- 1Faculty of Social and Political Sciences, Institute of Political Studies, University of Lausanne, Lausanne, Switzerland

- 2Swiss Centre of Expertise in the Social Sciences (FORS), Lausanne, Switzerland

We explore period, cohort and age effects on political engagement of Swiss residents from 1999 to 2020. A particular focus lies on the impact of the successive crises democratic societies have faced in recent years, such as the economic and debt crisis, refugee crisis, climate change, terrorist attacks or COVID-19 pandemic. We review the literature on the potential of such large-scale external events for both politicization and depoliticization. We then draw several hypotheses, which we test empirically. We consider several dimensions of political engagement (interest in politics, party identification, participation in popular votes, political discussions, and political trust), and seek to explain their variation over time, using data from the Swiss Household Panel. Our results suggest that “troubled times” have little effect on political engagement overall, but that crises stimulate political discussions and trust in government in the short term. We further find increasing levels of political trust in the longer run, which might reflect a cumulative effect of the various crises. In contrast, we find steadily declining levels of traditional forms of political engagement, namely party identification and participation in popular votes, as well as interest in politics. For cohorts, we find a U-shaped association between generations and political engagement. An exception to this pattern is political trust, where we observe a small but steady increase from older to newer generations. For age, we observed a monotonic increase of political engagement with age for all indicators. Again, trust in government somewhat deviates from other forms of political engagement, as it first decreases in the younger age groups and then increases from the age of 40 onwards. In conclusion, we discuss some implications of these complex patterns of results for the future of democratic systems.

Introduction

Political engagement among ordinary citizens plays a pivotal role in the functioning of democratic systems, and variations in political engagement are likely to affect support for democratic values and principles. In this paper, we explore possible causes of change in political engagement, and we thus try to specify the conditions in which the quality of democratic governance may improve or worsen. To this aim, we consider several dimensions of political engagement (interest in politics, party identification, participation in popular votes, political discussions, and political trust), and we seek to explain their variation over time, using individual-level longitudinal data from the Swiss Household Panel survey over two decades (1999–2020). As explaining factors, we focus on external events (periods), on generational differences (cohorts), and on individuals' age.

On the side of external events, it is difficult to understate the many challenges which democratic societies have faced in recent years (e.g., economic and debt crisis, refugee crisis, climate-related disasters, terrorist attacks, COVID-19 pandemic). In such crises, it is actually unclear whether ordinary citizens seek solutions through political means (including by voting for anti-establishment parties), whether they disengage from politics or try to address their private concerns in nonpolitical ways. Two opposite assumptions emerge from this question. The “politicization” assumption is that troubled times cause increases in political engagement among Swiss residents. By bringing new issues to the fore and reshaping old ones, crises stimulate the capacities of individuals to reflect on issues, to search for solutions, and to interact with political institutions and actors. In contrast, according to the “depoliticization” assumption, the inability of institutions to deal with critical problems erodes political trust and results in cognitive, affective and behavioral disengagement. These two opposing perspectives bear strongly on current debates about the future of democracy. How citizens have reacted to past difficulties is arguably helpful to figure out how they might cope with future challenges — in the environmental, energy, migration, security, or health domains.

We conceive of “politicization” and “depoliticization” as variations in the political engagement of individuals, and not as changes at the aggregate level (e.g., issues or policies). Focusing on the individual level, we distinguish three types of effects on political engagement: period, cohort, and age effects. Changes in political engagement caused by large-scale external events constitute “period effects” when the social impact of these events is so pervasive as to equally affect all age groups and cohorts. However, many causes of change apply more specifically to particular cohorts or to particular positions in the lifecycle. “Cohort effects” arise because different generations are socialized in different times, so that early life formative experiences are imbued with specific issues and risks directly relevant to each generation. In the present context, it seems reasonable to assume that younger generations have been more strongly affected by the dramatic events of the recent years (e.g., terrorism, climate change, migration crisis); accordingly, they should be more politically engaged than older generations. However, as our review of the literature will suggest, this assumption probably relies too much on unconventional forms of engagement, which may be more widespread among younger generations. Unfortunately, these forms of engagement have not been measured in our panel data. Therefore, more nuanced hypotheses about generational differences in conventional political engagement will be proposed. Finally, we take into account “age effects,” whereby individuals' position in the lifecycle is shaping their political engagement, regardless of each period and each generation's socialization context. In this respect, we expect a non-linear effect between age and politicization: political engagement increases over the life course until retirement, after which it levels off, and finally decreases during old age.

To assess variations in levels of politicization among Swiss residents, we draw on five indicators measured at several time points (political interest, party identification, frequency of political discussions, participation in polls, trust in government), and we analyze time trends by decomposing age, period, and cohort effects. We show that variations in political engagement indicators over time are limited. On the one hand, significant period effects fail to emerge; for instance, the pandemic period has produced no discernible impact on political engagement. On the other hand, for some engagement forms, there is a trend of gradual politicization corresponding to the transition from Generation X to younger generations; in addition, there is a clear aging effect (older individuals are more politically engaged). Thus, as citizens of Generations Y and Z are also younger in terms of age, they have both the lowest engagement level and the greatest potential for further politicization. Implications for democracy support will be discussed in the conclusion.

Politicization and depoliticization

We see political engagement as a general concept standing for various forms of personal involvement toward the political world and including different dimensions—cognitive (e.g., political knowledge), affective (e.g., political trust), or behavioral (e.g., political participation). For convenience purposes, we propose to define:

• “politicization” as a process of increasing levels of political engagement.

• “depoliticization” as a process of decreasing levels of political engagement.

Conceptually, both processes can be assessed against a baseline of “no change” (or “stable political engagement”). In proposing this terminology, we are aware of two major difficulties. First, there is no consensually accepted definition of politicization and depoliticization. For one thing, it has to do with the very broad definition of our concept of political engagement, which encompasses such diverse variables as political interest, party identification, trust in government, political participation, political efficacy or political knowledge. To be sure, these variables are causally interrelated to some degree1; however, there is no reason to expect that they will always evolve in the same manner and for the same reasons. For example, as we explain in more detail below, decreasing trust toward the political system can take place in times of increasing party identification. However, we argue that the politicization vs. depoliticization dichotomy is a useful way to discuss and summarize the large literature on political engagement. Quite often, this literature is reflective of the dichotomy and tends to follow the Zeitgeist prevailing at different periods of time. For example, the contemporary political lexicon is replete with terms indicating various forms of distancing from the political universe—disengagement, dealignment, disaffection, disinterest, disillusionment, disenchantment, disempowerment, or distrust. As their privative prefixes suggest, these terms convey a general feeling of loss, dispossession, and alienation from the political process. Hence, they undergird the (often untested) hypothesis that political developments of the last decades boil down to a “decay of democratic politics.” Against this background, the following sections will provide a much more nuanced account of arguments showing how and why political engagement has been both rising and declining in recent times.

A second reason why the (de)politicization concept may seem problematic is that it can refer both to something or to someone. In this contribution, we focus on the politicization and depoliticization of individuals. But we are aware that the concept of (de)politicization has a different sense in a significant part of the literature, where it refers to political issues and decision-making (e.g., Grande and Hutter, 2016).

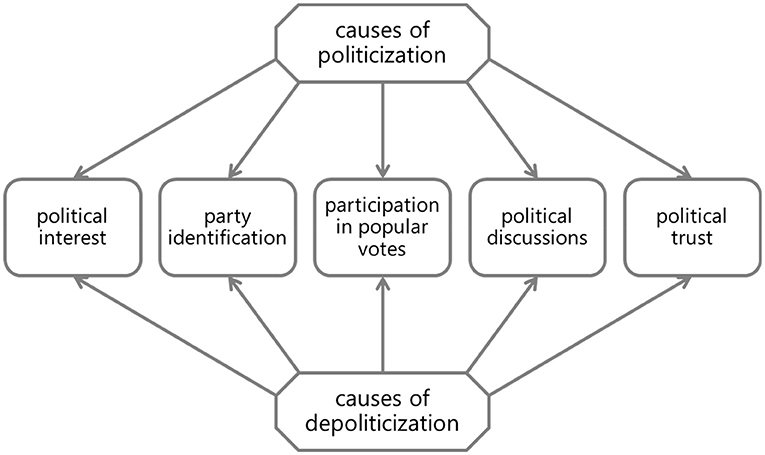

In summary, individuals' political engagement varies over time, and these variations can be conceptually distinguished as processes of politicization and depoliticization. Importantly, we argue that depoliticization is not a mirror image of politicization, and that both processes are grounded in a specific set of causes. Figure 1 represents the general framework for our analysis of (de)politicization. To look at the different effects of time, which is the key dimension for the analysis of (de)politicization, Age-Period-Cohort (APC) analysis has become a standard tool in a longitudinal framework, acknowledging the multifaceted nature of time. In the following review of the literature, we examine the factors and general explanations of (de)politicization according to whether they primarily relate to “cohort effects,” “period effects,” or “age effects.”

