- 1 Laboratory for Neuroengineering, Georgia Institute of Technology and Emory University School of Medicine Atlanta, GA, USA

- 2 Department of Biomedical Engineering, Georgia Institute of Technology and Emory University School of Medicine Atlanta, GA, USA

- 3 Department of Neurological Surgery, Emory University School of Medicine Atlanta, GA, USA

- 4 Department of Neurology, Emory University School of Medicine Atlanta, GA, USA

Multiple extracellular microelectrodes (multi-electrode arrays, or MEAs) effectively record rapidly varying neural signals, and can also be used for electrical stimulation. Multi-electrode recording can serve as artificial output (efferents) from a neural system, while complex spatially and temporally targeted stimulation can serve as artificial input (afferents) to the neuronal network. Multi-unit or local field potential (LFP) recordings can not only be used to control real world artifacts, such as prostheses, computers or robots, but can also trigger or alter subsequent stimulation. Real-time feedback stimulation may serve to modulate or normalize aberrant neural activity, to induce plasticity, or to serve as artificial sensory input. Despite promising closed-loop applications, commercial electrophysiology systems do not yet take advantage of the bidirectional capabilities of multi-electrodes, especially for use in freely moving animals. We addressed this lack of tools for closing the loop with NeuroRighter, an open-source system including recording hardware, stimulation hardware, and control software with a graphical user interface. The integrated system is capable of multi-electrode recording and simultaneous patterned microstimulation (triggered by recordings) with minimal stimulation artifact. The potential applications of closed-loop systems as research tools and clinical treatments are broad; we provide one example where epileptic activity recorded by a multi-electrode probe is used to trigger targeted stimulation, via that probe, to freely moving rodents.

Introduction

In their natural context, neural circuits are part of a sensory-motor loop. They are embodied along with sensory organs to perceive the environment in which the animal is situated. Neurons in turn control the animal’s movements, which results in new sensory input. This tight, continuous sensory-motor loop (from brain, to body, to environment, back to brain) is important for learning to predict the consequences of actions and is essential for optimizing adaptive behaviors (Chiel and Beer, 1997; Clark, 1997; Pfeifer and Bongard, 2007). Neuroscience researchers and biomedical engineers are beginning to appreciate how closing the loop around a neural circuit (Potter et al., 2006; Arsiero et al., 2007) can provide more natural information about nervous system dynamics, and lead to more effective treatment of nervous system disorders. Consider a typical open-loop experiment, where sensory input is presented to an anesthetized, reduced, or even disembodied nervous system, and its response is measured. In contrast, with closed-loop experiments, some aspects of how the nervous system responds will determine what is presented next, in real time, without experimenter intervention (Brice and McLellan, 1980). In this way, input and output sides of the nervous system can be studied together, in a more natural context. On the clinical side, consider the deep-brain stimulation currently used to treat Parkinsonism: stimulation parameters remain constant at levels set by the clinician, operating open-loop, regardless of the present brain state of the patient. In contrast, future closed-loop therapies will continuously tailor brain stimulation to optimize therapeutic effect and respond to changing brain states. By closing the loop with technology, researchers can probe or alter nervous system function not only in intact animals, but also in reduced preparations such as hybrots (Reger et al., 2000; DeMarse et al., 2001; Potter, 2002; Karniel et al., 2005; Bakkum et al., 2007). Considering that nervous systems are dynamic, complex, and responsive, it is logical that the tools we use to probe and modulate them should also be dynamic, complex, and responsive.

Closed-loop electrophysiology systems have two main parts, viewed from the animal’s perspective: an output (efferent) side, which acquires data from the neural system, and a sensory (afferent) side, which influences the neural system. Among the many ways to acquire neural signals (including electroencephalography, functional magnetic resonance imaging, magnetoencephalography, optical imaging, etc.), we focus on extracellular multi-microelectrode array (MEA) recordings. Likewise, there are many possible ways to alter neural activity: via the animal’s own sensory system, with electrical stimulation, pharmacology, optical control of ion channels (Zhang et al., 2007), etc. We focus on delivering neural stimuli via MEAs. Although MEAs are a proven mode of acquiring neural data for a range of prostheses and preparations (Chapin and Moxon, 2000; Taketani and Baudry, 2006), they are less often used for delivering stimulation patterns, with the notable and very successful exception of cochlear prostheses. Motor prostheses, such as artificial limbs, would benefit from having artificial sensory feedback (tactile, kinesthetic). Sensory prostheses and brain stimulation therapies might adapt to the users’ needs more quickly or effectively if they recorded and rapidly responded to the effects of their neural stimuli. Therapeutic and research tools enabled with closed-loop technology can deliver complex stimulation via many microelectrodes, while neural responses are continuously monitored via the same set of microelectrodes to influence subsequent stimulation. Integrated, responsive hybrid neural systems, comprised of both living and artificial components, will someday be commonplace.

For technical reasons such as stimulation artifacts and the unavailability of adequate commercial systems, MEAs are very seldom used for both stimulation and recording in one preparation. We have overcome some of the technical difficulties, and have developed closed-loop electrophysiology systems, including hardware and software, as part of an ongoing effort to study learning and information processing in vitro (Wagenaar et al., 2004, 2005a,bWagenaar and Potter, 2004).

