Abstract

In order to form an impression of the traits, views, and competencies of election candidates, voters often draw on existing stereotypes about their identities and characteristics, such as their gender or ethnicity. Meanwhile, although there is a strong stigma associated with disability in our societies, we know very little about how voters perceive candidates with disabilities. This study uses a survey experiment with a conjoint design conducted in Britain to examine the effects of candidate disability on voter perceptions of their personality traits, beliefs, and issue competencies. Contrary to common stereotypes, physically disabled candidates are not seen as incompetent and weak. Instead, they are perceived as more compassionate, honest, and hard-working than nondisabled candidates, although the effects are modest in size. They are also assumed to be further to the left ideologically and more concerned about and competent in dealing with policy on healthcare, minority rights, and social welfare. The study enriches our understanding of the role of disability in electoral behavior and political representation while also providing valuable—and overall encouraging—insights for disabled (aspiring) politicians and political parties.

Introduction

Over a billion people—around 15% of the world’s population—live with a disability (WHO, 2018). As defined in Article 1 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), this includes people who “have long-term physical, mental, intellectual or sensory impairments which in interaction with various barriers may hinder their full and effective participation in society on an equal basis with others.” Disabled people1 have historically experienced discrimination, stigma, and exclusion from various spheres of society and continue to do so today (Ryan, 2019; Nario-Redmond, 2020). As a key step to improving their rights and living conditions, the disability community has consistently called for greater inclusion in political decision-making processes—in other words, “Nothing About Us Without Us” (Charlton, 1998). Yet, political representatives who are known to be disabled, either because they have a visible impairment or because they publically identify as such, remain few and far between (House of Commons, 2010). Anonymous candidate survey data from the United Kingdom confirm that disabled people are underrepresented among candidates seeking election to parliament, constituting only around 10% compared to 20% in the general public (Reher, forthcoming 2020b). This underrepresentation might be one reason for the lower levels of political trust and electoral participation of disabled people, which scholars have observed in different countries (e.g., Schur and Adya, 2013; Mattila and Papageorgiou, 2017; Powell and Johnson, 2019; Reher, 2020a).

The numerical underrepresentation of disabled people in politics is likely to be jointly explained by a range of different factors. While studies have pointed out various barriers in the political recruitment process, from inaccessible buildings to higher costs of campaigning and a political culture that is often not inclusive (Evans and Reher, 2020; Waltz and Schippers, 2020), our understanding of how voters view disabled candidates remains extremely limited (but see Loewen and Rheault, 2019). Yet, based on what we know about voter attitude formation and decision-making, on the one hand, and the pervasiveness of disability stereotypes, on the other, we have strong reasons to suspect that candidate disability does influence voter perceptions.

As voters rarely have the motivation, capacity, and resources to gather a large amount of information to evaluate candidates in an election, they often rely on cognitive shortcuts (Lau and Redlawsk, 2001). Stereotypes about social groups are a powerful basis of information that we use to form our impression of others (Fiske and Neuberg, 1990), and this also applies to the political context: studies have shown that voters make assumptions about the character traits as well as the policy interests, positions, and competencies of candidates based on their gender (e.g., Sapiro, 1981/1982; Alexander and Andersen, 1993; Huddy and Terkildsen, 1993; Koch, 2002; Sanbonmatsu, 2002; Lawless, 2004; Dolan, 2010; Schneider and Bos, 2014) and their race and ethnicity (Sigelman et al., 1995; Schneider and Bos, 2011; Jones, 2014).

The rarity with which we encounter disabled politicians implies that an impairment is likely to be a characteristic that stands out to voters, and this “contextual novelty” may strengthen the extent to which they use group generalizations to evaluate disabled candidates (Koch, 2002). Cultural stereotypes about disabled people are predominantly negative and often result in avoidant reactions (e.g., Weinberg, 1976; Park et al., 2005; Louvet, 2007; Nario-Redmond, 2010). However, drawing on insights from social psychology and disability studies, I argue that there is another image that might influence voter perceptions, namely, that of an inspirational person who has proven to be capable of overcoming hurdles and persevering in the face of adversity. When it comes to the policy-specific beliefs and competencies of candidates, voters are likely to draw inferences from their assumptions about the experiences and interests of disabled people as well as their trait perceptions.

The expectations are tested via an original survey experiment conducted among a representative sample of the British public (N = 1,500). The conjoint design allows identifying the effects of three common impairment types—a visual, a hearing, and a mobility impairment—among candidates on voter perceptions. The findings suggest that candidate disability influences how voters perceive the traits, beliefs, and competencies of candidates more consistently and strongly than most other characteristics and identities tested, even though the effects are modest in size. Remarkably, the effects are almost exclusively positive, with disabled candidates being perceived as more compassionate, hard-working, and honest than nondisabled candidates. Furthermore, they are seen as more concerned about and competent in handling issues likely assumed to be of particular interest to disabled people: healthcare, minority rights, and social security and welfare. In line with these perceptions, voters also perceive disabled candidates to be situated further to the left on the ideological spectrum.

The study thus yields a number of important insights. First, it firmly places disability on the list of candidate characteristics that we know matter to voters’ attitudes, therefore deserving further research. Second, it suggests that voters perceive disabled candidates as having specific strengths, and using this knowledge strategically might help disabled people gain greater representation in politics. Third, the patterns are not dissimilar to those for gender and ethnicity, encouraging further research into the electoral consequences of the intersections of different identities among candidates.

Theory

Trait Stereotypes

Encountering a disabled person often generates feelings like pity and discomfort in people (Park et al., 2005; Nario-Redmond, 2010). The predominant image is defined by negative characteristics such as incompetence, weakness, vulnerability, low intelligence, and isolation (e.g., Weinberg, 1976; Fichten and Amsel, 1986; Louvet, 2007; Louvet et al., 2009; Nario-Redmond, 2010). Some scholars contend that, in line with stereotypes about low-status groups more generally, these perceptions of low competence go hand in hand with high ratings on compassion (Fiske et al., 2002), although studies of implicit stereotypes show that disabled people are rated lower on warmth (Rohmer and Louvet, 2018). These stereotypes might shape voters’ impressions of disabled candidates in somewhat similar ways to how they tend to perceive women politicians, i.e., as less tough, assertive, and emotionally stable than their male counterparts (e.g., Alexander and Anderson, 1993; Huddy and Terkildsen, 1993; Sanbonmatsu, 2002; Lawless, 2004; Dolan, 2010, Dolan, 2018). Moreover, based on the stereotype content model for low-status groups (Fiske et al., 2002), voters might also see disabled candidates—like female candidates—as more compassionate, honest, and moral.

However, there is also another, contrasting image of disabled people, namely, one that shows them as courageous, inspiring, and heroic (Weinberg, 1976; Nario-Redmond, 2010; Rohmer and Louvet, 2018). Especially in the media and popular culture, disabled individuals are frequently celebrated for “overcoming their impairments” when undertaking everyday tasks perceived as accomplishments (disability scholars have termed this the “regular supercrip” (Kama, 2004; Schalk, 2016)) or achieving extraordinary, superhuman feats (the “glorified supercrip”). As Schalk (2016: 80) explains, the latter “includes activities like climbing Mount Everest, biking across the country, participating in the Paralympics, or becoming a world-renowned musician”—and perhaps also standing for elected office. Indeed, several prominent politicians, particularly in the United States, have framed their disability as proof that they are creative problem solvers and resilient in the face of adversity while also having a unique understanding of the struggles of many people in society (Scotch and Friedman, 2014; Friedman and Scotch, 2017).

If this image of competence, strength, and perseverance linked with compassion is reflected in voters’ perceptions, it would suggest that the stereotypes applied to disabled political elites are distinct from those associated with disabled people more generally. The idea that politicians from a social group are perceived differently from the wider group has already been proposed and examined in the contexts of gender and race. Schneider and Bos (2011) showed that Black politicians are described differently and much more positively than Blacks more generally, with some of the stereotypes shared with Black professionals. Interestingly, having survived adversity and having something to prove are among the key assumed traits of Black politicians (but not politicians in general), which might also apply to disabled politicians. In another study, they found that female politicians are perceived more negatively than women in general, not sharing the “feminine” traits of compassion and physical attractiveness but neither the leadership traits of (male) politicians (Schneider and Bos, 2014). In both cases, the politicians are proposed to constitute a subtype of the larger group, as they are stereotyped in a way that contradicts the image of the wider group (cf. Richards and Hewstone, 2001).