(De)politicization as an aggregate process: Cohort effects

One recurring pattern in the literature on political engagement is the description of a long-term depoliticization process, allegedly caused by a general phenomenon of estrangement from traditional politics. In this account, ordinary citizens no longer perceive collective political arenas as the appropriate locus for addressing common issues and problems. This loss of collective agency is believed to stem from long-term societal and economic developments, such as “individualization” (e.g., Beck, 1992; Armingeon and Schädel, 2015), “social/functional differentiation” (e.g., Kaase, 1984; Luhmann, 1990), “bureaucratization” (e.g., Alford and Friedland, 1975; Stiman, 2021), urbanization (e.g., Richardson, 1973; Geys, 2006), the waning of “social capital” and weakening of social ties (e.g., Putnam, 2000; Arzheimer, 2006), or the decline of social classes and of class-related organizations in the wake of deindustrialization and globalization processes (e.g., Clark and Lipset, 1991; Pakulski and Waters, 1996). To some extent, all these “modernization” accounts emphasize the atomization of society and the loosening of social bonds and civic duty feelings that used to yield a strong potential for political mobilization in more traditional societies. Hence, depoliticization is often considered as a generational phenomenon, in the sense that newer generations have been socialized in a context where “individuals, rather than collectives, came to be seen as the key units of society” (Grasso et al., 2019: p. 202; see also Temple et al., 2016). However, for this generational interpretation to have plausibility, political engagement should remain stable after the “formative years”—which has been disputed in some studies (see Section “(De)politicization as an individual process: Age effects”). Likewise, phenomena such as individualization or urbanization may produce effects on several (if not all) generations at once. Hence, purportedly “generational” accounts of (de)politicization provided in this section could be due to either cohort or period effects, or more probably to a combination of both.

A second view of depoliticization argues that it arises from a growing negative view of “party politics” and political institutions. Socio-economic crises, political scandals, and perceptions that politics is plagued by special interests have probably eroded the faith of citizens in the capacity of parties, governments and political institutions to solve current problems (e.g., Orren, 1997; Bowler and Karp, 2004; Tormey, 2015). The consequences are manifold: a decline of partisanship and continuing partisan dealignment (e.g., Abramson, 1976; Dalton, 2013; Garzia et al., 2021: chap. 2), a decline in party membership and trade union membership (Van Biezen et al., 2012; Van Biezen and Poguntke, 2014), and a decline in political trust (e.g., Norris, 2000; Uslaner, 2002; Dalton, 2017). In addition, the transfer of powers from local and national authorities to distant and “undemocratic” supranational institutions at the European level “has clearly played a major role in the hollowing out of policy competition between political parties at the national level” (Mair, 2013, p. 115). Likewise, arguments about the “democratic deficit” of European institutions and their related representation and legitimacy crisis have become commonplace (e.g., Thomassen and Schmitt, 1999; Follesdal and Hix, 2006; Startin and Krouwel, 2013). Interestingly, the divorce between insulated and unaccountable “elites” and the mass of ordinary citizens is part of the narratives and ideologies produced by various populist movements and parties (Taggart, 2000; Mudde, 2004; Brubaker, 2017). Therein lies the potential of populism to re-politicize party politics and society, as we argue in more detail below. In contrast, as long as grievances about the elites-citizens divide remain unarticulated, depoliticization is likely to occur.

Third, depoliticization is fostered by developments in the media system and campaign practices. Here, the key trend is the liberalization of the media sector, leading to the end of “political parallelism” between parties and subservient media outlets (Seymour-Ure, 1998; Hallin and Mancini, 2004; Udris and Lucht, 2014). The commercialization of the media since at least the 1960s and 1970s has encouraged a general focus on negative information, which broadly aligns with prominent “news values” (unexpectedness, damage, failure, controversy, etc.) and corresponds to the related need of attracting large audiences (Eilders, 2006; Strömbäck and Esser, 2014). In this “tabloidization” process, the mass media tend to frame politics as a “game” played among self-interested politicians and colluding parties (e.g., Strömbäck and Dimitrova, 2006). In turn, this fascination with strategy and the related “horserace” style of political journalism are expected to spark a “spiral of cynicism” among citizens (Cappella and Jamieson, 1997; Elenbaas and de Vreese, 2008), especially among nonpartisans and less educated individuals (Valentino et al., 2001). In addition, the rise of negative and strategic media reporting parallels a similar proliferation of negative campaigning by parties and candidates, which may also affect citizens' political engagement (e.g., Ansolabehere and Iyengar, 1995), though the existence and scope of this effect have been hotly debated for decades (see Lau et al., 2007; Haselmayer, 2019).

These claims in favor of a depoliticization process are challenged by arguments supporting the view that mass publics are becoming more politicized, at least in a historical perspective. First, at the socio-structural level, the “modernization” thesis can be interpreted in a different way. For example, urbanization may well imply a loosening of traditional bonds, but it also has the potential to increase political participation through expanding education, increased access to information, and ubiquitous exposure to political stimuli (Huntington, 1968; Flora, 1973; Shah, 2011). In addition, most mobilizing events (e.g., large-scale demonstrations, street petitions, political meetings, etc.) take place in urban centers (Rosenstone and Hansen, 1993: p. 188–196; Schoene, 2017), so that a larger share of the population is exposed to mobilizing efforts by political organizations in highly urbanized societies.

This leads to a second line of argument linking functional literacy and education to political literacy and knowledge, and hence to political participation (e.g., Marsh and Kaase, 1979; Milner, 2002; Zukin et al., 2006). This can happen in one of two ways. On the one hand, increasing education levels (along with technological development) have given rise and access to highly qualified occupations, and have fostered involvement in various (mostly non-political) organizations. In turn, according to the “civic voluntarism model” (e.g., Verba et al., 1995; Schlozman et al., 2012; Holecz et al., 2022), the skills that people acquire in educational, professional and organizational settings are transferable to the political domain. On the other hand, rising educational levels and facilitated access to political information may also trigger a process of “cognitive mobilization” (Inglehart, 1977; Dalton, 1984; Berglund et al., 2005). In a nutshell, the skills which are required for exerting political influence are no longer delegated to (and thus controlled by) political organizations; rather, these skills are (re)appropriated by ordinary citizens, who are now better able to “reach their own political decisions without reliance of affective, habitual party cues or other external cues” (Dalton, 2007: p. 276; but see Albright, 2009; Dassonneville et al., 2014). Importantly, this bypassing of traditional partisan intermediation channels is reflective of an aspiration to “new ways of doing politics” which coincided with the surge of new social movements in the 1960s and 1970s and their commitment to unconventional forms of political participation (e.g., Barnes and Kaase, 1979; Kitschelt, 1986).

If anything, the rise of unconventional forms of participation (e.g., demonstrations, boycotts) was reinforced by the simultaneous emergence of “new values” in Western societies. Although there is some debate in the literature about how to characterize and label these values (Hooghe et al., 2002), most studies share the view that the new values are rooted in emancipatory and self-actualization goals, promote personal freedoms and rights, and oppose discrimination on various (religious, ethnic or sexual) grounds. Thus, they have been traditionally connected to Green politics, cosmopolitan worldviews (e.g., European integration), human rights, pacifism, gender issues, antiracism, and the like. Therefore, even though conventional participation may be decreasing, a “new engagement” (at times more disruptive, community-based, or directed toward political consumerism) may be flourishing, especially among younger cohorts (Marsh and Kaase, 1979; Inglehart, 1997: chap. 10; Zukin et al., 2006; Quaranta, 2012). As a matter of fact, aggregate levels of political interest and political knowledge have been constant or, if anything, slightly increasing in Western democracies in the past five decades (Jennings, 1996; Delli Carpini, 2005; Prior, 2019: chap. 5; Haugsgjerd et al., 2021).

Arguably, the “silent revolution” of the 1960s and 1970s was mainly driven by societal changes and by the burst of “New Left” activism of that time. However, it has sown the seeds of many current political issues and conflicts (e.g., climate change protests), including a counter-mobilization of the radical or populist right (e.g., Ignazi, 1992, 2003; Norris and Inglehart, 2019). Interestingly, this “cultural backlash” has taken to the streets (e.g., Pegida rallies in Germany, the 2021 US Capitol assault), with the consequence that outdoor public places are increasingly becoming the meeting point of vocal movements from both sides of the political spectrum (Wahlström, 2010; Vüllers and Hellmeier, 2022). Such manifestations of overt conflict, quite often revolving around identity politics, are appealing to the media and their audiences (Kepplinger et al., 1991; Esser and Matthes, 2013; Koehler and Jost, 2019). In addition, because conflict is inherently captivating and contagious, reinforcing its intensity and visibility through media coverage is likely to attract growing numbers of participants (Schattschneider, 1960).

