- Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Department of Political and Social Sciences, Barcelona, Spain

Electoral rules are a crucial institutional factor shaping the entry and success of new parties. However, testing how they affect voting behavior is problematic when using observational data in cross-national studies. As district magnitude is usually correlated with politically salient features affecting the likelihood of voting for new (and small) parties, the latent support of small parties differs across electoral systems. Using a quasi-experimental design in Spain focused on the district viability of a new party, Vox, in two elections held within 196 days, I provide a more robust estimate of the impact of electoral systems on the success of new parties. Strong evidence that the electoral system makes a difference for new parties has been identified: strategic considerations found in the districts where Vox was not successful prevented a significant number of voters from supporting the party.

1 Introduction

When explaining how voters come to support new (and therefore small) political parties, in particular far-right parties, electoral rules are expected to play a crucial role. As Golder (2016, 486) explains, small parties find it difficult to emerge and succeed when the electoral system is nonpermissive; their supporters have incentives to vote strategically for larger parties, while political entrepreneurs whose policy preferences are not represented by existing parties also face incentives to work within existing large parties.

The conventional research design to examine the impact of electoral systems on the success of new parties uses countries as units of analysis and captures permissiveness with the average district magnitude (or the median legislator’s district), the (dis)proportionality scores, or the number of parties (e.g., Golder 2003; Bolleyer 2013; Bustikova 2014; Laroze 2019). The crucial assumption is that, after controlling for the individual and contextual determinants of vote choice, the latent support for new parties is similar across countries and therefore differences in electoral system permissiveness represent counterfactual situations. I argue that inferences about the effect of electoral systems made through this research design may be flawed.

When using a Proportional Representation (PR) system for the election of national legislatures, districts vary in magnitude with few exceptions (Monroe and Rose 2002; Kedar et al., 2020). Roughly speaking, the higher the average or median district magnitude, the greater the variation in magnitude across districts. Magnitude is expected to be correlated with politically salient features affecting the likelihood of voting for new parties (e.g., urbanization or demographics such employment or elderly population) that are not possible to control for when using observational data. This correlation leads to biased and inconsistent estimates of how electoral systems affect the success of new parties because the average or median district magnitude captures additional mechanisms apart from permissiveness.

I have identified the specific role of electoral permissiveness through a quasi-experimental design. In Spain, two national elections separated by only 196 days were held in 2019 (April 28 and November 10). In the April election, the far-right party Vox won seats for the first time (in 18 out of 52 districts). I estimated the effect of electoral permissiveness by comparing the change between the two elections in the votes obtained by Vox in the districts where the party won seats in the April election and in the districts where it did not win seats. If the electoral system makes a difference to the success of new parties, we should observe that Vox obtained more support in the former group of districts than in the latter. This is exactly the pattern that emerged in the empirical analysis. Individual-level evidence from the November post-election survey strongly supports the role of the electoral system.

2 Limitations of Existing Research

The entry and success of new parties in a given election requires that a significant number of voters change their behavior in a coordinated fashion. As a result, and given that new parties are usually small, the cost of seats in terms of votes makes a difference in new party entry. The more permissive the electoral system, the more likely new party entry can occur. Two complementary mechanisms at the elite and voter levels explain why the transaction costs for electoral coordination for a new set of parties increase with electoral disproportionality. From an elite perspective, new parties are more successful where the institutional barriers to entry are low. As explained by Golder (2016, 486), when the electoral system is nonpermissive, “political entrepreneurs whose policy preferences are not represented by existing parties or who are associated with small parties have strong incentives to work within existing large parties.” From the perspective of voters, “supporters of small parties who do not wish to waste their vote have incentives to vote strategically for larger parties” (Golder, 2016, 486).

However, the empirical evidence is not conclusive. While Harmel and Robertson (1985); Tavits (2006); Bolleyer (2013), chapter 4; Laroze (2019); Chiru et al. (2020); Lago and Torcal (2020) found that the permissiveness of the electoral system is a strong enabler of new party entry, others found that the electoral system has no effect (Powell and Tucker 2014; Mainwaring et al., 2017) or that it can even hurt small parties (Bustikova 2014; Van de Wardt et al., 2017).