In a similar vein, it is possible that disabled politicians constitute a subtype of disabled people. Alternatively, and perhaps more plausibly given that most citizens will have encountered very few disabled candidates and elected politicians, they might be perceived as members of a wider group of “inspiring” disabled people who have “overcome their impairments.” In both cases, we would expect that disabled politicians are not perceived as less but rather as more competent, stronger, and working harder than nondisabled politicians. In addition, we would expect voters to see disabled politicians as more honest and compassionate due to their assumed experience of adversity in the forms of personal tragedy, lack of access, and societal stigma.

Belief and Issue Competence Stereotypes

In addition to personality traits, voters also form assumptions about the political beliefs and competencies of candidates based on their characteristics and identities. For instance, female politicians tend to be seen as more liberal and supportive of gender equality than male politicians (Huddy and Terkildsen, 1993; Koch, 2002; Dolan, 2018). Voters also perceive them as more competent in dealing with “compassion” issues, such as social security, education, and healthcare, as well as “women’s issues” such as abortion, and less competent in handling “masculine” issues including military, defense, foreign affairs, and agriculture (e.g., Huddy and Terkildsen, 1993; Lawless, 2004; Sanbonmatsu, 2002; Sapiro, 1981/1982). Similarly, non-white candidates are perceived as more left-wing (Jones, 2014; Sigelman et al., 1995; Schneider and Bos, 2011; Besco, 2020) and better at handling policy on issues including civil rights and affirmative action, race relations, welfare, and equal opportunity (Schneider and Bos, 2011). Scholars contend that voters derive belief assumptions from their knowledge of group-based patterns of opinion and voting behavior among citizens as well as their assumptions about candidates’ personal experience with particular issues (McDermott, 1998; Schneider and Bos, 2011). Competence perceptions have been found to be partly rooted in trait and, to a lesser degree, belief stereotypes (Huddy and Terkildsen, 1993) and also appear to be linked to assumed personal experience.

These mechanisms would suggest that voters hold belief and competence stereotypes about disabled candidates, too. First, there are policy domains that directly concern the interests of many disabled people and impact their daily lives. Many, although certainly not all, impairments require medical attention and services, and research has shown that both disabled citizens and candidates tend to give higher priority and support to healthcare spending (Gastil, 2000; Schur and Adya, 2013; Reher, 2020b). Moreover, given the historical and present-day experiences of discrimination, disability rights and minority rights more generally are in their interest as well (Gastil, 2000; Schur and Adya, 2013).

Then, there are issues that are relevant to broad sections of the population but tend to affect disabled people disproportionally, including social security and welfare policy. Since disabled people often face difficulties in accessing education and the labor market, they have higher rates of unemployment and poverty (Ryan, 2019; Nario-Redmond, 2020). Furthermore, many receive targeted social security benefits, such as Personal Independence Payment in Britain or payments to employ carers or personal assistants. To the extent that voters assume that disabled candidates either have personal experience with social security or seek to represent the interests of the wider disability community, they might expect them to be more concerned about and competent in addressing this policy domain. In addition, perceptions of disabled politicians as more compassionate could also drive assumptions of stronger concern and competence in this domain. In sum, we would expect disabled candidates to be perceived as more concerned about and competent in handling policy in the areas of healthcare, minority rights, and social security and welfare.

Next, there are policy domains for which disability might be seen as less relevant or where there are counteracting assumptions. Policy related to family and children is an example of such an issue. On the one hand, higher compassion ratings of disabled candidates might lead to higher perceived concern and competence in this area. Moreover, voters might have support for disabled children and their families in mind, or policy directed at disabled adults and their children. On the other hand, disabled adults are often stigmatized as unsuitable or unable to have children and have historically been denied their reproductive rights (Kallianes and Rubenfeld, 1997). Research confirms that they tend to be seen as asexual, and, in contrast to women more generally, disabled women are not seen as nurturing (Nario-Redmond, 2010). Therefore, it is similarly plausible for voters to perceive disabled candidates as particularly experienced and interested in this policy area, or as less concerned and competent, or to hold ambivalent views due to these counteracting assumptions. In the aggregate, these effects might cancel out. Similarly, the economy is a domain for which disabled people might simultaneously be considered less interested and suited, due to their lower levels of economic activity, or more so, due to their experience of barriers in the labor market. Therefore, we would expect candidate disability not to affect perceived policy concern and competence with regard to family and children and the economy.

Finally, a policy area that might be seen as affecting disabled people and politicians less than nondisabled people is military and defense. In some contexts, such as the United States, disabled politicians have often been veterans who sustained disabling injuries during military service (Friedman and Scotch, 2017). Yet, this is less the case in the United Kingdom and many other countries. Instead, being disabled might be assumed to indicate inexperience and a lack of interest in this issue that is typically perceived as “masculine” and requiring a high level of (physical and mental) fitness. Thus, we would expect that disabled candidates are perceived as less concerned about and competent in handling military and defense policy.

In addition to policy-specific priorities and competence, I analyze voter perceptions of candidates’ broader political beliefs. Like woman (e.g., Koch, 2002), Black and minority ethnic (e.g., Sigelman et al., 1995; Jones, 2014), and gay and transgender candidates (Jones and Brewer, 2019; Magni and Reynolds, 2020), disabled candidates are likely to be perceived as more ideologically left than nondisabled candidates. This should follow from voters’ assumptions about candidates’ experiences of adversity and discrimination, high levels of compassion and desire for equality, and support for public spending on social policy domains. In addition, voters might be aware that disabled citizens tend to have more left-wing views than nondisabled citizens (Gastil, 2000; Schur and Adya, 2013; Bernardi, 2020; Reher, 2020b).

Whether disabled candidates in Britain are in fact more left-wing than their nondisabled peers is unclear. In the 2015 UK Candidates Survey, no Conservative candidate declared a disability, while among the more left-wing parties (Labour Liberal Democrats, Greens, and Scottish National Party), between 9 and 13% of candidates did. Yet, with 18%, the proportion was highest for the right-wing United Kingdom Independence Party (Reher, 2020b) (see Lamprinakou et al., 2019 for similar figures for the 2017 election). Moreover, the 2015 survey data suggest that disabled candidates’ ideological positions do not differ from those of nondisabled candidates, neither across nor within parties (Reher, 2020b). However, it is questionable whether (British) voters are aware of these patterns, given how few high-profile politicians with disabilities there have been and the fact that they have come from different parties, including, for instance, former MPs Anne Begg and David Blunkett (both Labour) and current Conservative MP Robert Halfon. We should also keep in mind that candidates identifying as disabled in the anonymous survey might not do so publicly. It appears more likely, therefore, that voters draw on their trait and belief stereotypes about disabled candidates when judging their ideological stances.

Data and Methods

The hypotheses are tested through an experiment with a conjoint design embedded in an online survey of a representative sample (based on age, gender, and regional quotas) of 1,500 respondents in Britain, conducted through Qualtrics in May and June 2020.2 In the experiment, respondents are presented with descriptions of fictional candidates and asked to evaluate them on a number of dimensions. The United Kingdom is a very suitable case for the study since citizens are used to evaluating and voting for individual political candidates in its general elections, as well as in some subnational elections, under a first-past-the-post system. Moreover, British voters are unlikely to be completely unfamiliar with the idea of disabled candidates considering that the country has had a handful of prominent disabled politicians in the past and currently has a few high-profile representatives with disabilities in the House of Commons (e.g., Robert Halfon MP and Marsha de Cordova MP).

