Abstract

In order to understand the way in which scholars approach the study of activism at a time of crisis, a scoping review was conducted to identify the extant empirical work on activism during the COVID-19 crisis. Our search resulted in 23 published papers across disciplines. Results showed elements of continuity and change in scholars' theoretical and empirical approaches to new and old forms of activism emerging at this time of crisis. In general, we found that COVID-19 led to the employment of novel and adaptive approaches from both the activists and the researchers, who tactically modified their strategies in light of the new demands. We conclude by suggesting that incorporating an analysis of the tools of protest, combined with an analysis of the adaptive strategies adopted by communities at a time of crisis might further our understanding of the ontology—as well as the epistemology—of social movements. Moreover, the study highlighted existing tensions between academia and other social stakeholders, which deserve further exploration.

Introduction

The measures put in place by the authorities to reduce the spread of the SARS-CoV-2 virus have had a significant impact on most humans' way of life (Singh and Singh, 2020). In particular, Singh and Singh (2020) review evidence showing how containment measures have significantly impacted people's ability to interact with others and act as a community. The restrictions put in place to avoid the spread of the virus included—in many countries—the limitation to people's ability to assemble, as well as social distancing, isolation, and lockdowns. Under these circumstances, the traditional way to gather in the streets to protest, accost others to ask for a signature to a petition, or meet up with others to discuss the best course of action were a practical impossibility. At the same time, however, the restrictions meant the reduction of other activities—e.g., travel, socializing, sports—which were filling individuals' spare time, opening up the opportunity to focus one's attention on broader social and political issues1. Moreover, the sudden intervention of Governments to significantly alter citizens' way of life may have made salient the power and influence politics has on everyone's everyday life and the inequalities embedded in the system. Indeed, the COVID-19 pandemic highlighted existing social inequalities, which have been the subject of interest of political activists focusing on social justice. For example, Cox (2020), when describing the impact of the pandemic on older adults, explains how “COVID-19 underscores the many inequalities impacting the lives and wellbeing of older adults. Race, ethnicity, and poverty all intersect to increase the chances of both getting and dying from the virus” (p. 620). In this sense, therefore, the pandemic did not reduce—rather heightened the issues activists have been denouncing for a long time, plus the novel circumstances and the way in which they have been dealt with have given rise to further grievances in part of the population.

Thus, notwithstanding the limitations to individuals' ability to gather, people had more opportunities to think about social issues. In addition, the internet—and social media in particular—offered the opportunity to interact remotely in order to share information, communicate and coordinate action (e.g., Nam, 2012).

Therefore, it may not be that surprising that—both off and online—protests erupted in reaction to a series of events, such as the deaths of minoritized group members George Floyd (USA) and Sara Everard (UK), both at the hands of a white male police officer. This posed a series of questions concerning this form of activism at a time in which restrictions were in place, which were echoed in the media (e.g., Lopez, 2020). Simultaneously, the pandemic has hit hard on people's ability to provide for themselves and their loved ones, and members of local communities came together in support of each other (Jetten et al., 2020). Neighborhood needs provided input to the formation of mutual support networks, and solidarity practices in response to those needs showed the importance of active civic and political engagement, at least at the local level (e.g., Jetten et al., 2020).

In light of these premises, it became important for academics to understand the impact of the pandemic on the modalities of individuals' engagement in political action. With this research, we aim to understand how academics have conceptualized and operationalized activism, and how they have approached so far the study of the impact COVID has had (if any) on people's active engagement as members of their Societies. For the purpose of this study, we are interested in behaviors that the researchers identified as a form of political activism or protest. A first step is therefore to provide an operational definition of political activism which we will adopt in the selection and interpretation of the papers. When discussing the meaning of political activism in the context of the creation of the “Arab-American” identity formation, David (2007) characterizes political activism in the following way:

“Political activism goes beyond ‘simply' voting in regular elections; it involves activities such as organizing, petitioning, protesting, lobbying, and the like on the issues that are perceived to be directly related to the Arab-American community” (p. 835).

In line with David (2007), we took a broad approach to understanding political activism, which we define as any action taken by individuals for the benefit of the community they identify with and belong to, however small or comprehensive the individuals define their community. In this sense, therefore, political activism is any behavior the citizen takes as a member of a community for the benefit of the community, and, crucially, actions that have been identified as such by the authors of the papers included in the review. In order to do so, we chose to specifically search for “activism,” “protest,” or “collective action” as relevant terms. The assumption underpinning this choice is that all these terms capture the collective, political nature of the action considered. While we recognize that some authors might disagree with this definition of activism based on alternative definitions which attempt to distinguish—for example—civic vs. political action (see, e.g., Van der Meer and Van Ingen, 2009), we argue that this review relies on the authors' decision and identification of the behaviors as forms of activism. This review summarizes empirical work concerning the implications of COVID-19 for political activism. It aims to establish what we already know from research in the area while also identifying scholars' predominant theoretical and methodological approaches. With the intensifying of extreme events relating to the insufficient mitigation of humans' impact on the natural environment (see, e.g., Ebi et al., 2021; Seneviratne et al., 2021), and the consequent increased frequency of humanitarian and energetic crises, understanding the way in which crises impact social movements, and how scholars approach this question, becomes of utmost importance. In particular, how can we expect social movements—and those researching it—will react to these crises? Analyzing the responses elicited by the COVID-19 crisis will allow us to understand whether—faced with this emergency—research has demonstrated resilience, and whether this crisis offered opportunities to further develop the theoretical and methodological approaches to understanding this phenomenon.

Methods

Open science practices

The scoping review was conducted and reported according to PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses). We preregistered the methodological steps taken for retrieving and analyzing the relevant literature on the Open Science Framework, using the general-purpose registration form created by van den Akker et al. (2020, v. 0.92). The preregistered form and all the materials related to this research project are available on https://osf.io/agr5k/.

Search strategy and data sources

Firstly, we carried out a bibliographic search on three relevant databases (i.e., Web of Science, Scopus, and PsycINFO) to identify the keywords to be used in the main literature search. Following, we performed the main search on the same databases using the following query string: (“COVID-19” OR “pandemic” OR “coronavirus” OR “2019-ncov” OR “SARS-CoV-2” OR “cov-19”) AND (“protest*” OR “activis*” OR “collective action”).

To validate our search strategy, we checked that the list of papers extracted from the databases contained five relevant papers on the topic that we had singled out in advance (see preregistration). Four out of the five relevant papers had a match in the papers list. An inspection of the paper that was absent from the results revealed that it did not make any reference to COVID-19 and, therefore, was not relevant for the present research.

Study selection

The aggregated list of records retrieved from the three databases was uploaded on Rayyan (Ouzzani et al., 2016), a free web tool for managing literature reviews. Firstly, we removed any duplicate records from the database. Then, we performed the screening phase, which was completed in two stages. Initially, the titles, abstracts, keywords, and metadata (i.e., year of publication and language) of the papers were screened for eligibility according to the preregistered exclusion criteria listed in Table 1, left column. Next, the full texts of studies initially assessed as “relevant” for the review were retrieved and checked against the set of preregistered exclusion criteria listed in Table 1, right column. The three authors divided the number of papers to be evaluated evenly.

Table 1

| Exclusion criteria | |

|---|---|

| Initial screening phase | Full-text screening phase |

| Papers published before 2020 | Data were collected before the COVID-19 pandemic |

| Papers in languages other than English | Does not directly address COVID-19 as a core aspect |

| Materials different from published articles | Does not directly address activism as a core aspect |

| Papers that do not include empirical work | Studies deemed to be of low methodological rigor (i.e., quality evaluation is less than three on a 1 to 5 scale; for further details, see Assessment of Methodological Quality section) |

| No data is being used | |

Exclusion criteria for study selection.

To evaluate the reliability of the study selection, we assessed the interrater reliability by randomly selecting 10% of the papers assigned to each coder, having it evaluated by a second coder, and checking for discrepancies in the selection decisions of the two coders. Any discrepancy was resolved by discussion to reach a unanimous decision. The agreement between coders was satisfactory, as the percentage of agreement was 98%.