Therein lies the third main argument in favor of politicization: It is an elite-driven phenomenon caused by the deepening of conflicts and controversies among parties and other significant political actors. Accordingly, the degree of elite polarization is often considered as a cue for predicting politicization of the citizenry. In fact, there is some evidence that polarization stimulates (rather than dampens) participation, whether through voting or other campaign activities (e.g., Abramowitz and Saunders, 2008; Dodson, 2010; Simas and Ozer, 2021). In general, increasing party polarization is thought to be electorally relevant because it clarifies the contrast between parties and makes it easier for citizens to discern what parties stand for (Levendusky, 2010; Lupu, 2015). As party labels and reputations are “imbued with more meaning” (Aldrich and Freeze, 2011, p. 186), partisanship is facilitated (Hetherington, 2001; Levendusky, 2009), and citizens are attracted to the polls and to other forms of political engagement. However, polarization may have nefarious side effects if one looks beyond electoral participation per se. For example, ideological polarization may result in a polarization of political trust, whereby “partisans whose party is out of power have almost no trust at all in a government run by the other side” (Hetherington and Rudolph, 2015: 1; see also Carlin and Love, 2018; Rudolph and Hetherington, 2021). Thus, it is far from obvious that political trust, one important aspect of political engagement according to our definition, is positively affected by elite polarization. And those who view trust as an important element of democratic politics will take little comfort from the fact that elite polarization goes hand in hand with negative partisanship (e.g., Abramowitz and Webster, 2018; Bankert, 2021) and affective polarization among citizens (e.g., Iyengar et al., 2012; Reiljan, 2020). In short, elite polarization may well clarify the positions of the various parties on salient issues and boost participation; but it can also instill feelings of dislike and hate toward out-parties, which crystallize in negative attitudes and identifications.

The various processes outlined in this section have been addressed in different strands of literature and probably occur in parallel. In other words, politicization and depoliticization processes are likely to be at work simultaneously, so that their net effects are hard to predict. Moreover, the specific (socio-political, cultural and communication) contexts in which generations have been socialized may have different implications for different indicators of political engagement. Therefore, it is quite difficult to develop clear-cut hypotheses about how generations differ in terms of political engagement. Nevertheless, our review of existing research suggests two main conclusions. First, depoliticization processes (such as social modernization, disenchantment with party politics or media tabloidization) originate in gradual changes that have been underway for a very long time; in contrast, politicization processes (such as the rise of “new politics” and elite polarization) are more abrupt and more recent. Second, there is a fundamental distinction between measures more directly related to traditional (or “conventional”) forms of engagement (i.e., party identification, participation in popular votes, and political trust) and measures which do not clearly refer to either traditional or newer forms of political engagement (i.e., political interest and political discussions).

From there, we assume that the relative importance of politicization and depoliticization processes is not independent from the forms of political engagement. First, long-term changes such as social modernization, disenchantment with party politics or media tabloidization are expected to foster depoliticization in a more traditional sense. That is, party identification, participation in popular votes, and above all political trust should decline gradually as one moves from older to younger generations. This is because each successive generation is socialized in a context where factors of depoliticization are stronger than for the preceding generation. However, elite polarization has been under way for several decades (for Switzerland, see Linder and Mueller, 2021), and it may have acted as a countervailing force against depoliticization in younger generations—with the important exception that political trust is unlikely to be stimulated by polarization anyway.

In sum, we make the following hypotheses for our measures of traditional political engagement:

H1a: Party identification and participation in popular votes decrease from older to middle-aged generations, but do not further decrease as one moves to younger generations.

H1b: Political trust decreases from one generation to the next.

On the other hand, cognitive mobilization and the rise of “new politics” in the 1960s and 1970s should have fostered involvement in grass-roots politics among newer generations. Unfortunately, there are no measures of unconventional involvement in our data. However, political interest and political discussions should be reciprocally related to both conventional and unconventional forms of political engagement. Because interest and discussion should be more strongly associated with unconventional participation among newer generations (respectively with conventional participation among older generations), countervailing trends toward depoliticization and (re)politicization may weigh differently in different generations. Overall, we make the following hypothesis:

H1c: Political interest and political discussions decrease from older to middle-aged generations, but do not further decrease (or slightly increase) as one moves to younger generations.

(De)politicization as an aggregate process: Period effects

Period effects result from external circumstances that equally affect all age groups and cohorts. Period effects can relate to events that occur at a particular point in time or to contextual changes developing at a slower pace. Having outlined in the previous section the more linear processes taking place at the societal level, such as individualization or polarization, we now address events that are susceptible to impact political engagement in a short-term perspective, such as terrorist attacks, severe economic crises, or the recent COVID-19 pandemic2. It should be noted, however, that not all major events that stand out as “historical” in collective memory actually left a lasting imprint on political engagement of the population at large—even though they may have had other important consequences (see the example of “mai 68” in France; Pagis, 2019; Sommier et al., 2019).

A first, outstanding, example of short-term period effects is the impact of terrorism. Quite tellingly, the 9/11 terrorist attacks in New York and Washington have been characterized as “politically socializing events” (Gimpel et al., 2003: chap. 7). These attacks, but also similar terrorist acts in France, Spain or Norway were shown to fuel trust in government or other political institutions (e.g., Chanley, 2002; Dinesen and Jæger, 2013; Arvanitidis et al., 2016). The mere fear of future terrorist acts may even be enough to induce trust (e.g., Sinclair and LoCicero, 2010). Admittedly, these positive effects of terrorist threat on political trust are generally short-lived and tend to dissipate in a few months (e.g., Perrin and Smolek, 2009; Dinesen and Jæger, 2013; Arvanitidis et al., 2016)3. Less frequently reported (but also less commonly investigated) are consequences of terrorist attacks for political interest (e.g., Schüller, 2015), party identification (Wollebæk et al., 2012), or turnout and other participation activities (e.g., Vasilopoulos, 2018). Overall, terrorist acts seem to have a politicizing effect for all these forms of political engagement. Most importantly, although the effects of terrorist attacks may vary according to some individual characteristics (e.g., race and gender; see Perrin and Smolek, 2009) or to the type of emotions they evoke (e.g., Robbins et al., 2013), they usually cut across generations. This lends support to a “period effect” interpretation of observed variations in political engagement.

Second, the familiar argument that economic crises can foster politicization or depoliticization has been reinvigorated in recent times with the great recession, which started in 2008. Special attention was devoted to its consequences for unconventional political participation such as mass protests or political consumerism (e.g., Zamponi and Bosi, 2018). In this regard, the debate has centered on the validity of two competing theories—“grievances theory” and the “civic voluntarism model” (see Kern et al., 2015). The former theory argues that the politicization of economic grievances in periods of economic strain is a major path to political engagement. Widespread and increasing economic hardship and feelings of relative deprivation among European populations following the 2008–2010 economic recession have tended to fuel protest behavior (Kern et al., 2015; Grasso and Giugni, 2016; Kriesi et al., 2020). Interestingly, the effect of deprivation on protest is strengthened by higher levels of unemployment and social spending at the country level, suggesting that individual incentives for mobilization are also determined by perceptions of the collective opportunity structure (Kriesi, 2012; Grasso and Giugni, 2016). Put differently, it “takes a double crisis—i.e., the combination of an economic with a political crisis — to fuel economic protest in a given country” (Kriesi et al., 2020, p. 170). In contrast, the civic voluntarism model predicts that participatory resources (such as disposable income or available time) should diminish in dire economic conditions, so that “a lack of material resources will depress levels of participation” (Kern et al., 2015, p. 466; see also Lim and Laurence, 2015). Although empirical evidence tends to demonstrate politicizing effects of the economic crisis, it is probably premature to reject the civic voluntarism model; in particular, the hypothesis that diminishing resources lead to decreased political engagement at the individual level has rarely if ever been tested empirically, let alone with appropriate methods and data.

Another unmistakable consequence of the great recession concerns political trust. Overall, the level of public trust in political institutions and leaders has been clearly decreasing in the crisis years (e.g., Armingeon and Ceka, 2014; Bermeo and Bartels, 2014; Ervasti et al., 2019). However, at the European level, this decline has been steeper in countries which were more severely hit by the crisis and subsequent austerity policies, as well as among lower-status citizens (Armingeon and Guthmann, 2014; Dotti Sani and Magistro, 2016). Interestingly, it has been argued that a decline in political trust in times of economic crisis can derive from both egotropic and sociotropic considerations (Gangl and Giustozzi, 2018; Giustozzi and Gangl, 2021). It may stem from personal experiences of economic hardship, affecting political trust through feelings of deprivation and political alienation, and/or from general perceptions of “political failure,” feeding a loss of confidence in the problem-solving ability of democratic institutions. The fact that many individuals blame political institutions for evil that afflicts us, rather than only themselves, is crucial in explaining why economic crises should have a period effect — cutting across generational and age groups.