The inconsistent results of the existing research about how electoral systems affect the entry and success of new parties has to do with the omitted variable bias. The most conventional strategy to test the hypothesis about the impact of electoral systems is to use observational data from many countries with varying electoral permissiveness or from a single country with varying district magnitudes. After including a number of potentially distorting variables, the assumption is that the (unobservable) latent support of new parties is similar across countries (or districts when examining a single country) and therefore differences in electoral permissiveness across countries (or districts) represent perfect counterfactuals. This is a problematic research design that may lead to inconsistent and flawed estimates.

My argument proceeds in two steps. First, electoral permissiveness (independently of being captured with the average district magnitude, the median legislator’s district (dis)proportionality scores, or the number of parties) is positively correlated with the district magnitude variation within countries. In almost all countries using PR systems (i.e., multimember districts), districts vary in magnitude, but it does not occur in countries using plurality or run-off systems (i.e., when using single-member districts; (Monroe and Rose 2002). As a result, the greater the average district magnitude, the more variation in district magnitude within electoral systems.

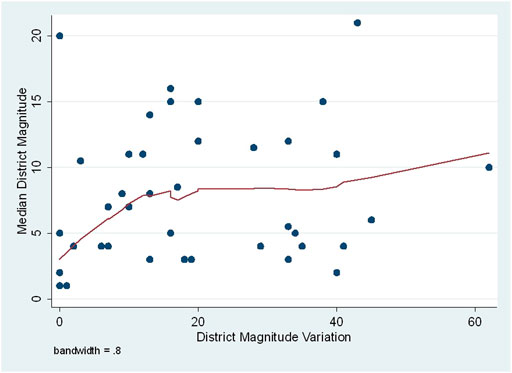

In Figure 1, the relationship between the median district magnitude and district magnitude variation (i.e., the difference between the largest and the smallest districts) in a sample of 47 countries using single-member districts and districted PR systems is displayed. Specifically, a lowest curve is fitted. As can be seen, the correlation is positive (0.34) and statistically significant at the 0.05 percent level.

FIGURE 1. Relationship between electoral permissiveness and district magnitude variation in 47 countries. The source of the data in Kedar et al. (2020).

Second, as Monroe and Rose, (2002, 68) argue, a typical approach when designing a PR system awarding seats in geographically defined districts is using existing administrative divisions as electoral districts and apportioning a varying number of seats (roughly) to population. To the extent that some aspect of mass political opinion affecting the likelihood of voting for new parties, such as urbanization or demographics (e.g., employment or elderly population), is usually correlated with district magnitude, the latent support of new (and small) parties is varying across electoral systems and districts in PR systems. Therefore, when examining the impact of electoral systems on the entry and success of new parties, the average or median district magnitude, proportionality, or the number of parties simultaneously capture two different phenomena: electoral permissiveness and political features correlated with magnitude.

Of course, this correlation does not exist when using districts that do not vary in magnitude, namely in plurality and runoff systems. However, in cross-national comparisons that maximize variation in electoral permissiveness through the comparison of countries using single-member districts and PR systems, this correlation is an issue and there is always speculation that the relationship between electoral systems and the support of new parties may be spurious.

For instance, in a recent analysis, Rama et al. (2021, chapter 4) have examined the socio-demographic determinants that define VOX’s electoral supporters (see also Turnbull-Dugarte et al., 2020). They found that men, university degree-holders, the younger members of Spain’s electorate and above high income individuals are significantly more likely to vote for Vox. More specifically, being a man significantly increases the probability of voting for VOX by 2.6%-points; voters aged 45–54 are 4.2%-points less likely to vote for VOX vis-à-vis those aged 18–24, and this age-induced probability gap increases to 5.3%-points among those over 64 years of age; having a degree is associated with a significantly lower probability of voting for VOX equating to a 7.5%-point degree-holder gap; and comparing those with a monthly income in surplus of €1800 with those who earn less than €900, the former are 7.6%-points more likely to vote for VOX that the latter.