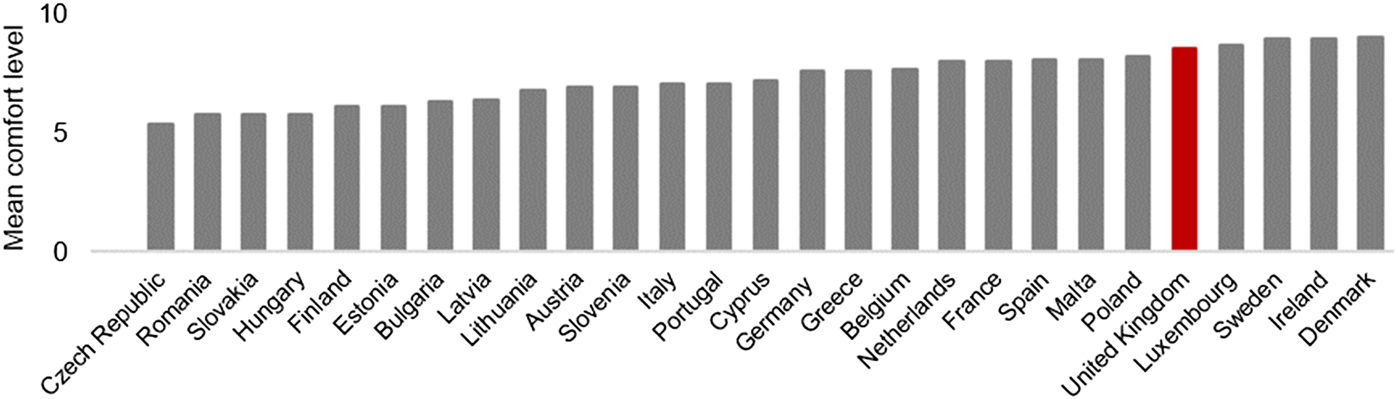

The existence of disability groups within the major political parties, government funding to support disabled candidates’ campaigns3, and the regular inclusion of disability in political debates on representation (House of Commons, 2010) also suggest that British voters are less likely to be surprised by candidate profiles that mention disability than voters in countries where the topic is largely ignored. As a result, there are unlikely to be significant demand effects, where respondents guess the purpose of the experiment and respond in a way that confirms the hypotheses. At the same time, Britain might also be a least-likely case to find negative effects of candidate disability on voter support: cross-national data from a 2012 Eurobarometer survey show that Britons express high levels of comfort with the idea of a disabled political leader as compared to most other European countries (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1

Citizens’ levels of comfort with the idea of a disabled political leader. Data source: Eurobarometer 77.4, 2012, item: “please tell me how you would feel about having someone from each of the following categories in the highest elected political position in (COUNTRY)? ‘1’ means that you would feel “totally uncomfortable” and ‘10’ that you would feel “totally comfortable.” A person with a disability.” Values are country means on a 0–10 scale, with poststratification weights applied.

In the survey experiments, respondents are presented with a pair of short vignettes describing two fictional candidates, A and B, standing for election to the House of Commons in the respondent’s constituency. The descriptions contain information about several attributes of the candidates, which can take on a set of predefined values: gender (either male or female), minority ethnic background (yes/no), age (35–65), profession (doctor/lawyer/teacher/business owner/factory worker) (cf. Carnes and Lupu, 2016), number of children (0–3) (cf. Campbell and Cowley, 2018), years of political activity (4–17), and previous experience of elected office (local Councillor/none). Most importantly, the descriptions either mention no disability or state that the candidate 1) is paralyzed below the waist and uses a wheelchair to get around; 2) is blind and reads using text-to-speech software; or 3) is deaf and communicates mostly in British Sign Language. Details on the attributes and their values are provided in Supplementary Table S1 in the Supplementary Information; Supplementary Figure S1 contains the text of the vignettes.4

The experiment has a conjoint design, meaning that the values of the attributes listed above are, independently from one another, randomly assigned to each respondent. This results in a large number of different combinations of characteristics that a candidate can have. The random assignment allows identifying the effects of each characteristic on the outcomes and comparing their effect sizes. The method enables us to estimate the average marginal component effect (AMCE) of candidate disability over all values of the other attributes, for instance, across male and female candidates and candidates of different ages (Haimueller et al., 2014). This is important, first, because the effects of disability on voter perceptions might vary with other characteristics of the candidates. For instance, if candidate gender and disability interacted, presenting respondents only with male candidates would lead to false conclusions if generalized to female candidates. Second, by manipulating other characteristics of the candidates that voters might associate with disability, we can more accurately identify the effect of disability. For instance, voters might assume that disabled candidates are less educated and less likely to be employed and professionally successful, in line with the lower education, employment, and income levels of disabled people. Alternatively, they might assume that disabled candidates have required more socioeconomic resources in order to stand for election due to the higher barriers. By experimentally manipulating candidates’ profession, I control for such assumptions.

Some attributes have different probabilities of appearing (e.g., ethnic minority background and impairments; Supplementary Table S1) in order for the distribution of candidate profiles to appear more realistic. After being presented with the vignettes, respondents are asked a set of questions about their impressions of the traits, beliefs, and issue competencies of both candidates, listed in Table 1. The response scales of these dependent variables have been normalized to range from 0 to 1 in order to facilitate interpretation of the effect sizes.

TABLE 1

| Concept | Question text | Scale values |

|---|---|---|

| Trait perceptions | “Based on this information, how much do you agree with the following statements with respect to each candidate? Candidate (A/B)…” | 0 = strongly disagree 0.25 = disagree 0.5 = neither agree nor disagree 0.75 = agree 1 = strongly agree |

| Competence | “… has the competence and skills required of a politician.” | |

| Compassion | “… cares about people.” | |

| Strength | “… is strong and authoritative.” | |

| Effort | “… is hard-working.” | |

| Honesty | “… is honest.” | |

| Belief perceptions | ||

| Issue concern | “Below is a list of policy issues. How important do you think the candidates consider each of the different issues?” •Social security/welfare •Military and defense •Healthcare •Minority rights •Economy •Family and children | 0 = not important at all 0.33 = not very important 0.67 = somewhat important 1 = very important |

| Left-right Position | “In politics people often talk of left and right. Where would you place the candidates on the following scale from left to right?” | 0 = left … 1 = right |

| Issue competence | “And how competent do you think the candidates would be in handling these issues if elected?” •Social security/welfare •Military and defense •Healthcare •Minority rights •Economy •Family and children | 0 = not competent at all 0.33 = not very competent 0.67 = somewhat competent 1 = very competent |

Outcome measures.

For the disability treatments, I selected three impairment types with which most people will be at least superficially familiar: a mobility impairment (paraplegic), a visual impairment, and a hearing impairment. Respondents are moreover provided with information about the nature of key barriers—mobility, reading, and communicating, respectively—and the adjustments the candidates use to address them. Thereby, respondents have some additional cues to form an image of what the disability might mean for candidates' election campaign and work as a representative. Deaf persons often communicate in sign languages, such as British Sign Language (BSL), which means that interpreters may be required in face-to-face interactions with other actors involved in the policy-making process, voters or journalists. Since BSL is sometimes their first language, some deaf people also have difficulty reading and writing in English, which could affect, for instance, the speed at which they are able to process policy documents in preparation for parliamentary debates or communication from constituents. In the election campaign, deaf candidates may face barriers communicating with constituents, participating in debates, etc. A range of adjustments can be made to address these barriers, such as providing interpreters and scribes as well as subtitles during speeches and debates. These adjustments require some organizational effort and financial resources, and candidates have reported occasional issues with the provision of these adjustments by political parties (Evans and Reher, 2020).

Individuals with (severe) visual impairments also face barriers related to communication, primarily reading and writing. They often use adjustments such as text-to-speech and speech-to-text software, which can be crucial for officeholders to read policy documents, etc. Additional barriers in this respect include documents in formats that cannot be read by the software and some financial costs of providing hardware and software (Evans and Reher, 2020). Other barriers that voters might be concerned about include difficulties with moving around, for instance, during canvassing but also as elected representatives. By contrast, for persons with mobility impairments who use a wheelchair, communication, reading, and face-to-face interactions are generally not affected as much as accessing the built environment and getting around. These physical barriers can have important implications during election campaigns, depending on the candidate’s financial means, support, and access to transport as well as the accessibility of stages at hustings. Other key concerns that voters might have include the inaccessibility for wheelchair users of parts of the Palace of Westminster and other buildings that MPs need to access, as well as the costs of improving accessibility. Travel, for instance, between London and the representative’s constituency, may also pose a range of barriers.