Assessment of methodological quality

For selecting the papers, we assessed the quality of the research described in the papers by examining five characteristics: (1) the appropriateness of the research design, (2) whether the theoretical framework (3) the constructs under study, (4) the used methods were clearly defined and (5) the understandability of language. Two studies were excluded based on these criteria.

Data extraction

Information about the following characteristics of the studies was extracted: topic of the protest/activism, theoretical framework, variables of interest, methodology, and main results. All the authors completed the data extraction. The selected papers were divided into three equal parts, each of which was assigned to a coder. Ten percent of papers in each set were also evaluated by a second coder. Coders were in agreement 89% of the time, which is satisfactory. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion to reach a unanimous decision.

Narrative synthesis

The narrative synthesis of the eligible studies focused on the theoretical framework of reference and the methods adopted for understanding and empirically exploring activism and protests in the context of COVID-19.

Results

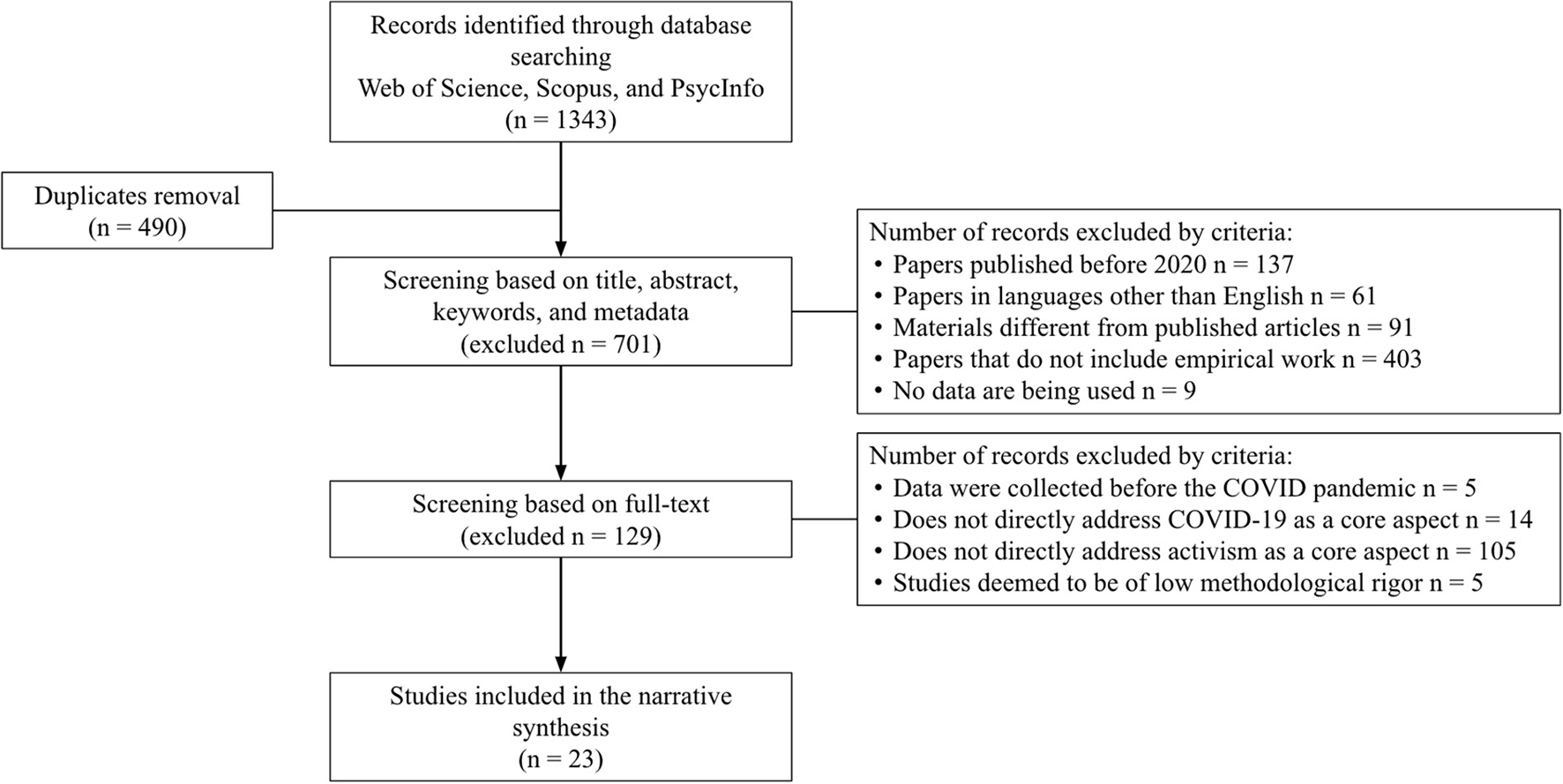

The search resulted in 1,343 items, 490 of which were duplicates. We screened the 853 unique items by applying the exclusion criteria listed in Table 1. In total, we excluded 832 items, 703 after the first screening phase and 129 after the second screening phase. Figure 1 displays this selection process and details how many items were excluded based on each criterion. The next sections discuss the topics, the theoretical approaches, and the methodologies of the 23 selected studies.

Figure 1

Studies selection process and outcomes.

Results on topics

Table 2 summarizes the investigated topics. It shows that eight studies investigated the various forms of civil mobilization in response to the needs that emerged as a consequence of the pandemic, while the others investigated how the pandemic influenced activism, either considered in general (six studies) or the impact of the pandemic on specific forms of activism: social groups' rights (4), political movements and protests (3), environmental activism (2), abortion (1), and ethical consumption (1).

Table 2

| Topic | References | Details |

|---|---|---|

| Response to Pandemic | Andion, 2020 | Collective actions to respond to the needs caused by the pandemic |

| Campedelli and D'Orsogna, 2021 | Disorders expressing unrest related to the COVID-19 pandemic | |

| Graham et al., 2021 | Online campaigns in reaction to COVID-19 pandemic policies | |

| Haupt et al., 2021 | Protest in opposition to public health measures | |

| Igwe et al., 2020 | Formation of solidarity networks | |

| Margolies and Strub, 2021 | Online communities and artistic response to the pandemic | |

| Munandar, 2020 | Protest in response to (lack of) government policies for the pandemic | |

| Prado et al., 2020 | Social solidarity/support | |

| Influence of the Pandemic on Activism | Bloem and Salemi, 2021 | Protests |

| Borbáth et al., 2021 | Political engagement, civic engagement, and participation in public demonstrations | |

| Hellmeier et al., 2021 | Protests | |

| Lalot et al., 2021 | Engagement in collective action | |

| Pressman and Choi-Fitzpatrick, 2020 | Protests | |

| Regus, 2021 | Life strategies of activists | |

| Rights of social groups | Abidin and Zeng, 2020 | Racism (online collective action) |

| Cobbina et al., 2021 | Racism (protests) | |

| Holle et al., 2021 | Artistic identity expression | |

| Zajak et al., 2021 | Pro-migrants mobilizations | |

| Environmental activism | Arya and Henn, 2021 | Challenges and opportunities related to the pandemic for environmental activists |

| Haßler et al., 2021 | Online activism on Twitter (#fridaysforfuture) | |

| Ethical consumption | Carolan, 2021 | |

| Political activism | Unuabonah and Oyebode, 2021 | Protest against the Government |

| Abortion | Hunt, 2022 |

Topics addressed in the researches.

Emerging forms of activism in response to the pandemic (to help the collectivity and to express dissent)

Eight studies investigated a heterogeneous group of activism expressions that emerged in response to specific issues related to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Andion (2020), Igwe et al. (2020), and Prado et al. (2020) focussed on collective actions to respond to the needs caused by the pandemic (e.g., fundraising for the distribution of food or the purchase of protective and hospital equipment, information sharing). Using semi-structured interviews, Igwe et al. (2020) documented the formation of solidarity networks in times of crisis in Nigeria. Andion (2020) performed an analysis of the actors of solidarity in Brazil based on existing datasets and showed that times of crisis have elements of continuity with the past activism scene, but crises also provide an important space for a “reinvention of civil society” and for the emergence of social experimentations and innovations: Indeed, she found that while many of the actors of these campaigns were already protagonists on the activism scene, also new actors emerged, namely the peripheral communities that in certain occasions had a leading role. Prado et al. (2020), who conducted their study in Brazil as well, used a mixed-method approach and found that the initiatives that emerged were very heterogeneous, as they had different targets (e.g., ordinary consumers vs. vulnerable people); also in this case they could show how the pandemic situation brought to innovations in daily tasks (for instance the creation online platforms to buy necessary products or to disseminate information).