Multi-Electrode Systems

There are a number of commercially available multi-microelectrode electrophysiology systems, but to our knowledge, none was designed with closed-loop applications in mind. Combining multi-microelectrode stimulation with multi-microelectrode recording, and enabling the recorded signals to trigger stimulus patterns dynamically in real time, is still very much at the experimental stage. We developed the first many-electrode system to close the loop around embodied cultured networks of ∼50,000 mammalian brain cells (Potter, 2001). This was comprised of the real-time all-channel stimulator (RACS) (Wagenaar and Potter, 2004) and our open-source MeaBench software suite (Wagenaar et al., 2005b). This system was designed to work with the MultiChannel Systems data acquisition card (MC-Card) and preamp (MEA60). It is modular, open-source, and has been replicated and used by a number of other labs. We have used it in closed-loop mode to suppress epileptiform activity in neural cultures (Wagenaar et al., 2005a), to electrically train cultures on a navigation task (Bakkum et al., 2008), and even to create art (Bakkum et al., 2007). MeaBench, though very flexible, is not very user-friendly, as experiments are carried out by scripting C++ software modules from the Linux command line.

Real-time closed-loop technology is being advanced by several other groups, with their own custom systems. Fetz and co-workers used single-electrode extracellular recordings in the monkey cortex to trigger single-electrode stimulation, which induced plasticity that altered functional connectivity and motor behavior. This was carried out with a custom wireless stimulation and recording setup (Jackson et al., 2006). Venkatraman et al. (2009) wrote custom software to allow high-speed videography of rat whisker motion to trigger multi-electrode cortical stimuli using their custom stimulation circuits and the Plexon Multichannel Acquisition Processor (Venkatraman et al., 2009). There are several many-channel CMOS IC (complementary metal oxide substrate integrated circuit) systems being developed for use on cultures or brain slices in vitro (Hutzler et al., 2006; Hafizovic et al., 2007; Hottowy et al., 2008; Berdondini et al., 2009), some with integrated stimulation capabilities. Hierlemann and co-workers at ETH Zurich have built an impressive CMOS IC system, expressly designed with closed-loop experiments in mind, such as using living networks as part of a liquid-state machine (Hafizovic et al., 2007). With 128 bidirectional electrodes, on-chip digitization and fast field-programmable gate array (FPGA)-based event detection, this elegant system points the way for future commercial closed-loop systems. However, custom fabrication of mixed-signal (analog and digital) silicon chips is prohibitively difficult and expensive, and beyond the capabilities of most biomedical researchers. Renaud and co-workers are developing an in vitro closed-loop system with electronics comprised of discrete components without custom ICs, and real-time software capable of very fast (sub-millisecond) stimulation feedback. Although the hardware design details and the software code have not been published to date, this promises to be a very flexible, modular system (Bontorin et al., 2007, 2009). We present a simpler and less expensive open-source hardware and software solution for labs wishing to pursue closed-loop electrophysiology using extracellular MEAs, either in vitro or in vivo.

Our success at suppression of epileptiform activity in cultures using closed-loop multi-electrode stimulation (Wagenaar et al., 2005b) led us to investigate whether similar protocols might suppress seizures in intact, freely moving, epileptic animals (Schachter et al., 2009). Many commercially available systems exist for conducting freely moving multi-electrode recording (for example, Plexon, Neuralynx, Multichannel Systems, Tucker-Davis Technologies, and others). Unfortunately, none was designed for closed-loop stimulation and they are all closed source. Therefore, we set out to adapt our RACS hardware to in vivo use, and to replace MeaBench with a more user-friendly software suite, called NeuroRighter, described below and in more detail in Frontiers in Neuroengineering (Rolston et al., 2009a,c). Both the hardware and software will continually improve because they are free and open-source (available at the Google Group, “NeuroRighter Users”), in an effort to make closed-loop multi-electrode electrophysiology easier to implement and more prevalent.