While the three impairment types and associated barriers are quite different, none of them stands out in terms of the amount or severity of barriers that voters likely anticipate, nor with respect to societal stigma. In Tringo's (1970) hierarchy of disability types, attitudes towards paraplegics are slightly more negative than towards deaf and blind people. At the same time, physical and sensory impairments are generally less stigmatized than intellectual or learning disabilities and mental health conditions (Stone and Colella, 1996; Bell and Klein, 2001). Accordingly, Loewen and Rheault (2019) found that voters have more negative views of, and are less likely to vote for, candidates with mental health conditions as compared to those with physical illnesses. By contrast, we would not expect large differences in voter perceptions for the three impairment types included here. Hence, rather than exploring variation, the aim of this study, and the rationale for including different disabilities, is to establish whether candidate disability has robust effects on voter perceptions.

Analysis

To analyze the effects of candidate disability, I regress the outcome measures on the randomly assigned candidate characteristics using linear regression analysis. All models include fixed effects indicating the position of the candidate in the vignettes (i.e., Candidate A or B in the first or second experiment) and standard errors clustered by survey respondent, as each respondent evaluated two candidates.

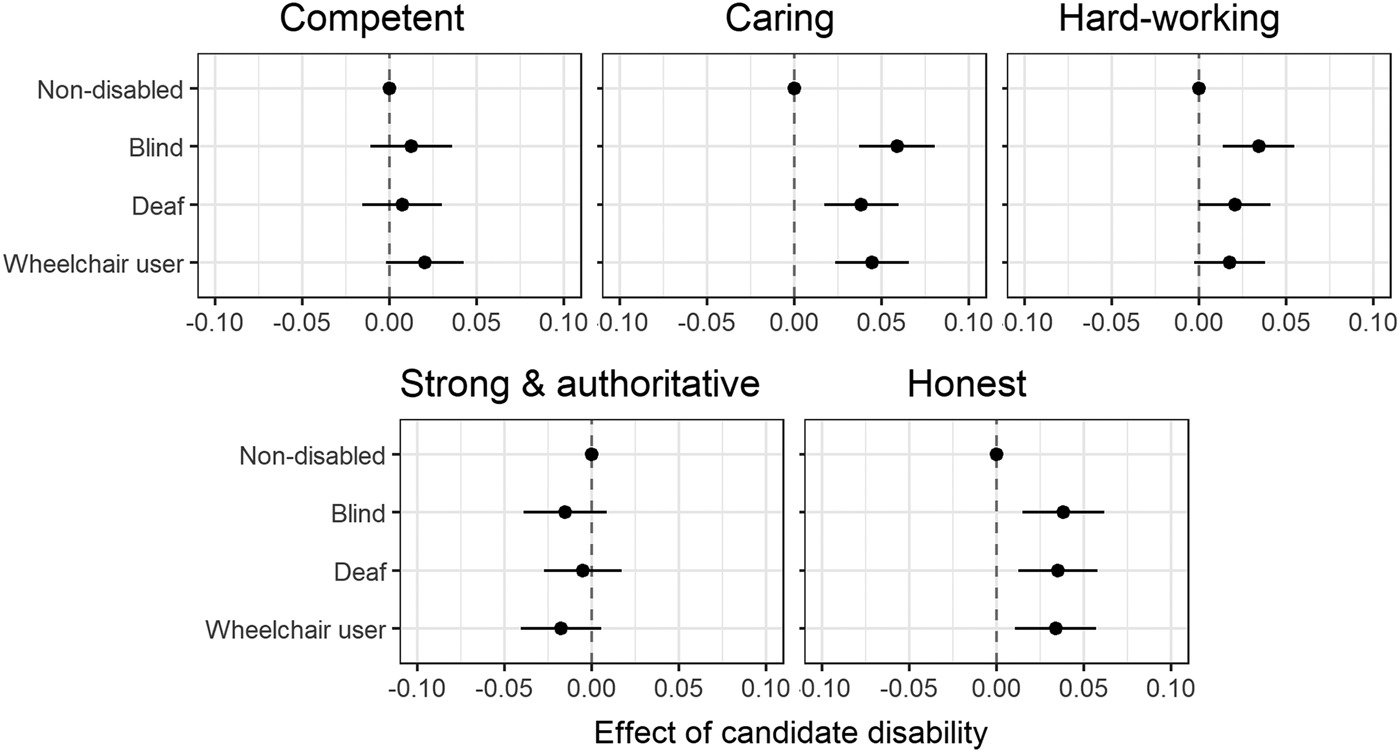

Candidate Traits

I start by analyzing whether voters perceive the personality traits of disabled candidates differently from those of nondisabled candidates. Figure 2 shows the coefficients of the three impairment types with nondisabled as the reference category. In the top left figure, we see that competence ratings do not differ between disabled and nondisabled candidates. The coefficient for the wheelchair-using candidate is positive but not statistically significantly different from zero (alpha = 0.05). This can be seen as reflecting the ambivalence between disabled people being stereotyped as incapable and helpless on the one hand and the image of extraordinary skills and competence, allowing them to overcome obstacles, on the other. In contrast, the disabled candidates are clearly perceived as more caring than the nondisabled candidates, which is interesting considering that previous studies on the perceived warmth of disabled people have yielded contradictory results (Fiske et al., 2002; Rohmer and Louvet, 2018). Voters might assume that they are more empathetic as a result of having experienced hardship. It is worth noting that although these effects are consistent across impairment types, they are modest in size, with differences between the disabled and nondisabled candidates of 0.04–0.06 on the 0-to-1 scale, or 4–6 percentag points.

FIGURE 2

Effects of candidate disability on voter perceptions of candidate traits. Values are average marginal component effects (AMCE) of candidate disability, with nondisabled as the reference category, from linear regression models with controls for other candidate attributes and standard errors clustered by respondents. See Supplementary Table S2 for full estimates.

The absence of a disability effect on perceptions of strength and authority again suggests that the image of a political “supercrip” is not supported or, at least, that such an image is counterbalanced by the stereotypes of weakness and vulnerability. If anything, voters have a tendency to see disabled candidates as weaker than nondisabled candidates, but there are no statistically significant effects. Meanwhile, voters do perceive them as working harder, presumably recognizing that these candidates have had to overcome a range of barriers to become nominated as a candidate. The coefficients are positive for all three impairment types but only statistically significant for the blind and the deaf candidates, whose barriers in the political contest might be seen as more severe. With 0.02–0.034, the effects are smaller than those for compassion perceptions. Finally, in line with previous findings on disability stereotypes and the prediction of the stereotype content model for low-status groups (Fiske et al., 2002), disabled candidates are perceived as more honest than nondisabled candidates, with differences between 3 and 4 percentage points on the scale.

Overall, voters thus hold a more positive image of disabled candidates in comparison to their nondisabled peers and competitors: they see them as more compassionate, hard-working, and honest and simultaneously not more negatively than nondisabled candidates on any of the traits analyzed. While there is variation in the degree to which voters consider different personality traits desirable in politicians, those analyzed all tend to be assets in the electoral competition (Barker et al., 2006; Shephard and Johns, 2008). It is also worth noting that among the attributes included in the vignettes, disability is among those with the most consistent impact on trait evaluations, despite the modest size of the effects. Candidate profession and years of experience also affect perceptions of the majority of traits, whereas candidate gender only influences honesty perceptions, and this effect is half the size of the disability effects.

