- Developmental Genetics of the Nervous System, Max Planck Institute for Medical Research, Heidelberg, Germany

The circadian activity of the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal/interrenal (HPA/I) axis is crucial for maintaining vertebrate homeostasis. In mammals, both the principle regulator, corticotropin-releasing hormone (crh) in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus (PVN) and the final effector, the glucocorticoids show daily rhythmic patterns. While glucocorticoids are the main negative regulator of PVN crh under stress, whether they modulate the PVN crh rhythm under basal condition is unclear in diurnal animals. Using zebrafish larvae, a recently-established diurnal model organism suited for the HPA/I axis and homeostasis research, we ask if glucocorticoid changes are required to maintain the daily variation of PVN crh. We first characterized the development of the HPI axis overtime and showed that the basal activity of the HPI axis is robust and tightly regulated by circadian cue in 6-day old larvae. We demonstrated a negative correlation between the basal cortisol and neurosecretory preoptic area (NPO) crh variations. To test if cortisol drives NPO crh variation, we analyzed the NPO crh levels in glucorcorticoid antagonist-treated larvae and mutants lacking circadian cortisol variations. We showed that NPO crh basal fluctuation is sustained although the level was decreased without proper cortisol signaling in zebrafish. Our data indicates that glucocorticoids do not modulate the basal NPO crh variations but may be required for maintaining overall NPO crh levels. This further suggests that under basal and stress conditions the HPA/I axis activity is modulated differently by glucocorticoids.

Introduction

The neuroendocrine system hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal/interrenal (HPA/I) axis plays an essential role in maintaining the homeostasis of vertebrates under fluctuating environment (Charmandari et al., 2005; Chrousos, 2009). To regulate body physiology under both basal and stress conditions, the activity of HPA/I axis components were tightly linked to each other and subjected to external stimuli (Tsigos and Chrousos, 2002). Until now, the basal circadian and stress-induced variations of the HPA axis and of its final effectors glucocorticoids have been well characterized particularly in rodents (Watts, 1996; Watts et al., 2004; de Kloet et al., 2005). It is known that corticortropin-releasing hormone (CRH) from the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus (PVN) and adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) from the pituitary play essential roles in regulating glucocorticoid variations (Muglia et al., 1997; Smith et al., 1998; Liu et al., 2011) and glucocorticoids negatively modulate these factors through genomic or non-genomic mechanisms (Malkoski and Dorin, 1999; Newton, 2000; Herman et al., 2012).

Under stress, glucocorticoids negatively regulate PVN crh transcripts through a glucocorticoid receptor-dependent mechanism (Malkoski and Dorin, 1999; van Der Laan et al., 2009; Jeanneteau et al., 2012). However, whether under basal condition glucocorticoids play a role in generating or maintaining the circadian pattern of PVN crh in vivo is not clear for diurnal animals. Although, the level of PVN crh transcripts negatively correlates with the circadian range of corticosterone (main glucocorticoids in rodent), diminishing the circadian variation of corticosterone or the glucorcoticoid signaling did not eliminate the basal rhythm of PVN crh transcript in rat and mice (Watts et al., 2004; Laryea et al., 2013, 2015). This suggests that at least in nocturnal rodents, glucocorticoid-mediated negative feedback is not required for the circadian PVN crh variations.

The zebrafish, Danio rerio is considered as a suited vertebrate model for studying the neuroendocrine system of diurnal animals. Zebrafish HPI axis shares conserved anatomical, molecular and functional features with the HPA axis of mammals (To et al., 2007; Alsop and Vijayan, 2009; Löhr and Hammerschmidt, 2011). The hypothalamus and pituitary of zebrafish process the conserved signaling molecules and cell types (Liu et al., 2003; Dickmeis et al., 2007; Herget et al., 2014). The larval stage of zebrafish has been used to understand HPA axis- and glucocorticoid-related physiology and behavior (Clark et al., 2011; Steenbergen et al., 2011). At 5 days old, zebrafish larvae show robust increases of cortisol level upon stress exposures (Yeh et al., 2013). Alterations in the glucocorticoid signaling induce specific cellular circadian and metabolic defects (Dickmeis et al., 2007; Lin et al., 2011). It also disrupts normal development and changes stress-related behaviors in larvae and adults (Griffiths et al., 2012; Nesan et al., 2012; Ziv et al., 2013). Yet, the circadian-related characteristics of the HPI axis are largely unknown in this diurnal organism.

