- Department of Industrial Psychology and People Management, College of Business and Economics, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, South Africa

Introduction: This study aimed to design a structured, HR-led training programme to enhance employee well-being in the workplace, addressing the global decline in engagement and mental health.

Methods: Conducted within a South African organization, the intervention followed a three-phase qualitative design: a pilot training session introducing 25 evidence-based wellbeing constructs, a focus group discussion (FGD) to prioritize constructs based on participant relevance, and thematic analysis to co-develop the final content.

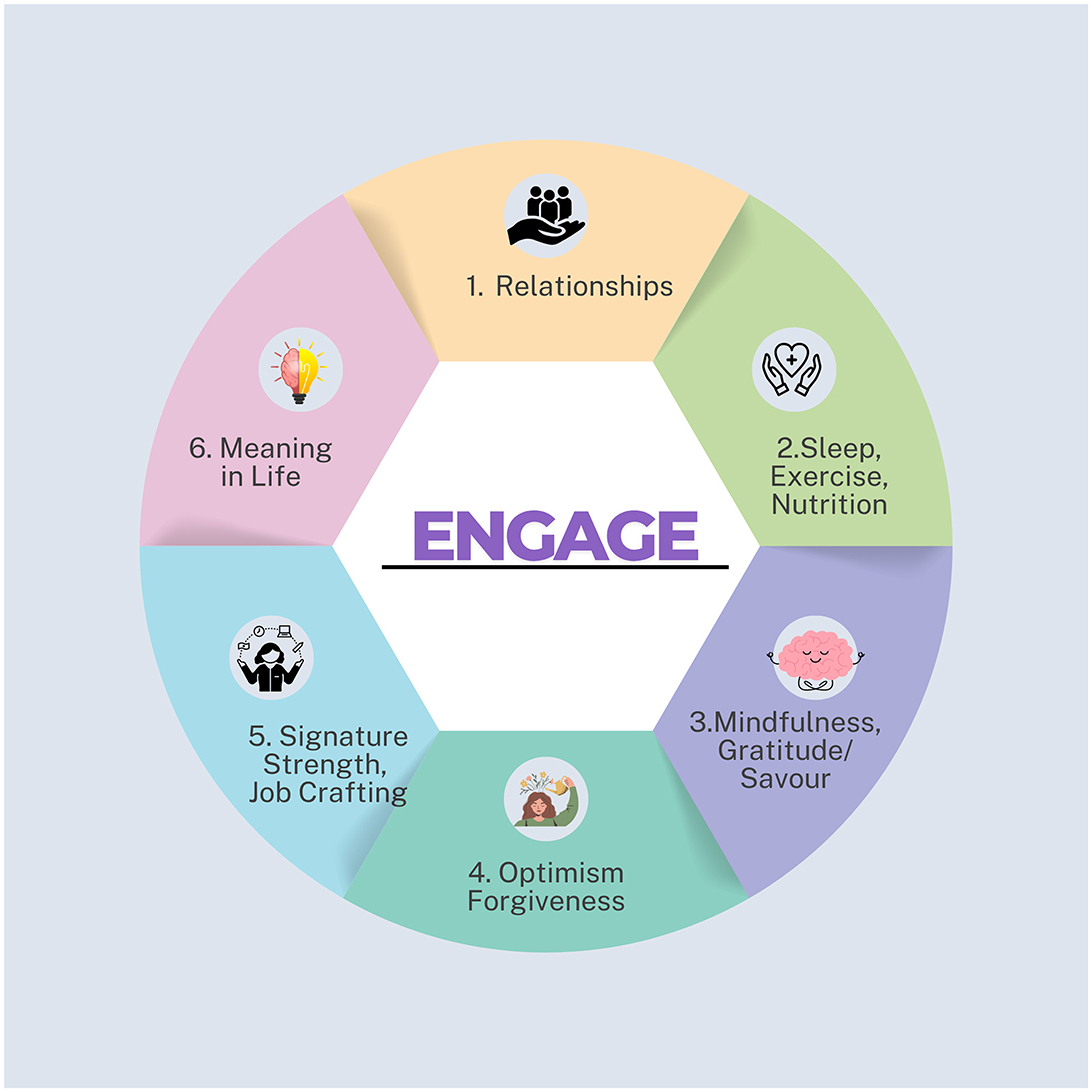

Results: Participants identified six priority constructs—relationships, physical health (sleep, nutrition, exercise), mental health (mindfulness, gratitude, optimism), Job health (character strengths, job crafting) and meaning in life—which formed the foundation of the ENGAGE training programme. Delivered in a 2-day classroom format, the programme resulted in significant improvements in mental wellbeing, as measured by the WEMWBS, detailed in a separate publication.

Discussion: This research demonstrates that HR professionals, even without clinical expertise, can co-create and deliver impactful wellbeing interventions. The participatory design ensured cultural relevance, high engagement, and strong practical applicability. Unlike fixed, top-down models, the ENGAGE framework reflects employee voice and workplace realities, contributing a locally grounded, evidence-informed approach to the field of workplace wellbeing. It offers both conceptual and practical value for HR practitioners and researchers aiming to enhance wellbeing through structured, scalable interventions.

1 Introduction

In recent years, mental and psychological wellbeing has emerged as a critical concern in workplace contexts, with challenges increasingly visible across both global and national landscapes. In 2015, more than 300 million people experienced depression, a similar number suffered from anxiety disorders, and over 800,000 lives were lost to suicide annually—making it the second leading cause of death among young people (WHO, 2024). Alarmingly, a recent Lancet study involving over 150,000 respondents across 29 countries (spanning high-, middle-, and low-income regions) estimated that nearly half the population is at risk of developing at least one mental health disorder by age 75 (McGrath et al., 2023). These figures have been further exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, global warming, and geopolitical conflicts (Moitra et al., 2023), while the pervasive use of the internet and social media has been linked to declines in psychological wellbeing (Braghieri et al., 2022; Suárez Álvarez and Vicente, 2024).

In this context, Human Resource (HR) professionals are uniquely positioned to play a strategic role in promoting workplace wellbeing. Traditionally, Human Resource Management (HRM) has prioritized firm performance over employee welfare, often relegating wellbeing to a secondary concern (Guest, 2017; Saridakis et al., 2017). Although psychological wellbeing has been shown to be a stronger predictor of work performance than physical health (Ford et al., 2011), HRM strategies have largely neglected this dimension in favor of business outcomes. As a result, structured and contextually relevant HR-led wellbeing interventions remain critically underdeveloped—particularly in non-Western contexts such as South Africa.

There is, however, growing evidence that workplace interventions can effectively enhance wellbeing, reduce stress, and improve employee engagement. Meta-analyses have demonstrated that programmes targeting mindfulness, optimism, gratitude, meaning, and resilience yield significant benefits for both individuals and organizations (Carr et al., 2020, 2024; Donaldson et al., 2019; Saurombe and Barkhuizen, 2022). Importantly, such interventions do not always require clinical expertise; evidence suggests that even trained non-clinical personnel and volunteers can successfully deliver wellbeing programmes (Krekel et al., 2021). Moreover, economic analyses indicate that investments in employee wellbeing yield substantial returns through reduced healthcare costs, absenteeism, and presenteeism (Milligan-Saville et al., 2017).

This study responds to these gaps by developing and evaluating a structured, HRM-led training programme designed to enhance employee wellbeing in the workplace. While previous research has primarily tested single-component interventions through randomized controlled trials (Bolier et al., 2013; Donaldson et al., 2019), this study adopts a multi-component approach and examines its effectiveness within a real-world organizational setting.

2 A brief literature review

2.1 Wellbeing concerns at the workplace

Recent global data highlight the urgent need for systemic action on workplace mental health and wellbeing. Gallup's (2024) State of the Global Workplace report reveals that fewer than 25% of employees worldwide are actively engaged, with 62% disengaged and 15% actively disengaged. Only 34% of workers report thriving, while the remaining 66% are either struggling (58%) or suffering (8%). Moreover, daily negative emotions are prevalent, with 41% of employees reporting stress, 21% anger, 22% sadness, and 20% loneliness.

In Sub-Saharan Africa, the trends are equally concerning. Engagement levels are particularly low, with only 20% of employees actively engaged and 17% actively disengaged. Stress (48%), sadness (28%), anger (25%), and loneliness (26%) are widespread. Life evaluation data indicates that just 17% of employees consider themselves to be thriving, while 74% report struggling. Additionally, 75% of employees are either actively looking for or open to new job opportunities (Gallup, 2024). These figures signal a substantial risk of attrition, burnout, and reduced organizational performance if wellbeing remains unaddressed.

These concerns are especially pronounced among younger generations. The Deloitte (2024) Gen Z and Millennial Survey, spanning over 22,800 respondents across 44 countries, identifies mental health as a top issue among younger workers. Forty percent of Gen Z respondents and 35% of millennials report feeling stressed most of the time, with only half rating their mental health positively. Workplace factors such as lack of recognition, excessive workloads, low task completion capacity, limited purpose, and social exclusion are key contributors.

Addressing these challenges is not only a moral imperative but also an economic one. Baicker et al. (2010) found that for every dollar spent on employee wellness programmes, organizations save $3.27 in medical costs and $2.73 in absenteeism. Evidence further suggests that workplace-based mental health interventions can reduce symptoms of depression and anxiety while enhancing engagement and productivity (Gartlehner et al., 2016; Joyce et al., 2016). Organizations that assess employee wellbeing proactively and invest in evidence-based interventions—such as stress management, psychological support, and structured training—are better positioned to foster a healthy, productive, and resilient workforce.

2.2 Wellbeing gaps globally and in South Africa

Despite the growing global interest in wellbeing and positive psychology, most intervention studies remain geographically concentrated in Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic (WEIRD) countries. Hendriks et al. (2019) report that over half of all wellbeing interventions have been conducted in North America (53.3%) and a third in Europe (34.1%), with Australia and New Zealand contributing 6.3%. In contrast, developing countries such as South Africa account for only 0.2% of these studies. This disproportion underscores a critical lack of empirical research in non-Western and lower-income settings, raising concerns about the generalizability and cultural relevance of existing intervention models.