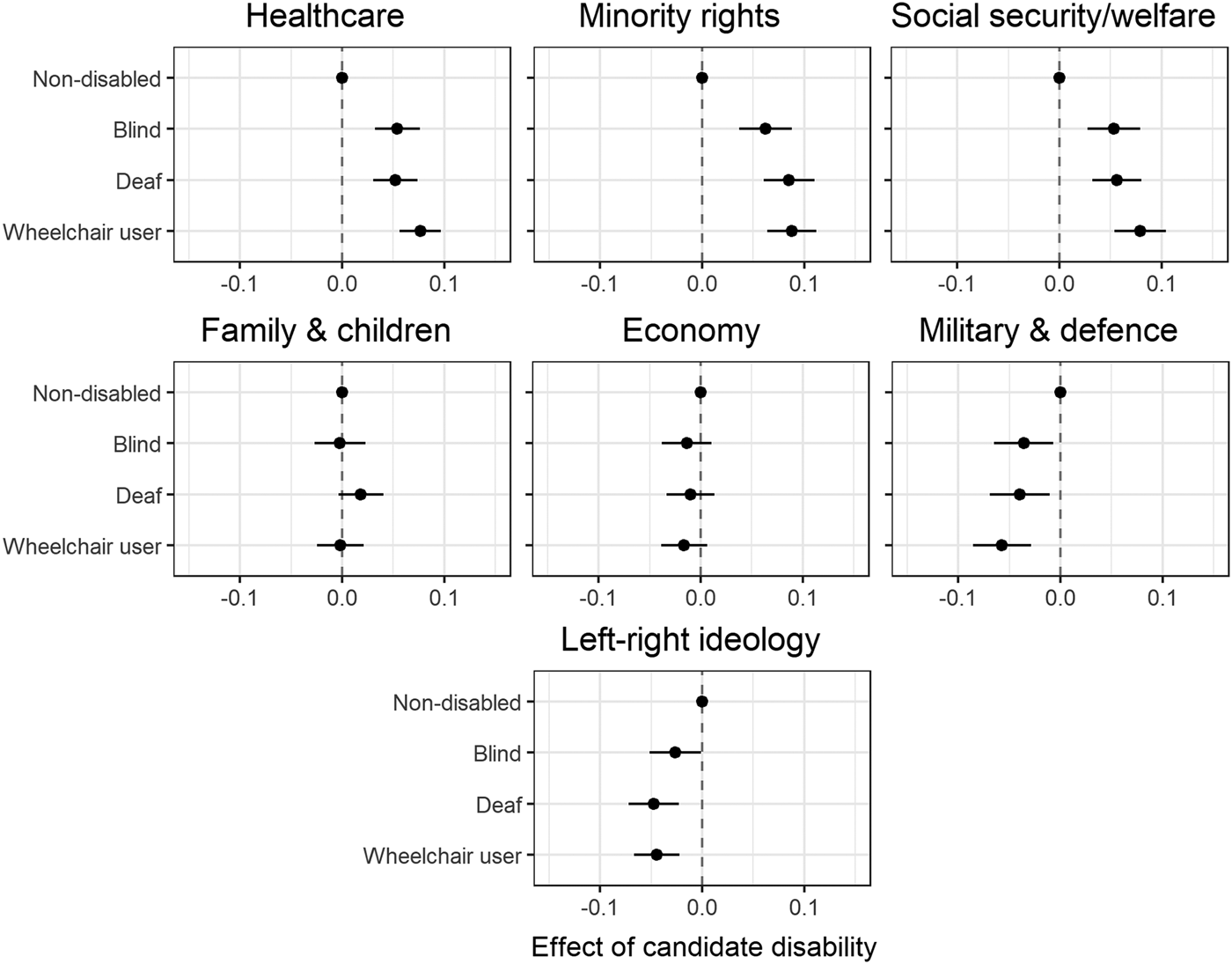

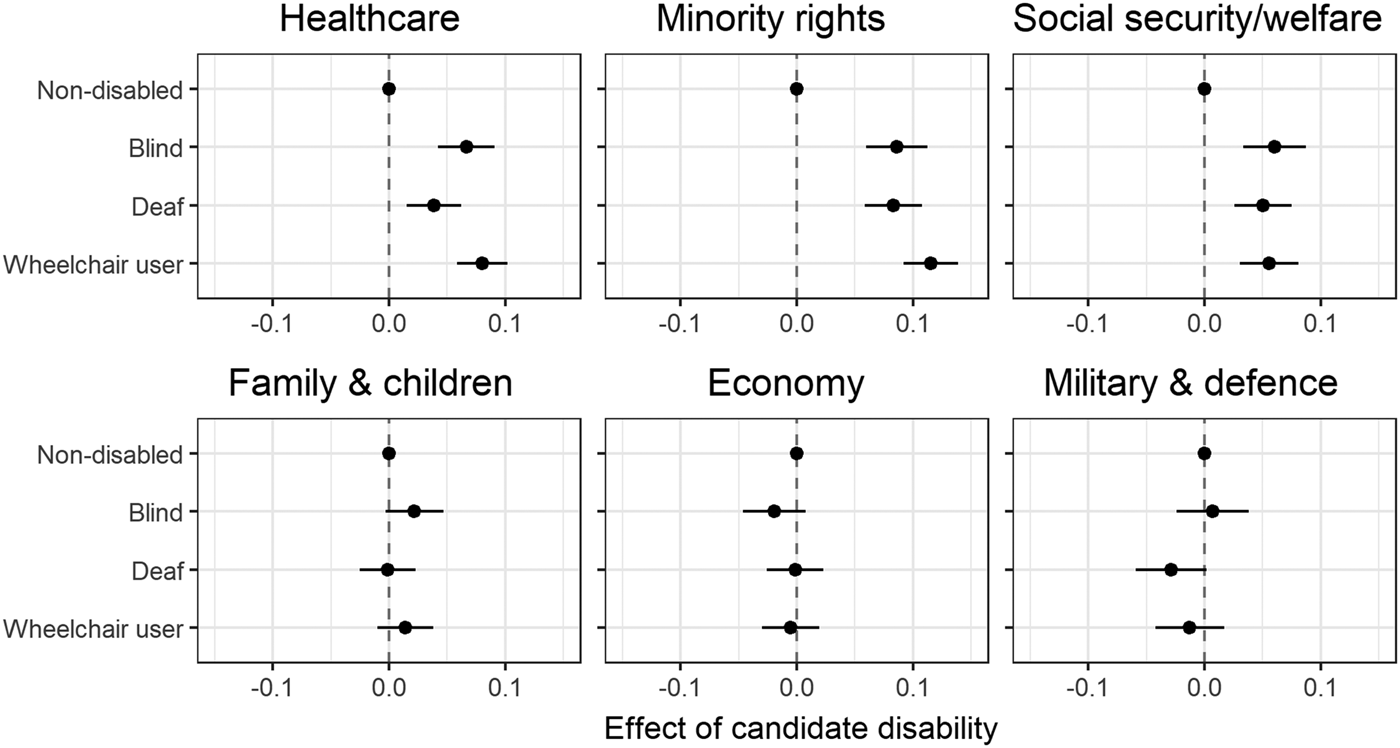

Candidate Beliefs and Competences

Figures 3 and 4 show the results for the effects of candidate disability on voters’ perceptions of their policy beliefs and competencies. As expected, disabled candidates are seen as both more concerned about and more competent in handling healthcare, minority rights, and social security and welfare policy. The effects are between 0.04 and 0.12 points on the 0-to-1 scales and, therefore, generally larger than the effects on trait perceptions. These assumptions are presumably based on the belief that disabled candidates have a personal interest in and first-hand experience with medical services, equality and discrimination issues, and both specific disability-related and more general social security and welfare issues and benefits. To give a basis of comparison for the magnitude of the effects, the differences in perceived concern and competence in minority rights policy between disabled and nondisabled candidates are very similar in size to the differences between minority ethnic and nonminority candidates (Supplementary Table S3). Otherwise, except for candidates’ profession and in one case previous office, none of the other characteristics—age, gender, political experience, or parental status—affect voter perceptions of candidates’ prioritization of healthcare, minority rights, and social security and welfare; for competence perceptions, gender, ethnicity, and previous office only matter sporadically (Supplementary Table S4). This underlines again that candidate disability plays a significant role when voters form impressions of the beliefs and abilities of candidates in elections.

FIGURE 3

Effects of candidate disability on voter perceptions of candidate beliefs. Values are average marginal component effects (AMCE) of candidate disability, with nondisabled as the reference category, from linear regression models with controls for other candidate attributes and standard errors clustered by respondents. See Supplementary Table S3 for full estimates.

FIGURE 4

Effects of candidate disability on voter perceptions of candidate issue competence. Values are average marginal component effects (AMCE) of candidate disability, with nondisabled as the reference category, from linear regression models with controls for other candidate attributes and standard errors clustered by respondents. See Supplementary Table S4 for full estimates.

In the areas of the economy as well as family and children, candidate disability was hypothesized to have no net effect on belief and competence perceptions, as being disabled is likely to generate mixed assumptions of interest and experience in these domains. The findings in Figures 3, 4 confirm these expectations. Although some of the disability coefficients are positive for family and negative for economic policy, none of them is statistically significant. For these policy issues as well as the previous three, the results are remarkably consistent for the three impairment types. For military and defense policy, the findings partly confirm the expectations, as voters assume disabled candidates to place less importance on this policy domain. This is in line with the finding that they are seen as more compassionate, a “feminine” trait, whereas defense is generally regarded as a “masculine” issue. However, disabled candidates are not seen as less capable of handling this policy area.

A pattern that emerges from these findings is that voters tend to perceive disabled candidates as more concerned about issues that are traditionally championed by parties on the left and less about issues associated with—or “owned by” (Petrocik, 1996)—the right. It is, therefore, not surprising that voters also place disabled candidates to the left of nondisabled candidates in ideological terms. These differences are between 0.026 and 0.048 on the 0-to-1 left-right scale—roughly 3–5 percentage points. They are again modest in size but consistent across disability types.

Overall, the findings further support the conclusion above that disabled candidates are evaluated quite positively by voters relative to nondisabled candidates, being seen as more competent on three of the issue areas and as less competent on none. This pattern might of course be somewhat contingent on the policy areas included in the study; however, given that the survey asked about a range of diverse and important policy domains, the pattern is strongly indicative of positive attitudes towards disabled candidates among the British public.5

Conclusion

Despite significant progress in the rights of disabled people over the past few decades, including in the United States with the American Disability Act from 1990, in Britain with the Equality Act 2010, and with the United Nations Convention on the Rights of People with Disabilities from 2006, disabled politicians remain a rare sight. Following the 2019 general election in Britain, there were as few as five MPs in the British House of Commons who identify as disabled6, and the numbers are not higher elsewhere either (Waltz and Schippers, 2020). It is certainly possible that there are also politicians with hidden disabilities who have chosen not to disclose them. Yet, this could be another symptom of the same issue that might be partly at the root of the low numbers: fear of negative reactions from voters. Given that disabled people are stigmatized across societies and often described as weak, incapable, dependent, and vulnerable, traits considered highly undesirable for political leaders, downplaying or ignoring an impairment or refraining from nominating disabled people as candidates would appear to be understandable reactions by (aspiring) candidates and party selectorate.

However, the findings of this study suggest that such fears may be largely unfounded, as voters overall do not appear to apply these negative stereotypes when evaluating disabled candidates. They do not see them as less competent and strong, as theories of stereotypes (Fiske et al., 2002) and previous research on perceptions of disabled people suggest (Nario-Redmond 2010), but instead as working harder than nondisabled candidates. These findings do not go as far as to suggest that disabled candidates are seen as political “supercrips,” an image of disabled people being exceptionally strong, capable, heroic, and inspiring. Yet, they indicate that standing for office with a disability is perceived by voters as evidence of being willing to work hard and able to persevere in the face of obstacles and challenges. Furthermore, voters also perceive disabled candidates as more compassionate and honest, in line with the stereotype content model prediction (Fiske et al., 2002). Thus, disabled candidates are able to enjoy the positive implications of being perceived as a group that has experience with low status and, as a result, a heightened sense of empathy, while avoiding the “flipside” of being seen as incompetent. Although all of the disability effects are rather small, they still tend to be more important than the few effects observed for other characteristics such as gender, ethnic minority identity, age, and even political experience. Only candidates’ profession had larger effects than disability in some cases. Whether and how these views positively influence voters’ willingness to vote for disabled candidates remains to be explored in future research.

That voters associate disabled candidates with healthcare, minority rights, and social policy and welfare does not come as a surprise, considering that studies have consistently shown that voters infer competence in and concern about policy issues from their assumptions about the interests and experiences of the social group to which a candidate belongs. Nevertheless, it is worth pointing out these findings because they have important implications. Voters who consider social policy and particularly issues related to health and disability as important may be inclined to vote for a disabled candidate. Contexts where these issues are salient may thus be particularly promising for disabled candidates. Accordingly, emphasizing these issues and framing their link to disability experience might be an effective campaign strategy for candidates with disabilities and their parties.

This first exploration into the effects of candidate disability on voter perceptions generated a range of further questions for future research. Some of them concern the role of political parties, which serve as a particularly powerful heuristic in voter decision-making (Rahn, 1993). As with candidate gender and race, party affiliation might mitigate the effects of candidate disability or interact with it (e.g., Koch, 2002; King and Matland, 2003; Hayes, 2011). For instance, in cases where disability stereotypes conflict with party stereotypes—i.e., a disabled candidate standing for a right-wing party—voters might either discount the disability stereotypes, or perceive the candidate as more liberal than his or her nondisabled peers (resulting in higher support from liberal voters), or punish the candidate for violating their expectations (Sigelman et al., 1995).

Voters’ own policy preferences are likely to play a key role, too (King and Matland, 2003), as might their personal experience with disability. Given that the disability gaps in the assumed political views of candidates are similar to those observed among citizens (Gastil, 2000; Schur and Adya, 2013; Reher, 2020b), disabled voters might be inclined to support disabled candidates to improve both their descriptive and substantive representation. However, it is also possible that disabled voters are less likely to perceive disabled candidates as a homogenous group and apply stereotypes when evaluating them, as they are more aware of the variation in experiences that disabled people have (Linville et al., 1996). Moreover, the extent to which a coherent disability identity exists remains contested (Watson, 2002; Jenks, 2019; Deal, 2003). Especially members of the deaf community tend to think of themselves as a cultural and linguistic group and often do not identify as disabled (Dolnick, 1993). Therefore, exploring how not only disabled citizens in general but also people with different impairments perceive disabled candidates is crucial in advancing our understanding of this issue. In this context, we should also expand the variety of disabilities among candidates we investigate, including hidden disabilities and chronic illnesses, learning disabilities and mental health conditions, and congenital and acquired impairments. Like the present study, this endeavor will greatly benefit from integrating knowledge and approaches from political science, social psychology, and disability studies.

Another objective for further research will be to expand this work to other contexts. Voter perceptions of disabled politicians are likely to vary with the prevalence and nature of stigma associated with disability in a society, for which we lack systematic comparative evidence as of yet. Moreover, differences in political systems and institutions will shape our research questions, design, and findings. In systems with multimember districts, representatives have more incentives and freedom to speak for social groups with which they identify rather than the geographical area they represent (Tremblay, 2003). This might imply that candidates’ personal characteristics play a more prominent role in shaping voters’ expectations about candidates’ policy priorities in these settings compared to systems with single-member districts (SMD), like the United Kingdom. However, how such considerations affect the vote choice is also likely to vary between electoral systems.

If voters perceive a candidate to represent the interests of a minority group (to which they do not belong), they might be inclined to support this candidate as part of a group of representatives who together represent a diverse group of citizens (i.e., in multimember districts). Yet, they might be less willing to vote for this candidate as the sole representative of their constituency (i.e., in SMD). Thus, we might find stronger support for disabled candidates in proportional representation (PR) systems with open lists, where voters give preference votes for candidates within a party rather than in SMD systems. In contrast, in PR closed-list elections, voters are not asked to evaluate individual candidates. Therefore, these contexts will require a different experimental design, and it is likely that voter perceptions of candidates—however strongly these perceptions are affected by disability—play a weaker role in their vote choice (cf. Chin and Taylor-Robinson, 2005).

The study also lays a foundation for further research into the causes of the low numbers of disabled politicians in power. If it emerges that voters do not discriminate against disabled candidates at the ballot box, as the findings here would lead us to expect, then other factors must be responsible. As previous research shows, candidates report a number of barriers that they experience in the selection and election processes, including a lack of accessibility and insufficient funding to make processes accessible, fewer networks and mentors, a risk of losing disability benefits, and a political culture that can be exclusive and alienating (Evans and Reher, 2020; Waltz and Schippers, 2020). However, there may be other factors, such as societal stigma, fewer resources, or a lack of role models, which can make it difficult or off-putting for disabled people to become involved in political parties and seek nomination as a candidate in the first place (D’Aubin and Stienstra, 2004; Sackey, 2015; Langford and Levesque, 2017; Levesque, 2016). What is more, parties might be hesitant to recruit and select them for various reasons, including prejudice and fear of a backlash at the ballot box. To determine the relevance of these various factors, scholars will need to trace the role of disability in the entire recruitment process, from initial political participation at the citizen level (Schur and Adya, 2013; Mattila and Papageorgiou, 2017; Reher, forthcoming 2020b) to the decision of running for reelection.

Finally, it would be valuable to examine whether the findings travel to perceptions of disabled people in other professional groups, especially those where having experience with adversity in general and/or disability in particular could be seen as an advantage, like the care sector, humanitarian work, or the legal profession. In this context, a key question is whether individuals need to provide some form of evidence for previous achievement, equivalent to being nominated as a candidate, to counter perceptions of low competence and weakness.

Funding

The research was supported by the Economic and Social Research Council (ES/S015469/1) and the Carnegie Trust for the Universities of Scotland (RIG007430).

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the University Ethics Committee, University of Strathclyde. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2020.634432/full#supplementary-material.

Footnotes

.^The terminology preferred by the disability community differs across national contexts. While in North America and elsewhere, person-first language is preferred, i.e., “person with a disability,” the British disability community tends to prefer “disabled person” to express that it is the barriers that exist in society that disable an individual. As this study was conducted in the United Kingdom, I mostly use the latter.

.^The experiment was preregistered with EGAP on June 21, 2020 (ID 20200621AA).

.^https://inclusionscotland.org/what-we-do/employability-and-civic-participation/access-to-politics/aeofs/; https://www.disabilityrightsuk.org/enablefund

.^Each respondent participates in two experiments, which are identical except that one mentions the political parties of the candidates (Conservative or Labor Party), whereas the other one does not. The order in which the experiments appear is randomized. The analyses here only use the data from the no-party experiment.

.^As a robustness check, I estimated equivalent ordinal logit regressions for the dependent variables with four or five levels. These estimates largely confirm the results of the linear regression analyses with very few exceptions: the positive coefficients comparing the paraplegic to the nondisabled candidate on perceptions of competence and working hard are statistically significant in these models, as are the negative coefficients comparing the deaf to the nondisabled candidates on perceived competence on military and defense issues (see Supplementary Tables S5–S7 in the SI).

.^https://www.disabilitynewsservice.com/election-post-mortem-number-of-disabled-mps-may-have-fallen-to-just-five/

References

1

AlexanderD.AndersenK. (1993). Gender as a factor in the attribution of leadership traits. Polit. Res. Q.46, 527–554. 10.2307/448946

2

BarkerD. C.LawrenceA. B.TavitsM. (2006). Partisanship and the dynamics of “candidate centered politics” in American presidential nominations. Elect. Stud.25, 599–610. 10.1016/j.electstud.2005.09.001

3

BellB. S.KleinK. J. (2001). Effects of disability, gender, and job level on ratings of job applicants. Rehabil. Psychol.46, 229–246. 10.1037/0090-5550.46.3.229

4

BernardiL. (2020). Depression and political predispositions: almost blue?Party Polit.10.1177/1354068820930391

5

BescoR. (2020). Friendly fire: electoral discrimination and ethnic minority candidates. Party Polit.26 (2), 215–226. 10.1177/1354068818761178

6

CampbellR.CowleyP. (2018). The impact of parental status on the visibility and evaluations of politicians. Br. J. Polit. Int. Relat.20 (3), 753–769. 10.1177/1369148118775032

7

CarnesN.LupuN. (2016). Do voters dislike working-class candidates? Voter biases and the descriptive underrepresentation of the working class. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev.110 (4), 832–844. 10.1017/S0003055416000551

8

CharltonJ. I. (1998). Nothing about us without us: disability oppression and empowerment. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

9

ChinM. L.Taylor-RobinsonM. M. (2005). The rules matter: an experimental study of the effects of electoral systems on shifts in voters’ attention. Elect. Stud.24, 465–483. 10.1016/j.electstud.2004.06.001

10

DealM. (2003). Disabled people’s attitudes toward other impairment groups: a hierarchy of impairments. Disabil. Soc.18 (7), 897–910. 10.1080/0968759032000127317

11

DolanK. (2010). The impact of gender stereotyped evaluations on support for women candidates. Polit. Behav.32 (1), 69–88. 10.1007/s11109-009-9090-4

12

DolanK. (2018). Voting for women: how the public evaluates women candidates. New York, NY: Routledge.

13

DolnickE. (1993). Deafness as culture. The Atlantic Monthly, 37–53, September, 1993.

14

D’AubinA.StienstraD. (2004). Access to electoral success challenges and opportunities for candidates with disabilities in Canada. Elect. Insight6 (1), 8–14.

15

EvansE.ReherS. (2020). Disability and political representation: analysing barriers to elected office in the UK. Int. Polit. Sci. Rev.10.1177/0192512120947458

16

FichtenC. S.AmselR. (1986). Trait attributions about college students with a physical disability: circumplex analyses and methodological issues. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol.16 (5), 410–427. 10.1111/j.1559-1816.1986.tb01149.x

17

FiskeS. T.CuddyA. J.GlickP.XuJ. (2002). A model of (often mixed) stereotype content: competence and warmth respectively follow from perceived status and competition. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol.82, 878–902. 10.1037/0022-3514.82.6.878

18

FiskeS. T.NeubergS. L. (1990). “A continuum of impression formation from category-based to individuating processes: influence of information and motivation on attention and interpretation,” in Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. Editor ZannaM. P. (New York, NY: Academic Press), Vol. 23.

19

FriedmanS.ScotchR. K. (2017). Politicians with disabilities: challenges and choices. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of PoliticsAvailable at: https://oxfordre.com/politics/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.001.0001/acrefore-9780190228637-e-207 (Accessed November 24, 2020).

20

GastilJ. (2000). The political beliefs and orientations of people with disabilities. Soc. Sci. Q.81, 588–603.

21

HainmuellerJ.HopkinsD. J.YamamotoT. (2014). Causal inference in conjoint analysis: understanding multidimensional choices via stated preference experiments. Polit. Anal.22 (1), 1–30. 10.2139/ssrn.2231687

22

HayesD. (2011). When gender and party collide: stereotyping in candidate trait attribution. Polit. Gend.7, 133–165. 10.1017/S1743923X11000055

23

House of Commons (2010). Speaker’s conference (on parliamentary representation) final report. London, United Kingdom, House of Commons, 239–241.

24

HuddyL.TerkildsenN. (1993). Gender stereotypes and the perception of male candidates. Am. J. Polit. Sci.37, 119–147. 10.2307/2111526

25

JenksA. (2019). Crip theory and the disabled identity: why disability politics needs impairment. Disabil. Soc.34 (3), 449–469. 10.1080/09687599.2018.1545116

26

JonesP. E.BrewerP. R. (2019). Gender identity as a political cue: voter responses to transgender candidates. J. Polit.81 (2), 697–701. 10.1086/701835

27

JonesP. E. (2014). Revisiting stereotypes of non-white politicians’ ideological and partisan orientations. Am. Polit. Res.42 (2), 283–310. 10.1177/1532673X13498266

28

KallianesV.RubenfeldP. (1997). Disabled women and reproductive rights. Disabil. Soc.12 (2), 203–222. 10.1080/09687599727335

29

KamaA. (2004). Supercrips versus the pitiful handicapped: reception of disabling images by disabled audience members. Communications29 (4), 447–466. 10.1515/comm.2004.29.4.447

30

KingG. C.MatlandR. E. (2003). Sex and the grand old party: an experimental investigation of the effect of candidate sex on support for a republican candidate. Am. Polit. Res.31 (6), 595–612. 10.1177/1532673X03255286

31

KochJ. W. (2002). Gender stereotypes and citizens’ impressions of House candidates’ ideological orientations. Am. J. Polit. Sci.46 (2), 453–462. 10.2307/3088388

32

LamprinakouC.MoralesL.RosV.CampbellR.SobolewskaM.Wilks-HeegS. (2019). Research Report No.: 124. Diversity of candidates and elected officials in great Britain. Equality and Human Rights CommissionAvailable at: https://spire.sciencespo.fr/hdl:/2441/1csq2hhch595cr18d132gdnkh0/resources/morales-2019-research-report-124-political-participation-diversity-candidatesgreat-britain-2.pdf (Accessed March 8, 2019).