Therefore, here the circadian activity of the HPI axis and the role of glucocorticoids in modulating basal HPI axis activity were addressed. We first characterized the circadian patterns of the HPI axis in developing zebrafish larvae. We showed that the HPI axis is fully mature and tightly regulated through circadian light cues in 6 day-old larvae. We observed the negative correlation between the basal cortisol and NPO crh suggesting the presence of the glucocorticoid-mediated negative feedback. We then tested if cortisol modulates the NPO crh daily variation using larvae with compromised circadian cortisol variation and cortisol signaling. Our results indicate that the basal variation of NPO crh transcripts in zebrafish is maintained in a glucocorticoid-independent manner although the level is decreased. Under basal condition, glucocorticoids is likely to play a critical role in regulating the overall level of NPO crh rather than sustaining its fluctuation.

Materials and Methods

Zebrafish Maintenance, Treatment and Strains

Zebrafish breeding and maintenance was performed under standard conditions (Westerfield, 2000). Embryos were collected in the morning and raised on a 12:12 light/dark cycle in E2 medium or E2 medium with 0.2 mM 1-phenyl-2-thiourea to avoid pigment formation (Westerfield, 2000). Larvae were incubated from 5 dpf evening in 2 μM Mifepristone (RU-486, Sigma-Aldrich) dissolved in E2-Medium with 0.1% DMSO (Weger et al., 2012). AB/TL wild type strain is used. Rx3 fishes were incrossed and their progenies were screened for the presence of eyes for homozygous at 2 dpf (Dickmeis et al., 2007). The experiments were performed on 6 dpf larvae unless further indicated. Zebrafish experimental procedures were performed according to the guidelines of the German animal welfare law and approved by the animal protection office of the Max Planck Institute and the regional government office of Karlsruhe.

Cortisol ELISA

Groups of 30 larvae were immobilized in ice water, frozen in ethanol/dry ice bath, and stored at −20°C. Cortisol from homogenized samples was extracted with ethyl acetate. We employed the extraction and cortisol ELISA protocol (Yeh et al., 2013) using cortisol mouse antibody (EastCoast Bio), cortisol standards (Hydrocortisone, Sigma-Aldrich) and Cortisol-HRP (EastCoast Bio). The reactions were stopped using 1M sulfuric acid and read at 450 nm in an ELISA-reader (Multiskan Ascent, Thermo Scientific). The data were corrected for dilution factor, extraction efficiency and recovery function.

Probes, in situ Hybridization (ISH) and Image Analysis

Whole-mount ISH was performed as described (Hauptmann and Gerster, 1994). The design of crh in situ probe is described previously (Löhr et al., 2009). To quantify cell numbers, the trunks of the larvae were cut off to avoid orientation problem. The cells were visualized from dorsal view under the DIC microscope using 10x objective lens (Leica, DM5500).

qRT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from 30 larvae (N = 4–5) using Trizol (Invitrogen) and PureLink RNA Mini Kit (Ambion). qRT-PCR was performed using Power SYBR® Green RNA-to-CT™ 1-Step kit (Applied Biosystems) with Applied Biosystems 7500 RT-PCR system. Primers: ef1alpha mRNA_Forward: CTGGAGGCCAGCTCAAACGT; Reverse:ATCAAGAAGAGTAGTACCGCTAGCATTAC. Period circadian clock, per4 (Cavallari et al., 2011).

Statistical Analysis

All data are shown as mean and standard error of the mean (S.E.M.). We used Student's t-tests (two-tailed) for two-group comparisons, or Mann-Whitney U-tests if the data did not fulfill the assumptions of the t-test. We used ANOVAs for multiple group comparisons, followed by Bonferroni's post-hoc tests. We analyzed data using Prism 5 (Graphpad Software). * indicates p < 0.05, ** indicates p < 0.01 and *** indicates p < 0.001.

Experimental Design

Cortisol circadian fluctuation in larvae was determined by three steps. First, the development of cortisol pattern is determined by measuring cortisol levels from 2 dpf evening to 6 dpf evening (N = 12–18). To address if cortisol fluctuations are driven by the internal circadian clock, larvae were raised under light/dark cycle until 4 dpf and kept under darkness until being sampled for cortisol levels (N = 9–15). Finally, to address if light establishes cortisol circadian fluctuations, the larvae were raised under darkness until being sampled (N = 12).