The COVID-19 pandemic constitutes another potentially important period effect, as it combines a health crisis with a political and an economic crisis. While the long-term effects on political engagement remain to be seen, first results suggest that the COVID-19 crisis does not stand out in comparison with the examples mentioned above. First, the pandemic has increased trust in (as well as vote intentions for) the government and general satisfaction in democracy (Esaiasson et al., 2020; Bol et al., 2021). In general, crises increase uncertainty and anxiety among populations, which may lead to increased governmental support (Bisbee and Honig, 2022). Second, the bureaucratization of governments and democracies during the COVID-19 pandemic may have provoked both strengthened support for governmental policies and a populist backlash (Bobba and Hubé, 2021; Neblo and Wallace, 2021)—this may be contrasted to the economic crisis, during which protest parties gained political support at the expense of governmental parties (see above). Third, and in contrast to the former two trends suggesting a polarization effect of the crisis (leading different parts of the population toward increased support for either governmental or populist parties), it has been shown that lockdown policies had no effect on traditional left-right attitudes (Blumenau et al., 2021; Bol et al., 2021). Results thus show that different processes take place over time: (1) a strengthening of the status quo that becomes visible through an increase in governmental trust and support; (2) political polarization through citizen frustration and resentment, and thus a rise in populist support; and finally (3) a decay of these effects in the long run.

While short-term events or “crises” are likely to affect political engagement, this is not necessarily the case. For example, looking back on the evolution of political interest in the past two or three decades (using panel data collected in Germany, Britain, and Switzerland), Prior (2019) shows little influence of particular events (e.g., crises, elections) on political interest4. However, generalizing from the case studies examined above such as the COVID-19 pandemic and terrorist attacks, we may conclude that “troubled times” tend to yield a politicizing effect. We expect “temporary bumps” in political engagement as a result of people's exposure to crises. However, this expectation does not easily extend to political trust, because a key moderating variable seems to be whether a government can be held responsible for the crisis at hand (or for its incapacity to deal with the crisis). Hence, for the sake of simplicity, we formulate the following hypothesis:

H2a: Periods corresponding to large-scale crises lead to a temporary increase in political engagement, with the possible exception of political trust.

Short-term bumps in political engagement may also be related to the electoral cycle, because the profusion of political information disseminated in the weeks or months preceding an election may boost political interest, party identification, and so forth. According to Prior (2019: chap. 4–5), evidence that the electoral cycle influences political interest is “weak,” but nonetheless consistent with the expectation that election years have a positive effect on political engagement. More importantly, similar (and sometimes not so small) effects have been found for party identification and political trust, in addition to political interest (Holmberg, 1999; Strömbäck and Johansson, 2007). To be sure, the electoral cycle is not the kind of period effects we have in mind in this contribution—suggestively, it is more akin to a periodical effect. However, our estimation of all period effects is premised on the same time scale, where the relevant unit is the year in which a survey was done. Thus, if election years do affect political engagement, their effect may be confounded with the effect of crises occurring in the same years. In addition, the position in the electoral cycle may impact the quality of survey responses, with perhaps more survey cooperation and less satisficing answers in election years (Banducci and Stevens, 2015). In sum, it seems safe to control for election years, whose effect on political engagement may be simply formulated as follows:

H2b: Political engagement is higher in election years, compared to other years.

(De)politicization as an individual process: Age effects

Age is related to (de)politicization processes in several ways. To simplify, we distinguish two areas of research, which we refer to as “socialization” and “opportunities.” First, studies of political socialization have stressed the importance of formative years and of mechanisms involved in the intergenerational transmission of political engagement. Politicization thus occurs in the sense that children acquire attitudes and habits, which are increasingly similar to those of their parents, families or immediate social surroundings (Percheron, 1985; Sears and Levy, 2003; Zuckerman et al., 2007; Wasburn and Covert, 2017). For example, political socialization in the family and in primary educational settings has been shown to shape the development of political interest (e.g., Jennings and Niemi, 1978; Arzheimer and Schoen, 2005; Neundorf et al., 2013), party identification (e.g., Campbell et al., 1960: chap. 7; Niemi and Jennings, 1991; Lewis-Beck et al., 2008: chap. 7), political trust (e.g., Jennings and Niemi, 1978; Jennings et al., 2009; Hooghe et al., 2015), and political participation (e.g., Kenny, 1993; Verba et al., 2005; Persson, 2015).

While political engagement tends to increase from early childhood into late adolescence, the transition to adulthood is generally characterized by a slowdown or reversal in this upward trend. This corresponds to a transition period where young adults are mostly preoccupied with “such nonpolitical concerns as obtaining an education, finding a mate, and establishing a career” (Strate et al., 1989: 443). This transition period usually ends with a “settling-down” process (e.g., completing education, getting a job, leaving parental home) and with the acquisition of “adult roles” such as marriage and parenthood (e.g., Krauss and Fendrich, 1980; Highton and Wolfinger, 2001; Schmitt-Beck et al., 2006; García-Albacete, 2014). Importantly, as the geographical mobility of young adults decreases after this settling-down stage, they have more opportunities to develop personal ties in their neighborhood and attachment with their local community. This will foster involvement in community affairs, as well as social trust and confidence in institutions (e.g., Jennings, 1979; Zmerli et al., 2007), which may also spill over to other forms of political engagement.

In fact, one strand of research suggests that politicization continues over most of the adult lifespan—another strand focusing on depoliticization is discussed in the next paragraph5. For example, against the background of partisan dealignment at the aggregate level (see section “(De)politicization as an aggregate process: Cohort effects” above), evidence has accumulated showing a high stability (and even reinforcement) of individual party identifications over the lifecycle (e.g., Shively, 1979; Alwin et al., 1991: chap. 5–7; Sears and Funk, 1999; Arzheimer and Schoen, 2005). Likewise, political interest remains remarkably stable as people age (e.g., Prior, 2010, 2019). This may occur for several reasons. For one thing, individuals' social environments and personal networks are assumed to exert normative pressure toward political engagement, at least under some circumstances (e.g., Huckfeldt, 1979; Huckfeldt and Sprague, 1995; Gimpel et al., 2003; Johnston and Pattie, 2006). As the range of personal networks increases over the adult years (e.g., family members, friends, work colleagues, neighbors, informal discussants in religious associations, etc.), so too should people's exposure to these normative sources6.

A second line of inquiry in the individual-level analysis of political engagement focuses on possible causes of depoliticization. Importantly, the life course perspective put forward in the analysis of politicization is also relevant for explaining depoliticization. For example, this perspective is helpful to clarify why some indicators of political engagement exhibit a decrease among elderly people (e.g., Schlozman et al., 2012: chap. 8). One obvious explanation is that declining physical and mental abilities (e.g., impaired health and well-being, cognitive deficiencies) lower the motivation and material capacity to engage in some forms of political activity (e.g., Burden et al., 2017; Mattila et al., 2018). Other accounts include a loss of social integration and support (e.g., Sears, 1981; Bhatti and Hansen, 2012), declining income and social status (e.g., Verba and Nie, 1972: chap. 9; Eaton et al., 2009), or increased susceptibility to attitude change and decreased intensity of attitudes such as party identification (e.g., Alwin and Krosnick, 1991, p. 185–188; Visser and Krosnick, 1998). One notable aspect of old age is that it tends to have little impact on forms of political engagement that are less demanding in terms of personal resources and involvement (e.g., voting turnout); in contrast, activities that require more sustained commitment are less frequently performed by both old and young adults (see Wattenberg, 2002: chap. 4; Dalton, 2020: chap. 4; Prosser et al., 2020). From there, it appears that variations in political engagement across different “life stages” (Sears, 1981; Eaton et al., 2009) are largely dependent on whether individuals have the opportunities for engaging in politics.

Of course, age is related to many other life circumstances (such as getting married or having children) which may impact political engagement but cannot be assessed in an Age-Period-Cohort (APC) framework. An approach analyzing change within individuals would be more appropriate to analyze effects of life transitions, life circumstances and influence between partners or family members. Within the APC framework designed to explain aggregate change in political engagement, we focus on age as a numerical variable broadly related to socializing processes and varying opportunities for political engagement. More specifically, we expect a non-linear relationship between age and politicization, which will be modeled by a quadratic age function (including age and age squared).

H3: Political engagement increases over the life course until retirement, after which it stabilizes, and then decreases with old age.