The Neurorighter System

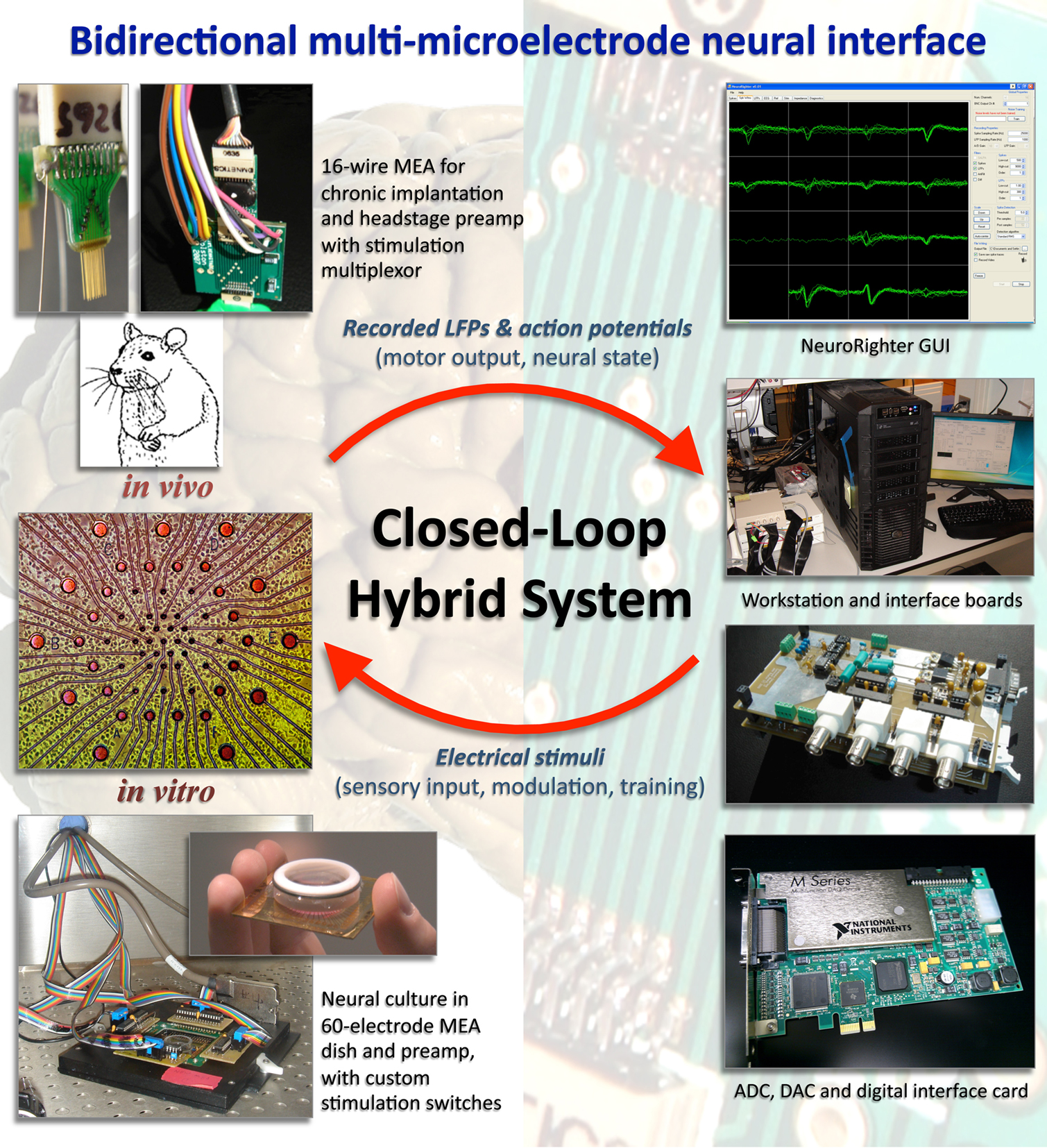

The “closed-loop” of the hybrid (neural-artificial) system takes the following path: (1) neural signals from multiple extracellular electrodes are amplified and filtered by analog hardware; (2) signals are digitized and processed by software, e. g., to detect action potentials or LFPs; (3) electrical stimulation hardware is triggered by detected events; and (4) stimuli are delivered to the neural tissue by the same (or different) electrodes (Figure 1). To adapt RACS hardware for use by freely moving animals, head-mounted components had to be light and sturdy enough for temporary attachment to a rodent’s head.

Figure 1. NeuroRighter system. The bidirectional multi-microelectrode system consists of custom interface circuit boards, a computer with National Instruments PCI-6259 multifunction cards, and the NeuroRighter control software. Interface boards are modular and stackable, so adding channels is straightforward. For freely moving animals, the in vivo components also include a recording headstage and stimulator headstage, which connect to the animal’s chronically implanted electrode array. The 16-wire MEA from Triangle Biosystems is shown, and the custom stimulator headstage is plugged between it and the Tucker-Davis Technologies recording headstage. The system also has connections for use with in vitro preparations, such as cortical cultures grown on MultiChannel Systems glass MEAs. The in vitro stimulation multiplexors plug in to the MultiChannel Systems MEA60 preamp, shown in a non-humidified incubator (Potter and DeMarse, 2001).

Recording Subsystem

The readouts of the living neural system are the neural action potentials and LFPs recorded by extracellular microelectrode arrays (Figure 1). The recording components include a headstage/preamp for amplifying the microvolt-level electrode signals and isolating stimuli, interface circuitry for analog filtering, an analog-to-digital converter (ADC), and software for real-time signal processing and recording (Rolston et al., 2009c). The system is modular, recording from 8 to 64 channels simultaneously at up to 30 kHz per channel. Three technological advances helped make this system less expensive than commercial counterparts. First, high-gain headstages/preamps (100–1000×) reduce the need for second stage amplifiers (sometimes also called “preamps”). Second, modern multifunction ADC cards have high precision (for example, the PCI-6259 we use from National Instruments is 16-bit with a full-scale range as sensitive as 200 mV). This high precision and sensitivity relaxes preamp and second stage amplification requirements. Third, computers are now powerful enough to do most filtering, spike detection, etc. in real-time. The advantage of implementing these features in software, rather than hardware, is the ease at which they can be improved or rapidly reconfigured for different applications. For example, when we devised a new method of digital referencing for multi-electrode recordings based on subtracting the common median, we added this feature and used it immediately (Rolston et al., 2009b). Since these advances lead to fewer components, the cost for a 64-channel system was less than US$10,000, compared to US$40,000–100,000 for comparable but more highly polished commercial systems (Rolston et al., 2009c).