Margolies and Strub (2021) examined a peculiar Mexican regional music response to the COVID-19 pandemic in the música huasteca community (música huasteca is a traditional Mexican musical style). As the live meetings were not allowed due to the emergency restrictions, the música huasteca community resorted to livestream performances, in which performers composed original verses addressing the pandemic, and listeners had active participation through their comments. Again, here we see the presence of continuity and transformation, as a pre-existing informal community finds new spaces for participation, with the added value of the transnational connection across the national borders of Mexico and the USA.

Two other studies investigated the dynamics of collective actions of protest. Campedelli and D'Orsogna (2021) analyzed existing data to study pandemic-related disorder events in the three countries with the largest number of incidents, India, Israel, and Mexico, and could show, in all three countries, an interesting “contagion” effect, according to which disorder events showed inter-dependency. Graham et al. (2021) considered online forms of protest and, more specifically, they examined two interrelated hashtag campaigns on Twitter in response to Australian regulations related to the COVID-19 pandemic. Through a mixed-methods approach, they found that a small number of hyper-partisan pro and anti-government campaigners were able to mobilize ad hoc communities on Twitter.

Haupt et al. (2021) also searched into the use of Twitter, this time for protests in favor and in opposition to public health measures. Specifically, they analyzed Twitter posts related to the “Liberate” Protest movement that demanded an end to the lockdown measures using machine learning, content analysis, and social network analysis. They investigated the dynamics of Twitter communication and the structure of Twitter network accounts favoring and opposing the campaign.

Finally, Munandar (2020) explored a different form of protest, showing how protesters used simple banners to express dissent against the local government pandemic prevention policy. With the banners, the protestors took charge of the perceived lack of adequate quarantine measures by imposing their own “local quarantine” using creative methods.

Impact of the pandemic on pre-established activist movements

Five of the studies addressed the question of how the pandemic, and the measures and policies adopted to cope with it, affected activism. These studies looked into different aspects of activism. In particular, Borbáth et al. (2021) used a survey to analyze various forms of political (i.e., signing a petition, contacting a politician, and posting/sharing political content on the internet) and civic engagement (helping in the neighborhood, donating money) and participating in public demonstrations, in seven Western European countries. Three other studies, that had in common their analysis of existing datasets, investigated what the threat of and the policy response to the coronavirus pandemic meant for protests: violent and non-violent intergroup protests worldwide (Bloem and Salemi, 2021), protest events worldwide in general, and pro-democracy protests in particular (Hellmeier et al., 2021), and protests in the United States of America (Pressman and Choi-Fitzpatrick, 2020). Regus (2021) spotlighted activists and, using interviews with a small group of key informants and digital ethnography, investigated how they adapted their lives and strategies in response to the challenges posed by the pandemic.

These five studies show differences in the specific forms of activism that are considered, and the methods used. However, their findings show remarkable persistence in activism. Moreover, their results suggest that the pandemic and its challenges have mobilized new energies in the early phase of the disease spread (Borbáth et al., 2021) and represented a moment of self-reflection and change in strategies (Regus, 2021). Moving on to the more quantitative aspects, these studies show that a drop was recorded in 2020 in protest events, which was smaller than what could have been expected based on the restrictions (Hellmeier et al., 2021). No dramatic change was observed in the protest repertoire in the USA, where street protests and the associated behaviors have continued to be the major form of protest (Pressman and Choi-Fitzpatrick, 2020). In numerical terms, a decline in protest events was registered worldwide, which however has since recovered to pre-pandemic levels (Bloem and Salemi, 2021). Pressman and Choi-Fitzpatrick (2020) registered some changes in the USA protests, in terms of topic, which shifted to public health and economic policies; tactical adjustments to respect the social distancing rules; and of more common use of medical facilities as protest sites.

The remaining nine studies addressed the influence of the pandemic on various specific activism expressions. Four studies investigated activism in favor of the rights of social groups: ethnic minorities (Abidin and Zeng, 2020; Cobbina et al., 2021), immigrants (Zajak et al., 2021), and LGBTQA+ refugees (Holle et al., 2021). Overall, these studies showed how—while the pandemic did not negatively affect the interest and engagement of activists in these social causes, the health concerns and regulatory restrictions associated with traditional, face-to-face forms of protest led to the proliferation of alternative (mainly online) forms of engagement. In studying environmental activism in the UK, Arya and Henn (2021), showed that the pandemic crisis posed problems but was also a source of new possibilities. For instance, the increased use of online spaces on the one side caused worry about surveillance and police infiltration in the activism activities, but on the other side provided more opportunities for participation for those living in rural areas. In a similar vein, Unuabonah and Oyebode (2021) addressed political dissent by investigating the use of political memes related to COVID-19 in Nigeria. They showed how these memes creatively used the COVID-19 discourse to express anger against the socio-political status quo and discontent against the government.

Again we see, therefore, that elements of continuity and change could be identified in single-issue campaigns. In particular, researchers highlighted how the raison d'etre of single-issue campaigns had not necessarily been challenged by the emergence of the crisis. However, the researchers registered responses to the crisis in terms of practices (see, e.g., the case of anti-abortionist movements' activities as a function of the crisis exploitation paradigm in Hunt, 2022) and the nature of the questions asked within those movements (see, e.g., how the pandemic elicited questions about the implications of the crisis for identity-related feelings in Abidin and Zeng, 2020).

All in all, therefore, scholarly work on activism has seen the emergence of studies aimed at exploring the appearance of new forms of activism, both as a response to the crisis, and as a consequence of the limitations the COVID-19 restrictions put on the “normal” forms of activism. Of particular interest here is the fact that the crisis seems to have exacerbated injustices already identified by social movements, but also has led to the engagement in protest and political debate of new actors in the political arena.

Results on theoretical approaches

Table 3 illustrates whether or not the selected studies referred to a theoretical approach and, if so, what it was. We classified the theoretical approaches taken by the researchers into four different categories: “A-theoretical papers,” “Social movement theory,” “Collective action,” and “Overcoming personal barriers.” These are discussed below.

Table 3

| Framework | References | Details |

|---|---|---|

| No theoretical framework | Abidin and Zeng, 2020 | |

| Cobbina et al., 2021 | ||

| Bloem and Salemi, 2021 | ||

| Haupt et al., 2021 | ||

| Hellmeier et al., 2021 | ||

| Lalot et al., 2021 | ||

| Margolies and Strub, 2021 | ||

| Munandar, 2020 | ||

| Unuabonah and Oyebode, 2021 | ||

| Social Movement theory | Andion, 2020 | Resource Mobilization Theory (McCarthy and Zald, 1977); New Social Movements paradigm; theory of Political Mobilization (Tarrow, 2010); democratic experimentalism (Frega, 2019) |

| Graham et al., 2021 | Two-step flow campaign framework | |

| Haßler et al., 2021 | SMO hashtag activism, online/offline activism | |

| Hunt, 2022 | Theory of “crisis exploitation” (Boin, ‘t Hart McConnell) and Social Movement theories (discursive opportunity structures) | |

| Pressman and Choi-Fitzpatrick, 2020 | Social movement theory and crisis literature, Bennett and Segerberg's (2012) connective action | |

| Zajak et al., 2021 | Intersectionality, adaptation through tactical innovations of social movements in times of crisis | |

| Collective action | Carolan, 2021 | Social practice theory: decenters the individual as an analytic unit, with their discrete attitudes and values, and focuses, instead, on the social, symbolic, embodied, and spatial elements that help afford the behaviors (i.e., practices) in questions |

| Igwe et al., 2020 | Conceptual framework of social solidarity and collective action (Douwes et al., 2018) | |

| Political engagement | Arya and Henn, 2021 | As concerns activism: Ekman and Amnå (2012) three categories of political engagement (they are interested in the first category, “alternative actions and spaces, such as protests and activist groups”) |

| Borbáth et al., 2021 | interesting civic vs. political engagement distinction | |

| Overcoming personal barriers | Holle et al., 2021 | Hegemonic discourses (Young, 2001), liminality, and creative agency |

| Regus, 2021 | Life manouvering |

Theoretical frameworks.