Sample, variables, and methods

Empirical data

We use data from the Swiss Household Panel (SHP), an annual panel survey based on a probability-based sample of the Swiss population living in private households. The survey started in 1999 and added refreshment samples in 2004, 2013, and 2020 (Tillmann et al., 2022). All household members as of 14 years old are invited to participate. Since the beginning, the SHP contains a series of variables on politics, which allow a longitudinal analysis of (de)politicization. In this study, we use all waves of data collection, from 1999 to 2020. However, some of the variables on political engagement were only measured in a subset of these waves (see below). The interviews take place between September and February. We restrict our sample to individuals aged 18 or older, but include both Swiss (91.8%) and foreigners (8.2%). The pooled sample includes 170,268 observations from 29,491 individuals. The number of interviews per wave varies between 15,027 (in 2020) and 4,865 (in 2003). While the SHP is conducted by telephone (CATI) as a main survey mode since its beginning, web has become more prominent in the most recent subsample, which started in 2020, with 53% responding by web. For the older samples, web interviews are available on request since 2010, but remain relatively rare; their share increased from 0.6% in 2010 to 7.9% in 2020. To control for mode effects, it is important to include survey mode in the analysis, since reported political engagement tends to be higher when collected by telephone compared to Web7.

Generally speaking, there are different types of non-response in the SHP. Not all households and individuals participate in the original sample (initial non-response), other individuals drop out in later waves (attrition) and some participants do not answer specific questions (item non-response). Regarding attrition, we found that individuals who are little engaged in politics and right-leaning individuals are more likely to drop out of the panel. Consequently, we are likely to overestimate growth in political engagement and underestimate decreasing engagement in univariate analysis (Voorpostel, 2010). To correct this bias, we include several control variables on socio-demographic characteristics (gender, educational level, linguistic region, nationality) and methodological aspects (survey mode, indication of first interview, number of participations in the panel). We conducted a series of sensitivity analysis using different samples to ensure that reported trends and patterns are robust.

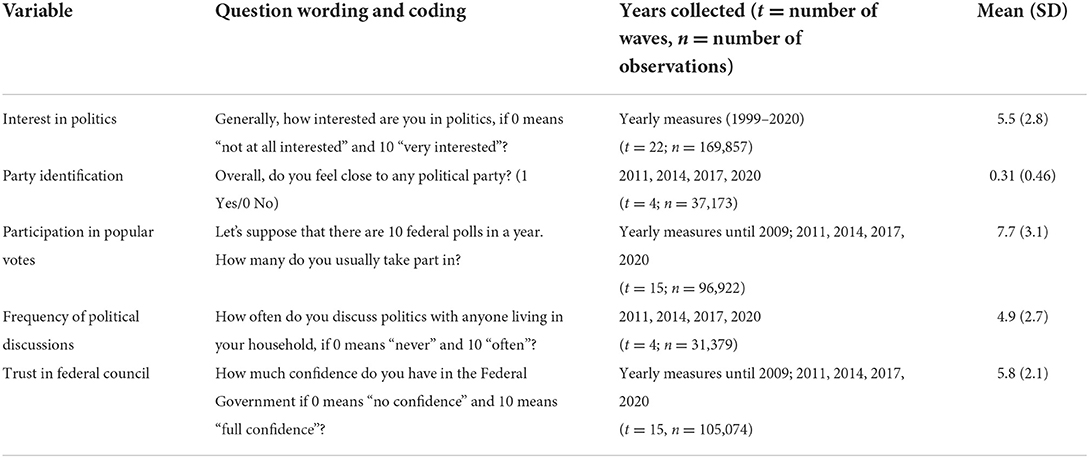

Dependent variables

The SHP contains several variables of political engagement, which have been collected over a long period and include several individual measures: (1) interest in politics; (2) party identification; (3) participation in popular votes; (4) frequency of political discussions; and (5) trust in the Federal council. Since 2010, most political variables are no longer collected on a yearly basis, but within a module on politics (in 2011, 2014, 2017, and 2020). The periodicity of data collection, scales and question wording are shown in Table 1. For the forthcoming analyses, however, all dependent variables were standardized to a 0–1 range.

Explaining aggregate change: APC analysis

In this article, we look at age, period and cohort (APC) effects as drivers of temporal changes in political engagement. This distinction is challenging, because the three effects are linearly related (Cohort = Period – Age) and constraints need to be imposed. Panel data, which follow the same individuals over time, facilitate the distinction of the three effects. APC models are not causal models, because none of these factors can be changed while keeping the others constant (Clogg, 1982; Fienberg and Mason, 1985). We do not go into the broad literature on estimating APC, which includes many approaches. Most recently, hierarchical modeling has become popular (e.g., Yang and Land, 2013; Smets and Neundorf, 2014; Grasso et al., 2019) for repeated cross-sectional data; however, this approach has also been criticized (e.g., by Fosse and Winship, 2019). The difficulties in disentangling APC effects are more fundamental than the choice of the appropriate statistical algorithm. A theoretical basis is central for the estimation and interpretation of APC effects, as it is the case with any problem of causal inference.

Here, we apply a rather traditional approach to assess APC effects, by including non-linear effects for age, period and cohorts. The panel structure helps to distinguish differences between constant variables (such as cohorts) and time-varying variables (such as age and periods), which is useful for this analysis. We use pooled OLS models to analyse all dependent variables, taking account of clustering within individual persons in the standard errors.

Age effects provide information on how political engagement varies across the life course. Based on our literature review and Hypothesis 3, we include a quadratic age function into the model.

Cohort effects arise because different generations are exposed to different socialization contexts. We distinguish cohorts typically used in social science, namely the Silent Generation (generation born before 1950), Baby Boomers (born 1950–1964), Generation X (1965–1979), Generation Y (or Millennials, 1980–1995) and Generation Z (born after 1995). It needs to be considered that each cohort is only followed over a part of the life cycle. The Silent Generation is observed from age 50, the Baby Boomers between age 36 and 70, Generation X between age 20 and 56, Generation Y between age 18 and 40 and Generation Z between age 18 and 258. This limitation is mostly relevant for the youngest and oldest cohorts, where the distinction of life-cycle and cohort effects is more difficult. For example, we do not have any information about life-cycle effects of the Silent Generation or about the student years and transition to paid work of Baby Boomers.

Finally, period effects capture changes that could affect all ages simultaneously. These effects are measured in three ways. First, we use simple year dummies, in order to ascertain year-to-year variations in political engagement without having to impose strong constraints (Model 1). Second, we test a linear effect of time (expressed in years) to examine the possibility that political engagement generally increases (or decreases) across all panel waves (Model 2). If such is the case, the simple linear coefficient should establish it more clearly than the whole set of year dummies. Finally, in Model 3, we test period effects with two dichotomous variables (crisis year and election year) corresponding more precisely to Hypotheses 2a and 2b:

• Crisis year: takes the value 1 for the following years: 2001 (9/11 terrorist attacks in the US, events in Switzerland such as mass shooting in a cantonal parliament, bankruptcy of the national airline Swissair), 2008 and 2009 (economic crisis), 2011 (Fukushima disaster), 2015 (migration crisis and terrorist attacks in France), 2018 (protests related to climate change)9, and 2020 (COVID-19 pandemic).

• Election year: takes the value 1 for 1999, 2003, 2007, 2011, 2015, and 2019.

It should be noted that Models 2 and 3 do not allow to estimate cohort effects accurately, as the linear time function and the two dummy variables (crisis and election years) measure period effects with less precision than the year dummies. Accordingly, Model 1 will be used for the interpretation of cohort and age effects.

As control variables we include gender, Swiss nationality, educational level, interview mode (CAWI vs. others), a dummy variable indicating whether an observation is the first one for a given respondent (to correct for attrition bias and panel conditioning effects), the linguistic region of the respondent (German-speaking and Italian-speaking, contrasted to French-speaking), the SHP sample in which a respondent was initially enrolled [refreshment samples II (2004), III (2013), and IV (2020) are contrasted with initial sample I (1999)], as well as the number of individual interviews completed relative to the maximal number of interviews possible for a given respondent (depending on year of first interview).

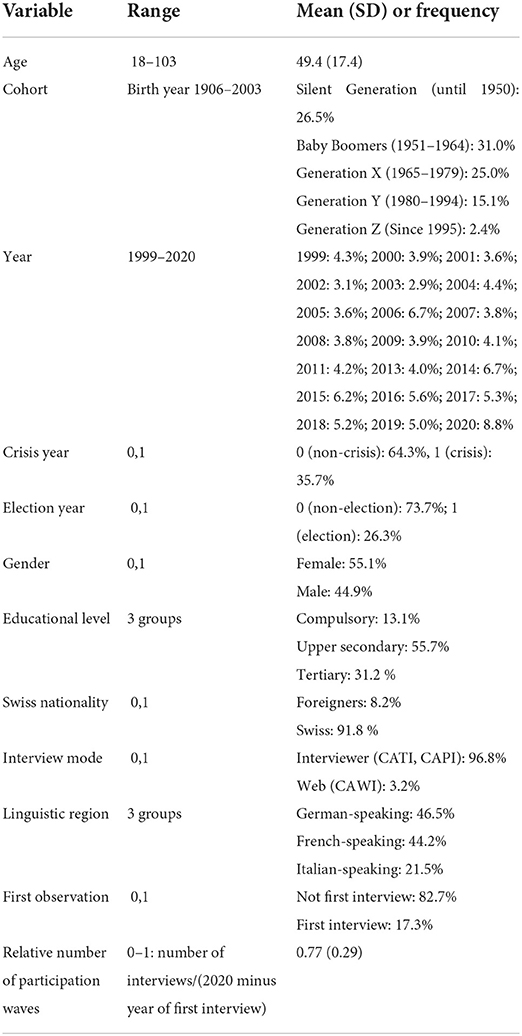

Descriptive statistics for all independent and control variables are shown in Table 2.