Stimulation Subsystem

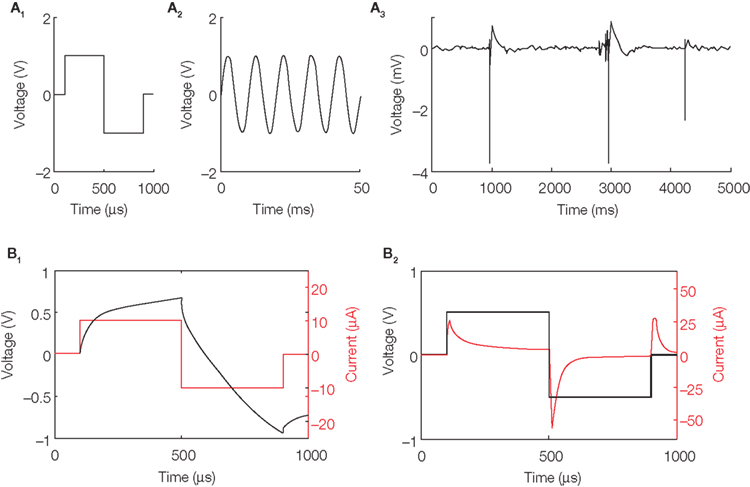

Multi-electrode electrical stimulation can serve several purposes: to deliver sensory input artificially, to modulate, or disrupt neural activity, and as a reinforcing or training signal. All of these were necessary for successful induction of goal-directed learning in vitro (Bakkum et al., 2008). The NeuroRighter stimulator is capable of stimulating with arbitrary waveforms from any electrode in a multi-electrode array (Figure 2). It improves on the RACS’s 8-bit DAC by using the NI-6259’s 16-bit DAC, to produce very smooth stimulus waveforms with a wide dynamic range. Stimulus commands are generated in software, converted to analog signals by the NI-6259, buffered and monitored in custom analog circuitry, and directed to particular electrodes by a headstage-mounted multiplexor (Figure 1). The in vivo stimulator can be used in several different configurations: by itself (with no recording headstage), with recording systems from a variety of manufacturers, or with the complete NeuroRighter system. Further details of the stimulator can be found in Rolston et al. (2009a).

Figure 2. Sample stimulation pulses. (A) Pulses can have arbitrary waveforms, such as biphasic pulses (A1), sine waves (A2), or even playing back previously recorded local field potentials (A3). The data from (A3) was obtained from an epileptic animal and shows several large-amplitude interictal spikes (de Curtis and Avanzini, 2001). How such low-voltage fields influence neuronal networks is an open question; for example, see McCormick and Contreras (2001), where ephaptic interactions are discussed, and Gluckman et al. (2001), where low-voltage fields are used to control epileptic activity. (B) Diagnostics allow monitoring of the voltage and current simultaneously, whether the pulse is current-controlled (B1) or voltage-controlled (B2). To generate the traces in (B1) and (B2), a 33-mm diameter tungsten microelectrode (Tucker-Davis Technologies, Inc.; Alachua, FL, USA) was stimulated in artificial cerebrospinal fluid (Rolston et al., 2009c) using a stainless steel wire as the counter (ground) electrode.

When the stimulation waveform is generated by the DAC, it exists as a voltage-controlled signal. That is, the voltage is specified precisely as a function of time by the software (1 μs precision), but the stimulation current is allowed to vary freely (Figure 2B2). However, the signal can also be converted by the interface board to current-controlled stimulation, if the user wishes. With a current-controlled stimulus, the current is specified as a function of time, but the voltage delivered to the tissue is allowed to vary freely within a safe range, determined by adjustable voltage regulators and protection diodes (Figure 2B1). In either mode, both voltage and current can be simultaneously monitored for diagnostic purposes. Although current-controlled stimulation is more commonly used (Merrill et al., 2005), some studies, such as Wagenaar et al. (2004), have shown greater efficacy of voltage- over current-controlled pulses. Many commercially available stimulators are only voltage-controlled, or only current-controlled, but not both, and often produce only fixed biphasic or monophasic waveforms. Merrill et al. (2005) describe many cases where biphasic “square” pulses are more damaging than more complexly shaped stimulus waveforms. Thus, the flexibility of the NeuroRighter stimulator gives tangible benefits.

Impedance Capabilities

Because the NeuroRighter stimulator monitors both the delivered voltage and current, and because it can deliver arbitrary waveforms, including sine waves that sweep across a wide frequency range (temporal resolution of 1 μs), the system can be used to monitor electrode impedance spectra. Impedance (Z, in Ohms) is the opposition to the flow of alternating current at a particular frequency. Measuring microelectrode impedance is important for three reasons – noise, stimulation, and the information that impedance spectroscopy provides about changes in biological tissue. The higher the impedance, the greater is the Johnson–Nyquist noise. Because electrode impedance is largely influenced by electrode surface area, impedance has become associated with tip diameter in neuroscience. It is important to note that impedance is not actually a function of the spatial extent of an electrode, but of its area. That is, it is possible to vary the surface area without varying the diameter, as our group has recently shown (Arcot Desai et al., 2010). Ultimately, the most sensitive, lowest noise microelectrode (for recording single cells) would have the smallest physical extent and an impedance of zero (Ross et al., 2004). Regarding stimulation, with lower electrode impedance, more current can be delivered at lower voltages to evoke a given response (thanks to Ohm’s law). This results in smaller stimulation artifacts and potentially less tissue damage, depending on whether such reductions are achieved by increasing capacitance, as in Arcot Desai et al. (2010), or by increasing the current carried via Faradic reactions (Merrill et al., 2005; Cogan, 2008). With electrode impedance spectroscopy (EIS), NeuroRighter can help determine physical and biological reactions to implanted electrodes (Merrill and Tresco, 2005; Lempka et al., 2009). Stimuli can be normalized across an array with electrodes of varying impedance, or as electrode impedance changes over time.