Interestingly, according to the National Statistics Institute of Spain (https://ine.es/en/index.htm), the average education level and per capita income in high population areas (i.e., large districts) is higher and the average age is lower than in low populated areas (i.e., small districts). To the extent that high population areas are represented by high-magnitude districts, Vox’s latent support increases with district magnitude.

As political features correlated with magnitude are very difficult to control in cross-national studies, the latent support of new parties is not similar across countries (or districts when examining a single country) and the possibility that omitted variables are responsible for the reported effect of electoral permissiveness result is still there. The unit homogeneity assumption is violated.

An additional difficultly when trying to include controls and reduce the risk of a spurious relationship when examining the impact of electoral systems is that the individual-level determinants of voting for new parties do not travel well across countries. In their meta-analysis of individual-level research on voting for far-right parties—a common type of new party in recent decades in many European countries—Stockemer et al. (2018) found that there is no core model. In particular, “many predictors of the radical right-wing vote, including education levels or immigration attitudes, do not show any consistent influence in determining an individual’s propensity to vote for the radical right ... the qualitative review reveals that the support base of the radical right is diverse. There are multiple roads toward embracing radical right-wing parties” (Stockemer et al., 2018, 571). If district magnitude is correlated with different political features affecting the likelihood of voting for new parties across countries, this may explain why the evidence on the relationship between electoral systems and support for new parties is mixed.

3 Estimating the Impact of Electoral Systems on the Support of New Parties

To sort out how much strategic considerations (i.e., electoral permissiveness) affect the votes for new parties, I used a quasi-experimental design, which consists of comparing two proximate elections in Spain with the same electorate, under different electoral viability scenarios for the Vox party. This approach provides a better estimate of the consequences of electoral systems for new parties than cross-national research.

The Spanish Parliament elected in the April 10, 2019 election was not able to reach an agreement to choose a Prime Minister. Right-wing parties early on rejected an agreement with the Socialist Party (PSOE) and the failure of the negotiations between the PSOE, and the far-left Podemos led to a new election held 196 days later, on November 10, 2019 (Rodon, 2010). The results of the two elections are displayed in Table 1.

TABLE 1. Results of the April and November 2019 elections in Spain*.

The huge district magnitude variation in Spain and the results of Vox in the April 2019 election provide a unique opportunity for estimating how electoral systems affect the support for new parties in the November 2019 election. First, the Lower House Elections in Spain are held under a PR system with the d’Hondt rule, closed party lists and a 3% threshold at the district level (which only matter in the two largest districts, Madrid and Barcelona). The 350 MPs were elected in 52 districts with magnitudes ranging from 1 (Ceuta and Mellila) to 37 (Madrid). The mean district magnitude was 6.73 and the median 5. Given that the two elections were held 196 days apart, the variables affecting the likelihood of voting for Vox and that are potentially correlated with district magnitude are similar. More specifically, as the sociodemographic and economic composition of districts is similar in the two elections (and the party leaders and candidates did not change), my first assumption is that Vox’s latent support in every district is equal when comparing the April and November elections. In the case of comparing two elections held in a conventional electoral cycle (i.e., an election every four years), the ceteris paribus assumptions would be violated.

However, there is a possible drawback. The November election was held due to the inability of the main parties for form a government. As this reason is endogenous to party competition, it is possible that voters’ behavior in the November election was affected by the frustration over the repetition of the election. This point seems particularly relevant when taking into account that the right-wing Ciudadanos lost 2.5 million votes in the November election. If this frustration is not randomly distributed across districts and therefore it is more influential in some districts than in others, the effect of district magnitude would not be perfectly isolated. My second assumption is that there are no time-varying district-level differences in the variables affecting voting behavior. In the empirical analysis I will show that the difference in the Vox vote share in the November and April elections at the district level is not correlated with (the log of) district magnitude.