The scarcity of workplace-based wellbeing interventions is particularly notable. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) by Weiss et al. (2016) identified only 27 psychological wellbeing interventions globally, of which just two were workplace-based. However, neither study included engagement or stress as outcome variables. One study by Addley et al. (2014) focused on routine health screenings rather than psychological change, while the other (Page and Vella-Brodrick, 2013) had a limited sample size of 12 participants, constraining its generalizability. These findings point to a significant gap in rigorous, workplace-specific interventions that target key constructs such as engagement, stress, and subjective wellbeing.

A similar geographical imbalance is evident in reviews of positive psychology interventions (PPIs). In their review of 863 studies, Kim et al. (2018) found only 25 publications from the African continent—highlighting a substantial research deficit across the region. Guse (2022), in a scoping review of PPIs conducted in Africa, identified only 23 studies aimed at enhancing wellbeing or building positive psychological resources. Notably, none were conducted in workplace settings or examined outcomes such as employee stress or engagement. Guse (2022)) strongly recommended the development of culturally adapted interventions that align with African realities.

Taken together, these findings demonstrate a clear need for contextually relevant, evidence-based wellbeing programmes in African workplaces. This study directly addresses this gap by designing and evaluating a culturally informed, HR-led training intervention tailored to the South African organizational context.

2.3 Role of human resources managers in wellbeing interventions at the workplace

Over the past three decades, the field of human resource management (HRM) has evolved significantly, with substantial progress in clarifying its strategic role and its contribution to organizational performance (Guest, 2017; Saridakis et al., 2017; Saurombe et al., 2022). However, the dominant emphasis on the HRM–performance link has often marginalized employee wellbeing as a core concern. A meta-analysis of eight longitudinal studies found a consistent but moderate relationship between HRM practices and firm performance, suggesting that HR's strategic impact may be overestimated when wellbeing is excluded from the equation (Saridakis et al., 2017). While organizations have gained on performance indicators, employee engagement and wellbeing have declined—globally, only 23% of employees are engaged, and stress-related disorders are on the rise (Gallup, 2024; Quick and Henderson, 2016).

These developments call for a reorientation of HRM to integrate wellbeing as both an ethical priority and a performance-enhancing strategy. Borkowska and Czerw (2022) advocate for reflective, evidence-based, and data-informed HR practices to create supportive and psychologically healthy workplaces.

Emerging evidence suggests that wellbeing interventions can be effectively delivered by non-clinical facilitators. For instance, a randomized controlled trial by Krekel et al. (2021) demonstrated that community-based volunteers—without formal psychological training—successfully delivered the Exploring What Matters course, which significantly improved participants' life satisfaction, social trust, and reduced symptoms of anxiety and depression, with effects sustained 2 months post-intervention. These findings suggest that structured, non-clinician-led interventions can be impactful when appropriately designed and supported.

In the workplace, HR managers are particularly well positioned to lead such interventions. Unlike external facilitators, HR professionals are embedded within the organizational system, possess contextual knowledge, and have direct access to employees (Elufioye et al., 2024). This embeddedness enables them to tailor interventions to the unique challenges and dynamics of their organizations, potentially increasing relevance, uptake, and sustainability.

Despite these advantages, the literature remains limited in documenting the effectiveness of HR-led wellbeing programmes. Most existing research has focused on interventions led by clinicians or implemented in community settings. This study addresses this gap by designing and evaluating a structured, HR-led training programme aimed at enhancing employee wellbeing. By assessing its feasibility and impact in a real-world organizational context, the study contributes practical insights for integrating wellbeing into core HRM strategy.

2.4 Constructs that can enhance the wellbeing of employees

Multiple meta-analyses have established that psychological wellbeing interventions can significantly enhance mental health outcomes and reduce depressive symptoms (Bolier et al., 2013; Hendriks et al., 2020; Sin and Lyubomirsky, 2009). Although recent work suggests that such interventions may have only modest advantages over active comparators like group-based cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT; Lim and Tierney, 2022), they remain valuable due to their scalability and accessibility in workplace settings.

This section synthesizes key constructs drawn from the wellbeing literature that were reviewed prior to the intervention design. These constructs were subsequently introduced during focus group discussions (FGDs), where South African employees were invited to select those most relevant to their lived experiences. This approach ensured that the intervention was not only theory-informed but also culturally responsive and contextually grounded.

2.4.1 Mindfulness

Mindfulness practices, which cultivate present-moment awareness and non-judgmental attention, have been shown to improve employee wellbeing, job satisfaction, and psychological functioning (Aikens et al., 2014; Hülsheger et al., 2013; Kersemaekers et al., 2018). Online mindfulness interventions have demonstrated similar benefits, reducing stress and burnout while enhancing focus, empathy, and interpersonal connection (Good et al., 2016).

2.4.2 Gratitude

Defined as the appreciation of benefits received from others, gratitude has a robust association with psychological wellbeing (Tolcher et al., 2024). Numerous studies confirm the effectiveness of gratitude-based interventions in improving life satisfaction, emotional resilience, and mental health (Boggiss et al., 2020; Bohlmeijer et al., 2021; Cregg and Cheavens, 2021; Geier and Morris, 2022; Koay et al., 2020; Locklear et al., 2021).

2.4.3 Optimism and hope

Positive cognitive orientations such as hope and optimism correlate strongly with enhanced wellbeing and lower pain perception (Bazargan-Hejazi et al., 2023; Shanahan et al., 2021). These traits are particularly relevant in workplace contexts where uncertainty and goal striving are common.

2.4.4 Relationships and social connection

Strong interpersonal relationships are among the most powerful predictors of wellbeing and longevity (Andersen et al., 2021; Diener and Seligman, 2002; Waldinger and Schulz, 2023b). Social support, friendship, and quality relationships have been linked to slower biological aging (Bourassa et al., 2020), higher life satisfaction (Helliwell et al., 2025) and lower stress. Marriage and long-term partnerships also show consistent associations with higher happiness levels and economic stability (Hu et al., 2024; Myers, 2001).

2.4.5 Character strengths

The VIA framework (Peterson and Seligman, 2004) identifies 24 character strengths that contribute to flourishing. Interventions that help individuals identify and apply their signature strengths have been shown to increase happiness and reduce depressive symptoms (Bates-Krakoff et al., 2022; Harzer and Ruch, 2013; Seligman et al., 2005). When individuals use their core strengths at work, they report greater satisfaction, meaning, and engagement (Dolev-Amit et al., 2020).

2.4.6 Job crafting

Job crafting—the process of actively shaping one's job to improve alignment with skills, values, and interests—is associated with improved engagement and mental wellbeing (Demerouti, 2014; de Devotto et al., 2020; Wrzesniewski and Dutton, 2001). Empirical research in both Western and African contexts supports its role in improving motivation, meaning, and performance (Dhanpat, 2019; Holman et al., 2024).

2.5 Integrating constructs through participatory design

This literature review formed the foundation for a participatory co-design process, in which employees engaged with the constructs during the FGD phase. Participants reflected on each construct's relevance and feasibility in their personal and organizational context, which informed the final selection of modules for the HR-led wellbeing programme. By combining global evidence with local insights, the intervention was tailored to reflect both psychological science and contextual relevance—an essential step for sustainable impact in South African workplaces.

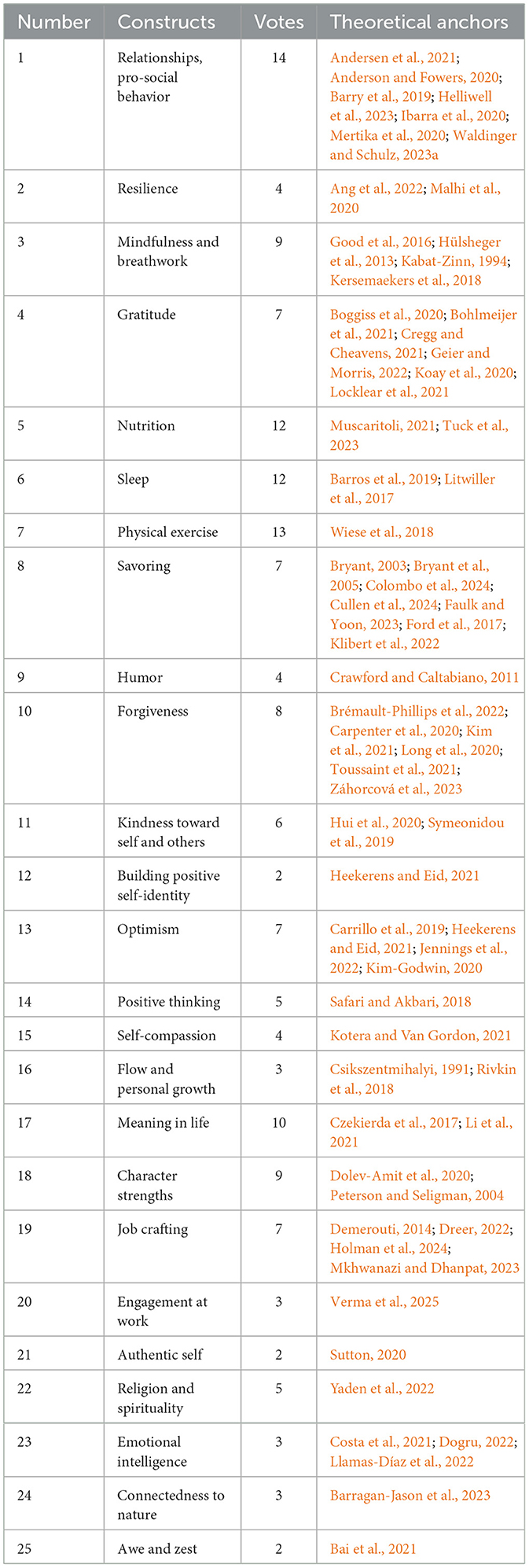

Owing to article length constraints, we were only able to elaborate a handful of the most prominent constructs above; the complete set of 25 constructs, together with their theoretical anchors and FGD vote tallies, is presented in Table 3 to show how participant preferences directly shaped the final module selection.