Closing the Loop

NeuroRighter’s stimulation and recording subsystems are useful on their own, but allow fundamentally different types of experiments when used as an integrated closed-loop system, as described above and in (Arsiero et al., 2007). The greatest difficulty with combining stimulation and recording on the same multi-electrode array, however, is the problem of stimulation artifacts. The neural signals typically recorded from extracellular electrodes are on the scale of 10 μV, while extracellular stimuli are on the scale of volts – a 100,000-fold difference. When recording electronics that are designed to amplify μV signals are exposed to typical stimuli, the electronics of commercially available systems saturate, sometimes recording no neural signals for over a second. Even when the electronics are no longer saturated, large artifacts often prevent detection of action potentials. These can sometimes be removed with adaptive filters, such as SALPA (Wagenaar and Potter, 2002). The NeuroRighter system, with its 16-bit ADC, single stage of amplification and real-time SALPA implementation, is able to record action potentials within 1 ms after a stimulus on an adjacent electrode (Rolston et al., 2009c). This is important, since neural responses to stimuli can occur within 1 ms of stimulus offset (Olsson et al., 2005; Rolston et al., 2009c). Long artifacts would obscure these important stimulus-evoked responses.

A closed-loop experiment

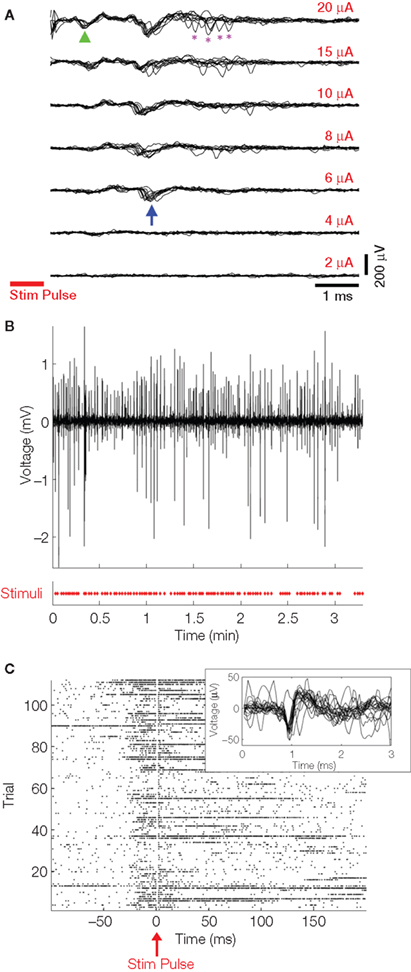

There is great interest in using brain stimulation to alleviate seizure disorders. Some closed-loop studies using EEG recordings to trigger macro-electrode stimuli are underway in animals and humans (Morrell, 2006; Colpan et al., 2007). As a demonstration of NeuroRighter’s closed-loop capabilities, we triggered stimulation in epileptic rats based on the detection of interictal spikes, large ∼100 ms LFPs exhibited in most presentations of epilepsy (de Curtis and Avanzini, 2001). Upon each detection, a stimulus pulse was delivered within 4–5 ms, illustrating the ability of the device to close the loop in physiological time scales. While brief pulses of electrical stimulation have been shown to suppress afterdischarges in humans (Lesser et al., 1999), it was not surprising that the small currents used in this experiment (±10 μA) were ineffective in altering the interictal spikes (Figure 3B). They did, however, evoke action potentials (Figure 3A,C). Future studies will test whether stimulation applied with more electrodes to different regions, or with different parameters (rate, pulse width, etc.), is able to effectively control or suppress interictal spikes in animal models. Further details of this experiment are presented in Rolston et al. (2009a).

Figure 3. Closed-loop stimulation responses. (A) Biphasic current-controlled stimuli (cathodic, negative phase first; 400 μs per phase) were delivered to an electrode in CA1 of the hippocampus, and responses were recorded as seen here in CA3. Ten trials of every stimulus amplitude are overlaid in each panel. Stimulus duration is indicated by the red bar. The first action potentials appear at a certain stimulus threshold (≥6 μA, blue arrow), with the latency decreasing as current is increased (green arrowhead). Additional, less consistent action potentials are recruited at high stimulation intensities (purple asterisks). All traces were digitally filtered with the SALPA algorithm (Wagenaar and Potter, 2002). Stimuli were delivered at 1 Hz and in random order (to guard against neural adaptation). (B) The LFP of an electrode in CA3 was monitored for interictal spikes (IISs) and a single 10 μA biphasic current-controlled pulse was delivered to one microelectrode upon IIS detection (red X’s in bottom panel). The displayed LFP trace (top panel) is from one electrode of an array implanted in CA1. The large amplitude is typical of LFPs during IISs and seizures. (C) A raster plot of action potentials recorded from all of the 16 electrodes during many IISs is shown, time-locked to the stimulus pulse. Action potentials are evoked by the stimulus at low latency following each pulse. The inset shows sample evoked AP waveforms recorded from one of the 16 electrodes during the experiment. This experiment is further characterized in Rolston et al. (2009a).