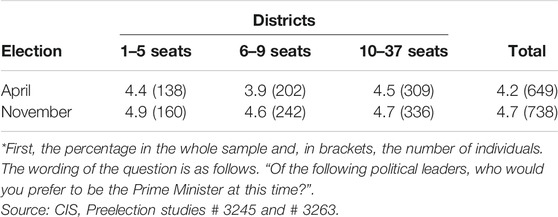

In Tables 2 and 3 I provide some individual-level evidence supporting the assumption. In Table 2 the percentage of individuals for whom Santiago Abascal, the Vox’ leader, was the preferred Prime Minister in the April and November 2019 elections is displayed. The data are disaggregated at the district level (i.e., I separate small −1 to 5 seats-, medium-size −6 to 9 seats- and large districts −10 or more seats). The sources are the face-to- face representative pre-election surveys conducted by the Centro de Investigaciones Sociologicas some weeks before the corresponding election (http://www.cis.es/cis/export/sites/default/-Archivos/Marginales/3240_3259/3242/es3242mar.pdf and http://www.cis.es/cis/export/sites/default/-Archivos/Marginales/3260_3279/3263/Marginales/es3263mar_Muestra_global.pdf). As can be seen, there are small (not statistically significant) differences between the two elections and interestingly in the November election districts are even more similar than in the April election.

TABLE 2. Vox’s leader (Santiago Abascal) as the preferred Prime Minister (%), April and November 2019 elections*.

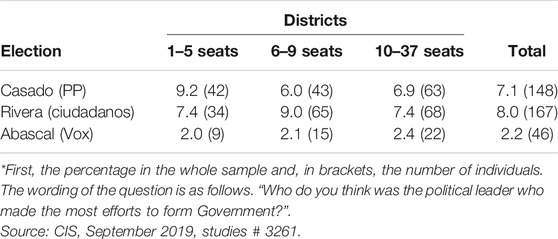

TABLE 3. Political leader who made the most efforts to form Government after the 2019 April election (%).

In Table 3 I examine the relevance of the right-wing party leaders when negotiating the selection of a Prime Minister after the April election. In particular, I show the percentage of individuals who believed that Pablo Casado (Popular Party), Albert Rivera (Ciudadanos) and Santiago Abascal (Vox) were the political leader who made the most efforts to form a Government. The source is a survey conducted by the Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas in September 2019 (http://www.cis.es/cis/export/sites/default/-Archivos/Marginales/3260_3279/3261/es3261mar.pdf). The percentages are small (from the 8.0% in the case of Rivera to the 2.2% in the case of Abascal) and there are no substantial differences across districts.

Second, Vox was created in December 2013. In the pre-election survey conducted by the Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas before the April 2019 election, the average position of Vox (N = 12,467) on the left-right scale ranging from 0 (left) to 10 (right) was 9.3 (the standard deviation was 1.4). In the December 2015 and June 2016 Lower House elections, Vox received 0.23% and 0.20% of the votes, respectively, and 0 seats. In the April 2019 election, however, its results were substantially better: it received 10.3% of the votes and 24 seats in 18 districts (5 seats in the largest district, Madrid). In the November 2019 election, Vox did much better, particularly in terms of seats, and received 15.2% of the votes and 52 seats in 33 districts (7 seats in Madrid).

To estimate whether strategic considerations affect the electoral success for new parties, I focused on the difference in the election results obtained by Vox in the April and November elections across districts. The dependent variable is the difference in the Vox vote share in the November and April 2019 elections at the district level:

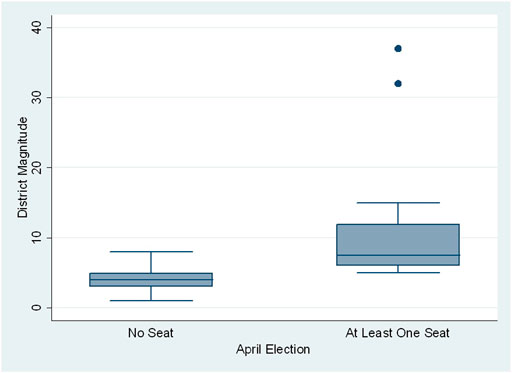

I also controlled for (the logarithm) of district magnitude. Of course, as can be seen in Figure 2, Vox’s viability is strongly correlated with district magnitude. The median district magnitude where Vox won seats in the April 2019 election was 7.5 but 4.0 where it did not. According to the hypothesized mechanisms accounting for the impact of electoral systems on the success of new parties, this impact should be driven by viability instead of district magnitude.

Finally, as the dependent is not the Vox vote share in a given election but the difference between two consecutive elections, the correlation between district magnitude and Vox’s latent support is not an issue. The dependent variable is already capturing this latent support.

4 Results

4.1 Aggregate-Level Analysis

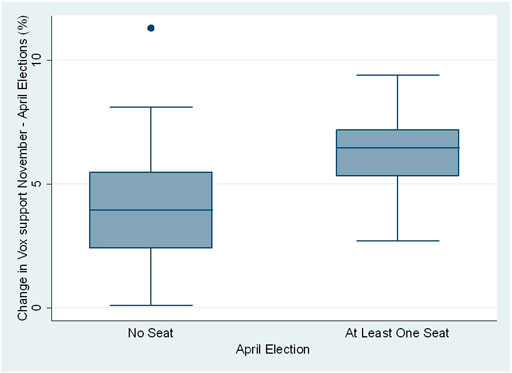

The first piece of evidence supporting that electoral systems are a crucial institutional factor shaping the political opportunity confronting new parties is displayed in Figure 3. In particular, the difference in Vox’s voting share between the November and April elections in the districts where it won at least one seat in April and those where it did not is compared through a box plot. As expected, Vox did much better in November in the former (median of 6.45) than in the latter (median of 3.95).

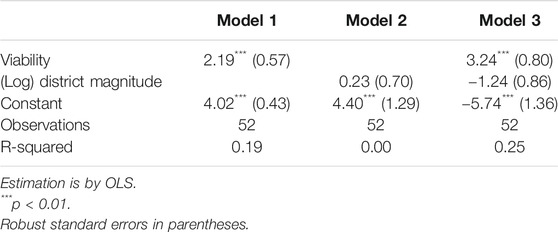

The results of the regression models are presented in Table 4. In the first model, I tested whether Vox’s viability in the April election made a difference in the November election. This expectation is strongly supported. Viability had the expected positive coefficient and is statistically significant at the 0.01 percent level; Vox improved its vote share by 2.19 points more in the districts where it won seats in April than in the districts where it did not. The constant shows that Vox did much better in the November election than in April election. The model explains the 19% variance in the district-level difference in Vox’s vote share between the two elections. In the second model, Viability was replaced with the (log of) district magnitude. Electoral permissiveness captured with the number of seats to be filled in the districts has the expected positive sign but is very far from being statistically significant. The fit of the model is very poor (with an R2 of 0.00). Finally, the third model, which combines the regressors from the first two, clearly shows that the effect of the electoral system is driven by Vox’s viability, not by district magnitude. The coefficient on Viability substantially increases and remains statistically significant at the 0.01 percent level, while the (log of) district magnitude is again not statistically significant. These results strongly support my assumptions that Vox’s latent support in every district was equal when comparing the two elections and therefore that only strategic considerations changed between the elections.