2.6 Theoretical model for HR-led wellbeing interventions

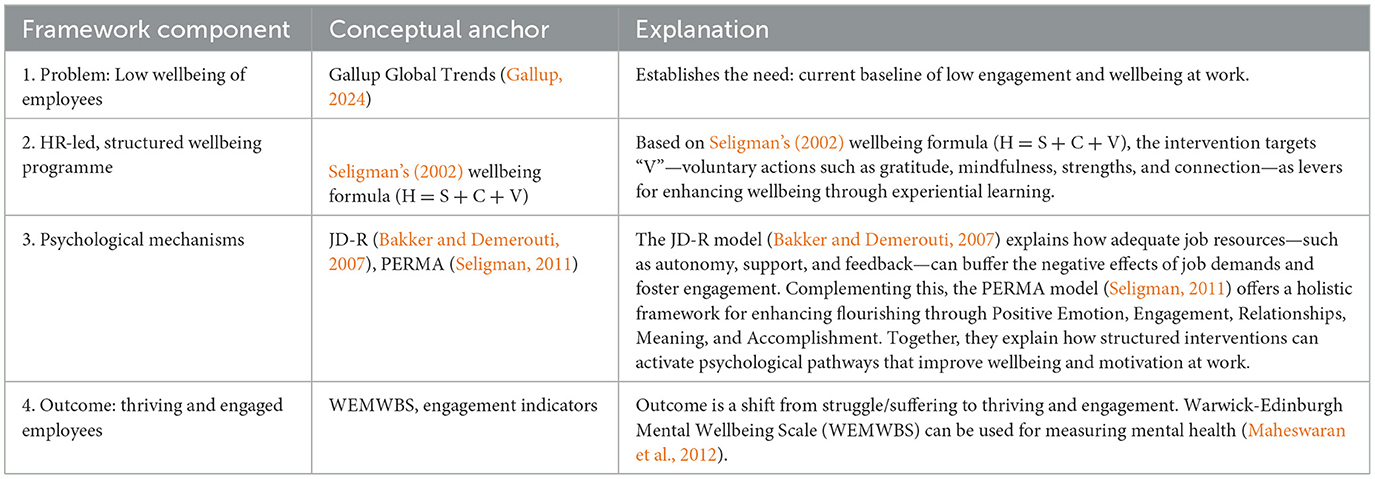

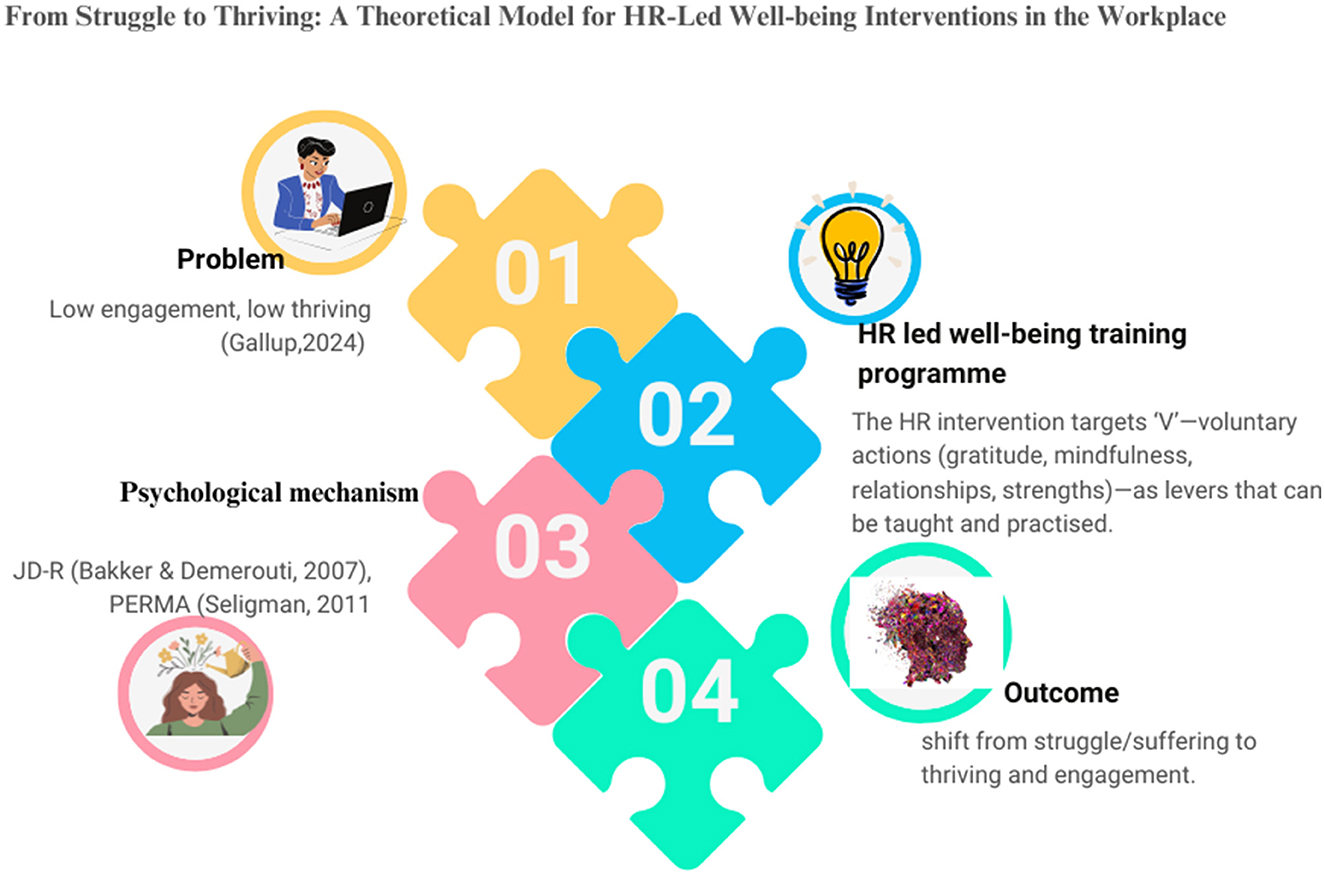

The theoretical framework underpinning this study is summarized in Table 1 and visually depicted in Figure 1. It integrates established theories with global workplace data to illustrate the pathway from low employee engagement to thriving and wellbeing through an HR-led intervention.

Figure 1. From struggle to thriving: a theoretical model for HR interventions (authors' own construction).

Grounded in Gallup's (2024) findings on widespread disengagement, the framework positions HR as a key enabler of change by targeting voluntary wellbeing behaviors—aligned with Seligman's (2002) happiness formula. The intervention mechanisms are informed by the Job Demands-Resources (JD-R) model and the PERMA framework, both of which explain how job resources and psychological drivers contribute to flourishing. The framework supports the design of the HR training programme and justifies the study's focus on experiential, strengths-based activities. It also clarifies the expected outcome: measurable improvements in employee wellbeing and engagement.

3 Methodology

This study employed a qualitative intervention research design to develop a structured, HR-led training programme aimed at enhancing workplace wellbeing. Informed by best practices in intervention development (Creswell and Creswell, 2022), the design process unfolded in three iterative phases: (1) a literature review to identify evidence-based wellbeing constructs, (2) a pilot training session to introduce and test these constructs to and with employees, and (3) a focus group discussion (FGD) to refine the programme based on participant insights. The intervention was implemented in a South African pharmaceutical company, allowing the training to be adapted to the cultural and organizational context.

3.1 Phase 1: construct selection through literature review

A comprehensive literature review was conducted to identify wellbeing constructs with empirical support for improving psychological wellbeing and workplace functioning. Constructs such as mindfulness, gratitude, meaning in life, optimism, forgiveness, and job crafting were selected based on their relevance to workplace outcomes and established efficacy in prior studies (Appiah et al., 2021; Kushlev et al., 2017; Sun et al., 2024). These constructs served as the foundation for the pilot training content.

3.2 Phase 2: pilot testing and construct validation

A 4-h pilot training session was conducted with 19 purposively selected employees. Participants represented a broad range of job functions, grades, and demographic profiles to ensure the intervention design was inclusive and reflective of diverse workplace perspectives. The training introduced each construct through experiential activities, multimedia resources, and reflective exercises. This phase aimed to assess participant engagement, conceptual clarity, and the perceived relevance of the constructs in the South African workplace context.

3.3 Phase 3: focus group discussion for construct refinement

Immediately following the pilot, a structured focus group discussion was held with the same participants to gather feedback on the training content. Employees were encouraged to reflect individually and then share the three constructs they found most impactful. Their feedback was documented, categorized, and thematically analyzed to identify shared priorities and contextual insights (Page and Vella-Brodrick, 2013; Van Zyl et al., 2019). This participatory process allowed employees to co-design the final structure of the intervention, later branded as the ENGAGE programme.

By integrating evidence-based content with employee-driven refinement, the study ensured that the final intervention was both theoretically grounded and culturally responsive—enhancing its potential for relevance, uptake, and impact within the workplace.

3.4 Research approach and philosophy

This study employed a qualitative case study approach to design a context-specific HR-led training intervention aimed at enhancing employee wellbeing. Qualitative research was appropriate given the exploratory aim of identifying which wellbeing constructs resonate most within a real-world organizational setting, allowing participants' lived experiences to shape the content of the intervention. The case study design enabled in-depth engagement with a single organization in South Africa, making it possible to tailor the programme to its unique cultural and workplace realities.

The study adopted a constructivist ontological stance, acknowledging that wellbeing is a socially constructed and context-dependent phenomenon (Creswell and Poth, 2018). Employees' perceptions and narratives were treated as valid sources of knowledge, shaped by their interactions, cultural norms, and organizational environment. From an interpretivist epistemological perspective, knowledge was co-constructed through dialogue during pilot training and focus group discussions (FGDs), emphasizing meaning-making and participant voice (Lincoln and Guba, 1985). This alignment of philosophy and methodology allowed the research to yield actionable insights grounded in both theory and the lived experiences of employees, ensuring that the resulting intervention was both evidence-informed and contextually relevant.