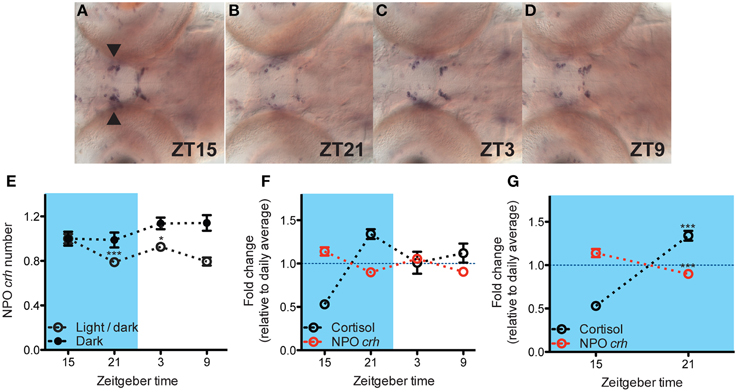

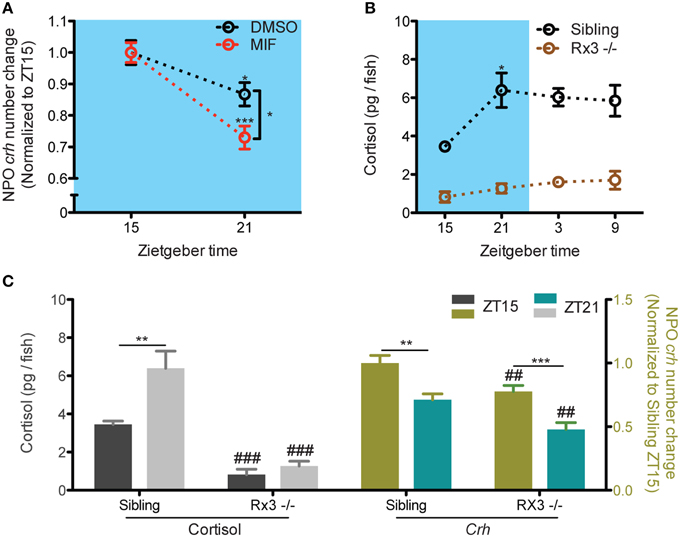

To investigate the relationship between basal NPO crh and cortisol level, we analyzed the daily variation of NPO crh mRNA positive cells (examples shown in Figures 2A–D; refer as NPO crh in the following text) in 6 dpf larvae when the cortisol fluctuation is robust (N = 23–24). Miprefistone (MIF), an antagonist of glucocorticoids that binds to GRs and diminishes the glucocorticoid signaling (N = 19–37; Andrews et al., 2012; Weger et al., 2012) and rx3 mutants whose cortisol signaling has been proved to be defective (cortisol: N = 6–10; crh: N = 12–15; Dickmeis et al., 2007) were used to addressed the effects of cortisol on NPO crh. The results were reported from one of two people who counted the NPO crh cell number blindly. One experiment, the MIF treated experiment is repeated and the result is confirmed by one additional person.

Result

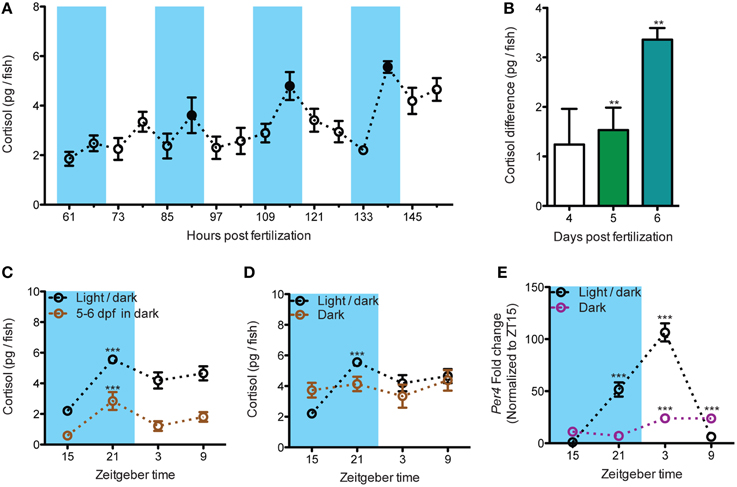

The Establishment of the HPI Axis Circadian Activity in Zebrafish Larvae

The measurement of basal cortisol level every 6 hours from 61 to 151 hours post fertilization (hpf) showed that, starting from 85 hpf, a repeated daily fluctuation of cortisol can be detected. The nadir of cortisol level occurred at ZT15 (zeitgeber time 15, 11 p.m.) and the level increased to the peak at ZT21 (5 a.m.; Figure 1A: black dots). The differences of cortisol level between these two continuous time points became larger over days and are differing from 0 starting at 5 dpf (Figure 1B: Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test: 4 dpf: p = 0.107; 5 dpf: p = 0.003; 6 dpf: p = 0.003). Furthermore, larvae raised under circadian light cue until 4 dpf were able to maintain the cortisol fluctuation under darkness at 6 dpf (Figure 1C: One-way ANOVA, Light/dark: F = 14.2, p < 0.001; 5–6 dpf dark: F = 6.7, p < 0.001, Bonferroni's post-tests: compare all pairs of columns and significant difference from the previous time point are shown). Noteworthy, larvae never exposed to circadian light cue did not establish proper cortisol basal variations (Figure 1D: One-way ANOVA, Dark: F = 0.6, p = 0.642). The dampening of the cortisol rhythm is accompanied by the alteration of the core circadian regulating gene, period circadian clock, per4 [Figure 1E: Two-way ANOVA, treatment × time: F(3, 28) = 81.5, p < 0.001; Bonferroni's post-tests for significant difference from ZT 15 group]. In sum, we showed a robust circadian rhythm of cortisol which is established overtime in the developing zebrafish larvae by the circadian light cues.