Open-Source Hardware

Open-source software has been common in neuroscience for decades. Free programming environments (Eclipse, EMACS, Visual Studio Express, ImageJ, etc.), closed-loop electrophysiology tools (e.g., RELACS, BioSig), and code repositories (SourceForge, Google Code) help make the software development and experimentation process more efficient and powerful. More recently, open-source hardware has become prevalent (e.g., the Open Prosthetics Google group; Thompson, 2008). Free, high-quality circuit design tools abound (e.g., ExpressPCB, PCB123, Eagle) and even circuit assembly can be automated at low cost (e.g., Screaming Circuits, Advanced Assembly). Having open-source circuitry with free software editors means the designs can be readily exchanged between researchers, and modifications quickly implemented, even by labs not skilled in electronics fabrication.

Although the NeuroRighter system currently uses some commercial components (as described above), it relies heavily on the open-source model. Our code is distributed via Google Groups and Google Code under the GNU Public License1 and all hardware designs under the Creative Commons License2. It is our hope that other scientists can benefit by using our system, by enhancing it, or by borrowing pieces for their own improved systems.

Conclusion

Because of the speed at which neural signals change, experimental perturbations benefit from precise temporal and spatial control. This control is best instantiated in closed-loop systems, where neural signals directly influence the timing and character of interventions such as multi-electrode stimulation. Commercial systems are lacking for closed-loop use with multi-electrode arrays in freely moving animals. The NeuroRighter system fills this gap by offering a multi-electrode recording system capable of complex closed-loop stimulation to all electrodes. Thanks to advances in open-source software development, circuit design, and hardware fabrication, other users can replicate the system or re-engineer it to better tackle problems in neuroscience and neuroengineering, in vitro and in vivo. These will form the basis of future therapies that take advantage of stimulation from multiple microelectrodes. Electrical training of neural tissue with patterned closed-loop stimulation (Jackson et al., 2006; Bakkum et al., 2008) has the potential to aid recovery from stroke or trauma, and to provide restoration or enhancement of cognitive function (Berger and Glanzman, 2005).

Conflict of Interest Statement

John Rolston received consulting fees from Axion Biosystems, which is developing stimulation and recording systems for neural cultures. The other authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (NS054809), the Emory University Neurosciences Initiative, a Coulter Foundation Translational Research Award, the National Science Foundation (EFRI 0836017), and an Epilepsy Research Foundation New Therapy Grant. We also thank the students of Georgia Tech’s Hybrid Neural Microsystems course (Robert Ortman, Jeff Bingham, Wafa Soofi, and Ryan Hooper) and Dr. Chad Hales for helping adapt NeuroRighter for use in vitro.

Key Concepts

A system which creates output regardless of external conditions, or which reads input and takes no action to affect further input. A simple example is a quartz watch, which tracks time, but receives no feedback from the world outside.

A system where a sensed signal alters the system output which, in turn, may alter the sensed signals. A prototypical example is an air conditioner, where a thermometer measures temperature, which will determine whether more or less cold air is pumped out. Because this cold air alters the temperature, the system is a closed loop.

A hybrid of a living neuronal system and a robot. It is most often used to refer to a mobile robot controlled by a neuronal network maintained in vitro. With such artificially embodied in vitro networks, the experimenter has complete control of the inputs to a simplified nervous system. The term can also describe animals or people with neural interfaces to robotic limbs or other mechanical actuators.

Signals, such as action potentials, emanating from the living neural system. In the natural context, efferents cause muscles to contract (or glands to secrete). Any signal recorded artificially from the neural system can be viewed as an efferent, and used to control external actuators, or to trigger stimulation.

Signals carried into the neural system, such as action potentials from sensory organs. Electrical stimuli can serve as artificial afferents, to carry sensory information, induce plasticity, or modulate ongoing activity.

Large-amplitude signal picked up by recording electrodes during and after an electrical stimulation pulse. The artifacts obscure underlying neural signals, like action potentials or the local field potential. They occur because the amplitude of stimulation (on the order of volts) is orders of magnitude greater than extracellular signal (10–100s of microvolts).

Practice by which software or hardware is released along with its underlying code, schematics, or other source materials. Open-source projects, depending on their licensing, allow users to explore, validate, and modify the sources, potentially bringing about more stable, useful products.

Practice by which software or hardware is released without providing users access to the underlying code, schematics, or other source materials. This provides some protection of intellectual property for the creator, though does not prevent reverse engineering.

Burst of neural activity, lasting 10–100s of milliseconds, observed in the extracellular field potential (e.g., EEG, LFP). Indicative of epilepsy or seizures, but occurring between seizures – inter meaning between, ictal meaning seizure (when used in medical literature).

Footnotes

References

Arcot Desai, S., Rolston, J. D., Guo, L., and Potter, S. M. (2010). Improving impedance of implantable microwire multi-electrode arrays by ultrasonic electroplating of durable platinum black. Front. Neuroengineering 4. doi:10.3389/fneng.2010.00005.