3.5 Research participants and sampling

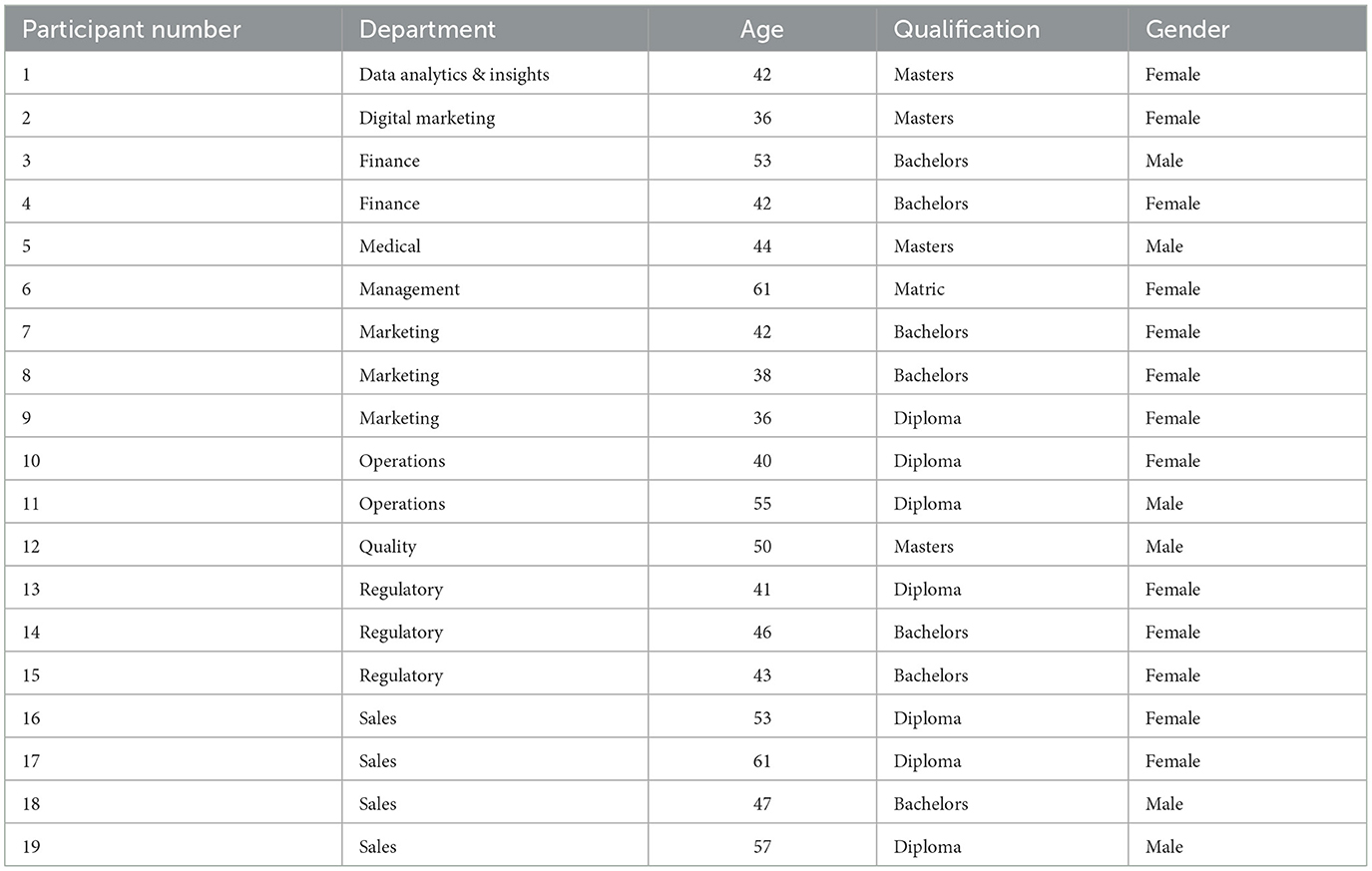

Participants were selected from a South African pharmaceutical company using purposive sampling, with the aim of capturing a diverse range of workplace perspectives. A total of 25 employees were invited (from a workforce of 108), of whom 19 participated in both the pilot training and the follow-up focus group discussion. Participants were chosen based on key demographic and professional criteria, including job grade, function, gender, and race, to ensure broad representation across departments.

This selection strategy was intended to surface varied experiences and insights relevant to workplace wellbeing. By incorporating employees from different roles and backgrounds, we ensured that the intervention design was informed by diverse workplace realities, enhancing both cultural sensitivity and practical relevance. The HR team of the pharmaceutical company coordinated logistics and invitations, and participation was voluntary. The final sample size was sufficient for qualitative exploration and co-design within a single-organization case study.

Table 2 presents the demographic and professional characteristics of the study participants, illustrating the diversity in departmental representation, age, qualification, and gender.

3.6 Data collection

A 4-h in-person pilot training session was held at the South African offices of a pharmaceutical company, introducing 25 evidence-based wellbeing constructs through multimedia content. This was followed by a focus group discussion (FGD) with 19 participants to identify and prioritize the most relevant constructs for the final intervention. The FGD, facilitated by the researcher using open-ended prompts and individual reflection, encouraged participants to list and discuss the constructs they found most impactful. Ideas were recorded on a whiteboard, thematically grouped, and then ranked through voting. Constructs such as relationships, mindfulness, sleep, and physical health emerged as common priorities. Table 3 presents the voting outcomes, while the thematic variations—including less emphasized constructs like awe and zest—provided depth for refining the programme. The final ENGAGE model was co-developed based on six constructs that reflected both theoretical grounding and employee relevance.

Table 3. Voting outcomes for wellbeing constructs prioritized by participants (author's own compilation).

3.7 Data trustworthiness

To ensure the rigor and trustworthiness of the qualitative phase in developing the HR training programme, the study applied the criteria of credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability as outlined by Lincoln and Guba (1985).

Credibility was enhanced through methodological triangulation, combining data from a literature review, a pilot training session, and a focus group discussion (FGD). This convergence of sources helped verify the relevance and resonance of selected wellbeing constructs. Participant checking occurred informally during the delivery of the actual training sessions that followed the FGD, enabling participants to validate whether the final training themes accurately reflected their earlier inputs.

Transferability was supported by the use of rich, thick description—particularly in detailing participant demographics, the training context, and the organizational environment—enabling readers to assess the applicability of findings to similar workplace settings. Negative or discrepant responses were documented and considered, allowing for a nuanced and balanced interpretation of the data.

Dependability was ensured through consistent documentation of the research process and decisions. The researcher maintained a reflexive journal using a mobile application to track thoughts, insights, and possible biases throughout the study. Collaboration with the company's training and HR managers during programme design helped ensure alignment with participant feedback and increased internal consistency.

Confirmability was reinforced by maintaining a transparent audit trail of research steps, decisions, and analytical procedures. Prolonged engagement with participants during the intervention development phase further contributed to a deeper understanding of the workplace context and reduced the risk of superficial interpretation.

Collectively, these strategies ensured that the qualitative research process was systematic, transparent, and aligned with established standards for qualitative trustworthiness.

3.8 Data analysis

FGD data were analyzed using thematic analysis, following Braun and Clarke's (2006, 2022) six-phase framework. The researcher manually reviewed handwritten notes, whiteboard summaries, and Excel-based inputs to gain familiarity with the data and conduct initial coding. Codes were clustered into broader categories that reflected shared meanings across participants' responses. Themes were then refined for clarity and internal coherence, ensuring they captured key insights relevant to the intervention's development. Direct participant quotes were used to validate interpretations and preserve authenticity. The final themes guided the selection of wellbeing constructs incorporated into the ENGAGE training programme.

3.9 Ethical considerations

This study complied with ethical guidelines for human participant research and received approval from the University of Johannesburg's Research Ethics Committee [Ethics Clearance Code: IPPM-2022-618(D)]. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants, who were informed of the study's purpose, voluntary nature, and their right to withdraw at any time without consequence.

Confidentiality was maintained through anonymized responses, secure data storage, and exclusion of personally identifiable information. Although participants engaged in a group setting, they were advised not to disclose personal information, and all contributions were treated with strict confidentiality. Although the HR department facilitated logistics, they did not access any participant data or information provided during the research.

To minimize power imbalances, direct reports and supervisors were excluded, and cultural sensitivity was prioritized through the inclusion of locally relevant wellbeing constructs. The study also complied with South Africa's data protection regulations (as governed by the Protection of Personal Information Act), ensuring transparency, data security, and participant privacy.

4 Findings

This section presents the key findings from the focus group discussion (FGD) conducted immediately after the pilot training session. During the session, participants reflected on a comprehensive set of 25 wellbeing constructs introduced through multimedia-based learning. They were then asked to vote on the constructs they found most personally meaningful and professionally relevant to their workplace context.

The voting outcomes, along with participant insights and reflections, were used to refine and finalize the content of the HR wellbeing programme. The six most highly endorsed constructs were organized into thematic areas, which now form the foundation of the intervention. Table 3 (presented earlier) summarizes the vote distribution.

To visually represent the final model, Figure 2 illustrates the six interconnected components of the training programme (branded as ENGAGE) offering a holistic and participant-driven approach to enhancing workplace wellbeing.

4.1 Theme 1: relationship with friends and family

The relationship as a wellbeing enhancer was marked as the most important construct to be included in the training programme. Participants watched the TED Talk by Robert Waldinger about Harvard's adult development study. Most of the participants strongly supported this construct, as shown in the following quotes:

“The TED Talk made it clear to me how critical relationships are for long-term happiness. The speaker's insights from the Harvard study made me realise that strong social connections are directly linked to happiness and long life. This should definitely be a core part of our training” (Participant 6).

“I strongly believe that fostering meaningful relationships at work can improve our happiness and well-being. If we can learn ways and methods to strengthen our relationships with colleagues, I think it will make a noticeable impact on overall happiness while reducing stress” (Participant 7).

“I really feel sorry for the fact that many young people believe that wealth and fame are the most important life goals. I feel this with my own children and the influence of social media like TikTok and Instagram. This is really bad for children” (Participant 8).

4.2 Theme 2: sleep, exercise, and nutrition

The trainer shared multiple excerpts from Keep Sharp: Build a Better Brain at Any Age by author Sanjay Gupta regarding sleep, nutrition, and exercise. A TED Talk by Matthew Walker and Wendy Suzuki was also shared with participants to emphasize sleep and exercise. This is what participants had to say regarding this:

“While relationships are foundational, I believe sleep, exercise, and nutrition are crucial too. Some of the research from the book (of Sanjay Gupta) made it clear that these factors improve mood, reduce stress, and help us maintain a clear mind—qualities that are vital for daily well-being. In some ways, this is also ancient knowledge that we should eat more fruits and vegetables, exercise regularly and go to bed early. I guess most of our parents and Ugogos have been trying to teach us this, and now we are busy teaching the same to our kids” (Participant 2).

“I have personally experienced how much broken I am when I come to work with short sleep. Most of the day is spent in a low mood, and hardly anything gets done” (Participant 19).

“The TED Talk highlighted how even a single workout session can improve mood, which I found really motivating” (Participant 17).