Figure 1. The establishment of the circadian cortisol rhythm during early larval development. (A) Establishment of circadian cortisol rhythm under light/dark cycles in developing larvae (dark periods are shadowed in blue). A repeated increase of cortisol level can be seen at each dark cycles starting from 85 hpf. The daily peak of cortisol was indicated by the black spots (N61−103hpf = 18, N109−151hpf = 12). (B) The amplitude of daily cortisol fluctuation during dark phases increased overtime. The amplitude was calculated from the cortisol difference at each dark period (4 dpf: 91 hpf - 85 hpf, 5 dpf: 115 hpf - 109 hpf, and 6 dpf: 139 hpf - 133 hpf; N4dpf and N5dpf = 18, N6dpf = 12). (C) The circadian fluctuation of cortisol is maintained in larvae deprived from light cue for 24 h (N = 9–15). (D) The circadian cortisol fluctuation is blunted in larvae raised without circadian light cue (N = 12). (E) per4 mRNA circadian fluctuation is altered in larvae raised without circadian light cue (N = 4–5). **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001.

Negative Correlations Between NPO crh Number and Cortisol Level Under Basal Condition

Next, we addressed the relationship between cortisol and NPO crh. Under basal condition, NPO crh levels show a daily variation which is eliminated in larvae deprived from circadian light cue (Figures 2A–E: One-way ANOVA, Light/dark: F = 8.6, p < 0.001; Dark: F = 1.8, p = 0.1598, Bonferroni's post-tests: compare all pairs of columns and significant difference from the previous time point are shown). As predicted from previous studies in rodent, we observed that the variation of NPO crh corresponded to that of cortisol in an inverse manner (Figure 2F). Importantly, from ZT15 to ZT21 when cortisol rises from its nadir to its peak, there is a corresponding decrease of NPO crh [Figure 2G: Two-way ANOVA, treatment × time: F(1, 67) = 117.9, p < 0.001; Bonferroni's post-tests for significant difference from ZT 15 group]. In summary, the NPO crh displays a variation regulated by circadian light cues and correlates negatively to the cortisol rhythms.

Figure 2. Negative correlation between NPO crh and cortisol level under basal condition. (A–D) Representative crh in situ pictures at 4 different time points. NPO crh mRNA positive cells (arrowhead) at different time were quantified. (E) The NPO crh shows a daily variation which is abolished by light deprivation (N = 23–24) (F) Daily variations of NPO crh and cortisol level showed reversed patterns. NPO crh and cortisol were plotted together after normalized to their daily average which was set to 1 respectively (Cortisol: N = 12; NPO crh: N = 23–24). (G) Negative correlation can be detected between NPO crh cell number and cortisol level when cortisol rises from its nadir to peak level (data from G). *p < 0.05 and ***p < 0.001.

NPO crh Daily Fluctuations and Cortisol Signaling

Next, we directly addressed if the negative feedback of cortisol results in NPO crh decrease. The reduction of NPO crh from ZT15 to ZT21 was still observed under overnight miprefistone (MIF) treatment (Figure 3A: t-test, DMSO: T = 2.5, p = 0.018; MIF: T = 5.4, p < 0.001, for significant difference from ZT21 group). The level of NPO crh at ZT21 is lower with MIF treatment (Figure 3A: t-test, T = 2.6, p = 0.012). Furthermore, we used rx3 mutants which showed undetectable circadian cortisol fluctuation (Figure 3B: One-way ANOVA, Sibling: F = 4.2, p = 0.0188; Rx3 -/-: F = 1.6, p = 0.2154, Bonferroni's post-tests: compare all pairs of columns and significant difference from the previous time point are shown). In the mutant larvae, the decrease of NPO crh from ZT 15 to ZT 21 was sustained (Figure 3C: t-test, sibling cortisol: T = 3.2, p = 0.009; rx3 cortisol: T = 1.2, p = 0.245; sibling crh:T = 3.7, p = 0.001; rx3 crh: T = 4.2, p < 0.001). The levels of cortisol and NPO crh are lower in rx3 comparing with their siblings (Figure 3A: t-test, cortisol ZT15: T = 6.8, p < 0.001; cortisol ZT21: T = 6.8, p < 0.001; crh ZT15: T = 2.9, p = 0.007; crh ZT21: T = 3.2, p = 0.003). Thus, our data suggests that under basal condition, the decrease of NPO crh is not driven by the negative feedback of cortisol signaling. Nevertheless, cortisol may be required to maintain proper basal NPO crh levels.

