- 1School of International Relations, Guangdong University of Foreign Studies, Guangzhou, China

- 2School of International Relations, Xi'An International Studies University, Xi'An, China

- 3School of Geography and Environment, Jiangxi Normal University, Nanchang, China

In recent years, Afghanistan has experienced sustained political instability that is rooted in a relatively low level of modern nation-state building. The traditional tribal and Islamic conservationists are too powerful and restrict the process of nation-state building in Afghanistan. The logic behind a traditional tribal society and a modern nation-state is different, and their power has inherent contradictions in terms of attributes, vectors, and fields of action. The religious conservative tendency fetters the modernization of Afghanistan in different aspects, and the absolute religious right negates national power in concept. In reality, the localization of teaching law eliminates national ability, and fundamentalism stifles the vitality of society. The tribal and religious policies of the new Taliban government will shape the future of Afghanistan politics.

Introduction

In 2021, the Taliban regained control of Afghanistan after 20 years, which made a considerable impact in both the political and academic realms. Afghanistan is one of China's land neighbors and is also included on the list of the least developed countries published by the United Nations. Due to the continuous social unrest and a collapsing economy, the direction of Afghanistan's politics has become a popular issue in academic circles.

At present, research on the domestic turmoil in Afghanistan mainly focuses on the following two aspects: First, there are still several tribes in the country with relatively balanced forces, seriously restricting Afghanistan's progress toward a modern nation-state. Second, traditional religions have not achieved modernization and represent a spiritual factor impeding construction of a modern country (Liu, 2006; Huang, 2008; Yang and Wan, 2015; Wang, 2016; Chang, 2018; Yan, 2021a). The literature reflects that the discussion of the Afghanistan issue by Chinese scholars has hit the key points in the contributions of history, sociology, anthropology, and other fields. However, the building of a modern nation-state belongs to the field of political science and research in this area is still rare. Thus, this article aims to fill in this gap.

In modern Afghanistan, wars continue and social development is stagnant. Generally, scholars believe that the root of these challenges is the low level of modern nation-state building in Afghanistan. Nation-state theory is an important part of modern political science. Although the theoretical boundaries of political science have been greatly expanded, the “state” remains the core issue of the discipline. In addition, new political research methods have also promoted the further development of state theory. At the end of the last century, the rise of institutional research brought the “state” back to the center of the theoretical field, and new theories, methods, and perspectives enabled contemporary scholars to re-examine the state more comprehensively and deeply. Thirdly, modern political science originated in Western Europe and matured in North America. “Western-centrism” has become a key note of modern political theory; however, the problems arising in the political development of various countries are both realistic and specific. Therefore, the embarrassment of “accommodating facts to the theory” is inevitable in contemporary comparative political research. Contemporary Afghanistan is often regarded as a “failed state” (Fukuyama, Ghani), and its historical development and reality reflect the difficult process of building a modern state. Contemporary political scholars can re-examine the validity of modern state theory by observing Afghanistan.

The theory of modern-state originated from the last decades in the twentieth century, which was the result of observing and thinking on emerging nation state in Western Europe after tenth century. Nation state is the formation of modern state, which have been the absolutely prominent style of state in the last centuries around the globe. It is the most obvious trend that the lasting concentration of power within specific regions during the process of the formation of the modern states. The monopolization of political power gradually made the other powers, which used to affect public life, marginalized, even disappeared eventually. There was the confrontation between the churches and the kings in the formation of modern states in Western Europe provided the notes for the monopolization of political power. There is an obvious trend for power-centralization in modern state building, and the ultimate aim of the process could be presented as the integration of diverse groups into the specific nation, and the mutual recognition among members of various ethnic groups, the socio-economic integration into a unified market, both the sellers and the buyers could benefit from it, and so forth. it is key point that there should be a strong central authority within the country, in other words, the highly centralized central government is the driving force to promote the modern state's building. And the driving force, also known as the state capacity, which directly determines the maturity of a modern state.

Modern state theory argues that insufficient state capacity is a key factor in continuing social chaos. Scholars have made theoretical contributions on “national capability” from different perspectives (Migdale, 1988; Wang and Hu, 1993; Wu, 1994; Yang, 2005). Here, the basic meaning of state capability is defined as the state's ability to transform its own will into real political effects. The most effective way for an agent to transform its own will into actual results is to use violence, including direct and indirect threats. The state is a realistic and specific power (violence) organization formed through social development. It needs to draw resources from the social matrix to maintain its own existence and development. Compared to coercive capacity, social absorptive capacity plays a more fundamental role. A lack of national capacity is reflected in the following two situations: First, the lack of national coercive power. The necessity of the state is reflected in the use of monopoly violence to eliminate potential social violence and to achieve “violence against violence”. The root of political instability is the state's failure to achieve a complete monopoly on violence. Second, society has not produced enough resources to allow the development of the coercive power of the state. Insufficient social development, especially in economic production capacity, makes it difficult for a society to accumulate enough material and spiritual resources for the country to use, which objectively causes the country to be weak. As far as the current situation in Afghanistan is concerned, the two situations discussed above both exist and interact with each other. In regard to the state–society relationship model, modern Afghanistan should be placed in the “weak state–weak society” quadrant (Migdale, 1988). The question then arises: What leads to the dual weakness of the Afghan state and society?

The so-called strength of a state and society, except for the dimension of co-relation, should also be considered in terms of time. The theory of historical evolution suggests that societies and countries have their own logic and processes of self-improvement, reflecting a developing trend from low to high, from simple to complex. Firstly, the building of a nation-state is reflected in the development process of the “state” from weak to strong. “The nation-state building is the dual process of ‘nation-building' and ‘state-building', which embodies the characteristics of ‘state' and ‘nation' building and the dynamic process of nation-state. We can use it to summarize the modern process of social-political changes framed on a territorial scale around the world. It seems more appropriate to use it to refer to changes in non-Western societies, where “nation-building” and “state- building” are superimposed and carried out simultaneously. In other words, in the process of nation-state building, nation building and state building are two aspects of the same trend. The modern nation is seen as “an imagined political community. It is imagined as an intrinsically limited, but also sovereign community” (Anderson, 2006). The development of human society is reflected in the dual process of the deconstruction of blood kinship and the building of political organization. The social form of human blood kinship starts from the family and naturally expands to a tribal society through stages defined by clans. Tribal society is the loosest kinship organization, and, logically speaking, it is also the last stage before the demise of this organizational form. “Since the establishment of the modern state in 1747, successive rulers of Afghanistan have taken different measures to build Afghanistan's nation-state, but they all failed” (Wang and Yesir, 2018). Until recently, tribes were still considered essential social units in Afghanistan. There is a profound tension between the tribal power condensed through natural blood networks and the artificially constructed modern nation-state and the monopolistic violence on which it depends.

Secondly, social development is affected by many factors; however, in premodern societies, religious factors are very important. Religion is a complete system of social consciousness formed under specific conditions, and it exerts an important influence on the life and way of thinking of the majority of believers. Before the introduction of Islam to Central Asia, the locals were mainly tribal groups and the development of their society lagged obviously behind other civilizations in the same era. “At that time, various beliefs and superstitions coexisted in Afghanistan. The field of religious life and political life were separate to each other, showing a chaotic situation” (Peng and Huang, 2000). With the conquest of the Arabs and the rule of the Persians, Islam gradually became the mainstream religion in Afghanistan and came to play a decisive role in the local political and social life. The popularity of Islam encouraged the local residents to generally eliminate barbarism and ignorance and drove the development of society, which is of great historical significance. In contrast to the formation path of modern states in western Europe, since the establishment of the Durrani Dynasty in 1747, Islam restricted the development of Afghan society in the process of constructing a modern nation-state. Subsequently, it delayed the formation and development of the modern state of Afghanistan. The following two sections explore these issues further.

Power hedging of social organizations: Attributes, vectors, and fields

Marxist political science clearly points out that the essence of the state is a violent tool for the ruling class to maintain its own ruling order, and “violence theory” constitutes the core content of the Marxist state theory. Although many scholars may not fully agree with this point of view, the important role of violence in the different aspects of the process of state building has been clearly demonstrated. Max Weber defined the state as an entity with a monopoly on the legitimate use of violence. Tilly saw coercion as one of the two major forces shaping modern European states and suggested that this coercion is based on actual violence (Tilly, 1993). Mann also argued that war plays a very important role in state building (Mann, 1986). Burke believes that war has played a fundamental role in the formation of European countries and in their subsequent process of becoming strong (Burke, 1997). In contrast, in Afghanistan, since the founding of the country, the central government has continued to be weak, the national capacity based on coercion has obviously been insufficient, and social development has been slow. The reason for this is the existence of several powerful tribes within the country. Both traditional tribes and modern nations are products of social development and have inherent requirements for self-existence. These two types of social organization have different historical stages, generating logics, and operating laws. In the real political scene, this is reflected in the hedging of organizational power, which is embodied in the endogenous contradiction between the attributes, vectors, and fields of the action of power. As far as the political process of modern Afghanistan is concerned, the actual conflict between the two powers is reflected in the fact that the state power has always been unable to effectively integrate traditional tribes into a modern nation; Afghanistan has presented this kind of politics in a “strong tribe–weak state” pattern.

The power attributes of the tribe and the state

Power is one of the most important social relations in human interaction. In premodern society, power was formed in the relationship between elders and children through blood ties, which is profoundly different from the state power formed on the basis of violent coercion in modern society. To analyze the attributes of these two kinds of power, it is necessary to systematically examine the specific situations in which they are generated.

Tribal society is a continuous expansion of the natural blood-related organization—the family. Social organizations such as clans and tribes are products formed based on the natural expansion of human blood ties, and emotion is a fundamental element in maintaining these structures. Afghanistan is located at the “crossroads of Central Asia” and has been repeatedly invaded by foreign powers over its history. Ancient Aryans, Persians, Turks, Mongols, and Indians all conquered the land and their descendants thrived there. The Afghan constitution, introduced in 2004, recognizes 14 tribes in the country. It is estimated that Pashtuns account for more than 40% of the total population of the country, Tajiks for nearly 30%, Uzbeks living in the northern region and Hazaras living in the central plateau each account for 10%, and other minority tribes are <10% (Huang, 2013). From a global perspective, Afghanistan is the most distinctive example of a tribal society, of which the Pashtuns are the most typical. This article takes the Pashtuns as an example to explore the internal structure of a tribal society and its power formation.

In contrast to the flattened structure of modern society, the Pashtun social structure reflects vertical blood relationships, which is also called segmentary lineage society. Segmentary lineage society is a premodern social organization form. The key factors in maintaining this organizational structure are blood and kinship. This close relationship enables all levels within the clan to achieve mutual nesting and form a network structure. When threatened, a powerful force can be generated from within the network.

Among the Pashtun tribes, the family (خانواده) is the “base” and the smallest unit. Three or more generations living in the same house are considered a (large) family (سترده خانواده), and the member with the highest seniority is respected as the parent and has the right to make decisions. Several (large) families linked by the same blood line form a clan (خوشاوند). According to research, a medium-sized Pashtun clan usually has a population between 15,000 and 20,000 (Glatzer, 2002). Several clans form subtribes (نسل), which, due to the sizeable number of members, assume part of the military combat function. A tribe (قوم) is the blood unit at the top of a tribal society. A common ancestor, leader, and homeland are basic conditions for tribal identity. As the family gradually rises to the level of the tribe, the ties of blood and kinship become weaker, the need for collective security becomes stronger, and the political color becomes more intense.

Although some characteristics of the political state are reflected in high-level blood organizations, there are still essential differences between the two. The organizational structure within tribal societies is maintained through bloodlines. Though blood-connected families, clans, and other organizations can provide a certain degree of security, it is difficult to meet their needs and expectations for lasting security. The emergence of the modern nation-state is a historic response to the need for human security. Organizational violence in society is either validated as a part of state violence or eliminated as “illegal” “gangs”. The central government is the sole owner and user of this monopoly on violence. In order to seek their own safety, citizens give up the right to use violence freely. The state guarantees the effective operation of social life, such that material civilization, spiritual civilization, and institutional civilization can survive under the protection of state violence. In order to maintain its own security, the state, on the one hand, continues to eliminate existing or potential organizational violence within its territory and provides a stable order that is conducive to social production and life; on the other hand, it actively uses various means to create a sacred image and supreme authority that is detached from other social organizations. With the development of science and technology, the state strengthens its own monopoly on violence and gains national loyalty in a wider and more efficient manner. Historically, in its self-evolution, the state possesses a violent monopoly power and efficiency that are absent in other organizations, and this trend will continue.

The construction of the contemporary Afghan state has encountered many obstacles. The root of these challenges is the organized violence condensed by blood in the tribal social structure, which continues to challenge and eliminate state power. Traditional tribal power is distributed throughout the whole society in the form of kinship roots, especially in vast rural areas. Multiple power subjects can use organizational power to eliminate state authority at several points, which has become the deep-seated reason for the repeated setbacks in modern state building in Afghanistan.

The power vector of tribe and state

A “vector” in physics covers the two dimensions of force and direction. This paper uses this concept to explore the difference between the two powers of tribe and state. Firstly, the organizational identity within a tribe is established based on blood kinship, and differences in blood relationship lead to different rights and obligations among kin. In the age of civilization, human self-production and intergenerational reproduction have formed a differential structure that can be accurately identified. Within a family, the blood relationships directly define the corresponding rights and obligations. The closer the bloodline is, the clearer the responsibility for mutual protection; with a more distant bloodline, the responsibility is weakened and may even become the opposite of family affection, developing into a competitive relationship. This is embodied in a popular saying in the Arab world, “I am against my brother, my brother and I are against cousins, and our brothers are against all strangers,” which vividly reflects the order of relations formed by blood and its enemies. It should also be noted that since the family is the “base” of the tribal social structure, the order of power transmission is from bottom to top and flows to higher levels, such as the clan and tribe. “A leader (of a tribal society) cannot gain the firm support of other groups outside the kinship network and act on his orders, so no matter what the leader's past achievements are, they are always at the mercy of their supporters”. Political states are the opposite. State power is exercised uniformly by the central government, and administrative power is transmitted from top to bottom according to the bureaucracy. The powers of local administrative departments come from the delegation of authority from higher-level agencies, especially in countries with a unitary power structure. The power of the national government flows unidirectionally from the center of political power to all grassroots places across the country through the use of force and is used to suppress, quell riots, promulgate laws, and appoint or remove officials.

Due to the power hedging between the tribe and the state, the laws and regulations promulgated by the government in Afghanistan have always had a very limited impact on society. In order to maintain sovereignty and integrity, the central government did not hesitate to transfer part of its power to the tribes. This situation was reflected as early as the establishment of the Durrani Dynasty, which laid the foundation for modern Afghanistan. In 1747, 25-year-old King Ahmad Shah was elected by the Pashtun, Tajik, Hazara, and other tribes through consultation and election. As the supreme ruler, Ahmed knew that a monarchy formed by the pooling of power from the bottom up was difficult to secure. When the Islamic cleric “proclaimed to call him ‘Badashadur-i-Dauran' (King, Pearl of the Age), he used only ‘Dur-Ilam-Duran' (one of multiple pearls), to indicate that he was on an equal footing with other tribal chiefs” (Peng and Huang, 2000). Since that time, the development of the modern state of Afghanistan has repeatedly shown that when the two powers with different vectors hedge each other, it is difficult for the political state to exert its political will throughout the grassroots society. This situation continues to this day.

The power fields of the tribe and the state

The spheres of tribal power and state power are also different. Tribal society is composed of many tribe members, and the source of strength comes from the identification and loyalty of individual members to the tribe. When the collective identity of clan members begins to weaken, their internal cohesion also declines, and the overall strength also weakens. Tribal power is attached to the group itself, and the historical migration of a tribal group changes the field of its power. However, as a historical product developed by a tribal society, the political state has clear and specific geographical limitations in its power space. Territory is the spatial basis for political social groups to organize public life and, together with population and sovereignty, constitutes the basic elements of the existence of a state. In the process of the continuous evolution of the state, a notable feature is that the territorial scope is more clearly defined. In premodern times, conquest by force was the most important and effective way to expand territory. The borders of a country are the furthest limits that the central regime has conquered by force. In other words, the national border is the power-dividing line at which the central government encounters effective resistance in the process of military expansion. In premodern society, due to the constraints of technical resources such as transportation and communication, it was difficult for the political influence of the central government to penetrate directly into the frontier grassroots areas. Therefore, the principal-agent method was often adopted to authorize local tribal leaders to exercise indirect rule. The limited political influence of a central government on the frontier areas makes it difficult to precisely demarcate a country's territorial boundaries. With the development of social productive forces, especially the advancement of transportation technology, this situation was greatly improved. More convenient transportation strengthens the connection and interaction between a central government and its frontiers. Political education and political absorption begin to play a role, and the national will penetrates the frontier regions. From a micro perspective, the residents of the vast frontier begin to learn the rules of the central government, accept the political culture dominated by the government, and recognize the political concept of the unity of power and responsibility, and a modern state is formed.

Logically, tribal society and the political state are different stages of time-logic development. However, in reality, the power struggle between the tribal society and the political state never ceased. Historically, clans have always been powerful blood-related organizations, and neither city-states nor huge empires have been able to completely eliminate clan power; thus, the power fields of clan and state do not necessarily overlap. The modern nation-state is formed through the integration of traditional tribes, and the power of the tribe is transformed into the power of the nation-state with the demise of the tribe. However, in the contemporary world, clans still exist within many countries, and it is common for the same clan to live across borders in two or more countries. For the same tribe located on both sides of a national border, naturally, its power function is not limited by the border, which makes these boundaries less clear. In addition, this also objectively causes the cognition of the “country” of tribal members to remain in the “distant and hierarchical capital”. However, modern countries require the precise placement of power within their borders and require the public to construct a clear concept of the “country” to realize their recognition and respect for national power.

In reality, the power fields of tribal society and political state overlap, rub, and collide due to their different interests, which is considered to be an important factor in the outbreak of tribal wars in modern society. As far as Pashtuns are concerned, although they are the largest tribe in Afghanistan with a total population of 13.75 million, neighboring Pakistan has 25 million tribal compatriots, accounting for 15.42% of the total population of Pakistan. Historically, Afghanistan, Britain, and Pakistan have experienced friction over the “Pashtunistan issue”. During the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan, the Pashtuns used Peshawar in Pakistan as a resistance center and launched attacks on the Soviet troops stationed in Afghanistan. Coincidentally, the Tajik political forces, represented by Ahmad Shah Massoud, also interacted with their foreign regimes at the political and military levels. There is a profound contradiction between the mobility of tribal power and the limited space of political and state power, which has also become an important perspective in analyzing the frequency of wars in Afghanistan. How to effectively integrate the multisect tribal forces in the country into a homogeneous nation is undoubtedly an important issue that must be addressed to achieve lasting peace in Afghanistan.

Religious conservation: Faith fetters in modern Afghanistan

Looking back at the history of Afghanistan, it is not difficult to see that Islam, as a powerful spiritual force, has played an important role in various significant historical moments. Particularly in the past 100 years, Islamic religious groups have presented an opposition to the formation of a modern nation, modern state building, and development. This increasingly conservative religious group has made nation-state building difficult, and the social development of Afghanistan has always been described as “advance two and retreat one”, or even “stand still”.

The conservative religious forces in Afghanistan have been heavily criticized by scholars, who believe that they have become a historical burden and a spiritual bondage that restrains Afghanistan's modernization process. Exactly how the clerical power constrains the state-constructing process in Afghanistan remains open to interpretation. This article attempts to respond from the three levels of national power, national capacity, and social vitality.

The absolutization of religious power and denial of modern national power

The political concept system of traditional Muslims is based on their devotion to Allah. The Kolan praises Allah, “Allah, the Creator, the Shaper, He is omnipotent and wisest”. Muslims acknowledge that Allah has the supreme authority and that the “state” is a creation of Allah, and its authority is bestowed by Allah; Allah created the nation to facilitate the daily chores of Muslims. The national law should reflect the Islamic spirit, and the function of the state is to punish those who violate the teachings and hadiths, and resolve the disputes of Muslim interests according to these teachings. For traditional Muslims, obedience to state authority in real life is a virtue of obeying the will of Allah, rather than a utilitarian consideration based on enjoying rights and fulfilling obligations.

The formation of the Muslim concept of “Allah's sovereignty” has special religious and historical roots. In 622 AD, after the Prophet Muhammad led his believers to move to Medina, he established the first Islamic commune in the area, namely Ummah (which means commune and nation in Arabic; Sha, 2013). The Prophet declared that Ummah was established by God. Allah was the supreme leader, and that he had both the supreme legislative and executive powers, acting on Allah's behalf. Ummah implemented the principle of power organization of the unity of state and religion; however, it was not an Islamic state in the full sense. After the death of the Prophet, four subsequent successors ruled the Ummah, and thus obtained the title of “Khalifah” (خليفة, Arabic transliteration, meaning “successor” or “actor”). The centralized system of the Ummah gave the caliph nearly unlimited power, which paved the way for the sectarian struggle that followed, and the Ummah soon split. After the “orthodox Khalifah” era ended, there was no Khalifah in the Islamic world who could lead the religious and secular worlds. The Islamic regime established by the Prophet in his early years, where “religion is under the Lord, politics is under religion, religion rules politics and politics protects religion”, has become the prototype of the concept of “state” for the majority of Muslims (Mozaffari, 1987). In short, “Allah's sovereignty” is the core content and theoretical basis of Islamic political theory, while political and religious unity is the logical development and institutional manifestation of this sovereignty. In traditional Muslim opinion, no matter how powerful a ruler is, without the blessing of Allah, their legitimacy is questionable. If secular laws and policies do not reflect the spirit of Islam, or even violate the basic principles of Shariah, all Muslims can use the right granted by Allah to launch “jihad” (جهاد), overthrow the kafir (كافر) regime, and re-establish an Islamic regime with sovereignty is vested in Allah. “Jihad”, a transliteration of Arabic, literally means striving for success in studies, livelihood, career, etc. It is the Islamic religious language system that encourages Muslims to do their best to actively achieve conformation to the will of Allah and improve themselves. In recent years, Islamic fundamentalists have incited certain devout Muslims to attack non-Muslims (regimes) and relatively moderate Muslims (regimes) in the name of “Jihad”, resulting in the term “Jihad” gaining the specific designation of a “religious war” against non-Muslims, although this is a misunderstanding. “Kafir” is an Arabic transliteration referring to infidels or those who go against the will of Allah (Olesen, 1995).

Very different from the Muslim view of the state, a modern nation-state is developed on the basis of a profound critique of “theocracy”. Around the fourteenth century, some new ethnic groups with a shared language, similar customs, and similar physical appearance appeared on the European continent. In the process of self-forming, these nations gradually constructed a modern social organization—a state that could defend its own interests. The emerging nation is the logical premise of the modern state, and the modern state is an effective form of self-protection for the emerging nation. Nation and state are destined to be connected; neither is complete without the other, and both are a tragedy. The modern nation-state is a social organization formed on the basis of security principles, and its fundamental elements are embodied in material power rather than beliefs and ideas. The survival of a modern state requires the collection of rich material wealth and real power from society. “People's sovereignty” has become the nation-state's most exciting mobilization slogan. Religion, as a social ideology inherited from traditional society, contains enormous energy that can be transformed into reality. Modern countries usually have realistic considerations for religious beliefs. They do not completely deny them, but still prevent beliefs from transforming into real material forces and posing specific threats. If multiple powers appear in society, the social order will collapse, and the necessity for the existence of the state will also be challenged.

From a global perspective, modern nation-states usually adhere to the principle of “people's sovereignty” and regard it as the cornerstone of their founding. In connection with this, the “separation of religion and state” has also been enshrined in modern states‘constitutions as an important principle. It can be seen that the modern state is a product of the pursuit of secular values and rational logic derivation and it reflects the color of utilitarianism, which is fundamentally different from the Islamic regime based on the belief of “Allah's sovereignty”. The former treats religion as a private matter in the life of its citizens, while the latter places all worldliness under Allah. The modern state's denial of religious power and religious forces' refusal of the secularization of the state have become endogenous factors in political turmoil within the contemporary Islamic regime in Afghanistan.

Modern political theory is fundamentally different from the traditional Islamic teachings in its understanding of “state”. This difference in concept is reflected in the political changes in modern Afghanistan, as the central government's secularization efforts have been repeatedly frustrated. In 1919, the young Amanu'llah (1890–1960) took over as the king. Shortly after taking office, the king came to feel deeply that Afghanistan was poor and weak, and hoped to follow Turkey and European powers to implement secular reforms throughout the country. The king publicly affirmed the popular Western principle of “people's sovereignty” and established a constitutional monarchy through the constitution, basing the legitimacy of his own governance on the entrustment of the majority of the people, while he did not claim to be the earthly agent of Allah, as traditional leaders did. Although this radical political concept is in line with modern nation-state theory, it compressed the power space of traditional religions. This move seemed to remove the “sacred halo” that the king should have had; however, it actually removed the clergy's right to interpret scriptures. Amanu'llah's secular reforms brought Afghan society closer to modernity. However, it was not wise to hastily change the sensitive political–religious relationship without taking control of the military power, regardless of the Islamic character of Afghan society. In 1929, religious conservatives incited rebels to attack the king and eventually deposed him. Amanullah's secularization reform ended in failure. Coincidentally, the political strongman Mohammed Daoud came to power twice in Afghanistan and advocated for secular reforms, both of which were met with strong backlash from religious conservatives. Since then, the secularization policy of the People's Democratic Party has become more radical and even put forward the slogan of “atheism”, which angered the clerical group, and even the ordinary people who benefited from the reform found it difficult to accept. The struggle between secularization and antisecularization has repeatedly appeared in modern Afghanistan, and is essentially a realistic manifestation of the inherent tension between the modern state and theocracy.

The localization of Sharia to eliminate the capacity of the modern state

Islam arose in the Arabian Peninsula in the seventh century and quickly projected its influence to Asia, Africa, and Europe over the following 200 years, having a profound impact on human society. The rapid development of Islam has profound social and historical roots. “Islam is a religion suitable for the Orientals, especially for the Arabs, that is to say, it is suitable both for the citizens engaged in trade and handicrafts and for the Bedouin nomads”. Although the content of each religion is different, each is essentially a social ideology based on and reacting to reality. When talking about the national characteristics of Afghanistan, Engels said: “Afghans believe in Islam and belong to the Sunni sect, but they do not like to engage in superficial piety.” Islam spread widely in Central Asia, except it conformed to the local social pattern and also fell in line with the national temperament created by this social pattern. As Dupree pointed out, Afghans “believe in Allah and His Messenger Muhammad, and most of their beliefs are related to localized, pre-Islamic customs” (Dupree, 1973).

Long before the introduction of Islam, the Pashtuns formed a set of unwritten but widely circulated behavioral norms and value systems, namely “Pashtunwali” (which literally means “the Pashtuns' way”). After Islam was introduced into Central Asia, social customs that contradicted these basic teachings were eliminated so that religion could be localized. The Islamization of the Pashtuns was achieved through the doctrinal acceptance of “Pashtunwali”, the core concept of which is “honor”. In the Pashtun context, “honor” (Ezzat) not only reflects acts of bravery, responsibility, justice, etc., but also reflects the subjective recognition of the “other” in society, which is essentially an affirmation obtained by winning the social living space. There are usually three paths to earning honor. The first is to “seek fairness” (Badat), which is the minimum requirement and fundamental principle to achieve “honor”. In Pashtun society, if a debt is incurred, compensation must be paid, otherwise it will damage one's “honor”. If the matter is not serious, elders respected by both parties can preside over the negotiation and adjudicate compensation; if the injury is serious, compensation must be sought through the revenge of blood relatives. Second, kindness and generosity (Memastia) are also ways to gain “honor”. Even if one does not know a stranger, taking the initiative to lend a helping hand is seen as evidence of a precious chivalrous spirit and will be widely recognized. Third, tolerance (Natawatey) is also an important way for Pashtuns to maintain “honor”. Nomadic tribes often fight over resources, and traditional wisdom seeks to resolve disputes by forgiving enemies and helping the weak (Benson and Siddiqui, 2014; Chang, 2018; Yan, 2021b). Using anthropological analysis methods, it is not difficult to find that the behavioral norms and value pursuits of the Pashtuns clearly reflect the moral aesthetics of premodern social life. In nomadic tribes, the generation and maintenance of families and higher-level social organizations must be based on real people and property. The frequent replacement of residences and the scarcity of production and living materials require nomadic groups to maintain a high degree of vigilance for their own safety. Therefore, the concept of “justice” produced in nomadic society is often reduced to exchange and compensation in material form. The extreme form of this exchange and compensation is the revenge of blood relatives, and its essence is a negative-sum game that ignores the value of human beings. In addition, the extreme pursuit of “justice” often leads to a social ethos of being brave, fighting to the death, and refusing to compromise, which obviously does not help the formation and development of a modern country.

The combination of Islamic law and local traditional customs has enabled Afghanistan's inherent social order to gain legitimacy at the level of belief, which has undoubtedly contributed to the conservative temperament of Afghan society. Except for the period of the People's Democratic Party, the previous Khan rulers of Afghanistan all claimed to rule the country by Sharia law; although the central government tried to incorporate Sharia law into the framework of the national governance system, they failed to do so. At the grassroots level of Afghan society, clerics have an absolute right to speak in the interpretation and enforcement of laws. In other words, the law is supposed to be an institutional tool for state governance, but it is held in the hands of the conservative clergy.

The Islamic clerics in Afghanistan can be roughly divided into three categories: the “sages”, descendants of the Prophet Mohammad (self-declared), and the first caliph Abu Bokr; “piar”, who are well-known juridical scholars; and “mullah”, which usually refers to a large number of clerics who carry out activities at the grassroots level. As the mullahs are the most numerous and have a wide range of influences, this article gives more attention to them. Members of the mullah group usually come from the bottom and attend village religious schools (Maktabs) from a young age. Such schools have limited teachers and a poor quality of teaching. The content of teaching could be seen from the perspective of similar type schools in neighboring Pakistan. “Students learn scriptures through the annotations of early scholars, and rote memorization is the main way. Discussions are not encouraged in the classroom, and the content of the lectures often does not take into account the needs of modern society. For example, a famous teaching method book takes nearly a hundred pages to explain in detail how to do ablutions, and it takes students 2 months to master this content” (Candland, 2006). Young mullahs enter society after graduation and begin to use Islamic teachings mixed with “local characteristics” to help Muslims eliminate spiritual confusion and deal with secular disputes in exchange for income and fame. Rory Stewart, the current UK Secretary of State for International Development, was impressed by the mullahs he met while traveling in Afghanistan. “It has nothing to do with the central government, police, courts, prisons, or dossiers of civil and criminal law in the Western model the ‘judges' (referring to the mullahs) are often illiterate, Mixed rules with Afghan tribal customs. People from different factions, or different mullahs in a single group may not agree on the criterion of the crime and the punishment” (Stewart, 2004). In contemporary Afghanistan, due to their limited professional ability and the complex practical conditions, the mullahs understand real meaning of Islamic law in the process of its interpretation, respectively, thus reducing the social integration effect of the religion. In addition, the mullahs claim that their rulings are based on Islamic law rather than secular law; thus, their rulings are not a reflection of the will of the state. Many clerics mix various local customs in the process of interpreting Sharia law, which makes it difficult for the policies and laws formulated by the Afghan government to play an effective role within their jurisdiction. The transformation of interpretation undoubtedly reflects the negative effect of substitution and elimination.

The radicalization of teachings inhibits the vitality of modern society

As mentioned above, Islam originated in the tribal era of nomads; thus, its moral requirements reflect the value trend of this social form. For example, men should assume the obligation to protect women and children in their families, which is reflected in the Quran and Hadith and even stipulated in the form of specific realization. As time progressed, the humanistic and social environment became very different from the period in which the Prophet lived. Most Islamic countries have chosen to follow the trend of history, abandon the traditional forms and rigid procedures prescribed by the Sharia, and apply the specific social values advocated by the Prophet to modern and contemporary social life. However, in modern Afghanistan, in order to preserve their existing rights and interests, some Sharia authorities interpret the Koran and Hadith in an extremely harsh way (also known as Islamic fundamentalism) in an attempt to “nest” contemporary life into the specific norms of speech and conduct formed in the prophetic era. In Afghanistan, the number of Muslims is overwhelming, and religious conservatives interpret teachings in an antimodern way and construct the moral standards of contemporary society. This shackles the majority of believers at the social and psychological level, making it difficult to accept new ideas and new fashions that conform to modern state building in Afghanistan. In modern Afghanistan, women's rights and education have always been the core issues in the struggle between the modern state and the traditional religious power, both of which are related to the future and development of the entire country. Education issues have been outlined above, and this section focuses on the social implications of the chronic absence of women's rights in Afghan society.

Women are a natural part of human society, the source of human reproduction, and a fundamental force required to promote social development. The restriction of women's rights is an unbearable burden for society. In the process of the transition from tradition to modernity, women's liberation becomes an important way to stimulate social vitality and empower the country. The discussion of women's issues helps us to observe how the conservative tendencies of doctrines have suppressed the overall vitality of Afghan society. In the process of constructing a nation-state in Afghanistan, social reformers such as Amanullah, Daoud, and the People's Democratic Party advocated for the stimulation of social vitality by liberating women. Regrettably, these efforts had little effect. Affected by extremist religious forces, the majority of Afghan women stayed at home for a long time. They were unable to obtain a good education when they were young and married before they reached adulthood to have children and reproduce. For more than half a century, Afghanistan's population has been exploding. Statistics show that the total population of Afghanistan in 1960 was <9 million; in 2020, it was nearly 39 million. It is worth noting that during the reigns of Daoud and the People's Democratic Party, Afghanistan's population growth slowed down, and even became negative at some points. However, after the withdrawal of the Soviet army, Islamic religious forces returned to the countryside, and the population growth rate not only turned from negative to positive, but also increased with subsequent years. Since 1988, Afghanistan's population has grown at an average annual rate of 3.67%, reaching a peak of 8.79% in 1993. Modern economics points out that population pressure is an important factor hindering economic growth. When a population grows fast, the part of the total production that needs to be consumed also increases, thereby reducing production accumulation. In addition, rapid population growth makes the per capita GDP growth rate much lower than the GDP growth rate. The effect of population pressure on economic development is especially clear in densely populated areas with low levels of industrial and agricultural production (Pan, 1981). The restriction of women's rights by traditional religion has become a heavy burden on Afghanistan's economic development. The society is deeply impoverished and cannot reserve enough resources to support the building of a modern state.

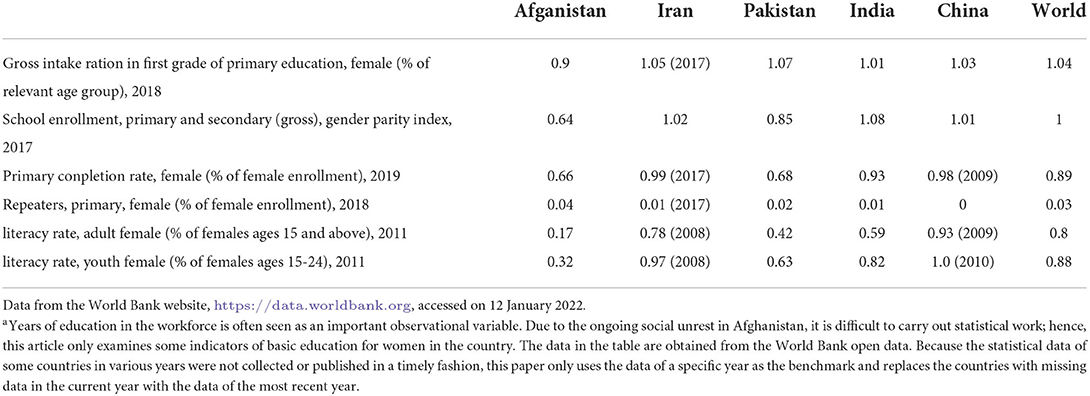

Women's rights and social status have been suppressed by conservative religious powers for a long time, which has lowered the average human capital of Afghan society as a whole and hindered the improvement of the overall development of society. Economist Theodore W. Schultz believes that “human capital” (also known as “immaterial capital”) is an important variable in achieving economic growth. “Human capital” refers to the synthesis of quality factors, such as knowledge, skills, and the health of economic value, that exist in social labor. The role of human capital in promoting economic growth far exceeds that of physical capital. The core of improving human capital is to improve the quality of the population, and education is an irreplaceable and important factor. It is short-sighted to ignore the contribution of education to income. Education is a major source of economic growth in terms of affluence through the development of modern agriculture and industry. If the vast majority of people are uneducated and unskilled, it is completely impossible to achieve social prosperity. Contemporary scholars have generally affirmed the causal mechanism where the education level of the labor force is positively related to economic growth. Overall, the education level of Afghan women is not only lower than in neighboring countries, but also has a significant gap compared with the global average (Table 1).

The continuous deterioration of women's rights in Afghanistan in modern times has become a restrictive factor in Afghanistan's social and economic development, and the resulting negative effects are obvious. The Chinese government has repeatedly expressed its hope that the Afghan authorities can effectively protect the rights and interests of women. After the 9/11 incident, the United States dispatched troops to Afghanistan and also claimed to “liberate Afghan women”. Many feminist organizations around the world have also actively spoken out for Afghan women, calling for a fundamental improvement in the living conditions of this group. The international community is generally aware that women's rights in Afghanistan need to be improved urgently, as the development of a nation without women's participation is futile.

Conclusions

This paper focused on discussion of the tribal power factor and the conservative religious authority factor in state building for Afghanistan. The tribal characteristics of contemporary Afghan society are distinctive. The power attributes and operational logic of traditional tribes and modern countries are completely different. The two social organizations often create power hedging in the process of self-sustenance. The frequent occurrence of wars in Afghanistan is an extreme form of this power hedging. In addition, in Afghanistan's transition from a tribal society to a modern state, the historic problem of how traditional religions can fit into a modern political system has not yet been resolved. In modern Afghanistan, religious conservatives have eliminated the monopoly of the state by advocating for the supremacy of religious power; used spiritual privileges to maintain the interests of the tribal societies and eroded the central power in the grassroots societies; and limited the social rights of women and other disadvantaged groups, inhibited social development, and blocked the process of state building by vulgarizing the interpretation of teachings. In essence, Afghanistan's religious conservative forces and traditional tribal forces form a joint force resisting the infiltration and control of national political power in order to achieve self-sustainability throughout historical changes.

Twenty years later, the Taliban has returned to the center of power, and the process of state construction in modern Afghanistan has been ushered into a new historical period. Academic circles generally believe that modern nation-state theory is an important perspective and an effective tool with which to observe the political situation in Afghanistan. The entry point for analyzing the future political trend of Afghanistan is still the political game between the various tribes in Afghanistan and the central government as well as the realistic impact of traditional religion on the country and society.

The first is the issue of the political rights of the tribes. The main body of the Taliban come from the Pashtun ethnic group in the southern region, and the members of the current transitional government leadership are also mainly from this region. Since the Pashtuns have a broad population base, the outside world believes that this is a positive factor for the realization of social stability in Afghanistan in the future. Historically, with the exception of the Soviet-backed Babrak Karmal, who is a Tajik, essentially all other leaders have been of Pashtun origin. Therefore, holding the power of the Pashtuns is a necessary condition for political stability in Afghanistan. If the Taliban can open up power to other tribes and form a more inclusive government, it will become more fundamental to eliminate tribal struggle and achieve social stability. In a society where tribal identity takes precedence over national identity, a central government composed of multitribal representatives is obviously more legitimate and credible. Second, the religious factors of Afghan society will also require close attention in the future. Islam is the flag and platform of the Taliban. The Taliban, after regaining power, announced that they would rule Afghanistan under Sharia (شريعة). “Sharia” is a conservative Islamic law and has severe punishments for words and deeds that violate the traditional teachings of Islam. However, it should be noted that although many Islamic countries in the world also claim to govern their countries according to “Sharia”, they actually focus more on implementing the Islamic spirit in accordance with this law and are relatively tolerant and flexible in sentencing and punishment. Therefore, how the Taliban treats traditional Islamic teachings after returning to power has important reference value for observing the future direction of the political situation in Afghanistan.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author contributions

LC contributed to conception, design of the study, and wrote the draft of the manuscript. GP and ZX collected the data and polished the article. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Anderson, B. (2006). Imagined Community: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism, Verso, Revised Edition. New York: Verso, Paperback.

Benson, B. L., and Siddiqui, Z. R. (2014). Pashtunwali: Law for the lawless, defense for the stateless. Int. Rev. Law Econ. 37, 108–120 doi: 10.1016/j.irle.2013.07.008

Burke, V. L. (1997). Clash of Civilizations: War and the Formation of European State in Europe, Hardcover Edition. London: Polity Press.

Candland, C. (2006). Religious Education and Violence in Pakistan (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 234–237.

Chang, H. (2018). Analysis of the connotation and function of Afghan Pashtowari. World Nation 2018, 72–81.

Huang, M. (2008). Analysis of the stages and characteristics of Afghan Nation-State building. West Asia Afr. 2008, 31–39.

Huang, M. (2013). The Historical Evolution of the Afghan Issue (Beijing: China Social Science Press).

Liu, H. (2006). Nationalism and National Interests: National Rebuilding in Afghanistan from the Perspective of Ethnology. Ethnic Stud. 34, 86-98.

Mann, M. (1986). The Source of Social Power: A History of Power from the Beginning to AD 1760 (CB: Cambridge University Press, Paperback).

Migdale, J. S. (1988). Strong Societies and Weak States: State-Society Relations and State Capabilities in the Third World (Princetion: Princeton University Press, paperback).

Pan, J. Y. (1981). Influence of population growth and its composition on economic development in developing countries. World Econom. 1981, 6–11.

Peng, S. Z., and Huang, Y. W. (2000). General History of Middle East Countries (Afghanistan Volume). Beijing: Commercial Press. p. 211–214.

Sha, Z. P. (2013). A preliminary study on the meaning of the word ‘ummah' in the koran. Relig. Class. Chin Translat. Res. 2013, 155–178.

Wang, P., and Yesir. (2018). Afghan Nation Building: Problems and Prospects. Xinjiang Soc Sci. 2018, pp.93–99.

Wang, S. D. (2016). Afghan political power distribution and its game in the process of transformation. Contemp. World. 2016, 51–54.

Wang, S. G., and Hu, A. G. (1993). China's National Capability Report. Shenyang: Liaoning People's Publishing House. p. 18.

Yan, W. (2021a). The dilemma of afghanistan's national rebuilding from the perspective of inter-ethnic politics. Int. Forum. 2021, 118–35.

Yan, W. (2021b). Anarchic society: The power structure and order extension of contemporary afghan. Trib. Soc. Hist. Month. 2021, 12–18.

Keywords: Afghanistan, Islam, tribal, state building, ethnic

Citation: Chang L, Pengtao G and Xiyao Z (2022) Power hedging and faith fetters: The factors of tribe and religion in Afghanistan's state building. Front. Polit. Sci. 4:976833. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2022.976833

Received: 23 June 2022; Accepted: 21 July 2022;

Published: 16 August 2022.

Edited by:

Tongshun Cheng, Nankai University, ChinaReviewed by:

Yongbiao Zhu, Lanzhou University, ChinaDovile Budryte, Georgia Gwinnett College, United States

Copyright © 2022 Chang, Pengtao and Xiyao. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Li Chang, bGljaGFuZ19nZHVmc0BvdXRsb29rLmNvbQ==

Li Chang

Li Chang Geng Pengtao2

Geng Pengtao2