4.3 Theme 3: mindfulness, gratitude, and savoring

The following section includes participant feedback on the inclusion of mindfulness, gratitude, and savoring as key constructs in the wellbeing training programme. These comments reflect participants' perspectives on how each practice could manage stress and enhance happiness and wellbeing.

“I found mindfulness to be a useful tool for reducing stress and improving productivity. I have taken a few sessions in the past with a previous company. It was an incredible, life-changing experience. I strongly recommend that we include mindfulness and company training on this subject” (Participant 4).

“We must practice gratitude. It is also an important part of our religion. Let me cite a quote from the bible-Give thanks in all circumstances, for this is God's will for you in Christ Jesus” (Participant 9).

“Learning about savouring made me realise how often I rush through my day without enjoying the small moments. I think we should club these ideas in one bucket as they are connected to each other” (Participant 1).

4.4 Theme 4: forgiveness and optimism

This section explores the role of forgiveness and optimism as essential constructs for enhancing wellbeing. Participants discussed the emotional benefits of letting go of resentment and adopting a positive outlook on life. Drawing on concepts like Christian teachings, the REACH model of forgiveness, and Seligman's work on learned helplessness, participants reflected on how these practices could help build resilience and foster a more constructive mindset. Their insights highlight the transformative power of forgiveness and optimism in personal growth and emotional wellbeing.

“We should include forgiveness as it is an important value in the Christian teaching. Father, forgive them, for they do not know what they are doing. I have personally felt the value of forgiving and moving on. I see forgiveness as a way to let go of the resentment that can otherwise destroy us emotionally” (Participant 8).

“I really liked the idea of The REACH model of forgiveness. It gives us practical steps to let go of past hurts. We should include this idea, which can significantly enhance our happiness” (Participant 12).

“I found the video which talked about the experiment Seligman did with dogs, where they learned helplessness after repeated negative experiences, was eye-opening. It made me realise how easy it is for us to fall into patterns of hopelessness if we don't consciously work on optimism” (Participant 13).

4.5 Theme 2: signature strength and job crafting

The following comments capture participants' reflections on the concepts of character strengths and job crafting after viewing two YouTube videos about job crafting and character strengths. These insights emphasize how aligning individual strengths with job roles can enhance personal happiness and work engagement.

“I like the idea of taking this test to find out my character strengths. We should go ahead with this” (Participant 14).

“This example in the video of the janitors in the hospital seeing their job as making positive changes in the lives of patients resonates with me. I agree with our boss (head of sales) that we should add both character strengths and job crafting and keep them as a point in the training. We should take this free test as a team and share results with each other so we can understand each other's strengths” (Participant 19).

4.6 Theme 6: meaning in life

After viewing Emily Esfahani Smith's TED Talk, participants shared their thoughts on the importance of having meaning in life. These insights underscore how cultivating purpose, connection, and a sense of contribution can create a more resilient and fulfilling approach to personal wellbeing. The following comments reflect participants' views on this:

“I was surprised to know suicide rate is so high in Japan, Korea and some of the developed countries. It is certainly linked to the fact that many in west have lost their religion and families are falling apart. Look at the data- young people are neither marrying nor having children. This will destroy the society in long term. What will they do with all the economic wealth? [The] TED talk was a good reminder that meaning is deeper than just seeking happiness” (Participant 16).

“As a Single mother, I find meaning in caring for my child; she is my world. Everything I do is for her and I am able to sleep peacefully every night thinking that I did well to take care of her. I would have been a lost cause if my daughter was not around. People unnecessarily align their lives to jobs. Jobs are important, but we need to be careful, too [not to make them the centre of our lives]” (Participant 7).

“Reflecting on the Top 5 Regrets of the Dying, it's clear that meaning in life often comes from choices aligned with our personal values. Regrets like not spending enough time with loved ones highlight the importance of living with intent and direction. We should certainly include this in training. This is especially true in our African culture, where Ubuntu is becoming a black tax for young generations” (Participant 9).

5 Discussion

The ENGAGE training programme was uniquely designed through a qualitative, participatory process involving direct input from employees, reflecting a bottom-up approach to wellbeing intervention development. To better situate ENGAGE within the broader landscape of existing wellbeing interventions, this section compares and contrasts its design with several well-established programmes that were developed and tested across diverse contexts. These include structured, theory-driven interventions such as the wellbeing programme by Kushlev et al. (2017), community-based models like Exploring What Matters by Krekel et al. (2021), culturally grounded programmes like the Inspired Life Programme in Ghana by Appiah et al. (2021), and digital interventions such as Happify by Parks et al. (2018). The comparative analysis highlights key differences and similarities in terms of programme goals, delivery formats, theoretical underpinnings, facilitator roles, participant engagement, and measurement strategies. This exercise not only provides a broader understanding of global wellbeing intervention designs but also underscores the contextual sensitivity, participatory ethos, and practical relevance that distinguish the ENGAGE programme in workplace settings.

5.1 Comparison with the wellbeing programme: Enhance

The Enhance wellbeing programme by Kushlev et al. (2017) followed a top-down, theory-driven structure based on positive psychology, CBT, and empirical wellbeing science. It was built around 10 predefined constructs grouped under Core Self, Experiential Self, and Social Self, delivered across 12 weeks, followed by a 3-month maintenance phase. The programme's structure and content were fixed and universal applied equally across all participants. In contrast, ENGAGE adopted a bottom-up, participatory design. It began with an extensive literature review and introduced 25 wellbeing constructs to the participants in a pilot session. Employees then co-developed the final training content through focus group discussions and a voting process to shortlist the most relevant constructs, ensuring cultural fit and practical relevance. This participatory method allowed ENGAGE to reflect employees' lived realities, prioritizing constructs like relationships, physical health (nutrition, sleep, exercise), and meaning in life. While ENHANCE emphasized theoretical consistency and longitudinal structure, ENGAGE prioritized customization, cultural contextualization, and employee ownership, thereby bridging academic insights with workplace realities in diverse cultural settings. Key distinctions between the two programmes are summarized in Supplementary material 1.

5.2 Comparison with the wellbeing programme: Exploring What Matters

Krekel et al.'s (2021) Exploring What Matters course is a manualized, community-based intervention led by lay volunteers, focused on broad life themes (e.g., kindness, meaning) across eight weekly sessions. ENGAGE, by contrast, is workplace-centered, tailored to corporate contexts and delivered in a single-day (or modular) format by HR, with constructs selected directly by employees for their job-related relevance (e.g., job crafting, workplace relationships). Both share a goal of scalable wellbeing enhancement, but ENGAGE's co-design ensures greater contextual specificity. Key distinctions between the two programmes are summarized in Supplementary material 2.

5.3 Comparison with the wellbeing programme: Inspired Life

The Inspired Life Programme by Appiah et al. (2021) was developed via community-based participatory research for rural Ghanaian adults, delivered weekly by trained psychology graduates, and embedded within the Medical Research Council (MRC) framework with small token incentives. ENGAGE similarly blends theory and participation but is designed for corporate professionals, led by HR, and uses employee-driven construct selection rather than community feedback via thematic mapping. While both emphasize cultural adaptation and skill building, ENGAGE prioritizes workplace applicability and voluntary, incentive-free engagement. Key distinctions between the two programmes are summarized in Supplementary material 3.

5.4 Comparison with a web-based intervention

Happify offers a fully digital, self-guided platform combining positive psychology, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), and mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR), with users receiving small monetary incentives for assessments (Parks et al., 2018). ENGAGE can be delivered in a hybrid in-person/online format facilitated by HR trainers. ENGAGE uses participant-voted constructs instead of algorithmic “tracks,” and foregoes financial incentives in favor of intrinsic, workplace-driven motivation. Both demonstrate scalable, evidence-based approaches, but ENGAGE's human facilitation and participatory ethos distinguish its contextual depth. Key distinctions between the two programmes are summarized in Supplementary material 4.

6 Practical implications: bridging research and practice in workplace mental health

Growing attention to workplace wellbeing has driven global discussions on mental health, emphasizing the need for structured, evidence-based interventions. At the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health (2016) summit, experts identified critical gaps in workplace mental health practices (The Luv U Project, 2017). They called for organizations to implement structured wellbeing strategies (Wu et al., 2021). Key recommendations included developing a workplace mental health framework, creating a scorecard to assess organizational wellbeing culture, recognizing exemplary companies and training HR leaders to support mental health.

Similarly, Wu et al. (2021) identified eight best practices, including leadership support, wellbeing policies, and outcome measurement, which informed the Carolyn C. Mattingly Award for Mental Health in the Workplace—a recognition programme for organizations excelling in workplace mental health initiatives. These studies collectively highlight a growing academic and policy-driven movement emphasizing the integration of mental health into HR strategies, leadership training, and data-driven assessment frameworks.

The ENGAGE training programme operationalizes these large-scale recommendations by embedding mental health and wellbeing into HRD and HRM strategies. First, ENGAGE aligns with the call for structured frameworks by ensuring mental health is central to organizational strategy rather than an add-on initiative. Second, it can incorporate a mental health scorecard approach by collecting non-clinical data through a cross-sectional study, assessing workplace wellbeing indicators such as stress levels, life satisfaction, engagement, and flourishing. This data-driven approach enables organizations to evaluate and refine their wellbeing culture. Lastly, ENGAGE addresses the need for leadership training by equipping HR professionals with the tools to foster engagement, reduce workplace stress, and create a psychologically safe environment.

By implementing ENGAGE training framework, organizations are not just responding to an academic discussion but actively contributing to a global shift toward structured, research-backed workplace mental health interventions. Just as leading experts advocate for comprehensive mental health training, ENGAGE translates these recommendations into practical, scalable action, ensuring organizations invest in employee wellbeing and long-term engagement.

7 Limitations and recommendations

This study presents important insights into the co-design and implementation of an HR-led wellbeing programme; however, certain limitations must be acknowledged. First, the intervention was developed and implemented in a single South African organization as part of a broader PhD intervention study. While the 2-day classroom training intervention (Quasi-Experimental, Supplementary material 5) yielded significant improvements in participants' mental wellbeing, as measured by the Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale (WEMWBS), these findings are reported in a separate publication (Shekhar et al., 2025). The current study focuses only on the qualitative design phase of the programme, as such, generalizability remains limited. Future applications should test the ENGAGE model across a broader range of industries, organizational cultures, and geographic contexts. Second, while the participatory design ensured cultural and contextual relevance, the absence of a comparative control group and long-term follow-up limits the ability to draw causal or sustained inferences. Future research should include multi-site trials, incorporate mixed-method evaluations, and explore digital or hybrid delivery formats to enhance both scalability and long-term impact.