Figure 3. NPO Crh variation but not the level was sustained in larvae with compromised cortisol signaling. (A) MIF did not alter the fluctuation of NPO crh from ZT15 to ZT21 but changed the level of NPO crh at ZT21 (DMSO: NZT15 = 19, NZT21 = 19; MIF: NZT15 = 37, NZT21 = 20). (B) No cortisol rhythm can be detected in rx3 mutant in contrast to that in their siblings (Rx3 sibling: N = 6; rx3: N = 10). (C) Normal NPO crh but not cortisol fluctuation can be detected between from ZT15 to ZT21 in rx3 mutant. The levels of NPO crh and cortisol are reduced in rx3 mutants (Cortisol: rx3 sibling: N = 6; rx3: N = 10; crh: rx3 sibling: NZT15 = 14 and NZT21 = 12; rx3: N = 15). *p < 0.05, **, ##p < 0.01 and, ***, ###p < 0.001.

Discussion

In this study, the circadian cortisol variations and its link to the NPO crh changes were addressed using the diurnal zebrafish larvae. As the first step, we reported the maturation of the HPI axis and found robust circadian rhythms of cortisol and NPO crh daily variation in 6 dpf larvae. We showed a negative correlation between NPO crh and cortisol indicating the presence of glucocorticoid-mediated negative feedback. Interestingly, diminishing cortisol signaling using glucocorticoid antagonist and mutants does not abolish the NPO crh daily variations but alter the levels of NPO crh. This suggests that the basal fluctuation but not the level of the hypothalamic crh is independent of the proper circadian glucocorticoid signaling in diurnal organisms.

The Circadian Activity of the HPI Axis in Developing Zebrafish Larvae

Zebrafish larva is considered as a suited model to understand homeostasis and stress regulation for diurnal animals (Alderman and Bernier, 2009; Alsop and Vijayan, 2009; Nesan et al., 2012; Ziv et al., 2013). Yet, the circadian cortisol pattern and HPI axis activity in this model are unknown. Here we showed that the circadian rhythm of cortisol is established overtime and controlled by circadian environmental light cue. The increase of cortisol observed from late evening to early morning corresponds to the glucocorticoid circadian increase in human overnight and to the circadian fluctuation in rodents (Watts et al., 2004; Dimitrov et al., 2009). The sustained cortisol variation in larvae transferred into darkness (Figure 1C) further indicates that the cortisol rhythm is maintained by the internal circadian clock system. We note that while the cortisol fluctuation is abolished in light-deprived larvae (Figure 1D), the average daily cortisol levels in normal vs. light-deprived larvae do not differ from each other (data not shown). This suggests that light deprivation does not alter the normal development of the HPI axis.

Zebrafish larva at the stage of 6 dpf could be a suited model to study circadian-related properties of the HPA/I axis. Our data strongly suggest that the HPI axis activity in these larvae is tightly regulated by the intrinsic circadian clock. The circadian fluctuation of cortisol and the decrease of NPO crh from the late evening to early morning are robust and consistently observed in different genotypes including AB stain of wildtype, rx3 siblings and rx3 mutants in our work. In addition, the fact that these larvae responses to different environmental stimuli in a dose-dependent manner also supports the notion that the functionality of the HPI axis is well established (Yeh et al., 2013). This model could be further used to understand the circadian interactions between the HPI axis and other physiological parameters as it has been shown that the physiology and behaviors of 5–6 dpf larvae are also regulated under tight circadian clock control (Kazimi and Cahill, 1999; Whitmore et al., 2000; Hurd and Cahill, 2002; Cavallari et al., 2011).

NPO crh Fluctuation was Sustained when Cortisol Signaling was Diminished

A prominent function of glucocorticoids is to negatively regulate the upstream HPA axis components (Keller-Wood and Dallman, 1984; Kovács et al., 2000; Herman et al., 2012). The negative correlations between cortisol and NPO crh in this study were consistent with data from adult mammals (Watts, 1996; Watts et al., 2004). Our results from rx3 mutants and MIF treated larvae suggest that robust glucocorticoid fluctuation is not necessary to maintain NPO crh basal variation. This coincided with the studies in rodent in which PVN crh transcript variation is maintained after adrenalectomy both under basal and stress conditions (Watts et al., 2004; Shepard et al., 2005). The basal rhythm of NPO crh could be primarily driven by the SCN since the anatomical connection and functional interactions between the SCN and PVN were well documented in mammals (Moore and Eichler, 1972; Watts and Swanson, 1987; Watts et al., 1987; Buijs et al., 1993; Kalsbeek et al., 2012).