Arsiero, M., Luscher, H., R., and Giugliano, M. (2007). Real-time closed-loop electrophysiology: towards new frontiers in in vitro investigations in the neurosciences. Arch. Ital. Biol. 145, 193–209.

Bakkum, D. J., Chao, Z. C., and Potter, S. M. (2008). Spatio-temporal electrical stimuli shape behavior of an embodied cortical network in a goal-directed learning task. J. Neural Eng. 5, 310–323.

Bakkum, D. J., Gamblen, P. M., Ben-Ary, G., Chao, Z. C., and Potter, S. M. (2007). MEART: the semi-living artist. Front. Neurorobotics. 1, 5. doi:10.3389/neuro.12.005.2007.

Berdondini, L., Imfeld, K., Maccione, A., Tedesco, M., Neukom, S., Koudelka-Hep, M., and Martinoia, S. (2009). Active pixel sensor array for high spatio-temporal resolution electrophysiological recordings from single cell to large scale neuronal networks. Lab. Chip 9, 2644–2651.

Berger, T. W., and Glanzman, D. L. (2005). Toward Replacement Parts for the Brain: Implantable Biomimetic Electronics as Neural Prostheses. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Bontorin, G., Renaud, S., Garenne, A., Alvado, L., Le Masson, G., and Tomas, J. (2007). A real-time closed-loop setup for hybrid neural networks. Conf. Proc. IEEE Eng. Med. Biol. Soc. 2007, 3004–3007.

Bontorin, G., Garenne, A., Tomas, J., Lopez, C., Morin, F. O., and Renaud, S. (2009). “A real-time system for multisite stimulation on living neural networks,” in Paper presented at the IEEE North East Workshop on Circuits and Systems (NEWCAS09), Toulouse, France.

Brice, J., and McLellan, L. (1980). Suppression of intention tremor by contingent deep-brain stimulation. Lancet 1, 1221–1222.

Chapin, J. K., and Moxon, K. A. (2000). Neural Prostheses for Restoration of Sensory and Motor Function. Boca Raton: CRC Press.

Chiel, H. J., and Beer, R. D. (1997). The brain has a body: adaptive behavior emerges from interactions of nervous system, body and environment. Trends Neurosci., 20, 553–557.

Clark, A. (1997). Being There: Putting Brain, Body, and the World Together Again. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Cogan, S. F. (2008). Neural stimulation and recording electrodes. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 10, 275–309.

Colpan, M. E., Li, Y., Dwyer, J., and Mogul, D. J. (2007). Proportional feedback stimulation for seizure control in rats. Epilepsia 48, 1594–1603.

de Curtis, M., and Avanzini, G. (2001). Interictal spikes in focal epileptogenesis. Prog. Neurobiol. 63, 541–567.

DeMarse, T. B., Wagenaar, D. A., Blau, A., W., Potter, and S. M. (2001). The neurally controlled animat: biological brains acting with simulated bodies. Auton. Robots 11, 305–310.

Gluckman, B. J., Nguyen, H., Weinstein, S. L., and Schiff, S. J. (2001). Adaptive electric field control of epileptic seizures. J. Neurosci. 21, 590–600.

Hafizovic, S., Heer, F., Ugniwenko, T., Frey, U., Blau, A., Ziegler, C., and Hierlemann, A. (2007). A CMOS-based microelectrode array for interaction with neuronal cultures. J. Neurosci. Methods 164, 93–106.

Hottowy, P., Dabrowski, W., Skoczen, A., and Wiacek, P. (2008). An integrated multichannel waveform generator for large-scale spatio-temporal stimulation of neural tissue. Analog Integr. Circ. Sig. Process 55, 239–248.

Hutzler, M., Lambacher, A., Eversmann, B., Jenkner, M., Thewes, R., and Fromherz, P. (2006). High-resolution multitransistor array recording of electrical field potentials in cultured brain slices. J. Neurophysiol. 96, 1638–1645.

Jackson, A., Mavoori, J., and Fetz, E. E. (2006). Long-term motor cortex plasticity induced by an electronic neural implant. Nature 444, 56–60.

Karniel, A., Kositsky, M., Fleming, K., M., Chiappalone, M., Sanguineti, V., Alford, S., T., and Mussa-Ivaldi, F. A. (2005). Computational analysis in vitro: dynamics and plasticity of a neuro-robotic system. J. Neural Eng. 2, S250–S265.

Lempka, S. F., Miocinovic, S., Johnson, M. D., Vitek, J. L., and McIntyre, C. C. (2009). In vivo impedance spectroscopy of deep brain stimulation electrodes. J. Neural Eng 6, 46001.

Lesser, R. P., Kim, S. H., Beyderman, L., Miglioretti, D. L., Webber, W. R., Bare, M., Cysyk, B., Krauss, G., and Gordon, B. (1999). Brief bursts of pulse stimulation terminate afterdischarges caused by cortical stimulation. Neurology 53, 2073–2081.

McCormick, D. A., and Contreras, D. (2001). On the cellular and network bases of epileptic seizures. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 63, 815–846.

Merrill, D. R., and Tresco, P. A. (2005). Impedance characterization of microarray recording electrodes in vitro. Biomed. Eng. IEEE Trans. 52, 1960–1965.

Merrill, D. R., Bikson, M., and Jefferys, J. G. R. (2005). Electrical stimulation of excitable tissue: design of efficacious and safe protocols. J. Neurosci. Methods 141, 171–198.