8 Conclusion

This study demonstrated that HR-led, co-designed training interventions can meaningfully improve employee wellbeing by integrating evidence-based psychological constructs with contextual insights. The ENGAGE programme was developed through a participatory process that allowed employees to prioritize constructs most relevant to their lived experiences—such as relationships, physical health, mindfulness, gratitude, optimism, and job crafting—ensuring both cultural relevance and practical applicability. Notably, the programme was implemented in a 2-day classroom format within the same South African organization and showed significant improvements in mental wellbeing, as measured by the WEMWBS. These findings indicate that the ENGAGE model is not only theoretically robust but also practically effective. As organizations seek scalable and locally adapted solutions to address workplace stress and disengagement, the ENGAGE framework offers a compelling, evidence-informed approach. This research contributes valuable insights for HR practitioners and lays the groundwork for further workplace wellbeing research across diverse contexts.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Industrial Psychology and People Management Research Ethics Committee. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

AS: Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Resources, Data curation, Validation, Investigation, Software, Conceptualization. MS: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Supervision, Methodology, Visualization, Data curation, Conceptualization. RJ: Supervision, Data curation, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Visualization.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/forgp.2025.1624518/full#supplementary-material

References

Addley, K., Boyd, S., Kerr, R., McQuillan, P., Houdmont, J., and McCrory, M. (2014). The impact of two workplace-based health risk appraisal interventions on employee lifestyle parameters, mental health and work ability: results of a randomized controlled trial. Health Educ. Res. 29, 247–258. doi: 10.1093/her/cyt113

Aikens, K. A., Astin, J., Pelletier, K. R., Levanovich, K., Baase, C. M., Park, Y. Y., et al. (2014). Mindfulness goes to work: impact of an online workplace intervention. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 56, 721–731. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000000209

Andersen, L. M. B., Rasmussen, A. N., Reavley, N. J., Bøggild, H., and Overgaard, C. (2021). The social route to mental health: a systematic review and synthesis of theories linking social relationships to mental health to inform interventions. SSM Mental Health 1:100042. doi: 10.1016/j.ssmmh.2021.100042

Anderson, A. R., and Fowers, B. J. (2020). An exploratory study of friendship characteristics and their relations with hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. J. Soc. Pers. Relat. 37, 260–280. doi: 10.1177/0265407519861152

Ang, W. H. D., Chew, H. S. J., Dong, J., Yi, H., Mahendren, R., and Lau, Y. (2022). Digital training for building resilience: systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. Stress Health 38, 848–869. doi: 10.1002/smi.3154

Appiah, R., Wissing, M. P., Fadiji, A. W., and Schutte, L. (2021). The inspired life program: development of a multicomponent positive psychology intervention for rural adults in Ghana. J. Community Psychol. 50, 1–27. doi: 10.1002/jcop.22566

Bai, Y., Ocampo, J., Jin, G., Chen, S., Benet-Martinez, V., Monroy, M., et al. (2021). Awe, daily stress, and elevated life satisfaction. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 120, 837–860. doi: 10.1037/pspa0000267

Baicker, K., Cutler, D., and Song, Z. (2010). Workplace wellness programs can generate savings. Health Aff. 29, 304–311. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0626

Bakker, A. B., and Demerouti, E. (2007). The job demands-resources model: state of the art. J. Manag. Psychol. 22, 309–328. doi: 10.1108/02683940710733115

Barragan-Jason, G., Loreau, M., De Mazancourt, C., Singer, M. C., and Parmesan, C. (2023). Psychological and physical connections with nature improve both human well-being and nature conservation: a systematic review of meta-analyses. Biol. Conserv. 277:109842. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2022.109842

Barros, M. B. D. A., Lima, M. G., Ceolim, M. F., Zancanella, E., and Cardoso, T. A. M. D. O. (2019). Quality of sleep, health and well-being in a population-based study. Rev. Saúde Pública 53:82. doi: 10.11606/s1518-8787.2019053001067

Barry, M. M., Clarke, A. M., Petersen, I., and Jenkins, R. (Eds.). (2019). Implementing Mental Health Promotion. Cham: Springer International Publishing. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-23455-3

Bates-Krakoff, J., Parente, A., McGrath, R., Rashid, T., and Niemiec, R. M. (2022). Are character strength-based positive interventions effective for eliciting positive behavioral outcomes? A meta-analytic review. Int. J. Wellbeing 12, 56–80. doi: 10.5502/ijw.v12i3.2111

Bazargan-Hejazi, S., Dehghan, K., Chou, S., Bailey, S., Baron, K., Assari, S., et al. (2023). Hope, optimism, gratitude, and wellbeing among health professional minority college students. J. Am. College Health 71, 1125–1133. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2021.1922415

Boggiss, A. L., Consedine, N. S., Brenton-Peters, J. M., Hofman, P. L., and Serlachius, A. S. (2020). A systematic review of gratitude interventions: effects on physical health and health behaviors. J. Psychosom. Res. 135:110165. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2020.110165

Bohlmeijer, E. T., Kraiss, J. T., Watkins, P., and Schotanus-Dijkstra, M. (2021). Promoting gratitude as a resource for sustainable mental health: results of a 3-armed randomized controlled trial up to 6 months follow-up. J. Happiness Stud. 22, 1011–1032. doi: 10.1007/s10902-020-00261-5

Bolier, L., Haverman, M., Westerhof, G. J., Riper, H., Smit, F., and Bohlmeijer, E. (2013). Positive psychology interventions: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies. BMC Public Health 13, 1–20. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-119

Borkowska, A., and Czerw, A. (2022). The Vitamin model of well-being at work – an application in research in an automotive company. Int. J. Occup. Med. Environ. Health 35, 187–198. doi: 10.13075/ijomeh.1896.01614

Bourassa, K. J., Caspi, A., Harrington, H. L., Houts, R., Poulton, R., Ramrakha, S., et al. (2020). Intimate partner violence and lower relationship quality are associated with faster biological aging. Psychol. Aging 35, 1127–1139. doi: 10.1037/pag0000581

Braghieri, L., Weizsäcker, G., Levy, E., Makarin, A., Cantoni, D., Egorov, G., et al. (2022). Social media and mental health. Am. Econ. Rev. 112, 3660–3693. doi: 10.1257/aer.20211218

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2022). Thematic Analysis: A Practical Guide. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. doi: 10.53841/bpsqmip.2022.1.33.46

Brémault-Phillips, S., Cherwick, T., Smith-MacDonald, L. A., Huh, J., and Vermetten, E. (2022). Forgiveness: a key component of healing from moral injury? Front. Psychiatry 13:906945. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.906945

Bryant, F. B. (2003). Savoring beliefs inventory (SBI): a scale for measuring beliefs about savouring. J. Mental Health 12, 175–196. doi: 10.1080/0963823031000103489

Bryant, F. B., Smart, C. M., and King, S. P. (2005). Using the past to enhance the present: boosting happiness through positive reminiscence. J. Happiness Stud. 6, 227–260. doi: 10.1007/s10902-005-3889-4

Carpenter, T. P., Pennington, M. L., Seebeck, J., Gomez, D. R., Denman, T. C., Kimbrel, N. A., et al. (2020). Dispositional self-forgiveness in firefighters predicts less help-seeking stigma and fewer mental health challenges. Stigma Health 5, 29–37. doi: 10.1037/sah0000172

Carr, A., Cullen, K., Keeney, C., Canning, C., Mooney, O., Chinseallaigh, E., et al. (2020). Effectiveness of positive psychology interventions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Positive Psychol. 16, 749–769 doi: 10.1080/17439760.2020.1818807

Carr, A., Finneran, L., Boyd, C., Shirey, C., Canning, C., Stafford, O., et al. (2024). The evidence-base for positive psychology interventions: a mega-analysis of meta-analyses. J. Posit. Psychol. 19, 191–205. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2023.2168564

Carrillo, A., Rubio-Aparicio, M., Molinari, G., Enrique, Á., Sánchez-Meca, J., and Baños, R. M. (2019). Effects of the best possible self intervention: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 14:e0222386. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0222386

Colombo, D., Pavani, J.-B., Quoidbach, J., Baños, R. M., Folgado-Alufre, M., and Botella, C. (2024). Savouring the present to better recall the past. J. Happiness Stud. 25:20. doi: 10.1007/s10902-024-00721-2

Costa, H., Saavedra, F., and Fernandes, H. M. (2021). Emotional intelligence and well-being: associations and sex-And age-effects during adolescence. Work 69, 275–282. doi: 10.3233/WOR-213476

Crawford, S. A., and Caltabiano, N. J. (2011). Promoting emotional well-being through the use of humour. J. Positive Psychol. 6, 37–41. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2011.577087

Cregg, D. R., and Cheavens, J. S. (2021). Gratitude interventions: effective self-help? A meta-analysis of the impact on symptoms of depression and anxiety. J. Happiness Stud. 22, 413–445. doi: 10.1007/s10902-020-00236-6

Creswell, J. W., and Creswell, J. D. (2022). Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, 6th Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: sSAGE.

Creswell, J. W., and Poth, C. N. (2018). Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches, 4th Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1991). Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience, Vol. 8. HarperCollins Publishers. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1511458?origin=crossref%5Cnhttp://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=enandbtnG=Searchandq=intitle:FLOW+:+The+Psychology+of+Optimal+Experience#0 (Accessed December 17, 2024).

Cullen, K., Murphy, M., Di Blasi, Z., and Bryant, F. B. (2024). The effectiveness of savouring interventions on well-being in adult clinical populations: a protocol for a systematic review. PLoS ONE 19:e0302014. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0302014

Czekierda, K., Banik, A., Park, C. L., and Luszczynska, A. (2017). Meaning in life and physical health: systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Psychol. Rev. 11, 387–418. doi: 10.1080/17437199.2017.1327325

de Devotto, R. P., Freitas, C. P. P., and Wechsler, S. M. (2020). The role of job crafting on the promotion of flow and wellbeing. Rev. Administração Mackenzie 21. doi: 10.1590/1678-6971/eramd200113

Deloitte (2024). 2024 Gen Z and Millennial Survey. Available at: https://www.deloitte.com/global/en/issues/work/content/genz-millennialsurvey.html (Accessed December 17, 2024).