While the circadian cortisol increase did not drive the NPO crh decrease, the negative feedback from glucocorticoids to NPO crh has been suggested in zebrafish. We observed NPO crh decrease using dexamethasone treatment (data not shown) and others have shown it in adult zebrafish (Ziv et al., 2013). We observed that cortisol modulates the overall level but not the variation of the NPO crh under basal condition. It is worth to note that more works are needed to rigorously address if proper cortisol signaling is required to maintain the overall NPO crh level as our data from rx3 mutants is subjected to the function of rx3 on the forebrain development (Stigloher et al., 2006). Also, to understand how NPO crh is modulated using larval zebrafish, the connection between NPO and other regions of the brain including the the homologous structures of mammalian hippocampus and amygdala should be explored in this model organism (Tsigos and Chrousos, 2002).

In conclusion, we showed that the HPI axis is fully mature and tightly regulated through circadian light cues in 6 day-old larvae. We showed that the circadian-related properties of the HPI axis in zebrafish are shared with those of the HPA aixs in mammals. We showed that the robust daily NPO crh fluctuation can be maintained but the level of NPO crh is altered when the cortisol signaling is compromised. Thus, although the basal glucocorticoids change is correlated with the hypothalamic crh variation, the negative feedback of the HPI/HPA axis is not driving the hypothalamic crh basal variation in the diurnal zebrafish.

Funding

This work was supported by the Max Planck Society.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

I thank Soojin Ryu for supporting this study with funding and lab space. This work was supported by Max Planck Society PhD and postdoc fellowship. I thank Thomas Dickmeis for experimental suggestions and material sharing. I thank Jose Arturo Guiterrez-Triana for critical reading of the manuscript; members of Ryu lab for comments; Regina Singer for technical assistance; Gabi Shoeman, Regina Singer and Angelika Schoell for expert fish care. This work was supported by the Max Planck Society.

References

Alderman, S. L., and Bernier, N. J. (2009). Ontogeny of the corticotropin-releasing factor system in zebrafish. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 164, 61–69. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2009.04.007

Alsop, D., and Vijayan, M. M. (2009). Molecular programming of the corticosteroid stress axis during zebrafish development. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 153, 49–54. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2008.12.008

Andrews, M. H., Wood, S. A., Windle, R. J., Lightman, S. L., and Ingram, C. D. (2012). Acute glucocorticoid administration rapidly suppresses basal and stress-induced hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis activity. Endocrinology 153, 200–211. doi: 10.1210/en.2011-1434

Buijs, R. M., Kalsbeek, A., van Der Woude, T. P., van Heerikhuize, J. J., and Shinn, S. (1993). Suprachiasmatic nucleus lesion increases corticosterone secretion. Am. J. Physiol. 264, R1186–R1192.

Cavallari, N., Frigato, E., Vallone, D., Fröhlich, N., Lopez-Olmeda, J. F., Foà, A., et al. (2011). A blind circadian clock in cavefish reveals that opsins mediate peripheral clock photoreception. PLoS Biol. 9:e1001142. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001142

Charmandari, E., Tsigos, C., and Chrousos, G. (2005). Endocrinology of the stress response. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 67, 259–284. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.67.040403.120816

Chrousos, G. P. (2009). Stress and disorders of the stress system. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 5, 374–381. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2009.106

Clark, K. J., Boczek, N. J., and Ekker, S. C. (2011). Stressing zebrafish for behavioral genetics. Rev. Neurosci. 22, 49–62. doi: 10.1515/rns.2011.007

de Kloet, E. R., Joëls, M., and Holsboer, F. (2005). Stress and the brain: from adaptation to disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 6, 463–475. doi: 10.1038/nrn1683

Dickmeis, T., Lahiri, K., Nica, G., Vallone, D., Santoriello, C., Neumann, C. J., et al. (2007). Glucocorticoids play a key role in circadian cell cycle rhythms. PLoS Biol. 5:e78. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050078

Dimitrov, S., Benedict, C., Heutling, D., Westermann, J., Born, J., and Lange, T. (2009). Cortisol and epinephrine control opposing circadian rhythms in T cell subsets. Blood 113, 5134–5143. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-11-190769

Griffiths, B. B., Schoonheim, P. J., Ziv, L., Voelker, L., Baier, H., and Gahtan, E. (2012). A zebrafish model of glucocorticoid resistance shows serotonergic modulation of the stress response. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 6:68. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2012.00068

Hauptmann, G., and Gerster, T. (1994). 2-color whole-mount in-situ hybridization to vertebrate and drosophila embryos. Trends Genet. 10:266.