Morrell, M. (2006). Brain stimulation for epilepsy: can scheduled or responsive neurostimulation stop seizures? Curr. Opin. Neurol. 19, 164–168.

Olsson, R. H., 3rd, Buhl, D. L., Sirota, A. M., Buzsaki, G., and Wise, K. D. (2005). Band-tunable and multiplexed integrated circuits for simultaneous recording and stimulation with microelectrode arrays. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 52, 1303–1311.

Pfeifer, R., and Bongard, J. (2007). How the Body Shapes the Way We Think: A New View of Intelligence. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Potter, S. M. (2001). Distributed processing in cultured neuronal networks. Prog. Brain Res. 130, 49–62.

Potter, S., M., and De Marse, T. B. (2001). A new approach to neural cell culture for long-term studies. J. Neurosci. Methods 110, 17–24.

Potter, S. M. (2002). “Hybrots: hybrid systems of cultured neurons+robots, for studying dynamic computation and learning,” in 7th International Conference on the Simulation of Adaptive Behavior, Edinburgh, UK.

Potter, S. M., Wagenaar, D. A., and DeMarse, T. B. (2006). “Closing the loop: stimulation feedback systems for embodied MEA cultures,” in Advances in Network Electrophysiology Using Multi-electrode Arrays, eds. M. Taketani and M. Baudry (New York: Springer), 215–242.

Reger, B. D., Fleming, K. M., Sanguineti, V., Alford, S., and Mussa-Ivaldi, F., A. (2000). Connecting brains to robots: an artificial body for studying the computational properties of neural tissues. Artif. Life 6, 307–324.

Rolston, J. D., Gross, R. E., and Potter, S. M. (2009a). “NeuroRighter: closed-loop multi-electrode stimulation and recording for freely moving animals and cell cultures,” in 31st Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society, Minneapolis, MN.

Rolston, J. D., Gross, R. E., and Potter, S. M. (2009b). “Common median referencing for improved action potential detection with multi-electrode arrays,” in 31st Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society, Minneapolis, MN.

Rolston, J. D., Gross, R. E., and Potter, S. M. (2009c). A low-cost multi-electrode system for data acquisition enabling real-time closed-loop processing with rapid recovery from stimulation artifacts. Front. Neuroengineering 2, 12. doi:10.3389/neuro.16.012.2009.

Ross, J. D., O’Connor, S. M., Blum, R. A., Brown, E. A., and DeWeerth, S. P. (2004). Multi-electrode impedance tuning: reducing noise and improving stimulation efficacy. Conf. Proc. IEEE Eng. Med. Biol. Soc. 6, 4115–4117.

Schachter, S. C., Guttag, J., Schiff, S. J., and Schomer, D. L. (2009). Advances in the application of technology to epilepsy: the CIMIT/NIO epilepsy innovation summit. Epilepsy Behav. 16, 3–46.

Taketani, M., and Baudry, M. eds. (2006) Advances in Network Electrophysiology Using Multi-electrode Arrays. New York: Springer.

Venkatraman, S., Elkabany, K., Long, J. D., Yao, Y., and Carmena, J. M. (2009). A system for neural recording and closed-loop intracortical microstimulation in awake rodents. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 56, 15–22.

Wagenaar, D. A., and Potter, S. M. (2002). Real-time multi-channel stimulus artifact suppression by local curve fitting. J. Neurosci. Methods 120, 113–120.

Wagenaar, D. A., Pine, J., and Potter, S. M. (2004). Effective parameters for stimulation of dissociated cultures using multi-electrode arrays. J. Neurosci. Methods 138, 27–37.

Wagenaar, D. A. and Potter, S. M. (2004). A versatile all-channel stimulator for electrode arrays, with real-time control. J. Neural Eng. 1, 39–45.

Wagenaar, D. A., Madhavan, R., Pine, J., and Potter, S. M. (2005a). Controlling bursting in cortical cultures with closed-loop multi-electrode stimulation. J. Neurosci. 25, 680–688.

Wagenaar, D. A., DeMarse, T. B., and Potter, S. M. (2005b). “MeaBench: A toolset for multi-electrode data acquisition and on-line analysis,” in 2nd Intl. IEEE EMBS Conf. Neural Eng. 518–521.

Keywords: multi-electrode array, stimulation, epilepsy, closed-loop, artifact

Citation: Rolston JD, Gross RE and Potter SM (2010) Closed-loop, open-source electrophysiology. Front. Neurosci. 4:31. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2010.00031

Received: 20 February 2010;

Paper pending published: 18 March 2010;

Accepted: 11 May 2010;

Published online: 15 September 2010

Edited by:

Sergio Martinoia, University of Genova, ItalyReviewed by:

Enrique Claverol Technical University of Catalonia, SpainAxel Blau The Italian Institute of Technology, Italy

Copyright: © 2010 Rolston, Gross and Potter. This is an open-access article subject to an exclusive license agreement between the authors and the Frontiers Research Foundation, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original authors and source are credited.

*Correspondence: Steve M. Potter, 313 Ferst Dr NW, 0535 Laboratory for Neuroengineering, Coulter Department of Biomedical Engineering, Georgia Institute of Technology, Atlanta, GA, 30332-0535 USA.c3RldmUucG90dGVyQGJtZS5nYXRlY2guZWR1