Results

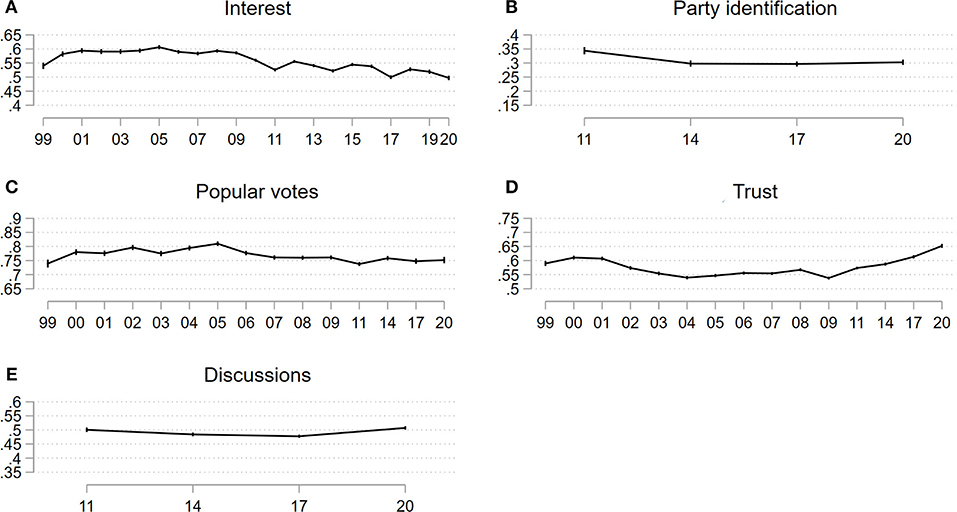

In this section, we describe how political interest, party identification, participation in popular votes, the frequency of political discussions and trust in the Federal Council have developed in Switzerland over the last 20 years. To assess how periods, cohorts, and age have affected general trends of (de)politicization, we estimate OLS regression models that include age, cohort, and period, as well as socio-demographic and methodological controls (see section “Explaining aggregate change: APC analysis”). Predicted values from these models enable us to tell a more nuanced story of political engagement in Switzerland than is possible with cross-sectional data. For illustration purposes, Figures 2–4 below show predicted values based on Model 1, which uses year dummies for the assessment of period effects. This ensures that the estimation of cohort and age effects is based on the most accurate (though not theoretically most relevant) way of measuring period effects. Models 2 and 3 are displayed in Table A1 in the Appendix.

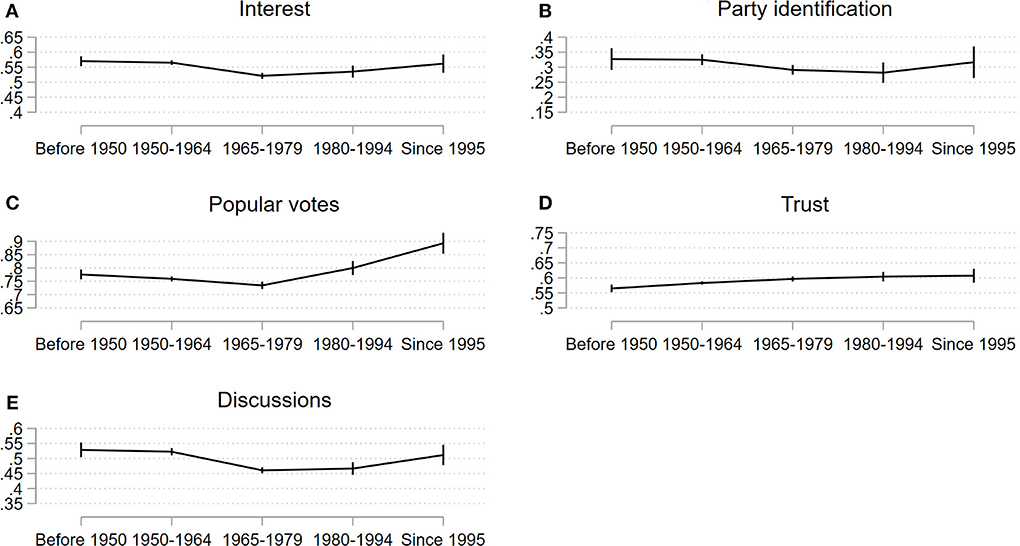

Figure 2. Political engagement as a function of Periods (SHP, 1999–2020). (A), Interest; (B), Party identification; (C), Popular votes; (D), Trust; (E), Discussions. With 95-percent confidence intervals.

Starting with period effects, Figure 2 shows all year-to-year variations in the five indicators of political engagement. Focusing on short-term changes, the figure does not reveal strong period effects related to specific crises. The only variation that stands out is the (admittedly rather small) drop in political interest in 2010 and 2011 following the 2008/2009 economic crisis (see Figure 2A). Yet, this is just the beginning of a steady decrease of political interest during the second decade of the 21st century (a long-term period effect that is also captured by the linear effect in Model 2). Interestingly, we simultaneously observe a small and steady increase for trust in the national government (Figure 2D). In contrast, similar to political interest, party identification (Figure 2B) and participation in popular votes (Figure 2C) tend to point to depoliticization. The case of political discussions (Figure 2E) is arguably less clear, as there is a (small) decreasing trend between 2011 and 2017, followed by an (equally small) increase into 202010. To complement these rather shaky interpretations of period effects, Model 2 (see Table A.1 Appendix) provides an estimate of the overall linear trend for each of the five indicators of political engagement. The coefficients are small but statistically reliable, suggesting that engagement has decreased across panel waves for most measures, with the exception of political trust (which has tended to increase overall) and political discussions (for which there is no linear effect at all). However, the incremental and long-lasting nature of these trends makes it difficult to interpret them as effects of specific crises.

For Hypotheses 2a and 2b, which specify that variations in political engagement are related to specific crises and to the electoral cycle, we look at the “crisis year” and “election year” coefficients in Model 3 (Table A.1 Appendix). The evidence is not supportive of the “troubled years” hypothesis (H2a). No effect of crises emerges for political interest and party identification. In the case of participation in popular votes, the effect is unexpectedly (and significantly) negative. This means that, in troubled times, people tend to underestimate their general participation in direct-democratic votes—or to provide less biased self-reports of participation11. Ironically, political trust is positively related to the occurrence of crises, although it may appear theoretically unwarranted to expect a systematic effect of crises on political trust (see H2a). The explanation probably lies in the fact that the Swiss government was not held responsible for the alleged crises selected in our analysis. Moreover, our results are in line with studies which report increases in political trust during the COVID-19 pandemic (Esaiasson et al., 2020; Bol et al., 2021). The only significant and expected effect of crisis years is found for political discussions. This effect is due to peaks in home discussions in 2011 (following the Fukushima disaster and the Swiss government's decision to phase out nuclear power by 2034) and in 2020 (most probably the result of the COVID-19 crisis, which strongly impacted everyone's daily life). However, these interpretations are speculative because of the limited number of waves available for measuring political discussions. To some extent, thus, our rejection of H2a confirms the lack of significant variation in political engagement observed for most single episodes of crisis (see Figure 2)12. On the same yearly basis, there seems to be little evidence for an effect of the electoral cycle (H2b). Model 3 confirms this impression. While party identification does seem to rise in election years, the reverse pattern obtains for political interest, participation in popular votes, and political trust. Thus, H2b is at best partially confirmed.

In conclusion, there is little evidence for period effects related to specific events on the political engagement of Swiss residents, and the general trends toward (de)politicization that we observe do not seem to be related to particular crisis periods. One reason for this rather low impact of periods on political engagement might be that Switzerland was less directly affected by the crises of the last two decades than other countries. The COVID-19 pandemic may be one exception, but so far, we have not found strong effects related to it.

Turning now to cohort effects, there seems to be relatively small differences between the engagement levels of the five generations (see Figure 3). Starting with H1c, we posited a U-shaped relationship between successive generations and the level of political interest and discussions. Figure 3A suggests that younger cohorts (Generations Y and Z) may be slightly less interested than Baby boomers and the Silent generation, but they do seem to have more interest in politics than Generation X, which appears to have the lowest level of all cohorts (see also Table A.1 Appendix). Patterns of results are similar for political discussions (see Figure 3E): members of Generations X and Y are the least likely to discuss politics within the family and members of the older generations are the most likely. Overall, then, H1c is supported.