Herget, U., Wolf, A., Wullimann, M. F., and Ryu, S. (2014). Molecular neuroanatomy and chemoarchitecture of the neurosecretory preoptic-hypothalamic area in zebrafish larvae. J. Comp. Neurol. 522, 1542–1564. doi: 10.1002/cne.23480

Herman, J. P., McKlveen, J. M., Solomon, M. B., Carvalho-Netto, E., and Myers, B. (2012). Neural regulation of the stress response: glucocorticoid feedback mechanisms. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 45, 292–298. doi: 10.1590/S0100-879X2012007500041

Hurd, M. W., and Cahill, G. M. (2002). Entraining signals initiate behavioral circadian rhythmicity in larval zebrafish. J. Biol. Rhythms 17, 307–314. doi: 10.1177/074873002129002618

Jeanneteau, F. D., Lambert, W. M., Ismaili, N., Bath, K. G., Lee, F. S., Garabedian, M. J., et al. (2012). BDNF and glucocorticoids regulate corticotrophin-releasing hormone (CRH) homeostasis in the hypothalamus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 1305–1310. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1114122109

Kalsbeek, A., van Der Spek, R., Lei, J., Endert, E., Buijs, R. M., and Fliers, E. (2012). Circadian rhythms in the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 349, 20–29. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2011.06.042

Kazimi, N., and Cahill, G. M. (1999). Development of a circadian melatonin rhythm in embryonic zebrafish. Brain Res. Dev. Brain Res. 117, 47–52. doi: 10.1016/S0165-3806(99)00096-6

Keller-Wood, M. E., and Dallman, M. F. (1984). Corticosteroid inhibition of ACTH secretion. Endocr. Rev. 5, 1–24. doi: 10.1210/edrv-5-1-1

Kovács, K. J., Földes, A., and Sawchenko, P. E. (2000). Glucocorticoid negative feedback selectively targets vasopressin transcription in parvocellular neurosecretory neurons. J. Neurosci. 20, 3843–3852.

Laryea, G., Muglia, L., Arnett, M., and Muglia, L. J. (2015). Dissection of glucocorticoid receptor-mediated inhibition of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis by gene targeting in mice. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 36, 150–164. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2014.09.002

Laryea, G., Schütz, G., and Muglia, L. J. (2013). Disrupting hypothalamic glucocorticoid receptors causes HPA axis hyperactivity and excess adiposity. Mol. Endocrinol. 27, 1655–1665. doi: 10.1210/me.2013-1187

Lin, C. H., Tsai, I. L., Su, C. H., Tseng, D. Y., and Hwang, P. P. (2011). Reverse effect of mammalian hypocalcemic cortisol in fish: cortisol stimulates Ca2+ uptake via glucocorticoid receptor-mediated vitamin D3 metabolism. PLoS ONE 6:e23689. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023689

Liu, N. A., Huang, H., Yang, Z., Herzog, W., Hammerschmidt, M., Lin, S., et al. (2003). Pituitary corticotroph ontogeny and regulation in transgenic zebrafish. Mol. Endocrinol. 17, 959–966. doi: 10.1210/me.2002-0392

Liu, N. A., Jiang, H., Ben-Shlomo, A., Wawrowsky, K., Fan, X. M., Lin, S., et al. (2011). Targeting zebrafish and murine pituitary corticotroph tumors with a cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 8414–8419. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018091108

Löhr, H., and Hammerschmidt, M. (2011). Zebrafish in endocrine systems: recent advances and implications for human disease. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 73, 183–211. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-012110-142320

Löhr, H., Ryu, S., and Driever, W. (2009). Zebrafish diencephalic A11-related dopaminergic neurons share a conserved transcriptional network with neuroendocrine cell lineages. Development 136, 1007–1017. doi: 10.1242/dev.033878

Malkoski, S. P., and Dorin, R. I. (1999). Composite glucocorticoid regulation at a functionally defined negative glucocorticoid response element of the human corticotropin-releasing hormone gene. Mol. Endocrinol. 13, 1629–1644. doi: 10.1210/mend.13.10.0351

Moore, R. Y., and Eichler, V. B. (1972). Loss of a circadian adrenal corticosterone rhythm following suprachiasmatic lesions in the rat. Brain Res. 42, 201–206. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(72)90054-6

Muglia, L. J., Jacobson, L., Weninger, S. C., Luedke, C. E., Bae, D. S., Jeong, K. H., et al. (1997). Impaired diurnal adrenal rhythmicity restored by constant infusion of corticotropin-releasing hormone in corticotropin-releasing hormone-deficient mice. J. Clin. Invest. 99, 2923–2929. doi: 10.1172/JCI119487

Nesan, D., Kamkar, M., Burrows, J., Scott, I. C., Marsden, M., and Vijayan, M. M. (2012). Glucocorticoid receptor signaling is essential for mesoderm formation and muscle development in zebrafish. Endocrinology 153, 1288–1300. doi: 10.1210/en.2011-1559

Newton, R. (2000). Molecular mechanisms of glucocorticoid action: what is important? Thorax 55, 603–613. doi: 10.1136/thorax.55.7.603

Shepard, J. D., Liu, Y., Sassone-Corsi, P., and Aguilera, G. (2005). Role of glucocorticoids and cAMP-mediated repression in limiting corticotropin-releasing hormone transcription during stress. J. Neurosci. 25, 4073–4081. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0122-05.2005

Smith, G. W., Aubry, J. M., Dellu, F., Contarino, A., Bilezikjian, L. M., Gold, L. H., et al. (1998). Corticotropin releasing factor receptor 1-deficient mice display decreased anxiety, impaired stress response, and aberrant neuroendocrine development. Neuron 20, 1093–1102. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80491-2

Steenbergen, P. J., Richardson, M. K., and Champagne, D. L. (2011). The use of the zebrafish model in stress research. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 35, 1432–1451. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2010.10.010

Stigloher, C., Ninkovic, J., Laplante, M., Geling, A., Tannhäuser, B., Topp, S., et al. (2006). Segregation of telencephalic and eye-field identities inside the zebrafish forebrain territory is controlled by Rx3. Development 133, 2925–2935. doi: 10.1242/dev.02450

To, T. T., Hahner, S., Nica, G., Rohr, K. B., Hammerschmidt, M., Winkler, C., et al. (2007). Pituitary-interrenal interaction in zebrafish interrenal organ development. Mol. Endocrinol. 21, 472–485. doi: 10.1210/me.2006-0216

Tsigos, C., and Chrousos, G. P. (2002). Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, neuroendocrine factors and stress. J. Psychosom. Res. 53, 865–871. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(02)00429-4

van Der Laan, S., de Kloet, E. R., and Meijer, O. C. (2009). Timing is critical for effective glucocorticoid receptor mediated repression of the cAMP-induced CRH gene. PLoS ONE 4:e4327. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004327

Watts, A. G. (1996). The impact of physiological stimuli on the expression of corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) and other neuropeptide genes. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 17, 281–326. doi: 10.1006/frne.1996.0008

Watts, A. G., and Swanson, L. W. (1987). Efferent projections of the suprachiasmatic nucleus: II. studies using retrograde transport of fluorescent dyes and simultaneous peptide immunohistochemistry in the rat. J. Comp. Neurol. 258, 230–252. doi: 10.1002/cne.902580205

Watts, A. G., Swanson, L. W., and Sanchez-Watts, G. (1987). Efferent projections of the suprachiasmatic nucleus: I. studies using anterograde transport of phaseolus vulgaris leucoagglutinin in the rat. J. Comp. Neurol. 258, 204–229. doi: 10.1002/cne.902580204

Watts, A. G., Tanimura, S., and Sanchez-Watts, G. (2004). Corticotropin-releasing hormone and arginine vasopressin gene transcription in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus of unstressed rats: daily rhythms and their interactions with corticosterone. Endocrinology 145, 529–540. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-0394

Weger, B. D., Weger, M., Nusser, M., Brenner-Weiss, G., and Dickmeis, T. (2012). A chemical screening system for glucocorticoid stress hormone signaling in an intact vertebrate. ACS Chem. Biol. 7, 1178–1183. doi: 10.1021/cb3000474

Westerfield, M. (2000). The Zebrafish Book. A Guide for the Laboratory Use of Zebrafish (Danio Rerio). Eugene, OR: University of Oregon Press.

Whitmore, D., Foulkes, N. S., and Sassone-Corsi, P. (2000). Light acts directly on organs and cells in culture to set the vertebrate circadian clock. Nature 404, 87–91. doi: 10.1038/35003589

Yeh, C. M., Glöck, M., and Ryu, S. (2013). An optimized whole-body cortisol quantification method for assessing stress levels in larval zebrafish. PLoS ONE 8:e79406. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0079406

Keywords: the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal/interrenal axis, neurosecretory preoptic area, cortisol, corticortropin-releasing hormone, circadian variation, negative feedback, diurnal zebrafish larva

Citation: Yeh C-M (2015) The Basal NPO crh Fluctuation is Sustained Under Compromised Glucocorticoid Signaling in Diurnal Zebrafish. Front. Neurosci. 9:436. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2015.00436

Received: 29 August 2015; Accepted: 30 October 2015;

Published: 02 December 2015.

Edited by:

James A. Carr, Texas Tech University, USAReviewed by:

Nicholas J. Bernier, University of Guelph, CanadaAllan V. Kalueff, ZENEREI Institute, USA;

Guangdong Ocean University, China;

St. Petersburg State University, Russia

Copyright © 2015 Yeh. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Chen-Min Yeh, Y3llaEBzYWxrLmVkdQ==

Chen-Min Yeh

Chen-Min Yeh