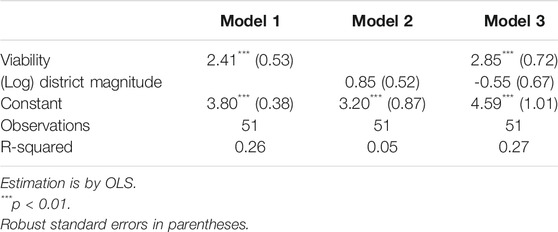

To show that the results are not driven by unusual observations or outliers, in Table 5 I ran the models after deleting those observations whose studentized residuals were greater than three in absolute value. The number of observations dropped from 52 to 51 (the studentized residual for the single-member of Ceuta was 3.33). The results are qualitatively the same. Again, Viability positively affects Vox’s vote share and is statistically significant at the 0.01 percent level in Models 1 and 3. Similarly, the (log of) district magnitude does not make a difference when explaining the change in Vox’s electoral support.

4.2 Individual-Level Analysis

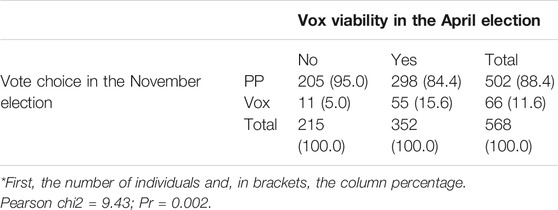

In the individual-level analysis, I examined the vote transfers from the Popular Party to Vox in the 2019 November election, the two most relevant rightist parties in the November election. The PP was the right-wing party with the most votes in the April and November 2019 elections in Spain. Relying again on the pre-election survey conducted by the Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas some weeks before the November 2019 election, the average position of PP (N = 13,575) on the left-right scale ranging from 0 (left) to 10 (right) was 8.1 (the standard deviation was 1.4). In 51 out of 52 districts (Ceuta is the exception) in the April 2019 election, the PP did better than Vox. According to my argument, and taking into account that Vox did much better in the November election than in the April election, the expectation is that more PP voters in April voted for Vox in November in the districts where Vox won seats in April than in those where it did not.

Table 6 strongly supports the expectation according to the evidence provided by the face-to-face representative post-election survey conducted by the Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas some weeks after the November 2019 election. While only 5% of PP voters (11 individuals) in April voted for Vox in November in the districts where Vox was not successful in April, 15.6% of PP voters (55 individuals) in April voted for Vox in November in the districts where Vox was successful in April, This difference is statistically significant at the 0.01 percent level according to the Chi2 statistic.

TABLE 6. Vote choice in the November election of PP voters in the April election*.

5 Conclusion

Electoral rules are a crucial institutional factor shaping the entry and success of new parties. The strategic considerations of voters and elites harm new (and small) parties when the electoral system is nonpermissive. This expectation has been tested using observational evidence from cross-national studies comparing electoral systems with varying district magnitudes (i.e., permissiveness). This research design is problematic. As district magnitude is usually correlated with politically salient features affecting the likelihood of voting for small parties that are not possible to control for when using observational data, the latent support of small parties differs across electoral systems: the unit homogeneity assumption is violated.

Using a quasi-experimental design, I have provided a more robust estimate of the impact of electoral systems on the success of new parties. In a short period of time, 196 days, two national elections were held in Spain. In the first one, in April 2019, Vox, a party created in late 2013, won seats for the first time in 18 out of 52 districts. In November 2019, Vox did much better in these districts than in the remaining 34 districts compared to the April election results. In other words, I found strong evidence that the electoral system, captured with party viability, makes a difference for new parties: strategic considerations in nonpermissive districts, or more specifically in those districts where a party is not successful, prevent a significant number of voters from supporting new parties. As the dependent variable measures the difference in Vox’s results between the November election and the April election in the districts, the varying Vox latent support in the districts is not an issue.

There is only one drawback in my research design. As the reason to hold the November 2019 election was endogenous to electoral competition, it is possible that the frustration over the inability of the main parties to form a government was greater for voters in some districts than in others. The assumption that there are no time-varying district-level differences in the variables affecting voting behavior might be violated. The individual-level evidence about the irrelevance of right-wing parties in the negotiation to form a government does not support this hypothesis. However, this is a potential limitation of my approach.

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: www.cis.es.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Funding

I thank Ferran Martínez i Coma for his helpful comments. I acknowledge support from the Spanish Minister of Science, Innovation and Universities (Grant number AEI/FEDER CSO2017-85024-C2-1-P), and the ICREA under the ICREA Academia program.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Bolleyer, N. (2013). New parties in old party systems: persistence and decline in 17 democracies. Oxford and New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 272.

Bustikova, L. (2014). Revenge of the radical right. Comp. Polit. Stud. 47, 1738–1765. doi:10.1177/0010414013516069

Chiru, M., Popescu, M., and Székely, I. G. (2020). Political opportunity structures and the parliamentary entry of splinter, merger, and genuinely new parties. Politics [Epub ahead of print]. doi:10.1177/0263395720943432

Golder, M. (2003). Explaining variation in the electoral success of extreme right parties in Western Europe. Comp. Polit. Stud. 36, 432–466.

Golder, M. (2016). Far right parties in Europe. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 19, 477–497. doi:10.1146/annurev-polisci-042814-012441

Harmel, R., and Robertson, J. H. (1985). Formation and success of new parties. Int. Polit. Sci. Rev. 6, 501–523. doi:10.1177/019251218500600408

Kedar, O., Harsgor, L., and Tuttnauer, O. (2020). Permissibility of electoral systems: a new look at an old question. J. Polit. 82, 1–43. doi:10.1086/709835

Lago, I., and Torcal, M. (2020). Electoral coordination and party system institutionalization. Party Polit. 26 (5), 570–580. doi:10.1177/1354068818795191

Laroze, D. (2019). Party collapse and new party entry. Party Polit. 25 (4), 559–568. doi:10.1177/1354068817741286

Mainwaring, S., Gervasoni, C., and Espanña-Nájera, A. (2017). Extra- and within-system electoral volatility. Party Polit. 23 (6), 623–635. doi:10.1177/1354068815625229

Monroe, B. L., and Rose, A. G. (2002). Electoral systems and unimagined consequences: partisan effects of districted proportional representation. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 46 (1), 67–89. doi:10.2307/3088415

Powell, E. N., and Tucker, J. A. (2014). Revisiting electoral volatility in post-communist countries: new data, new results and new approaches. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 44, 123–147. doi:10.1017/S0007123412000531

Rama, J., Zanotti, L., Turnbull-Dugarte, S. J., and Santana, A. (2021). Vox. The rise of the Spanish populist radical right. London, United Kingdom: Routledge, 160.

Rodon, T. (2020). The Spanish electoral cycle of 2019: a tale of two countries. West Eur. Polit. 43 (7), 1490–1512. doi:10.1080/01402382.2020.1761689

Stockemer, D., Lentz, T., and Mayer, D. (2018). Individual predictors of the radical right-wing vote in Europe: a meta-analysis of articles in peer-reviewed journals (1995–2016). Gov. Oppos. 53 (3), 569–593. doi:10.1017/gov.2018.2

Tavits, M. (2006). Party system change. Testing a model of new party entry. Party Polit. 12, 99–119. doi:10.1177/1354068806059346

Turnbull-Dugarte, S. J., Rama, J., and Santana, A. (2020). The Baskerville's dog suddenly started barking: voting for VOX in the 2019 Spanish general elections. Polit. Res. Exchange 2 (1), 1–21. doi:10.1080/2474736X.2020.1781543

Keywords: district magnitude, electoral system, quasi–experimental design, new parties, viability

Citation: Lago I (2021) Electoral Rules and New Parties: Evidence from a Quasi‐experimental Design. Front. Polit. Sci. 3:623709. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2021.623709

Received: 30 October 2020; Accepted: 13 January 2021;

Published: 24 February 2021.

Edited by:

Marc van de Wardt, Université libre de Bruxelles, BelgiumReviewed by:

Shane P. Singh, University of Georgia, United StatesAdam Ziegfeld, Temple University, United States

Copyright © 2021 Lago. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ignacio Lago, SWduYWNpby5sYWdvQHVwZi5lZHU=

Ignacio Lago

Ignacio Lago