Demerouti, E. (2014). Design your own job through job crafting. Eur. Psychol. 19, 237–247. doi: 10.1027/1016-9040/a000188

Dhanpat, N. (2019). Job Crafting in Higher Education: A Longitudinal Study. Department of Industrial Psychology and People Management.

Diener, E., and Seligman, M. E. P. (2002). Very happy people. Psychol. Sci. 13, 1–5. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.00415

Dogru, Ç. (2022). A meta-analysis of the relationships between emotional intelligence and employee outcomes. Front. Psychol. 13:611348. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.611348

Dolev-Amit, T., Rubin, A., and Zilcha-Mano, S. (2020). Is awareness of strengths intervention sufficient to cultivate wellbeing and other positive outcomes? J. Happiness Stud. 22, 645–666. doi: 10.1007/s10902-020-00245-5

Donaldson, S. I., Lee, J. Y., and Donaldson, S. I. (2019). Evaluating positive psychology interventions at work: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Appl. Positive Psychol. 4, 113–134. doi: 10.1007/s41042-019-00021-8

Dreer, B. (2022). Teacher well-being: investigating the contributions of school climate and job crafting. Cogent Educ. 9, 1–13. doi: 10.1080/2331186X.2022.2044583

Elufioye, O. A., Ndubuisi, N. L., Daraojimba, R. E., Awonuga, K. F., Ayanponle, L. O., and Asuzu, O. F. (2024). Reviewing employee well-being and mental health initiatives in contemporary HR practices. Int. J. Sci. Res. Archive 11, 828–840. doi: 10.30574/ijsra.2024.11.1.0153

Faulk, J. D., and Yoon, J. (2023). Does practising diverse savouring techniques enhance subjective well-being a randomised controlled trial of design-mediated savouring. J. Design Res. 21, 99–127. doi: 10.1504/JDR.2023.139198

Ford, J., Klibert, J. J., Tarantino, N., and Lamis, D. A. (2017). Savouring and self-compassion as protective factors for depression. Stress Health 33, 119–128. doi: 10.1002/smi.2687

Ford, M. T., Cerasoli, C. P., Higgins, J. A., and Decesare, A. L. (2011). Relationships between psychological, physical, and behavioural health and work performance: a review and meta-analysis. Work Stress 25, 185–204. doi: 10.1080/02678373.2011.609035

Gallup (2024). State of the Global Workplace. Gallup. Available at: https://www.gallup.com/workplace/349484/state-of-the-global-workplace.aspx (Accessed December 17, 2024).

Gartlehner, G., Gaynes, B. N., Amick, H. R., Asher, G. N., Morgan, L. C., Coker-Schwimmer, E., et al. (2016). Comparative benefits and harms of antidepressant, psychological, complementary, and exercise treatments for major depression: an evidence report for a clinical practice guideline from the american college of physicians. Ann. Intern. Med. 164, 331–341. doi: 10.7326/M15-1813

Geier, M. T., and Morris, J. (2022). The impact of a gratitude intervention on mental well-being during COVID-19: a quasi-experimental study of university students. Appl. Psychol. Health Well-Being 14, 937–948. doi: 10.1111/aphw.12359

Good, D. J., Lyddy, C. J., Glomb, T. M., Bono, J. E., Brown, K. W., Duffy, M. K., et al. (2016). Contemplating mindfulness at work: an integrative review. J. Manage. 42, 114–142. doi: 10.1177/0149206315617003

Guest, D. (2017). Human resource management and employee well-being: towards a new analytic framework. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 27, 22–38. doi: 10.1111/1748-8583.12139

Guse, T. (2022). “Positive psychological interventions in african contexts: a scoping review,” in Embracing Well-Being in Diverse African Contexts: Research Perspectives, eds. L. Schutte, T. Guse, and M. P. Wissing (Cham: Springer International Publishing), 375–397. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-85924-4_16

Harzer, C., and Ruch, W. (2013). The application of signature character strengths and positive experiences at work. J. Happiness Stud. 965–983. doi: 10.1007/s10902-012-9364-0

Heekerens, J. B., and Eid, M. (2021). Inducing positive affect and positive future expectations using the best-possible-self intervention: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Posit. Psychol. 16, 322–347. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2020.1716052

Helliwell, J., Layard, R., Sachs, J., De Neve, J.-E., Aknin, L., and Wang, S. (2025). World Happiness Report 2025. Oxford: University of Oxford, Wellbeing Research Centre.

Helliwell, J. F., Huang, H., Norton, M., Goff, L., and Wang, S. (2023). World happiness, trust and social connections in times of crisis. World Happiness Report. Available at: https://worldhappiness.report/ed/2023/world-happiness-trust-and-social-connections-in-times-of-crisis/ (Accessed December 17, 2024).

Hendriks, T., Schotanus-Dijkstra, M., Hassankhan, A., de Jong, J., and Bohlmeijer, E. (2020). The efficacy of multi-component positive psychology interventions: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Happiness Stud. 21, 357–390. doi: 10.1007/s10902-019-00082-1

Hendriks, T., Warren, M. A., Schotanus-Dijkstra, M., Hassankhan, A., Graafsma, T., Bohlmeijer, E., et al. (2019). How WEIRD are positive psychology interventions? A bibliometric analysis of randomized controlled trials on the science of well-being. J. Positive Psychol. 14, 489–501. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2018.1484941

Holman, D., Escaffi-Schwarz, M., Vasquez, C. A., Irmer, J. P., and Zapf, D. (2024). Does job crafting affect employee outcomes via job characteristics? A meta-analytic test of a key job crafting mechanism. J. Occup. Org. Psychol. 97, 47–73. doi: 10.1111/joop.12450

Hu, Y., Zhang, R., Zhao, S., and Zhang, J. (2024). How and why marriage is related to subjective well-being? Evidence from Chinese Society. J. Fam. Iss. 1–37. doi: 10.1177/0192513X241263785

Hui, B. P. H., Ng, J. C. K., Berzaghi, E., Cunningham-Amos, L. A., and Kogan, A. (2020). Rewards of kindness? A meta-analysis of the link between prosociality and well-being. Psychol. Bull. 146, 1084–1116. doi: 10.1037/bul0000298

Hülsheger, U. R., Alberts, H. J. E. M., Feinholdt, A., and Lang, J. W. B. (2013). Benefits of mindfulness at work: the role of mindfulness in emotion regulation, emotional exhaustion, and job satisfaction. J. Appl. Psychol. 98, 310–325. doi: 10.1037/a0031313

Ibarra, F., Baez, M., Cernuzzi, L., and Casati, F. (2020). A systematic review on technology-supported interventions to improve old-age social wellbeing: loneliness, social isolation, and connectedness. J. Healthc. Eng. 2020, 1–14. doi: 10.1155/2020/2036842

Jennings, R. E., Lanaj, K., Koopman, J., and McNamara, G. (2022). Reflecting on one's best possible self as a leader: implications for professional employees at work. Pers. Psychol. 75, 69–90. doi: 10.1111/peps.12447

Joyce, S., Modini, M., Christensen, H., Mykletun, A., Bryant, R., Mitchell, P. B., et al. (2016). Workplace interventions for common mental disorders: a systematic meta-review. Psychol. Med. 46, 683–697. doi: 10.1017/S0033291715002408

Kabat-Zinn, J. (1994). Wherever You Go, There You Are: Mindfulness Meditation in Everyday Life. London.

Kersemaekers, W., Rupprecht, S., Wittmann, M., Tamdjidi, C., Falke, P., Donders, R., et al. (2018). A workplace mindfulness intervention may be associated with improved psychological well-being and productivity. A preliminary field study in a company setting. Front. Psychol. 9:195. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00195

Kim, H., Doiron, K., Warren, M. A., and Donaldson, S. I. (2018). The international landscape of positive psychology research: a systematic review. Int. J. Wellbeing 8, 50–70. doi: 10.5502/ijw.v8i1.651

Kim, J., Hulett, J., and Heiney, S. P. (2021). Forgiveness and health outcomes in cancer survivorship. Cancer Nurs. 44, E181–E192. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000809

Kim-Godwin, Y. (2020). Effectiveness of best possible self and gratitude writing intervention on mental health among parents of troubled children. J. Psychosoc. Nurs. Ment. Health Serv. 58, 31–39. doi: 10.3928/02793695-20200624-07

Klibert, J. J., Sturz, B. R., LeLeux-LaBarge, K., Hatton, A., Smalley, K. B., and Warren, J. C. (2022). Savoring interventions increase positive emotions after a social-evaluative hassle. Front. Psychol. 13:791040. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.791040

Koay, S.-H., Ng, A.-T., Tham, S.-K., and Tan, C.-S. (2020). Gratitude intervention on instagram: an experimental study. Psychol. Stud. 65, 168–173. doi: 10.1007/s12646-019-00547-6

Kotera, Y., and Van Gordon, W. (2021). Effects of self-compassion training on work-related well-being: a systematic review. Front. Psychol. 12:630798. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.630798

Krekel, C., De Neve, J. E., Fancourt, D., and Layard, R. (2021). A local community course that raises wellbeing and pro-sociality: evidence from a randomised controlled trial. J. Econ. Behav. Org. 188, 322–336. doi: 10.1016/j.jebo.2021.05.021

Kushlev, K., Heintzelman, S. J., Lutes, L. D., Wirtz, D., Oishi, S., and Diener, E. (2017). ENHANCE: design and rationale of a randomized controlled trial for promoting enduring happiness and well-being. Contemp. Clin. Trials 52, 62–74. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2016.11.003

Li, J.-B., Dou, K., and Liang, Y. (2021). The relationship between presence of meaning, search for meaning, and subjective well-being: a three-level meta-analysis based on the meaning in life questionnaire. J. Happiness Stud. 22, 467–489. doi: 10.1007/s10902-020-00230-y

Lim, W. L., and Tierney, S. (2022). The effectiveness of positive psychology interventions for promoting well-being of adults experiencing depression compared to other active psychological treatments: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Happiness Stud. 24, 249–273. doi: 10.1007/s10902-022-00598-z

Lincoln, Y. S., and Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic Inquiry. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. doi: 10.1016/0147-1767(85)90062-8

Litwiller, B., Snyder, L. A., Taylor, W. D., and Steele, L. M. (2017). The relationship between sleep and work: a meta-analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 102, 682–699. doi: 10.1037/apl0000169

