain. (2019) 20:72. doi: 10.1186/s10194-019-1017-9

11. Petschner, P, Baksa, D, Hullam, G, Torok, D, Millinghoffer, A, Deakin, JFW, et al. A replication study separates polymorphisms behind migraine with and without depression. PLoS One. (2021) 16:e0261477. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0261477

12. Raggi, A, Leonardi, M, Arruda, M, Caponnetto, V, Castaldo, M, Coppola, G, et al. Hallmarks of primary headache: part 1 – migraine. J Headache Pain. (2024) 25:189. doi: 10.1186/s10194-024-01889-x

13. Leão, AAP. Pial circulation and spreading depression of activity in the cerebral cortex. J Neurophysiol. (1944) 7:391–6.

14. Leão, AAP. Spreading depression of activity in the cerebral cortex. J Neurophysiol. (1944) 7:359–90. doi: 10.1152/jn.1944.7.6.359

15. Hadjikhani, N, Sanchez del Rio, M, Wu, O, Schwartz, D, Bakker, D, Fischl, B, et al. Mechanisms of migraine aura revealed by functional MRI in human visual cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2001) 98:4687–92. doi: 10.1073/pnas.071582498

16. Moskowitz, M, Nozaki, K, and Kraig, R. Neocortical spreading depression provokes the expression of c-fos prot ein-like immunoreactivity within trigeminal nucleus caudalis via trigeminovascular mechanisms. J Neurosci. (1993) 13:1167–77. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-03-01167.1993

17. Karatas, H, Erdener, SE, Özdemir, Y, Lule, S, Eren Koçak, E, Şen, Z, et al. Spreading depression triggers headache by activating neuronal Panx1 channels. Science. (2013) 339:1092–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1231897

18. Bolay, H, Reuter, U, Dunn, AK, Huang, Z, Boas, DA, and Moskowitz, MA. Intrinsic brain activity triggers trigeminal meningeal afferents in a migraine model. Nat Med. (2002) 8:136–42. doi: 10.1038/nm0202-136

19. Takano, T, and Nedergaard, M. Deciphering migraine. J Clin Invest. (2009) 119:16–9. doi: 10.1172/JCI38051

20. Huang, LYM. Origin of thalamically projecting somatosensory relay neurons in the immature rat. Brain Res. (1989) 495:108–14. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(89)91223-7

21. Bartsch, T, and Goadsby, PJ. Stimulation of the greater occipital nerve induces increased central excitability of dural afferent input. Brain. (2002) 125:1496–509. doi: 10.1093/brain/awf166

22. Bartsch, T, and Goadsby, PJ. Increased responses in trigeminocervical nociceptive neurons to cervical input after stimulation of the dura mater. Brain. (2003) 126:1801–13. doi: 10.1093/brain/awg190

23. Kruger, L, and Young, RF. Specialized features of the trigeminal nerve and its central connections In: M Samii and PJ Jannetta, editors. The cranial nerves: Anatomy pathology pathophysiology diagnosis treatment. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer (1981). 273–301.

24. Craig, AD, and Burton, H. Spinal and medullary lamina I projection to nucleus submedius in media l thalamus: a possible pain center. J Neurophysiol. (1981) 45:443–66. doi: 10.1152/jn.1981.45.3.443

25. Huerta, MF, Frankfurter, A, and Harting, JK. Studies of the principal sensory and spinal trigeminal nuclei of the r at: projections to the superior colliculus, inferior olive, and cerebellum. J Comp Neurol. (1983) 220:147–67. doi: 10.1002/cne.902200204

26. Shigenaga, Y, Nakatani, Z, Nishimori, T, Suemune, S, Kuroda, R, and Matano, S. The cells of origin of cat trigeminothalamic projections: especially i n the caudal medulla. Brain Res. (1983) 277:201–22. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(83)90928-9

27. Renehan, WE, Jacquin, MF, Mooney, RD, and Rhoades, RW. Structure-function relationships in rat medullary and cervical dorsal horns. II. Medullary dorsal horn cells. J Neurophysiol. (1986) 55:1187–201. doi: 10.1152/jn.1986.55.6.1187

28. Mantle-St John, LA, and Tracey, DJ. Somatosensory nuclei in the brainstem of the rat: independent projections to the thalamus and cerebellum. J Comp Neurol. (1987) 255:259–71. doi: 10.1002/cne.902550209

29. Kemplay, S, and Webster, KE. A quantitative study of the projections of the gracile, cuneate and trigeminal nuclei and of the medullary reticular formation to the thalamus in the rat. Neuroscience. (1989) 32:153–67. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(89)90115-2

30. Bernard, JF, Peschanski, M, and Besson, JM. A possible spino (trigemino)-ponto-amygdaloid pathway for pain. Neurosci Lett. (1989) 100:83–8. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(89)90664-2

31. Hayashi, H, and Tabata, T. Pulpal and cutaneous inputs to somatosensory neurons in the parabrachi al area of the cat. Brain Res. (1990) 511:177–9. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)90240-C

32. Peschanski, M, Roudier, F, Ralston, HJ, and Besson, JM. Ultrastructural analysis of the terminals of various somatosensory pathways in the ventrobasal complex of the raft thalamus: an electron-microscopic study using wheatgerm agglutinin conjugated to horseradish peroxidase as an axonal tracer. Somatosens Res. (2009) 3:75–87. doi: 10.3109/07367228509144578

33. Goadsby, PJ, Edvinsson, L, and Ekman, R. Release of vasoactive peptides in the extracerebral circulation of humans and the cat during activation of the trigeminovascular system. Ann Neurol. (1988) 23:193–6. doi: 10.1002/ana.410230214

34. Sarchielli, P, Alberti, A, Floridi, A, and Gallai, V. Levels of nerve growth factor in cerebrospinal fluid of chronic daily headache patients. Neurology. (2001) 57:132–4. doi: 10.1212/WNL.57.1.132

35. Lerche, H, Mitrovic, N, and Lehmann-Horn, F. Ion channel diseases in neurology. Fortschr Neurol Psychiatr. (1997) 65:481–8. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-996354

36. Dworakowska, B, and Dołowy, K. Ion channels-related diseases. Acta Biochim Pol. (2000) 47:685–703. doi: 10.18388/abp.2000_3989

37. Surtees, R. Inherited ion channel disorders. Eur J Pediatr. (2000) 159:S199–203. doi: 10.1007/pl00014403

38. Herrmann, A, Braathen, GJ, and Russell, MB. Episodiske ataksier Tidsskr Den Nor Legeforening. (2005) Available online at: https://tidsskriftet.no/2005/08/oversiktsartikkel/episodiske-ataksier (Accessed August 8, 2023).

39. Alexander, S, Mathie, A, and Peters, J. Guide to receptors and channels (GRAC), 5th edition. Br J Pharmacol. (2011) 164:S1–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01649_1.x

40. Ducros, A. Génétique de la migraine. Rev Neurol (Paris). (2013) 169:360–71. doi: 10.1016/j.neurol.2012.11.010

41. Yan, J, and Dussor, G. Ion channels and migraine. Headache. (2014) 54:619–39. doi: 10.1111/head.12323

42. Albury, CL, Stuart, S, Haupt, LM, and Griffiths, LR. Ion channelopathies and migraine pathogenesis. Mol Gen Genomics. (2017) 292:729–39. doi: 10.1007/s00438-017-1317-1

43. Rainero, I, Vacca, A, Govone, F, Gai, A, Pinessi, L, and Rubino, E. Migraine: genetic variants and clinical phenotypes. Curr Med Chem. (2019) 26:6207–21. doi: 10.2174/0929867325666180719120215

44. Kowalska, M, Prendecki, M, Piekut, T, Kozubski, W, and Dorszewska, J. Migraine: calcium channels and glia. Int J Mol Sci. (2021) 22:2688. doi: 10.3390/ijms22052688

45. Haan, J, Terwindt, GM, and Ferrari, MD. Genetics of migraine. Neurol Clin. (1997) 15:43–60. doi: 10.1016/S0733-8619(05)70294-2

46. Jen, JC, Kim, GW, Dudding, KA, and Baloh, RW. No mutations in CACNA1A and ATP1A2 in probands with common types of migraine. Arch Neurol. (2004) 61:926–8. doi: 10.1001/archneur.61.6.926

47. Mössner, R, Weichselbaum, A, Marziniak, M, Freitag, CM, Lesch, K, Sommer, C, et al. A highly polymorphic poly-glutamine stretch in the potassium channel KCNN3 in migraine. Headache. (2005) 45:132–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2005.05027.x

48. Dichgans, M, Herzog, J, Freilinger, T, Wilke, M, and Auer, DP. 1H-MRS alterations in the cerebellum of patients with familial hemiplegic migraine type 1. Neurology. (2005) 64:608–13. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000151855.98318.50

49. Kirchmann, M, Thomsen, LL, and Olesen, J. The CACNA1A and ATP1A2 genes are not involved in dominantly inherited migraine with aura. Am J Med Genet Part B Neuropsychiatr Genet Off Publ Int Soc Psychiatri C Genet. (2006) 141B:250–6. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30277

50. Tonelli, A, Gallanti, A, Bersano, A, Cardin, V, Ballabio, E, Airoldi, G, et al. Amino acid changes in the amino terminus of the Na, K-adenosine triphosphatase alpha-2 subunit associated to familial and sporadic hemiplegic migraine. Clin Genet. (2007) 72:517–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2007.00892.x

51. Jen, JC. Recent advances in the genetics of recurrent vertigo and vestibulopathy. Curr Opin Neurol. (2008) 21:3–7. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e3282f41ca0

52. Stam, AH, Maagdenberg, AMJM, Haan, J, Terwindt, GM, and Ferrari, MD. Genetics of migraine: an update with special attention to genetic comorbidity. Curr Opin Neurol. (2008) 21:288–93. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e3282fd171a

53. Jen, JC, and Baloh, RW. Familial episodic ataxia: a model for migrainous vertigo. Ann N Y Acad Sci. (2009) 1164:252–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2008.03723.x

54. Riant, F, Ducros, A, Ploton, C, Barbance, C, Depienne, C, and Tournier-Lasserve, E. De novo mutations in ATP1A2 and CACNA1A are frequent in early-onset sporadic hemiplegic migraine. Neurology. (2010) 75:967–72. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181f25e8f

55. Eikermann-Haerter, K, Yuzawa, I, Qin, T, Wang, Y, Baek, K, Kim, YR, et al. Enhanced subcortical spreading depression in familial hemiplegic migraine type 1 mutant mice. J Neurosci. (2011) 31:5755–63. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5346-10.2011

56. Asghar, SJ, Milesi-Hallé, A, Kaushik, C, Glasier, C, and Sharp, GB. Variable manifestations of familial hemiplegic migraine associated with reversible cerebral edema in children. Pediatr Neurol. (2012) 47:201–4. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2012.05.006

57. Domitrz, I, Kosiorek, M, Żekanowski, C, and Kamińska, A. Genetic studies of polish migraine patients: screening for causative mutations in four migraine-associated genes. Hum Genomics. (2016) 10:3. doi: 10.1186/s40246-015-0057-8

58. Hiekkala, ME, Vuola, P, Artto, V, Häppölä, P, Häppölä, E, Vepsäläinen, S, et al. The contribution of CACNA1A, ATP1A2 and SCN1A mutations in hemiplegic migraine: a clinical and genetic study in Finnish migraine families. Cephalalgia. (2018) 38:1849–63. doi: 10.1177/0333102418761041

59. Mangano, GD, Capizzi, MR, Mantuano, E, Veneziano, L, Santangelo, G, Quatrosi, G, et al. Familial hemiplegic migraine in pediatric patients: A genetic, clinica l, and follow-up study. Headache. (2023) 63:889–98. doi: 10.1111/head.14582

60. Kubo, Y, Adelman, JP, Clapham, DE, Jan, LY, Karschin, A, Kurachi, Y, et al. Nomenclature and molecular relationships of inwardly rectifying potassium channels. Pharmacol Rev. (2005) 57:509–26. doi: 10.1124/pr.57.4.11

61. Hassinen, M, Paajanen, V, and Vornanen, M. A novel inwardly rectifying K+ channel, Kir2.5, is upregulated under chronic cold stress in fish cardiac myocytes. J Exp Biol. (2008) 211:2162–71. doi: 10.1242/jeb.016121

62. Hibino, H, Inanobe, A, Furutani, K, Murakami, S, Findlay, I, and Kurachi, Y. Inwardly rectifying potassium channels: their structure, function, and physiological roles. Physiol Rev. (2010) 90:291–366. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00021.2009

63. Ryan, DP, Silva, MRD, Soong, TW, Fontaine, B, Donaldson, MR, Kung, AWC, et al. Mutations in potassium channel Kir2.6 cause susceptibility to thyrotoxic hypokalemic periodic paralysis. Cell. (2010) 140:88–98. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.12.024

64. Kumar, M, and Pattnaik, BR. Focus on Kir7.1: physiology and channelopathy. Channels. (2015) 8:488–95. doi: 10.4161/19336950.2014.959809

65. Cheng, CJ, Sung, CC, Huang, CL, and Lin, SH. Inward-rectifying potassium channelopathies: new insights into disorders of sodium and potassium homeostasis. Pediatr Nephrol. (2015) 30:373–83. doi: 10.1007/s00467-014-2764-0

66. Paninka, RM, Mazzotti, DR, Kizys, MML, Vidi, AC, Rodrigues, H, Silva, SP, et al. Whole genome and exome sequencing realignment supports the assignment of KCNJ12, KCNJ17, and KCNJ18 paralogous genes in thyrotoxic periodic paralysis locus: functional characterization of two polymorphic Kir2.6 isoforms. Mol Gen Genomics. (2016) 291:1535–44. doi: 10.1007/s00438-016-1185-0

67. Roselle Abraham, M, Jahangir, A, Alekseev, AE, and Terzic, A. Channelopathies of inwardly rectifying potassium channels. FASEB J. (1999) 13:1901–10. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.13.14.1901

68. Kokoti, L, Al-Karagholi, MAM, Elbahi, FA, Coskun, H, Ghanizada, H, Amin, FM, et al. Effect of KATP channel blocker glibenclamide on PACAP38-induced headache and hemodynamic. Cephalalgia Int J Headache. (2022) 42:846–58. doi: 10.1177/03331024221080574

69. Al-Karagholi, MAM, Hansen, JM, Guo, S, Olesen, J, and Ashina, M. Opening of ATP-sensitive potassium channels causes migraine attacks: a new target for the treatment of migraine. Brain. (2019) 142:2644–54. doi: 10.1093/brain/awz199

70. Al-Karagholi, MAM, Ghanizada, H, Hansen, JM, Aghazadeh, S, Skovgaard, LT, Olesen, J, et al. Extracranial activation of ATP-sensitive potassium channels induces vasodilation without nociceptive effects. Cephalalgia. (2019) 39:1789–97. doi: 10.1177/0333102419888490

71. Al-Karagholi, MAM, Ghanizada, H, Nielsen, CAW, Hougaard, A, and Ashina, M. Opening of ATP sensitive potassium channels causes migraine attacks with aura. Brain. (2021) 144:2322–32. doi: 10.1093/brain/awab136

72. Christensen, SL, Munro, G, Petersen, S, Shabir, A, Jansen-Olesen, I, Kristensen, DM, et al. ATP sensitive potassium (KATP) channel inhibition: A promising new drug target for migraine. Cephalalgia. (2020) 40:650–64. doi: 10.1177/0333102420925513

73. Clement, A, Guo, S, Jansen-Olesen, I, and Christensen, SL. ATP-sensitive potassium channels in migraine: translational findings and therapeutic potential. Cells. (2022) 11:2406. doi: 10.3390/cells11152406

74. Clement, A, Christensen, SL, Jansen-Olesen, I, Olesen, J, and Guo, S. The ATP sensitive potassium channel (KATP) is a novel target for migraine drug development. Front Mol Neurosci. (2023) 16:1182515. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2023.1182515

75. Dyhring, T, Jansen-Olesen, I, Christophersen, P, and Olesen, J. Pharmacological profiling of KATP channel modulators: an outlook for new treatment opportunities for migraine. Pharmaceuticals. (2023) 16:225. doi: 10.3390/ph16020225

76. Goldstein, SAN, Bayliss, DA, Kim, D, Lesage, F, Plant, LD, Rajan, S, et al. Nomenclature and molecular relationships of two-P potassium channels. Pharmacol Rev. (2005) 57:527–40. doi: 10.1124/pr.57.4.12

77. Enyedi, P, Braun, G, and Czirják, G. TRESK: the lone ranger of two-pore domain potassium channels. Mol Cell Endocrinol. (2012) 353:75–81. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2011.11.009

78. Guo, Z, Qiu, CS, Jiang, X, Zhang, J, Li, F, Liu, Q, et al. TRESK K+ channel activity regulates trigeminal nociception and headache. eNeuro. (2019) 6:ENEURO.0236. doi: 10.1523/ENEURO.0236-19.2019

79. Lafrenière, RG, Cader, MZ, Poulin, JF, Andres-Enguix, I, Simoneau, M, Gupta, N, et al. A dominant-negative mutation in the TRESK potassium channel is linked to familial migraine with aura. Nat Med. (2010) 16:1157–60. doi: 10.1038/nm.2216

80. Lafrenière, RG, and Rouleau, GA. Migraine: role of the TRESK two-pore potassium channel. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. (2011) 43:1533–6. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2011.08.002

81. Royal, P, Andres-Bilbe, A, Ávalos Prado, P, Verkest, C, Wdziekonski, B, Schaub, S, et al. Migraine-associated TRESK mutations increase neuronal excitability through alternative translation initiation and inhibition of TREK. Neuron. (2019) 101:232–245.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2018.11.039

82. Royal, P, Ávalos Prado, P, Wdziekonski, B, and Sandoz, G. Two-pore-domain potassium channels and molecular mechanisms underlying migraine. Biol Aujourdhui. (2019) 213:51–7. doi: 10.1051/jbio/2019020

83. Verkest, C, Häfner, S, Ávalos Prado, P, Baron, A, and Sandoz, G. Migraine and two-pore-domain potassium channels. Neuroscientist. (2021) 27:268–84. doi: 10.1177/1073858420940949

84. Ávalos Prado, P, Chassot, AA, Landra-Willm, A, and Sandoz, G. Regulation of two-pore-domain potassium TREK channels and their involvement in pain perception and migraine. Neurosci Lett. (2022) 773:136494. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2022.136494

85. Gutman, GA, Chandy, KG, Grissmer, S, Lazdunski, M, Mckinnon, D, Pardo, LA, et al. International Union of Pharmacology. LIII. Nomenclature and molecular relationships of voltage-gated potassium channels. Pharmacol Rev. (2005) 57:473–508. doi: 10.1124/pr.57.4.10

86. Wei, AD, Gutman, GA, Aldrich, R, Chandy, KG, Grissmer, S, Wulff, H, et al. LII. Nomenclature and molecular relationships of calcium-activated potassium channels. Pharmacol Rev. (2005) 57:463–72. doi: 10.1124/pr.57.4.9

87. Ptácek, LJ. Channelopathies: ion channel disorders of muscle as a paradigm for paroxysmal disorders of the nervous system. Neuromuscul Disord. (1997) 7:250–5. doi: 10.1016/s0960-8966(97)00046-1

88. Felix, R. Channelopathies: ion channel defects linked to heritable clinical disorders. J Med Genet. (2000) 37:729–40. doi: 10.1136/jmg.37.10.729

89. Kullmann, DM. The neuronal channelopathies. Brain. (2002) 125:1177–95. doi: 10.1093/brain/awf130

90. Lehmann-Horn, F, and Jurkat-Rott, K. Voltage-gated ion channels and hereditary disease. Physiol Rev. (1999) 79:1317–72. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.4.1317

91. Gribkoff, VK. The therapeutic potential of neuronal KCNQ channel modulators. Expert Opin Ther Targets. (2003) 7:737–48. doi: 10.1517/14728222.7.6.737

92. Wei, AD, Wakenight, P, Zwingman, TA, Bard, AM, Sahai, N, Willemsen, MH, et al. Human KCNQ5 de novo mutations underlie epilepsy and intellectual disability. J Neurophysiol. (2022) 128:40–61. doi: 10.1152/jn.00509.2021

93. Maljevic, S, Wuttke, TV, and Lerche, H. Nervous system KV7 disorders: breakdown of a subthreshold brake. J Physiol. (2008) 586:1791–801. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.150656

94. Maljevic, S, Wuttke, TV, Seebohm, G, and Lerche, H. KV7 channelopathies. Pflugers Arch. (2010) 460:277–88. doi: 10.1007/s00424-010-0831-3

95. Maljevic, S, and Lerche, H. Potassium channels: a review of broadening therapeutic possibilities for neurological diseases. J Neurol. (2013) 260:2201–11. doi: 10.1007/s00415-012-6727-8

96. Citak, A, Kilinc, E, Torun, IE, Ankarali, S, Dagistan, Y, and Yoldas, H. The effects of certain TRP channels and voltage-gated KCNQ/Kv7 channel opener retigabine on calcitonin gene-related peptide release in the trigeminovascular system. Cephalalgia. (2022) 42:1375–86. doi: 10.1177/03331024221114773

97. Wu, YJ, and Dworetzky, S. Recent developments on KCNQ potassium channel openers. Curr Med Chem. (2005) 12:453–60. doi: 10.2174/0929867053363045

98. Curtain, R, Sundholm, J, Lea, R, Ovcaric, M, MacMillan, J, and Griffiths, L. Association analysis of a highly polymorphic CAG repeat in the human potassium channel gene KCNN3 and migraine susceptibility. BMC Med Genet. (2005) 6:32. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-6-32

99. Filosa, JA, Bonev, AD, Straub, SV, Meredith, AL, Wilkerson, MK, Aldrich, RW, et al. Local potassium signaling couples neuronal activity to vasodilation in the brain. Nat Neurosci. (2006) 9:1397–403. doi: 10.1038/nn1779

100. Judge, SIV, Smith, PJ, Stewart, PE, and Bever, CT. Potassium channel blockers and openers as CNS neurologic therapeutic a gents. Recent Pat CNS Drug Discov. (2007) 2:200–28. doi: 10.2174/157488907782411765

101. Cox, HC, Lea, RA, Bellis, C, Carless, M, Dyer, T, Blangero, J, et al. Variants in the human potassium channel gene (KCNN3) are associated with migraine in a high risk genetic isolate. J Headache Pain. (2011) 12:603–8. doi: 10.1007/s10194-011-0392-7

102. Samengo, I, Currò, D, Barrese, V, Taglialatela, M, and Martire, M. Large conductance calcium-activated potassium channels: their expression and modulation of glutamate release from nerve terminals isolated f rom rat trigeminal caudal nucleus and cerebral cortex. Neurochem Res. (2014) 39:901–10. doi: 10.1007/s11064-014-1287-1

103. Al-Karagholi, MAM, Gram, C, Nielsen, CAW, and Ashina, M. Targeting BKCa channels in migraine: rationale and perspectives. CNS Drugs. (2020) 34:325–35. doi: 10.1007/s40263-020-00706-8

104. Al-Karagholi, MAM, Ghanizada, H, Waldorff Nielsen, CA, Skandarioon, C, Snellman, J, Lopez-Lopez, C, et al. Opening of BKCa channels causes migraine attacks: a new downstream target for the treatment of migraine. Pain. (2021) 162:2512–20. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000002238