33

LangfordB.LevesqueM. (2017). Symbolic and substantive relevance of politicians with disabilities: a British columbia case study. Can. Parliam. Rev.40 (2), 8–17.

34

LauR. R.RedlawskD. P. (2001). Advantages and disadvantages of cognitive heuristics in political decision making. Am. J. Polit. Sci.45 (4), 951–971. 10.2307/2669334

35

LawlessJ. L. (2004). Women, war, and winning elections: gender stereotyping in the post-September 11th era. Polit. Res. Q.57, 479–490. 10.2307/3219857

36

LevesqueM. (2016). Searching for persons with disabilities in Canadian provincial office. Can. J. Disabil. Stud.5 (1), 73–106. 10.15353/cjds.v5i1.250

37

LinvilleP. W.FischerG. W.YoonC. (1996). Perceived covariation among the features of ingroup and outgroup members: the outgroup covariation effect. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol.70 (3), 421–436. 10.1037/0022-3514.70.3.421

38

LoewenP.RheaultL. (2019). Voters punish political leaders with depression. Br. J. Polit. Sci.1–10. 10.1017/S0007123419000127

39

LouvetE.RohmerO.DuboisN. (2009). Social judgment of people with a disability in the workplace. Swiss J. Psychol.68, 153–159. 10.1024/1421-0185.68.3.153

40

LouvetE. (2007). Social judgment toward job applicants with disabilities: perception of personal qualities and competences. Rehabil. Psychol.52, 297–303. 10.1037/0090-5550.52.3.297

41

MagniG.ReynoldsA. (2020). Voter preferences and the political underrepresentation of minority groups: lesbian, gay, and transgender candidates in advanced democracies. J. Politics. 10.1086/712142

42

MattilaM.PapageorgiouA. (2017). Disability, perceived discrimination and political participation. Int. Polit. Sci. Rev.38 (5), 505–519. 10.1177/0192512116655813

43

McDermottM. L. (1998). Race and gender cues in low-information elections. Polit. Res. Q.51 (4), 895–918. 10.2307/449110

44

Nario-RedmondM. R. (2020). Ableism: the causes and consequences of disability prejudice. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

45

Nario-RedmondM. R. (2010). Cultural stereotypes of disabled and non-disabled men and women: consensus for global category representations and diagnostic domains. Br. J. Soc. Psychol.49, 471–488. 10.1348/014466609X468411

46

ParkJ. H.FaulknerJ.SchallerM. (2005). Evolved disease-avoidance processes and contemporary anti-social behavior: prejudicial attitudes and avoidance of people with physical disabilities. J. Nonverbal Behav.27 (2), 65–87. 10.1023/A:1023910408854

47

PetrocikJ. R. (1996). Issue ownership in Presidential Elections, with a 1980 Case Study. Am. J. Political Sci.40 (3), 825–860. 10.2307/2111797

48

PowellS.JohnsonA. (2019). Patterns and mechanisms of political participation among people with disabilities. J. Health Polit. Pol. Law44 (3), 381–422. 10.1215/03616878-7367000

49

RahnW. M. (1993). The role of partisan stereotypes in information processing about political candidates. Am. J. Polit. Sci.37 (2), 472–496. 10.2307/2111381

50

ReherS. (Forthcoming2020b). Do disabled candidates represent disabled citizens?Br. J. Polit. Sci.

51

ReherS. (2020a). Mind this gap, too: political orientations of people with disabilities in europe. Polit. Behav.42, 791–818. 10.1007/s11109-018-09520-x

52

RichardsZ.HewstoneM. (2001). Subtyping and subgrouping: processes for the prevention and promotion of stereotype change. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev.5 (1), 52–73. 10.1207/S15327957PSPR0501_4

53

RohmerO.LouvetE. (2018). Implicit stereotyping against people with disability. Group Process. Intergr. Relat.21 (1), 127–140. 10.1177/1368430216638536

54

RyanF. (2019). Crippled: austerity and the demonization of disabled people. London, United Kingdom: Verso.

55

SackeyE. (2015). Disability and political participation in Ghana: an alternative perspective. Scand. J. Disabil. Res.17 (4), 366–381. 10.1080/15017419.2014.941925

56

SanbonmatsuK. (2002). Gender stereotypes and vote choice. Am. J. Polit. Sci.46, 20–34. 10.2307/3088412

57

SapiroV. (1981/1982). If U.S. Senator Baker were a woman: an experimental study of candidate images. Polit. Psychol.3 (1/2), 63–81. 10.2307/3791285

58

SchalkS. (2016). Reevaluating the supercrip. J. Lit. Cult. Disabil. Stud.10 (1), 71–86. 10.3828/jlcds.2016.5

59

SchneiderM. C.BosA. L. (2011). An exploration of the content of stereotypes of Black politicians. Polit. Psychol.32 (2), 205–233. 10.1111/j.1467-9221.2010.00809.x

60

SchneiderM. C.BosA. L. (2014). Measuring stereotypes of female politicians. Polit. Psychol.35 (2), 245–266. 10.1111/pops.12040

61

SchurL.AdyaM. (2013). Sidelined or mainstreamed? Political participation and attitudes of people with disabilities in the United States. Soc. Sci. Q.94 (3), 811–839. 10.1111/j.1540-6237.2012.00885.x

62

ScotchR. K.FriedmanS. (2014). Changing times: self-disclosure and the representational styles of legislators with physical disabilities. Disabil. Stud. Q.34 (4). 10.18061/DSQ.V34I4.4008

63

ShephardM.JohnsR. (2008). Candidate image and electoral preference in Britain. Br. Polit.3, 324–349. 10.1057/bp.2008.8

64

SigelmanC. K.SigelmanL.WalkoszB. J.NitzM. (1995). Black candidates, white voters: understanding racial bias in political perceptions. Am. J. Polit. Sci.39 (1), 243–265. 10.2307/2111765

65

StoneD. L.ColellaA. (1996). A model of factors affecting the treatment of disabled individuals in organizations. Acad. Manag. Rev.21, 352–401. 10.2307/258666

66

TremblayM. (2003). Women’s representational role in Australia and Canada: the impact of political context. Aust. J. Polit. Sci.38 (2), 215–238. 10.1080/1036114032000092693

67

TringoJ. L. (1970). The hierarchy of preference toward disability groups. J. Spec. Educ.4 (3), 295–306. 10.1177/002246697000400306

68

WaltzM.SchippersA. (2020). Politically disabled: barriers and facilitating factors affecting people with disabilities in political life within the European Union. Disabil. Soc.10.1080/09687599.2020.1751075

69

WatsonN. (2002). Well, I know this is going to sound very strange to you, but I don’t see myself as a disabled person: identity and disability. Disabil. Soc.17 (5), 509–527. 10.1080/09687590220148496

70

WeinbergN. (1976). Social stereotyping of the physically handicapped. Rehabil. Psychol.23 (4), 115–124. 10.1037/h0090911

71

WHO (2018). Disability and health. Available at: www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/disability-and-health (Accessed Nov 24, 2020).

Summary

Keywords

candidate evaluation, disability, trait stereotypes, belief stereotypes, competence stereotype, survey experiment, conjoint analysis

Citation

Reher S (2021) How Do Voters Perceive Disabled Candidates?. Front. Polit. Sci. 2:634432. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2020.634432

Received

27 November 2020

Accepted

29 December 2020

Published

28 January 2021

Volume

2 - 2020

Edited by

Elisabeth Gidengil, McGill University, Canada

Reviewed by

Miroslav Nemčok, University of Oslo, Norway

Achillefs Papageorgiou, University of Helsinki, Finland

Updates

Copyright

© 2021 Reher.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Stefanie Reher, stefanie.reher@strath.ac.uk

This article was submitted to Elections and Representation, a section of the journal Frontiers in Political Science

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.