A-theoretical papers

Of the 23 papers identified in our search, more than a third (34.62%) had no clear theoretical reference or framework. While this allows access to an accurate snapshot of the characteristics of activism at the time, the lack of theoretical insight does not allow the development of explanatory models that can be applied across contexts and time. For example, Hellmeier et al. (2021) combined data from different well-established cross-national surveys to assess the “state of the world 2020.” They suggested that the world has seen a decrease in activism, while they also pointed out that this may be a temporary phenomenon due to the effects of the restrictions imposed because of the pandemic. The paper is very useful in providing a general description but might leave the reader wanting more in terms of explanation of the phenomenon and prediction of future trends in light of a particular theoretical framework.

Other papers—while starting with little or no reference to theory—do try to use the data to come up with a theoretical contribution or explanation. For example, Cobbina et al. (2021) analyzed interviews with 30 protesters to further our knowledge and understanding of motivational factors underpinning participation in protests. The authors argue that the increased personal risks connected to the pandemic make this case study a compelling example of the importance and power of motivation to protest.

Interestingly, the majority of a-theoretical papers are focusing on artifacts or online materials produced by netizens2. Thus, they attempt to summarize and describe what the landscape looked like at the time. It is possible therefore to conceptualize these papers as “field notes” one could usefully employ in developing a theoretical interpretation of the events. Moreover, applying Cammaerts' (2012) conceptualization of mediation opportunity structure might further our understanding of elements of continuity and change in activists' engagement with media.

Social movement theory

A significant minority of papers referred to what is known as “Social Movement Theory” (SMT), an umbrella term that indicates work exploring the formation and action of social movements, defined as collectives of individuals (more or less loosely organized) who support a particular social goal (see Turner et al., 2020). The focus of these theories is the collective level of analysis; thus, social movements are here seen as a unit. Scholars in this area are concerned, therefore, with the characteristics of such movements and processes involving the decision-making, campaigning, mobilization, and coping mechanisms developed by the collectives in the face of adversities. For example, both Pressman and Choi-Fitzpatrick (2020) and Hunt (2022) relied on literature in the SMT realm which focuses on crises. In particular, Hunt (2022) drew on crisis exploitation theory and discursive opportunity structures to assess whether and to what extent the Twitter accounts belonging to social movement organizations from both sides of the abortion debate in the USA “exploited” the discursive features of talk surrounding COVID-19 to bring forward their respective claims. Somewhat surprisingly, the quantitative analyses showed no evidence of increased activity or campaigning. In contrast, qualitative analyses showed attempts to exploit the crisis by presenting it either as a threat or an opportunity from both sides. In this sense, these papers are mainly concerned with a traditional view of political activism as pertaining to pre-existing social movements advocating for particular groups, and COVID-19 as a challenge to be overcome.

Other papers used more “traditional” (i.e., not crisis-focused) paradigms derived from SMT (Andion, 2020; Graham et al., 2021; Haßler et al., 2021). Andion (2020) showed how traditional mechanisms and structures of activism were mobilized in Brazil to respond to the COVID-19 emergency. Here, we can see the emergence of a new conceptualization, where COVID-19 becomes no longer a “disruption” to the “normal” advocacy work performed by the groups, but the cause of emerging novel political and social issues requiring the mobilization of community resources and collective action. And indeed, the “collective action” angle has been drawn upon by others.

Collective action and political engagement

Rather than focusing on long, sustained campaigns typical of social movement work, other scholars have explored how citizens have acted upon their ideological beliefs among the constraints and limits posed by the “crisis.” Scholars in this area referred to literature on collective action and online/offline political engagement as a background to their work. For example, Carolan (2021) explored how COVID-19 impacted ethical food consumption and its relationship with social activism. Conducting a two-way study via survey and interview data pre and post-COVID-19 crisis, the author showed how the complex constellation of reasons and actions associated with ethical consumption meant that some forms of ethical consumption were negatively impacted by COVID-19. This was especially the case for those who saw self and family-related goals as priorities. On the other hand, the lockdowns provided opportunities for people to act upon other forms of ethical food consumption, such as buying local and cooking more at home. Thus, people adapted their activism to the situation they found themselves in. The important lesson here is, however, that the ideological belief system (i.e., seeing consumerism as a problem or part of the solution) had very different implications overall in the way in which this was conceptualized and acted upon by respondents. In this sense, therefore, COVID-19 was a “crisis” event that might have altered the way in which people acted, but not their ideological approach to the issue.

The tension between de-mobilization and activation forces during COVID-19 was also explored by Borbáth et al. (2021). The authors explored the impact of COVID-19 on political and civic engagement via a survey administered to a representative (stratified) sample of the population in seven European countries. A first interesting result here is that across all sampled countries egotropic feelings of (economic or health) threats have a stronger mobilizing power than sociotropic ones. That is, an individual was more likely to involve themselves with civic and/or political engagement if they felt personally threatened—either for their health or their economic situation. Moreover, the authors showed that while civic engagement was not influenced by an individual's ideological position, political engagement is: at least at the beginning of the pandemic, more right-wing activists engaged in demonstrations, while left-wing activists tended to engage more in alternative forms of activism. All in all, the study demonstrated that—in line with other research—the pandemic uncovered pre-existing tendencies and pushed individuals to find creative solutions to novel challenges.

Overcoming personal barriers

Finally, the fourth category of studies focused on individual-level challenges and how activists overcame them. For example, Regus (2021) explored how women activists in Indonesia coped with the sudden and profound changes in their practices caused by the COVID-19 disruption. To achieve this, the author analyzed interview data with six activists in light of the Life-maneuvering paradigm. Results showed how activists juggled two types of involvement: firstly, they got involved in sustaining themselves, their families, and their communities through the crisis. Second, they continued their advocacy work and re-invented ways in which they could support their cause in the new context. Similarly, Holle et al. (2021) focused on the liminal space occupied by Queer refugees and reported a project in which participants were invited to create artistic works illustrating their experiences during COVID-19 for an online platform. Like in Regus (2021), results showed that activists worked at two different levels: at an individual level, articulating their experiences and positioning in their artwork, and at a social level, by sharing their art within and outside their community.

Overall, these papers highlight an individual level continuity, in that the COVID-19 crisis seems to have posed new challenges (for example, in terms of time and access to resources), but doesn't seem to have induced profound changes in the activists' subjective experiences, at least in the short term. Future research might want to explore whether the subjective experience of activists has had long-term significance.

When considering the entire range of theoretical approaches, our review revealed the notable absence of some important theoretical frameworks, such as the Political Process theory of social movements (Tilly, 1979; one of the most prominent theories in the area of social movements), or Community-based Adaptation Approaches (CBA; e.g., Forsyth, 2013). We find the latter would have been particularly relevant: developed in the context of Climate Change-related challenges and responses, this approach focuses on local drivers in combination with the crisis origin (environmental, in the original case) to identify ways in which local communities responded to the (environmental) threat. This approach could also account for the emergence of new social movements and new forms of activism: indeed, Forsyth quotes a World Bank analyst's observation that:

“Scaling up CBA isn't a question of simply stitching together a “patchwork quilt” of local initiatives… the real contribution of the CBA movement in recent years has been to show that top-down approaches to adaptation will also founder if they fail to connect with the felt priorities of those most vulnerable to climate change” (Mearns, 2011, as cited in Forsyth, 2013, p. 442).

In the context of COVID-19, therefore, the extent to which the population embraced—or reacted to—the Government-led restrictions is only understood by taking into account the extent to which the weakest in a Society have been put in the conditions to abide by them (for a psychologically-informed argument on the importance of catering for the most vulnerable in the COVID-19 context, please see Jetten et al., 2020). Moreover, Cammaerts' (2012) application of the Political Opportunity approach to mediated communication in understanding activism would have been particularly relevant in the context of COVID-19. Haßler et al. (2021) notice how the emergence of COVID posed unprecedented challenges to Social Movement Organizations (SMOs), and suggest that from an academic viewpoint, this entails the development of theories that allow hypothesizing how SMOs will adapt to the use of Social Media accordingly. Indeed, Cammaerts (2021) applied his theoretical framework to explore the role played by Social Media in France's Yellow Vest Movement case. He started by identifying key elements constituting a social movement, which he summarized as PICAR: Program Claims, Identity construction, Connections, Action, and Resolve. He then discussed how Social Media practices and affordances could play a role at each node. Interestingly, Cammaerts's paper proposed that Social Media offer a new-new social movement, characterized by elements of discontinuity and continuity from previous ontologies of social movements. This approach would offer potential integration of on and offline forms of activism in the context of COVID-19, by looking at the opportunity structures afforded by the current media landscape in combination with the situational restraints. We recognize that there may be work already in this area that was not captured by our search. This would occur if the researchers did not adopt the terms “activism,” “protest” or “collective action.” However, this means—in our eyes—that activism per se was not at the fore of the researchers' minds, as they did not use that keyword. This highlights the need to find a common language when addressing social movements and activism.

Results on methods

In the 23 included articles, we can observe a multitude of data types collected (Table 4) and a variety of analytical approaches used to analyze them (Table 5).

Table 4

| Data collection | References | Details |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Data referring to social media activities | McCarthy and Zald (1977) | Facebook group posts and comments |

| Graham et al., 2021 | Tweets related to #IStandWithDan, #DictatorDan and #DanLiedPeopleDied | |

| Haßler et al., 2021 | Tweets related to #fridaysforfuture | |

| Haupt et al., 2021 | Tweets related to #Liberate movement | |

| Hunt, 2022 | Tweets posted by SMOs accounts | |

| Margolies and Strub, 2021 | Videos of son huasteco performances, comments section, and lyrics | |

| Unuabonah and Oyebode, 2021 | Memes circulated on WhatsApp | |

| 2. Survey data | Borbáth et al., 2021 | Cross-sectional study; N = 7,579 respondents from 7 countries;, Most relevant measures: political and civic engagement, economic and health threat perception, ideology |

| Carolan, 2021 | Two-wave study; N = 202; Most relevant items: “I want to play a very active role changing the food system” and “Consumers shape the food system; a point I consider with every purchase” | |

| Lalot et al., 2021 | Two-wave study; N = 298; Most relevant measures: Futures Consciousness; Engagement in collective action | |

| 3. Interview data | Arya and Henn, 2021 | 3 interviews with activists for validation purposes |

| Carolan, 2021 | 57 face-to-face interviews with adults living in Denver | |

| Cobbina et al., 2021 | 30 semi-structured in-depth interviews with protesters in the March on Washington | |

| Holle et al., 2021 | Eight biographical interviews with Queer refugees artists | |

| Igwe et al., 2020 | 39 semi-structured interviews with community leaders, town union leaders, and Church leaders | |

| Regus, 2021 | Six in-depth face-to-face semi-structured interviews with women activists | |

| Zajak et al., 2021 | Six semi-structured interviews with representatives of three of the main migration-related protest mobilizations in Germany | |

| 4. Existing data sets | Bloem and Salemi, 2021 | Armed Conflict Location and Event Data |

| Campedelli and D'Orsogna, 2021 | Armed Conflict Location and Event Data | |

| Hellmeier et al., 2021 | V-Dem data on liberal democracy | |

| Pressman and Choi-Fitzpatrick, 2020 | Crowd Counting Consortium data | |

| 5. Miscellaneous | Andion, 2020 | Reports of civil society organizations activities |

| Munandar, 2020 | 20 banners displayed in rural areas | |

| Prado et al., 2020 | Analysis of 15 social innovation initiatives |

Type of data collection.

SMO, Social Movement Organization.

Table 5

| Approach | References | Details |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Qualitative analysis | McCarthy and Zald, 1977 | Auto-ethnography |

| Andion, 2020 | Documental analysis | |

| Arya and Henn, 2021 | Ethnography: co-production of a matrix of challenges and opportunities | |

| Cobbina et al., 2021 | Inductive analytical techniques | |

| Holle et al., 2021 | Ethnography: feminist approach | |

| Igwe et al., 2020 | Inductive analytical techniques: thematic analysis | |

| Margolies and Strub, 2021 | Digital ethnography | |

| Munandar, 2020 | Sociopragmatic approach | |

| Prado et al., 2020 | Documental analysis | |

| Regus, 2021 | Inductive analytical techniques | |

| Unuabonah and Oyebode, 2021 | Inductive analytical techniques: multimodal discourse analysis | |

| Zajak et al., 2021 | Inductive analytical techniques | |

| 2. Quantitative analysis | Bloem and Salemi, 2021 | Descriptive analysis |

| Borbáth et al., 2021 | Descriptive and regression analysis | |

| Campedelli and D'Orsogna, 2021 | Descriptive analysis, spatial clustering, and temporal Hawkes and Poisson processes | |

| Hellmeier et al., 2021 | Longitudinal analysis | |

| Lalot et al., 2021 | Correlation and regression analysis | |

| Pressman and Choi-Fitzpatrick, 2020 | Descriptive analysis | |

| 3. Both quantitative and qualitative analysis | Carolan, 2021 | Descriptive analysis of survey data and triangulation of survey and qualitative data |

| Graham et al., 2021 | Descriptive analysis, qualitative content analysis, network analysis, sentiment analysis, and bot detection using machine learning | |

| Haßler et al., 2021 | Topic modeling and regression analysis | |

| Haupt et al., 2021 | Topic modeling and social network analysis | |

| Hunt, 2022 | Descriptive analysis and deductive thematic analysis |

Type of analytical approaches.

Data types

Seven studies collected data on social media activities and content from online platforms (e.g., Twitter and Whatsapp). Two studies were conducted through survey and six through interviews. One study used both. Four studies used data from existing databases (e.g., Armed Conflict Location and Event Data and Crowd Counting Consortium). Finally, three studies relied on other types of data (i.e., reports and handwritten banners).

Data from social media activity

The emergence and popularity of social networking sites have permitted researchers from different disciplines to collect data regarding users' behaviors in an unprecedented way. Although the collection and analysis of this type of data is not new in many research contexts—in some more than in others—it proved particularly useful for studying people's political behaviors and attitudes during the pandemic. Indeed, the difficulty, if not impossibility, to collect data using more traditional techniques during the pandemic has encouraged researchers to adapt to the situation and use less common, but certainly effective, techniques. The use of data on social media activity enables researchers to tap information on naturalistic social interactions that can help, for example, gain insights into issues, trends, dynamics, and influential actors about the pandemic. For example, Graham et al. (2021) scraped tweets posted during the first 7 months of the pandemic to examine the take-up of attacks against the Australian Premier Andrews, who imposed severe lockdown measures against COVID-19. By analyzing these social interactions, the authors found that different dynamics governed the interactions within the communities of attackers and supporters: Attackers strategically worked with sympathetic media and politicians to spread their attacks on the government. In contrast, supporters endorsed a particular political cause and engaged in critical discourse.

The importance of social media data in understanding the influence of COVID-19 on activism and protest also lies in the fact that social media have become the place where activists can protest after the pandemic. Because of contact restrictions, street protests became impossible and social movements had to reconsider their strategies and develop “online-only” formats (e.g., the Fridays for Future Digital Strike on April 24th, 2020). To understand what could happen to social movements and their communication if physical protest is not possible anymore, Haßler et al. (2021) compared 46,881 tweets using the hashtag #fridaysforfuture posted before and during the lockdown. The analysis revealed a substantial impact of COVID-19 lockdown on communication activity, both in terms of tweet volume and content. According to the authors, creative, attention-grabbing, and newsworthy forms of online protest can be a useful addition to SMOs repertoires due to their virality.

Survey and interview data

The effects of COVID-19 on academia and social science research has been just as severe as on other sectors and professions. Due to the pandemic, research practices that involve human interaction, such as interviews and field surveys, are unlikely to be carried out so easily in the near future. Thus, researchers have had to adapt to these new circumstances. For example, researchers who use in-depth interviews have adapted during the pandemic by transitioning to telephonic and video interviews. The nine studies that used traditional data collection techniques (i.e., surveys and interviews) opted for an online interaction. All the surveys were administered through electronic platforms (e.g., Qualtrics; Borbáth et al., 2021; Lalot et al., 2021), and interviews were conducted virtually through media, such as Zoom and Google Meets (e.g., Carolan, 2021; Holle et al., 2021), or by telephone (Igwe et al., 2020). In one research, the authors were able to conduct face-to-face interviews (Regus, 2021).

In two research data were collected through surveys (Borbáth et al., 2021; Lalot et al., 2021). For example, Borbáth et al. (2021) administered a questionnaire to 7,579 participants from seven west European countries to assess their political and civic engagement in response to the COVID-19 crisis, perceptions of economic and health threats, and political ideology. Lalot et al. (2021) collected data through two consecutive surveys: The first survey served for measuring the main predictor (i.e., future consciousness, the ability to understand, anticipate, and prepare for the future), while the second was used to measure the outcome variable (i.e., engagement in collective actions).

Six studies collected data through interviews that were semi-structured in most cases (Table 4). For example, Regus (2021) interviewed six Indonesian women activists to explore how they coped with the changes in their practices caused by the COVID-19 disruption. In one research, interviews were conducted for validation rather than for generative purposes. Arya and Henn (2021) first collected data through ethnographic online observation of young British environmental activists to come up with a matrix of challenges and opportunities they faced during COVID-19. Then the authors conducted three unstructured online interviews to collect critical feedback and confirm that all elements of the matrix had been accurately represented.

While most of the studies relied on either survey or interviews, Carolan (2021) used both methods. In this two-wave study, which focused on the relationship between ethical food consumption and social activism after COVID-19, participants were first introduced with a survey asking their commitment to ethical consumption (e.g., making food choices based on environmental concerns) and individualized forms of political action (e.g., gardening and cooking). Then, if participants agreed to be involved in the second phase, they were interviewed on the same themes. Triangulation of survey and interview data enabled the author to use respondents' own words to help make sense of relationships noted through the surveys.

Data from existing datasets

In four studies, data were retrieved from existing databases: the Crowd Counting Consortium, the V-Dem dataset, and the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data (ACLED).

The Crowd Counting Consortium collects publicly available data on political crowds reported in the United States, including marches, protests, strikes, demonstrations, and riots. Pressman and Choi-Fitzpatrick (2020) analyzed these data to explore whether and how COVID-19 changed the Black Lives Matter collective actions.

The V-Dem dataset summarizes the state of liberal democracy in the world and was used by Hellmeier et al. (2021) to investigate protest events worldwide and pro-democracy protests.

Finally, the ACLED event-level dataset chronicles the location, date, and characteristics of conflicts and civic protests worldwide. Two studies were conducted on these data, to answer different but related questions. Bloem and Salemi (2021) used ACLED data from five countries (i.e., India, Syria, Libya, Lebanon, and Chile) to examine temporal trends of those events and evaluate changes in global awareness of COVID-19 spread. Campedelli and D'Orsogna (2021) used data from three countries (i.e., India, Mexico, and Israel) to investigate the macro (i.e., national) and mesoscale (i.e., subnational) mechanisms that govern disorder events occurring during the pandemic.

Miscellaneous

Three studies collected other forms of data. Munandar (2020) examined 20 handwritten banners expressing dissent against the local government pandemic prevention policy. With the banners, protestors took charge of the perceived lack of adequate quarantine measures by addressing verbal offense to the lower-working class who was perceived as responsible for the COVID-19 spread, and thus, imposed their own “local quarantine” using creative methods.

In the other studies, authors collected information from consulting firm reports, and cases reported by the local press or shared on social media that traced the activities of civil society and social movement organizations to contrast the crisis provoked by COVID-19. For example, Andion (2020) examined reports that mapped the initiatives of SMOs to combat COVID-19 (e.g., fundraising campaigns or in-kind donations to social assistance, purchase of protective and hospital equipment) in one Brazilian city. Similarly, with the aim of mapping initiatives of social innovation that have promoted positive social capital during the COVID-19 pandemic in Brazil, Prado et al. (2020) analyzed reports describing these actions and their developers.

Analytical approaches

Given the variability of the collected data in the selected studies, various methods and techniques were used to analyze them. Twelve articles reported using qualitative methods as methodological framework, six used quantitative methods, and five mixed the methodological frameworks (Table 5).

Qualitative methods

In most studies, qualitative methods were applied with an inductive approach which allows research findings to emerge from the frequent, dominant, or significant themes inherent in data, without the restraints imposed by structured methodologies (Thomas, 2006). To identify motivations for Black Lives Matters protest participation amid a global pandemic, Cobbina et al. (2021) used an inductive approach to analyze interviews with protesters. They found that activists emphasized the need for justice, pronounced the desire to honor the historic March, and viewed standing up against systemic racism as worth the risk as motivation to mobilize. Igwe et al. (2020) used thematic analysis to evaluate individual acts (i.e., trust, altruism, and reciprocity) during the lockdown and how these practices evolve from individual approaches to collective actions. The dominant themes that emerged from the interviews with Nigerian community leaders included the discussion of social solidarity and community action and people's perception and experience of the lockdown.

It is interesting to observe how the inductive approach was used not only to derive knowledge and meaning from interviews conducted ad hoc but also to extract knowledge from artifacts created outside the specific research context. Unuabonah and Oyebode (2021) used multimodal discourse analysis to examine political protest in 40 internet memes circulated among Nigerian WhatsApp users during COVID-19. Multimodal discourse analysis is an approach that looks at multiple modes of communication (e.g., text, color, and images) to understand how individuals interact to create semiotic meaning (Caldas-Coulthard and van Leeuwen, 2003). The analysis revealed that the memes were used to protest corruption, report perceived government deceit and insecurity toward law enforcement agencies, and denounce inadequate health facilities and other social amenities. Munandar (2020) used a sociopragmatic approach, an analytical approach that enables the researcher to understand the social constructions of meaning and knowledge from naturally occurring discourse, in this case from handwritten banners. From the qualitative analysis emerged that misperception of COVID-19 prevention was affected by the lack of evaluation by the authority in the COVID-19 information dissemination at the grassroots level. Also, it emerged that authority agents did not exercise their control to correct it, leaving the lower working class with the majority stigma and discrimination. Secondly, it was found that people are prone to use negative words that potentially hurt society cohesion. Thirdly, it was observed that COVID-19 prevention and mitigation have not followed the local wisdom that guides the community to be united. On the contrary, authority agents let society elements divide with the growing suspicion toward others, for example, by keeping the banners in their place despite the stigma against the lower-working class the banners promote.

Four studies explored the effect of COVID-19 on activisms using ethnographic methods, a research approach where researchers use engaged observation of people in their cultural setting to produce a narrative account of that setting. Arya and Henn (2021) used auto-ethnography, a method where the researcher's personal experience is used to describe and interpret community experiences, beliefs, and practices. The authors co-produced a matrix of challenges and opportunities of COVID-19 and related regimes of control for young environmental activists and researchers. Two studies adopted digital ethnography, a method that adapts ethnographic methods to study the communities and cultures created through computer-mediated social interaction. Specifically, Margolies and Strub (2021) used it to examine the Mexican musicians' community response to the coronavirus crisis. By conducting an engaged observation of performers' streamed videos and listeners' comments, they found that livestreams, though used before the pandemic, became a newly significant space for informal community gathering and cultural participation at the onset of the pandemic. Abidin and Zeng (2020) used digital ethnography to investigate how the East Asian community has utilized social media (i.e., Facebook) to engage in cathartic expressions, mutual care, and discursive activism amid the rise of anti-Asian racism and xenophobia during COVID-19. They observed that the pandemic changed the tonality of camaraderie and community to focus on sharing and teasing out other East Asian experiences of coping with COVID-19 race-based aggression. Another study (Holle et al., 2021) used a feminist ethnographic approach, which critiques the epistemological and ontological claims of objectivity and rationality while supporting that all knowledge is situated and socially constructed and therefore subjective and partial (Undurraga, 2012). This approach proved useful to explore how Queer refugee artists unsettle dominant exclusionary discourses (i.e., the “migrant other” is portrayed as almost incompatible with “national culture” while it is simultaneously pressured to assimilate) through their narratives. Also, this approach permitted the authors to shift power toward a more horizontal way of collaboration with participants as opposed to a more hierarchical research design in which the research is about participants. The results indicated that Queer refugee artists challenged hegemonic discourses at various levels (i.e., individual, communal, and societal levels), using multiple modes of reflection and creation while engaging with their in-between situatedness.

Finally, two studies used documental analysis to examine how civil society mobilized at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic (Andion, 2020) and to map initiatives of social innovation that have promoted positive social capital during the COVID-19 pandemic (Prado et al., 2020). Andion (2020) found that the performance of civil society in fighting COVID-19 has made a difference in terms of mobilized resources and promoted actions. However, at a closer look, civil society actions concentrated more on emergencies, producing scattered actions in the areas of social assistance and health support. On the other hand, the author observed the emergence of other forms of collective actions that generated social innovations, opening space for new practices of public governance.

Quantitative methods

In six studies, quantitative methods were employed. Two of these relied on descriptive analysis of collected data. Pressman and Choi-Fitzpatrick (2020) conducted a descriptive analysis on the Crowd Counting Consortium data to examine changes in the protest repertoire during the COVID-19 pandemic. Although the pandemic did not cause a dramatic change in protest, they observed three main changes in the scopes and modes of protests. First, protesters' issues of concern shifted to public health and economic policies. Second, many protesters made tactical adjustments by embracing social distancing or shifting to formats that did not require social distancing (e.g., car caravans). Finally, medical facilities became much more commonly served as a location for demonstrations. Hellmeier et al. (2021) conducted a descriptive analysis of data summarizing the state of democracy in the world to investigate the state of pro-democracy protests in 2020. They observed that the COVID-19 pandemic had limited effects on levels of liberal democracy worldwide. However, possibly due to the pandemic and state restrictions on the freedom of assembly, mass mobilization declined to its lowest level in over a decade.

Two studies went beyond descriptive analysis by analyzing the temporal trend of disorder events through regression. Bloem and Salemi (2021) performed a non-parametric local regression analysis on the ACLED dataset from five developing countries to examine temporal trends of violent conflict (e.g., battles and bombings) and civil demonstrations (e.g., protests and riots) after the onset of the pandemic. Globally, a relatively short-term decline in conflict was identified which was mostly driven by a sharp decrease in protest events. However, critical heterogeneity persisted at the country level: Some countries (e.g., India) displayed a U-shaped protest trend over the initial months of the COVID-19 spread. By contrast, countries facing multiple economic shocks over the period (e.g., Lebanon) exhibited diminishing protesting over time. Campedelli and D'Orsogna (2021) also examined temporal trends of pandemic-related disorder events but applied a different set of analytical techniques. By fitting Poisson and Hawkes's point processes (i.e., mathematical models for detecting “self-exciting” processes) on protest incidents, they ruled out that disorder events are inter-dependent and self-excited. Despite substantial diversity among countries in the correlations of events between subnational clusters (identified through a spatial clustering technique), inter-dependence and self-excitement of disorders were present also at the subnational level, indicating that nationwide disorders emerge as the convergence of mesoscale patterns of self-excitation.

Two studies used regression analysis to identify the main drivers of engaging in protest (Borbáth et al., 2021) and in collective actions (Lalot et al., 2021) during the health crisis. By performing logistic regression on cross-national survey data, Borbáth et al. (2021) evaluated the effects of threat perceptions and ideology on civic engagement, political engagement, and participation in demonstrations. The authors found that health and economy-related egotropic threats (i.e., threats that are perceived to be personal) tend to be more likely to mobilize citizens than sociotropic ones (i.e., perceived threats for society as a whole). Further, results indicated that extreme left respondents were more likely to participate in less contentious forms of political engagement during COVID-19. In contrast, extreme-right individuals were more likely to participate in demonstrations. Lalot et al. (2021) performed linear regression on survey data to establish whether future consciousness, the active and open orientation toward the future, affected their engagement in collective actions (e.g., signing a petition, demonstrating) during the health crisis. Participants with greater future consciousness engaged more in different forms of collective action. This positive engagement seemed to have translated into benefit for the self, as these participants also reported greater perceived well-being and hope, and less emotional blunting when contemplating the future.

Mixed methods

Five studies addressed research questions by combining qualitative and quantitative approaches. One of these studies analyzed data derived from surveys and interviews (Carolan, 2021), while the others relied on data from social media activities (Graham et al., 2021; Haßler et al., 2021; Haupt et al., 2021; Hunt, 2022). This last group of studies made use of many analytical approaches, possibly because of the nature of the analyzed data, i.e., tweets. In fact, one tweet brings with it a variety of information, such as the account that published it, how many times it was retweeted, and its content. Thus, tweets can only be effectively leveraged using a mixed approach. For example, Graham et al. (2021) examined tweets against and in support of the Australian Premier using descriptive analysis, qualitative analysis and sentiment analysis of tweets content, and network analysis of hashtags and account profiles. Haßler et al. (2021) analyzed tweets mentioning #fridaysforfuture through descriptive analysis, topic modeling of their content, regression analysis to predict activity on Twitter, and spot changes of hashtags use before and during the lockdown. Hunt (2022) examined Twitter activities of SMOs accounts before and after COVID-19 onset by using descriptive analysis of the amount and frequency of tweets and qualitative thematic analysis of tweets content.

Compared to the studies presented in the previous sections, the studies that analyzed social media activities through a mixed approach also used machine learning techniques. To gain insights into whether and how the debate around Fridays for Future changed during the lockdown, Haßler et al. (2021) analyzed 46,881 tweets containing the hashtag #fridaysforfuture over time using the latent Dirichlet allocation, a topic modeling technique. Three topics emerged: tweets calling to action, tweets for discussing activities and exchanging arguments, and tweets on opinions about the (de)legitimacy of Fridays for Future. Haupt et al. (2021) used a different topic modeling technique to identify common threads in tweets, the biterm topic model. They used it to identify and exclude clusters of tweets that included the word “liberate” in the text but were not user-generated or did not express attitudes and behaviors of users who associated or had opinions about the Liberate movement (i.e., tweets from news/media organization and public service announcement tweets).

All in all, from a methodological viewpoint the review showed how by and large researchers adapted their methods to the extraordinary circumstances, often resorting to approaches that were already tried and tested in academia, albeit not necessarily in their specific practice. So, continuity is seen in the methodological approach but novelty can be traced in the application of the specific methodological approach to addressing research questions. Even in the case of Arya and Henn (2021), whose paper purports to explore the methodological implications of COVID-19 for ethnographic work, the authors suggest in the discussion that this is a less-than-optimal solution due to the exceptional circumstances in which ethnographers have “been removed from their field sites” (p. 13). An interesting question here pertains to the very nature of online activist communities and the appropriateness of an adapted ethnological approach to their study. Indeed, scholars in media and communication have developed methodologies uniquely designed for the study of online communities (“netnography”—see, e.g., Kozinets, 2015). It becomes therefore interesting to understand whether and how ethnography and netnography can capture different aspects of online activism.

Discussion

Our review shows how research so far has been concerned with both continuity and change in understanding activism during COVID-19. Continuity, in the sense that researchers have adopted existing theoretical and methodological paradigms to understand whether, how, and to what extent people's engagement in political action has been impacted by COVID-19. Change, because researchers have had to come up with novel methodologies to overcome the limitations imposed to try and limit the spread of COVID-19. Theoretically, some novel insight has emerged from qualitative work in the area, but there is still the need for a theory that brings together systems, groups, and individuals in explaining how social issues are progressed in the midst of a crisis. For example, combining theoretical frameworks such as Cammaerts (2012) mediation opportunity structure with a community-based adaptation perspective would be a fruitful endeavor in this sense. It would allow, for example, to understand whether, how, and to what extent the media and technological landscape in a particular region would foster the populations' adaptation strategies and civic engagement in facing crisis scenarios. At the same time, it would also allow—in line with Cammaerts (2021) analysis—to understand whether and to what extent crises such as the emergence of a pandemic or a natural disaster can change the very ontology of a social movement. A similar approach was taken by Hunt (2022), who combined Crisis Exploitation Theory with Discourse Opportunity Structure in understanding anti-abortionist movements. However, it would go further in that the crisis here would not be seen as an “accident” to exploit, but rather as part of the very fiber of social movements and their ontology. In our opinion, this calls for a truly cross-cultural and interdisciplinary approach, in which scholars get together driven by the questions, as opposed to the subject or the method of preference.

Another important (and related) theme for reflection concerns the definition of political activism emerging from the articles included in this study. The reviewed papers highlight how the definition of “activism” in academia is quite broad: Also in this case, we view aspects of continuity and change, whereby both traditional forms of activism (such as street protests and signing petitions) and other activities (such as community support or participating in art projects). All in all, this supports our argument concerning political activism being “any behavior the citizen takes as a member of a community for the benefit of the community.”

In 2016, in her editorial to the Special Issue: “Understanding Activism,” Kende formulated five propositions about the implications of activism research for science and society. These propositions are highly relevant for understanding the results of the present review.

First, Kende noticed that some forms of activism, like extreme right-wing movements and reactionary mobilizations, are present and effective in real life, but are more rarely addressed in scientific studies. Kende highlighted the importance of investigating all types of movements and called for a broadening of the scope of research to the full variety of goals that activism can have, and the means used to achieve them. It emerges from this review that the studies that investigated activism in the context of the pandemic analyzed a variety of topics. Considering those who tackled pandemic-related activism, an important proportion addressed forms of solidarity (Andion, 2020; Igwe et al., 2020; Prado et al., 2020) and community making (Margolies and Strub, 2021), others addressed pandemic-related disorders (Campedelli and D'Orsogna, 2021), offline (Munandar, 2020) and online protests (Graham et al., 2021; Haupt et al., 2021). The studies that did not address pandemic-related topics were predominantly oriented to the investigation of activism that promoted positive social change (environmental activism: Arya and Henn, 2021; Haßler et al., 2021; political dissent: Unuabonah and Oyebode, 2021; ethical consumption: Carolan, 2021), but, in line with the call for the need to broaden the scope of activism research to include movements with antagonistic scopes, we also find the work of Hunt (2022), that investigated both pro-abortion and anti-abortion social movements. Turning to the five studies that have not addressed activism linked to a particular objective, but instead the modalities of activism expression and whether/how this was affected by the pandemic, three focus on protests (Pressman and Choi-Fitzpatrick, 2020; Bloem and Salemi, 2021; Hellmeier et al., 2021), whereas one also considers, besides public protests, also a variety of other expressions of political (i.e., signing a petition, contacting a politician and posting/sharing political content on the internet) and civic engagement (i.e., helping in the neighborhood, donating money), and a final one (Regus, 2021) investigated the impact of the pandemic on the activists' lives and strategies.

Based on this glimpse of results, can we say that researchers have responded to the call of Kende to investigate a wider and more comprehensive range of forms of activism? We believe that the response should be a “Yes,” but a hesitant “Yes.” Indeed, the studies focused on specific topics of activism were often related to the interests of the researchers, who at times were activists themselves. This can have the result of drawing attention (and research) to certain types of movements and causes rather than others. To better understand the dynamics of activism, it is useful to conduct research that, instead, compares movements with opposite objectives. The study of Hunt (2022), and that of Haupt et al. (2021) investigating movements with antagonistic goals, are notable examples of this kind of research.

In her second proposition, Kende (2016) highlights that too little is known about the psychological processes distinguishing the two types of activism, and how volunteerism is an important factor that can both bring social change and maintain existing intergroup hierarchies. Therefore, she notices the necessity to include in research on activism both protests and service-type activism (i.e., volunteerism). The present review shows that researchers have followed this need to investigate volunteering as a form of activism, especially in those studies that investigated the response of activists to the needs caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. Interestingly, these same studies highlighted an important aspect of this collective response to the common societal need: namely that this response was often based on pre-existing elements, that at times had to be innovated due to the contingent situation, showing a balance between continuity and experimentation.

The third proposition of Kende (2016) addresses the importance of social media use for activism, and how social media can cause a qualitative change for activism. Five years after her Editorial, we can safely conclude that researchers have taken on the importance of considering the online context in the study of activism. Indeed, various studies have investigated online forms of activism (Abidin and Zeng, 2020; Borbáth et al., 2021; Graham et al., 2021; Haßler et al., 2021; Haupt et al., 2021; Unuabonah and Oyebode, 2021; Hunt, 2022). Even more interestingly, two of the studies went one step further and investigated the consequences that the obligatory transition to online activities, related to the pandemic-related restrictions, caused to activism: Margolies and Strub (2021) examined the formation of an online community, in place of the preexisting live meetings, and discussed how this was an example of continuity and transformation (for example, the new online community transcended the borders between USA and Mexico). Arya and Henn (2021) investigated the perceived challenges and opportunities that the pandemic posed to environmental activism and specifically addressed the qualitative impact of the increased use of online spaces.

Kende's (2016) fourth proposition emphasizes the importance of diversifying methodological choices to grasp the various levels of influence and understand both the universal human and contextual aspects of activism. In her view, the plurality of the methods, along with the diversity of the questions, enables researchers to understand activism in different political and cultural contexts, on different social issues, and thus, to get a more comprehensive picture of activism. The studies considered in this review responded to this call as a wide variety of methods have been used, in terms of types of data collected (e.g., survey and interview data, social media activities, ethnographic observation, reports, and institutional data) and statistical approaches to analyze them (e.g., text analysis, descriptive and predictive statistical analysis, machine learning). Thus, the methodological landscape is characterized by elements of continuity and transformation as both traditional and innovative methods were adopted to study traditional and innovative forms of activism.

Kende's (2016) fifth proposition calls for researchers' active engagement with the responsible application of their work. In Kende's words, “social scientists can therefore directly serve activists' goals” (p. 406). This proposition can be problematic if taken at the surface level: does it mean that if we study the anti-mask movement we are supposed to help them better achieve their goals? Kende is acutely aware of the ethical tensions implied in her statement and she spends time clarifying how the proposition concerns the duty to ask questions concerning the nature, implications, and potential consequences of the work. It also invites researchers to reflect critically on the extent to which the alignment of the group of study with the researchers' own view might influence the questions asked, the methods chosen or the conclusions drawn from the data. Overall, the current review supports the idea that scholars are indeed engaging with both the issues of application of their work and the critical appraisal of the consequences of their work for social well-being. While some authors maintain a detached approach and present themselves as simply “documenting trends” (Bloem and Salemi, 2021), in general the papers included in this review illustrate a constant dialogue between academics and activists, as well as between academics and stakeholders in general. For example, Graham et al. (2021) analyze two competing hashtags aligned to a left-wing and right-wing response to the Victorian State Government handling of COVID-19. But rather than applying the lessons learned to promote a particular cause or reading of the situation, their paper concludes with an appeal to journalists and stakeholders inviting them to further engage on the issues of misinformation and fake news, a strategy unveiled by the study itself. The use of the verb “implore” in their appeal to journalists and stakeholders, however, illustrates the difficult relationships and dynamics between academia, media, and politics. Similarly, Borbáth et al. (2021) present a “plea” (p. 320) to consider the multifaceted and complex impact of COVID-19 on different groups' abilities to participate in civil society. These terms seem to suggest that (as it has often been the case—for example in the case of the Climate Crisis) the authors do not expect to be heard, rather they are begging for their voice to be heard.