105. Aiba, I, and Noebels, JL. Kcnq2/Kv7.2 controls the threshold and bi-hemispheric symmetry of cortical spreading depolarization. Brain. (2021) 144:2863–78. doi: 10.1093/brain/awab141

106. Al-Karagholi, MAM. Involvement of potassium channel signalling in migraine pathophysiology. Pharmaceuticals. (2023) 16:438. doi: 10.3390/ph16030438

107. Berman, HM, Westbrook, J, Feng, Z, Gilliland, G, Bhat, TN, Weissig, H, et al. The protein data bank. Nucleic Acids Res. (2000) 28:235–42. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.235

108. Berman, H, Henrick, K, and Nakamura, H. Announcing the worldwide protein data Bank. Nat Struct Mol Biol. (2003) 10:980–18. doi: 10.1038/nsb1203-980

109. Haan, J, Kors, EE, Vanmolkot, KRJ, Maagdenberg, AMJM, Frants, RR, and Ferrari, MD. Migraine genetics: an update. Curr Pain Headache Rep. (2005) 9:213–20. doi: 10.1007/s11916-005-0065-9

111. Ducros, A. Genetics of migraine. Rev Neurol. (2021) 177:801–8. doi: 10.1016/j.neurol.2021.06.002

112. Freilinger, T, and Dichgans, M. Genetik der Migräne. Nervenarzt. (2006) 77:1186, 1188–95. doi: 10.1007/s00115-006-2134-7

113. Vries, B, Frants, RR, Ferrari, MD, and Maagdenberg, AMJM. Molecular genetics of migraine. Hum Genet. (2009) 126:115–32. doi: 10.1007/s00439-009-0684-z

114. Silberstein, SD, and Dodick, DW. Migraine genetics: part II. Headache. (2013) 53:1218–29. doi: 10.1111/head.12169

115. Jacquin, MF, Chiaia, NL, Haring, JH, and Rhoades, RW. Intersubnuclear connections within the rat trigeminal brainstem complex. Somatosens Mot Res. (1990) 7:399–420. doi: 10.3109/08990229009144716

116. Ploug, K, Amrutkar, D, Baun, M, Ramachandran, R, Iversen, A, Lund, T, et al. K(ATP) channel openers in the trigeminovascular system. Cephalalgia. (2012) 32:55–65. doi: 10.1177/0333102411430266

117. Ooi, L, Gigout, S, Pettinger, L, and Gamper, N. Triple cysteine module within M-type K+ channels mediates reciprocal channel modulation by nitric oxide and reactive oxygen species. J Neurosci. (2013) 33:6041–6. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4275-12.2013

118. Liu, P, Xiao, Z, Ren, F, Guo, Z, Chen, Z, Zhao, H, et al. Functional analysis of a migraine-associated TRESK K+ channel mutation. J Neurosci. (2013) 33:12810–24. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1237-13.2013

119. Lengyel, M, Czirják, G, Jacobson, DA, and Enyedi, P. TRESK and TREK-2 two-pore-domain potassium channel subunits form functional heterodimers in primary somatosensory neurons. J Biol Chem. (2020) 295:12408–25. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA120.014125

120. Lengyel, M, Hajdu, D, Dobolyi, A, Rosta, J, Czirják, G, Dux, M, et al. TRESK background potassium channel modifies the TRPV1-mediated nociceptor excitability in sensory neurons. Cephalalgia. (2021) 41:827–38. doi: 10.1177/0333102421989261

121. Al-Karagholi, MA, Hakbilen, CC, and Ashina, M. The role of high-conductance calcium-activated potassium channel in headache and migraine pathophysiology. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. (2022) 131:347–54. doi: 10.1111/bcpt.13787

122. Mayevsky, A, Zeuthen, T, and Chance, B. Measurements of extracellular potassium, ECoG and pyridine nucleotide levels during cortical spreading depression in rats. Brain Res. (1974) 76:347–9. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(74)90467-3

123. Dreier, JP, and Reiffurth, C. The stroke-Migraine depolarization continuum. Neuron. (2015) 86:902–22. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.04.004

124. Oka, F, Lee, JH, Yuzawa, I, Li, M, Bornstaedt, D, Eikermann-Haerter, K, et al. CADASIL mutations sensitize the brain to ischemia via spreading depola rizations and abnormal extracellular potassium homeostasis. J Clin Invest. (2022) 132:e149759. doi: 10.1172/JCI149759

125. Tepper, SJ, Rapoport, A, and Sheftell, F. The pathophysiology of migraine. Neurologist. (2001) 7:279–86. doi: 10.1097/00127893-200109000-00002

126. Wessman, M, Kaunisto, MA, Kallela, M, and Palotie, A. The molecular genetics of migraine. Ann Med. (2004) 36:462–73. doi: 10.1080/07853890410018060

127. Maagdenberg, AMJM, Haan, J, Terwindt, GM, and Ferrari, MD. Migraine: gene mutations and functional consequences. Curr Opin Neurol. (2007) 20:299–305. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e3281338d1f

128. Cuenca-León, E, Corominas, R, Fernàndez-Castillo, N, Volpini, V, Toro, M, Roig, M, et al. Genetic analysis of 27 Spanish patients with hemiplegic migraine, basi Lar-type migraine and childhood periodic syndromes. Cephalalgia. (2008) 28:1039–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2008.01645.x

129. Wu, W, Yao, H, Zhao, HW, Wang, J, and Haddad, GG. Down-regulation of inwardly rectifying K+ currents in astrocytes deriv ed from patients with Monge’s disease. Neuroscience. (2018) 374:70–9. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2018.01.016

130. Al-Karagholi, MAM, Hansen, JM, Severinsen, J, Jansen-Olesen, I, and Ashina, M. The KATP channel in migraine pathophysiology: a novel therapeutic target for migraine. J Headache Pain. (2017) 18:90. doi: 10.1186/s10194-017-0800-8

131. Al-Karagholi, MAM, Ghanizada, H, Kokoti, L, Paulsen, JS, Hansen, JM, and Ashina, M. Effect of KATP channel blocker glibenclamide on levcromakalim-induced headache. Cephalalgia. (2020) 40:1045–54. doi: 10.1177/0333102420949863

132. Al-Khazali, HM, Deligianni, CI, Pellesi, L, Al-Karagholi, MAM, Ashina, H, Chaudhry, BA, et al. Induction of cluster headache after opening of adenosine triphosphate-sensitive potassium channels: a randomized clinical trial. Pain. (2024) 165:1289–303. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000003130

133. Gozalov, A, Jansen-Olesen, I, Klaerke, D, and Olesen, J. Role of K ATP channels in cephalic vasodilatation induced by calcitonin gene-related peptide, nitric oxide, and transcranial electrical stimulation in the rat. Headache. (2008) 48:1202–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2008.01205.x

134. Syed, AU, Koide, M, Brayden, JE, and Wellman, GC. Tonic regulation of middle meningeal artery diameter by ATP-sensitive potassium channels. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. (2019) 39:670–9. doi: 10.1177/0271678X17749392

135. Wood, H. Familial migraine with aura is associated with a mutation in the TRESK potassium channel. Nat Rev Neurol. (2010) 6:643–3. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2010.166

136. Andres-Enguix, I, Shang, L, Stansfeld, PJ, Morahan, JM, Sansom, MSP, Lafrenière, RG, et al. Functional analysis of missense variants in the TRESK (KCNK18) K + channel. Sci Rep. (2012) 2:237. doi: 10.1038/srep00237

137. Sehgal, A, Hassan, M, and Rashid, S. Pharmacoinformatics elucidation of potential drug targets against migraine to target ion channel protein KCNK18. Drug Des Devel Ther. (2014) 8:571. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S63096

138. Rainero, I, Rubino, E, Gallone, S, Zavar ise, P, Carli, D, Boschi, S, et al. KCNK18 (TRESK) genetic variants in Italian patients with migraine. Headache. (2014) 54:1515–22. doi: 10.1111/head.12439

139. Tsantoulas, C. Emerging potassium channel targets for the treatment of pain. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. (2015) 9:147–54. doi: 10.1097/SPC.0000000000000131

140. Hertelendy, P, Varga, DP, Menyhárt, Á, Bari, F, and Farkas, E. Susceptibility of the cerebral cortex to spreading depolarization in neurological disease states: the impact of aging. Neurochem Int. (2019) 127:125–36. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2018.10.010

141. Pettingill, P, Weir, GA, Wei, T, Wu, Y, Flower, G, Lalic, T, et al. A causal role for TRESK loss of function in migraine mechanisms. Brain. (2019) 142:3852–67. doi: 10.1093/brain/awz342

142. Imbrici, P, Nematian-Ardestani, E, Hasan, S, Pessia, M, Tucker, SJ, and D’Adamo, MC. Altered functional properties of a missense variant in the TRESK K+ channel (KCNK18) associated with migraine and intellectual disability. Pflugers Arch. (2020) 472:923–30. doi: 10.1007/s00424-020-02382-5

143. Andres-Bilbe, A, Castellanos, A, Pujol-Coma, A, Callejo, G, Comes, N, and Gasull, X. The background K+ channel TRESK in sensory physiology and pain. Int J Mol Sci. (2020) 21:5206. doi: 10.3390/ijms21155206

144. Mathie, A, Veale, EL, Cunningham, KP, Holden, RG, and Wright, PD. Two-pore domain potassium channels as drug targets: anesthesia and beyond. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. (2021) 61:401–20. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-030920-111536

145. McCoull, D, Ococks, E, Large, JM, Tickle, DC, Mathie, A, Jerman, J, et al. A “target class” screen to identify activators of two-pore domain potassium (K2P) channels. SLAS Discov. (2021) 26:428–38. doi: 10.1177/2472555220976126

146. Grangeon, L, Lange, KS, Waliszewska-Prosół, M, Onan, D, Marschollek, K, Wiels, W, et al. Genetics of migraine: where are we now? J Headache Pain. (2023) 24:12. doi: 10.1186/s10194-023-01547-8

147. Al-Hassany, L, Boucherie, DM, Creeney, H, van Drie, RWA, Farham, F, Favaretto, S, et al. Future targets for migraine treatment beyond CGRP. J Headache Pain. (2023) 24:76. doi: 10.1186/s10194-023-01567-4

148. Pope, L, and Minor, DL. The Polysite pharmacology of TREK K2P channels. Adv Exp Med Biol. (2021) 1349:51–65. doi: 10.1007/978-981-16-4254-8_4

149. Wright, PD, Weir, G, Cartland, J, Tickle, D, Kettleborough, C, Cader, MZ, et al. Cloxyquin (5-chloroquinolin-8-ol) is an activator of the two-pore domain potassium channel TRESK. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. (2013) 441:463–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.10.090

150. Lengyel, M, Dobolyi, A, Czirják, G, and Enyedi, P. Selective and state-dependent activation of TRESK (K2P 18.1) background potassium channel by cloxyquin. Br J Pharmacol. (2017) 174:2102–13. doi: 10.1111/bph.13821

151. Marmura, MJ, and Silberstein, SD. Current understanding and treatment of headache disorders: five new things. Neurology. (2011) 76:S31–5. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31820c95cc

152. Maher, BH, and Griffiths, LR. Identification of molecular genetic factors that influence migraine. Mol Gen Genomics. (2011) 285:433–46. doi: 10.1007/s00438-011-0622-3

153. Menon, S, and Griffiths, L. Emerging genomic biomarkers in migraine. Future Neurol. (2013) 8:87–101. doi: 10.2217/fnl.12.80

154. Cutrer, FM, and Smith, JH. Human studies in the pathophysiology of migraine: genetics and functional neuroimaging. Headache. (2013) 53:401–12. doi: 10.1111/head.12024

155. Guo, Z, and Cao, YQ. Over-expression of TRESK K(+) channels reduces the excitability of trigeminal ganglion nociceptors. B Taylor, editor. PLoS One. (2014);9:e87029. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087029

156. Guo, Z, Liu, P, Ren, F, and Cao, YQ. Nonmigraine-associated TRESK K+ channel variant C110R does not increase the excitability of trigeminal ganglion neurons. J Neurophysiol. (2014) 112:568–79. doi: 10.1152/jn.00267.2014

157. Rainero, I, Roveta, F, Vacca, A, Noviello, C, and Rubino, E. Migraine pathways and the identification of novel therapeutic targets. Expert Opin Ther Targets. (2020) 24:245–53. doi: 10.1080/14728222.2020.1728255

158. Tolner, EA, Houben, T, Terwindt, GM, De Vries, B, Ferrari, MD, and Van Den Maagdenberg, AMJM. From migraine genes to mechanisms. Pain. (2015) 156:S64–74. doi: 10.1097/01.j.pain.0000460346.00213.16

159. Enyedi, P, and Czirják, G. Properties, regulation, pharmacology, and functions of the k₂p channel, TRESK. Pflugers Arch. (2015) 467:945–58. doi: 10.1007/s00424-014-1634-8

160. Kowalska, M, Prendecki, M, Kozubski, W, Lianeri, M, and Dorszewska, J. Molecular factors in migraine. Oncotarget. (2016) 7:50708–18. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.9367

161. Zorina-Lichtenwalter, K, Meloto, CB, Khoury, S, and Diatchenko, L. Genetic predictors of human chronic pain conditions. Neuroscience. (2016) 338:36–62. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2016.04.041

162. Chen, S, and Ayata, C. Novel therapeutic targets against spreading depression. Headache. (2017) 57:1340–58. doi: 10.1111/head.13154

163. De Boer, I, Terwindt, GM, and Van Den Maagdenberg, AMJM. Genetics of migraine aura: an update. J Headache Pain. (2020) 21:64. doi: 10.1186/s10194-020-01125-2

164. Eren-Koçak, E, and Dalkara, T. Ion channel dysfunction and neuroinflammation in migraine and depression. Front Pharmacol. (2021) 12:777607. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.777607

165. Schreiber, JA, Düfer, M, and Seebohm, G. The special one: architecture, physiology and pharmacology of the TRESK channel. Cell Physiol Biochem. (2022) 56:663–84. doi: 10.33594/000000589

166. Gosalia, H, Karsan, N, and Goadsby, PJ. Genetic mechanisms of migraine: insights from monogenic migraine mutations. Int J Mol Sci. (2023) 24:12697. doi: 10.3390/ijms241612697

167. Ali, MD, Gayasuddin Qur, F, Alam, MS, Alotaibi, N, and Mujtaba, MA. Global epidemiology, clinical features, diagnosis and current therapeutic novelties in migraine therapy and their prevention: A narrative review. Curr Pharm Des. (2023) 29:3295–311. doi: 10.2174/0113816128266227231205114320

168. Ávalos Prado, P, Landra-Willm, A, Verkest, C, Ribera, A, Chassot, AA, Baron, A, et al. TREK channel activation suppresses migraine pain phenotype. iScience. (2021) 24:102961. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2021.102961

169. Huntemann, N, Bittner, S, Bock, S, Meuth, SG, and Ruck, T. Mini-review: two brothers in crime - the interplay of TRESK and TREK in human diseases. Neurosci Lett. (2022) 769:136376. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2021.136376

170. Della Pietra, A, Gómez Dabó, L, Mikulenka, P, Espinoza-Vinces, C, Vuralli, D, Baytekin, I, et al. Mechanosensitive receptors in migraine: a systematic review. J Headache Pain. (2024) 25:6. doi: 10.1186/s10194-023-01710-1

171. Al-Karagholi, MAM, Ghanizada, H, Nielsen, CAW, Skandarioon, C, Snellman, J, Lopez Lopez, C, et al. Opening of BKCa channels alters cerebral hemodynamic and causes headache in healthy volunteers. Cephalalgia. (2020) 40:1145–54. doi: 10.1177/0333102420940681

172. Wu, YJ, Davis, CD, Dworetzky, S, Fitzpatrick, WC, Harden, D, He, H, et al. Fluorine substitution can block CYP3A4 metabolism-dependent inhibition: identification of (S)-N-[1-(4-fluoro-3- morpholin-4-ylphenyl)ethyl]- 3- (4-fluorophenyl)acrylamide as an orally bioavailable KCNQ2 opener devoid of CYP3A4 metabolism-dependent inhibition. J Med Chem. (2003) 46:3778–81. doi: 10.1021/jm034111v

173. Wu, YJ, He, H, Sun, LQ, L’Heureux, A, Chen, J, Dextraze, P, et al. Synthesis and structure-activity relationship of acrylamides as KCNQ2 potassium channel openers. J Med Chem. (2004) 47:2887–96. doi: 10.1021/jm0305826

174. Silvestro, M, Iannone, LF, Orologio, I, Tessitore, A, Tedeschi, G, Geppetti, P, et al. Migraine treatment: towards new pharmacological targets. Int J Mol Sci. (2023) 24:12268. doi: 10.3390/ijms241512268

175. Gribkoff, VK. The therapeutic potential of neuronal K V 7 (KCNQ) channel modulators: an update. Expert Opin Ther Targets. (2008) 12:565–81. doi: 10.1517/14728222.12.5.565

176. Blom, SM, Schmitt, N, and Jensen, HS. The acrylamide (S)-2 as a positive and negative modulator of Kv7 channels expressed in Xenopus laevis oocytes. PLoS One. (2009) 4:e8251. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008251

177. Du, X, and Gamper, N. Potassium channels in peripheral pain pathways: expression, function and therapeutic potential. Curr Neuropharmacol. (2013) 11:621–40. doi: 10.2174/1570159X113119990042

178. Zhang, X, Jakubowski, M, Buettner, C, Kainz, V, Gold, M, and Burstein, R. Ezogabine (KCNQ2/3 channel opener) prevents delayed activation of meningeal nociceptors if given before but not after the occurrence of cortical spreading depression. Epilepsy Behav. (2013) 28:243–8. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2013.02.029

179. Devulder, J. Flupirtine in pain management: pharmacological properties and clinical use. CNS Drugs. (2010) 24:867–81. doi: 10.2165/11536230-000000000-00000

180. Wu, YJ, Boissard, CG, Greco, C, Gribkoff, VK, Harden, DG, He, H, et al. (S)-N-[1-(3-Morpholin-4-ylphenyl)ethyl]- 3-phenylacrylamide: an orally bioavailable KCNQ2 opener with significant activity in a cortical spreading depression model of migraine. J Med Chem. (2003) 46:3197–200. doi: 10.1021/jm034073f

181. Cregg, R, Momin, A, Rugiero, F, Wood, JN, and Zhao, J. Pain channelopathies. J Physiol. (2010) 588:1897–904. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.187807

182. Villatoro-Gómez, K, Pacheco-Rojas, DO, Moreno-Galindo, EG, Navarro-Polanco, RA, Tristani-Firouzi, M, Gazgalis, D, et al. Molecular determinants of Kv7.1/KCNE1 channel inhibition by amitriptyline. Biochem Pharmacol. (2018) 152:264–71. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2018.03.016

183. Haddaway, NR, Page, MJ, Pritchard, CC, and McGuinness, LA. PRISMA2020: an R package and shiny app for producing PRISMA 2020-compliant flow diagrams, with interactivity for optimised digital transparency and open synthesis. Campbell Syst Rev. (2022) 18:e1230. doi: 10.1002/cl2.1230

184. Martin, GM, Yoshioka, C, Chen, JZ, and Shyng, SL. Cryo-EM structure of the pancreatic ATP-sensitive K+ channel SUR1/Kir62 in the presence of ATP and glibenclamide [internet]. (2017).

186. Tao, X, Zhao, C, and MacKinnon, R. Cryo-EM structure of hSlo1 in plasma membrane vesicles [Internet]. (2023).

188. Natale, AM, Deal, PE, and Minor, DL. Structural insights into the mechanisms and pharmacology of K2P potassium channels. J Mol Biol. (2021) 433:166995. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2021.166995

189. Wang, W, Kiyoshi, CM, Du, Y, Taylor, AT, Sheehan, ER, Wu, X, et al. TREK-1 null impairs neuronal excitability, synaptic plasticity, and cognitive function. Mol Neurobiol. (2020) 57:1332–46. doi: 10.1007/s12035-019-01828-x

190. Inoue, M, Matsuoka, H, Harada, K, Mugishima, G, and Kameyama, M. TASK channels: channelopathies, trafficking, and receptor-mediated inhibition. Pflugers Arch. (2020) 472:911–22. doi: 10.1007/s00424-020-02403-3

191. Lee, H, Lolicato, M, Arrigoni, C, and Minor, DL. Chapter eight - production of K2P2.1 (TREK-1) for structural studies In: DL Minor and HM Colecraft, editors. Methods in enzymology [internet]. London: Academic Press (2021). 151–88.

192. Honrath, B, Krabbendam, IE, Culmsee, C, and Dolga, AM. Small conductance Ca2+−activated K+ channels in the plasma membrane, m itochondria and the ER: pharmacology and implications in neuronal dise ases. Neurochem Int. (2017) 109:13–23. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2017.05.005

193. Trombetta-Lima, M, Krabbendam, IE, and Dolga, AM. Calcium-activated potassium channels: implications for aging and age-r elated neurodegeneration. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. (2020) 123:105748. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2020.105748

194. Li, B, and Gallin, WJ. VKCDB: Voltage-gated potassium channel database. BMC Bioinformatics. (2004) 5:3. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-5-3

195. Barnwell, LFS, Lugo, JN, Lee, WL, Willis, SE, Gertz, SJ, Hrachovy, RA, et al. Kv4.2 knockout mice demonstrate increased susceptibility to convulsant stimulation. Epilepsia. (2009) 50:1741–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2009.02086.x

196. Sanguinetti, MC. HERG1 channelopathies. Pflugers Arch. (2010) 460:265–76. doi: 10.1007/s00424-009-0758-8

197. Guglielmi, L, Servettini, I, Caramia, M, Catacuzzeno, L, Franciolini, F, D’Adamo, MC, et al. Update on the implication of potassium channels in autism: K(+) channel autism spectrum disorder. Front Cell Neurosci. (2015) 9:34. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2015.00034

198. Clatot, J, Neyroud, N, Cox, R, Souil, C, Huang, J, Guicheney, P, et al. Inter-regulation of Kv4.3 and voltage-gated sodium channels underlies predisposition to cardiac and neuronal Channelopathies. Int J Mol Sci. (2020) 21:57. doi: 10.3390/ijms21145057

199. Hermanstyne, TO, Yang, ND, Granados-Fuentes, D, Li, X, Mellor, RL, Jegla, T, et al. Kv12-encoded K+ channels drive the day-night switch in the repetitive firing rates of SCN neurons. J Gen Physiol. (2023) 155:e202213310. doi: 10.1085/jgp.202213310

Glossary

2TM - Two Transmembrane Domain Channel

4TM - Four Transmembrane Domain Channel

6TM - Six Transmembrane Domain Channel

ATP - Adenosine Tri-Phosphate

BKCa - Large (Big) Conductance Calcium-Gated Potassium Channel

CGRP - Calcitonin Gene Related Peptide

CNS - Central Nervous System

CSD - Cortical Spreading Depression

GABA - Gamma Amino Butyric Acid

K2P - 2-Pore Domain Potassium Channel

KATP - ATP-Sensitive Potassium Channel

KCa - Calcium-Gated Potassium Channel

KIR - Inward Rectifying Potassium Channel

KV - Voltage-Gated Potassium Channel

PACAP - Poly Adenylate Cyclase Activating Peptide

RCSB - Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics

SKCa - Small Conductance Calcium-Gated Potassium Channel