Figure 3. Political engagement as a function of Cohorts (SHP, 1999–2020). (A), Interest; (B), Party identification; (C), Popular votes; (D), Trust; (E), Discussions. With 95-percent confidence intervals.

In contrast, H1a has to be rejected. For one thing, party identification exhibits no significant variation across generations (Figure 3B). As for participation in popular votes, it does decrease from the Silent generation to Generation X, but it then increases markedly and reaches its highest level among members of the youngest generation (Figure 3C). Finally, we find a small upwards trend for trust in the Federal Council, with younger generations being more trustful than older ones (Figure 3D). This is exactly the opposite of what H1b predicts, and this hypothesis must be clearly rejected too.

In sum, we find two patterns for cohort effects on political engagement. On the one hand, older generations tend to be more politicized than Generation X. On the other hand, we identified an upward trend in politicization for the younger Generations Y and Z. This could be a consequence of the multiple crises that occurred (and accumulated) during the “impressionable years” of socialization of these younger generations. Yet, we should take this interpretation with a grain of salt, as we only observe these two generations (and especially generation Z) when they were young. An exception to this general pattern is political trust where we observe a slight and steady increase across generations.

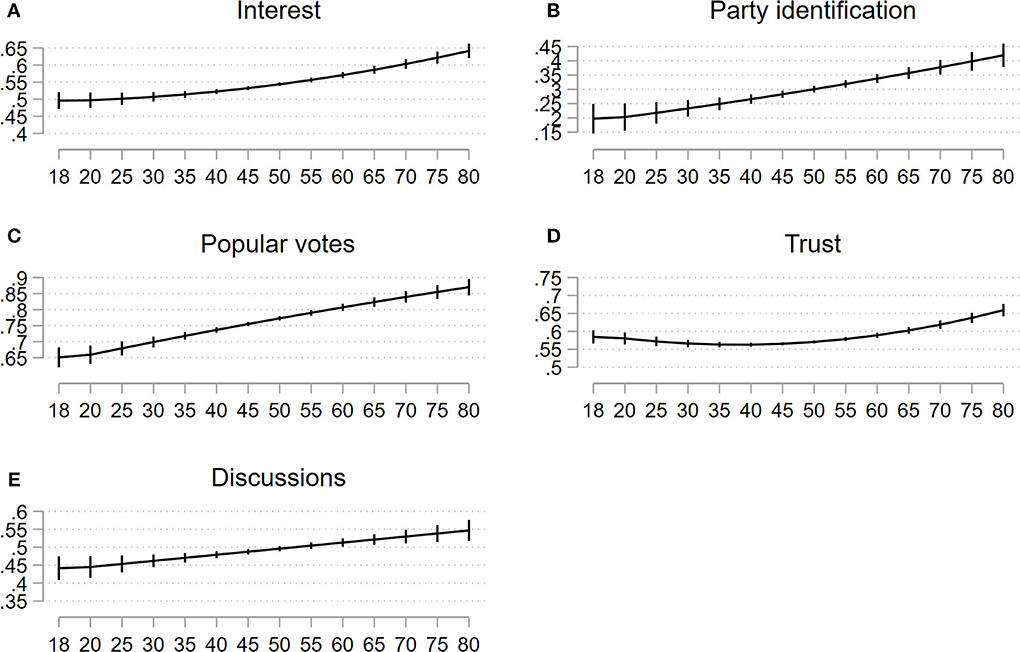

To complete our APC analysis, we finally deal with aging effects. When it comes to age, we come across a rather uniform pattern of effects. In fact, we find positive relationships across all five indicators (see Figure 4)13. However, there is no evidence that political engagement levels off after retirement and decreases with old age14. On the contrary, the quadratic component of age is either positive, suggesting an accelerating increase in political engagement as people grow older (political interest, trust in government), or very small and non-significant, suggesting a monotonically increasing trend in engagement (party identification, participation in popular votes, discussions).

Figure 4. Political engagement as a function of Age (SHP, 1999–2020). (A), Interest; (B), Party identification; (C), Popular votes; (D), Trust; (E), Discussions. With 95-percent confidence intervals.

Hypothesis 3 is thus only partially confirmed. There is an increase in political engagement throughout the adult years, but there is no decrease among the elderly. Trust in Federal Council, however, is slightly different from this general pattern, as the overall effect of age comes close to a U-shaped function, with people at the age of about 40 being the least trustful (see Figure 4D).

Regarding control variables in the model, we find different relationships for trust compared to the other indicators of political engagement. Political interest, party identification, participation in popular votes and the frequency of political discussions are higher for men compared to women, for Swiss nationals compared to foreigners, and for people with middle to high education compared to people with lower educational levels15. In line with other indicators, political trust increases with educational levels, but there are no significant gender differences, and Swiss nationals show lower political trust than foreign citizens. Finally, interest in politics, trust, and political discussions are more widespread in the German-speaking region. In contrast, residents from the French and Italian-speaking regions are more politically engaged in terms of party identification; and there is no significant difference between linguistic areas for participation in popular votes.

Conclusion

In this contribution, we analyzed the evolution of political engagement in Switzerland from 1999 to 2020, using data from the Swiss Household-Panel. From our Age-Period-Cohort (APC) analysis, we could draw three main conclusions. First, as regards period effects, we could establish that “troubled times” have little effect on political engagement overall, as short-term variations never exceed a few percentage points. However, in the short run, crises might boost political discussions and trust in government, and they may have a cumulative effect on trust, which regularly increased in the last decade. In contrast, we observed a small and steady decrease in political interest, party identification, and participation in popular votes. Second, our examination of cohort effects provided evidence of a U-shaped association between generations and political engagement. Members of Generations X and Y (born between 1965 and 1994) tend to have the lowest engagement level, compared to older or younger generations. However, this pattern does not hold for political trust, where we observed a small but steady increase across generations. Finally, age effects are relatively straightforward. In general, our models revealed a monotonic positive relationship: the older one gets, the more politicized one becomes. Again, trust in government somewhat deviates from other forms of political engagement, as it first decreases in the younger age groups and then increases from the age of 40 onwards.

One way of summarizing the results of our analysis is to take politicization as a baseline pattern and to identify the most likely deviations from this baseline. Seen in this light, depoliticization is substantiated (1) in a long-term decline in traditional forms of political engagement, namely party identification, and direct-democratic participation, but also in political interest; (2) in a generational shift from older (Silent and Boomers) to middle-aged cohorts (X and Y), though not for political trust; and (3) in a comparison between positions in the lifecycle, whereby younger adults are less politicized than their older counterparts. Importantly, citizens from the youngest cohort (Generation Z) have the lowest level of political engagement due to their position in the lifecycle. But controlling for nominal age (i.e., lifecycle position), members of Generation Z are not less politically engaged than members of the two preceding generations. Accordingly, they have a high potential for further politicization. Moreover, we were not able to analyze unconventional participation (demonstrations, boycotts, etc.), as longitudinal data on these forms of political engagement are not yet available. As younger citizens are especially likely to engage in politics through non-conventional activities, we may underestimate their political engagement and we may fail to estimate their real contribution to public support for an inclusive conception of democracy.

Our findings provide sobering lessons with respect to the general question asked in this Research Topic. In particular, the future of democracy hinges on how citizens' political engagement is likely to develop in coming years. In this regard, our retrospective account of Swiss citizens' political engagement over the past 20 years (1999–2020) is a useful tool for looking into the future. It suggests that the many challenges and crises which democratic societies have faced in recent years have resulted neither in a general depoliticization nor in a general politicization of the citizenry. To be sure, crises and populist backlash may increase political engagement under some circumstances. More crucially, however, our analysis indicates that support for democracy is probably not undermined by generational replacement and by the political disaffection of younger generations.

Overall, the results of our analysis may be disappointing to scholars who would have expected more straightforward politicizing (or depoliticizing) effects of large-scale events. These limited effects may have to do with peculiarities of the Swiss context. In general, Switzerland was less affected by the crises of the last decades than other countries. This could be due to several factors, including important political measures to buffer financial losses, strong federalism (with significant power at the local level), direct democratic institutions, and the country's (relative) political and monetary sovereignty arising from non-membership in the European Union and the Eurozone. Future research should apply APC analysis to investigate the causes of political engagement in a more comparative way, focusing on different countries, in order to test the generalizability of our findings and to clarify the role played by contextual, time-invariant factors at the country or local level.

Alternatively, this lack of clear-cut results may be due, to some extent, to the nature of our panel survey data. However, the most relevant socio-demographic and methodological controls were applied to minimize measurement bias. Likewise, our rather crude operationalization of period effects may be questioned; but taking into account year-to-year variation proved little more discriminant for predicting (de)politicization than more theoretically driven ways of defining “critical periods” (i.e., crisis and election years). Therefore, we are confident that the key trends emerging from our analysis are based on solid grounds. Moreover, the mixed results of previous research suggest that the consequences of crises for political engagement are context-specific, and that they vary between individuals and between forms of political engagement.