Llamas-Díaz, D., Cabello, R., Megías-Robles, A., and Fernández-Berrocal, P. (2022). Systematic review and meta-analysis: the association between emotional intelligence and subjective well-being in adolescents. J. Adolesc. 94, 925–938. doi: 10.1002/jad.12075

Locklear, L. R., Taylor, S. G., and Ambrose, M. L. (2021). How a gratitude intervention influences workplace mistreatment: a multiple mediation model. J. Appl. Psychol. 106, 1314–1331. doi: 10.1037/apl0000825

Long, K. N. G., Worthington, E. L., VanderWeele, T. J., and Chen, Y. (2020). Forgiveness of others and subsequent health and well-being in mid-life: a longitudinal study on female nurses. BMC Psychol. 8:104. doi: 10.1186/s40359-020-00470-w

Maheswaran, H., Weich, S., Powell, J., and Stewart-Brown, S. (2012). Evaluating the responsiveness of the Warwick Edinburgh mental well-being scale (WEMWBS): group and individual level analysis. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 10, 1–8. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-10-156

Malhi, G. S., Das, P., Bell, E., Mattingly, G. W., and Mannie, Z. (2020). Make news: modelling adversity-predicated resilience. Aust. New Zeal. J. Psychiatry 54, 762–765. doi: 10.1177/0004867420935513

McGrath, J. J., Al-Hamzawi, A., Alonso, J., Altwaijri, Y., Andrade, L. H., Bromet, E. J., et al. (2023). Age of onset and cumulative risk of mental disorders: a cross-national analysis of population surveys from 29 countries. Lancet Psychiatry 10, 668–681. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(23)00193-1

Mertika, A., Mitskidou, P., and Stalikas, A. (2020). “Positive relationships” and their impact on wellbeing: a review of current literature. Psychology 25:115. doi: 10.12681/psy_hps.25340

Milligan-Saville, J. S., Tan, L., Gayed, A., Barnes, C., Madan, I., Dobson, M., et al. (2017). Workplace mental health training for managers and its effect on sick leave in employees: a cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet Psychiatry 4, 850–858. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30372-3

Mkhwanazi, D., and Dhanpat, N. (2023). Call centre support staff job crafting and employee engagement: controlling the effects of sociodemographic characteristics. J. Psychol. Afr. 33, 229–234. doi: 10.1080/14330237.2023.2207403

Moitra, M., Owens, S., Hailemariam, M., Wilson, K. S., Mensa-Kwao, A., Gonese, G., et al. (2023). Global mental health: where we are and where we are going. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 25, 301–311. doi: 10.1007/s11920-023-01426-8

Muscaritoli, M. (2021). The impact of nutrients on mental health and well-being: insights from the literature. Front. Nutr. 8:656290. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2021.656290

Myers, D. G. (2001). The American Paradox: Spiritual Hunger in an Age of Plenty. Yale University Press.

Page, K. M., and Vella-Brodrick, D. A. (2013). The working for wellness program: RCT of an employee well-being intervention. J. Happiness Stud. 14, 1007–1031. doi: 10.1007/s10902-012-9366-y

Parks, A. C., Williams, A. L., Tugade, M. M., Hokes, K. E., and Zilca, H. R. D. (2018). Testing a scalable web and smartphone based intervention to improve depression, anxiety, and resilience: a randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Wellbeing 8, 22–67. doi: 10.5502/ijw.v8i2.745

Peterson, C., and Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Character Strengths and Virtues: A Handbook and Classification, Vol. 162. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Quick, J., and Henderson, D. (2016). Occupational stress: preventing suffering, enhancing wellbeing. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 13:459. doi: 10.3390/ijerph13050459

Rivkin, W., Diestel, S., and Schmidt, K.-H. (2018). Which daily experiences can foster well-being at work? A diary study on the interplay between flow experiences, affective commitment, and self-control demands. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 23, 99–111. doi: 10.1037/ocp0000039

Safari, S., and Akbari, B. (2018). The effectiveness of positive thinking training on psychological well-being and quality of life in the elderly. Avicenna J. Neuro Psycho Physiol. 5, 113–122. doi: 10.32598/ajnpp.5.3.113

Saridakis, G., Lai, Y., and Cooper, C. L. (2017). Exploring the relationship between HRM and firm performance: a meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 27, 87–96. doi: 10.1016/j.hrmr.2016.09.005

Saurombe, M. D, Rayners, S. S., Mokgobu, K. A., and Manka, K. (2022). Investigating the perceived influence of remote working on specific Human Resource outcomes during the Covid-19 pandemic. South African Journal of Human Resource Management. 20, 1–12. Available online at: https://sajhrm.co.za/index.php/sajhrm/article/view/2033/3097

Saurombe, M. D., and Barkhuizen, E.N. (2022). Talent Management Practices and Work-related Outcomes for South African Academic Staff. J of Psycho in Africa, 32, 1–6. doi: 10.1080/14330237.2021.2002033

Seligman, M. E. P. (2002). Authentic Happiness: Using the New Positive Psychology to Realize Your Potential for Lasting Fulfillment. Washington, DC: The Free Press.

Seligman, M. E. P. (2011). Flourish: A Visionary New Understanding of Happiness and Well-Being, 1. Free Press hardcover ed. Washington, DC: Free Press.

Seligman, M. E. P., Steen, T. A., Park, N., and Peterson, C. (2005). Positive psychology progress: empirical validation of interventions. Am. Psychol. 60, 410–421. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.60.5.410

Shanahan, M. L., Fischer, I. C., Hirsh, A. T., Stewart, J. C., and Rand, K. L. (2021). Hope, optimism, and clinical pain: a meta-analysis. Ann. Behav. Med. 55, 815–832. doi: 10.1093/abm/kaab001

Shekhar, A., Saurombe, M. D., and Joseph, R. M. (2025). Enhancing employee well-being through a culturally adapted training program: a mixed-methods study in South Africa. Front. Public Health 13:1627464. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2025.1627464

Sin, N. L., and Lyubomirsky, S. (2009). Enhancing well-being and alleviating depressive symptoms with positive psychology interventions. J. Clin. Psychol. 65, 467–487. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20593

Suárez Álvarez, A., and Vicente, M. R. (2024). Is too much time on the internet making us less satisfied with life? Appl. Res. Qual. Life. 19, 2245–2265. doi: 10.1007/s11482-024-10326-9

Sun, J., Dehghan, M., Soltanmoradi, Y., Altwalbeh, D., Ghaedi-Heidari, F., et al. (2024). Quality of life, anxiety and mindfulness during the prevalence of COVID-19: a comparison between medical and non-medical students. BMC Public Health. 24, 1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12889-024-20477-x

Sutton, A. (2020). Living the good life: a meta-analysis of authenticity, well-being and engagement. Pers. Individ. Dif. 153:109645. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2019.109645

Symeonidou, D., Moraitou, D., Pezirkianidis, C., and Stalikas, A. (2019). Promoting subjective wellbeing through a kindness intervention. Hellenic J. Psychol. 16, 1–21. doi: 10.26262/hjp.v16i1.7888

The Luv U Project. (2017). The Luv u Project—Our Mission. Available online at: https://theluvuproject.org/about/our-mission/ (Accessed December 7, 2024).

Tolcher, K., Cauble, M., and Downs, A. (2024). Evaluating the effects of gratitude interventions on college student well-being. J. Am. College Health 72, 1321–1325. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2022.2076096

Toussaint, L., Cheadle, A., Dezutter, J., and Williams, D. R. (2021). Late adulthood, COVID-19-related stress perceptions, meaning in life, and forgiveness as predictors of mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Psychol. 12:731017. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.731017

Tuck, N.-J., Farrow, C. V., and Thomas, J. M. (2023). Frequency of fruit consumption and savoury snacking predict psychological health; selective mediation via cognitive failures. Br. J. Nutr. 129, 660–669. doi: 10.1017/S0007114522001660

Van Zyl, L. E., Efendic, E., Rothmann, S., and Shankland, R. (2019). “Best-practice guidelines for positive psychological intervention research design,” in Positive Psychological Intervention Design and Protocols for Multi-Cultural Contexts. eds, S. Rothmann & L. E. Van Zyl (Cham: Springer International Publishing). 1–33. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-20020-6

Verma, R., Sekar, S., and Mukhopadhyay, S. (2025). Unlocking flourishing at workplace: an integrative review and framework. Appl. Psychol. 74:e12591. doi: 10.1111/apps.12591

Waldinger, R., and Schulz, M. (2023a). The Good Life: And How to Live it: Lessons from the World's Longest Study on Happiness. Britain: Rider.

Waldinger, R., and Schulz, M. (2023b). The Good Life: Lessons from the World's Longest Scientific Study of Happiness. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster.

Weiss, L. A., Westerhof, G. J., and Bohlmeijer, E. T. (2016). Can we increase psychological well-being? The effects of interventions on psychological well-being: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS ONE 11:e0158092. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0158092

WHO (2024). Suicide. World Health Organization. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/suicide (Accessed December 17, 2024).

Wiese, C. W., Kuykendall, L., and Tay, L. (2018). Get active? A meta-analysis of leisure-time physical activity and subjective well-being. J. Positive Psychol. 13, 57–66. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2017.1374436

Wrzesniewski, A., and Dutton, J. E. (2001). Crafting a job: revisioning employees as active crafters of their work. Acad. Manage. Rev. 26, 179–201. doi: 10.2307/259118

Wu, A., Roemer, E. C., Kent, K. B., Ballard, D. W., and Goetzel, R. Z. (2021). Organizational best practices supporting mental health in the workplace. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 63, e925–e931. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000002407

Yaden, D. B., Batz-Barbarich, C. L., Ng, V., Vaziri, H., Gladstone, J. N., Pawelski, J. O., et al. (2022). A meta-analysis of religion/spirituality and life satisfaction. J. Happiness Stud. 23, 4147–4163. doi: 10.1007/s10902-022-00558-7

Keywords: employee wellbeing, HR-led intervention, workplace mental health, training programme, South Africa

Citation: Shekhar A, Saurombe MD and Joseph RM (2025) From theory to practice: a participatory HR-led training programme for employee wellbeing. Front. Organ. Psychol. 3:1624518. doi: 10.3389/forgp.2025.1624518

Received: 08 May 2025; Accepted: 18 July 2025;

Published: 18 August 2025.

Edited by:

Santiago Gascon, University of Zaragoza, SpainReviewed by: