- 1Department of Politics, Languages and International Studies, University of Bath, Bath, United Kingdom

- 2Instituto de Políticas y Bienes Públicos (CSIC), Institute of Public Goods and Policies, Spanish National Research Council, Madrid, Spain

- 3Department of Political Science, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden

- 4Department of Political Science, University of Salzburg, Salzburg, Austria

- 5Department of Social and Political Sciences, Philosophy, and Anthropology, University of Exeter, Exeter, United Kingdom

Introduction: The gender gap in populist radical right voting—with women being less likely to support populist radical right parties than men—is well-established. Much less is known about the interplay between gender, masculinity and populist radical right voting. This study investigates the extent to which masculinity affects women and men's likelihood of supporting populist radical right parties. Focusing on sexism as a link between masculinity and populist radical right support, we put forward two mechanisms that operate at once: a mediating effect of sexism (sexism explains the association between masculinity and populist radical right voting) and a moderating effect of sexism (the impact of masculinity is stronger among citizens scoring high on sexism compared with citizens with low levels of sexist attitudes).

Methods: We draw on an original dataset collected in Spain at the end of 2020 to investigate support for the Spanish populist radical right party VOX.

Results: We find support for hypothesized mechanisms, mediation and moderation, chiefly among men. First, sexism explains about half of the link between masculinity and populist radical right support for this group, confirming the hypothesized mediation effect. Second, masculinity has a significantly stronger impact on the likelihood of supporting VOX among men scoring high on sexism, which in turn substantiates the presence of a moderation effect.

Discussion: Existing research so far has examined the empirical connections between how individuals perceive their levels of masculinity, sexism, and PRR voting separately. Our study offers a first step in unpacking the relationship between masculinity and PRR support by focusing specifically on how sexism relates to both these variables.

Introduction

It has become a well-documented finding that women are less likely to support populist radical right (PRR) parties although interesting differences between countries have been mapped (e.g., Givens, 2004; Gidengil et al., 2005; Fontana et al., 2006; Rippeyoung, 2007; Immerzeel et al., 2015; Spierings and Zaslove, 2015; Coffé, 2018; Harteveld and Ivarsflaten, 2018; Weeks et al., 2023). This literature suffers from two compounding challenges. First, the bulk of scholarly contributions draw on a binary measure of gender: comparing women with men. Such binary measures of gender ignore the fluid, dynamic and individual ways in which gender identity can be expressed. Second, studies investigating the gender gap in PRR support mostly focus on women's underrepresentation among the PRR electorate, explaining why women are less inclined than men to support these parties. Much less attention has been paid to the reverse side of the coin, namely men's overrepresentation among PRR voters and the causal mechanisms at play, which we hypothesize involves an interplay of hypermasculinity with sexism. This paper seeks to overcome these two intertwined challenges.

First, binary measures of gender carry the implicit and unrealistic assumption of group homogeneity. Recent research in both gender studies and political behavior highlight the need to break up these overly general binary measures and suggest to also include gender identity traits that reveal much more interesting and fine-grained differences (Bittner and Goodyear-Grant, 2017; Alexander et al., 2021a). This paper builds on advances made in recent literature by investigating to what extent and how masculinity—rather than conventional binary measures—impacts support for PRR parties. This approach allows us to provide novel, more nuanced insights into the interplay between gender and PRR voting.

Second, an emerging handful of studies uncovered an association between masculinity and support for PRR parties, showing that people subjectively ascribing to masculine characteristics are more likely to support PRR parties (e.g., Coffé, 2019; Gidengil and Stolle, 2021; Ralph-Morrow, 2022). Explanations for this relationship invoke, for example, the masculine character of PRR parties and their discourse, and a reaction to perceived threats to traditional masculinity. Little research has been in a position to offer a detailed empirical test explaining why masculinity relates to support for PRR parties. To fill this gap, we will not also examine the link between masculinity and PRR support, but also investigate why masculinity increases the likelihood of supporting PRR parties, zeroing on the role played by sexism between identities and vote choice. Sexism penalizes women who break with gendered traditional norms and understands men and women's relationship as competitive and a zero-sum game, whereby if women gain power, it is at men's expense. As such attitudes are more common among those reporting masculine traits—men in particular—and given the rhetoric against “gender ideology” deployed by many PRR parties (Cabezas, 2022), we expect sexist attitudes to operate between masculinity and support for PRR parties. We expect to see two mechanisms: a mediation effect (sexism explains at least part of the association between masculinity and support for VOX) and a moderation effect (sexism strengthens the relationship between masculinity and support for VOX).

In sum, the two main research questions motivating our study are: (1) to what extent does masculinity affect women and men's likelihood of supporting PRR parties? And, (2) to what extent is this link related to sexism? Given the visible backlashes against “gender ideology”, partly driven by the discourse of PRR parties and their growing electoral success in many countries around the globe (Cabezas, 2022), we are facing a critical moment to capture the interplay between gender, gender identity, sexist attitudes and support for PRR parties. To answer our research questions, we draw on an original online survey collected in December 2020 among a sample of Spanish citizens that resembles the Spanish voting age population (Fraile, 2023). Support for the PRR is measured by declared probabilities of voting for VOX. While the extent to which VOX is a populist party is a matter of ongoing discussion (e.g., Ferreira, 2019), the party shares many characteristics typical of the contemporary European PRR party family and has been labeled as such by researchers (e.g., Gould, 2019; Alonso and Espinosa-Fajardo, 2021; Rama et al., 2021). VOX thus offers a suitable and likely generalizable testing ground for theories looking into the electorates and success of populist radical right parties.

Our findings show that masculinity increases the likelihood of supporting VOX, yet this mechanism only holds among men, who also tend to score higher on masculinity than women. Our analyses further suggest that the association between masculinity and vote choice can be explained by sexism through two different paths: mediating and moderating. First, sexism explains about half of the link between masculinity and PRR support among men, revealing a significant mediation effect. Second, masculinity has a significantly stronger impact on the likelihood of supporting the PRR among more sexist men, also confirming the presence of a moderation effect. Our findings have important implications to unpack the complex empirical connection between gender, gender traits and the success of PRR parties.

Gender, masculinity and populist radical right support

There is a rising consensus among scholars that PRR parties have a distinctive gender specific profile: men are overrepresented among the PRR electorate (Givens, 2004; Gidengil et al., 2005; Fontana et al., 2006; Rippeyoung, 2007; Spierings and Zaslove, 2015; Coffé, 2018; Harteveld and Ivarsflaten, 2018).1 A more limited amount of scholarship has recently moved beyond the binary measure of gender and investigated the connection between femininity, masculinity and PRR voting (e.g., Coffé, 2019; Gidengil and Stolle, 2021; Ralph-Morrow, 2022). Pleck (1975, p. 164) defines masculinity and femininity measures as indications of “the extent to which the individual shows gender-appropriate traits, attitudes, and interests”. Masculinity is generally described as “adaptive-instrumental” and “assertive-dominant”, while femininity is more “integrative-expressive” and depicts “nurtureness-interpersonal warmth” (Bem, 1981; Williams and Best, 1982). While most would agree on these descriptions of masculinity and femininity in contemporary, Western societies, they are socially constructed and time and culture dependent (Connell, 2005). Moreover, while masculinity and femininity are often labeled in opposition to one another, with feminine being “not masculine” and masculine being “not feminine” (Foushee et al., 1979), they can be better understood as multidimensional concepts that vary independently (Bem, 1974).

While femininity has been found to have little effect on the likelihood to support PRR parties, masculinity is associated with higher support for these parties (e.g., Coffé, 2019; Gidengil and Stolle, 2021). Those scoring high on masculinity tend to be more likely to support PRR parties compared with those scoring low on masculinity. Smirnova (2018, p. 11) even conjectured that “associating with and voting for Trump thus becomes coded as an act of masculinity—not voting for him reflects one's lack of masculinity or brotherhood”. The link between masculinity and PRR voting has been attributed to the masculine character and discourse of PRR parties and their leaders. Carian and Sobotka (2018), highlight how Trump embodied an exaggerated form of masculinity that appeals to hypermasculine white men. Similarly, Daddow and Hertner's (2021) framework of toxic masculinity in political parties reveals that the policy positions, discourses and practices of UKIP and the AfD are toxically masculine, perhaps even specifically geared to be attractive to masculine voters. Furthermore, and particularly relevant for our study, Cabezas (2022) has shown VOX's use of masculinist frames, frames based on masculine threat and frames that construct feminism as the nation's enemy and harmful to men through a comprehensive analysis of VOX's communication strategies in electoral campaigns in Spain.

Scholars have also related the “masculine threat”— the fear among some men that they will lose their dominant position in society—to support for PRR parties. Willer et al. (2013), for example, put to the test “the masculine overcompensation thesis” which asserts that men react to masculinity threats with extreme demonstrations of masculinity in order to recover traditional masculine status, both in their own and others' eyes. While Willer et al. (2013) do not directly connect it to PRR support, they show an association between masculinity threats and support for war, homophobic attitudes, a desire to advance in dominance hierarchies, and a belief in male superiority.

PRR parties' narrative claim that all manner of “others” are replacing men in power and focused on masculinity. Daddow and Hertner (2021) illustrate this with the example of AfD's leader of the state Thuringia, Björn Höcke, who said at a party rally in November 2015: “We need to rediscover our masculinity. Because only if we rediscover our masculinity do we become manful. And only if we become manful, do we become fortified, and we need to become fortified, dear friends”. Given PRR parties' tendency to catalyze (men) majority anxieties (Gökariksel et al., 2019), we may expect masculine threats to relate to PRR support. Carian and Sobotka (2018) operationalized masculinity as a threat to men's employment and confirmed that it indirectly influenced Trump support. Gidengil and Stolle (2021) highlight the notion of threat as an explanation for the association between masculinity and support for Trump, though do not provide an empirical test of the explanation, but convincingly substantiate an empirical link between masculinity and Trump support. In addition, Cabezas' (2022) study of VOX offers examples of instances where the party advocates for a masculinist reinterpretation of the law on gender violence or funding of feminist organizations as discriminatory of men. As such, the party offers an attractive discourse for those scoring high on masculinity.

Based on the limited available literature and theories on masculinity and PRR parties, our first hypothesis reads:

H1: Masculinity will increase the likelihood of supporting populist radical right parties.

While both women and men can score high on masculinity, biological sex and masculinity characteristics are intrinsically related. As a result of gender socialization forces, men generally score higher on masculinity than women (Coffé, 2019; Alexander et al., 2021b). Some literature has suggested that it is particularly masculine men who support the PRR, assuming a reinforcing effect between masculinity and being a man. The concept of “hypermasculine men” refers to men who are not just masculine and not just male (Mosher and Tomkins, 1988, p. 64). Hypermasculine men exhibit an exaggerated form of masculinity, engage in stereotypical masculine behavior, and see themselves as possessing a high level of stereotypical masculine characteristics (Gidengil and Stolle, 2021, p. 1819). They also typically fear the feminization of society and are most likely to be susceptible to masculine threats. Studying the Dutch Freedom Party, Coffé (2019) did not find a stronger effect of masculinity among men compared with women. By contrast, Gidengil and Stolle (2021) confirmed a tendency of hypermasculine men to be especially attracted to Trump.

Referring to the theory of “precarious manhood”, DiMuccio and Knowles (2021) conclude that men who are anxious about their levels of masculinity—that is, men high in precarious manhood—attempt to affirm their status as “real men” and are more likely to support aggressive political policies and Donald Trump, and more generally embrace policies and politicians that signal strength and toughness.

In light of the literature on hypermasculine men and their support for PPR parties, the hypothesis related to the interaction between gender and masculinity, and PRR voting reads as follows:

H2: Masculinity will be more likely to increase men's likelihood of supporting populist radical right parties than women's.

Sexism, masculinity and populist radical right support

Several recent studies document the existence of an empirical connection between how individuals perceive their levels of masculinity and PRR voting (Coffé, 2019; Gidengil and Stolle, 2021; Ralph-Morrow, 2022). Yet, little scholarship has been able to explain this link beyond explicit party messaging. While masculine threat has been evoked as a factor, we do not know exactly by which explanatory mechanisms this might occur. Our study offers a first step in unpacking the relationship between masculinity and PRR support by focusing specifically on how sexism relates to both these variables. Defined as seeking “to justify male power, traditional gender roles, and men's exploitation of women as sexual objects through derogatory characterizations of women” (Glick and Fiske, 1997, p. 121), (hostile) sexism is targeted at women who break with gendered traditional norms. Sexism casts men and women's relationship as competitive and a zero-sum game, whereby if women gain power, it is at men's expense.

While masculinity and sexism are linked, scholarship has treated these concepts as analytically distinct as they have different targets (Glick et al., 2015; Barreto and Doyle, 2022): Masculinity pertains to how people perceive themselves, their identity. Sexism, on the other hand, is a negative evaluation aimed at others, in the case at hand, women as a group. We anticipate sexism to affect the link between masculinity and PRR support in two ways: through mediation (sexism explains the link between masculinity and PRR voting) and through moderation (the impact of masculinity is stronger among more sexist citizens compared with less hostile sexist citizens).

Mediation effect

Recent scholarship has uncovered an empirical connection between different forms of gender traditionalism and support for the PRR, even after controlling for rival explanations. Ratliff et al. (2019), for instance, suggest that those with hostile sexist attitudes are more likely to vote for PRR candidates, like Trump. The U.S. based literature looking at the role of hostile sexism and vote choice for Trump is, however, heavily shaped by the presence of a woman candidate who was the direct target of a backlash against women who seek power, which is one of the hallmarks of hostile sexism (Schaffner et al., 2018; Valentino et al., 2018; Cassese and Holman, 2019; Winter, 2022). Outside the US context, the literature draws on party rhetoric rather than candidate traits. Off (2023), for example, finds that the salience of liberalizing gender values may trigger a backlash that fuels PRR voting in Sweden.

To explain the link between masculinity and PRR support, scholars have referred to the populist voices contesting the equal participation of men and women in society under the auspices of a “war on gender ideology” (Graff, 2014; Cabezas, 2022). The anti-feminist rhetoric of PRR parties gives voice to the societal changes to the role of women that threaten the traditional male or masculine order. Cabezas' (2022) comprehensive analysis of VOX's communication strategies in electoral campaigns shows that in its efforts to mobilize voters, the party routinely deploys frames activating threats to masculinity threat as well as frames depicting feminism as the nation's enemy and harmful to men: a clear link between masculinity and sexist attitudes in attempts to mobilize voters. In addition to party rhetoric, an explanation for the link between masculinity and PRR support may be attitudinal: individuals displaying a strong attachment to masculinity traits are attracted by PRR parties because they see the world in sexist terms and hold sexist attitudes. Maass et al. (2003) revealed that men subject to threat inductions display more hostility toward women. Burkley et al. (2016, p. 120) have also shown that conformity to masculine norms is associated with hostile sexism among men. They find that men whose self-worth is affected by threat to their masculinity correlates with hostile sexist attitudes.

Those with masculine identities feel threatened by the erosion of traditional roles. One possible response to this is, as Burkley et al. (2016) suggest, an increase in sexist attitudes. In turn, sexist attitudes increase support for PRR parties. Although Burkley et al. (2016) focus on hegemonic masculinity (acceptance of masculine dominance in society), Vescio and Schermerhorn (2021) show that sexist attitudes, when combined with self-expressed masculinity, increased support for Trump. Gidengil and Stolle (2021) suggest that the more (white) men identify themselves as masculine, the more susceptible they are to masculine threat, which—in its turn—increases the likelihood of supporting Trump. While they do not directly test sexism as a mechanism behind the link between masculinity and support for Trump, they do show that masculinity relates to sexism, which they consider as an indicator of feelings of masculinity threat.

In sum, considering the PRR parties' discourse against “gender ideology,” and the links found in previous research between masculinity and PRR voting as well as masculinity and sexism, we can formulate the following hypotheses related to the expected mediation effect:

H3: The link between masculinity and supporting populist radical right parties can be (at least partially) explained by sexism.

H3a: The mediating effect of sexism on the link between masculinity and support populist radical right parties (H3) will hold particularly among men.

Moderation effect

In addition to a mediation effect, we also explore whether sexism moderates the relationship between masculinity and PRR support. The idea here is that besides sexism explaining the process through which masculinity is related to supporting a PRR party (as a mediator), sexism may also affect the strength of the association between masculinity and supporting the PRR. In other words, besides sexism working as the belief system through which higher masculinity leads to voting for the PRR, it is also plausible that sexism affects the extent to which higher masculinity leads to voting for VOX. Whereas, Gidengil and Stolle (2021) might suggest that sexism is a result of threats to masculinity where masculinity increases sexism, it is also possible that those scoring higher on sexism are more likely to have their masculinity mobilized by the rhetoric of PRR parties. The intersection of sexism coupled with threats to masculinity increase the support of PRR parties. Put more plainly, individuals' level of sexism moderates the relationship between their level of masculinity and PRR vote choice. Our hypotheses on the expected moderation effect thus read:

H4: The link between masculinity and populist radical right voting will be stronger among citizens scoring high on sexism compared with citizens scoring lower on sexism.

H4a: The moderating effect of sexism on the link between masculinity and support for populist radical right parties (H4) will hold particularly among men.

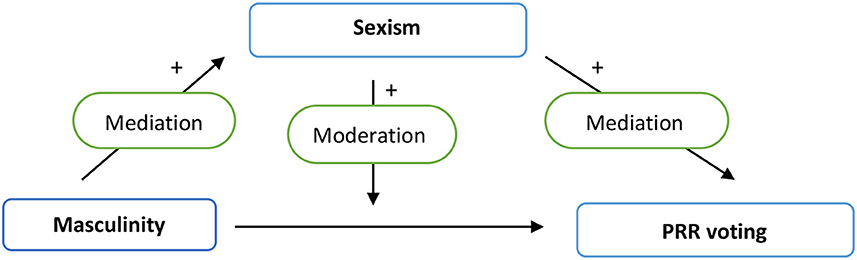

Figure 1 illustrates the mediating (H3 and H3a) and moderating (H4 and H4a) effects of sexism on the link between masculinity and PRR voting. As Figure 1 suggests, a mediating effect implies that those who feel very attached to a masculine identity are more inclined to support PRR parties because their sexist attitudes connect them to the discourse, demands and promises of PRR parties and leaders. By contrast, a moderation effect implies that it is only those scoring high on masculinity and who are also heartily sexists who are more likely to support PRR parties.

Figure 1. Illustration of mediating and moderating effect of sexism on the link between masculinity and populist radical right voting.

Case, data, and measurements

We test our hypotheses drawing on the case of Spain. Because of its recent transition to democracy relative to other Western European democracies, Spain has long been considered an exceptional case where PRR parties did not manage to achieve significant institutional foothold. Yet this exceptionalism is on the wane with the growing electoral success of the populist radical right party VOX. VOX entered a (regional) parliament for the first time after the December 2018 Andalusian elections of December 2018. This regional election took place after the massive protest event on the International Women's Day of the 8th of March which culminated in the largest general women's strike in recent history in Spain (Campillo, 2019; Jimenez et al., 2022). Since then, VOX's institutional representation has increased both at regional and national levels. The party obtained an unprecedented 52 of 350 seats in parliament in the most recent national elections held in November 2019.

VOX's striking electoral success—and the intense media attention it attracted—has been attributed to an increase in the number of African immigrants arriving in Spain and the territorial issue derived from Catalonia's drive for independence during the autumn of 2017 with the independentist movement provoking a full-fledged national crisis (Turnbull-Dugarte, 2019). Recent studies have also pointed to the relevance of gender-related policy positions of PRR parties. VOX propagates a strong antifeminist message which some have interpreted as a response to the visibility and relevance of feminist protest events such as the historical 8M demonstrations in 2018 and 2019 in Spain (Turnbull-Dugarte, 2019; Anduiza and Rico, 2022; Cabezas, 2022). In fact, VOX denies the existence of gender-based violence and opposes gender violence protection policies. The party also vocally stands against gender quotas or abortion (Alonso and Espinosa-Fajardo, 2021; Cabezas, 2022). There is also convincing evidence that antifeminist and sexist attitudes were key to explaining vote choice for VOX both in the regional 2018 Andalusian elections and 2019 general Elections in Spain (Anduiza and Rico, 2022; Ramis-Moyano et al., 2023).

VOX' anti-gender and anti-gender equality discourse (Bernardez-Rodal et al., 2022) is common among many populist radical right parties which tend to espouse a conservative view on gender (e.g., Norocel, 2013; Akkerman, 2015; Donà, 2020). In addition, the party does share many other characteristics, including its anti-migration discourse, with the populist radical right party family and the party has been labeled as populist radical right in the scholarly literature (e.g., Gould, 2019; Alonso and Espinosa-Fajardo, 2021; Rama et al., 2021). Hence, we believe that our case study is auspicious to test our hypotheses.

To answer our research questions, we rely on an original online survey conducted among a sample that resembles the Spanish voting age population on key socio-demographic characteristics due to the use of quotas for sex, education, age, and region (Fraile, 2023). We relied on an opt-in access panel of the commercial firm Netquest which incentivized all participants with vouchers that can be used later to purchase goods at Netquest's online store. The survey was fielded between 15 and 22 December 2020, about 1 year after the national elections of November 2019. A total of 1,504 respondents were recruited from Netquest's representative web panel, with quota sampling on sex, education, age and region (51, 13.7% women, aged between 18 and 91 years). These quotas ensured that the final sample matched these characteristics in the Spanish population aged between 18 and 92.

Dependent variable

Our dependent variable is a question probing the extent to which respondents would consider voting for VOX. Answer categories range from (0) I will never vote for VOX to (1) 10-I will always vote for party VOX.2 While the extent to which VOX is a PRR party is a matter of ongoing discussion (e.g., Ferreira, 2019) various scholars have labeled it as such (e.g., Alonso and Espinosa-Fajardo, 2021; Rama et al., 2021). It does share many characteristics of the contemporary PRR party family, including its strong nationalism combined with xenophobia (nativism), its authoritarian view of society, and its attachment to the values of law and order (Ferreira, 2019). The party also strongly embraces traditional values, displayed for example by its frontal attacks against feminism (Rama et al., 2021).

Independent variables

Gender is a binary measure, distinguishing those with their reported gender (0) being a man from those who report (1) being a woman.

To measure masculinity, we use an indicator of respondents' self- assessment of their masculine features and draw on a rich, century old tradition of scholarship claiming the relevance of masculine and feminine traits for citizens' psyche (Terman and Miles, 1936). In particular, we rely on how masculine individuals feel and capture the masculine sense of themselves. The question asked to what extent respondents feel they have masculine characteristics. The scale ranged between (1) “I have few masculine characteristics” to (10) “I have many masculine characteristics.” While this measure of self-reported masculinity is relatively new, it has been previously used to measure the variation in self-ascribed masculinity (Magliozzi et al., 2016; Alexander et al., 2021a; Gidengil and Stolle, 2021), and has been validated among Swedish respondents (Markstedt et al., 2021).

Figure A1 in the appendix shows that the mean value of masculinity (and its corresponding dispersion) is substantially higher for men compared with women: (men: mean = 7.63, sd = 1.92; women: mean = 3.87; sd = 1.92). This provides evidence of the validity of the indicator in the case of Spain.

Following recent literature, we have chosen a selection of items that tap into both hostile sexism (Glick and Fiske, 1997) and modern sexism developed by Swim et al. (1995). These two families of items —hostile and modern—have been used in research in parallel (for instance, Valentino et al., 2018) and have been shown to display high inter-item correlations indicating that they do not form two distinct dimensions and can be used as a single index (Schaffner et al., 2018). Although these different understandings of sexism are theoretically two-dimensional, empirically, they are too strongly correlated to be considered distinct. We constructed an index we coined with the more general term “sexism” that reflects the broader inclusion criteria we used, integrating items from these two different families. We use the following four survey questions: “To what extent do you agree or disagree with these sentences regarding the current situation of men and women in our society? (i) Currently women are still being treated in a sexist way on television; (ii) Currently there are other social problems far more relevant than gender inequalities; (iii) When women ask for equality what they really want is to get a favor, (iv) Currently women are self-imposing their own limits.” Responses range from (0) completely agree to (4) completely disagree. Before summing responses to the four items, we re-coded some of the items so that higher values of the resulting index indicate greater levels of sexism (Cronbach's α = 0.68).

Our control variables include age (in years), education (0-up to primary; 1-secondary, 2-high school; 3-University; 4-Master/PhD), and ideology (0-extreme left to 10 extreme right). Table A1 in the appendix provides an overview of the descriptive statistics—broken down by gender—for all variables included in our analyses.

As our dependent variable is a scale ranging from 0 to 10, the analyses presented below are Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) models. The empirical strategy we deploy is 3-fold. First, we investigate the link between sex, masculinity, and the likelihood of supporting VOX. This set of analyses offers a test for the first and second hypotheses. Second, we examine to what extent sexism explains (at least) part of the empirical link between masculinity and the likelihood of supporting VOX; a test for H3 and H3a (the mediation effect). A final and third set of analyses tests the possibility that sexism moderates the association between masculinity and the propensity to support VOX as suggested in H4 and H4a. All models were tested for the magnitude of multicollinearity. Variation inflation factors (VIF) were all well-below problematic levels.3

Results

Gender, masculinity and populist radical right support

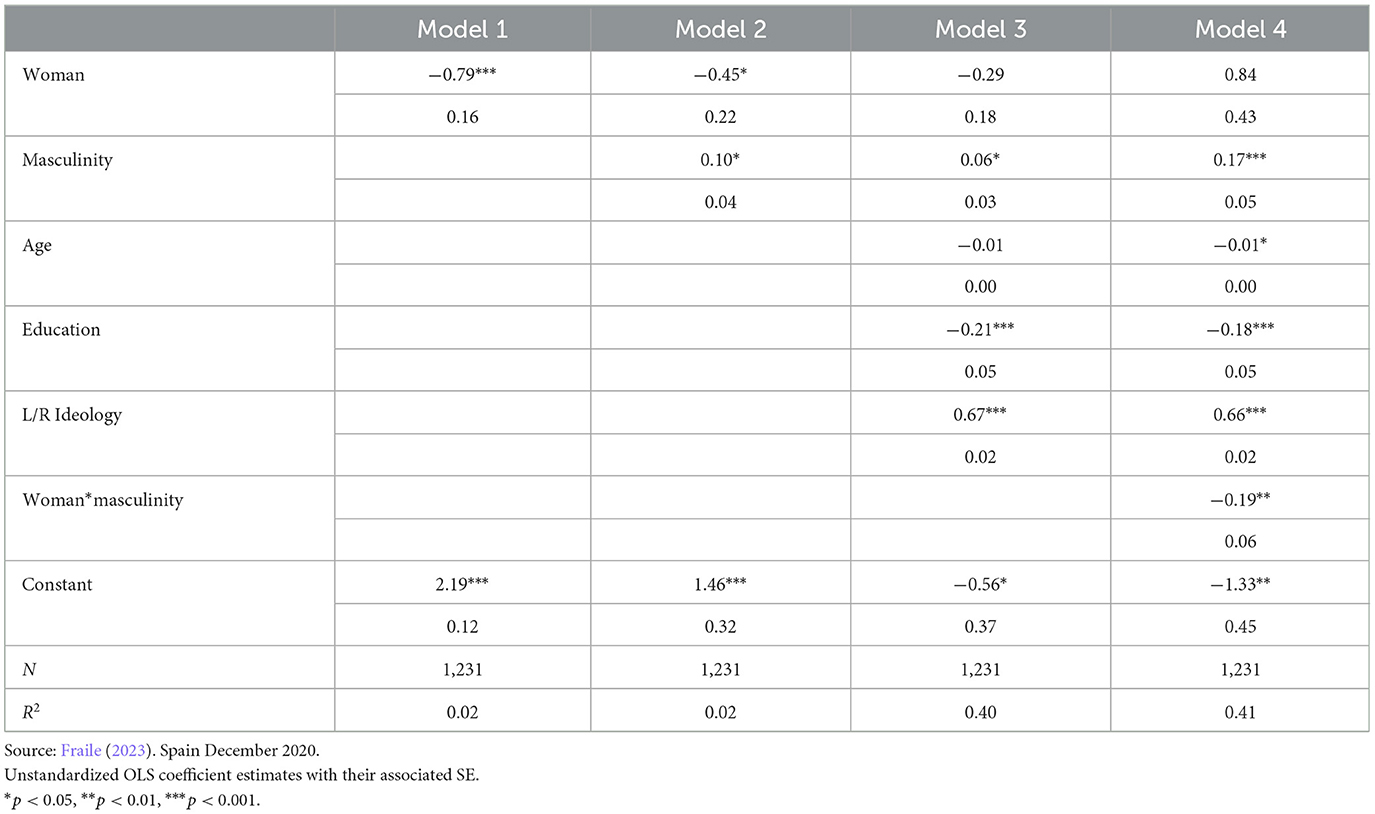

Starting with the first set of analyses examining the link between gender, masculinity and support for VOX, Table 1,4 Model 1—which only includes gender —corroborates the negative propensity of women to vote for PRR parties (in this case VOX) found in the bulk of the literature. When adding masculinity in Model 2, the gender gap remains. Model 2 also shows a link between masculinity and support for the PRR: people who feel they have many masculine characteristics are positively predisposed to vote for VOX. The effect of masculinity remains significant, even once typical antecedents of the support for PRR parties (education, age, and ideology) are controlled for. We find overall a compelling level of support for our first hypothesis. The effect of gender ceases to be significant once both masculinity and our control variables (education, age and ideology) are included in the model. Model 3 also confirms the effect of the typical antecedents of voting for PRR parties: education is negatively associated with the propensity to vote for VOX; the more conservative respondents declare to be, the greater their probability of supporting VOX.

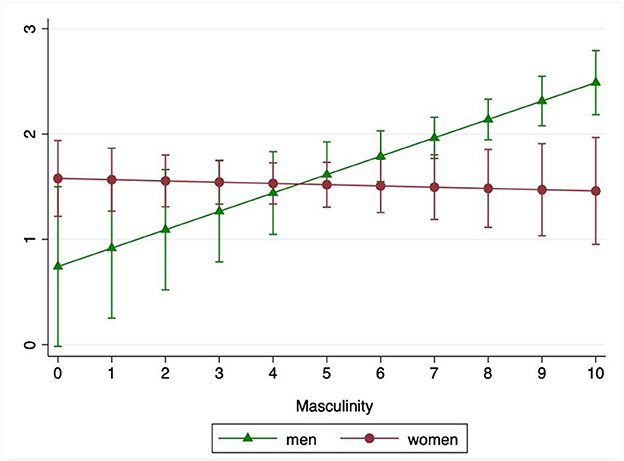

The final model presented in Table 1 (Model 4) adds an interaction term between gender and masculinity to investigate whether masculinity—as suggested in Hypothesis 2—exerts a stronger effect on the likelihood of supporting VOX among men compared with women. The results yield a statistically significant (p < 0.01) and negative estimate. The association between a masculine identity and supporting VOX is thus conditioned by gender. This suggests that masculinity matters less for women compared with men. To get a better understanding of the substantive meaning of the link between gender and masculinity and support for VOX, Figure 2 plots predicted probabilities of supporting VOX as a function of self-assessed masculinity for both men (presented by the green line with triangles) and women (presented by the red line with circles). The figure clearly illustrates that while masculinity has no impact for women's likelihood of supporting VOX, masculinity is clearly associated with the probabilities of supporting VOX among men. To provide a specific scenario, women scoring low on masculinity (value 2) have a predicted probability of 1.55 to support VOX; women scoring high on masculinity (value 10) exhibit the same predicted probability (1.51). By contrast, men who score low on masculinity (value 2) have a predicted probability of 1.09 to support VOX, compared with 2.49 among men with a high score (10) on masculinity. This suggests a substantial difference of 1.4 (that is to say: 14% points) in the probability of supporting VOX.

Figure 2. Predicted probabilities of voting for VOX by gender and masculinity. Source: Fraile (2023). Spain December 2020. Predicted values based on Model 4 in Table 1.

As discussed in the theoretical section, we expect sexism to affect the link between masculinity and support for PRR parties, both as a mediator (H3 and H3a) and moderator (H4 and H4a). Considering that the analyses above show that the impact of masculinity on voting for VOX is only relevant for men, we focus the subsequent analyses solely on men. As a measure of precaution against hasty dismissal, a replication of our analyses for women respondents was performed (see Tables A2, A3 and Figure A4 in the appendix). These analyses confirm that sexism does not play a role when studying masculinity and PRR support among women. Our focus on men also implies that—if we would find a mediating and/or moderating effect of sexism—it only holds among men, and thus can only confirm H3a and H4a which focus on men. We do not find support for H3 and H4 which suggested a mediating and moderating effect among all citizens.

Mediating effect of sexism

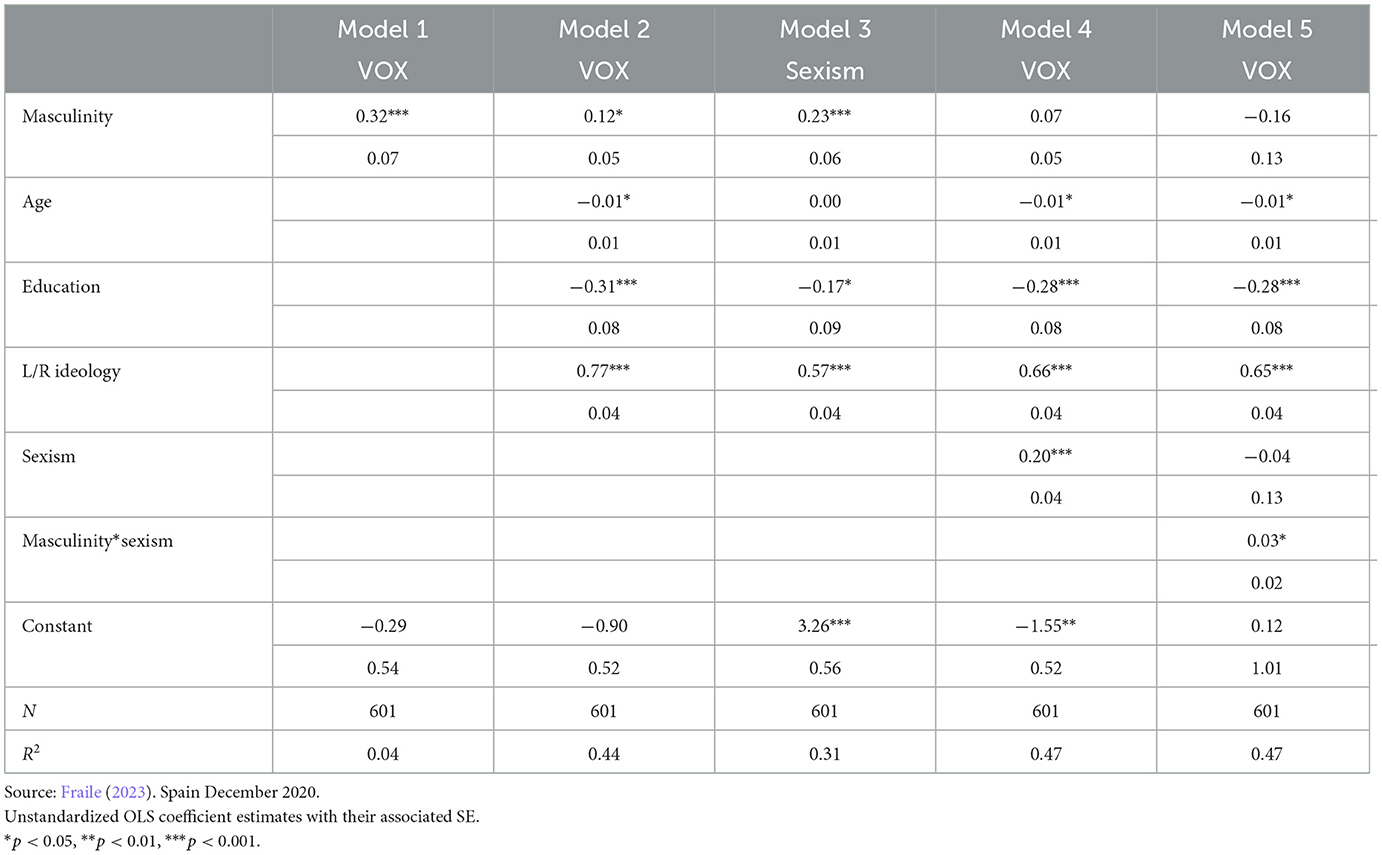

Starting with a test of H3, which suggests that sexism will at least partially explain masculine men's tendency to be attracted by PRR parties, we perform a mediation analysis. Such an analysis requires two conditions: first, masculinity should be associated with sexist attitudes; and second, sexist attitudes (the mediator) should be linked to declared probabilities of supporting VOX (controlling for masculinity). If these conditions are met, then we should observe that the size of the association between masculinity and declared probability of voting for VOX decreases when sexist attitudes are included in the estimation of declared probability of voting for VOX. This entails that a percentage of the total association between masculinity and the declared probability of voting for VOX is due to the mediation of sexist attitudes. Table 2 displays the results of this first set of estimations for men respondents.5

Table 2. Testing mediation conditions: prediction of the probabilities of voting for VOX and sexist attitudes among men.

Model 1 in Table 2 confirms that masculinity is associated with voting for VOX. This association remains statistically significant even after controlling for education, age and ideology (Model 2 in Table 2), although the size of the coefficient (and level of significance of the effect) of masculinity decreases to a great extent once the control variables are introduced. The next question then is: To what extent do sexist attitudes contribute to explaining the greater propensity of masculinity to men's propensity to vote for VOX? As a first step to answer that question, Model 3 in Table 2 estimates respondents' sexist attitudes. The results reveal a strong and positive association between masculinity and sexism. On average a one unit increase in the masculinity scale is associated with an upsurge in sexist attitudes by 0.23, which implies a 1.77% of total variation in sexism (ranging from 0 to 13). When we compare average sexist attitudes of a man with the minimum level of masculinity (0) with another man showing the highest level of masculinity (10), this entails a 2.35-point increase of sexist attitudes (or 42% of total variation in sexism). Interesting to note is also that Model 3 confirms prior findings showing that sexist attitudes decrease with education (Archer and Kam, 2020). Ideology is also positively associated with sexist attitudes: the more right-wing respondents declare themselves to be, the higher their levels of sexist attitudes. One unit increase in ideology toward the right is associated with a 0.57 increase in sexism, capturing 4.38% of the total variation in hostile sexism.

Model 4 in Table 2 tests the second mediation condition and analyses the extent to which sexist attitudes are, as expected, positively linked to supporting VOX. The results uncover a significant and positive link. More precisely, a one unit increase in sexist attitudes (an index ranging from 0 to 13) is associated with an average increase in the probability to vote for VOX (ranging from 0 to 10) of 0.20. One unit increase in sexist attitudes thus explains about two percentage points of the total variation in the probabilities to vote for VOX, and a maximum of 26 percentage points when we compare a man with the lowest level of sexist attitudes (value 0) with another man showing the highest level of sexist attitudes (value 13). Model 4 also shows that the size of the coefficient corresponding to masculinity ceases to be statistically significant when we include sexist attitudes: from 0.12 (Model 2 in Table 2 and statistically significant at p < 0.05-level) to 0.07 (Model 4 in Table 2 and not statistically significant).

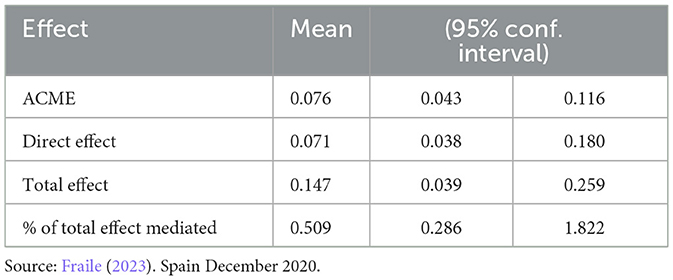

Taken together, Table 2 confirms that the conditions for the mediation hypothesis are met and that part of the association between masculinity and the likelihood of voting for VOX is explained by sexist attitudes. In order to offer a rigorous test of the mediation we use Imai et al. (2011)'s approach to partition the share of the association between masculinity and the probability of voting for VOX that is channeled through sexist attitudes. More precisely, we decompose the total effect of masculinity on the probability of supporting VOX into direct and indirect effects—-the average direct effect (ADE) and the average causal mediation effect (ACME), respectively. This approach provides a substantive measure of the magnitude of the mediation, and shows whether the mediation is statistically significant, something that the OLS estimates summarized in Table 2 cannot offer.

Table 3 summarizes the findings of the mediation estimation. The average direct effect (0.071) depicts the effect of masculinity on the probability of voting for VOX after controlling for the impact of sexist attitudes on supporting VOX. The average causal mediation effect-ACME (0.076) is statistically significant and represents the change in the probability of voting for VOX resulting from the differences in sexist attitudes across the masculinity scale. Finally, and most relevant here, from the total effect of masculinity on the probability of supporting VOX (0.147) about half of that effect (0.076) is due to sexist attitudes of men. Put differently: the percentage of the total mediated effect is 51%, denoting how much of the total effect of masculinity on the probabilities of voting for VOX is mediated by sexist attitudes.

Table 3. Mediation analysis of the effect of masculinity on voting for VOX via sexist attitudes among men.

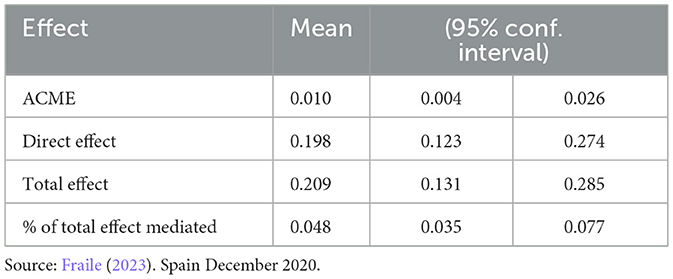

One may, however, criticize the causal order suggested in our analyses as it is also plausible that the association between men's sexism and support for PRR parties is due to their masculine identity, as hinted in Barreto and Doyle (2022). To rule out this alternative causal order, we have estimated the reversed mediation by calculating how much of the total association of sexism and support for VOX is due to masculinity (see Table 4). Findings show that from the total effect of sexism on the probability of supporting VOX (0.209) only 0.01 is due to the masculine identity of men. This implies that only about 4.8% of the total effect of sexism of men on their likelihood to vote for VOX is due to their subjective attachment to masculine identity. This evidence further confirms our fourth hypothesis, suggesting that the link between hypermasculine men and voting for PRR parties is mediated by their sexist attitudes (and not the other way around).

Table 4. Mediation analysis of the effect of sexist attitudes on voting for VOX via masculinity among men.

Moderating effect of sexism

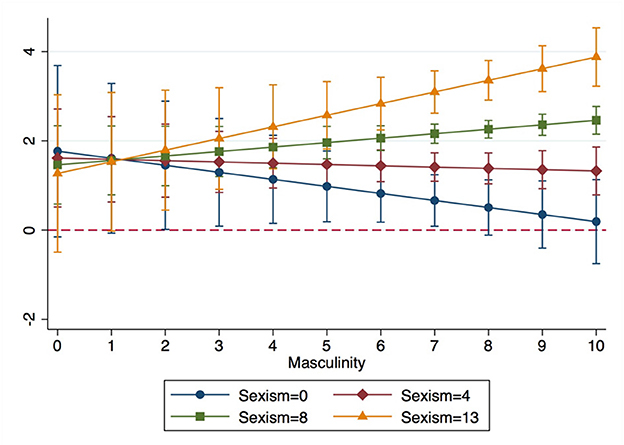

Having established the presence of a mediating effect, we now move on to testing whether a moderation (or conditional) effect also occurs. As we suggest above (H4a), a moderation effect would imply that sexist attitudes have a different effect among masculine men compared with other men. One may indeed argue that sexist attitudes are more relevant for explaining support for VOX among hypermasculine men—who we know are particularly attracted by VOX and tend to have high levels of sexist attitudes—compared with other men. If this is the case, then, the association between sexism and the probability of voting for VOX might be greater among hypermasculine men than among other men respondents. Men scoring high on masculinity (but not men scoring low on masculinity) would then report more VOX support as sexism increases.

We test for the presence of this mechanism through a final analysis replicating the estimation of Model 4 in Table 2 and adding an interaction term between masculinity and sexism (Model 5 in Table 2). Figure 3 summarizes the findings of the interaction estimation and shows that the association between masculinity and the probability of supporting VOX is stronger as the level of sexism increases (the coefficient corresponding to the interaction term between hypermasculine men and sexism is 0.03 (0.01) with corresponding p = 0.051, see Model 5 in Table 2). We find that hypermasculinity seems to matter especially among men with high levels of sexism. Comparing hypermasculine men (score 10 on masculinity) presenting the lowest levels of sexism (see the blue circle line in Figure 3) with those presenting the highest level of sexist attitudes (see the orange triangle line in Figure 3), we see differences in the probabilities of voting for VOX of around four points. By contrast, masculinity does not make a difference in the probabilities of voting for VOX among men scoring low on masculinity. Thus, when hypermasculine men exhibit high levels of sexism, they are more likely to report support for VOX.6

Figure 3. Moderation test: probabilities of voting for VOX by masculinity and sexism among men. Source: Fraile (2023). Spain December 2020. Predicted values based on Model 5 in Table 2.

Conclusion

To what extent does masculinity affect support for PRR parties? And how do sexist attitudes relate to the link between masculinity and PRR support? By answering these questions, we aimed to contribute to the current literature on gender and PRR support by overcoming two limitations of existing research. First, the focus in the existing literature on gender through a binary measure and its blindness to gendered personalities and characteristics. Second, the focus in the literature on a reaction against immigration or globalization (e.g., Norris and Inglehart, 2019) when explaining PRR voting and the cultural backlash. Only recently have studies started to look at a complementary explanation: a reaction against gender equality and demands for further improvement of gender equality (Green and Shorrocks, 2021; Anduiza and Rico, 2022; Off, 2023). To the best of our knowledge sexism has not been empirically examined as an explanation for the existing link between masculinity and PRR support. Considering the masculine and anti-gender ideology discourse of PRR parties, we argued that citizens—and in particular men—who score high on masculinity will show the greatest likelihood of supporting PRR parties. In addition, we expected sexism to relate to the link between masculinity and PRR support through two mechanisms: a mediating effect of sexism (sexism explains the link between masculinity and PRR voting) and a moderating effect of sexism (the impact of masculinity is stronger among more sexist citizens compared with citizens scoring low on sexism).

Our analyses, relying on original survey data collected among a sample of Spanish citizens resembling the Spanish voting age population (Fraile, 2023) confirmed these expectations; yet only for men (not women). We acknowledge that observational data does not allow us to establish clear directionality of effects. However, it does allow us to rule out that these attitudes are unrelated to PRR support. Our analysis does show that masculinity and sexism are important drivers of PRR support which provides a more complete picture of the attitudinal basis of support. Men scoring high on masculinity are most likely to support PRR parties. Discovering that masculinity has an important influence on men's preference for a PRR party beyond their self-identification as a man supports a comprehensive model that recognizes the complexity of gender and should encourage scholars to include measures of gendered personalities (masculinity and femininity) in surveys on political behavior. This will allow political behavior scholars to improve the current understanding of people's self-identification as woman or man, gendered personality traits, the link between them, and how they affect political behavior and attitudes.

Our analyses also show that the association between masculinity and PRR support among men can be explained by sexism, confirming a mediation effect of sexism. More specifically, we show that around half of the total association of masculinity and vote for VOX among men is mediated by their sexist attitudes. We have also shown that this causal link is stronger than a possible reverse causation (that is, masculinity mediating the association between sexist attitudes and PRR support). But there is more to it than that: we also find that sexism affects the strength of the relationship between masculinity and the likelihood of supporting the PRR; suggesting a moderation effect. Hypermasculine men express an increased likelihood of supporting VOX as their sexist attitudes increase. These findings suggest that communicative strategies of PRR leaders emphasizing signs of masculinity have an impact on men voters' behavior, though only among a specific group of men.

As VOX is commonly labeled as a populist radical right party that uses a rhetoric of threats, and threats to masculinity in particular, which is also seen among other populist radical right parties, similar patterns may be expected in other contexts. Yet, future research could usefully investigate whether similar patterns occur for other PRR parties or instead are conditioned to specific particularities of the context such as the strength and intensity of feminist mobilization, the state of the economy, or the electoral competition that these populist radical right parties might face. Given that research (Mayer, 2013, 2015) on the Front National (currently Rassemblement National) has suggested a small to no gender gap in support for the party since Marine Le Pen took over the party's leadership, it would be interesting to study PRR parties led by women to investigate whether similar effects of masculinity occur within such parties. This is a particularly interesting avenue for further research as PRR parties are increasingly including women leaders (e.g., Marine Le Pen in France, Siv Jensen and Sylvi Listhaug in Norway, Alice Weidel in Germany, and Georgia Meloni in Italy), and with some northern European PRR parties cloaking their campaign against Islam and Islamic practices against women (e.g., forced marriage, honor killings, headscarves) as a call for greater gender equality and tolerance of LGBT rights (Mayer, 2013; Akkerman, 2015; De Lange and Mügge, 2015; Mudde and Kaltwasser, 2015).

Furthermore, while masculinity matters when explaining support for PRR parties—at least among men—femininity does not have an impact (see also Coffé, 2019 on the Dutch Party for Freedom). This could be due to the fact that PRR parties demonstrate masculine traits, and thus, men voters who possess those masculine traits are more likely to vote for them. PRR parties' relationship to femininity is less clear (Mayer, 2013; Meret, 2015; Spierings and Zaslove, 2015), meaning that feminine traits do not factor into voters' decisions as to whether or not to support PRR parties. It is possible, then, that more left leaning parties will have stronger feminine traits (or be perceived as such by voters; Winter, 2010) and will therefore be more likely to attract voters—possibly women voters—who themselves possess feminine traits (McDermott, 2016). This opens an interesting avenue for further research, examining the effect of masculinity and femininity—in interaction with gender—on support for parties of different ideological orientations.

Data availability statement

The data presented in the study are publicly available. This data can be found here: GenPsyche-Study1 [DATASET]; DIGITAL.CSIC; https://doi.org/10.20350/digitalCSIC/15251.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Ethics Committee Research Institute. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Funding

This research was supported by the Spanish Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación, Agencia Estatal de Investigación (doi: 10.13039/501100011033) that financed the project GenPsyche (grant reference PID2019-107445GB-100) led by MF.

Acknowledgments

A previous version of the paper was presented at the 2022 ECPG Conference. We thank all participants — and in particular our discussant Gefjon Off — for their helpful feedback.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2023.1038659/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^While most agree on the gender gap in PRR support, some interesting cross-national differences have been found (Immerzeel et al., 2015; Weeks et al., 2023).

2. ^The exact wording is as follows: “Consider the following political parties typically competing in national elections. Could you express the odds that you would vote for each of them?” 0-I will never vote for party X, and 10-I will always vote for party X.

3. ^The highest VIF values are 1.84 for gender in the analysis presented in Table 1, and 1.44 for both sexism and ideology in the analysis presented in Table 2.

4. ^Total N varies across models presented in Table 1 because we deleted all missing values (refuse and Don't Know) for each of the variables included in each model.

5. ^Table 2 keeps constant the number of observations included in each model. Therefore, only participants who provided valid responses to all variables included in Model 4 are considered for the estimation. This strategy allows comparison of the size of the coefficient corresponding to masculinity across equations.

6. ^To assess the robustness of the interaction term, we have replicated the estimations summarized in Figure 3 using the command marhis in Stata, which includes a histogram summarising the distribution of the variable on the x-axis in the back. Figure A3 in the appendix plots Average Marginal Effects (AMEs) of masculinity on the probabilities of voting for VOX across values of hostile sexism. It confirms that the average marginal effect of masculinity on the probabilities of voting for VOX is statistically different from zero only for high values of hostile sexism (from 10 onwards). Although we might lack precision in our estimations, Figure A3 suggests that there is enough variation across the values of the variable hostile sexism to make the calculations provided in Figure 3.

References

Akkerman, T. (2015). Gender and the radical right in Western Europe: a comparative analysis of policy agendas. Patt. Prejudice 49, 37–60. doi: 10.1080/0031322X.2015.1023655

Alexander, A. C., Bolzendahl, C., and Öhberg, P. (2021b). Gender, socio-political cleavages and the co-constitution of gender identities: a multidimensional analysis of self-assessed masculine and feminine characteristics. Eur. J. Polit. Gender 4, 151–171. doi: 10.1332/251510820X16062293641763

Alexander, A. C., Bolzendahl, C., and Wängnerud, L. (2021a). Beyond the binary: new approaches to measuring gender in political science research. Eur. J. Polit. Gender 4, 7–9. doi: 10.1332/251510820X16067519822351

Alonso, A., and Espinosa-Fajardo, J. (2021). Blitzkrieg against democracy: gender equality and the rise of the populist radical right in Spain. Soc. Polit. 28, 656–681. doi: 10.1093/sp/jxab026

Anduiza, E., and Rico, G. (2022). Sexism and the far right vote: the individual dynamics of gender backlash. Am. J. Polit. Sci. (in online). doi: 10.1111/ajps.12759

Archer, A. M. N., and Kam, C. D. (2020). Modern sexism in modern times public opinion in the #Metoo Era. Public Opin. Q. 84, 813–837. doi: 10.1093/poq/nfaa058

Barreto, M., and Doyle, D. M. (2022). Benevolent and hostile sexism in a shifting global context. Nat. Rev. Psychol. 2, 98–111. doi: 10.1038/s44159-022-00136-x

Bem, S. L. (1974). The measurement of psychological androgyny. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 42, 155–162. doi: 10.1037/h0036215

Bem, S. L. (1981). Bem Sex Role Inventory Professional Manual. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

Bernardez-Rodal, A., Rey, P. R., and Franco, Y. G. (2022). Radical right parties and anti-feminist speech on Instagram: vox and the 2019 Spanish general election. Party Polit. 28, 272–283. doi: 10.1177/1354068820968839

Bittner, A., and Goodyear-Grant, E. (2017). Sex isn't gender: reforming concepts and measurements in the study of public opinion. Polit. Behav. 39, 1019–1041. doi: 10.1007/s11109-017-9391-y

Burkley, M., Wong, Y. J., and Bell, A. C. (2016). The masculinity contingency scale (MCS): scale development and psychometric properties. Psychol. Men Masc. 17, 113–125. doi: 10.1037/a0039211

Cabezas, M. (2022). Silencing feminism? Gender and the rise of the nationalist far right in Spain. Signs 47, 319–345. doi: 10.1086/716858

Campillo, I. (2019). If we stop, the world stops: the 2018 feminist strike in Spain. Soc. Mov. Stud. 18, 252–258 doi: 10.1080/14742837.2018.1556092

Carian, E., and Sobotka, T. C. (2018). Playing the trump card: masculinity threat and the US 2016 presidential election. Socius 4, 1–6. doi: 10.1177/2378023117740699

Cassese, E. C., and Holman, M. R. (2019). Playing the woman card: ambivalent sexism in the 2016 U.S. Presidential race. Polit. Psychol. 40, 55–74 doi: 10.1111/pops.12492

Coffé, H. (2018). “Gender and the radical right,” in The Oxford Handbook of the Radical Right, ed. J. Rydgren (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 200–211.

Coffé, H. (2019). Gender, gendered personality traits and radical right populist voting. Politics 39, 170–185. doi: 10.1177/0263395717745476

Daddow, O., and Hertner, I. (2021). interpreting toxic masculinity in political parties: a framework for analysis. Party Polit. 27, 743–754. doi: 10.1177/1354068819887591

De Lange, S. L., and Mügge, L. M. (2015). Gender and right-wing populism in the low countries: ideological variations across parties and time. Patt. Prejudice 49, 61–80. doi: 10.1080/0031322X.2015.1014199

DiMuccio, S. H., and Knowles, E. D. (2021). Precarious manhood predicts support for aggressive policies and politicians. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 47, 1169–1187. doi: 10.1177/0146167220963577

Donà, A. (2020). The populist Italian Lega from ethno-regionalism to radical right-wing nationalism: backsliding gender-equality policies with a little help from the anti-gender movement. Eur. J. Polit. Gender 3, 161–163. doi: 10.1332/251510819X15657567135115

Ferreira, C. (2019). Vox as representative of the radical right in Spain: a study of its ideology. Rev. Española Cienc. Polít. 51, 73–98. doi: 10.21308/recp.51.03

Fontana, M.-C., Sidler, A., and Hardmeier, S. (2006). The ‘new right' vote: an analysis of the gender gap in the vote choice for the SVP. Swiss Polit. Sci. Rev. 12:243–271. doi: 10.1002/j.1662-6370.2006.tb00067.x

Foushee, H. C., Helmreich, R. L., and Spence, J. T. (1979). Implicit theories of masculinity and femininity: dualistic or bipolar? Psychol. Women Q. 3, 259–269. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.1979.tb00544.x

Gidengil, E., Hennigar, M., Blais, A., and Nevitte, N. (2005). Explaining the gender gap in support for the new right. The case of Canada. Comp. Polit. Stud. 38, 1171–1195. doi: 10.1177/0010414005279320

Gidengil, E., and Stolle, D. (2021). Beyond the gender gap: the role of gender identity. J. Polit. 83, 1818–1822 doi: 10.1086/711406

Givens, T. E. (2004). The radical right gender gap. Comp. Polit. Stud. 37, 30–54. doi: 10.1177/0010414003260124

Glick, P., and Fiske, S. T. (1997). Hostile and benevolent sexism: measuring ambivalent sexist attitudes toward women. Psychol. Women Q. 21, 121. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.1997.tb00104.x

Glick, P., Wilkerson, M., and Cuffe, M. (2015). Masculine identity, ambivalent sexism, and attitudes toward gender subtypes: favoring masculine men and feminine women. Soc. Psychol. 46, 210–217. doi: 10.1027/1864-9335/a000228

Gökariksel, B., Neubert, C., and Smith, S. (2019). Demographic fever dreams: fragile masculinity and population politics in the rise of the global right. Signs 44, 561–587. doi: 10.1086/701154

Gould, R. (2019). Vox España and Alternative für Deutschland: Propagating the Crisis of National Identity. Genealogy 3, 64. doi: 10.3390/genealogy3040064

Graff, A. (2014). Report from the gender trenches: war against ‘genderism' in Poland. Eur. J. Womens Stud. 21, 431–435. doi: 10.1177/1350506814546091

Green, J., and Shorrocks, R. (2021). The gender backlash in the vote for Brexit. Polit. Behav. 45, 347–71. doi: 10.1007/s11109-021-09704-y

Harteveld, E., and Ivarsflaten, E. (2018). Why women avoid the radical right: internalized norms and policy reputations. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 48, 369–384. doi: 10.1017/S0007123415000745

Imai, K., Keele, L., Tingle, D., and Yamamoto, T. (2011). Unpacking the black box of causality: learning about causal mechanisms from experimental and observational studies. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 105, 765–789. doi: 10.1017/S0003055411000414

Immerzeel, T., Coffé, H., and van der Lippe, T. (2015). Explaining the gender gap in radical right voting: a cross-national investigation in 12 Western-European countries. Comp. Eur. Polit. 13, 263–286. doi: 10.1057/cep.2013.20

Jimenez, M., Fraile, M., and Lobera, J. (2022). Testing public reactions to mass protest hybrid media events: a rolling cross-sectional study of International Women's Day in Spain. Public Opin. Q. 83, 597–620 doi: 10.1093/poq/nfac033

Maass, A., Cadinu, M., Guarnieri, G., and Grasselli, A. (2003). Sexual harassment under social identity threat: the computer harassment paradigm. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 85, 853–870. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.85.5.853

Magliozzi, D., Saperstein, A., and Westbrook, L. (2016). Scaling up: representing gender diversity in survey research. Socius 2, 1–11. doi: 10.1177/2378023116664352

Markstedt, E., Wängnerud, L., Solevid, M., and Djerf-Pierre, M. (2021). The subjective meaning of gender: how survey designs affect perceptions of femininity and masculinity. Eur. J. Polit. Gender 4, 51–70. doi: 10.1332/251510820X15978605298709

Mayer, N. (2013). From Jean-Marie to Marine Le Pen: Electoral change on the far right. Parliam. Aff. 66, 160–178. doi: 10.1093/pa/gss071

Mayer, N. (2015). “The closing gap of the radical right gender gap in France?” Fr. Politics. 13, 391–414.

McDermott, M. L. (2016). Masculinity, Femininity, and American Political Behavior. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Meret, S. (2015). Charismatic female leadership and gender: Pia Kjærsgaard and the Danish People's Party. Patt. Prejudice 49, 81–102. doi: 10.1080/0031322X.2015.1023657

Mosher, D. L., and Tomkins, S. S. (1988). Scripting the macho man: hypermasculine socialization and enculturation. J. Sex Res. 25, 60–84. doi: 10.1080/00224498809551445

Mudde, C., and Kaltwasser, C. R. (2015). Vox populi or vox masculini? Populism and gender in Northern Europe and South America. Patt. Prejudice 49, 16–36. doi: 10.1080/0031322X.2015.1014197

Norocel, O. C. (2013). ‘Give Us Back Sweden!' A Feminist Reading of the (Re)Interpretations of the Folkhem Conceptual Metaphor in Swedish Radical Right Populist Discourse. NORA Nord. J. Femin. Gender Res. 21, 4–20. doi: 10.1080/08038740.2012.741622

Norris, P., and Inglehart, R. (2019). Cultural Backlash. Trump, Brexit and Authoritarian Populism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Off, G. (2023). Gender equality salience, backlash and radical right voting in the gender-equal context of Sweden. West Eur. Polit. 46, 451–476. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2022.2084986

Pleck, J. H. (1975). Masculinity-femininity: current and alternative paradigms. Sex Roles 12, 161–178. doi: 10.1007/BF00288009

Ralph-Morrow, E. (2022). The right men: how masculinity explains the radical right gender gap. Polit. Stud. 70, 26–44. doi: 10.1177/0032321720936049

Rama, J., Zanotti, L., Turnbull-Dugarte, S. J., and Santana, A. (2021). VOX: The Rise of the Spanish Populist Radical Right. Oxon and New York, NY: Routledge.

Ramis-Moyano, R., Pasadas-del-Amo, S., and Font, J. (2023). Not only a territorial matter: The electoral surge of VOX and the anti-libertarian reaction. PLoS ONE. 18, e0283852. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0283852

Ratliff, K. A., Redford, L., Conway, J., and Smith, C. T. (2019). Engendering support: Hostile sexism predicts voting for Donald Trump over Hillary Clinton in the 2016 US presidential election. Group Process. Intergr. Relat. 22, 578–593. doi: 10.1177/1368430217741203

Rippeyoung, P. L. F. (2007). When women are right: the influence of gender, work and values on European far-right party support. Int. Femin. J. Polit. 9, 379–397. doi: 10.1080/14616740701438259

Schaffner, B. F., MacWilliams, M., and Nteta, T. (2018). Understanding white polarization in the 2016 vote for president: the sobering role of racism and sexism. Polit. Sci. Q. 133, 9–34 doi: 10.1002/polq.12737

Smirnova, M. (2018). Small hands, nasty women, and bad hombres: hegemonic masculinity and humor in the 2016 presidential election. Socius 4:1–16. doi: 10.1177/2378023117749380

Spierings, N., and Zaslove, A. (2015). Gendering the vote for populist radical-right parties. Patt. Prejudice 49, 135–162. doi: 10.1080/0031322X.2015.1024404

Swim, J. K., Aikin, K. J., Hall, W. S., and Hunter, B. A. (1995). Sexism and racism: Old-fashioned and modern prejudices. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 68, 199–214.

Terman, L. M., and Miles, C. C. (1936). Sex and Personality: Studies in Masculinity and Femininity. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Turnbull-Dugarte, S. J. (2019). Explaining the end of Spanish exceptionalism and electoral support for Vox. Res. Polit. 6, 1–8. doi: 10.1177/2053168019851680

Valentino, N., Wayne, C., and Oceno, M. (2018). Mobilizing sexism: the interaction of emotion and gender attitudes in the 2016 U.S. presidential election. Public Opin. Q. 82, 213–235. doi: 10.1093/poq/nfy003

Vescio, T., and Schermerhorn, N. E. C. (2021). Hegemonic masculinity predicts 2016 and 2020 voting and candidate evaluations. PNAS Pscyhological and Cognitive Sciences 118, e2020589118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2020589118

Weeks, A. C., Meguid, B. M., Kittilson, M. C., and Coffé, H. (2023). When do Männerparteien elect women? Radical right populist parties and strategic descriptive representation. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 117, 421–438. doi: 10.1017/S0003055422000107

Willer, R., Rogalin, C. L., Conlon, B., and Wojnowicz, M. T. (2013). Overdoing gender: a test of the masculine overcompensation thesis. Am. J. Sociol. 118, 980–1022. doi: 10.1086/668417

Williams, J. E., and Best, D. L. (1982). Measuring Sex Stereotypes: A Thirty-Nation Study. Beverly Hills, CA: SAGE Publishing.

Winter, N. J. G. (2010). Masculine republicans and feminine democrats: Gender and Americans' explicit and implicit images of the political parties. Polit. Behav. 32, 587–618. doi: 10.1007/s11109-010-9131-z

Keywords: populist radical right support, gender, masculinity, sexism, VOX (political party)

Citation: Coffe H, Fraile M, Alexander A, Fortin-Rittberger J and Banducci S (2023) Masculinity, sexism and populist radical right support. Front. Polit. Sci. 5:1038659. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2023.1038659

Received: 07 September 2022; Accepted: 17 April 2023;

Published: 16 May 2023.

Edited by:

Régis Dandoy, Universidad San Francisco de Quito, EcuadorReviewed by:

Davide Morisi, Collegio Carlo Alberto, ItalyPiotr Zagórski, University of Social Sciences and Humanities, Poland

Copyright © 2023 Coffe, Fraile, Alexander, Fortin-Rittberger and Banducci. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Hilde Coffe, aGM5NjVAYmF0aC5hYy51aw==

Hilde Coffe

Hilde Coffe Marta Fraile

Marta Fraile Amy Alexander

Amy Alexander Jessica Fortin-Rittberger

Jessica Fortin-Rittberger Susan Banducci

Susan Banducci