Data availability statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found at: https://www.swissubase.ch/fr/catalogue/studies/6097/18153/datasets/932/2297/overview.

Author contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Funding

This study has been carried out using the data collected by the Swiss Household Panel (SHP), which is based at the Swiss Centre of Expertise in the Social Sciences FORS. The project is financed by the Swiss National Science Foundation. Open access funding was provided by the University of Lausanne.

Acknowledgments

We thank Chiara Vargiu and other participants of the Annual Congress of the Swiss Political Science Association 2022, as well as reviewers, for their helpful comments.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2022.981919/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^For example, it has been shown that participation can foster trust and interest, while in some situations trust and interest can also fuel participation (Uslaner, 2002: chap. 5; Quintelier and Hooghe, 2012; Gabriel, 2017).

2. ^In various research fields, such shattering, sudden, and unanticipated events originating from outside the domestic system have been conceived as “external/exogeneous shocks” (e.g., Rodrik, 1999; Ahlquist et al., 2020).

3. ^Periods of enhanced trust in government broadly overlap with “rally ‘round the flag effects” observed in variations of the popularity of the executive (e.g., Mueller, 1970; Chatagnier, 2012)—whereby trust and popularity are probably mutually reinforcing. However, a decrease in trust is also possible, such as when the executive head is held personally responsible for the occurrence of a violent attack (Gates and Justesen, 2020).

4. ^Likewise, there is scant evidence for the “impressionable years” hypothesis that events have more influence on young people because their attitudes are more malleable (i.e., a type of cohort effect). Rather, the overall picture is one of a great stability of political interest over time. However, it may be stressed that Prior's analysis focuses on only one indicator of political engagement and does not take into account some of the recent “crises” that unsettled European citizens (e.g., 2015 migration crises and terrorist attacks, COVID-19 pandemic). In addition, large-scale events such as the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 and German reunification in 1990 did produce a sizeable (though temporary) increase in political interest in the German population (Prior, 2019: chap. 5–6).

5. ^Hence, Sapiro (1994, p. 201) has proposed that “the term ‘individual political development' might replace ‘political socialization' as the broader concept” (for a similar view, see Plutzer, 2002).

6. ^Not surprisingly, the politicization effect of spouses and partners may be particularly powerful and lasting (e.g., Kenny, 1993; Nickerson, 2008). Marriage produces a process of “mutual socialization,” whereby husbands and wives tend to “look more alike as the marriage ages” (Stoker and Jennings, 2005, p. 70).

7. ^These mode effects are most likely due to social desirability with the presence of an interviewer. However, selection effects are also possible, as respondents self-select into web interviews.

8. ^We tested also alternative specifications. When a higher number of cohorts are distinguished, the separation of age and cohort effects at the beginning and at the end of the age span becomes more complex and results become implausible.

9. ^Data collection for each wave takes place between September and February, but over 90% of interviews are carried out between September and November. The largest protests related to climate change took place at the end of 2018 and beginning of 2019, and, therefore, during the data collection 2018.

10. ^Unfortunately, we do not have information for party identification and the frequency of political discussions before the questions were introduced in 2011.

11. ^We are inclined to dismiss the interpretation that the negative coefficient reflects actual decrease in recent direct-democratic participation; in fact, official participation rates (averaged by year) are 1.5 percentage point higher in crisis years than in other years. Instead, the fact that respondents may usually overestimate their participation in direct-democratic votes is suggested by the suspiciously high participation rate indicated in Table 1 (M = 7.7). Taken at face value, this statistic would mean that Swiss residents take part in almost eight out of 10 popular votes. Social desirability and selection effects into the survey loom large in such overreporting of voting (e.g., Karp and Brockington, 2005; Sciarini and Goldberg, 2016).

12. ^The years 2001 (9/11 terrorist attacks) and 2015 (migration crisis and terrorist attacks in France) are examples in point.

13. ^Age coefficients for party identification and political discussions are not significant in Table A.1 Appendix. However, if we include age as a linear term (rather than as a quadratic function), coefficients are strongly significant and positive in all models.

14. ^Selection could also play a role in this context. By definition, only individuals living in their household who are capable and willing to respond to the survey are observed, thus excluding people in old-age homes.

15. ^There are two exceptions to these general findings. First, there is no gender difference for political discussions. Second, as foreigners do not have the right to vote at the federal level, the effect of Swiss nationality was not estimated in the model predicting participation in popular votes.

References

Abramowitz, A. I., and Saunders, K. L. (2008). Is polarization a myth? J. Polit. 70, 542–555. doi: 10.1017/S0022381608080493

Abramowitz, A. I., and Webster, S. W. (2018). Negative partisanship: why americans dislike parties but behave like rabid partisans. Adv. Polit. Psychol. 39, 119–135. doi: 10.1111/pops.12479

Abramson, P. R. (1976). Generational change and the decline of party identification in America: 1952-1974. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 70, 469–478. doi: 10.2307/1959651

Ahlquist, J., Copelovitch, M., and Walter, S. (2020). The political consequences of external economic shocks: evidence from Poland. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 64, 904–920. doi: 10.1111/ajps.12503

Albright, J. J. (2009). Does political knowledge erode party attachments? A review of the cognitive mobilization thesis. Elect. Stud. 28, 248–260. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2009.01.001

Aldrich, J. H., and Freeze, M. (2011). “Political participation, polarization, and public opinion: activism and the merging of partisan and ideological polarization,” in Facing the Challenge of Democracy: Explorations in the Analysis of Public Opinion and Political Participation, eds P. M. Sniderman, and B. Highton (Princeton: Princeton University Press), 185–206. doi: 10.1515/9781400840304-009

Alford, R. R., and Friedland, R. (1975). Political participation and public policy. Ann. Rev. Sociol. 1, 429–479. doi: 10.1146/annurev.so.01.080175.002241

Alwin, D. F., Cohen, R. L., and Newcomb, T. M. (1991). Political Attitudes over the Life Span: The Bennington Women after Fifty Years. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press.

Alwin, D. F., and Krosnick, J. A. (1991). Aging, cohorts, and the stability of sociopolitical orientations over the life span. Am. J. Sociol. 97, 169–195. doi: 10.1086/229744

Ansolabehere, S., and Iyengar, S. (1995). Going Negative. How Political Advertisements Shrink and Polarize the Electorate. New York, NY: The Free Press.

Armingeon, K., and Ceka, B. (2014). The loss of trust in the European Union during the great recession since 2007: the role of heuristics from the national political system. Eur. Union Polit. 15, 82–107. doi: 10.1177/1465116513495595

Armingeon, K., and Guthmann, K. (2014). Democracy in crisis? The declining support for national democracy in European countries, 2007–2011. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 53, 423–442. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.12046

Armingeon, K., and Schädel, L. (2015). Social inequality in political participation: the dark sides of individualisation. West Eur. Polit. 38, 1–27. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2014.929341

Arvanitidis, P., Economou, A., and Kollias, C. (2016). Terrorism's effects on social capital in European countries. Public Choice 169, 231–250. doi: 10.1007/s11127-016-0370-3

Arzheimer, K. (2006). ‘Dead men walking?' party identification in Germany, 1977–2002. Elect. Stud. 25, 791–807. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2006.01.004

Arzheimer, K., and Schoen, H. (2005). Erste schritte auf kaum erschlossenem terrain. Zur stabilität der parteiidentifikation in Deutschland. Polit. Vierteljahresschr. 46, 629–654. doi: 10.1007/s11615-005-0305-y

Banducci, S., and Stevens, D. (2015). Surveys in context: how timing in the electoral cycle influences response propensity and satisficing. Public Opin. Q. 79, 214–243. doi: 10.1093/poq/nfv007

Bankert, A. (2021). Negative and positive partisanship in the 2016 U.S. presidential elections. Polit. Behav. 43, 1467–1485. doi: 10.1007/s11109-020-09599-1

Barnes, S. H., and Kaase, M. eds (1979). Political Action. Mass Participation in Five Western Democracies. Beverly Hills: Sage.

Berglund, F., Holmberg, S., Schmitt, H., and Thomassen, J. (2005). “Party identification and party choice,” in The European Voter: A Comparative Study of Modern Democracies, ed J. Thomassen (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 106–124. doi: 10.1093/0199273219.003.0005

Bermeo, N., and Bartels, L. M. eds (2014). Mass Politics in Tough Times: Opinions, Votes, and Protest in the Great Recession. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199357505.003.0001

Bhatti, Y., and Hansen, K. M. (2012). Retiring from voting: turnout among senior voters. J. Elect. Public Opin. Parties 22, 479–500. doi: 10.1080/17457289.2012.720577

Bisbee, J., and Honig, D. (2022). Flight to safety: COVID-induced changes in the intensity of status quo preference and voting behavior. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 116, 70–86. doi: 10.1017/S0003055421000691